1 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, 200032 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Zhongshan Hospital (Xiamen), Fudan University, 361006 Xiamen, Fujian, China

3 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Affiliated Jiangyin Hospital of Nantong University, 214400 Jiangyin, Jiangsu, China

4 Department of Vascular Surgery, General Surgery Clinical Center, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 200025 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

This study investigates the role of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-specific peptidase 5 (SENP5), a key regulator of SUMOylation, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), a lethal disease, and its underlying molecular mechanisms.

Differentially expressed genes between ESCC mouse oesophageal cancer tissues and normal tissues were analysed via RNA-seq; among them, SENP5 expression was upregulated, and this gene was selected for further analysis. Immunohistochemistry and western blotting were then used to validate the increased protein level of SENP5 in both mouse and human ESCC samples. The Kaplan‒Meier method and multivariate analysis were used to analyse the relationship between SENP5 expression and ESCC prognosis. Stable SENP5-knockdown (KD) cell lines and conditional knockout (cKO) mice were established to verify the biological function of SENP5. Further RNA-seq comparisons between short hairpin SENP5 (shSENP5)- and short hairpin negative control (shNC)-transfected ESCC cell lines were conducted, and the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)—SLC1A3 axis was identified through bioinformatics analysis. The correlation of SENP5 with signalling pathway components was validated via real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), western blotting (WB), and immunoprecipitation.

