1 Institute of Translational Medicine, Shanghai University, 200444 Shanghai, China

2 Institute of Burn Research, The First Affiliated Hospital, State Key Lab of Trauma, Burn and Combined Injury, Chongqing Key Laboratory for Disease Proteomics, Third Military Medical University (Army Medical University), 400038 Chongqing, China

3 Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Zibo Municipal Hospital, 255400 Zibo, Shandong, China

4 MPA Key Laboratory for Research and Evaluation of Tissue Engineering Technology Products, Medical College, Nantong University, 226001 Nantong, Jiangsu, China

5 Department of Breast Thyroid Surgery, Zibo Central Hospital, 255036 Zibo, Shandong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Dexamethasone has proven life-saving in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and COVID-19 cases. However, its systemic administration is accompanied by serious side effects. Inhalation delivery of dexamethasone (Dex) faces challenges such as low lung deposition, brief residence in the respiratory tract, and the pulmonary mucus barrier, limiting its clinical use. Neutrophil cell membrane-derived nanovesicles, with their ability to specifically target hyper-activated immune cells and excellent mucus permeability, emerge as a promising carrier for pulmonary inhalation therapy.

We designed a novel UiO66 metal-organic framework nanoparticle loaded with Dex and coated with neutrophil cell membranes (UiO66-Dex@NMP) for targeted therapy of severe pneumonia. This was achieved by loading Dex into UiO66 pores and subsequently coating with neutrophil membranes for functionalization.

Drug release experiments revealed UiO66-Dex@NMP to exhibit favorable sustained-release properties. Additionally, UiO66-Dex@NMP demonstrated excellent targeting capabilities both in vitro and in vivo. In a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pneumonia, UiO66-Dex@NMP significantly reduced lung inflammation compared to both the control model and Dex administered via inhalation. Histopathological analysis further confirmed UiO66-Dex@NMP’s ability to alleviate lung tissue damage.

UiO66-Dex@NMP represents a novel and safe inhaled delivery carrier for Dex, offering valuable insights into the clinical management of respiratory diseases, including severe pneumonia.

Keywords

- dexamethasone

- MOF

- neutrophil cell membrane

- inhaled delivery

- severe pneumonia

Severe pneumonia (SP) is a major respiratory disease and a leading cause of death among children and the elder [1, 2, 3]. SP can be caused by infections from various pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, mycoplasma, and chlamydia. Among these, bacterial and viral infections are the two most common causes [4, 5]. The COVID-19 virus, in particular, has been associated with severe lung injury and fatality [6]. Macrophage dysfunction plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of severe lung injury, including their involvement in cytokine storms [7, 8]. Consequently, the regulation of macrophage activity is of utmost importance. Dexamethasone (Dex) has emerged as the first and most effective drug in saving the lives of patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation [9]. The glucocorticoid receptor, which is the receptor for dexamethasone, is widely expressed in various cells throughout the body [10]. Due to this high expression, dexamethasone has significant side effects and should be used with caution in clinical settings. Dex exhibits significant side effects and is therefore used with caution in clinical practice. Both oral and intravenous formulations lack pulmonary targeting, leading to systemic toxicity [11]. Nebulized administration represents an ideal method for local delivery. In clinical practice, Dex is commonly administered as dexamethasone sodium phosphate. While inhaled preparations have effectively addressed the issue of pulmonary targeting, they still need to overcome the pulmonary mucus barrier. Furthermore, the deposition rate of nebulized dexamethasone sodium phosphate in the lungs is low, and its residence time in the respiratory tract is brief. Hence, optimizing dosage forms is essential to address these challenges.

Biomimetic functionalized materials provide a new method for the targeting treatment [12, 13]. Recent advances in cell membrane mediated drug delivery may help to improve SP treatment efficacy by targeting the potent corticosteroid drug to hyper-activated immune cells [14], offering many new opportunities to push the limit of current therapeutics [15, 16]. Neutrophils can typically rush to inflammatory sites within the body, eliminate pathogens, and ultimately be cleared by macrophages [17, 18]. The targeting ability of neutrophils is facilitated by the interaction of adhesion molecules and integrins, enabling precise delivery of anti-inflammatory drugs to hyper-activated macrophages.

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOF) are formed through the coordination bonding of metal ions and organic ligands, resulting in a highly ordered porous structure with a large surface area, thus exhibiting excellent adsorption properties [19, 20]. In terms of drug delivery, embedding drug molecules into the pores of MOF materials enables controlled release and targeted delivery of drugs [21]. This controlled release mechanism helps to improve the therapeutic effect of drugs while reducing side effects. MOFs have been reported as a viable option for nebulization therapy in the throat due to the effective deposition of micrometer-sized MOF particles within the throat region [22]. Given the limitations of existing respiratory inhalation carriers, there is significant value in developing novel MOF-based pulmonary drug delivery carriers.

