1 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 200030 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, 350000 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, poses considerable therapeutic challenges due to the varied responses to programmed death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors. Emerging highlight the pivotal role of host-microbiome interactions in modulating antitumor immunity and influencing clinical outcomes. This review examines how the respiratory and gut microbiota contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment through dysbiosis-induced T-cell exhaustion and regulatory cell activation, while certain commensals facilitate dendritic cell-mediated recruitment of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Additionally, this review explores the molecular mechanisms by which microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, influence myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Therapeutically, microbiota-modulation strategies—such as tailored probiotic formulations and precision fecal microbiota transplantation—offer potential to enhance immunotherapy efficacy. This review provides a foundation for microbiome-guided immunotherapy, advocating for biomarker-driven patient stratification and the use of engineered microbial consortia to counteract therapeutic resistance. These findings pave the way for the integration of microbiome science into next-generation precision oncology.

Keywords

- lung neoplasms

- microbiota

- immunotherapy

- programmed cell death 1 receptor

- programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

Lung cancer, the most prevalent cancer globally, is associated with high mortality rates [1]. In 2022, 2.5 million new cases were diagnosed, representing 12.4% of all cancer cases worldwide, with 1.8 million deaths, accounting for 18.7% of cancer-related fatalities [2]. The 5-year survival rate for patients with lung cancer varies by region and stage, but remains below 20% in most countries [3]. While smoking is the leading risk factor, emerging evidence suggests that tobacco control measures could prevent over 1.6 million cases of lung cancer over a 20-year period [4]. Other established risk factors, such as viral infections, family history, genetic mutations, and environmental pollution, are also linked to the incidence of lung cancer [5].

Advances in tumor immunology have revealed the critical role of programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), in immune evasion. Tumor cells express PD-L1 on their surface, which binds to PD-1 receptors on immune cells, inhibiting T-cell responses and allowing tumor cells to escape immune detection and elimination [6]. Additionally, tumor-derived immunosuppressive factors upregulate PD-1 expression on natural killer (NK) cells, impairing their surveillance function [7]. These mechanisms are especially relevant in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which constitutes more than 80% of all lung cancer cases [8, 9]. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are effective treatments for patients with metastatic NSCLC without epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutations [10]. Combining PD-1 inhibitors with adjuvant chemotherapy significantly increases the infiltration of T cells and B cells into the tumor microenvironment [11]. Although some patients experience survival benefits following immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [12, 13], considerable variability in ICI efficacy persists across patients [14]. This variation may be influenced by the host’s gut microbiota [15], with several studies demonstrating that the gut microbiota significantly impacts ICI effectiveness in patients with lung cancer [16, 17, 18]. For instance, patients with NSCLC who respond well to ICIs display distinct gut microbial profiles enriched in Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria [19]. Furthermore, probiotic supplementation has been associated with improved outcomes in patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors [20]. Moreover, advances in gene sequencing technologies have implicated the respiratory microbiota in the carcinogenesis of lung cancer [21], though its effect on ICI responses remains unclear. Nonetheless, existing studies [22, 23] suggest that the respiratory microbiota may play a role in modulating immune signaling within the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Fig. 1).

