1 Department of Surgery, School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

2 Division of Gastroenterology-Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Maastricht University, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

Abstract

Sulfatides or 3-O-sulfogalactosylceramide are negatively charged sulfated glycosphingolipids abundant in the brain and kidneys and play crucial roles in nerve impulse conduction and urinary pH regulation. Sulfatides are present in the liver, specifically in the biliary tract. Sulfatides are self-lipid antigens presented by cholangiocytes to activate cluster of differentiation 1d (CD1d)-restricted type II natural killer T (NKT) cells. These cells are involved in alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) and ischemic liver injury and exert anti-inflammatory effects by regulating the activity of pro-inflammatory type I NKT cells. Loss of sulfatides has been implicated in the chronic inflammatory disorder of the liver known as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC); bile ducts deficient in sulfatides increase their permeability, resulting in the spread of bile into the liver parenchyma. Previous studies have shown elevated levels of sulfatides in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), where sulfatides could act as adhesive molecules that contribute to cancer metastasis. We have recently demonstrated how loss of function of GAL3ST1, a limiting enzyme involved in sulfatide synthesis, reduces tumorigenic capacity in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cells. The biological function of sulfatides in the liver is still unclear; however, this review aims to summarize the existing findings on the topic.

Keywords

- sulfatide

- GAL3ST1

- liver disease

- bile duct

Sulfatides or 3-O-sulfogalactosylceramides are a class of sulfated glycosphingolipids present mainly in the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane in eukaryotic cells [1]. In the human body, sulfatides are widely expressed in various organs and involved in many biological processes such as platelet adhesion and aggregation, myelinating cell differentiation, insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells, ammonium excretion in renal epithelial cells, and the modulation of the immune system [2, 3, 4, 5]. Sulfatide metabolism is altered in different diseases, including nervous and renal diseases, and different types of cancers [6].

A previous study demonstrated the presence of sulfatides mainly in the brain, but also in the kidney and gastrointestinal tract. Sulfatides are most abundant in the nervous system, where they are one of the major glycolipid components of the myelin sheath [7]. Sulfatides are also rich in the kidneys and are highly concentrated in the medulla, where they show a significant structural variability and are involved in the control of renal acidosis [8]. The presence of sulfatides in the gastrointestinal tract has been previously described. The enrichment of sulfatides in the duodenum and gastric mucosa is related to the protective role of these sulfoglycolipids since these tissues are exposed to pepsin and bile acids [9]. Sulfatides are identified as high-affinity ligands for galectin 4 in the intestine. Binding between sulfatides and galectin 4 at the apical membrane in a colon cancer cell line generates lipid rafts called detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs), playing a functional role in the clustering of lipid rafts for apical delivery [10].

The liver, another organ exposed to toxins, xenobiotics, and bile salts due to its unique metabolism and relationship to the gastrointestinal tract, employs robust protective mechanisms to promote liver regeneration, which require the cooperation of its diverse cell population, including hepatocytes, biliary epithelial cells or cholangiocytes, hepatic stellate cells, Kupffer cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells [11]. The liver plays a pivotal role as a central and major integrator for the metabolism of circulating lipid and lipoproteins. On this basis, sulfatides could be synthesized in the liver [12]. However, little is known about which cell type in the liver is capable of synthesizing and degrading sulfatides. In a human liver single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) dataset the expression of GAL3ST1 (an enzyme involved in sulfatide synthesis) is restricted to cholangiocytes [13]. Sulfatides have been described to be present in the biliary tract in the liver and show reduced levels in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) patients with severe cholestasis [14]. A very recent study showed how deficiency of GAL3ST1 in a cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cell line reduced tumorigenicity and partially recovered the epithelial identity of the cells. This enzyme was also shown to be essential for cell survival in thirty CCA cell lines [15]. This suggest that sulfatide may play a role in the biliary tract in the liver.

