1 Clinical Laboratory, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, 266000 Qingdao, Shandong, China

2 Clinical Laboratory and Qingdao Key Laboratory of Immunodiagnosis, Qingdao Hiser Hospital Affiliated of Qingdao University (Qingdao Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), 266000 Qingdao, Shandong, China

3 Medical Research Center, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, 266000 Qingdao, Shandong, China

4 Medical School, Qingdao Huanghai University, 266000 Qingdao, Shandong, China

Abstract

The important immunoregulatory roles of regulatory T cells (Tregs) include fostering tolerance to infections, controlling immune surveillance, and curtailing autoimmunity. Years of research have not only generated abundant knowledge in the field of Treg biology but also enabled the initial application of Tregs in cell therapy. However, most data in this field are obtained from laboratory animals and in vitro experiments. This review provides an updated summary and the latest understanding of Treg-targeting cell therapy. We introduce the unique traits of Tregs, review animal experiments and clinical trials on Treg injections, discuss limitations of Treg applications, and consider future perspectives on Treg-based therapies. Overall, the safety and potential efficacy of Tregs will broaden the scope of cell-based treatments.

Keywords

- immunoregulation

- immunotherapy

- immunodeficiency

- Tregs (regulatory T cells)

- cell therapy

Over the past 30 years, various types of regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been discovered. This particular T-cell subset is well known for its ability to control the immune response and enhance self-tolerance [1]. Three to ten percent of human peripheral CD4+ T cells are Tregs. The phenotypic diversity of Tregs is demonstrated by the presence of numerous markers and their combinations. Forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3), CD25, and CD4 are all expressed by classic Tregs [2, 3]. Therefore, the phenotypic name for these CD4+ Tregs is CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Human Tregs usually have the CD3+CD4+CD25highCD127low FOXP3+ phenotype. Other regulatory molecules, such as Glucocorticoid-Induced TNFR-Related Protein (GITR), lymphocyte activating 3 (Lag-3), glycoprotein A33 (GPA33), Helios, glycoprotein A repetitions predominant (GARP), neuropilin, and T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), are also considered Treg-specific markers [4, 5]. Peripheral-origin Tregs (pTregs) and thymic-origin Tregs (tTregs) are the two subsets of T cells that are distinguished by their sites of origin and development. There are two types of Tregs, known as effector Tregs (eTregs) and central Tregs (cTregs), depending on how they function and differentiate. Within lymphoid tissues, cTregs are relatively dormant. These cells rely on the IL-2 released by conventional T cells (Tconv cells) in the T-cell zones of lymphoid tissues and express the lymphoid homing molecules CD62L and CCR7 (C-C motif chemokine receptor 7). Treg homing to secondary lymphoid organs is facilitated by CD62L as well as CCR7 [6]; eTregs are mostly nonlymphoid Tregs that exhibit increased expression of GITR, ICOS (inducible T-cell costimulator), CD44 and other activation-induced markers with decreased lymphoid homing molecule expression [6]. High levels of IL-10 and the transcription factor BLIMP1 (PR domain 1) are expressed by the majority of Tregs [7]. Tregs are found in various inflammatory sites as well as tissues, and the acquisition of corresponding adhesion molecules along with chemokine receptors that facilitate directional homing is linked to their differentiation. For example, CCR4 guides Treg migration to skin tissues; GPR-15 guides Tregs to the intestines; and LFA-1 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1), CXCR3 (C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3), VLA-4 (integrin alpha4beta1), CCR2, CCR5, CCR6 and CCR8 guide Tregs to areas of inflammation [8].

Tregs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and regulatory B cells (Bregs)

are crucial for preserving tolerance to infections and regulating the immune

response to avoid overactivation [2]. Tregs inhibit proinflammatory cytokine

production and dampen effector T-cell activation and proliferation by secreting

transforming growth factor beta (TGF-

Regardless of how Tregs are classified, only the ability to inhibit immune responses distinguishes Tregs from inflammatory T cells. Reduced Treg function or quantity leads to tolerance loss and increases autoimmune disease risk. In the context of autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation, Tregs inhibit autoimmunization or favor organ transplantation, whereas in cancer, increased Treg levels are linked to tumor growth and a poor prognosis [10].

The barrier tissues and secondary lymphoid organs of the body, such as the lungs, skin, liver and gastrointestinal tract, contain Tregs [11]. When an inflammatory response arises, Tregs penetrate the area and suppress the immune system to reduce the reaction [12]. Tregs can increase immune escape and suppress the antitumor immune response, in addition to reducing autoimmunity [13]. When stimulated by inflammation, Tregs release both CCL4 and CCL3, which are chemokines that guide Treg migration [14].

We recently reported two NK cell subsets, CD38+CD16+ NK cells and CD38+CD16- NK cells, involved in the differentiation of Tregs from CD4+ T cells. CD38+CD16+ NK cells can suppress CD4+ T-cell differentiation into Tregs, and a high proportion of CD38+CD16+ NK cells leads to a low abundance of Tregs, which interrupts immune tolerance in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. In contrast, CD38+CD16- NK cells can promote the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Tregs, and a high proportion of CD38+CD16- NK cells contributes to the abundance of Tregs in tumors to disturb immune surveillance. Treg differentiation is partially dependent on the ratio of CD38+CD16+ NK cells to CD38+CD16- NK cells [15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Other studies also reported the regulatory effect of NK cells on Treg differentiation [20]. Additionally, inhibitory natural killer cell receptors expressed on cytotoxic CD8 T lymphocytes regulate in HIV-1 replication in antiretroviral therapy [21].

