1 Department of Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou Hospital of Zhengzhou University, 450000 Zhengzhou, Henan, China

Abstract

Endometrial Cancer (EC) is one of the most common gynecological malignancies, ranking first in developed countries and regions. The occurrence and development of EC is closely associated with genetic mutations. TP53 mutation, in particular, can lead to the dysfunction of numerous regulatory factors and alteration of the tumor microenvironment (TME). The changes in the TME subsequently promote the development of tumors and assist in immune escape by tumor cells, making it more challenging to treat EC and resulting in a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is important to understand the effects of TP53 mutation in EC and to conduct further research in relation to the targeting of TP53 mutations. This article reviews current research progress on the role of TP53 mutations in regulating the TME and in the mechanism of EC tumorigenesis, as well as progress on drugs that target TP53 mutations.

Keywords

- TP53 mutations

- p53 protein

- targeted therapies

- endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the most common gynecologic malignancies in the world. It is ranked first in developed countries and regions, where it is responsible for almost 50% of newly diagnosed gynecological malignancies [1, 2]. In 2017, the incidence rate for EC in Canada was 35.7 per 100,000 women, while the mortality rate was 5.3 per 100,000 women, with both rates rising quickly [3].

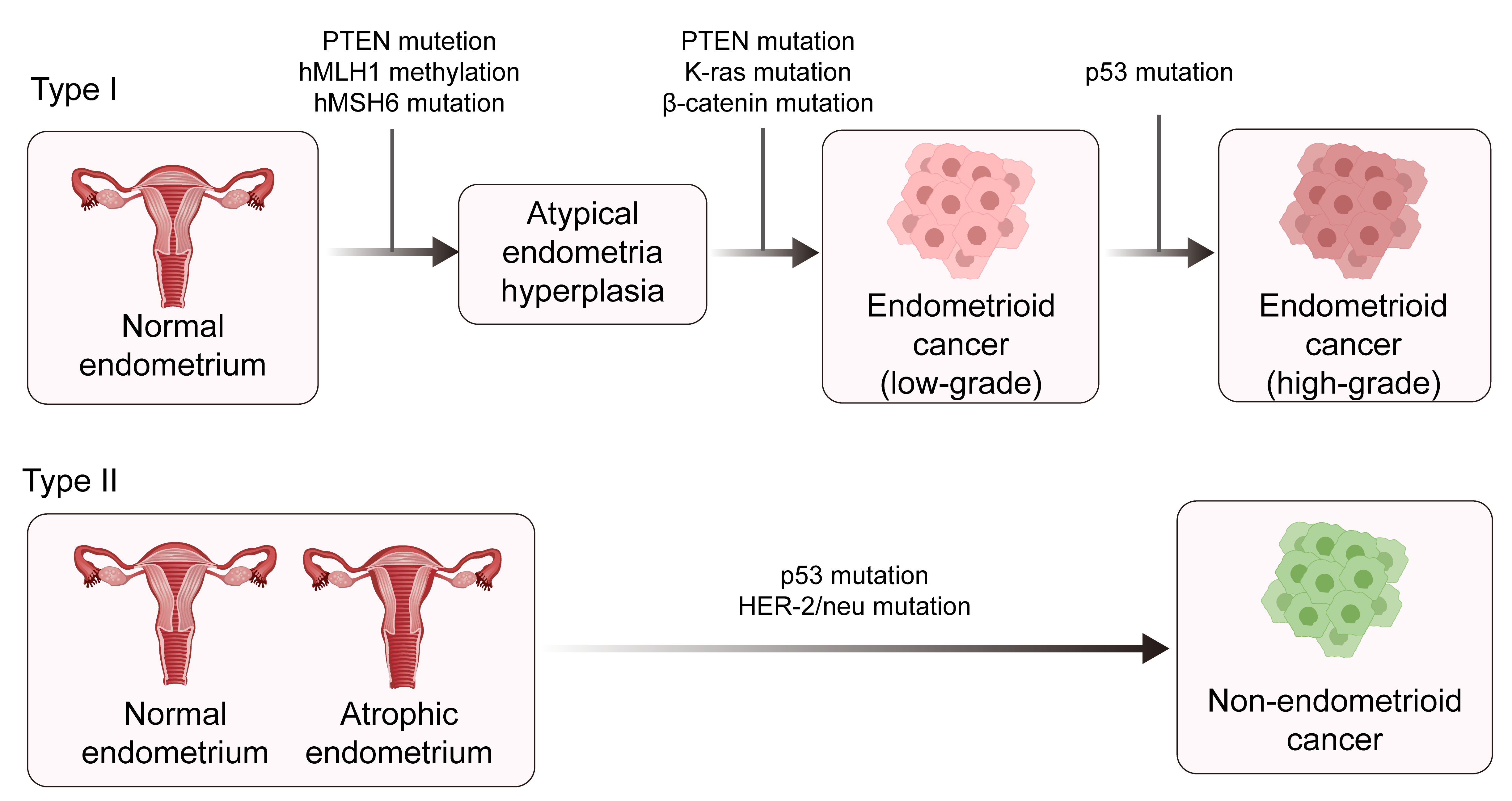

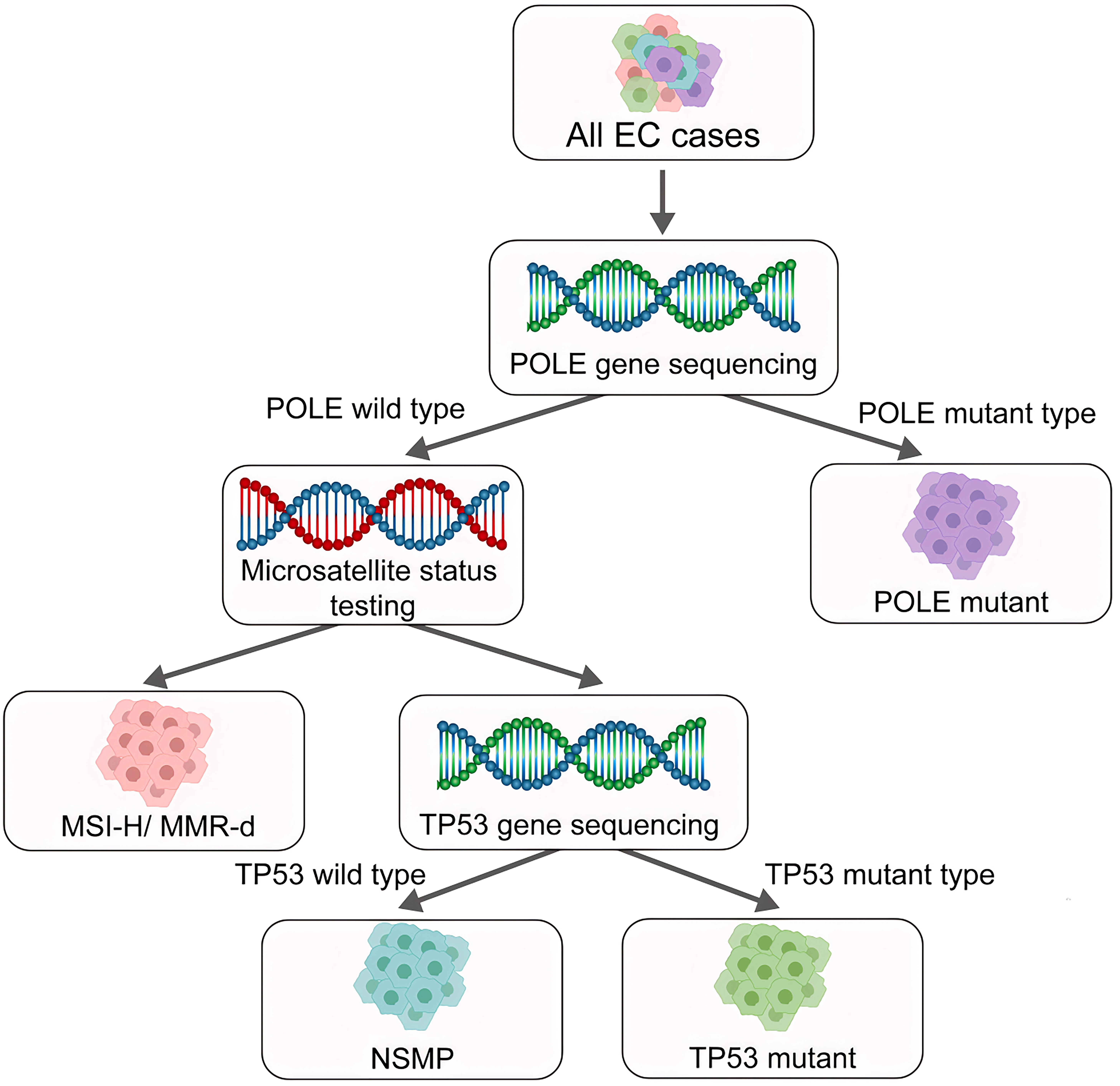

Traditionally, EC has been classified into two types according to the clinical features and pathological characteristics: estrogen-dependent type I and estrogen-independent type II [4, 5]. Type I is mainly endometrial adenocarcinoma that develops following hyperplasia of the endometrium and which usually occurs at a relatively young age. Type I ECs are the main type of EC. Type II ECs are mainly described as uterine serous carcinoma (USC), clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium, and other rare endometrial cancer types. Type II ECs are mostly poorly differentiated and have a poor prognosis (Fig. 1) [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. The formation of endometrial cancer is highly correlated with tumor protein P53 (TP53) mutations. The overall frequency of TP53 mutation in EC patients is approximately 25%, with a mutation frequency of 10%–40% in type I EC and about 90% in type II EC [11, 12]. With the advent of molecular oncology, a new molecular-based classification for EC consisting of four subtypes was suggested by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project in 2013 [11]. This classification was based on copy-number alterations (CNAs) and the tumor mutational burden (TMB), as shown in (Fig. 2) [13]. The four subtypes of EC are DNA Polymerase Epsilon, Catalytic Subunit (POLE)-mutated, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), low number of CNAs and TMB, and a stable microsatellite status (CN-low); a high number of CNAs and low mutational burden (CN-high) [13]. This molecular classification scheme was subsequently found to be closely associated with the TP53 mutation status [4, 11, 14]. Therefore, a more thorough understanding of the role of TP53 mutation in EC is critical for defining the mechanism of tumorigenesis.