1 Department of Stomatology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, 350001 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

2 Department of Stomatology, The Affiliated Heping Hospital of Changzhi Medical College, 046000 Changzhi, Shanxi, China

3 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of The First Affiliated Hospital, 350005 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

Abstract

In this study, we prepared a porous gradient scaffold with hydroxyapatite microtubules (HAMT) and chitosan (CHS) and investigated osteogenesis induced by these scaffolds.

The arrangement of wax balls in the mold can control the size and distribution of the pores of the scaffold, and form an interconnected gradient pore structure. The scaffolds were systematically evaluated in vitro and in vivo for biocompatibility, biological activity, and regulatory mechanisms.

The porosity of the four scaffolds was more than 80%. The 50% and 70% HAMT-CHS scaffolds formed an excellent gradient pore structure, with interconnected pores. Furthermore, the 70% HAMT-CHS scaffold showed better anti-compressive deformation ability. In vitro experiments indicated that the scaffolds had good biocompatibility, promoted the expression of osteogenesis-related genes and proteins, and activated the oxidative phosphorylation pathway to promote bone regeneration. Eight weeks after implanting the HAMT-CHS scaffold in rat skull defects, new bone formation was observed in vivo by micro-computed tomographic (CT) staining. The obtained data were statistically analyzed, and the p-value < 0.05 was statistically significant.

HAMT-CHS scaffolds can accelerate osteogenesis in bone defects, potentially through the activation of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. These results highlight the potential therapeutic application of HAMT-CHS scaffolds.

Keywords

- osteogenesis

- hydroxyapatite

- chitosan

- pore scaffold

- oxidative phosphorylation

Bone defects area common orthopedic disease encountered in the clinic. They can cause major damage and require long treatment cycles, thus imposing a heavy medical burden on society [1]. The focus of many researchers has therefore been to identify materials that act as the ideal substitute for bone tissue. Autogenous bone transplantation is still unable to treat diseases related to bone defects. In recent years, bone tissue engineering has been promising approach for production of the best bone tissue replacement materials in recent years [2]. In addition to hydroxyapatite (HAP), other novel materials such as graphene, electrospinning, hydrogels and chitin, have been reported. HAP has the molecular formula Ca10(PO4)6OH2, a theoretical Ca/P molar ratio of 1.67, and a hexagonal crystal system. The mineral in bone is carbonate apatite, which is calcium-poor (Ca/P molar ratio

Advances in technology, have allowed changes in the microscopic shape of materials, including the production of spherical, rod, and tube shapes as well as the production of nanoscale materials. A review of the literature reveals; that only a few studies [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] have been published on tubular materials, mainly on carbon nanotubes and hydroxyapatite microtubules (HAMT). In 1991, Ijima [10] reported on a hollow tube with a nanoscale diameter that was made of curled graphite sheets at a specific spiral angle. The advantages of carbon nanotubes are: (1) They enhance the mechanical properties of tissue engineering materials; (2) They provide or enhance electrical conductivity, thus regulating the cell growth rate and inducing tissue arrangement; (3) They have a high specific surface area, which is conducive to protein adsorption and adhesive cell growth; (4) The structure and appropriate porosity of nanonetworks is conducive to the exchange of materials between cells and the extracellular matrix [10].

Carbon nanotube tissue engineering materials have also become a research hotspot in recent years. Ma et al. [4] synthesized a poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) scaffold with carbon nanotube coating. The original porosity and permeability of the scaffold remained unchanged, but the specific surface area was increased by the coating [4]. The content of carbon nanotubes in the composite material must be controlled, since a content can form an aggregation structure [11]. Kolos and Ruys [5, 6] developed a novel method for the preparation of HAMT using biomimetic coating. Cotton wool was bionic coated by phosphorylation pretreatment and a Ca(OH)2 soaking solution in 5.0 simulated body fluid. The HAMT are formed by sintering and the cotton matrix is then burned [5, 6]. Yuan et al. [12] used sol-gel auto-combustion method to prepare ordered HAP nanotubes in porous anodic alumina templates. Hui et al. [7] prepared fluoro-substituted HAP nanotubes using a hydrothermal method, but the product was in pure due to the presence of fluoride ions. Chandanshive et al. [8] synthesized HAP nanotubes with the template method, but the products were polycrystalline and had poor mechanical properties. Ma et al. [13] added CaCl2 and NaH2PO4 into the solvent mix of water and N,N-Dimethylformamide for 24 h at 160 °C to prepare HAMT using a one-step method with a relatively simple flow. Zhang et al. [9] successfully synthesized HAMT using CaCl2, NaOH, (NaPO3)6, oleic acid, deionized water and ethanol as reaction systems. These HAMT had good biocompatibility, were monodisperse and monocrystalline and had ultra-long life. A tubular structure has good drug loading and slow release properties, and has broad application in the field of medicine and biology [9].

In recent years, nano-HAP has been widely used in biological materials [14]. However, it is difficult to for nano-HAP to meet the requirements as a scaffold for bone tissue engineering due to its low mechanical strength and low toughness [15]. The HAMT prepared in the present study is mechanically stronger than nano-HAP, simple to produce, cost-effective, and also has good biocompatibility [16, 17, 18]. We conducted a literature search of papers published over the past 15 years with the key word “hydroxyapatite”, “hydroxyapatite microtubules”, “chitosan” and “bone tissue engineering”. Researchers have paid attention to the material characteristics, as well as to its structure. Porous scaffolds have proven to be a reasonable design, and the pore size, porosity, and arrangement can affect osteogenesis. In the current study, we synthesized a gradient pore scaffold using HAMT and chitosan (CHS) as raw materials, with wax spheres used as the pore forming material. The characterization, biocompatibility, and biological activity of the materials were systematically evaluated. The scaffolds have excellent drug loading and controlled-release ability. Moreover, the design of the gradient pore is similar to the structure of natural bone, and is expected to have good osteogenic effects and therapeutic function in bone defects.

The preparation method described by Zhang et al. [16], was employed here. Ultrapure water (Direct-pure UPU, Shanghai, China) (4.5 mL), anhydrous ethanol (China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation, Beijing, China) (8.5 mL), and oleic acid (China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation, Beijing, China) (7 mL) were stirred for 5 min at room temperature. Next, 10 mL each of CaCl2 (Xilong Chemical, Guangdong, China) (200 mM), NaOH (Xilong Chemical, Guangdong, China) (1.65 M) and (NaPO3)6 (Xilong Chemical, Guangdong, China) (31.45 mM) solutions were added drop by drop to the solution prepared in the first step. A magnetic stirrer provided continuous stirring throughout the procedure. This suspension was then transferred to a reactor and placed in a constant temperature drying oven (JTONE/101-1AB, Shanghai, China) preheated to 180 °C for 25 h. Afterward, the reactor was cooled to room temperature, the final product was washed with anhydrous ethanol and ultra-pure water, centrifuged and dried for use.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (Xilong Chemical, Guangdong, China) particles (4 g) were added to pure water (200 mL) to prepare a 2 wt% PVA suspension. A heated and melted paraffin (China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation, Beijing, China) solution (20 mL) was added to the PVA suspension with continuous stirring for 10 minutes. The paraffin-PVA solution was then poured into cold water to terminate the reaction, and the wax balls with a diameter of 500–800 µm and 800–1430 µm were screened.

