1 Department of Neurology, Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University, 201508 Shanghai, China

Abstract

Neuronal cholesterol deficiency may contribute to the synaptopathy observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Intact synaptic vesicle (SV) mobility is crucial for normal synaptic function, whereas disrupted SV mobility can trigger the synaptopathy associated with AD. In this study, we investigated whether cellular cholesterol deficiency affects SV mobility, with the aim of identifying the mechanism that links cellular cholesterol loss to synaptopathy in AD.

Lentiviruses carrying 3β-hydroxysteroid-Δ24 reductase-complementary DNA (DHCR24-cDNA), DHCR24-short hairpin RNA (DHCR24- shRNA) or empty lentiviral vectors were transfected into SHSY-5Y cells in order to construct DHCR24 knock-down and knock-in models, along with corresponding controls. Filipin III cholesterol staining was employed to visualize membrane and intracellular cholesterol in the different cell models, and fluorescence intensity was assessed using confocal microscopy. Additionally, we performed immunoblotting to quantify the expression of DHCR24, total calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 (CAMK-2), p-CAMK2 (T286), caveolin-1, total synapsin-1, phosphorylated synapsin-1 (p-synapsin-1; S605), and synaptophysin in each experimental group.

In DHCR24-silenced cells, the loss of cellular cholesterol caused by knock-down of DCHR24 resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of phosphorylated CAMK2 (p-CAMK2) and phosphorylated synapsin-1 (p-synapsin-1) compared to control cells. The reduction in p-CAMK2 and p-synapsin-1 could disrupt SV mobility, thereby reducing replenishment of the readily releasable pool (RRP) from the reserve pool (RP). Furthermore, cells with DHCR24 knock-down showed downregulation of caveolin-1, a crucial lipid raft marker, compared to control cells. Conversely, elevated cellular cholesterol levels caused by knock-in of DHCR24 reversed the effects of cholesterol deficiency, suggesting that CAMK2-mediated synapsin-1 phosphorylation may be regulated in a lipid raft-associated manner. Additionally, we found that cellular cholesterol loss could significantly downregulate the expression of synaptophysin protein, which is vital for SV biogenesis and synaptic plasticity.

These results suggest that depletion of cellular cholesterol following knock-down of DHCR24 can decrease synaptophysin protein expression and impair SV mobility by regulating the CAMK2-meditated synapsin-1 phosphorylation pathway, potentially via a lipid raft-associated mechanism. Our study indicates a critical role for cellular cholesterol deficiency in AD-related synaptopathy, thus highlighting the potential for targeting cellular cholesterol metabolism in therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- DHCR24

- cholesterol

- CAMK2

- synapsin-1

- synaptic vesicle

- synaptopathy

Synaptic dysfunction is a characteristic feature of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This condition is closely linked to cognition and memory [1]. Mounting evidence suggests that defective memory and cognition in AD are not only a direct consequence of synaptic dysfunction, but also an indirect result of other major pathological changes, such as amyloid beta accumulation, phosphorylated tau, neuroinflammation, and programmed cell death. These can also initiate or compromise memory and cognition by inducing synaptic disorder [2, 3, 4].

Cholesterol is critical in the proper structural and functional development of the brain through its influence on neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitter release, and signal transduction [5]. Since the 1990s, numerous epidemiological, genetic and biological studies have implicated altered cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis of AD [6, 7, 8, 9]. Mutations or polymorphisms in genes can reduce cholesterol transport to the brain, thus impairing neuronal cholesterol uptake and trafficking. Such genes include apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), ATP binding cassette transporter, the low-density lipoprotein receptor family, and Niemann-Pick C disease 1 or 2, resulting in cellular cholesterol deficiency in the brain tissue of patients and animal models with inherited AD [9, 10, 11]. Various studies involving inherited AD animal models, particularly those with the ApoE4 genotype, strongly suggest that loss of cellular cholesterol in the brain contributes to diverse AD-related pathological processes [9, 10, 11].

Methyl-

The precise role of cholesterol metabolism in AD-associated synaptopathy is still unclear. Synaptic cholesterol deficiency could diminish neurotransmitter release by reducing calcium (Ca2+) influx and Ca2+ channel activity [18, 19]. Notably, the Ca2+ channel is localized in the lipid raft [20], and Ca2+ influx can directly activate calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 (CAMK2). This serine/threonine protein kinase is crucial for synaptic vesicle (SV) mobility [21]. Cholesterol is an important component of membrane lipid rafts, which are essential for cell membrane signal transduction. Deficiency in cellular cholesterol disrupts lipid raft formation and is strongly implicated in AD pathology [22, 23]. An excellent model used to investigate the biochemical mechanisms underlying SV mobility is the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. This expresses major SV markers and contains various types of vesicles, as well as the capability for calcium-dependent synaptic exocytosis [24, 25, 26, 27]. In the present study, SH-SY5Y cells were used to construct cell models with varying cholesterol levels by modulating the DHCR24 gene. We hypothesized that decreased cellular cholesterol may impair SV mobility in a lipid raft-associated manner, potentially contributing to AD synaptopathy.

Rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:3000, 2118, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-DHCR24/Seladin-1 (1:1000, 2033, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Phospho-Synapsin-1 (Ser605) (1:1000, 88246S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Synapsin-1 (1:1000, 5297S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-CaMKII (pan) (1:1000, 4436S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Phospho-CaMKII (Thr286) (1:1000, 12716T, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Caveolin-1 (1:1000, 3267T, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Synaptophysin (1:1000, 36406S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibody (1:5000, 7074P2, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody (1:5000, 7076P2, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), Filipin III (0.1 mg/mL, abs42018484, Absin, Shanghai, China), propidium iodide (PI) (3.5 µg/mL, abs9105, Absin, Shanghai, China).

SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and grown in DMEM (Gibco, New York, NY, USA) containing 10% FBS (Biological Industries, Be’er Sheva, Israel) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and in 10 cm culture dishes (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China). The cells were then seeded into 6-well plates and grown to approximately 30–40% confluence. Lentivirus packed with DHCR24 cDNA, DHCR24 shRNA, or empty vector (Jima, Shanghai, China) were transfected into SH-SY5Y cells (Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) = 4). After 24 h, the medium was removed and fresh virus-free medium was added. Afterward, cells were treated with puromycin (8 µg/mL) for 48 h to kill uninfected cells and screen out successfully transfected cells. Infected cells that expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) were observed under the fluorescent microscope. Cells were constantly cultured in puromycin-containing medium at the appropriate concentration for several passages. Short tandem repeat (STR) profiling was used to validate all cell lines, which also tested negative for mycoplasma. We confirmed that SH-SY5Y cells were well transfected with lentivirus and ready for subsequent experiments.

SDS lysis buffer (KeyGen Biotech, Nanjing, China) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (KeyGen Biotech, China) was used to lyse cells. Protein samples were then boiled at 100 °C with sample buffer and fractioned by SDS-PAGE. Subsequently, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes, blocked with 5% skimmed milk, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the corresponding primary antibody. Secondary antibody contained the Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) label was then used to detect protein expression by chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Cells were cultured in 24-plate cover glass dishes to reach confluence of 60–70% and then washed thrice with PBS after removal of the medium. The cells were subsequently incubated with Filipin III solution for 30 minutes at room temperature and then stained with PI for 10 minutes. Filipin III, PI and GFP were detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Immunoblotting results and fluorescence intensity were analyzed by ImageJ2 software (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA). The p-value for comparison of two groups was calculated using the t-test and GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical data were presented as the mean

