1 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Gansu Provincial Hospital & The Third Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

2 The Institute of Clinical Research and Translational Medicine, Gansu Provincial Hospital & The Third Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

3 Clinical Trials Center, The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, 550000 Guiyang, Guizhou, China

4 Department of Pharmacy, Clinical Research Center of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, 550000 Guiyang, Guizhou, China

Abstract

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a condition marked by diminished ovarian function and reduced fertility, caused by the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide (CTX) used to treat gynecologic cancers. The abnormal inflammation of ovarian tissue induced by CTX represents a key factor that impairs follicular cells and disrupts fertility. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the underlying mechanisms of CTX-induced abnormal ovarian inflammation and identify potential therapeutic agents.

RNA sequencing data derived from CTX-induced mouse ovarian tissues were first intersected with inflammation-related genes retrieved from the Gene Ontology (GO) database. This was followed by functional enrichments analysis and protein-protein interaction (PPI) analyses to identify target genes. Subsequently, the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP) was screened to obtain corresponding candidate therapeutic agents. Finally, a CTX-induced mouse model was established to verify the therapeutic efficacy of the candidate drug and elucidates its underlying mechanisms.

A total of 25 candidate genes were identified, with interleukin 1β (IL1β) confirmed as the core gene. Subsequent screening resulted in the identification of Irisolidone as a potential therapeutic agent. The present study demonstrated that Irisolidone ameliorates CTX-induced follicular cell developmental impairment and improves fertility in mice with POI. Mechanistically, it was found that Irisolidone suppressed abnormal ovarian inflammation by inhibiting the CTX-disrupted nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB)/NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3)/Caspase1 signaling pathway.

The present study demonstrates that Irisolidone can effectively alleviate CTX-induced POI by inhibiting abnormal inflammation. These findings suggest that Irisolidone holds promise as a novel therapeutic candidate for POI, thereby providing a potential new treatment strategy for clinical management of this condition.

Keywords

- premature ovarian insufficiency

- cyclophosphamide

- Irisolidone

- inflammation

- Chinese traditional medicine

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a clinical syndrome defined by impaired ovarian function and reduced fertility, with an incidence of approximately 1–5% among women [1, 2]. Clinical manifestations of POI include menstrual irregularities and infertility, and the condition is frequently associated with anxiety, memory impairment, and osteoporosis [3, 4]. The etiology of POI is complex, encompassing factors such as inflammation, genetic variations, environmental exposures, and underlying medical conditions [5]. Therefore, exploring the potential mechanisms and therapeutic targets for POI is urgent.

Worldwide, roughly 9 million women receive a cancer diagnosis annually. Of these cases, breast cancer is the most prevalent, with colorectal cancer and cervical cancer ranking second and third, respectively [6]. Chemotherapy is a pivotal approach for the treatment and control of cancer; however, due to their poor targeting, chemotherapeutic agents can damage normal tissues while eliminating cancer cells [7]. Clinically, cyclophosphamide (CTX)-widely used in the treatment of gynecological cancers-can induce damage to ovarian cells, leading to impaired ovarian function and infertility [8]. Additionally, embryo cryopreservation represents a viable option for young patients with POI, but this technique is associated with inherent risks and high costs [9]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore additional potential therapeutic agents.

The onset and progression of POI are associated with multiple factors, among which an inflammatory microenvironment within the ovaries serves as a key mediator of ovarian dysfunction. Dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines can affect follicular development and ovulation, ultimately leading to the development of POI and subsequently infertility [10, 11]. CTX treatment is known to induce inflammatory abnormalities in multiple organs, including the heart, kidneys, and lungs [12, 13, 14]. Importantly, the persistent inflammation triggered by CTX can drive cellular senescence and functional impairment of normal ovarian cells [15]. Therefore, the identification of novel anti-inflammatory agents may provide potential therapeutic options for the clinical management of POI.

Given the potential relationship between POI and abnormal inflammation, the present study aims to identify shared therapeutic targets by integrating the screening of POI-related risk factors and inflammatory risk factors. Subsequently, potential compounds with anti-inflammatory properties will be screened from a natural product library, followed by validation in a CTX-induced POI mouse model. In summary, this study seeks to identify novel candidate therapeutic agents, thereby providing new strategies for the clinical treatment of POI.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23; revised 1978). The protocol for all animal experiments was approved by the Animal Experimental Ethical Inspection Form at Guizhou Medical University (No. 12403436). Seven-week-old female C57BL/6 mice of were obtained from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) and allowed to acclimate to the new environment for one week, with free access to standard chow and water throughout the acclimation period. Female mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility, maintained under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, humidity 10–70%, temperature of 20–25 ℃, and free access to standard chow and water.

The animals were randomly divided into four groups (n = 10 per group): (1) Sham + Vehicle group, (2) Sham + Irisolidone group, (3) POI + Vehicle group, and (4) POI + Irisolidone group. Female mice in the POI group (Groups 3 and 4) received a single intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide (CTX, 100 mg/kg, Selleck, Cat. NO. S1217, CAS No: 50-18-0) to induce a POI model. Female in the control group (Groups 1 and 2) received an equivalent volume of vehicle solution via intraperitoneal injection. Subsequently, female mice in the Irisolidone-treated groups (Groups 2 and 4) received daily intraperitoneal injections of Irisolidone (50 mg/kg, BioBioPha, BBP No: BBP06887, CAS No: 2345-17-7) for three consecutive weeks.

At the end of the treatment period, female mice were anesthetized with 3% pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection, followed by cardiac blood collection. After transcardial perfusion with physiological saline, ovaries were harvested. Ovarian tissues and serum samples (separated from collected blood) were stored appropriately for subsequent experimental analyses.

The ovarian RNA sequencing data for the CTX-induced POI mouse model were

obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/) database under accession number GSE128240

[16]. The inflammation-related gene datasets were retrieved from the

“Inflammatory Response” pathway within the Gene Ontology (GO) database. To

identify candidate genes, GO enrichment analysis was performed using Metascape

(https://metascape.org/), a comprehensive tool for functional annotation and gene

lists analysis. For pathway analysis, the Database for Annotation, Visualization,

and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/) is

utilized to conduct Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG,

https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) functional enrichment analysis. The candidate genes

were subjected to Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) analysis using Cytoscape

software (National Resource for Network Biology, San Diego, CA, USA) to identify

core proteins. Additionally, the conservation of interleukin 1

Natural compounds with anti-inflammatory properties were initially screened

using the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP,

https://www.tcmsp-e.com/load_intro.php?id=43) database [17, 18]. Subsequently,

the compound library was further refined based on drug-like properties, including

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), molecular weight,

oral bioavailability, drug half-life, and other pharmacokinetic parameters. This

refinement process identified potential drug candidates with favorable

pharmaceutical properties. Finally, Molecular Operating Environment (MOE,

Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Canada) software was utilized to perform

molecular docking simulations of these druggable compounds, aiming to evaluate

their binding affinity to the target protein IL1

Following collecting, ovarian tissues were immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature overnight. The fixed tissues were then processed for paraffin embedding, followed by sectioning into 5 µm-thick slices. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was performed on these sections to assess histological structure. Subsequently, based on established ovarian cell classification criteria, follicles at different developmental stages-including primordial, primary, secondary, antral, and atretic follicles-were identified and quantified [19].

The Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining procedure is as follows: Ovarian tissue

sections were dewaxed and subjected to antigen retrieval. After cooling, the

sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10–15 minutes to block

endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by blocking with 5% BSA for 30 minutes.

phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa B (p-NF

Blood was obtained from anesthetized mice, and the whole blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 minutes to isolated serum. Serum samples were then used to determine the concentrations of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH; JONLNBIO, Cat. No. JL16387, Shanghai, China), estradiol (E2; Solarbio Life Sciences, Cat. No. SEKM-0286, Beijing, China), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH; JONLNBIO, Cat. No. JL10239, Shanghai, China) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, in strict accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions.

Total proteins were extracted from ovarian tissue samples using RIPA lysis

buffer (Beyotime, Cat. No. P0013B, Shanghai, China), and protein concentrations

were determined via a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Beyotime, Cat. No.

P0009, Shanghai, China). Equal amounts of protein were separated by sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then

transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were

blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween®

20 (TBST) for 2 hours at room temperature. This was followed by overnight

incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies against the following

targets: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:10,000, ABclonal,

Cat. No. AC002, Wuhan, China), phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa B

(p-NF

Total RNA was extracted from ovarian tissue samples using TRIzol® reagent (Beyotime, Cat No. R0016), and RNA concentration and purity were evaluated using a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using a HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Cat No. R212-01, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative mRNA expression levels of target genes were detected via quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Cat. No. Q511-02, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China).

