1 Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, 6th Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, 100033 Beijing, China

2 College of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine, 8th Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, 100091 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Fibrotic diseases encompass a range of pathological conditions characterized by the abnormal growth of connective tissue, involving various cell types and intricate signaling pathways. Central to the onset and development of fibrosis are macrophages and fibroblasts, whose interactions are a pivotal area of investigation. Macrophages facilitate the activation, growth, and collagen production of fibroblasts, doing so either directly or indirectly through the release of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors. Conversely, fibroblasts boost macrophage activity and intensify local inflammatory responses by secreting cytokines and matrix proteins associated with fibrosis. Throughout the different phases of fibrosis, these two cell types communicate via cytokines and signaling pathways, thereby sustaining the pathological condition. This review emphasizes the interplay between macrophages and fibroblasts and their contributions to fibrosis in the lungs, liver, kidneys, and other organs. Furthermore, it delves into potential therapeutic targets within these interactions, with the aim of shedding light on future clinical research and treatment approaches for fibrotic diseases.

Keywords

- fibrosis

- macrophages

- fibroblasts

- extracellular matrix

- tissue repair

- inflammation

- pulmonary fibrosis

Fibrosis, a multifaceted pathological condition, is fundamentally characterized by the excessive buildup of extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to tissue scarring and, ultimately, compromised organ function [1]. This pathological transformation frequently emerges as the common endpoint in chronic diseases affecting critical organs, including the lungs, liver, and kidneys. Within the intricate web of cellular interactions and signaling pathways, macrophages and fibroblasts stand out as central players in driving the fibrotic process.

Macrophages, known for their remarkable phenotypic adaptability, exert both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects [2]. This versatility directly impacts the activation, proliferation, and ECM production of fibroblasts. Once fibroblasts are activated, a self-perpetuating cycle ensues, marked by the reinforcement of inflammatory and fibrotic signals, making the condition notoriously difficult to reverse. Although significant strides have been made in deciphering the mechanisms of these cells, the intricate interplay between them and their underlying molecular processes remains largely enigmatic.

A wealth of research highlights the distinct roles played by different macrophage polarization states in fibrosis. Similarly, the diverse behaviors of fibroblasts and their interactions with immune cells have been closely linked to disease progression. However, how these cellular dynamics differ across organs and fibrosis stages, and how they might inform therapeutic approaches, continues to be an area of uncertainty and ongoing investigation.

Drawing on current insights into the mechanisms of macrophage–fibroblast interactions in fibrosis, this article delves into how these processes unfold in vital organs such as the lungs, liver, and kidneys. By thoroughly examining the key molecular mechanisms and cellular pathways involved, we aim not only to uncover potential therapeutic targets but also to spark innovative ideas for future clinical interventions. As we navigate the complexities of these interactions, we also grapple with unresolved scientific questions, striving to offer fresh perspectives that could propel the field forward.

Macrophages in other tissues are typically classified into M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotypes. However, with advancements in single-cell sequencing, the M1/M2 paradigm does not fully capture the complexity of pro-fibrotic macrophages. In contrast, monocyte-derived macrophages associated with fibrosis, as observed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and COVID-19-associated Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), have acquired distinct transcriptional profiles [3].

In asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis, monocyte-derived macrophages are localized near fibroblasts within fibrotic areas, and their deletion reduces fibrosis without affecting tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (AMs) [4]. These findings underscore the pivotal role of monocyte-derived macrophages in fibrosis, with their pro-fibrotic properties often overlapping with those of tissue-resident macrophages.

The primary sources of macrophages in the kidneys are monocytes from the bone marrow and resident macrophages within the kidneys. Based on their origin and function, they are generally classified into two categories: one category consists of self-renewing resident macrophages in the kidneys, while the other category comprises macrophages that differentiate after migrating from circulating monocytes to the kidneys [5].

Macrophages in the liver are divided into tissue-resident macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages. However, the resident macrophages in the liver have been given a new name: Kupffer cells [6].

