1 Department of Food Technology and Nutrition, Chonnam National University, 59626 Yeosu, Republic of Korea

2 Functional Biomaterials Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), 56212 Jeongeup-si, Republic of Korea

3 French Korea Aromatics Co., Ltd., 16986 Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

4 College of Food Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, 266003 Qingdao, Shandong, China

5 Division of Practical Application, Honam National Institute of Biological Resources (HNIBR), 58762 Mokpo, Republic of Korea

6 Department of Marine Bio-Food Sciences, Chonnam National University, 59626 Yeosu, Republic of Korea

Abstract

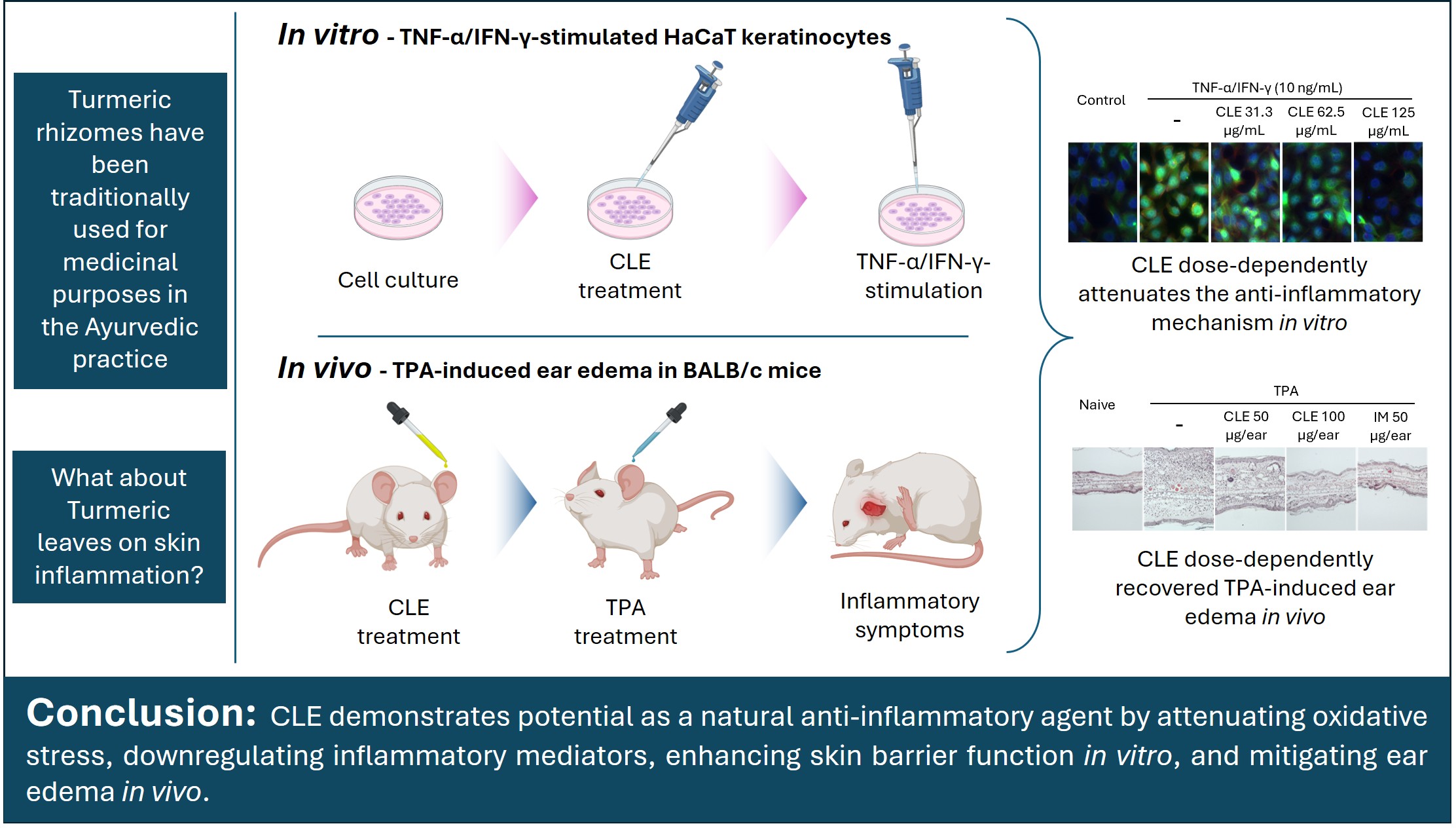

Plant-derived treatments for skin inflammation are gaining increasing interest, driven by the growing demand for safer alternatives to conventional synthetic drugs. Curcuma longa L. (turmeric) is traditionally utilized in many Asian countries for various pharmacological applications. Although the inflammation-suppressing properties of turmeric rhizomes are well established, the bioactive potential of its leaves and pseudostems remains largely unexplored. This study investigates the effects of turmeric leaf and pseudostem extract (CLE) on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α/interferon (IFN)-γ-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes (HK) and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced ear edema in a mouse model.

Cell viability and intracellular ROS levels in response to CLE were assessed. The potential of CLE to suppress inflammation was evaluated by monitoring the inhibition of signaling pathways and changes in cytokine/chemokine expression through Western blotting and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analyses. CLE was also examined for its impact on skin hydration and tight junction integrity. For in vivo analysis, an ear edema model was established using female BALB/c mice (7 weeks old).

