1 School of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine & Sciences, British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, King’s College London, SE5 9NU London, UK

Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most prevalent cause of mortality and morbidity in the Western world. A common underlying hallmark of CVD is the plaque-associated arterial thickening, termed atherosclerosis. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the aetiology of atherosclerosis remain unknown, it is clear that both its development and progression are associated with significant changes in the pattern of DNA methylation within the vascular cell wall. The endothelium is the major regulator of vascular homeostasis, and endothelial cell dysfunction (ED) is considered an early marker for atherosclerosis. Thus, it is speculated that changes in DNA methylation within endothelial cells may, in part, be causal in ED, leading to atherosclerosis and CVD generally. This review will evaluate the extensive evidence that environmental risk factors, known to be associated with atherosclerosis, such as diabetes, metabolic disorder, smoking, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia etc. can affect the methylome of the endothelium and consequently act to alter gene transcription and function. Further, the potential mechanisms whereby such risk factors might impact upon the activities and/or specificities of the epigenetic writers and erasers which determine the methylome [the DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs) and Ten Eleven translocases (TETs)] are considered here. Notably, the TET proteins are members of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily which require molecular oxygen (O2) and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) as substrates and iron-2+ (Fe II) as a cofactor. This renders their activities subject to modulation by hypoxia, metabolic flux and cellular redox. The potential significance of this, with respect to the impact of modifiable risk factors upon the activities of the TETs and the methylome of the endothelium is discussed.

Keywords

- modifiable risk factors

- cardiovascular disease

- endothelial dysfunction

- DNA methylation

- TETs

- DNMTs

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for about one-third of all deaths globally [1]. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified mutations/polymorphisms in genes linked to lipid metabolism, inflammation, vascular function and structural integrity which can influence the risk of developing CVD [2]. However, such genetic predisposition accounts for only a small percentage of overall cases [3]. Rather, the prevalence of CVD is largely due to environmental cues, where modifiable risk factors such as diets high in cholesterol, sodium, and sugar, along with physical inactivity and smoking, are recognised as independent and major contributors to CVD [4]. Notably, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified air pollution as the most significant risk factor for CVD, contributing to approximately 25% of the global CVD burden [5]. The precise mechanisms which underlie the aetiology and progression of the environmentally-triggered disease remain unknown but typically involve significant changes to the body’s redox balance and inflammation, leading to sustained alterations in biochemical and physiological systems [2, 6].

Despite the diverse manifestations of CVD, the pathologies commonly stem from atherosclerosis (AS). AS is a slow, progressive disease of the arterial blood vessels, and is typically associated with chronic low-level inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular wall remodeling [7]. One of the earliest stages in this remodelling process involves dysfunction of the endothelium, which is a crucial regulator of vascular homeostasis and is therefore a key target for early detection and intervention in CVD [8]. Endothelial dysfunction (ED) is a systemic disorder which is an independent predictor of pathological cardiovascular events, in which the endothelium manifests as more vasoconstrictive, pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic. Evidence suggests that multiple factors, including traditional modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, together with ageing, gender, and emerging risk determinants such as sleep disorders, gut microbiome alterations, clonal haematopoiesis and foetal factors can all act to promote this more dysfunctional endothelial phenotype [9]. The hallmark of ED is a significant reduction in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability owing to impaired activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and/or increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [10], and this associates clinically with impaired brachial artery flow-mediated dilation [11]. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms which might underlie the development of endothelial dysfunction (ED) such as in response to exposure to environmental CVD risk factors may therefore prove to be critical in the development of effective therapeutic strategies to prevent and/or treat AS [12].

The maintenance of vascular integrity is key to the normal functioning of blood vessels and consequently, vascular homeostasis. The vasculature act as the bridge between the blood and the tissues, providing the all-important oxygen and nutrients to ensure cell survival whilst removing any waste and other harmful products for disposal. The general architecture and cellular composition of blood vessels is similar throughout the vascular system. It comprises the tunica externa (outer layer), the tunica media (middle layer), and the intima (inner layer) [13]. However, certain vessel characteristics will predominate according to the different functional requirements at different locations, i.e., arteries, veins, arterioles, venules, and the capillary vessels.

The endothelium—comprising of a single layer of endothelial cells—forms the inner lining of blood vessels, at the intima. Once considered only as a mechanical barrier, we now understand the endothelium to be much more than that. Optimally positioned between the underlying tissue and the blood itself, this semi-permeable barrier is now regarded as a highly dynamic organ [13] which plays critical roles in vascular biology and pathophysiology. It not only helps preserve the structural integrity of blood vessels but also responds to both chemical and physical stimuli via the production of a wide variety of factors.

There are two broad categories that blood vessels fall under—microvasculature and macrovasculature. The microvasculature consists of small arterioles, capillaries, and venules, which play a crucial role in regulating local blood perfusion and facilitating metabolic exchanges between the circulatory system and peripheral tissues. Meanwhile, the macrovasculature are the arteries and veins which are responsible for transporting blood to and from organs [14]. In larger vessels, the intima will consist of not only endothelial cells but also some smooth muscle cells and elastic fibres, which help maintain the vascular tone. However, in the smaller vessels such as the capillaries, the endothelial cells will be the only component of the entire vessel wall [15]. Dysfunction of both micro- and macro-vascular endothelial cells have been shown to be predictors of future cardiovascular events [16, 17, 18]. However, in the case of AS, it is dysfunction of the macrovascular endothelial cells of the large (proximal) arteries that is of most clinical relevance [19].

In normal vascular homeostasis, the endothelium also has the role of controlling the transfer of molecules across the vessel wall (in a size-selective manner) via the paracellular pathway (involving interendothelial junctions) or the transcellular pathway (across the endothelial cell itself) [20, 21]. In the first instance, the movement of small ions, hydrophilic macromolecules, and water are controlled by tight junctions which are primarily composed of claudins, occludins, and junctional adhesion molecules and all play key roles in regulating the permeability of tight junctions [21]. On the other hand, the transcellular pathway shuttles a wide range of molecules, from (more hydrophobic) macromolecules such as lipoproteins and antibodies to smaller molecules such as amino acids, anions, and cations from one polar side to the other polar side of the endothelial cell using vesicles or receptor-mediated uptake and diffusion [22].

Furthermore, the endothelium can regulate blood flow and therefore vascular tone through the secretion of various vasoactive factors [13]. These vasoactive factors could be vasodilatory in nature such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2), or vasoconstrictive such as endothelin-1 (ET-1) or thromboxane (TXA2). The effects these factors elicit are all involved in altering intracellular free Ca2+ concentration in vascular smooth muscle cells which in response leads to the constriction or dilation of the vessel wall.

Finally, another important role of the endothelium is the recruitment of leukocytes to a site of tissue injury during an inflammatory response [23]. Transendothelial migration (TEM) is a multistep adhesion cascade in which leukocytes, such as neutrophils, become progressively more adhesive to the endothelium involving a number of cell adhesion molecules such as selectins, integrins and their respective ligands [24, 25]. The leukocytes then migrate through the endothelium via the paracellular route, whereby signalling events occurring on the interendothelial junctions lead to increased leukocyte trafficking caused by loosening the adhesive contacts of vascular endothelin cadherin (VE-cadherin) [24]. Alternatively, in a less common transcellular route, leukocytes pass directly through an individual endothelial cell, in a process involving the formation of a channel or pore [26].

