1 Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Intelligent Cancer Biomarker Discovery and Translation, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 The First School of Medicine and the School of Information and Engineering, Wenzhou Medical University, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

3 Department of Clinical Nutrition, Wenzhou People’s Hospital & Wenzhou Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

4 Wenzhou Key Laboratory of Biophysics, Wenzhou Institute, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

5 Department of Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77001, USA

6 Department of Nephrology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

7 Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

8 Geriarics Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, 325035 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Peritoneal fibrosis is a significant complication arising from long-term peritoneal dialysis (PD), primarily due to the loss of peritoneal mesothelial cells (PMCs). Recent studies have implicated periostin (POSTN) in the progression of various fibrotic diseases; however, its specific role in PD-induced peritoneal fibrosis remains unclear. Sodium alginate (SA) microgels have emerged as promising carriers for cell encapsulation in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. This study investigated the therapeutic potential of PMCs encapsulated in SA microgels (SA/PMC) for reducing PD-induced peritoneal fibrosis, with a focus on the modulation by the periostin/nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB)/CXCL8 signaling pathway.

Primary human peritoneal mesothelial cells (PHPMCs) were isolated from the PD effluent of patients. The effect of SA encapsulation on PMCs proliferation was evaluated using a Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8) assay. The expression levels of POSTN, NF-κB p65, and CXCL8, as well as fibrosis markers, including α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen I, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and fibronectin, were evaluated in patients undergoing PD and a PD mouse model.

Patients undergoing PD for 1 year exhibited elevated levels of POSTN, NF-κB p65, CXCL8, and fibrosis markers compared with those undergoing PD for 1 week.

Consistent results from in vivo and in vitro models demonstrated that PD and hyperglycemic conditions upregulated the expression of POSTN, NF-κB p65, CXCL8, and profibrotic markers, leading to peritoneal thickening and fibrotic progression. Treatment with SA/PMC microgels ameliorated these effects. By modulating the POSTN/NF-κB/CXCL8 pathway and enhancing PMCs survival, SA/PMC microgels may have therapeutic potential in mitigating peritoneal fibrosis in PD patients.

Keywords

- sodium alginate

- microgels

- periostin

- peritoneal fibrosis

- peritoneal dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is widely utilized as a primary renal replacement therapy, benefiting an increasing number of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1]. However, peritoneal fibrosis remains a significant and prevalent complication in patients undergoing long-term PD, severely compromising therapeutic effectiveness and quality of life [2]. Clinical observations indicate that approximately 50–80% of patients who undergo PD for more than two years develop varying degrees of peritoneal fibrosis, ultimately leading to technique failure and increased morbidity [3].

A critical factor underlying PD-associated peritoneal fibrosis is the continuous

damage and loss of peritoneal mesothelial cells (PMCs). These cells play a

crucial role in maintaining peritoneal integrity and function, including

anti-inflammatory effects, fibrinolysis, and tissue repair [4]. During PD,

repetitive mechanical stress and continuous exposure to hypertonic, glucose-based

dialysis solutions induce injury and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

This is characterized by significant increases in the expression of

fibrosis-related proteins such as

Mesothelial cell transplantation represents a promising therapeutic approach for peritoneal fibrosis, demonstrating potential in the regeneration of damaged peritoneal tissues [8, 9]. However, conventional PMC transplantation faces several significant challenges, including limited cell viability, rapid cell loss, and poor targeted delivery within the peritoneal cavity, thus restricting clinical applicability. To overcome these limitations, recent advances in biomaterial science have shown considerable promise, in particular the use of sodium alginate (SA)-based microencapsulation technologies [10, 11]. SA is a naturally derived biocompatible and biodegradable polysaccharide that is increasingly utilized in cell transplantation due to its protective and proliferation-promoting properties [12].

Sodium alginate, a natural polysaccharide from brown algae, is highly valued in biomedical engineering for its excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability. Research shows that in animal models, alginate microcapsules act as a protective shield, effectively isolating transplanted islet cells from immune rejection and enabling them to maintain long-term blood sugar control [13]. A clinical study led by Anil Dhawan’s team [14] further demonstrated the safety and feasibility of this approach. They successfully used alginate microcapsules to transplant human liver cells into eight children with acute liver failure. In spinal cord injury treatment, scientists are using advanced 3D printing to create structured alginate hydrogel scaffolds. These scaffolds not only provide physical support but also actively boost the function of the body’s own neural stem cells, encouraging repair [15]. Together, these advances highlight the promising potential of sodium alginate as a cell carrier for treating a range of diseases through regenerative medicine.

