1 Department of Neurology, Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical School, University of Szeged, H-6725 Szeged, Hungary

2 Doctoral School of Clinical Medicine, University of Szeged, H-6720 Szeged, Hungary

3 Department of Pediatrics, Albert Szent-Györgyi Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, H-6725 Szeged, Hungary

4 HUN-REN-SZTE Neuroscience Research Group, Hungarian Research Network, University of Szeged (HUN-REN-SZTE), Danube Neuroscience Research Laboratory, H-6725 Szeged, Hungary

5 Department of Medical Physics and Informatics, Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical School, Faculty of Science and Informatics, University of Szeged, H-6720 Szeged, Hungary

6 Department of Biomedicine, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, 812-8582 Fukuoka, Japan

7 Center of Biomedical Research, Research Center for Human Disease Modeling, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, 812-8582 Fukuoka, Japan

8 Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Neuroscience, Faculty of Science and Informatics, University of Szeged, H-6726 Szeged, Hungary

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Memory and emotion are especially vulnerable to psychiatric disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is linked to disruptions in serotonin (5-HT) metabolism. Over 90% of the 5-HT precursor tryptophan (Trp) is metabolized via the Trp-kynurenine (KYN) metabolic pathway, which generates a variety of bioactive molecules. Dysregulation of KYN metabolism, particularly low levels of kynurenic acid (KYNA), appears to be linked to neuropsychiatric disorders. The majority of KYNA is produced by the aadat (kat2) gene-encoded mitochondrial kynurenine aminotransferase (KAT) isotype 2. Little is known about the consequences of deleting the KYN enzyme gene.

In CRISPR/Cas9-induced aadat knockout (kat2-/-) mice, we examined the effects on emotion, memory, motor function, Trp and its metabolite levels, enzyme activities in the plasma and urine of 8-week-old males compared to wild-type mice.

Transgenic mice showed more depressive-like behaviors in the forced swim test, but not in the tail suspension, anxiety, or memory tests. They also had fewer center field and corner entries, shorter walking distances, and fewer jumping counts in the open field test. Plasma metabolite levels are generally consistent with those of urine: antioxidant KYNs, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, and indole-3-acetic acid levels were lower; enzyme activities in KATs, kynureninase, and monoamine oxidase/aldehyde dehydrogenase were lower, but kynurenine 3-monooxygenase was higher; and oxidative stress and excitotoxicity indices were higher. Transgenic mice displayed depression-like behavior in a learned helplessness model, emotional indifference, and motor deficits, coupled with a decrease in KYNA, a shift of Trp metabolism toward the KYN-3-hydroxykynurenine pathway, and a partial decrease in the gut microbial Trp-indole pathway metabolite.

This is the first evidence that deleting the aadat gene induces depression-like behaviors uniquely linked to experiences of despair, which appear to be associated with excitatory neurotoxic and oxidative stresses. This may lead to the development of a double-hit preclinical model in despair-based depression, a better understanding of these complex conditions, and more effective therapeutic strategies by elucidating the relationship between Trp metabolism and PTSD pathogenesis.

Keywords

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- depression

- anxiety

- tryptophan

- kynurenine

- microbiota

- oxidative stress

- transgenic mice

- translational medical research

- CRISPR/Cas9

The interaction between memory and emotion involves a complex interplay of neural, cognitive, and physiological processes involving the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Orderly function at multi-layered levels is essential to maintaining sound mental well-being [7, 8, 9, 10]. The reciprocal interaction between cognitive function and affective states can significantly impact each other. Cognitive impairment can lead to affective disturbances, triggering emotional responses such as frustration, anxiety, and stress, particularly when individuals feel a loss of control over their cognitive abilities [11]. Similarly, emotional disturbances such as depression and anxiety can influence memory function, increasing vulnerability to cognitive challenges [12, 13, 14, 15]. This intricate bidirectional link between cognition and emotions can lead to changes in brain structure, function, behavior, lifestyle, and neurotransmitter systems [15, 16, 17]. Memory impairment and emotional disturbance are associated with a wide range of systematic diseases and neuropsychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, major depressive disorder (MDD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26].

The serotonergic nervous system plays an important role in regulating mood, anxiety, and cognition [27, 28, 29, 30]. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is involved in cognitive processes such as attention, learning, and memory [31, 32, 33, 34]. Studies indicate that 5-HT enhances long-term memory consolidation and improves cognitive flexibility, which is the ability to switch between different cognitive tasks or mental sets [35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. 5-HT is implicated in regulating mood and anxiety, influencing cognitive function [45, 46]. Mental illnesses like MDD, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia (SCZ), and PTSD are associated with dysregulation of 5-HT [47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly used for these conditions, targeting the serotonergic nervous system [53, 54, 55]. Furthermore, abnormalities in the serotonergic system also affect norepinephrine and dopamine [56, 57, 58].