Given its prominence in regulating key processes relating to vascular homeostasis, the endothelium must be able to react constantly and appropriately both to acute and chronic changes in environmental cues. Thus endothelial cells can effect rapid (and reversible) changes in vascular tone, permeability, coagulant activity and inflammation in response to stimuli from the circulation or microenvironment [27]. Post-translational mechanisms involving acute signalling pathways clearly play major roles in such homeostatic responses. For instance, the production of NO (and hence regulation of vascular tone), can be modulated acutely by phosphorylation of eNOS at multiple sites which are induced via signalling cascades activated by external cues such as changes in shear stress, intracellular calcium levels and ATP concentrations [28]. In addition, rapid and reversible changes in the endothelial cell transcriptome have been demonstrated to modulate function in response to, for example, hypoxia [29], hyperglycaemia [30] and disturbed shear stress [31]. In the case of hypoxia, these can be mediated by the well-documented, [O2]-dependent, post-translational changes in the stability and activity of the hypoxia-inducible (master transcriptional regulatory) factors (HIFs) [32, 33]. In addition, endothelial cells can rapidly induce the transcription of other known master transcriptional regulators, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1

In addition to the modulation of activity/expression of such master transcription factors, gene transcription is in parallel regulated at the level of epigenetics. This relates to (heritable) changes in cellular phenotype which are independent of the primary genetic sequence. It encompasses the study of changes in the accessibility of chromatin and hence gene expression, mediated by covalent modifications to the DNA and histone proteins of chromatin and some non-coding RNAs [37, 38].

Chromatin comprises a complex of genomic DNA and protein. The basic unit of chromatin organisation is the nucleosome in which DNA is wrapped around an octamer of histones [39]. Modifications to the histone proteins include phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitination at diverse sites which act to alter the chromatin structure [38, 40, 41]. These modifications can either increase the affinity between DNA and histones (thus repressing gene transcription), or alternatively decrease the affinity, making the unit less condensed and making transcription more likely to occur. Histone acetylation, due to its occurrence on basic amino acids, is associated with gene activation as the basic charged amino acids are neutralised and weaken the affinity between DNA and histones [42]. Conversely, some other modifications, such as methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3, are strongly associated with gene silencing [43, 44, 45].

By contrast to the large (and ever-increasing) number of observed histone modifications, with diverse effects on gene transcription rates, the genomic DNA of eukaryotic chromatin is principally only subject to modification by methylation at cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, which predominantly acts to repress gene transcription [37, 46].

DNA methylation is catalysed by the family of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), whereby a methyl group (-CH3) is transferred from S-adenyl methionine (SAM) onto the 5th carbon base of the cytosine ring (C5) forming 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) [47]. Thus, DNMTs are termed epigenetic writers. Conversely, the enzymes involved in removing these methyl marks are known as erasers, whilst proteins that recognise and bind the modified DNA and modulate the activities of associated factors are termed readers [48].

Three family members of DNMTs are responsible for methylating DNA under different environmental conditions. DNMT1 is responsible for replicating DNA methylation patterns from the parent DNA strand onto newly-synthesised daughter strands during DNA replication, ensuring the preservation of these epigenetic marks across successive cell divisions, whilst DNMT3A and DNMT3B are commonly described as de novo DNMTs for their ability to create new methylation patterns on unmodified DNA [49]. As stated above, DNA methylation occurs almost exclusively on cytosine residues within cytosine-guanine dinucleotides [37]. Genomic areas with a rich CpG deposit are known as CpG islands and these islands are typically 200 bp in size and are found at promoter regions [44]. It is regarded as a modification that is repressive [37, 46] and is considered to mediate its action by direct interference inhibition of transcription activator factor binding, or through the recruitment of specific transcriptional repressors to methylated DNA, such as methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MBPs), or by alteration of higher-order chromatin structure [46].

The MBPs are thus considered epigenetic readers [37, 50]. There are 11 members in this protein family and all of them share a common methyl-binding domain that enables them to recognise 5-mC. Generally, MBPs have been shown to play a role in maintaining higher-order chromatin structure and stability [51]. Thus, in addition to preventing the binding of transcription factors to their target sites, they can recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs) and other chromatin remodelling complexes leading to a closed chromatin state [52]. Accordingly, DNA demethylation plays a crucial role in gene regulation by counteracting the activities of DNMTs, thereby contributing to the level and specificity of DNA methylation [53].

