1 College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA

2 Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA

3 Division of Colon & Rectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA

4 Division of Oncology & Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA

Abstract

The Akt/PKB (protein kinase B) is a major transducer of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling axis, regulating key cellular processes such as growth, proliferation, apoptosis, survival, and migration in both normal and cancer cells. In normal cells, oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins within the Akt pathway exist in equilibrium. However, this equilibrium is disrupted in cancer cells due to activating mutations in oncoproteins and inactivating mutations in tumor suppressor proteins. This dysregulation drives tumor growth and progression, making the Akt pathway an attractive target for cancer therapies. A deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the Akt signaling pathway is crucial for developing novel therapeutic agents targeting Akt and its downstream effectors for cancer treatment. This review discusses the role of Akt in cancer, current Akt-targeted agents, their limitations, and future trends.

Keywords

- Akt

- PI3K

- cancer

- cell survival

- inhibitors

- targeted therapy

Akt, also known as Protein Kinase B (PKB), belongs to the protein kinases A, G, and C (AGC) superfamily of serine/threonine kinases [1]. Akt is one of the key kinases involved in human physiology and disease. Since the discovery of Akt as an oncogene in murine leukemia virus AKT8 and as a homolog of protein kinase C [2, 3, 4] and its subsequent identification as a downstream target of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [5, 6], there has been a significant breakthrough in the mechanism involved in Akt signaling in cancer research [7, 8, 9].

Aberrant activation of Akt is frequently implicated in the pathogenesis of various human cancers, including solid tumors and hematologic malignancies [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. It is aberrantly activated through genetic and epigenetic alterations, such as mutations and/or amplification in key regulatory components like phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic alpha (PIK3CA), phosphatase, tensin homolog (PTEN), and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), Akt itself, and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [9]. Once activated, Akt transmits signals from PTEN, PI3K, and RTK to downstream targets like BCL2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD), glycogen synthase 3 (GSK3), forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factors, and mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) [9, 10]. This cascade of signaling events intersects with other compensatory pathways, allowing cancer cells to bypass normal regulatory mechanisms and promoting tumorigenesis [9, 11].

The Akt pathway drives numerous oncogenic processes, including promoting cell survival, inhibiting apoptosis, enhancing growth and proliferation, facilitating cellular differentiation, and mediating actin cytoskeleton rearrangements [9]. It also plays an integral role in the tumor microenvironment, influencing angiogenesis, recruitment of inflammatory factors, and immune cell infiltration. These oncogenic processes collectively contribute to tumor growth, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [9, 16].

While preclinical studies have well documented the role of Akt hyperactivation in tumor initiation, disease progression, and drug resistance, clinical efforts to target Akt have faced considerable challenges [17, 18]. The complexity of Akt signaling, coupled with tumor heterogeneity, feedback loops within the Akt pathway, and compensatory activation of parallel signaling networks, made it difficult to achieve sustained efficacy of Akt inhibitors in clinical trials [18, 19]. These challenges underscore the urgent need to understand the intricacy of the Akt pathway to develop more effective therapeutic strategies to overcome resistance and improve the clinical outcomes of Akt-targeted therapies.

This review provides an overview of the current understanding of the Akt pathway in cancer, explores the landscape of existing Akt inhibitors against cancer, addresses their limitations, and discusses future trends in developing more effective therapies.