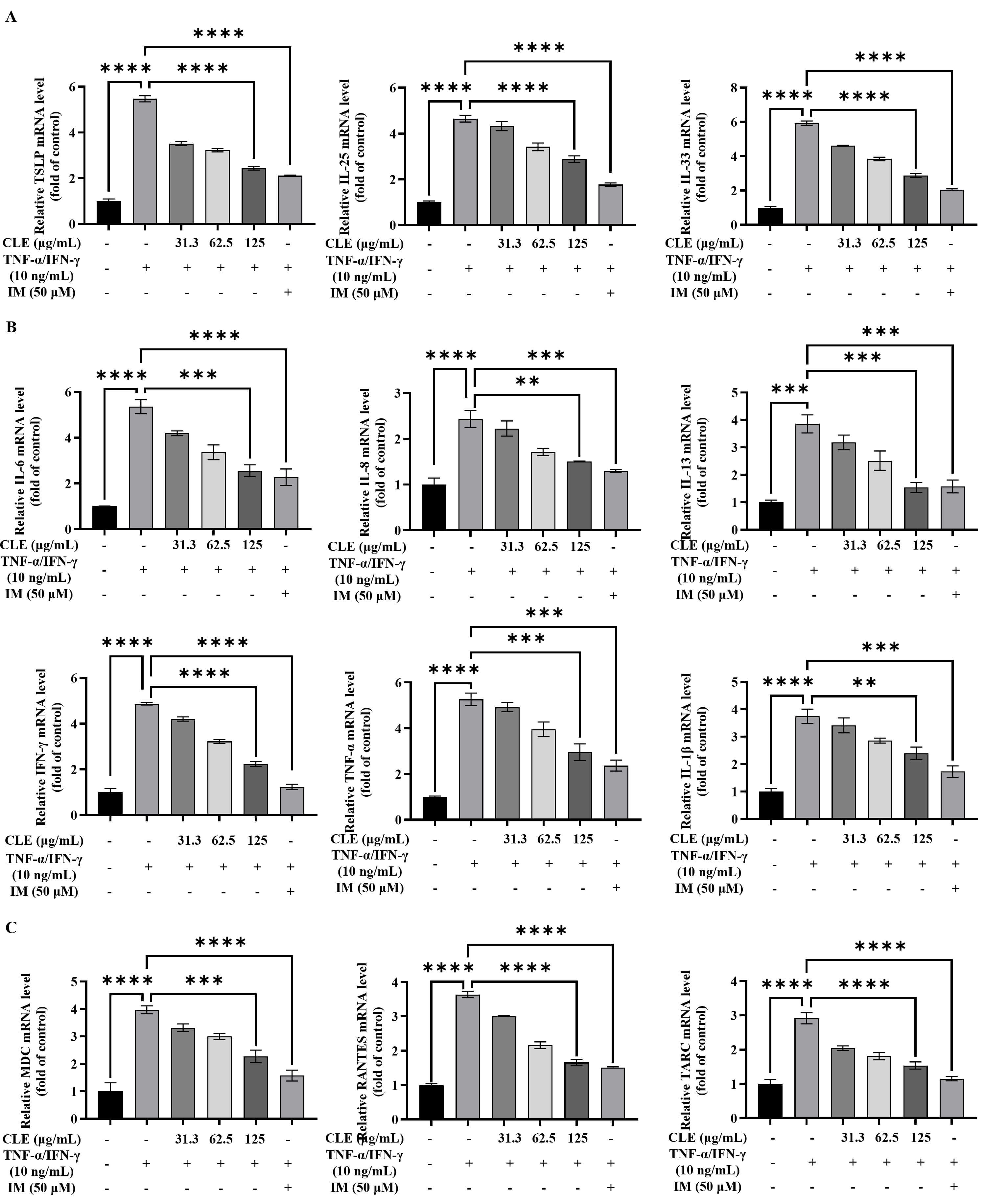

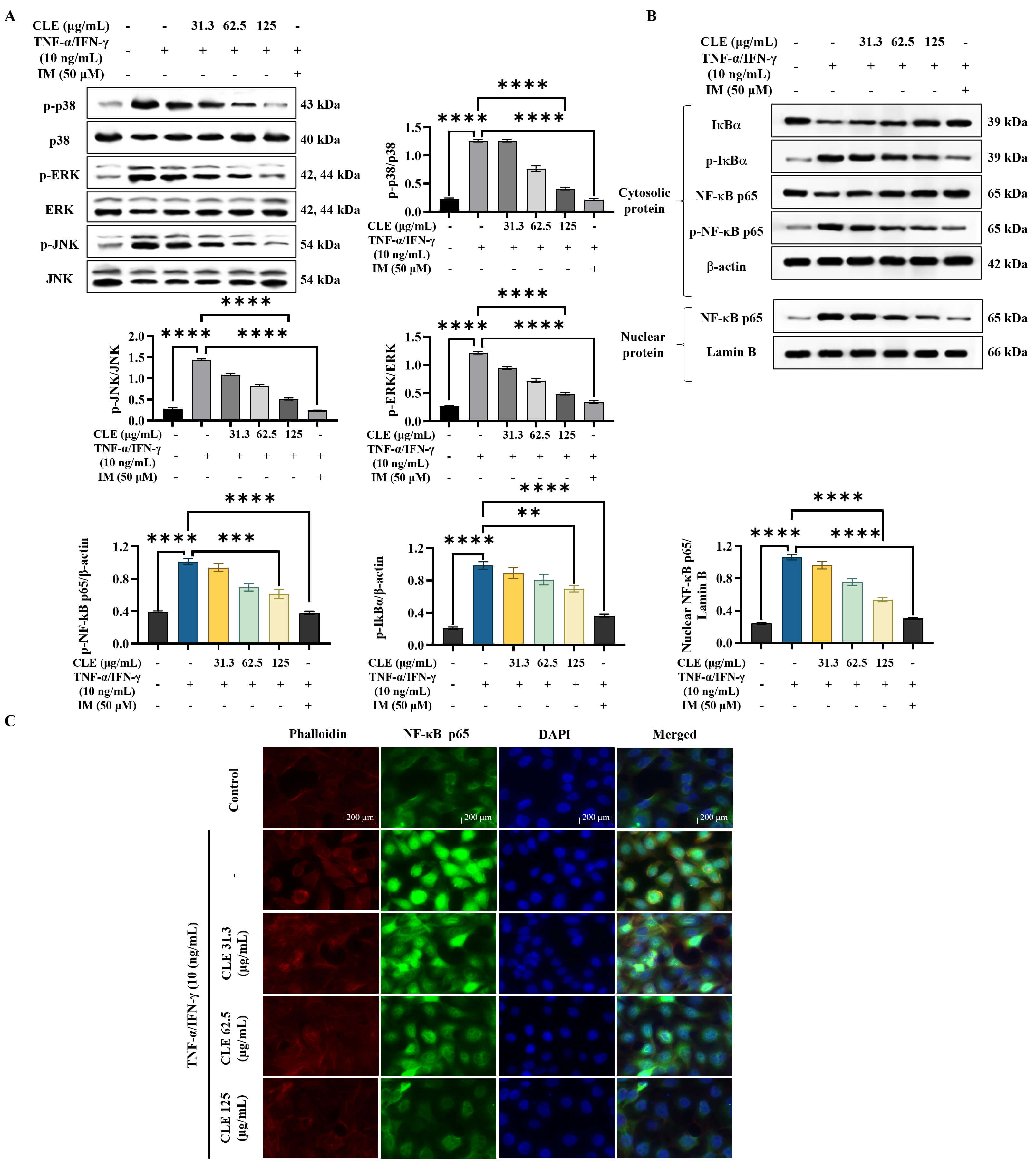

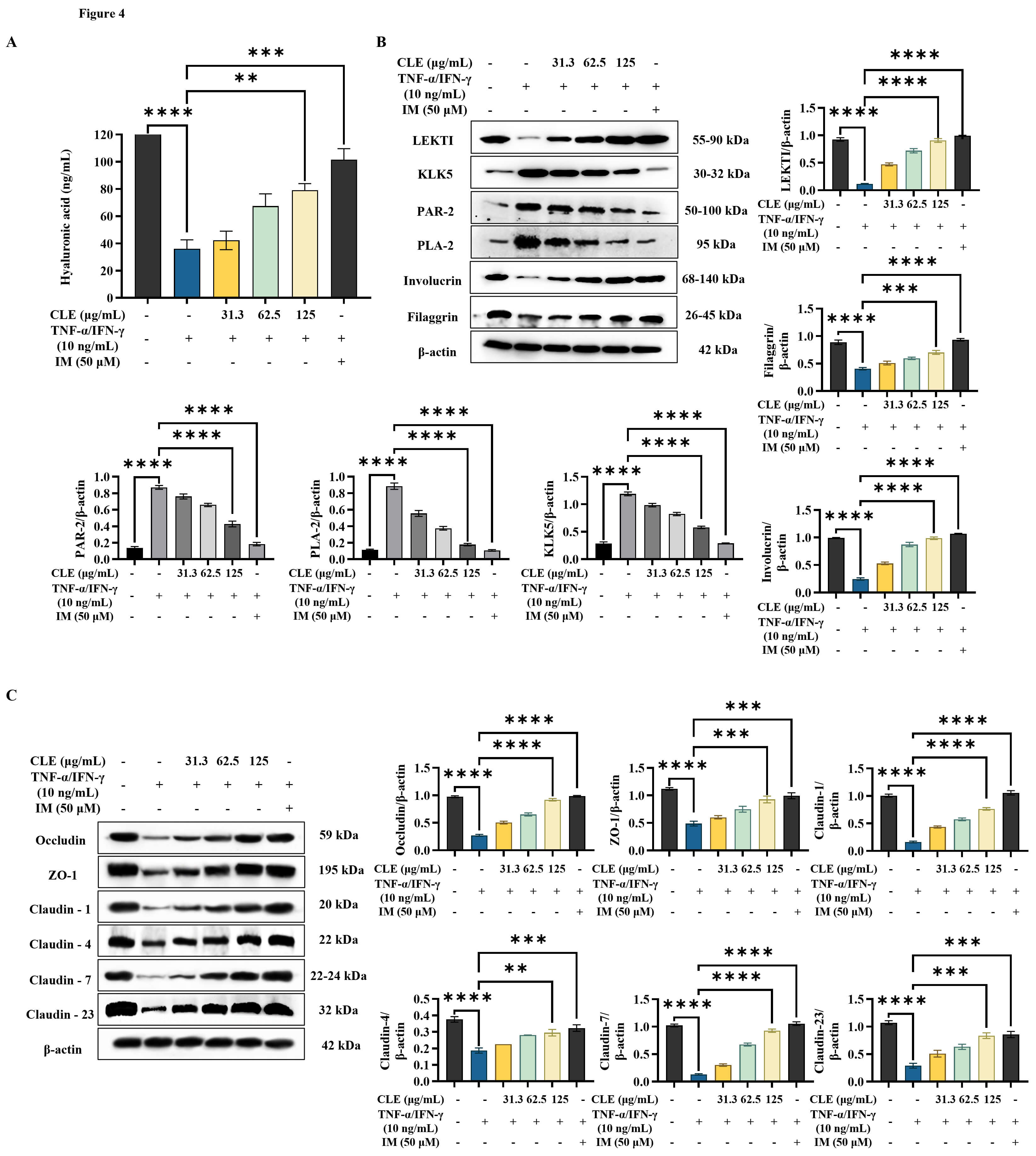

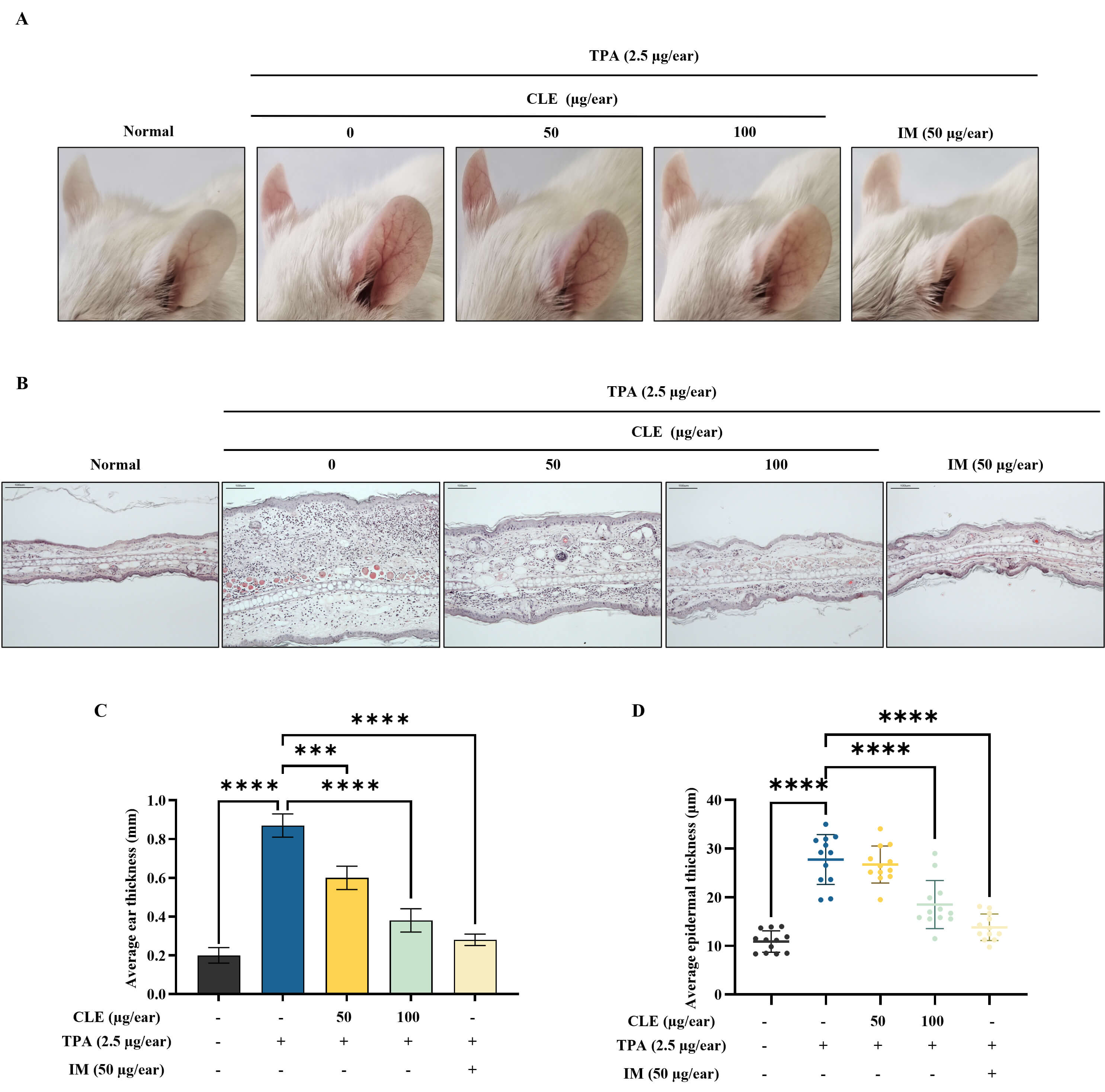

CLE treatment led to a dose-dependent decline in intracellular ROS and enhanced cell viability of TNF-α/IFN-γ-stimulated HK. Treatment with CLE resulted in decreased transcription of epithelial-derived cytokines (thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-25, IL-33), pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-6, IL-8, IL-13, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β), and chemokines (macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), regulated on activation, normal T cells expressed and secreted (RANTES), thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC)), along with inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling proteins in stimulated HK. CLE improved expression of proteins associated with skin hydration and tight junctions, helping to preserve moisture balance and structural integrity. Moreover, CLE markedly reduced ear redness, swelling, and thickness in 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced mice, while alleviating histopathological changes, including inflammatory cell infiltration and dermal thickening. Additionally, CLE effectively diminished inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the ear tissues of edema-induced mice.

Collectively, CLE exhibited potential as a natural anti-inflammatory agent by attenuating oxidative stress, downregulating inflammatory mediators, enhancing skin barrier function in vitro, and reducing ear edema in vivo.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- Curcuma longa

- inflammation

- keratinocytes

- cytokines

- edema

The skin safeguards the human body by acting as the primary defense against

environmental stressors. Chronic exposure to environmental stressors can impair

the skin barrier, triggering inflammatory responses that disrupt skin homeostasis

[1, 2]. Symptoms of skin inflammation, initially acute, can progress to chronic

states, contributing to the development of dermatological conditions, including

rosacea, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis [3, 4]. Activation of epidermal

keratinocytes and immune cells in response to external stimuli plays a central

role in mediating inflammation through elevating intracellular ROS levels,

promoting the release of inflammatory mediators and signaling pathways, and

ultimately impairing the skin barrier. Stimulation of mitogen-activated protein

kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-