This study seeks to elucidate the therapeutic efficacy and mechanistic basis of PMCs encapsulated in SA (SA/PMC) in mitigating peritoneal fibrosis induced by PD. We employed high-glucose-induced in vitro EMT models and in vivo murine models of peritoneal fibrosis to evaluate targeting efficiency, cell viability, inflammatory responses, and the expression of fibrosis-related proteins. The findings of this study have significant potential for developing a novel, cell-based therapeutic strategy that addresses the limitations of conventional PMC transplantation. This should ultimately improve clinical outcomes, extend peritoneal functional lifespan, and enhance the prognosis and quality of life for PD patients.

SA microgels were prepared following established protocols [16, 17]. A

calcium-EDTA (Ca-EDTA) complex was formulated by combining calcium chloride and

disodium EDTA in a 1:1 molar ratio, and adjusting the pH to 7.4 using sodium

hydroxide. The aqueous phase consisted of 1% SA (MACKLIN, Shanghai, China) and

50 mM Ca-EDTA dissolved in distilled water, followed by filtration through a 0.22

µm syringe filter (FMC201030, JETBIOFIL, Guangzhou, China). For cell-laden

microgels, primary human PMCs (PHPMCs) at a density of 5

The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical

University (Acceptance number: KY2024-R179). The research adhered to Good

Clinical Practice guidelines and followed the principles of the Declaration of

Helsinki. PHPMCs were isolated from PD effluent of patients undergoing dialysis

at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Inclusion

criteria were: (1) absence of peritonitis during PD; (2) regular PD follow-up;

(3) age between 40 and 60 years; (4) no malignant tumors; (5) no ascites; and (6)

signed informed consent. No statistically significant disparities in age, gender,

or educational background were observed across the participant cohorts

(p

In vitro models were established as follows: (1) the control (Con) group: PHPMCs cultured in DMEM/F12 medium for 96 h; (2) the high glucose (G) group: HPMCs cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 60 mM glucose for 48 h to induce fibrosis, followed by replacement with normal DMEM/F12 medium for an additional 48 h; (3) the high glucose+SA (G+SA) group: PHPMCs cultured in high-glucose medium (60 mM) for 48 h, followed by co-culture with freshly prepared blank SA microgels for an additional 48 h (total 96 h); (4) the high glucose+SA/PMC (G+SA/PMC) group: PHPMCs cultured in high-glucose medium (60 mM) for 48 h, followed by co-culture with freshly prepared SA microgels encapsulating additional PHPMCs for another 48 h (total 96 h). Since PHPMCs are non-immortalized cells, they were used after 5–7 passages in both the in vivo and in vitro experiments.

Cell proliferation was assessed using the CCK-8 assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai,

China). PMCs were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5

BALB/c nude mice (male, 8 weeks old) were provided by Charles River Laboratory

Animal Technology Co., Ltd (Zhejiang, China). The mice were housed under standard

laboratory conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle, a temperature of 22

To begin the terminal sampling procedure, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane

vapor. Induction used 3–5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen (via nose cone or

chamber), with a 1–3% concentration to maintain anesthesia. The depth of

anesthesia was monitored every 2–3 minutes by checking foot-pinch reflexes and

breathing rate. Throughout the process, the mice rested on a heating pad for

thermoregulation, and eye lubricant was applied to prevent dryness. Since this

was a terminal procedure, no post-operative pain management was needed. Once a

surgical plane of anesthesia was achieved, we immediately performed cardiac blood

collection, perfusion, or organ collection. For euthanasia, we used CO2 inhalation (

Harvested tissue specimens, including those from the liver, heart, lung, kidney, and peritoneum, underwent fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for a duration of 48 h. Fixed tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm using a microtome. Deparaffinization of tissue sections was carried out using xylene, followed by rehydration via a graded ethanol series, and culminating in immersion in distilled water. H&E staining was performed according to the instructions provided in the stain kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 minutes to visualize nuclei, then rinsed in running tap water. Eosin staining was performed for 2 minutes to stain the cytoplasm and extracellular matrix. Stained sections were dehydrated through increasing ethanol concentrations, cleared in xylene, and mounted with a coverslip using a synthetic resin. Images were captured using a Leica microscope (VT1000S, Shanghai, China). All experiments were repeated at least in triplicate.