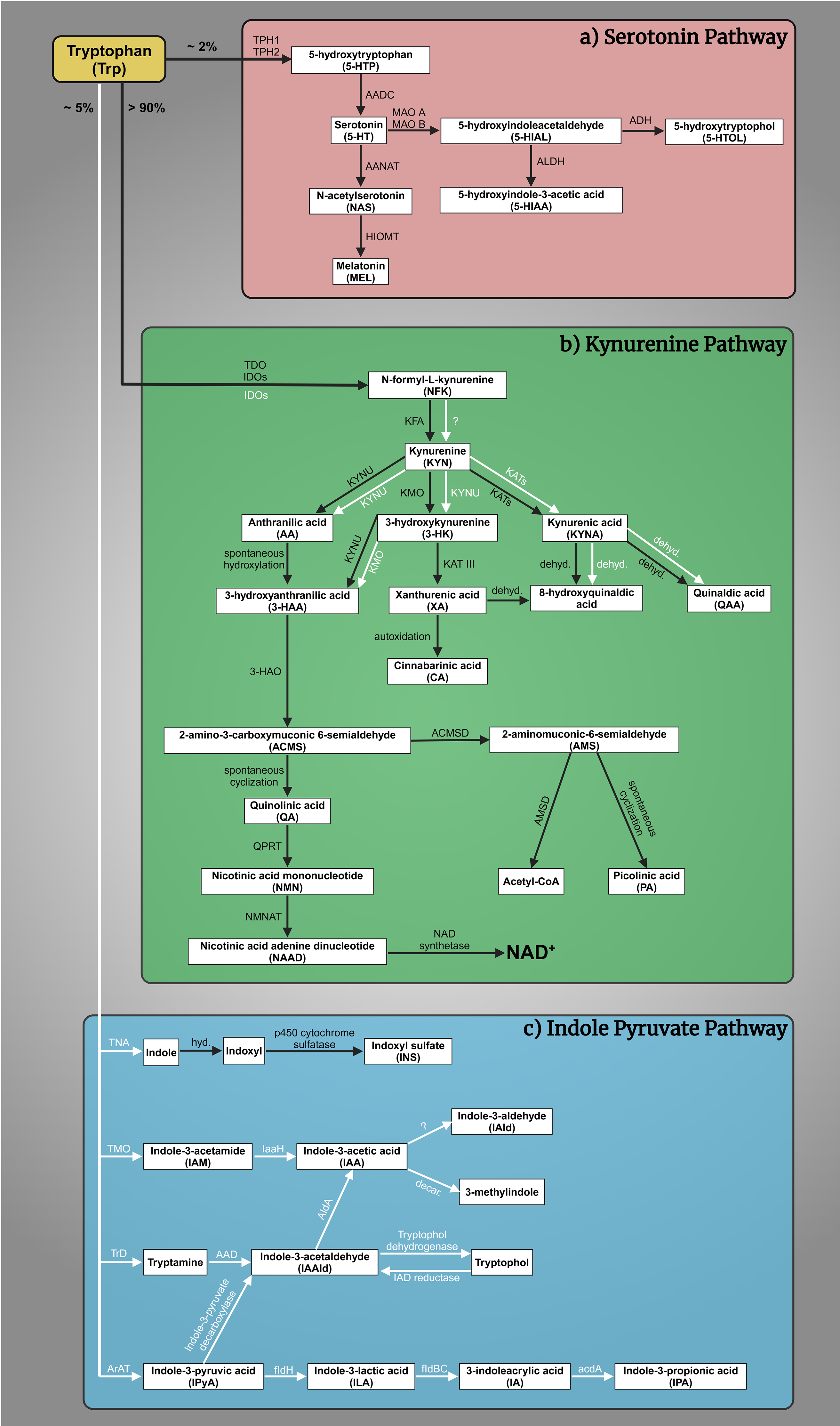

The complex interplay of tryptophan (Trp)-kynurenine (KYN) and 5-HT metabolism is crucial for comprehending the pathogenesis of mental illnesses [59, 60]. The Trp-KYN metabolic system, closely associated with 5-HT metabolism, plays a pivotal role in the production of prooxidants and antioxidants, regulation of the immune system, and the balance between neurotoxicity and neuroprotection [61, 62]. Approximately 2% of L-Trp undergoes metabolism through the 5-HT metabolic pathway; however, over 90% of Trp is catabolized through the KYN route, which safely to say that it governs Trp metabolism (Fig. 1a,b, Ref. [63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83]) [84]. Various factors, including stress, inflammation, and the gut microbiome, influence this system [85, 86, 87, 88]. Dysregulation of the KYN route has been linked to mental health conditions such as MDD, SCZ, and AD [89]. About 5% of dietary Trp is converted by gut bacteria, like E. coli and Clostridium sporogenes, into indole and its derivatives (e.g., indole-3-acetic acid, indoxyl sulfate) (Fig. 1c) [63, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98]. Disruptions in this pathway are linked to gastrointestinal and liver conditions (e.g., colorectal cancer, irritable bowel syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy) and affect brain neurotransmitters and communication via the vagus nerve [64, 95, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109]. The gut microbial indole pathway is increasingly recognized for its role in mental health disorders like depression, anxiety, autism, SCZ, and AD [103, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Tryptophan (Trp) metabolism. (a) The serotonin (5-HT) pathway: A fraction exceeding 2% of L-Trp is metabolized within the 5-HT pathway. The rate-limiting enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase 1 and 2 (TPH1, TPH2) converts Trp to 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), which is then decarboxylated by aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) to 5-HT. 5-HT is oxidized by monoamine oxidase A and B (MAO A, MAO B) in different tissues to 5-hydroxyindoleacetaldehyde (5-HIAL), which is subsequently further oxidized to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) or reduced to 5-hydroxytryptophol (5-HTOL) by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). 5-HIAA is the main metabolite and a marker of serotonergic activity, whereas 5-HTOL is a minor pathway of 5-HT degradation [65]. On the other hand, 5-HT synthetizes melatonin (MEL, N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine). First, 5-HT is converted into N-acetylserotonin (NAS) by arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT), then hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT) transform MEL [66, 67, 68, 69]. (b) The kynurenine (KYN) pathway: More than 90% of Trp enters the KYN pathway, which produces a variety of biomolecules. The primary metabolites include N-formyl-L-kynurenine (NFK), KYN, kynurenic acid (KYNA), anthranilic acid (AA), 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK), xanthurenic acid (XA), 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA), quinolinic acid (QA), picolinic acid (PA), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+). These metabolites are produced through the catalytic actions of various enzymes, namely tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases (IDOs), kynurenine formamidase (KFA), kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO), kynurenine aminotransferases (KATs), kynureninase (KYNU), 3-hydroxyanthranilate oxidase (3-HAO), quinolinate phosphoribosyl transferase (QPRT) [70], nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT) [71], NAD synthetase [72], amino-

However, the understanding of the interplay between Trp-KYN, 5-HT, and indole metabolism in the pathogenesis of mental illnesses remains limited. Kynurenine aminotransferases (KATs) are members of the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzyme family involved in the KYN metabolic pathway. The KYN metabolism is responsible for the conversion of L-KYN to kynurenic acid (KYNA), an antioxidant and neuroprotective metabolite with implications for various central nervous system (CNS) diseases [73, 117, 118]. Among the KAT enzymes, kynurenine/alpha-aminoadipate aminotransferase (KAT/AadAT, aka KAT II) is a mitochondrial enzyme encoded in the gene aadat (kat2) [119]. KAT II is considered to play the most important role among the four isozymes in the cellular environment due to its highest enzymatic activity close to the physiological pH. Thus, KAT II plays a prominent role in KYNA production in the human brain and is considered a crucial target for managing CNS disorders [120].

Preclinical research has significantly contributed to our understanding of mental illnesses by elucidating the underlying pathomechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets [121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129]. Researchers have employed preclinical animal models to examine the causes and effects of mental disorders, thereby attaining a comprehensive understanding of their underlying pathology [130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137]. In vitro models, such as cell cultures and organoids, have facilitated the investigation of complex molecular pathways linked to mental disorders [138, 139, 140, 141]. Animal models, along with other in vivo models, have been instrumental in studying the behavioral, cognitive, and physiological dimensions of mental disorders [142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148]. These models allow researchers to simulate disease conditions, assess symptomatology, and evaluate the efficacy of potential interventions [148, 149]. Transgenic animals are vital in biomedical research, enabling the replication of human conditions through gene deletion or the introduction of altered genes into their genome [150]. These animals offer indispensable insights into human diseases, facilitating the exploration of disease mechanisms, experimentation with potential treatments, and assessment of therapeutic effectiveness [151, 152, 153, 154, 155]. Moreover, they offer crucial insights into changes in structure and imaging techniques in clinical cases [156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175]. Preclinical and clinical research collaboratively contribute to innovative therapeutics and personalized medicine [176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182].

This study involved manipulating the gene kat2 in mice to create a knockout (kat2-/-) model, allowing us to observe the behavioral consequences of KAT II deficiency. By focusing on negative valence in emotional domain, memory acquisition, and motor function, we aimed to gain insights into the role of KAT II in these specific behavioral domains in young adult kat2-/- mice. Furthermore, we assess the levels of Trp and its metabolites in three distinct metabolic pathways in both plasma and urine samples, the enzyme activities of Trp metabolism, and the oxidative stress and excitotoxicity indices of KYN metabolites, with the aim of elucidating the Trp metabolic profiles that underlie the behavioral phenotype. This research contributes to our understanding of the genetic factors influencing behaviors related to emotional valence, memory, and motor function and Trp catabolism.

CRISPR/Cas9 was applied on C57BL/6N and CD1 (ICR; Institute for Cancer Reseach) mice to generate knockout kat2-/- mice, and Taqman allelic discrimination was used to prove that the gene had been deleted. The emotional domain, including depression-like and anxiety-like behaviors, was evaluated with the modified forced swim test (FST), tail suspension test (TST), elevated plus maze (EPM) test, open field (OF) test, and light dark box (LDB) test; the cognitive domain was evaluated with the passive avoidance test (PAT); and the motor domain was evaluated with the OF test. Furthermore, the levels of Trp and its major metabolites, as well as enzyme activities in plasma and urine samples, were determined, and oxidative stress and excitotoxicity indices were calculated.

Animal experiments were conducted humanely in accordance with the Regulations for Animal Experiments of Kyushu University and the Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions governed by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Experiment Committees of Kyushu University (A29-338-1 (2018), A19-090-1 (2019)). The Department of Nature Conservation of the Ministry of Agriculture has authorized us to use genetically modified organisms in a closed system of the second security isolation level (TMF/43-20/2015). The import of genetically modified animals has been approved by the Department of Biodiversity and Gene Conservation of the Ministry of Agriculture (BGMF/37-5/2020). In accordance with the guidelines of the 8th Edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the Use of Animals in Research of the International Association for the Study of Pain, and the directive of the European Economic Community (2010/63/EU), the experiments conducted in this study received ethical approval from two committees. The Scientific Ethics Committee for Animal Research of the Protection of Animals Advisory Board (XI./95/2020, CS/I01/170-4/2022) and the Committee of Animal Research at the University of Szeged (I-74-10/2019, I-74-1/2022) both approved the experiments. Furthermore, Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes provides guidance for the ethical evaluation of animal use proposals. The directive allows individual institutions to make determinations based on the recommendations of their ethical review committees. These ethical guidelines and regulations ensure that the experiments conducted on animals adhere to the highest standards of animal welfare and scientific integrity. The approval from the Scientific Ethics Committee for Animal Research of the Protection of Animals Advisory Board and the Committee of Animal Research at the University of Szeged demonstrates that the study was conducted in compliance with these ethical principles and regulations.

C57BL/6N and CD1 (ICR) mice were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan) and Charles River Laboratories International, Inc. (Yokohama, Japan), respectively, in order to generate kat2-/- mice utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9 technique. After genetic modifications, breeding, and transport from Japan to Hungary, the animals were housed in groups of 4–5 in polycarbonate cages (530 cm2 floor space) under pathogen-free conditions in the Animal House of the Department of Neurology, University of Szeged, maintained at 24

