1 College of Life Sciences, Northwest Normal University, 730070 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Cell Biology, Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, CAS, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 200031 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The role of macrophages has transcended the traditional binary framework of M1/M2 polarization, emerging as “tissue microenvironment engineers” that dynamically govern organismal homeostasis and disease progression. Under physiological conditions, they maintain balance through phagocytic clearance, metabolic regulation (e.g., lipid and iron metabolism), and tissue-specific functions (such as hepatic detoxification by Kupffer cells and intestinal microbiota sensing), all meticulously orchestrated by epigenetic mechanisms and neuro-immune crosstalk. In pathological states, their functional aberrations precipitate chronic inflammation, fibrosis, metabolic disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. Notably, this plasticity is most pronounced within the tumor microenvironment (TME): tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) polarize toward a protumoral phenotype under conditions of low pH and high reactive oxygen species (ROS). They promote angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), suppress immunity through interleukin-10 (IL-10)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and facilitate tumor invasion by degrading the extracellular matrix, ultimately fostering an immune-evasive niche. Novel intervention strategies targeting TAMs in the TME have shown remarkable efficacy: CRISPR-Cas9 spatiotemporal editing corrects aberrant gene expression; pH/ROS-responsive nanoparticles reprogram TAMs to an antitumoral phenotype; chimeric antigen receptor-macrophage (CAR-M) 2.0 enhances antitumor immunity through programmed death-1 (PD-1) blockade and IL-12 secretion; and microbial metabolites like butyrate induce polarization toward an antitumor phenotype. Despite persisting challenges—including the functional compensation mechanisms between tissue-resident and monocyte-derived macrophages, and obstacles to clinical translation—the macrophage-centered strategy of “microenvironmental regulation via cellular engineering” still holds revolutionary promise for the treatment of tumors and other diseases.

Keywords

- macrophages

- cell polarity

- tumor microenvironment

- epigenetics

- immunotherapy

- receptors

- chimeric antigen

- microbiome

- inflammation

- fibrosis

As a key member of the innate immune system, macrophages have long been regarded as the “first line of defense” for the body to resist pathogen invasion. Classical immunology theories emphasize their phagocytic and bactericidal functions in the inflammatory response, and classify macrophages into two polarization states: pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. However, with the rapid development of single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and in vivo imaging technologies, the functional complexity of macrophages has been gradually revealed [7, 8, 9]. The latest research shows that macrophages are not only the executors of the immune response but also “tissue niche engineers”. Through the secretion of metabolites and direct cell-cell contact, they dynamically regulate the homeostasis of the tissue microenvironment [7, 10, 11, 12].

The origin of macrophages has always been a research hotspot in the field of immunology. The early view was that macrophages in adult tissues mainly originated from monocytes differentiated from bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells [13, 14, 15]. However, in recent years, single-cell sequencing technology has revealed the long-term self-maintenance ability of embryonic-derived macrophages in adulthood. For example, in the heart, CX3CR1 macrophages can be traced back to the progenitor cells derived from the yolk sac in the embryonic period. They maintain a stable number through local proliferation in adulthood, independent of the bone marrow monocyte replenishment pathway [16, 17]. The discovery of these embryonic-origin macrophages has subverted the traditional understanding and provided a new perspective for understanding the tissue-specific functions of macrophages.

Macrophages play a core role in the regulation of tissue homeostasis [11, 18, 19, 20] (Table 1, Ref. [11, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87]). On the one hand, their functional plasticity endows them with the ability to respond to complex environmental changes. For example, the phenomenon of “trained immunity” shows that macrophages can, through epigenetic memory and metabolic reprogramming, produce a stronger response to a secondary stimulus after the first exposure to a pathogen or inflammatory stimulus [88, 89]. This plasticity is particularly prominent in the tumor microenvironment, where tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) undergo phenotypic switching according to signals from the tumor microenvironment, transforming from an anti-tumor active state to a phenotype that promotes tumor growth to adapt to the needs of tumor development [90, 91]. On the other hand, macrophages participate in the regulation of systemic homeostasis by constructing a cross-tissue network. Taking the gut-brain axis as an example, gut macrophages sense signals from the microbiota, secrete cytokines to regulate the permeability of the blood-brain barrier and the activity of microglia, and affect the functions of the nervous system [92, 93, 94, 95, 96]. In the tumor microenvironment, macrophages also form intricate networks with other cells. They interact with tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and more, and regulate the homeostasis of the tumor microenvironment through the secretion of cytokines, growth factors, and other substances, thereby influencing tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. For example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secreted by TAMs can promote tumor angiogenesis, providing nutrients and oxygen for tumor cells while also serving as a channel for tumor cell metastasis. Additionally, TAMs can secrete immunosuppressive factors such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), which inhibit the activity of immune cells, create an immunosuppressive microenvironment conducive to tumor cell growth, and disrupt the immune homeostasis of the body [97, 98, 99, 100].

| Category | Physiological role | Disease association | Key molecules/pathways | Intervention strategies | Recourse |

| Immune surveillance | Pathogen/apoptotic cell clearance | Chronic inflammation, tumor immune evasion | TNF-α/IL-1β, CSF1R | CAR-M, anti-cytokine targeting | [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53] |

| Metabolic regulation | Lipid/iron homeostasis | Atherosclerosis, NAFLD | oxLDL, FABP4, TfR1 | Metabolic reprogramming drugs | [11, 53, 54, 55, 56] |

| Tissue repair | Angiogenesis, ECM remodeling | Fibrosis (lung/liver/kidney) | TGF-β, PDGF, YAP | Targeting pro-fibrotic subsets | [53, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74] |

| Neural regulation | Synaptic pruning (microglia) | Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s | TREM2, APOE4, mtDNA-STING | TREM2 agonists, mitophagy modulators | [53, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83] |

| Aging-Related | Tissue renewal | Senile pulmonary fibrosis, chronic inflammation | p16INK4A, DNA methylation dysregulation | Senolytics, epigenetic modulators | [84, 85, 86, 87] |

TNF-

In response to the abnormal regulation of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment, a variety of innovative intervention strategies have been developed to reshape homeostasis. In terms of precision targeting technologies, spatiotemporally specific gene editing technology can correct the abnormal gene expression of TAMs through the CRISPR-Cas9 system, reactivating their anti-tumor activity [101, 102]; pH/reactive oxygen species (ROS) dual-sensitive nanocarriers can respond to the characteristics of the tumor microenvironment to release loaded substances, inducing the reprogramming of TAMs into tumor-suppressive phenotypes [103, 104, 105]. In cell engineering therapies, chimeric antigen receptor-macrophage (CAR-M) 2.0 is equipped with dual functional modules of programmed death-1 (PD-1) blockade and Interleukin-12 (IL-12) secretion, enabling precise recognition of tumor antigens, alleviation of immunosuppression, and activation of the immune system [106]; induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-CAR macrophage technology utilizes the properties of induced pluripotent stem cells to generate large quantities of macrophages with specific antigen recognition capabilities, addressing the issue of limited sources of traditional macrophages [107, 108]. In microbiome intervention strategies, microbiota metabolites such as butyrate can promote the polarization of macrophages toward anti-tumor phenotypes by regulating gene expression; phage-directed editing technology can precisely eliminate abnormal macrophages infected with pathogens and restore their normal functions [109]. These intervention strategies target macrophages in the tumor microenvironment from different perspectives, aiming to break the imbalanced state of tumor immune escape and restore the body’s immune surveillance homeostasis against tumors.