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The pathogenesis of type 1 and type II endometrial cancer. PTEN, phosphatase, and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten; hMLH1, human mutl homolog 1; hMSH6, heterodimer of MutS homolog 6; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor 2. Created with Adobe illustrator 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. New molecular subtypes of endometrial cancer as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO). Based on molecular oncology research, the WHO classified Endometrial Cancer (EC) into four subtypes: Polymerase Epsilon (POLE) mutant type, MSI-H/MMR-d type, NSMP Type, and P53abn type/TP53 mutant type. MSI-H, high microsatellite instability; MMR-d, mismatch repair deficiency; NSMP, non-specific molecular profile; P53abn, Abnormal p53. Created with Adobe illustrator 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Epidemiological and clinical studies have found many risk factors associated with EC tumorigenesis. Conditions such as metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, and polycystic ovary syndrome are known high-risk factors for EC [15, 16, 17, 18]. The risk factors for type I EC are related to nonantagonistic exposure of the endometrium to estrogen, including nonantagonistic estrogen therapy, early menarche, late menopause, tamoxifen treatment, miscarriage, infertility or ovulation failure, and ovarian polycystic ovary syndrome [19]. Menstruation and reproduction factors have been linked with EC occurrence, with age at menarche being an important related factor. The relative risk of EC for individuals with menarche before the age of 12 years is 1.5–2-fold higher compared to those with later menarche. In addition, for early menopausal women, even early menarche rarely increases the risk of endometrial cancer. Similarly, for women with late menarche, late menopause is unlikely to increase the risk of endometrial cancer. The total number of menstrual cycles in a lifetime is related to the occurrence of endometrial cancer. The risk of EC in postmenopausal women is 2.4 times higher in those who experience menopause before the age of 49 and 1.5–2.5 times higher than that in those who experience menopause before the age of 45. Pregnancy is another risk factor for EC, with the risk being higher in women who have never been pregnant compared to those with a history of pregnancy. About 15% to 20% of EC patients have a history of infertility, which may be related to a lack of protection of the endometrium by progesterone and prolonged exposure to estrogen stimulation [20]. Many studies have also shown that the use of estrogen replacement therapy can increase the risk of EC by 10–20-fold [20, 21, 22, 23]. Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that has pro-estrogenic effects in the uterus. The use of tamoxifen can approximately double the risk of both endometrioid and non-endometrioid EC types. The use of tamoxifen for