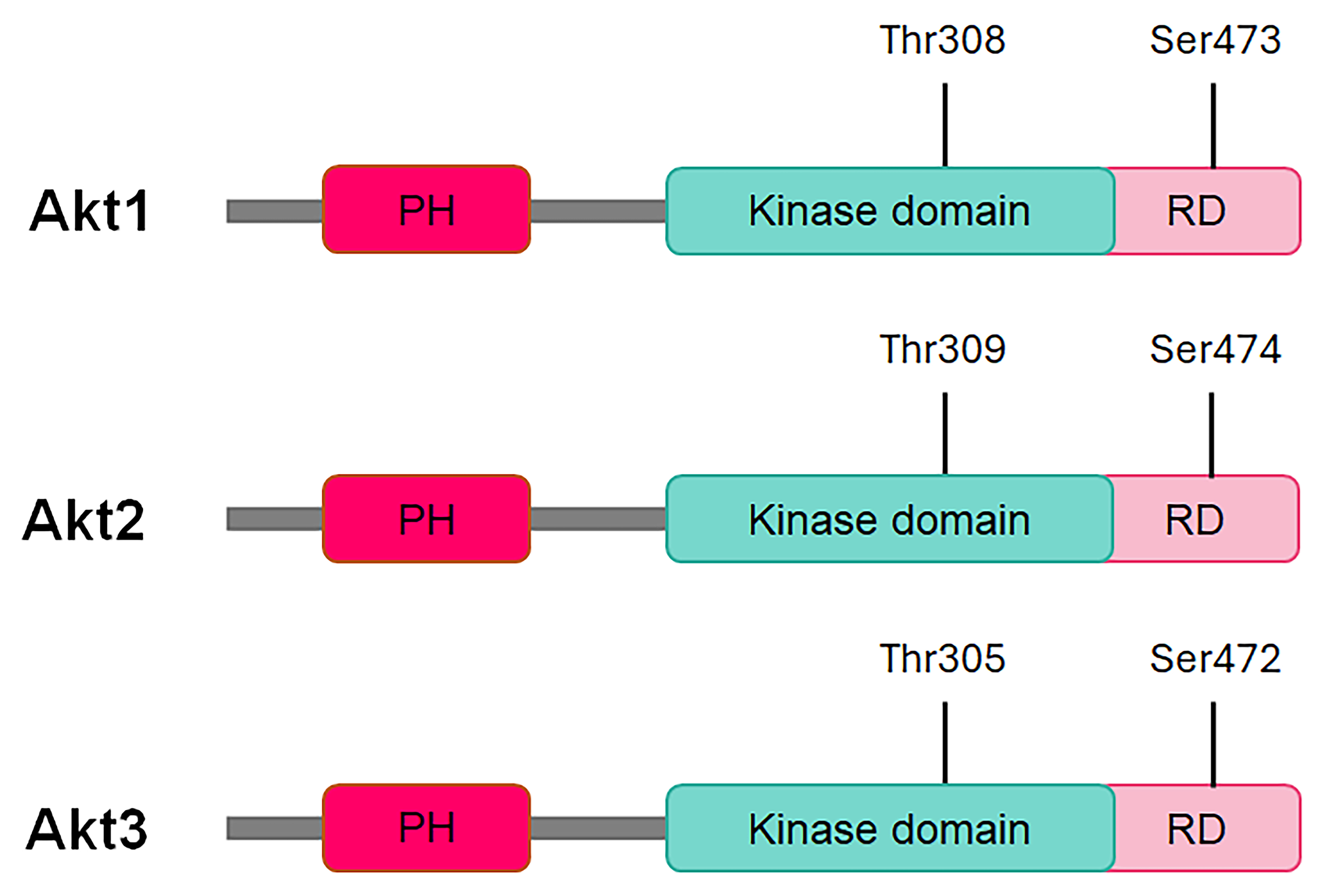

Akt has three isoforms: Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 [1, 9]. Akt1 and Akt2 are broadly expressed, and Akt3 has a limited expression profile and is commonly expressed in brain tissue [20]. All three isoforms have an N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, a central kinase domain (KD), and a C-terminal regulatory region (RR) with a hydrophobic motif [1, 9] (Fig. 1). The PH domain binds 3‑phosphoinositides such as phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) and plays an important role in recruiting Akt to the cell membrane. The central KD with a regulatory threonine residue in its activation loop and the C-terminal RR with a regulatory serine residue are essential for Akt kinase activation [1, 9]. The PH domain also interacts with the KD and autoinhibits Akt in its basal state [9]. While the three Akt isoforms share significant sequence homology among their domains, these isoforms play non-redundant roles in cell signaling: Akt1 regulates cell survival and proliferation, Akt2 is involved in cellular metabolism and cytoskeleton dynamics, and Akt3, alongside Akt1, contributes to cell growth processes [20]. Moreover, isoform knock-out studies in mice revealed distinct physiological roles: Akt1 knock-out mice exhibit developmental defects, Akt2 knock-out mice display defects in glucose metabolism, and Akt3 knock-out mice show abnormalities in brain development [20]. Akt1 promotes cancer cell survival and proliferation and has anti-metastatic effects, while Akt2 promotes cancer cell adhesion, migration, invasion, and metastasis [21].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the conserved domains of Akt kinases. PH, pleckstrin domain; RD, regulatory domain; Thr, threonine; Ser, serine.