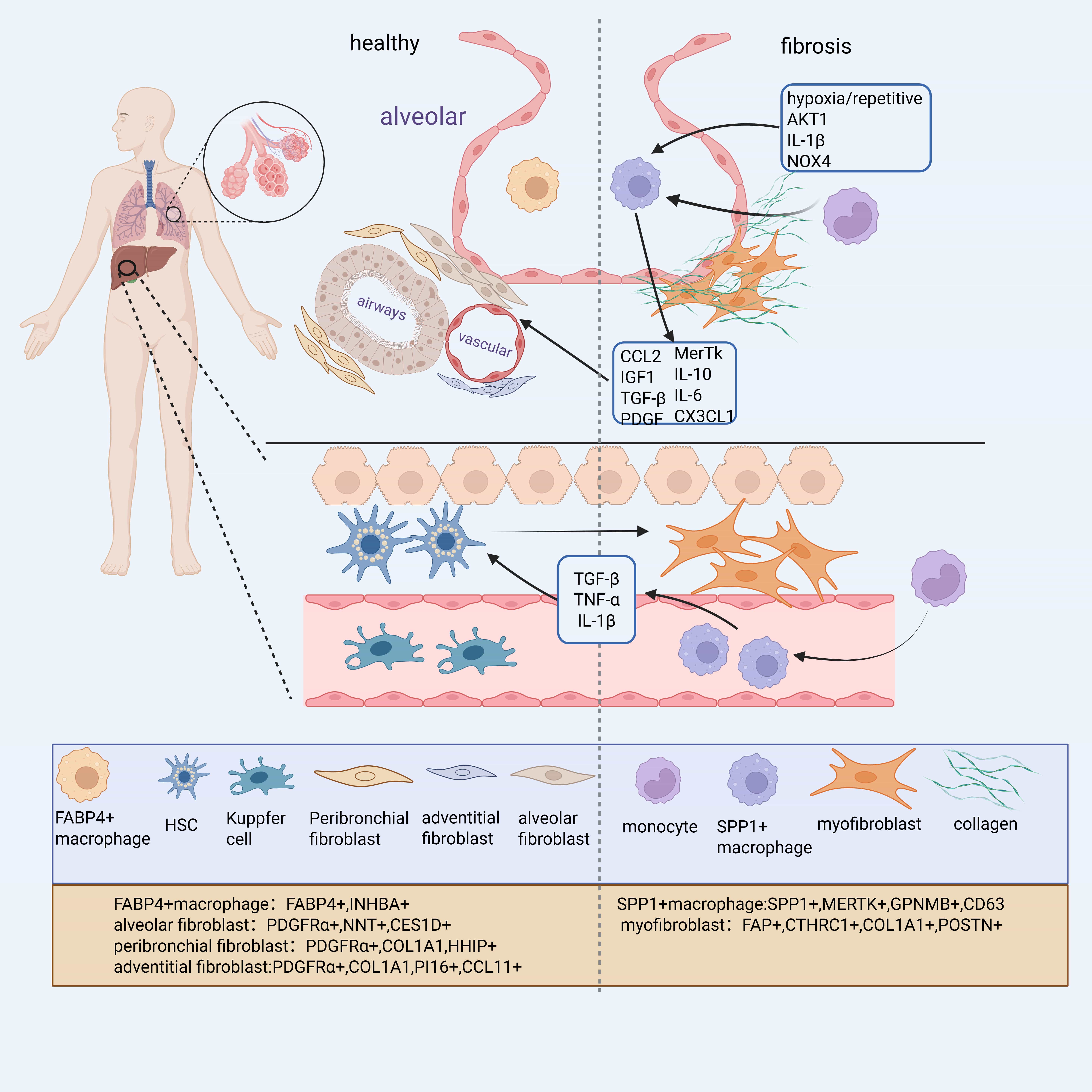

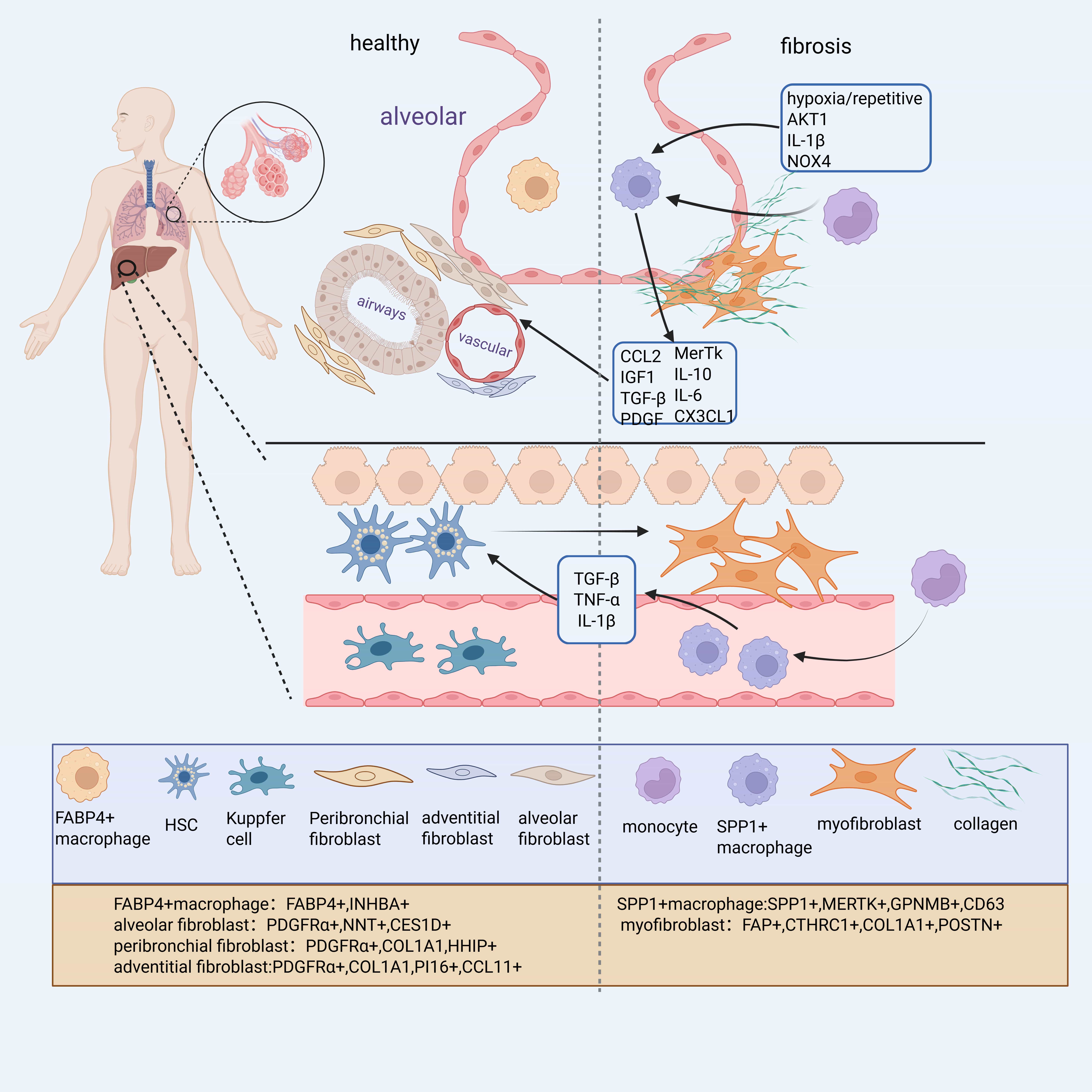

With the advancement of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), numerous macrophage subpopulations associated with fibrosis have been identified across organs. In IPF, scRNA-seq of lung tissues revealed several distinct macrophage subsets, including Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1+), Ficolin 1 (FCN1+), and Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 (FABP4+) macrophages. Among these, FABP4+ macrophages, predominantly found in healthy lungs, are inferred to represent Alveolar Macrophages (AMs), while SPP1+ macrophages, co-expressing MAF BZIP Transcription Factor B (MAFB), CD163 Molecule (CD163), and Legumain (LGMN), likely derive from monocytes [7].

A similar classification was proposed in the study of Morse et al. [8], which identified three macrophage subsets in normal and IPF lungs: monocyte-like cells, FABP4hi/Inhibin Subunit Beta A (INHBA)+ macrophages, and SPP1hi/MER ProtoOncogene, Tyrosine Kinase (MERTK)+ macrophages. Notably, SPPhi macrophages exhibit limited proliferation in healthy lungs but strongly proliferate in IPF lungs, in contrast to the declining proliferative capacity of FABP4hi macrophages [8].

Importantly, SPP1+ macrophages appear to represent a conserved macrophages population across multiple fibrotic disorders. They are consistently expanded in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), heart failure, and other fibrotic conditions [9] (Fig. 1). In liver fibrosis, a related subpopulation known as Scar-Associated Macrophages (SAMs)—characterized by CD9+ Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2+) markers—also highly expresses SPP1, along with Glycoprotein Non-Metastatic Melanoma Protein B (GPNMB), FABP5, and CD63 [10, 11]. Similarly, in the Perivascular Adipose Tissue (PVAT) of patients with coronary atherosclerosis, elevated levels of SPP1+ macrophages were associated with greater fibrosis severity and higher coronary stenosis grades [12]. Together, these findings suggest that SPP1+ macrophages constitute a core fibrotic macrophage program conserved across organs, while other subtypes such as FABP4+ macrophages may play tissue-specific roles. However, the post-traumatic repair process does not solely involve a pro-fibrotic process but also includes tissue repair processes. Additionally, SPP1+ cells exist at different stages of maturation and exhibit diverse expression profiles, suggesting they may possess distinct functional states, potentially functioning as “remodeling” macrophages with dual roles in ECM regulation and repair [13]. While these findings highlight a conserved role for SPP1+ macrophages across various fibrotic diseases, it is important to interpret single-cell transcriptomic classifications with caution. Technical limitations such as batch effects, low RNA capture efficiency, and underrepresentation of rare cell types may affect the resolution and interpretation of macrophage subtypes, potentially overestimating their transcriptional discreteness [14].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Distribution and gene expression of different cell subtypes in healthy or fibrotic lung tissues. Myofibroblasts are the primary collagen-producing cells in the fibrosis process, primarily derived from alveolar fibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells. Monocyte-derived Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1)+ macrophages, influenced by hypoxia, injury, and other factors, produce factors such as C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (CCL2) and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), which positively regulate the differentiation of alveolar fibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells into myofibroblasts. Figure generated using BioRender software. COL1A1, Collagen Type I Alpha 1; FABP, Fatty Acid Binding Protein. Created with BioRender.com.