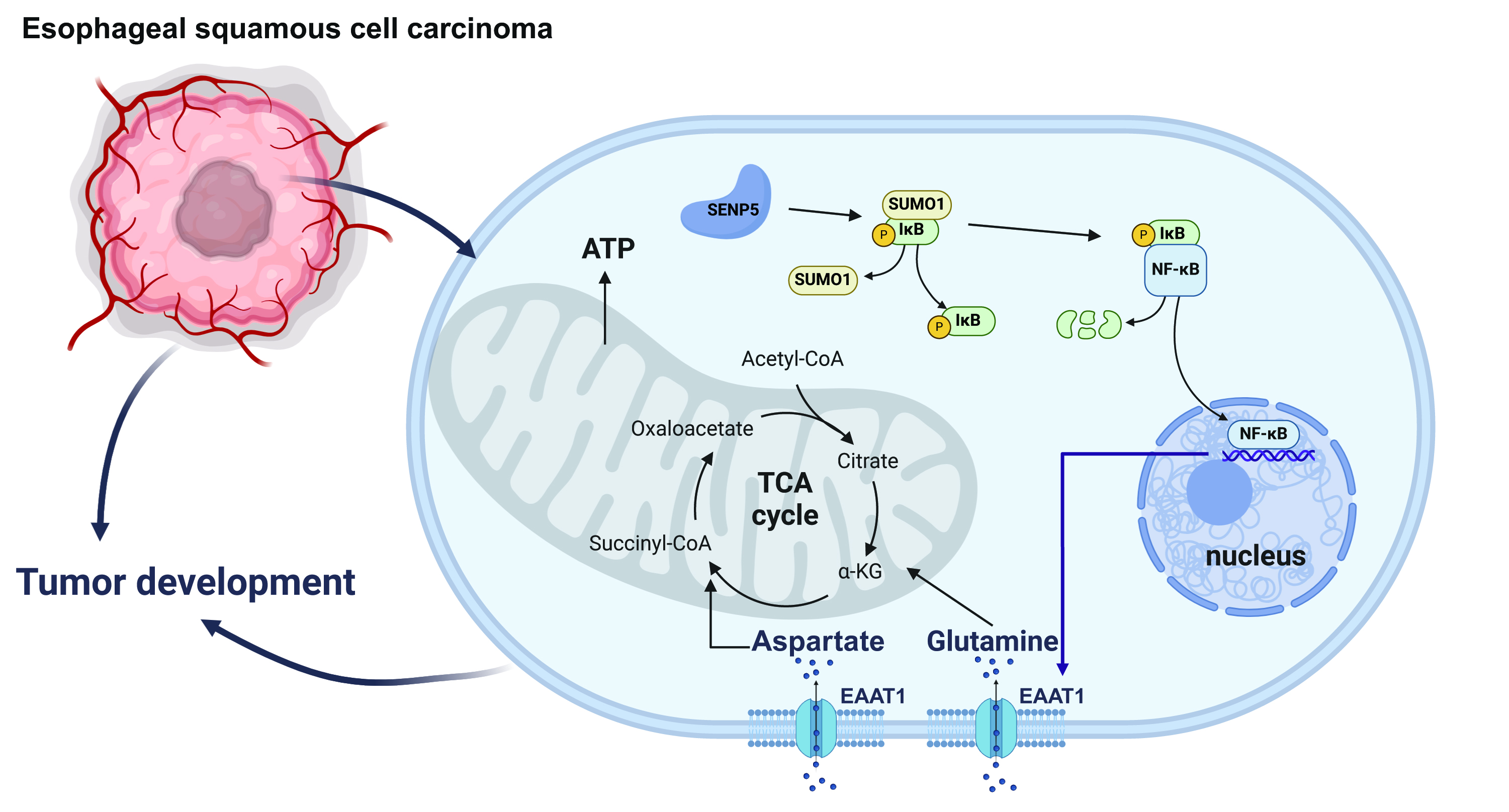

Our study revealed that SENP5 was upregulated in human and mouse ESCC samples, and clinical data analysis revealed a correlation between high SENP5 expression and poor patient prognosis. SENP5 knockdown inhibited tumorigenesis and growth in vivo and suppressed the proliferation, migration, and invasion of ESCC cell lines in vitro. Our study also revealed that SENP5 knockdown enhanced the SUMO1-mediated SUMOylation of NF-kappa-B inhibitor alpha (IκBα), thereby inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB–SLC1A3 axis, which subsequently suppresses ESCC cell energy metabolism and impedes ESCC progression.

Suppression of SENP5 slows the development of ESCC by inhibiting the NF-κB‒SLC1A3 axis through SUMO1-mediated SUMOylation of IκBα. Our research suggests that SENP5 could serve as a prognostic indicator and a target for therapeutic intervention for ESCC patients.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- SENP5

- oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- SLC1A3

- NF-κB

Oesophageal cancer is a common and highly fatal gastrointestinal malignancy [1]. Every year, more than 500,000 people worldwide die from oesophageal cancer [2]. Oesophageal cancer has two major histological types: oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and oesophageal adenocarcinoma [3]. ESCC is the most common subtype, accounting for 90% of all oesophageal cancer cases, and it is particularly prevalent in China [4]. Nowadays, surgery remains the main treatment method [5]. Although other therapeutic strategies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy, have been applied, it has been reported that the responsiveness of oesophageal cancer patients to these therapies is relatively low [6], leading to a low 5-year survival rate of less than 20% [7].

Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins are a group of ubiquitin-like proteins that covalently conjugate to substrate proteins and regulate their functions [8]. The posttranslational modifications induced by SUMO are reversible, and the process is referred to as SUMOylation [9]. There are three major SUMO proteins. SUMO-1 usually modifies a substrate as a monomer; however, SUMO-2/3 can form poly-SUMO chains [10]. Dysregulation of SUMOylation is associated with many diseases, especially cancer [11, 12, 13]. SUMO-specific peptidases (SENPs) can dissociate SUMO proteins from substrate proteins, thus playing a critical role in SUMO recycling [14]. SUMO-specific peptidase 5 (SENP5), an important member of the SENPs family [15], is a critical factor in the occurrence and development of many cancers, including colorectal cancer, osteosarcoma and oral squamous cell carcinoma [16, 17, 18]. However, the role of SENP5 in ESCC remains unclear.

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-

The solute carrier family 1 member 3 (SLC1A3) gene encodes excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (EAAT1) [21], a glial transporter that removes glutamate and aspartate at the synaptic cleft and extrasynaptic sites. The revious study has shown that solute carrier family (SLC) transporters are essential for nutrient uptake, exchange, and movement of waste products [22]. The expression of some SLC transporters is upregulated in cancer, which provides access to various nutrients from the extracellular space to tumours, increasing their energy metabolism [23, 24].