Accordingly, the investigation of natural compounds for treating skin inflammation has attracted increasing research attention. Previous studies have shown that anti-inflammatory plant extracts may serve as promising treatments for cutaneous inflammation by regulating inflammatory mediator expression and reducing cellular damage [6, 7]. Curcuma longa L. (turmeric), a rhizomatous perennial herb, is widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions, with particular prevalence in Asia [8]. Turmeric has been used as a medicinal herb since ancient times to mitigate and manage a wide range of conditions, including common colds, wounds, skin sores, diarrhea, throat infections, urinary tract infections, menstrual problems, digestive disorders, and liver diseases [9]. It has been extensively used for centuries in Ayurveda (India), Unani (Pakistan), and traditional medicine in Bangladesh for its diverse therapeutic properties, with records of use in India dating back at least 2500 years [10]. Accordingly, research has confirmed the pharmacological relevance of turmeric by identifying numerous bioactive phytochemicals, including curcumin, terpenes, phytosterols, flavonoids, and other phenolic compounds, in various plant parts, which exhibit anti-allergic, anti-atopic dermatitis, antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-tumor activities [8, 11]. Although considerable progress has been achieved, most investigations have concentrated on the turmeric rhizome. Data on the chemical composition, bioactivities, and therapeutic relevance of the aerial parts, particularly leaves and pseudostems remain limited. Their potential roles in modulating skin inflammation, redox homeostasis, and immune regulation have not been fully elucidated, emphasizing a critical knowledge gap that the present study seeks to address.

In line with this, our collaborative study identified twenty-one phenolic

compounds in turmeric leaf and pseudostem extract (CLE) [12]. Furthermore, we

previously examined the pharmacological effects of CLE against allergic responses

and atopic dermatitis using both cell-based and organismal models [8, 13].

Building on previous studies, this work focuses on exploring the effects of CLE

on inflammatory responses in the skin using both cellular and animal models.

Thus, the current study investigates the inflammation-regulating properties of

CLE in vitro, using tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and a

penicillin/streptomycin mixture were obtained from GibcoBRL (Grand Island, NY,

USA). Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) supplied

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT),

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA), dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO), paraformaldehyde, Triton™ X-100, TRIzol, indomethacin (IM), and

TPA. Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA) provided the protein ladder,

NE-PER® nuclear/cytoplasmic extraction kit, and

Pierce™ RIPA buffer. Primers were acquired from Bioneer Co.