The primer sequences are as following:

IL1

Forward primer: TGCCACCTTTTGACAGTGATG

Reverse primer: AAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC

IL18: Interleukin 18 (NM_008360.2)

Forward primer: TACAAGCATCCAGGCACAGC

Reverse primer: CTGATGCTGGAGGTTGCAGA

NLRP3: NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NM_145827.4)

Forward primer: GTCACCATGGGTTCTGGTCA

Reverse primer: GGGCTTAGGTCCACACAGAA

Caspase1: caspase 1 (NM_009807.2)

Forward primer: AACGCCATGGCTGACAAGA

Reverse primer: TGATCACATAGGTCCCGTGC

Actin: Actin beta (NM_007393.5)

Forward primer: TATAAAACCCGGCGGCGCA

Reverse primer: TCATCCATGGCGAACTGGTG

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San

Diego, CA, USA) and presented as mean

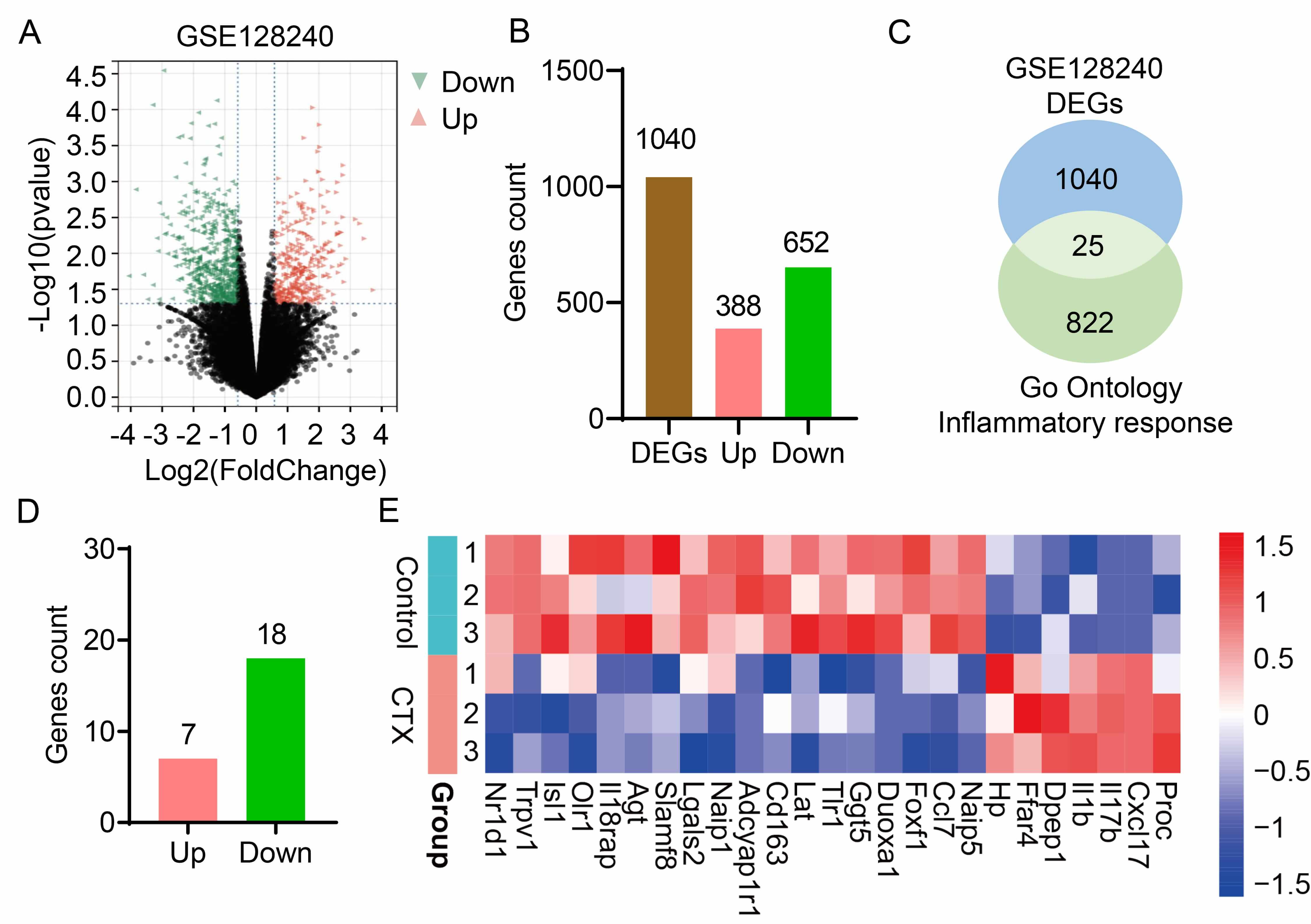

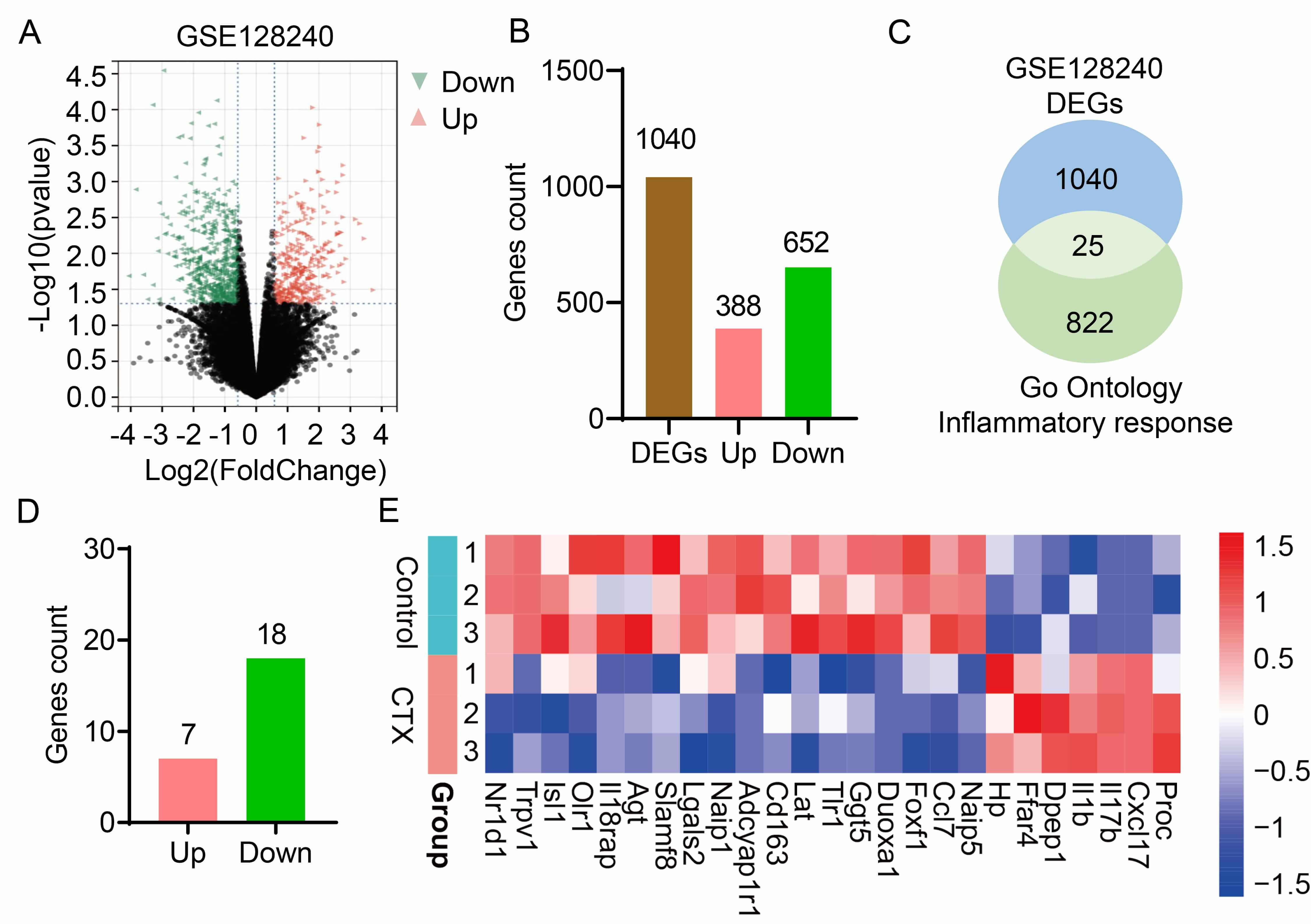

To characterize changes in ovarian tissue gene expression following CTX treatment, the RNA sequencing dataset (GSE128240) from CTX-induced POI mouse models was analyzed. Differential gene expression analysis identified 1040 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in CTX-induced POI, comprising 388 upregulated genes and 652 downregulated genes (Fig. 1A,B). CTX treatment disrupts the balance of ovarian inflammation, which contributes to the onset and progression of POI. To further identify aberrantly expressed inflammatory genes in ovarian tissue, inflammation-related genes were retrieved from the GO database. Subsequent intersection analysis between these inflammation response genes and the DEGs from GSE128240 yielded 25 key inflammatory genes (Fig. 1C). Of these 25 genes, 7 were upregulated and 18 were downregulated (Fig. 1D), and a heatmap was generated to visualize the expression profiles of these key DEGs (Fig. 1E). In conclusion, integrated analysis of GEO dataset (GSE128240) and GO-derived inflammatory genes enabled the identification of 25 inflammation-associated candidate genes in POI.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Inflammatory candidate genes in premature ovarian insufficiency induced by cyclophosphamide. (A) Volcano plot of RNA sequencing data from the GSE128240 dataset, showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in CTX-induced POI mouse models. (B) The number of upregulated (Pink) and downregulated (Green) DEGs. (C) A Venn diagram illustrates overlap between DEGs from GSE128240 dataset and genes form the “Inflammatory Response” term in the Gene Ontology (GO) database. (D) Detailed gene count of the 25 candidate genes, upregulated (Pink) and downregulated (Green). (E) A heatmap illustrates the expression patterns of the 25 candidate genes across the various samples in the study. CTX, Cyclophosphamide, it is a synthetic alkylating agent chemotherapeutic drug and also a commonly used immunosuppressant in clinical practice.