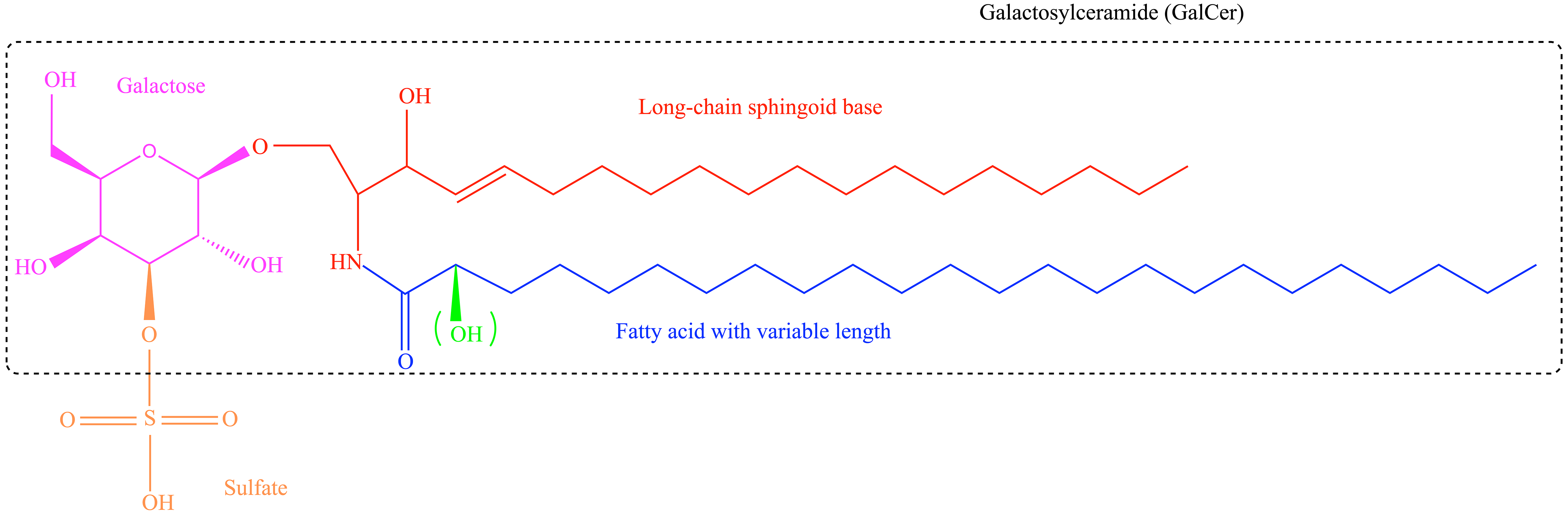

Sulfatide is composed of galactosylceramide (GalCer) and a polar sulfated carbohydrate head group. The basic sulfatide building block is ceramide, which consists of a long-chain sphingoid base linked to an acyl (fatty acid) chain via an amide bond. Sulfatides show structural variability with respect to their ceramide anchor, varying in chain length, hydroxylation, and saturation for both the sphingoid base and fatty acids [3, 16] (Fig. 1). Sulfatide species with different structures are tissue-specific [16, 17].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Structure of sulfatides. Sulfatides are composed of galactosylceramide (GalCer) and a polar sulfated carbohydrate sulfate group. Sulfatides contain various structures, including different acyl chain lengths and the ceramide moiety, which can be hydroxylated at the

