1 Department of Pathophysiology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Southwest Medical University, 646000 Luzhou, Sichuan, China

2 School of Stomatology, Southwest Medical University, 646000 Luzhou, Sichuan, China

3 State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in Chinese Medicine, Faculty of Chinese Medicine, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Histone post-translational modifications (HPTMs) have emerged as crucial epigenetic regulators in urological malignancies, including prostate, bladder, and renal cell carcinomas. This review systematically examines four key modifications—lactylation, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation—and their roles in carcinogenesis. These dynamic modifications, mediated by “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers”, influence chromatin structure and gene expression, thereby driving oncogenic processes such as metabolic reprogramming, immune evasion, and treatment resistance. The newly discovered lactylation modification links cellular metabolism to epigenetic regulation through lactate-derived histone marks, particularly in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, where it activates oncogenic pathways. Acetylation modifications, regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), modulate chromatin accessibility and are implicated in silencing cancer suppressors. Methylation patterns, controlled by histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and histone lysine demethylases (KDMs), demonstrate dual roles in gene regulation, with specific marks either promoting or suppressing carcinogenesis. Finally, phosphorylation dynamics affect critical cellular processes such as cell cycle progression and DNA repair. This review underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting these modifications, as evidenced by promising results with HDAC and Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitors. However, challenges persist in clinical translation, including off-target effects and the complexity of the cancer microenvironment. Future research should utilize multi-omics approaches to elucidate modification crosstalk and develop precision therapies. Overall, this comprehensive analysis provides valuable insights into the epigenetic mechanisms underlying urological cancers and highlights remaining knowledge gaps and therapeutic opportunities in this rapidly evolving field.

Keywords

- histone

- carcinoma

- renal cell

- prostate

- lactylation

- acetylation

- methylation

Epigenetics plays a pivotal role in determining cell fate, tissue differentiation, and disease progression by regulating gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1]. This field encompasses various epigenetic modifications, including those to DNA and histones, among others [2]. Histone modifications constitute a crucial component of epigenetic regulation. Their mechanisms, including lactylation, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, have been elucidated through interdisciplinary studies involving various omics analyses and epigenetics research [3, 4]. Histone lactylation, a newly identified epigenetic modification, involves the covalent attachment of lactyl groups to lysine residues on proteins. This modification is driven by lactate produced through cellular metabolism, which subsequently activates the transcription and expression of downstream genes, thereby promoting gene regulation [5]. Acetylation, a well-established epigenetic modification, influences gene transcription by regulating chromatin accessibility [6]. Methylation involves the addition of methyl groups to lysine and arginine residues on histone proteins, regulating chromatin structure and playing a vital role in preserving genomic stability, replication, and accessibility [7]. Finally, phosphorylation modulates the cell cycle and DNA repair through mechanisms such as charge neutralization or protein interactions [8, 9].

Research has demonstrated that dysregulation of those histone modifications is intimately linked to cancer progression, metastasis, and drug resistance. The mechanisms by which histone modifications drive malignant cancer progression, specifically through metabolic reprogramming, immune evasion, and oncogene activation, have attracted significant attention [10, 11, 12].

Urological cancers primarily include prostate cancer (PCa), bladder cancer, and

renal cell carcinoma. Epidemiological data from 2020 indicate that the

age-standardized incidence rate of PCa was 29.3 per 100,000, accounting for 7.3%

of all cancers. The incidence rates of bladder and kidney cancers were 5.6 per

100,000 and 4.4 per 100,000, respectively, correspondingly accounting for 3.0%

and 2.2% of all cancers. Notably, renal cell carcinoma comprises approximately

90% of all kidney cancer cases [13, 14, 15]. This distribution pattern demonstrated a

consistent trend from 1990 to 2019. Longitudinal comparative analysis further

reveals that compared to 1990, the incidence of PCa increased by 169.11%, while

kidney and bladder cancers increased by 154.78% and 123.34%, respectively.

These trends underscore a continuous increase in the global disease burden of

urological cancers. Given their high incidence, aggressiveness, and treatment

resistance, these cancers represent a significant global public health challenge

[16, 17]. Recent studies have unveiled a close relationship between urological

cancers and histone modification mechanisms. For instance, in clear cell renal

cell carcinoma (ccRCC), inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)

tumor suppressor gene leads to abnormal activation of the hypoxia-inducible

factor (HIF) pathway. This, in turn, results in enhanced glycolysis and lactate

accumulation. Lactate then induces histone H3K18 lactylation, which drives the

activation of the Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor

This review systematically integrates the most recent advancements in research concerning major histone modifications—lactylation, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation—within the context of urological cancers. Our aim was to clarify the molecular regulatory mechanisms of the various modification types and their pathological roles in cancer growth and metastasis. Furthermore, the review explores the clinical potential and challenges associated with therapeutic strategies targeting histone modifications, including histone deacetylase (HDAC) and Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitors.

Epigenetic dysregulation, characterized by changes such as DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, and histone post-translational modifications, is a hallmark of various human diseases, including cancers [20]. Studies have reported that histones play important roles in regulating chromosome structure, gene expression, and the cell cycle, as well as participating in DNA repair and maintaining chromosome stability. Histones are proteins found in the nuclei of eukaryotic cells that bind to DNA, regulating processes that involve the DNA template. They are essential components of chromosomes. Double-stranded DNA partially wraps around histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4) to form nucleosomes [21]. Additionally, the linker histone H1 binds to the DNA at either end of the nucleosome core particle, helping to stabilize the nucleosome structure and contributing to higher-order chromatin folding [22]. The structure and distribution of histones can affect chromosome structure and function, thereby influencing the biological characteristics of cells [23]. Therefore, histones within chromatin are typically not static; their N-terminal lysine residues are particularly prone to dynamic changes, known as post-translational modifications (PTMs) [24].

Histone post-translational modifications (HPTMs) are a primary epigenetic mechanism that regulates eukaryotic chromatin structure and gene expression [25]. These modifications directly regulate chromatin relaxation or compaction, thereby determining gene activation or silencing. This process is carried out by three classes of proteins, known as “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers”. Writers are involved in covalently adding specific chemical modification groups (e.g., acetyl, methyl, and phosphate groups) to amino acid residues. Erasers are responsible for removing specific modification groups, such as those facilitated by Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) and histone lysine demethylases (KDMs). Readers contain specific domains that recognize and bind to particular modification states on histones, for example, proteins containing bromodomains (BRD) [26, 27, 28]. The coordinated actions of these three components may ultimately result in various outcomes, including the covalent addition of functional groups or proteins, the enzymatic cleavage of regulatory subunits, or the breakdown of entire proteins. These outcomes alter the activity, stability, signaling, and cellular localization of histones, thereby enhancing the proteome’s functional diversity [29].

HPTMs can alter the conformation of histones and influence DNA-related processes such as replication, transcription, and repair, thereby controlling growth, tissue differentiation, cellular reactivity, and biological phenotypes without changing the underlying genetic sequence [30]. Different HPTM types, either individually or in combination, shape functional chromatin states. Proteins with specific effector functions selectively recognize these modifications to regulate gene expression and play a crucial role in preserving equilibrium [31]. The extensively studied modifications include acetylation and methylation of lysine residues, as well as phosphorylation and ubiquitination on serine/threonine residues [32]. Recently discovered histone modifications, including histone lactylation, crotonylation, and citrullination, have also shown significant clinical relevance [33, 34, 35]. Among these, the current focus in the field of epigenetics is primarily on histone lactylation, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation. Therefore, we will introduce the general mechanisms of these four modification types and their associations with urological cancers.