MASSON staining was performed using a stain kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and following the manufacturer’s protocol. Sections were immersed in Bouin solution overnight at 37 °C, then rinsed with running water until the yellow color disappeared. The sections were subsequently stained with aniline blue for 2 minutes and briefly rinsed with water. Mayer’s hematoxylin was applied for 2 minutes, followed by a brief water rinse. The sections were differentiated in acidic ethanol for a few seconds and washed in running water for 10 minutes. Biebrich scarlet-acid fuchsin was applied for 10 minutes, the sections were then briefly rinsed with distilled water, followed by treatment with phosphomolybdic acid solution for about 10 minutes. Without washing, the aniline blue solution was directly applied for 5 minutes. The sections were subsequently treated with a weak acid solution for 2 minutes and quickly dehydrated in 95% ethanol. They were then dehydrated in absolute ethanol three times, each for 5–10 seconds, followed by clearing in xylene three times, each for 1–2 minutes. Finally, the sections were mounted with neutral resin, and images were captured using a Leica microscope. All experiments were repeated at least in triplicate.

Immunohistochemical analysis was conducted on tissue sections prepared from

paraffin-embedded samples. The 4 µm slices were dewaxed in xylene and

hydrated with graded ethanol solutions. Antigen retrieval was performed with

citrate buffer, followed by treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Subsequently,

sections were blocked with goat serum for 1 h. The tissue sections were then

incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including anti-periostin

(POSTN) (1:100, DF6746, Affinity, Jiangsu, China), anti-nuclear factor

kappa-B (NF-

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 µm) were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol solutions. Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Cell samples were washed three times with PBS and the cells then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Both tissue and cell samples were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with goat serum for 1 h. Samples were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with one or two primary antibodies from different sources. After washing with PBS, samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with corresponding secondary antibodies, such as Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit (A-11008, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse (A-11005, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Solarbio) was used for nuclear visualization. Images were captured using a KFBIO digital pathology slide scanner (KF-PRO-005, KFBIO, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China). All experiments were repeated at least in triplicate.

Animal tissue samples were homogenized using a tissue homogenizer in radio

immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China)

containing 0.1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cells were lysed using

RIPA lysis buffer with 0.1% PMSF. The homogenized cell lysates were sonicated at

30 Hz for 3 seconds, repeated three times. Both cell and animal tissue samples

were then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4 °C, and the supernatant

collected for protein analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using a

protein quantification kit. Protein samples were prepared with a 5

Total RNA was extracted from tissue or cell samples using a commercially available RNA extraction kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a spectrophotometer (DS-11 FX/FX+, Denovix, Wilmington, DE, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA with a reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted on a QuantStudio 5 instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) using SYBR Green chemistry. Relative gene expression levels were determined with the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method, and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (internal reference gene). All experiments were repeated at least in triplicate.

Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized to

generate bar charts and conduct statistical analyses. Data conforming to a normal