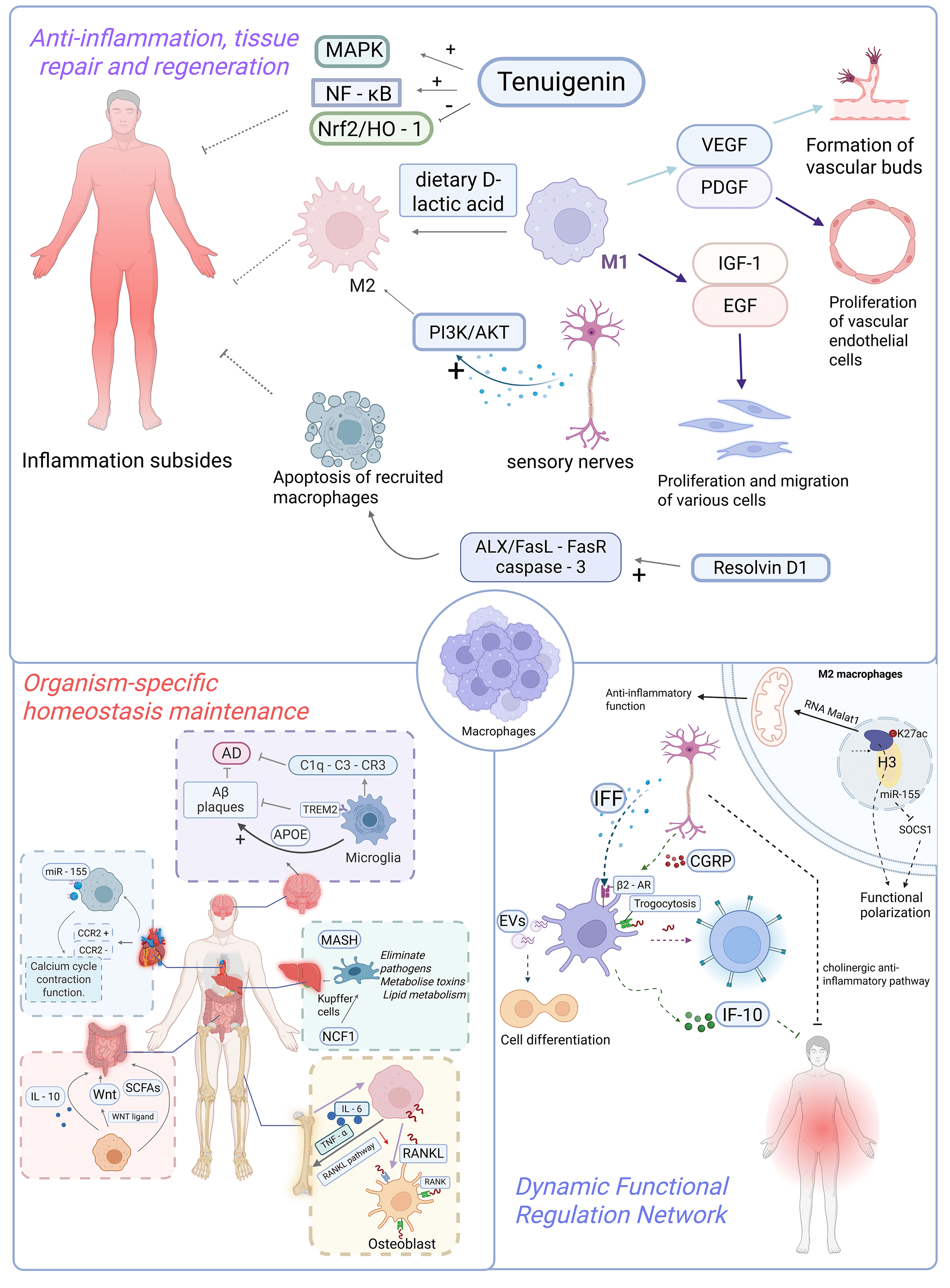

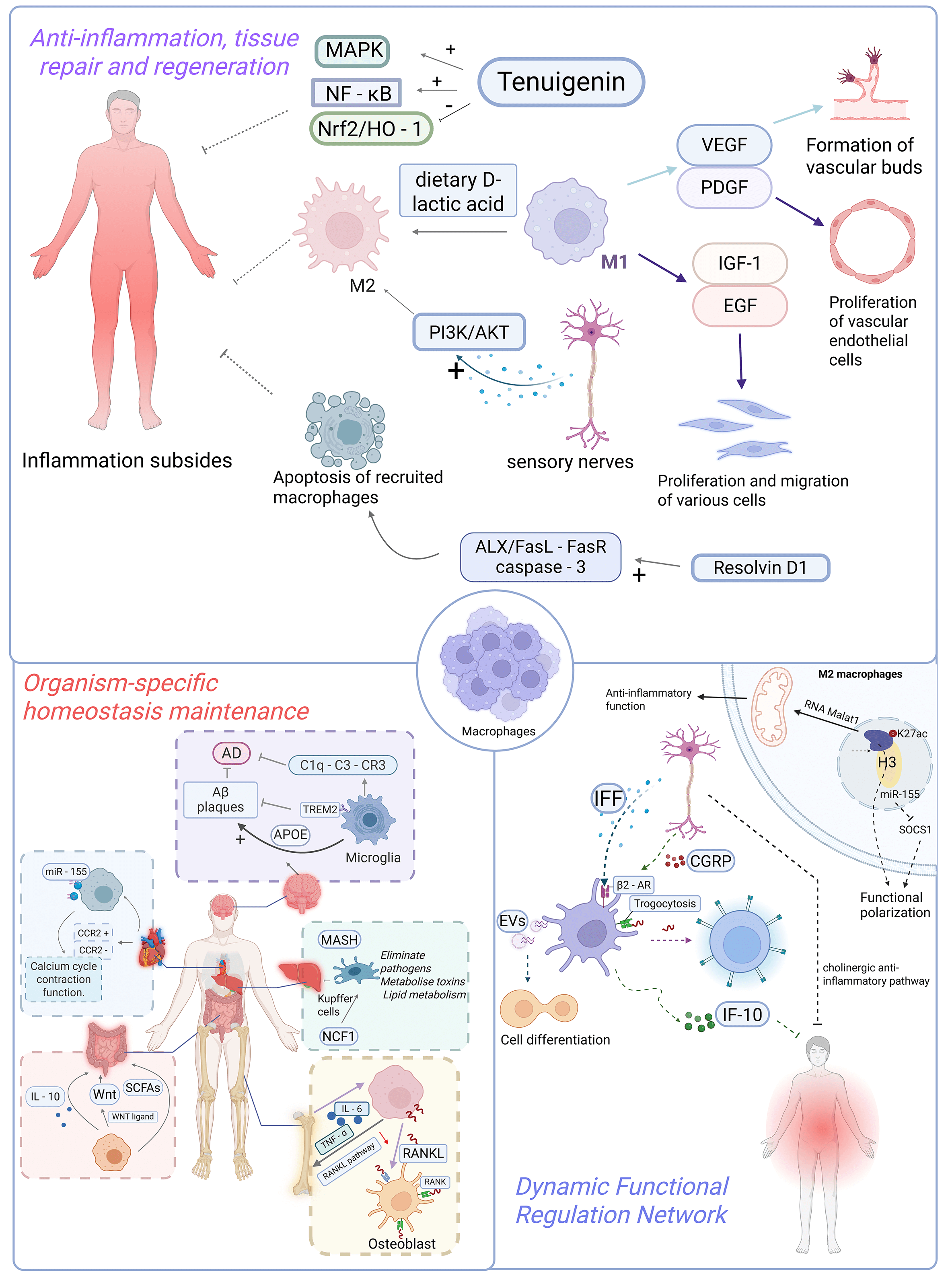

Macrophages are pivotal immune cells in maintaining organismal homeostasis, exhibiting multifaceted functions including phagocytic clearance, immunomodulation, and tissue repair. They orchestrate inflammatory responses, metabolic equilibrium, and tissue-specific regulation (e.g., hepatic detoxification, intestinal microbiota balance, cardiac regeneration, and neuroprotection), while being precisely modulated by epigenetic mechanisms and neural signaling pathways. These sophisticated capabilities establish macrophages as central players in immune defense, tissue regeneration, and therapeutic intervention (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The role of macrophages in physiological tissue homeostasis. (1) Anti-inflammation, tissue repair and regeneration: Macrophages are pivotal

in the resolution of inflammation as well as tissue repair and regeneration: in

terms of inflammatory resolution, they terminate inflammation and facilitate

repair by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines and lipid mediators. Moreover,

substances such as tenuigenin, dietary D-lactic acid, calcitonin gene-related

peptide (CGRP) released by sensory nerves, and resolvin D1 (Rv-D1) accelerate

inflammatory resolution through mechanisms including inhibiting or activating

relevant signaling pathways, regulating macrophage polarization, or promoting

their apoptosis. In the context of tissue repair and regeneration, macrophages

secrete pro-angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) to participate in angiogenesis, thereby

supplying energy to damaged tissues. They also secrete cytokines such as

insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and epidermal growth factor (EGF), which

promote the proliferation and migration of cells including fibroblasts and

keratinocytes, thus expediting tissue repair. (2) Organism-specific homeostasis

maintenance: Kupffer cells in the liver are involved in pathogen clearance, toxin

metabolism, and lipid metabolism regulation, while the protein encoded by the

NCF1 gene can modulate their susceptibility to ferroptosis. Intestinal

macrophages maintain the stability of intestinal flora by secreting IL-10,

promote the repair of intestinal epithelial barriers via secreting WNT ligands,

and are also capable of sensing microbial metabolites to regulate their own

functions, thereby preserving intestinal immune homeostasis. Cardiac macrophages

are categorized into CCR2+ monocyte-derived and CCR2– resident

subsets; the resident macrophages can regulate calcium cycling and contractile

function of cardiomyocytes, and the exosomes carrying miR-155 secreted by them

are able to improve cardiac function. Macrophages in the skeletal system

(osteoclast precursors) facilitate osteoclast differentiation and activation by

expressing RANKL, thereby driving bone resorption; their aberrant activation is

associated with osteoporosis, and the cytokines they secrete can balance the

activities of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Microglia in the central nervous