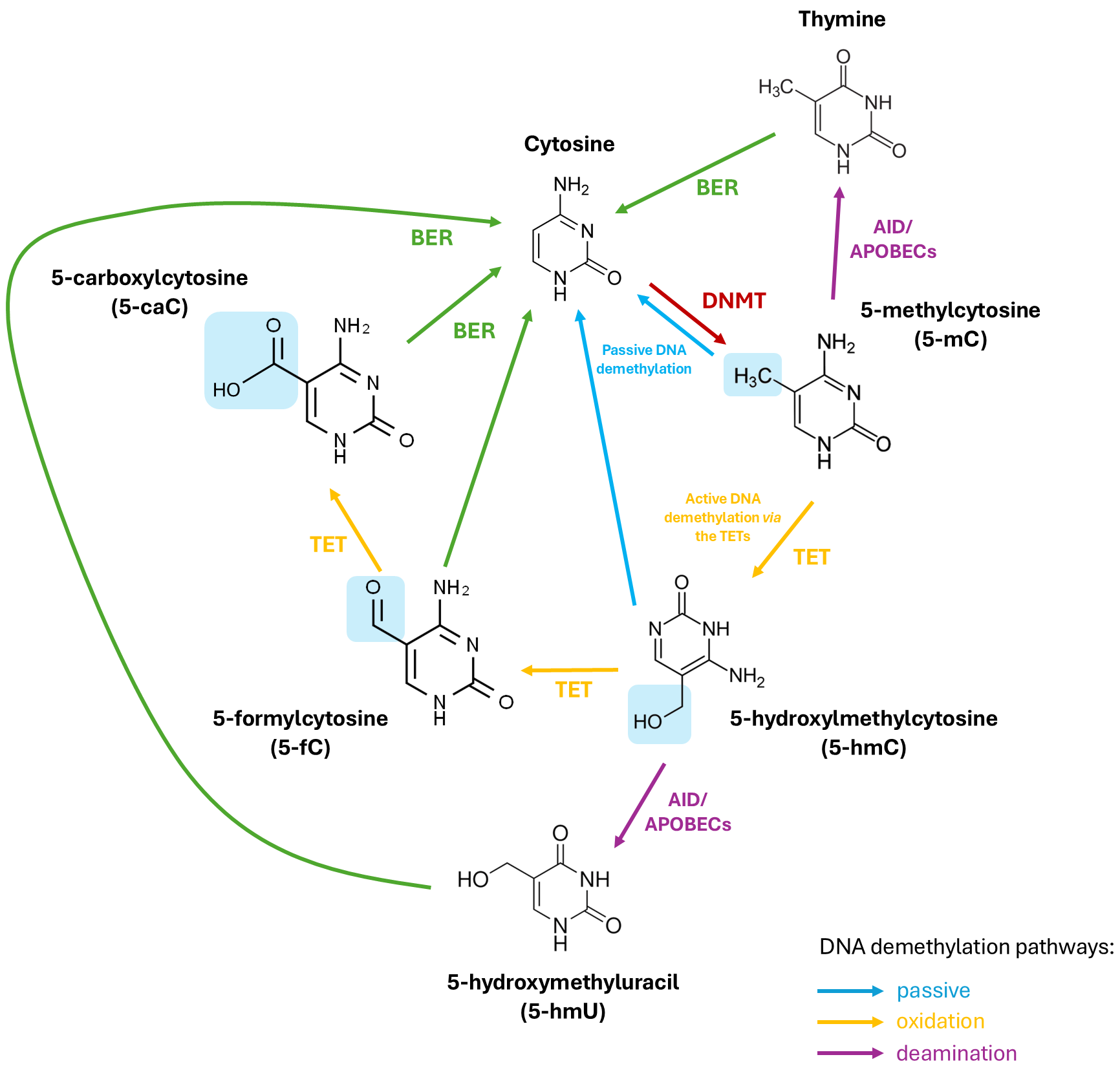

DNA methyl marks can be removed passively or actively. Passive DNA demethylation occurs during cell division when DNMT1 is inhibited allowing cytosine to remain unmethylated such that over successive cell division cycles, these methyl marks gradually disappear [47]. Conversely, active DNA demethylation necessitates an enzymatic process to revert 5-mC to its native cytosine form. As the covalent bonds linking cytosine to the methyl group are exceptionally strong, active DNA demethylation involves a series of enzymatic reactions involving deamination of the amine group of the methylated cytosine residue or oxidation of the methyl group of 5-mC in order to transform it to a cytosine variant. To restore this cytosine variant to its native form, the cytosine undergoes base excision repair (BER) mechanisms [47]. Deamination can take place through the action of the activation-induced cytidine deaminase/apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme (AID/APOBEC) resulting in the conversion of 5-mC to thymine. This process generates a guanine/thymine (G/T) mismatch upon which the BER pathway then acts to restore the thymine to an original, unmodified cytosine [47]. Alternatively, oxidation of the methyl group is facilitated by a family of enzymes referred to as the ten-eleven translocations (TETs) which function as the erasers of epigenetic marks.

5-hydroxylmethlycytosine (5-hmC) was discovered in bacteriophage DNA in the 1950s [54], but its relevance in the mammalian genome remained unclear until the identification of the gene at the breakpoint of the ten-eleven translocations (t(10;11) (q22;q23)) found in myeloid leukaemia which was termed TET1. TET1 was found to have enzymatic activity, capable of converting 5-mC to 5-hmC [55]. It is now understood that 5-hmC is a key intermediate in the active, oxidation-dependent, demethylation pathway. In this pathway, the TET protein(s) catalyse the oxidation of 5-mC to 5-hmC through hydroxymethylation [56] and also mediate the successive oxidation of 5-hmC to 5-formylcytosine (5-fC), and finally to 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC). The BER pathway, facilitated by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) [56], then replaces either 5-fC or 5-caC with the native form of cytosine, thus completely eliminating the methyl mark from cytosine [47] (Fig. 1). TETS are members of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily and consequently require molecular oxygen (O2) and

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The (DNA) methylation and demethylation of cytosine. DNMTs add a methyl group (-CH3) to cytosine on CpG islands making 5-methylcytosine (5-mC). TET enzymes then successfully oxidise 5-mC to 5-hydroxylmethylcytosine (5-hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5-fC), and finally, 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC) (via active demethylation). 5-mC and 5-hmC can also be converted back to cytosine passively through successive cell replication cycles. In an alternative deamination pathway, 5-mC or 5-hmC can be deaminated by activity-induced cytidine deaminase/apolipoprotein B mRNA editing complex (AID/APOBEC) deaminases to form thymine or 5-hydroxymethyluracil (5-hmU), respectively. Through base excision repair mechanisms (BER), 5-fC, 5-caC, 5-hmU, or thymine can be converted back to unmethylated cytosine. TET, ten-eleven translocation; DNMT, DNA methyl transferase; CpG, cytosine-guanine.

In mammals, the TETs comprise a family of 3 proteins: TET1, TET2, and TET3. Each of these TETs has a number of transcript and protein isoforms arising from differential splicing and the use of different promoters. Thus, in humans, 2 isoforms of TET1 have been identified, whilst 3 isoforms of TET2 and TET3 have been observed [58]. All three TETs are found to be widely expressed in all tissue types. However, each TET protein displays a different pattern of tissue- and developmental stage-specific expression, highlighting their distinct functions [59]. Within vascular cells, TET2, specifically, has been demonstrated to be of functional significance in regulating smooth muscle plasticity [60], and in regulating autophagy in endothelial cells [61].

Structurally, all three members possess a conserved core catalytic domain located at the C-terminus, consisting of two double-stranded

Given its regulatory role in gene transcription, alterations in DNA methylation should lead to differential gene expression and consequently, changes in cellular phenotype [65]. Ever-increasing evidence suggests that aberrant DNA methylation associate with common diseases [66]. Further, epigenome-wide association studies (EWASs) of incident pathologies are beginning to identify predictive biomarkers of disease. Such findings both support a causal role for aberrant methylation in disease aetiology and shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying disease progression [67, 68]. This association of aberrant DNA methylation and human disease has been extensively studied in the cardiovascular field. Specifically in the case of large-artery AS, several retrospective studies, investigating associations between AS-related traits and levels of global methylation, methylation at candidate gene loci and epigenome-wide methylation have been undertaken and systematically reviewed [69, 70]. To date, such studies have often given inconsistent results, due to the many confounding factors which can affect the epigenome, such as sex, ethnicity, age, lifestyle and socioeconomic status etc. Thus far, no consistent association between altered global levels of methylation (either hypo-or hyper-methylation) and CVD has become apparent. With regard to the candidate genes that have been investigated in more than one study (selected on the basis of previous genetic studies and/or biological function), consistent hypermethylation in the ESRa, ABCG1 and FOXP3 gene loci, and hypomethylation in the IL-6 gene loci have been identified as being associated with CVD [69]. The direction of change of the methylation correlates with the altered gene expression (decreased expression from hypermethylated loci and increased expression from hypomethylated loci) that has been observed or might be predicted, in the diseased state [71, 72, 73].

The findings from unbiased, EWASs have been particularly hard to reproduce in replicate cohorts, due to both confounding factors as described above and (in most cases) their relatively small sample sizes. Nevertheless, an increasing number of differentially methylated loci have been identified in more than one EWAS, which correspond to genes relating to lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, inflammation and obesity [69]. A very recent systematic review of studies examining the associations of DNA cytosine methylation and CVD, including EWASs, has identified 1452 CpG sites mentioned in at least 2 publications, 441 CpG sites mentioned in at least 3 publications and 2 sites (proximal to the Zinc Finger Protein 438 and F2R Like Thrombin or Trypsin Receptor 3 genes) that were reported in at least 6 studies. With respect to mapped genes displaying differential methylation, 5807 have thus far been mentioned in at least 2 studies, with transcriptional enhanced associate (TEA) Domain Factor 1 and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Type N2 being the most frequently reported [74]. An easily accessible and searchable database has been created by aggregating all such CpG and gene-related information that can be used for future research. Thus, although further studies, involving larger sample sizes are needed to validate current findings and determine whether the changes in methylation are consistent with differential gene expression in CVD, there seems little doubt that the identification of differential DNA methylation associated with CVD will prove of great clinical value in the foreseeable future.

The overwhelming majority of these methylation studies analyse blood samples, due to the ease of sample collection, or (in some cases) bulk vascular tissue. Indeed, a recent study, interrogating differentially-methylated regions genes and differentially-expressed genes within atherosclerotic (compared to normal) aortic tissue, has revealed information regarding the enrichment of specific immune cell populations within the atherosclerotic plaque [75]. However, the challenge of correlating ED with altered methylation specifically within the endothelium in human studies in vivo is currently unrealistic. Nevertheless, there are many in vitro studies which link environmental cardiovascular risk factors to altered endothelial cell methylation and function, suggesting that the altered methylation may be causal in the cellular dysfunction.