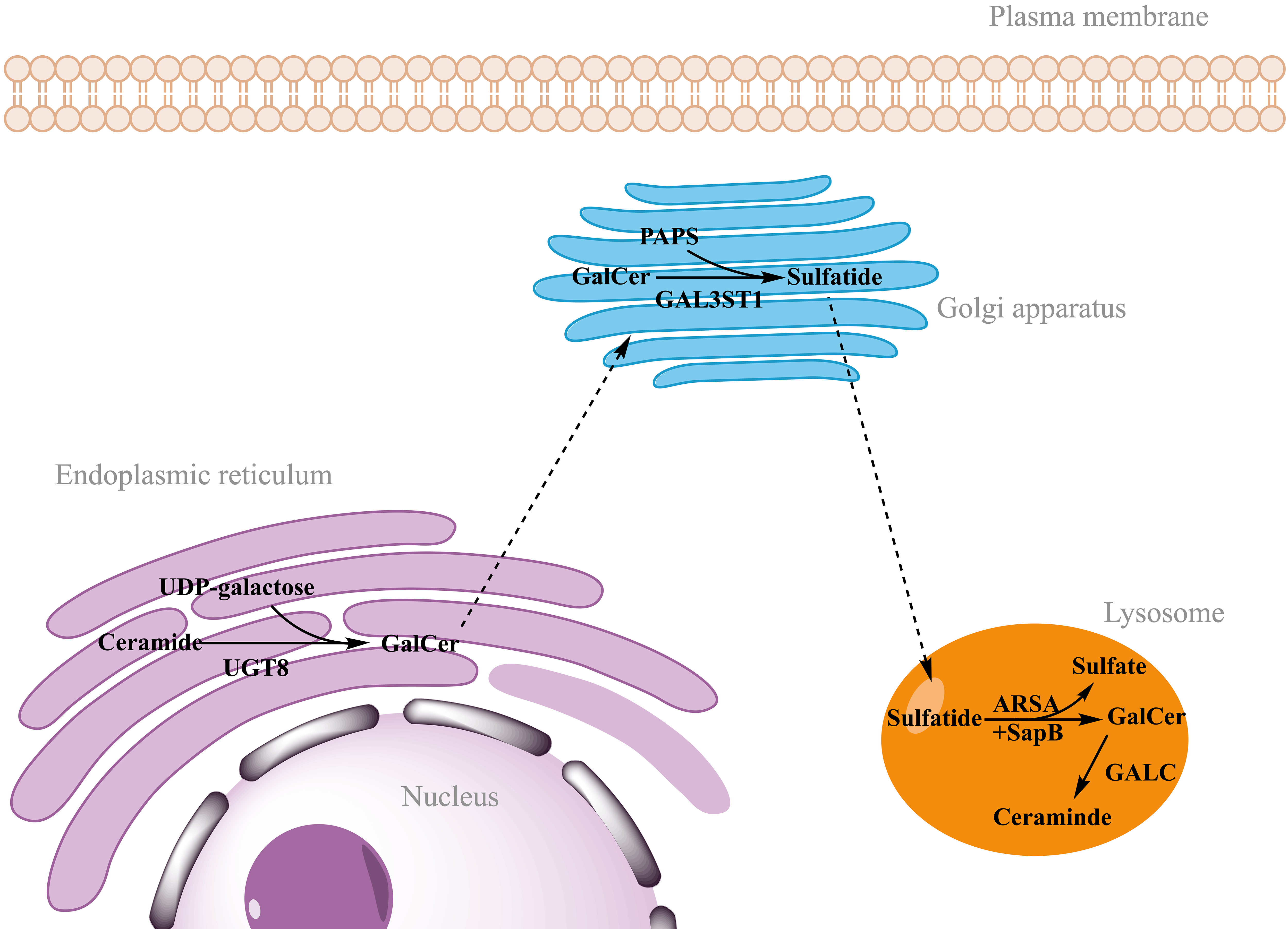

Sulfatides synthesis begins in the endoplasmic reticulum by the addition of galactose to ceramide by the action of the enzyme cerebroside galactosyltransferase (CGT, also called UGT8) [18]. This first step produces

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Synthesis and degradation of sulfatides. Sulfatide synthesis begins in the endoplasmic reticulum by the addition of galactose from UDP-galactose to ceramide, catalyzed by UGT8. After transport of GalCer to the Golgi apparatus, sulfatides are finally synthesized by addition of the sulfate group from PAPS catalyzed by the enzyme GAL3ST1. Sulfatide degradation takes place in the lysosomes, where ARSA hydrolyzes the sulfate group. This reaction requires the action of a non-enzymatic proteinaceous cofactor SapB that removes sulfatides from the membranes and makes accessible to ARSA. GALC catalyzes the hydrolysis of galactose from GalCer to ceramide. UDP-galactose, uridine diphosphate-galactose; UGT8, ceramide galactosyltransferase; GalCer, galactosylceramide; PAPS, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate; GAL3ST1, cerebroside sulfotransferase; ARSA, arylsulfatase A; SapB, saposin B; GALC, galactocerebrosidase. Figure created in ChemDraw (RRID: SCR_016768) Professional version 22.0 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

The presence of sulfatides in the liver was previously described in 1961. In this study, chromatography of 35S -labeled, acetone-insoluble hepatic lipids showed the presence of two sulfatides in the lipid extracts of the rat liver. The degeneration of liver cells induced by bromobenzene administration did not affect the sulfatide-sulfur concentration in the liver, corroborating the presence of sulfatide in liver tissue [22]. In another study, radioactive sulfatide was administered orally to mice, where it was absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and subsequently transported to different organs, including the liver [23]. This suggested that the sulfatides present in the liver may have originated, at least in part, from external sources. Sulfatides were also shown to be highly concentrated in the fetal porcine liver [24].

The liver is composed of multiple cell types, but the cellular distribution of sulfatide in the mammalian liver has been unknown. Specific lipid markers for structural elements of the liver have been identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI). Sulfatides are localized exclusively in a thin layer lining the bile duct, indicating that sulfatides are a specific molecular marker of the bile ducts [14]. The bile ducts form a complex three-dimensional network within and outside the liver called the biliary tree [25]. Biliary epithelial cells, or cholangiocytes, lining the central luminal surface of the biliary tree perform important physiological functions, such as modification of primary bile and maintenance of barrier function to prevent biliary invasion of the hepatic parenchyma [25, 26, 27].

The liver has an important immunological activity to protect against toxic agents and prevent hyper-reactive immune responses. A large population of immune cells regulates this activity. Hepatocytes are responsible for the production of 80–90% of circulating immune proteins, such as acute phase proteins, bactericidal proteins and complement factors to control systemic infection [28]. Liver macrophages are involved in phagocytosis of insoluble waste products and modulation of the hepatic inflammatory response [29]. Natural killer (NK) cells are innate immune cells, also present in the liver, that recognize a wide variety of antigens. Liver NK cells are part of the defense against pathogens and tumor cells by releasing cytotoxic proteins and cytokines [30].