system mediate synaptic pruning during early neurodevelopment; in Alzheimer’s

disease, the TREM2 receptor on their surface can clear A

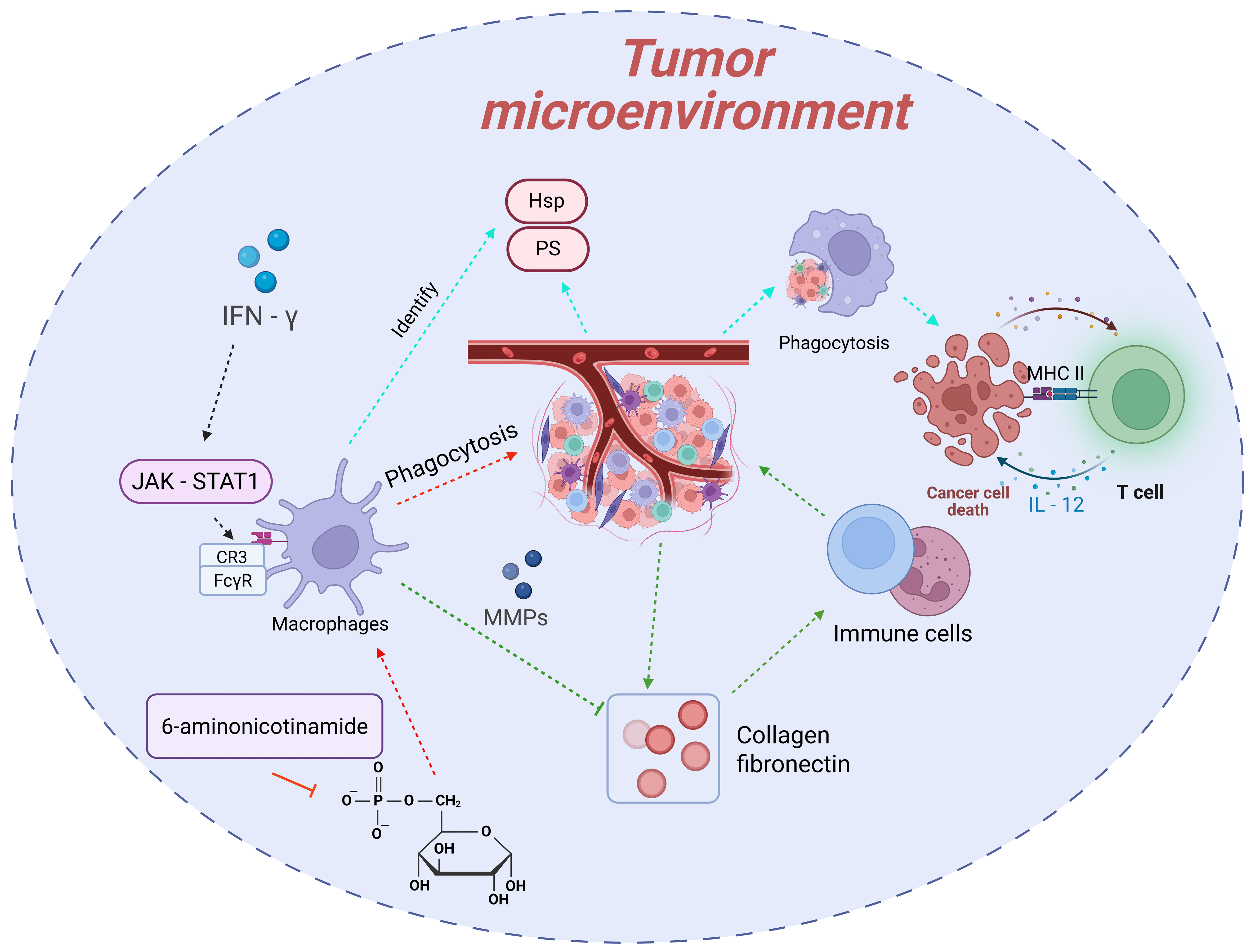

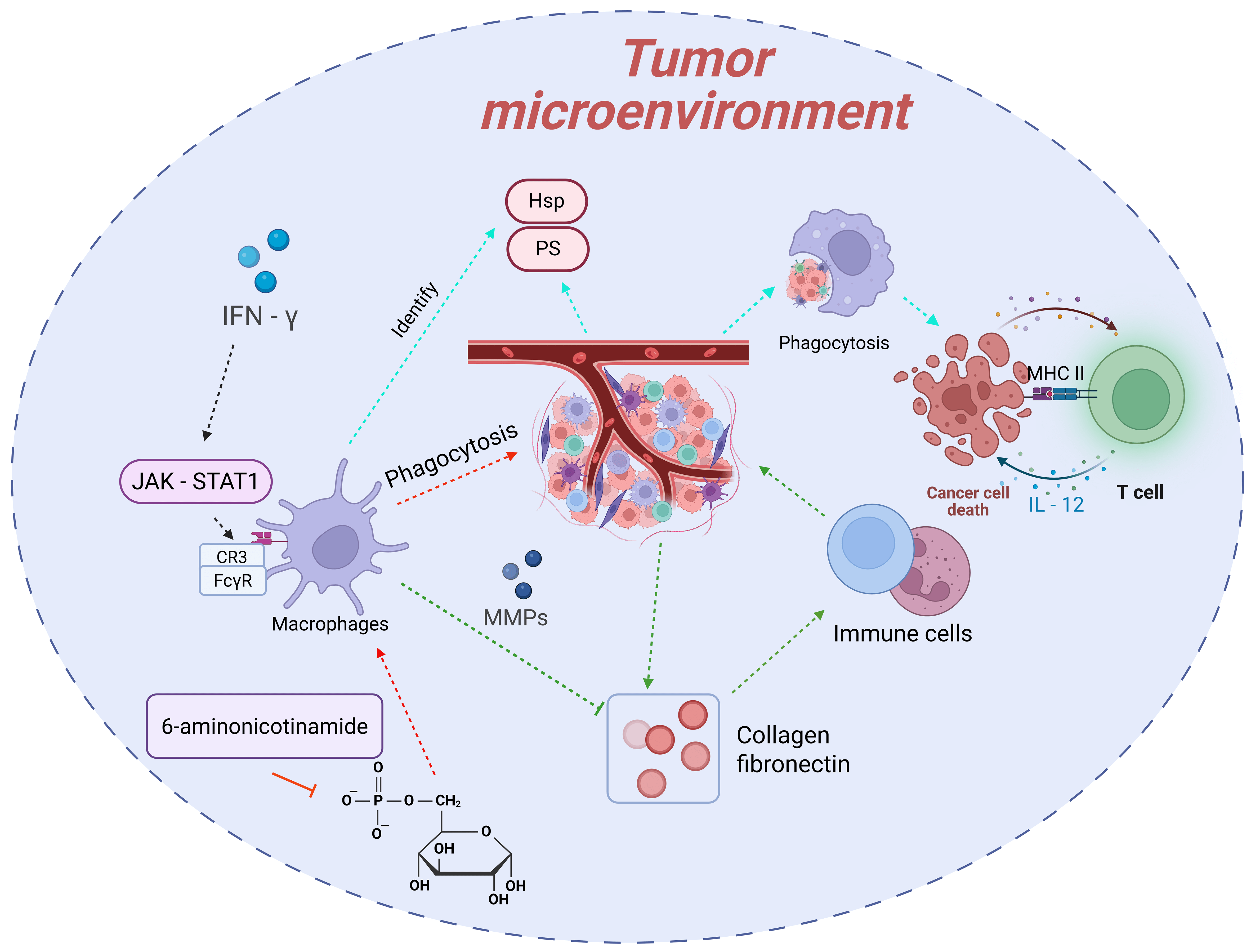

Macrophages, as the “scavengers” of the body, maintain tissue homeostasis by phagocytosing pathogens, senescent cells, and apoptotic debris [21, 22, 23, 24]. In the field of tumor immunology, the phagocytic function of macrophages is recognized as a crucial mechanism for suppressing tumor growth [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]. With the rapid advancement of research technologies and the deepening of studies, numerous novel discoveries have been made regarding the “scavenger” function of macrophages in tumors (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The “scavenger” function of macrophages in tumors and its

regulatory mechanisms. Macrophages recognize and phagocytose abnormal molecules

on the surface of tumor cells through pattern recognition receptors, followed by

degradation. They activate T cells via antigen presentation and cytokine

secretion to trigger adaptive immune responses. Additionally, macrophages can

clear apoptotic debris and degrade extracellular matrix components to improve the

tumor microenvironment. Their “scavenger” function is regulated by mechanisms

such as metabolic reprogramming (e.g., inhibition of the pentose phosphate

pathway, PPP) and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., enhancement by

interferon-

During the phase of recognizing tumor cells, macrophages primarily rely on pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors and scavenger receptors, to identify abnormal molecules on the surface of tumor cells. These molecules arise from genetic mutations, metabolic abnormalities, and other factors, including exposed phosphatidylserine (PS) and heat shock proteins (HSPs). They constitute the key “signals” for macrophages to initiate phagocytic behavior. Once recognition is completed, macrophages promptly trigger the endocytic process, enclosing the tumor cells to form phagosomes. Subsequently, the phagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form phagolysosomes, where tumor cells are gradually degraded and eliminated under the action of lysosomal enzymes, such as proteases and nucleases. This process not only directly reduces the number of tumor cells but also holds profound significance for immune activation. After phagocytosing tumor cells, macrophages, through antigen presentation, present tumor antigens to CD4+ T cells using major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class Ⅱ molecules. Meanwhile, they secrete cytokines like IL-12 to activate the activation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells, thereby triggering and enhancing adaptive immune responses to continuously combat tumors [30, 110, 111, 112].