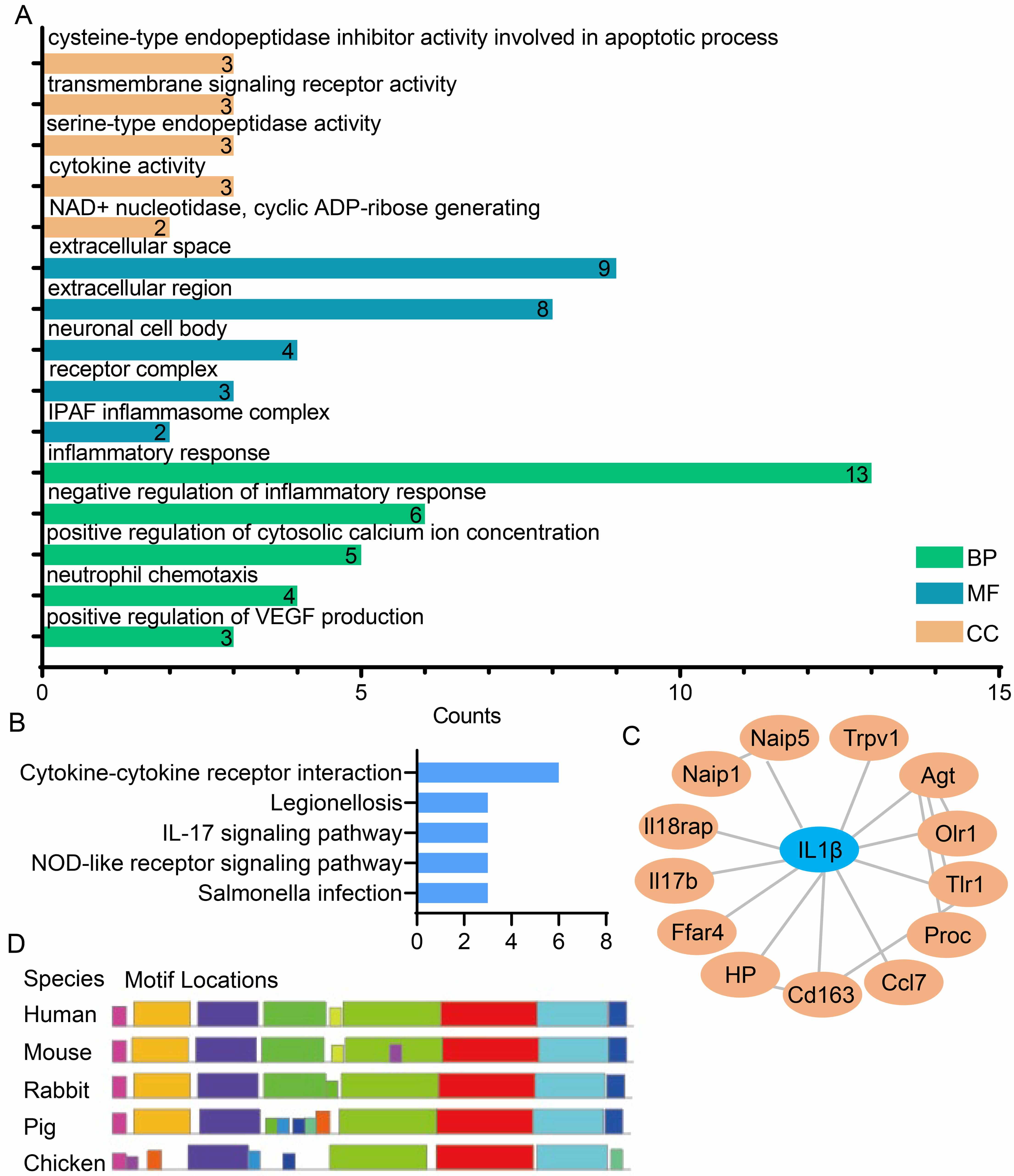

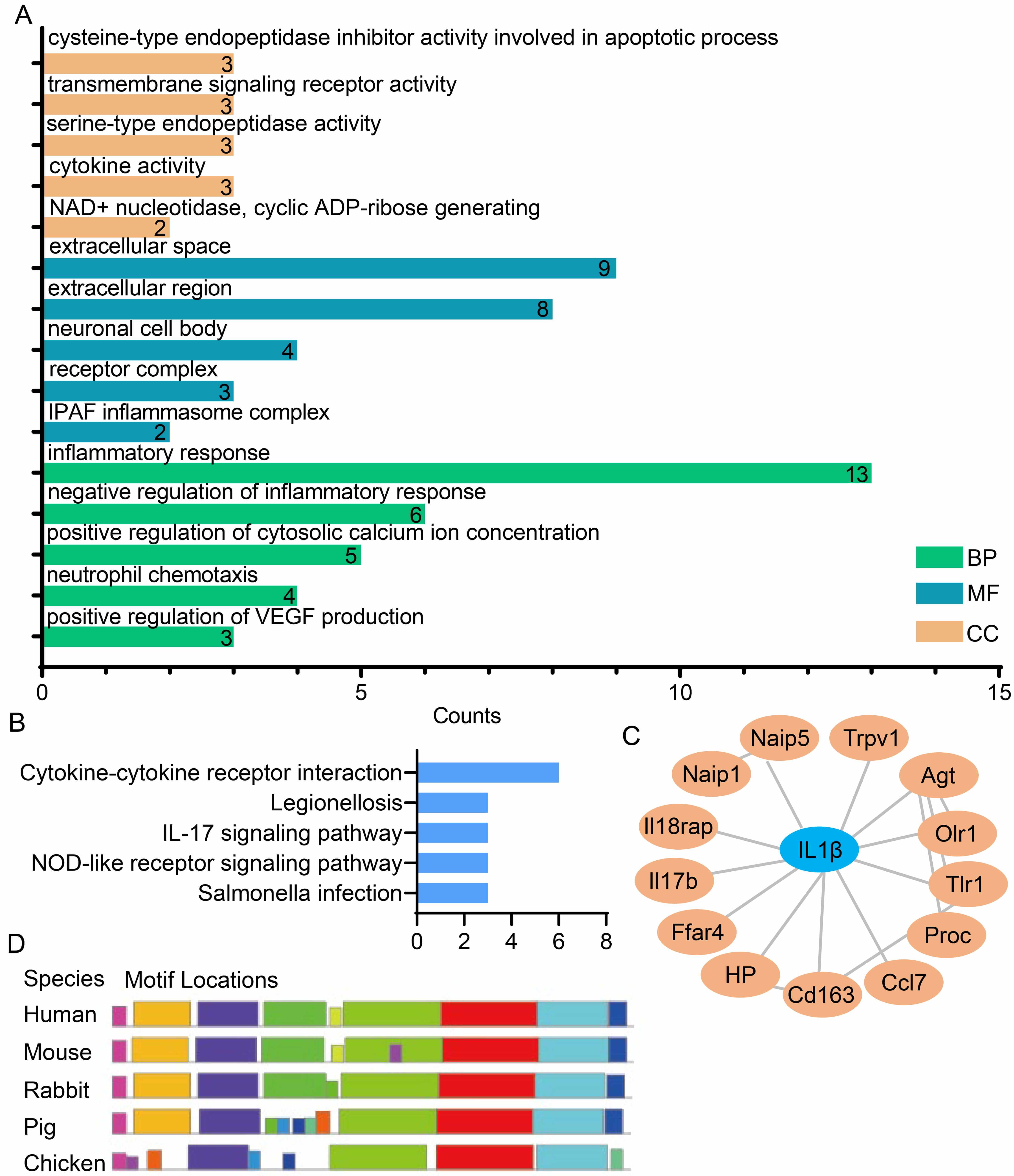

To elucidate the regulatory pathways associated with the 25 candidate genes, GO

and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed (Fig. 2A,B). The results showed that

these candidate genes are significantly enriched in inflammation-related

biological processes and signaling pathways, including “Inflammatory Response”,

“Neutrophil Chemotaxis”, “Cytokine Activity”, “Cytokine-Cytokine Receptor

Interaction”, and the “IL-17 Signaling Pathway” (Fig. 2A,B). To further

identify core inflammatory genes with this set, PPI network analysis was

conducted for the 25 candidate genes using Cytoscape software (Fig. 2C). This

analysis identified IL1

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Identification and analysis of the core inflammatory