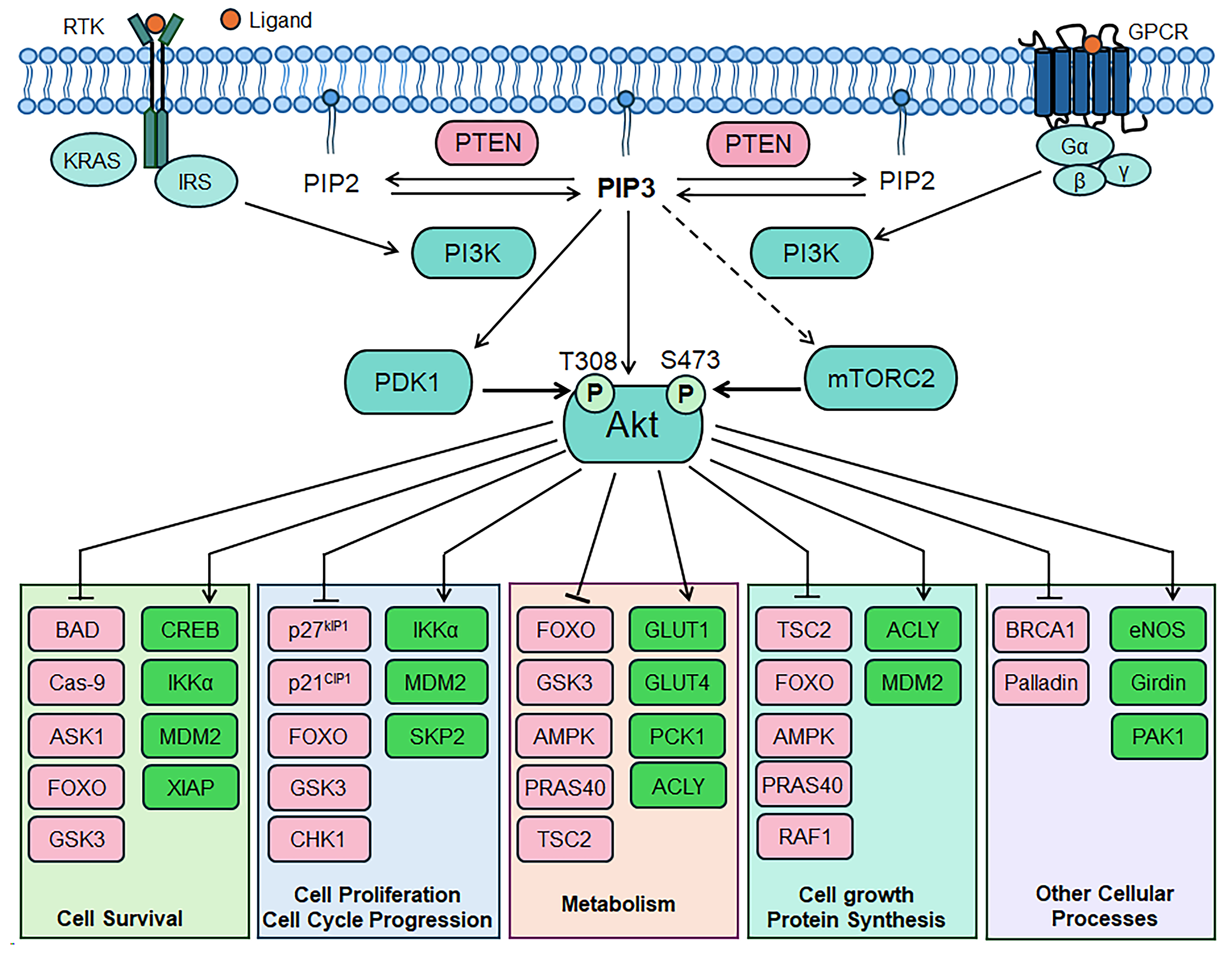

The Akt signaling is tightly regulated in normal cells [1, 9]. As shown in Fig. 2, Akt is activated primarily through PI3K activation, which is triggered by the binding of ligands like insulin, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and other cytokines to RTKs [including the insulin growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), EGF receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)], or G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), cytokines receptors, intracellular tyrosine kinases and intracellular small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) such as rat sarcoma virus (RAS) on the plasma membrane [22]. Once activated, PI3K catalyzes the conversion of PIP2 to PIP3, and the termination of PI3K-PIP3 interaction occurs through the dephosphorylation of PIP3 back to PIP2 by PTEN [9, 23]. The resulting PIP3 at the membrane serves as a docking site for kinases with PH domains, such as Akt and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1), inducing their translocation to the membrane [9, 24].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the Akt signaling cascade. ACLY, ATP-citrate

lyase; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; Akt, protein

kinase B; ASK1, Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; BAD, Bcl2-associated

agonist of cell death; BRCA1, breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein; Cas-9,

caspase-9; CHK1, checkpoint kinase 1; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate

response element binding protein; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FOXO,

forkhead box O; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; GPCR,

G-protein-coupled receptor; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; IKK

Once recruited to the membrane, Akt undergoes further conformational changes through PDK1-mediated phosphorylation at its threonine 308 (Thr308) residue, and this step is sufficient for the activation of Akt [25, 26]. The full activation of Akt is achieved through the mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2)-mediated phosphorylation at its serine 473 (Ser473) residue. Activated Akt then regulates various downstream targets across different cellular compartments, and this regulation influences critical cellular functions, such as cell growth, survival, proliferation, metabolism, glucose uptake, and angiogenesis [27].

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the Akt signaling is integral to regulating diverse

cellular processes. Akt influences cell cycle progression via

phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors

like p27Kip1 and p21Waf1, which act as G1 checkpoint regulators [27].

Akt regulates apoptosis by inhibiting BAD, BCL-2-interacting mediator of cell

death (BIM), caspase 9, and FOXO transcription factors, as well as by

phosphorylating MDM2, facilitating its entry into the nucleus, which leads to p53

degradation [9]. Akt phosphorylates and inhibits the tumor suppressors tuberous

sclerosis complex 1/2 (TSC1/2), which under normal conditions negatively

regulates the mTOR/ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) pathway, thereby activating

mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) [28]. Activated mTORC1 phosphorylates S6K polypeptide 1

(S6K1) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1),

promoting protein synthesis and cellular proliferation by phosphorylation of

ribosomal protein S6 (S6/RPS6) [28]. Akt also regulates cellular metabolism

through modulation of its substrates like GSK3, FOXO, mTOR, and glucose

transporter 1/4 (GLUT1/4); and angiogenesis by regulating vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1

Akt hyperactivation promotes uncontrolled cell growth, evasion of cell death, increased metabolic activity, and alteration in the tumor microenvironment and is critical for cancer progression [9, 10]. Akt activation in human cancer occurs through various mechanisms, including somatic recurrent oncogenic mutation and amplifications in upstream regulators such as PI3K, PDK1, EGF receptor (EGFR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu), or other RTKs [10]. Inactivating mutations in PTEN and PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) also contribute to Akt activation [10]. While mutations in upstream regulators most often drive Akt hyperactivation in human cancers, the three isoforms of Akt also function as oncogenes [9].

