1 Hebei Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Liver-Kidney Patterns, Hebei University of Chinese Medicine, 050200 Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

2 Department of Nephrology, Chuzhou Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital, 239054 Chuzhou, Anhui, China

3 Department of Pharmacy and Health Management, Hebei Chemical & Pharmaceutical College, 050026 Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

4 Institute of Integrative Medicine, College of Integrative Medicine, Hebei University of Chinese Medicine, 050200 Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

5 Department of Clinical Laboratory, School of Medicine, International University of Health and Welfare, 286-8686 Narita, Japan

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Lymphangiogenesis and phenotypic transformation of endothelial cells are closely associated with the progression of renal interstitial fibrosis. Inflammatory injury triggered by mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation serves as the initial stimulus for lymphangiogenesis.

Thirty specific pathogen-free (SPF) male C57BL/6 mice were assigned to three groups randomly: the control group (CON), aldosterone-treated group (ALD group, in which aldosterone was infused at a rate of 0.75 μg/h via mini-osmotic pumps for 12 weeks), and esaxerenone-treated group (ESA group, administered at a dosage of 1 mg/kg/day via diet). The expression levels of lymphatic markers (lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3), podoplanin, and VEGFC) were assessed using immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and western blot analysis. Inflammatory injury markers (CD68, F4/80, IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β1) and endothelial–to–mesenchymal transition (EndMT, LYVE-1+ vimentin/α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)+) were evaluated. In vitro, the effects of aldosterone on the migration, tube formation, and phenotypic transformation of human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLECs) in the presence of TGF-β1 or VEGFC were investigated.

In the ALD group, significant increases in lymphangiogenesis, macrophage infiltration, and the expression of TGF-β1, TNF-α, IL-1β and VEGFC were observed. Immunofluorescence double staining revealed that VEGFC was predominantly secreted by macrophages, and that lymphatic endothelial cells exhibited expression of vimentin and α-SMA. In vitro experiments demonstrated that aldosterone promoted HLECs migration and tube formation, as well as the activation of inflammatory cytokines and MR. Flow cytometry analysis indicated that HLECs underwent myofibroblastic transformation, which could be attenuated by MR blocker esaxerenone.

Aldosterone induces inflammatory injury, thereby promoting renal lymphangiogenesis and EndMT.

Keywords

- aldosterone

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- VEGFC

- lymphangiogenesis

- TGF-β1

- EndMT

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as the presence of abnormalities in

kidney structure or function that cause health consequences [1]. Renal

interstitial fibrosis (RIF) is a common pathological finding and the ultimate

manifestation of CKD [2]. RIF is characterized by abnormal deposition of

extracellular matrix and organ atrophy, and is related to cell proliferation,

apoptosis, and phenotypic transformation. Clinical and animal experiments have

shown that aberrant angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, especially inflammatory

lymphangiogenesis, are involved in RIF [3]. Renal biopsy samples from patients

with IgA nephropathy and diabetic kidney disease were labeled with the human

lymphatic vessel endothelial marker D2-40, and these samples exhibited a

significantly increased number of lymphatic drainage vessels, moreover, both the

quantity of lymphatics and the severity of RIF and inflammation were positively

correlated, and some lymphatic vessel endothelial cells underwent

myofibroblast-like transformation, secreted

Lymphangiogenesis is regulated by vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) of which VEGFC and VEGFD are the most important. In particular, VEGFC is a key factor in lymphangiogenesis. Renal VEGFC can be secreted by a variety of renal cells under physiological conditions, such as renal tubular epithelial cells, mesangial cells, vascular endothelial cells and fibroblasts under physiological conditions, with renal tubular epithelial cells serving as the predominant source. But during inflammatory injury, macrophages oversecrete VEGFC [6].

Aldosterone is well known to induce inflammatory and profibrotic factors that

cause kidney injury via activation of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) [7].

Previous studies have shown that aldosterone can induce renal injury with

abnormal neovascularization which is involved in fibrosis formation, mainly

mediated by VEGFA [8]. In this study, we also reported that inflammatory

lymphangiogenesis was associated with this process, and inflammatory cells,

especially macrophages, secreted VEGFC to promote lymphangiogenesis.

Additionally, the increase in lymphatic vessels led to disorganization of the

renal structure, while phenotypic transformation of lymphatic endothelial cells

was also involved in this process with aldosterone-infused group (ALD), a

mineralocorticoid that induces inflammatory damage. Whether aldosterone

stimulates renal lymphangiogenesis or participates in renal fibrosis remains

unknown. In this study, mice were continuously administered aldosterone to induce

MR-mediated inflammatory lymphangiogenesis and endothelial-to-mesenchymal

transition (EndMT) through the VEGFC and TGF-

The animal study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei University of

Chinese Medicine. Thirty specific pathogen-free (SPF) male C57BL/6 mice, weighing

24.7

Thirty mice were divided randomly into 3 groups: the control (CON) group, the ALD group (The mice were received continuous ALD infusion at 0.75 µg/h via a mini-osmotic pump and the pumps were replaced every 6 weeks for the entire duration of the study; CAS NO: 52-39-1, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and the esaxerenone-treated group (ESA group) (aldosterone infusion + esaxerenone administration via diet at a dosage of 1 mg/kg/day, kindly provided by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The mice were acclimatized and fed for 7 days before modeling. The mice were anesthetized via chamber induction with 4% isoflurane in 100% oxygen (1 L/min) until loss of righting reflex. Surgical anesthesia was maintained via nose cone with 1.5–2% isoflurane in oxygen (0.5 L/min), confirmed by absent pedal reflex and stable respiration. The modeling method has been described previously [8]. After twelve weeks, animals were initially anesthetized with a low concentration of isoflurane, followed by a rapid transition to a high concentration (5%) to induce immediate loss of consciousness, after which kidney tissue samples and blood were collected.

Renal pathological specimens were obtained as previously described [8].

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Masson staining, and immunohistochemistry

were performed with antibodies against F4/80 (1:100; Servicebio, Wuhan, China,

Cat# GB113373), CD68 (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab53444),

On H&E-stained slides, inflammatory cell infiltration and tubulointerstitial changes were graded semiquantitatively by two investigators in a blinded fashion. A 0–6 scoring scale was used to evaluate the two items, where scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 represented normal, mild, moderate, and severe conditions, respectively [9]. The percentage of the collagen positive area was semiquantitatively graded by Masson staining. The images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

The kidneys were perfused with saline, and dehydrated in 20% and 30% sucrose

solutions, and the OCT complex was frozen for immunofluorescence staining

(Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA). After being taken from the frozen samples, 6

µm kidney sections were stained with Alexa Fluor 555-coupled

Kidney tissues, RAW264.7 cells, and human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLECs)

were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing

protease inhibitors, and total protein was extracted. Protein samples were

separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS‒PAGE) and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes.

After blocking with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h, the membranes were

incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight:

vimentin (1:1000, Abcam, Cat# ab8978), IL-1

RAW264.7 (Cat# CL-0190, Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) was cultured as previously described [10]. HLECs (Cat# HUM-CELL-0053, PriCells, Wuhan, China) were cultured in endothelial cell medium (ECM, ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. The cells were maintained at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All the cell lines were validated by STR profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma.

RAW264.7 cells were divided into 3 groups: the CON group, ALD group (treated

with 10-7 mol/L ALD for 24 h), and ESA group (treated with 10-6 mol/L

esaxerenone 2 h before aldosterone treatment). HLECs were divided into 6 groups:

the CON group, the ALD group (treated with 10-7 mol/L aldosterone for 24 h),

the ESA group (treated with 10-6 mol/L esaxerenone 2 h before aldosterone

treatment), the TGF-

The processed RAW264.7 cell culture medium was centrifuged, and the supernatant

was collected for subsequent experiments, which were performed using a

quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique. Subsequently, 100 µL of

the supernatant was added to a microtiter plate, and the corresponding diluted

antibodies (VEGFC: CUSABIO, Wuhan, China, Cat#: CSB-E07361m; TGF-

A cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) assay (Abbkin, Wuhan, China, Cat# BMU106-CN) was

performed according to the protocol. HLECs were divided into the CON, ALD,

ALD+ESA, VEGFC, VEGFC+VEGFR-3-IN-1, and ALD+VEGFR-3-IN-1 groups. HLECs were

inoculated into 96-well plates (1

HLECs were inoculated into 6 cm dishes and cultured to confluence. Next, a scratched was created in the center of the confluent cells with a 200 µL pipette tip. After the cells were rinsed three times with PBS, an appropriate amount of complete medium was added. Images were acquired at 0 h and 8 h and quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Matrigel matrix (300 µL per well; BD Biocoat 356234, Corning Inc.,

Corning, NY, USA) was added to precooled 12-well plates, which were then

polymerized for 30 min at 37 °C. Following a 24-hour treatment period,

HLECs were resuspended in 300 µL of growth medium supplemented with

10% FBS and seeded onto the gelled Matrigel. After 3.5 h of standard incubation,

tube formation was examined and photographed under a

Twenty-four hours after treatment, the HLECs were harvested and stained with

PE-conjugated anti-VEGFR3 (1:100, Biolegend, Cat# 356204), APC-conjugated

anti-

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS statistics software (version

26.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). After normality assessment of the data via the