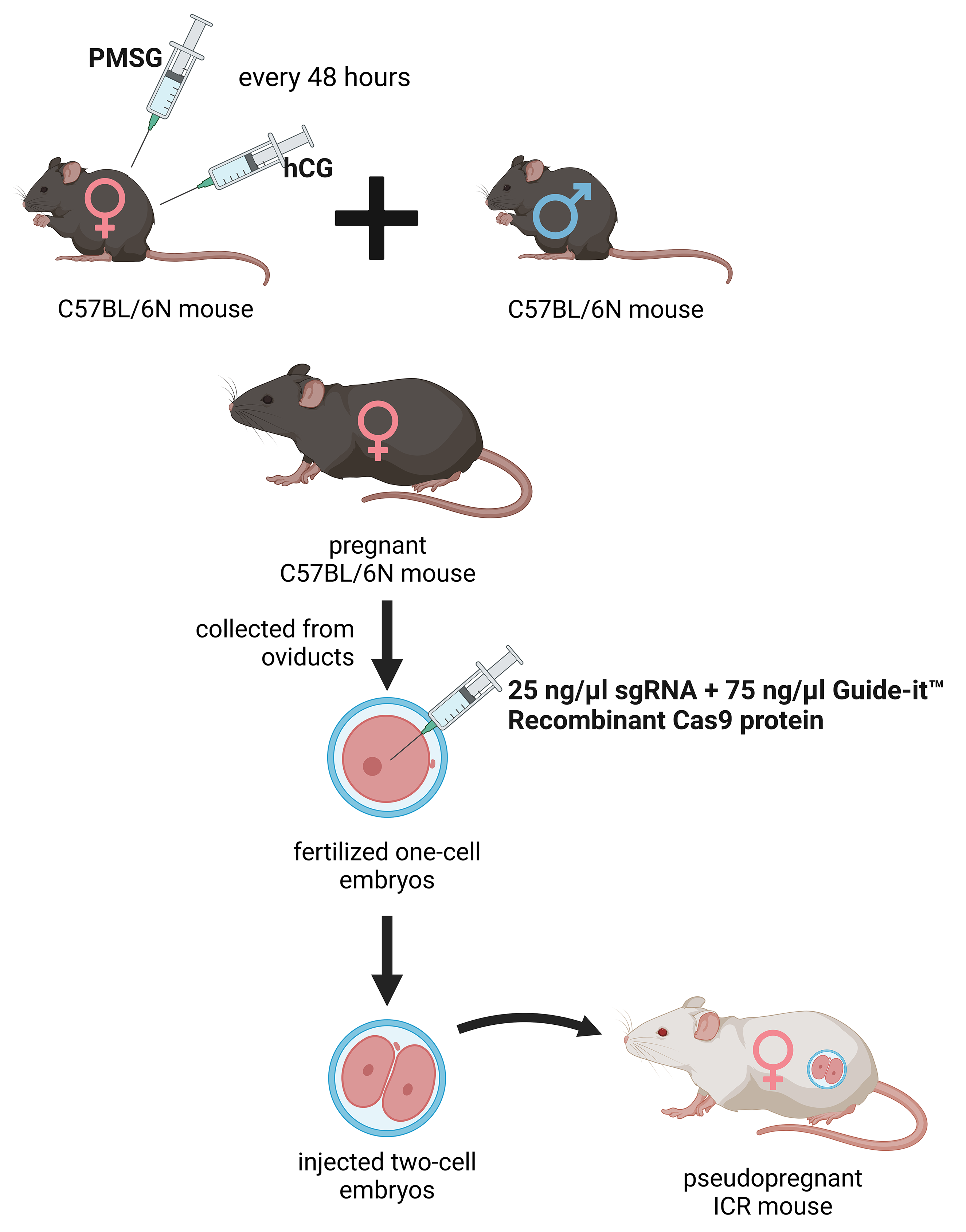

The deletion was introduced into the KATs gene using the CRISPR/Cas9 method. The single guide RNAs (sgRNA) were selected using the CRISPRdirect software [183]. Artificially synthesized sgRNA were purchased from FASMAC (Atsugi, Japan). The 8–12 weeks old female C57BL/6N mice were injected with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) with a 48-h interval, and mated with 8–20 weeks old male C57BL/6N mice. The fertilized one-cell embryos were collected from the oviducts. Then, 25 ng/µL of the sgRNA and 75 ng/µL Guide-it™ Recombinant Cas9 protein (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan) were injected into the cytoplasm of these one-cell-stage embryos. The injected two-cell embryos were then transferred into pseudopregnant ICR mice (Fig. 2) anesthetized with a combination anesthetic (M/M/B: 0.3/4/5) [184] prepared with 0.3 mg/ kg of medetomidine, 4.0 mg/kg of midazolam, and 5.0 mg/kg of butorphanol by intraperitoneal injection.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Generation of the knockout kat2-/- mice. Female C57BL/6N mice were treated with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) with a 48-hour interval between administrations, then mated with male C57BL/6N mice. From the oviducts, fertilized one-cell embryos were collected and injected with single guide RNA (sgRNA) and Guide-itTM Recombinant Cas9 protein. At the two-cell stage, the embryos were transferred into pseudopregnant Institute for Cancer Research (ICR) mice. PMSG, pregnant mare serum gonadotropin; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; sgRNA, single guide RNA. The figure was created with Scientific Image and Illustration Software Biorender.

The kat2-/- mouse line expresses a carboxy-terminal truncated polypeptide consisting of the first 47 amino acids of the intact KAT II with a 2-nucleotide deletion (CCDS nucleotide sequence 32–33) in the mRNA.

Genomic DNA of tails collected from mice was extracted using NucleoSpin Tissue (MACHEREY-NAGEL GmbH&Co, KG, Düren, Germany). Each targeted fragment around the sgRNA targeting site from the extracted genomic DNA as a part of the KATs genes was amplified with TAKARA Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) and the 1st primers pair and subsequently with 2nd primers pair (Table 1). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was purified with a Fast Gene Gel/PCR Extraction Kit (Nippon Genetics Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and Monarch Gel Extraction Kit (NEW ENGLAND BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). Then, the PCR products were sequenced with M-KAT II_2nd_R (Table 1).

| Name of sgRNA | Sequence | ||

| M-KAT II-2 | GTTCCTCACTGCAACGAGCCguuuuagagcuagaaauagcaaguuaaaaaaggcuaguccguuaucaacuugaaaaaguggcacggacucggugcuuuu | ||

| Name of primer | Sequence | ||

| M-KAT II_1st_F | CCCTCTGTGGATGGACTTTG | ||

| M-KAT II_1st_R | TTGAAAGATGTGCCTCATGC | ||

| M-KAT II_2nd_F | GGATGGACTTTGTCCCTTCT | ||

| M-KAT II_2nd_R | ATGTGCCTCATGCTTGGCCC | ||

| Name of KAT gene | Transcript ID | CCDS | CCDS Nucleotide Sequence |

| Aadat-201 | ENSMUST00000079472.4 | CCDS22320 | 32–33 (2 nucleotide deletion) |

sgRNA, single guide RNA; KAT, kynurenine aminotransferase; KAT II, aminoadipate aminotransferase; CCDS, Consensus Coding Sequence.

For Western blotting, tissue extracts from the liver (20 mg) of the knockout and wild-type (WT) mice were prepared by the Total Protein Extraction Kit for Animal Cultured Cells and Tissues (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the tissue extracts were passed through Protein G HP SpinTrapTM (Cytiva, Buckinghamshire, UK) to remove immunoglobulin G. 14 µL of each sample were mixed with 7 µL of SDS Blue Loading Buffer (New England BioLabs Inc.) and separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Subsequently, the protein was transferred to the membranes. The membranes were blocked and incubated with anti-human KAT II rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:500, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at room temperature for 2 h, followed by combination with alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) FC antibody (1:10,000, Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 2 h, followed by visualization of dystrophin and utrophin using Western Blue® Stabilized Substrate for Alkaline Phosphatase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The Multicolor Protein Ladder (10–315 kDa) from Nippon Gene Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) was used as a molecular weight marker for western blotting, allowing visualization and size estimation of target proteins.

The 8–48 weeks old male and female mice mated in August 2023 and became pregnant about three to four weeks later. The RIKEN (The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research) modified SHIRPA (SmithKline Beecham, Harwell, Imperial College, Royal London Hospital, phenotype assessment) test was conducted to ascertain the comprehensive phenotypic traits of the mutant rodents. The assessment included the evaluation of diverse behaviors and physical attributes such as motion, bowel movements, urination, locomotor activity, startle response, tactile escape, pinna reflex, trunk curling, limb grasping, contact-righting reflex, grip strength, wire maneuver test, corneal reflex, toe pinching, and overall appearance. The animals were also monitored for vocalization, aggression, head bobbing, jumping, circling, retropulsion, grooming, and tail-wagging [185, 186]. The experiment was captured on video using a camera (Basler ace Classic acA1300 -60gm, Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany) and software (EthoVision XT14, Noldus Information Technology BV, Wageningen, the Netherlands).

The 8–48 weeks old male and female mice mated between April 2021 and April 2022 and became pregnant approximately three to four weeks later. 8-week-old male C57BL/6N and kat2-/- mice (n = 10–13) were tested. In order to make the results comparable, all behavioral experiments were performed between 8 a.m. and 12 p.m. The animals were transferred to the laboratory, where the measurements were made, one hour before the start of the experiment, thus they had time to acclimatize to the environmental conditions.

The modified FST was performed as reported previously. The mice were placed individually in a glass cylinder of 12 cm in diameter and 30 cm in height. Water (25

The mice were placed in a 28

The animals were positioned in a plus-shaped apparatus with four arms measuring 35

The LDB apparatus is comprised of larger illuminated (2/3 of the box) and smaller dark (1/3 of the box) compartments that are connected by a 5

Each mouse was individually placed in a box containing two apparatuses with distinct lighting. The animals began in the bright compartment and had 5 minutes to pass through the 5

A standard table lamp illuminated the center of the 48

Throughout the experiment, the animals’ general physical condition was constantly assessed using a scoring scale, which included body weight, appearance and overall condition, respiration, mobility, and the presence of basic reflexes. Humane endpoints were determined using the scales. If any animal reached the required score for withdrawal from the behavioral assessments, it was euthanized via transcardial perfusion under isoflurane anesthesia, effectively terminating its participation in the evaluation.

