1 Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, 030032 Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

2 Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, 030032 Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

Abstract

Since the discovery of the Musashi (MSI) protein, its ability to affect the mitosis of Drosophila progenitor cells has garnered significant interest among scientists. In the following 20 years, it has lived up to expectations. A substantial body of evidence has demonstrated that it is closely related to the development, metastasis, migration, and drug resistance of malignant tumors. In recent years, research on the MSI protein has advanced, and many novel viewpoints and drug resistance attempts have been derived; for example, tumor protein p53 mutations and MSI-binding proteins lead to resistance to protein arginine N-methyltransferase 5-targeted therapy in lymphoma patients. Moreover, the high expression of MSI2 in pancreatic cancer might suppress its development and progression. As a significant member of the MSI family, MSI2 is closely associated with multiple malignant tumors, including hematological disorders, common abdominal tumors, and other tumor types (e.g., glioblastoma, breast cancer). MSI2 is highly expressed in the majority of tumors and is related to a poor disease prognosis. However, its specific expression levels and regulatory mechanisms may differ based on the tumor type. This review summarizes the research progress related to MSI2 in recent years, including its occurrence, migration mechanism, and drug resistance, as well as the prospect of developing tumor immunosuppressants and biomarkers.

Keywords

- Musashi-2

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- cancer

- epithelial–mesenchymal transition

Musashi (MSI) was first described in 1994 in a paper investigating the role of asymmetric divisions in sensory organ precursor cells in Drosophila [1]. Loss of the MSI gene leads to asymmetric division of Drosophila neuroblasts, ultimately producing a double-bristle phenotype. The gene is called Musashi because of its similarity to the famous fighting sword stance pioneered by the Japanese national hero Miyamoto Musashi. Mammals have two homologous genes of MSI, MSI1 and MSI2, both of which are highly conserved in evolution. The proteins they encode belong to the same family of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and participate in mRNA regulation after transcription to regulate gene expression [2]. They primarily target developmental transcription factors and cell cycle regulators, which are also expressed in stem cells (SCs) and are associated with the invasive behavior of tumors [3]. The MSI2 protein has a binding domain and auxiliary domain. The binding domain is located at the N-terminus and is highly conserved among species. The C-terminus is the auxiliary domain, and its protein sequence regulates gene expression by mediating protein–protein interactions to promote or inhibit protein translation [4]. The MSI2 RBP is mainly found in the cytoplasm but can also be found in the nucleoplasm [5].

In the more than 20 years since discovery of the MSI gene, progress has been made in many aspects and fields. For example, a study on mouse spermatogonia found that MSI plays a role in spermatogenesis and germline SC development [6]. After knocking out the MSI2 gene, the division frequency of hematopoietic SCs and progenitor cells was found to be significantly reduced [7]. In a mouse model with MSI2 overexpression, the division frequency of hematopoietic SCs and progenitor cells was significantly increased [8]. In 2003, Barbouti et al. [9] first reported that patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) have MSI2 gene rearrangement, forming the MSI2/homeobox A9 fusion protein; however, the mechanism is unclear. In subsequent years, the role of MSI2 in malignant vascular tumors has been widely confirmed. Overexpression of MSI2 can promote the occurrence and progression of hematological malignancies [10, 11, 12]. The occurrence of tumors is related to the abnormal division and differentiation of SCs. MSI2 not only affects the division of SCs but also affects the metastasis of tumors. Therefore, the mechanism of action of MSI2 in multisystem tumors is of great research value, as it could lead to the development of specific tumor-targeted drugs. MSI protein is believed to be highly expressed in tumor cells and is associated with poor differentiation, poor prognosis, lymphatic invasion and metastasis of solid tumors, and expression of other SC markers.

Understanding how MSI regulates cancer-related gene expression under physiological conditions and its possible therapeutic effects requires an understanding of its structure and biochemical functions. MSI belongs to the A/B type heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) with two N-terminal RNA recognition domains (RRMs), of which RRM1 plays a major role and RRM2 is auxiliary. These domains are highly conserved in different species. MSI binds to specific mRNA sequences through these domains, among which interaction with sequences such as ACCUUUUUUUAGAA is preferential. In addition, the C-terminus of MSI contains sequences that interact with other proteins and can affect the translation process. Recent study has also shown that MSI may be involved in regulating Lin-28 homolog A (Lin28A) and affecting the alternative splicing process. Considering its dual regulatory functions and the influence of other proteins on the cellular environment, MSI may exhibit different activities in different cellular environments, which poses a challenge for its potential application in cancer treatment [13].