Shapiro-Wilk test, one-way ANOVA was performed followed by a least significant

difference test for multiple groups. The date are presented as the means

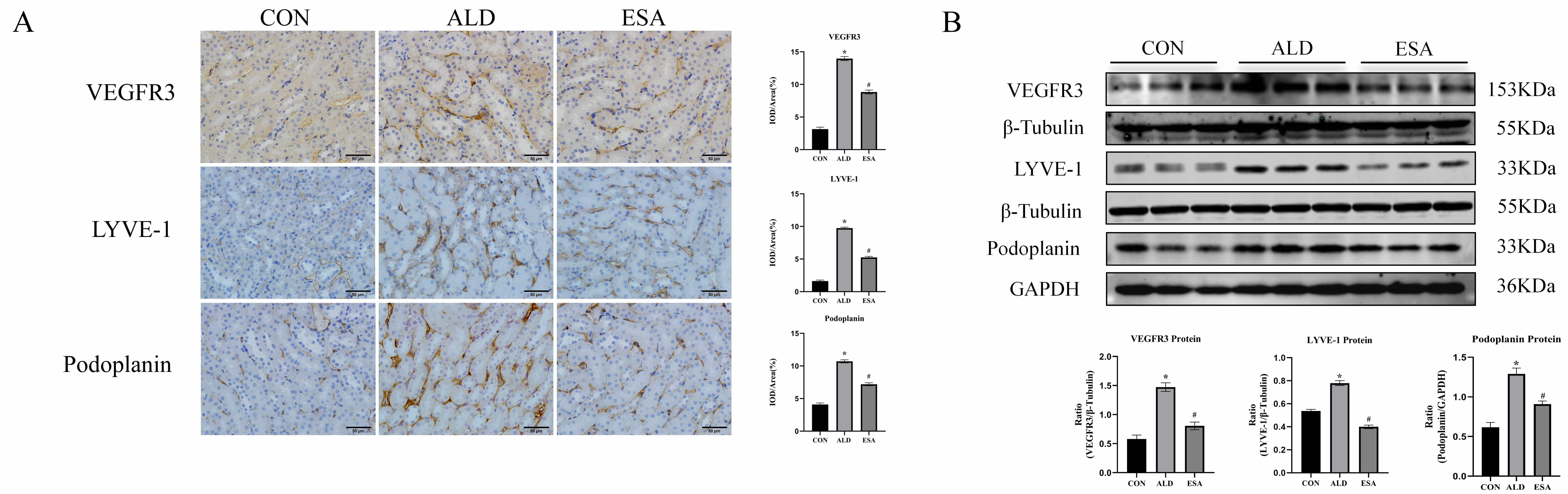

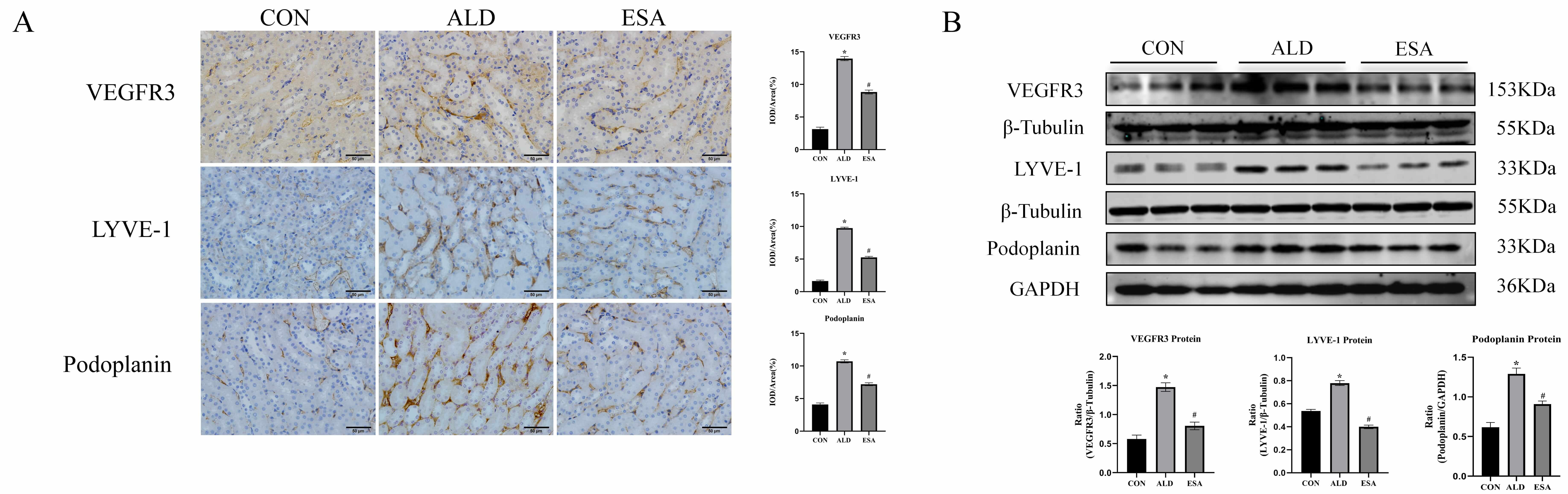

LYVE-1, Podoplanin, and VEGFR3 are markers of lymphatic endothelial cells. Immunohistochemical staining of the kidneys of mice treated with aldosterone at 12 weeks revealed that renal interstitial lymphatic vessel markers were significantly increased and that lymphangiogenesis was significantly reduced after esaxerenone treatment (Fig. 1A). The levels of VEGFR3, LYVE-1, and Podoplanin in renal tissues (determined by Western blot of the whole kidney) reinforced the results of immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 1B). In addition, in the 12-week aldosterone-treated mouse model, H&E staining showed pathologic changes in the kidneys of aldosterone-treated mice, and Masson staining showed that the aldosterone-treated mice had significantly more renal collagen deposition than the control mice (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Aldosterone induces renal lymphangiogenesis in mice.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining was performed with anti-VEGFR3, LYVE-1, and

Podoplanin antibodies to label lymphatic vessels (scale bar = 50 µm). (B)

Western blotting was performed to analyze VEGFR3, LYVE-1, and Podoplanin in renal