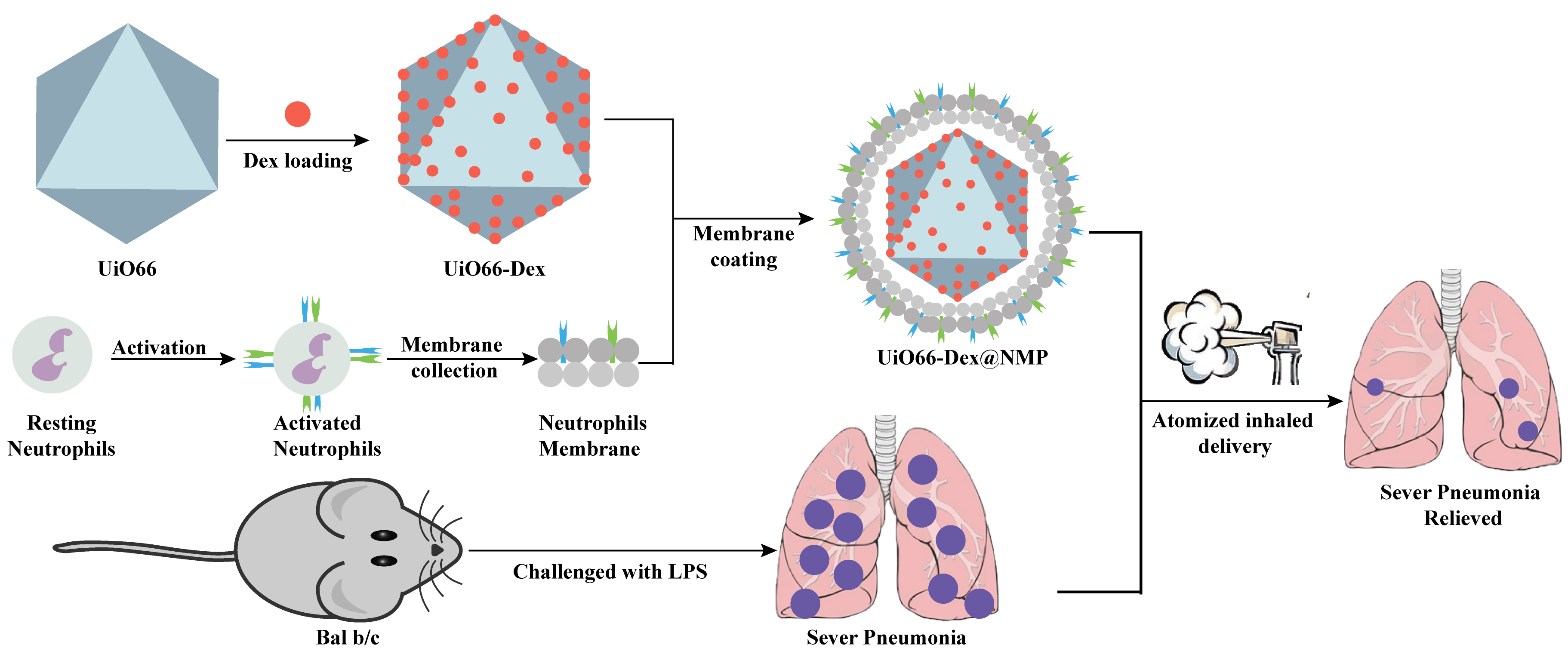

In this study, we prepared Dex-loaded UiO66 (UiO66-Dex), subsequently, the surface was coated with neutrophil membranes. UiO66 Metal-Organic Frameworks nanoparticle loaded with dexamethasone (Dex) and coated with neutrophil cell membranes (UiO66-Dex@NMP) was explored inhalation therapy in mice model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced pneumonia (Fig. 1). We anticipate to improve the dosage form and administration of Dex in combination with the current clinical needs.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of UiO66-Dex@NMP and animal experiment process. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; UiO66-Dex@NMP, UiO66 Metal-Organic Frameworks nanoparticle loaded with dexamethasone (Dex) and coated with neutrophil cell membranes.

Benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid (BDC), Zirconium (IV) oxide chloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2

RAW264.7 cells and DMEM were purchased from Shanghai FuHeng Biology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. Culture conditions: gas phase: 95% air, 5% carbon dioxide. Temperature: 37 °C, incubator humidity maintained at 70%–80%. Cryoprotectant solution: 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (C0226, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), 10% DMSO, prepared fresh and used immediately. Healthy, 8-week-old, male BALB/c mice of SPF (Specific Pathogen Free) grade were purchased from Cavens Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, Jiangsu, China). All mice weighed between 20 and 25 grams. The animal experiment was approved under approval number AMUWEC20210417, and all procedures were conducted in strict compliance with the relevant regulations and guidelines set by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Third Military Medical University.

After being anesthetized with 100% carbon dioxide for five minutes, the BALB/c mouse underwent euthanasia to ensure complete cessation of life. After the euthanasia of the BALB/c mouse, the femur and tibia were surgically removed. Subsequently, the bone ends were neatly trimmed, and an RPMI 1640 solution, enriched with 10% FBS and 2 mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), was aspirated to flush out the bone marrow cells. To lyse the red blood cells, 20 mL of a 1.6% NaCl solution was added. Utilizing Percoll in combination with density gradient separation techniques, neutrophils were successfully purified from the bone marrow cells. To identify the purified neutrophils and for downstream experimental purposes, flow cytometry was performed. Additionally, the isolated neutrophils were stained with Shanghai Beyotime Biotechnology Wright-Giemsa kit (C0131, Shanghai, China) and examined under a microscope.

In order to obtain the neutrophil membrane, the neutrophils were destroyed with a low osmotic dissolution buffer containing protease inhibitors for 20 minutes. BeyoZonase broad spectrum nucleases (D7121, Shanghai, China) were added to the solution and treated for 10 minutes. The cells were immersed in liquid nitrogen and 37 ℃ water baths for 5 consecutive cycles of cell destruction. After centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 minutes, the precipitate was discarded. The enriched supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 minutes and 80,000 g for 1.5 hours, respectively. The precipitate was collected and washed three times with PBS mixed with protease inhibitors. Under low temperature conditions, ultrasound was used to obtain dispersed cell membranes.