The 8–48 weeks old male and female mice mated in August 2023 and became pregnant about three to four weeks later. The urine samples were collected before anesthesia, and were immediately stored at –80°C after the sample collection. For plasma collection, the mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and after exposing their chest, blood samples were taken from the left heart ventricle using a syringe into Eppendorf tubes containing disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate. Plasma was separated by centrifugation (10,300 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C). The supernatant plasma samples were pipetted into new Eppendorf tubes. The samples were stored at –80 °C until use. The animals were perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid for 5 minutes to remove additional organs for later use. Trp and its metabolites were measured in plasma and urine using previously published protocols [198, 199] using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS). Picolinic acid multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) showed a change from 124.0 to 106.0 over 1.21 minutes, with 75 V acting as the declustering potential and 13 V acting as the collision energy. All reagents and chemicals were of analytical or liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry grade. Trp and its metabolites, and their deuterated forms: d4-serotonin, d5-tryptophan, d4-kynurenine, d5-kynurenic acid, d4-xanthurenic acid, d5-5-hydroxyindole-acetic acid, d3-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, d4-picolinic acid, and d3-quinolinic acid were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada). d3-3-hydroxykynurenine was obtained from Buchem B. V. (Apeldoorn, The Netherlands). Acetonitrile (ACN) was provided by Molar Chemicals (Halásztelek, Hungary). Methanol (MeOH) was purchased from LGC Standards (Wesel, Germany). Formic acid (FA) and water were obtained from VWR Chemicals (Monroeville, PA, USA). The UHPLC-MS/MS system consisted of a PerkinElmer Flexar UHPLC system (two FX-10 binary pumps, solvent manager, autosampler and thermostatic oven; all PerkinElmer Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA)), coupled to an AB SCIEX QTRAP 5500 MS/MS triple quadrupole mass spectrometer and controlled by Analyst 1.7.1 software (both AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA).

The enzyme activities of each Trp metabolism were determined by dividing the concentration of the product by the concentration of the substrate.

The oxidative stress index was calculated as the ratios of putative prooxidant metabolite 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) concentrations to the sums of putative antioxidant metabolite concentrations (KYNA, anthranilic acid (AA), and xanthurenic acid (XA)) (Eqn. 1) [200, 201, 202].

The excitotoxicity index is calculated by dividing the concentration of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor agonist quinolinic acid (QA) by that of NMDA receptor antagonist KYNA (Eqn. 2) [203, 204, 205].

We used IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0.0 (IBM SPSS statistics, Chicago, IL, USA) for the statistical analysis. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine the distribution of data. In addition, we used a Q-Q plot to find out if two sets of data come from the same distribution. Our data followed a normal distribution. One-way ANOVA test was used to evaluate the results of the behavioral tests and neurochemical measurements followed by the Tamhane post hoc test. Values p

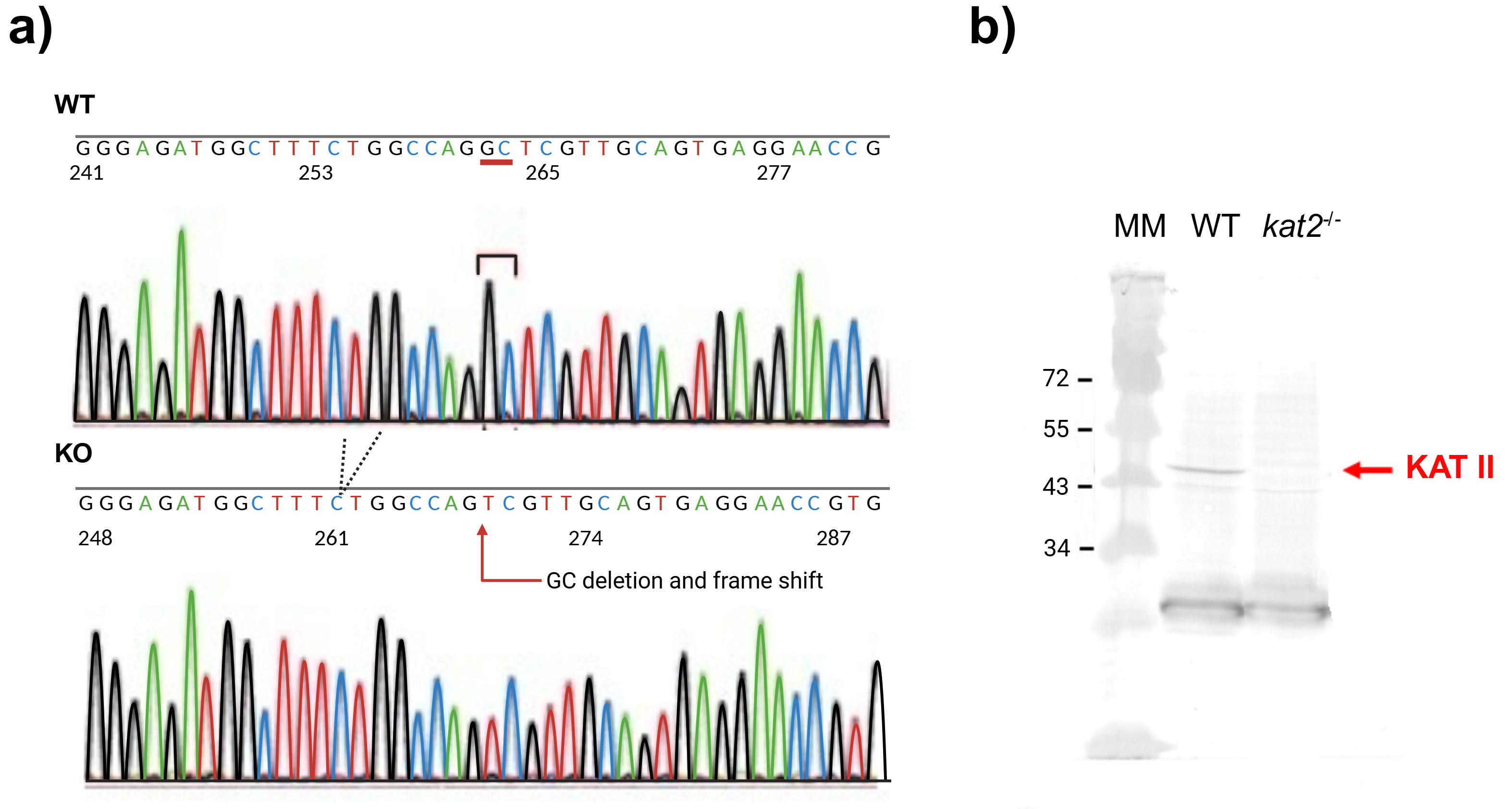

To generate knockout mice of kat2 gene, 25 ng/µL of sgRNA and 75 ng/µL Cas9 protein were injected into the cytoplasm of the one-cell-stage embryos. Sequencing analyses with their founder mice showed that various deletions and/or insertions were introduced in the target sequence. One of the founders was selected and established the homozygous mouse line for further analyses. KAT II knockout mouse line expresses a carboxy-terminal truncated polypeptide consisting of the first 47 amino acids of the intact KAT II with 2 nucleotides deletion (CCDS nucleotide sequence 32–33) in the mRNA. Western blotting with antibodies against KAT II revealed that the band with approximately 50-kDa supposed to be KAT II was not detected in the knockout mice, while it was detected in the wild-type (WT) counterparts (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. DNA sequence and western blot analysis of knockout kat2-/- mouse line. (a) Genomic sequences around the mutation site of knockout kat2-/- mouse strain. (b) Western blot analysis of knockout kat2-/- mouse line. MM: molecular weight marker, WT: wild-type mouse. The figure was created with Scientific Image and Illustration Software Biorender.

We did not detect any significant differences between the knockout mice and their wild-type counterparts.