The mold was a cylindrical shape with a base diameter of 8 mm and a height of 5 mm. Wax balls (800–1430 µm) were arranged 4 mm around the mold, and 500–800 µm wax balls were arranged in the central 4 mm. Heating at a constant temperature of 37 °C for 30 min can soften the wax balls and induce connections with each other. CHS powder (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) was dissolved in a 1% acetic acid solution (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) to obtain a CHS solution with a concentration of 2 wt%. In the final step, HAMT was added to give as HAMT:CHS mass ratio of 7:3 and stirred continuously at room temperature for 6 h. The mixed slurry was injected into the mold, and freeze-dried (Scientz-12N, Ningbo, China) to obtain a complete scaffold. The scaffold was immersed in n-hexane (Xilong Chemical, Guangdong, China) solution and placed in a water bath at 55 °C. The solution was changed every 1 h, until the wax balls inside the scaffold could be removed. Repeated rinsing with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) removed any residual n-hexane. The 70% HAMT-CHS scaffolds were freeze-dried after cleaning and disinfection. The HAMT:CHS ratio was adjusted to 5:5/9:1. The 50% HAMT-CHS and 90% HAMT-CHS scaffolds, as well as the CHS scaffolds without HAMT were prepared by the same method as the control group.

Scaffold morphology was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Merlin Compact, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet iS20, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) detects the sent composition in the wave range of 400–4000 cm-1. An X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku Smartlab 3KW, Tokyo, Japan) was used to determine the composition of the material and the structure of the atoms or molecules inside the material. The scanning angle was 10°–80° and the scanning speed was 2°/min. The porosity of the support was analyzed by a high-performance automatic mercury imposer (Micromeritics AutoPore IV 9520, Atlanta, GA, USA) as described previously [19]. A universal testing machine (Shimadzu AGS-X-50N, Kyoto, Japan) was used to evaluate the mechanical properties of the support and to obtain mechanical indexes such as the compressive strength and elastic modulus. The size of the test sample was

The scaffolds and phenytoin sodium (MCE, Rockville, NJ, USA) PBS solution (100 mg/L) were placed in a shaker at 37 °C for 24 h at 140 r/min. Immediately after drug loading, the freeze-drying processing was carried out for 24 h. The drug-carrying scaffold was added to 10 mL of PBS, and 3 mL of the release solution was removed at a preset time, and an equal volume of PBS was added. Each set of scaffolds contained four samples and were stored in a 37 °C incubator and shaken at 140 r/min for 24 h before each preset time point. Subsequently, the absorbance of the release medium at 258 nm was measured by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (MAPADA/UV-1200, Shanghai, China).

Extract liquor was prepared according to the criteria ISO10993-5:2009 and ISO10993-12:2012. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were inoculated onto pore plates and cultured for 24 h. The culture medium was then replaced with extract from the corresponding group, and the culture continued for 48 h before staining. The residual serum was rinsed with PBS, diluted 1000 times with Calcein-AM/PI stock solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), then added into the well, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Absorbing the staining solution in the hole, the cells were rinsed with PBS several times and observed under the fluorescence of 488 nm wavelength. The cells were gently rinsed with PBS twice, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, the fixed solution was sucked away, washed with PBS twice, and each well was stained with Phalloidin (Abclonal, Wuhan, China) (1:200 dilution) 250 µL for 30 min. After absorbing Phalloidin solution, rinsing with PBS twice, adding 250 µL 2-(4-Amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride (DAPI) solution (Servicebio, Hubei, China) to each well for 3 min, absorbing the staining solution, washing with PBS twice, fluorescent staining was performed. Result in the observation of cells by fluorescence microscope (IX73, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Rat BMSCs were provided by the Shanghai Fusheng Company. All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and free of mycoplasma (Minerva-Biolabs Mycoplasma Detection Kit, Berlin, Germany). Primary rat BMSCs were cultured for the 3, 4, or 5 passages for subsequent experiments.

Sterilized scaffolds were placed into a 96-well plate, and 100 µL of medium was added to each well and to soaked for 24 h. The third generation of rat BMSCs were seeded onto the scaffold at 2

Rat BMSCs was seeded into 6-well plates for 24 h. The culture medium was then removed with the corresponding extraction solution added. After 7 days, the medium was removed and the cells rinsed with PBS. ALP staining solution (300 µL) (Biosharp, Beijing, China) was then added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by three rinsed with PBS before evaluation.

After culturing cells for 14 days, PureLink RNA MiniKit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to isolate total RNA as recommended by the manufacturer. A NanoDrop-1000 instrument (Thermo Scientific NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c) was used to assess the concentration and quality of RNA. Complementary DNA was obtained and replicated by using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit and the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (StepOnePlus, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. The expression of genes was determined by TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the control gene, and each set of scaffolds contained four samples. The primer (purchased from Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) is detailed in Table 1.

| Gene | Primer |

| GAPDH | 5′-AAGTTCAACGGCACAGTCAAGG-3′ |

| 5′-GACATACTCAGCACCAGCATCAC-3′ | |

| ALP | 5′-ACTGATGTGGAATATGAACTGGATGAG-3′ |

| 5′-ATAGTGGGAGTGCTTGTGTCTAGG-3′ | |

| BMP | 5′-GAACAGGGCTTCCACCGTATAAAC-3′ |

| 5′-TGTCCAGTAGTCGTGTGATGAGG-3′ | |

| OCN | 5′-CTCTGAGTCTGACAAAGCCTTCATG-3′ |

| 5′-CTCCAAGTCCATTGTTGAGGTAGC-3′ | |

| OPN | 5′-GACGACGATGACGACGGAGAC-3′ |

| 5′-TGTGTGCTGGCAGTGAAGGAC-3′ | |

| OSX | 5′-GCTCTTCTGACTGCCTGCCTAG-3′ |

| 5′-TGGTGAGATGCCTGCATGGATG-3′ | |

| RUNX2 | 5′-ACTTCGTCAGCGTCCTATCAGTTC3′ |

| 5′-CCATCAGCGTCAACACCATCATTC-3′ |

The cells were cultured with scaffolds for 14 days and then lysed with radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Isolated proteins were separated and then electro-transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes with 0.45 µm pore size. The PVDF membranes were blocked by incubation with 5% BSA (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) at room temperature for 2 h, then incubated with primary antibodies against osteopontin (OPN, dilution 1:100, Abcam ID: ab307994, Cambridge, UK), Osterix (OSX, dilution 1:100, Abcam ID: ab209484, Cambridge, UK), runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2, dilution 1:100, Abcam ID: ab76956, Cambridge, UK), and GAPDH (dilution 1:500, Abclonal ID: AC054, Wuhan, China). After overnight incubation at 4 °C, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a second antibody (horseradish peroxidase (HRP) Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), dilution 1:500, Abclonal ID: AS003, Wuhan, China; Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) HRP, dilution 1:500, Affbiotech ID: S0001, Jiangsu, China) labeled with horseradish peroxidase. An ECL staining kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) then was used to detect the protein bands. Gel-pro analyzer 4.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) analyzed the gray value of each strip, with at least three biological replicates per protein. GraphPad Prism 9.1.2 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for significance analysis.