Tregs maintain immune homeostasis, which is closely linked to the development of different diseases. Tissue destruction, transplant rejection, graft-versus-host disease, and autoimmune diseases can all be caused by Treg deficiency or dysfunction [22]. However, when a high abundance of Tregs is present in the microenvironment, tumor cells can avoid host immune surveillance [23]. Thus, Tregs may be the basis for the development of novel immunotherapeutic strategies. The following provides an updated summary of Treg-targeting therapies for various diseases.

Many researchers have revealed an increased number of circulating and intratumoral Tregs under tumor conditions, which correlates with impaired CD8+ T-cell function [23]. Tregs disturb immune homeostasis in tumor tissues. Treg reprogramming and T-cell transformation into an immunosuppressive phenotype are caused by the tumor-related inflammatory microenvironment. The interaction between Tregs and tumor cells suppresses immune surveillance and accelerates the growth of tumors, which consequently facilitates tumor progression or immune escape [23]. We recently reported that in vitro, CD4+ T cells are prompted to differentiate into Tregs when tumor cells with high Sirt6 activity and expression are present [24]. Therefore, Tregs are key targets for cancer immunotherapy [25].

Treg depletion strategies may inhibit tumor growth. Interference reprogramming

has been shown to be promising for reducing the number of tumor-associated Tregs

or weakening Treg function in the context of tumor immunotherapy, thereby

improving antitumor immune responses [23]. Although GITR is expressed at low

levels by naive T cells, Tregs show high GITR expression [26]. GITR binding to

its ligand prompts Treg function and inhibits T effector cells [27, 28].

Therefore, strategies for reducing Treg numbers have been developed to target

GITR. The anti-GITR antibody TRX518 have been used in the first human phase I

trial. The antibody increased the T effector cell/Treg ratio and lowered

intratumoral as well as circulating Treg counts [29]. Combining anti-GITR

antibodies with other antitumor antibodies can increase therapeutic efficacy. In

mice with breast tumors grafted with CT26 cells (mouse colon cancer cells), the

combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-GITR antibodies with paclitaxel or cisplatin,

chemotherapeutic medications, markedly suppressed tumor growth. T effector cell

and IFN-

IL-2 is an important cytokine, and CD25 (IL-2R

Inducible costimulator (ICOS) widely participates in anti-inflammatory responses, particularly in ICOS+ Tregs. ICOS expression increases the differentiation and proliferation of Tregs. High levels of ICOS+ Tregs are detected in tumor tissues. Elevated proportions of ICOS+ Tregs are also associated with poor outcomes in most cases [39]. Inducible costimulatory molecule ligand (ICOS-L) is a B7 family member. ICOS-L is a cell-surface protein ligand that binds to receptors on lymphocytes to regulate immune responses. ICOS-L is activated in many cancers to maintain immunosuppressive Tregs. Given the stimulatory role of the ICOS/ICOS-L signaling pathway in tumors, it has become an emerging target in cancer immunotherapy development. ICOS costimulatory receptor agonists alone or in combination with other coinhibitors are expected to improve the response rates to antitumor immunotherapies [40].

OX40 (also known as CD134) is a costimulatory molecule of T cells and a member

of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 4 (TNFRSF4). OX40 plays a

costimulatory role in the process of T-cell activation and mediates the survival

and expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in autoimmune diseases, infectious

diseases and cancers. OX40 can activate the classical NF-

Tregs are a heterogeneous subgroup of immunosuppressive T cells that are not always beneficial for tumor development. The frequency and function of Tregs are associated with a poor prognosis in some cancers but with a good prognosis in others. In some cancers, such as colorectal cancer, Tregs inhibit bacteria-driven inflammation that promotes carcinogenesis and are thus beneficial to the host [43]. Therefore, before the implementation of treatments for Treg depletion, researchers should explore the pathogenesis and developmental stage of tumors.

Recipient immune effector cells identify and eliminate donor tissues and organs, which causes the immune complication known as acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [44]. The clinical use of immunosuppressants is often insufficient, and they are accompanied by obvious side effects. New therapeutic approaches include adoptively transferring ex vivo-expanded Tregs because of their suppressive qualities. In a previous study, mice with GVHD after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation were treated with donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs. In that study, a leukemia bone marrow transplantation model was established by injecting bone marrow cells as well as EL4 leukemia cells from BALB/c mice into C57BL/6 mice. By using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) for positive selection, Tregs were isolated from the bone marrow mononuclear cells of BALB/c mice. Four hours after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, the recipients received injections of ex vivo-expanded Tregs. These Tregs successfully protected recipients from lethal GVHD following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation [45]. Another study investigated the impressive ability of third-party Tregs compared with that of donor-type cells to facilitate allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. In that study, C3H mice were transplanted with the bone marrow of BALB/c-nude mice 2 days after irradiation to deplete T cells. Third-party Tregs expanded from BALB/c or FVB mice effectively enhanced the engraftment of bone marrow allografts. These results suggest that, unlike donor-derived cells, third-party Tregs can be used to prepare large doses of Tregs in advance [46].