Many of the independent CVD risk factors, associated with the sedentary lifestyle and overabundance of high-calorie food intake in modern society, comprise changes in blood plasma composition, such as hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinemia, hyperlipidaemia (including hypercholesterolemia), hyperhomocysteinemia and hyperleptinemia [76, 77, 78, 79, 80]. The direct, pathogenic effects of such changes (as might be experienced in vivo) upon both microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cell function have, in many cases, been demonstrated in vitro [30, 81, 82, 83].

Similarly, air pollution and smoking can reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and result in exposure of endothelial cells to hypoxia, and in the accumulation of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), both of which are known to impact negatively upon endothelial cell function in vitro [84, 85]. Chronic exposure to risk factors, such as high cholesterol and smoking, additionally exacerbates the susceptibility of the endothelium at bifurcations and curvatures of the arterial tree, to the deleterious effects of disturbed flow [86] as can also be observed in vitro [87].

Further, changes in global and/or locus-specific endothelial cell methylation, resulting from such exposure, as described above, have also been extensively studied in various endothelial cell types in vitro. For instance, in human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs), transiently exposed to different (patho)physiologically relevant levels of glucose, differentially-methylated genomic regions (DMRs) encompassing over 2000 gene loci have been identified. These DMRs included loci associated with a disproportionate number of genes involved in angiogenesis and nitric oxide signalling cascades. Further, the differential methylation at these loci was typically shown to correlate with altered expression of their associated gene transcripts [88]. The effects upon the endothelial cell methylome, arising from exposure to hyperglycaemia and other CVD-associated, environmental risk factors are summarised in Table 1 (Ref. [88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114]). These studies included investigation of the effects of hypoxia, altered blood flow, hyperhomocysteinemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, oxidised low density lipoprotein (LDL), and tobacco smoke and provide a framework for investigations of the molecular mechanisms underpinning aberrant DNA methylation and CVD risk factors. The associations of altered methylation with exposure to agents which cause cellular dysfunction clearly do not prove their functional role in such dysfunction (or, in vivo, in the associated disease). Nonetheless, the changes in the methylation patterns on specific gene loci involved in vascular homeostasis (notably eNOS; reviewed in 2021 [115]), together with the observed changes in transcriptional expression of such critical genes are clearly compelling. Further, treatments that reverse methylation (such as inhibition of DNMT) have often been shown to restore normal gene expression and endothelial cell function in these models, further highlighting the functional significance of the differential methylation [89, 90, 91, 116].

| Risk factor | Experimental design | Cell model and conditions | Hypo-/Hyper-methylation? | Conclusions/Outcomes | References |

| Hyperglycaemia | Genome-wide DNA methylation quantification | Cultured human endothelial aortic cells (HAECs); diabetic (250 mg/dL), pre-diabetic (125 mg/dL), euglycemic (100 mg/dL) glucose concentrations for 72 hrs | Hypomethylation of NOS3 | Endothelial cells encode a glycaemic memory | Pepin et al., 2021 [88] |

| Hypermethylation of VEGF | Molecular pathways associated with angiogenesis are most statistically enriched | ||||

| Hyperglycaemia | Bisulfite sequencing of CXCR4 promoter | Cord-blood-derived CD34+ stem cells; mannitol 30 mM or glucose 30 mM until cells lost glucose tolerance then recovered in normoglycemic conditions for 3 days | Hypermethylation of CXCR4 promoter | Negatively affects migration ability towards SDF-1 | Vigorelli et al., 2019 [92] |

| Hallmarks of glycaemic memory after 3-day recovery in normoglycemic conditions | |||||

| Hyperglycaemia | Promoter DNA methylation assessed by bisulfite sequencing | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with low (5 mM) and high (25 mM) glucose for up to 48 hrs | Expression of ET-1 gene was upregulated in high glucose, but no change in methylation status at the promoter site | Increased expression of ET-1 gene may be in part due to increased oxidative stress | Binjawhar et al., 2023 [93] |

| Hyperglycaemia | Promoter DNA methylation patterns of the protein p66Shc adaptor protein investigated using methylation-sensitive or dependent enzymes | HAECs were exposed for 6 days to either normal (5 mmol/L) or high (25 mmol/L) glucose concentrations then to high glucose for another 3 days then to low glucose for a final 3 days | Hypomethylation of CpG dinucleotides following high glucose treatment | Glycaemic memory as hypomethylation of p66Shc did not change after normoglycemia was restored | Paneni et al., 2012 [94] |

| Hyperglycaemia | Genome-wide bisulfite sequencing analysing | Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRECs) and HUVECs were treated with either 5 mM or 25 mM glucose for 2 or 7 days | Predominant DNA hypermethylation | Increased hypermethylation observed in long-term culture compared with short-term culture | Aref-Eshghi et al., 2020 [95] |

| 88 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) for HUVECs and 8 for HRECs | Cell culture duration is a strong and more significant inducer of DNA methylation compared with glucose stimuli alone | ||||

| These DMRs are involved in the regulation of embryonic development (e.g., HOX) and cellular differentiation (e.g., TFG- | |||||

| Hyperglycaemia | Methylation analysis of SIRT6 was investigated by pyrosequencing-based methylation analysis | HAECs were exposed to either 5.5 mM (normal) or 30 mM (high) glucose for 7 days followed by 7 days of normal glucose | Hypomethylation of SIRT6 promoter in cells exposed to high glucose compared to normal glucose | Epigenetic change induced by hyperglycaemia may be related to the regulation of TET2 expression (which increased) | Scisciola et al., 2021 [96] |

| SIRT6 plays an important role in glucose homeostasis and metabolic disease; has been shown to be protective against endothelial dysfunction by being involved in the DNA-damage repair system | |||||

| Hypoxia | Methylation level of DRP1 promoter region was detected using primers for methylation and unmethylation of the DRP1 promoter | Human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs) maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 100% relative humidity or water-saturated atmosphere comprising 3% O2, 5% CO2 and 91% N2 (mimicking hypoxic conditions) for 24 hrs | Hypomethylation of DRP1 promoter under hypoxic conditions | Upregulation of DRP1 is involved in pulmonary vascular remodelling in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension | Wang et al., 2022 [97] |

| Hypoxia | MeDIP-qPCR used to detect methylation of RASAL1 promoter | Human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs) were maintained in a hypoxic-like environment for 72 hrs (1% O2, 98% N2) | Hypermethylation of RASAL1 | Hypoxia induces EndMT through different pathways, one of which involved DNMT3A-mediated hypermethylation of RASAL1 leading to constitutive Ras hyperactivity | Xu et al., 2016 [98] |

| Hypoxia | Bisulfite sequencing of the promoter region of human miR-21 | Human umbilical artery endothelial cells (HUAECs) exposed to normoxia (5% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 48 hrs | Hypermethylation of miR-21 gene promoter site in hypoxic HUAECs | HUAECs exposed to hypoxia showed a transient increase in eNOS and DDAH1 which may be in part due to miR-21 | Peñaloza et al., 2020 [99] |

| Disturbed flow | Differential CpG site methylation of KLF4 was measured by methylation-specific PCR, bisulfite pyrosequencing, and restriction enzyme PCR | HAECs were subjected to pulsatile undisturbed flow or oscillatory disturbed flow containing a flow-reversing phase | Hypermethylation of CpG islands within the KLF4 promoter under disturbed flow | Haemodynamics influence endothelial KLF4 expression. Downregulation of KLF4 is associated with atherosusceptibility | Jiang et al., 2014 [100] |

| Disturbed flow | Endothelial cells were stained with 5-mc antibody and visualised by epi-fluorescence microscopy | HUVECs were subjected to either pulsatile (athero-protective) or oscillatory shear (athero-prone) stress using a parallel plate circulating flow chamber for 24 hrs | Hypermethylation of the nuclei of endothelial cells subjected to oscillatory shear force | Oscillatory shear induces expression of DNMT1 expression and is found to mediate the hypermethylation observed in endothelial cells | Zhou et al., 2014 [101] |

