1 Department of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Medical Oncology, Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute, 110042 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

2 Central Laboratory, Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Cancer Hospital of Dalian University of Technology, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute, 110042 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

3 Liaoning Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Institute, 110847 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

4 College of Acupuncture and Massage, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 110847 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

5 Department of Neurosurgery, Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Cancer Hospital of Dalian University of Technology, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute, 110042 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Abstract

The intestinal microbiota, present in vast numbers within the human body, plays a pivotal role, with its composition and abundance varying significantly across individuals. This gut microbiota not only contributes to normal physiological development but also impacts the initiation, progression, resolution, and prognosis of various diseases. Recent studies have increasingly illuminated the connection between intestinal microbiota and pain, with a particular focus on the relationship between gut microbiota and neuropathic pain (NP). NP, an acute and chronic pain disorder arising from sensory nervous system injury, encompasses both peripheral and central neuropathic pain. Evidence suggests that intestinal microbiota influences NP occurrence and may modulate its severity. This review synthesizes current research findings on the microbiota-NP relationship, aiming to establish a theoretical foundation for future clinical investigations.

Keywords

- microbiota

- gastrointestinal microbiome

- neuropathic pain

- gut-brain axis

- chronic pain

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors a vast array of intestinal microbiota, comprising bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, with the richest diversity localized here [1, 2]. The establishment of this complex microbial ecosystem is a gradual process beginning in infancy [3, 4], playing a pivotal role in growth, development, immune regulation, and autoimmunity [5]. Various factors, including lifestyle, ethnicity, geography, and gender, significantly influence the composition and quantity of intestinal microbiota.

Neuropathic pain (NP), a chronic disorder resulting from sensory nervous system injury, includes both peripherally induced neuropathic pain (pNP) and central neuropathic pain [6]. Peripheral neuropathic pain often stems from peripheral neuropathies, such as diabetic peripheral neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, and postherpetic neuralgia [7]. The incomplete understanding of NP pathogenesis has led to a lack of effective treatments [8], making NP a condition that not only causes severe patient distress but also imposes substantial economic burdens. Current treatments predominantly involve opioids, which frequently fail to provide sufficient pain relief [9, 10, 11], underscoring the urgent need for alternative therapeutic approaches.

A bidirectional relationship exists between the gut and brain, with emerging

studies highlighting that gut flora influences stress responses via the

brain-gut axis [12]. Staphylococcus aureus-secreted

A literature search was conducted in PubMed, the Web of Science Core Collection, and CNKI up to 2025 using the search strategy: (“gut microbiota” OR “intestinal microbiome”) AND (“neuropathic pain” OR “neuralgia”). Additional references were identified by manually tracking citations from recent reviews and highly cited papers. No restrictions were imposed on publication date, species, or study design; priority was given to high-quality original studies and authoritative reviews published within the last five years.

We included original investigations, systematic or narrative reviews, and clinical guidelines that were directly relevant to the topic, giving preference to peer-reviewed articles published in core English- or Chinese-language journals. Studies focusing solely on nociceptive pain without neuropathic components or those only tangentially related to the topic were excluded.

Intestinal microbiota is integral to food digestion, regulation of intestinal endocrine functions, immune response activation, and neurotransmitter modulation [16]. Despite variations in composition and quantity across individuals, these microorganisms consistently fall into major categories: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria [17], with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes representing two primary bacterial phyla in a healthy human microbiome [18]. Beyond the microbiota’s direct impact on host functions, its metabolites and byproducts also significantly affect physiological processes.

In the gut, dietary fiber is fermented by these microorganisms into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which serve as a critical energy source for gut microbiota, modulate host physiological functions and immune responses [19], and act as key mediators of host-microbiota interactions [20]. Additional byproducts of the gut flora also exert various influences on host physiology [21] (Table 1, Ref. [21, 22, 23, 24]).

| Metabolite | Related bacteria | Functionality | Reference |

| 1. Short-chain fatty acids: acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, valeric acid, etc. | Clostridia of the phylum Thick-walled Bacteria | Enhance glucose homeostasis in the intestine, liver, and systemic circulation, regulate appetite, and modulate immune function and inflammatory responses | [22] |

| 2. Choline metabolites: methylamine, dimethylamine, trimethylamine, etc. | Bifidobacterium spp. | Regulation of lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis is essential in managing Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and diet-induced obesity | [21] |

| 3. Indole derivatives: indoleacetic acid, indoleacetylglycine, indole sulfuric acid, etc. | Escherichia coli, Clostridium spp. | Contribute to the maintenance of intestinal mucosal homeostasis and protection against stress-induced gastrointestinal injury, with potential to inhibit macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses | [23] |

| 4. Lipids: lipopolysaccharide, peptidoglycan, cholesterol, lecithin, etc. | Bifidobacterium spp., Klebsiella spp., Citrobacter spp., Clostridium spp., etc. | Affect intestinal permeability, with lipopolysaccharides inducing chronic systemic inflammation; cholesterol serves as a precursor for sterol and bile acid synthesis | [21] |

| 5. Vitamins: Vitamin K, Vitamin B12, Folic Acid, Vitamin B6, etc. | Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp. etc. | Enhance immune function and supply essential endogenous vitamins | [24] |

The intestinal microbiota, residing within the intestinal tract, operates within an extensive network interlinked with various bodily systems. The connection between the gut and central nervous system, often referred to as the “gut-brain” axis, represents a complex communication pathway. The “microbe-gut-brain” axis specifically involves microbial metabolites that influence neurodevelopment by interacting with the vagus nerve and extending through pathways [25] that include the enteric nervous system (ENS), the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and neuroimmune signaling pathways [26]. Neurotransmitters produced in the gut can impact the brain indirectly via the ENS [27, 28]. Additionally, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) from the hypothalamus prompts the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then stimulates cortisol release from the adrenal glands, initiating interactions with various intestinal targets [29].