The liver is also enriched in natural killer T (NKT) cells, a heterogeneous group of T lymphocytes that recognize self or microbial lipid antigens and activate signaling through Toll-like receptors. NKT cells are abundant in hepatic sinusoids and are capable of secreting pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines upon activation [28, 30]. NKT cells express both T cell receptor (TCR)-

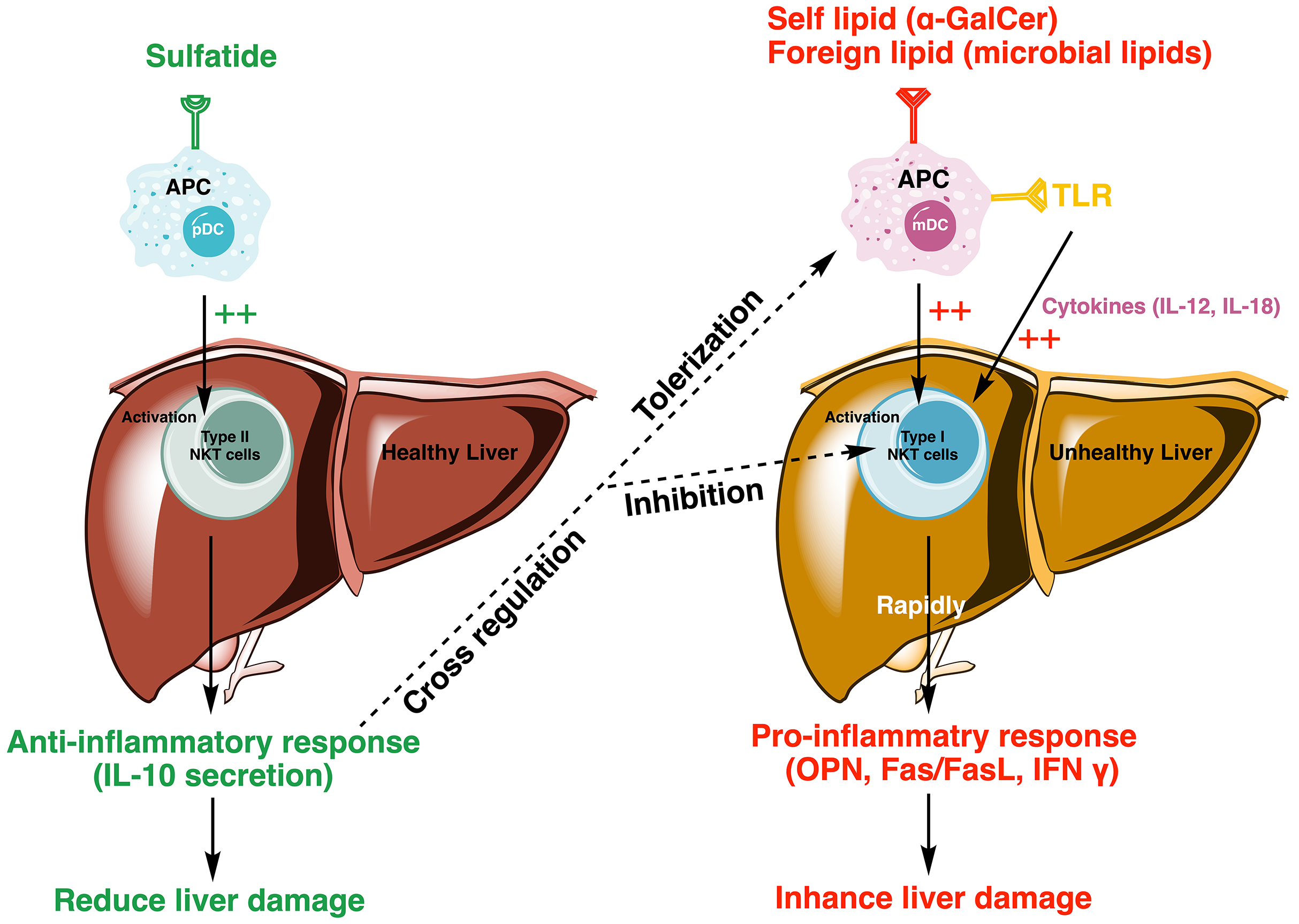

In contrast, type II NKT cells modulate the activation of type I NKT cells to reduce liver damage due to the inflammatory response. Activation of type II NKT cells depends on various TCRs in the liver. Sulfatides, as lipid antigens, can activate type II NKT cells via plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in the liver [33]. pDCs are innate immune cells responsible for interferon