(Daedeok-gu, Daejeon, Korea). Recombinant TNF-

HK were originally purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Korea). Short Tandem Repeat (STR)-verified, mycoplasma-free cells were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 under humidified conditions, using DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Subcultures were performed when the cells reached 70–80% confluence, and experiments were conducted during the exponential growth phase.

Cell viability in response to CLE treatment was evaluated using the MTT assay.

After treatment with CLE for 2 h, cells were stimulated for 24 h with a 1:1

mixture of TNF-

Intracellular ROS levels in response to CLE treatment were assessed through the DCF-DA assay. For this experiment, cells were first incubated with CLE for 2 h, followed by DCF-DA treatment. Fluorescence emission was detected using SpectraMax M2 equipment and further analyzed with a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

As described in Kirindage et al. [14], cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a ReverTra cDNA synthesis kit (FSQ-101, Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Gene amplification by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using PowerSYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Warrington, UK), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The relative changes in gene expression were determined using the 2-ΔΔCT approach and comparing each gene’s expression level to that of GAPDH. Supplementary Table 1 provides the primer sequences used for RT-qPCR. Hyaluronic acid (HA) levels were quantified with an ELISA kit (DHYAL0, R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Protein samples (30 µg each) were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide

gel and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, as described

previously [15]. Blocking of membranes was performed using 5% skimmed milk, and

incubation with primary monoclonal antibodies (1:1000) was carried out at 4

°C for 12 h. After washing, membranes were transferred into secondary

antibody solutions (1:3000) and incubated for 2 h. Protein bands were imaged with

a Davinch Mini Chemi Imaging system (Model: MW 420, Core Bio Davinch, Seoul,

Korea). WB primary antibodies, p-p38: #9211, p38: #8690, p-ERK: #4377, ERK:

#9102, p-JNK: #9251, JNK: #9252, I

Cells grown on chamber slides were rinsed with PBS before fixation in 4%

formaldehyde. Following treatment with a blocking buffer, they were exposed to

the primary anti-NF-

Seven-week-old female BALB/c mice, supplied by Orient Bio, Inc. (Gwangju,

Korea), were used in this study. Environmental conditions were regulated (23

The histology of mouse ear tissues treated with TPA was examined following a method described in an earlier study [16]. In brief, ear tissues were fixed in formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. Sections were deparaffinized (12 h, 40 °C), rehydrated, and stained with H&E solution (Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK). Mounted slides were visualized using a bright-field microscope (DM5000 B, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Statistical evaluations were conducted using GraphPad Prism software, version