Fibrosis is a chronic inflammatory response induced by relatively severe or repetitive tissue damage, where ECM components continuously accumulate, leading to structural destruction and fibrosis of the tissue [15]. Macrophages play a pivotal role in initiating and sustaining inflammation and are key participants in the fibrotic process. Single-cell sequencing of human and mouse tissues has identified diverse macrophage subtypes involved in tissue inflammation and fibrosis, with distinct regulatory roles in these processes. In a 2005 study on liver injury and repair by Duffield et al. [16], macrophage depletion during the progression of hepatic fibrosis resulted in reduced scar formation and fewer myofibroblasts. Conversely, macrophage depletion during recovery impaired matrix degradation [16]. This suggests that macrophages not only promote fibrotic tissue repair but also contribute to post-injury tissue recovery by phagocytosing degraded matrix. These roles may be carried out by distinct macrophage subpopulations. Further research has revealed that certain macrophage subpopulations are more effective at triggering fibrosis, depending on their spatial localization and their capacity to activate other fibrosis-associated cells [4, 17].

Modulation of macrophages alone can significantly influence fibrotic outcomes,

with diverse mechanisms observed across organ systems. In the liver,

pharmacologic inhibition of macrophages has shown therapeutic potential. For

instance, blocking dopamine receptor D2 signaling in macrophages—but not in

hepatocytes—suppresses transcriptional co-activator activity and favors liver

regeneration over fibrosis [18]. Additionally, the neurotrophic factor MANF,

expressed in myeloid cells, interacts with S100A8 to disrupt its binding with A9,

thereby inhibiting the TLR4–NF

In the kidney, hematopoietic cell kinase (HCK) drives macrophage polarization

toward pro-inflammatory, proliferative, and migratory phenotypes via autophagy,

thereby exacerbating fibrosis [21]. In contrast, the zinc-finger transcription

factor KLF4 serves as a negative regulator of macrophage-mediated inflammation,

protecting against TNF

In the skin, Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling enhances macrophage oxidative phosphorylation and cytophagocytic activity, promoting their polarization toward a pro-fibrotic phenotype and driving scar formation [25]. Beyond organ-specific mechanisms, macrophages have also been shown to directly produce ECM proteins. A 2020 zebrafish study demonstrated that macrophages can contribute to scar formation by expressing and depositing collagen both autonomously and in a cell-naïve manner. However, macrophage-derived collagen may differ in composition and organization compared to that of canonical myofibroblasts [26].

Because the original M1/M2 macrophage typing does not fully describe

pro-fibrotic macrophage subtypes, there has been a gradual increase in studies on

the regulation of SPP1+ macrophages alone. For instance, in hepatic

fibrosis, SAMs are regulated by cytokines such as Granulocyte–Macrophage

Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF), Interleukin 17A (IL-17A), and Transforming

Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-

Fibroblasts are primarily derived from mesenchymal cells. Under normal

physiological conditions, fibroblasts are a key cell type in connective tissues,

and their main functions include the synthesis and secretion of collagen and

other fibrous proteins as well as participation in wound healing and tissue

repair processes. During fibrosis, fibroblasts not only increase in number, but

their behavior also changes from supporting and repairing to promotion of

hyperfibrosis and tissue sclerosis, a shift that is usually caused by a chronic

inflammatory response in which pro-inflammatory factors released by immune cells

activate and alter fibroblast function. These cells are not only involved in the

inflammatory phase but also contribute significantly to the formation of type I

collagen in the later stages of tissue remodeling [31]. Notably, type I collagen

is the main component of scar tissue. In their review, Plikus et al.

[32] summarized various fibroblast subpopulations in different tissues, including

alveolar fibroblasts (PDGFR

As with macrophages, certain fibroblast cells are more closely involved in the fibrotic process than others. In addition to fibroblasts, a variety of other cells can differentiate into myofibroblasts after acute tissue injury [37]. Fibroblasts contributing to fibrosis originate from diverse sources, and their activation represents a dynamic and context-dependent process. While Hhip+ lipofibroblasts have been identified as a fibroblast subtype enriched in regenerative regions and associated with anti-fibrotic signaling pathways in both mouse and human lungs [38], this trajectory represents only one of several potential differentiation pathways. However, to date, SCUBE2+ fibroblasts have primarily been characterized in mouse models, and their presence and relevance in human fibrotic diseases remain to be confirmed by future studies. Other resident cell populations, such as lipid fibroblasts, have been shown to be capable of mutual conversion with myofibroblasts during the progression and regression of fibrosis [39]. Adventitial fibroblasts are activated and migrate to the intimal region following arterial injury, differentiating into myofibroblasts and participating in ECM deposition and pathological remodeling [40]. This includes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the process by which endothelial cells transform into mesenchymal fibroblasts, which is closely associated with wound healing and organ fibrosis [41]. However, EMT appears to play a more significant role in the kidney, while its role in other organs remains controversial, with complex mechanisms that require further validation. These cells have been shown to contribute to the myofibroblast pool depending on the type of injury, anatomical context, and species.

Notably, single-cell lineage tracing and transcriptomic analyses have identified transitional fibroblast states (e.g., SFRP1+ or Cthrc1low) that precede full myofibroblastic differentiation and may retain partial lipogenic signatures. While these findings suggest potential plasticity, definitive in vivo evidence for their reversion to quiescence in established fibrosis remains limited. In particular, whether such transitions occur under pathological conditions or only in self-resolving models (e.g., young mice) is still under investigation. Therefore, fibroblast activation is better conceptualized as a context-dependent continuum, shaped by niche-derived cues, rather than a strictly linear or fully reversible process. However, this may also suggest that fibroblasts are not the end point of a single trajectory, but rather the result of the convergence of multiple input factors (developmental origin, spatial location, and signal exposure), and that functional heterogeneity exists even within subpopulations defined by markers.

Fibroblast activation plays a central role in tissue remodeling across multiple organs and is regulated by diverse, context-dependent mechanisms. In the heart, Ambra1 limits fibrosis by blocking the uptake of extracellular vesicles from cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts [42]. Additionally, Platelet-Derived Growth Factor AB (PDGF-AB) facilitates fibroblast migration and scar maturation without inducing proliferation, thus supporting functional repair [43].

Several pro-fibrotic pathways are shared across organs. Notably,

Wnt/

In the lung, regulatory factors exert opposing roles: Platelet Endothelial Aggregation Receptor 1 (PEAR1) suppresses fibrogenic signaling via protein phosphatase 1, whereas CD147 promotes SARS-CoV-2-induced fibroblast activation [49, 50]. CD148, conversely, inhibits NF-kappaB-mediated necrotic gene expression, reducing fibrosis [51].

Epigenetic and transcriptional control also shape fibroblast behavior. In skin and epidural tissues, Histone Deacetylase 5 (HDAC5) silences Smad7 through Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2A (MEF2A), and Jun Proto-Oncogene, AP-1 Transcription Factor Subunit (JUN) activates CD36, both contributing to excessive collagen deposition and scar formation [52, 53]. In contrast, lncRNA-COX2 downregulates Early Growth Response 1 (EGR1), limiting fibroblast activation and epidural fibrosis [54], while p53 deletion causes fibroblast overproliferation and ECM accumulation, contributing to pathological fibrosis [55].