tissues. The data are expressed as the mean

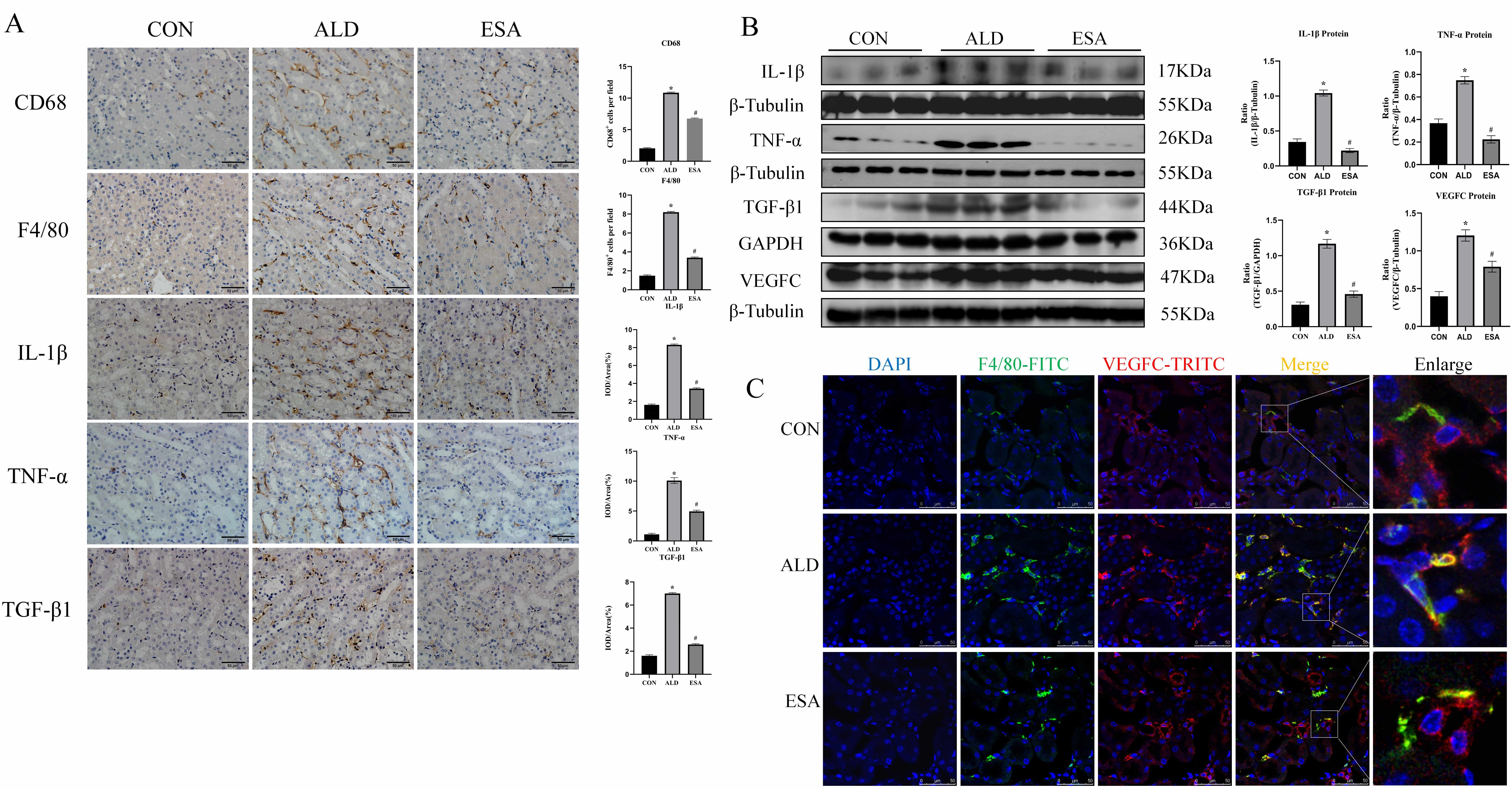

The classical pathway for lymphangiogenesis is the VEGFC/VEGFR3 signaling

pathway, and VEGFC is produced primarily by renal tubular cells and macrophages

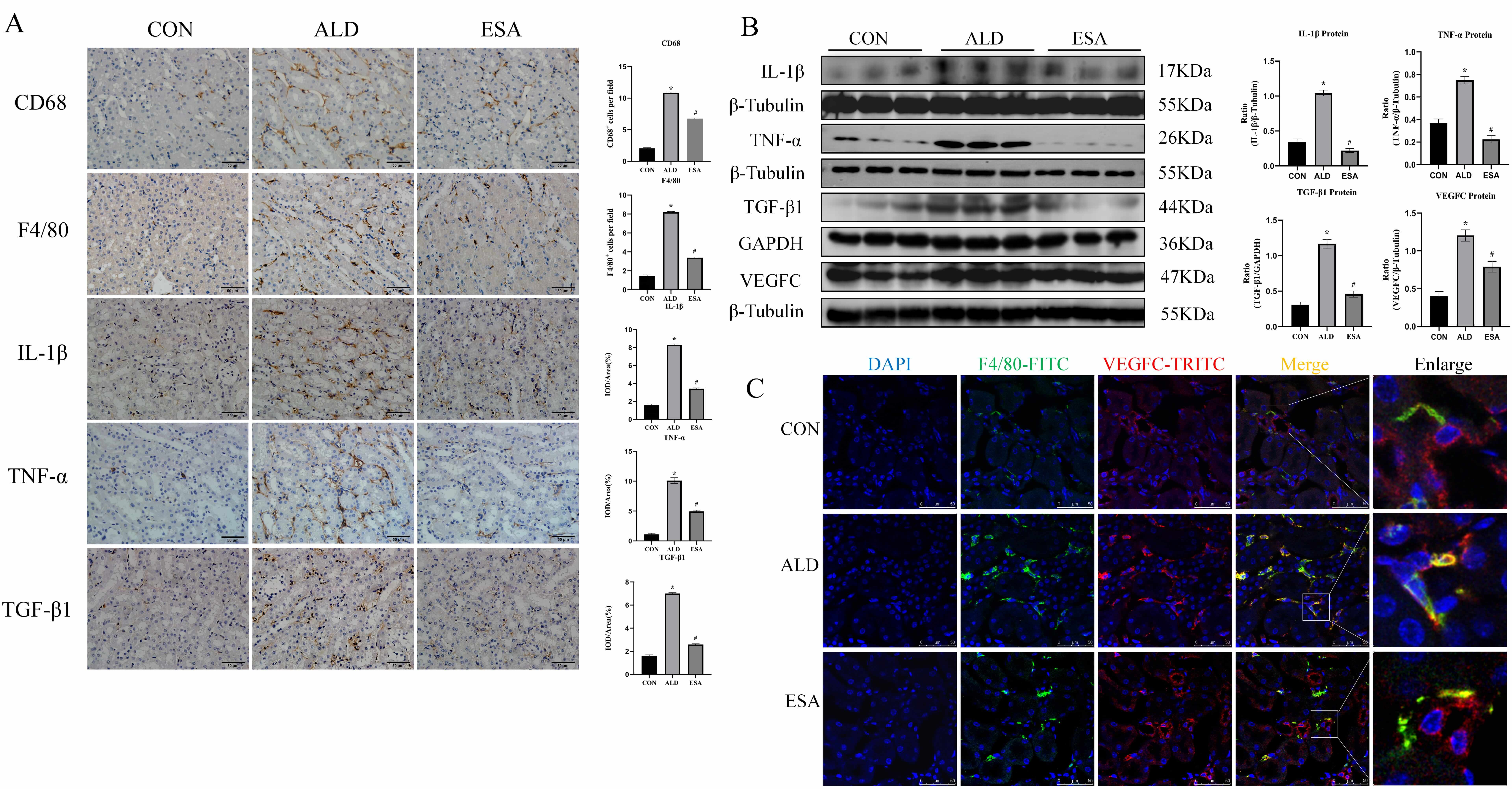

[11, 12]. Aldosterone-treated mice exhibited abundant infiltration of macrophages

labeled with F4/80 or CD68 which was inhibited by esaxerenone (Fig. 2A).

Aldosterone can induce inflammatory macrophage infiltration and the secretion of

inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, which mediate the inflammatory

response and lead to tissue damage [13]. Immunohistochemical staining and western

blot for TNF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Aldosterone stimulates the infiltration of macrophage