The method used in the reference literature employs solvothermal synthesis to prepare UiO66 nanoparticles. The specific steps are as follows: 200 mg of benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid (BDC) and dissolve it in 2 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Add the solution to a round-bottom flask and stir for more than 5 minutes. Then, weigh 42 mg of zirconium oxychloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2

The particle size, potential of the samples were detected by Malvern laser particle sizer (NS-90, Malvern, Malvern, UK). Mix 20 mg Dex with 100 mg UiO66, disperse in 20 mL anhydrous ethanol, and stir overnight at room temperature. Then centrifuge the mixture at a speed of 80,000 rpm for 10 minutes, collect the supernatant, and resuspend the precipitate with anhydrous ethanol. Continue centrifugation three times, collecting each supernatant. The morphology of the prepared sample was examined using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (HT7700, Hitachi, Japan). Quantify the content of free Dex in the supernatant using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (HPLC 1260, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and record it as WF. Then, the obtained precipitate was vacuum dried at 120 °C for 24 hours to obtain UiO66-Dex, whose weight was recorded as WNP. Determination of drug loading content and encapsulation efficiency. The encapsulation efficiency and loading content of Dex were calculated as follows:

where WT is the total weight of Dex fed, WF is the weight of non-encapsulated free Dex, and WNP is the weight of nanoparticles.

where WT is the total weight of Dex fed, and WF is the weight of non-encapsulated free Dex.

The neutrophil membrane proteins were determined by a BCA protein assay kit and adjusted to 5 mg/mL. Subsequently, they were mixed with UiO66-Dex (1 mg/mL) in a volume ratio of 1:1. The above mixture was ultrasonically mixed under low-temperature conditions and then passed through an Avant extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.,610000, Alabaster, AL, USA) to coat the neutrophil membrane on the surface of UiO66-Dex. The morphology of the prepared sample was examined using a transmission electron microscope (HT7700, Hitachi, Japan).

To investigate the release of UiO66-Dex@NMP, a dialysis method was employed. Briefly, UiO66-Dex@NMP loaded with 100 µg of Dex was placed into a dialysis bag with a molecular weight cutoff of 3 kDa. The dialysis bag was then immersed in 20 mL of PBS and incubated at 37 °C for various durations while continuously shaking at 100 rpm. At designated time points, 1 mL of the external medium was removed and replaced with the same volume of PBS. The concentration of Dex released into the bulk dialysis medium was determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

RAW264.7 cells were added to 96-well plates at 1

RAW264.7 cells were added into 96-well plates at 1

Firstly, UiO66-Dex@NMP was incubated with a cell membrane green fluorescence staining kit for 10 minutes. After centrifugation to wash away excess fluorescent dye, DiO-labeled UiO66-Dex@NMP was resuspended in physiological saline solution. RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a confocal dish at a concentration of 1

The animals were situated in a controlled environment with a consistent 12-hour light-dark cycle, allowing them unrestricted access to standard food and water. Subsequently, the mice were gently anesthetized with isoflurane before being intranasally administered 35 µL LPS solution (20 mg/mL) to induce a pneumonia model.

First, UiO66-Dex@NMP was incubated with the DiR fluorescence staining kit for 10 minutes. After that, it was centrifuged and washed three times, and then adjusted to an appropriate concentration with physiological saline. Next, the mice with pneumonia were anesthetized and inhaled the commercially available aerosolized UiO66-Dex@NMP labeled with DiR (MB12482, MeiluneBio, Dalian, Liaoning, China). Four hours after the atomized treatment, the distribution of UiO66-Dex@NMP within the body was examined using a small animal in vivo imaging system (IVIS Spectrum, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

The SP model mice were established through induction as described in 2.11. SP model mice were randomly assigned to four groups, each containing five animals: the normal control group, the SP model control group, the Dex treatment group, and the UiO66-Dex@NMP treatment group. Two hours after the SP mouse model was successfully established, the control group solely underwent PBS treatment. Conversely, the Dex treatment group and the UiO66-Dex@NMP treatment group were given atomized administrations of Dex and UiO66-Dex@NMP respectively (Dex dosage 1 mg/kg). Administration of atomized medication was conducted using the Atomization Drug Administration Apparatus for Rats and Mice (KW-DM-YWH, Nanjing Calvin Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), with a treatment duration of 25 minutes. Twenty-four hours post-treatment, blood was collected from the mice, and the sera from each group were subsequently frozen for the purpose of cytokines detection.