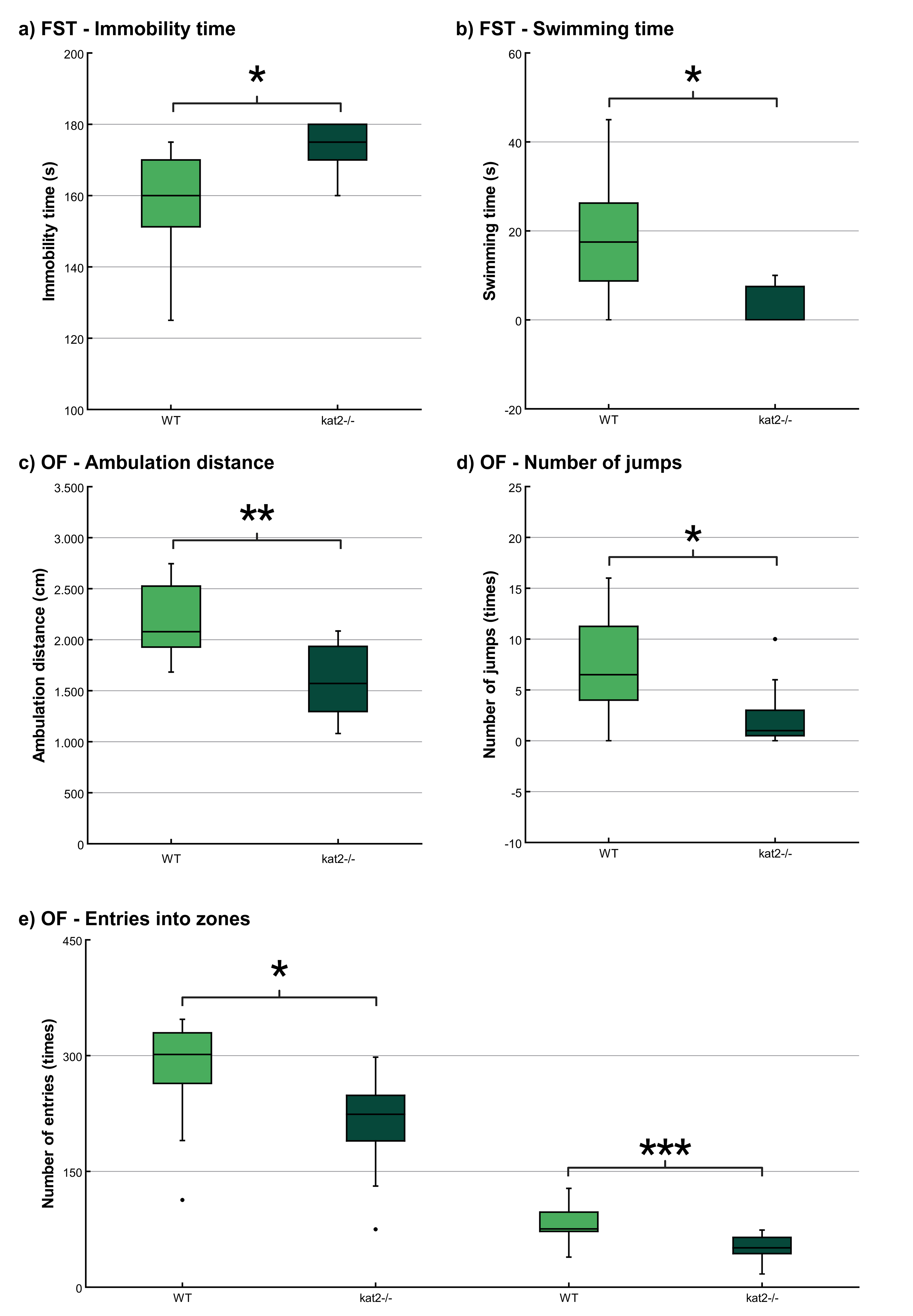

The immobility time was significantly longer and the swimming time was significantly shorter in kat2-/- mice than in WT mice (Fig. 4a,b; Table 2). There were no significant differences in climbing time (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Behavioral tests. (a) Time spent immobile in the modified forced swim test (FST). (b) Time spent swimming in the modified FST. (c) Ambulation distance in the open field (OF) test. (d) Number of jumps in the OF test; and (e) Number of entries into the center and corner zones in the OF test. Wild-type mice (light green); kat2-/- mice (dark green). WT, wild-type; kat2-/-, kynurenine aminotransferase II knockout mice; FST, forced swim test; OF, open field test; •, outliner. Mean

| Test type | Number of animals | Perspectives | Mean | Mean | p-value |

| Modified forced swim test (FST) | WT: n = 12 | Immobility time (s) | 157.73 | 174.09 | 0.022 * |

| kat2-/-: n = 11 | Swimming time (s) | 18.18 | 3.18 | 0.014 * | |

| Climbing time (s) | 4.09 | 1.82 | 0.681 | ||

| Tail suspension test (TST) | WT: n = 10 | Immobility time (s) | 194.50 | 209.58 | 0.625 |

| kat2-/-: n = 13 | |||||

| Passive avoidance test (PAT) | WT: n = 12 kat2-/-: n = 12 | Time spent in the lit box on the training day (s) | 48.33 | 64.67 | 0.979 |

| Time spent in the lit box on the test day (s) | 256.00 | 283.75 | 0.822 | ||

| Elevated plus maze (EPM) test | WT: n = 10 | Time spent in the open arms (s) | 42.90 | 30.64 | 0.500 |

| kat2-/-: n = 11 | |||||

| Light dark box (LDB) test | WT: n = 12 | Time spent in the lit box (s) | 119.00 | 113.91 | 0.957 |

| kat2-/-: n = 11 | |||||

| Open field (OF) test | WT: n = 12 kat2-/-: n = 11 | Number of entries to the center zones (times) | 281.67 | 210.73 | 0.011 * |

| Number of entries to the corner zones (times) | 83.08 | 51.27 | 0.001 *** | ||

| Ambulation distance (cm) | 2191.75 | 1609.27 | 0.002 ** | ||

| Number of jumps (times) | 7.33 | 2.45 | 0.034 * |

*, p

The ambulation distance of the kat2-/- mice was significantly shorter in the first 10-minute timeframe than that of their WT counterparts (Fig. 4c; Table 2). The number of jumps was significantly fewer in the kat2-/- mice than that of their WT counterparts (Fig. 4d; Table 2). There were significantly fewer entries into the center and corner zones compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 4e; Table 2).

There were no statistically significant distinctions observed between the transgenic mice and their WT counterparts in TST, PAT, EPM test, and LDB test (Table 2).

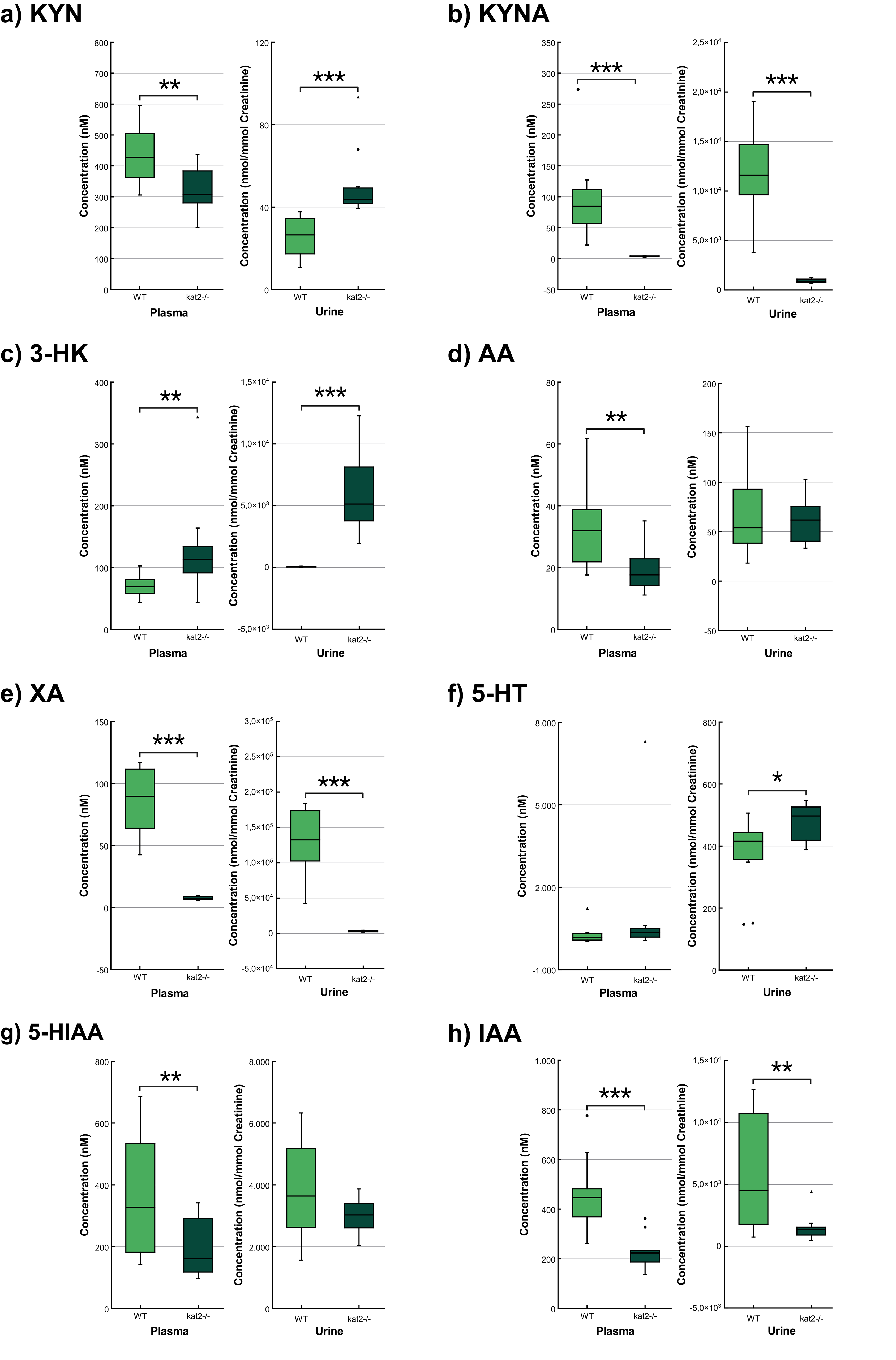

Transgenic mice had significantly lower levels of KYN, KYNA, XA, AA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and higher levels of 3-HK in plasma samples than wild-type mice. In urine samples, KYNA, XA, and IAA were significantly lower, whereas KYN, 3-HK, and 5-HT were significantly higher than those of the wild-type counterparts (Fig. 5; Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Concentration level of tryptophan metabolites in plasma and urine. (a) Kynurenine. (b) Kynurenic acid. (c) 3-hydroxykynurenine. (d) Anthranilic acid. (e) Xanthurenic acid. (f) Serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine. (g) 5-hydroxyanthranilic acid. (h) Indole-3-acetic acid. We marked wild-type mice with light, and kat2-/- mice results with dark green boxes. WT, wild-type; kat2-/-, kynurenine aminotransferase II knockout; 3-HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyanthranilic acid; 5-HT, serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine; AA, anthranilic acid; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; XA, xanthurenic acid; •, outliner;

| Plasma (nM) | Urine (nmol/mmol Creatinine) | |||||

| Mean | p value | Mean | p value | |||

| WT | kat2-/- | WT | kat2-/- | |||

| Tryptophan (Trp) | 40,901.678 | 35,543.573 | 0.532 | 2022.196 | 1972.014 | 0.870 |