and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, VEGFC and TGF-

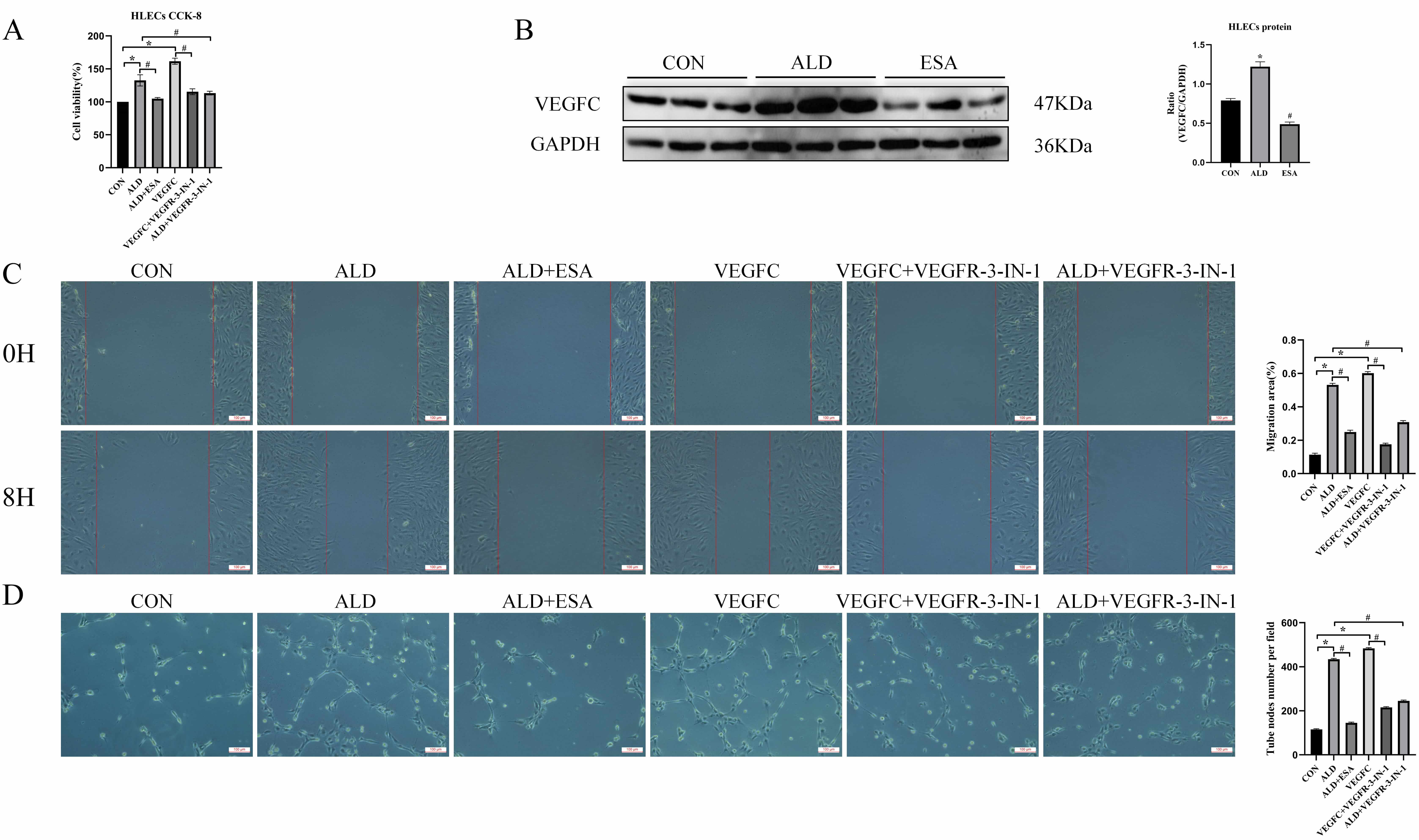

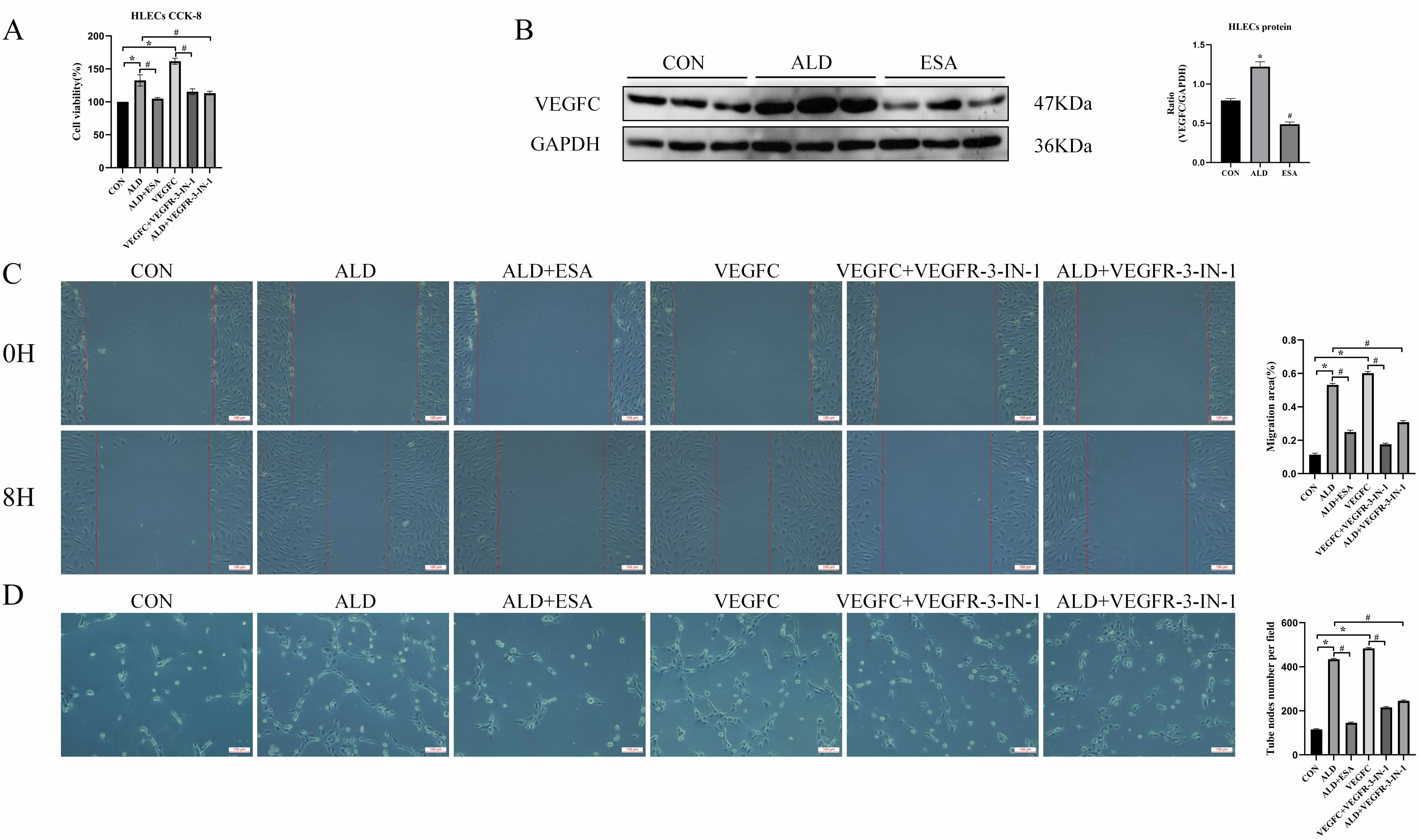

To further investigate the roles of aldosterone and VEGFC in lymphangiogenesis, HLECs were cultured for 24 h with aldosterone and the inhibitor esaxerenone, VEGFC and the inhibitor VEGFR-3-IN-1, or aldosterone+VEGFR-3-IN-1. Cell proliferation was assessed with a CCK8 assay. The proliferation of HLECs in the aldosterone and VEGFC treated groups was markedly greater than that in CON group (Fig. 3A). To further investigate whether aldosterone could promote the secretion of VEGFC by HLECs, we then detected the expression of VEGFC in HLECs stimulated with aldosterone through western blot. The results showed that aldosterone could upregulate the expression of VEGFC in HLECs, and this process was inhibited by esaxerenone (Fig. 3B), further confirming that aldosterone regulated the secretion of VEGFC by HLECs through the activation of MR. In addition, aldosterone and VEGFC directly promoted the migration rate and tube formation capacity of HLECs, whereas the VEGFC inhibitors VEGFR-3-IN-1 and esaxerenone attenuated these effects (Fig. 3C,D). These findings indicated that MR/VEGFC might play a regulatory role in lymphangiogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Aldosterone and VEGFC promote lymphangiogenesis through

mediating the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of HLECs. (A)

VEGFC-induced proliferation of HLECs was determined with a CCK8 assay. (B)

Western blotting was performed to analyze VEGFC expression in HLECs. (C) VEGFC

promotes lymphatic vessel endothelial cell migration (scale bar = 100 µm)