Bacteria like Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus produce neurotransmitters and their precursors—such as acetylcholine, serotonin, and GABA—that may influence brain neurotransmitter levels [30]. Certain neurotransmitters also interact with gut microbiota; for instance, serotonin, or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), performs diverse functions in both the brain and gut and impacts the gut flora, particularly along the microbe-gut-brain axis [31].

Hippocampal neurogenesis, which is influenced by cognitive behaviors within the hippocampus [32], is a central neural mechanism impacted by common cancer treatments, including chemotherapy [33]. Studies indicate that gut microbiota is closely associated with adult neurogenesis and hippocampal plasticity [34]. Research on germ-free mice has offered key insights into the gut microbiota’s role in Central Nervous System (CNS) regulation, with findings of increased hippocampal volume, enhanced adult hippocampal neurogenesis, and altered hippocampal mRNA expression in germ-free conditions [34, 35]. Liu et al. [36] demonstrated that early intestinal dysbiosis impairs hippocampal neurogenesis, which can be restored by re-establishing a normal microbial population.

The influence of microbiota on hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function is closely linked to its effects on hippocampal Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) levels [37] and highlights the bidirectional impact between the nervous system and gut flora. Prior studies have shown that the probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 (Escherichia colistrain Nissle, [EcN]) produces GABA-associated analgesic lipopeptides capable of crossing the intestinal epithelial barrier to inhibit injury receptor activation and downstream responses [38]. Additionally, dysbiosis has been observed in the gut following spinal cord injury [39]. Mayer et al. [40] proposed a complex gut-brain connection, suggesting that gut microbiota might influence pain processing and perception, establishing a theoretical basis for investigating the impact of the microbial gut-brain axis on disease. The gut microbiota contributes to pain onset and progression largely through interactions with spinal dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells and gut nerve endings [41]. Substantial evidence shows that dysbiosis of certain anti-inflammatory gut microbes can, paradoxically, trigger neuro-inflammation [42, 43, 44].

Neuroglial cells, encompassing microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, are extensively distributed within the central and peripheral nervous systems and maintain a significant relationship with gut flora. Microglia, the primary innate immune cells of the CNS, are particularly responsive to gut microbiota [45]. Under homeostatic conditions, microglia contribute to various physiological functions, including nervous system development [46] and the preservation of blood-brain barrier integrity [47]. The gut microbiota influences microglial maturation and activation via the release of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [48, 49], which can also mediate chronic pain onset by polarizing microglia in the hippocampus and spinal cord [50]. Chronic activation of microglia results in sustained low-grade neuroinflammation, which negatively impacts neurons and synapses, contributing to neurodegeneration [51]. Animal models indicate that gut flora alterations can modulate microglial function and activation, promoting the onset of neurodegenerative diseases. These findings underscore the reciprocal interaction between the gut and brain, with each influencing the physio pathological functions of the other, thus co-regulating systemic activity.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines NP as “pain caused by injury or disease of the somatosensory nervous system” [52], categorizing it into peripheral and central neuropathic pain [6] (Table 2, Ref. [50, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57]). NP is typically chronic, frequently manifesting as recurrent and persistent discomfort.

| Typology | Possible mechanisms | References |

| 1. Post-chemotherapy peripheral neuropathic pain (CINP) | Includes microtubule disruption, oxidative stress with mitochondrial damage, ion channel dysregulation, myelin degeneration, DNA damage, immune activation, and neuroinflammation. | [50] |

| 2. Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP) | Characterized by dysregulated ion channel expression in burning pain, with increased mutations affecting Nav1.7 ion channel subunit function, alongside vascular insufficiency. | [53] |

| 3. Inflammatory postherpetic pain (PHN) | Varicella zoster virus infection induces neuroinflammation, damages the dorsal horn, and disrupts inhibitory pathways, initially reducing pain but subsequently leading to central sensitization and ectopic firing in affected peripheral neurons. This process involves upregulation of pain receptors, including increased expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels, and a loss of dorsal horn |

[54] |

| 4. Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) | Potential abnormalities in cation channel expression or function, with mutations in ionophilic channels, affecting genes for transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, voltage-gated potassium channels, and voltage-gated calcium channels. | [55] |

| 5. Migraineur (Migraine) | A neurogenic inflammatory response characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory neuropeptides, including substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and additional pro-inflammatory neuropeptides within the downstream pathways of the nociceptive system barrier. | [56, 57] |

| 6. Cancer Pain | Osteoclasts and multiple myeloma collaboratively create an acidic bone microenvironment, activating sensory neuron ASIC3 receptors and inducing bone cancer pain. This process includes the sprouting of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-positive nerve fibers within the bone, correlating with increased intracellular CGRP levels in sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG). Notably, intrathecal administration of a CGRP antagonist alleviated pain in the affected limbs of rats experiencing bone cancer pain. | [50] |

Peripheral nerve injuries can arise through mechanical, chemical, or infectious pathways, often resulting in spontaneous pain typified by sensations such as shooting, stabbing, or burning [58]. These injuries commonly induce an overexcitation of peripheral nerve fibers, stemming from altered ion channel functions, which accelerates channel activation and heightens current density [59].

Afferent blockage, ion-channel failure, neuro-immune interaction, and glial

activation interact intricately to produce central neuropathic pain [60, 61].