The levels of inflammatory cytokines TNF-

Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA), with measurement data following a normal distribution described as mean

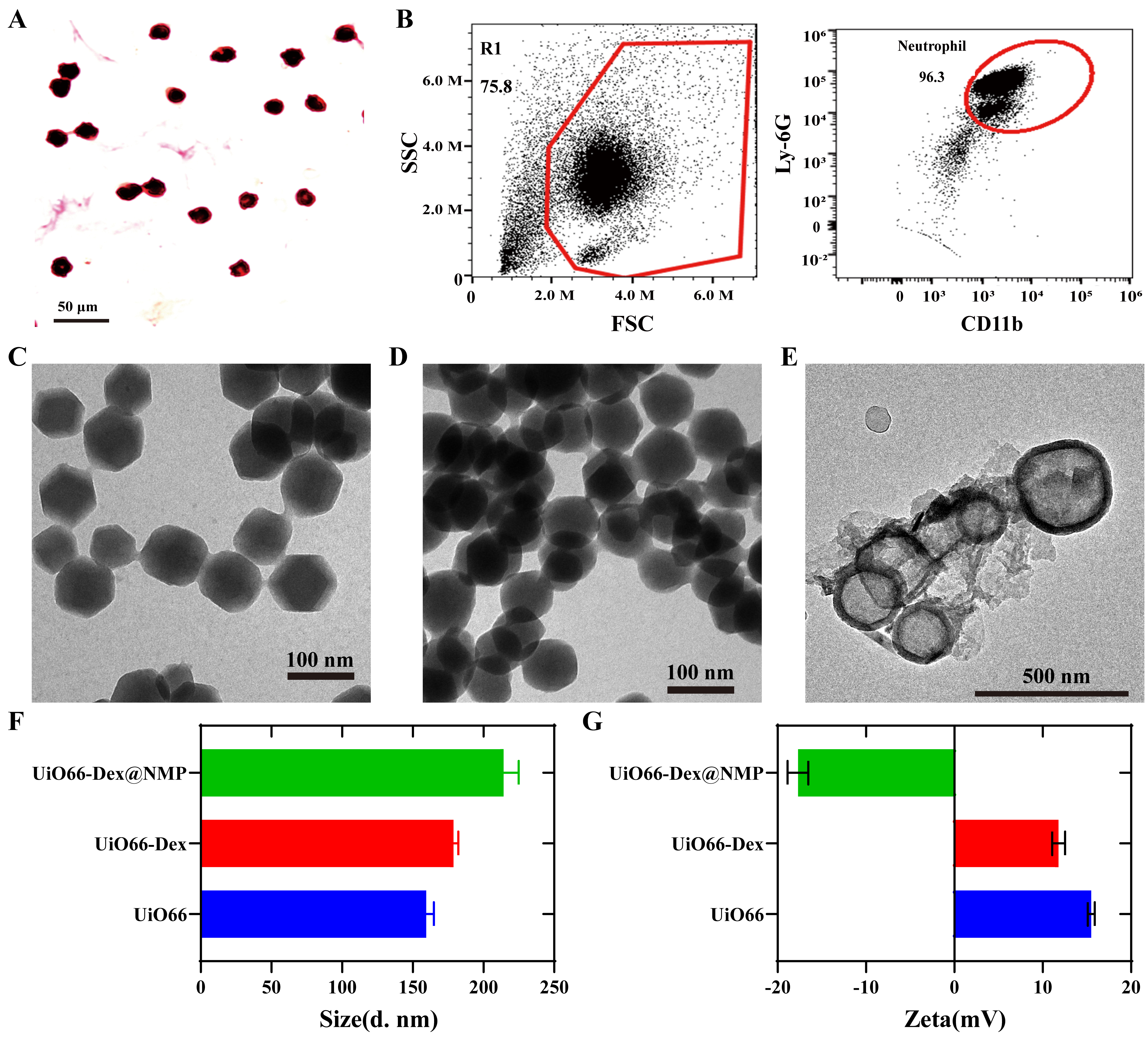

Firstly, neutrophils were separated from bone marrow and peripheral blood. The isolated cells were conducted through Wright-Giemsa staining, revealed a distinct purple-blue lobulated nucleus, which is suggestive of the typical morphology associated with neutrophils, as clearly depicted in Fig. 2A. Neutrophils were preactivated by TNF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Neutrophils separation and characterization of UiO66-Dex@NMP. (A) Wright Giemsa staining of the purified neutrophils. Scale bar = 50 µm. (B) CD11b biomarker analysis of the neutrophil by Flow cytometry. (C) Morphological observation of UiO66 by TEM. Scale bar = 100 µm. (D) Morphological observation of UiO66-Dex by TEM. Scale bar = 100 µm. (E) Morphological observation of UiO66-Dex@NMP by TEM. Scale bar = 500 µm. (F) Particle size analysis of UiO66, UiO66-Dex and UiO66-Dex@NMP. (G) Potentiometric analysis of UiO66, UiO66-Dex and UiO66-Dex@NMP. TEM, transmission electron microscope; FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter.

The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses of UiO66 and UiO66-Dex, depicted in Fig. 2C,D, unveil an average particle size of approximately 100 nm, displaying a distinctive octahedral morphology. The encapsulation of Dex had minimal impact on the particle size and morphology of UiO66-Dex, indicating that Dex is primarily adsorbed within the pores of UiO66-Dex. Fig. 2E showcases the TEM image of UiO66-Dex@NMP, featuring a typical core-shell structure adorned with a cellular membrane on its outer edge. This imagery provides compelling evidence of the successful encapsulation of UiO66-Dex within the cellular membrane, with a mean particle size exceeding 100 nm. Fig. 2F presents the hydrated particle size data for UiO66, UiO66-Dex, and UiO66-Dex@NMP. The presence of a hydration film layer on the surfaces of these nanomaterials results in a measured hydrated particle size that is larger than the size observed through TEM. Furthermore, Fig. 2G illustrates the surface potential analysis of UiO66, UiO66-Dex, and UiO66-Dex@NMP. In aqueous solution, UiO66 and UiO66-Dex exhibit a positive charge, whereas UiO66-Dex@NMP carries a negative charge. This change in electric charge is attributed to the coating with neutrophil membranes.