10.4.2 (Boston, MA, USA). Data are presented as the mean

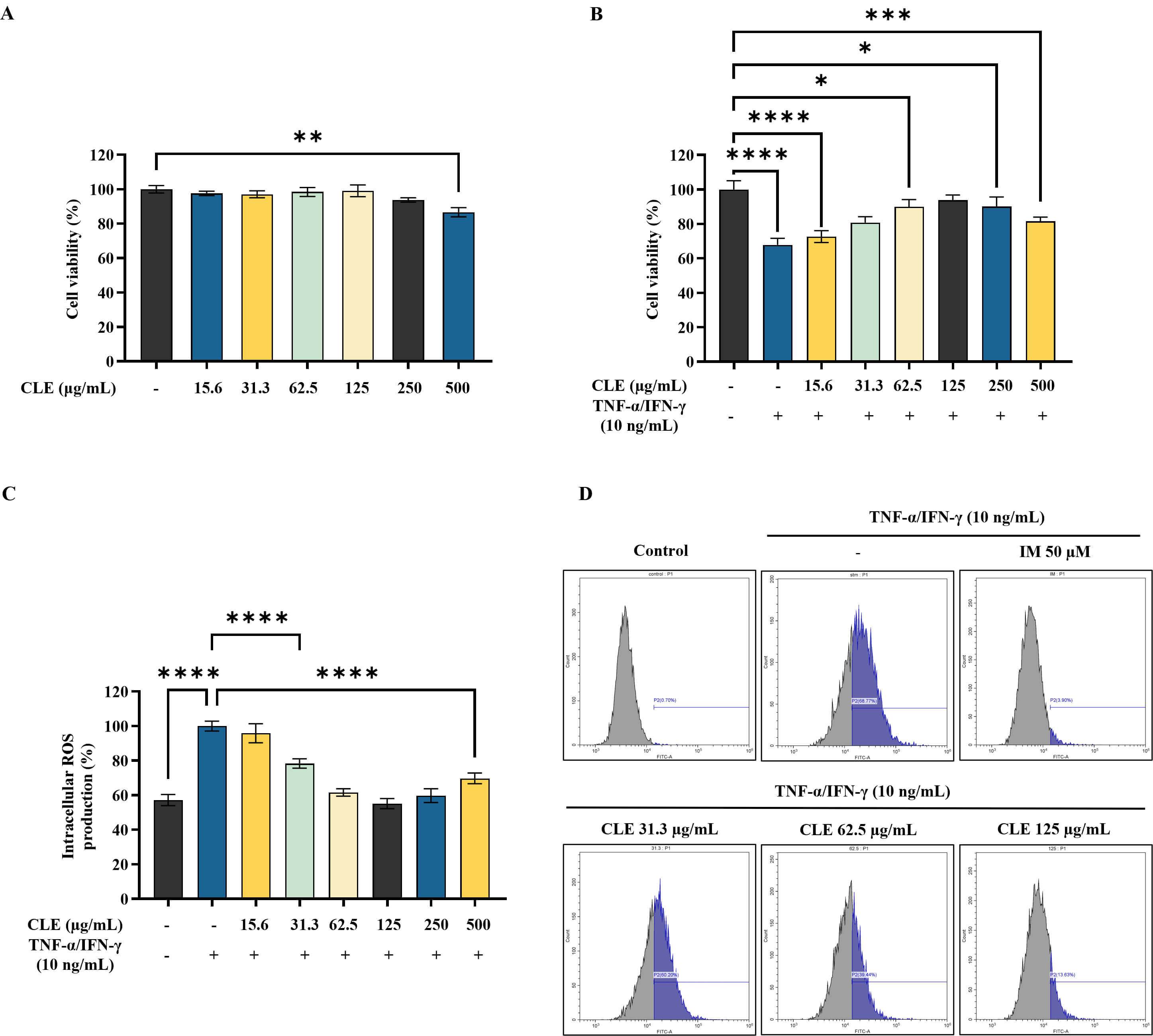

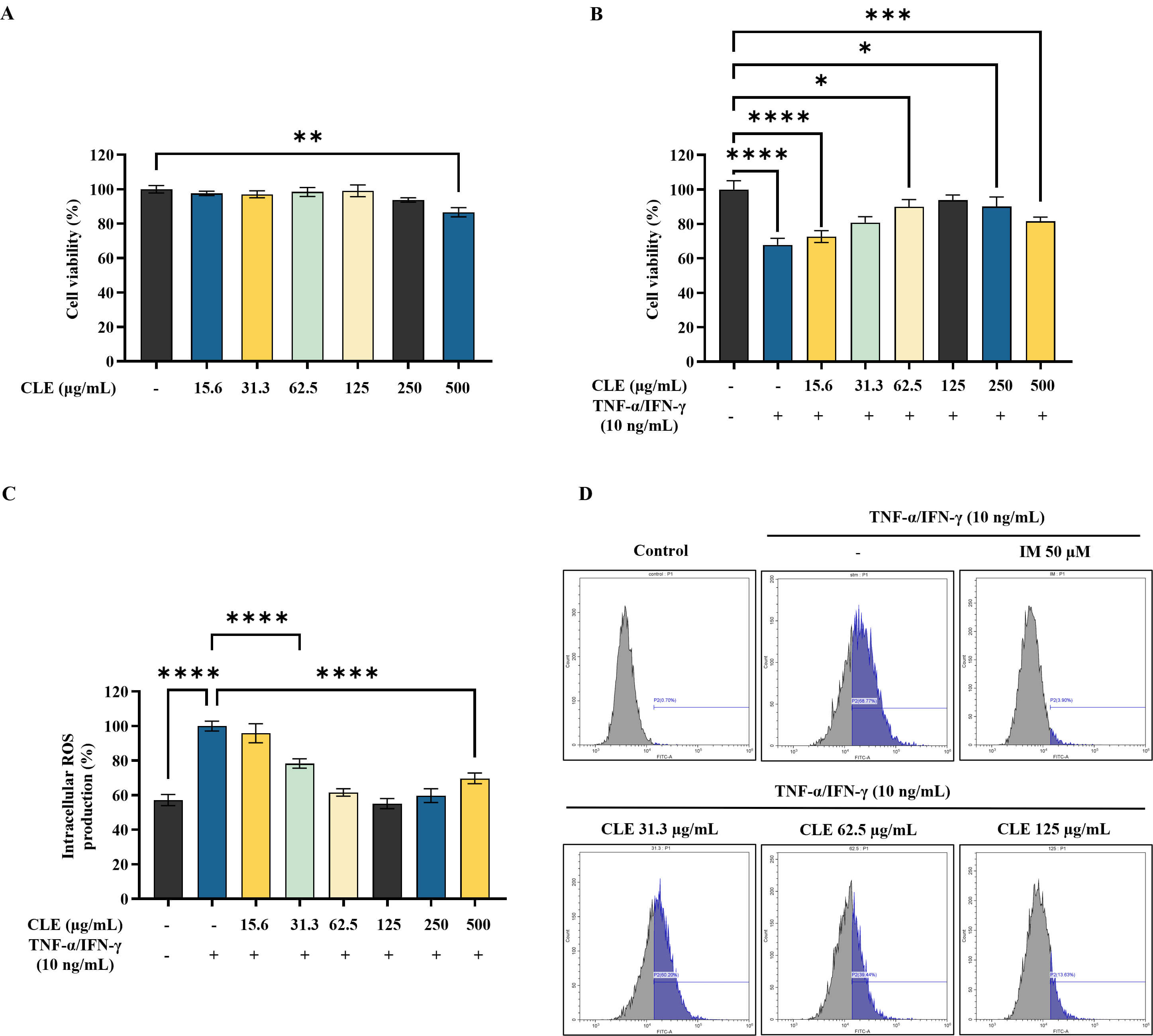

CLE showed no significant cytotoxicity at the tested concentrations in HK, as shown in Fig. 1A. Conversely, CLE significantly enhanced viability of stimulated HK, within the concentration range of 31.3 µg/mL–125 µg/mL (Fig. 1B). As presented in Fig. 1C, DCF-DA staining revealed that CLE progressively lowered intracellular ROS levels with increasing doses, which was further validated by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Protective effect of CLE in