To determine whether Treg-based therapy is safe as well as feasible, clinical trials have been carried out. Patients with chronic GVHD have benefited from the adoptive transfer of allogeneic Tregs. The disease status improved and stabilized, all patients were able to tolerate exogenous Tregs, and the quantity of Tregs in circulation increased [47, 48, 49]. A team of researchers investigated Treg grafts in the context of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation by conducting the initial phase of an open-label, single-center phase 2 study. The ratio of CD4+ T cells to Tregs decreased in patients who received Treg grafts. They further reported that Treg grafts containing tacrolimus, a powerful immunosuppressant, were obviously superior to Treg grafts alone for preventing acute GVHD [50]. In another clinical study, three children with severe refractory GVHD were treated with polyclonal amplified Tregs. Adoptive Treg transfer was well tolerated and could control T-cell-mediated allogeneic reactions, as evidenced by significant clinical improvement as well as decreased GVHD activity [51]. The above studies indicate that Treg grafts can effectively prevent acute GVHD. Tregs, as a type of cell therapy, have been widely studied for their ability to treat GVHD and limit immune responses leading to transplant rejection.

People with hematological malignancies benefit from CAR-T-cell therapy.

Hematological malignancies can now be treated clinically with many autologous

CAR-T cells, or auto-CAR-T cells, which have been approved since 2017.

Unfortunately, insufficient amplification and function, poor quality and quantity

of primary T cells, batch-to-batch variations, and lengthy production times limit

the use of autologous CAR-T-cell therapies, and some patients do not respond to

them. Allogeneic CAR-T cells, or allo-CAR-T cells, are considered to have the

potential to overcome this obstacle. Some researchers have attempted to cure

hematological malignancies with allogeneic CAR-T cells. However, preclinical and

clinical results have shown that allogeneic CAR-T cells are unsafe and

ineffective because of allograft rejection along with GVHD [52]. It is

anticipated that Treg cell therapy can improve the efficacy and safety of the

engineered T-cell therapy. Using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

(PBMCs), researchers produced CD19-targeted CAR-Tregs. CD19 CAR-Tregs not only

suppressed B cells but also retained their Treg traits, including high

TGF-

Organ transplantation is an effective method for treating end-stage organ

failure. However, success is limited by the immune response of the recipient to

allogenic tissue. Tregs have recently attracted attention in the context of

transplantation tolerance. Treg-based immunotherapy has been studied as a

potential cell-based model to promote graft survival. One study involved

injecting corneal allograft recipient mice with CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs labeled

with green fluorescent protein (GFP) after their isolation from the draining

lymph nodes of GFP transgenic mice. Six hours after injection, the draining lymph

nodes and the ipsilateral cornea of the recipients contained GFP-expressing

Tregs. These Tregs prevented CD45+ T cells from infiltrating the graft and lymph

nodes and markedly decreased the levels of Th1 cells and mature

antigen-presenting cells. The graft IL-10 and TGF-

One study isolated CD4+CD25+ Tregs via magnetic cell separation techniques. These Tregs were activated via complex skin antigens from the donor and intraperitoneally injected into the host mice. Skin grafts survived longer in mice that received CD4+CD25+ Treg injections than in the control mice [57]. In a humanized mouse allograft model, when a few human Tregs were intradermally injected, inflammation in the skin graft was prevented [58]. In another study, allogeneic human PBMCs were administered intraperitoneally to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) after human skin transplantation. Then, ex vivo-expanded human Tregs were injected intraperitoneally. Skin inflammation, as well as effector T cell infiltration, was suppressed by the injection of human Tregs. Exogenous Tregs immunomodulated local proinflammatory responses, as evidenced by the fact that this injection decreased the number of IL-17-secreting cells and encouraged a relative increase in the number of immunosuppressive Foxp 3+ Tregs in human skin grafts [59].

Allogeneic immunity and unchecked inflammation reduce the survival rate after lung transplantation. Treg cell therapy is considered to improve the outcomes of solid organ transplantation. Before lung transplantation, CD4+CD25high Tregs were grown in vitro in a rat model. Three days after transplantation, the recipient mice were injected with these Tregs. After entering the lung parenchyma, the transplanted Tregs were found to suppress effector T-cell activation without negatively affecting the physiology of the donor lung. This finding raises the possibility of clinical transplantation and indicates that Treg administration has the potential to suppress lung allograft alloimmunity [60].

Graft dysfunction and fibrosis are common after renal transplantation. In three

kidney transplant recipients, autologous Treg therapy was tested for feasibility

and safety in a pilot study. After being isolated from the peripheral blood of

the kidney transplant recipients, Tregs were polyclonally grown ex vivo.

All patients received expanded Tregs. No serious treatment-related adverse events

occurred after the cell injection. Polyclonal Tregs from renal transplant

recipients were shown to suppress graft inflammation [61, 62]. In a phase I/IIa

clinical trial, seven days after kidney transplantation, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs

were infused intravenously at a dose of 0.5, 1.0, or 2.5–3.0

Although some clinical evaluations have proven the safety of Treg therapy, in some clinical trials, Tregs have failed to prevent rejection after solid organ transplantation. An adaptive Treg study (deLTa, NCT02188719) aimed at preventing liver transplantation has not been completed within the research time frame, and several studies (ThRIL, NCT02166177; ARTEMIS, NCT02474199) have either not been officially reported or have not started recruitment (LITTMUS, NCT03654040) [64]. Improving the effectiveness of Treg therapy may require increasing the persistence of Tregs or coordinating the migration of Tregs to inflammatory sites. The doses of Tregs may also be insufficient, resulting in the loss of regulatory function in vivo [65].