distribution are expressed as the mean

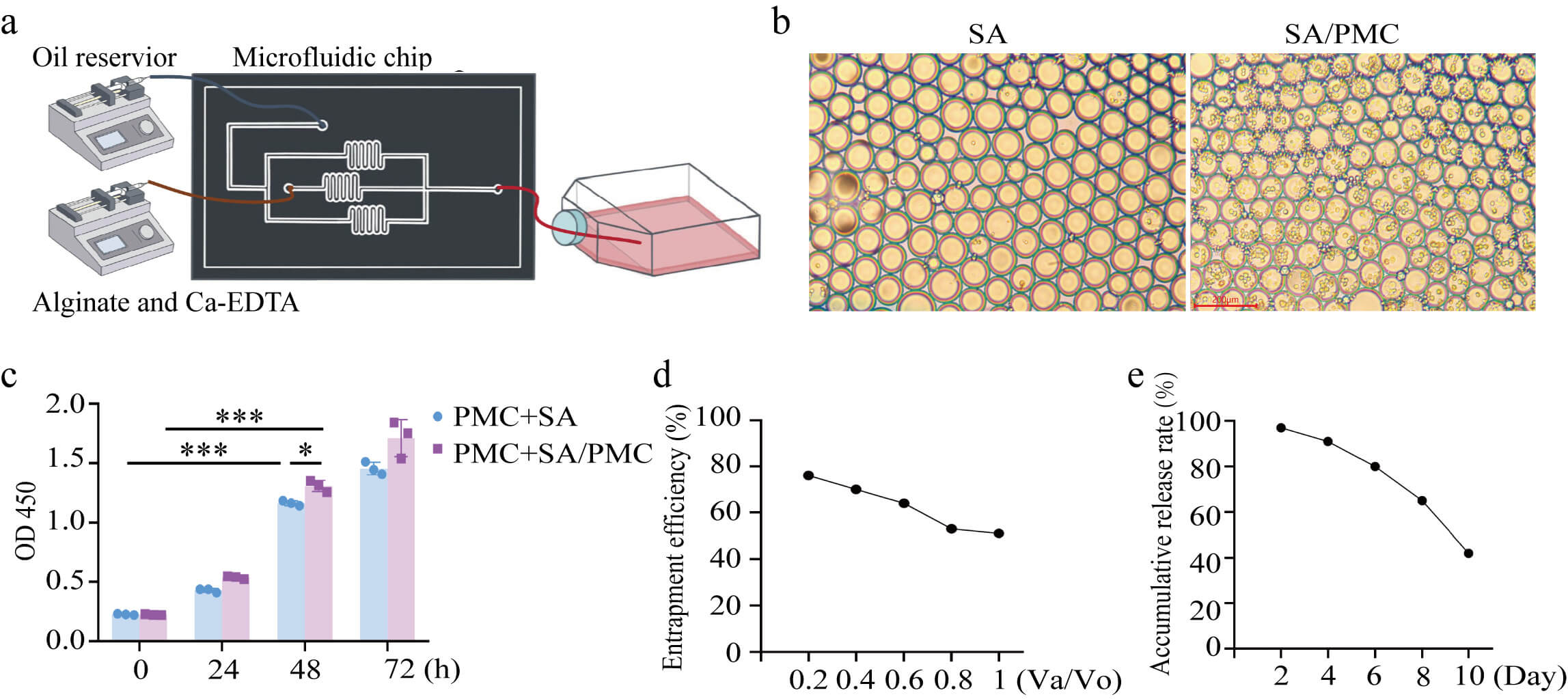

The production process for SA microgels is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Optical microscopy revealed the diameter of SA microgels ranged from approximately 60 to 100 µm (Fig. 1b). Encapsulation of PHPMCs within SA (SA/PMC) did not significantly alter the microgel diameter. CCK-8 assays demonstrated a significant increase in PMC proliferation after 48 h of co-culture with both SA and SA/PMC. Moreover, SA/PMC exhibited accelerated cell proliferation compared to the SA-only group (Fig. 1c). As the ratio of the aqueous phase to the oil reservoir flow rate (Va/Vo) increases, the entrapment efficiency shows a downward trend (Fig. 1d). Meanwhile, with the extension of time, the cumulative release rate gradually rises, reflecting that this hydrogel has a certain time dependence in substance release (Fig. 1e). These findings suggest that SA microgels effectively encapsulate PHPMCs and facilitate their release, thereby enhancing cell proliferation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Characteristic of sodium alginate (SA) microgel. (a) Production