TP53 is widely considered to be the most frequently mutated gene in human tumors [28, 29, 30]. This tumor suppressor gene plays a vital role in the surveillance of oncogenic cell transformation and intracellular metabolism, as well as the regulation of the tumor immune microenvironment. Consequently, TP53 is widely considered to act as a guardian of the genome [31]. According to TCGA data, TP53 mutations are present in all four TCGA subtypes of endometrial cancer. In POLE-mutated type of EC, the TP53 mutation rate is as high as 35%. In MSI-H type of EC, the TP53 mutation rate is about 5%. In CN-low type of EC, the TP53 mutation rate is about 1%, while in CN-high type of EC, the TP53 mutation rate is as high as 90% [26]. It is, therefore, crucial to clarify the role of TP53 in the occurrence and progression of EC, as this could lead to better treatment of this cancer type.

At present, the standardized treatment for EC relies mainly on surgery. After surgery, patients may receive adjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy, depending on the tumor stage. With ongoing progress in the molecular classification of tumors, EC treatment is gradually entering the era of molecular-level precision therapy. According to the related research, various strategies for the treatment of endometrial cancer based on the different molecular subtypes of tumors have been put into clinical application. Some common targets and targeted therapy pathways have been discovered in the targeted therapy of endometrial cancer, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2). In addition, targeted drug research targeting TP53 mutations has become a new hotspot. With the continuous progress and updates of molecular typing-related research, the treatment of EC is gradually entering the era of molecular-level precision therapy.

An increasing number of studies have shown the tumor microenvironment (TME) is influenced by tissue remodeling and the inflammatory response [32, 33, 34]. The TME plays a crucial role in various physiological processes, as well as the development, growth, and metastasis of tumor cells and the maintenance of cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs can self-renew and differentiate into the various cell types that make up tumors [35, 36]. A better understanding of the relationship between p53 and the TME is critical and may help to develop new therapeutic methods and diagnostic biomarkers. Moreover, research into how TP53 affects EC tumorigenesis and progression may lead to more effective measures for the prevention of tumor occurrence.