Aberrant neuronal excitability: neurons within central pain-processing

pathways—such as those in the spinal dorsal horn and thalamus—develop

spontaneous or ectopic discharges after injury, leading to persistent pain or

hyperalgesia [62]. While spinal and brain-stem microglia quickly multiply and

take on a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, secreting tumor necrosis factor-alpha

(TNF-

Gut flora is implicated in various forms of peripheral neuropathic pain, with specific microbial compositions linked to distinct diseases (Table 3, Ref. [58, 59, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76]).

| Types of pain | Flora involved | References |

| 1. Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain (CINP) | Significant reductions were observed in bacteria such as Clostridium anomalum, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Clostridium groups IV and XIVa. | [67] |

| 2. Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP) | An increase was noted in Ehrlichia spp. and Vibrio vulnificus spp., while Prevotella spp. and E. faecalis showed a decrease. | [68] |

| 3. Inflammatory postherpetic nerve pain (PHN) | At the phylum level, the abundance of Firmicutes was reduced, while Proteobacteria showed increased abundance. Notable decreases were observed in Fusobacterium groups, Butyricicoccus, Tyzzerella, Dorea, Parasutterella, Romboutsia, Megamonas, and Agathobacter. | [69, 70] |

| 4. Traumatic neuropathic pain (TINP) | Pretreatment with Lactobacillus acidophilus or Clostridium butyricum mitigates the neurological effects associated with traumatic brain injury. | [71] |

| 5. Chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve (CCI) | An increased abundance of the phylum Anabaena, along with reduced abundance of the phylum Firmicutes, and decreased levels of Lactobacillus and unclassified Clostridium species were observed. | [72, 73] |

| 6. Migraine | Significant increases were observed in the abundance of Megasphaera, Dense Spirochete, Fretibacterium, SR1 incertae sedis, while notable decreases occurred at the genus level for Micrococcus, Clostridium perfringens, and Rhodococcus. | [74, 75, 76] |

| 7. Cancer Pain | Selective depletion of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium was observed in morphine-resistant mice, with an increase in Flavobacterium, Enterococcus, Clostridium (including Clostridium difficile), Serratia, Firmicutes, and Ruminococcus in mice administered intraperitoneal morphine. | [58, 59] |

Chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain (CINP) is a prevalent adverse effect of chemotherapeutic agents, with incidence rates reported between 19% and over 85% [77], particularly high with platinum-based agents (70–100%) and paclitaxel (11–87%) [78]. Clinically, CINP significantly impacts patient prognosis, reduces the effectiveness of chemotherapy, and severely diminishes the quality of life for patients and cancer survivors [79].

The pathogenesis of CINP is multifaceted, involving microtubule disruption, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, altered ion channel activity, myelin sheath impairment, DNA damage, immune processes, and neuroinflammation [80]. The complex etiology primarily involves cellular disorganization, neurotransmitter activation, and ion channel alterations. Specific mechanisms include chemotherapeutic drug uptake mediated by transporters, mitochondrial damage-induced oxidative stress, disrupted microtubule function and subsequent axonal transport loss, damage to DRG sensory neurons, aberrant pain fiber discharge, increased cellular inflammatory factors, altered ion channels, and growth factor inhibition [52].

For paclitaxel, microtubule disruption is a central mechanism [81], where microtubule aggregation and bundling lead to cell shape and stability alterations and impair axonal transport of synaptic vesicles, critical for transporting lipids, proteins, and ion channels [82, 83]. Paclitaxel also disrupts ion channels and activates astrocytes [79]. Research has identified key pain signaling components, including the transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 (TRPV1) and ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), in DRG neurons [84], with TRPA1 antagonists shown to alleviate paclitaxel-induced inflammation, cold hyperalgesia, and nociceptive hypersensitivity [85].