| Kynurenine (KYN) | 440.674 | 327.348 | 0.012 ** | 25.238 | 50.883 | |

| Kynurenic acid (KYNA) | 96.960 | 3.654 | 11,783.938 | 920.990 | ||

| Quinaldic acid (QAA) | 6.884 | 5.608 | 0.476 | 14.248 | 12.014 | 0.572 |

| 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) | 70.714 | 130.851 | 0.037 ** | 55.472 | 5986.833 | |

| Xanthurenic acid (XA) | 93.624 | 7.406 | 127,228.662 | 3273.334 | ||

| Anthranilic acid (AA) | 32.655 | 19.335 | 0.012 ** | 69.112 | 60.862 | 0.612 |

| 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) | 22.992 | 20.920 | 0.452 | 1741.538 | 1789.475 | 0.874 |

| Quinolinic acid (QA) | 132.185 | 112.000 | 0.468 | 10,059.485 | 11,718.491 | 0.326 |

| Picolinic acid (PA) | 193.797 | 154.895 | 0.352 | 190.435 | 193.898 | 0.941 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) | 2.790 | 2.708 | 0.901 | 21.742 | 19.297 | 0.419 |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | 277.309 | 1010.379 | 0.316 | 371.974 | 479.383 | 0.027 * |

| 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) | 362.241 | 201.217 | 0.035 ** | 3774.968 | 2969.725 | 0.167 |

| Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | 457.329 | 229.142 | 6030.306 | 1513.400 | 0.009 ** | |

| Indoxyl-sulphate (INS) | 6738.111 | 5404.257 | 0.332 | 400,636.750 | 497,063.585 | 0.267 |

SD, standard deviation; *, p

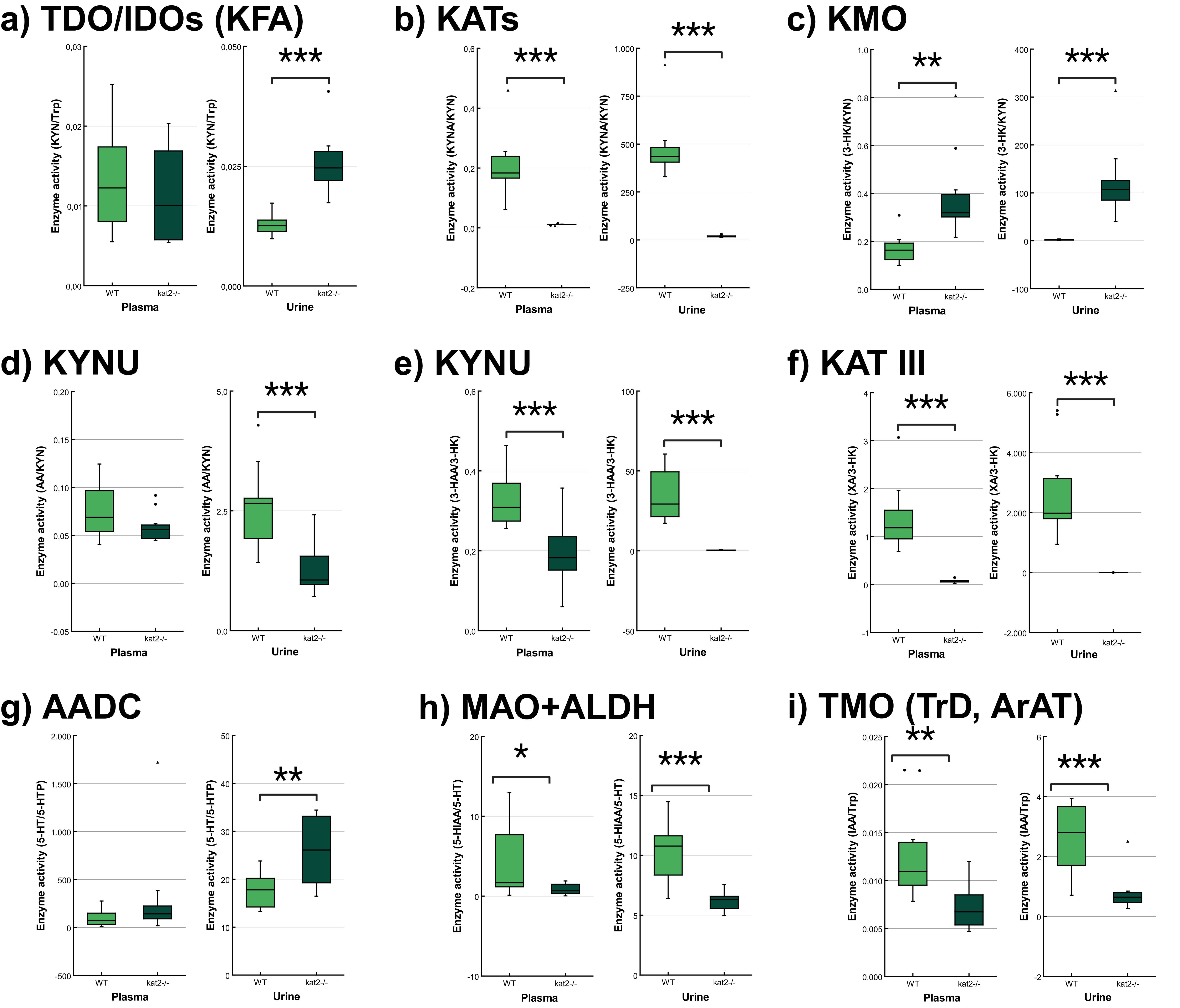

The transgenic mice showed significantly lower KATs, kynureninase (KYNU), KAT III, monoamine oxidase (MAO), aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), and tryptophan-2-monooxygenase (TMO) activities and significantly higher kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO) activity in plasma samples than wild-type mice. In the urine samples, the transgenic mice showed significantly lower KATs, KYNU, KAT III, MAO, ALDH, and TMO activities, and significantly higher tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO)/ indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases (IDOs) (KFA), KMO, and aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) activities compared to the wild-type counterparts (Fig. 6, Table 4).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Tryptophan metabolism’s enzyme activity in plasma and urine. (a) Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase/indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases (kynurenine formamidase). (b) Kynurenine aminotransferases. (c) Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase. (d,e) Kynureninase. (f) Kynurenine aminotransferase III/cysteine conjugate beta-lyase 2. (g) Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase. (h) Monoamine oxidases + aldehyde dehydrogenase. (i) Tryptophan-2-monooxygenase (tryptophan decarboxylase, aromatic amino acid aminotransferase). We marked wild-type mice with light, and kat2-/- mice results with dark green boxes. 3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; 3-HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-HT, serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan; AADC, aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; ArAT, aromatic amino acid aminotransferase; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; IDOs, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases; KAT III, kynurenine aminotransferase III/cysteine conjugate beta-lyase 2; kat2-/-, kynurenine aminotransferase II knockout; KATs, kynurenine aminotransferases; KFA, kynurenine formamidase; KMO, kynurenine 3-monooxygenase; KYNU, kynureninase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; TDO, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase; TMO, tryptophan-2-monooxygenase; TrD, tryptophan decarboxylase; Trp, tryptophan; WT, wild-type; XA, xanthurenic acid; KYN, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; AA, anthranilic acid; •, outliner;

| Enzyme | Product/Substrate | Plasma | Urine | ||||

| Mean | p value | Mean | p value | ||||

| WT | kat2-/- | WT | kat2-/- | ||||

| TDO/IDOs (KFA) | KYN/Trp | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.532 | 0.013 | 0.026 | |

| KATs | KYNA/KYN | 0.205 | 0.011 | 476.464 | 18.937 | ||

| KMO | 3-HK/KYN | 0.168 | 0.386 | 0.002 ** | 2.219 | 122.983 | |

| KYNU | AA/KYN | 0.075 | 0.059 | 0.120 | 2.593 | 1.253 | |

| KYNU | 3-HAA/3-HK | 0.330 | 0.194 | 35.177 | 0.372 | ||

| KAT III | XA/3-HK | 1.374 | 0.070 | 2702.990 | 0.629 | ||

| 3-HAO | QA/3-HAA | 5.l771 | 5.486 | 0.804 | 6.240 | 6.856 | 0.532 |

| 3-HAO + ACMSD | PA/3-HAA | 8.797 | 7.681 | 0.592 | 0.123 | 0.119 | 0.906 |

| TPHs | 5-HTP/Trp | 0.128 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.410 | ||

| AADC | 5-HT/5-HTP | 97.585 | 307.233 | 0.216 | 17.608 | 25.997 | 0.004 ** |

| MAOs + ALDH | 5-HIAA/5-HT | 4.217 | 0.905 | 0.045 * | 10.209 | 6.181 | |

| TMO (TrD, ArAT) | IAA/Trp | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.005 ** | 2.570 | 0.786 | |