Leukemia is a type of malignant clonal disease of hematopoietic SCs. Clonal leukemia cells proliferate and accumulate in large quantities in the bone marrow and other hematopoietic tissues due to mechanisms such as uncontrolled proliferation, differentiation disorders, and blocked apoptosis. The MSI2 protein affects the characteristics of cell division and differentiation. It has been confirmed that it is closely related to the malignant proliferation of hematopoietic SCs in the blood system, and MSI2 is highly expressed in leukemia. In 2010, Ito et al. [7] first verified the overexpression of MSI2 in CML using a mouse model. Subsequently, Kharas et al. [8] demonstrated that overexpression of MSI2 is a key factor leading to the proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis in myelogenous leukemia (ML) cell lines. In recent years, substantial progress has been made in studying the intrinsic influence mechanism between various types of leukemia and MSI2. The bidirectional combination mechanism of genes and proteins and confirmation of the clear relationship between RBPs and the stemness and proliferation of tumor cells have also helped clarify the role of MSI2-binding proteins in leukemia. At the same time, some novel targets of MSI2-binding proteins have also been discovered, such as the fms-related receptor tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene; with loss of the MSI2 gene, the protein expression of FLT3 is also down regulated and the apoptosis of leukemia cells is accelerated. This mechanism is relatively unique in the growth process of acute ML (AML) cells [14]. Interleukin 6 cytokine family signal transducer (IL6ST) is a binding and regulatory target of MSI2. IL-6 is a type of IL6ST, which stimulates MSI2 knockdown cells to cause hyperphosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2); however, at present, the binding partner of MSI2-binding protein has not been clearly identified [15]. Inhibiting RNA-binding activity is a novel way to treat leukemia. For example, Minuesa et al. [16] used molecular chemistry methods to verify that Ro 08-2750 (Ro) can be used as an MSI2 RNA-binding inhibitor. When Ro is reduced and combined with high-affinity chemicals such as nerve growth factor, Ro no longer binds to MSI2, reducing its tumor suppressor effect. This can undoubtedly be used as a new treatment paradigm.

In AML, MSI2 expression is elevated in patients with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (CEBPA) mutations. It is worth noting that patients with CEBPA mutations alone have a good prognosis, while the high expression of MSI2 leads to a poor prognosis, which also indicates that other gene mutations affect the expression of MSI2 [17]. Branched-chain amino acid metabolism activated by the MSI2-branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1) axis promotes cancer progression in ML, and knockdown of MSI2 reduces the levels of BCAT1 protein and phosphorylated p70 S6 kinase [18]. New research methods have also been discovered. For example, Nguyen et al. [19] used Hyper Targets of RNA-binding proteins Identified By Editing (HyperTRIBE) to discover that MSI2 RNA-binding activity in leukemia SCs (LSCs) is enhanced and regulated in different ways. An MSI2 mouse model has also been developed to identify LSCs [20]. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), MSI2 was found to be upregulated in newly dividing CLL cells [21]; in other cases, it inhibits or induces protein translation to regulate gene expression. These different modes of expression make the mechanism of action of MSI2 more complicated, which is also worth further study and consideration. In MCL cell lines, SRY-box transcription factor 11 (SOX11) directly regulates the transcription of MSI2 in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) cells; the mRNA and protein expression of MSI2 increases with an increase in SOX11 expression, and conversely decreases [22].

Regarding the therapeutic potential of MSI2 in the hematopoietic and lymphoid system, a study has shown that MSI2 affects the growth and survival of CLL cells and is associated with a poor clinical course and prognosis [21]. In 2017, Vu et al. [23] found that synaptotagmin-binding, cytoplasmic RNA-interacting protein (SYNCRIP) and MSI2 share the same mRNA targets and influence each other, making the ribosome network a possible target for leukemia treatment. Subsequently, related chemical drug inhibitors were discovered. For example, quinacrine (QC) can downregulate the expression of MSI2 and upregulate the expression of Numb to induce diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells to arrest in the G0/G1 cycle [24], and it also has anticancer effects. Using potential MSI2 antagonists to explore traditional Chinese medicine antagonists is also a new approach [25]. The study on chemotherapy resistance have found that MSI2 is an informative biomarker and novel therapeutic target for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), which can promote the proliferation of T-ALL and promote chemotherapy resistance through the post-transcriptional regulation of Myc [26]. Tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutations and the RBP MSI2 contribute to resistance to protein arginine N-methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5)-targeted therapy in patients with B-cell lymphoma [27].