| DNMT1 expression was also quantified using qPCR | Atheroprone hemodynamic forces act as a risk factor for atherosclerosis | ||||

| Disturbed flow | Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) and microarray analyses to investigate global DNA methylation patterns | HUVECs were subjected to either unidirectional flow (laminar shear stress) or bidirectional flow (oscillatory shear stress) for 24 hrs | Hypermethylation of HoxA5, Tmem184b, Adamtsl5, Klf3, mklr1, Pkp4, Acvrl1, Dok4, Spry2, and fp46 genes at the promoter region | DNMT1 was enhanced by oscillatory shear stress and a reduction in DNMT activity resulted in reduced OS-induced endothelial inflammation | Dunn et al., 2014 [89] |

| 5-aza and siRNA treatment of HUVECs to understand DNMT enzymatic activity | HoxA5 and Klf3 could serve as a mechanosensitive master switch in gene expression | ||||

| Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hcy) | LOX-1 DNA methylation changes were examined using nested touchdown methylation-specific PCR (ntMSP) analysis | CRL-1730 endothelial cells were treated with either Hcy at different concentrations (0–500 µmol/L) or 100 µmol/L Hcy with 30 µmol/L vitamin B12 and 30 µmol/L folic acid for 72 hrs | Hypomethylation of LOX-1 in the Hcy-treated only groups | Hcy decreased the levels of DNMT1 | Ma et al., 2017 [102] |

| Hcy increased levels of NF- | |||||

| Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hcy) | CpG methylation in the human p66Shc promoter region was quantified by methylation-specific real-time PCR using bisulfite-converted genomic DNA | HUVECs were treated with 10–200 µM Hcy for 48 hrs | Hypomethylation of CpG (6,7) in the p66Shc promoter | Hcy upregulates p66Shc expression and is important in homocysteine-induced endothelial cell dysfunction | Kim et al., 2011 [103] |

| The effect of Hcy on the methylation status of CpG dinucleotides is gene- and site-specific | |||||

| Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hcy) | Bisulfite genomic DNA sequencing | HUVECs were treated with 50 µM DL-Hcy for 48 hrs | Hypomethylation of 2 cytosine residues in the cyclin A CpG island | Hcy inhibits DNMT1 activity | Jamaluddin et al., 2007 [104] |

| DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) activity assay | Hcy inhibits cyclin A transcription via hypomethylation-related mechanism leading to growth inhibition in endothelial cells; cyclin A promotes G1/S and G2/M transitions of the cell cycle | ||||

| Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hcy) | Methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (MS-PCR) was used to examine DNA methylation level of DDAH2 | HUVECs treated with Hcy (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 190, 30 mM) for 48 hrs | Hypermethylation of two CpG islands located in the promoter of DDAH2 in HUVECs treated with Hcy | Inhibition of DNMT1 using 5-aza prevented DDAH2 gene promoter from DNA hypermethylation | Jia et al., 2013 [90] |

| DDAH2 is a key enzyme for degradation for ADMA, ADMA is an endogenous inhibitor of NOS and can induce apoptosis of endothelial cells via increased oxidative stress | |||||

| H2O2 (ROS) | hMeDIP-qPCR analyses were carried out to detect methylation level of CpG islands of the ZO-1 promoter | HUVECs were treated with 10 µM H2O2 for 6 hrs | Hypermethylation of CpG islands in the promoter region of the ZO-1 gene following oxidation with H2O2 | H2O2 significantly decreased the expression of 5-hmC and ZO-1, a tight junction protein | Wang et al., 2022 [105] |

| TET activity was also found to be essential in regulating ZO-1 expression | |||||

| Inflammation | Global DNA methylation was measured using a microarray | HUVECs were treated with 20 ng/mL TNF- | Hypomethylation of (223) genes associated with autoimmune/inflammation, infectious and cardiovascular disease, and cancers | Several of the hypomethylated genes were located at the promoter regions | Rhead et al., 2020 [106] |

| Inflammation | Bisulfite sequencing of KLF2 promoter | Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were treated with 0–2 µg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 24 hrs | Hypermethylation at 12 CpG sites within the KLF2 promoter | Methylation of KLF2 modulated changes to eNOS and thrombomodulin, both of which confer potent anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory properties | Yan et al., 2017 [107] |

| These changes may be in part mediated by increased DNMT1 activity | |||||

| Inflammation | Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis | HUVECs were treated with 10 ng/mL TNF- | Hypermethylation in two distinct regions within the ACE promoter | Effects may be mediated by a transient decrease in DNMT3A and DNMT3B but not DNMT1 | Mudersbach et al., 2019 [91] |

| TET1 protein expression was downregulated | |||||

| DNA methylation decreased the binding affinity of the transcription factor X to the ACE promoter | |||||

| Hyperlipidaemia (Ox-LDL) | Global DNA methylation status was determined using a [3H] dCTP extension assay | HUVECs were treated with 0, 20, 40 µg/mL ox-LDL for 24 hrs at passages 0, 3, and 5 | Global hypermethylation following acute ox-LDL treatment | Initial challenge of Ox-LDL causes an increase in global DNA methylation but displays a resistance to development of apoptosis upon subsequent exposure to ox-LDL | Mitra et al., 2011 [108] |

| Gene-specific promoter methylation analysis using bisulfite sequencing | Hyper- and hypo-methylation at the promoter regions of individual genes observed | Effects of exposure to ox-LDL appear to be mediated by activation of LOX-1 by reducing NO synthesis, enhancing coagulation pathways, and inducing endothelial cells apoptosis | |||

| Hyperlipidaemia (Ox-LDL) | Global levels of DNA demethylation were assessed using 5-hmc antibody for immunofluorescence staining | HUVECs were pretreated with 5 mM total reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) and 20 µM nuclear factor- | Hypo-demethylation following ox-LDL treatment | Downregulation of TET2 and increasing NF- | Zhaolin et al., 2019 [109] |

| Hyperlipidaemia (Ox-LDL) | DNA methylation status of KLF2 promoter region was examined using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays | HUVECs were incubated with 200 µg/mL ox-LDL for 8 hrs | Hypermethylation of endothelial-KLF2 following ox-LDL treatment | Ox-LDL represses endothelial-KLF2 expression via DNA and histone methylation | Kumar et al., 2013 [110] |

| Downregulation of KLF2 leads to endothelial dysfunction | |||||

| Hypercholesterolemia | CpG methylation was quantified by methylation-specific real-time PCR using bisulfite-converted genomic DNA | HUVECs were treated 0, 50, 100, 200, 500 µg/mL LDL for 24 hrs | Hypomethylation of two CpG dinucleotides and acetylation of histone 3 in the human p66shc promoter following LDL treatment | The two CpG dinucleotides mediate LDL-stimulated p66shc promoter activity | Kim et al., 2012 [111] |

| P66shc mediates LDL-stimulated increase in expression of ICAM-1 and decreased expression of thrombomodulin | |||||

| P66shc is involved in LDL-stimulated adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells and plasma coagulation | |||||

| Smoking | The methylation status of the Bcl-2 promoter was observed by PCR amplification and sequencing of bisulphite converted DNA | HUVECs were treated with cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or CSE and 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza), or 5-aza and PBS for 12 hrs | Hypermethylation of Bcl-2 promoter region after CSE treatment | The interactions between anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated X (Bax) protein determines whether the mitochondria will release cytochrome c (cyc C), which is the initial factor for apoptosis | Zeng et al., 2020 [112] |

| Inhibiting Bcl-2 promoter methylation from cigarette smoke-induced aberrant methylation may prevent endothelial apoptosis | |||||

| Smoking | CpG methylation status was determined by methylation-specific PCR and direct bisulfite sequencing | HUVECs were treated with 2.5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) for 24 hrs after pretreatment with 1 µM 5-aza for 48 hrs | Hypermethylation of COX II | CSE induces aberrant COX II methylation and subsequent apoptosis in HUVECs | Yang et al., 2015 [113] |

| COX dysfunction is common in disease | |||||

| Smoking | Sequencing of bisulfite converted, PCR-amplified was carried out to understand the methylation status of CpG islands in the mtTFA promoter region | HUVECs were treated with cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or 1 µM 5-aza for 24 hrs | Hypermethylation of mtTFA | Mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA) regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation and thereby, its function | Peng et al., 2019 [114] |

| Inactivation of mtTFA promoter may contribute to the development and progress of COPD through cigarette smoke |