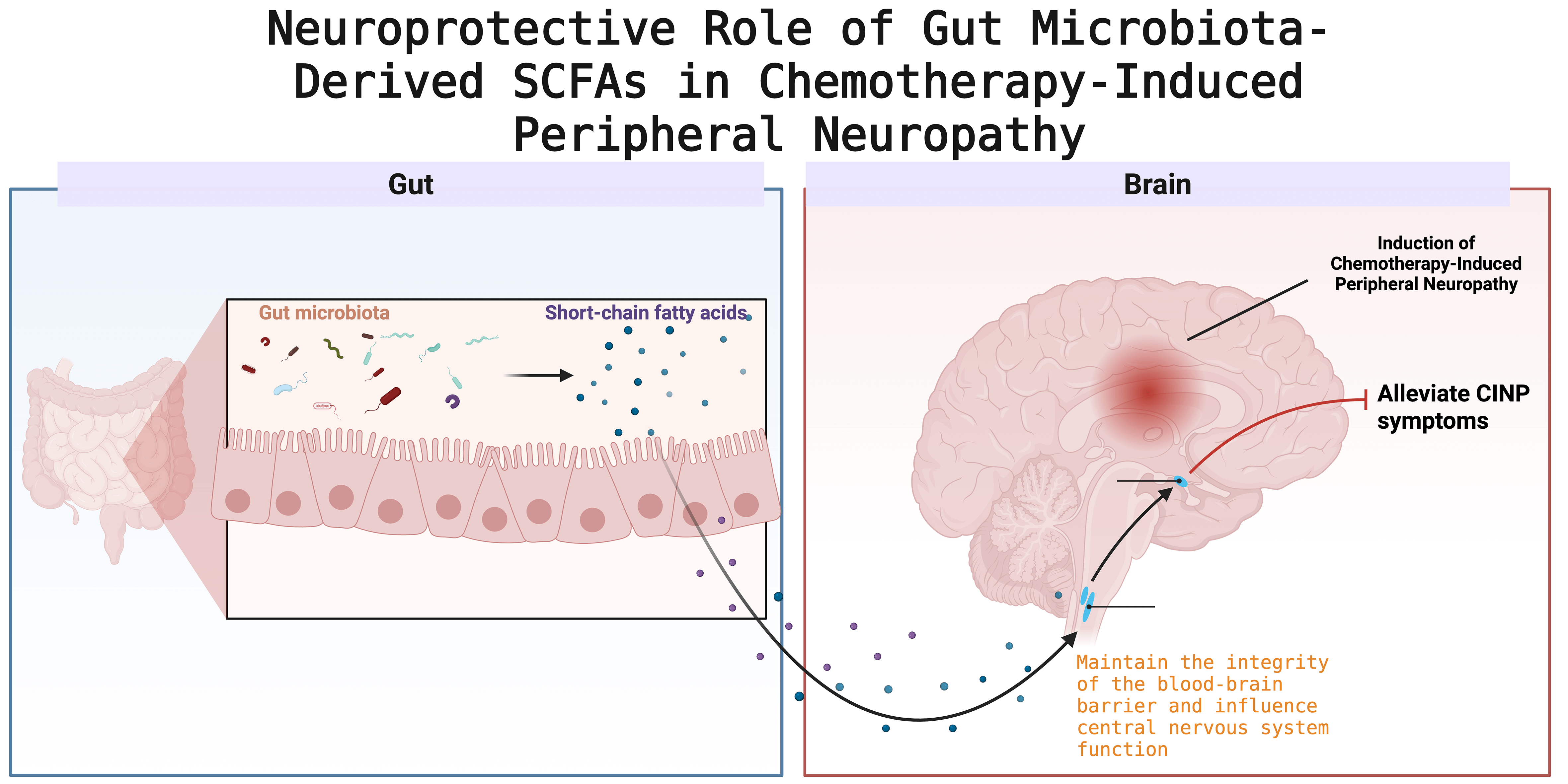

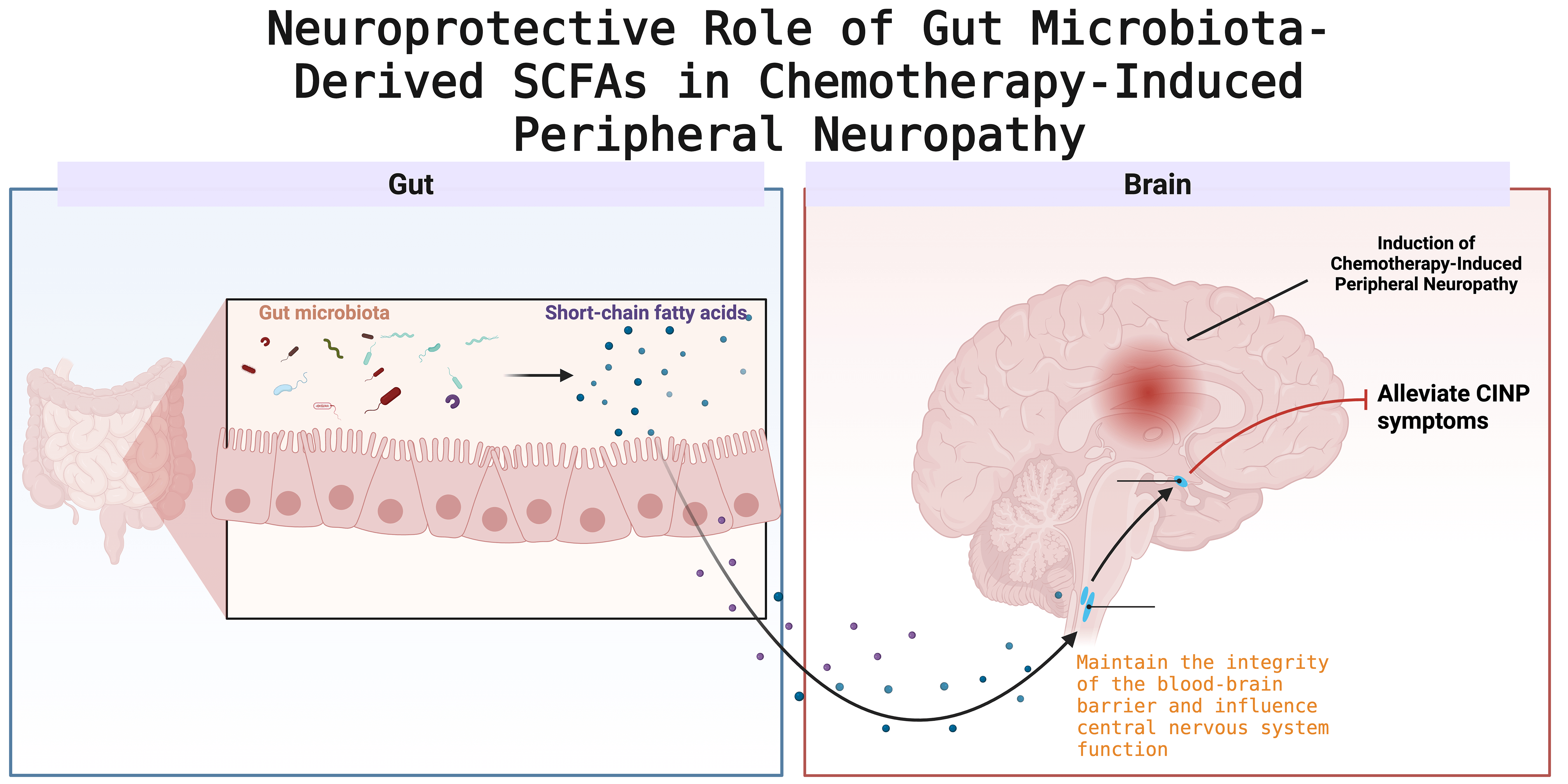

Vincristine-induced CINP is characterized by distal motor degeneration and is associated with pain, primarily due to elevated mitochondrial calcium levels and synaptic remodeling in the spinal cord’s dorsal horn [86] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the neuroprotective mechanism mediated by gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CINP). Created with BioRender (http://www.biorender.com/).