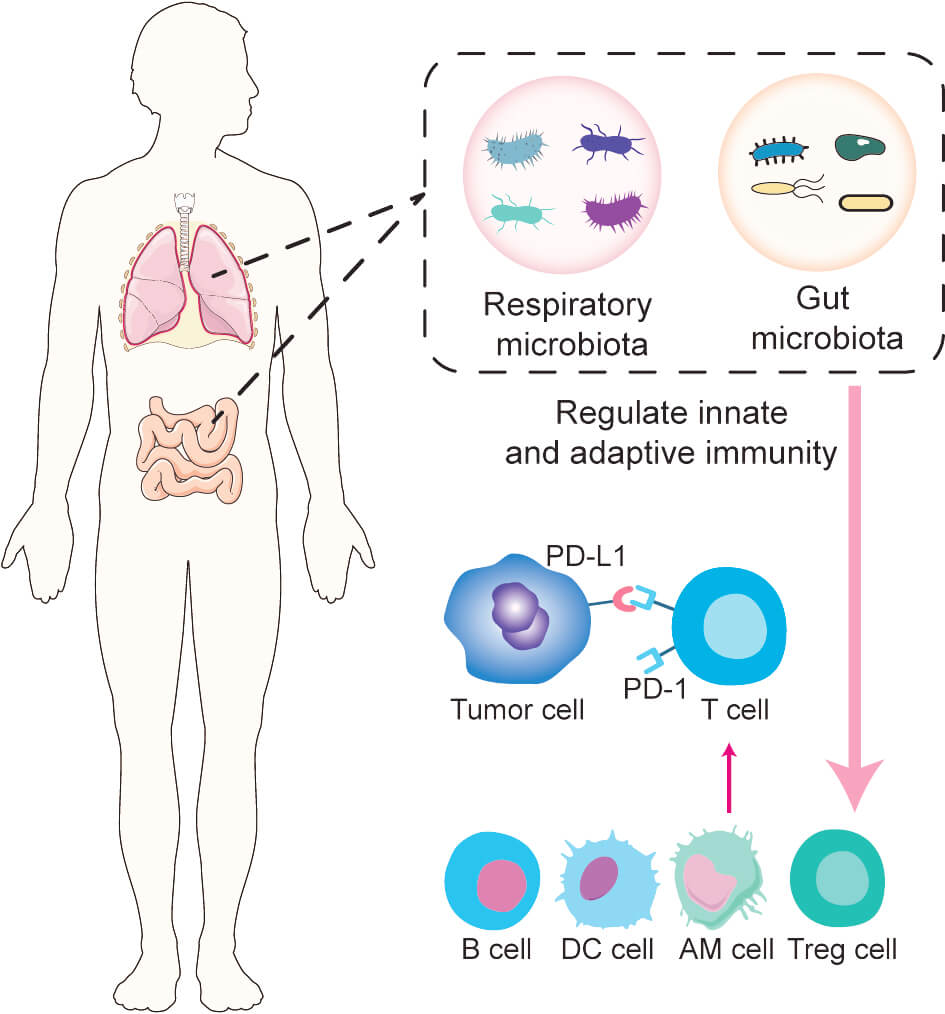

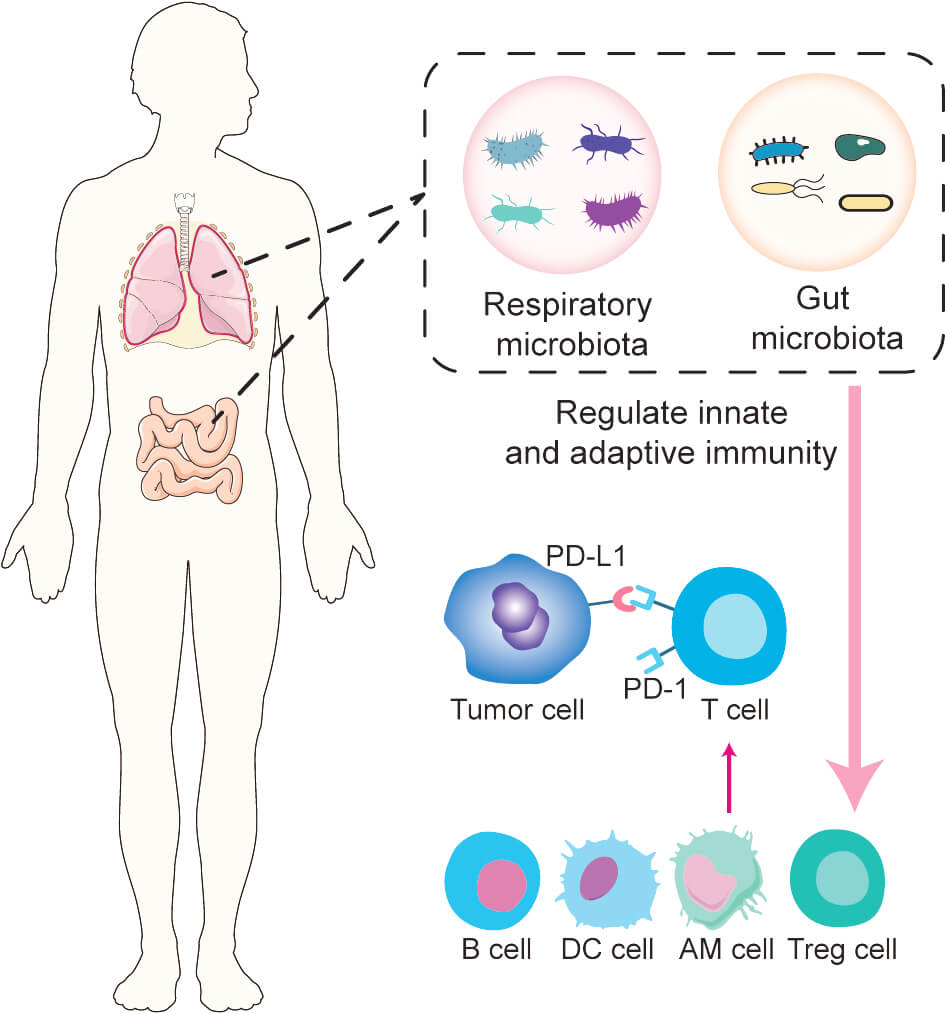

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Impact of gut and respiratory microbiota on immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) response. Alterations in the gut and respiratory microbiota can modulate both innate and adaptive immune systems, influencing the antitumor activity of immune-related cells and thereby affecting ICI efficacy. PD-1, programmed death-1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; AM, alveolar macrophage. This figure was created using Adobe Illustrator.