CXCR4, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; SDF1

As described above, there is compelling evidence to link environmental risk factors, associated with CVD to altered endothelial cell methylation and dysfunction. Thus, the cellular cues, impacted upon the endothelium by these risk factors, must act to alter either the activity and/or specificities of the epigenetic writers or erasers. Functional changes in the activities of the epigenetic modifiers could result from changes in their expression and/or catalytic activity, while changes in specificity probably result from altered interactions with binding partners. Evidence for the causal effect on CVD development of genetic mutations (which could affect any of these properties) in TET2 and DNMT3A specifically comes from studies on clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP). CHIP refers to mutations in haematopoietic cells that lead to their clonal expansion [117]. It is associated with an increased risk of developing haematological malignancies such as leukaemia [118] and also CVD [119]. Intriguingly, the two most commonly mutated genes which give rise to CHIP are DNMT3 and TET2 [117, 120]. Whilst this does not inform upon the specific role of altered DNA methylation in the endothelium, it is a clear demonstration of the functional significance of the altered expression and/or activities of these epigenetic modifiers in the development of CVD.

There is substantial evidence in the literature to suggest that environmental risk factors of CVD can alter DNMT expression and hence activity, and associate with an aberrant phenotype. Some of these studies are outlined in Table 2 (Ref. [121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130]). From these studies, it is evident that different observations are seen, depending on the cell type under investigation and whether it is in vitro or in vivo study. Nevertheless, it is clear that the expression of DNMTs is dynamic, tightly regulated and can be impacted by extracellular cues, although the precise mechanisms which underlie the changes in expression are not clear.

| Risk factor | DNMT expression level | Effect/possible causes | Reference |

| Tobacco smoke | Increased activity of DNMT1 in adenocarcinoma cells of smokers compared to non-smokers | Increased hypermethylation at the promoter region of tumour suppressor genes important in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma | Kwon et al., 2007 [121] |

| Alcohol consumption | Decreased DNMT3A and DNMT3B protein activity in patients with alcoholism compared to healthy controls in peripheral mononuclear cells | Despite a decrease in DNMT3 activity, there was increased global DNA methylation in patients with alcoholism, but this was due to elevated homocysteine | Bönsch et al., 2006 [122] |

| Alcohol consumption | Increased dose of ethanol increases DNMT1 and DNMT3A mRNA in amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis tissues of rats | This increase may be in part a compensatory mechanism to the decrease in DNMT1 protein activity | Sakharkar et al., 2014 [123] |

| Hyperglycaemia | Increased mRNA expression of DNMT3B in type 2 diabetes in HUVECs | Increased oxidative stress in T2D could facilitate activation of DNMT3B and subsequently, hypermethylation leading to an aberrant phenotype | Sultan and AlMalki, 2023 [124] |

| Hyperglycaemia | Decreased DNMT1 and DNMT3A expression levels following three months of hyperglycaemia in insulin deficient Ins2Akita mice | Increased oxidative stress (high ROS production) led to decreasing DNMT1 and DNMT3A activity | Maugeri et al., 2018 [125] |

| Hyperlipidaemia | Increased DNMT3B expression in the presence of ox-LDL in HUVECs | Increased DNMT3B activity led to a suppression of cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes (CREG), a vascular-protective molecule in atherosclerosis | Liu et al., 2020 [126] |

| Excess sodium intake | Increased DNMT3A expression in salt-sensitive rats | Increased DNA de novo (de)methylation in the kidney which contributed to the development of hypertension | Liu et al., 2018 [127] |

| Nutrient intake | Polyphenol-rich extracts (fruit and peel extracts) reduced the expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A in both the kidneys and liver | Reducing DNMT activity may delay malignant cell growth progression | Nowrasteh et al., 2023 [128] |

| Exercise | Acute exercise reduced the expression of DNMT3A and DNMT3B in leukocytes | Exercise triggered global hypomethylation and increased mRNA expression of PPARGC1A. PPARGC1A upregulated mitochondrial biogenesis | Hunter et al., 2019 [129] |

| Disturbed flow | Low and oscillating shear stress induces DNMT1 expression and DNMT-dependent genome-wide DNA methylation patters | 11 mechanosensitive genes such as HoxA5 and Flf3 were hypermethylated in their promoter region | Dunn et al., 2015 [130] |

| Methylation of cAMP-response elements (CRE) may act as a mechanosensitive master switch in gene expression |

T2D, type 2 diabetes; PPARGC1A, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha.

With regard to the (post-translational) regulation of activity, DNMTs use SAM as the methyl donor and are strongly inhibited by S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), which is produced as a result of this donation [131]. An altered SAM/SAH ratio and hyperhomocysteinemia (which typically results in elevated SAH levels) are both considered risk factors for AS development [79, 132] and likely act via inhibition of DNMT activity. Studies have also shown that both the activities and specificities of the DNMTs are modulated by cellular redox. Thus in the absence of SAM and in a pro-oxidant chromatin microenvironment (as, for instance, might be induced by smoking, hyperglycaemia or air pollution etc. [133]), DNMT3A/B may act to convert 5-mC or 5-hmC to unmodified cytosine [134], while oxidative damage of O6-methylguanine can inhibit DNMT binding, leading to hypomethylation [135]. Localised oxidative DNA damage, induced by H2O2 treatment, was also shown to recruit DNMT1 to sites of damaged chromatin and induce the formation of complexes (including DNMT3B), and thus act to relocalise DNA methylating, transcriptional-silencing activity to aberrant sites [136]. Some other studies, linking changes in DNMT activity to CVD risk factors, are also included in Table 2.