The gut microbiota is linked not only to chemotherapy efficacy but also to neurological toxicity, including the onset of PN [87, 88, 89]. Nociceptors can directly detect bacterial and fungal components, triggering pain and modulating inflammation [90, 91]. The enteric nervous system (ENS) plays a critical role in the complex pathophysiology underlying gastrointestinal dysfunction following chemotherapy [92, 93]. Studies have shown that intestinal microbiota contributes to neuropathic pain development post-chemotherapy [94]. Chemotherapy-induced damage to the intestinal epithelial barrier facilitates microbial translocation and the release of harmful endogenous substances, which activate pathogen-associated molecular patterns and pattern-recognition receptors in host antigen-presenting cells, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators central to the pathogenesis of CINP [67]. Patients undergoing various chemotherapeutic regimens experience significant disturbances in intestinal microbiota, with notable reductions in bacteria such as Anaplasma phylum, Bifidobacterium, and Clostridium groups IV and XIVa [95]. Additionally, the gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in immune system regulation [96], with microbiota depletion shown to prevent the onset and persistence of oxaliplatin-induced mechanical pain abnormalities [97]. This evidence underscores the dual role of gut flora, acting both as a contributor to pain onset and as a potential modulator to alleviate it.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP) is a prevalent complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a multifaceted syndrome impacting the sensory, somatic, and autonomic nervous systems [98, 99]. It affects peripheral nerves, leading to pain, numbness, and sensory loss in the extremities [100]. Effective treatments for DPNP are limited to glycemic control and pain management [101]. DPNP affects nearly 50% of diabetic patients and contributes to numerous complications, including impaired intestinal transit [102].

Insulin resistance is central to T2DM pathogenesis [103] and closely related to DPNP due to the deleterious effects of chronic hyperglycemia on nerve cells and their microenvironment, causing inflammation, oxidative stress, and abnormal nerve conduction [104]. Vrieze et al. [105] demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in individuals with metabolic syndrome significantly improved insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, patients with T2DM exhibit a markedly lower abundance of Bacteroides thicketi, Fusobacterium rectum, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Clostridium difficile compared to healthy individuals [106]. Yang et al. [107] found that FMT from patients with DPNP into db/db mice resulted in more severe peripheral neuropathy compared to FMT from patients with DM or normoglycemic individuals. This suggests that gut microbiota dysbiosis accelerates DPNP progression and that modulating the gut microbiota via FMT can reduce neurological symptoms and improve neurological function in patients with DPNP.

Gut flora metabolites, such as SCFAs, also impact DPNP. Bonomo et al.

[108] demonstrated that butyrate alleviated neuropathic pain in rodent models of

nerve injury by modulating neuronal, macrophage, and Schwann cell expression

within the peripheral nervous system. Additionally, a strong correlation was

found between the presence of the genus Paramyxomycetes, C-reactive protein, and

levels of bovine deoxycholic acid [109]. In a preclinical study,

antibiotic-induced modulation of gut flora improved diabetes-related neuropathic

pain in mice, supporting the hypothesis that DPNP symptoms improve when harmful

bacteria are removed or replaced with beneficial strains [97]. Another

preclinical study showed that FMT in mice on a high-fat diet mitigated mechanical

pain sensitivity, thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity, and nerve fiber damage

associated with insulin resistance [81]. Inflammatory responses are likely

mediators of peripheral nervous system damage leading to DPNP, with studies

showing significantly elevated serum levels of inflammatory markers, such as

interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-

Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN) is a prevalent neuropathic pain condition, characterized by pain persisting for a month or more after the resolution of a herpes zoster rash. It is the most common complication following herpes zoster infection, affecting 5–20% of patients, especially among the elderly, with a significant proportion developing chronic, persistent pain [110, 111]. PHN manifests primarily as neuralgia, which can be categorized into three types: (1) spontaneous, persistent, throbbing, burning pain; (2) stabbing, shooting, paroxysmal pain; and (3) severe pain triggered by non-nociceptive stimuli (allodynia) [112]. Clinically, PHN often presents with persistent pain, sensory abnormalities, sleep disruptions, and emotional comorbidities [113]. A recent study [114] indicated that patients with PHN exhibit higher levels of E. coli-Shigella, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Clostridium compared to healthy controls, while Fusobacterium, Butyricoccus, Tyzzerella, Dorea, Parasutterella, Romboutsia, Megamonas, and Agathobacter were significantly lower. These variations suggest that dysregulated gut microbial ecology may play a key role in PHN pathogenesis [114]. Different gut microbiota have distinct roles in PHN development. For example, Ruminococcaceae, a predominant genus in the human gut, produces SCFAs, which enhance intestinal barrier integrity and exert anti-inflammatory effects on epithelial cells [115, 116]. The gut microbiota not only contributes to PHN development but also includes beneficial bacteria that can mitigate PHN-associated neuropathic pain. Deng et al. [117] reported that Ruminococci have a protective effect against PHN, while Trichosporonaceae may reduce PHN risk. Conversely, Candida increases PHN risk, and Eubacterium, a prominent gut flora member, has been found to promote PHN.

Trauma-induced neuropathic pain (TINP), also known as traumatic neuropathy or nerve injury pain, is a chronic pain disorder resulting from neurological damage caused by physical trauma. This type of injury can stem from various traumatic events, such as accidents, falls, sports injuries, surgeries, or other physical traumas [118].

The Chronic Constriction Injury (CCI) model of the sciatic nerve is extensively utilized to study NP in rodents following peripheral nerve injury [119]. Research indicates that Akkermansia, Bacteroides, and Desulfovibrionaceae are notably abundant in the feces of CCI model mice, suggesting that these strains may play a significant role in TINP pathophysiology. To validate the involvement of gut flora in CCI-induced pain, studies have shown that transferring fecal bacteria from control to antibiotic-treated mice restored thermal nociceptive hypersensitivity in NP [97], while depletion of SCFA-producing bacteria reduced CCI-induced NP symptoms [50].

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is one of the leading causes of mortality and disability worldwide, with over 50 million cases annually [120]. Major causes of TBI include falls, motor vehicle accidents, and domestic violence. Intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction is often an immediate consequence of TBI, with compromised barrier function observable up to four days post-injury [121]. TBI disrupts gut-brain axis communication mechanisms, triggering a systemic stress response involving activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic branch of the ANS, resulting in the release of glucocorticoids and catecholamines.