The “scavenger” function of macrophages is also reflected in their efficient clearance of apoptotic tumor cell debris and abnormal extracellular matrix components in the tumor microenvironment. During the proliferation of tumor cells, a large number of apoptotic debris are generated due to factors such as hypoxia and nutrient deficiency. If these debris are not cleared in a timely manner, they may release pro-inflammatory factors and even promote tumor cell metastasis. Macrophages can rapidly phagocytose these apoptotic debris, effectively avoiding their negative impact on the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix components in the tumor microenvironment, such as collagen and fibronectin, can hinder the infiltration of immune cells. Macrophages, however, can degrade these components by secreting matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other substances, improving the permeability of the tumor microenvironment and creating favorable conditions for other immune cells to function [31, 113].

Recent studies have achieved significant breakthroughs in understanding the regulatory mechanisms underlying the “scavenger” function of macrophages. Metabolic reprogramming has been confirmed as a key link in regulating this function. For example, studies have revealed that inhibiting the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) in macrophages can enhance their ability to phagocytose and clear lymphoma cells. As an important intracellular metabolic pathway, PPP is mainly responsible for generating NADPH and ribose-5-phosphate, providing raw materials and reducing power for biosynthesis. When PPP is inhibited, the level of NADPH in macrophages decreases, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increases, which in turn activates downstream signaling pathways, upregulates the expression of phagocytosis-related genes, and ultimately enhances phagocytic function [31].

Cytokines and signaling molecules in the tumor microenvironment also exert a

significant influence on the “scavenger” function of macrophages.

Interferon-

Macrophages play a key role in the resolution of inflammation. By secreting

anti-inflammatory cytokines and lipid mediators, they terminate the inflammatory

response and promote tissue repair [32]. Tenuigenin, a natural flavonoid

compound, can exert anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting the MAPK and

NF-

Macrophages promote the proliferation and migration of vascular endothelial cells by secreting pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), thereby participating in the process of angiogenesis [119]. In wound healing models, VEGF released by macrophages induces the formation of vascular sprouts, supplying oxygen and nutrients to the damaged tissue and facilitating repair [120]. Additionally, macrophages can accelerate tissue repair by secreting cytokines such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and epidermal growth factor (EGF), which promote the proliferation and migration of various cells, including fibroblasts and keratinocytes [121, 122].

Tissue-resident macrophages play essential roles in preserving the physiological equilibrium of diverse organs, exhibiting remarkable functional specialization shaped by local cues. Across systems such as the liver, intestine, heart, skeletal tissue, and central nervous system, macrophages act as sentinels and regulators of homeostasis (Table 2, Ref. [57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147]).

| Tissue/organ | Macrophage type | Key functions | Representative mechanisms/molecules | Recourse |

| Liver | Kupffer cells | Maintain hepatic homeostasis (pathogen clearance, toxin/lipid metabolism); Modulate NASH inflammation and fibrosis | NCF1, MASH, ferroptosis | [57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 123, 124] |

| Intestine | Intestinal macrophages | Sustain microbiota homeostasis (IL-10-mediated anti-pathogen); Promote epithelial repair (WNT ligands); Regulate immunity via SCFA sensing | IL-10, Wnt ligands, SCFA sensing | [59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 125, 126] |

| Heart | CCR2–resident macrophages; CCR2+monocyte - derived macrophages | Preserve myocardial contraction (calcium cycling); Mediate infarct repair (M1: necrotic clearance; M2: scar formation); Protect cardiomyocytes via exosomal miR-155 | miR-155 exosomes, M1/M2 polarization | [74, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 145] |

| Skeletal system | Osteoclast precursors | Drive osteoclast differentiation (RANKL-RANK pathway); Balance bone metabolism (cytokine-mediated osteoblast/osteoclast regulation) | RANKL-RANK signaling, TNF-α, IL-6 | [133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 146, 147] |

| CNS | Microglia | Support neurodevelopment (complement-mediated synaptic pruning); Clear Aβ plaques in AD (TREM2-dependent); APOE4-associated neurodamage promotion | C1q-C3-CR3, TREM2, APOE4 | [74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 141, 142, 143, 144] |

NCF1, Neutrophil Cytosolic Factor 1; MASH, Macrophage

Apoptosis-Associated Sphingolipid Hydrolase; RANKL, Receptor Activator of Nuclear

Factor

As the metabolic hub of the body, the liver harbors a large population of macrophages known as Kupffer cells [123, 124]. Kupffer cells play multifaceted roles in maintaining hepatic homeostasis, including pathogen clearance, toxin metabolism, and lipid metabolism regulation. Studies have shown that the reactive oxygen regulatory protein encoded by neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 (NCF1) modulates the susceptibility of Kupffer cells to macrophage apoptosis-associated sphingolipid hydrolase (MASH)-mediated ferroptosis. In non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) models, overactivation of Kupffer cells leads to increased release of inflammatory factors, exacerbating liver fibrosis. Targeted modulation of Kupffer cell function may offer novel therapeutic strategies for NASH [58].

As the largest immune organ in the human body, intestinal homeostasis relies on the interaction between macrophages and the gut microbiota [125, 126]. Macrophages maintain microbial diversity and stability by secreting IL-10, preventing pathogen invasion [59]. In intestinal injury models, macrophages secrete WNT ligands to activate the Wnt signaling pathway in intestinal stem cells, promoting epithelial barrier repair [60, 71]. Additionally, intestinal macrophages sense microbial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids, SCFAs) to modulate their own functions, thereby regulating intestinal immune homeostasis [72, 73].

Cardiac macrophages can be classified into CCR2+ monocyte-derived macrophages and CCR2– resident macrophages [74, 127]. Resident macrophages play a pivotal role in maintaining cardiac homeostasis by regulating cardiomyocyte calcium cycling and preserving contractile function [13]. In myocardial infarction models, macrophage polarization significantly influences cardiac repair. Early recruitment of M1 macrophages clears necrotic tissue, but excessive inflammation exacerbates myocardial injury. In contrast, later polarization toward M2 macrophages promotes tissue repair and scar formation [128, 129, 130]. Studies indicate that macrophage-derived exosomes carrying miR-155 can enhance cardiomyocyte survival and improve cardiac function by targeting specific cardiomyocyte genes [131, 132].

Macrophages in the skeletal system, known as osteoclast precursors, play a

critical role in bone remodeling [133, 134, 135]. By expressing receptor activator of

nuclear factor

Macrophages in the central nervous system, termed microglia, are indispensable

for neural development and homeostasis [75, 76]. During early neurodevelopment,

microglia mediate synaptic pruning via the complement pathway (C1q-C3-CR3),

eliminating redundant synapses to refine neural circuits [77, 78, 79, 80]. In

neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), microglial

dysfunction is closely linked to disease progression. Triggering receptor

expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), a key receptor on microglia, recognizes

A

The functional plasticity of macrophages is primarily governed by epigenetic regulatory mechanisms [149, 150, 151]. Histone modifications, a key mode of epigenetic regulation, modulate gene expression by altering chromatin structure [152, 153, 154]. Studies demonstrate that H3K27ac-mediated enhancer reprogramming determines the reparative phenotype of macrophages, guiding their functional polarization after tissue injury [155]. Additionally, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) play pivotal roles in macrophage regulation. The long non-coding RNA Malat1 influences the anti-inflammatory functions of macrophages by regulating mitochondrial metabolism-related genes [156, 157, 158]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) fine-tune macrophage polarization and function through mRNA targeting [159, 160]. For instance, miR-155 promotes M1 polarization by suppressing SOCS1 expression [161, 162, 163, 164].

Macrophages serve as critical hubs in the extensive and intricate network

bridging the nervous and immune systems, modulating their functions in response

to neural signals [165, 166, 167]. Sympathetic nerves release norepinephrine to

activate

Technology advancementshave provided novel tools to dissect macrophage regulatory mechanisms [10, 11, 174, 175]. Spatial multi-omics technologies now enable single-cell-resolution analysis of spatial interactions between macrophages and other cell types [176, 177, 178]. Research reveals that macrophages can directly transfer antigens to T cells through synapse-like structures (e.g., trogocytosis), enhancing antigen presentation and immune responses [179, 180]. Extracellular vesicles (EVs), as essential carriers of intercellular communication, deliver bioactive molecules (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids, lipids) to modulate recipient cell functions [181, 182, 183, 184]. Macrophage-derived EVs, for example, regulate stem cell differentiation and tissue repair via miRNA transfer [185, 186].