Mounting evidence has shown that p53 plays a critical role in various physiological processes (Fig. 3), particularly in relation to cell cycle arrest, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, senescence, DNA repair, and cell apoptosis. p53 can activate direct transcription of the p21 gene, a critical member of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor family, to induce cell cycle arrest at the G1/S boundary and thus regulate cell senescence [37]. p53 can also activate the intrinsic apoptotic pathway to induce cell death in a process involving the BCL-2 protein family. This family includes three types of protein with various functions, namely pro-apoptotic BH3 proteins that initiate apoptosis, apoptotic effectors that can kill cells, and pro-survival family members that can prevent apoptosis [38, 39]. Animal experiments have further revealed the role of p53 and these critical factors in the regulation of apoptosis. Notably, experiments with Puma/Noxa double knockout mice and Trp53 knockout mice found that lymphocytes from both strains showed resistance to the aforementioned influencing factors. These results indicate that Puma and Noxa directly regulate transcriptional activation, thus accounting for the apoptosis-inducing action of p53, at least in these cell types [40, 41]. Furthermore, 2-hydroxy estradiol (2OHE2) and 2-methoxy estradiol (2ME) can induce G2/M cell cycle arrest in a process related to the activation of p53 [42]. This involves increased expression of Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-inducible 45 (GADD45) and p21, inactivation of Cell division cycle protein 2 (Cdc2), and decreased expression of Cyclin B1. Recent work has also shown that mutant p53 can increase the growth of EC cells via activation of the protein kinase B/ mammalian target of rapamycin (Akt/mTOR) pathway. In vitro experiments have shown that drugs that silence p53 can inhibit the proliferation of HEC-59 and AN3CA cells and restrict the phosphorylation of Akt and p70S6K. Disruption of mutant p53 reduced cell proliferation and activity of the Akt/mTOR pathway, while silencing of mutant p53 expression resulted in increased expression of CDK6, p-Akt, and c-Myc [43].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The role of p53 protein. The p53 protein plays a crucial role in a host of physiological processes, including the promotion of angiogenesis, promotion of cell apoptosis, regulation of metabolism, and the regulation of DNA repair. Created with Adobe illustrator 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

p53 is a key promoter of ferroptosis in EC through various transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11) is a cysteine transporter protein associated with the prognosis of EC. The first mechanism by which p53 can enhance ferroptosis is by inhibiting the expression of SLC7A11 and increasing the expression of transaminase 2 (GLS2) and spermidine/spermine N1 acetyltransferase1 (SAT1). p53 can also induce the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A)/p21 and inhibit the activity of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4), thus controlling ferroptosis through these two regulatory factors. Further exploration of the mechanism by which p53 regulates ferroptosis may provide new insights for the treatment of EC.

Numerous studies have shown that p53 regulates cellular metabolism through a complex mechanism involving the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, glutamyl hydrolysis, glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, lipid metabolism, polyamine biosynthesis, nucleotide synthesis, and pentose phosphate pathway [44, 45]. Cellular metabolism is, therefore, closely related to the stability and activation of p53, and numerous studies have shown p53 to be a key sensor in the regulation of nutritional and energy status [46, 47, 48, 49]. p53 inhibits expression of the malic enzyme 1 (ME1) and malic enzyme 2 (ME2), which catalyzes the oxidation and decarboxlation of malic acid to pyruvate with concomitant production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). ME1 and ME2 are essential for lipid generation and glutamine metabolism and can also regulate cell proliferation and metabolism. The downregulation of ME1 and ME2 activates p53 through a feed-forward mechanism. This is mediated by protein kinases that are activated by murine double minute 2 (MDM2) and adenosine monophosphate (AMP), leading to strong induction of the cell aging process [50].

p53 can enhance metabolic function by recruiting essential proteins. Different cell lines exhibit varying sensitivities to glutamine deficiency in vitro, mainly due to their different levels of p53 activity [51]. The primary regulator of glutamine breakdown, glutaminase 2 (GLS2), converts glutamine into glutamate and plays a crucial role in cellular energy production. p53 can control the metabolic breakdown of glutamine by regulating the expression of GLS2. Furthermore, GLS2 can reduce the sensitivity of cells to reactive oxygen species (ROS) -related apoptosis in a process that is highly dependent on the involvement of p53 [52]. In addition, p53 can regulate the activity of the TCA cycle by inhibiting the expression of the malate enzymes, leading to accelerated cellular aging [53]. p53 can also activate critical proteins in lipid metabolism to capture lipids from cancer cells. Guanidine acetate methyltransferase (GAMT) uses S-adenosylmethionine as a methyl donor to convert guanidine acetate to creatine. GAMT can also promote fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and creatine biosynthesis. This physiological process has an important role in maintaining energy homeostasis when the body lacks glucose as an energy source [54]. p53 regulates fatty acid metabolism by activating and modulating the expression of GAMT. Under starvation conditions, GAMT requires the involvement of p53 to activate and promote energy expenditure and cell apoptosis. Sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) is a key transcription factor that can target adipogenic genes. The transcription of p53 can regulate lipid metabolism by inhibiting the expression of SREBP [50]. In addition, wild-type p53 and mutant p53 exhibit different functions in the regulation of lipid metabolism. Under normal circumstances, wild-type p53 can inhibit the mevalonate pathway. However, the regulatory pathways and mechanisms undergo significant changes when p53 is mutated since it can bind and activate SERBP1/2. This process induces the expression of many key genes in the fatty acid synthesis and mevalonate pathways, thereby promoting oncogenesis [55].