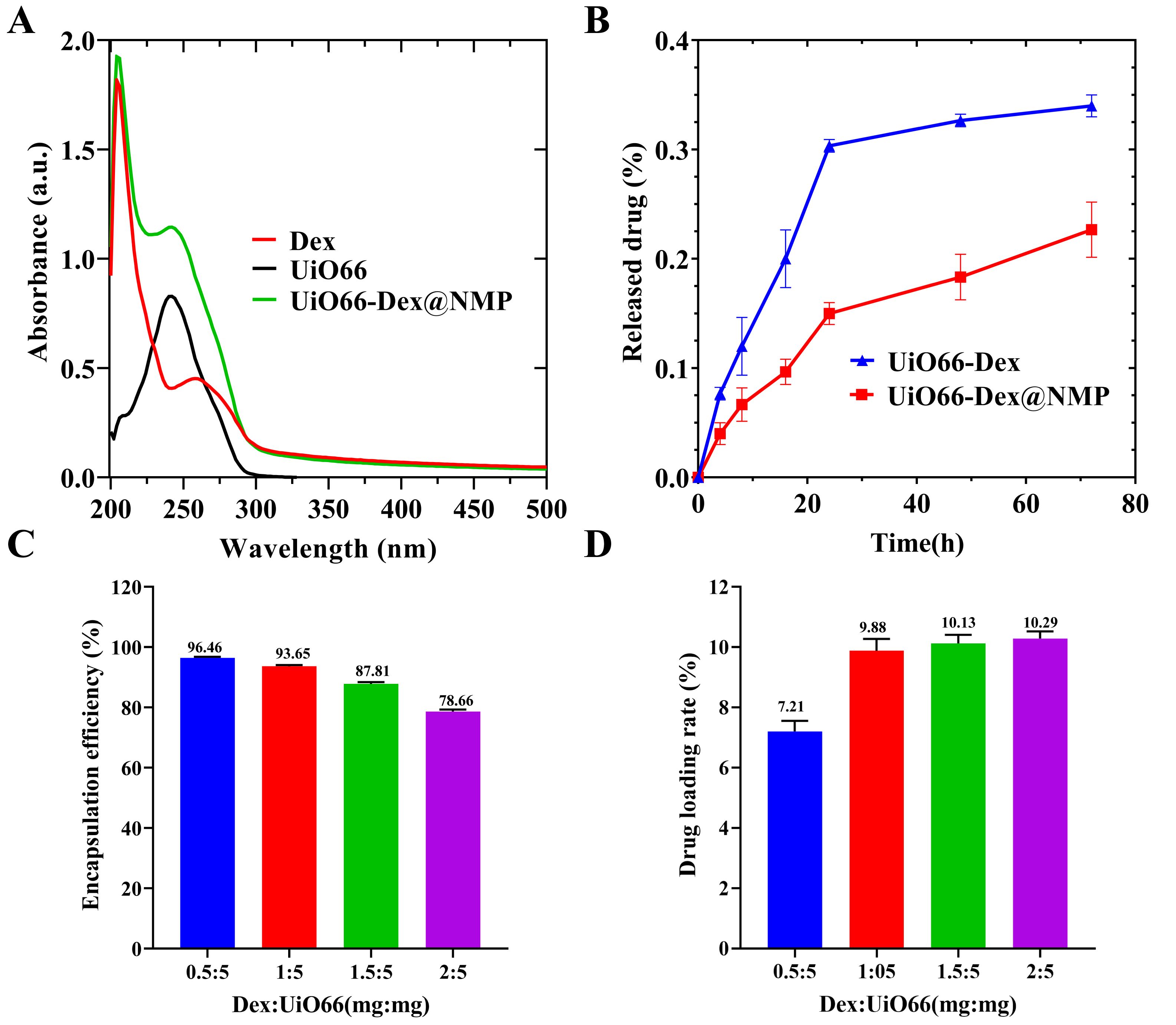

To further characterize the structure of UiO66-Dex@NMP, the ultraviolet absorption was detected. As depicted in Fig. 3A, free Dex (curve in red), UiO66-Dex (curve in black) and UiO66-Dex@NMP (curve in green) all exhibit comparable absorption peaks at identical wavelengths at near 250 nm. Three different absorption curves demonstrate the successful encapsulation of Dex within UiO66-Dex@NMP.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Dex loading and release of UiO66-Dex@NMP. (A) Representative UV-visible absorption peaks of dexamethasone (Dex), UiO66-Dex, and UiO66-Dex@NMP in PBS. (B) In vitro release profile of UiO66-Dex@NMP in PBS over 72 hours. (C) Dex encapsulation rate test. (D) Dex loading test. UV, ultraviolet-visible.