Pretreatment with Lactobacillus acidophilus or Clostridium butyricum mitigates the neurological effects of TBI, supporting the potential of microbiota modulation as a therapeutic strategy in traumatic brain injury [120]. These results highlight the role of gut microbiota in both TINP and TBI, underscoring its influence on injury-induced neuropathic pain and central nervous system recovery.

Trigeminal Neuralgia (TN) is a rare, unilateral facial pain characterized by electric shock-like sensations, often triggered by light tactile stimuli. Due to its presentation along the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve, TN is frequently misdiagnosed as an oral condition [122]. Research indicates that pamatin may alleviate experimentally induced colitis via sodium dextran sulfate, enhancing mucosal integrity and reducing apoptosis. In pamatin-treated mice, gastrointestinal microbiota analysis showed an increased abundance of Mycobacterium anisopliae and Mycobacterium thickum, while reducing Mycobacterium anisopliae, which helped prevent transgenerational dysbiosis [123]. These findings suggest that intestinal microbiota modulation by pamatin could represent a future therapeutic approach for TN pain management.

Migraine Headaches

Migraine, a widespread polygenic neurological disorder, ranks as the second leading cause of disability worldwide [124] and affects over one billion people globally as a chronic, lifelong condition [125].

Key mechanisms in migraine pathogenesis include sensitization of the trigeminal

vascular system and cortical hyperexcitability [126], with Cortical Spreading

Depolarization (CSD)-induced neuronal sensitization identified as central to

migraine pain attacks [127]. Studies report a higher prevalence of migraine among

patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) [71]. Crawford et al. [127]

proposed that gut microbiota dysregulation may contribute to migraine

pathogenesis by modulating TNF-

Cancer significantly impacts human health and survival, with over 70% of

patients experiencing cancer-related pain [129]. Opioids remain the primary

treatment for moderate to severe cancer pain, with oxycodone and morphine as

first-line oral options [130]. Studies reveal that gut microbiota dysregulation,

inflammatory cytokine release, compromised intestinal mucosal barrier function,

and bacterial translocation in opioid-tolerant models contribute to persistent,

chronic systemic inflammation [131, 132]. Opioid use has been shown to alter gut

microbiota composition and function, with this dysregulation activating Toll-like

receptor 2/4 (TLR2/4) receptors [133], leading to substantial pro-inflammatory cytokine