Across various tissues, fibroblast activation protein (FAP) serves as a consistent marker of activated fibroblasts. In the intestines and kidneys, FAP+ fibroblasts are key ECM producers [56, 57]. In both the heart and liver, FAP+ fibroblasts contribute to fibrosis, and targeting FAP—via genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition—has been shown to attenuate fibrosis, reduce inflammation, and promote tissue repair [45, 58]. These findings underscore the organ-specific yet overlapping pathways that govern fibroblast activation in fibrotic diseases.

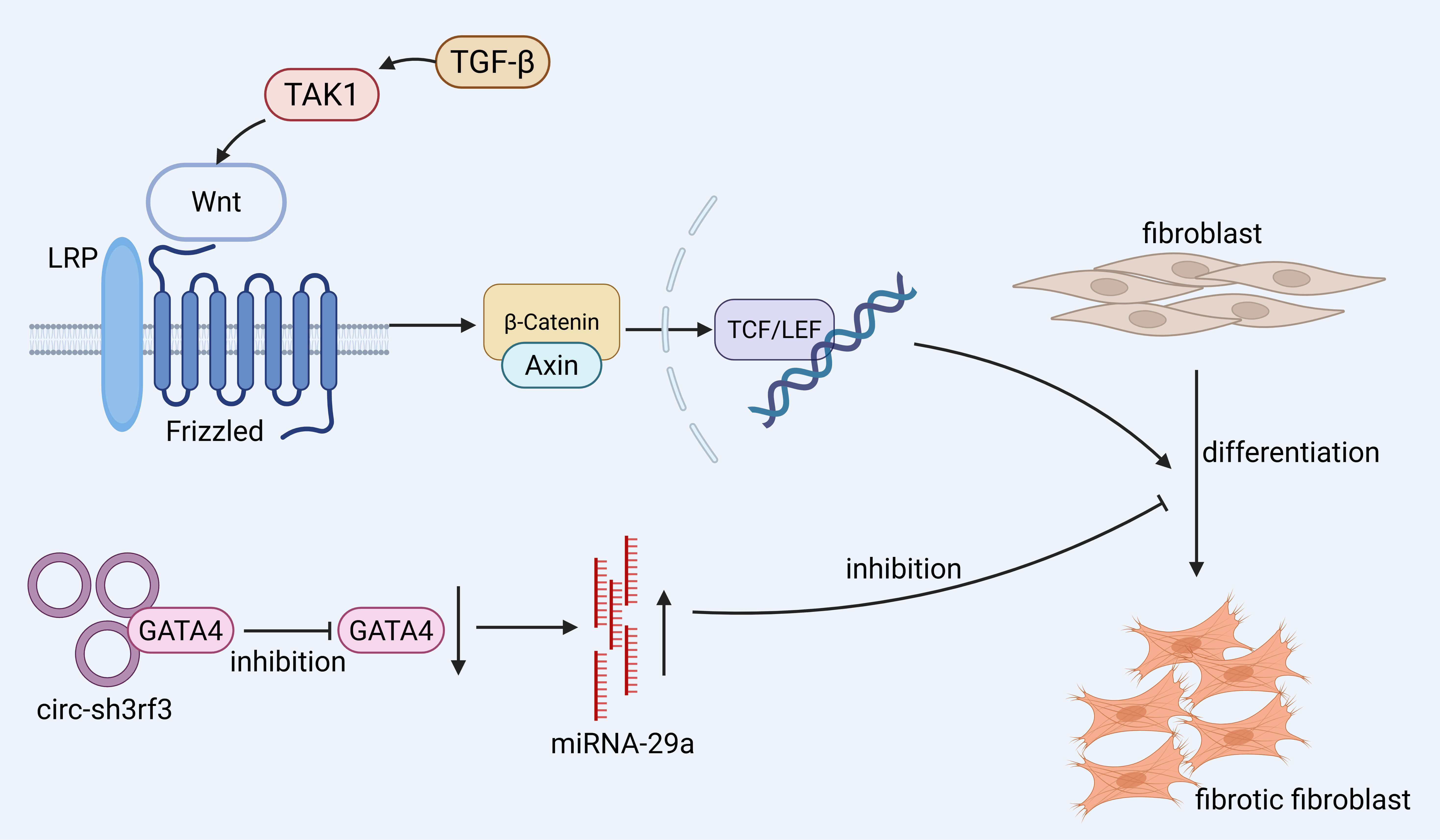

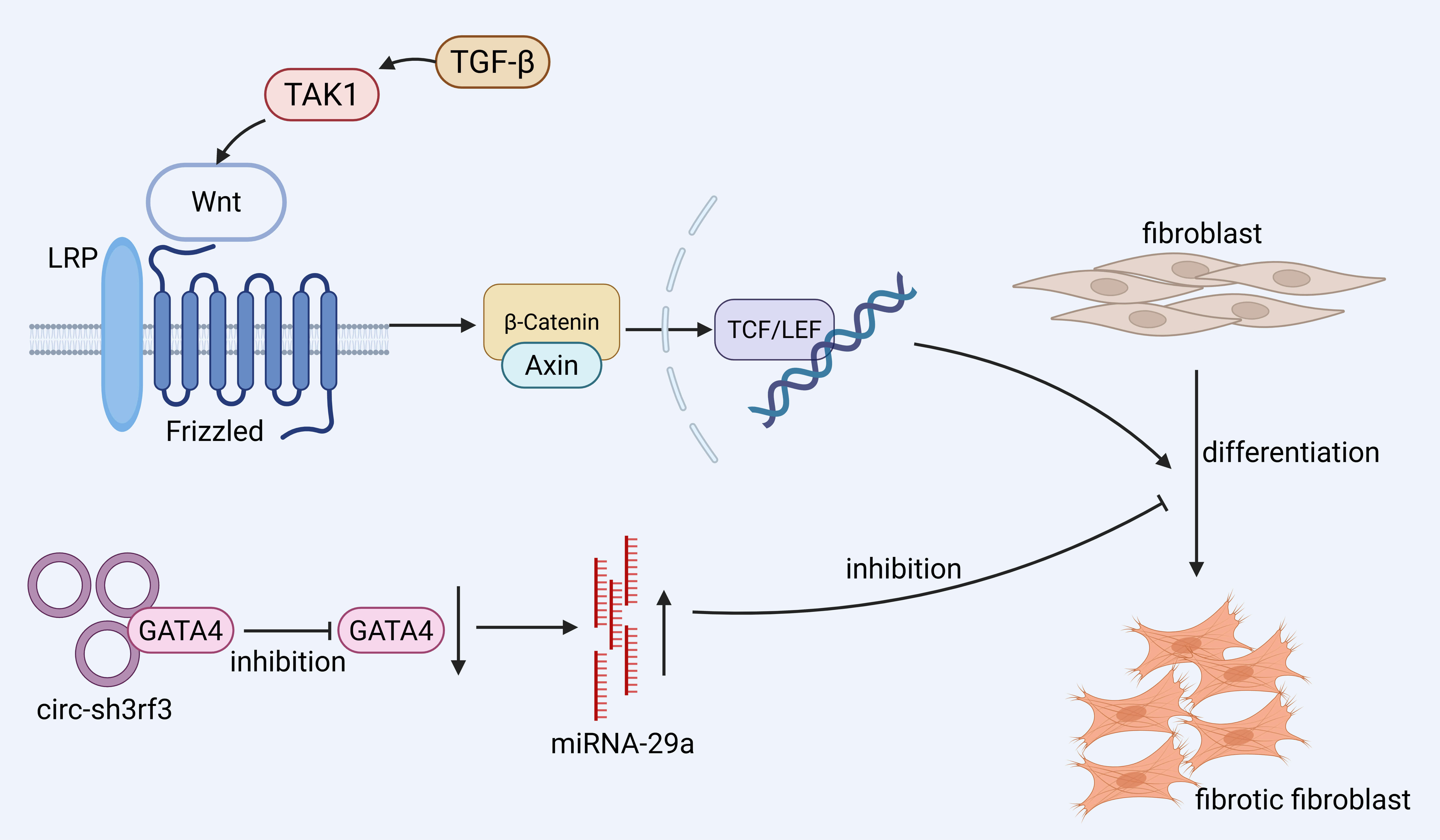

The differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts is a central step in the