Tregs are crucial for preserving tolerance to infections and managing persistent autoimmunity. Treg-based cell therapy has shown promise for treating many autoimmune diseases.

Tregs can be used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [15]. CD4+CD25+ Tregs are defective in people with RA. Many experimental and approved RA drugs may exert effects partly by promoting the function or increasing the quantity of Tregs [66]. Therefore, cell-based therapy involving Tregs may achieve lasting disease remission in RA patients. Similar findings were documented in an animal model of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), a model commonly used for studying RA. One study involved injecting Tregs into DBA/1 mice with CIA after the Tregs were purified and grown in vitro using anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibody-coated beads. In addition to controlling proinflammatory cytokine levels and preventing osteoclastogenesis in vitro as well as in vivo, CD4+CD25+ Tregs alleviated CIA symptoms [67]. To determine whether exogenous Tregs can be used to treat CIA in a rat RA model, we used human Tregs to treat CIA in rats. We isolated human Tregs from the peripheral blood of healthy individuals and expanded them in vitro. CIA rats received injections of Tregs through the tail vein. Human Treg injection dramatically decreased CIA severity, increased the number of endogenous Tregs in the rat spleen and blood, and decreased the number of B cells. In the peripheral blood of the model animals, the Th1/Th2 ratio, IL-6 level, and IL-5 level decreased. Allo-Tregs, even those obtained from cross-species sources, may be used as an immune rejection-free treatment for CIA or RA [68]. Taking supplements of allo-Treg cells may be useful for treating RA.

The maintenance of immunological homeostasis in multiple sclerosis (MS) is

another function of Tregs. Peripheral Tregs (pTregs) are lower and their

immunosuppressive capacity is compromised in patients with MS. In one study,

adoptive cell therapy using induced antigen-specific Tregs was investigated for

its therapeutic efficacy and safety in an animal MS model. To do this, soluble

CD40L was used to activate model animal B cells, which were then used as

antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The study induced antigen-specific Treg

differentiation from naive CD4+ T-cell precursors with the activated B cells.

After being separated using a flow sorter, CD4+CD25highCD127low Tregs were

administered to MS model animals. In addition to lower spinal cord demyelination

and inflammatory infiltration, MS mice presented markedly improved disease

severity [69]. Another group collected CD4+CD25+Foxp3+CD127low Tregs from

remitting-relapsing MS patients and cultured them ex vivo to evaluate

the safety and clinical effectiveness of autologous Tregs. In the pilot study, 14

patients participated, and they were subcutaneously administered ex vivo

Tregs at doses ranging from 2.8 to 4.5

Some researchers injected Tregs into recipient mice with established colitis. When SCID mice were given syngeneic CD25-depleted CD4+ cells, these mice developed chronic colitis, and their colons presented markedly elevated Th1 and Th17 cytokine expression. When Tregs were injected into the mice with established colitis, the colitis considerably improved, and Th17 expression dramatically decreased [71].

Autoimmune diseases such as glomerulonephritis (GN) and lupus erythematosus

often affect the kidneys. The ability of Tregs to treat experimental

anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) GN in mice was examined. After

receiving anti-GBM rabbit serum injection, the animals were immunized with rabbit

IgG to establish experimental GN. Treg-treated model mice presented markedly

reduced CD8+ T-cell and macrophage infiltration along with a sharp decline in

glomerular damage. Significant reductions in renal TNF-

In Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D), the immune system targets and kills the

pancreatic

Autoimmune liver diseases occur when immune cells attack the liver cells of the host. Autologous polyclonal GMP-grade Tregs were isolated and reinfused intravenously into 4 patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Treg infusion showed safety in the patients, and nearly a quarter of infused Tregs homed to liver tissues and locally suppressed tissue-damaging effector T cells. Thus, Tregs have potential as an immune cell-based therapy for autoimmune liver diseases [78].

Clinicians have treated other diseases with Treg-based cell therapies. In acute corneal wound healing, one study investigated the therapeutic impact of Tregs and the possible mechanism underlying local delivery. After a mouse model of corneal alkali burns was established, the model mice received subconjunctival injections of Tregs isolated from homologous mice. The Tregs that were injected moved swiftly to the area of corneal injury. Treg-treated mice presented faster epithelial reformation, less edema, and noticeably less corneal opacity. Treg therapy increased corneal epithelial cell proliferation, prevented inflammatory cell infiltration, and stopped apoptosis in these cells. Subconjunctival injection of Tregs successfully accelerated the healing of corneal wounds by preventing unwarranted inflammation and encouraging epithelial regeneration [79]. One study investigated the treatment of uveitis by the in situ administration of ex vivo-activated polyclonal Tregs. Preactivated polyclonal Tregs were found to be just as effective in suppressing uveitis in mice as antigen-specific Tregs [80].