Interactions between the host and the microbial community in the body can affect and regulate metabolism. The metabolites produced by microbial digestion of food are key factors that influence the regulation of metabolism. Mutant p53 has been found to interact with gut microbiota to promote tumor development. Experiments with mouse models have shown different effects of mutant p53 depending on its location in the intestine, which may be related to the gut microbiota and its metabolites at that location. The expression of mutant p53 in the distal part of the intestine can promote tumor development. In contrast, the expression of mutant p53 in the proximal part of the intestine can inhibit tumor occurrence and development. These results imply the effects of mutant p53 depend on the gut microbiota and its metabolites. Mechanistically, gallic acid produced by the gut microbiota endows p53 mutants with pro-tumorigenic functions that promote malignant phenotypes. The administration of gallic acid promotes WNT-mediated activation of transcription factor 4 (TCF4) and reactivation of promoter binding, resulting in pro-tumor effects in organoid and mouse models [56]. It is worth noting that the effect of gallic acid on mutant p53 is not stable. In experiments with mice, this effect can even be reversed under the influence of different reagents. The targeting of microbial communities and their metabolites with gallic acid antagonists can, therefore, alter the function of mutant proteins, offering a novel strategy for tumor treatment [57].

TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human tumors and is generally recognized to be a tumor suppressor gene [29]. The p53 protein encoded by TP53 has crucial functions in response to diverse cellular stresses, including the activation of oncogenes, nutritional deficiency, oxygen deficit, and DNA damage [58, 59, 60]. It acts as a transcription factor for various tumor-related genes and is also an important tumor suppressor-related factor. p53 protein binds to specific DNA elements located in the promoter region, allowing it to control numerous cellular physiological processes [61, 62]. The blocking and elimination of tumor cells by p53 provides essential protection against cancer development. In addition, p53 is crucial for genome stability by delaying the cell cycle, therefore allowing more time for DNA repair. Because of its major role in preventing tumor development, p53 is widely referred to as the “guardian of the genome” [31]. Moreover, mutation of the TP53 gene is the most common genetic alteration found in human tumors, with over 50% of primary tumors having this mutation [63]. Mutation of the TP53 gene usually leads to dysfunction of the p53 protein.

Increasing evidence suggests that mutant p53 can have significant impacts on the TME. Chronic inflammatory disorder is a high-risk factor for cancer, and tumor-associated inflammation is one of the characteristics of this disease [64]. Research has shown that tumor occurrence and wound repair share similar molecular mechanisms [65, 66]. Wound repair is a complex process that begins with the migration of inflammatory cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and mast cells, to the location of the wound. These inflammatory cells produce growth factors, proteases, and cytokines that participate in the formation of new tissue [65, 67]. Cytokines and inflammatory mediators also play a crucial role in altering the inflammatory microenvironment and enhancing the wound-repair function of tissue stem cells. This regulation is mainly achieved by stimulating the recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [68]. Inflammatory cells can fulfill a similar process in the TME. There is evidence that MSCs move to the tumor site and differentiate into tumor-associated MSCs (TA-MSCs) [36, 69]. The TA-MSCs can produce inflammatory cytokines such as chemokines, tumor necrosis factor-

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a multifunctional cellular process characterized by changes in the epithelial cell phenotype, such as the loss of cell polarity, cell-cell adhesion, and connection to the basement membrane [78, 79]. Compared to ordinary tumor cells, those with the EMT phenotype exhibit basic mesenchymal features and show more aggressive characteristics. They are also more prone to developing drug resistance, resistance to aging, immune escape, promotion of stress response, and acquiring stem cell-like characteristics [80]. Furthermore, wild-type p53 can interact with the EMT-inducing transcription factor Snail2 to induce its degradation. However, the p53 mutation increases the expression of Twist1, an EMT-inducing transcription factor that normally inhibits the degradation of Snail2 [81, 82, 83, 84]. As a result, the expression of Snail2 is increased, thereby inducing EMT activity. These studies demonstrate a close correlation between p53 activity and EMT. Some studies have also shown that p53 is heavily involved in the inflammatory response that alters the TME [85, 86]. The transcription factor nuclear factor-

Therefore, TP53 mutations are closely related to tumorigenesis. TP53 mutations often lead to abnormal function of the p53 protein. Mutant p53 can alter TME and promote tumor production by regulating inflammatory mediators and cytokines. In addition, tumor immune escape, cell migration, and other processes are closely related to p53. In addition, TP53 mutations have a high mutation rate in EC. The study of TP53 mutations and p53 regulatory mechanisms may provide great help in understanding the mechanism network of endometrial cancer formation.

Traditionally, surgery is the primary treatment modality for EC. After surgery, EC patients may also be treated with adjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and endocrine therapy, depending on the tumor stage and molecular features. Continued advances in molecular profiling have gradually allowed the introduction of molecular-level precision therapy for EC. Considerable progress has also been made in immunotherapy and targeted therapy, bringing hope to patients with recurrent or metastatic EC.