progression of fibrosis. In the heart, the Circular RNA SH3 Domain Containing

Ring Finger 3 (Circ-sh3rf3)/GATA Binding Protein 4 (GATA-4)/microRNA-29a

(miR-29a) axis has been identified as a regulatory pathway that modulates this

process [59]. Mechanistically, Circ-sh3rf3 interacts with and downregulates

GATA-4, a transcription factor that normally represses miR-29a. The resulting

upregulation of miR-29a suppresses myofibroblast differentiation, thereby

attenuating cardiac fibrosis. Although this pathway is currently characterized in

cardiac tissue, further studies are needed to determine its relevance in other

organs. Wnt binds Frizzled proteins, activating

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Promotion of fibroblast differentiation to pro-fibrotic

fibroblasts mainly involves the Wingless/Integrated (Wnt)/

Furthermore, the process of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion is influenced

by multiple factors. Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 1 (SFRP1) is a key

inhibitor of lung fibroblast invasion during the transition to myofibroblasts

after lung injury. SFRP1+ transitional fibroblasts appear prior to the

formation of invasive myofibroblasts, and TGF-

Both macrophages and fibroblasts act as important regulatory effector cells in tissue fibrosis, interacting through a macrophage–fibroblast axis that significantly influences fibrotic progression. Macrophage-conditioned medium has been shown to directly stimulate fibroblast proliferation and ECM protein production in vitro [67]. This interaction is mediated by multiple pathways and is influenced by the immunometabolic environment. Under conditions of inflammation, hypoxia, and immune modulation, macrophages undergo phenotypic changes that, in turn, activate fibroblasts and promote their differentiation into myofibroblasts. This dynamic interaction leads to excessive ECM deposition, further driving fibrosis [68].

Monocyte-derived AMs are a key cell type in pulmonary fibrosis; they are located

predominantly in fibrotic areas and stimulate fibroblast proliferation by

secreting pro-fibrotic factors [4]. Macrophages produce pro-fibrotic factors that

directly activate fibroblasts, including the transforming growth factor

TGF-

Macrophage–fibroblast interactions are stable in healthy tissues. However,

after myocardial infarction, cardiac fibroblasts and macrophages function

together to regulate tissue homeostasis and infarct repair. Cardiac fibroblasts

and macrophages collaborate closely to regulate the fibrotic response.

FAP+POSTN+ fibroblast subpopulations play a pivotal role in fibrosis

progression, with their development and maturation promoted by IL-1

In lung fibrosis, fibroblasts and macrophages are crucial for repair after

tissue injury. Highly proliferating SPP1hi macrophages in fibrotic tissues play a

crucial role in activating myofibroblasts, a process supported by co-localization

studies and causality models [8]. Akt1 induces macrophage mitochondrial ROS and

mitophagy, contributing to AM anti-apoptosis, which ultimately promotes

TGF-

In liver and kidney fibrosis, the macrophage surface receptor tyrosine kinase

MERTK activates the ERK-TGF-

In the skin, a fibrotic signaling loop is formed between ECM-producing

fibroblasts and pro-fibrotic SPP1+ myeloid cells, mediated through the SPP1

signaling pathway. Corticosteroids have been shown to disrupt this circuit by

reversing the transcriptional programs of SPP1+ macrophages and POSTN+

fibroblasts [81]. Additionally, Wnt signaling enhances the expression of

fibrosis-associated genes by activating

While most of the literature on macrophage–fibroblast interactions has focused on the effect of macrophages on fibroblasts, fibroblasts themselves also have a significant impact on macrophages during the course of fibrosis. One key interaction is the stimulation of bone marrow cell transformation. In this process, the proliferation of fibroblast-derived or autocrine growth factors, in addition to granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), is required [81]. Fibroblasts also regulate macrophage activation through signaling pathways. For example, fibroblast Smad7 expression is upregulated in the heart after pressure overload, and Smad7 protects cardiac function by reducing collagen deposition, inhibiting MMP2-mediated matrix degeneration and suppressing macrophage activation by inhibiting stromal cell proteins [83]. In addition, prostacyclin I2 (PGI2) inhibits fibroblast activation through activation of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway via the prostaglandin I2 receptor (PTGIR). PGI2 is a key antifibrotic factor in the repair of renal injury, and attenuates renal fibrosis by inhibiting the over-activation of fibroblasts, whereas inhibition of stromal cell proteins inhibits macrophage activation and attenuates the progression of fibrosis [84]. Pro-fibrotic macrophages also produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, which regulate inflammatory cell recruitment and ECM turnover [85]. CXCL14 promotes the activation and recruitment of bone marrow-derived macrophages [86]. FAP is expressed in a subpopulation of activated fibroblasts and promotes the pro-fibrotic activity of macrophages during liver fibrosis [58].

The healing of organ tissues post-injury likely progresses through three stages: inflammation, tissue regeneration, and remodeling [87]. In the early inflammatory phase, macrophages rapidly accumulate at the injury site, promoting immune responses and clearing debris. If macrophages are depleted during this acute window—such as in models of myocardial infarction—this can lead to long-lasting adverse effects, including impaired tissue regeneration, persistent fibrosis, and functional decline [88]. Similarly, in a rat model of cerebral ischemia, macrophage infiltration in the acute phase was positively correlated with fibronectin expression, suggesting early involvement in fibrotic remodeling [67].

Fibroblasts respond to injury by differentiating into inflammatory fibroblasts

during the early phase, which then give rise to pro-fibrotic fibroblasts during

regeneration [89]. Macrophages regulate this transition: in macrophage-depleted

models, premature activation of fibroblasts occurs, highlighting their role in

restraining fibroblast activation during early repair [88]. This regulation is

mediated by TGF-

Recent studies suggest that macrophage-fibroblast interactions are temporally dynamic. For example, CD38+ macrophages—enriched during chronic fibrosis—originate from resident macrophages under CSF1/CSF1R signaling and promote fibrosis by depleting NAD+ in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs), thereby inducing senescence and sustaining inflammation. CD38+ macrophages secrete SASP-related cytokines such as CCL2 and IL6, while their depletion—genetically or pharmacologically (e.g., 78c)—restores NAD+, reduces RTEC senescence, and attenuates fibrosis in AKI models. These findings highlight not only their pro-fibrotic role but also the importance of intervention timing, as delayed targeting yields limited benefit [91]. Importantly, the functional role of macrophages is shaped not only by timing but also by organ-specific microenvironments, the nature of the injury, and co-existing immune or stromal signals. The same macrophage subtype may exhibit pro-fibrotic, anti-inflammatory, or remodeling functions depending on these cues. Similarly, fibroblasts contribute to macrophage recruitment and polarization through CCL2 and CXCL14 during the repair phase, establishing a feedback loop that evolves with tissue context [86, 92].