of SA microgel. (b) Microstructure of the SA and SA microgels encapsulating

peritoneal mesothelial cells (SA/PMCs). Scale bar = 200 µm. (c) Cell

counting kit 8 (CCK-8) OD values at 450 nm for primary human peritoneal PMCs

co-cultured with SA (PMC+SA), and primary human PMCs co-cultured with SA/PMC

(PMC+SA/PMC). (d) Cell encapsulation efficiency under different aqueous and oil

phase flow rates (Va/Vo). (e) Cumulative cell release rate. All data are

presented as the mean

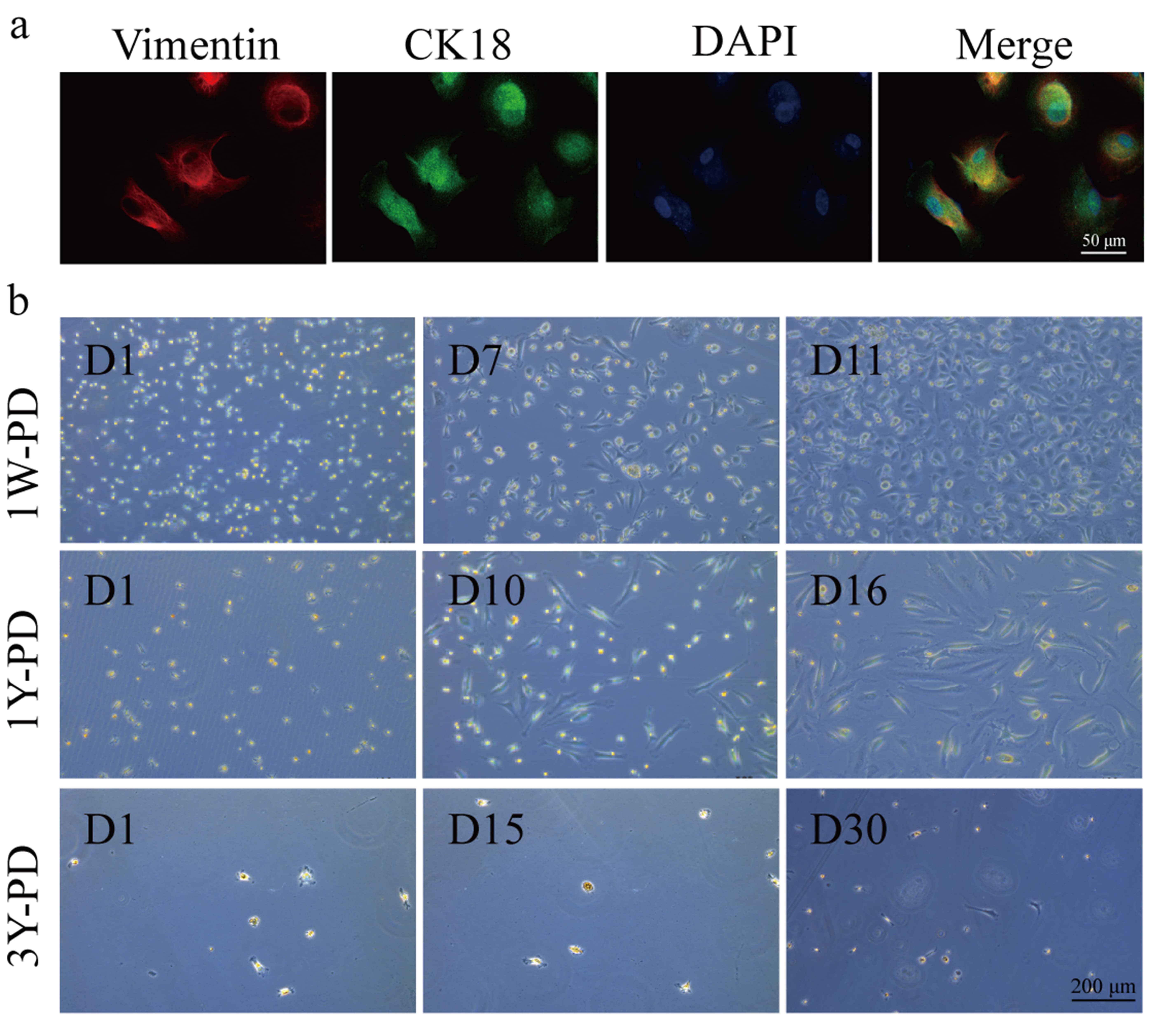

Co-staining with cytokeratin 18 (CK18) and vimentin confirmed the identity of cells isolated from PD fluid as PHPMCs (Fig. 2a). PD fluid was collected from patients with PD durations of 1W, 1Y, and 3Y. A high number of PHPMCs was collected in the 1W-PD group, with these cells displayed a cobblestone-like morphology when cultured for 11 days. In contrast, fewer PHPMCs were found in the 1Y-PD group, with the cells undergoing EMT characterized by transition from a cobblestone-like to a spindle-shaped morphology. The 3Y-PD group showed even fewer PHPMCs, with the cells losing their proliferative ability almost entirely (Fig. 2b). These observations indicate that prolonged PD may lead to cell fibrosis and induce EMT.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Reduced proliferative capacity of PHPMCs was associated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in long-term peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. (a) Representative immunofluorescence images of markers vimentin and cytokeratin 18 (CK18) in PHPMCs. Scale bar = 50 µm. (b) The growing images of PHPMCs of PD patients for 1 week (1W-PD), 1 year (1Y-PD), and 3 year (3Y-PD). Scale bar = 200 µm. D, day.