Numerous mutated genes and abnormal signaling pathways can induce EC, and drugs that are directed against these and related molecular targets have entered clinical trials. Trastuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets HER2. When combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel, this drug was shown to reduce the likelihood of EC progression [104, 105]. Other targeted drugs, such as the polyadenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor Olaparib, as well as anti-angiogenic drugs, are also undergoing clinical trials in EC (Table 1).

| Category | Drug | Clinical Trial ID |

| Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and HER2 Inhibitor | Trastuzumab | NCT01367002 |

| Targeting of the PTEN and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | Everolimus | NCT01068249 |

| Ridaforolimus | NCT00739830 | |

| Polyadenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor | Niraparib | NCT03016338 |

| Olaparib | NCT03745950 | |

| BMN673 | NCT02912572 | |

| Multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Lenvatinib | NCT03517449 |

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PTEN, phosphatase, and tensin homolog; mTOR, mammalian/mechanistic targets of rapamycin.

Although mutation of TP53 is prevalent in cancers, research on drugs that target TP53 mutations is arduous and slow. A possible explanation is that p53, a nuclear transcription factor, has special features as a drug target. Mutation of TP53 can result in the abolition of its tumor suppressive functions, meaning that drugs would need to reactivate the mutant protein. However, most small-molecule drugs that target cancers work by inhibiting excessive protein activity [106]. Consequently, it has long been considered that mutant p53 cannot be targeted by drugs. As discussed above, there is increasing evidence that loss of p53 function in tumor cells can strongly influence the TME, thus helping cancer cells to escape immune attack. The previous study has shown that restoration of normal p53 function in cancer cells may be a feasible therapeutic strategy since it would allow immune checkpoint inhibitors to act on p53 and increase p53-related sensitivity to drugs [107]. Scientists have now attempted these new strategies in clinical trials. Tumors with different TP53 states require very different small-molecule targeting strategies. For tumors with TP53 missense mutations, small-molecule drug development should mainly focus on restoring the wild-type conformation and activity of the mutant p53 protein. For cancers with wild-type p53, the main strategy is to stop p53 from being inhibited by negative regulatory factors, allowing it to regain its full activity. A 2002 study reported that reactivation of p53 with 2,2-Bis(hydroxymethyl)-3-quinuclidinone (PRIMA-1) could induce massive apoptosis. PRIMA-1 is a compound that can restore wild-type p53 function by binding to mutant p53, thereby inducing apoptosis in Saos-2 cells and inhibiting tumor formation by these cells [108]. A new methylated derivative of PRIMA-1 called PRIMA-1 MET, also known as APR-246, was later developed. This was shown to have better activity than PRIMA-1 in in vitro and preclinical studies [109, 110]. In clinical trials of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), APR-246 promoted cytotoxicity and apoptosis in AML cell lines and primary AML patient cells in a dose-dependent manner. In the previous clinical study, cells from patients with TP53 mutations and complex karyotypes showed high resistance to conventional anti-tumor drugs but showed no significant sensitivity to APR-246 drugs [111]. Mechanistically, APR-246 can enhance the expression of active caspase-3 and increase the level of p53 protein [111]. The combination of APR-246 with conventional chemotherapy drugs in a clinical study produced a synergistic effect [111]. APR-246 was also shown to promote apoptosis in small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) cell lines, and the injection of such cells into mice inhibited tumor growth [111]. Two-phase I/II clinical trials of APR-246 are currently underway. Combination therapy with azacitidine showed substantial efficacy in treating patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or AML patients with p53 mutations [112, 113]. In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved APR-246 as a breakthrough therapy for the treatment of MDS. Recently, a phase II trial that evaluated the combination of APR-246 with azacitidine reported encouraging results, with a 1-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate of 58% and a median overall survival (OS) time of 19.3 months [106]. Additional clinical trials using APR-246 as a monotherapy or combination therapy are currently being conducted or planned.

For the targeting of tumors with wild-type p53, the most widely used strategy is to maintain wild-type p53 expression and inhibit its degradation. Mouse dual minute 2 homolog (MDM2) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. The mechanism of p53 degradation involves ubiquitination by MDM2. This involves the direct binding of MDM2 to p53, leading to the degradation of the p53 protein in proteasomes [114, 115]. Based on the treatment strategy of stabilizing and restoring p53 function and preventing its degradation, experimental drugs that inhibit the binding of MDM2 to p53 have been investigated. The goal of such inhibitors is to restore p53 function and inhibit p53 protein degradation, thus providing targeted therapy for tumors. The first of these inhibitors was nutlin, which can induce p53 activation in cancer cells with wild-type p53 status but does not act on cells with mutant p53 [116]. RG7112 is a derivative of nutlin and was the first MDM2 inhibitor tested in clinical trials [117, 118]. In patients with refractory recurrent CML and AML, RG7112 triggered activation of wild-type 53 and increased the expression of many p53 target genes. Although the anti-leukemia activity of RG7112 was observed in many patients, the therapeutic effects are strongly dose-dependent, with high doses often required to achieve clinical benefit. This imposes a heavy burden on the normal cells and organs of the body, frequently causing to side effects such as gastrointestinal intolerance and thrombocytopenia [118, 119]. Further research led to a third-generation derivative of nutlin, idasanutlin (RG7388), which subsequently replaced RG7112 [120]. Several clinical trials are currently testing the effectiveness and safety of idasanutlin in different tumor types. In addition to the various nutlin protein derivatives mentioned above, many other experimental drugs that inhibit the binding between MDM2 and p53 are also being developed and tested. For example, APG-115 is an oral MDM2 inhibitor that has shown strong anti-tumor effects in preclinical AML models. In addition, APG-115 was found to increase the sensitivity of cancer xenografts to radiotherapy, thereby improving the efficacy of tumor treatment [121]. APG-115 is currently being evaluated in numerous clinical trials, including NCT03611868, NCT02935907, NCT0037816, and NCT04785196 [106, 122].