This study revealed a relatively high level of SENP5 expression in oesophageal cancer tissues from both ESCC patients and mice. Suppression of SENP5 significantly inhibited ESCC growth. Furthermore, SENP5 inhibition reduces the activation of NF-

Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China) provided paraformaldehyde and puromycin, while Roche Pharmaceuticals Consulting (Shanghai, China) supplied TriPure isolation reagent. Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) provided reagents such as ethanol, chloroform, xylene, neutral resin, and isopropanol. Takara Biomedical Technology (Beijing, China) provided the PrimeScript™ PLUS RT-PCR Kit. Cell culturing medium was acquired from HyClone, Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China). Penicillin-streptomycin and foetal bovine serum were purchased from Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China). Antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Shanghai, China), and Prof. Jinke Cheng generously provided the plasmids.

A chemiluminescence imaging analyzer (las-4000) from Fujifilm (Shanghai, China) was used. An inverted microscope and a paraffin sectioning machine were obtained from Leica (Beijing, China). Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China) provided the NanoDrop 2000, CO2 cell incubator and biosafety cabinet. Eppendorf (Oldenburg, Germany) supplied the conventional PCR instrument and a 4 °C high-speed freezing centrifuge. The electrophoresis apparatus was from Tianneng Technology (Shanghai, China), and the fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (LC480) was from Roche.

Unrelated Chinese Han individuals were recruited for this study. ESCC patients who were diagnosed from January 2015 to January 2019 and underwent surgical resection at Zhongshan Hospital were included. Prior to surgery, each patient underwent a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) (uMI 780, United Imaging, Shanghai, China) scan. Tissue microarrays were generated from 200 ESCC samples, none of which were subjected to neoadjuvant treatment. The clinical profiles of these patients are provided in Table 1. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (B2022-271R), and patients or their families/legal guardians provided written informed consent. Additionally, we obtained the cancer genome atlas-esophageal carcinoma (TCGA-ESCA) data from the UCSC Xena platform (https://xenabrowser.net/) from 11 normal tissue samples and 94 ESCC samples.

| Level | SENP5-High | SENP5-Low | p value | |

| (n = 100) | (n = 100) | |||

| Sex (%) | 0.236 | |||

| Female | 19 | 26 | ||

| Male | 81 | 74 | ||

| Age (%) | 0.090 | |||

| 57 | 45 | |||

| 43 | 55 | |||

| Total lymph node dissection (mean | 25.0 (17.8, 32.0) | 25 (19.0, 32.0) | 0.916 | |