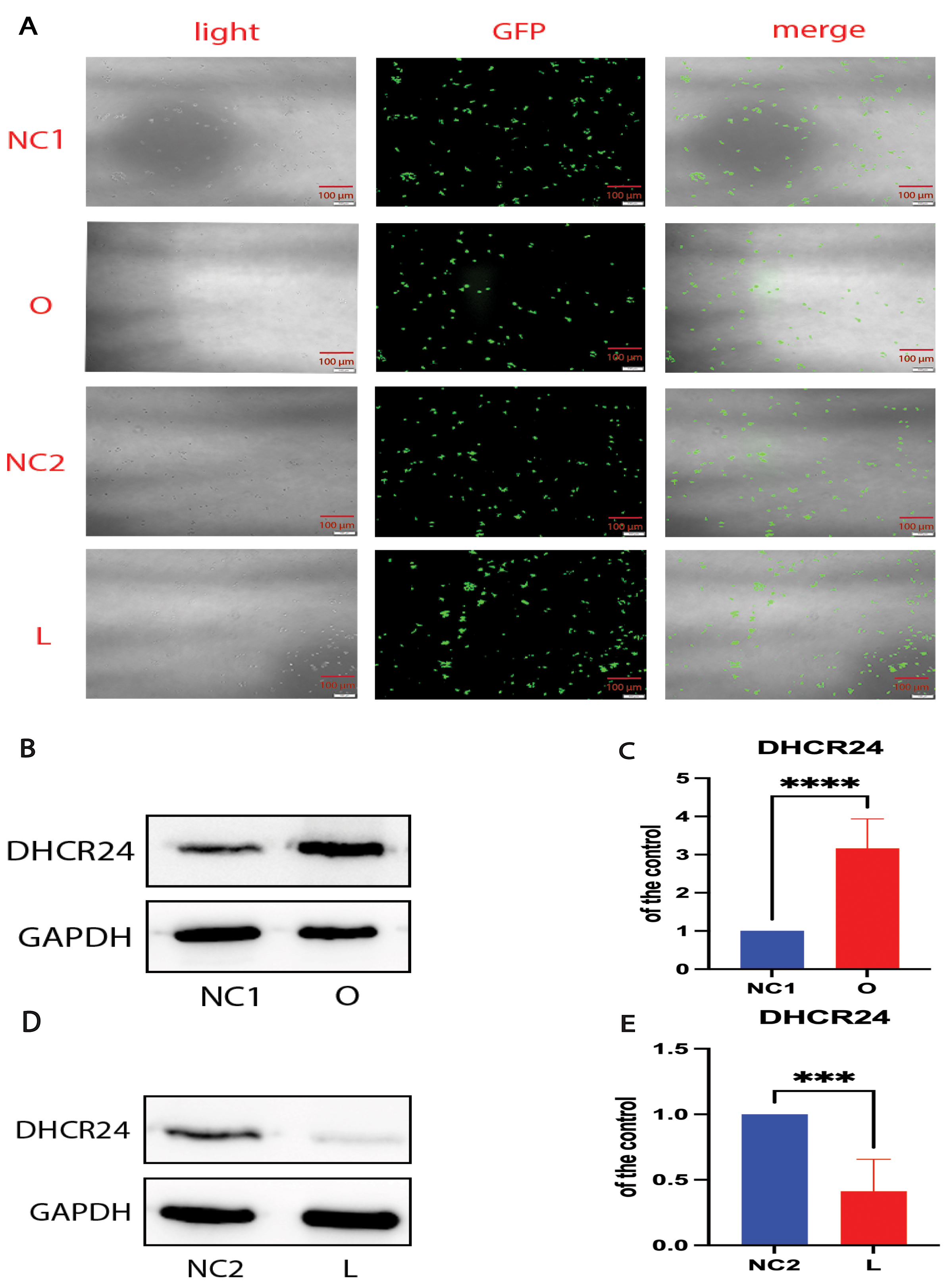

Our previous experiments demonstrated that cholesterol levels in neuronal cell lines could be modulated by DHCR24 knock-in or knock-down [28, 29]. In the present experiments, we performed DHCR24 knock-down to create a neuronal cell model of cellular cholesterol deficiency, and DHCR24 knock-in to create a neuronal cell model of elevated cellular cholesterol. Fluorescence microscopy demonstrated that lentivirus-meditated DHCR24-shRNA and DHCR24-cDNA were successfully transfected into the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line, as visualized by green staining with microscopy (Fig. 1A). Compared with the control group, DHCR24 protein expression was significantly decreased in DHCR24 silenced cells (Fig. 1B,C). In contrast, the expression of DHCR24 protein was markedly increased in cells overexpressing DHCR24 compared to the controls (Fig. 1D,E). Thus, we confirmed that our cell models were successfully transfected by DHCR24 knock-down or knock-in.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Cell models were successfully transfected by DHCR24 knockdown and knockin. The human SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with the lentivirus-delivered DHCR24-shRNA, DHCR24-cDNA, and lentiviral vectors to produce the low-expressing DHCR24 cell group (L), over-expressing DHCR24 cell group (O), vector control cell groups (negative control group, NC), respectively. (A) DHCR24-shRNA, DHCR24-cDNA, and the lentiviral vector were strongly expressed in SH-SY5Y cells, as indicated by GFP (green) under fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B,D) Western blot analysis of extracts from the low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L), over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O), and vector control cells (NC), was performed. The representative western blots of DHCR24 protein are shown in (B,D). (C,E) Quantifications of three experiments are shown in (C,E). Results shown are the mean

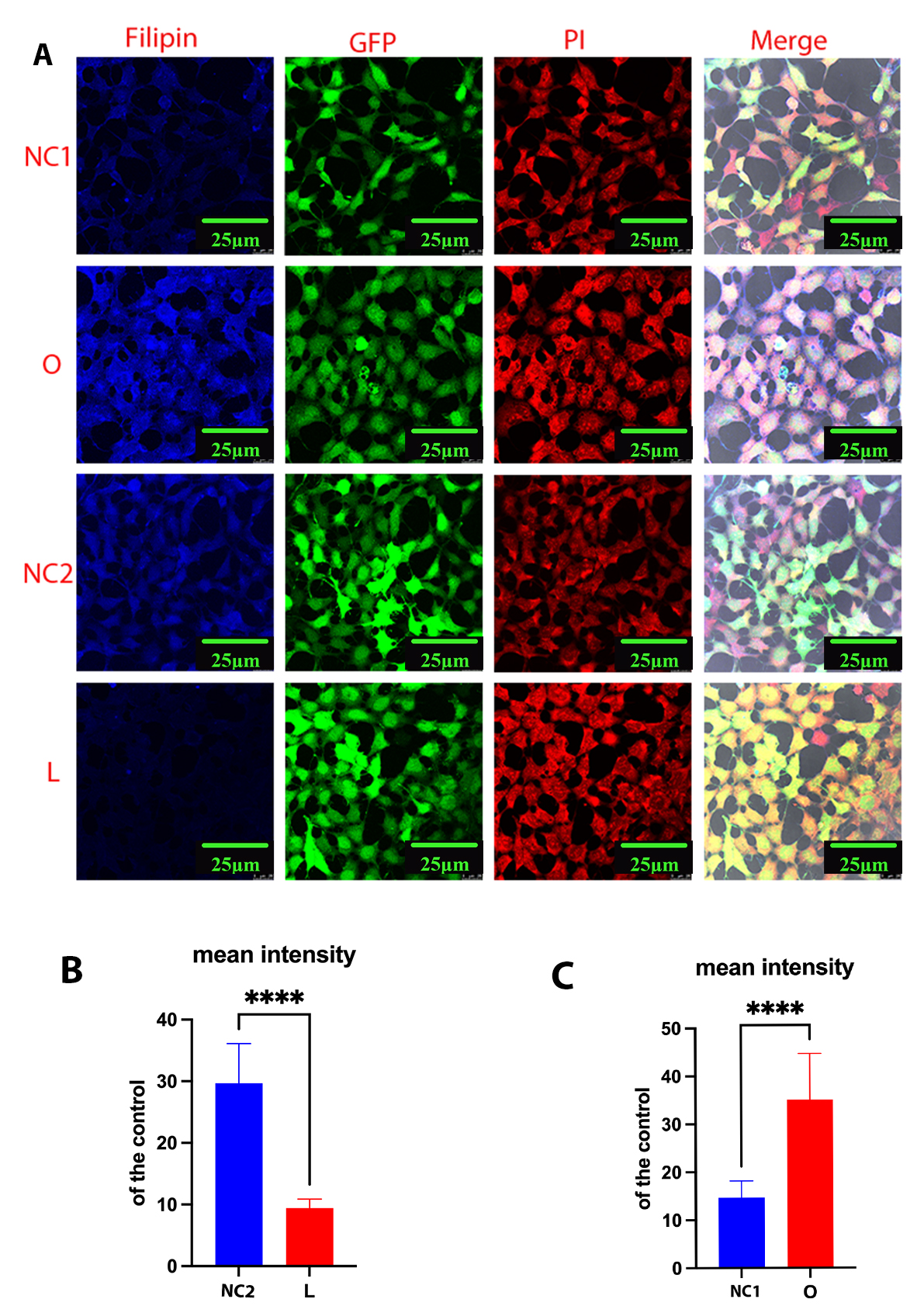

Next, we performed Filipin III staining to evaluate the cholesterol level in transfected cell lines. After staining, the plasma membrane and intracellular cholesterol levels were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. In DHCR24-silenced cells, the fluorescence intensity was weaker than in control cells, indicating lower plasma membrane and intracellular cholesterol levels (Fig. 2A,B). In contrast, Filipin III staining showed markedly increased levels of plasma membrane and intracellular cholesterol in cells overexpressing DHCR24 compared to the controls (Fig. 2A,C). These findings were consistent with observations from previous studies [17, 23, 28]. Based on our earlier work and the present results, the above data demonstrate that DHCR24 knock-down or knock-in can be used to construct neuronal cell models of cholesterol deficiency, or elevated cholesterol, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Cellular cholesterol level as analyzed by Filipin III staining. Cells from the low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L), over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O), and vector control cells (NC) were stained with Filipin III. (A) Whole-cell staining of fixed SH-SY5Y cells. Filipin III stains cholesterol in the plasma membrane and in intracellular compartments. Blue staining is Filipin III, red staining is PI (propidium iodide), and green staining is GFP fluorescence. The final panel shows the merged image from the three channels. Scale bar = 25 µm. (B,C) Filipin fluorescence intensity of cholesterol in whole cells was measured using ImageJ2 Software in differential cell groups. Results shown are the mean