While stage-specific depletion of macrophages in preclinical models has provided proof-of-concept for temporally guided antifibrotic interventions, translating this strategy into clinical practice remains challenging. Human fibrotic diseases often progress insidiously, with blurred transitions between inflammation, repair, and fibrosis, making the identification of precise intervention windows difficult.

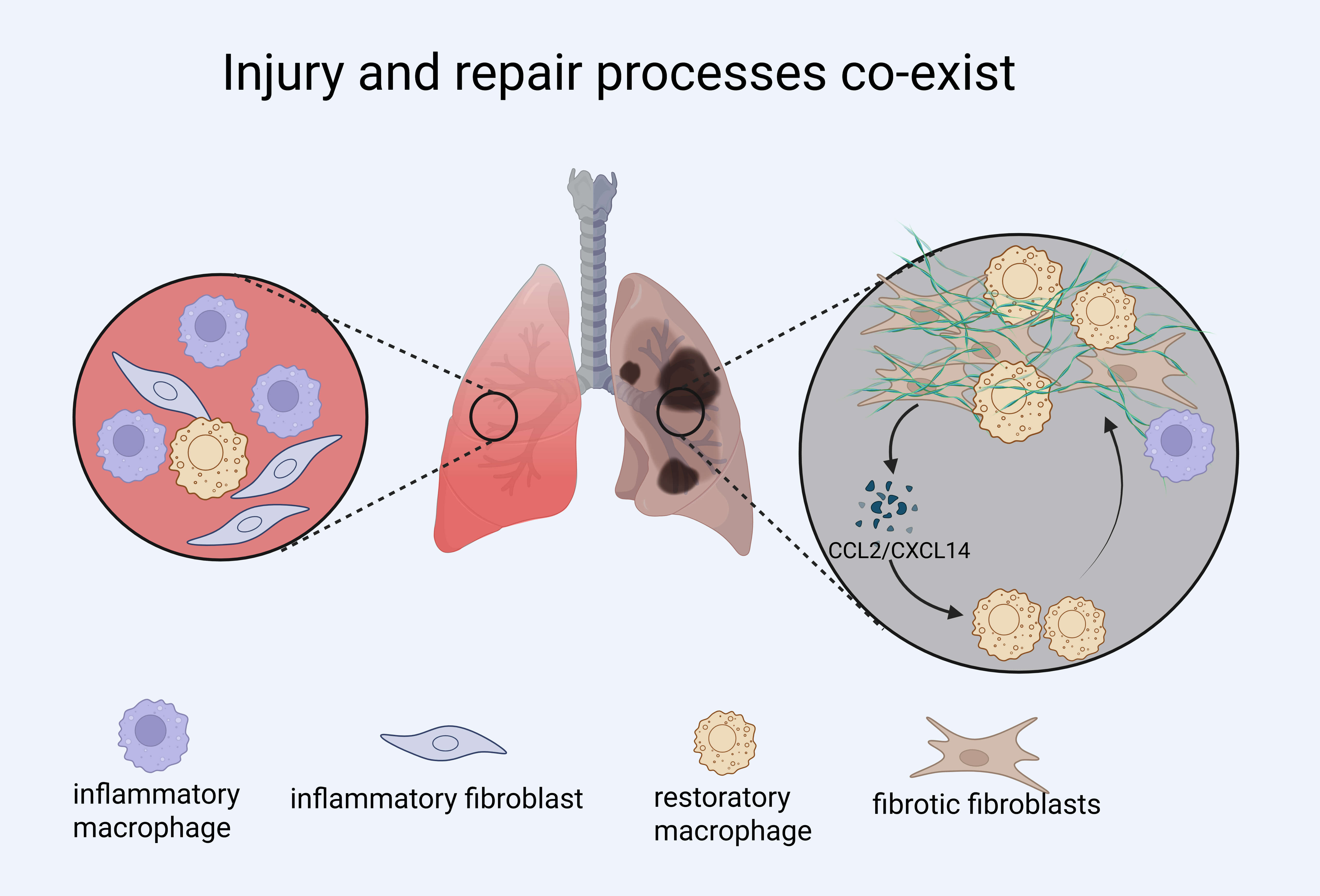

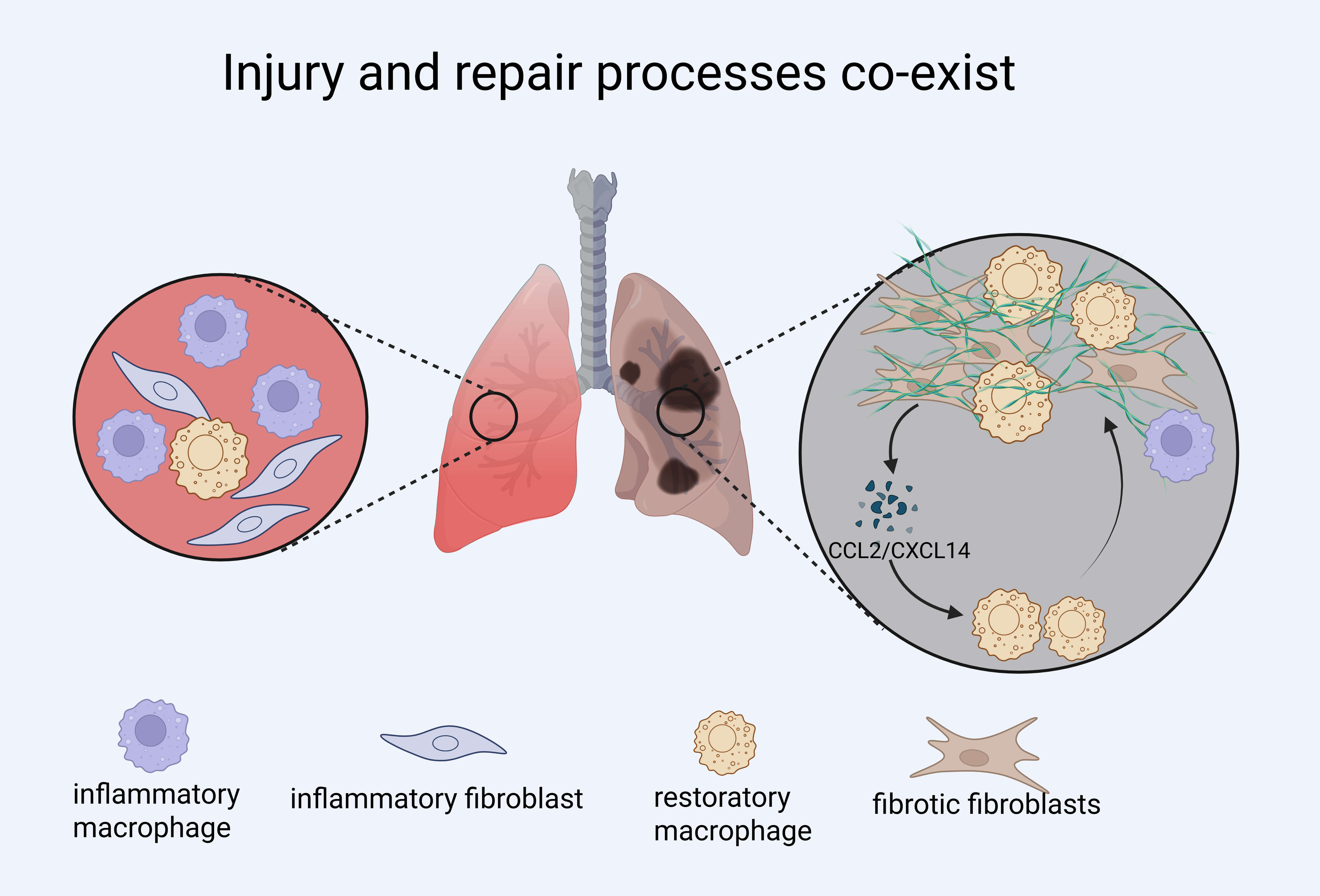

Together, these findings underscore that macrophage–fibroblast crosstalk is not static but evolves across time and tissue context. Effective interventions must therefore consider not only cell identity but also timing and functional state to avoid disrupting beneficial repair processes while targeting pathogenic fibrosis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Injury, inflammation, and fibrosis processes co-exist in fibrotic lung disease. Schematic illustration showing the coexistence and interplay of inflammatory and reparative processes during lung injury and fibrosis. Inflammatory macrophages and fibroblasts dominate early responses but may persist alongside restorative macrophages and fibrotic fibroblasts in chronic lesions. The diagram highlights the dynamic interactions between immune cells and stromal cells, including C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (CCL2)/C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 14 (CXCL14)-mediated crosstalk that reinforces fibroblast activation. Created with BioRender.com.