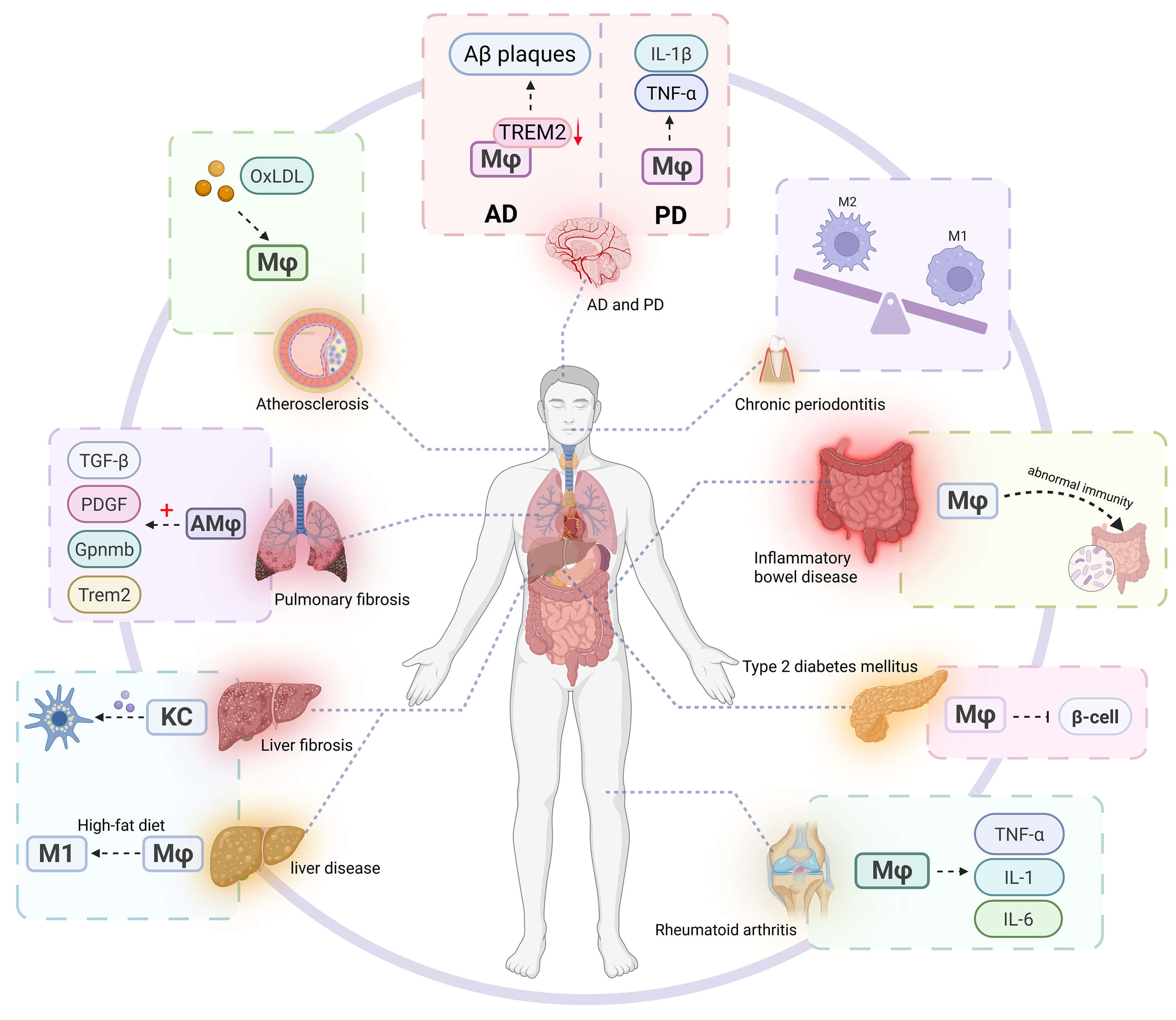

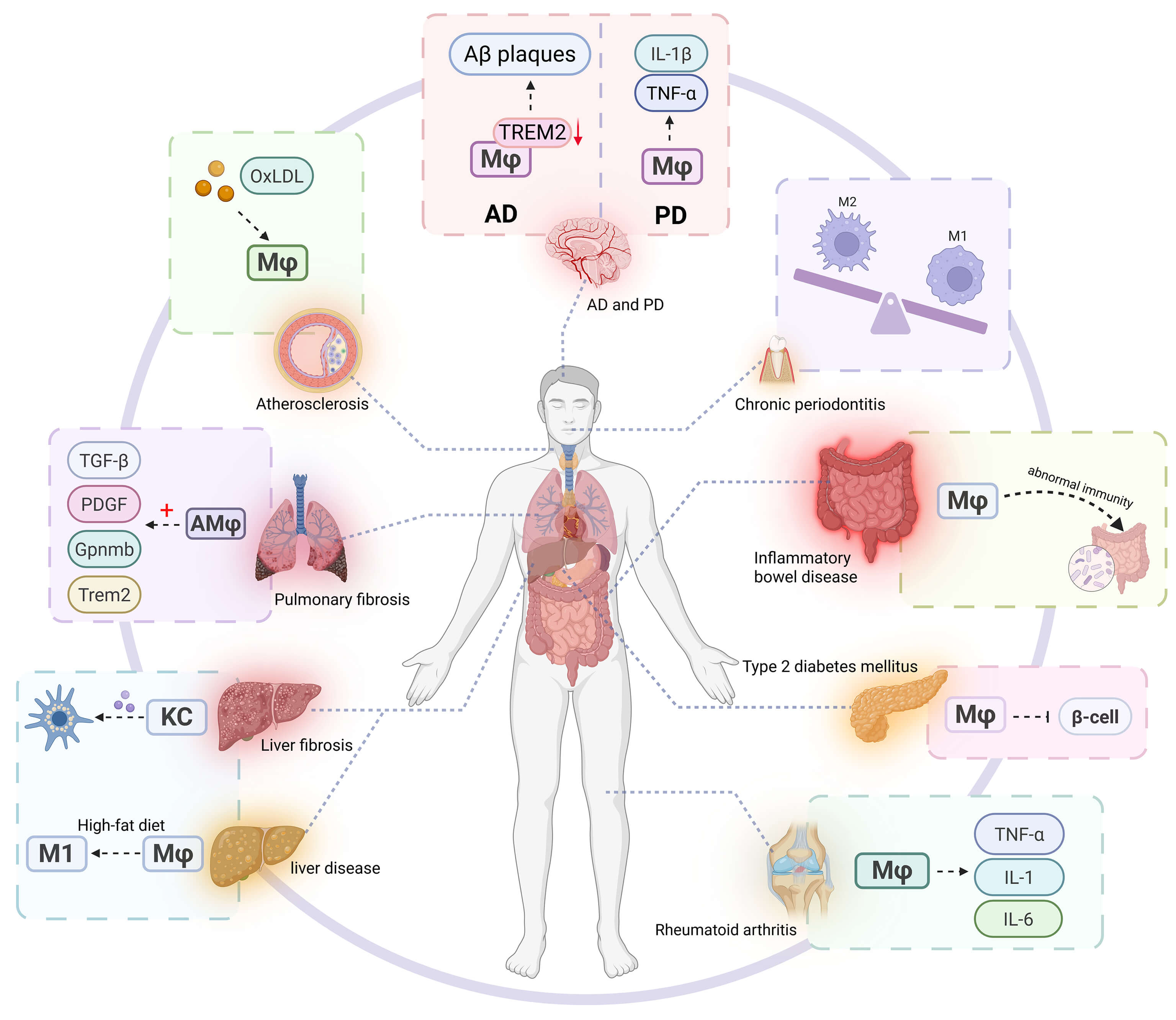

Macrophages serve as pivotal regulators in the pathogenesis of diverse diseases. Their aberrant activation contributes to tissue damage, promotes fibrotic matrix deposition, induces metabolic dysregulation, facilitates tumor immune evasion, exacerbates neurodegenerative processes, and perpetuates chronic inflammatory states during aging, rendering macrophage-targeted interventions a promising therapeutic avenue (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Macrophages play a key role in various diseases. In chronic

inflammatory diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease,

and chronic periodontitis), the continuous activation or polarization imbalance

of macrophages leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as

TNF-

In the tumor immune microenvironment, macrophages play an extremely complex and crucial role, profoundly affecting the occurrence and development of tumors as well as the tissue homeostasis of the body [187, 188, 189]. Macrophages exhibit high plasticity and can differentiate into various polarized phenotypes in response to different signaling stimuli within the tumor microenvironment. Among these, M2-polarized macrophages are closely associated with the malignant progression of tumors.

M2-polarized macrophages act like “accomplices” in the tumor microenvironment, promoting tumor progression through multiple pathways. They secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which directly acts on vascular endothelial cells surrounding the tumor, stimulating their proliferation, migration, and lumen formation, thereby facilitating tumor angiogenesis. These newly formed blood vessels not only provide sufficient oxygen and nutrients for the rapid proliferation of tumor cells but also establish “channels” for distant metastasis of tumor cells, enabling them to spread to other parts of the body via the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

Meanwhile, interleukin-10 (IL-10) secreted by M2 macrophages is a potent immunosuppressive factor. It can inhibit the activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic functions of immune cells such as T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, reducing the body’s immune surveillance and killing capacity against tumor cells. Furthermore, M2 macrophages highly express programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, which specifically binds to programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on T cells, triggering the immunosuppressive signaling pathway in T cells. This renders T cells unable to effectively recognize and attack tumor cells, as if placing “shackles” on T cells, creating a microenvironment conducive to the growth, survival, and immune escape of tumor cells, and severely disrupting the tissue homeostasis of tumor immune balance [55, 190]. In addition, M2 macrophages can secrete substances such as matrix metalloproteinases, which degrade the extracellular matrix surrounding the tumor, creating favorable conditions for the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells [188, 191].