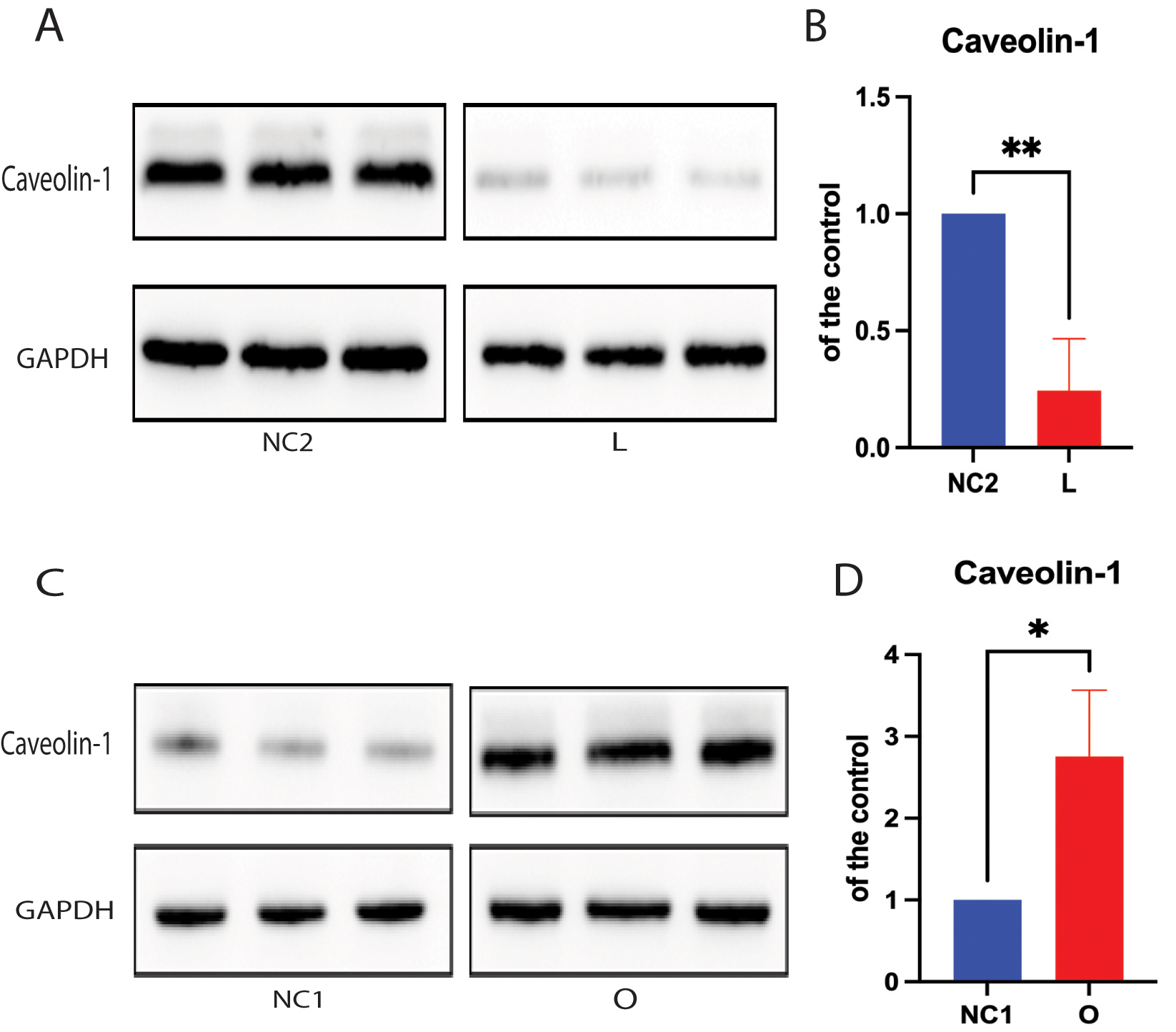

Cholesterol is a key lipid molecule within cell membranes, and the cellular cholesterol level positively affects expression of the cholesterol-binding protein caveolin-1 (Cav-1) [17, 18, 28]. Both cholesterol and Cav-1 are critical structural components of the caveolae/lipid-rafts involved in many cell signaling pathways [17, 28, 29, 30]. Thus, we further analyzed the effect of cellular cholesterol depletion on the expression of Cav-1 protein. Cav-1 expression was found to be markedly lower in SH-SY5Y cells following DHCR24 knock-down compared to control cells, indicating disruption of membrane caveolae/lipid-rafts (Fig. 3A,B). Conversely, Western blot analysis revealed that DHCR24 overexpression significantly upregulated the expression of Cav-1 in the caveolae fraction of SH-SY5Y cells with DHCR24 knock-in, suggesting an increase in membrane caveolae (Fig. 3C,D). Consistent with earlier reports [17, 22, 29], we also found that knock-down of DHCR24 simultaneously decreased the levels of plasma membrane cholesterol and Cav-1 in caveolae/lipid-rafts. Therefore, cellular cholesterol depletion following knock-down of DHCR24 can impair the structure and function of caveolae/lipid-rafts in the plasma membrane by downregulating Cav-1 expression.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Cellular cholesterol loss leads to downregulation of the lipid-raft protein caveolin-1. For Protein extracts from low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L), over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O), and vector control cells (NC) were used for Western blot analysis of caveolin-1 expression. (A,B) The representative Western blot of caveolin-1 protein and quantification of three experiments are shown in (A,B) in the low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L) and vector control cells (NC2). (C,D) The representative Western blot of caveolin-1 protein and quantification of three experiments are shown in (C,D) in the over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O) and vector control cells (NC1). Results shown are the mean