Sulfatide-mediated activation of type II NKT cells is able to induce tolerogenic myeloid dendritic cells (mDC) and anergic type I NKT cells in the liver, modulating the immune response by reducing proinflammatory cytokine levels and fibrogenesis [5, 35] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Model depicting sulfatide-mediated activation of type II NKT cells reducing liver damage by regulating the proinflammatory cascade of type I NKT cells. Sulfatide activates type II NKT cells, initiating an anti-inflammatory response through the secretion of IL-10, which promotes tolerization in mDCs and inhibits the activation of type I NKT cells. In contrast, type I NKT cells, activated by autolipid or foreign antigens, such as

Alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) comprises hepatic steatosis, steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis, increasing the risk of developing hepatocarcinoma (HCC), and is becoming one of the most common causes of death in the United States [36].

Oxidative stress is one of the most studied mechanisms in alcohol-related liver injury, as reactive oxygen species (ROS) are released during ethanol metabolism [37]. Different sources of ROS after ethanol exposure have been described, but hepatic activation of cytochrome P4502E1 (CYP2E1) and the presence of inflammatory cytokines are the main inducers of ROS in the liver [38]. Hepatic alcohol metabolism consists of two oxidative processes. First, ethanol is converted in acetaldehyde through the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Acetaldehyde is transformed into acetate in mitochondria by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) action. Acetate is released into the circulation from the liver and oxidized in different tissues [39]. Hepatic metabolism of ethanol via ADH and ALDH is the main metabolic pathway at low ethanol concentrations, but in chronic ethanol consumption, microsomal CYP2E1 is activated [38, 39]. Activation of CYP2E1 releases oxygen free radicals leading to lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress that induce immune responses in the liver.

Alcohol-related liver injury depends on the activation of the type I NKT cells to secrete cytokines and chemokines, which are involved in the hepatic inflammatory response in hepatic steatosis development [40]. Accumulation and activation of type I NKT cells after alcohol ingestion in mice show a pathogenic role in ArLD by increasing hepatic IL-6 expression [41]. Hepatic metabolites after alcohol ingestion activate the initial immune response by Kupffer cell activation, releasing a large number of cytokines and chemokines involved in neutrophil recruitment from liver sinusoids to the liver parenchyma [41, 42].

Furthermore, J18-/- mice that lack type I NKT cells show reduced liver damage after chronic plus binge feeding alcohol diet evidencing the pathological role of these cells in ArLD [41]. The J18 gene is essential for TCR

In a chronic plus binge alcohol model in wild-type mice, intraperitoneal injection of sulfatides after ethanol administration improves the inflammatory profile in the liver of these mice. Sulfatides showed a protective role in animal models of ArLD by inhibiting type I NKT cells by blocking the pro-inflammatory response and neutrophil recruitment in liver parenchyma [41].

Serum levels of sulfatides are decreased in animal models of ArLD, and hepatic expression of GAL3ST1 is repressed due to oxidative stress in the liver of these mice. Altered sulfatide metabolism in the liver might contribute to ArLD pathogenesis, since exogenous administration of sulfatides improved the liver conditions in mouse models [44].

Liver surgery for the treatment of focal hepatic lesions and liver transplantation requires a period of ischemia to prevent excessive blood loss. The most common procedures are total hepatic vascular exclusion or Pringle maneuver [45]. Restoration of blood flow or reperfusion is followed by liver damage associated with prior oxygen and nutrient shortages [46]. Kupffer cells are activated during ischemia, being responsible for the production of ROS generating oxidative stress in the reperfusion period, contributing to cellular damage [47]. Kupffer cell activation is related to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF

Intraperitoneal administration of sulfatides before ischemia in wild-type mice reduced hepatic necrosis after reperfusion and improved serum biochemical parameters. However, injection of sulfatides in J18-/-mice before surgical procedure did not improve liver injury, suggesting that inactivation of type I NKT cells is the main protective mechanism of sulfatides in ischemia-reperfusion injury [5].

Pretreatment with sulfatides in a mouse model of ischemia-reperfusion liver injury results in an immunomodulatory response showing a reduced inflammatory response. Sulfatides administration before liver surgery could be considered as a therapeutic strategy to improve the outcome of patients who require hepatic resection or liver transplantation [5].

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology and low incidence whose diagnosis is based on elevated serum liver enzymes, presence of circulating autoantibodies, and prominent hepatitis in liver histology [48, 49].

Autoimmune liver diseases result from the imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory hepatic immune responses influenced by the activation of NKT cells. A recent study has demonstrated that sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells are abundant in the human liver and show a pro-inflammatory phenotype in AIH patients [50]. In this context, sulfatide-activated type II NKT cells have high levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and low levels of interferon (IFN). TNF is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that could be involved in the interaction between type II NKT cells and other intrahepatic immune cells, generating an inflammatory milieu in the liver of AIH patients [50].