and (D) tube formation (scale bar = 100 µm). The data are expressed as the

mean

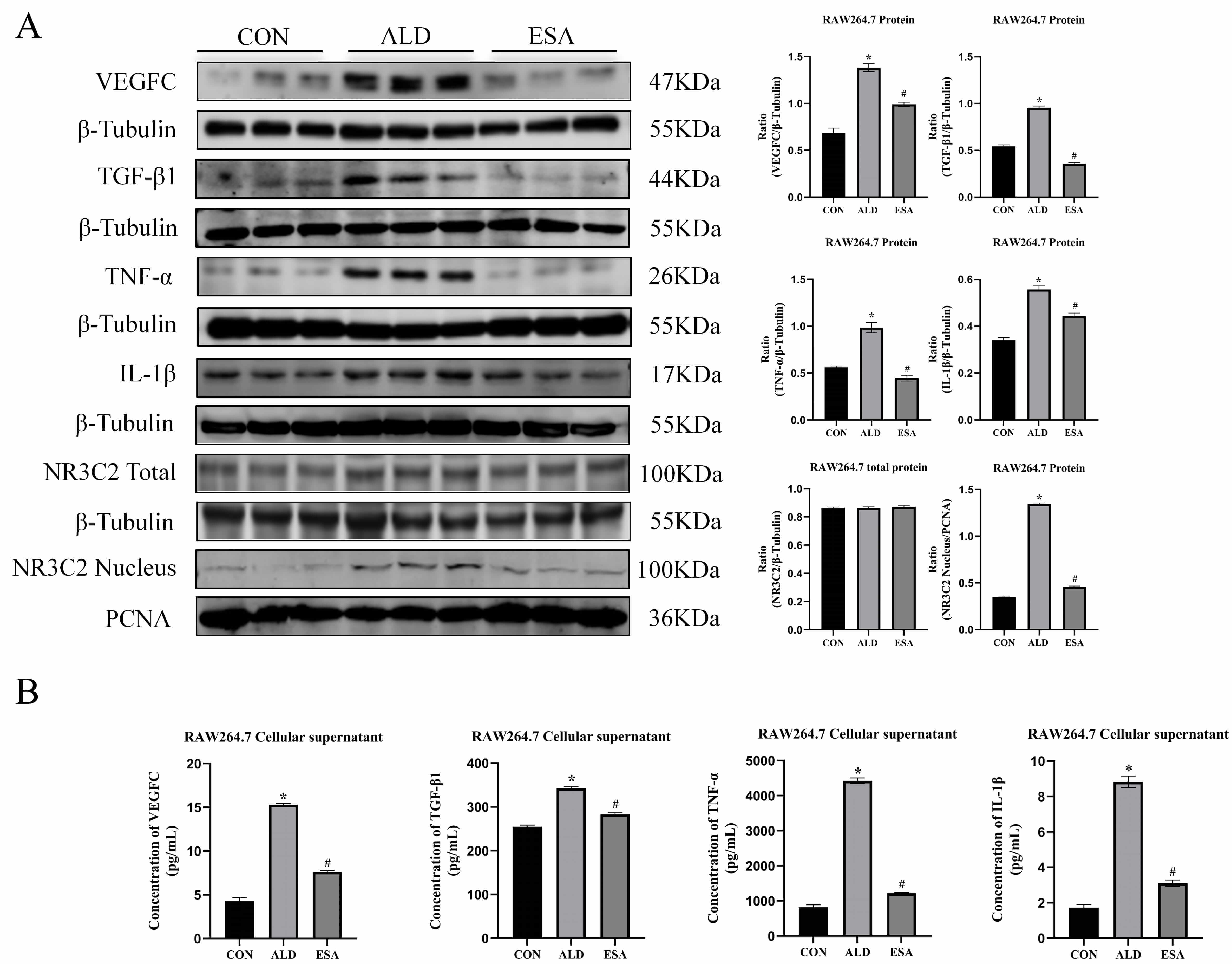

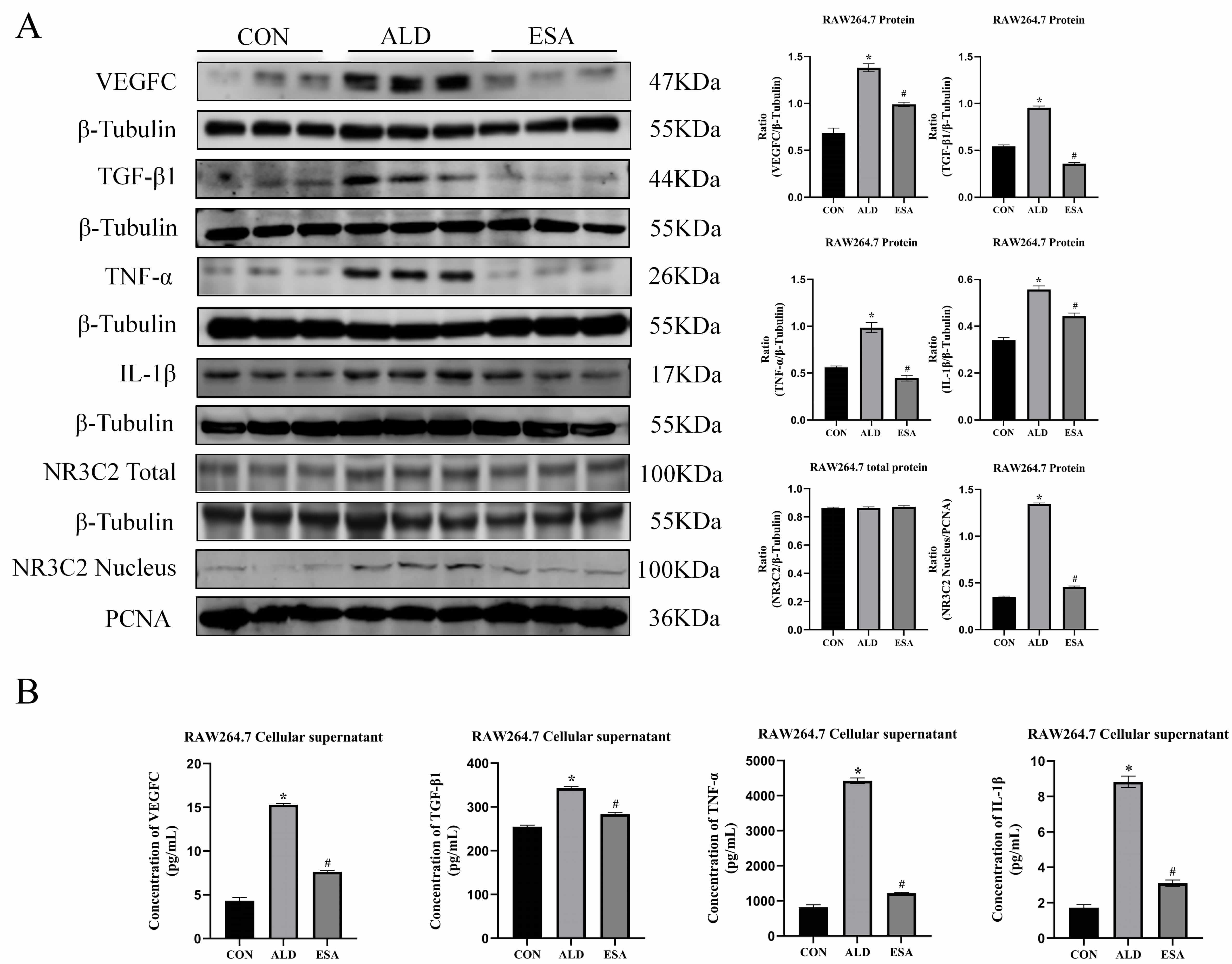

To confirm the in vivo findings, an in vitro study was

performed on aldosterone-treated RAW264.7 cells. Western blots revealed that the

expression of VEGFC, TGF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Aldosterone activates MR and induces RAW264.7 to secrete