IL1

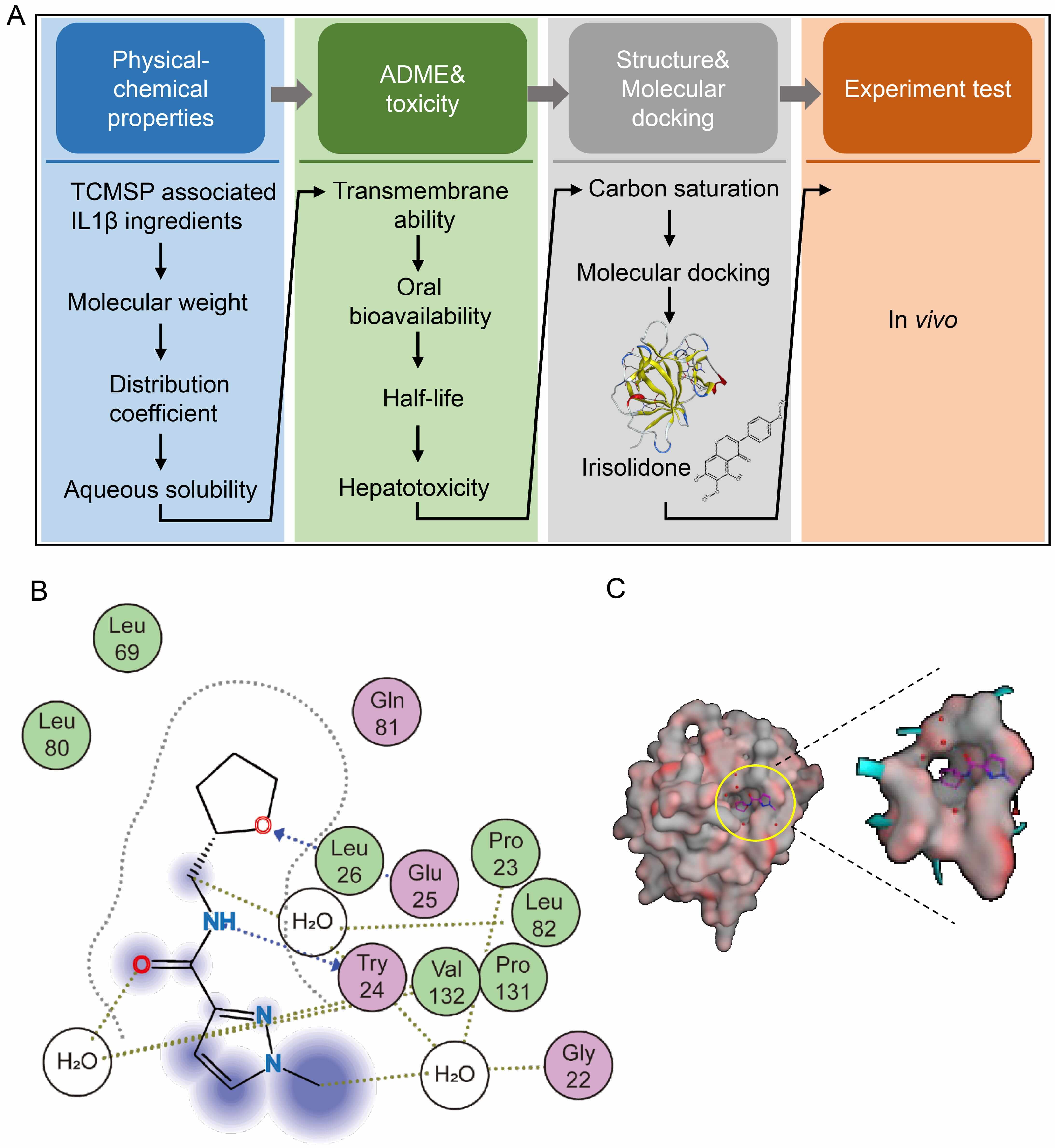

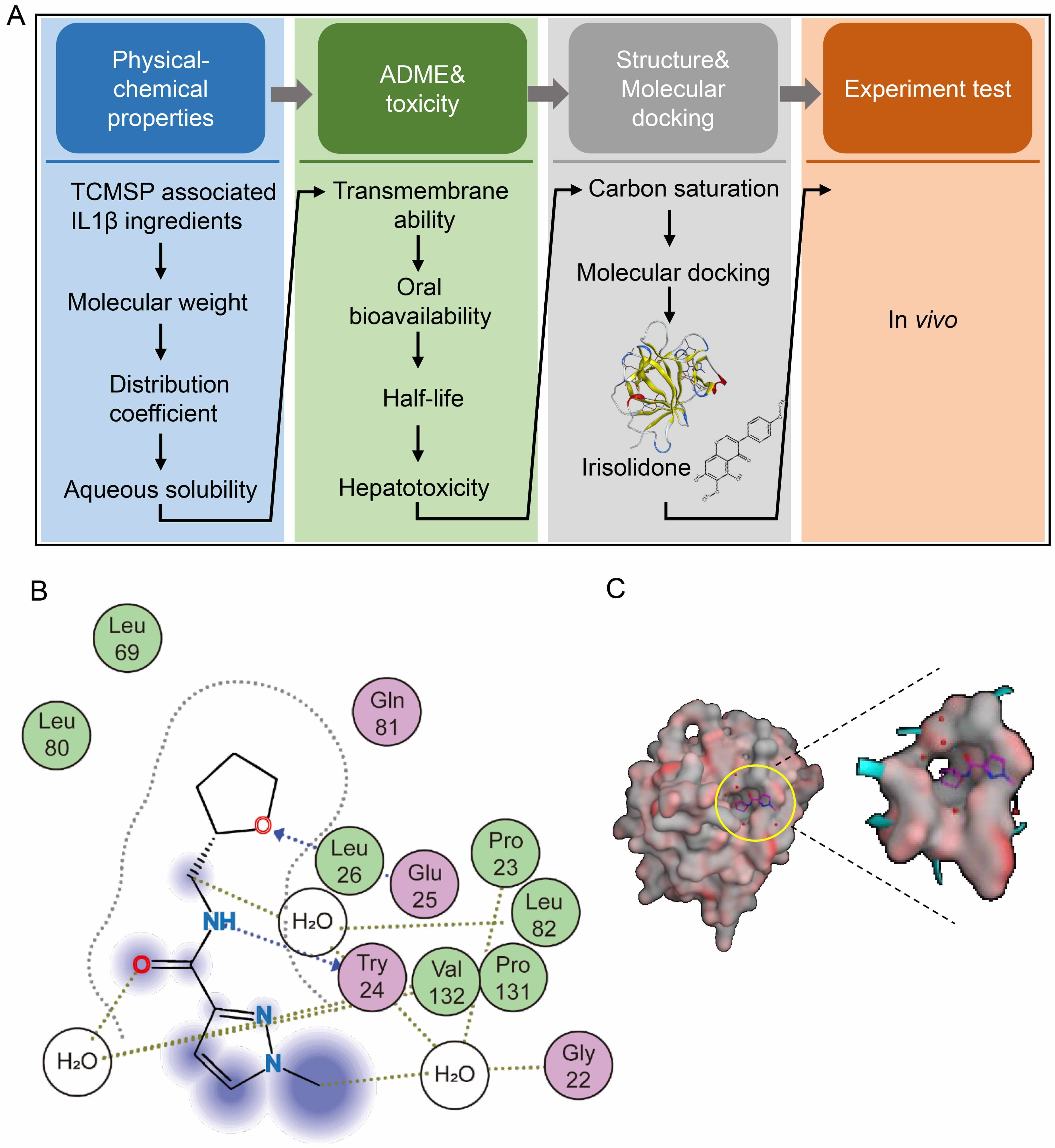

To identify natural compound inhibitors of IL1

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Identification of Irisolidone as a natural compound inhibitor of