A study investigated how Tregs affect renal fibrosis using a mouse model of

unilateral ureteral obstruction. The areas of

One team hypothesized that adoptive Treg transfer can alleviate aldosterone-induced hypertension and vascular damage. Tregs were obtained by negative CD4+ T-cell selection and positive CD25+ T-cell selection from among splenocytes collected from male C57BL/6 mice. Fifteen-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were injected with Tregs and aldosterone. Aldosterone increased blood pressure, aortic and renal cortex macrophage infiltration and aortic T-cell infiltration and decreased the number of Tregs in the renal cortex. Adoptive Treg transfer prevented all of the vascular and renal effects induced by aldosterone. Thus, Tregs suppressed aldosterone-mediated vascular injury by mediating innate and adaptive immunity. These results suggest that aldosterone-induced vascular damage can be prevented by adoptive Treg transfer [82].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by neuroinflammation. The adoptive

transfer of A

One study produced induced Tregs (iTregs) by stimulating naive T cells

in vitro for 96 h with 17

Table 1 summarizes Treg cell therapies for many diseases via animal experiments or clinical tests.

| Diseases | Animal experiments | Clinical trial |

| Abortion-prone | performed | |

| Aldosterone-induced hypertension and vascular damage | performed | |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | performed | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | performed | |

| Autoimmune gastritis | performed | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | performed | |

| Autoimmune uveitis | performed | |

| Chronic ischemia | performed | |

| Colitis | performed | |

| Corneal alkali burns | performed | |

| Glomerulonephritis | performed | |

| Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) | performed | |

| Myocarditis | performed | |

| Organ transplantation | performed | performed |

| Rheumatic arthritis (RA) | performed | |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | performed | performed |

| Type 1 diabetes (T1D) | performed | performed |

| Unilateral ureteral obstruction | performed | performed |

Numerous diseases may be treated with Treg therapy. Nevertheless, numerous barriers to therapeutic effects have been noted and are caused mainly by problems in cell preparation, including reduced cell persistence, poor antigen specificity, and problems in generating adequate cell numbers. New techniques for preparing Tregs could improve the efficacy of Treg cell therapies.

In the target tissue, antigen-specific Tregs are needed to accomplish efficient

immune regulation. The use of alloantigen-presenting cells to facilitate cell

expansion is one current method used to produce Tregs that are specific to

alloantigens. In one study, neuroinflammation was suppressed in a mouse model of

AD using A

Another study investigated the efficacy and safety of induced antigen-specific Tregs in an animal MS model. Researchers collected the lymph nodes and spleens of model mice and passed them through a 70-micron filter. MNCs were obtained from the cell mixture using Ficoll gradient centrifugation. B cells were extracted from the MNCs with a B-cell magnetic bead separation kit. The isolated B220+ B cells were resuspended in cell culture medium and mixed with sCD40L and IL-4, along with the MOG35-55 peptide, for 7 to 10 days. CD4+ T cells were also obtained from MNCs using a CD4+ T-cell magnetic bead separation kit. Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic sCD40L-activated B cells at a ratio of 10:1 for 14 days, after which IL-2 and the mouse MOG35–55 peptide were added. After 14 days, the T cells were harvested, and CD4+CD25highCD127low Tregs were isolated using PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD25, APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD127, and PerCP-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 monoclonal antibodies to sort the cells by flow cytometry. After treatment with CD4+CD25highCD127low Tregs, the disease severity score, spinal cord demyelination, and inflammatory infiltration were dramatically reduced in the animal AD model [69].

Recently, researchers have produced donor-specific Tregs using chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) technology; this approach overcomes the drawbacks of Treg enrichment, which is dependent on complicated alloantigen stimulation procedures. One team investigated how donor-specific CAR-Tregs affect immunocompetent mice that received skin transplants. In their experiment, Bl/6 mice received an HLA-A2+Bl/6 skin graft. Tregs expressing anti-HLA-A2-specific CAR were administered to the skin graft model. Skin rejection caused by HLA-A2+ T cells was considerably delayed by the donor-specific CAR-Tregs, which also reduced the levels of donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) and B cells that secrete DSAs. The use of donor-specific CAR-Tregs as an adoptive cell therapy has important implications for transplantation [86].

The problem in generating sufficient cell numbers is a barrier to Treg therapy.

The process used to produce antigen-specific Tregs is too complicated to be

widely used in the clinic. A routine method of ex vivo Treg expansion

has been developed to conduct cell therapy. Using beads coated with anti-CD28 and

anti-CD3 antibodies, researchers grew purified Tregs in vitro to treat

CIA. When they injected expanded Tregs into the mouse arthritis model, Tregs

significantly inhibited CIA development and lowered the serum levels of

TNF-

The adoptive transfer of Tregs includes polyclonal Tregs with nonspecific effects and antigen-specific Tregs with specific effects. Polyclonal Tregs are easily prepared, but their therapeutic effects are low; however, antigen-specific Tregs have strong therapeutic effects, but their preparation is complicated. Several papers have discussed the application and limitations of these two Treg preparations [88]. Recently, a review focused on comparisons of nonspecific and antigen-specific approaches for the use of Tregs, along with their advantages, disadvantages, gaps in development, and future prospects [89].