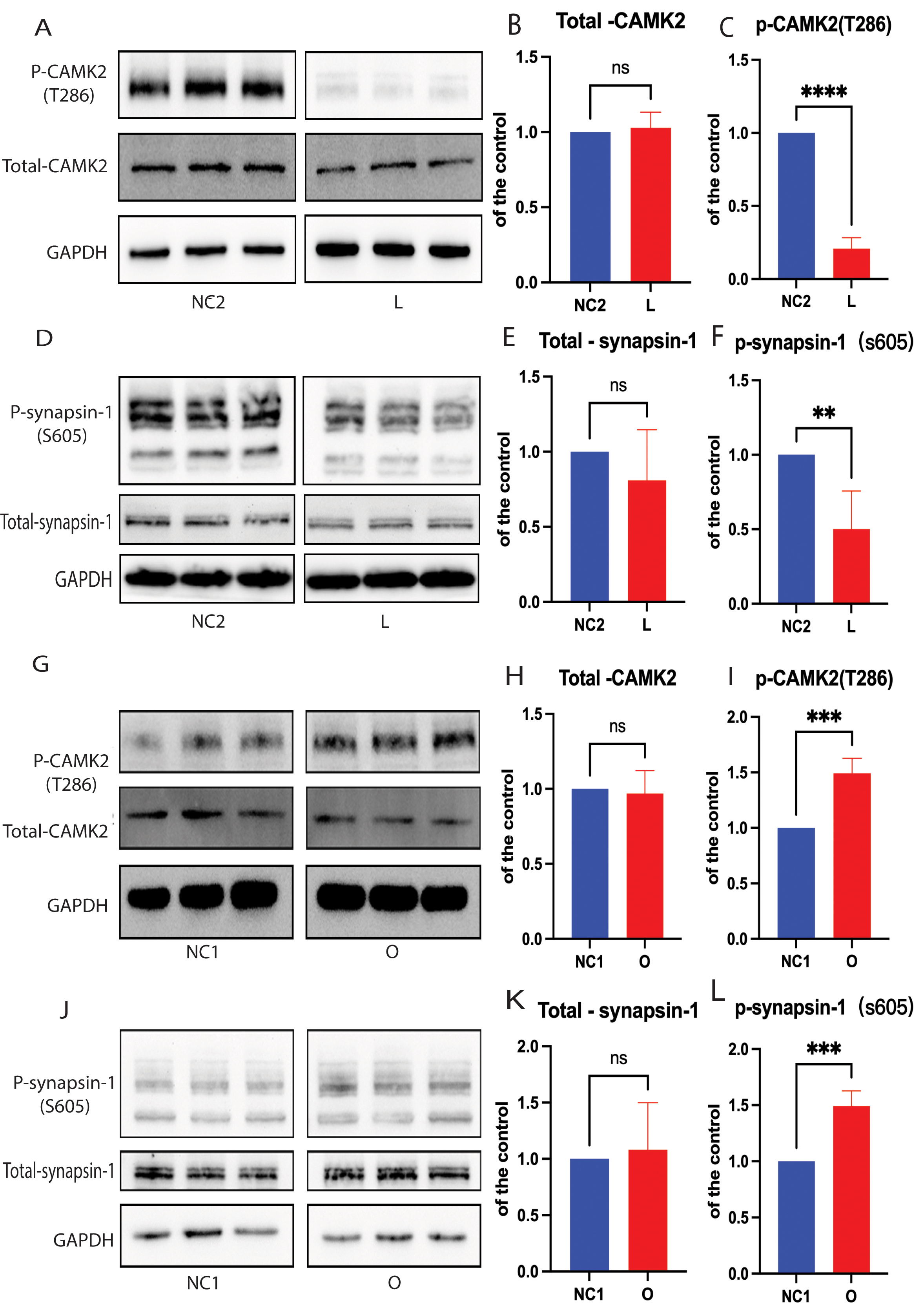

Caveolae are cholesterol-rich lipid-raft microdomains in the plasma membrane that regulate the function of protein kinases such as calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMK2), which contribute to SV recycling [31, 32]. Here, we further evaluated the phosphorylation state of CAMK2 at the T286 site in SH-SY5Y cells. The level of phosphorylated CAMK2 (p-CAMK2) was found to be significantly lower in cells with DHCR24 knock-down compared to control cells, leading to reduced activity of CAMK2 kinase (Fig. 4A,C). In contrast, elevated cellular cholesterol in cells with DHCR24 overexpression increased the level of phosphorylated CAMK2 protein compared to control cells, suggesting increased CAMK2 kinase activity (Fig. 4G,I). However, the total CAMK2 protein level was similar between the different groups and the control (Fig. 4A,B,G,H). In summary, the above findings demonstrate that depletion of cellular cholesterol by DHCR24 knock-down can impair the lipid-raft organization of caveolae, thus inhibiting activation of CAMK2 signaling in a lipid raft-associated manner.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Cellular cholesterol loss lowers the level of p-synapsin-1 protein by CAMK2 signaling. For Western blot analysis of total synapsin-1, phosphorylated synapsin-1 (p-synapsin-1), total CAMK2, and phosphorylated CAMK2 (p-CAMK2). Protein extracts were obtained from the low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L), over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O), and vector control cells (NC). (A–F) Representative Western blots of total synapsin-1 and p-synapsin-1, total CAMK2, and p-CAMK2 and quantification of three experiments are shown in (A–F) for the low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L) and vector control cells (NC2). (G–L) Representative Western blots of total synapsin-1, p-synapsin-1, total CAMK2, and p-CAMK2; quantification of three experiments are shown in (G–L) for over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O) and vector control cells (NC1). Results shown are the mean

Synapsin-1 is an SV-associated phosphoprotein that modulates the mobility of SVs [33, 34]. Synapsin-1 is an important downstream substrate of CAMK2 signaling and its phosphorylation is positively regulated by Ca2+/CAMK2 [34]. We therefore quantified total synapsin-1 and phospho-synapsin-1 (S605) by Western blot analysis. The level of total synapsin-1 was similar between the different groups (Fig. 4D,E,J,K), whereas phospho-synapsin-1 (S605) was significantly lower in cells with DHCR24 knock-down compared to the controls (Fig. 4D,F). Conversely, phospho-synapsin-1 (S605) was significantly increased in cells that over-expressed DHCR24 compared with the control group (Fig. 4J,L). Interestingly, CAMK2 can phosphorylate two sites in the carboxy-terminal region of synapsin-1, causing it to dissociate from SVs [33, 34], while dephosphorylated synapsin-1 can reverse this process. Based on results from earlier reports and from the present study, we postulate that cellular cholesterol deficiency caused by DHCR24 knock-down can markedly decrease synapsin-1 phosphorylation via the activation of CAMK2.