As shown in Fig. 3B, the cumulative release rates of Dex from UiO66-Dex and UiO66-Dex@NMP after 72 hours were 32.67% and 18.33%, respectively. Compared with UiO66-Dex, UiO66-Dex@NMP exhibited lower release rates at every time point, indicating that its release effect is more pronounced and sustained after undergoing biomimetic modification. This characteristic will effectively reduce unnecessary drug leakage and, in turn, lower the risk of side effects potentially caused by Dex. In Fig. 3C,D, the optimum loading rate was achieved when the mass ratio of Dex to UiO66 was 1:5, and the Dex encapsulation rate at UiO66-Dex@NMP was 93.65

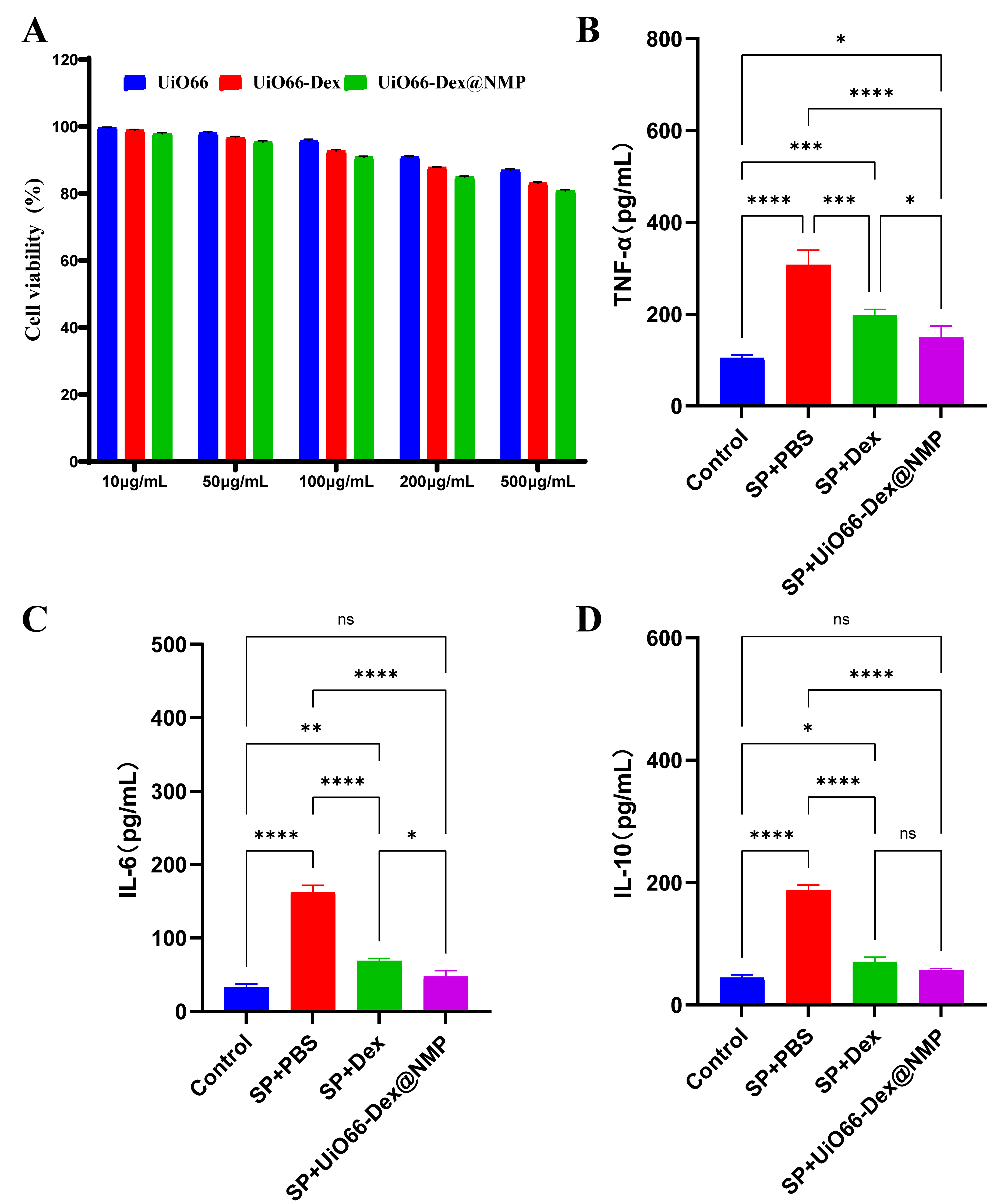

As shown in Fig. 4A, at a concentration of 100 µg/mL or less, UiO66-Dex@NMP showed no significant toxicity to RAW264.7 cells, and the cell survival rates were all over 90%. The levels of inflammatory factors secreted by RAW264.7 cells were shown in Fig. 4B–D, and UiO66-Dex@NMP significantly reduced the TNF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Analysis of cellular toxicity and in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of UiO66-Dex@NMP. (A) RAW264.7 cytotoxicity assay. (B) RAW264.7 levels of the inflammatory factor TNF-