The cells were inoculated on the scaffold, cultured for 14 days, and the RNA was then extracted by repeatedly washing the scaffold with Trizol. An Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to quantify and identify extracted RNA samples to accurately determine the RNA integrity. The messenger RNA (mRNA) of qualified samples was amplified by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and purified to obtain the final library. In the second step, initial quantification was performed using a Qubit2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), followed by library insertion size measurements using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. To ensure the quality of the library, the effective concentration (

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technology helps to identify activated pathways and differentially expressed genes. The protein expression level of key genes and the level of specific oxidases were evaluated to determine which pathways were activated. The key genes are Fe-S protein 5 (NDUFS5, dilution 1:1000, GeneTex ID: GTX101829, San Antonio, TX, USA) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 6c (COX6C, dilution 1:500, Zenbio ID: R24043, Chengdu, China). Oxidative phosphorylation pathway inhibitor carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, MCE, NJ, USA). The CCK-8 assay was used to determine the 50% inhibitory concentration of FCCP. The culture medium diluted FCCP to various concentrations and co-cultured with the cells for 3 days. The 50% inhibitory concentration was determined using the CCK-8 assay, and the optimal FCCP concentration for pathway blockade was determined based on the results. The studied pathway was inhibited by FCCP and Western blot experiments were performed to verify whether key genes were down-regulated.

SD male rats (10 rats, 8 weeks old, approximately 270 g, purchased from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) underwent general anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection of 1% tribromoethanol (Aladdin, China) at 0.02 mL/g body weight. A 3 cm incision was made designed in the middle of the skull to separate the subcutaneous tissue from the bone surface, and an 8 mm trephine was then used to remove part of the skull, taking care not to damage the dura. The scaffolds were placed into the defect and the wound was sutured. After 2 months of conventional environment, the rats were euthanized by excessive carbon dioxide inhalation, and the skull defect was examined by Micro-CT (Skyscan1276, Bruker, Saarbrucken, Germany). The following variables were measured: tissue volume (TV), bone volume (BV), bone surface (BS), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), and trabecular number (Tb.N), bone volume fraction (BV/TV), bone surface fraction (BS/BV), bone surface area density (BS/TV). The study was carried out in accordance with the revised Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 in the UK and Directive 2010/63/EU in Europe and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ethics Committee of the Changzhi Medical College (Protocol No. DW2022082).

Graphpad Prism 9.1.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to compare the results of the HAMT-CHS group and the blank group by T-test, with a p-value of

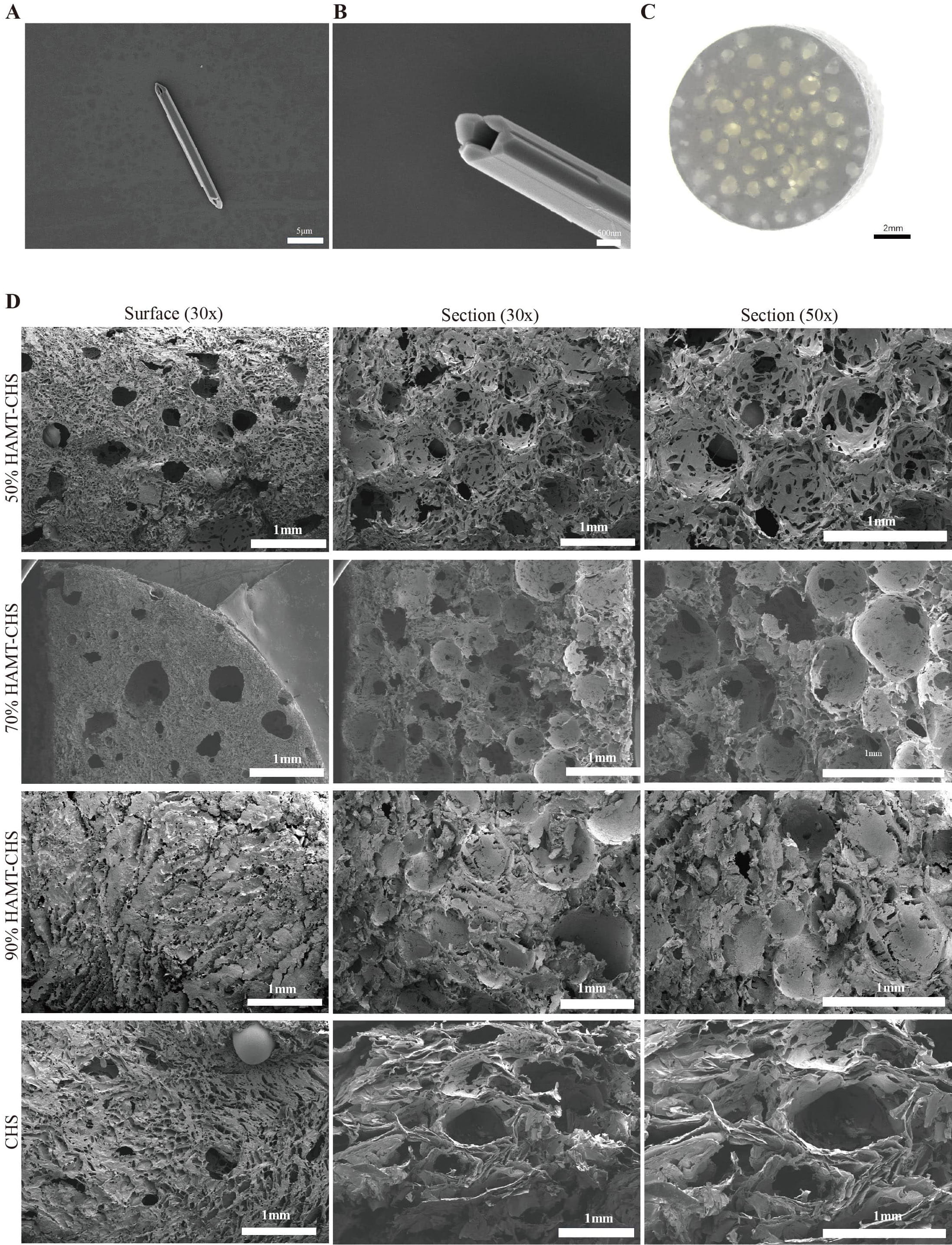

Tubular structures of the prepared HAP powder were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) under two resolutions (Fig. 1A,B). With a stereomicroscope, pores of varying size were found on the outer surface of the gradient pore scaffold (Fig. 1C). The four scaffold groups were observed to have a rough surface under SEM, scaffolds prepared solely by CHS did not form a good pore structure on the surface and in cross section (Fig. 1D). However, pore structures on the surface and in cross section were observed for the of 50% HAMT-CHS and 70% HAMT-CHS scaffolds, with cracks penetrating between the pores. The 90% HAMT-CHS scaffold did not show uniform pore structure, either on the surface or in cross section (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Characterization of HAMT-CHS scaffolds. (A) The tubular structures of hydroxyapatite microtubule (Scale bar: 5 µm). (B) The same as (A) but for 2