This review systematically investigates the dual role of the respiratory and gut microbiomes in lung cancer progression, focusing on characteristic changes in microbiota dysbiosis in patients with lung cancer and their dynamic relationship with clinical responses to ICIs. This review further explores how microbial metabolites influence the tumor immune microenvironment, impacting therapeutic outcomes, while assessing microbiota-targeting strategies aimed at enhancing immunotherapy. By synthesizing current knowledge on microbiome‒host‒tumor interactions, this review aims to establish a framework for developing microbiome-based precision immunotherapies.

In healthy individuals, a dynamic equilibrium exists between the lung microbiota

and the host. Disruption of this balance can lead to alterations in microbiota

composition, enabling bacteria to promote tumorigenesis by modulating the immune

microenvironment [24, 25]. A comparison of tumor and nontumor tissues from

patients with lung cancer revealed a significant reduction in

A landmark study comparing the microbiota distribution in bronchial samples from

patients with lung cancer, nontumor tissues, and healthy controls showed that

microbial richness and evenness followed this pattern: nontumor tissues, tumor

tissues, and healthy controls. The relative abundance of Streptococcus

and Neisseria genera decreased progressively, with

Streptococcus showing moderate diagnostic value for lung cancer [28].

This study also demonstrated that in saliva and sputum samples, patients with

lung cancer exhibited significantly higher relative abundances of

Granulicatella, Fastidiosa, and Streptococcus compared

to the control group [28]. Further research identified significant differences in

the salivary microbiota between patients with adenocarcinoma and those with

squamous cell carcinoma, with relative abundances of Capnocytophaga,

Selenomonas, and Veillonella being notably different [29].

Similarly, a study using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples to

investigate the lung microbiota in relation to malignant tumors enrolled 28

participants (20 patients with lung cancer and 8 patients with benign diseases).

Lung microbiota analysis revealed significantly greater relative abundances of

Veillonella and Megasphaera genera in the lung cancer group

compared to the benign disease group [30, 31]. This alteration in microbiota

structure may be closely linked to TME remodeling during carcinogenesis,

suggesting that malignant transformation could induce microbial dysbiosis through

changes in local physicochemical conditions [29]. Another study showed that,

compared to nonmalignant lung tissues, the

The lung microbiota exhibits significant heterogeneity, with varying

compositions across different regions of the lung in the same individual.

Liu et al. [34] investigated the microbiota differences between healthy

lung tissue, lung tissue on the same side as the cancer, and healthy lung tissue

on the opposite side in patients with lung cancer. The study found a stepwise

decrease in

The antitumor immune system is typically capable of identifying and eliminating a small number of cancer cells within the body. However, as cancer progresses, tumor cells may evade immune surveillance [37]. Immune checkpoint inhibition is a major mechanism of tumor immune evasion [38]. Notably, microbial dysbiosis in local tissues can synergize with checkpoint pathways, exacerbating immunosuppression. As summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]), studies have revealed that specific microbiota components modulate antitumor immunity by altering immune cell functions. For instance, Gollwitzer et al. [39] demonstrated that, in the first two weeks after birth, pulmonary bacterial load increased, and the microbial composition shifted from a dominance of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes to an overrepresentation of Bacteroidetes. This shift induced a highly immunosuppressive Helios-Treg cell subset, reducing the body’s response to airborne allergens. The development of this Treg subset relied on the upregulation of PD-L1 expression in dendritic cells. In the absence of microbial colonization or blockade of PD-L1 during this period, susceptibility to allergic reactions persisted into adulthood. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of adult Treg cells into newborn mice reversed this hyperreactive allergic phenotype [39]. Herbst et al. [46] also reported that the absence of the lung microbiota led to immune dysregulation, triggering excessive allergic responses, whereas restoration of the microbiota helped establish an immune-tolerant microenvironment by modulating plasmacytoid dendritic cell and alveolar macrophage (AM) development and function. These studies suggest that the lung utilizes Tregs and macrophages to maintain a low-reactivity state to inhaled antigens, representing a unique immune tolerance mechanism. This tolerant environment may be exploited by metastatic tumor cells, establishing an immune evasion sanctuary [47]. Le Noci et al. [40] observed that antibiotic treatment (vancomycin/neomycin) in mice reduced the bacterial load in lung tissue, which was accompanied by a decrease in Treg cell numbers and an increase in T cell and NK cell activation, significantly reducing melanoma B16 lung metastasis. Further research demonstrated that aerosolized Lactobacillus rhamnosus significantly enhanced the immune response against B16 lung metastasis [40].