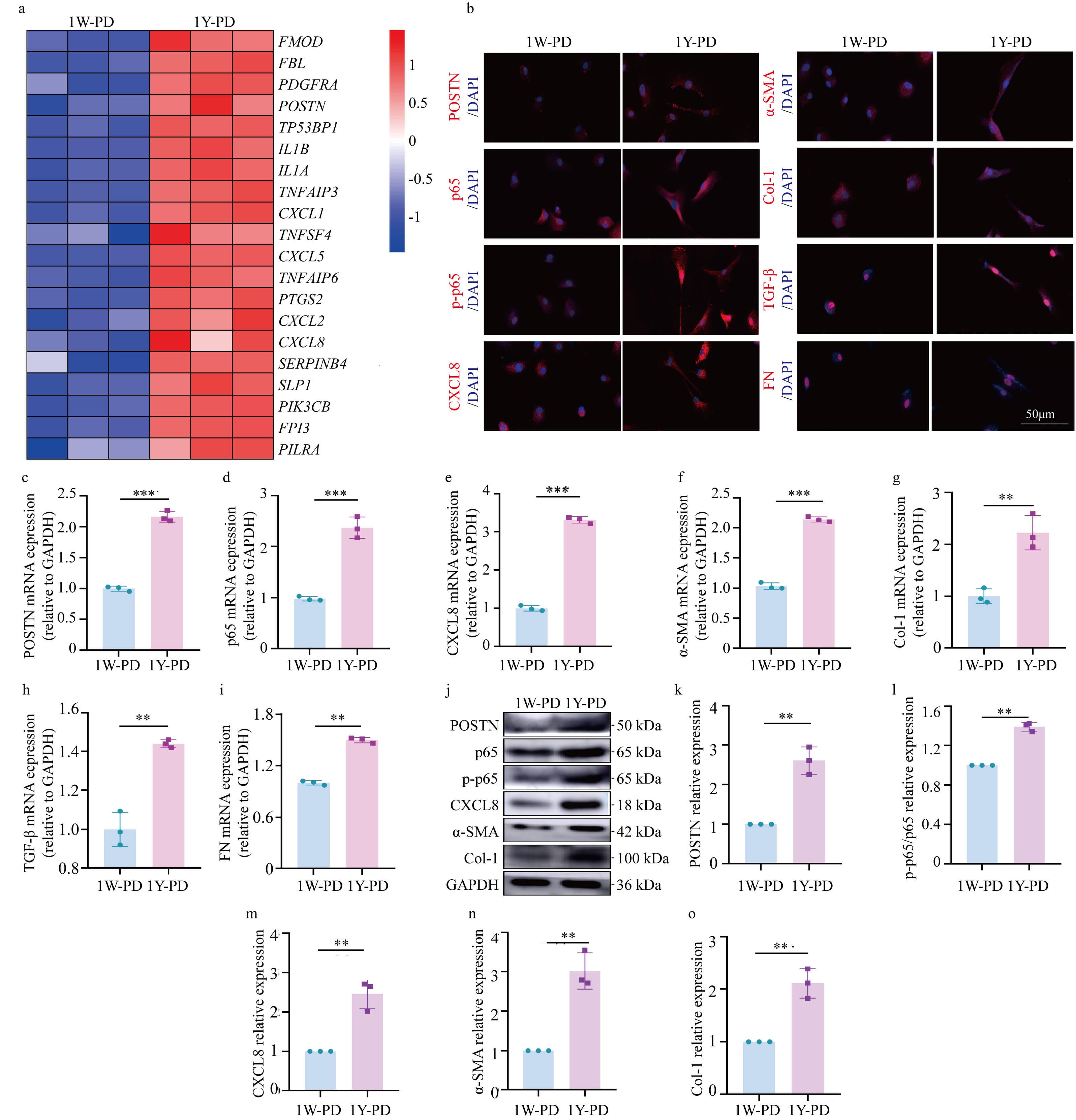

To investigate the mechanisms underlying peritoneal fibrosis in long-term PD

patients, PHPMCs were isolated from PD fluid of patients undergoing dialysis for

1W and 1Y. According to the sequencing results, POSTN and CXCL 8 were increased

in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis for 1 year (Fig. 3a).