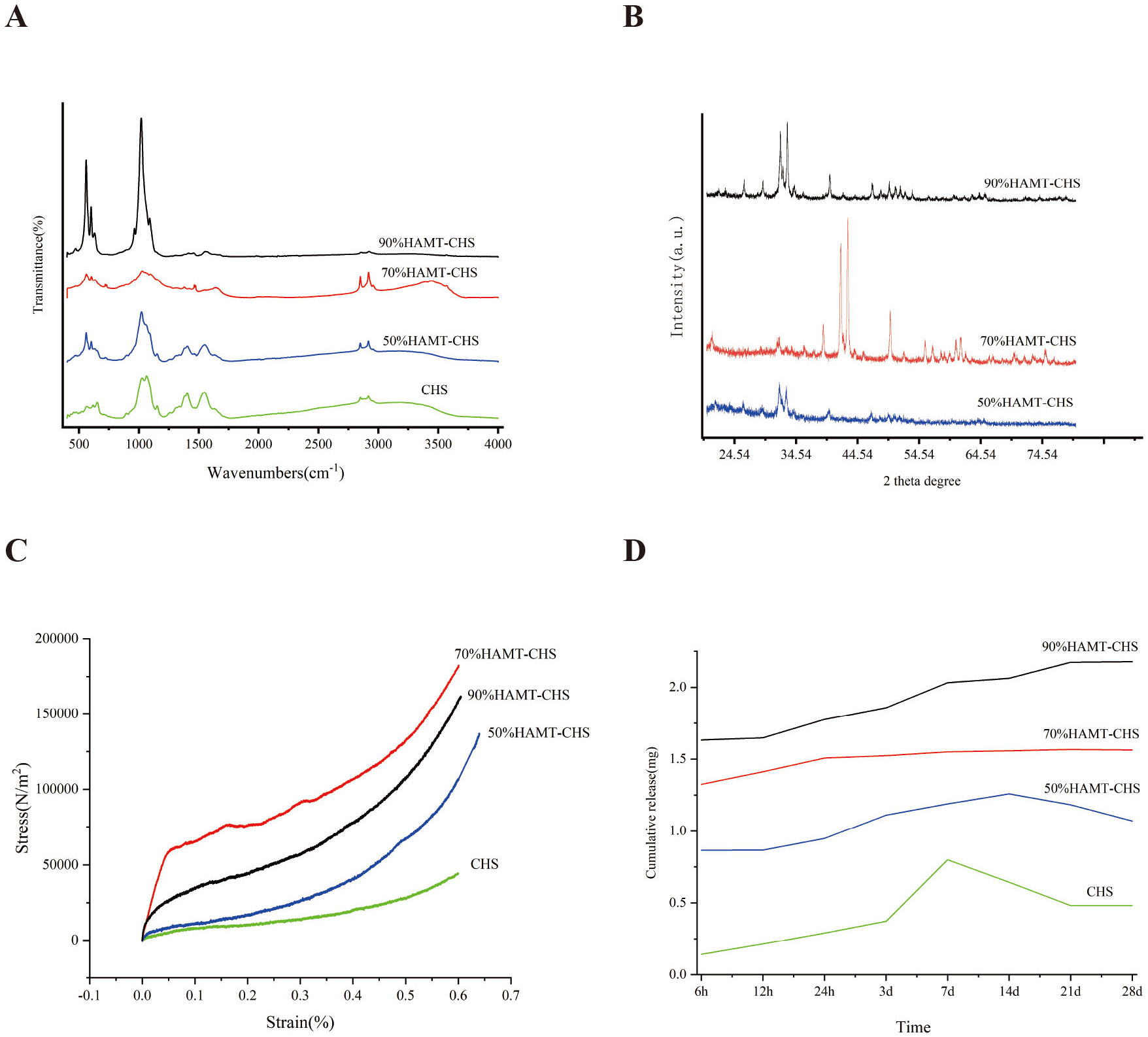

The position of the peak of each functional group in the FTIR spectra is basically consistent with that of chitosan and hydroxyapatite (Fig. 2A). X-ray diffraction results also showed obvious differences between the three scaffolds (Fig. 2B). The hydroxyapatite materials in the scaffolds were crystallized into standard hydroxyapatite structures, and the diffraction peaks and intensities were consistent with those of standard hydroxyapatite cards. Chitosan is amorphous and hence, no significant peak form was observed. The elastic modulus results for support were as follow: CHS (44.383

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Physical and drug loading performance of HAMT-CHS scaffolds. (A) The position of the peak of each functional group in the FTIR spectra. (B) The X-ray diffraction results of each group of the scaffolds. (C) Stress-Strain curve. Elastic modulus of the support was CHS (44.383

Plotting the 28-day cumulative release curve showed that the 90% HAMT-CHS scaffold had the highest drug loading capacity, and the CHS scaffold the lowest (Fig. 2D). This result indicates the HAMT material has good drug loading capacity, and that the higher the proportion of HAMT in the scaffold, the greater the drug loading capacity. The CHS group and the 50% HAMT-CHS group showed no significant difference in drug release at 7 and 14 days. The drug concentration was continuously diluted after new PBS solution was added to the samples, and hence the curve showed a downward trend (Fig. 2D). Sustained drug release was observed with the 90% HAMT-CHS and 70% HAMT-CHS scaffolds in the first 28 days, with more stable in the 70% HAMT-CHS group (Fig. 2D). The porosity of the four scaffold groups was: CHS (85.3%), 50% HAMT-CHS (84.1%), 70% HAMT-CHS (88.8%), and 90% HAMT-CHS (80%).