The emerging CAR-M therapy has brought groundbreaking hope for tumor treatment, representing a significant innovation in the field of tumor immunotherapy. Taking CD19-CAR macrophages as an example, chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) capable of specifically recognizing certain antigens (e.g., CD19) on the surface of tumor cells are introduced into macrophages through advanced genetic engineering techniques. A CAR consists of an antigen-recognition domain, a hinge region, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain. Among these, the antigen-recognition domain, typically derived from the variable region of a monoclonal antibody, can precisely match the “lock”—specific antigen—on the surface of tumor cells like a “key”, thereby endowing macrophages with the ability to specifically recognize and target tumor cells for killing.

Genetically modified CAR-M macrophages can penetrate physical barriers such as

the fibrotic envelope surrounding tumor tissues and infiltrate into the interior

of tumor tissues by virtue of their migratory capacity. They phagocytose and

degrade tumor cells through their strong phagocytic ability; meanwhile, they

secrete cytotoxic substances such as tumor necrosis factor-

Metabolic checkpoints have shown great potential in tumor immunotherapy, providing new ideas and strategies for cancer treatment. To meet the needs of rapid growth and unlimited proliferation, tumor cells exhibit significant differences in metabolic patterns compared with normal cells, with unique metabolic characteristics. Among them, the growth and survival of tumor cells are highly dependent on arginine, a semi-essential amino acid that plays a crucial role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and other processes. Tumor cells often lack the key enzymes required for arginine synthesis, so they need to uptake large amounts of arginine from the tumor microenvironment to maintain their metabolic demands.

Based on this characteristic, arginine deprivation combined with anti-PD-1 therapy has become a highly promising combined treatment strategy. Arginine deprivation can degrade arginine in the tumor microenvironment through the use of drugs such as arginase or arginine deiminase, causing tumor cells to fail to proliferate normally or even undergo apoptosis due to arginine deficiency. Meanwhile, arginine deficiency can also affect the function of immunosuppressive cells, such as reducing the number and activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and enhancing the function of effector T cells. In contrast, anti-PD-1 therapy can block the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1, relieve the immunosuppression of T cells, and restore the anti-tumor activity of T cells. When used in combination, they can produce a synergistic effect, not only directly inhibiting the growth of tumor cells but also enhancing the body’s anti-tumor immune response, thereby improving the efficacy of tumor treatment. In various tumor models such as melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer, this combined treatment strategy has shown more significant anti-tumor effects than single treatment, effectively delaying tumor progression and prolonging the survival of model animals [197, 198, 199].

The pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases—including rheumatoid

arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and chronic periodontitis—is

closely linked to sustained macrophage activation [36, 37, 200, 201]. In RA,

activated macrophages release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis

factor-

Fibrotic diseases such as pulmonary, hepatic, and renal fibrosis are characterized by excessive extracellular matrix deposition leading to organ dysfunction [46, 47, 204, 205, 206]. Macrophages play a pivotal role in fibrotic disease development.

In pulmonary fibrosis, alveolar and monocyte-derived macrophages exhibit high

heterogeneity and dynamic changes in pro-fibrotic gene expression during disease

progression [48, 49, 207]. Research indicates that macrophage-specific

upregulation of Gpnmb and Trem2 gene levels correlates with

fibrosis progression, suggesting their regulatory importance [48, 50].

Additionally, macrophage-secreted pro-fibrotic factors like transforming growth

factor-

In hepatic fibrosis, activated Kupffer cells secrete inflammatory mediators and pro-fibrotic factors that induce hepatic stellate cell activation, transforming them into myofibroblasts that synthesize abundant extracellular matrix, ultimately causing liver fibrosis [61, 209]. Therapeutic strategies targeting macrophages, such as inhibiting macrophage recruitment/activation or modulating their polarization state, may offer new directions for treating fibrotic diseases [210, 211].

Macrophage mechanosensing also significantly influences fibrosis. The Piezo1 channel on macrophage surfaces mediates their response to tissue stiffness. When tissue hardness changes due to fibrosis, macrophage Piezo1 channels activate, triggering intracellular signaling cascades that initiate Yes-associated protein (YAP)-dependent fibrotic responses [212]. As a critical transcriptional coactivator, activated YAP promotes expression of fibrosis-related genes, markedly increasing extracellular matrix synthesis and exacerbating fibrosis progression. This reveals an important pathway through which mechanical forces influence tissue fibrosis via macrophages [213].

Macrophage function is intricately regulated by metabolic pathways, including lipid processing, iron handling, and mitochondrial dynamics. These metabolic features not only shape macrophage polarization and plasticity, but also directly contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), type 2 diabetes, and atherosclerosis [214, 215].

Lipid metabolism critically affects macrophage phenotype and inflammatory status. For instance, 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC) induces immunosuppressive programming via lysosomal AMPK signaling [216, 217]. In atherosclerosis, excessive uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) leads to foam cell formation and plaque buildup. Targeting lipid-handling molecules such as FABP4 has been shown to reduce foam cell formation and attenuate disease progression [218].

Iron metabolism is another essential regulatory axis. Macrophages express ferritin and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) to mediate iron storage and recycling. Under inflammatory stress, iron overload increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, amplifying tissue injury. Genes such as transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) modulate iron uptake and may be leveraged to regulate inflammatory output [54, 219, 220].

Mitochondrial dynamics, including fusion, fission, and mitophagy, are tightly linked to macrophage activity. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release can activate STING-dependent type I interferon signaling, while mitophagy via the PINK1/Parkin pathway maintains mitochondrial quality and anti-inflammatory capacity. Disruption of these processes impairs macrophage resolution functions and tissue repair [221, 222].

These metabolic features directly impact disease outcomes. In NAFLD, high-fat

diets drive adipose macrophage accumulation and M1 polarization, promoting

hepatic insulin resistance and steatosis. Scavenger receptor A1 (SR-A1) on

macrophages plays a protective role, and its deficiency worsens inflammation and

fibrosis [190, 223]. In type 2 diabetes, macrophage infiltration into pancreatic

islets disrupts

In neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s

disease (PD), the dysfunction of microglia (macrophages in the central nervous

system) is closely related to the disease progression [232, 233]. In AD, the

abnormal response of microglia to A

As the body ages, macrophages gradually enter a senescent state. Among them, senescent macrophages with the characteristic of p16INK4a+ play a negative role in senile pulmonary fibrosis. The accumulation of these cells interferes with the normal physiological functions of the lungs. They may secrete substances such as inflammatory factors and matrix metalloproteinases, disrupting the balance of the extracellular matrix of the lung tissue, activating fibrosis-related signaling pathways, causing the lung tissue to become fibrotic and gradually impairing the gas exchange function. Using Senolytic targets to eliminate p16INK4a+ senescent macrophages can effectively reduce the secretion of harmful factors, restore the homeostasis of the lung tissue microenvironment, and provide new ideas for improving senile pulmonary fibrosis [84, 242].

Precision targeting technology shows excellent potential in the treatment of macrophage-related diseases. Spatiotemporal specific gene editing technology, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 liposome targeted delivery system, uses liposomes as carriers. By precisely modifying the liposomes, they can specifically recognize and bind to specific receptors on the surface of target macrophages [85, 86, 87]. This targeted delivery method equips the CRISPR-Cas9 system with an accurate navigation system, efficiently transporting it to specific tissues or cells. After reaching the destination, the CRISPR-Cas9 system can precisely edit the genes related to diseases in macrophages [243]. For example, in tumor treatment, macrophages in the tumor microenvironment are often “domesticated” by tumor cells and transformed into a phenotype that promotes tumor growth. Through spatiotemporal specific gene editing, the abnormal gene expression of these macrophages can be corrected, their anti-tumor activity can be reactivated, and their killing function against tumor cells can be restored, breaking the barrier of tumor immune escape [244].

Smart responsive nanoparticles are also an essential breakthrough in precision targeting technology. Take the pH/ROS dual-sensitive nanocarrier as an example. The tumor microenvironment has the unique characteristics of a low pH value and a high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [244]. The nanocarrier remains stable in the blood circulation. When it reaches the vicinity of the tumor tissue, the low pH value and high ROS level in the tumor microenvironment will trigger a structural change in the nanocarrier, just like unlocking it, causing it to release the pre-loaded drugs or bioactive molecules [245]. These molecules can precisely act on tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), inducing the reprogramming of TAMs. The originally tumor-promoting TAMs can be transformed into a tumor-inhibiting phenotype after reprogramming, significantly enhancing the phagocytic and killing abilities of macrophages against tumor cells, providing a precise and efficient new strategy for tumor treatment.

Cell engineering therapy brings new vitality to macrophage therapy. CAR-M 2.0 technology is an essential upgrade of the traditional CAR-M cell therapy. Although the conventional CAR-M cell therapy has shown some potential in tumor treatment, it faces many challenges in the complex tumor microenvironment. CAR-M 2.0 is equipped with a dual-functional module of PD-1 blockade and IL-12 secretion [195]. On the one hand, it can precisely recognize the antigens on the surface of tumor cells through CAR; on the other hand, the PD-1 blockade function can effectively relieve the immunosuppressive state in the tumor microenvironment, allowing the immune system to play its role fully [246]. At the same time, the secretion of IL-12 further activates the immune system, not only enhancing the killing activity of macrophages against tumor cells themselves but also recruiting and activating other immune cells to participate in the anti-tumor battle together, significantly improving the treatment effect in solid tumors and bringing new hope for cancer treatment [247].