Approximately 10% of the TP53 mutations in tumors are nonsense mutations that produce truncated proteins. Generally, such proteins are rapidly degraded [123]. Due to the short lifespan of these truncated proteins and because they lack many p53 protein sequences, reactivation through the methods described above may not be achievable. Two alternative methods have, therefore, been proposed to activate the p53 signaling pathway in cancer cells with p53 truncation mutations [106]. The first uses gentamicin, aminoglycoside antibiotics, and their derivatives, such as G418 and NB124, to promote translation and prevent the translation mechanism from terminating at stop codons located on the RNA, thereby producing normal, full-length p53 protein [124, 125]. The other alternative is to inhibit nonsense-mediated mRNA degradation (NMD) [106]. For example, NMD14 targets the structural pocket of SMG7, which is a crucial component of the NMD mechanism [126]. Similar drugs, such as ataluren, are undergoing phase III clinical trials for cystic fibrosis [106]. There have also been attempts to eliminate the gain of function activity of mutant p53 by targeting its rapid degradation. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) has been shown to reduce the degradation of mutant p53, with some studies reporting that long-term inhibition of HSP90 can improve the survival rate of mice carrying tumors that express mutant p53 [106].

Although no p53-targeted cancer drugs have yet been approved, many have undergone clinical trials (Table 2). With the continuous advances in new technologies and extensive research into p53, it is hoped that cancer treatment drugs targeting p53 will soon be available in clinical practice for the benefit of many more patients.

| Drug | Cancer type | Clinical Trial ID |

| RG7112 | Hematological system tumors | NCT00623870 |

| Idasanutlin | Acute myelocytic leukemia | NCT02545283 |

| PEITC (phenethyl isothiocyanate) | Oral cancer | NCT01790204 |

| ATO/Trisenox | Acute myelocytic leukemia | NCT03381781 |

| ALRN-6924 | Solid malignancies | NCT05622058 |

| Wee1 inhibitor (adavosertib/AZD1775/MK-1775) | Advanced malignant tumors | NCT02042989 |

| Tanespimycin | Multiple myeloma with p53 mutations | NCT00514371 |

| Lamivudine (3TC/Epivir/Zeffix/DELSTRIGO) | Metastatic colorectal cancer | NCT03144804 |

| APR-246 (eprenetapopt, PRIMA-1MET) | Advanced solid tumor | NCT04383938 |

| Atorvastatin | Solid malignancies with p53 mutations | NCT03560882 |

| HSP90 inhibitor (ganetespib/STA-9090) | High-grade platinum-resistant ovarian cancer | NCT02012192 |

| Zoledronic acid (ZA/Reclast/Zometa) and atorvastatin | Triple-negative breast cancer | NCT03358017 |

| SAR405838 | Malignant tumors | NCT01636479 |

| KRT-232 | Merkel cell carcinoma | NCT03787602 |

| MK-8242 | Acute myelocytic leukemia | NCT01451437 |

| Siremadlin | Solid malignancies | NCT02143635 |

| APR-246 | Hematologic malignancy, Prostate malignancies | NCT00900614 |

| COTI-2 | Solid malignancies with p53 mutations | NCT02433626 |

| Milademetan | Advanced solid tumor, Lymphoma | NCT01877382 |

| Alrizomadlin | Metastatic melanomas | NCT03611868 |

The research on the prognostic value of TP53 mutation in EC still has faultiness. TP53 mutations are associated with pathological histological subtyping and have certain prognostic values. As mentioned above, the traditional classification of EC involves two subtypes. Dysfunction of the p53 protein is intimately related to TP53 mutation. The overall frequency of TP53 mutation in EC patients is approximately 25% [11, 12], with a mutation frequency of 10%–40% in type I EC and about 90% in type II EC. Schultheis et al. [12] investigated TP53 mutations in 228 cases of EC, comprising 186 endometrioid carcinomas and 42 serous carcinomas. These authors found that TP53 mutations were associated with significantly poorer survival in serous EC, which is the major type II EC. When comparing the prognosis of four types of endometrial cancer classified by TCGA, the p53mt group had the worst prognosis among the four TCGA groups. In univariate analysis, the risk of death in the P53mt group was 3–5 times higher than that in the P53wt group and 2 times higher after adjusting for clinical-pathological factors. This indicates that, on the one hand, TP53 mutations have strong independent prognostic value, and on the other hand, other clinical-pathological factors still play a role in worsening prognosis [127, 128]. Patients with abnormal immunohistochemical expression of p53 have a poorer prognosis and even worse prognosis when associated with other unfavorable prognostic factors. The immunohistochemical expression of p53 should be evaluated as a key prognostic factor [129]. In addition, the prognosis of endometrial cancer is influenced by numerous unpredictable clinical factors, such as staging, patient age, and pathological grading [130, 131, 132, 133]. Further research is needed to investigate the impact of these factors on the prognostic value of TP53 mutations and p53 overexpression.