inflammatory cytokines, TGF-

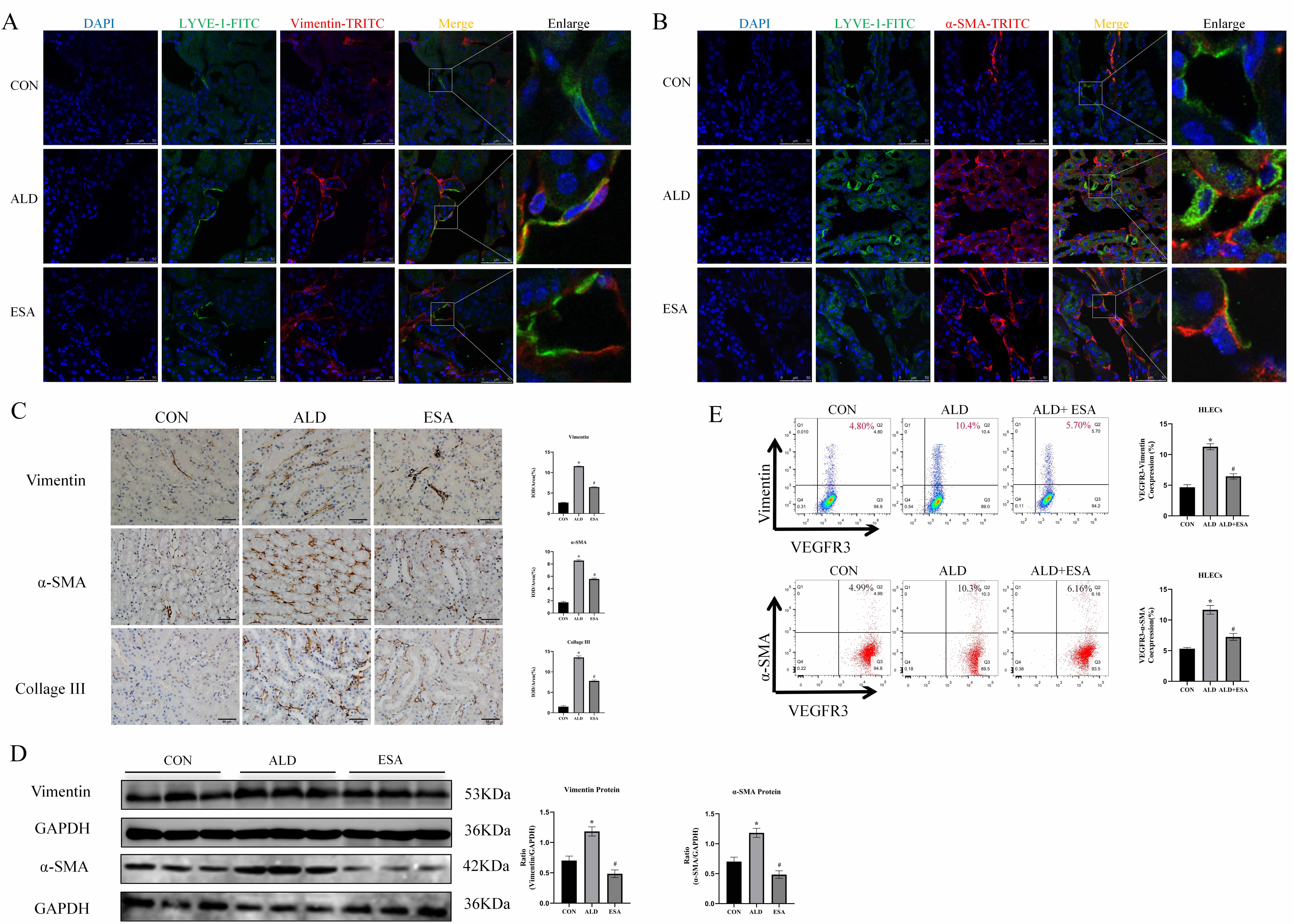

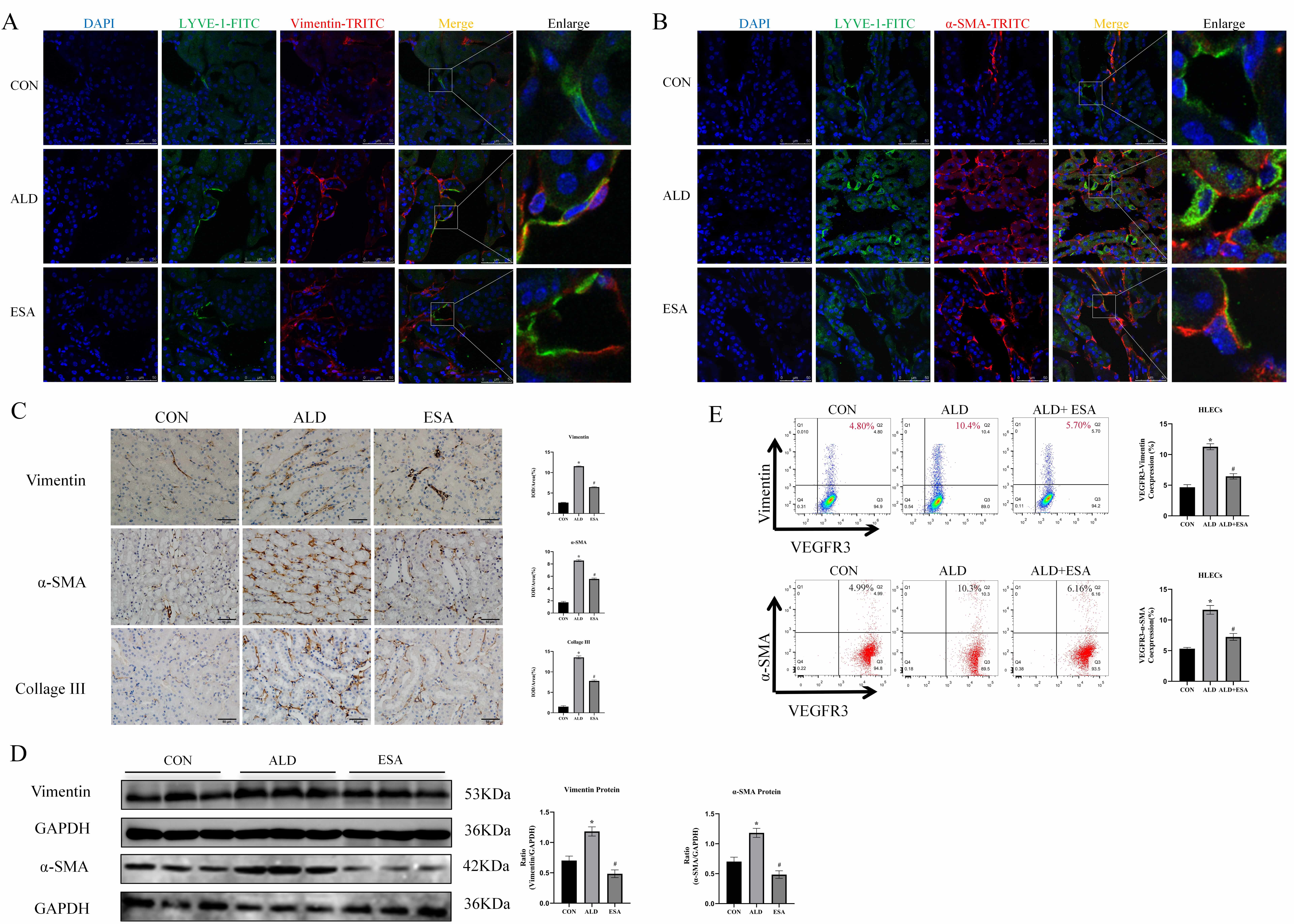

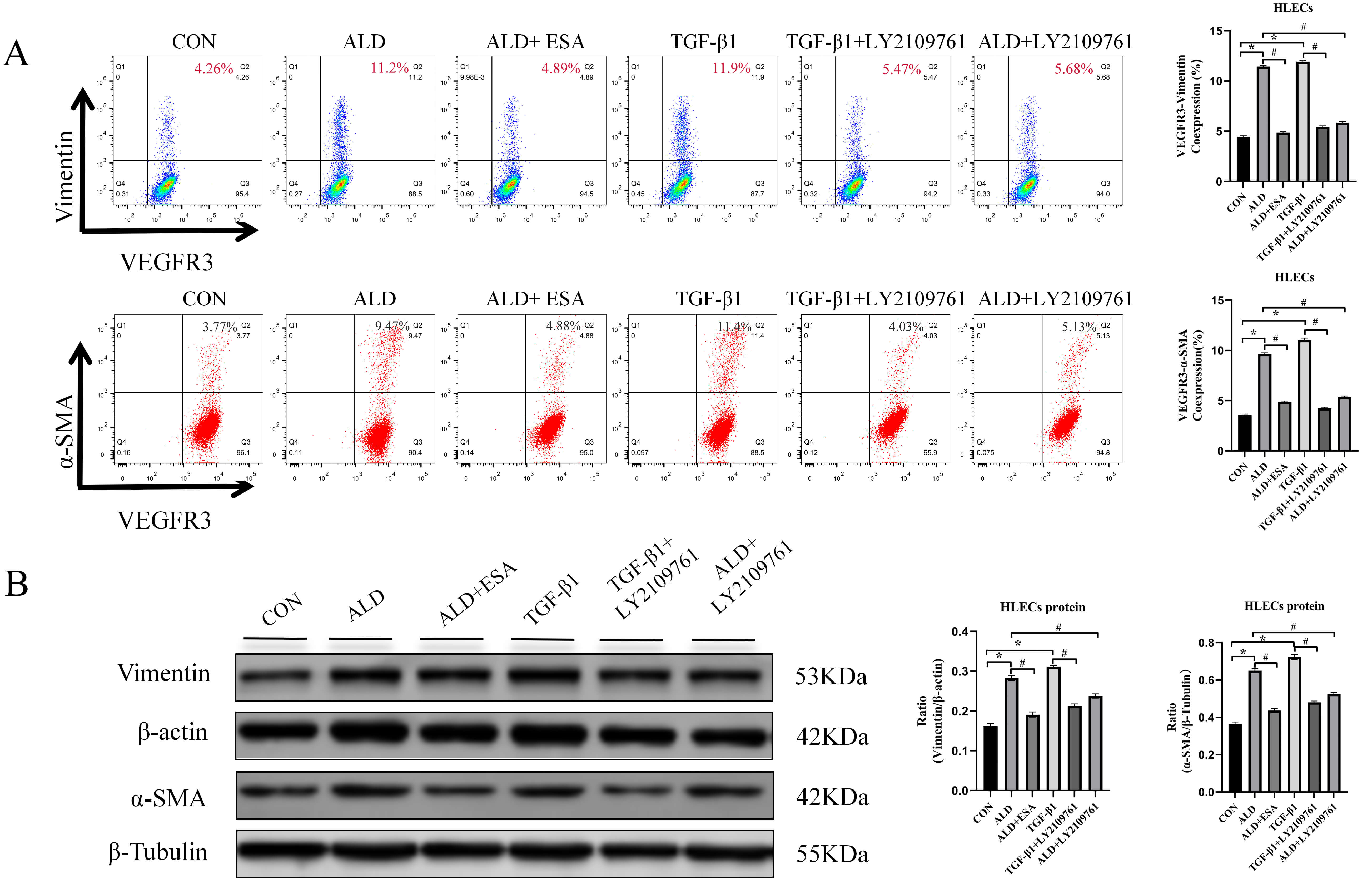

EndMT is a recognized cell transdifferentiation type that has emerged as an

alternative source of tissue myofibroblasts. TGF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Aldosterone induces EndMT in mouse kidneys and HLECs.

(A) Kidney sections were immunofluorescently stained with antibodies against the

lymphatic endothelial cell marker LYVE-1 (green) and the myofibroblast marker

vimentin (red) to identify EndMT (cells expressing both markers indicate EndMT;

nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI) (scale bar = 50 µm). Enlarged images showed a 5× magnification of the areas within the white rectangles in the merged images. (B) Kidney

sections were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with LYVE-1 antibody