Hepatitis C is a common liver disease worldwide caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), a hepatotropic RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family [51]. Seven major HCV genotypes and 86 subtypes have been described. After acute hepatitis C virus infection, 75–85% of patients may develop chronic hepatitis C [52]. Chronic HCV infection triggers a chronic inflammatory process, which might lead to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, HCC [51]. Fibrogenesis is the main complication of chronic HCV infection, which is associated with chronic hepatic inflammation due to oxidative stress and immune response directed to infected hepatocytes [53]. Several direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) mainly target three proteins involved in crucial steps of the HCV life cycle: the NS3/4A protease, the NS5A protein, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5B protein [54].

Lipids are key components in the viral life cycle that affect host-pathogen interactions. Multiple reports have indicated that HCV modulates lipid metabolism, including sphingolipid, to promote viral replication [55]. Chronic HCV infection is recognized as the major cause of mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC), an immune-complex-mediated vasculitis involving small vessels characterized by an underlying B cell proliferation. Elevated titers of both anti-ganglioside GM1 and anti-sulfatide antibodies were detected in the plasma of several patients with HCV-associated Immunoglobulin M kappa/ Immunoglobulin G (IgM

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by multifocal bile duct strictures due to liver inflammation and fibrosis [57]. The biliary tract is a system of ducts where bile is transported from the liver to the small intestine. The bile ducts are directly exposed to toxic components of bile and require protective mechanisms to prevent pathological conditions. Bile acids are components of bile required for fat digestion and fat-soluble vitamins absorption in the small intestine [58]. Bile acids are physiological detergents whose metabolism is strictly regulated in the liver since their high cytotoxicity. Impaired bile flow leads to bile acid accumulation under cholestatic conditions, a common condition found in PSC patients [57, 58]. The biliary tract shows different protective mechanisms against bile acid toxicity, such as the bicarbonate umbrella, by increasing the pH of the bile and reducing the cytotoxic effects of bile acids [59].

PSC etiology is unknown, but there are different hypotheses about the pathogenesis of this disease. PSC is commonly found in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); therefore, the gut-liver axis may be involved in the pathophysiology of this cholangiopathy [60]. Environmental and genetic factors may alter the gut microbiota that releases microbial compounds from the gut into the portal circulation, reaching the liver to activate hepatic immune response through gut-liver crosstalk [61]. These factors involved in PSC development may destabilize the bicarbonate umbrella to contribute to disease progression [62].

Sulfatides are limited to the biliary tract in the liver and, interestingly, sulfatides are absent in the liver of PSC patients with severe cholestasis [14]. Sulfatides can activate type II NKT cells to modulate inflammatory response by inactivating type I NKT in the liver. This specific presence of sulfatides in the biliary tract can be part of an immunomodulatory response to prevent bile duct inflammation and disease progression.

Sulfatides are also present in intestinal epithelial cells, where they interact with galectin-4 to generate lipid rafts in the apical membrane [10]. These lipid rafts are known as detergent-resistant membranes. Intestinal and biliary epithelia are exposed to high concentrations of bile acids, and they need protective mechanisms against the membranolytic effects of bile salts [63]. In this line, sulfatides present in biliary and intestinal epithelial cells could play a protective role against cytotoxic and membranolytic effects of bile salts.

Further studies are required to understand the functions of sulfatides in the biliary epithelium and their role in biliary diseases, but sulfatides can be part of a protective layer in the bile ducts whose absence can contribute to disease progression.

Cancer cells often express antigens at the cell surface. Specific glycosphingolipids (GSLs) are more highly expressed in tumors than in normal tissue, known as tumor-associated cell surface antigens, many of which facilitate uncontrolled cell growth and metastasis [64, 65]. As one of GSLs, sulfatides were found elevated expressed in many types of cancers, such as colon, ovarian, gastric, renal cell carcinoma, and breast cancer [66]. The pathologic functional roles of sulfatides in these cancer tissues are unclear; it has been believed that sulfatides present on the surfaces of cancer cells act as adhesive molecules by binding P-selectin to contribute to the facilitation of metastasis [67, 68].

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common form of liver cancer accounting for 90% of cases. HCC usually develops in the context of chronic liver disease and is an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis [69]. Sulfatides were found upregulated in HCC tissue and present in different HCC cell lines, which serve as an adhesion molecule on the membrane of HCC cells [70]. The level of sulfatides expression was positively correlated with metastatic potential in different HCC cell lines [71].