| Author | Microbial focus | Sample type | Major findings | Reference |

| Le Noci V et al. | Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | Antibiotic treatment enhances the activity of pulmonary T cells and NK cells, while nebulized Lactobacillus rhamnosus strengthens the immune response against B16 lung metastasis. | [40] |

| Gollwitzer ES et al. | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | The microbiota, initially dominated by Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, gradually shifts toward Bacteroidetes, resulting in the emergence of Treg subsets and subsequent immunosuppression. | [39] |

| Chang ST et al. | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | - | MTB exploits the host’s Th1 immune response and associated cytokines (IFN- |

[41] |

| Zeng W et al. | Veillonella | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | Veillonella inhibits the recruitment of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, reduces the proportion of CD3+ and CD4+ T cells in the peripheral immune microenvironment, thereby promoting immunosuppression. | [42] |

| Segal LN et al. | - | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | A high respiratory microbiota burden impairs the immune response of alveolar macrophages to lipopolysaccharide in the lungs. | [43] |

| Cheng M et al. | - | Lung mononuclear cell | Commensal microbiota sustain |

[44] |

| Ma QY et al. | Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus agalactiae | Resected tumor sample from consenting NSCLC patients | In NSCLC patients, lung cancer tissues show significantly upregulated Th1 and Th17 cell responses to Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus agalactiae, with these responses predominantly enriched in CXCR5+CD4+ T cells. | [45] |

NK, natural killer; MTB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; IFN-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) infection has been shown to contribute

to lung cancer development, primarily through mechanisms involving inflammation,

lung fibrosis, and immunosuppression [48, 49]. In the early stages of MTB

infection, immune responses driven by type 1 helper T (Th1) cells, along with the

secretion of IFN-

These findings underscore the critical role of the lung microbiota in regulating the pulmonary immune environment. Shifts in microbial diversity not only modulate key molecules such as PD-L1 but also influence various populations of innate and adaptive immune cells. Thus, modifying the lung microbiota holds potential for reversing the immunosuppressive state within the pulmonary TME, potentially augmenting antitumor immune responses. However, the precise role of the lung microbiota in lung cancer remains an area for further investigation.

The role of the gut microbiota in cancer immunotherapy has garnered considerable attention [50]. Alterations in the gut microbiota can influence the activity of innate and adaptive immune cells within the TME, thereby modulating the antitumor efficacy of immune cells and affecting the therapeutic outcomes of ICIs (Fig. 2) [51]. Moreover, oral administration of probiotics combined with ICIs has been shown to significantly enhance antitumor efficacy [52], highlighting the critical role of the gut microbiota in tumor immunotherapy. This section reviews key gut microbiota components that impact the effectiveness of immunosuppressive agents in lung cancer treatment.