| TNA | INS/Trp | 0.208 | 0.170 | 0.555 | 215.671 | 248.916 | 0.428 |

*, p

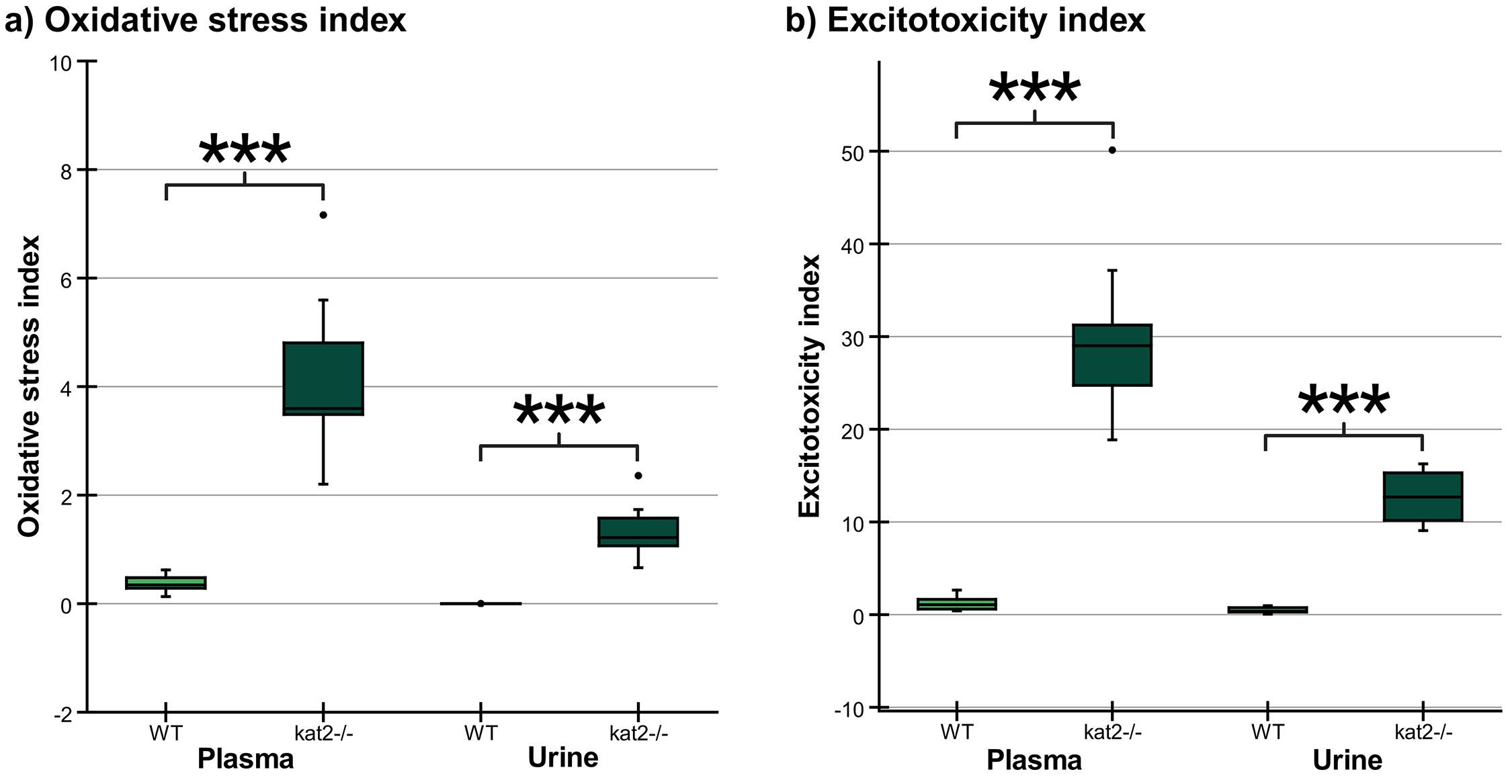

Transgenic mice had higher levels of oxidative stress and excitotoxicity in both plasma and urine than wild-type mice (Fig. 7, Table 5).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Oxidative stress and excitotoxicity indices in plasma and urine. (a) The oxidative stress indices in kat2-/- mice’s plasma and urine samples are significantly higher than those in the wild-type. (b) The excitotoxicity indices in kat2-/- mice’s plasma and urine samples are significantly higher than those in the wild-type. We marked wild-type with light, and kat2-/- mice results with dark green boxes. WT, wild-type; kat2-/-, kynurenine aminotransferase II knockout; •, outliner. Mean

| Oxidative stress index | ||||||

| Oxidant/antioxidant metabolites | Plasma (nM) | Urine (nmol/mmol Creatinine) | ||||

| Mean | p value | Mean | p value | |||

| WT | kat2-/- | WT | kat2-/- | |||

| 3-HK/KYNA+AA+XA | 0.378 | 4.090 | 0.085 | 1.352 | ||

| Excitotoxicity index | ||||||

| NMDA | Plasma (nM) | Urine (nmol/mmol Creatinine) | ||||

| agonist/antagonist | Mean | p value | Mean | p value | ||

| metabolites | WT | kat2-/- | WT | kat2-/- | ||

| QA/KYNA | 1.648 | 30.514 | 0.884 | 13.092 | ||

***, p

Dysregulation of 5-HT metabolism is a key factor in mental symptom development, with attention focused on its imbalance with neurotransmitters like dopamine, norepinephrine, and biosystems such as substance P [206, 207, 208, 209, 210]. Alterations in 5-HT precursor Trp metabolism are noted in mental illnesses, but their connection with the Trp-KYN metabolic system remains poorly understood [211, 212, 213]. Growing evidence suggests that the gut microbial indole pyruvate pathway can influence the microbiome-gut-brain axis, implying that intestinal Trp metabolism may play a significant role in psychological health. The microbiome-gut-brain axis is responsible for regulating mood, cognition, stress response, and behavior [101]. As a result, the gut-microbial indole pyruvate pathway can influence the microbiome-gut-brain axis by controlling the production and availability of neurotransmitters, hormones, cytokines, and bioactive metabolites involved in neuropsychiatric conditions.

KATs are cytosolic and mitochondrial aminotransferases that convert KYN to KYNA [74, 214, 215, 216]. The mitochondrial isoform KAT II exclusively influences cellular bioenergetics due to its exclusive location in the mitochondria [117, 205]. CRISPR/Cas9 was employed to knock out the kat2 gene, creating kat2-/- mice. This study aimed to examine the negative emotional aspects and evaluate any behavioral alterations caused by the knockout of the kat2 gene in young adults aged 8 weeks. kat2-/- mice, studied in 8-week-old adults, induce a unique depression-like phenotype marked by increased immobility in FST, likely linked to serotonergic pathways. TST did not show significant differences, possibly due to FST conditioning. The results that the PAT did not show a significant difference may suggest that depression-like behavior is more likely to be related to depression-like behavior caused by despair experiences than to aversive-conditioned memory. Anxiety-like behaviors (EPM and LDB) showed no difference, but the OF test revealed shorter ambulation distance, fewer jumping counts, and fewer entries into both center field and corners, suggesting a la belle indifference-like trait. kat2-/- mice exhibited despair-based depression-like behavior without anxiety-like traits, demonstrating motor deficits. The study suggests the kat2 gene deletion potentially leads to a PTSD-like phenotype, including a la belle indifference trait, indicative of complex PTSD with emotional dysregulation [217, 218, 219].

The gene knockout significantly alters Trp metabolism in both 5-HT, KYN, and indole pathways in plasma and urine. A major 5-HT metabolite, 5-HIAA, is markedly reduced, possibly explained by scarce mitochondrial enzyme activity. Lower levels of KYNA and antioxidant KYNs indicate decreased production in peripheral tissues of kat2-/- mice. Conversely, 3-HK is significantly elevated. The levels of the gut microbial metabolite IAA, an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory molecule, were reduced. The disruption of the KAT II gene may lead to a reduction in the levels of IAA in the indole pathway of the gut microbiota, as the enzyme plays a role in controlling Trp metabolism. KAT II has an impact on the availability of Trp and its subsequent metabolic pathways, including the production of IAA. In the absence of KAT II, the Trp metabolite balance may shift, resulting in less IAA synthesis by gut bacteria. This change may disrupt the gut-brain axis and have an impact on intestinal health, as IAA is required for immune response regulation, intestinal barrier integrity, and modulating the production of other indole derivatives. Furthermore, gene knockout affects enzyme activity, puts organisms under oxidative stress, imposes high excitotoxicity and neurotoxicity, and alters immune responses. The study demonstrates that the deletion of the kat2 gene leads to a specific set of characteristics, including behavior similar to depression, impaired motor function, decreased levels of KYNA, and a change in the way Trp is metabolized towards the KYN pathway. This phenotype exhibits similarities to PTSD in humans, potentially indicating the presence of complex PTSD due to the observed belle indifference-like trait.

The amygdala encodes and stores fear memory after receiving sensory input from the thalamus, which also consolidates and retrieves memories from the initial stimuli that induce fear [220, 221, 222]. Fear memory is associated with the release of stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol, which stimulate the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [46, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227]. This study does not show evidence of fear memory acquisition. In contrast, the encoding and storage of memories associated with despair occur in the prefrontal cortex, which plays a crucial role in the cognitive and emotional processing of negative experiences [228]. Recalling distressing memories, triggered by cues linked to the initial negative encounter, results in the disruption of 5-HT, norepinephrine, and dopamine regulation. Although fear and despair memories have similarities in terms of encoding and retrieval processes, they are associated with different brain regions, neurotransmitters, and neural circuits [229, 230].