Synthetic biology modification technology provides an effective means for precisely regulating the polarization of macrophages. Constructing a light-controlled gene circuit is an essential progress in this field. Through careful design, light-sensitive elements are connected to key genes that regulate the polarization of macrophages, forming a gene circuit that can be precisely regulated by light [247]. When light of a specific wavelength and intensity irradiates, the gene circuit is activated, thereby precisely regulating the polarization of macrophages towards one particular functional phenotype [175]. In inflammatory diseases, the light instruction can prompt macrophages to polarize towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype, alleviating the inflammatory response and promoting tissue repair; in tumor treatment, it can also make macrophages polarize towards an anti-tumor phenotype, enhancing the body’s anti-tumor immune response, providing a flexible and precise strategy for the treatment of different types of diseases [2, 248].

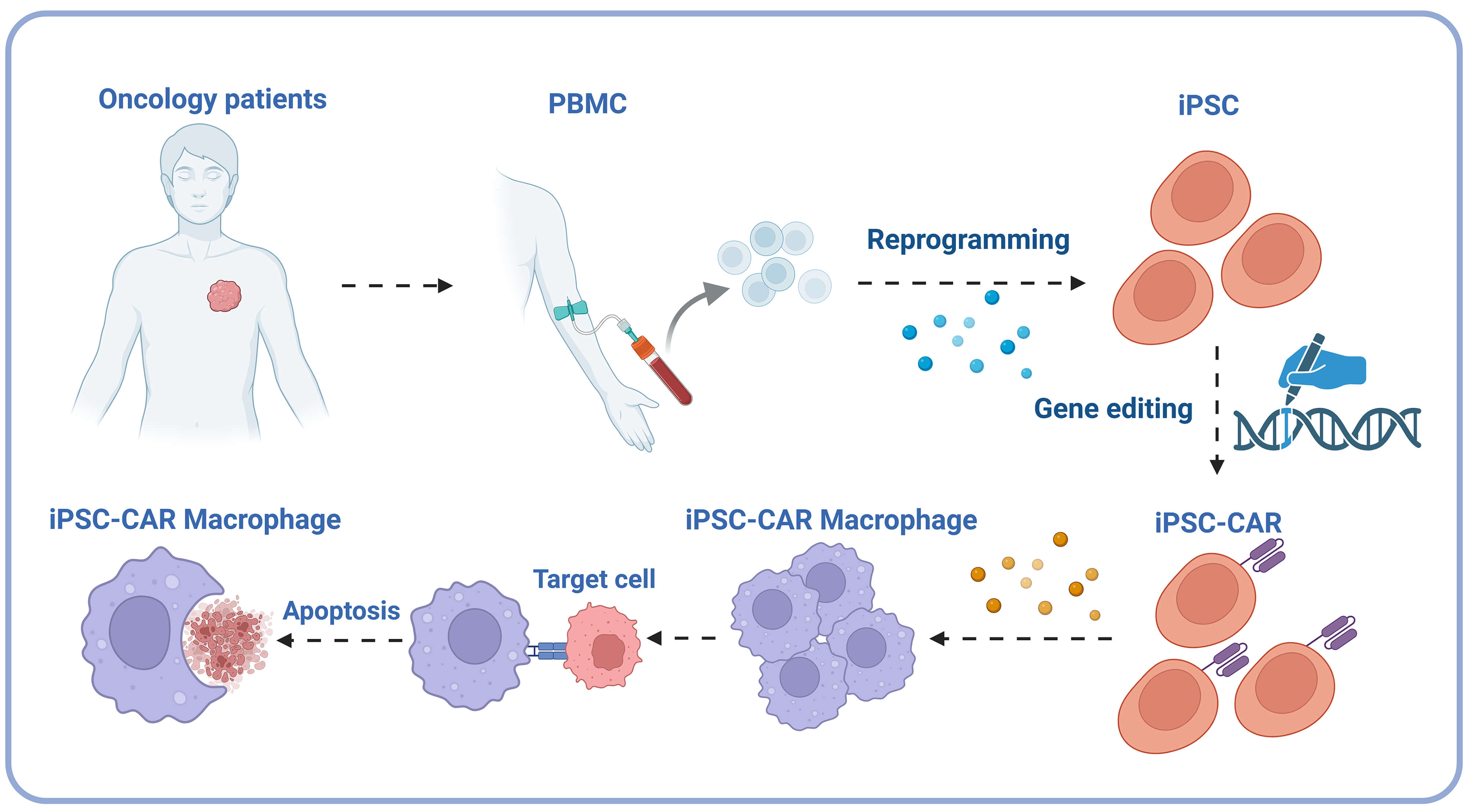

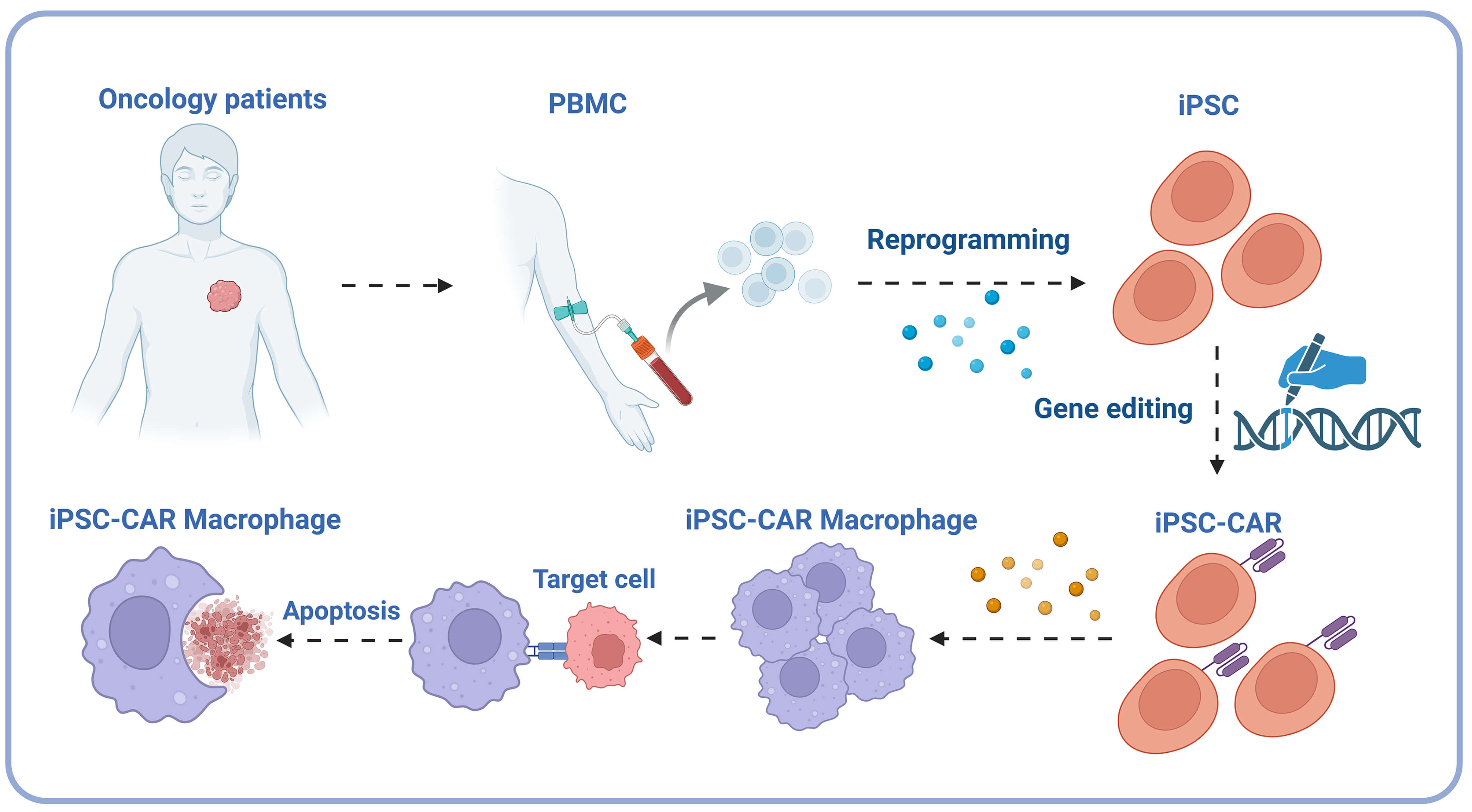

The iPSC-CAR macrophage technology cleverly utilizes induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) characteristics. iPSCs have the potential for unlimited proliferation and multi-directional differentiation [193]. This technology first reprograms somatic cells from patients into iPSCs, restoring them to a pluripotent state. It then induces iPSCs to differentiate into macrophages and makes them express chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) [192]. After this series of operations, a large number of macrophages with specific antigen recognition ability can be prepared, solving the problem of limited sources of traditional macrophages [192] (Fig. 4). The recognition and killing abilities of these modified macrophages against specific targets are significantly enhanced, and they have broad application prospects in tumor immunotherapy and the treatment of other macrophage-related diseases. They are expected to become one of the core strategies of a new generation of cell therapy [249, 250].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

iPSC-CAR macrophage technical flowchart. The process involves extracting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from oncology patients, reprogramming them into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), introducing chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) through gene editing, and ultimately differentiating them into iPSC-CAR macrophages capable of identifying and inducing apoptosis in cancer cells. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cells; CAR, chimeric antigen receptors. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/nglah6m.