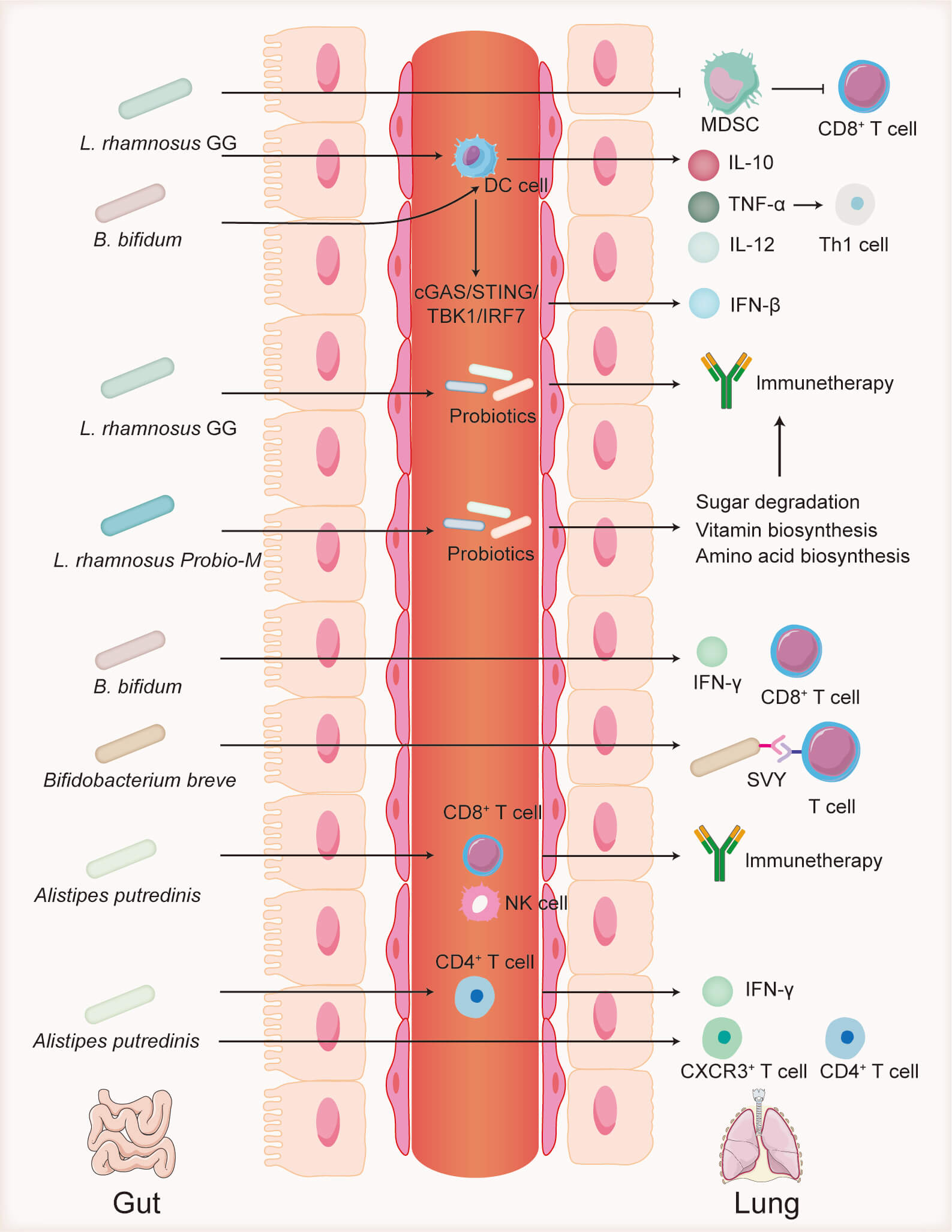

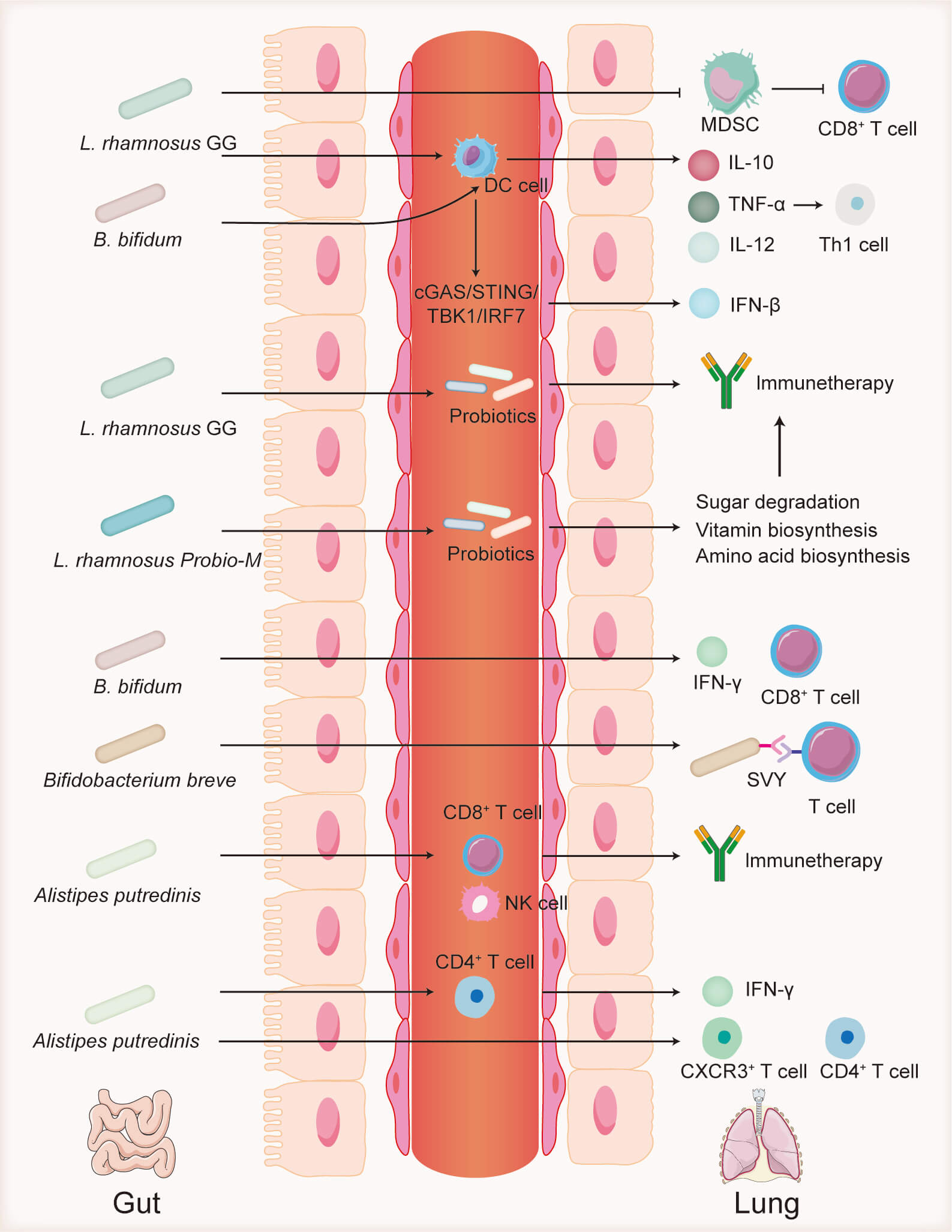

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Role of the gut microbiota in immunotherapy.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG inhibits MDSCs, which suppress

CD8+ T cells. L. rhamnosus GG also alters probiotic abundance,

promotes dendritic cell activation, and enhances cytokine secretion, thereby

boosting Th1 cell responses. Lactobacillus rhamnosus Probio-M modulates

probiotic populations and regulates metabolic pathways related to sugar, vitamin,

and amino acid synthesis. Bifidobacterium bifidum stimulates

IFN-

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, one of the most extensively studied

probiotics, has been shown to inhibit tumor progression [53]. It significantly

increases the expression of dendritic cell maturation markers such as CD40 and

major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II), as well as the secretion of

cytokines like IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-

Bifidobacterium is a common microorganism in the gut microbiota, and

its role in enhancing ICI treatment has been extensively studied. Lee et

al. [62] analyzed fecal samples from 96 patients with NSCLC and 139 healthy

controls, revealing that the abundance of B. bifidum was significantly

higher in responders to ICI treatment than in nonresponders. Moreover, oral

administration of B. bifidum promoted IFN-

Bacteroidetes are a vital group of probiotics in the human gut, with studies indicating their ability to inhibit the onset of various immune-related diseases, including pneumonia [67]. The genus Alistipes, a member of the Bacteroidetes phylum, has been shown to enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy [68]. The abundance of Alistipes in the gut microbiota has been linked to longer PFS in patients with NSCLC undergoing ICI therapy [69]. Alistipes indistinctus is significantly enriched in responders to immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC, thereby enhancing ICI effectiveness [16]. A high abundance of A. indistinctus was strongly correlated with greater clinical benefits in patients with advanced lung cancer (HR = 3.08), suggesting its role in enhancing antitumor responses by modulating the gut immune microenvironment [16]. Similarly, in Chinese patients with NSCLC treated with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab, responders exhibited significantly higher levels of Alistipes putredinis in their gut microbiota [70]. Flow cytometry further revealed a higher frequency of memory CD8+ T cells and NK cells in the peripheral blood of these responders. These findings suggest that Alistipes putredinis may enhance ICI efficacy by indirectly activating both adaptive immunity and innate immunity pathways [70]. In patients with lung cancer treated with PD-1 antagonists, an increased ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes was associated with diarrhea following PD-1 antagonism treatment [71].

Akkermansia muciniphila, a strict anaerobic symbiotic bacterium from

the Verrucomicrobia phylum, participates in host metabolic regulation by

degrading the intestinal mucus layer and enhancing barrier function [72]. It is

reported that [73] the abundance of A. muciniphila in fecal samples from

advanced NSCLC and renal cell carcinoma individuals responsive to PD-1 therapy

was significantly higher than in nonresponders. Similarly, Matson et al.