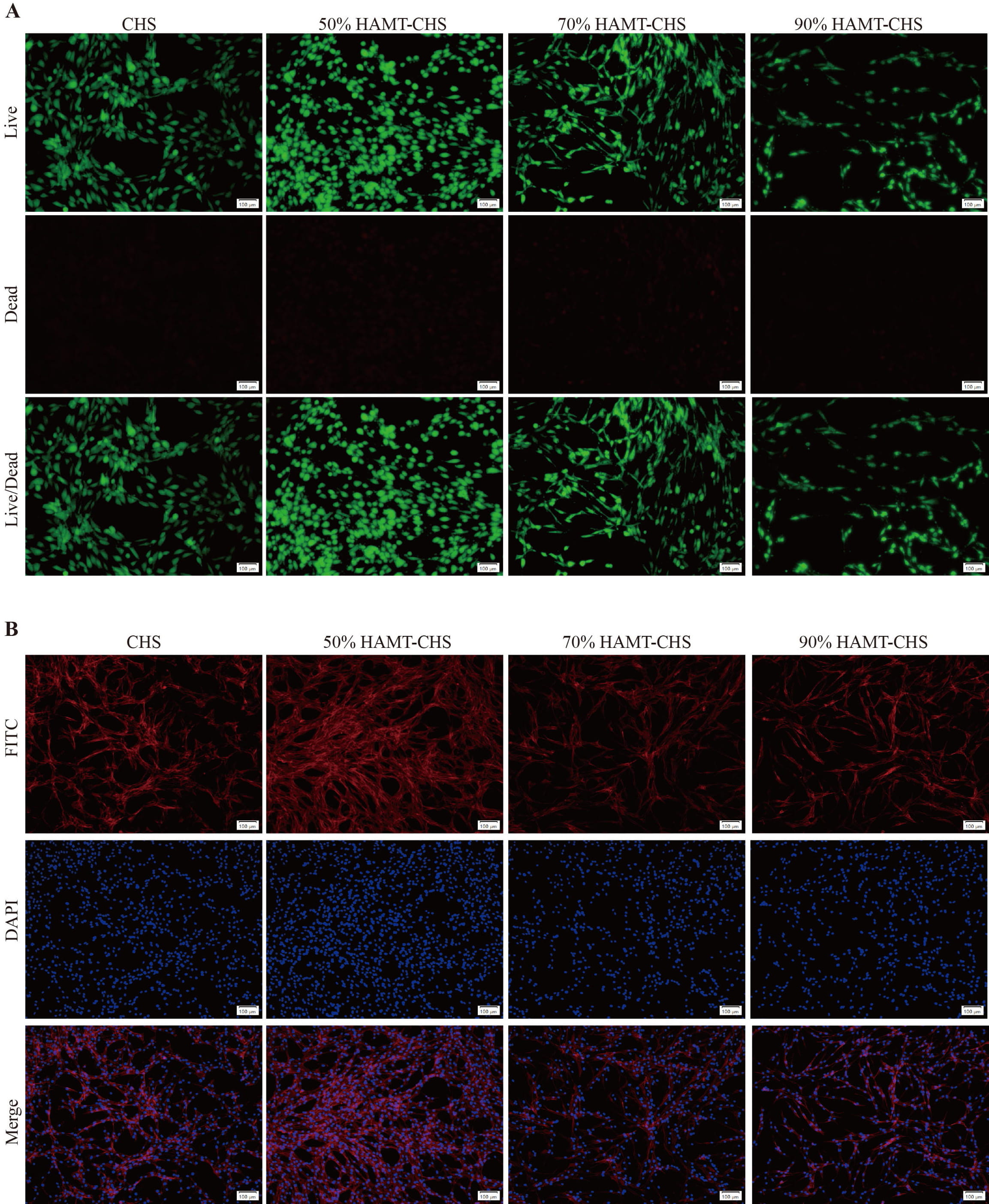

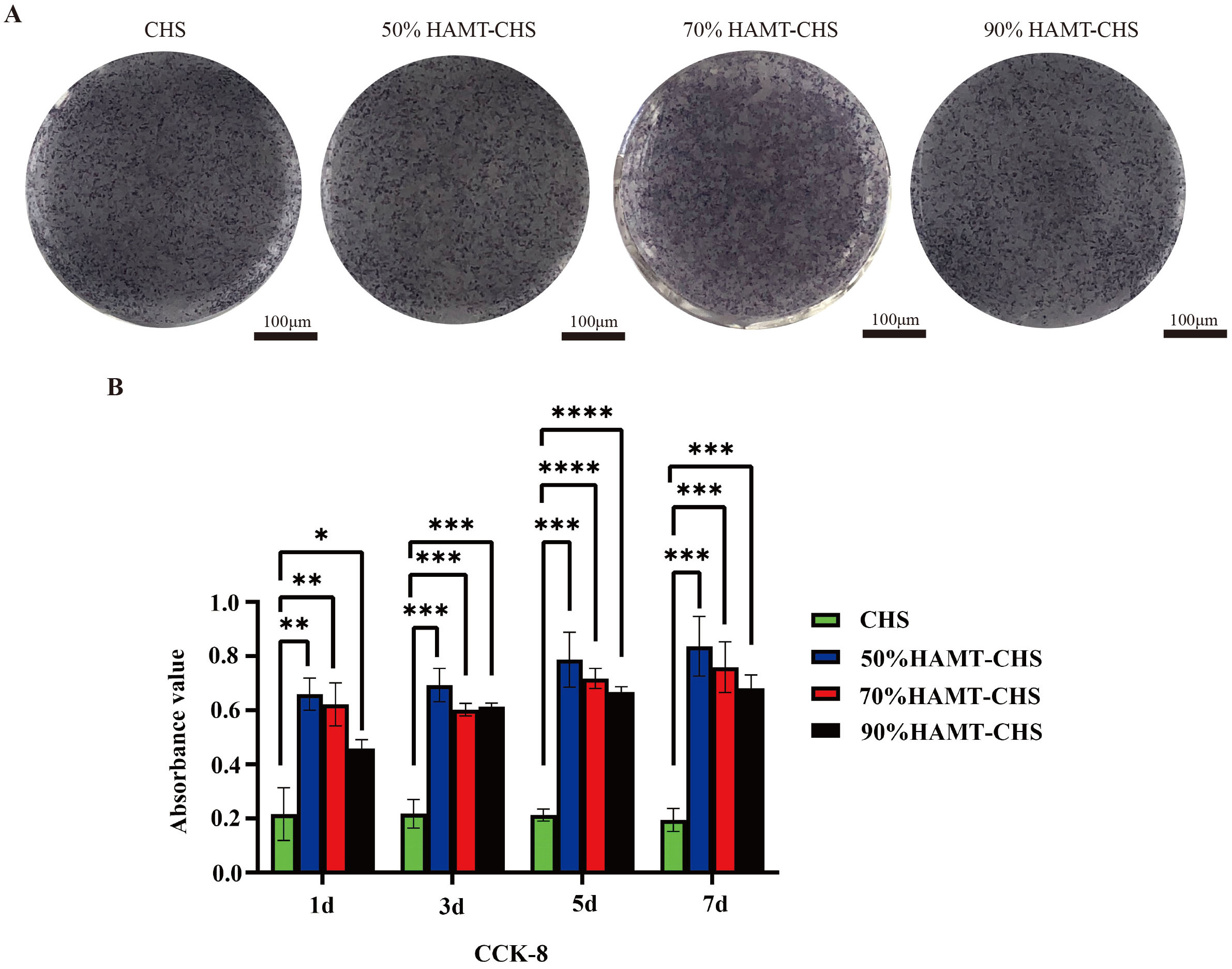

Co-culture experiments with BMSCs were performed to assess the biocompatibility of HAMT-CHS scaffolds. Live and Dead Cell Double staining kit (Calcein-AM/PI) and fluorescence staining showed good cell growth in each group, with very few dead cells (Fig. 3A,B). Furthermore, no obvious difference in ALP staining was observed between the four scaffold groups (Fig. 4A). The results of the CCK-8 experiment also showed that no cytotoxicity after co-culture of the scaffolds and BMSCs in any of the four groups. Moreover, the cell proliferation rate was greatly increased, especially in the 50% and 70% HAMT-CHS scaffold groups, but was lower in the CHS group (p-value