Microbiome intervention provides a new perspective for the treatment of macrophage-related diseases. Research on regulating of microbiota metabolites has found that butyrate, as a critical microbiota metabolite, plays a key role in regulating the functions of macrophages [72, 251]. Butyrate can affect macrophages’ gene expression and functional state by inhibiting histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) [252]. In tumor treatment, butyrate can regulate the functions of immune cells such as macrophages, promote the polarization of macrophages towards an anti-tumor phenotype, and enhance their phagocytic and killing activities against tumor cells [253]. At the same time, butyrate can also regulate the functions of other immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, reshape the tumor immune microenvironment, and activate the body’s own anti-tumor immune response, opening up a new strategy for tumor treatment based on microbiota metabolites [254, 255, 256, 257].

Traditional research methods are challenging in capturing individual macrophages’ unique behaviors and dynamic changes, and can only obtain population average information. However, real-time dynamic monitoring of single-cell multi-omics (in vivo imaging combined with scRNA-seq) has opened up a new way to explore the mysteries of macrophages [258]. In vivo imaging can track the migration, and proliferation of macrophages in the body and their interactions with other cells in real time without disrupting the organism’s physiological state. scRNA-seq can reveal the gene expression profiles of individual macrophages at different time points, and clarify their functional states and molecular characteristics. The combination of the two enables researchers to dynamically analyze the changes in the molecular regulation network of macrophages during the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and the occurrence and development of diseases at the single-cell level, accurately identify key cell subsets and functional conversion nodes, and provide a theoretical basis for targeted treatment strategies [259, 260].

The functions of macrophages are jointly affected by various factors in their microenvironment. The integrated organoid-immune chip model provides a powerful research tool for this [7, 18]. Organoids can highly reproduce the tissue-specific microenvironment, and the immune chip can accurately detect the dynamic changes of various immune molecules. The model that integrates the two can produce the interactions between macrophages and other cells and microenvironmental factors in vitro. For example, in tumor research, this model can be used to explore the coordinated regulation of tumor cells, stromal cells, immune cells, and metabolites in the tumor microenvironment on the polarization and functions of macrophages, deeply understand the mechanism of tumor immune escape, and provide an experimental platform for tumor immunotherapy [7].

The regulatory network of macrophages is highly complex. With the help of AI-driven target prediction, graph neural networks can be used to integrate and analyze massive biological data to accurately diagnose this regulatory network [261, 262]. Graph neural networks construct complex network models by taking the information of genes, proteins, metabolites, etc., of macrophages as nodes and their interactions as edges. By learning and analyzing this model, potential drug targets and therapeutic intervention sites can be predicted, accelerating the research and development process of drugs for macrophage-related diseases and providing more targeted strategies for clinical treatment. These cutting-edge technologies assist macrophage research from different aspects and are expected to promote breakthroughs in related fields [260].

Macrophages are key in maintaining the body’s immune balance and tissue homeostasis. Among them, the functional compensation mechanisms of tissue-resident and monocyte-derived macrophages, the encoding of spatially specific immune responses by metabolite gradients, and the analysis of the conservation and heterogeneity of macrophage functions across species are all key areas of current research [263, 264]. Tissue-resident macrophages have been colonized in various tissues and organs since the early stage of embryonic development and play a fundamental role in maintaining tissue homeostasis. Monocyte-derived macrophages are recruited from the blood circulation to tissues under stress conditions such as inflammation. Currently, these issues are still unclear for the functional compensation mechanisms of the two under different physiological and pathological states, such as when tissue-resident macrophages dominate during tissue damage repair, when monocyte-derived macrophages play a significant role, and how they coordinate and compensate. Answering these questions will help to deeply understand the complex mechanisms of macrophages in maintaining tissue homeostasis and disease repair, and provide theoretical guidance for treating related diseases [264, 265].

How the concentration gradients of various metabolites in the tissue microenvironment affect the functional polarization of macrophages and encode spatially specific immune responses is a key issue that needs to be solved urgently. For example, in the tumor microenvironment, the metabolite gradients in hypoxic and oxygen-rich regions prompt macrophages to exhibit different polarization directions, affecting tumor growth and metastasis. Analyzing this mechanism will help to reveal the spatial heterogeneity of the occurrence and development of diseases and provide a basis for precise treatment strategies based on microenvironmental metabolic regulation [266, 267].

Macrophages are widely present in different species and are crucial for maintaining the body’s immune balance and tissue homeostasis. The functions of macrophages among different species have both conservation, such as possibly having similar phagocytic and bactericidal functions when resisting pathogen infections, and evident heterogeneity, with significant differences in the repair response to self-tissue damage and the synergistic effect with the adaptive immune system. In-depth analysis of their conservation and heterogeneity is conducive to the rational selection of animal models for macrophage-related research and promoting the better transformation and application of basic research results to treat human diseases [268, 269].

The clinical translation of macrophage-related research faces many challenges. First, the safety and effectiveness of drugs or therapies that precisely target macrophages in clinical trials still need to be further verified. Optimizing the treatment plan and reducing adverse reactions are key to clinical translation [270, 271]. Second, cell engineering treatment strategies, such as CAR-M technology, face problems such as complex cell preparation processes and high costs. Achieving large-scale production and clinical promotion is an urgent problem to be solved [215]. In addition, the standardization and individualization of microbiome intervention are also one of the challenges in clinical application. Formulating personalized microbiome intervention plans according to patients’ specific conditions and improving the treatment effect is the direction of future research. Finally, establishing effective clinical monitoring indicators to evaluate the efficacy and safety of macrophage-related treatments is also an important issue that needs to be solved in the process of clinical translation [196, 270, 271].

As a core component of the innate immune system, macrophages have expanded their functional scope from the traditional M1/M2 polarization model to “tissue microenvironment engineers”, exerting diverse roles in maintaining physiological homeostasis and driving disease progression. Their characteristics and regulatory mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment are particularly representative.

Under physiological conditions, macrophages perform phagocytic functions as “scavengers” to engulf pathogens and apoptotic debris. They secrete anti-inflammatory factors to terminate inflammation and promote tissue repair, regulate lipid, iron, and mitochondrial metabolism to maintain metabolic balance, and execute tissue-specific homeostatic functions in organs such as the liver, intestines, and heart. For instance, hepatic Kupffer cells participate in toxin metabolism, intestinal macrophages sense microbiota signals to regulate immunity, and cardiac resident macrophages maintain myocardial contractile function. Meanwhile, epigenetic regulation (e.g., histone modifications, non-coding RNAs) and neuro-immune crosstalk (e.g., sympathetic nerve-derived norepinephrine) precisely modulate their functions, forming a complex dynamic network.

In disease states, macrophage dysfunction is widely involved in processes such

as chronic inflammation, fibrosis, metabolic diseases, and neurodegenerative

disorders: in rheumatoid arthritis, they release pro-inflammatory factors to

exacerbate joint damage; in pulmonary fibrosis, they secrete TGF-

The tumor microenvironment represents a concentrated manifestation of macrophage functional plasticity. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) polarize toward the M2 phenotype in a microenvironment characterized by low pH and high ROS. They promote angiogenesis by secreting VEGF, inhibit immune cell activity via IL-10 and PD-L1 release, and degrade the extracellular matrix to facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis, thereby establishing an immunosuppressive microenvironment. In response, strategies such as precision targeting technologies (e.g., spatiotemporal editing via CRISPR-Cas9 to correct abnormal gene expression in TAMs, pH/ROS-sensitive nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery), cell engineering therapies (e.g., CAR-M 2.0 with PD-1 blockade and IL-12 secretion modules to enhance anti-tumor activity; iPSC-CAR macrophage technology to address source limitations), and microbiome interventions (e.g., butyrate-mediated regulation of TAM polarization) have demonstrated potential in reshaping the tumor microenvironment and activating immune responses.

Despite significant research progress, challenges remain: the functional compensation mechanisms between tissue-resident and monocyte-derived macrophages, as well as the spatial coding of metabolite gradients on immune responses, remain unclear; technologies such as single-cell multi-omics real-time monitoring and organoid model construction require optimization; issues including targeting precision, large-scale production, and individualized regimens in clinical translation urgently need resolution. In the future, integrating cutting-edge technologies to decode the dynamic regulatory network of macrophages will advance their transition from basic research to clinical applications in cancer and other diseases, laying the foundation for a therapeutic paradigm of “regulating the microenvironment through cells”.

25-HC, 25-Hydroxycholesterol; A

YHL, HHC and SAZ contributed to the study design; YHL and HHC wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript, thank the peer reviewers for their valuable opinions and suggestions, and acknowledge BioRender.com for providing the tools used to create the figures in this manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200755 to YHL), and the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (23JRRA696 to YHL), and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (23YF1430600 to SAZ).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the writing phase of this manuscript, the authors utilized DeepSeek to perform text spell-checking, grammatical corrections, and language refinement. All generated content was personally reviewed and revised by the authors, who assume full responsibility for the ultimately published text. The specific application scope of the artificial intelligence technology has been accurately documented.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.