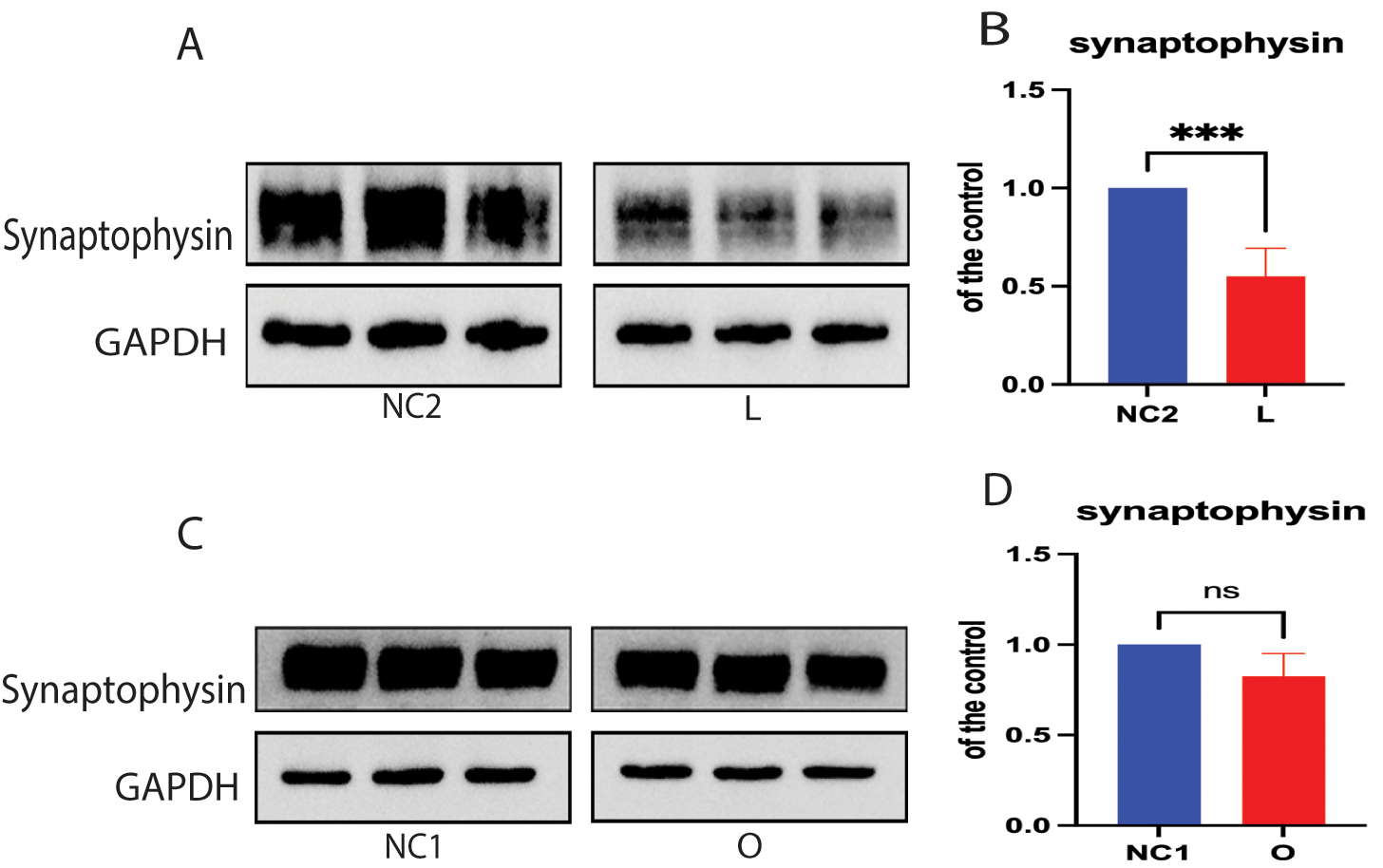

Previous reports suggest that synaptophysin is a major protein in SVs and that it contributes to synaptic plasticity and SV biogenesis [35, 36]. We therefore investigated whether the depletion of cellular cholesterol affects the expression of SV synaptophysin. We found that depletion of cellular cholesterol resulted in decreased expression of synaptophysin protein in DHCR24 knock-down cells compared to controls (Fig. 5A,B). However, no significant difference in synaptophysin protein expression was found between cells with DHCR24 overexpression and control cells (Fig. 5C,D). Hence, the above findings indicate that depletion of cellular cholesterol following DHCR24 knock-down downregulates the expression of SV synaptophysin.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Cellular cholesterol loss downregulated the expression of synaptophysin protein. Protein extracts from low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L), over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O), and vector control cells (NC) were used for Western blot analysis of synaptophysin protein. (A,B) The representative Western blot of synaptophysin protein and quantification of three experiments is shown in (A,B) in low-expressing DHCR24 cells (L) and vector control cells (NC2). (C,D) Representative Western blot analysis of synaptophysin protein and quantification of three experiments is shown in (C,D) for over-expressing DHCR24 cells (O) and vector control cells (NC1). Results shown are the mean

Although there is increasing evidence that cholesterol loss contributes to synaptic dysfunction in the brain of AD patients, the underlying molecular mechanisms are not yet fully understood [37, 38]. Interestingly, our research team and other scholars have demonstrated that cellular cholesterol deficiency caused by knock-down of DHCR24 results in the disruption of membrane lipid raft-dependent signals [17, 28, 29, 39]. The use of Filipin III staining in the current study again revealed that knock-down of DHCR24 induced a significant decrease in the cellular cholesterol level. Moreover, free cholesterol is an important component of lipid rafts and promotes their formation and polarization. Membrane signaling molecules are concentrated within lipid rafts, thereby regulating cell signaling activity. Additionally, a critical structural protein within caveolae/lipid rafts, Cav-1, is a key molecular organizer of various cellular functions, including endocytosis/exocytosis and signal transduction. Previous studies have shown that reduction of cellular cholesterol via knock-down of DHCR24 markedly decreases Cav-1 protein expression and disrupts lipid raft integrity [17, 22, 28, 29]. The results of our study confirm previous reports that cellular cholesterol deficiency can lead to disruption of membrane lipid rafts.