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Biocompatibility test. Calcein-AM/PI Staining (A) (Scale bar: 100 µm), and Fluorescence staining (B) (Scale bar: 100 µm) for BMSCs that were co-cultured with CHS and HAMT-CHS scaffold extracts (Sample size n = 4). BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; DAPI, 2-(4-Amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; Calcein-AM/PI, Live and Dead Cell Double staining kit.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Biocompatibility of the HAMT-CHS scaffolds co-cultured with BMSCs. (A) The ALP staining result of BMSCs that were co-cultured with scaffold extracts for 7 days (Scale bar: 100 µm). (B) The CCK-8 result of BMSCs that were co-cultured with scaffold extracts for 7 days. “*”, “**”, “***”, “****” represent p

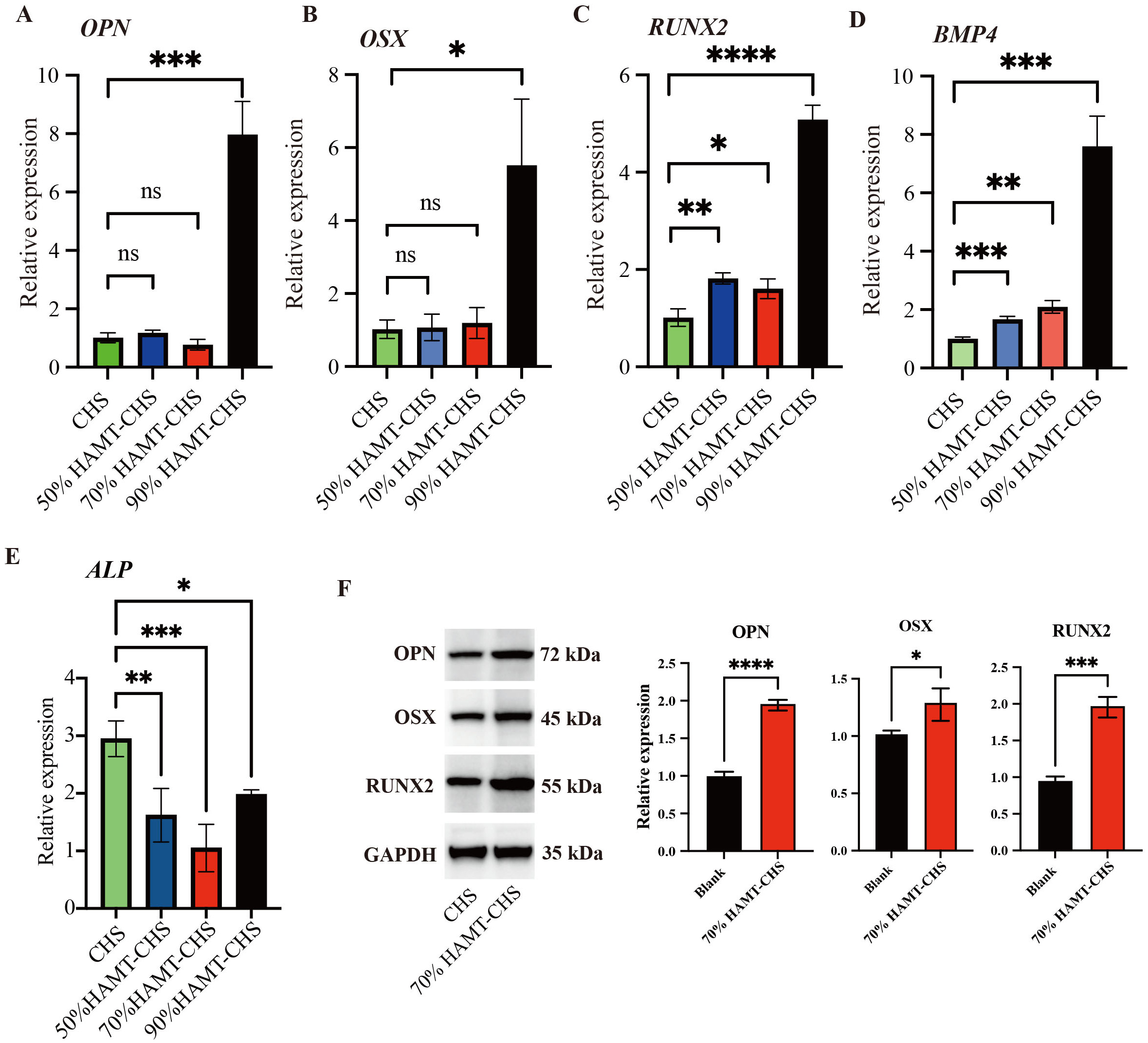

To study how HAMT-CHS scaffolds modulate the cellular phenotype of BMSCs, we examined the expression pattern of several essential genes in osteogenesis. Expression level of OPN, RUNX2, BPM4, and OSX were significantly higher in 90% HAMT-CHS group than in the other groups (p-value

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. RT-PCR and WB results for selected genes. (A–E) RT-PCR results of gene OPN (A), OSX (B), RUNX2 (C), BMP4 (D), and ALP (E) (Sample size n = 4). (F) The protein expression level of the three proteins, right panel was the quantitative results (Sample size n = 3). “*”, “**”, “***”, “****” represent p

Based on the results of fluorescence staining, the CCK-8 assay, ALP staining, RT-PCR, and the mechanical properties of the four scaffold groups, the 70% HAMT-CHS scaffold was selected for subsequent experiments. The results of Western blot analysis showed that higher expression of the OPN, OSX and RUNX2 proteins in the 70% HAMT-CHS group compared to the CHS group (p-value