| pT Stage (%) | ||||

| T1–2 | 26 | 85 | ||

| T3–4 | 74 | 15 | ||

| pN Stage (%) | 0.506 | |||

| N0–1 | 87 | 90 | ||

| N2+ | 13 | 10 | ||

| Differentiation (%) | 0.021 | |||

| High/moderate differentiation | 62 | 77 | ||

| Poor/no differentiation | 38 | 23 | ||

| SUVmax (%) | ||||

| 87 | 51 | |||

| 13 | 49 | |||

| Surgical procedure (%) | ||||

| Ivor Lewis | 21 | 4 | ||

| McKeown | 61 | 90 | ||

| Sweet | 18 | 6 | ||

| Ki-67(%) | 0.035 | |||

| Low | 19 | 32 | ||

| High | 81 | 68 | ||

| Location (%) | 0.893 | |||

| Up | 11 | 14 | ||

| Middle | 38 | 37 | ||

| Low | 48 | 45 | ||

| EG junction | 3 | 4 | ||

p

C57BL/6 wild-type mice were purchased from SLAC Laboratory Animals (Shanghai, China). Senp5 flox/flox mice were genetically modified by BRL Medicine (Science&Technology Park, Shanghai, China), while ED-L2-Cre mice were created by GemPharmatech Co. (Shanghai, China), Ltd. By breeding Senp5 flox/flox mice with ED-L2-Cre mice, we produced knockout mice specifically targeting the oesophageal squamous epithelium. All the mice were kept under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions and provided with sterile water and food. The experimental protocols for the animals complied with the guidelines of the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (approval number: A-2022-082). To establish an ESCC mouse model, 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide (catalogue no. N8141, Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) was added to the drinking water of six-week-old male mice for 16 weeks at a concentration of 100 µg/mL. After receiving normal water for an additional 8 weeks, the oesophageal tissues of the mice were harvested for analysis. The mice were anaesthetized via 3% isoflurane inhalation as needed and euthanized via cervical dislocation after the experiments.

Bulk RNA sequencing was conducted by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Briefly, oesophageal tissues were collected from the mice, the squamous epithelium was isolated, and the samples were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. A Geo-seq protocol was used to extract RNA and prepare cDNA for sequencing. The sequencing libraries were subsequently established and evaluated with an mRNA Library Prep Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Trim Galore version 0.4.4 (https://biodockerfiles.github.io/trim-galore-0-4-4/) was used to eliminate low-quality reads and adaptor sequences. Clean reads were aligned to the mm10 genome using Bowtie2 version 2.5.4 (https://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml) with default settings (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012), and uniquely mapped reads were summarized with featureCounts from the Subread package. The RNA-seq data were aligned to the GRCm39 mouse genome and the GRCh38 human genome with HISAT2 version2.1.0 (https://bioweb.pasteur.fr/packages/pack@hisat2@2.1.0) with the default settings. The gene expression matrix, which was based on raw read counts, was analysed with DESeq2. Genes were classified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) if they exhibited at least a twofold change and had a false discovery rate-adjusted p value of 0.05. Bioinformatics analyses, including heatmap generation with the “pheatmap” package, colour palette customization with “ggsci”, and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis with “enrichGO”, were performed using R software version 4.3.0.

We stored patient tumour and control tissues in preservation solution and sent them to Beijing SeekGene Biosciences Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The company performed oil‒water separation and assessed cell viability and clustering rates. If the standards were met, the samples were sequenced via the 10

Tissue samples from ESCC patients and healthy controls were collected at Zhongshan Hospital. The institution’s ethics committee approved this study, and all patients provided written informed consent. Samples were also collected from Senp5 flox/flox; Edl2-Cre genotype mice. All the samples were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) for 24 hours and then dehydrated via a series of alcohol and xylene solutions (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) before being embedded in paraffin blocks. A microtome was used to cut the paraffin blocks into 5-micron-thick slices, which were placed onto glass slides. These slides were dewaxed with xylene, treated with an alcohol gradient, rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide methanol (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After further rinsing with PBS, antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in citrate buffer (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) at 95 °C, followed by another wash with PBS. After 30 minutes of blocking with 10% goat serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) at room temperature, the slides were incubated with diluted SENP5 antibody (1:500, Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China, 19529-1-AP) or Ki67 antibody (1:500, Abcam, Shanghai, China, ab15580) overnight at 4 °C. After being washed with PBS, the slides were incubated with a biotin-labelled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000, Abcam, Shanghai, China) for half an hour at 37 °C, followed by another PBS wash and the addition of biotin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The slides were incubated again at 37 °C for 30 minutes, washed with PBS, and stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 2 minutes. Next, the slides were rinsed with tap water, counterstained with haematoxylin (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), dehydrated through an alcohol and xylene gradient, and finally sealed with neutral resin (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). A tissue microarray was prepared, and SENP5 staining was carried out by Runnerbio Technology (Shanghai, China). The images were analysed with the TissueFAXS Plus system (version 7.1, TissueGnostics, Beijing, China). According to the results of the tissue microarray analysis, the 200 patient samples were classified into SENP5-high and SENP5-low groups (100 patients per group).

Briefly, subcutaneous injections were administered on the right side of the backs of 8-week-old male athymic nude mice. After three weeks of regular feeding, the subcutaneous tumours on the backs of the mice were completely excised. The experimental procedures for the animals complied with the guidelines set forth by the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (approval number: A-2022-082).