[51] observed a trend of A. muciniphila enrichment in the gut of

responders within a melanoma patient cohort. Mechanistic studies have shown that

A. muciniphila activates antitumor immunity by stimulating CD4+ T

cells to secrete high levels of interferon-

In the adult respiratory tract, bacterial communities are partitioned along a

clear vertical gradient, with total biomass falling steadily from the upper to

the lower airway. The anterior nares are dominated by the phyla Actinobacteria

and Firmicutes [79]. In the nasopharynx, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria expand in

relative abundance at the expense of Actinobacteria [80], whereas the oropharynx

is chiefly colonized by the phylum Bacteroidetes [80]. In healthy individuals,

the bacterial burden of the lower airway is just 1/100 to 1/10,000 of that in the

upper airway. Here, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria prevail, with

Prevotella, Streptococcus and Veillonella as the most

abundant genera [81]. Lung cancer associated dysbiosis is characterized by

enrichment of Firmicutes and the candidate phylum TM7, alongside depletion of

Proteobacteria [31]. Although Prevotella remains numerically dominant at

the genus level, its relative abundance decreases, while Veillonella

becomes more prevalent [31]. A diverse community structure—as opposed to

domination by a single strain—appears to support the efficacy of ICIs, with

Bacillus playing a particularly important role. By contrast,

Sphingomonas and Sediminibacterium may foster post-ICI tumour

progression through reprogramming of lipid and essential-amino-acid catabolism

[82]. Metabolites released by the microbiota reshape the lower-airway immune

milieu by driving the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines; this

response is accompanied by reduced CD8+ effector T-cell and M1-like macrophage

infiltration in malignant lesions [82]. In a cohort of 56 patients with advanced

NSCLC, responders to anti-PD-1 therapy showed significantly higher relative

abundances of Staphylococcus and Streptomyces in

bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid (BALF;

Defensive cells in the respiratory system continuously monitor the airway

microenvironment to protect the host from pathogenic microbial invasion [86]. A

core function of these cells is to prevent excessive inflammatory responses to

nonpathogenic environmental factors. AMs and dendritic cells maintain the immune

hyporesponsiveness characteristic of the lungs by inducing Treg cell

differentiation [87] and secreting immune-regulatory factors such as

prostaglandin E2, transforming growth factor-

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed on respiratory epithelial cells and antigen-presenting cells, including AMs and dendritic cells, specifically recognize molecular signals from both host and microbial sources [89]. These receptor families include Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors, and C-type lectin receptors [90]. Upon binding to their ligands, these receptors activate immune-related genes that encode inflammatory mediators and type I interferons, initiating both innate and adaptive immune responses [91, 92]. The innate immune system integrates multiple signals to distinguish “danger” from “safe” signals: (1) Symbiotic bacteria, isolated by the mucus barrier, do not directly engage PRRs on epithelial cells, whereas pathogens breach this barrier via virulence factors to trigger immune responses [93, 94]; (2) the spatial distribution of PRRs on the mucosal surface is specific, physically separated from sites of symbiotic bacterial colonization [95]; and (3) immune cells, through cross-talk mechanisms, combine PRR signals with cytokine networks in the microenvironment (e.g., negative regulation by IL-10), dynamically modulating inflammatory response intensity [96]. Through continuous exposure to microbial signals, respiratory immune cells develop unique response patterns. After repeated stimulation by TLR ligands, antigen-presenting cells exhibit a tolerant phenotype, characterized by reduced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [97]. Pulmonary dendritic cells promote B-cell class switching via TLR signaling, differentiating into plasma cells that secrete IgA, thus enhancing mucosal immune tolerance [98]. Additionally, AMs regulate anti-inflammatory mediator synthesis through metabolic reprogramming to maintain tissue homeostasis [99]. These adaptive changes emphasize the critical role of interactions between the lung microbiota and the host immune system in establishing the immune-tolerant microenvironment of the lungs.

The microbiome influences metabolic balance by regulating the host’s detoxification enzyme systems and nutrient absorption pathways [100]. Notably, changes in the composition of specific microbiota are strongly linked to carcinogenic metabolic processes, such as increased aldehyde dehydrogenase activity and enhanced synthesis of deoxycholic acid [101]. Emerging evidence highlights CD36—a fatty acid translocase and PRR—as a key molecular mediator at the host-microbe-cancer interface [102]. This multifunctional transmembrane protein is aberrantly overexpressed in lung cancer [103, 104]. As a pathogen-associated molecular pattern receptor, CD36 activates procarcinogenic inflammatory signals [105]. Additionally, CD36 has been shown to facilitate lipid uptake, promoting lipid oxidative metabolism in tumor-infiltrating myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and enhancing their immunosuppressive effects.