So far, research on the function of the TP53 gene and p53 protein has been quite in-depth due to TP53, which is the most common mutated gene in human tumor cells and is often associated with poor prognosis of tumors. Research on the function of mutant p53 in EC and related targeted therapies has naturally received increasing attention from researchers, and some targeted drugs targeting TP53 mutations have even entered clinical trials. However, there are still many urgent problems to be solved in this field. The mutation frequency of TP53 varies among different tumor types. For example, according to TCGA data, the overall TP53 gene mutation rate in EC is about 25%. The mutation rate of the TP53 gene in type I EC is 10–40%, while the mutation rate of the TP53 gene in type II EC is as high as 90% [11, 12]. In non-small cell lung cancer, the mutation rate is around 50%, while in small cell lung cancer, the mutation rate can be as high as 90% [134]. The differences in the mutation mechanisms of TP53 mutations in different types of tumors and the reasons for these differences still need further research. Secondly, TP53 mutations occur at different sites in the gene, with eight mutations located in codons, accounting for about 28% of the total p53 mutations, and are considered hotspot mutations [135]. In addition, the impact of non-hotspot mutations on tumor development and their functional differences from hotspot mutations are still unclear. By studying this issue, we can further understand the mechanism network of TP53 mutations. With the research on the mechanism of TP53 mutations, combined with molecular and pathological typing of EC, it is believed that the prognostic value of the TP53 gene and abnormal p53 protein can be further explored, providing great help for the diagnosis and treatment of clinical EC. In terms of targeted therapy, the vast majority of current research is conducted in animal models and in vitro environments. Although drugs targeting FGFR2, mTOR, and other targets have been discovered, a large number of clinical trials are still needed to verify their efficacy. Targeted drugs targeting the TP53 gene are a hot topic in clinical research, providing new ideas for targeted therapy. However, such drugs also lack a large number of clinical trials to verify their efficacy. Secondly, some targeted drugs that have entered clinical trials have not shown significant therapeutic effects as monotherapy, and their combination with chemotherapy and immunotherapy is also a focus of research. In addition, with further research on molecular subtyping and related biomarkers of EC, more accurate disease risk assessment can be conducted for patients. Researchers have tried to combine these studies with the targeted therapies. I believe that in the near future, this new approach can provide assistance to clinical doctors in developing more precise diagnoses and treatment plans for endometrial cancer, bringing huge benefits to patients.

In addition to the directions proposed above, we can also explore the following research directions. In terms of gene and biological functions, the study of the TP53 mutation mechanism and the function of mutant P53 protein is still important. In terms of p53 function research, the mechanism of interaction regulation between it and intestinal microbiota still needs to be improved. This research may provide new ideas for the discovery of clinical biopharmaceuticals. Secondly, the regulation of p53 protein on metabolic remodeling, especially its regulation of iron metabolism and iron death, needs further research. The mechanism of interaction between the P53 protein and other proteins still needs further research, which is also helpful for understanding the TP53 gene and the mechanism network of the p53 protein. In exploring precision therapy and targeted therapy methods, potential targets targeting the TP53 gene and p53 protein should continue to be sought. Concepts such as collateral lethality and synthetic lethality can be combined with targeted therapy to develop drugs that can avoid drug resistance and have better therapeutic effects. In addition, research on the TP53 gene and its related targeted drugs should not be limited to single-drug studies. Emerging immunotherapies and cellular immunotherapies can be combined with it to open up new diagnostic and therapeutic ideas.

The TP53 gene has critical functions in the cellular response to various stresses, including oncogene activation, DNA damage, malnutrition, and hypoxia. The p53 protein encoded by TP53 functions as an essential barrier against the development of tumors by blocking or eliminating cancer cell growth. TP53 is frequently mutated in EC, and the resulting abnormal p53 function is closely associated with EC tumorigenesis. Under the influence of TNF regulatory factors, mutant p53 can interact with NF-

We also summarized the latest cutting-edge studies involving the targeting of TP53 mutations in the treatment of cancer. Although we have yet to see significant progress in drug research targeting TP53 mutations, many clinical trials are still ongoing. New therapeutic approaches are emerging, such as restoring the conformation and therefore function of mutant p53 protein back to wild-type p53, and releasing p53 from inhibition by negative regulatory factors so that it can resume normal p53 function. With continued advances in new technologies and more extensive research on p53, we believe that drugs targeting TP53 mutation may soon be applied in clinical practice for the benefit of EC patients.

BZ wrote the manuscript. BZ and HZ contributed to the literature search. YQ contributed to the design of the article structure, the exploration of innovative points, the revision and correction of drafts and funding. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.