release (e.g., TNF-

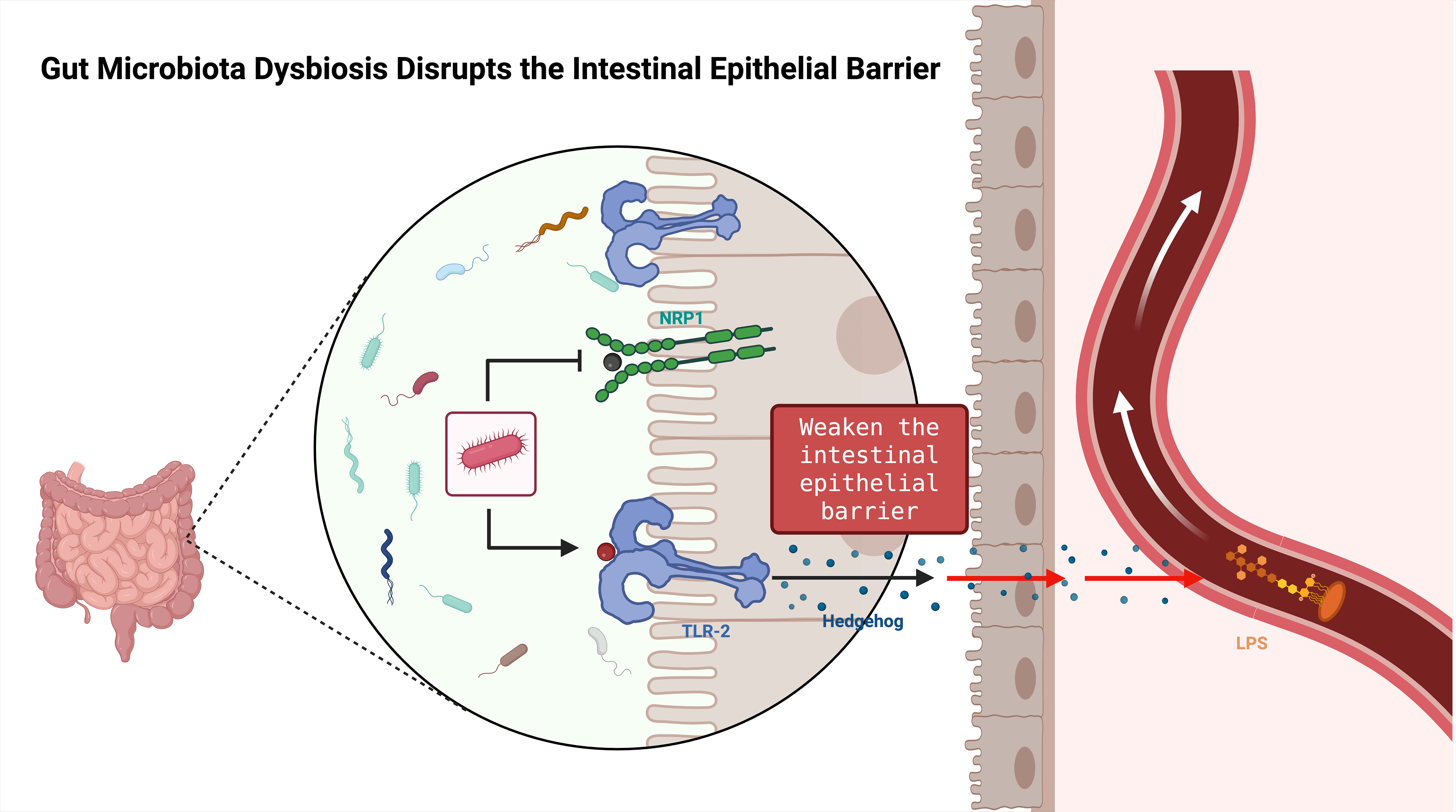

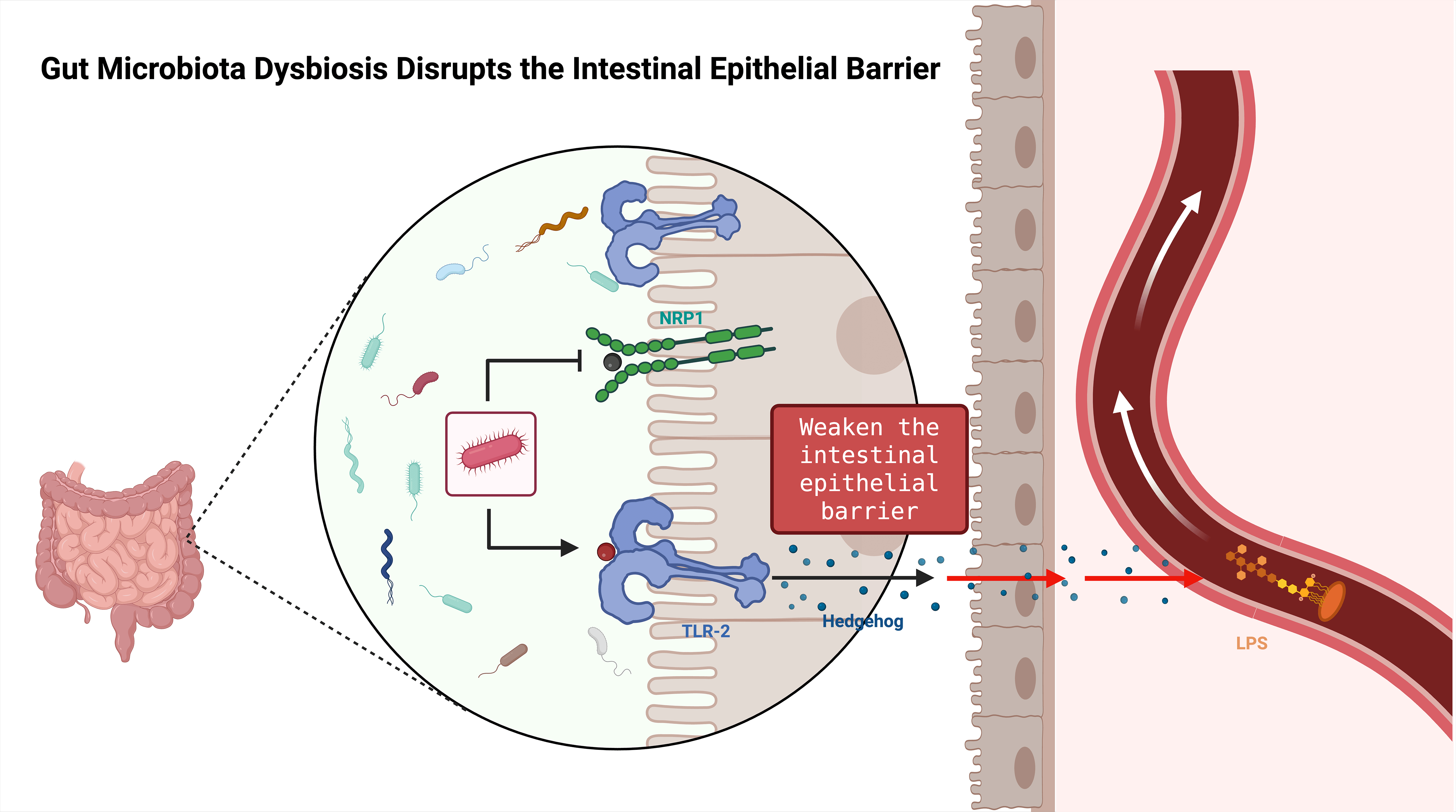

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of gut microbiota dysbiosis disrupting the intestinal epithelial barrier. Dysbiosis weakens epithelial barrier function, reduces tight-junction protein levels, increases intestinal permeability, and thereby exacerbates neuroinflammation and peripheral nerve injury. LPS, Lipopolysaccharide. Created with BioRender (http://www.biorender.com/).

Intestinal microbiota is now recognized as a factor in various types of NP, leading to a range of therapeutic approaches. Currently, NP management predominantly relies on Western pharmaceuticals, particularly antidepressants and antiepileptics. However, as a chronic pain condition, NP often requires long-term treatment, raising concerns over drug dependence and adverse effects, which challenge the overall safety and efficacy of these medications [137]. Consequently, the development of alternative therapeutic approaches has become increasingly urgent. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), a cornerstone of Chinese healthcare, offers significant therapeutic benefits with minimal side effects. Classical Chinese herbal formulas, in particular, provide effective pain relief with a lower risk of adverse reactions.

The Expert Consensus on Chinese and Western Medicine Diagnosis and Treatment of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathic Pain recommends Huangqi Gui Zhi Wu Wu Tang (with a high recommendation level of A+ and high-quality evidence), an efficacy confirmed in prior studies [138]. Additionally, CINP may be managed and prevented through external application of Juan Bi Tang, composed of Astragalus, Angelica sinensis, Red peony, Qiangwu, Turmeric, and Licorice. The integration of Chinese and Western medicine in NP treatment has shown to be beneficial in slowing disease progression and enhancing patient quality of life, supporting the potential for combined approaches in managing neuropathic pain effectively.