Immunofluorescence staining indicated a marked upregulation of POSTN expression

in the 1Y-PD group relative to the 1W-PD cohort. NF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Increased expression of periostin/nuclear factor kappa-B/C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 8 (POSTN/NF-

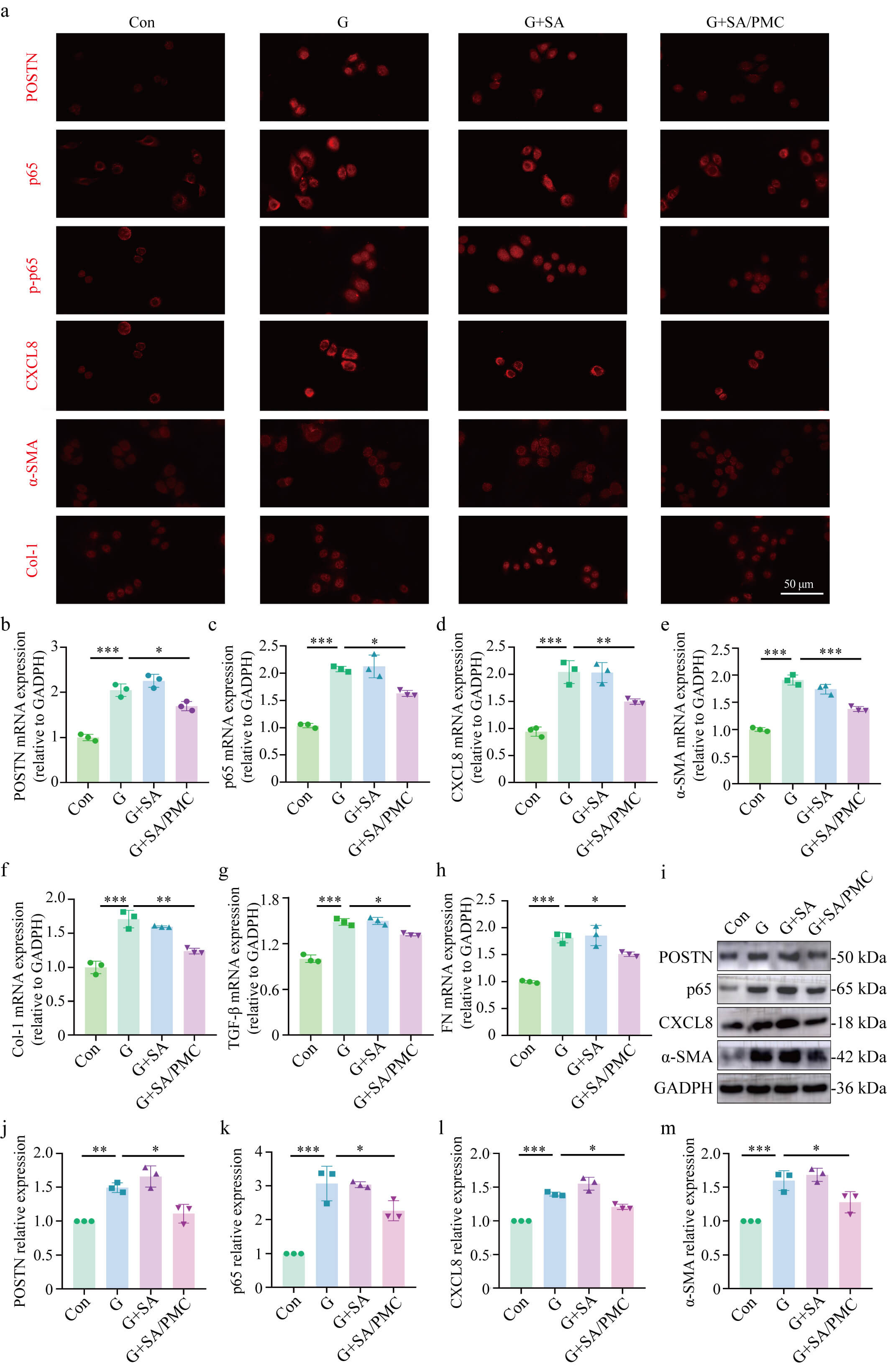

Primary human PMCs were cultured in a 60 mM high glucose medium to examine the

role of elevated POSTN expression in fibrosis under high glucose conditions.