Furthermore, despair memory and despair experience differ. The latter pertains to an instantaneous, personal feeling of despair or hopelessness, prompted by present circumstances, as opposed to a remembrance of past experiences [231]. Despair memory involves the consolidation and retrieval of long-term memories, influenced by stress and emotion [232]. In contrast, a despair experience entails immediate emotional responses influenced by factors like cognitive assessments, environmental cues, and physiological states [233]. Additionally, la belle indifference arises from a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional symptom processing, including altered emotional processing in the amygdala and insula, changed self-awareness in the medial prefrontal cortex, and adjusted activity in the somatosensory cortex influenced by dopamine and 5-HT [234]. Thus, kat2-/- mice show more despair-based depression-like behavior involving a change in 5-HT metabolism.

Approximately 60% of individuals on antidepressants, including SSRIs, for two months experience a 50% reduction in depression symptoms [235]. The observation aligns with the monoamine hypothesis, suggesting depression’s pathogenesis is linked to low 5-HT levels. Transgenic models are used to study 5-HT dysmetabolism behaviors, with a focus on the Tph gene, which encodes tryptophan hydroxylase, a key enzyme in 5-HT synthesis [236]. Preclinical studies found normal 5-HT levels with no behavioral changes in Tph1-/- mice, while Tph2-/- mice’s behaviors are inconclusive [237, 238]. The knock-in mice of the TPH2 variant (R439H) showed depression-like behavior in TST [239]. Intriguingly, Tph1/Tph2-/- mice exhibited contrasting behaviors: antidepressant-like in FST, depressive in TST, and anxious in the MB test, accompanied by low 5-HT levels in the brain and periphery [240]. 5-HT1A receptor knockout (5-HT1AR-/-) mice display heightened fear memory to contextual cues, suggesting a role for 5-HT receptors in PTSD-like phenotype [241]. 5-HT 2C receptor knockout 5-HT2CR-/- mice attenuates fear responses in contextual or cued but not compound context-cue fear conditioning [242]. Knockout of the 5-HTT gene in mice (5-HTT-/-) leads to impaired stress response, fear extinction, and abnormal corticolimbic structure [243].

Over 90% of 5-HT precursor Trp undergoes catabolism in the Trp-KYN metabolic system, generating a variety of bioactive molecules including prooxidants, antioxidants, inflammation suppressants, neurotoxins, neuroprotectants, and/or immunomodulators [244]. Growing evidence indicates disrupted KYN metabolism in MDD, bipolar disorder, and SCZ [245, 246, 247]. Earlier, KYN metabolites were suggested to be either neuroprotective or neurotoxic [248]. However, increasing evidence suggests that KYN metabolites exhibit versatile actions, potentially influenced by concentrations and the microenvironment [249]. Previously, cognitive and motor functions of 129/SvEv kat2-/- mice were reported. These transgenic mice exhibited transient hyperlocomotive activity and motor coordination issues at postnatal day 21. However, from postnatal day 17 to 26, they demonstrated notable improvements in cognitive functions, particularly in object exploration and recognition tasks in PAT and T-maze tests [250, 251].

Other biosystems play an important role in the pathogenesis of PTSD, including dopaminergic and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic, and cannabinoid systems. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) degrades dopamine. COMT-/- mice exhibited an increased response to repeated stress exposures [252]. Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) synthesizes GABA [253]. GAD6-/- mice shows increased generalized fear and impaired extinction of cued fear [254]. GABA receptor subunit B1a knockout GABAB1a-/- mice showed a generalization of conditioned fear to nonconditioned stimuli [255]. Cannabinoid 1 receptor (CBIR) knockout CB1R-/- mice showed an increased response to repeated stress exposures [256].

The potential of this study is to characterize the negative valence of emotional domain in context with aversive-conditioned memory and despair experience in the young adult (8 week) of kat2-/- mice. The findings complement the previous studies of kat2-/- mice in the early adolescence (2 and 1/2 to 4 weeks) to reveal that, toward adulthood, there is a dynamic change in emotional susceptibility and motor function derived from despair experience in adjunct to Trp metabolism. Furthermore, urinary Trp metabolite levels were generally consistent with plasma levels, suggesting that urinary samples may serve as non-invasive biomarkers for Trp metabolism status. This study may shed new light on the deletion of the kat2 gene as a new avenue toward understanding a KYN metabolite as an oxidative stressor, a potential barrier between aversive-conditioned memory and despair experience, a distinction between memory and experience, their mechanism for the formation of intrusive memories, and the pathogenesis of PTSD. The ultimate goal is to probe a potential interventionable stage in age where the progression of PTSD is preventable and to identify targets which drugs or psychotherapy can relieve symptoms of PTSD. The greatest challenge lies in preclinical animal models that are difficult to simulate and interpolate to mental illnesses to achieve high model validity.

This research on transgenic mice offers great potential for future studies. By examining the link between behavioral changes and variations in Trp and its metabolites in plasma and urine, scientists can gain insights into Trp metabolism’s role in emotional and cognitive functions. Additionally, assessing enzyme activities related to Trp metabolism and their effects on oxidative stress and neurochemical imbalances may uncover mechanisms behind observed behavioral differences. This thorough approach could reveal causal or parallel relationships, shedding light on how altered Trp metabolism impacts neurochemical imbalances and oxidative stress, contributing to conditions like depression and PTSD. The results may help identify specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets, opening new pathways for precision medicine and more effective treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders. The study’s findings could lead to the development of customized therapies, enhancing mental health by focusing on unique metabolic pathways and genetic factors. This research highlights the importance of combining metabolic, behavioral, and genetic data to deepen our understanding of complex psychiatric disorders [257].

This study suggests that behavioral sampling in rodents can distinguish between fear-, memory-, and despair-based depression-like behavior associated with Trp metabolism gene deletions. Further research incorporating neurochemical, neurogenetic, and electrophysiological biomarkers may reinforce this finding. Additionally, using inhibitory RNA or antisense RNA on neurotransmitters in specific brain regions could elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying emotional behaviors. Preclinical research drives advances in clinical applications like precision medicine and drug discovery [258, 259, 260]. The study acknowledges weaknesses, noting distinctions in interpreting animal behaviors and drug responses compared to humans. Recent perspectives consider depression-like behavior in FST as related to different stages of stress-coping behaviors [261]. Consequently, Translational research has limitations that necessitate careful interpretation [262, 263, 264]. This study employed animal models with standard protocols, focusing on the negative valence of the emotional domain and motor function in kat2-/- mice. Further exploration with diverse models such as sucrose preference tests, fear condition tests, and those using non-standard protocols is crucial for a more accurate characterization of kat2-/- mouse behavior. Notably, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, emphasizes four symptom clusters in PTSD diagnosis [265, 266, 267]. The transgenic mice in this study did not exhibit signs related to negative cognitions and mood, and arousal state and reactivity were not investigated.

Psychiatric disorders, including PTSD, have a significant impact on memory and emotion, and disruptions in 5-HT metabolism have been associated with these disorders. The Trp-KYN metabolic pathway plays a crucial role in metabolizing over 95% of the 5-HT precursor Trp. To investigate the effects of gene deletion on negative valence in emotion, memory, and motor function, transgenic kat2-/- mice were created and compared to WT mice. The kat2-/- mice exhibited depression-like behavior characterized by despair experiences, diminished motor functions, and la belle indifference-like characteristics without anxiety-like behavior. This study provides insights into the negative valence of the emotional domain in the context of aversive-conditioned memory and despair experiences in 8-week-old kat2-/- mice. Understanding the complex interplay between memory, emotion, and genetic factors is crucial for advancing our knowledge of psychiatric disorders [268, 269]. By elucidating the specific effects of gene deletion on negative valence and related behaviors, this research contributes to our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and potential interventions.

During preparation for this work, the authors used QuillBot for gingrammar and style checks in the main text. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; 3-HAO, 3-hydroxyanthranilate oxidase; 3-HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-HT, serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan; AA, anthranilic acid; AADC, aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase; ACMSD, amino-

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, ÁS, JT, EO, LV, and MT; methodology, ÁS, ZG, ES, MS, DM, KT, KO, HI, SY, and MT; software, ÁS, ES, MS, KO; validation, ÁS, ZG, ES, MS, KT, KO, and MT; formal analysis, ÁS, ZG, ES, MS, KO, and MT; investigation, ÁS, ZG, ES, MS, DM, KT, KO, and MT; resources, ÁS and EO; data curation, ÁS, ZG, ES, MS, KO; writing—original draft preparation, ÁS, ZG, MT; writing—review and editing, ÁS, ZG, ES, MS, DM, JT, EO, LV, and MT; visualization, ÁS, KO; supervision, JT, EO, LV, and MT; project administration, JT, EO, and LV; funding acquisition, JT, EO, LV, and MT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Regulations for Animal Experiments of Kyushu University, the Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions governed by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Experiment Committees of Kyushu University (A29-338-1 (2018), A19-090-1 (2019)), and approved by the National Food Chain Safety Office (XI./95/2020, CS/I01/170-4/2022) and the Committee of Animal Research at the University of Szeged (I-74-10/2019, I-74-1/2022).

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Nikolett Nánási for her chemical analysis. The figures are created with biorender.com.

This work was supported by the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office—NKFIH K138125, SZTE SZAOK-KKA No:2022/5S729, the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Network, and JSPS Joint Research Projects under Bilateral Programs Grant Number JPJSBP120203803.

Given his role as a Guest Editor, Masaru Tanaka had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Thomas Heinbockel. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.