Our experiments showed that reduction in cellular cholesterol significantly decreased the phosphorylation of CAMK2 at the T286 site in SH-SY5Y cells with DHCR24 knock-down, suggesting inhibition of the CAMK2 signaling pathway. In contrast, the level of phosphorylated CAMK2 (p-CAMK2) was markedly increased in SH-SY5Y cells that overexpressed DHCR24, indicating activation of the CAMK2 signaling pathway. Notably, cholesterol-enriched lipid raft/caveolae are Ca2+-signaling microdomains that regulate Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ channel activity [31, 32]. A previous study had shown that decreased cellular cholesterol contributed to lower neurotransmitter release by decreasing Ca2+influx and Ca2+ channel activity at synapses [19]. Interestingly, CAMK2 is a crucial Ca2+-dependent kinase, and Ca2+ influx leads to CAMK2 activation by inducing autophosphorylation at the T286 site [40]. Therefore, by integrating our findings with previous data, we propose that loss of cellular cholesterol could inhibit CAMK2 phosphorylation activity, potentially mediated by caveolae/lipid raft-dependent calcium signaling.

Furthermore, accumulating evidence indicates a significant relationship between phosphorylation of CAMK2 at the T286 site and AD. Specifically, reduced phosphorylation of CAMK2 at this site was observed in AD patients, whereas increased phosphorylation was associated with enhanced memory formation [41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. Our results showed that loss of cellular cholesterol can reduce CAMK2 activation by inhibiting the phosphorylation of CAMK2 at the T286 site.

Furthermore, synapsin-1 is critical in the SV life cycle and serves as a direct substrate for calcium/CAMK2 [46, 47]. To clarify the downstream effects of decreased phosphorylation of CAMK2 at the T286 site, we also measured the level of synapsin-1 phosphorylation. Our findings showed that cellular cholesterol deficiency could significantly inhibit CAMK2 phosphorylation (T286) activity, and simultaneously reduce the synapsin-1 phosphorylation (S605) level (Fig. 4). Conversely, the increase in cellular cholesterol caused by knock-in of DHCR24 promoted CAMK2 phosphorylation (T286) and increased synapsin-1 phosphorylation (S605) (Fig. 4). Collectively, these findings suggest that decreased activity of synapsin-1 phosphorylation may be induced by inhibition of CAMK2 signaling. Therefore, our data revealed firstly that cellular cholesterol deficiency caused by the knock-down of DHCR24 can lead to decreased phosphorylation of synapsin-1, potentially via lipid-raft-dependent CAMK2 signaling.

Importantly, synapsins are pivotal regulators of SV dynamics within presynaptic terminals and are thought to participate in regulating the SV life cycle [48, 49]. In particular, synapsin-1 is phosphorylated by calcium/calmodulin, resulting in SV mobilization from the reserve pool (RP) during neurotransmission. Specifically, synapsin-1 induces trafficking of SVs from the RP to the readily reversible pool (RRP) after stimulation [50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]. Increased synapsin-1 phosphorylation (S605 site) by CAMK2 signaling could reduce SV clustering, diminish interaction with actin filaments, and enhance SV movement towards the active zone, thereby increasing RRP formation [50, 53, 56, 57, 58]. Conversely, reduced synapsin-1 phosphorylation at the S605 site strengthens the SV binding and synapsin-1-actin interaction, thereby increasing construction of the SV-synapsin-1-actin complex [33, 57, 58, 59]. In addition, the decrease in phosphorylated synapsin-1 (S605 site) could lead to reduced SV movement towards the active zone of synapses, resulting in decreased RRP formation [59, 60, 61]. Thus, our results strongly indicate that cellular cholesterol deficiency reduces replenishment of the RRP from the RP by decreasing synapsin-1 phosphorylation via CAMK2 signaling, potentially in a lipid raft-associated manner. Taken together, our data suggest a novel mechanism for the effect of cellular cholesterol deficiency on SV mobility.

Of note, our study also found that decreased cellular cholesterol caused by knock-down of DHCR24 significantly reduced synaptophysin protein expression, with no significant increase observed in cells overexpressing DHCR24 (Fig. 5A–D). Although the specific function of synaptophysin is not yet fully understood, accumulating evidence highlights the important role played by synaptophysin during SV biogenesis, exocytosis, and synaptic plasticity [35, 36, 62, 63]. We hypothesize that disruption in the formation of lipid raft microdomains caused by loss of cellular cholesterol leads to altered lipid raft-dependent signal transduction, which then downregulates synaptophysin expression. Furthermore, previous studies have indicated that synaptophysin can bind to cholesterol, with this interaction being crucial for SV biogenesis [36, 62, 64]. Given the role of synaptophysin as a cholesterol-binding protein, cellular cholesterol deficiency may impair SV biogenesis by disrupting the cholesterol-synaptophysin interaction [65]. Consequently, our results indicate that decreased cellular cholesterol induced by knock-down of DHCR24 could also impair SV biogenesis and synaptic plasticity by downregulating synaptophysin expression and interfering with the cholesterol-synaptophysin interaction. Although this study investigated the impact of cholesterol deficiency on SV mobility and proposed a possible molecular mechanism, it was primarily focused on the expression level of important proteins in synaptic biosynthesis and SV mobility. More in-depth mechanistic studies are therefore required. The validity of the findings could be enhanced by future research employing live-cell imaging and neurophysiological techniques in primary cells, and animal models with DHCR24 knockdown-induced cholesterol deficiency. This approach would facilitate further observation and investigation of the relationship between cholesterol deficiency and SV transport in live cells, as well as the release of neurotransmitters. Additionally, it would allow for a more detailed exploration of the mechanisms underlying these molecular events and their roles in the onset of AD.