Histone lactylation, a recently identified epigenetic modification, is defined by the covalent attachment of a lactyl group to lysine residues on proteins. This unique functional modification relies on lactate produced by cellular metabolism as a substrate. It facilitates gene regulation by promoting the transcription and expression of downstream genes, thereby regulating various cellular biological functions [36]. The functional significance of histone lactylation has been demonstrated in diverse cellular processes; for instance, it plays a critical role in regulating immune cell function and polarization by directly activating transcription of key genes involved in immune response [36]. Lactylation sites have been discovered on core histones H3, H4, H2A, and H2B. Among these sites, H3K4la and H3K18la are the most common modification sites. These modifications can modulate diverse biological activities of cancer cells, including proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [37, 38]. Changes in these modification sites are strongly linked to cancer malignancy and affect patient prognosis; however, they also present new potential targets for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Recent research has increasingly focused on the role of histone lactylation in regulating gene expression and its contribution to cancer development. Histone lactylation can participate in cancer progression through various pathways, including driving oncogene expression. It is also closely linked to other types of epigenetic modifications in numerous malignancies [39, 40, 41, 42]. Histone lactylation strongly interacts with RNA modifications, and together they accelerate cancer progression. Yu et al. [40] and Xiong et al. [41] revealed that histone lactylation can induce overexpression of m6A modification enzymes, including methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3). Subsequently, METTL3 promotes JAK1 protein translation and STAT3 phosphorylation through the m6A-YTHDF1 axis, thereby enhancing the immunosuppressive capacity of Tumor-infiltrating Myeloid Cells (TIMs). METTL3 expression can be upregulated by lactate in the tumor microenvironment via H3K18 lactylation. Since sites in the zinc-finger domain are crucial for capturing the target RNA, their lactylation facilitates tumor progression. In pancreatic cancer, enhanced glycolysis results in elevated lactate production and histone H3K18 lactylation. H3K18la becomes enriched at the promoters of protein kinases TTK and BUB1B, promoting their transcription and driving the proliferation and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells [43]. Furthermore, histone lactylation can enhance the expression of genes that drive macrophage conversion from the M1 to the M2 phenotype, thereby facilitating cancer initiation and progression [44]. M1 macrophages exhibit anti-cancer activity, whereas M2 macrophages tend to boost cancer growth and immune evasion. By regulating the polarization state of macrophages, histone lactylation plays a pivotal role in the cancer microenvironment [45]. These observations suggest that lactylation regulates gene expression and significantly alters cellular functions and physiological processes.

Similar to other epigenetic modifications, histone lactylation is a dynamic and reversible process controlled by its writers and erasers. The full functionality of lactylation may also require the involvement of specific readers [5]. Writers and erasers, specifically lactylases and delactylases, are two enzyme classes with contrasting activities. These enzymes are responsible for adding or removing lactyl groups from lysine residues. The readers specifically identify these lactylations modification and mediate various cellular functions [46]. However, because the discovery of the lactylation process is relatively recent and the understanding of its potential molecular mechanisms is still incomplete, specific readers for lactylation remain unidentified.

Information on the writers, erasers, and readers of lactylation is limited. p300 is a confirmed writer for lactylation; it facilitates histone lactylation in the presence of lactate, thereby activating gene transcription [47]. CREB-Binding Protein (CBP) has also been recognized as a writer. These two enzymes may function independently or synergistically to achieve the lactylation of specific proteins [48]. Recent studies have reported that lysine acetyltransferases KAT2A, KAT5, KAT7, and KAT8 can act as lactylases to catalyze lysine lactylation in mammals and stimulate the expression of related genes [49, 50]. Research has confirmed that KAT2A can associate with lactyl-CoA through ACSS2 to act as a lactyltransferase, inducing lactylation of H3K14 and H3K18 [51]. Meanwhile, the lactylation activity of KAT8 enhances protein synthesis, contributing to colorectal carcinogenesis [52].

Scientists have found that most known delactylation enzymes exhibit interchangeability with deacetylation enzymes. Among these, Class I (HDAC1–3) and Class III (SIRT1–3) HDACs are common delactylases. Class I HDACs are highly effective erasers, possessing strong delactylation activity, with HDAC1 and HDAC3 exhibiting the strongest delactylation activity within this class [53, 54]. Related studies have shown that in vitro, HDAC1–3 can reduce the expression of H3K18la and H4K5la more than sirtuin 1-3 (SIRT1–3). In vivo experiments indicated that inhibitors of HDAC1–3 can increase the levels of ubiquitin ligase Lysine lactylation [54]. Therefore, HDAC1–3 inhibitors could act as potential therapeutic agents to treat diseases caused by lactylation. Within Class III HDACs, SIRT3 acts as an eraser for lactylation at the H4K16 site, preventing cancer cell proliferation by diminishing cyclin E2 activity [55]. Additionally, SIRT3 can specifically regulate gene transcription through H3K9la modulation, thereby impeding the progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells [56].