(green) and

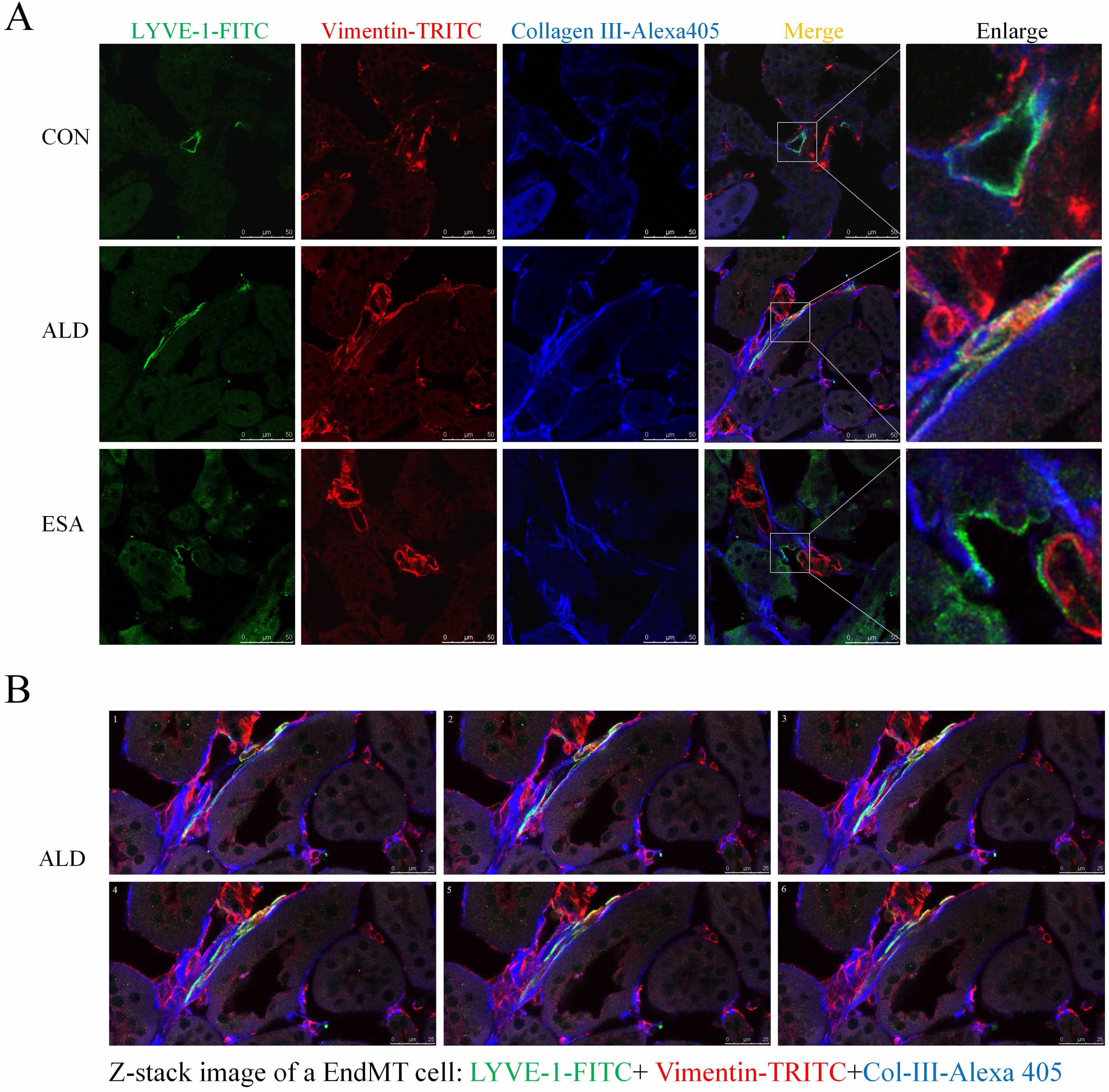

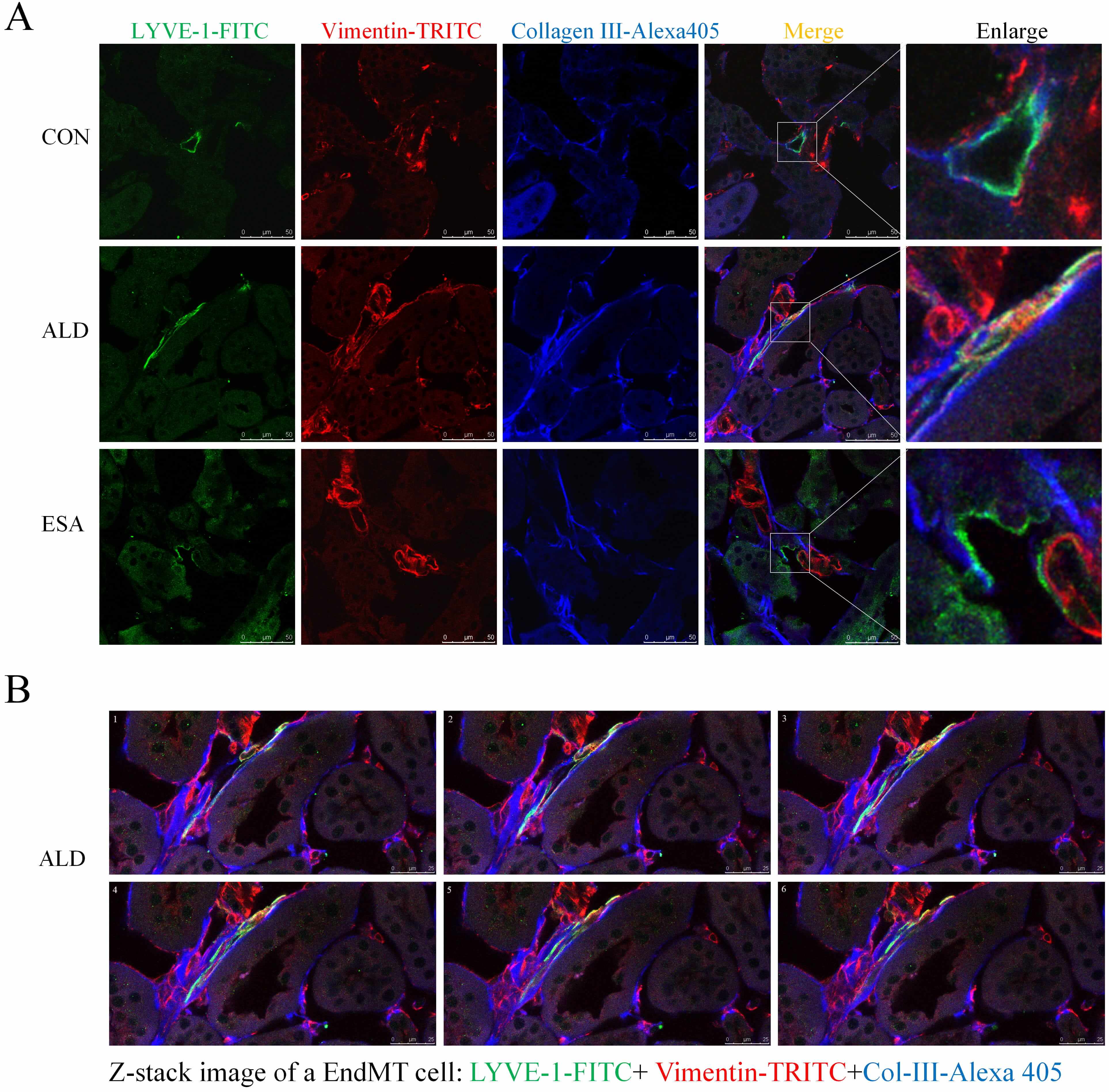

EndMT contributes to fibrosis by driving collagen production, as observed in the analysis of aldosterone-infused mouse kidneys via trichromatic confocal microscopy and Z-stacks, which revealed an increase in the coexpression of LYVE-1+ vimentin+ type III collagen cells. In contrast, the ESA group had significantly fewer coexpressing cells and significantly less fibrosis (Fig. 6A,B; Supplementary Video). These results suggested that collagen secretion by lymphatic endothelial cells undergoing phenotypic transformation was involved in renal fibrosis.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

EndMT produces collagen to participate in renal fibrosis. (A) Three-color confocal microscopy images of cells coexpressing LYVE-1 (green), vimentin (red), and collagen III (blue) (scale bar = 50 µm). Enlarged images showed a 5× magnification of the areas within the white rectangles in the merged images. (B) Z-stack images showing the coexpression of LYVE-1 (green), vimentin (red), and collagen III (blue) in the ALD groups (scale bar = 25 µm) (also shown in the Supplementary Video).