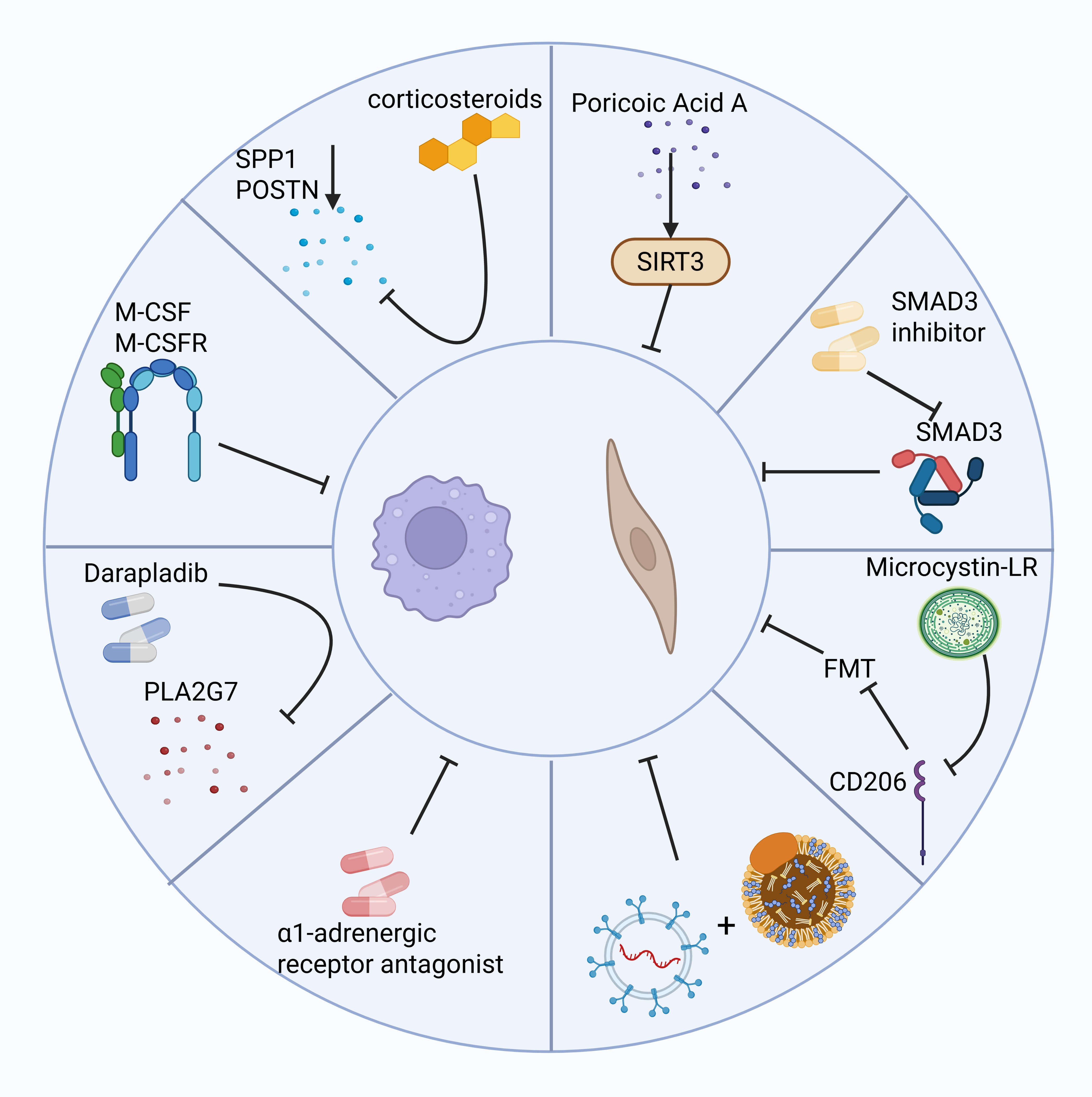

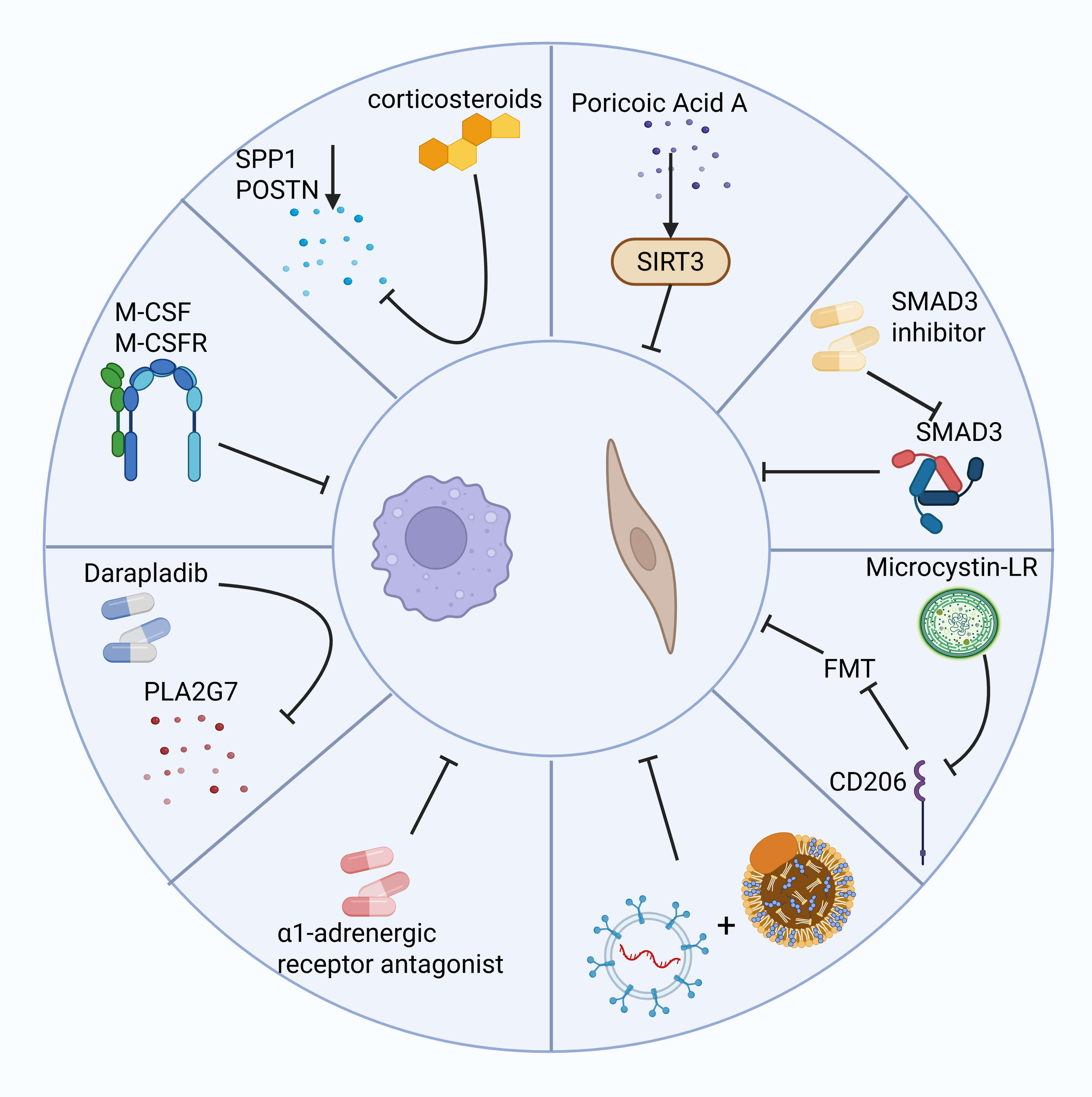

The role of macrophages in the fibrotic microenvironment has received widespread

attention, with modulation of their survival, differentiation, and function

showing significant therapeutic potential. Since macrophages in fibrosis are

primarily monocyte-derived, blocking SCUBE2+ to reduce monocyte-to-macrophage

differentiation significantly reduces macrophage numbers and attenuates fibrosis.

Inhibiting the M-CSF/M-CSFR pathway not only affects macrophage survival but also

slows fibrosis progression by modifying the fibrotic microenvironment [4].

Darapladib, a Phospholipase A2 Group VII (PLA2G7) inhibitor, significantly

reduces the number of PLA2G7-overexpressing macrophages, inhibits myofibroblast

accumulation, and attenuates pulmonary fibrosis [61]. Local injection of

corticosteroids greatly reduces the expression of SPP1 and POSTN genes, suggesting their potential as therapeutic targets for skin scar tissue

[93]. Furthermore, restoring RNF41 expression in macrophages of fibrotic mice

through a nanoparticle system improves liver function and reduces fibroblast

activation, highlighting RNF41’s potential as an antifibrotic target [29].

Additionally,

However, regulating macrophage function alone may not be sufficient to

completely reverse fibrosis. Fibroblasts are the main effector cells in fibrosis,

and their proliferation, differentiation, and activation processes are equally

important for fibrosis intervention. Poricoic acid A reduces renal fibroblast

activation and interstitial fibrosis by upregulating Sirt3, a process that

accelerates

Therapeutically, FAP-directed strategies such as CAR-T cells and peptide vaccines have demonstrated antifibrotic activity in preclinical models, though the magnitude of functional benefit is often modest and variable. Moreover, multiple translational barriers limit their immediate clinical applicability [99, 100]. These include on-target/off-tumor toxicity due to FAP expression in non-fibrotic tissues (e.g., peritumoral zones, inflamed or ischemic tissues), substantial inter-individual heterogeneity in FAP levels, and the context-dependent roles of FAP across different organ systems [101]. As such, there is a tangible risk of impairing physiological tissue remodeling or immune regulation. No FAP-targeted antifibrotic therapy has yet advanced to clinical approval.

Furthermore, the limited predictive value of many rodent models for human fibrosis, especially regarding chronic remodeling and immune heterogeneity, complicates the translation of preclinical findings. Future studies should prioritize biomarker-guided trial designs and mechanistic dissection of treatment windows. Given the dynamic, non-linear nature of fibrosis—with alternating active and quiescent phases—intervening at early pro-fibrotic transitions (e.g., monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, fibroblast priming) may offer higher reversibility, whereas established fibrosis may require matrix-directed or epigenetic reprogramming approaches. Combining molecular imaging with selective delivery methods, such as nanoparticle or antibody-drug conjugates, may improve therapeutic precision and minimize systemic toxicity (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The left side shows examples of several methods for inhibiting macrophages to reduce fibrosis, while the right side shows potential therapeutic methods for inhibiting fibroblasts to reduce fibrosis. Created with BioRender.com.