MSI2 not only plays a role in the occurrence and development of leukemia and glioblastoma but also has a close relationship with multiple malignant solid tumors, and it can promote or inhibit their occurrence and progression. Solid malignant tumors include primary liver cancer (LC); cholangiocarcinoma; pancreatic, gastric, duodenal, colon, rectal, kidney, ureteral, ovarian, bladder, and adrenal cancers; and malignant lymphoma originating in the abdominal cavity. Due to the relative intractability of solid malignant tumors, it is difficult to obtain specific and effective treatment. In recent years, the correlation between abdominal malignant tumors and MSI2 and its mechanism of action have been frequently mentioned, and related research has also progressed, providing a molecular basis for seeking specific treatment (Table 1, Ref. [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]).

| Cancer | MSI2 protein expression | Association | |

| Tumor surrounding the tissue | Tumor tissue | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | - | + | Poor prognosis [28] |

| Pancreatic cancer | - | + | Poor prognosis [29, 31] |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | - | + | Poor prognosis [30] |

| Gastric cancer | - | + | Poor prognosis [32] |

| Breast cancer | - | + | Poor prognosis [33] |

| Renal cell carcinoma | ? | + | Poor prognosis [34] |

“+” Significantly high expression; “-” No expression or low expression; “?” unidentified. MSI, Musashi.