The human oesophageal squamous cell lines KYSE30, KYSE150, KYSE180, TE1, TE10, and EC109 were obtained from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) in February 2023. RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin was used for cell culture. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. All the cell lines were validated via short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. Cell authentication was performed via the following methods: an Axygen genomic extraction kit (Corning Incorporated, Shanghai, China) was used to extract DNA, and a 20-STR amplification protocol was used for amplification. The STR loci and sex gene amelogenin were detected on an ABI 3730XL genetic analyser (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China). The typing results of the tested cells were compared with the STR data of 2455 cell lines recorded in the ExPASy (https://www.expasy.org/), ATCC (https://www.atcc.org/), DSMZ (https://www.dsmz.de/), JCRB (https://cellbank.nibiohn.go.jp/english), and RIKEN (https://www.riken.jp/en/) databases. The DNA typing results of the six cell lines were completely matched in the cell line search, and no multiallelic genes were identified in any of the six cell lines. The last time the cell lines were tested was in December 2022.

The VectorBuilder Company (Guangzhou, China) provided the interfering RNA lentivirus of SENP5 and the control lentivirus (shSENP5 #1: CAGAAACTGAAAGAGAAATTA; shSENP5 #2: AGAAGTCCTTGGAAGATTAAA). Transfections were conducted according to the virus infection instructions, and the cell lines were screened with 1 µg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) after 48 hours of infection.

Yeasen Biotech (Shanghai, China) provided the Cell Counting Kit-8, and cell proliferation was measured every 24 hours according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the colony formation assay, an appropriate number of cells were cultured in 6-well plates. After 2 weeks of incubation in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the cells were stained with crystal violet and scored under an inverted microscope (Leica, Beijing, China).

A sterile 10-µL pipette tip (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to scratch the monolayer surface to create wounds, and images of the wound closure and gaps were taken after 24 hours. For the migration assay, 200 µL of single-cell suspension in serum-free medium was added to the upper chamber of a 24-well plate. The lower chamber was filled with 600 µL of RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) per well. The cells in the upper chamber were removed after 24 hours, and the remaining cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet (Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

Glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and ATP levels were measured via the following assay kits: glutamic acid (Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA, E-BC-K903-M), aspartic acid (Amplite, Pleasanton, CA, USA, 13828), and ATP (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, S0026). Briefly, the cells were treated with lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After centrifugation to remove cell debris, the supernatant was added to the substrate mixture. The luminescence of ATP was recorded in an illuminometer with an integration time of 10 s per well. The optical densities of glutamic acid and aspartic acid were recorded with a colorimetric microplate reader (Tecan, Shanghai, China) at OD450 nm.

The cells were harvested, lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and centrifuged at 13,000

For Western blot analysis, the cells were harvested after treatment, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in lysis buffer containing 1% SDS. After loading buffer was added, the samples were heated at 95 °C for 10 minutes. A 10 µL sample was loaded onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis and then electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% milk for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with gentle agitation in dilution buffer containing antibodies for the following proteins: SENP5 (1:1000, Proteintech, 19529-1-AP), SUMO1 (1:1000, Abcam, ab32058),

All the experiments were performed three times independently, and representative results are presented. The results are summarized as the means with standard deviations (means