Histone lactylation plays a noteworthy role in the onset and progression of

various urological cancers. For instance, in PCa, evodiamine has been found to

inhibit the histone lactylation of HIF-1

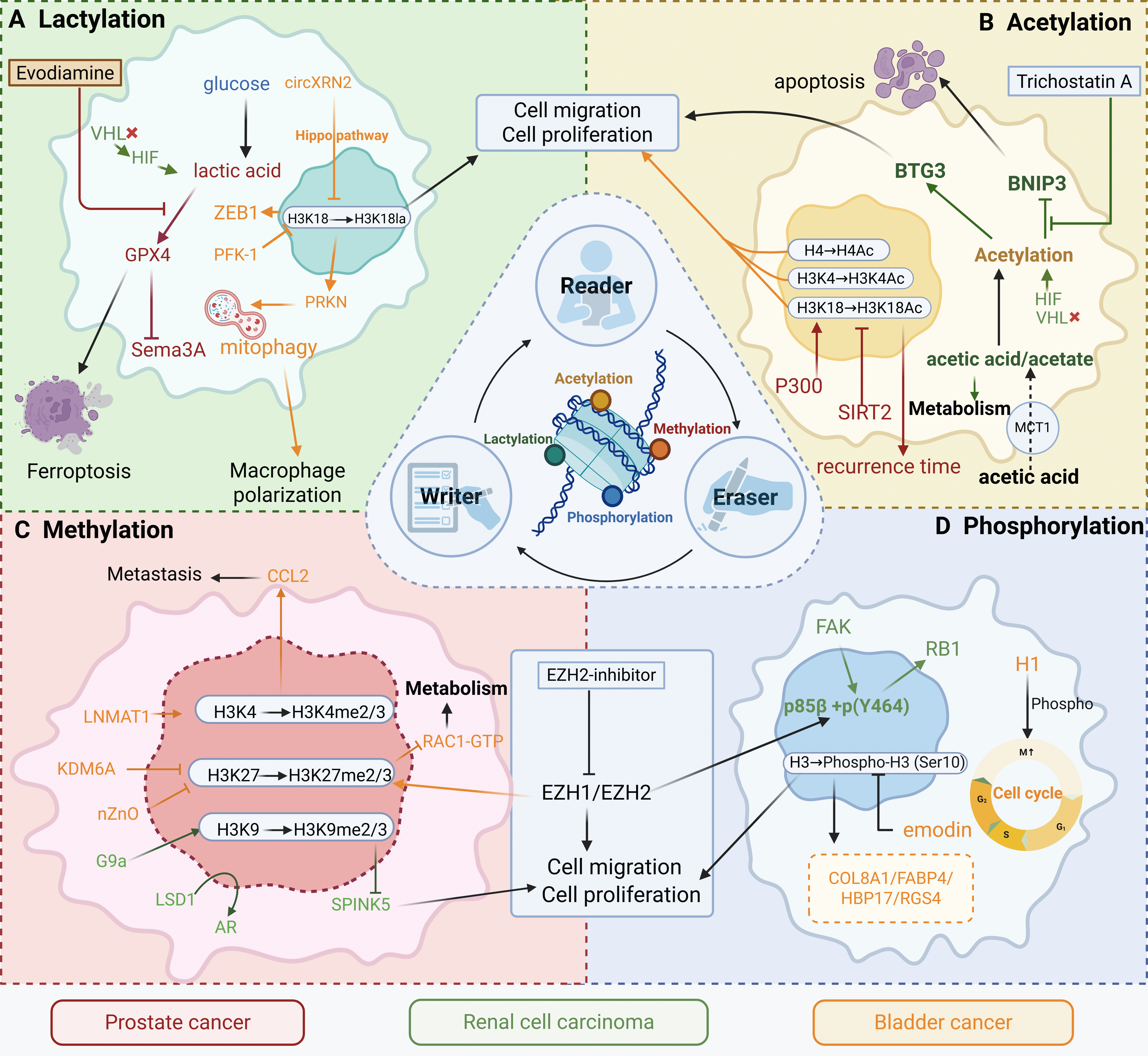

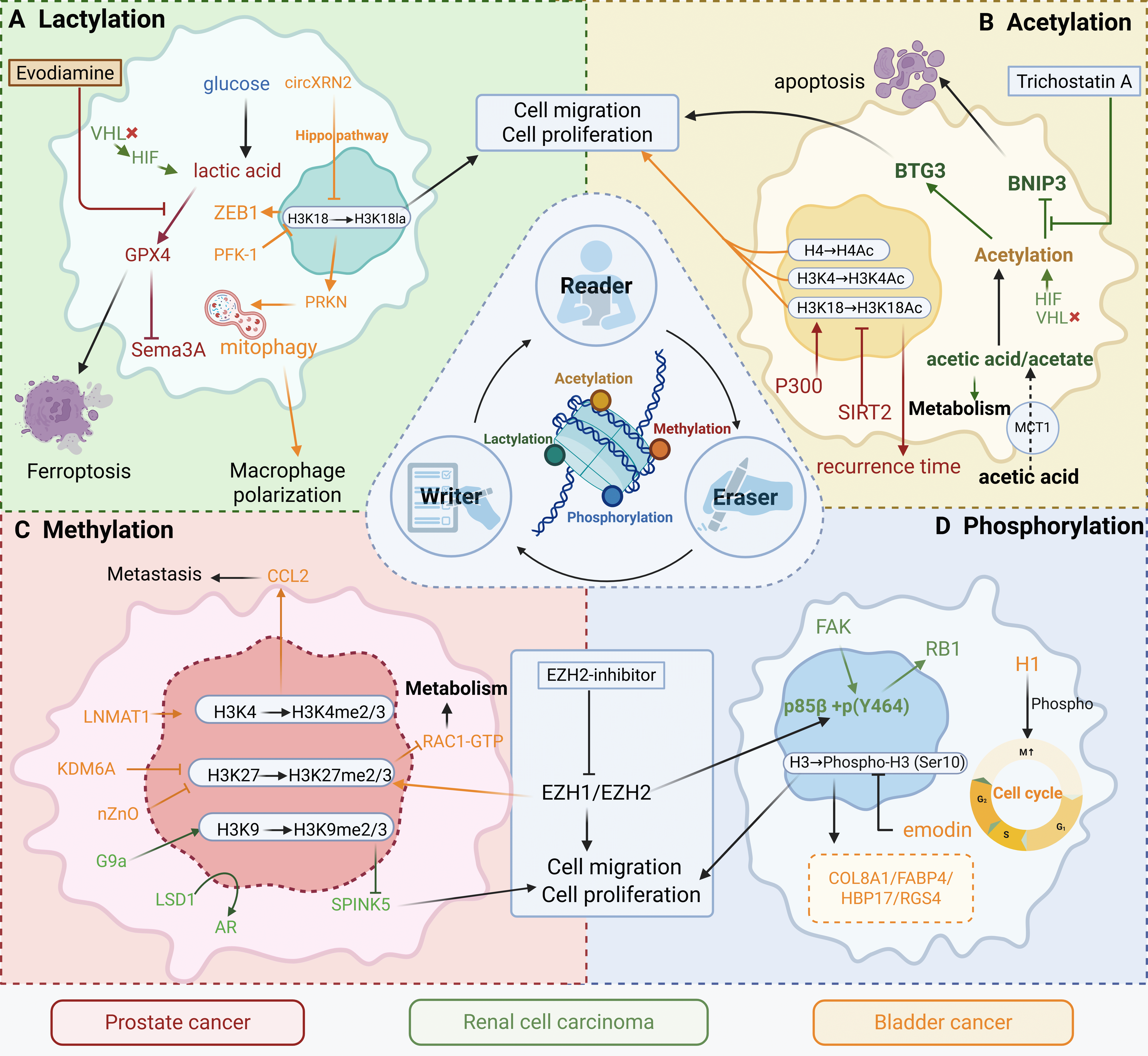

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Epigenetic remodeling integrates metabolic cues to drive

malignant progression in urological cancers. This schematic summarizes four key

classes of reversible epigenetic modifications—lactylation, acetylation,

methylation, and phosphorylation—and their functional interplay with metabolic

rewiring in prostate cancer (red), renal cell carcinoma (green), and bladder

cancer (orange/yellow). (A) Lactylation Module: Glucose-derived lactate

accumulation, driven by HIF signaling and metabolic enzymes (e.g., PFK-1, PRKN),

promotes histone lactylation (e.g., H3K18la), facilitating proliferation,

migration, macrophage polarization, and ferroptosis resistance. Evodiamine and

related compounds inhibit this pathway. (B) Acetylation Module: Acetate

metabolism (via MCT1) and P300-mediated acetylation (H3K4Ac/H3K18Ac) regulate

apoptosis, recurrence, and BNIP3/BTG3 signaling. Pharmacologic agents such as

trichostatin A can modulate this axis. (C) Methylation Module: Altered histone

methylation (H3K4me2/3, H3K27me2/3, H3K9me2/3), governed by G9a, EZH1/2, LSD1,

and KDM6A, enhances migration, proliferation, and metastasis via pathways such as

CCL2/Rac1. EZH2 inhibitors offer therapeutic potential in renal cell and

prostate cancers. (D) Phosphorylation Module: FAK and RB1 phosphorylation, along

with cell cycle–linked histone phosphorylation (H3S10p), activate oncogenic

programs that drive proliferation and invasion in bladder cancer (e.g., via

COL8A1, FABP4, HBP17, RGS4). Emodin has been shown to attenuate these effects.

VHL, von Hippel-Lindau; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; ZEB1, Zinc Finger E-Box

Binding Homeobox 1; PFK-1, Phosphofructokinase-1; GPX4, Glutathione Peroxidase 4;

PRKC, Protein Kinase C; BTG3, B-cell Translocation Gene 3; BINP3, BCL2/Adenovirus

E1B 19 kDa Interacting Protein 3; MCT1, monocarboxylate transporter 1; SIRT2,

Silent Information Regulator Two-related enzyme 2; CCL2, C-C Motif Chemokine

Ligand 2; LNMAT1, lymph node metastasis-associated transcript 1; KDM6A,

histone demethylase 6A; LSD1, Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1; AR, Androgen

receptor; SPINK5, Serine Peptidase Inhibitor, Kazal Type 5; EZH, Enhancer of

zeste homolog 2; FAK, Focal Adhesion Kinase; RB1, Retinoblastoma Protein 1; H1,

Histone H1; COL8A1, Collagen Type VIII Alpha 1 Chain; FABP4, Fatty Acid Binding

Protein 4; HBP17, Heparin-Binding Protein 17; RGS4, Regulator of G-protein

Signaling 4. The figure was created with

Scientific Image and Illustration Software

To summarize the above, histone lactylation plays a critical role in urological

cancer progression by regulating gene expression. Based on the pathways

described above, it is evident that there is a significant correlation between

lactate production, lactylation levels, and tumor cell behaviors, an association

verified in both bladder cancer and ccRCC. It is worth noting that although the

specific mode of action between HIF-1

These studies offer new insights into the metabolic and epigenetic regulation of urological cancers, suggesting that lactylation modifications could become important targets for future therapeutic strategies. Understanding lactylation’s role in tumor progression and immune evasion could help researchers develop new, targeted, and effective therapeutic approaches.

Histone acetylation is a vital post-translational modification widely present in eukaryotic cells, playing an essential role in regulating gene expression. This process typically occurs on lysine residues and is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), with acetyl-CoA serving as the acetyl group donor. This modification alters the interaction strength between histones and DNA, reducing chromatin compaction and facilitating easier access for transcription machinery to genes [6]. In addition to affecting the chromatin structure, acetylation regulates chromatin functions by recruiting non-histone reader proteins (e.g., BRD). These reader proteins can modulate various processes, including DNA repair, cell cycle advancement, and gene transcription. By serving as docking sites for these proteins, acetylated histones help orchestrate complex cellular events beyond transcriptional regulation [62, 63]. Acetylation is specifically regulated by the balance between HATs and HDACs. At the molecular level, acetylation regulates gene expression through diverse mechanisms: it serves as a key epigenetic mark defining active chromatin states, facilitates enhancer formation and function, directly modulates the activity of transcription factors and signaling proteins, and influences the accessibility of genes to the transcriptional machinery [64]. For example, acetylation sites on histone H3, such as H3K27ac, serve as epigenetic markers of active transcription regions. These sites are involved in the formation of super-enhancers, which further regulate the expression of cell-specific genes. This highlights the role of acetylation in fine-tuning gene expression and cellular identity [64]. Additionally, HATs, such as KAT6A, can acetylate SMAD3, enhancing its transcriptional activity and promoting cell proliferation and cancer metastasis [65]. Histone acetylation also plays a significant role in the cancer microenvironment, particularly in the cancer immune evasion process. Acetylation can modulate the activation of immune-associated genes, thereby modulating the interplay between cancer cells and the immune system [66].