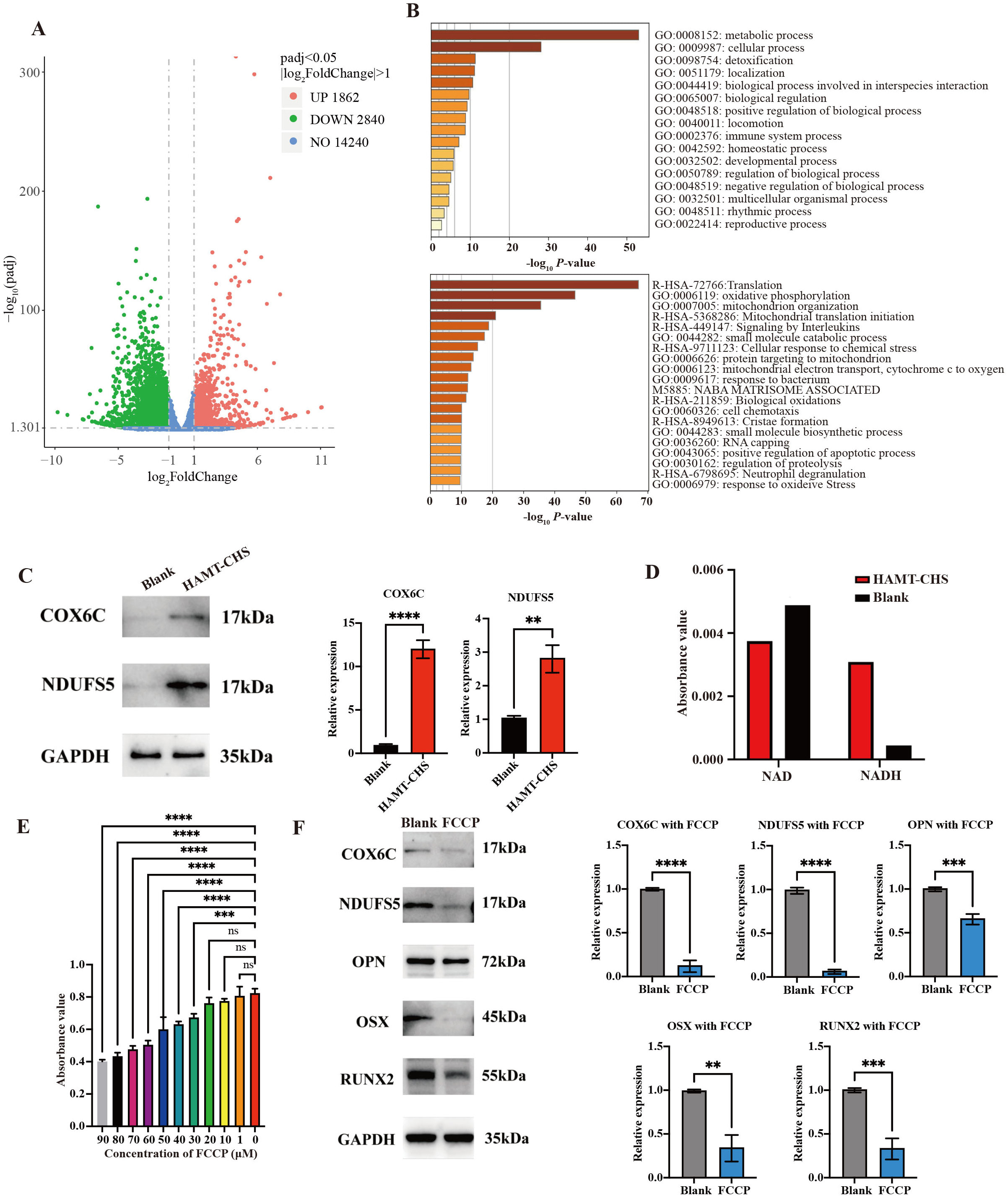

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms for the effect of HAMT-CHS scaffolds on the BMSCs phenotype RNA-seq analysis was performed on BMSCs co-cultured with 70% HAMT-CHS or CHS. A total of 4702 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified, including 1862 up-regulated and 2840 down-regulated DEGs (Fig. 6A). GO and KEGG analysis was then performed on all up-regulated DEGs, with the results indicating a significant enrichment of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (Fig. 6B). NDUFS5 and COX6C are the key genes in this pathway, and their higher expression levels in HAMT-CHS group was verified by Western blot analysis (p-value

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. HAMT-CHS activated the oxidative phosphorylation pathway of BMSCs. (A) Volcano plot showing the number of DEGs. (B) GO (top) and KEGG (bottom) enrichment analysis results for up-regulated DEGs. (C) WB results showing the expression levels of oxidative phosphorylation related proteins COX6C and NDUFS5; right panel was the quantitative results (Sample size n = 3). (D) Detection of the expression of NAD/NADH content in BMSCs. (E) CCK-8 assay results to predict cell proliferation level affected by FCCP (Sample size n = 4). (F) WB results showing the expression levels of osteogenic differentiation related proteins (Sample size n = 3); right panel was the quantitative results. “**”, “***”, “****” represent p

To further validate the biological functions of the HAMT-CHS scaffold in vivo, we performed the animal experiment described in the (Materials and methods part). Two months after surgical operation, Micro-computed tomographic results indicated a significant reduction in t the size of the rat skull defect. The red area shown in Fig. 7A,B represent the initial defect location and size (Fig. 7A,B). Compared to the blank group, the HAMT-CHS groups showed significantly different BS, Tb.N, BS/TV, and BV/TV values, while Tb.Th, Tb.Sp, and BS/BV showed no significant difference (p-value

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Animal experiment validated the biocompatibility of HAMT-CHS. (A,B) Micro-CT images. The red part marks the new bone. Scale bar: 5 mm. (C) Bone tissue related evaluation indicators: BS, BV, Tb.N, BS/TV, BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.Sp, and BS/BV; “*” represents p

The scaffold composition and the chemical composition of its surface determine its ability to attach cells. The scaffold structure plays a key role in controlling the ability of cells to migrate. The ideal scaffold structure is conducive to cell penetration. Moreover, it also allows nutrients and oxygen to flow into the scaffold, and waste products produced by the cells to flow out, thus improving cell survival. The design of scaffolds must therefore include sufficient porosity, which need to be large enough to allow the distribution of cells. Many researchers have investigated the effect of void size on bone regeneration [22, 23]. Kuboki et al. [24] reported that the optimal osteogenic pore size of porous HAP blocks was 300–400 µm.

Smaller diameter pores (90–120 µm) in straight tunnel structures of different diameters in honeycombed HAP can induce cartilage formation and then bone formation, while larger diameter tunnels (350 µm) induce bone formation directly within the tunnel [24]. Zhang et al. [25] reported that the pore size of 150–250 µm in a collagen porous gradient scaffold provides a more favorable three-dimensional microenvironment for cartilage matrix expression and cartilage differentiation. Moreover, small pores are more easily filled with proliferating cells, thus increasing the interaction between cells [25]. Oh et al. [26] synthesized polyacetate gradient pore size scaffolds by centrifugation, and found great differences in the growth of cells and tissues according to the pore size of the scaffolds. Chondrocytes and osteoblasts grow well with a pore size of 380–405 µm, fibroblasts in a pore size of 186–200 µm, while a pore size of 290–310 µm was more suitable for bone formation [26]. Griffon et al. [27] found that chondrocyte proliferation and metabolic activities were more active in chitosan scaffolds with a pore size of 70–120 µm. Li et al. [28] prepared HAP scaffolds with three different large pore sizes of 500–650 µm, 750–900 µm, and 1100–1250 µm. The rates of angiogenesis and osteogenesis observed in the 750–900 µm large-aperture scaffolds were significantly faster than those of the other two large-aperture scaffolds, and the new bone was evenly distributed. These results demonstrate the importance of appropriately large apertures in HAP scaffolds with similar interconnect structures, thereby providing an environment for heterotopic osteogenesis and angiogenesis [28]. Furthermore, the pores need to be connected to each other to allow cells to migrate between them. In general, cells distribute easily in the peripheral area of the scaffold, resulting in tissue regeneration only in the outermost layer. For successful tissue engineering, a uniform distribution of cells throughout the scaffold is required [29]. Amini and Nukavarapu [30] speculated that insufficient vascularization inside the scaffold would lead to insufficient oxygen tension and a lack of nutrient supply, leading to cell death and thus affecting bone formation. By optimizing the pore distribution and porosity, the survival of cells in the scaffold could be improved and hence the formation of new bone increased [30]. Interconnected pores increase the ability of cells to proliferate, and speed up the flow of nutrients and elimination of waste. Moreover, the rate of material degradation was found to be inversely proportional to the porosity [31]. Porosity is a very important issue, and refers to the remaining spatial proportion of scaffolds with tissue growth during the process of bone defect repair. This has a major influence on the proliferation of osteoblasts and on the ability to induce bone formation. Safari et al. [32] reported that the porosity of human bone ranges from 30% to 90%, and argued that the porosity of effective bone tissue regeneration scaffolds should be