We obtained the sequencing data of 94 ESCC tissues and 11 normal tissues from the TCGA-ESCA database to analyse the differentially expressed genes in oesophageal cancer. The results revealed a greater SENP5 expression level in oesophageal cancer tissue than in normal oesophageal tissue (Fig. 1A). RNA-seq analysis revealed that Senp5 expression was significantly increased in the oesophageal cancer tissues of ESCC mice (Fig. 1B). The scRNA-seq results also revealed that the SENP5 expression level was increased in ESCC cells (Fig. 1C,D). Then, we further collected human and mouse ESCC specimens (Supplemental Fig. 1A) and performed WB experiments and found the protein levels of SENP5 also increased in the ESCC tissues of both mice and humans. The protein levels of SENP5 also increased in the ESCC tissues of both mice and humans (Fig. 1E,F). In addition, immunohistochemical analysis revealed a greater level of SENP5 expression in oesophageal cancer tissues than in normal tissues (Fig. 1G). These results demonstrate that SENP5 is highly expressed in ESCC tissues and may play a role in the development of ESCC.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. SUMO-specific Peptidase 5 (SENP5) is more highly expressed in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissue than in normal tissue. All experiments were performed at least three times on cells. (A) SENP5 expression in normal oesophageal tissues (n = 11) and ESCC tissues (n = 94) from the the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) RNA-seq dataset. (B) Bulk RNA-seq transcriptome analysis showing the expression of Senp5 in mouse normal and oesophageal cancer tissues. The data are presented as the means

To verify the role of SENP5 in ESCC, we analysed the expression of SENP5 in different ESCC cell lines and found that KYSE150 and EC109 cells presented relatively high expression (Fig. 2A). We subsequently established stable SENP5 knockdown (KD) in these two cell lines and verified the knockdown efficiency via Western blotting (Fig. 2B). CCK8 and colony formation assays revealed that the proliferation ability of shSENP5 oesophageal cancer cells was significantly inhibited (Fig. 2C,D). Wound-healing and Transwell invasion assays revealed that the cell migration/invasion ability of the shSENP5 group was also significantly decreased (Fig. 2E,F). These results demonstrate that SENP5 knockdown can inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasion of ESCCs in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. SENP5 knockdown inhibits the proliferation and migration of ESCC cells. All experiments were performed at least three times on cells. (A) Western blot analysis of SENP5 protein levels in seven ESCC cell lines. (B) Western blot analysis of SENP5 protein levels in SENP5-knockdown or negative control (NC) EC109 and KYSE150 cells. (C) CCK8, (D) colony formation, (E) wound healing (scale bar = 100 µm), and (F) Transwell migration assays were performed in EC109 and KYSE150 cells with SENP5 knockdown, scale bar = 50 µm. The data are presented as the means

To investigate whether SENP5 influences ESCC growth in vivo, nude mice were subcutaneously injected with shNC- or shSENP5-transfected cells. The results revealed that SENP5 knockdown decreased tumour size and weight in vivo (Fig. 3A,B). In Senp5 conditional knockout (cKO) mice, we also observed fewer tumours in an ESCC model established using 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide (Fig. 3C–E). We subsequently conducted immunohistochemical Ki-67 staining of oesophageal tissue from Senp5 cKO mice and Senp5 flox/flox mice. Ki-67 is an antigen that is expressed in the nucleus and is closely related to cell proliferation. The results revealed that Senp5 knockout decreased Ki-67 expression in primary oesophageal cancer tissues from mice (Fig. 3F,G). These results suggest that targeting SENP5 in vivo inhibits the development of ESCC.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. SENP5 deficiency inhibits tumour growth in vivo. (A,B) Tumour volume and weight of shNC- and shSENP5-transfected xenografts of EC109 cells are shown (n = 6 mice/group). (C) Genotype validation and Western blotting of oesophageal squamous epithelium-specific Senp5 conditional knockout mice. (D,E) Senp5 conditional knockout (cKO) mice had a lower incidence of oesophageal tumours than Senp5 fl/fl mice did. The red arrows in the plot indicate oesophageal tumours. The number of oesophageal tumours per mouse in Senp5 fl/fl mice was compared to that in cKO mice (n = 6 mice/group). (F) Senp5 cKO mice presented decreased Ki67 expression in tumour tissues compared with Senp5 fl/fl mice. Scale bar: 200 µm (left), 100 µm (right). (G) The percentage of Ki67-positive cells was plotted for both Senp5 cKO and Senp5 fl/fl mice (n = 6 mice/group). The significance level is represented by *p