Histone acetylation is essential for regulating cellular metabolism and physiological conditions. Acetylation reactions rely on the cell’s metabolic state, particularly the levels of acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA not only serves as a direct donor for acetylation reactions but also participates in metabolic pathways like fatty acid synthesis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, providing essential energy for the cell [62]. Consequently, histone acetylation is strongly associated with cellular metabolic activities and can contribute to the cell’s response to environmental changes and stress. For instance, in cancer cells, altered metabolic states may affect acetyl-CoA levels, thereby influencing histone acetylation and the expression of cancer-related genes. This association highlights the potential impact of metabolic regulation on epigenetic modifications and gene expression in disease contexts [67]. Acetylation further leverages its ability to regulate cellular metabolism by integrating and becoming a critical node in other cellular functions. For example, lactate, a metabolic byproduct, can accumulate within cells, altering metabolic pathways and activating HATs, thereby elevating histone acetylation levels. This increase in histone acetylation can regulate lipid metabolism, promoting cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [68]. Additionally, research has revealed that the SPHK2/S1P signaling axis is involved in the proliferation of smooth muscle cells and vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension by regulating the acetylation status of H3K9 [69]. This indicates that acetylation is both a controller of gene expression and an important participant in broader cellular functions and physiological processes. It is noteworthy that histone acetylation extends beyond the regulation of genes and metabolism, playing crucial roles in controlling various cellular processes. Research has shown that histone acetylation affects various biological functions of cells, including division, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. It interacts with other epigenetic modifications, like methylation and phosphorylation, to participate in the intricate cellular regulatory networks [70]. Therefore, histone acetylation is not only a significant focus in epigenetic research but also a crucial aspect of studying diseases like cancer. Recent studies have highlighted the important function of histone acetylation in cancer progression, prognosis, and treatment response [71].

Conversely, histone deacetylation is a reversible process catalyzed by HDACs. This reversibility allows cells to quickly respond to changes in internal and external signals by adjusting the dynamic balance between acetylation and deacetylation, thereby flexibly modulating gene expression and maintaining precise regulation through epigenetic mechanisms across a range of physiological and pathological processes [72]. For instance, the dynamic regulation of histone acetylation is essential at various stages of the cell cycle. Acetylation facilitates the recruitment of transcription factors and the activation of gene transcription, while deacetylation helps maintain gene silencing [73].

Based on a search of public information available at the https://clinicaltrials.gov database, current drug development related to histone modifications primarily focuses on acetylation and methylation. Research targeting these modifications has progressively advanced into clinical trials. This focus suggests that the field is still predominantly centered on these traditional histone modification pathways. Beyond the use of related drugs alone, clinical trials are increasingly investigating combinations of targeted therapies and epigenetic drugs. This approach aims to enhance the treatment precision of various diseases (Table 1, Ref. [74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90]).

| Drug | Combined with targeted therapy | Specific Actions | Act on cancers | Effectiveness | Current Progress |

| Chidamide [74] | Sintilimab |

Enhances CD8+ T cell infiltration, reverses immunosuppressive microenvironment | MSS/pMMR colorectal cancer | Triple group vs. double group: 18-week PFS rate 64.0% vs. 21.7% (p = 0.003), ORR, 44.0% vs. 13.0% (p = 0.027) | Phase II trial completed |

| Entinostat [75] | Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor | Inhibits HDAC, suppressed cancer proliferation | Abdominal neuroendocrine cancer | 4/5 cases showed stable disease, cancer growth rate reduced to 17–68% of pre-treatment levels | Phase II trial (early termination) |

| CC-486 + Romidepsin [76] | DNA methylation inhibitor and HDAC inhibitor | Synergistic epigenetic regulation | Advanced solid cancer | ORR 0% (0/12), disease stabilization rate 41.7% (5/12); significant reduction in LINE-1 methylation (p = 0.04) | Phase I trial completed |

| Azacitidine + Vorinostat [77] | DNA methylation inhibitor and HDAC inhibitor | An epigenetic combination to reverse drug resistance | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | No survival benefit (vs. standard chemotherapy); however, it may enhance sensitivity to subsequent chemotherapy | Phase II trial completed |

| Vorinostat + Sirolimus [78] | HDAC inhibitor an mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor | Dual pathway inhibition | Advanced solid cancer | Partial response: Hodgkin lymphoma (–78%), perivascular epithelioid cell cancer (–54%); stable disease: liver cancer and sarcoma | Phase I trial completed |

| Vorinostat + Lenalidomide [79] | HDAC inhibitor and an immunomodulator | Epigenetic regulation and immunotherapy | Multiple myeloma | No PFS/OS benefit (median PFS 34 vs. 40 months, p = 0.122), and poor tolerability (increased discontinuation rates) | Phase III trial failed |

| 5-Azacytidine + Phenylbutyrate [80] | DNA methylation inhibitor and HDAC activator | Synergistic epigenetic regulation | Advanced solid cancer | Low clinical benefit: 1 case SD (5 months), 26 cases PD | Phase I trial completed |

| Vorinostat + Sorafenib [81] | HDAC inhibitor and multi-kinase inhibitor | Epigenetic regulation and antiangiogenic combination | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Disease control rate 77% (10/13), 2 cases long-term stability ( |

Phase I trial terminated |

| Decitabine + Valproic Acid [82] | DNA methylation inhibitor and HDAC inhibitor | Synergistic demethylation and deacetylation | Non-small cell lung cancer | Fetal hemoglobin re-expression (7/7 cases); however, significant neurotoxicity (2 grade 3 cases) | Phase I trial terminated |

| Romidepsin [83] | Single drug (HDAC inhibitor) | Induces cancer cell apoptosis | Peripheral T-cell lymphoma | ORR 25% (33/130), median response duration of 28 months; similar efficacy across treatment lines ( |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved |

| Panobinostat [84] | Single drug (HDAC inhibitor) | Inhibits histone deacetylation | Metastatic melanoma | ORR 0% (0/15), disease stabilization rate 27% (4/15) | Phase II trial negative results |

| Vorinostat [85] | Single drug (HDAC inhibitor) | Regulates gene expression | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | ORR 29.7%, itch relief rate 32%; median response duration |

FDA approved |

| Decitabine + Panobinostat + Temozolomide [86] | Epigenetic therapy and chemotherapy | Overcomes epigenetic drug resistance | Metastatic melanoma | Disease control rate 27% (6/22), 1 case PR (–54%); no dose-limiting toxicity | Phase I trial completed |

| Vorinostat + Temozolomide [87] | HDAC inhibitors and alkylating agents | Synergistic epigenetic and chemotherapy combination | Pediatric brain/spinal cord cancer | Recommended dose: Vorinostat 300 mg/m2 + Temozolomide 150 mg/m2; increased histone H3 acetylation | Phase I dose determination |

| Vorinostat [88] | Single drug (HDAC inhibitor) | Regulates the epigenetic aging clock | Myeloproliferative neoplasm | Methylation age (MA) positively correlated with Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2) burden (r = 0.72); treatment brings MA closer to actual age | Phase II related analysis |

| CUDC-907 [89] | Single drug (HDAC/Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase(PI3K) dual inhibitor) | Dual blocking of epigenetic and signaling pathways | Lymphoma/multiple myeloma | ORR 14% (5/37), DLBCL subgroup ORR 56% (5/9); transformed follicular lymphoma ORR 60% (3/5) | Phase II recommended dose 60 mg |

| Panobinostat [90] | Single drug (HDAC inhibitor) | Reduces JAK2 mutation burden | Myelofibrosis | ORR 36% (8/22), median spleen reduction 34%, 1 case of complete molecular remission | Phase II trial completed |

Abnormal changes in histone acetylation are strongly linked to the initiation, progression, invasion, and drug resistance of urological cancers. Comprehending the underlying mechanisms of histone acetylation and its role in cancer could provide new targets and strategies for therapeutic intervention.

In ccRCC, an imbalance in histone acetylation is considered a significant cancer-driving mechanism. Studies have shown that HDACs are abnormally activated in ccRCC, contributing to the silencing of several cancer suppressor genes. For example, the BNIP3 gene is often underexpressed in renal cancer tissues, a phenomenon closely related to histone deacetylation. Experimental results indicate that histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as trichostatin A (TSA), can restore the downregulated expression of the BNIP3 gene. This restoration inhibits renal cancer cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis [91]. Consequently, restoring histone acetylation facilitates the reactivation of these tumor suppressor genes, which may also inhibit renal cancer growth by regulating pathways related to the cell cycle and apoptosis.