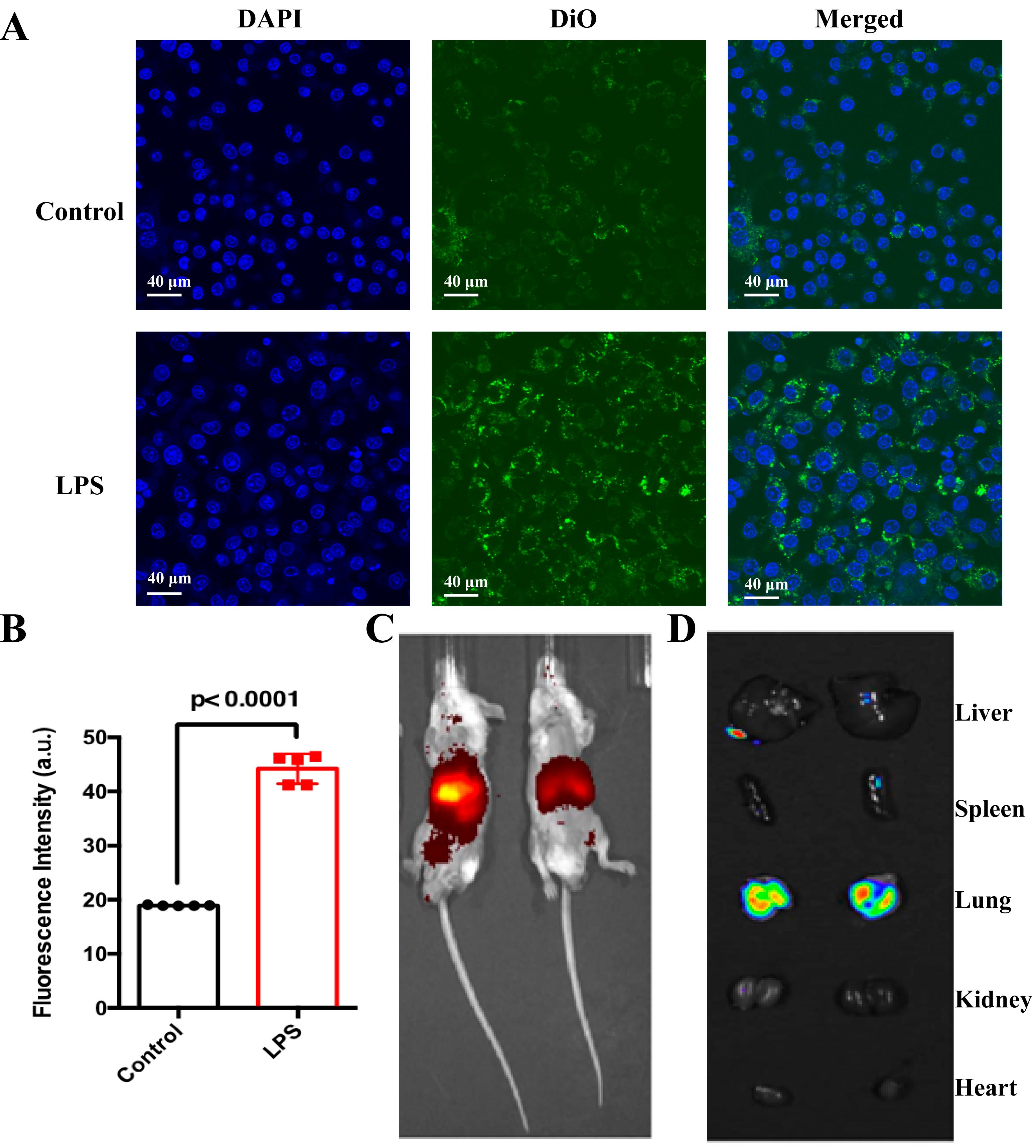

After UiO66-Dex@NMP was labeled with the cell membrane fluorescent dye DiO, it was co-incubated with mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells and then observed under confocal microscopy. Fig. 5A demonstrates that RAW264.7 cells activated by LPS induction exhibited significantly increased green fluorescence compared to inactivated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5B). Consequently, UiO66-Dex@NMP displays a higher targeting efficiency towards activated macrophages in an inflammatory environment, thereby reducing the risk of nonspecific Dex delivery. As shown in Fig. 5C, the in vivo imaging of SP model mice after inhalation of DiR-labeled UiO66-Dex@NMP revealed that the fluorescent signal was primarily concentrated in the lungs. As depicted in Fig. 5D, indicated that apart from the lungs, there was no significant specific enhancement of fluorescent signals in other organs. Inhalation delivery further enhances the accumulation of therapeutic drugs in the lungs, thereby reducing unintended drug diffusion to other parts of the body.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. In vitro and in vivo targeting. (A) Confocal fluorescence imaging of DiO-labeled NMPs after incubation with activated macrophages (blue, nuclei; green, UiO66-Dex@NMP). Scale bar = 40 µm. (B) Fluorescence quantification of UiO66-Dex@NMP per unit area on macrophages, p