Various upstream modulators contribute to the Akt activation in cancer cells. Somatic mutations in the PIK3CA gene lead to the constitutive activation of PI3K and, subsequently, Akt, independent of receptor activation [14]. PIK3CA mutations and/or amplifications are prevalent in cancers such as breast, cervical, colorectal, gastric, lung, and prostate cancers [32]. Overexpression of growth factor receptors, such as EGFR or HER2/neu, can also continuously activate the PI3K-Akt pathway, promoting cell survival and uncontrolled cell growth [32]. Additionally, the activation of oncogenes, such as Ras, can further activate the PI3K-Akt pathway, thereby accelerating tumorigenesis [33]. Ras mutations are prevalent in colorectal, lung, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers, where they maintain Akt activation and contribute to the sustained survival of cancer cells [33]. Furthermore, the deletion or loss-of-function mutation of PTEN, which normally dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2, results in the constitutive activation of Akt [34]. Loss of PTEN is commonly seen in cancers such as breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers [34]. Akt signaling also interacts with other cellular pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Notch signaling, both of which contribute to tumorigenesis and metastasis [32]. Akt can also be constitutively activated in certain hematological cancers due to chromosomal translocations that lead to the activation of upstream tyrosine kinases [11].

While mutations in AKT genes occur less frequently compared to mutations in core Akt regulators like PIK3CA, activating mutations or amplification in the AKT genes have been identified in various solid tumors [35]. Alterations in Akt1 and Akt2 isoforms have been implicated in various cancers, including breast, colorectal, endometrial, gastric, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, glioblastoma, and melanoma [7, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. Among the Akt isoforms, Akt1 is the most mutated isoform. The E17K mutation in the Akt1 PH domain was the first reported somatic oncogenic mutation of any AKT gene [36] and is predominantly found in breast, colorectal, ovarian, and prostate cancers [36, 37, 38, 39]. This mutation exhibits constitutive kinase activation by altering the PH domain of Akt1 and enhancing its localization to the plasma membrane, thereby promoting cancer cell proliferation, survival, and growth [36]. However, the E17K mutation is found to be mutually exclusive with PI3KCA mutation and PTEN loss, suggesting different yet overlapping pathways of oncogenesis [21, 36].

AKT2 was the first AKT gene reported to be recurrently altered in human cancer through gene amplification and overexpression [7, 42]. Alterations in Akt2 were observed in various cancers, including breast, colorectal, ovarian, pancreatic, and hepatocellular cancers [39, 42, 43, 44]. In breast and ovarian cancers, overexpression of Akt2 is associated with increased invasion and metastasis potential and poor prognosis [21, 44]. In pancreatic cancer, over 30% of pancreatic carcinoma samples show more than a threefold increase in Akt2 kinase activity compared to normal pancreatic tissue, highlighting the significance of Akt2 activation in this cancer type [45]. Overexpression of Akt3 is less studied but is impactful in triple-negative breast cancer, ER-negative breast cancer, hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, and melanoma [46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51]. Studies have shown that Akt3 mutations exhibit increased proliferation and pro-carcinogenic effects, but anti-metastatic effects in melanoma cells [51]. Table 1 (Ref. [7, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51]) shows the genetic alterations of Akt isoforms in human malignancies.

| Cancer type | Alterations |

| Breast cancer | AKT1 Mutation [36, 37] |

| AKT2 amplification and/or overexpression [39, 43] | |

| Akt3 overexpression [46] | |

| Brain tumors | Akt Overexpression [38] |

| Colorectal cancer | AKT1 Mutation [36] |

| AKT2 mutation and co-amplification [7] | |

| Endometrial cancer | AKT1 mutation [38] |

| Gastric cancer | AKT1 amplification [40] |

| Glioblastoma | AKT1 mutation [41] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Akt activation [7, 47] |

| Melanoma | AKT1 mutation [38] |

| Akt3 overexpression [50, 51] | |

| Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | AKT1 mutation [38] |

| Ovarian cancer | AKT1 mutation [36] |

| AKT2 amplification and/or overexpression [42, 44] | |

| Akt3 overexpression [48] | |

| Pancreatic cancer | AKT2 amplification and/or overexpression [39, 42] |

| Prostate cancer | AKT1 Mutation [39] |

| Akt3 overexpression [49] | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | Akt overexpression [41] |

| Thyroid cancer | Akt overexpression and overactivation [7] |

The Akt pathway is essential for normal cell survival and growth. The primary biological consequences of Akt hyperactivation, relevant to abnormal cancer cell growth, can be broadly classified into three categories: survival, proliferation, and growth [9]. Akt also had effects on tumor metabolism, angiogenesis, and invasion, contributing to cancer progression and metastasis [9].

Akt has a well-established role in promoting cell survival and resisting

apoptosis—one of the hallmarks of cancer [52, 53]. The cell survival

capability of Akt is critical for tumor growth and contributes to the therapeutic

resistance observed in many cancers. The mechanisms through which Akt modulates

apoptotic and survival pathways are multifactorial, as Akt directly

phosphorylates several components involved in these processes. For example,

activated Akt phosphorylates and inactivates pro-apoptotic proteins such as BAD,

Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX), BIM, caspase-9, GSK3, FOXO, and endothelial

nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), thereby preventing apoptosis through multiple

mechanisms [54, 55]. Additionally, Akt promotes cell survival through

phosphorylation-mediated activation of cell survival factors, including Bcl-2

family members, MDM2, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding

protein (CREB), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

(NF-

Aberrant activation of Akt promotes cell cycle progression and proliferation

primarily through phosphorylation and inhibition of specific cellular substrates

[1, 9]. Akt positively regulates the G1-S phase transition by phosphorylating key

substrates and modulating cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), leading to

unchecked cell proliferation. High Akt activity is often linked to poor prognosis