TNF-

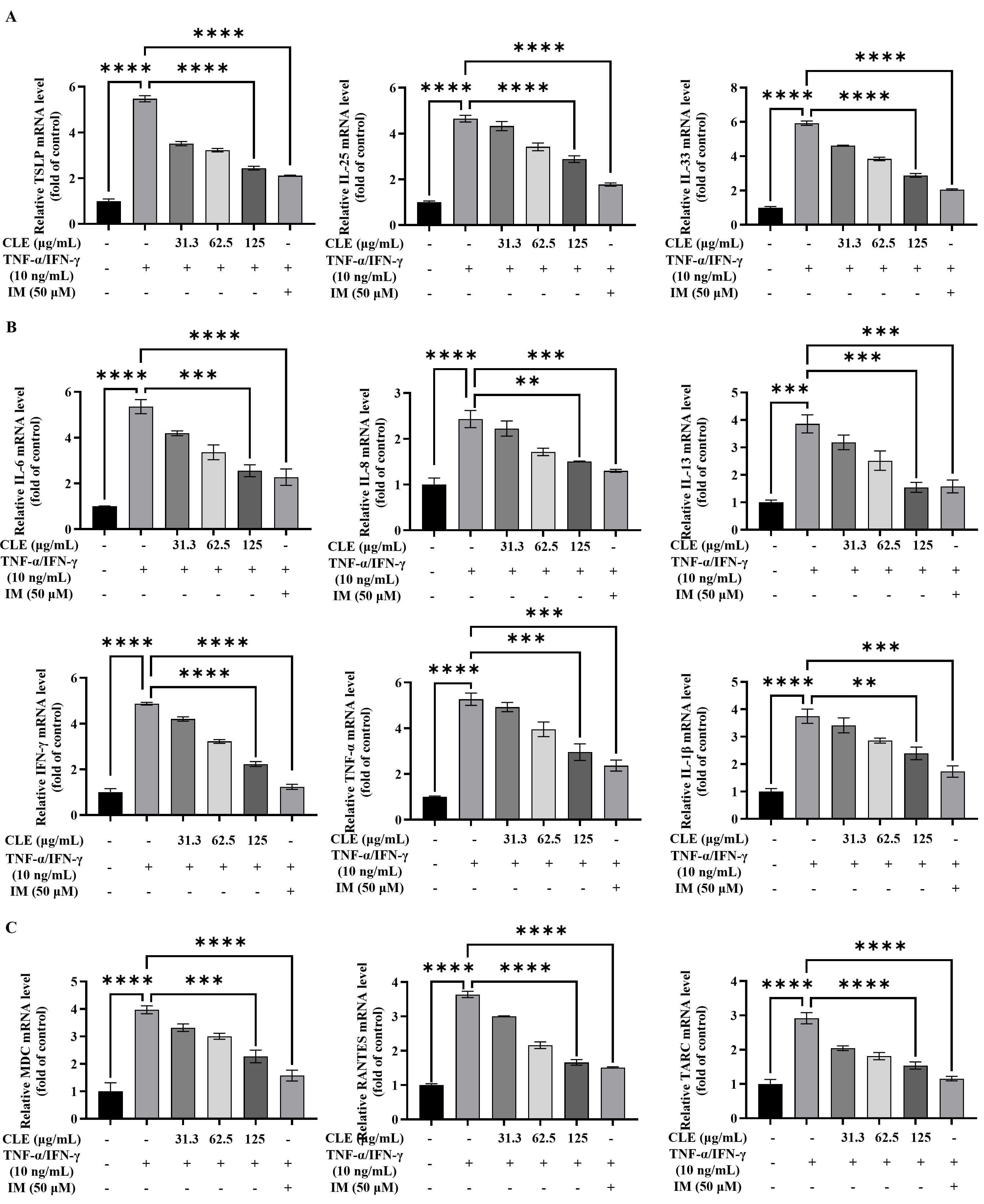

Stimulation with TNF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

CLE suppressed the expression of inflammatory mediators in

TNF-

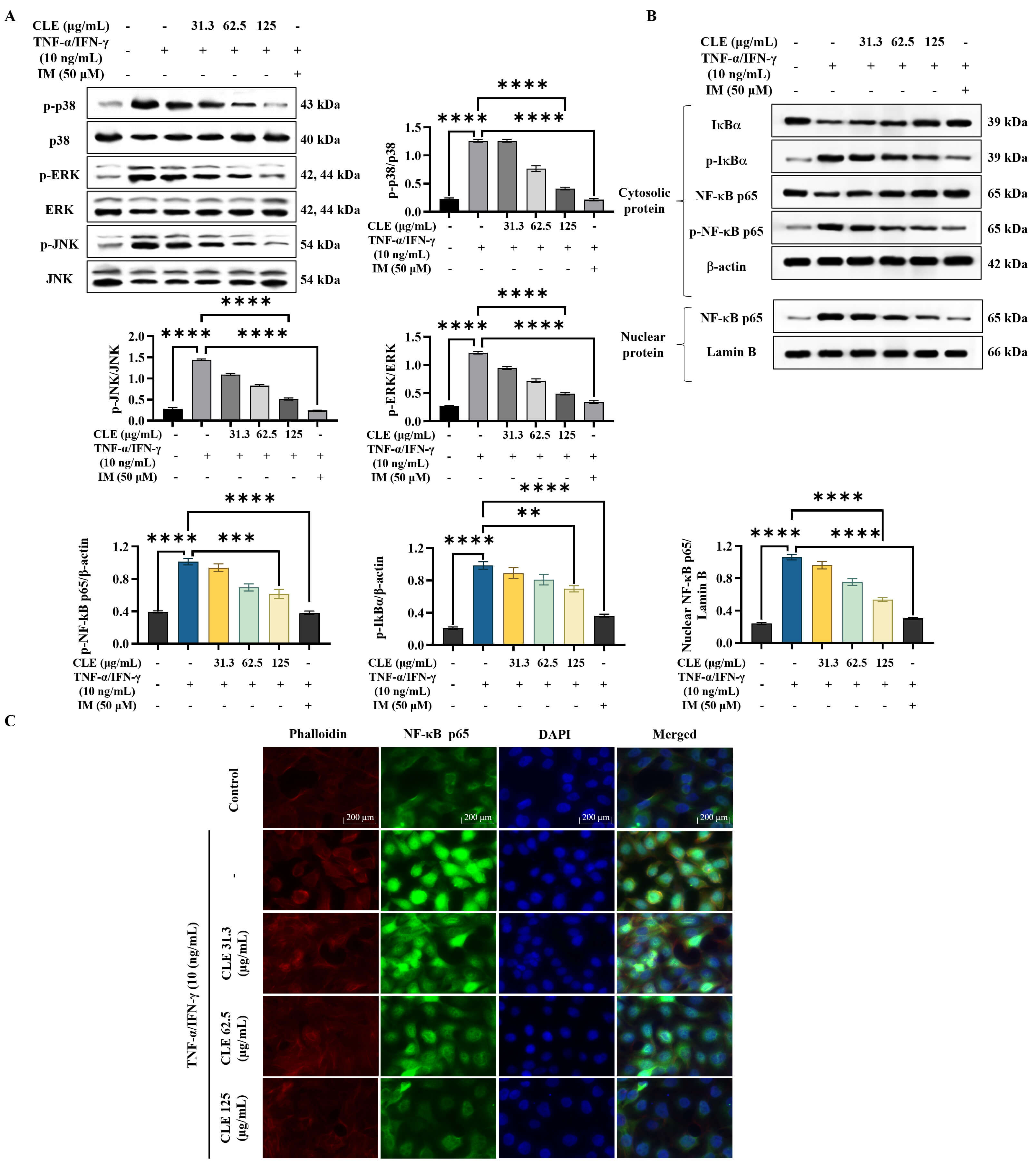

As shown in the WB results (Fig. 3A), stimulation with

TNF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

CLE attenuated the activation of inflammatory pathways in

TNF-

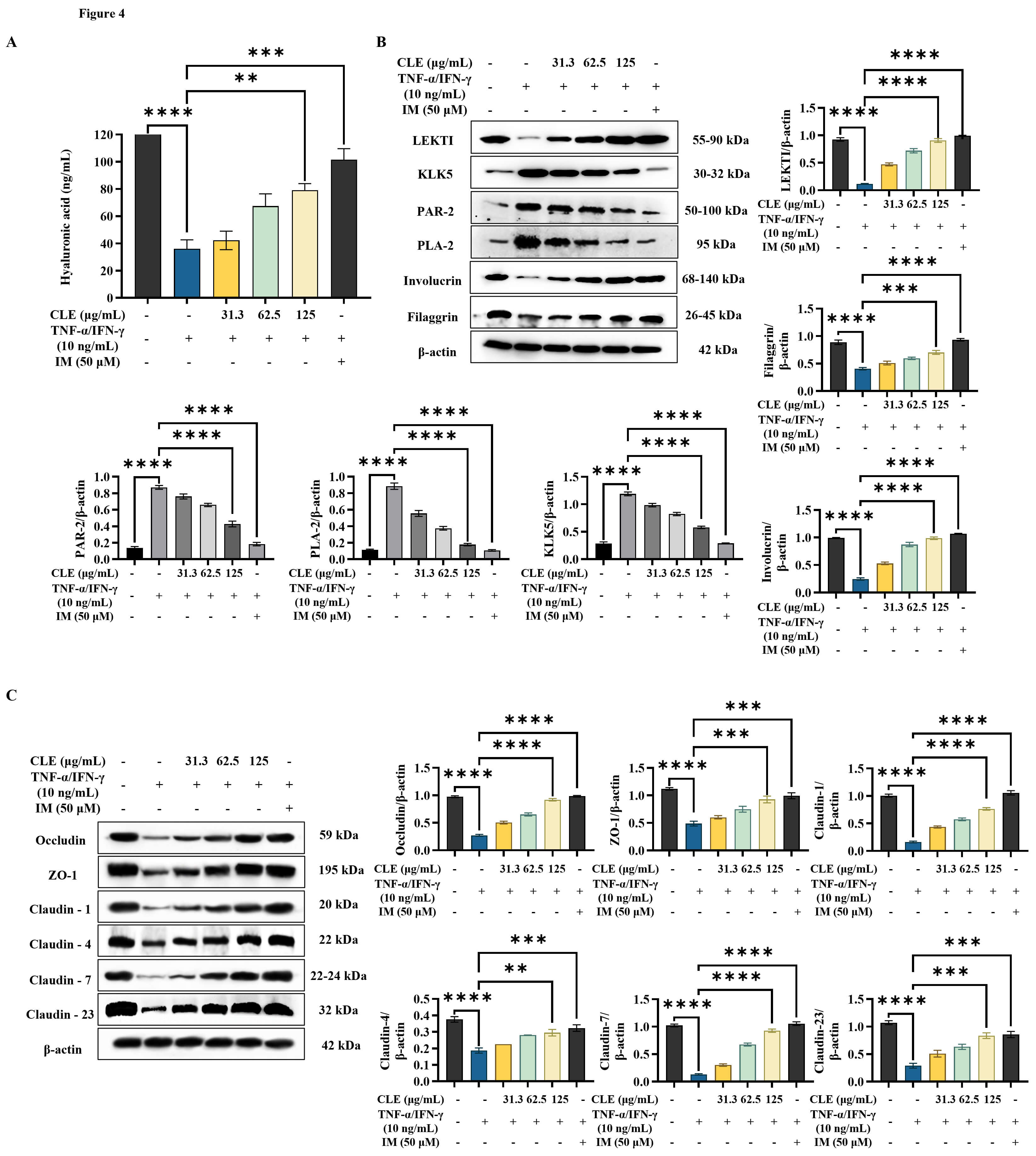

According to ELISA analysis results (Fig. 4A), TNF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