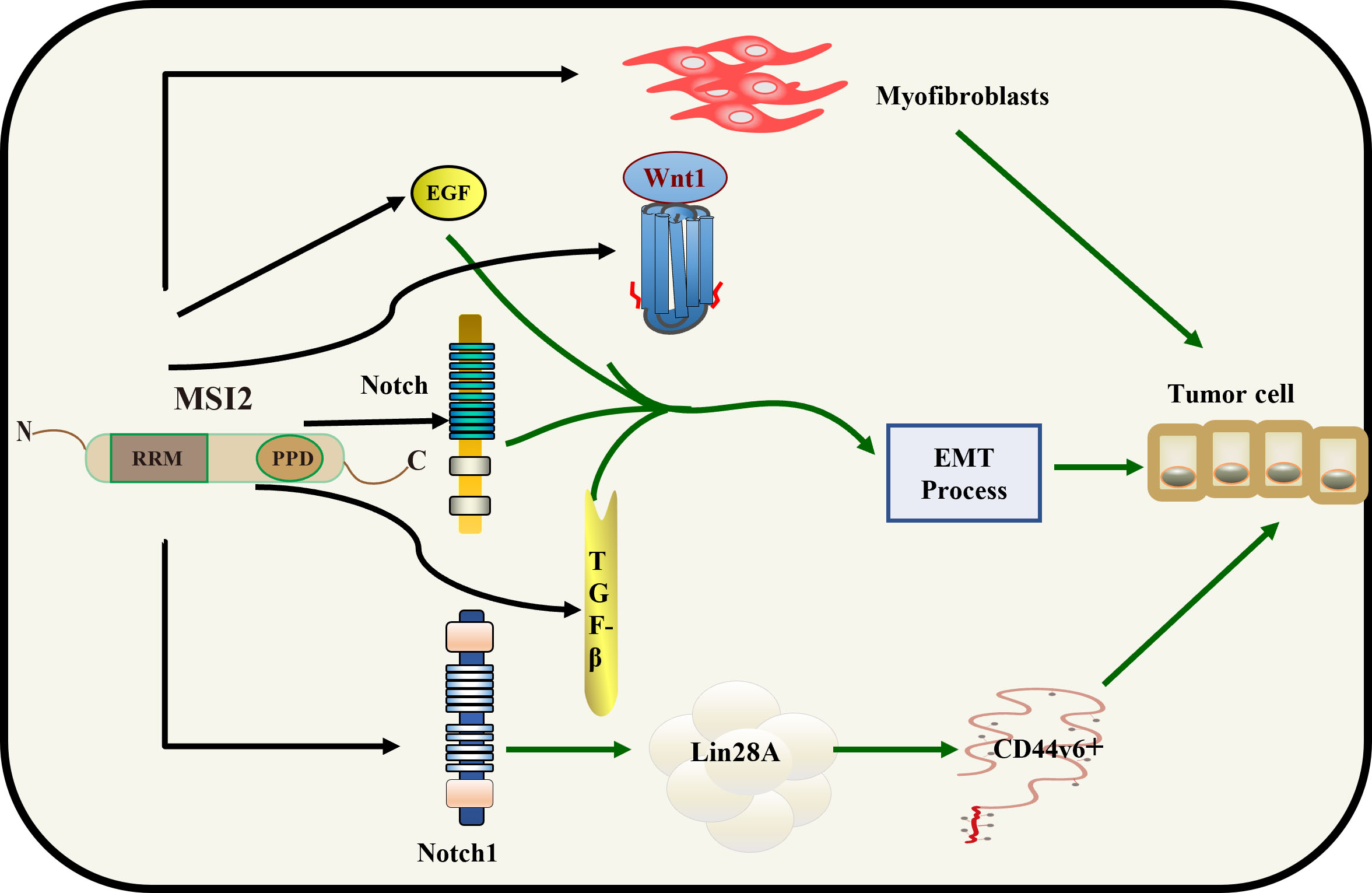

In the nearly 10 years since discovery of the MSI gene, a study has shown that MSI1 and MSI2 are significantly overexpressed in LC and are not detected in normal liver tissue specimens. However, only the high expression of MSI2 is associated with a poor prognosis. MSI2 may induce the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Tumor EMT is closely related to the metastasis and invasion ability of tumors. Knockout of MSI2 significantly reduces the invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells and changes the expression pattern of epithelial–mesenchymal markers [28]. Together, these results suggest that MSI2 is associated with the EMT and has the potential to be a biomarker for HCC prognosis and invasion; however, the specific mechanism underlying the association between MSI2 and the EMT has not yet been elucidated. The study has explored the mechanism by which MSI2 is affected by various signaling pathways in the tumor EMT. MSI2 indirectly or directly positively regulates epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-

In 2021, the study of the SOX2-overlapping transcript (OT) signaling pathway showed that SOX2-OT is highly expressed in HCC cells and tissues, and HCC patients with high SOX2-OT expression have a poor prognosis. Downregulation of SOX2-OT could inhibit the malignant behavior of HCC cells. SOX2-OT binds to microRNA 143-3p (miR-143-3p) to promote MSI2 expression, and downregulation of miR-143-3p or upregulation of MSI2 could prevent the effects of si-SOX2-OT in HCC cells. SOX2-OT inhibits the targeted inhibition of MSI2 by miR-143-3p through competitive binding with miR-143-3p, thereby promoting the expression of MSI2 and the proliferation, invasion, and migration of HCC cells [39]. The occurrence of HCC is not only related to many signaling pathways but may also be related to the occurrence and progression of pre-existing diseases. It has been shown that the upregulation of MSI2 in hepatitis B virus-related LC is correlated with the expression of

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Mechanistic role of MSI2 in HCC. MSI2 promotes the proliferation of myofibroblasts and directly regulates the EGF, TGF-