Notably, the microbial metabolite axis intersects with CD36 regulation through

free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2) signaling. Genetic ablation of FFAR2

significantly reduces CD36 expression [106]. The study further suggested that

short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the TME activate FFAR2 receptors on MDSCs,

driving L-arginine consumption in the microenvironment, which, in turn,

accelerates urate-induced lung cancer progression [106]. Tumor models in FFAR2

knockout mice showed a notable decrease in MDSC accumulation and an increase in

CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration within the TME [106]. These findings

indicate that microbial metabolites, particularly SCFAs, may promote immune

suppression by elevating CD36 expression and activating MDSCs. Furthermore,

studies of the lower respiratory tract biofilm microenvironment have revealed

that SCFAs produced by anaerobic bacteria enhance the expression of the

transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) in CD4+ T cells via

epigenetic modifications, promoting Treg cell differentiation and fostering

immune tolerance [107]. SCFAs also suppress IFN-

Recent population-based studies have systematically delineated the tight

relationship between gut microbiome composition and the therapeutic efficacy of

ICIs in patients with NSCLC. A pioneering prospective single-center cohort from

China (n = 34) first showed that higher baseline gut

Compared to healthy individuals, patients with lung cancer exhibit significant

differences in their gut microbiota profiles [114], suggesting that the

microbiota may influence both lung cancer prognosis and treatment efficacy. These

differences imply that the gut microbiota not only potentially impacts cancer

development by altering the immune microenvironment but also plays a pivotal role

in modulating the effectiveness of immunotherapy. For example, a prospective

analysis of 63 patients with advanced NSCLC revealed distinct variations in gut

microbiota composition, functional protein families, and KEGG metabolic pathways

between patients with PFS

In addition, components derived from traditional Chinese medicine, including

monomeric compounds and polysaccharide extracts, have been reported to regulate

the gut microbiota and enhance immune function, thereby playing an important role

in the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. For example, Zengshengping, a

widely used antitumor TCM compound in clinics, is a herbal formulation composed

of Sophora tonkinensis Gagnep, Polygonum bistorta L,

Prunella vulgaris L, Sonchus brachyotus L, Dictamnus

dasycarpus Turcz and Dioscorea bulbifera L [118]. It has been shown to

significantly increase the diversity and richness of the gut microbiota in Lewis

lung cancer model mice, elevating the concentration of secretory immunoglobulin A

in BALF, protecting the intestinal mucosa, and regulating the abundance of

beneficial gut microbiota, ultimately improving lung cancer symptoms [118].

Similarly, Huang et al. [119] demonstrated that ginseng polysaccharides

combined with

These studies highlight the critical role of the gut microbiota in lung cancer immunotherapy, not only by modulating immune responses but also by providing potential predictive biomarkers for clinical outcomes based on microbiota characteristics. Therefore, modulating the gut microbiota may emerge as an important strategy to enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

Accumulating evidence suggests that both the resident lung microbiota and the gut microbiome act as critical dynamic regulators of antitumor immunity in lung cancer. Dysbiosis within the lung microbiota, characterized by reduced alpha diversity, increased relative abundances of genera such as Veillonella and Thermus and spatial heterogeneity even within the same organ, has been closely linked to tumor initiation, progression and variable responses to inhibition of PD-1 and CTLA-4. Conversely, restoration of pulmonary microbial homeostasis can reprogram local antigen presenting cells and regulatory T cell subsets to reverse immune evasion. In the gut, commensal taxa including Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Alistipes, Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii have been shown to promote dendritic cell maturation, Th1 polarization, interferon gamma production and infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, collectively improving tumor control and survival. Mechanistically, the lung and gut microbiota modulate antitumor immunity via pattern recognition receptor signaling, metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic regulation of T cell differentiation.

Although research on the microbiome associated with lung cancer is still in its infancy, emerging evidence shows that it can meaningfully modulate responses to immunotherapy. Future work should use longitudinal multi-omics cohorts to chart the temporal dynamics of pulmonary microbial communities during disease progression and treatment, and to dissect the functional pathways of both dominant and rare taxa so as to identify microbes that enhance the efficacy of ICIs. Synthetic biology and genome editing can then create engineered probiotic strains and test their ability to amplify ICI activity. It is equally important to incorporate the gut microbiome into a personalized intervention framework; by considering each patient’s antibiotic exposure, researchers can design precisely matched FMT protocols and evaluate their efficacy and safety in randomized controlled trials. Ultimately, integrating microbiome profiles with host immune parameters and clinical data into interpretable predictive models should allow real-time risk assessment and intervention planning, thereby advancing the clinical translation of microbiome modulation in lung cancer immunotherapy.

YYX wrote the manuscript. QQL and HW conceived and designed the study. YYX, YXT, HBP and ZJW reviewed the literature and constructed the figures and tables. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This review was funded by the Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 24ZR1464400).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.