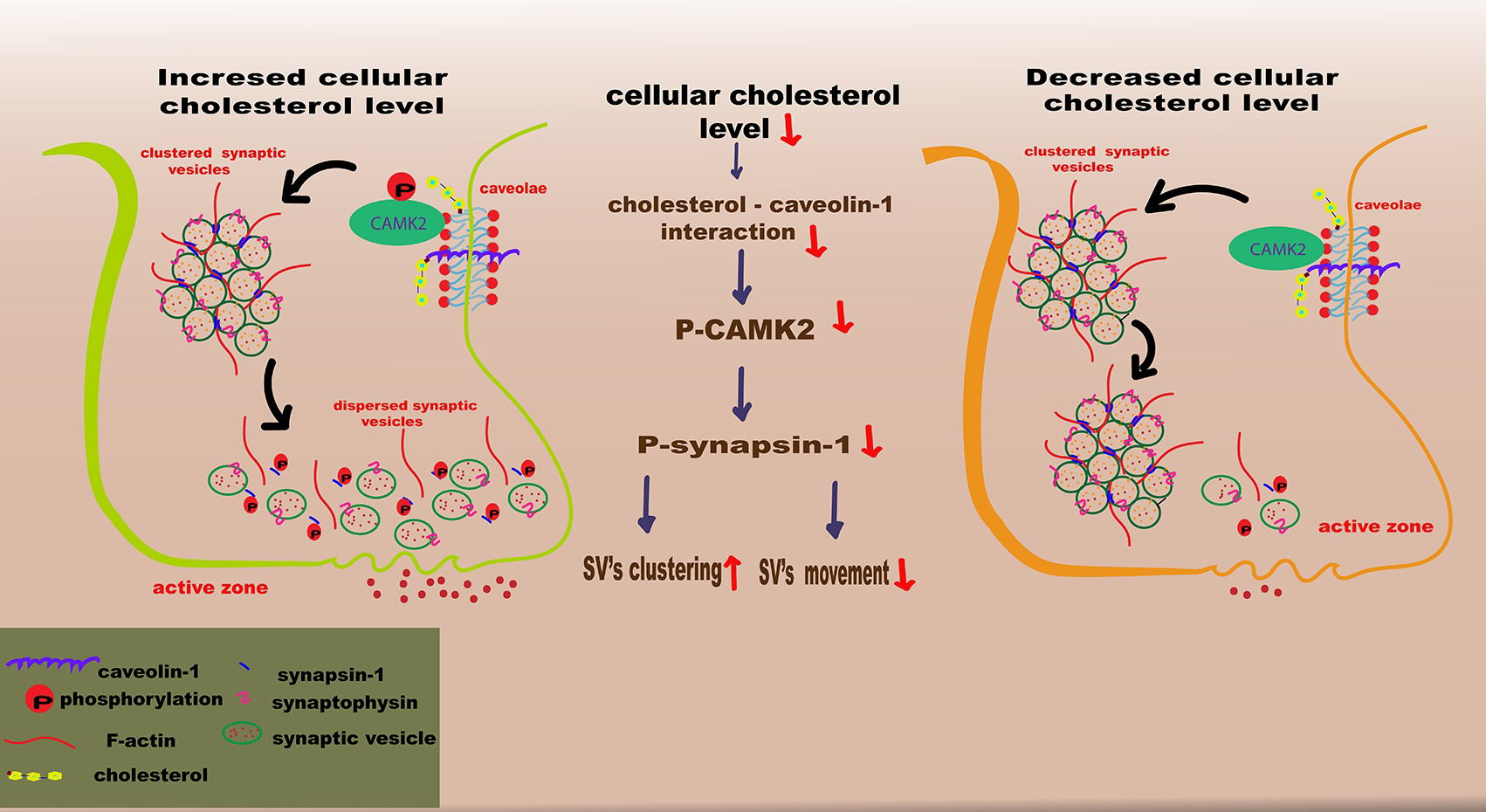

In conclusion, a model of cellular cholesterol loss involving silencing of DHCR24 was used to demonstrate that cellular cholesterol deficiency could inhibit phosphorylation of Calcium/CAMK2. This results in the inhibition of synapsin-1 phosphorylation, disruption of SV mobility, and a subsequent decrease in the formation of RRP from RP, potentially in a lipid raft-associated manner (Fig. 6). The present study also demonstrated that cellular cholesterol deficiency downregulated the expression of synaptophysin protein, which can decrease SV biogenesis and synaptic plasticity. Importantly, our study underscores the importance of cellular cholesterol deficiency/loss in synaptopathy during AD, and provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between loss of cellular cholesterol and AD pathogenesis.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Schematic illustration of how the loss of cellular cholesterol could disrupt synaptic vesicle mobility. In this model for the depletion/loss of cellular cholesterol through silencing of DHCR24, the cholesterol deficiency results in downregulation of the caveolae protein caveolin-1, leading to disruption of the caveolae composition and hence to the inhibition of CAMK2 phosphorylation. Further, the decrease of phosphorylated CAMK2 (p-CAMK2) induces the reduction of phosphorylated synapsin-1 (p-synapsin-1) level, which could reduce the replenishment of the readily-releasable pool (RRP) from reserve pool (RP), impairing synaptic vesicles mobility. SV, vesicle. The figure was created by Adobe Illustrator 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

All data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

AQ contributed to the majority of the experimental work, statistical analysis, and writing of the manuscript. MZ contributed to part of the experimental work. HZ contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing. KY contributed to statistical analysis, and partly writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau, Shanghai, China (201740209); the Shanghai Jinshan District Key Medical Foundation, Shanghai, China (JSZK2019A06); the Jinshan Hospital of Fudan University Development Foundation (HBXK-2022-2).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.