in various cancers, as it contributes to abnormal cell cycle progression and

tumor growth [57]. Specifically, Akt activation inhibits GSK3 kinase activity,

inducing cell cycle progression via upregulation of cyclin D1 gene expression

[57]. Akt directly phosphorylates cell-cycle inhibitors, p27Kip1 and

p21Waf1, sequesters them in the cytoplasm, and inhibits their binding and

regulation of cyclin/CDK complex, thereby promoting cell cycle progression and

tumor proliferation [7, 58]. Furthermore, Akt has been shown to phosphorylate

S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2), which stabilizes SKP2 and enhances

the degradation of p27Kip1 and p21Waf1, further promoting tumorigenesis

[59]. In addition to its role in cell cycle regulation, Akt is critical in

stimulating protein synthesis, cell growth, and metabolic processes essential for

tumor cell proliferation through its downstream target, mTOR [60, 61]. The

Akt-mediated modulation of key regulatory factors, such as FOXO transcription

factors, MDM2, and inhibitory kappa B kinase

Akt plays a key role in cellular metabolism, particularly by regulating aerobic glycolysis—a hallmark of rapidly proliferating cells [64, 65]. Akt regulates glucose metabolism by increasing glucose uptake into cancer cells, primarily through the translocation of the glucose transporters GLUT1/4 to the membrane, stimulating GLUT1 expression, and activating glycolytic enzymes [65]. Additionally, Akt enhances glucose influx by upregulating ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 5 (ENTPD5), an endoplasmic reticulum enzyme that increases the cellular ADP:ATP ratio. This shift activates glycolytic enzymes that require ADP as a cofactor, resulting in the compensatory increase in aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells [66]. The Akt-induced phosphorylation of GSK3, a key kinase involved in the regulation of glycolytic enzymes, like glycogen synthase, enhances the cancer cell’s ability to metabolize glucose rapidly [11, 67]. The Akt phosphorylation of FOXO transcription factors limits their entry into the nucleus and reduces the tissue-specific metabolic changes [32]. Akt also positively regulates sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1), a master transcriptional regulator of lipid metabolism, which stimulates lipogenesis and blocks gluconeogenesis [65]. This occurs either through direct activation or via phosphorylation-mediated regulation of GSK3 and TORC1, leading to increased lipogenesis in cancer cells [65, 68].

Aberrant activation of Akt leads to an increase in resting diameter and blood

flow in the vascular endothelium [69]. Akt1 is the most predominant Akt isoform

in vascular cells and is critical for VEGF-induced angiogenesis [69].

Constitutive activation of Akt1 leads to abnormal blood vessel formation and

contributes to tumor cell aberration. Akt and VEGF create an autocrine loop

within the cell to regulate angiogenesis, wherein VEGF activates the Akt pathway,

and Akt, in turn, regulates the expression of VEGF and its receptors [70]. Akt

via mTOR signaling also induces HIF-1

Akt signaling enhances cancer cell metastatic potential by promoting processes

like epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and enhancing cancer cell motility

through several distinct mechanisms [16]. Specifically, Akt-mediated

phosphorylation of Twist1 downregulates epithelial marker E-cadherin and

upregulates mesenchymal marker N-cadherin expression. This shift promotes EMT,

invasion, and metastasis via upregulation of transforming TGF

The Akt pathway is frequently altered in human cancers and holds promise for therapeutic interventions [10]. Akt inhibitors are broadly classified as competitive adenosine triphosphate (ATP) inhibitors, allosteric inhibitors, and phosphatidylinositol analogs. Most Akt inhibitors target all three Akt isoforms and are referred to as pan-Akt inhibitors [74]. Competitive ATP inhibitors work by competing with ATP to bind to the KD of Akt and prevent its phosphorylation. Allosteric inhibitors irreversibly bind to non-catalytic sites located in the interdomain region between the KD and the PH domain and stabilize the inactive conformation of Akt. The alkyl-phospholipid compound, on the other hand, binds to the PIP3-cavity within the PH domain and prevents its translocation to the plasma membrane [75]. Several strategies have been explored to inhibit Akt signaling in cancer cells, and Akt inhibitors are currently in different stages of clinical development, either as monotherapies or combination therapies. Tables 2,3 outline select clinical trials of Akt inhibitors in cancer. Representative drugs from each category, especially those evaluated in phase III clinical trials, are discussed below.

| Inhibitor | Target | Mode of action | Tumor | Phase |

| Afuresertib (GSK2110183) | Pan-Akt | ATP-competitive | Breast, cervical, endometrial, esophageal, gastric, gastroesophageal junction, prostate, and ovarian cancers, NSCLC, solid tumors, multiple myeloma, CLL, hematologic malignancies | I/II/III |

| Capivasertib (AZD5363) | Pan-Akt | ATP-competitive | Breast and prostate cancers, solid tumors, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, hematological malignancies | I/II/III |

| Ipatasertib (GDC-0068) | Pan-Akt | ATP-competitive | Breast, head & neck, gastric, prostate, and ovarian cancers, NSCLC, solid tumors | I/II/III |

| Uprosertib (GSK2141795) | Pan-Akt | ATP-competitive | Endometrial cancer, melanoma, myeloma, hematopoietic and lymphoid cell neoplasm, malignant solid neoplasm | I/II |

| GSK690693 | Pan-Akt, PKA, & PKC | ATP-competitive | Hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, lymphoma | I |

| LY2780301 | Pan-Akt & p70S6K | ATP-competitive | Breast cancer, solid tumors, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | I/II |