As is the case for DNMT expression, many studies have demonstrated the (transcriptional) expression of TETs to be dynamic and to be impacted by CVD environmental risk factors. Various modifiable environmental risk factors such as a diet rich in fat and the resulting change in blood flow, alcohol, smoking, as well as air quality have been shown to influence the expression of the TETs in vivo. Again, as was the case for DNMTs, conflicting results have been reported, which may reflect different experimental conditions. Several studies have also shown effects on TET2 transcription, specifically in endothelial cells, in vitro, resulting from altered shear stress and administration of oxidised low density lipoprotein (LDL). A brief overview showing the associations of different risk factors to TET expression is outlined in Table 3 (Ref. [137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150]).

| Risk factor | TET expression level | Effect/possible causes | Reference |

| High-fat diet | Increased expression of TET3 in the hearts of mice fed a high fat diet | Global changes to DNA hydroxymethylation have been shown to lead to cardiac hypertrophy e.g., Mef2C and Xirp2 | Ciccarone et al., 2019 [137] |

| High-fat diet | Decreased expression of TET1, TET2, TET3 in mice on a high fat diet | Increased ratio of (succinic acid + fumaric acid)/ | Pei et al., 2024 [138] |

| MEF2C upregulated, increased cardiac hypertrophy | |||

| Ox-LDL | Administration of ox-LDL downregulates TET2 expression in HUVECs | Downregulation of TET2 led to the downregulation of the CSE/H2S system, which serves as a protective mechanism against the development of atherosclerosis | Peng et al., 2017 [139] |

| The CSE/H2S system can inhibit NF- | |||

| Disturbed flow | Low shear stress down-regulates TET2 expression | Down-regulation of TET2 promoted endothelial mesenchymal transformation (EndMT) | Li et al., 2021 [140] |

| Disturbed flow | TET2 expression was downregulated under low shear stress in endothelial cells | Low shear stress downregulated genes involved in endothelial cell autophagy (important in maintaining cell health), namely BECLIN1 and LC3II, by impaired TET2 expression thus contributing to the atherogenic process | Yang et al., 2016 [141] |

| Disturbed flow | Low shear stress inhibited endothelial cell TET2 expression | Upregulated succinate dehydrogenase B (SDHB) expression by decreasing recruitment with HDAC2 | Chen et al., 2021 [142] |

| Increased SDHB leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, increases ROS generation, and pyroptosis | |||

| Smoking | Increased mRNA expression of TET1 but not in TET2 or TET3 following exposure to cigarette smoke extract (CSE) for 24 hrs in A549 cells | Dysregulated activity of TET enzymes has been identified as a causative mechanism in cancer | Kaur and Batra, 2020 [143] |

| TET1 (and TET2) play a crucial role in regulating the production of cytokines/chemokines in response to CSE challenge | |||

| Smoking | Decreased expression of TET2 in smokers | TET2 was among six genes identified from a genome-wide analysis in individuals with low values of forced expiratory volumes. These genes were associated with the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Wain et al., 2015 [144] |

| Suggests genetic predisposition plays a significant role in the development of lung diseases | |||

| Physical (in)activity | Hippocampal and hypothalamic TET1 and TET2 mRNA expression was increased after voluntary exercise | Higher hippocampal 5-hmC content in the promoter region of miR-137, a miRNA involved in adult neurogenesis | Jessop and Toldeo-Rodriguez, 2018 [145] |

| Exercise improved memory | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Increased TET1 mRNA expression in the cortex of psychotic (PS) patients comorbid with chronic alcohol abuse | Alcohol-associated global DNA hypomethylation is observed in several forms of cancer and other pathological conditions | Guidotti et al., 2013 [146] |

| A reduction of SAM was reported in the brain of alcoholic subjects | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Increased expression of TET1 in nucleus accumbens following chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) | Ethanol-induced epigenetic regulation altered behaviour c, accentuated withdrawal symptoms, towards alcohol | Finegersh et al., 2015 [147] |

| Alcohol consumption | TET1 expression substantially reduced in rats fed with ethanol | Inhibition of TET1 promoted apoptotic gene expression leading to increased hepatocyte apoptosis | Ji et al., 2019 [148] |

| Air pollution | TET enzymes were upregulated in human PBMCs following 4 hrs of exposure to diluted diesel exhaust | The expression of TET enzymes correlated with proinflammatory cytokine secretion in plasma | Li et al., 2022 [149] |

| Air pollution | Exposure of human bronchial epithelial cells to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) resulted in lower TET1 expression at 4 hrs but increased after 24 hrs. | Air pollution exposure resulted in time-dependent modulation of TET1 expression which in turn affects 5-hmC levels | Somineni et al., 2016 [150] |

| TRAP regulates TET1 which in turn, modulates 5-hmC levels and resulted in transcriptional activation of downstream genes such as VEGFA, known to be associated with lung function |

HDAC2, histone Deacetylase 2; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine.

As stated previously, as members of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily, the catalytic activities of TETs are dependent on molecular oxygen and a-ketoglutarate as substrates and Fe(II) as a co-factor [56, 57]. Further, their activities are inhibited by steric competition of a-ketoglutarate by the downstream tricarboxylic acid (TCA) metabolites, succinate and fumarate and the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) [151, 152], and by accumulation of the more oxidised iron cation, Fe(III) [153]. Thus, hypoxia, cellular metabolism and oxidative stress can all potentially affect the catalytic activities of TETs. Indeed, the effects of cellular oxygen availability, metabolic flux and redox have all been shown empirically to affect TET activity, using 5-hmC as a surrogate marker of that activity [154, 155, 156]. As has been discussed above, these cellular states are all known to be impacted by lifestyle risk factors associated with CVD. For instance, hyperglycaemia, associated with diabetes, can potentially change oxygen availability, metabolic flux and cellular redox [157], while smoking, hyperlipidaemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia are well-documented to be associated with oxidative stress [158, 159]. In addition, the catalytic requirement of TETs for Fe(II) renders them susceptible to diminished levels of vitamin C, which is required to recycle this more reduced form from Fe(III) [160] and intake of vitamin C is highly dependent on nutrition. Moreover, smokers have been shown to have depleted levels of vitamin C [161], further suggesting mechanistic associations between some CVD risk factors and altered TET activity. Changes in 5-hmC levels, taken as a measure of TET activity have been observed in both blood and solid organs as a result of acute glucose administration in vivo [162, 163] while peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from diabetic patients were found to display decreased levels of 5-hmC [164]. Altered 5-hmC levels in lung cells in vivo are also found to be associated with smoking-related cancers [165] and 5-hmC signatures in circulating cell-free DNA show the potential to become diagnostic and predictive biomarkers for coronary artery disease [166]. However, it should be noted that these changes in 5-hmC levels may result as a consequence of both altered TET expression and/or activity in the disease states.

TETs are increasingly being demonstrated to be regulated by a number of known post translational modifications (PTMs) which include phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, PAPylation, GlcNAcylation, and ubiquitination [58, 167]. Such PTMs can regulate both TET specificity and functional activity via modulation of, for example, their catalytic activity, stability, interactions with other chromatin-associated proteins, and DNA-binding capability. Furthermore, these can be affected by CVD risk factors such as hyperglycaemia. For instance, TET2 stability and activity have been shown to be regulated by phosphorylation at serine 99, mediated by AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) [164]. AMPK is both a cellular metabolic and redox sensor [168] and therefore high glucose and/or altered cellular redox could act to alter TET2 activity via an AMPK-dependent mechanism to account for the decreased levels of 5-hmC observed in the PBMCs of diabetics [169]. All three TET proteins are also known to interact strongly with the O-linked GlcNAc transferase, which adds a GLcNac group to serine and threonine residues of TET proteins and thereby regulates TET function by decreasing the number of available phosphorylation sites [170]. This O-linked GlcNAC posttranslational modification is highly regulated and linked to cellular metabolism as the donor sugar for O-GlcNAcylation (UDP-GlcNAc) is synthesized from glucose, glutamine, and UTP via the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway [171] and dysregulated O-GlcNAcylation has been linked to diabetes [172]. In addition, O-GlcNAc modification is increased under levels of oxidative stress [173], again suggesting dysregulation of O-GlcNAcylation as a potential mechanism to link CVD risk factors to altered TET function and DNA methylation.

Oxidative stress can also influence acetylation of TET2, such that (by contrast to the situation described above in section 4.4) it increases TET2 activity and stability. This was demonstrated by the addition H2O2 to human ovarian carcinoma (A2780) cells which resulted in increased global 5-hmC levels. Further investigations revealed that TET2 activity increased due to stress-induced p300-mediated TET2 acetylation, resulting in the enhanced binding to DNMT1. This tight binding to DNMT1 (and chromatin) protected against accumulation of abnormal DNA methylation (typically induced by oxidative stress) by converting 5-mC to 5-hmC [174]. This seemingly paradoxical effect of oxidative stress on TET activity may be context dependent (due to differences in cell type and/or species of ROS) or may reflect differences in adaptive versuspathological cellular responses to changes in cellular redox.