Despite having a great safety record, polyclonal Tregs have limited

effectiveness. Tregs can now be engineered to have improved immunoregulatory

functions and specificity via gene editing techniques. Steroid receptor

coactivator 3 (SRC-3) is strongly expressed in Tregs and B cells. This gene is

the second-most highly expressed transcription coactivator in Tregs and

downregulates Treg function. Researchers constructed tamoxifen-inducible

Treg-cell-specific SRC-3 knockout (KO) mice by the CRISPR-Cas9 engineering

technique. SRC-3 KO Tregs were highly proliferative and preferentially

infiltrated tumor tissues, generating antitumor immunity by enhancing the

interferon-

One study produced CD19-targeted CAR-Tregs that inhibited B-cell differentiation

as well as IgG antibody production while retaining the characteristics of Tregs,

including high production of TGF-

Tregs display great promise in cell therapy. However, their low number and

differentiation rate limit their further application in the clinic. Everolimus,

which suppresses mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), helps convert more CD4+ T

cells into Tregs. One study used everolimus to increase Treg conversion.

In vitro, these Tregs showed better Foxp3 expression stability in medium

containing TGF-

Rapamycin (Rapa), a clinically used immunosuppressive drug, has been shown to inhibit Th17 cell differentiation but promote Treg generation. Rapa induces metabolic reprogramming in Tregs, affecting their differentiation [94].

The combination of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor AS2863619

(IL-2/TGF-

The preparation method of Treg will be improved, which may stimulate the

proliferation and functional efficiency of Tregs in vivo. The infusion

of IL-2 or anti-IL-2 complexes, or both, represents a therapeutic option to

selectively accentuate or dampen Tregs in the immune response [37]. IL-2/JES6-1

(anti-IL-2 antibody) injection resulted in increased frequencies of natural and

peripheral Tregs in the spleen and draining lymph nodes and elevated IL-10 and

TGF-

Researchers have reported that IL-6 and TNF-

The parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus is known to secrete a molecule

(Hp-TGM) that mimics the ability of TGF-

By breaking down harmful toxins in patient blood, Xuebijing (XBJ), a substance

used in traditional Chinese medicine, increases blood circulation and prevents

blood stasis. The Chinese FDA has authorized XBJ for the treatment of chlorosis.

We injected XBJ into CIA model rats and patients with RA. In the rat model, XBJ

alleviated CIA, and the levels of IL-6, IFN-

Clinical trials have shown the therapeutic value of Tregs. The methods and techniques used for Treg transfer have become very important for improving therapeutic efficacy.

One study revealed that compared with traditional subcutaneous injection and intravenous injection, the local injection at the site of inflammation may require fewer cells. Thus, the local injection of Tregs may suppress inflammation without requiring large-scale Treg expansion ex vivo [58].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are derived from the mesoderm and have gradually become one of the main components of cell therapy because of their multidirectional differentiation potential. At present, many kinds of stem cell therapy products have been approved in several countries to treat various diseases, especially aging-related diseases and degenerative diseases. MSCs can inhibit the proliferation of proinflammatory T lymphocytes, which can cause autoimmune disease and immunological rejection. MSCs have been shown to influence Treg differentiation both in vitro and in vivo. Researchers have collected MSCs and CD4+ T cells from mouse bone marrow and spleens, respectively, and cocultured them with MSCs. In contrast to the increased proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs and the amount of secreted IL-10, MSCs markedly inhibited CD4+ T-cell proliferation, activation and differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells [107]. Another study investigated the possibility of contransplanting autologous bone marrow MSCs and Tregs. Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting, Tregs were isolated from peripheral blood and purified. The team also isolated autologous MSCs in vitro. Yorkshire pigs with chronic myocardial ischemia then underwent the cotransplantation of MSCs and Tregs using a direct intramuscular injection. Many CD25+ cells and CD90+ cells (MSC cell marker) were detected in the myocardium via immunofluorescence staining 6 weeks after the injection, suggesting that the injected Tregs were still present and had survived locally. Factor VIII+ cells were also detected, suggesting an increase in angiogenesis. Cotransplanting Tregs with MSCs represents a novel tactic for the clinical use of therapies based on Tregs [108].

MSC-derived small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) can mimic the effects of MSCs.

sEV treatment can ameliorate arthritis and inhibit synovial hyperplasia in

rheumatic joints, because sEVs can inhibit T lymphocyte proliferation and promote

their apoptosis while decreasing the proportion of Th17 cells and increasing the

number of Tregs. Transcription analysis demonstrated that sEVs decreased

ROR

In vitro, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor AS2863619,

TGF-

A phase I study was conducted by combining polyclonal Tregs and low-dose IL-2 to treat with T1D. The combination not only increased infused and endogenous Tregs, but also elevated active NK cells, mucosal associated invariant T cell and CD8+ T cell populations. The study demonstrates the important implications for a combination of IL-2 and Tregs for Treg therapy [110].