IL1

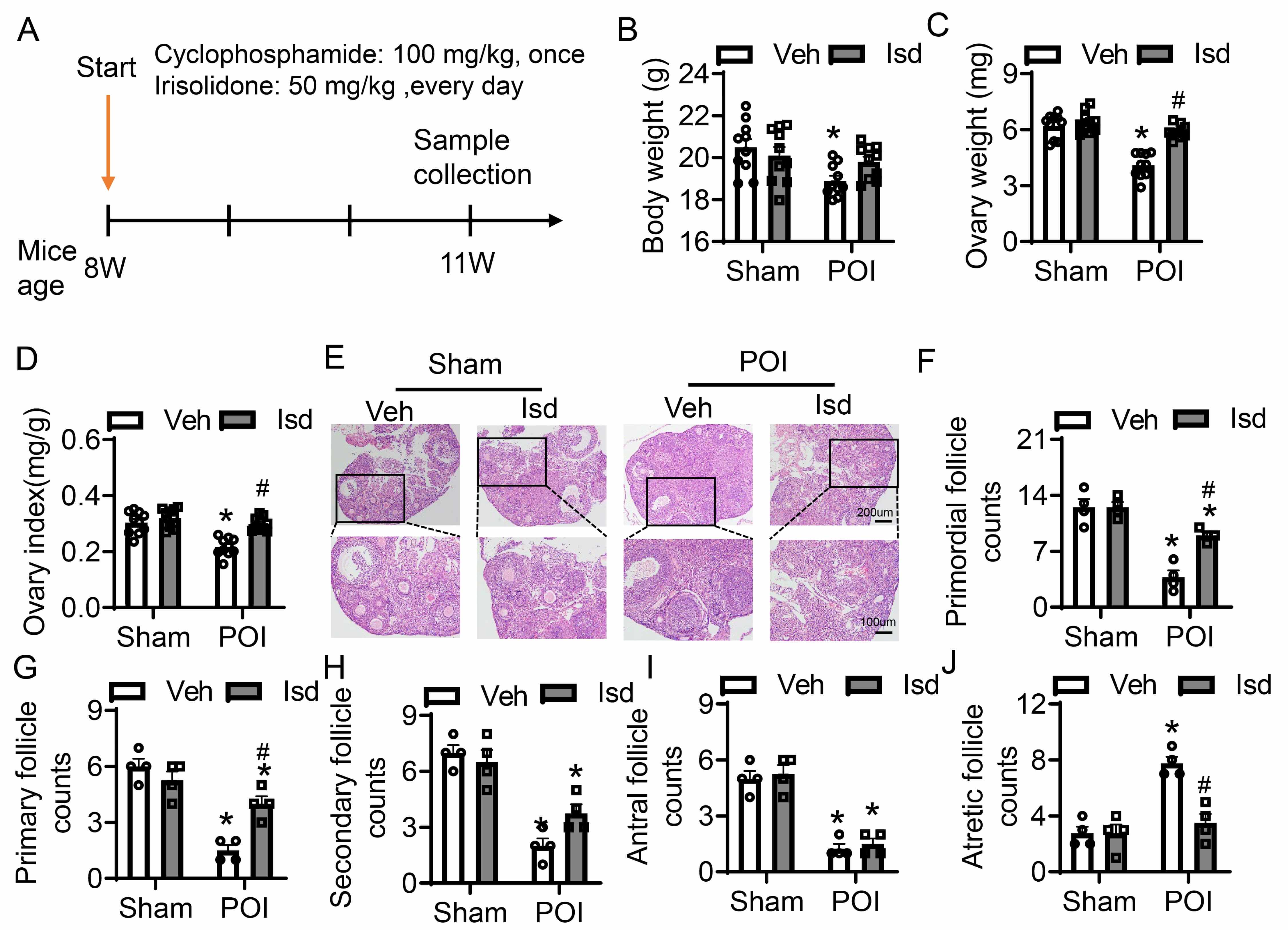

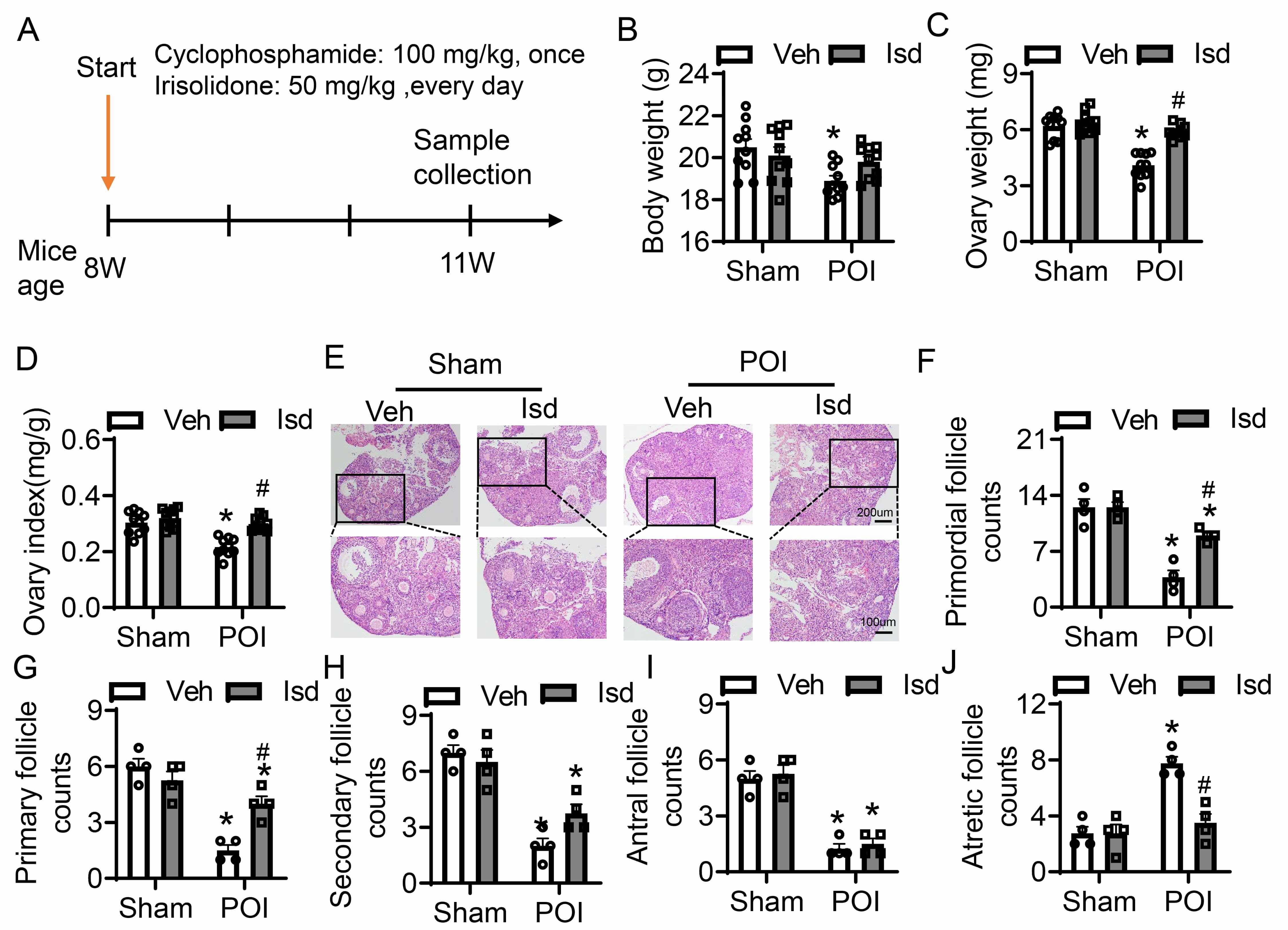

To establish a POI model, 8-week-old female mice were intraperitoneally injected with CTX at 100 mg/kg (Fig. 4A). Mice in the treatment group obtained daily oral administration of Irisolidone (50 mg/kg) for three weeks, after which samples were collected for subsequent analyses (Fig. 4A). Control mice received vehicle treatment only (Fig. 4A). Compared to untreated controls, the control group receiving Irisolidone showed no significant changes in body weight or ovarian weight (Fig. 4B–D). In contrast, the POI group exhibited an obviously reduction in both body weight and ovarian weight relative to the group. However, Irisolidone treatment significantly improved these parameters, restoring body weight, ovarian weight, and the ovarian index (ratio of ovarian weight to body weight) to near-normal levels (Fig. 4B–D). H&E staining of ovarian tissues revealed abnormal morphology and a reduced number of healthy follicles in the CTX-induced group (Fig. 4E). Irisolidone treatment obviously ameliorated histological damage, preserving ovarian structure and function. We quantified follicles at different developmental stages: primordial, primary, secondary, antral, and atretic follicles. The POI group showed a marked reduction in primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicles, accompanied by a significantly increased in atretic follicles (Fig. 4F–J). These findings indicate that CTX treatment severely impaired ovarian tissue, leading to abnormal folliculogenesis and reduced fertility. Notably, Irisolidone treatment rescued the number of developing follicles, promoting normal follicular development and reducing the number of atretic follicles (Fig. 4F–J). In summary, experiments in vivo demonstrate that Irisolidone treatment significantly mitigates CTX-induced POI-related damage. Irisolidone improves body weight and ovarian weight, and restores ovarian function by promoting normal follicular development and reducing follicular atresia.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Irisolidone ameliorates ovarian folliculogenesis and development

with CTX-induced POI. (A) Schematic diagram of experimental design. (B–D) The

body weight (B), ovarian weight (C), and ovarian index (ratio of ovarian weight

to body weight) (D) in different groups of mice (n = 10). (E) H&E-stained

sections of ovarian tissues (n = 4, The black box is the partial magnified view).

Overview figure, scale bar = 200 µm; Magnified view, scale bar = 100 µm.