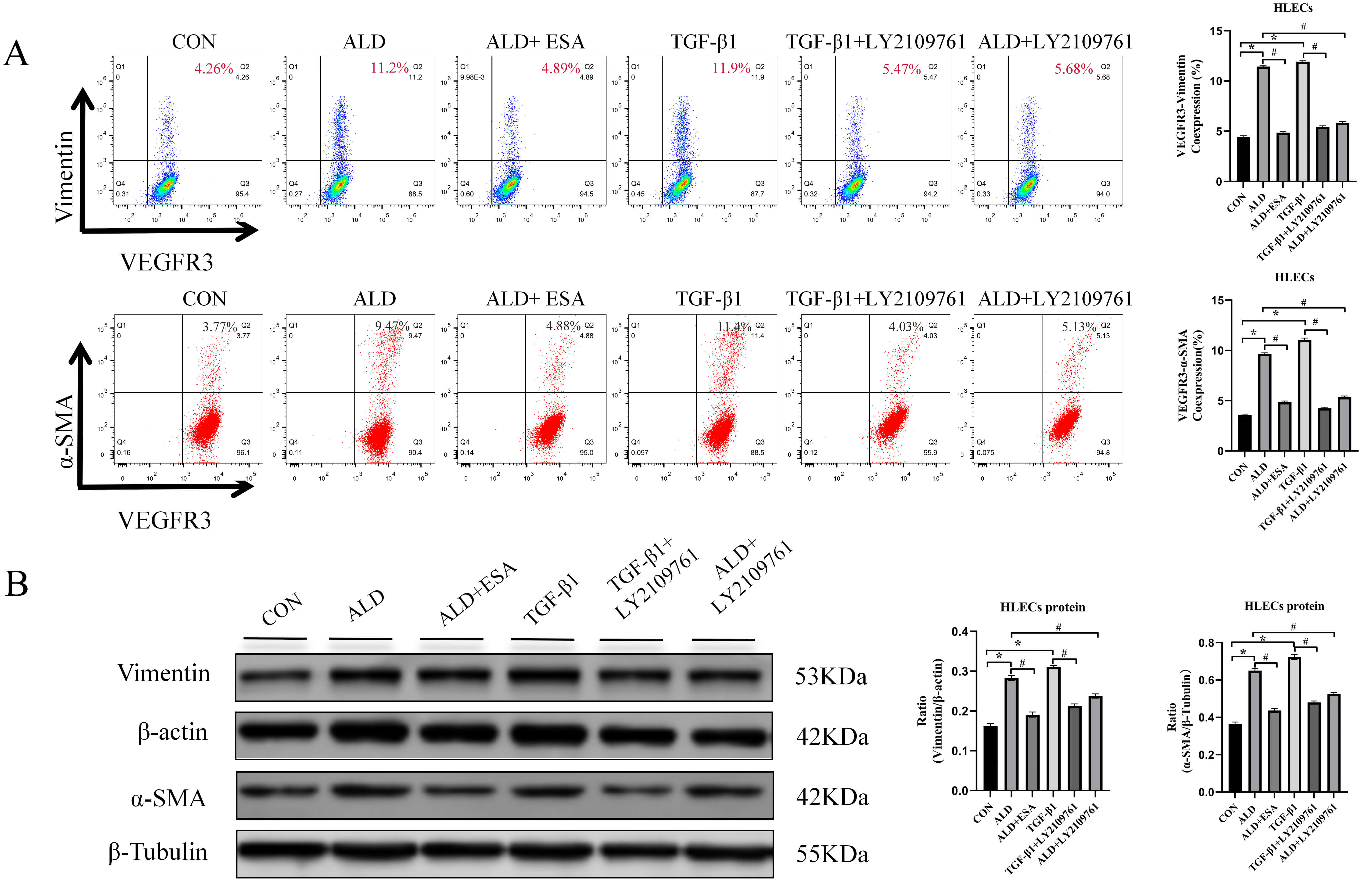

To further investigate the effects of aldosterone and TGF-

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Aldosterone and TGF-

RIF which is characterized by tubulointerstitial fibrosis, is the final manifestation of a wide variety of CKD [16]. RIF is recognized as the final outcome of progressive kidney disease [17]. The impairment in renal function in end-stage renal disease is related to structural changes produced by renal fibrosis and induced by multiple vasoactive substances and cytokines, the most important of which is the renin‒angiotensin‒aldosterone system [18]. The protective effects of ACEIs and ARBs on the kidneys, in addition to correcting blood pressure abnormalities, include the modulation of their downstream mediator aldosterone, and the clinical effects of MRB have confirmed the critical role of MR activation [19]. MRBs can attenuate renal injury via pathways that include the inhibition of cell proliferation [20] and cell phenotypic transformation [8], but few studies have investigated whether MRBs reduce kidney damage by inhibiting inflammatory lymphangiogenesis induced by MR activation. In a long term (180 days) unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) rat model, UUO led to increases in plasma aldosterone levels, lymphangiogenesis, and myofibroblast transformation in the kidney and heart [21]. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that UUO induces an increase in aldosterone, which in turn activates MR, induces EndMT, and promotes fibrosis. Our aldosterone-infused mice model enabled us to investigate the mechanism of aldosterone-induced inflammatory lymphangiogenesis and EndMT in renal fibrosis.

Inflammation, which involves the detection and elimination of harmful pathogens, serves as a key pathogenic mechanism in CKD [22]. While inflammation is a crucial component of the host defense system following tissue injury, persistent or unresolved inflammation contributes significantly to the progression of fibrotic diseases [23, 24]. Furthermore, peripheral solid organ lymphangiogenesis has been implicated in a range of inflammatory conditions, such as transplant rejection, hypertension, extracellular matrix stiffness, myocardial infarction, and tumor metastasis [25, 26, 27, 28]. We hypothesized that there was a connection between fibrotic disease and lymphangiogenesis.

The formation of new lymphatic vessels is observed in acute and chronic inflammation, tumor metastasis, and tissue or organ remodeling. However, new lymphatic vessels are poorly structured and are inadequate for the uptake of water and macromolecules and the return of lymphatic fluid, which leads to localized fluid retention [29]. The lymphatic system can be postnatally stimulated to grow and remodel. Lymphangiogenesis is often observed at sites of tissue injury, interstitial fluid overload [25], hyperglycemia [30], or inflammation and is correlated with the severity of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in many renal disorders [25]. In these settings, the extent to which this process is protective rather than maladaptive is unclear and may depend on the circumstances [31, 32, 33, 34]. However, lymphangiogenesis can protect organs. Renal lymphangiogenesis was found to be beneficial in a UUO model at 14 days [31]. In the early stages of renal transplantation, early restorative lymphangiogenesis reconnects the kidney to the systemic lymphatic system, and the transplant recipient may benefit from the restoration of homeostatic clearance of interstitial fluids and solutes and the clearance of infiltrating cells [35]. Whether lymphangiogenesis is beneficial or harmful to organs depends on the disease and stage. According to the results of the current study, lymphangiogenesis has a better protective effect in the early stage of ischemia and hypoxia, whereas lymphangiogenesis stimulated by chronic inflammation is involved in the formation of organ fibrosis. In this study, we detected renal lymphangiogenesis with fibrosis in aldosterone-treated mice, which warrants further study.

VEGF family members are key mediators of the growth of blood vessels and lymphatics. VEGFR3 was the first lymphospecific growth factor receptor to be identified. VEGFC and VEGFR3 are major components of the apical signaling pathway involved in the development and maintenance of lymphatic vessels [36]. The process of lymphangiogenesis includes proliferation, sprouting, migration, and vascular structure formation. VEGFC induces endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival [37]. In our in vitro experiments, we stimulated HLECs with aldosterone and VEGFC for 24 h, and the results revealed that aldosterone and VEGFC promoted HLEC proliferation. Moreover, aldosterone and VEGFC promoted the migration of cells and the formation of tubes in HLECs, suggesting that aldosterone and VEGFC promoted the generation of lymphatic vessels. VEGFC can be secreted by a variety of renal cells and participate in lymphangiogenesis, such as tubular epithelial cells, fibroblasts and macrophages. In inflammatory injury, macrophages become the predominant source, although tubular epithelial cells also contribute to this process.

Aldosterone is a mineralocorticoid hormone that regulates fluid and electrolyte

homeostasis in the body. Over the past several years, increasing evidence has

demonstrated that aldosterone plays a role in activating both innate and adaptive

immune cells. Specifically, macrophages and T cells respond to aldosterone by

migrating to and accumulating in the kidneys, heart, and vascular system. This

immune cell infiltration has been implicated in the progression of end-organ

damage associated with cardiovascular and metabolic disorders [38]. Aldosterone

binds to MR in local tissues and regulates target organ function. The MR

activation can be verified by detecting the expression of NR3C2 in the nucleus,

specifically through nuclear translocation. MR are expressed in a wide range of

tissues, including smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells,

fibroblasts, macrophages, T cells and dendritic cells [39, 40]. Aldosterone can

induce inflammatory macrophage infiltration and the secretion of inflammatory

cytokines and growth factors, which mediate inflammatory responses leading to

tissue injury [13]. In our study, renal interstitial inflammatory macrophage

infiltration, as well as IL-1

Activated myofibroblasts are critical matrix-secreting cells in RIF and play a

key role in ECM accumulation [42, 43, 44]. Myofibroblasts are a heterogeneous

population that can originate from multiple sources, including epithelial cells

through epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [45, 46], EndMT [47], and

local fibroblast or pericyte proliferation [48]. In the aldosterone-infused mouse

model of lymphatic neovascularization plus fibrosis, we investigated whether

lymphatic endothelial cells transformed into myofibroblasts and led to renal

fibrosis. Immunofluorescence analysis of LYVE-1+ vimentin+/

TGF-

Lymphangiogenesis is related not only to inflammation but also to ischemia and hypoxia. In this study, we focused on lymphangiogenesis under inflammatory conditions and did not address ischemia or hypoxia. The type of macrophages from which VEGFC originates also requires further exploration. Questions for future studies include whether, in addition to promoting increased VEGFC secretion by macrophages, aldosterone also promotes VEGFC secretion by renal tubular epithelial cells and whether the macrophages promoted by aldosterone are recruited or proliferating.

This study has several limitations. First, although the main sources of VEGFC were renal tubular cells and macrophages especially those in an inflammatory injury environment, the specific types of macrophages from which VEGFC is derived have not been explored in depth, and the diversity of the sources and functions of macrophages has not been fully studied. Second, in addition to promoting the secretion of VEGFC by macrophages, aldosterone can also promote the secretion of VEGFC by renal tubular epithelial cells and other cells. The role of aldosterone in lymphangiogenesis requires more precise verification. Third, the inclusion of a separate esaxerenone treatment group would have strengthened the evidence for its direct pharmacological effects on macrophage infiltration and VEGFC inhibition. Additionally, direct phenotypic and functional profiling of isolated renal macrophages, which would elucidate their origin, polarization state, and VEGFC secretion, was not performed. Despite these limitations, the current findings are instructive and provide a solid foundation for subsequent research endeavors.

In vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrated that ALD

increased macrophage infiltration and activated MR in macrophages, induced the

secretion of the inflammatory cytokines, VEGFC and TGF-

ALD, aldosterone;

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conceptualization, QYX, PPQ and TS; Methodology, LLF and ZQL; Validation, YC, XMG, JYC, FY and YZX; Formal Analysis, LLF and ZQL; Investigation, ZQL; Resources, QYX and YZX; Data Curation, LLF; Writing — Original Draft Preparation, LLF; Writing — Review & Editing, QYX, PPQ and TS; Visualization, PPQ; Supervision, QYX and TS; Project Administration, PPQ; Funding Acquisition, QYX, FY and YZX. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei University of Chinese Medicine (Ethic Approval Number: No. DWLL2021063). All animal care and experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Hebei University of Chinese Medicine and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the same institution. All efforts were made to minimize animal distress and ensure ethical treatment.

Esaxerenone was provided by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation Project of China, grant number: No. 82174317; No. 82305121; No. 82205006, and the Natural Science Fund of Hebei Province, grant number: No: H2023423042.

All authors declare no conflicts of interest. Despite Tatsuo Shimosawa received lecture honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Esaxerenone was provided by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd, the judgments in data interpretation and writing were not influenced by this relationship.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL45591.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.