Immunofluorescence staining revealed increased POSTN expression in the G and G+SA

groups, whereas the G+SA/PMC group showed reduced POSTN expression. Similarly,

NF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

SA/PMC reduces the high glucose-induced increase in

POSTN/NF-

A murine model of PD was used to further investigate the involvement of POSTN in

peritoneal fibrogenesis. MASSON staining indicated significant peritoneal

fibrosis in the PD, PD+SA, and PD+PMC groups, whereas the PD+SA/PMC group showed

reduced fibrosis (Fig. 5a). Additionally, the peritoneal thickness was

significantly greater in the PD and PD+SA groups compared to the control group,

but significantly smaller in the PD+SA/PMC group compared to the PD and PD+PMC

groups (Fig. 5b). Immunohistochemical assessment indicated elevated POSTN

expression in the PD group, which was substantially attenuated in the PD+SA/PMC

treatment group. Importantly, POSTN expression in the PD+SA/PMC group was lower

than in the PD+PMC group. Similarly, the levels of NF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Increased expression of POSTN/NF-

To evaluate the biosafety of SA microgels, blood and tissue samples were

collected from the various groups of PD mice. Hemolysis tests indicated that

adding SA to mouse blood resulted in a hemolysis rate of

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Biosafety of SA microgels. (a) Images of hemolysis

test and hemolysis rate. (b) Body weight of mice before and after PD. (c) Alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) level of PD mice. (d) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

level. (e) Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level. (f) Serum creatinine (Scr)

level. (g) Glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). (h–k) Representative H&E and

MASSON images of liver, heart, lung, and kidney. All data are presented as the

mean

This study explored the therapeutic efficacy of SA/PMC microgels in attenuating peritoneal fibrosis associated with long-term PD. Our findings demonstrated successful encapsulation of PHPMCs in SA microgels, which maintained cell proliferation without significantly altering the microgel diameter. The CCK-8 assay further validated that encapsulated PMCs exhibited improved viability and proliferation, highlighting the suitability of SA microgels as a cell delivery system to support cell growth and survival for peritoneal regeneration.

Peritoneal fibrosis is a significant complication of long-term PD, often

resulting from continuous exposure to hypertonic glucose-based dialysis

solutions, leading to PMC injury and EMT [18, 19]. This pathological process is

characterized by increased expression of fibrosis markers such as

Recent studies have highlighted the role of POSTN, a matricellular protein, in

the progression of CKD and its involvement in fibrotic processes [25, 26]. POSTN

has been shown to mediate kidney disease in response to TGF-

Our in vitro experiments demonstrated that high glucose stimulation of

PMCs led to increased POSTN/p65/CXCL8 expression and fibrosis, which were

significantly mitigated by SA/PMC treatment. This suggests that SA/PMC microgels

can effectively inhibit the high glucose-induced fibrotic response. Similarly,

in vivo studies with a mouse PD model further supported these findings,

with SA/PMC treatment significantly reducing peritoneal fibrosis, as evidenced by

decreased expression of POSTN, p65, p-P65, and CXCL8, and reduced thickness of

the peritoneal membrane. These results concur with previous reports that

targeting POSTN and the NF-

This study has several limitations. A key limitation of this study is the

absence of direct functional validation of the POSTN/NF-

In conclusion, our study suggests that SA/PMC microgels could represent a

promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating peritoneal fibrosis in PD patients.

By encapsulating PHPMCs and modulating the POSTN/NF-

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

SM, XY, CS, ChuZ and YZ conceived and designed the study. SM, CQ, JuZ, ZL, LW, YY, CS, YW and CC performed the experiments and collected the data. SM, CQ, JuZ, KZ, CheZ, YB snd YS analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors critically reviewed and contributed to manuscript revisions, read and approved the final version, fully participated in the work, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (Acceptance number: KY2024-R179). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The animal-study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Wenzhou Medical University Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee (approval No. WYYY-AEC-YS-2024-0547). All animal procedures strictly adhered to the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines, including the revised Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (UK) and Directive 2010/63/EU (EU).

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the members of the laboratory for their invaluable assistance and insightful discussions throughout this research.

This research was funded by Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation, grant number LTGY23H050003 and LTGY24H050004 and Wenzhou Committee of Science and Technology of China, grant number Y2023065.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.