To validate the association between SENP5 expression and the prognosis of ESCC patients, we constructed a tissue chip using oesophageal cancer samples collected from Zhongshan Hospital. All patients underwent radical oesophageal cancer surgery and had not received other treatments. SENP5 expression in oesophageal cancer tissues was analysed via software, and samples were categorized into high SENP5 expression and low SENP5 expression groups in a bifurcated manner (n = 100 patients/group) based on expression intensity (Fig. 4A,B). We subsequently conducted a correlation analysis between SENP5 expression in oesophageal cancer tissues and the clinical characteristics and prognosis of 200 patients. The characteristics included sex, age, lymph node metastasis, pathological T stage, pathological N stage, differentiation, standardized uptake value max (SUVmax), surgical approach, Ki-67 expression level, and tumour location. The results revealed that patients in the high SENP5 expression group presented a higher pathological T stage (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. SENP5 expression is correlated with the pathological stage and prognosis of oesophageal cancer patients. (A) Patients were divided into high and low groups according to SENP5 expression level in tissue microarrays in a bifurcated manner (n = 100 patients/group), scale bar = 500 µm. (B) Density of SENP5 in high-expression and low-expression groups determined via ImageJ software (version 1.53t, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MA, USA). (C,D) Kaplan‒Meier survival curves were generated based on SENP5 expression. (E) Forest plot analysis of overall survival rates. (F) Forest plot analysis of relapse-free survival rates. (G) Forest plot analysis of relapse-free survival rates after incorporating Ki-67 and SUVmax into the multivariate analysis. (H) Forest plot analysis of overall survival rates after incorporating Ki-67 and SUVmax into the multivariate analysis. The significance level is represented by **p

To explore the mechanisms underlying SENP5 involvement in ESCC, we performed RNA-Seq analysis on shNC and shSENP5 in both the KYSE150 and EC109 cell lines. GO enrichment analysis revealed that SENP5 knockdown inhibited the amino acid transport pathway in oesophageal cells (Fig. 5A). We subsequently conducted a heatmap analysis and volcano plot analysis of the differentially expressed genes in the amino acid transport pathway and found that SLC1A3 exhibited the most significant changes (Fig. 5B,C; Supplemental Fig. 1B,C). RT‒qPCR and Western blotting confirmed that SENP5 knockdown inhibited SLC1A3 expression in ESCC cells (Fig. 5D,E). Excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (EAAT1) facilitates the transport of acidic amino acids within cells [25]. Moreover, EAAT1 plays a vital role in shuttling glutamic acid (Glu) and aspartic acid (Asp) between the cytoplasm and mitochondria, thereby sustaining the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and ATP synthesis within mitochondria, which is essential for cellular energy metabolism [25]. We assessed the levels of Glu, Asp and ATP and found a significant reduction in these levels after SENP5 knockdown (Fig. 5F–H), whereas EAAT1 overexpression restored the levels of Glu, Asp, and ATP in shSENP5 ESCC cells (Fig. 6A,C–E). Furthermore, the CCK8 results revealed that overexpression of EAAT1 could restore the proliferation ability of shSENP5 ESCC cells (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that SENP5 knockdown can inhibit amino acid and energy metabolism by suppressing the expression of SLC1A3, thereby inhibiting ESCC development.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. SENP5 knockdown inhibits amino acid and energy metabolism in ESCC via the downregulation of SLC1A3. All experiments were performed at least three times on cells. (A) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the different pathways. (B) Heatmap of representative amino acid transport pathway-related genes differentially expressed between shNC- and shSENP5-transfected KYSE150 cells. (C) Volcano plot analysis of differentially expressed genes between shNC- and shSENP5-transfected KYSE150 cells. (D) Real time-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‒qPCR) analysis and (E) Western blotting of SLC1A3 expression levels in shNC- and shSENP5-transfected EC109 and KYSE150 cells. (F,G) Colorimetric analysis of glutamate and aspartic acid levels in shNC- and shSENP5-transfected EC109 and KYSE150 cells. (H) Colorimetric analysis of ATP levels in shNC- and shSENP5-transfected EC109 and KYSE150 cells. The significance level is represented by **p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Inhibition of SENP5 suppresses the NF-