(F–J) The number of primordial follicles (F), primary follicles (G),

secondary follicles (H), antral follicles (I), and atretic

follicles (J) in ovarian sections from different groups of mice (n = 4). Data are

presented as mean

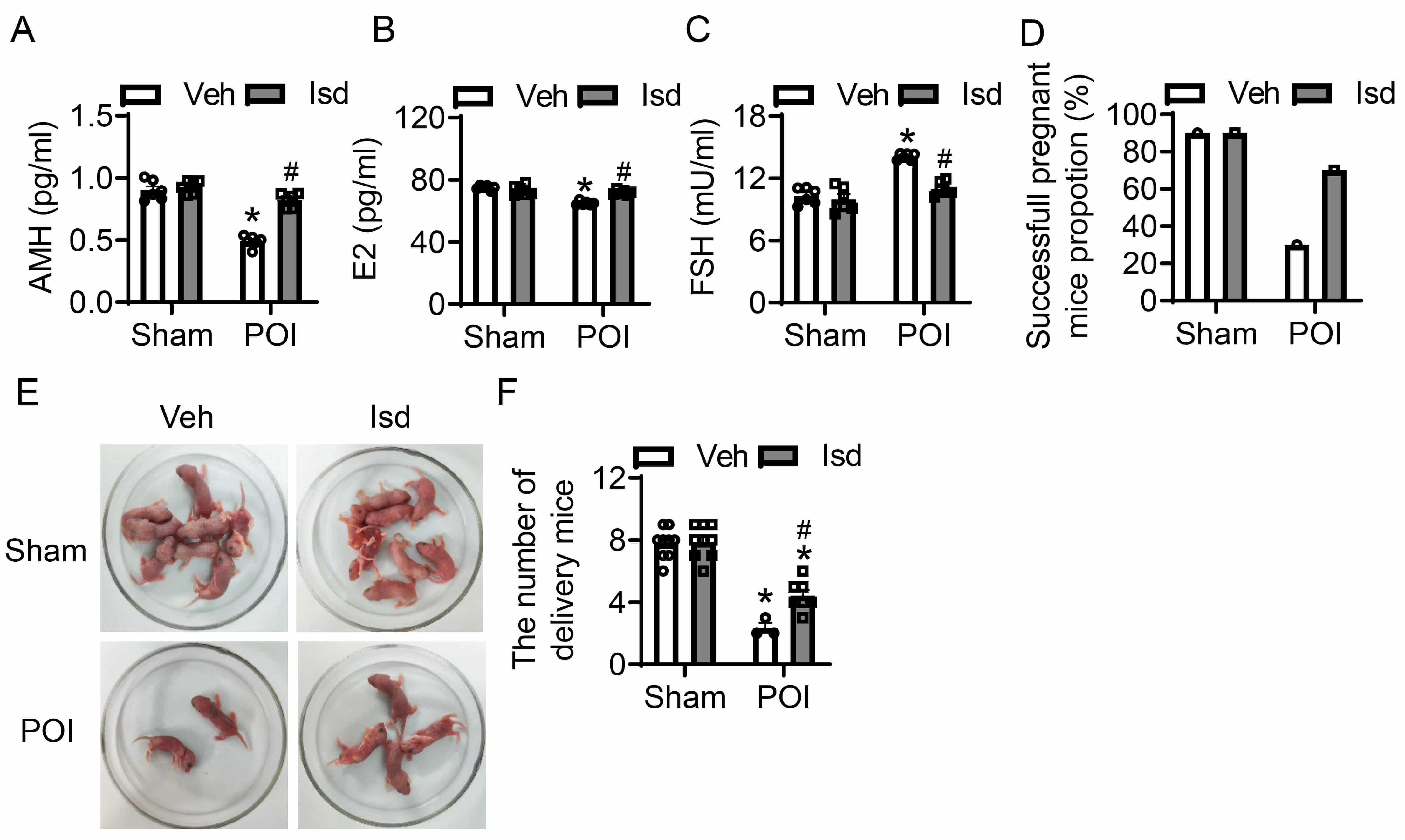

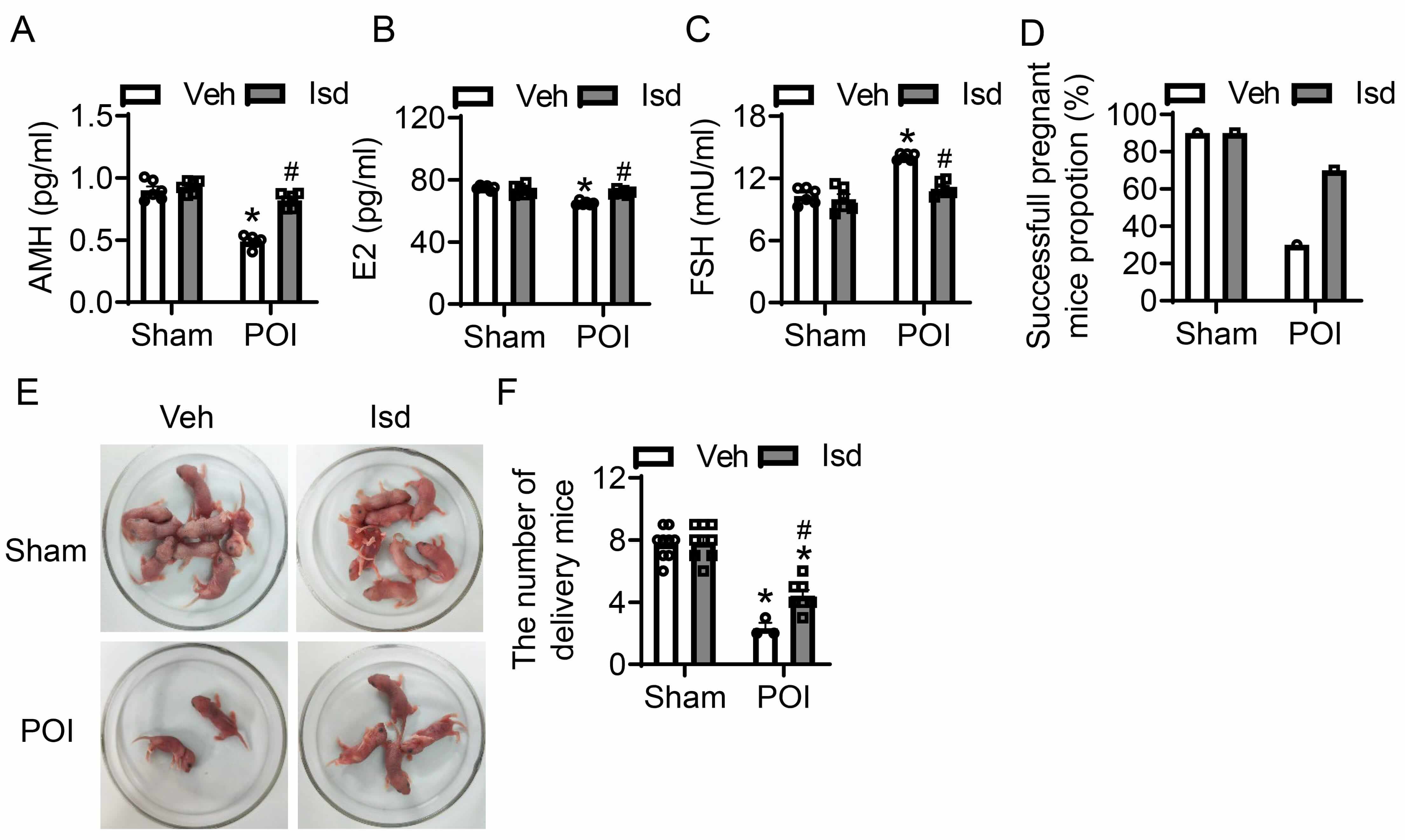

Structural abnormalities in ovarian tissue can exert a significantly impact ovarian function and fertility. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), anti-mullerian hormone (AMH), and estradiol (E2) are critical biomarkers for assessing ovarian function, reflecting ovarian reserve, follicular development, and ovulation, respectively. The combination of these three markers enables a comprehensive evaluation of ovarian health. For the purpose of assessing how CTX-induced POI affects ovarian function, we determined the serum levels of FSH, AMH, and E2 in mice through the application of ELISA. Additionally, we evaluated the pregnancy and fertility rates of female mice post-POI induction. In comparison with the control group, administration of CTX led to a significant reduction in serum AMH and E2 levels, whereas serum FSH levels were markedly elevated—findings that are indicative of a substantial decline in ovarian function (Fig. 5A–C). However, Irisolidone treatment significantly reversed these hormonal changes, restoring AMH, E2, and FSH levels to near-normal ranges, thereby improving ovarian function (Fig. 5A–C). To further characterize the effects of POI on reproductive, we assessed pregnancy and fertility in female mice after induction. Relative to controls, CTX treatment resulted in an obvious fall in pregnancy mice, with the count of pups born per pregnant mouse also being markedly decreased (Fig. 5D–F). In contrast, Irisolidone treatment significantly enhanced pregnancy incidence among female mice and elevated the count of pups born per litter (Fig. 5D–F). In summary, our findings demonstrate that Irisolidone possessed therapeutic potential for treating POI, and could provide a promising approach to reinstate ovarian physiological function and improve reproductive capacity in affected individuals.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Irisolidone restores ovarian function and improves reproductive

capacity in mice with CTX-induced POI. (A–C) The serum levels of anti-Müllerian

hormone (AMH) (A), estradiol (E2) (B), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (C)

measured by ELISA in different groups (n = 6). (D–F) The pregnancy rate (D),

Diagram representing the number of newborn mice (E), and litter counts (F) in

different groups. The number of mice used for each group is as follows:

Sham-Vehicle (n = 9), Sham-Irisolidone (n = 9), POI-Vehicle (n = 3), and

POI-Irisolidone (n = 7). Data are presented as mean

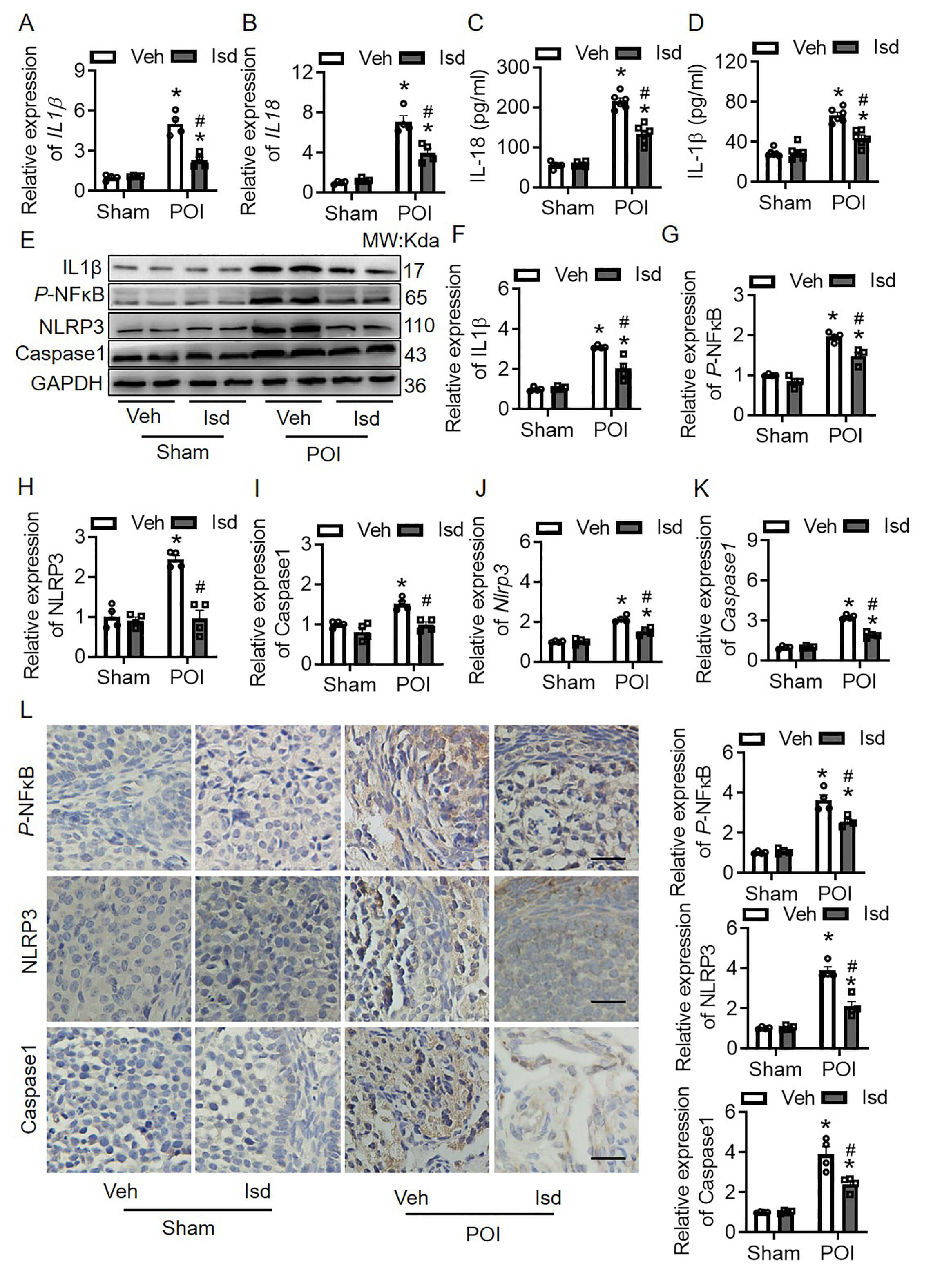

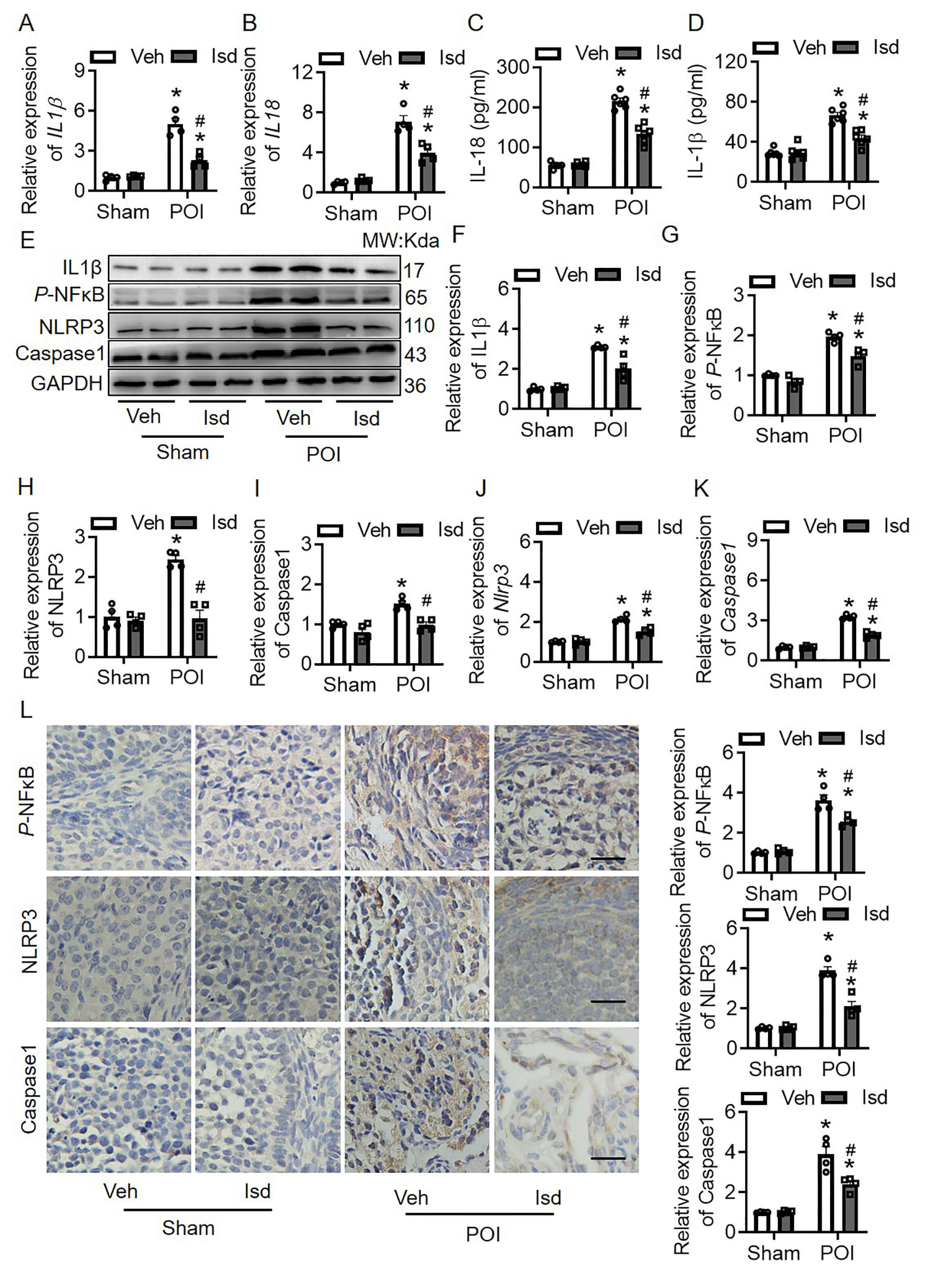

Previous pharmacological analysis identified IL1

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Irisolidone inhibits the dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines

by regulating NF

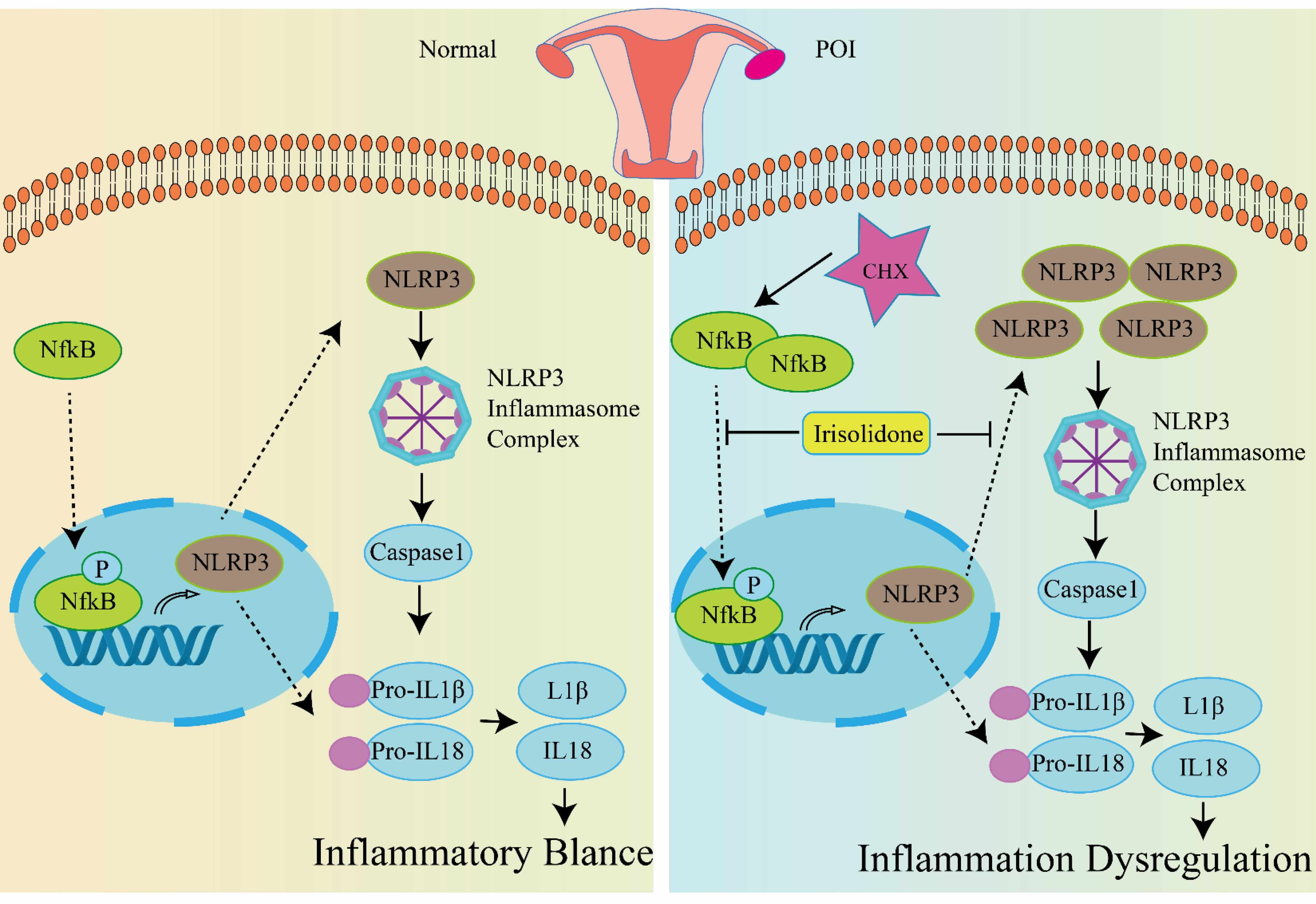

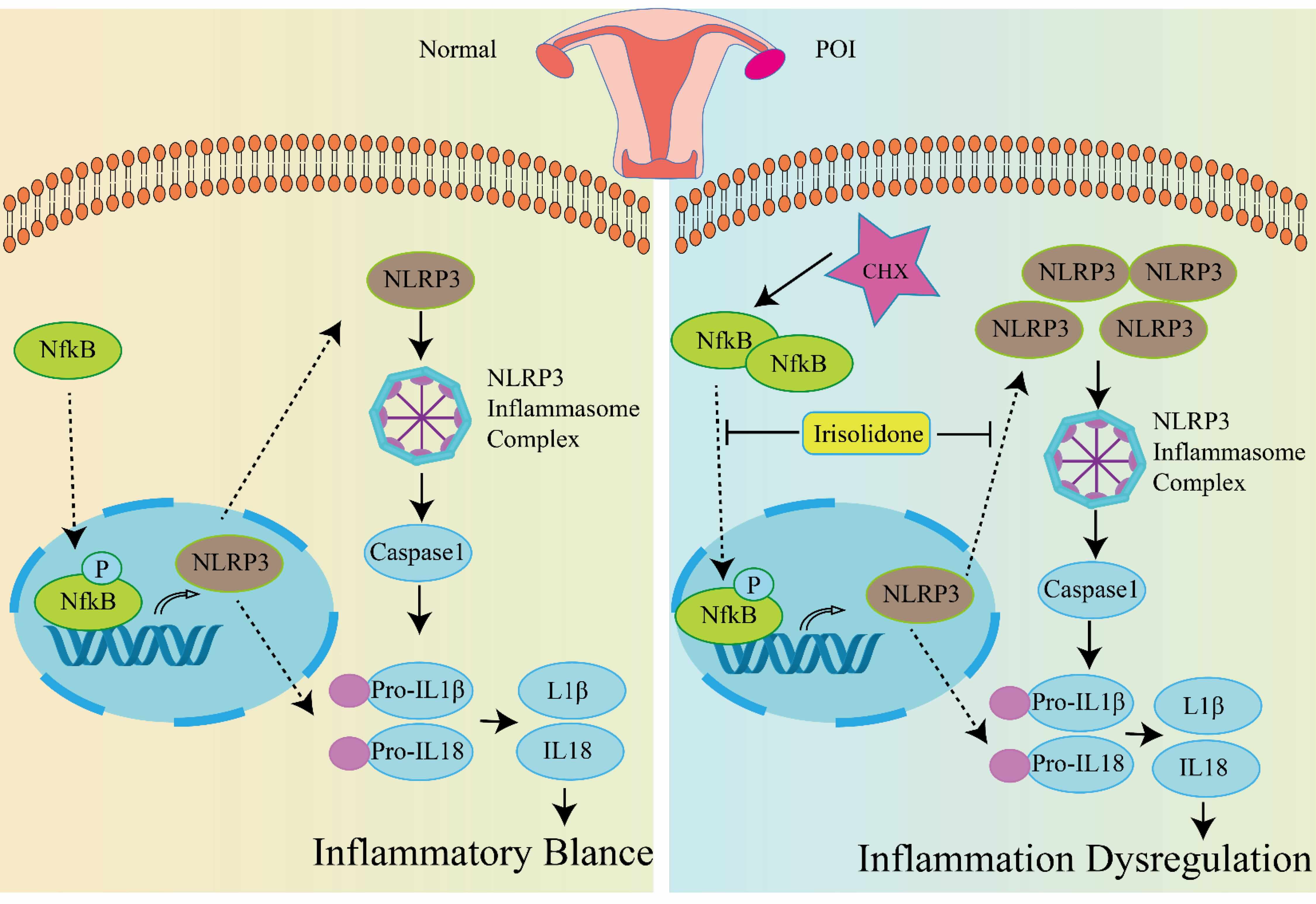

Our study focused on CTX induced POI, particularly the abnormal inflammation in

the ovaries. Through the intersection of RNA sequencing data (GSE128240) derived

from the ovarian tissues of CTX-treated mice and inflammation-related genes from

the GO database, we identified 25 candidate genes (Fig. 1). Subsequent PPI

analysis revealed IL1

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The underlying mechanism of Irisolidone protects against POI

caused by CTX. In healthy conditions, the inflammasome pathway maintains a

balanced state of inflammation within the body. Upon treatment with CTX, ovarian

tissue undergoes premature ovarian insufficiency (POI). CTX triggers the

phosphorylation of NF

Clinical anticancer therapeutic regimens frequently contribute to the development of POI and subsequent infertility [23]. Commonly used chemotherapeutic agents include cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin [24, 25]. Our study specifically focused on POI induced by cyclophosphamide, and whether Irisolidone can mitigate POI caused by other chemotherapy drugs remains to be determined. Cyclophosphamide-induced POI is influenced by multiple factors, including DNA damage [26], oxidative stress, cellular senescence [27], apoptosis [28], mitochondrial autophagy [29], and pyroptosis [30]. While our research has concentrated on the abnormal inflammation in the ovaries caused by CTX, the potential of Irisolidone to address other pathogenic factors induced by CTX, such as those mentioned above, requires further investigation.

Through network pharmacology approaches and molecular docking simulations, we

identified Irisolidone as a potential drug candidate. Nevertheless, the binding

energy between Irisolidone and the inflammatory cytokine IL1

Our findings indicate that Irisolidone can inhibit the CTX-induced elevation of

p-NF

To conclude, our study confirmed that Irisolidone is effective in treating

CTX-induced POI. By inhibiting the activation of p-NF

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The RNA sequencing data of CTX-Induced POI was from GEO data (GSE128240).

SYM designed the study. MJL, ZHW, XHC, HFW, XH, YPP performed the experiments and collected data. JYC established the animal model. MJL wrote the paper and SYM revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal experiments were followed the NIH guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23; revised 1978). All animal experiment were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethical Inspection Form at Guizhou Medical University (No. 12403436). We confirm the authenticity of this statement.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by Healthcare Research Project of Gansu Province (GSWSKY2022-17) and Research fund project of Gansu Provincial Hospital (20GSSY4-40).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.