Additionally, histone acetylation is closely related to metabolic reprogramming in renal cancer. Renal cancer cells often exhibit metabolic alterations, such as increased lactic acid fermentation and upregulated lipid metabolism. Studies have found that the high expression of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) in ccRCC correlates with increased histone acetylation. MCT1 facilitates the transport of metabolic products like acetate, thereby promoting cellular energy metabolism, as well as cancer proliferation and migration [92]. The regulation of MCT1 is linked to the metabolic adaptability of cancer cells and can influence histone acetylation, thereby affecting the cancer’s invasive ability. Therefore, histone acetylation plays a significant role in the metabolic reprogramming of renal cancer, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic target.

The regulatory mechanisms of histone acetylation have also been extensively studied in other urological cancers. For instance, in kidney and bladder cancers, HDAC overexpression has been linked to malignant progression and drug resistance. The expression of the BTG3 cancer suppressor gene in renal cancer is influenced by histone modifications. Specifically, the removal of histone acetylation and the addition of methylation within the BTG3 gene can hamper its inhibitory effect on cancer cell growth [93]. Conversely, restoring the expression of BTG3, which is closely related to regulating histone acetylation, can suppress renal cancer cell proliferation. Thus, histone acetylation not only restores the activity of cancer suppressor genes like BTG3 but also impedes the malignant transformation of renal cancer cells by regulating cell cycle- and apoptosis-related pathways.

Similarly, studies have shown that acetylation levels in prostate and bladder cancers can serve as valuable biomarkers for cancer progression, aiding in the identification of high-risk patients. The dysregulation of histone acetylation fundamentally contributes to the eventual malignancy of cancers [94, 95]. These findings critically underscore the existence of specific histone acetylation patterns that hold prognostic significance. For instance, H3K18Ac/p300 in PCa was correlated with Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) level [94], while decreased H3K18Ac/H4Ac in muscle-invasive bladder cancer was linked to increased aggressiveness [95]. These are not merely descriptive observations; rather, they represent tumor-type-specific epigenetic signatures with direct prognostic relevance. Studied on acetylation modifications in urological tumors are presented in Fig. 1B.

Building upon the identification of promising targets (summarized in Table 2, Ref. [52, 55, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109]) and the rich tapestry of regulatory mechanisms uncovered by prior studies—including HDAC overexpression, tumor suppressor gene silencing, and distinct prognostic acetylation marks—a compelling mechanistic foundation for translating histone acetylation biology into clinical applications for urological cancers emerges. Current research consistently highlights the critical role of histone acetylation in the onset, advancement, and prognosis of urological tumors. Therefore, targeting relevant enzymes, such as HDACs and HATs, offers significant therapeutic potential.

| Modification | Target | Drug | Mechanism/Function | Associated Cancers | Therapeutic Potential | Therapeutic Goal | Experimental Outcome | Status | Evidence Level |

| Histone acetylation/deacetylation | HDAC Class I (HDAC1,2,3) | Entinostat | Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors, Inhibition of Treg Function and enhancement of Immune Checkpoint Response. | Bladder cancer | Overcoming resistance to immunotherapy | Enhancing the efficacy of Pembrolizumab | NCT03978624: Significant changes in the T-cell CD8 immune gene signature. | Ongoing (NCT03978624) | Phase 2 |

| Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Enhancing T cell responses | Restoring sensitivity to immunotherapy | NCT03024437: Objective Response Rate (ORR) of 21%. | Terminated (NCT03024437) | Phase 1/Phase 2 | ||||

| NCT03552380: Objective Response Rate (ORR) of 8.3%. | Terminated (NCT03552380) | Phase 2 | |||||||

| HDAC Class I, IIb (HDAC1–3,6,10) | Vorinostat | Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors, Reverse epigenetic silencing and enhance antigen expression. | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) | Enhancing radiosensitivity | Conversion from PSMA-low to PSMA-high | NCT06145633: PSMA conversion rate (ongoing). | Recruiting (NCT06145633) | Phase 2 | |

| Advanced renal cell carcinoma | Overcoming resistance to immunotherapy | Enhancing the activity of Pembrolizumab | NCT02619253: Objective Response Rate (ORR) of 14%, with a median Progression-Free Survival (PFS) of 3.8 months. | Completed (NCT02619253) | Phase 1 | ||||

| HDAC Class III (SIRT1) | N/A | Deacetylation of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) and downregulation of Fibrinogen Beta Chain (FGB) expression. | Renal cell carcinoma | Inhibition of tumorigenesis | Inhibition of the STAT3-FGB signaling axis | Inhibition of tumor proliferation to improve patient prognosis. | In vitro/vivo [96] | Preclinical | |

| N/A | Activation of the AMP-activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway. | Inhibition of tumor progression | Regulation of cellular energy metabolism | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, while promoting apoptosis | In vitro [97] | Preclinical | |||

| HDAC Class III (SIRT3) | N/A | Inhibition of Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIPK3)-mediated necroptosis. | Prostate cancer | Blocking innate immune evasion | Restoration of immune surveillance | Inhibition of macrophage and neutrophil recruitment, which promotes tumor progression. | In vitro [98] | Preclinical | |

| N/A | Regulation of mitochondrial metabolism. | Renal cell carcinoma | Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets | Suppression of tumor progression | High expression is associated with poor prognosis (increased grade, increased stage, decreased treatment response). | Clinical samples [99] | Translational | ||

| N/A | Regulation of mitochondrial metabolism. | Tumor suppressor factor | Prolongation of survival | Patients with high expression have significantly prolonged survival. | Clinical samples [100] | Translational | |||

| HDAC Class III (SIRT7) | N/A | Downregulation of Rho Family GTPase 3 (RND3) expression through the decrease of H3K18ac or the increase of H3K27me3. | Bladder cancer | Reversal of cisplatin resistance | Enhancement of chemotherapy sensitivity | Reduces cisplatin IC50 and inhibits tumor growth. | In vitro/vivo [101] | Preclinical | |

| N/A | Synergistic inhibition of E-cadherin with EZH2. | Inhibition of the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) process | Blocking metastasis | Knockdown promotes cell migration and invasion and upregulates EMT markers. | In vitro [102] | Preclinical | |||

| N/A | Drive metabolic stress adaptation. | Prostate cancer | Targeting Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) | Inhibition of proliferation | Promotes tumor growth through chromatin regulation. | Review [103] | Mechanistic insight | ||

| HDAC Class IV (HDAC11) | N/A | Core components of the BCYRN1/miR-939-3p/HDAC11 signaling axis. | Prostate cancer | Blocking lncRNA oncogenic pathways | Inhibition of tumor proliferation | Brain Cytoplasmic RNA 1 (BCYRN1) upregulation leads to increased HDAC11 expression, which results in enhanced cell proliferation, higher Gleason scores, and increased lymph node metastasis. | In vitro [104] | Preclinical | |

| N/A | Prognosis-related epigenetic regulatory factors. | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) | Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets | Prediction of survival outcomes | High Expression: Significantly associated with poor prognosis. | Clinical samples [105] | Translational | ||

| Lactylation/delactylation | E1A Binding Protein p300 (p300)/CREB Binding Protein (CBP) (histone lactyltransferase) | EP31670 | Epigenetic drugs targeting p300/CBP inhibit tumors by regulating gene expression. | Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), NUT carcinoma, Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia (CMML), Myelofibrosis | Targeting epigenetic dependencies in aggressive cancers with limited treatment options; potential synergistic effects in cancers relying on these pathways. | This Phase I open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation study will evaluate the safety of oral EP31670 in patients and determine its maximum tolerated dose. | Not reported. | Recruiting (NCT0548854) | Phase 1 |

| KAT8 (histone lactyltransferase) | N/A | Promotion of protein synthesis through Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 1 Alpha 2 (eEF1A2) lactylation drives colorectal cancer progression. | Colorectal cancer | Inhibition of lactylation may suppress tumor growth. | Inhibition of lactylation to block the synthesis of oncogenic proteins | Increased Glycolysis leads to lactate accumulation, → KAT8 catalyzes eEF1A2 lactylation, eEF1A2 activation results in increased protein synthesis, Oncogenic Signaling Pathway Activation: Activates pathways such as mTOR. | In vitro [52] | Preclinical | |

| KAT2A (histone lactyltransferase) | AUTX-703 | KAT2A inhibitors influence the epigenetic state of tumor cells by modulating this protein. | Relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) | Reversing abnormal gene expression in tumor cells through epigenetic regulation. | Evaluation of the drug’s safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy | Not reported. | Recruiting (NCT06846606) | Phase 1 | |

| SIRT3 (histone delactylase) | N/A | Specific removal of H4K16la modification. | General mechanisms | Regulation of gene transcription | Analysis of the biological function of Kla | Higher de-lactylation activity on H4K16la compared to other sirtuins; development of a p-H4K16laAlk probe to capture SIRT3. | In vitro [106] | Structural biology | |