ChIP-Atlas database analysis revealed that NF-

The results of this study provide insights into the role and mechanism of SENP5 in the occurrence and development of ESCC. SENP5 knockdown in human and mouse ESCC cells inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion. Further investigation revealed that SENP5 knockdown increases the SUMOylation of I

In our study, RNA-seq revealed that SENP5 knockdown inhibited the amino acid transport pathway in oesophageal cells, with the most significant changes observed in SLC1A3. Cancer cells require glutamine to drive various metabolic processes, particularly the TCA cycle [26], transamination [27], and redox balance [27]. It has been reported that some SLC transporters, such as SLC1A5, can transport glutamine and are highly expressed in many cancers [28], including lung and oesophageal cancer, thus participating in tumour energy metabolism and development. However, owing to compensatory reactions [29], their roles are not observed in all tumour groups. Our RNA-seq results suggest that SLC1A3 may play a similar regulatory role in energy metabolism in oesophageal cancer. Therefore, SENP5 may regulate the occurrence and development of ESCC by modulating the function of SLC1A3. Prior research has demonstrated the regulatory influence of the NF-

Our study integrates experimental results with clinical data. Both in vitro cell experiments and in vivo animal experiments confirmed that SENP5 knockdown reduces the proliferation, migration, and invasion of ESCC, which is consistent with clinical data collected from oesophageal cancer patients. These clinical data indicate that oesophageal cancer patients with high SENP5 expression have significantly greater T stages, Ki67 positivity rates, and primary lesion SUVmax values, indicating more robust tumour proliferation, migration, and invasion abilities. Moreover, the survival period is shorter in oesophageal cancer patients with high SENP5 expression than in those with low SENP5 expression, suggesting a close association between SENP5 expression and poor prognosis in patients with oesophageal cancer. After incorporating Ki-67 and SUVmax into the multivariate analysis, SENP5 expression was still associated with relapse-free survival, suggesting that SENP5 may influence ESCC prognosis through mechanisms beyond its impact on SUVmax and Ki-67 level. However, there was no statistically significant association between SENP5 expression and overall survival in the multivariate analysis, which may be due to the influence of numerous factors on overall survival, leading to potential confounding bias. Previous studies have shown that SENP5 is associated with poor prognosis in other tumours [17, 18, 33], and our study provides evidence supporting the role of SENP5 in oesophageal cancer.

SENP5 expression is upregulated in ESCC cells, and high SENP5 expression is closely related to poor prognosis. Suppression of SENP5 inhibits the NF-

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CXD, YFH, XYY: Designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Collected and analyzed data; Wrote the paper. JMG, ZZ, TZ, RFW: technique support. SYZ: Designed the experiments and supervision. LJT, GPY: Designed the experiments, Supervision, and Funding acquisition. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

For patients, this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (B2022-271R), and patients or their families/legal guardians provided written informed consent and conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. For mice, the experimental protocols for the animals complied with the guidelines set forth by the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and was approved by the Ethics Committee (Approval number: A-2022-082).

We would like to acknowledge Prof. Jinke Cheng for providing the plasmids and Dr. Wenhan Wang for the technical advices.

Dr. Guiping Yu was funded by the Training Team for the Leading Expert Team of “Famous Doctors in Jiyang” in Jiangyin City - Tan Lijie Expert Team, grant number: RC2023-005. Dr. Zhe Zhang was funded by the Research project of the Jiangyin Health Commission, grant number: Q202206. Dr. Lijie Tan was funded by the 2021 Clinical Research Navigation Program of Shanghai Medical College of Fudan University, grant number: 2020ZSLC5. Dr. Shaoyuan Zhang was funded by the Outstanding Resident Clinical Postdoctoral Program of Zhongshan Hospital Affiliated with Fudan University, grant number: 2024M760551. Dr. Chaoxiang Du was funded by The Xiamen Natural Science Foundation Project in 2022, grant number: 2022FCX012503010383.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL27047.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.