| MSC2363318A | Akt1/3 & p70S6K | ATP-competitive | Advanced malignancies | I |

| ARQ751 | Pan-Akt | Allosteric | Solid tumors | I |

| BAY1125976 | Akt1/2 | Allosteric | Neoplasms | I |

| Miransertib (ARQ092) | Pan-Akt | Allosteric | Endometrial and ovarian cancers, solid tumors, lymphomas | I/II |

| MK-2206 | Pan-Akt | Allosteric | Breast, colorectal, gall bladder, pancreas, prostate, oral, and ovarian cancers, NSCLC, solid tumors, melanoma, lymphomas | I/II |

| TAS-117 | Pan-Akt | Allosteric | Solid tumors | II |

| Triciribine (PTX-200) | Pan-Akt | Allosteric | Acute leukemia, breast and ovarian cancers, leukemia, hematologic malignancies, metastatic cancer | I/II |

| Perifosine (KRX-0401) | Akt 1/2 | Alkyl-phospholipids | Brain, breast, colorectal, head & neck, pancreatic, prostate, and renal cell cancers, NSCLC, solid tumors, GIST, glioblastoma, mixed glioma, multiple myeloma, sarcoma, CLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma | I/II/III |

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumors; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; p70S6K, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase.

| Trial ID | Conditions | Interventions | Study status |

| NCT number | |||

| ProBio | Metastatic prostate cancer | Experimental: Capivasertib + Docetaxel | Recruiting |

| NCT03903835 | Active Comparator: Control: Standard Care | ||

| CAPItello-290 | Triple-negative breast cancer | Experimental: Capivasertib + Paclitaxel | Active not recruiting |

| NCT03997123 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Paclitaxel | ||

| CAPItello-291 | Locally advanced (inoperable) or metastatic breast cancer | Experimental: Capivasertib + Fulvestrant | Active not recruiting |

| NCT04305496 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Fulvestrant | ||

| CAPItello-292 | Locally advanced (inoperable) or metastatic breast cancer | Experimental: Capivasertib + Fulvestrant + Palbociclib/Ribociclib | Recruiting |

| NCT04862663 | Active Comparator: Fulvestrant + Palbociclib/Ribociclib | ||

| CAPItello-281 | Prostate cancer | Experimental: Capivasertib + Abiraterone | Active not recruiting |

| NCT04493853 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Abiraterone | ||

| CAPItello-280 | Prostate cancer | Experimental: Capivasertib + Docetaxel | Active not recruiting |

| NCT05348577 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Docetaxel | ||

| CAPItrue | Breast cancer | Experimental: Cohort 1 & Cohort 2 with Capivasertib + Fulvestrant | Recruiting |

| NCT06635447 | |||

| CAPItana | Locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer | Capivasertib + Fulvestrant | Recruiting |

| NCT06764186 | Cohort 1: patients without prior fulvestrant | ||

| Cohort 2: patients with prior fulvestrant as the first line & progressed |

|||

| IPATential150 | Metastatic prostate cancer | Experimental: Ipatasertib + Abiraterone | Completed |

| NCT03072238 | Active Comparator: Placebo + Abiraterone | ||

| IPATunity130 | Breast cancer | Experimental: Ipatasertib + Paclitaxel | Completed |

| NCT03337724 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Paclitaxel | ||

| NCT04177108 | Triple-negative breast cancer | Experimental: Cohort 1 | Completed |

| Arm A: Ipatasertib + Atezolizumab + Paclitaxel | |||

| Arm B: Ipatasertib + Placebo + Paclitaxel | |||

| Arm C: Placebo + Placebo + Paclitaxel | |||

| Experimental: Cohort 2 | |||

| Arm A: Ipatasertib + Atezolizumab + Paclitaxel | |||

| Arm B: Placebo + Atezolizumab + Paclitaxel | |||

| FINER | Breast cancer | Experimental: Ipatasertib + Fulvestrant | Active not recruiting |

| NCT04650581 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo | ||

| UmbrellaMAX | Cancer | Experimental: Ipatasertib + Atezolizumab | Recruiting |

| NCT05862285 | Experimental: Tiragolumab + Atezolizumab | ||

| NCT04851613 | Breast cancer | Experimental: Afuresertib + Fulvestrant | Recruiting |

| Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Fulvestrant | |||

| X-PECT | Colorectal cancer | Active Comparator: Perifosine + Capecitabine | Completed |

| NCT01097018 | Placebo Comparator: Placebo + Capecitabine |

Afuresertib (GSK2110183) is an orally available ATP-competitive pan-Akt kinase inhibitor [76]. In preclinical studies, afuresertib demonstrated a potent inhibitory effect on cell proliferation and xenograft tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner, supporting its therapeutic potential in cancer treatment [76]. Afuresertib has been investigated in multiple clinical trials, both in solid tumors, including breast, prostate, and ovarian tumors, and multiple myeloma (Tables 2,3). For instance, a phase I study of afuresertib showed favorable safety, pharmacokinetics, and clinical profile against hematologic malignancies, including multiple myeloma [76]. Furthermore, a phase I/II study of afuresertib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin reported positive results in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients, a difficult-to-treat condition [77]. A phase III trial (NCT04851613) is currently recruiting patients to evaluate the combination of afuresertib and fulvestrant in locally advanced or metastatic hormone receptor-positive (HR+)/HER2-negative (HER2-) breast cancer patients who have failed standard-of-care therapies (Table 3).