| SIRT1/SIRT3 (histone delactylase) | N/A | Removal of histone/non-histone Kla modifications. | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) | Regulation of the glycolysis-epigenetics axis | Inhibition of the Warburg effect | Knockout leads to the accumulation of Kla substrates; PKM2-Kla modification regulates metabolic pathways and cell proliferation. | In vitro [55] | Proteomics | |

| Methylation/demethylation | EZH2 (lysine methyltransferase) | EZH2 inhibitors | Blocking some of the enzymes needed for cell growth. | Urothelial Carcinoma | Enhances anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab) efficacy by reversing immune silencing in tumors | To conduct a safety lead-in phase that identifies the safe recommended phase II dose for combination tazemetostat and pembrolizumab (MK-3475). | Not reported. | In vivo (NCT03854474) | Phase I/II clinical trial |

| Improve objective response rate (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS) | |||||||||

| Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) (arginine methyltransferase) | Flavokawain A (FKA) | Binding to the Y304/F580 sites of PRMT5. | Bladder cancer | Novel epigenetic targeted therapy | Inhibition of histone symmetric dimethylation | Blocking H2A/H4 methylation; in vitro proliferation inhibition with an IC50 of 8.2 µM; in vivo tumor volume reduction by 62%. | In vitro/vivo [107] | Preclinical | |

| LSD2 (Lysine-specific demethylase 2) | N/A | Transcriptional control, chromatin rearrangement, heterochromatin formation, growth factor signaling and somatic cell reprogramming. | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) | The presumed therapeutic target of ccRCC | The role of LSD2 and KDM5A demethylases in the pathogenesis of RCC | Silencing LSD2 and KDM5A suppresses cell proliferation, induces apoptosis, and causes corresponding cell cycle arrest. | Clinical samples [108] | Phase II clinical trial | |

| KDM5 (Jumonji C domain-containing demethylases) | CPI-455 | KDM1A and KDM5B both interact with the androgen receptor (AR) and promote androgen-regulated gene expression. | Prostate cancer | Individual pharmacologic inhibition of Lysine Demethylase 1A (KDM1A) and Lysine Demethylase 5 (KDM5) by namoline and CPI-455 respectively, impairs androgen regulated transcription | Develop new therapies targeting KDM1A and KDM5B for castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC); To find the feasibility of KDM5 in the treatment of prostate cancer | Genes upregulated with CPI-455 treatment are involved with the ribosome and in neurological disorders. | Experimental [109] | Preclinical | |

| Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation | VEGFR/PDGFR/RAF kinases | Sorafenib | Multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Prevention of metastatic recurrence | Prolongation of progression-free survival | Not reported. | Unknown (NCT01444807) | Phase 2 |

| VEGFR1/2/3 | Tivozanib | Highly selective VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. | Advanced renal cell carcinoma | Anti-angiogenesis | Improvement of objective response rate | Objective Response Rate (ORR) of 24.4%; 12-week Progression-Free Survival (PFS) rate: 64.5% for Tivozanib vs 37.9% for placebo (p = 0.006). | Completed (NCT00502307) | Phase 2 |

Specifically, exploiting these tumor-specific epigenetic signatures holds promise for: (1) developing refined diagnostic and prognostic biomarker panels (e.g., based on H3K18Ac levels); and (2) guiding the clinical application of targeted epigenetic therapies. Examples of such therapies include HDAC inhibitors, like vorinostat and romidepsin, which are used in clinical trials for prostate and urothelial cancers (NCT01075308 and NCT01174199), and potentially selective acetyltransferase modulators. Therefore, future research should prioritize exploring precise tumor classification and risk stratification based on integrated epigenetic markers. This must occur alongside validating the efficacy and optimizing the use of HDAC inhibitors and other epigenetic-modulating drugs in well-defined patient cohorts stratified by their acetylation profiles. Further in-depth research into the role of histone acetylation in urological tumors is essential to fully realizing its potential as a source of both biomarkers and therapeutic targets, ultimately providing a robust theoretical and practical basis for improving clinical outcomes.

Histone methylation is an important post-translational modification in epigenetics. By attaching methyl groups to specific lysine or arginine residues of histones, this process alters chromatin conformation and gene expression patterns [110]. This process is catalyzed by histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs), while its reversal, demethylation, is mediated by lysine demethylases (KDMs). The coordinated action of these enzymes determines gene expression states and influences cell fate decisions [7, 111]. Specifically, KMTs methylate specific histone sites (e.g., H3K27), leading to chromatin condensation and gene repression. Conversely, KMDs reverse this effect, promoting chromatin relaxation and gene activation. Crucially, the specific methylation site dictates the functional outcome. For instance, methylation at loci like H3K4 activates gene expression, while demethylases bidirectionally regulate transcriptional outcomes [7, 70]. Beyond regulating transcription factor activity, histone methylation modifications also collaborate with DNA methylation to maintain genomic integrity and stability [7]. The intricate interplay between histone and DNA methylation is mediated by specific reader proteins. Histone methylation readers include plant homeodomains (PHDs), while DNA methylation readers include SET- and RING-associated (SRA), CXXC-type zinc finger protein (CXXC), methyl-CpG binding (MBD), chromodomains, and bromo adjacent homology (BAH) domains [112]. Furthermore, histone methylation is closely linked to processes such as DNA repair and gene replication, playing critical roles in embryonic development, cell differentiation, and stress responses [113]. Dysregulation of histone methylation, particularly in diseases like cancer, frequently leads to aberrant gene expression and uncontrolled cell proliferation. For instance, mutations or imbalances in histone KMTs and KDMs are strongly associated with cancer progression in renal cell carcinoma [114]. SET domain bifurcated histone lysine methyltransferase 1 (SETDB1) exemplifies a histone methyltransferase crucial for gene silencing. This is achieved by attaching dimethyl or trimethyl groups to histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me2/3). This methylation is essential for silencing endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) and other genes, profoundly impacting cell fate decisions [115, 116].

Conversely, histone demethylation, primarily facilitated by demethylases like Lysine-specific Demethylase 2 (LSD2) (also known as KDM1B), plays a vital role in cellular functions. LSD2 not only removes methyl groups from histones but also participates in DNA methylation, cancer cell reprogramming, DNA damage repair, and other crucial cellular processes. LSD2 exhibits tissue-specific expression and is closely linked to the progression of various cancer types [117]. Additionally, Lysine Demethylase 5A (KDM5A), also known as Jumonji/ARID Domain-Containing Protein 1A (JARID1A), specifically recognizes the trimethylation state of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) through its Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain-containing Protein 1 (PHD1) domain. This recognition allows KDM5A to regulate the demethylation of target genes. KDM5A targets differentiation-dependent genes involved in cell cycle regulation. During cell differentiation, KDM5A has been shown to play a key role by directly regulating methylation marks on target genes such as BRD2, BRD8, and HOXA [118]. Overexpression of KDM5A is closely associated with cancer progression, as it can repress genes critical for controlling cell growth and differentiation [119].

Beyond the interplay between methyltransferases and demethylases, histone methylation modifications also interact with other epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, to collectively regulate gene expression. In PCa, elevated levels of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3, targets of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) complex, contribute to aberrant epigenetic regulation [120]. H3K27me3, a crucial transcriptional repression mark, is intimately linked to cancer invasiveness and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [121]. These studies have unveiled the complex mechanisms by which histone methylation regulates gene expression, providing new insights into epigenetic regulation. Lysine (K)-specific demethylase 6B (KDM6B), a stress-induced H3K27me3 demethylase, exhibits a context-dependent oncogenic or antitumor role in PCa. Specifically, increased KDM6B mRNA and protein levels have been observed in PCa, especially in metastatic PCa and Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [122].

In recent years, research on histone methylation has expanded beyond basic mechanistic exploration to include clinical applications, particularly its promise as a target for cancer therapy. Inhibitors of histone methylation enzymes, such as EZH2 inhibitors, have entered clinical trials and demonstrated promising results [123]. These studies have advanced our comprehension of the mechanisms governing histone methylation and provided novel insights for developing therapeutic strategies.

Histone methylation plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of urological cancers, particularly in bladder cancer and renal cell carcinoma.