Rapamycin is an effective and specific mTOR inhibitor. Some studies have

investigated the effect of rapamycin (Rapa) on Tregs in vitro. Dendritic

cells (DCs) can initiate the expansion of Tregs and play an indispensable role in

inducing immune tolerance. A study investigated the effect of Rapa combined with

immature dendritic cells (iDCs) on the development of Tregs in vivo.

iDCs from Lewis rats were injected intravenously into Brown Norway rats, and then

Rapa was injected intraperitoneally every day for 7 days. In the Brown Norway

rats treated with allogeneic iDCs and short-term Rapa, the levels of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs and the serum TGF-

Islet transplantation can prolong the life span of patients with T1D and greatly

improve their quality of life, but a tolerant environment is needed to safeguard

transplanted islet tissues. The goal of artificial antigen-presenting cells

(aAPCs) is to enable a tolerogenic microenvironment in vivo and induce

Tregs to extend islet transplant durability. TolAPCs, representing a novel aAPC

that contains poly(lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and PLGA/PBAE, conjugate

with anti-CD28 and anti-CD3 antibodies and contain TGF-

A study evaluated the use of hyaluronic acid and methyl cellulose (HAMC) as an

immunoprotective and injectable hydrogel cell delivery system to improve the

efficacy of Treg-based treatment for experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU). The

combination of Tregs and HAMCs enhanced Treg stability and survival in

proinflammatory environments. Tregs were twice as likely to infiltrate the ocular

inflammatory environment in EAU mice when the intravitreal HAMC delivery system

was used. The Treg-HAMC combination successfully reduced ocular inflammation and

preserved vision in mice with EAU. Due to the delivery system, the number of

inflammatory IL-17+CD4+ T and IFN-

Combination therapy was also performed with biomaterial-based

poly(lactic-glycolic acid) nanoparticles coloaded with Treg growth factor, IL-2

and the

Generally, there is still a lack of effective methods for tracing the differentiation and tissue distribution of Tregs. Microcomputed tomography analyses, histological staining and bioluminescence imaging assays can be employed to evaluate Treg survival and homing efficiency. A study quantified the homing efficiency of Tregs within secondary lymphoid organs using intravital two-photon microscopy. The results showed that, compared with traditional CD4+ T cells, the homing efficiency of Tregs to secondary lymphoid organs was obviously lower, whereas the average survival time of Tregs in lymphoid nodes was 2–3 times greater than that of traditional CD4+ T cells [115].

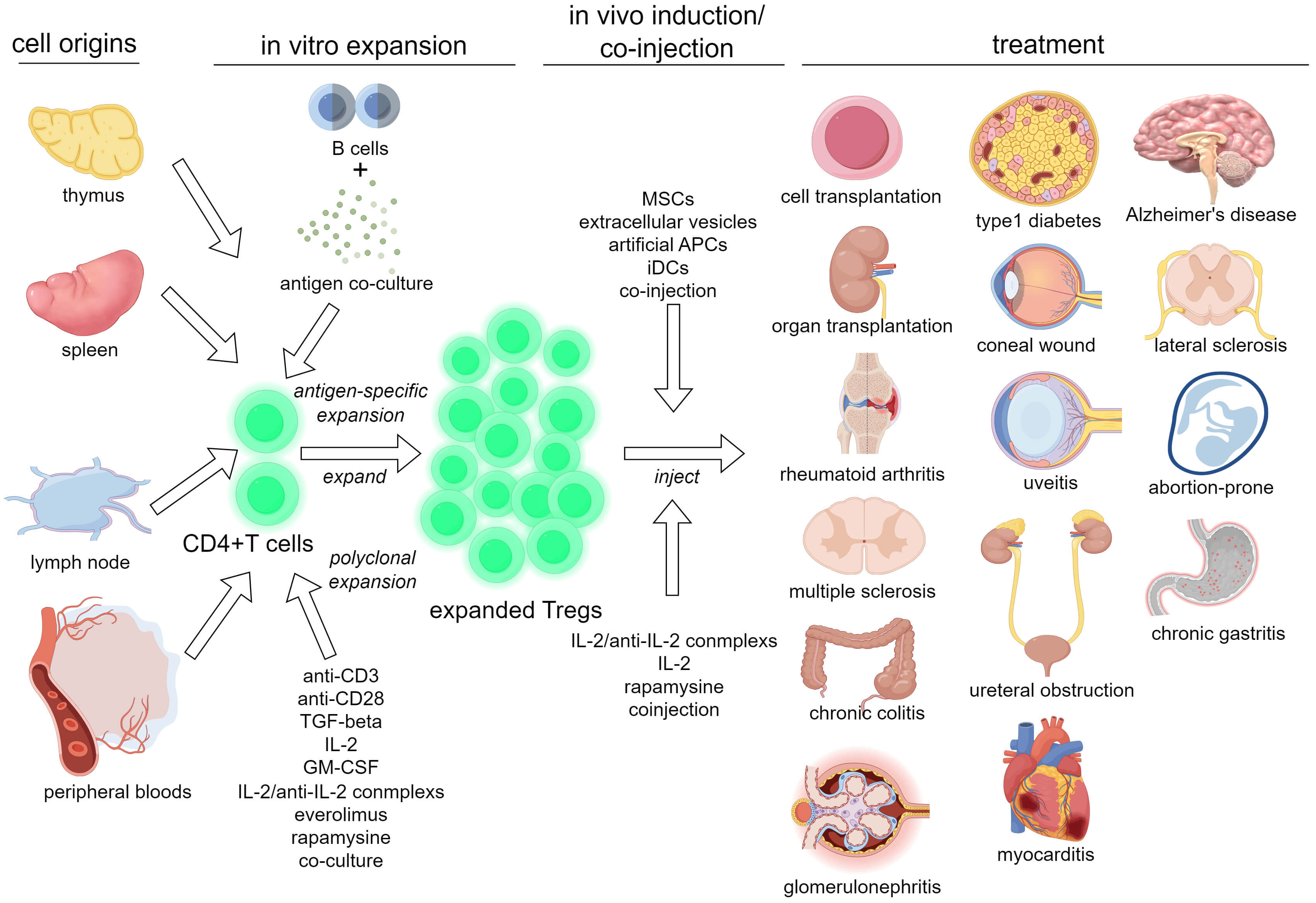

Fig. 1 summarizes the progress of Treg-targeting therapies.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A schema summarizing Treg-targeting therapies. TGF, transforming growth factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; IL, Interleukin; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; APCs, antigen-presenting cells; iDCs, immature dendritic cells. The figure was created using Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com).