CLE improved the integrity of the epidermal barrier in

TNF-

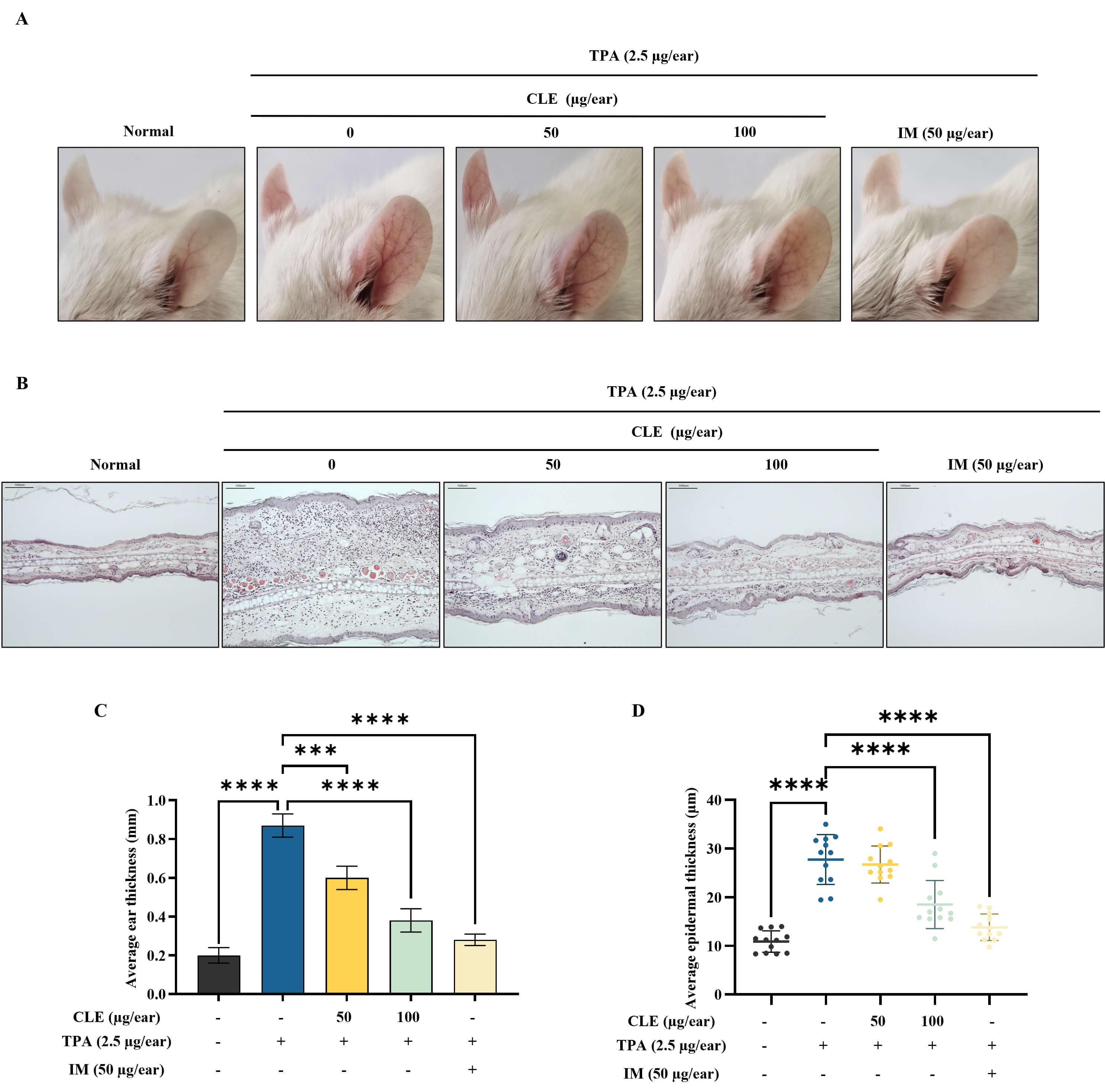

Fig. 5A shows representative images of ear redness and swelling in mice with edema. Accordingly, CLE visibly reduced ear redness and swelling in TPA-induced mice. H&E-stained ear tissue sections provided additional evidence supporting CLE’s anti-inflammatory activity. The TPA application increased inflammatory cell infiltration compared with the control. CLE dose-dependently alleviated these histopathological changes (Fig. 5B). Ear thickness measurements showed that TPA application significantly increased ear swelling, indicating severe edema. However, CLE reduced ear thickness in mice in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 5C). H&E-stained ear sections were analyzed to quantify epidermal thickness using image processing software (ImageJ, National Institute of Health, MD, USA), showing that CLE treatment reduced epidermal thickening in edema mice (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

CLE reduced TPA-induced ear edema in BALB/c mice. (A)

Representative images of the ears and swelling in edema mice. (B) Histological

evaluation of ear tissues was performed with H&E staining (scale bar: 100

µm). Alterations in (C) mouse ear thickness and (D) epidermal thickness.