The cells in scaffolds with uniform pores are more fluid, and thus more likely to flow through the scaffolds, thereby reducing the opportunity to react with the scaffold materials. The internal structure of natural bone tissue is not uniform, and the porous bone cancellous structure formed by the internal bone trabeculae gradually transitions to a dense bone structure with a dense surface. The osteogenic effect of scaffolds with gradient pore structure is better than that of scaffolds with uniform pore structure [35]. Sobral et al. [36] inoculated a gradient pore scaffold and a uniform pore scaffold with an equal number of cells. The gradient pore scaffold showed a higher rate of cell inoculation, and a more uniform distribution of cells, as observed by fluorescent staining [36]. A rough scaffold surface is more conducive to cell attachment and proliferation than a smooth surface. Wang et al. [37] found that a rough surface provides better anchoring for the filamentous foot. Calore et al. [38] inoculated cells on two different scaffolds and cultured them for 7 days to evaluate the expression of osteogenic genes. The expression of ALP in the scaffolds with rough surfaces and micropores was significantly higher than in PLLA scaffolds with smooth surfaces [38]. Gaharwar et al. [39] added nanoclays to electrospun polycaprolactone scaffolds to form rough surfaces. The roughness of these scaffolds was due to the diameter of the fibers and to the uneven distribution of nanoclays within the fibers. The cells can easily fill the substrate by anchoring and stretching over the microsized rough structure, resulting in increased metabolic activity of the adherent cells [39]. The bone formation seen after 12 weeks in of polypropylene glycol fumarate composite scaffold with ultra-short single-wall carbon nanotubes was 3-fold higher than the control scaffold. Furthermore, the porosity, surface roughness and chemical properties of the original scaffold were improved by carbon nanotubes [40].

Review of the literature reveals much discussion of, scaffold design, but there is no consensus on the most suitable factors for osteogenesis with regard pore size, porosity and surface roughness. It is generally believed that scaffolds with pores

The differentially expressed genes were identified by RNA-seq, KEGG and GO analysis subsequently showed that oxidative phosphorylation was significantly up-regulated in these scaffolds. The process of combining hydrogen atoms obtained from the metabolism of materials with oxygen to form water through the electron transport chain gradually releases energy that is stored in ATP. The oxidation of hydrogen and the phosphorylation of ADP are coupled during oxidative phosphorylation. During this process, hydrogen removed by intermediate metabolites is transferred by a series of enzymes or coenzymes, and is finally combined with oxygen to form water. This series of enzymes and coenzymes are referred to as hydrogen and electron carriers. They are arranged in a specific order on the inner membrane of the mitochondria to form the electron transport chain, also known as the respiratory chain. Hydrogen carriers or electron carriers have redox properties, and can transfer oxygen atoms and electrons. The hydrogen and electron transmitter components of the electron transport chain mostly belong to one of the following five categories: (1) Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) or coenzyme I; (2) One of the many kinds of flavin proteins, or flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cogroups; (3) Ferrothionein; (4) Ubiquinone; (5) Cytochrome (Cyt). One of the two electron transport chains in the body, starts with NADH and the other one starts with FAD. Inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation fall into two broad categories. The one category is electron transport chain inhibitors, such as rotenone, which block the transfer of electrons from NADH to ubiquinone; Antimycin A and dimercaptopropanol inhibit electron transfer from Cytb to Cytc. The other category is the uncoupling agents, that separate oxidation form phosphorylation so that ATP can no longer be produced [43].

NDUFS5 is a member of the NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) iron-sulfur protein family. The encoded protein is a subunit of NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). This is the first enzyme complex in the electron transport chain and is located on the inner mitochondrial membrane. COX6C, the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, catalyzes the electron transfer from reduced Cyt c to oxygen. It is a heteromeric complex consisting of three catalytic subunits encoded by mitochondrial genes, as well several structural subunits encoded by nuclear genes. The function of the mitochondrially-encoded subunits is electron transfer, while the nuclear-encoded subunits may be involved in the regulation and assembly of the complex. Therefore, the up-regulation of NDUFS5 and COX6C protein expression confirms activation of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway [43]. FCCP is a potent uncoupling agent for oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of ATP by transporting protons. In the present study, the expression of NDUFS5, COX6C, RUNX2, OPN, and OSX was examined following FCCP treatment. The expression levels were significantly lower, indicating that oxidative phosphorylation was inhibited and osteogenesis was reduced. Lee et al. [44] reported that osteoblast-mediated bone formation is usually powered by oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, both of which produce ATP. Safari et al. [45] found that phosphorylated proteins present in the extracellular matrix play a crucial role in regulating the mineralization process. Phosphorylated scaffolds provide new nucleation sites for mineral deposition within their collagen fibers. Recapitulating the function of natural phosphoproteins is an effective way to increase apatite formation [45]. Oxidative phosphorylation is also a major metabolic pathway for meeting the energy requirements of osteoclasts [46]. The mechanism underlying the effect of the scaffold on the expression levels of genes in oxidative phosphorylation is still unclear and requires further investigation.

The HAMT-CHS gradient pore scaffold has good biocompatibility, excellent porosity and a reasonable gradient pore structure. The results of both in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrate that HAMT-CHS has good osteogenic properties. High-throughput sequencing helped to understand the mechanism of osteogenesis induced by this scaffold. The previous study has also demonstrated that oxidative phosphorylation plays an important role in bone formation [43]. However, the mechanism by which scaffolds induce oxidative phosphorylation requires further study. In view of the good drug loading and slow-release ability of HAMT, osteogenic induction factors could also be loaded onto the scaffold at a later stage. Wax ball perforation technology can impact the biocompatibility of scaffold, and 3D printing technology also has the potential for further development. 3D printing has made it possible to directly combine materials, cells and growth factors to produce regenerative materials [47]. In the future, it may be possible find substances in natural foods that are similar to growth factors and can be loaded onto tissue engineering scaffolds to enhance the osteogenic induction effect [48]. This study provides practical experience in the design of biological scaffolds that should help to accelerate their clinical application in future.

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to some of the data may be used for future research but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

LSL: Ideas, Supervision. ZLZ: Performing the experiments, and data/evidence collection, writing the initial draft. WS: Methodology, Software. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on ‘Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments’ (ARRIVE) 2.0 guidelines. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Changzhi medical College, with approval No: DW2022082.

The authors thank the Central Laboratory of Changzhi Medical College for providing the experimental platform.

The present study was supported by grants from Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian province (2019Y9128). Heping Hospital affiliated to Changzhi Medical College University-level research fund (HPYJ 202407).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.