Research indicates that acupuncture effectively alleviates pain, with substantial clinical and experimental evidence supporting its analgesic properties. Litscher et al. [139] demonstrated that acupuncture enhances blood circulation in the limbs, which may aid nerve repair by promoting axonal and myelin sheath improvement. Gabapentin, a GABA derivative with analgesic properties, is commonly used for neuropathic pain relief. Some studies indicate that acupuncture may be more effective than vitamin B1 and gabapentin for peripheral neuropathy, highlighting its potential for neuropathic pain improvement [140]. Increasing research on Chinese medicine for CINP underscores its unique advantages, offering pain relief with minimal side effects, making it a promising approach for CINP prevention and treatment.

FMT is a distinctive approach to restoring gut microbiota balance by introducing

functional microbiota from healthy donors into the gut of affected individuals.

Studies demonstrate FMT’s potential to prevent or mitigate neuropathic pain

induced by neurological injuries, chemotherapy, and diabetes. For instance, Ma

et al. [97] reported that fresh fecal transplantation could counteract

gut flora depletion and alleviate neuropathic pain by restoring microbiota

balance. Deng et al. [117] found that paeoniflorin alleviated

oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy by modulating gut flora to reduce

neuroinflammation; subsequent FMT with paeoniflorin-treated bacteria showed

downregulation of IL-6 and TNF-

Probiotics support a favorable environment for normal gut flora growth, helping maintain intestinal microbiota balance [144]. They are widely used in the prevention and treatment of various diseases, interacting with gut flora through nutrient competition, antagonism, and symbiosis [145, 146].

Research shows that probiotics positively impact gut function by enhancing gut barrier integrity, up-regulating mucus secretion genes, and down-regulating inflammatory factor expression [147]. Additionally, probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics (combinations of probiotics and prebiotics that work synergistically) can prevent chemotherapy-induced mucositis with minimal risk of sepsis [148]. Lactobacilli, widely employed as probiotics, offer health benefits such as anti-diabetic activity, cancer inhibition, anti-ulcer effects, immunomodulation, and microbiota regulation. For neuropathic pain, Lactobacillus strains F1 and F2 reduce mechanical nociceptive hypersensitivity and cold allodynia, likely through immune system modulation by influencing TLR2 and TLR4 expression levels. These therapeutic strategies not only present new clinical targets for integrating Chinese and Western medicine but also provide valuable insights into the mechanisms connecting gut microbiota and neuropathic pain.

The relationship between intestinal microbiota and NP has become a focal point in both Chinese medicine and modern medical research. Evidence suggests that the gut microbiota not only plays a pivotal role in NP development but may also directly impact pain onset and relief through its metabolites. The gut microbiota occupies a pivotal position at the nexus of the gut-brain axis and the neuro-immune-endocrine axis, exerting both direct and indirect influences on chronic pain. A diverse array of signaling molecules originating from the gut microbiota, including microbial metabolites, neuromodulators, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters, modulate peripheral and central sensitization pathways by engaging with their respective receptors. This interaction significantly impacts the development and progression of chronic pain. A healthy gut microbiota can modulate immune system function by enhancing anti-inflammatory cytokine production and suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines, which helps alleviate pain. Conversely, the overgrowth of harmful bacteria may intensify inflammatory responses and, via the gut-brain axis, negatively influence the central nervous system, thereby exacerbating NP symptoms.

The gut microbiota has been extensively utilized in clinical treatment. Clinical evidence suggests that probiotics can mitigate symptoms of anxiety and depression, while strains like Bifidobacterium can improve intestinal barrier function and impede pathogen adhesion, thus preventing and treating gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [149]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been employed to address gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders. A recent systematic study by [150] presents compelling evidence that fecal microbiota transplantation aimed at the gut-brain axis can alleviate symptoms of sadness and anxiety [151]. Moreover, some strains of Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium breve may provide neuroprotective benefits by diminishing neuroinflammation and modulating the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [152]. Research conducted by Sun et al. [153] demonstrates that Clostridium butyricum can regulate the dysfunctional gut-brain axis to provide neuroprotective effects in a murine model of Parkinson’s disease, and oral administration of this bacterium can ameliorate gut microbiota dysbiosis.

Approaches to regulating gut microbiota include probiotic supplementation, fecal microbiota transplantation, dietary adjustments, and TCM treatments. The bidirectional regulation mechanism of the gut-brain axis opens new avenues for NP treatment, although many questions remain. For instance, what are the specific characteristics of gut flora in chronic pain conditions? How does the gut microbiota contribute uniquely to various types of pain? To address these questions, future research could delve into the molecular mechanisms by which gut microbiota influences NP, employing advanced techniques like metabolomics and metagenomics to identify novel targets and pathways involved in pain modulation. Moreover, integrating TCM’s holistic regulatory approaches—such as combined herbal compounds with modern biotechnological advancements—may broaden the exploration of chronic pain mechanisms, including NP.

In summary, via the gut–brain axis, the intestinal microbiota can release analgesic metabolites such as GABA and BDNF, yet when dysbiotic it can also drive peripheral and central sensitization, making it a pivotal regulator of both the initiation and maintenance of neuropathic pain. At the clinical level, probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation, and integrated traditional Chinese medicine have already shown promise for alleviating NP symptoms, but the precise microbial signatures, strain specificity, and their relationships with distinct NP subtypes remain unclear. Future work should integrate metabolomics, metagenomics, and germ-free animal models to dissect the molecular targets along the microbiota–nerve axis, while high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to deliver precise, individualized therapeutic strategies for NP.

YXJ: Conceptualization, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing. HZX: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. WSZ: Figure and table preparation, Writing—Original draft. SBJ: Investigation. HZP: Figure and table preparation, Writing—Original draft. JY: Data curation. HNY: Literature search, Supervision, Project administration. JS: Writing—Original draft, Software, Visualization. QL: Literature search, Writing—review & editing. NXL: Visualization. YS: Literature search, Writing—review & editing. JQF: Interpretation of data for the work. MZL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

China National Natural Science Foundation (82104838), China Promotion Foundation Spark Program (XH-D001), Liaoning Provincial Key Research and Development Programme (2024JH2/102500062), Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2025-MSLH-490).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.