Values are presented as mean

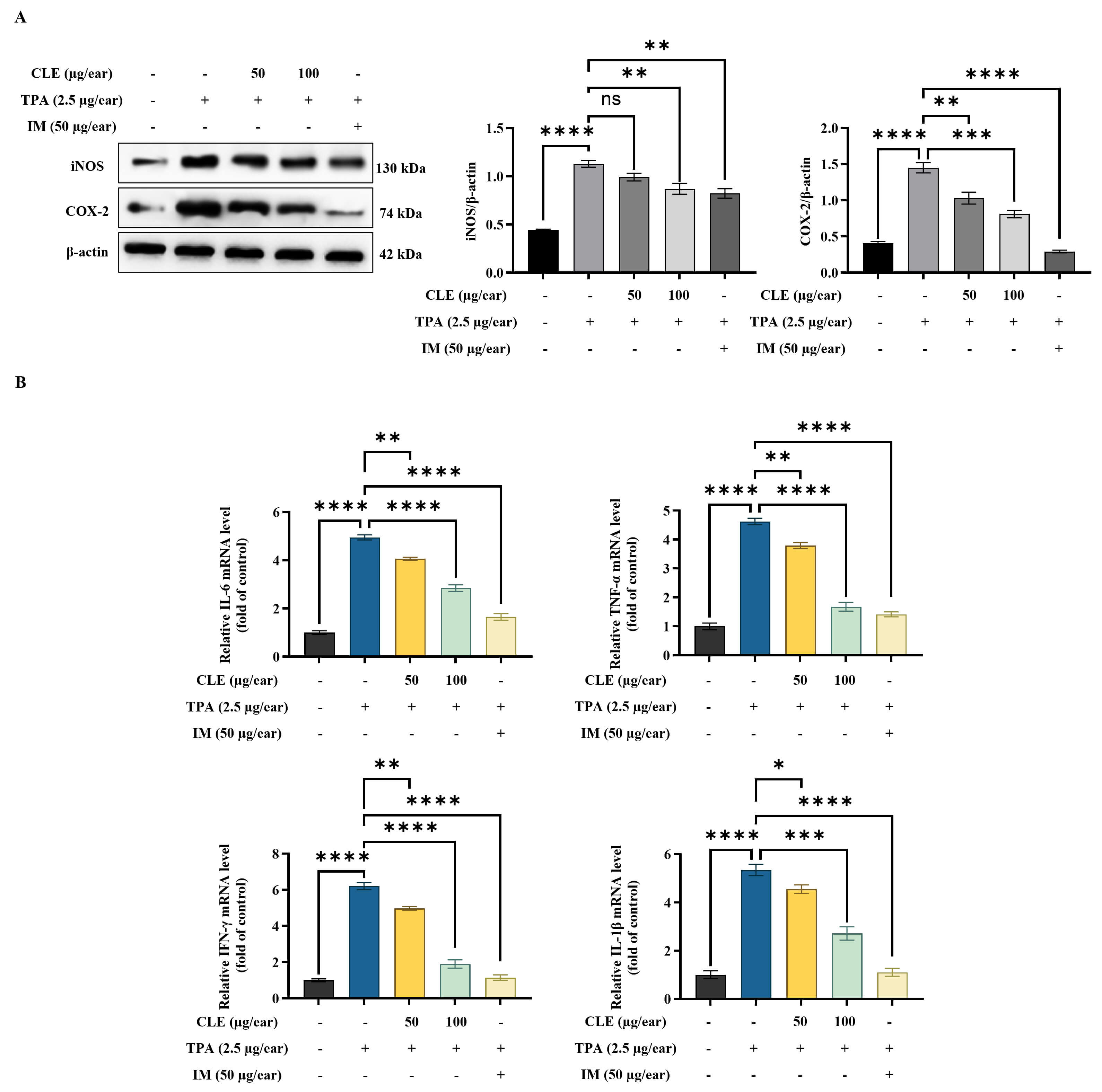

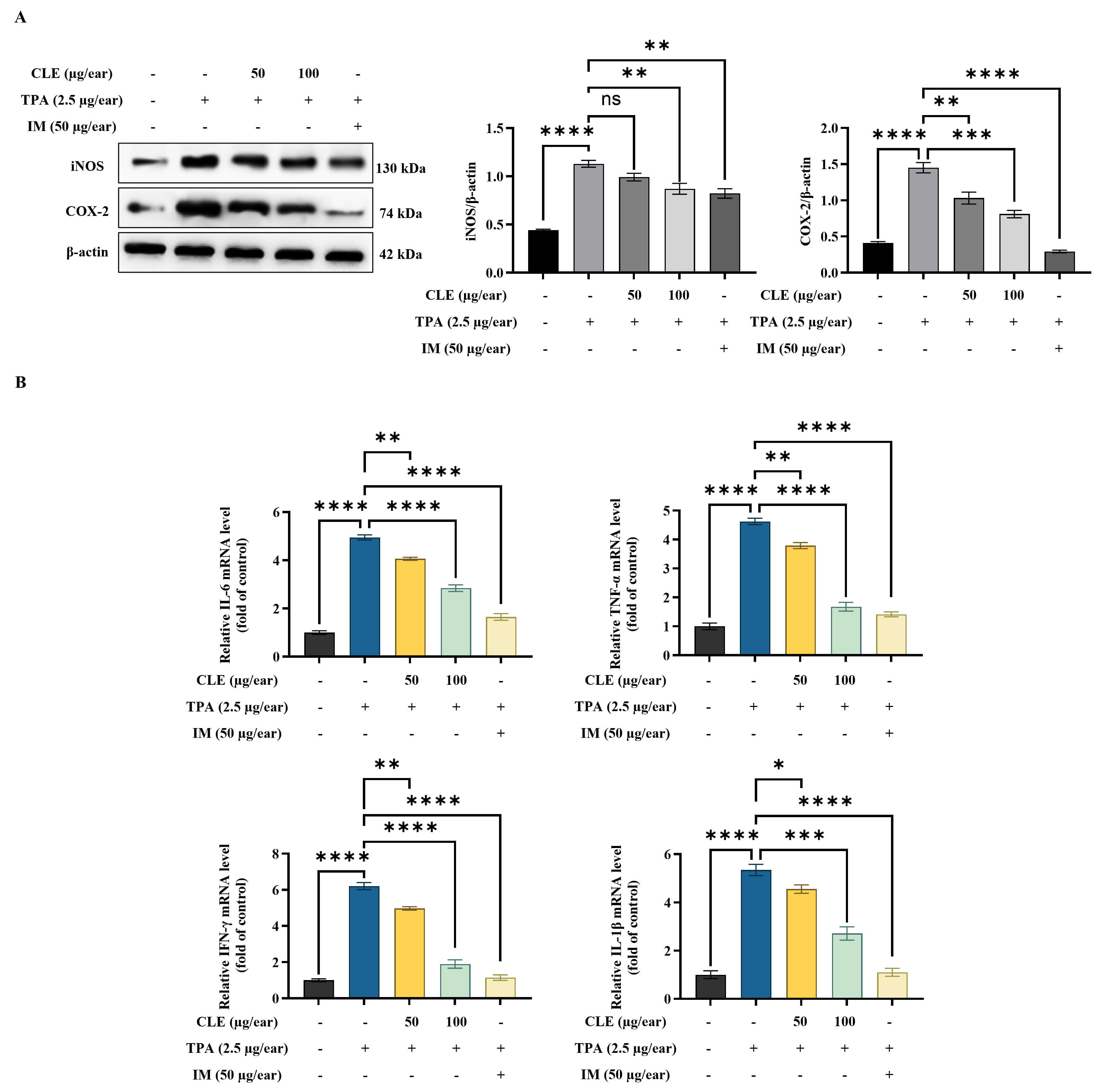

According to WB analysis, TPA increased inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)

and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) protein expression in ear tissues (Fig. 6A).

However, CLE effectively reduced the expression of these proteins in ear edema

tissues. Furthermore, TPA application significantly enhanced the transcription of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

CLE decreased inflammatory mediators in ear edema tissues. (A)

WB of iNOS/COX-2 protein expression. (B) Analysis of pro-inflammatory cytokine

mRNA expression levels using RT-qPCR. Relative mRNA levels were expressed

relative to the control group and are presented as fold changes. Values are

presented as mean

The identification of plant-derived anti-inflammatory treatments for skin

inflammation is essential, given the growing demand for safer and more

sustainable alternatives to synthetic drugs. Conventional treatments, such as

corticosteroids, are effective but can cause adverse effects with prolonged or

inappropriate use. These effects include skin atrophy, telangiectasias, and other

local or systemic complications, highlighting the need for bioactive compounds

with minimal toxicity [17]. Natural extracts, particularly those rich in

polyphenols and flavonoids, have demonstrated both antioxidant capacity and

anti-inflammatory properties [18, 19]. According to a collaborating research

group, four major compounds, vanillic acid, p-coumaric acid,

4-methylcatechol, and afzelin, were quantified among the 21 phenolic compounds

identified in CLE by LC-ESI-MS analysis. Their quantified contents were 0.431

Aging and skin inflammation are strongly influenced by the accumulation of

cellular ROS. Our analysis revealed that stimulated HK displayed markedly

elevated ROS accumulation. Nevertheless, CLE dose-dependently suppressed

intracellular ROS accumulation. A comparable reduction in ROS levels has also

been reported with pure compounds in cytokine-stimulated HK [15]. This finding

suggests a promising avenue for further investigation into their potential

anti-inflammatory properties. TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 are key cytokines that

regulate immune responses in inflamed skin. These molecules activate both innate

and adaptive immunity, playing a crucial role in promoting inflammation and

tissue remodeling [15]. The outcomes of the study demonstrated that CLE markedly

downregulated the mRNA expression levels of above cytokines in in vitro

RT-qPCR. These findings align with earlier reports describing the skin’s

anti-inflammatory mechanisms [26]. Furthermore, IL-6 and IL-8 facilitate the

immune cells recruitment to sites of inflammation [27, 28]. TNF-

The NF-

Similarly, preserving skin barrier integrity is crucial for controlling

inflammation, as it depends on HA production, the regulation of skin

moisturization-related proteins, and the activity of tight junction proteins,

factors that collectively support hydration, barrier stability, and immune

defense [32]. HA promotes hydration and tissue repair, while

moisturization-regulating proteins sustain epidermal homeostasis. Tight junction

proteins further strengthen barrier function, limiting antigen penetration and

immune hyperactivation [5, 33]. Nevertheless, pro-inflammatory cytokines,

primarily controlled through NF-

In in vivo studies, epithelial- and epidermal-derived innate cytokines are upregulated during innate immune responses, subsequently activating Th2-type adaptive immunity. This outcome enhances the release of type 2 cytokines, which in turn trigger skin inflammatory processes [35]. Notably, TSLP overexpression has been shown to drive type 2 inflammatory responses in mouse models, highlighting its pivotal role in the pathogenesis of skin inflammatory disorders [36]. This study highlights how TPA exposure provokes inflammation by stimulating crucial signaling cascades, resulting in elevated secretion of cytokines and chemokines. Such molecular events enhance immune cell recruitment and inflammatory activity, ultimately contributing to observable histopathological alterations [15]. The observed dose-dependent reduction in ear thickness, redness, and swelling can be attributed to the ability of CLE to modulate inflammatory mediators and suppress histopathological changes, including epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, epidermal thickness, inflammatory cell infiltration, and tissue damage. Molecular analyses of ear tissues using RT-qPCR and western blotting revealed inflammatory patterns in ear swelling in edema mice, which were comparable to those examined in the PC group. Furthermore, CLE treatment markedly reduced COX-2 and iNOS levels in the ear tissues, highlighting its anti-inflammatory potential. Taken together, these findings suggest that CLE possesses considerable pharmacological potential as a natural anti-inflammatory agent for the skin.

Although our data demonstrate a clear local reduction of inflammation by topical CLE in the TPA-induced ear edema model, further studies using systemic inflammation models and systemic administration of CLE are required to determine whether CLE also exerts systemic anti-inflammatory effects. These experiments are beyond the scope of the present study and are planned for future work. Moreover, while the current results are encouraging, certain limitations should be acknowledged. For the further development of CLE as a therapeutic candidate, future research should address long-term safety, investigate systemic and chronic effects in diverse animal models, and conduct clinical testing to confirm efficacy and safety in humans.

Overall, the data suggest that CLE has significant bioactive potential as a natural anti-inflammatory agent for the skin. In vivo, CLE significantly alleviated inflammatory symptoms and modulated molecular mechanisms in TPA-induced ear edema, demonstrating its efficacy in a skin inflammation model. These outcomes collectively highlighted the pharmacological usefulness of CLE as a natural, plant-derived anti-inflammatory agent, offering a promising alternative for managing skin inflammation.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AMKJ, and KGISK performed the research. KJ, JL, SL, and GA provided help and advice on the experiments. AMKJ, KGISK, KJ, JL, HMCBD, HMKR, LW, and JSK performed data analysis, curation, and visualization. SL, and GA provided funding and resources. SL, and GA were responsible for overall project supervision. AMKJ wrote the manuscript, and KGISK, SL, and GA contributed to its review and editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All in vivo experiments were conducted following the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of Chonnam National University, South Korea (permission number CNU IACUC-YS-2022-7), and followed the recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA).

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through the Technology Commercialization Support Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (122052032HD030).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. We confirmed that there is no conflict of interest between this study including its experimental conception and design, data collection, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, and the institution “French Korea Aromatics Co., Ltd.”. Given his role as the Guest Editor, Lei Wang had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Catarina Rosado.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL42888.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.