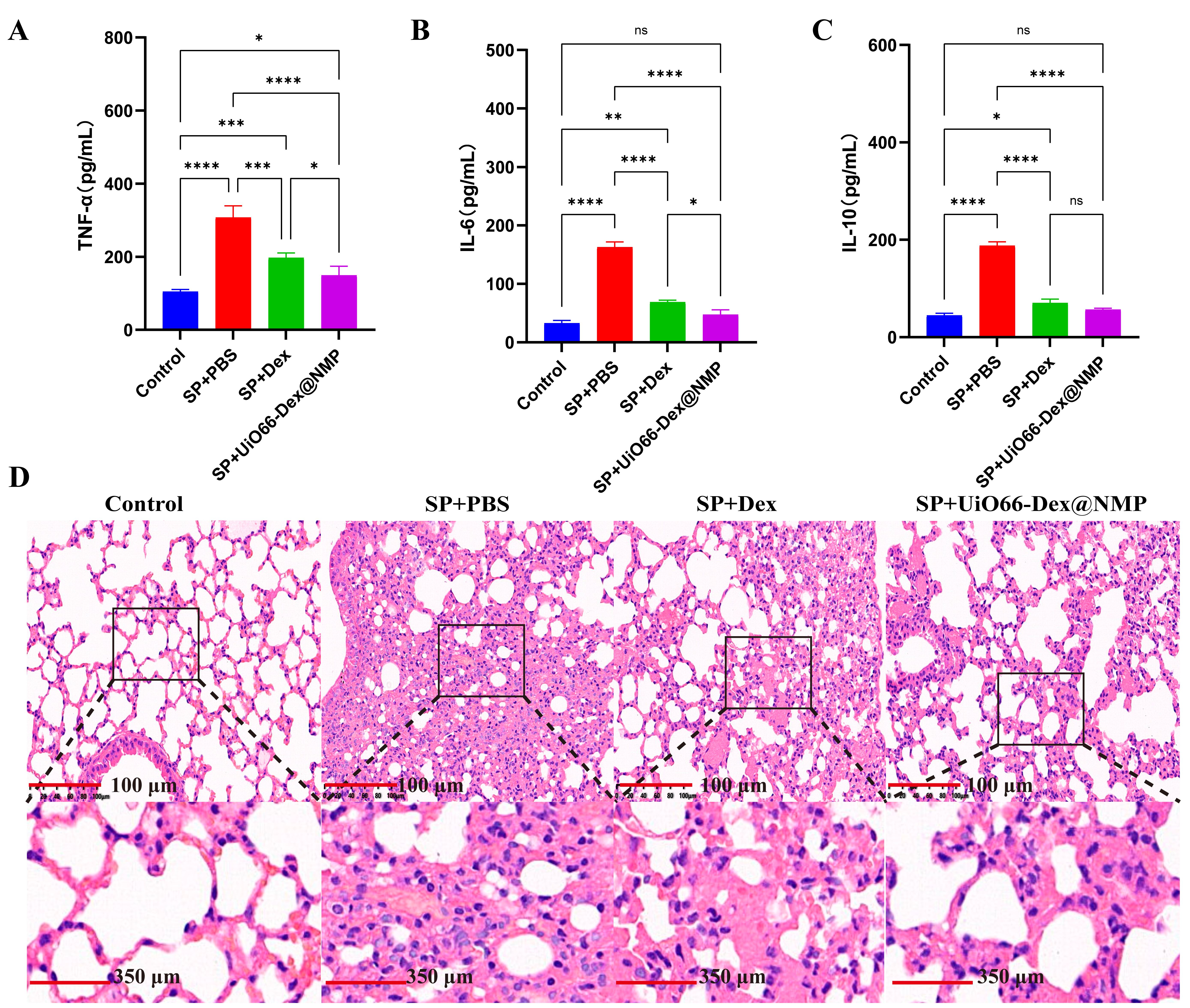

Fig. 6A–C shows the serum cytokine levels in normal mice and SP model mice after receiving corresponding treatments. Compared to the normal control group, mice in the SP+PBS group exhibited significantly elevated serum levels of TNF-

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Anti-severe pneumonia Therapy. The cytokines level after indicated treatments: (A) TNF-

The histological sections in Fig. 6D, revealed various degrees of pathological changes in the lung tissue of the SP model group. These included alveolar mice, collapse of alveolar walls, infiltration of inflammatory cells, dilation and congestion of capillaries, among other changes. In contrast, the lung tissue of the normal control group did not exhibit these changes, indicating the successful establishment of the SP model. When compared to the model group, both the Dex and UiO66-Dex@NMP inhalation treatment groups showed a reduction in the severity of SP-related pathological changes in the lung tissue. Furthermore, compared to inhaled Dex treatment, inhaled UiO66-Dex@NMP treatment further mitigated the pathological damage to the lungs caused by SP. Therefore, inhaled UiO66-Dex@NMP treatment demonstrated the most favorable therapeutic effect in SP, with significant improvements in both inflammatory cytokine levels and pathological lung injury.

UiO66-Dex@NMP exhibits remarkable targeting capabilities both in laboratory settings and in living organisms. To further investigate its potential, we conducted inhalation therapy studies using a mouse model of LPS-induced pneumonia. When compared to both the control group and dexamethasone sodium phosphate administered via inhalation, UiO66-Dex@NMP significantly decreased the degree of lung inflammation. Histopathological assessments confirmed that UiO66-Dex@NMP mitigated lung tissue damage. Consequently, UiO66-Dex@NMP emerges as a novel and safe carrier for inhaled dexamethasone delivery, providing significant insights into the clinical management of respiratory diseases, including severe pneumonia (SP). By harnessing the advantages of nano-formulation, atomized administration, and cell membrane-targeted delivery, this dexamethasone nanomedicine aims to reduce the overall dosage and systemic exposure of dexamethasone, thereby minimizing adverse side effects and enhancing patients’ quality of life.

The data and materials used in the current study are all available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

KW and CX designed the research study. YY, HZ, and LY performed the research. YY, HZ, and LY analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. YY edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal experiments conducted in this study complied with the relevant requirements of Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Third Military Medical University (Approval No. AMUWEC20210417). The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the staff at the Laboratory Animal Center of the Third Military Medical University for their invaluable assistance in conducting the animal experiments.

This study was funded by the Cisen Pharmaceutical Public COVID-19 Scientific Research Fund (WPV01-CP-23).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Despite they received sponsorship from Cisen Pharmaceutical, the judgments in data interpretation and writing were not influenced by this relationship.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.