Transgenic (Tg) mice expressing hepatitis C virus core protein (HCVcp) were used to study the relationship between sulfatide metabolism and hepatocarcinogenesis. In HCVcpTg mice, the sulfatide contents in the liver were age-dependently increased, together with both oxidative stress and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR

The spatial distribution of sulfatide composition in HCC tumor tissue was monitored using MSI [73]. Sulfatides were detected in HCC tissue; however, the sulfatide species, viz. odd-chain hydroxylated species ST-OH [37:1], which dominates in HCC, are distinct from normal bile ducts, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA), or colorectal cancer liver metastasis (CRLM). Moreover, the predominant sulfatide species in the normal bile duct, iCCA, or CRLM, viz. hydroxylated species ST-OH [42:1], was virtually absent in HCC tumor tissues [73]. The distinct sulfatide composition in different liver cancers may aid in the diagnosis of different liver cancers. No significant association between sulfatide composition and survival rates (both overall and disease-free survival) was found in HCC patients [73]. Still, it will be worth studying the tumorigenic link of sulfatide species with HCC in the future.

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), the second most frequent primary liver cancer after HCC, is a group of very aggressive malignant neoplasms that originate in the biliary tree. Depending on the location of the tumor, CCA is anatomically divided into two subtypes: intrahepatic (iCCA) and extrahepatic (eCCA), the latter being further subdivided into perihilar (pCCA) and distal (dCCA) [74]. The initiation of CCA is associated with the malignant transformation of biliary epithelial cells.

MSI was employed to explore sulfatide abundance and composition in iCCA tissue [73]. The results revealed the presence of sulfatides in the iCCA tumor zone, with sulfatide intensity per pixel similar to that of the bile ducts. Although clinical outcomes and iCCA tumor biology correlated with sulfatide characteristics, no significant associations were found between total sulfatides intensity and overall or disease-free survival, or tumor stage. Interestingly, a higher proportion of unsaturated over saturated sulfatide species was associated with lower disease-free survival of iCCA patients. Patients with a high ratio showed earlier tumor recurrence (10 months) compared to patients with a low ratio (20 months) [73].

GAL3ST1, the main enzyme involved in sulfatide synthesis, has also been shown to be up-regulated in human CCA tissue as well as in human CCA cell lines [15]. Furthermore, GAL3ST1 deficiency using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) Cas technology in the human dCCA TFK1 cell line reduced the tumorigenic capacity and partially recovered the epithelial identity of the cells. In this study, sulfatide deficiency was observed to decrease the proliferative and clonogenic capacity of TFK1 cells. Sulfatide deficiency reduced the glycolytic activity and increased the expression of epithelial markers of TFK1 cells, which consequently increased transepithelial resistance and reduced the permeability of polarized cultured cells [15]. Disruption of sulfatide synthesis in TFK1 cells suggested an anticancer effect, manifested by reprogramming of energy metabolism and reversal of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) with recovery of barrier function. However, these findings need to be extended to more cell lines and in vivo models but sulfatides could be a new target for the treatment of CCA.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common type of cancer globally [75]. Sulfatide is abundant in basal crypt epithelium and surface epithelium of healthy colon tissue, while elevated expression of sulfatides was found in CRC tissue and cell lines derived thereof [76]. The liver is the main organ affected by CRC metastatic spread, and more than half of CRC patients will develop liver metastasis over the course of the disease [77]. A study by Morichika et al. [78] investigated the relationship between sulfatide composition and the malignant potential of CRC. Using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and immunostaining, the study designated sulfatide as two distinct bands: cerebroside sulfated ester (CSE)-A and CSE-B. No statistically significant difference was observed in the total levels of CSE between cancerous tissue and normal tissue. However, CSE-A levels were significantly lower, while CSE-B levels were significantly higher in cancerous tissue compared to normal tissue. This shift indicated alterations of sulfatide composition in cancerous tissues, characterized by a reduction in nonpolar band (CSE-A) and an increase in the polar band (CSE-B). And higher CSE ratios (CSE-B/[CSE-A + CSE-B]) were correlated with lymph node metastasis of CRC [78].

The recent MSI study revealed that total sulfatide intensity in the CRLM tumor area was significantly higher than in the tumor area of HCC and iCCA, as well as normal bile ducts [73]. All structural classes of sulfatides contributed to this elevation. However, there were no significant associations between sulftiade composition and overall or disease-free survival in the CRLM patients [73]. Without further information regarding the specific concentration or functional implications of sulfatides, the significance of these alterations remains unclear. Future research, potentially including quantitative analysis of sulfatide content in small biopsy samples, could offer predictive insights into the malignancy potential of CRLM. Further studies are needed to determine the precise role of sulfatides in CRLM progression and metastasis.