Over the past decade, advances in single-cell technologies have expanded our view of the cellular ecosystem driving fibrosis. We now recognize that neither macrophages nor fibroblasts act as uniform cell types; instead, they comprise diverse subpopulations with distinct—and often reversible—functional states. However, identifying these subsets is only a first step. We still lack a clear understanding of how macrophage–fibroblast interactions vary across disease stages and tissue contexts, or how these signals shift from promoting repair to driving pathological remodeling.

While populations such as SPP1+ macrophages and SCUBE2+ fibroblasts have been described as key players, their exact functions—especially in human disease—remain to be validated. Most evidence still comes from acute injury models in mice, and the extent to which these findings apply to human fibrosis, which evolves more slowly and heterogeneously, is uncertain.

The field must now move beyond cell-type cataloging and focus on mechanistic questions: What signals determine whether macrophages restrain or promote fibroblast activation? When, and in which tissue niches, do fibroblasts retain the capacity to revert to non-pathogenic states? And critically, can we define intervention windows where antifibrotic therapy improves outcome without disrupting necessary repair?

Answering these questions will require functional validation in vivo, integration of spatial and temporal information, and comparative studies across organs and species. Without this, we risk mistaking descriptive complexity for understanding—and will continue to fall short of translating biological insights into effective treatments.

AM, alveolar macrophages; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ECM, extracellular matrix; FAP, fibroblast activation protein; FMT, fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition; HCK, hematopoietic cell kinase; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; SHH, sonic hedgehog.

RS and ZH determined the study topic and direction, performed the comprehensive literature search, analyzed and summarized the relevant studies, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript; they also designed the overall structure and prepared the main figures and tables. LS assisted in data interpretation, contributed to figure design, and participated in revising the manuscript. YL participated in designing the research study, contributed to the interpretation of data, and polished the language of the manuscript. LX organized and formatted the references, and contributed to content revision during the later stages of manuscript preparation. CZ supervised the entire study, contributed to the study design, provided critical intellectual input, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used Deepseek in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.