Capivasertib (AZD5363) is a potent, selective, ATP-competitive pan-Akt inhibitor [78]. Activating mutations in PIK3CA and AKT1 and loss of PTEN have been found to significantly increase the sensitivity of tumors to capivasertib [79]. Capivasertib monotherapy has shown promise in clinical trials in advanced solid tumor patients, particularly those harboring AKT1-E17K mutation [79]. Capevasertib combination therapy also demonstrated clinically significant responses in Akt-mutated metastatic breast cancer patients [80, 81]. Furthermore, the combination of capivasertib and paclitaxel in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) significantly increases progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to the combination of placebo and paclitaxel (NCT02077569) [82]. The phase III CAPItello-291 trial (NCT04305496) studied the combination of capivasertib and fulvestrant in HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer patients refractory to aromatase inhibitor therapy [83]. The trial reported a statistically significant increase in the median PFS for patients receiving capivasertib and fulvestrant (7.2 months) compared to those receiving fulvestrant alone (3.6 months). Based on these findings, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved capivasertib in 2023 for use in adult patients with HR+/HER2- locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with fulvestrant, marking capivasertib as the first Akt inhibitor to reach the market [84]. Other trials of capivasertib as monotherapy or combination therapies in human cancers are listed in Tables 2,3.

Ipatasertib (GDC-0068) is an ATP-competitive pan-Akt inhibitor with anti-survival and anti-proliferative effects [85]. Ipatasertib has been reported to effectively inhibit tumor growth in cancers with Akt activation due to PTEN loss, PIK3CA mutations/amplifications, or HER2 overexpression [85]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated robust antitumor activity with ipatasertib [85]. A phase I clinical study (NCT01090960) of ipatasertib in patients with solid tumors reported that the drug was well-tolerated [86]. In the phase III IPATential150 trial (NCT03072238), adding ipatasertib to abiraterone and prednisolone significantly increased the radiographic PFS in metastatic and castration-resistant prostate cancer patients with PTEN loss compared to placebo and abiraterone [87]. However, in another phase III trial (IPATunity130; NCT03337724), the combination of ipatasertib and paclitaxel did not improve clinical efficacy in patients with PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN-altered, HR+/HER2- breast cancer [88]. Select trials of ipatasertib in cancers are listed in Tables 2,3.

MK-2206 is an orally available allosteric inhibitor of all Akt isoforms, which prevents the translocation of Akt to the membrane, thereby blocking the activation of its downstream substrates [89]. MK-2206 exhibits higher antiproliferative activity in cancer cell lines that harbor AKT2 amplification, PI3KCA mutations, PTEN loss/mutation, or constitutive activation of RTKs [89]. In preclinical studies, MK-2206 showed significant antitumor activity and has been extensively investigated in numerous phase I and II trials, alone or as combination therapies (Table 2). A phase 1 clinical trial (NCT00670488) of MK-2206 reported a favorable pharmacological activity [90]. However, phase I/II trials of MK-2206 monotherapy and/or combination therapy failed to achieve the desired clinical profile in advanced breast cancer (NCT01277757), colorectal cancer (CRC) (NCT01333475, NCT01333475), and pancreatic cancer (NCT01658943) patients [91, 92, 93, 94].

Perifosine, a first-generation Akt inhibitor, is an orally bioavailable alkyl-phospholipid compound that prevents Akt translocation to the membrane and subsequent phosphorylation [95]. Perifosine showed promise in preclinical models [96] and has been investigated in clinical studies in several different cancers (Tables 2,3). Although perifosine monotherapy showed promising results in pediatric central nervous system tumors and solid tumors [97, 98], it showed poor results in patients with most cancers, including breast cancers, head and neck cancers, pancreatic cancer, and metastatic melanoma [96, 99]. In contrast, perifosine combination regimens have demonstrated success in metastatic CRC, relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, and glioma [96]. Notably, a phase II trial (NCT00398879) investigating perifosine in combination with capecitabine in previously treated metastatic CRC patients showed favorable clinical results compared to the combination of placebo and capecitabine [100]. However, the combination failed to demonstrate an OS survival benefit in refractory advanced CRC in the phase III XPECT trial (NCT01097018) [101].

The Akt signaling pathway plays a central role in promoting tumor cell survival, growth, and metastasis, making it a key target for cancer therapy [10]. Despite promising outcomes in preclinical and early clinical studies, the therapeutic success of Akt inhibitors remains limited [18]. The complex nature of the Akt signaling pathway, along with the vast array of Akt substrates (Fig. 2), often contributes to the limited efficacy of Akt monotherapy and underscores the rationale for combination strategies to target tumors driven by hyperactivated Akt signaling.

Akt isoforms exhibit distinct biological functions in cancer, which contribute

to differential sensitivities to Akt inhibitors. In particular, Akt1 and Akt2

play divergent roles in regulating tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis in

multiple malignancies, and their alterations have been linked to varied

sensitivity of cancer cells to selective Akt inhibitors [21, 102]. For example,

in breast cancer, Akt1 overexpression promotes tumor growth via upregulation of

cyclin D1 and S6, while Akt1 inhibition or Akt2 overexpression enhances tumor

invasion and migration via modulation of focal adhesion kinase 1 (FAK1),

Resistance to Akt-mediated targeted therapy remains a significant challenge.