The presence of sulfatides in the liver has been known for decades, but the functional roles of sulfatide species in the liver are mainly unknown. There is evidence that sulfatides are involved in liver physiology and pathobiology in different aspects, as summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [5, 14, 15, 41, 50, 56, 70, 71, 72, 73, 78]). The ability of sulfatide-mediated activation of type II NKT cells regulates the immune response in the liver and is potentially implicated in many liver diseases. The development of mass spectrometry offers good opportunities for lipid research, including the accurate measurement of sulfatides. The localization of sulfatides in the bile ducts indicates that sulfatides are a biomarker of cholangiocytes, and the level of sulfatides appears to exist a relationship between different stages of PSC. Oxidative stress or PPAR

| Authors | Year | Model | Key findings | Liver disease | Reference |

| Maricic I. et al. | 2015 | Mice | Sulfatides showed a protective role in animal models of ArLD by the inhibition of type I NKT cells that blocks the pro-inflammatory response and neutrophils recruitment in liver parenchyma. | ArLD | [41] |

| Arrenberg P. et al. | 2011 | Mice | Sulfatides pretreatment in a mouse model of hepatic ischemic reperfusion injury results in an immunomodulatory response, which shows a reduced inflammatory response. | Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury | [5] |

| Sebode M. et al. | 2019 | Human blood and liver | Sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells are abundant in the human liver and show a pro-inflammatory phenotype in AIH patients. Type II NKT cell activation mediated by sulfatides activates a pro-inflammatory cascade that can contribute to disease pathogenesis. | AIH | [50] |

| Alpa M. et al. | 2008 | Human plasma | Elevated titers of both anti-ganglioside GM1 and anti-sulfatide antibodies were detected in the plasma of several patients with HCV-associated IgM κ/IgG mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC). | Hepatitis C | [56] |

| Flinders B. et al. | 2018 | Human tissue | Sulfatides are restricted to the biliary tract in the healthy liver by MSI. A similar distribution of sulfatides in the liver from PSC patients with a mild clinical phenotype as in the healthy liver. In contrast, sulfatides were virtually absent in the liver of patients with advanced PSC. | PSC | [14] |

| Dong Y. W. et al. | 2014 | Human tissue | Sulfatides were found upregulated in HCC tissue and present in different HCC cell lines, which serve as an adhesion molecule on the membrane of HCC cells. | HCC | [70] |

| Zhong Wu X. et al. | 2004 | HCC cell line | The level of sulfatides expression was positively correlated with metastatic potential in different HCC cell lines. | HCC | [71] |

| Tian Y. et al. | 2016 | Mice | Sulfatide contents in the liver were age-dependently increased, together with both oxidative stress and PPAR | HCC | [72] |

| Huizing L. et al. | 2023 | Human tissue | Sulfatides were found in HCC tissue, but the main type, the odd-chain hydroxylated ST-OH [37:1], differs from those in normal bile ducts, iCCA, or CRLM. In contrast, the dominant sulfatide type in normal bile ducts, iCCA, and CRLM, the hydroxylated ST-OH [42:1], is nearly absent in HCC tissues. No link was found between sulfatide composition and survival rates in HCC patients. | HCC | [73] |

| Huizing L. et al. | 2023 | Human tissue | The presence of sulfatides in the tumor area of iCCA, with sulfatide intensity per pixel similar to that in bile ducts. A higher ratio of unsaturated over saturated sulfatide species was associated with decreased disease-free survival of iCCA patients. | CCA | [73] |

| Chen L. et al. | 2024 | CCA cell line | GAL3ST1 is upregulated in human CCA. GAL3ST1 deficiency reduced tumorigenic capacity and partially recovered the epithelial identity of CCA cells. | CCA | [15] |

| Morichika H. et al. | 1996 | Human tissue | Changes in sulfatide composition may play an important role in lymph node metastasis of colorectal adenocarcinoma. | CRLM/CRC | [78] |

| Huizing L. et al. | 2023 | Human tissue | Total sulfatide intensity was much higher in the CRLM tumor area compared to HCC, iCCA, and normal bile ducts. Sulfatide composition did not significantly affect overall or disease-free survival in CRLM patients. | CRLM | [73] |

ArLD, alcohol related liver disease; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; MSI, mass spectrometry imaging; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgM

Conceptualization, GAS, LC and ME; Literature Search, GAS, LC and ME; Writing—Original Draft, GAS and LC; Figure Design and Creation, LC and GAS; Writing—Review & Editing, GAS, LC and ME. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and instruction provided by Professor Steven W. M. Olde Damink and Dr. Frank G. Schaap from the Department of Surgery, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

L.C. was supported by the Chinese Scholarship Council, grant number 201607040063, and G.A.S. was funded by the European Association for the Study of the Liver, EASL Sheila Sherlock Fellowship.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.