We now know more about Treg differentiation, plasticity, and maturity, as well as the relation between their function and phenotype, than we did a few years ago. Although a few clinical achievements have been reported, the clinical utility of Tregs is limited due to an incomplete understanding of their function and mechanism in the immune response. The Treg differentiation pathway allows them to be separated into two types: peripherally induced Tregs (pTregs), which are produced by the extrathymic differentiation of normal T cells at peripheral sites, and thymic-derived Tregs (tTregs). Despite a partial overlap in their regulatory properties, their functional stability, protein expression profiles, and modes of action vary [3]. Another challenge is that we cannot completely define Treg populations and their functions on the basis of CD25 and Foxp3 expression, along with that of other cell surface markers. For example, we recently found that human peripheral blood contains CD8+CD183 (CXCR3)+ T cells and CD8+CD122+ T cells, which can prevent atherosclerosis as Treg-like cells in human and animal models, respectively [116]. In addition, immunotherapy is hampered by the plasticity of Tregs in the inflammatory microenvironment. Contrary to popular belief, Tregs are not always focused on promoting tumor growth; they can occasionally exhibit two functions in the tumor microenvironment. Some studies have even reported the antitumor activity of Tregs [10, 117, 118]. The inhibitory mechanisms of Tregs are not only numerous but also varied and even contradictory, which reflects the intricacy of the system that regulates the immune response [9]. Therefore, understanding the functional diversity of Tregs is essential for improving tumor treatment strategies. Furthermore, when the immunological community attempts to move an efficient approach from mouse research to human research and even clinical research, contradictory results regarding the function of Tregs in various diseases are often reported. Treg plasticity and instability are critical challenges for Treg cell therapy. For example, the proportion of IL-17-producing Tregs (Th17-like cells) is increased in the peripheral blood of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and the level of these cells is closely associated with the clinical index of SLE. These Th17-like Tregs from SLE patients lose their immunosuppression ability and respond to stimulation by autoantigens [119]. Treg plasticity and instability can interrupt the efficiency of Treg cell therapy under pathological and inflammatory conditions.

Single-cell sequencing technology, which has increased in popularity in recent years, is likely a good tool for exploring the functional diversity and plasticity of Tregs in diseases and physiological conditions. Single-cell multiomics integrates various omic technologies at the single-cell level, providing insights into cellular heterogeneity, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic responses. By analyzing the mRNA and protein expression profiles and metabolic features at the single-cell level, distinct subtypes of Tregs and their responses to therapies can be defined. This technique can help researchers find novel surface markers to identify Treg subtypes to accurately treat immunodeficiency, screen reagents or protein factors to increase Treg expansion and antigen specificity, and perform optimization plans to identify the best combination therapy because single-cell sequencing can be used to identify functional cell subsets and regulatory pathways by comparing the expression profiles of the differential cell subtypes. Researchers will gain a better understanding of how Tregs modulate immunoregulation to improve the efficacy of immunotherapy by conducting functional and genetic studies.

Current regulatory approval and clinical trial pipelines seem to restrict the progress of Treg cell therapy, and the management policies of each country are different. Generally, the management policies of various countries are very strict regarding the conduct of clinical trials by scientists and clinical researchers. Some good ideas are difficult to realize, although relative zoological experiments and preclinical experiments have shown good results. In China, as in other countries, Treg clinical trials require a clinical trial registry. Only those hospitals with a stem cell experimental base are qualified to apply for clinical trials of Treg cell therapies. Government departments combine clinical trials of Tregs with clinical trials of stem cells to improve management. In fact, Tregs are immunosuppressive and generally do not cause obvious immune rejection, which means that Treg therapy is much safer than treatments with stem cell therapy or other immune cell therapies, such as T cells and NK cells. Therefore, government departments should not combine studies of Treg therapies, stem cell therapies and other immunotherapies to implement management. Separate policies should be formulated for Treg cell therapy. After all, many diseases are autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases and aging-related diseases. Treg cell therapy is a good way to provide relief from these diseases. Even for CAR-T-cell therapy, adjuvant Treg therapy is a good and effective method to overcome the side effects of allogeneic CAR-T-cell therapy.

Tregs play an important role in maintaining immune homeostasis, and their functional defects are closely related to the development of different diseases. As a result, exogenous Treg supplementation may be used in immunotherapy, particularly to treat autoimmune diseases. Treg therapy also has excellent benefits for organ transplantation and GVHD treatment. To reduce the immune response and restore immune balance, CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs have been shown to be effective in clinical trials. Treg-based therapy will advance clinically at a rapid pace as basic and applied Treg research continues.

KF and XC wrote the manuscript and created the table. JZ provided analysis of data for this work and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.