Cancer cells may evade Akt inhibition through multiple mechanisms, including

crosstalk with the RAS/RAF/MAPK/ERK pathway, where mutations in RAS/RAF may lead

to ERK hyperactivation, conferring resistance [15]. Other pathways, such as

JAK/STAT [19], NOTCH [31], and TGF

Akt signaling also impacts every organ system as a result of the broad cellular and physiological effects, contributing to the on-target toxicities of pan-Akt inhibitors [104]. A notable on-target adverse effect is hyperglycemia, often observed in patients receiving PI3K or Akt inhibitors, stemming from the disruption of Akt2-mediated glucose homeostasis [104]. The mutation landscape within the Akt pathway also strongly influences therapeutic outcomes. Tumors bearing the AKT1-E17K mutation, which promotes constitutive membrane localization of Akt, are hypersensitive to ATP-competitive inhibitors, but not allosteric inhibitors [105, 106]. While tumors harboring genetic alterations such as PIK3CA mutations, PTEN loss, or AKT1-E17K mutations often show increased sensitivity to Akt inhibition [36, 105, 106], intratumoral heterogeneity remains a formidable challenge. Studies have reported that patients receiving genetically matched therapy showed higher objective tumor response rates and improved overall survival compared to those receiving unmatched treatments [107, 108].

Emerging data also highlight the critical role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in modulating responses to Akt-targeted therapies. The PI3K/Akt pathway is essential for T cell function, proliferation, survival, and differentiation; however, its constitutive activation can drive T cells towards terminal differentiation, impairing their cytotoxic action and facilitating immune evasion [109, 110]. In this context, PI3K/Akt inhibitors have been shown to enhance anti-tumor immunity, potentially overcoming resistance to immunotherapies linked to TME-induced T-cell dysfunction [111]. Notably, the incorporation of Akt inhibitors during chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell expansion has been found to promote a less differentiated, memory-like phenotype, leading to improved antitumor activity [112, 113, 114]. In the stromal compartment, the Akt pathway regulates the differentiation of various cell types into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), a key component of the TME. Akt activation in CAFs drives tumor progression by regulating cell proliferation, migration, vasculogenic mimicry, and stemness [115]. Furthermore, CAF-mediated Akt phosphorylation upregulates programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), aiding immune evasion [116]. Akt3-positive CAFs have been shown to exhibit immunosuppressive characteristics and may serve as a potential biomarker for assessing CAF activity [117]. Although Akt inhibitors have been extensively investigated in cancer, maximizing their utility in targeting CAF remains challenging, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of Akt-driven heterogeneity within the TME and its implications for optimizing therapeutic strategies.

Emerging technologies are rapidly transforming the precision medicine landscape for Akt-targeted cancer therapy. Single-cell multi-omics enables high-resolution mapping of transcriptional, epigenetic, and proteomic states at the individual cell level [118], and holds great potential for uncovering cell-specific mechanisms of Akt regulation and identifying therapeutic vulnerabilities. Spatial multi-omics builds upon this by preserving tissue architecture and allowing spatial mapping of RNA, proteins, and metabolites within intact tumor samples, and allows researchers to investigate the organization of molecular and cellular interactions within the TME [119, 120]. Given the central role of the PI3K/Akt pathway in immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming, and stromal cell interactions [109, 110, 121], spatial multi-omics offers a powerful platform for dissecting how Akt signaling heterogeneity across distinct cellular niches within the TME.

At the computational level, AI-driven platforms are accelerating drug discovery by integrating large-scale multi-omics datasets with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modelling. These tools help predict key molecular properties such as cytotoxicity, safety, metabolic stability, and off-target effects, significantly reducing the drug development timeline and cost [122, 123]. AI-guided approaches may be particularly useful for designing isoform-selective Akt inhibitors with improved efficacy and safety.

In vivo clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) screening represents another powerful tool for dissecting the complexities of cancer within its native physiological context [124]. These functional screens can uncover driver genes in cancer [125] as well as key mediators of resistance to cancer immunotherapy [126], thereby identifying novel therapeutic targets. When applied to Akt-targeted therapies, in vivo CRISPR screening can identify actionable escape pathways and guide the development of more durable and effective treatment strategies. In parallel, preclinical models, such as organoids and patient-derived xenograft (PDX), offer physiologically relevant systems for studying Akt pathway modulation, validating inhibitors, and refining biomarker-informed treatment strategies [127]. Meanwhile, plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis offers a minimally invasive strategy for detecting actionable mutations, enabling patient stratification, guiding therapeutic decisions, and monitoring tumor evolution over time [128].

Integrating these cutting-edge methodologies has the potential to revolutionize the landscape of Akt-targeted cancer therapy. However, key challenges remain, particularly integration, standardization, and clinical interpretation of complex datasets, as well as translation across diverse patient populations. Addressing these gaps will be essential to fully realize the promise of precision oncology in targeting the Akt pathway.

The Akt signaling is a crucial regulator of cellular functions and is involved in the initiation and progression of various cancers. Targeting this pathway shows promise for cancer treatment, but challenges like feedback loops, resistance mechanisms, and tumor heterogeneity hinder therapeutic success. Despite substantial progress in targeting Akt, these obstacles still impact patient outcomes in clinical trials. Future research should focus on overcoming these challenges by prioritizing the development of rational Akt-based combination therapies, refining next-generation Akt inhibitors with enhanced isoform selectivity, expanding biomarker-driven patient stratification strategies, and dissecting feedback loops and compensatory pathways contributing to resistance. Addressing these factors could translate Akt-targeted strategies into more precise, durable, and effective cancer therapies.

PDL conceptualized the study design. PDL, RB, LT, and CA conducted the literature search. PDL drafted the original manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial revisions, read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.