In bladder cancer, research indicates that lymph node metastasis-associated transcript 1 (LNMAT1) is crucial for facilitating lymph node metastasis by upregulating the expression of C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (CCL2). This upregulation leads to the recruitment of cancer-associated macrophages (TAMs), which are known to promote cancer progression and metastasis. LNMAT1 influences bladder cancer progression through epigenetic mechanisms by increasing H3K4 trimethylation at the CCL2 gene locus. This modification enhances CCL2 transcription, thereby promoting lymph node metastasis [124, 125]. The role of histone demethylase 6A (KDM6A) in bladder cancer has also garnered considerable attention. Research shows that KDM6A restrains the migration and infiltration of bladder cancer cells by demethylating H3K27me2/3, which in turn suppresses the activity of RAC1, a protein involved in cell migration and metastasis. Loss of KDM6A function can lead to increased cancer cell invasiveness, contributing to aggressive cancer behavior. Restoring KDM6A function or using EZH2 inhibitors, which target the opposing methylation process, can effectively mitigate this metastatic effect [126]. Additionally, low doses of zinc oxide nanoparticles (nZnO) have demonstrated anticancer effects in bladder cancer. Research indicates that nZnO can alter the methylation state of H3K27 in bladder cancer cells, thereby inhibiting cell migration and invasion. This effect is independent of oxidative stress or DNA damage [127].

Histone methylation also plays a crucial role in renal cell carcinoma. Studies have shown that H3K27 methylation is strongly linked to cancer staging and recurrence risk in kidney cancer. Specifically, low levels of H3K27me3 are linked to higher Fuhrman grades and increased cancer aggressiveness. Additionally, low H3K27me3 levels correlate with poorer progression-free survival [128]. The function of the histone demethylase LSD1 in renal cancer has also been investigated. LSD1 affects renal cancer progression by regulating the transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor (AR). LSD1 knockdown reduces the expression levels of AR target genes, thereby hindering the proliferation and migration of renal cancer cells. Moreover, the combination of LSD1 inhibitors, such as pargyline, and AR inhibitors can remarkably suppress renal cancer cell proliferation [129].

The role of G9a, a histone methyltransferase that catalyzes the dimethylation of H3K9, in kidney cancer therapy has garnered significant attention. Research has found that G9a facilitates the onset and advancement of renal cancer by methylating H3K9 at the SPINK5 gene locus, thereby suppressing its expression. Specific inhibition of G9a was shown to significantly suppress the growth, migration, and infiltration of renal cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. These findings imply that targeting G9a may represent a promising new treatment strategy for renal cancer [130]. Studies on methylation modifications in urological cancers are shown in Fig. 1C.

To summarize the above, dysregulation of histone methylation (H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9me2) and their modifying enzymes (KDM6A, LSD1, G9a) constitute key epigenetic driving factors in urological cancers. By aberrantly regulating the expression of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, these dysregulations promote malignant tumor behaviors (proliferation, invasion, and metastasis) and serve as important prognostic markers and potential therapeutic targets.

Histone phosphorylation refers to the transfer of phosphate groups by protein kinases from ATP to specific amino acid residues on histones, typically at their N-terminal tails. This modification predominantly occurs on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues [131]. As a crucial post-translational modification, histone phosphorylation plays a vital regulatory role in chromatin dynamics and various core cellular functions, including apoptosis, chromatin remodeling, DNA damage repair, transcriptional activation, and mitosis. The dynamic addition and removal of phosphate groups on histones are orchestrated by specific enzymes: histone kinases of the protein kinase (PK) family are responsible for adding phosphate groups to tyrosine, serine, or threonine residues, while histone phosphatases of the protein phosphatase (PP) family are responsible for removing them. Two primary mechanisms affecting chromosome structure and function have been identified [132]. The first involves the neutralization of the histones’ positive charge by negatively charged phosphate groups, which decreases the affinity between DNA and histones, thereby promoting chromatin relaxation. The second mechanism involves the creation of recognition surfaces by phosphorylation. These can interact with protein recognition modules, facilitating engagement with specific protein complexes. These mechanisms collectively enable histone phosphorylation to flexibly regulate chromatin structure and recruit specific effector proteins, mediating a diverse range of biological functions whose effects can vary depending on the context and the proteins involved.

Many histone phosphorylation events are particularly prominent during meiosis and mitosis in most eukaryotes, including yeast, plants, and animals. These and other modifications play roles in gene transcription, DNA repair, apoptosis, and chromosome condensation. Key examples of histone phosphorylation events include H3S10ph, H3T3ph, and H2AT120ph [133]. For instance, Vega FM et al. [134] found that VRK serine/threonine kinase 1 (VRK1) directly targets nucleosome phosphorylation, specifically H2AT120ph, and can also phosphorylate various transcription factors, including Tumor Protein p53 (p53), Jun Proto-Oncogene (c-Jun), Activating Transcription Factor 2 (ATF2), and Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP) Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB), thereby influencing gene transcription. Komar and Juszczynski [135] discovered that in healthy cells, H2AT120ph governs the hierarchical arrangement of other histone modifications, which are involved in forming protein-binding scaffolds, regulating transcription, inhibiting repressive epigenetic signals, and safeguarding gene regions from heterochromatin spread. Furthermore, McIntosh [136] highlighted the crucial role of H3S10ph in ensuring prompt condensation and separation of chromosomes, which is essential for accurate genetic material transmission during cell division.

Histone phosphorylation modifications play a significant role in the onset and progression of urological cancers. They are primarily involved in processes such as cell growth, differentiation, and programmed cell death. Additionally, certain histone phosphorylation marks can serve as biomarkers for specific cancers, aiding in assessing their progression and prognosis. Notably, research on the development and progression of bladder cancers is quite advanced.

Studies have found elevated levels of phospho-histone H3 at serine 10 (pH3Ser10) in bladder cancer tissues. Therapeutic agents, such as emodin, can inhibit histone H3 (serine 10; H3S10) phosphorylation while simultaneously promoting H3K27me3 to suppress cancer growth [137]. Furthermore, the phosphorylation level of histone H1 significantly increases throughout the progression of bladder cancer [138]. Analysis using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has demonstrated that the phosphorylation level of H1 gradually increases from normal bladder epithelial cells to low-grade bladder cancer, and subsequently to high-grade bladder cancer cells. This change in phosphorylation levels is strongly linked to cell cycle progression. Specifically, the observed increase in phosphorylation levels during the transition from the G0/G1 phase to the M phase suggests its potential as a proliferation marker [138].

In ccRCC, studies have revealed that FK506 Binding Protein 10 (FKBP10)

promotes metabolic reprogramming in cancer by facilitating the phosphorylation

of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) at the tyrosine 10 site. This, in turn,

enhances cancer cell proliferation and metastasis, as well as the Warburg effect,

which supports the metabolic demands of cancer cells. The interaction between

FKBP10 and LDHA is crucial for regulating this process. Additionally, FKBP10

modulates sensitivity to HIF2

To summarize the above, these studies indicate that histone phosphorylation

modifications are not only important epigenetic markers in urological cancers but

also present potential therapeutic targets. By regulating these phosphorylation

events, it may be possible to develop novel therapeutic strategies for treating

urological cancers. For instance, in bladder cancer, pH3Ser10 and H1

phosphorylation drive proliferation and cell cycle progression, while in ccRCC,

the FKBP10/LDHA-Y10 axis enhances the Warburg effect via metabolic-epigenetic

crosstalk, influencing HIF2

Histone modifications, as core mechanisms of epigenetic regulation, play complex and crucial roles in the onset, progression, and treatment resistance of urological cancers. This review systematically examined the molecular mechanisms and functions of four modification types—lactylation, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation—in urological cancers. It revealed the dynamic and plastic nature of the epigenetic regulatory network while highlighting knowledge gaps in current research.

Histone modifications do not exist in isolation; rather, they regulate gene expression through metabolic reprogramming, enzyme activity interactions, and chromatin state alterations. To illustrate this, we present two examples:

① Metabolic Coupling of Lactylation and Acetylation: Lactylation relies

on lactate, produced through glycolysis, as a substrate, while acetylation is

regulated by acetyl-CoA levels. In ccRCC, VHL inactivation activates the HIF

pathway, enhancing both glycolysis (lactate production) and acetyl-CoA synthesis.

Notably, p300 functions as a shared writer enzyme for both histone lactylation

(H3K18la) and acetylation (H3K18ac). This suggests an enzymatic hub that

integrates metabolic signals into chromatin regulation. This dual activity

implies that elevated p300 activity under hypoxic and glycolytic conditions could

synchronize lactylation and acetylation at promoters of oncogenes like

PDGFR

② Functional Antagonism of Methylation and Phosphorylation: In bladder cancer, spatiotemporal distribution differences between H3K4me3 (a methylation mark) and H3S10ph (a phosphorylation mark) may determine the “promote/inhibit” state of gene transcription. For example, LNMAT1 can inhabit H3K4me3 to activate CCL2 expression, while H3S10ph may antagonize this process through chromatin compaction. This suggests that the dynamic balance between these modifications influences the metastatic potential of cancers [124, 135].