These are just a few examples highlighting how some of the risk factors of CVD could indirectly affect TET function via altering their post-translational modifications, and it is clear that these are complex relationships about which there remains much to discover.

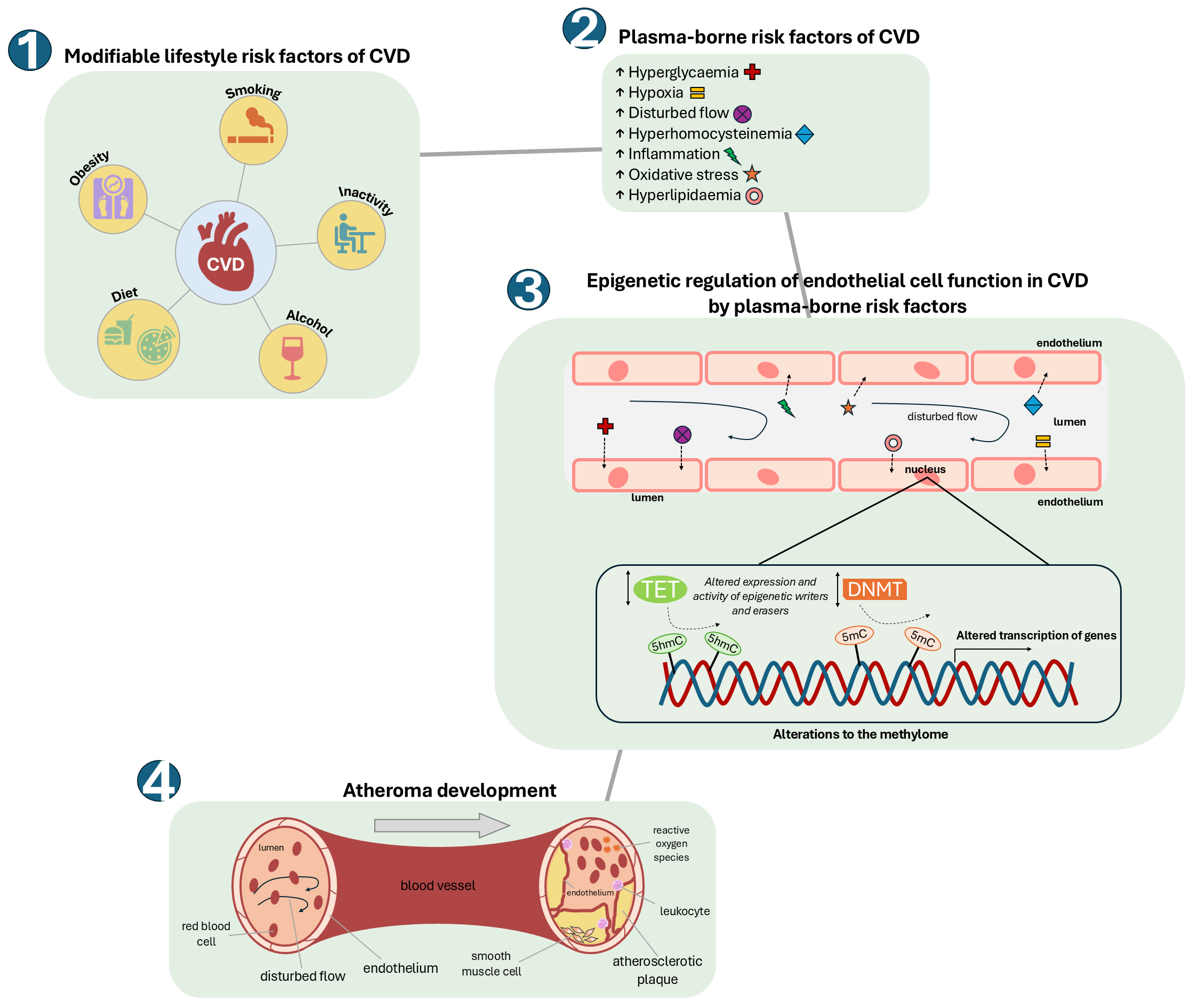

Epigenetic changes are now strongly believed to link so-called “modifiable” risk factors, associated with an unhealthy lifestyle. to the development of CVD. Further, aberrant DNA methylation, in particular, as a regulator of gene transcriptional expression, is increasingly believed to not only associate with, but to be causal in, the cellular dysfunction that characterises both the aetiology and progression of CVD. Dysfunction of the endothelium is likely to be one of the earliest steps in the development of AS, a common hallmark of most CVD, and therefore understanding how environmental risk factors might act to alter the methylome of the arterial endothelial cells is crucial to understanding the aetiology of CVD. As discussed here, the methylome of the endothelium, and changes associated with CVD in vivo are challenging to demonstrate. Nevertheless, aberrant DNA methylation and changed transcriptional expression in critical genes linked to endothelial cell function and homeostasis have been demonstrated in vitro by exposure to known risk factors.

We have explored here the evidence that these risk factors can alter epigenetic marks by modulating the expression and activities of the epigenetic erasers and writers, to highlight possible molecular mechanisms which might be critical in disease aetiology (summarised graphically in Fig. 2). It is also increasingly becoming evident that the specificity of these epigenetic modifiers may be mediated by their many binding partners [58, 59]. Although not fully addressed here, the expression/activity/availability of a specific binding partner might, of course, also be subject to modulation by the known environmental risk factors and this will, no doubt, be a topic of future investigations.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. How modifiable risk factors of CVD can alter the endothelial cell methylome, leading to the development of atherosclerosis. An unhealthy ‘Western lifestyle’ can lead to significant changes in plasma levels of modifiable risk factors of CVD such as hyperlipidaemia (including hypercholesterolemia), hyperglycaemia and hyperhomocysteinemia, together with lower available molecular oxygen (hypoxia), increased reactive oxygen species (oxidative stress) and alterations in blood flow. These changes can impact upon the activities and/or specificities of epigenetic modifiers (TETs and DNMTs) within the cells of the endothelium to alter the endothelial cell methylome and transcriptome. This in turn can result in endothelial dysfunction and consequent development of atherosclerosis.

The millions of methylation sites within the human methylome together with the complex interactions involved in the pathology of ED and CVD make the combination of artificial intelligence and network medicine a certain and powerful future approach to understanding the role of the methylome in CVD. By integrating methylation data with other epigenetic data, together with transcriptomic and functional genomic data, the construction of disease models, dependent upon methylation at key regulatory regions will become possible [175, 176]. The identification of specific methylation marks, that are characteristic and/or causal in disease together with elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of the pathology, would clearly inform the development of diagnostic and predictive biomarkers and novel therapeutics. However, it should also be noted that aberrant epigenetic marks are dynamic and are increasingly being demonstrated to be reversible by environmental factors associated with a healthy lifestyle, such as exercise and cessation of smoking [177, 178]. Therefore, greater emphasis and importance should also perhaps be given to public health campaigns which encourage healthier lifestyles, in both the prevention and treatment of CVD [179].

HS and AB both contributed equally and totally to the to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition of all references for the work and the construction of the figures and tables. HS and AB both contributed substantially to the writing of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We thank Dr. John Pizzey for critical reading of this manuscript.

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation, Student grant FS/4yPhD/F/21/34154.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.