These interactions highlight the complexity of the metabolism-epigenetics network. Current research often focuses on changes in cancer mechanisms driven by single modifications. However, the efficacy of targeted therapies aimed at single modifications may be limited by compensatory mechanisms and could even lead to the emergence of resistance. Multi-omics technologies, such as ChIP-seq combined with metabolomics, should be utilized in future research to unravel the spatiotemporal interaction patterns among histone modification types.

The intricate roles of histone modifications in urological cancers underscore their potential as therapeutic targets. While clinical trials have primarily focused on HDAC and EZH2 inhibitors (Table 1), emerging research highlights additional promising targets across the lactylation, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation pathways. Table 2 summarizes key molecular targets, their mechanisms, and associated cancers, providing a roadmap for future precision therapies. For instance, in bladder cancer, HDAC1–3 overexpression correlates with tumor suppressor silencing and chemoresistance [16], making isoform-specific HDAC inhibition a strategic focus. Similarly, lactylation writers (e.g., p300, CBP, KAT2A) and erasers (e.g., HDAC3, SIRT3) offer novel avenues, particularly in ccRCC and PCa, where metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk drives progression [18, 19, 57]. In methylation, KDM6A loss promotes bladder cancer invasiveness [126], while EZH2/G9a inhibitors show efficacy in renal cancer [130]. Phosphorylation targets like H3S10ph and LDHA at tyrosine 10 site regulate cell cycle and metabolic reprogramming in bladder and kidney cancers [137, 138, 139, 140]. Future efforts should prioritize developing isoform-specific inhibitors and combinatorial regimens targeting these nodes to overcome microenvironment-driven resistance.

Dysregulation of histone-modifying enzymes creates targetable vulnerabilities in urological cancers, particularly in bladder cancer and renal cell carcinoma.

In bladder cancer, AT-rich Interaction Domain 1A (ARID1A) inactivation (

In renal cell carcinoma, metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk defines unique

therapeutic windows. The oncometabolite L-2-hydroxyglutarate (L-2HG) accumulates

independently of IDH mutations, inhibiting TET enzymes and reducing global 5hmC

levels. This epigenetic silencing can be reversed by restoring L-2HG

dehydrogenase (L2HGDH), suppressing tumor growth [143]. VHL-deficient ccRCC

further exploits the FKBP10-LDHA axis. FKBP10 stabilizes phosphorylated LDHA,

enhancing glycolysis and histone lactylation. Crucially, FKBP10 inhibition

disrupts the HIF-driven metabolic loop and sensitizes tumors to HIF2

Metabolic rewiring in renal cell carcinoma also intersects with immune evasion. Glutamine overexpression and lipid efflux create immunosuppressive niches, rendering KDM6A- or PBRM1-mutant tumors susceptible to glutaminase inhibitors, which, together with PD-1 blockade, reinvigorate CD8+ T cells [144, 145]. The collagen modifier P4HA1, overexpressed in ccRCC, correlates with immune infiltration and checkpoint markers (e.g., PD-L1), nominating it as a candidate for immunotherapy-potentiating strategies [146].

Collectively, epigenetic lesions (e.g., ARID1A, KDM6A, SPINT2) and metabolite-driven dysregulation (L-2HG, histone lactylation) expose context-specific dependencies across urological malignancies. Targeting these nodes—via enzyme inhibitors, epigenetic modulators, or immunometabolic combinations—exploits synthetic lethality and may overcome resistance to conventional therapies.

Despite the promising efficacy of targeted therapies, including HDAC and EZH2

inhibitors, against histone modifications in basic research, their clinical

translation faces multiple challenges. Existing inhibitors, such as TSA and SAHA,

often target multiple classes of HDACs, which may disrupt the epigenetic

homeostasis of normal cells, resulting in adverse effects like bone marrow

suppression and cardiotoxicity. The development of inhibitors for novel

modifications, such as lactylation, remains underexplored. It is crucial to

prioritize the identification of highly specific targets among writer or eraser

enzymes, such as KAT2A and HDAC3, to minimize off-target effects and improve

therapeutic specificity. Additionally, the immunosuppressive microenvironment of

urological cancers can potentially weaken the effects of epigenetic therapies.

For instance, in bladder cancer, histone lactylation can promote M2 macrophage

polarization through PRKN-mediated mitophagy. M2 macrophages then secrete IL-10

or TGF-

These challenges highlight the individualized and comprehensive requirements of epigenetic therapies. In the future, it will be necessary to employ more diverse epigenetic research methods to uncover systematic and consistent epigenetic patterns that can refine target research. It will also be important to integrate various conditions and explore drugs targeting the same or multiple histone modification targets across different patient scenarios. This approach addresses the variability in therapeutic efficacy due to individual patient circumstances that affect the response to epigenetic-related drugs.

First, this study provides an overview of four histone modification types that are relatively well-studied in the context of urological cancers. Given the diverse types of histone modifications, we focused on these four due to the depth of current research. However, research on other modification types is equally important and should not be underestimated. Second, many conclusions were drawn from cell or animal models, as validations in large-scale clinical cohorts are lacking. Finally, the analysis of interactions between modifications often relies on indirect evidence, requiring further validation through techniques such as CRISPR screening or molecular dynamics simulations.

Histone post-translational modifications—lactylation, acetylation,

methylation, and phosphorylation—stand as central epigenetic regulators in the

pathogenesis and progression of urological cancers. This review synthesized

evidence demonstrating how these dynamic modifications rewire oncogenic

metabolism, silence tumor suppressors, drive immune evasion, and fuel treatment

resistance in prostate, bladder, and renal cell carcinomas. The newly discovered

lactylation modification, driven by glycolytic flux, exemplifies the critical

intersection between cellular metabolism and epigenetic reprogramming,

particularly in VHL-deficient renal cancers, where it amplifies PDGFR

Moving forward, integrating multi-omics approaches to decode modification crosstalk, developing modification-specific biomarkers for patient stratification, and designing combinatorial regimens that couple epigenetic drugs with immunotherapy or metabolic inhibitors will be essential directions to investigate. Such efforts will transform our understanding of the metabolism-epigenetics nexus and propel targeted epigenetic interventions toward clinical reality in urological oncology.

AR, Androgen receptor; BRD, Bromodomains; HDACs 1–3, Class I HDACs; SIRT1–3, Class III HDACs; ccRCC, Clear cell renal cell carcinoma; CBP, CREB-Binding Protein; CRPC, Castration-resistant prostate cancer; DML, Demethylzeylasteral; ERVs, Endogenous retroviruses; EZH2, Enhancer of zeste homolog 2; HATs, Histone acetyltransferases; HDACs, Histone deacetylases; KDMs, Histone lysine demethylases; KMTs, Histone lysine methyltransferases; HPTMs, Histone post-translational modifications; HIF, Hypoxia-inducible factor; LDHA, Lactate dehydrogenase A; LC-MS, Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; LNMAT1, Lymph node metastasis-associated transcript 1; METTL3, Methyltransferase-like 3; MCT1, Monocarboxylate transporter 1; NCCR, National Central Cancer Registry; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; PER1, Period circadian regulator 1; PTMs, Post-translational modifications; PCa, Prostate cancer; PK, Protein kinases; PP, Protein phosphatases; PSA, Prostate-specific antigen; SETDB1, SET domain bifurcated histone lysine methyltransferase 1; TCA, Tricarboxylic acid; TSA, Trichostatin A; TAMs, Tumor-associated macrophages; TIMs, Tumor-infiltrating Myeloid Cells; VHL, Von Hippel-Lindau; YTHDF2, YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein F2; nZnO, Zinc oxide nanoparticles.

BZ and YW designed the research study. FL, LH and MY performed the research. JC and YH provided help and advice about figure and table. BZ and WM analyzed the data. BZ, FL and LH wrote the manuscript. LH made tables and searched references. LH and YW have primarily been responsible for revising the manuscript and providing new insights. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all individuals and organizations who supported and assisted us throughout this research. In conclusion, we extend our thanks to everyone who has supported and assisted us along the way. Without your support, this research would not have been possible.

This research was funded by the Southwest Medical University (2024ZKY105) to B. Z. And this research was funded by Southwest Medical University 2023 Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (202310632032).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used WeMust-GPT in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.