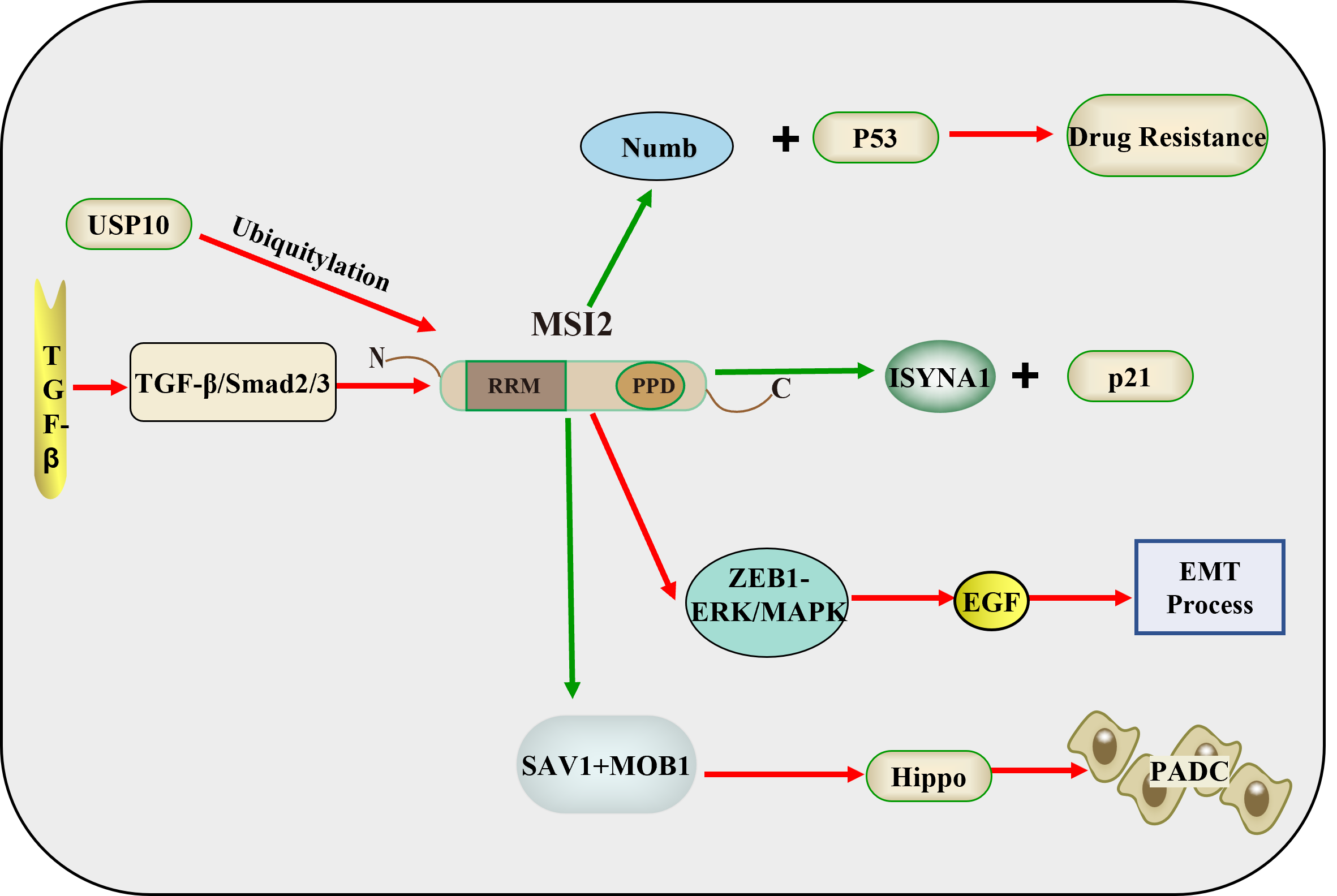

A further understanding of tumor biology and the development of molecular markers detectable in circulation and cancer tissues may underlie the development of new tools to optimize diagnosis and treatment. In gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer (PC), all seven differentially expressed mRNAs (DEmRNAs) have significant effects on cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) memory T cells, which are affected by the effects of gemcitabine treatment. MSI2 is one of the DEmRNAs that also have significant effects on CD4 effector memory T cells, which predicts a good prognosis [41]. MSI2 promotes chemoresistance and malignant biology in PC by downregulating Numb and p53 [42]. Afterwards, the research group made some first discoveries about MSI2 in the carcinogenic mechanism of PC. The results of the study on MSI2 promoting EGF-induced EMT in PC through zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1)-ERK/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling showed that EGF enhanced EGF receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation, induced EMT, and activated ZEB1-ERK/MAPK signaling in two PC cell lines. MSI2 silencing reversed the functions of EGF stimulation, including inhibition of EGF-promoted EMT-like cell morphology and EGF-enhanced cell invasion and migration. At the same time, MSI2 silencing inhibited EGF-enhanced EGFR phosphorylation at tyrosine 1068 and reversed EGF-induced EMT and changes in key proteins in ZEB1-ERK/MAPK signaling (ZEB1, E-cadherin, zonula occludens-1,

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Mechanistic role of MSI2 in PC and CRC. USP10 promotes MSI2 ubiquitination and the TGF-

Gastric cancer (GC)-related genes regulating malignant phenotypes are potential therapeutic targets for GC treatment [44]. Currently, MSI2 has been found to be a marker of SCs and progenitor cells, and is closely related to the occurrence and development of tumors. MSI2 mRNA expression levels are associated with invasion depth, tumor lymph node metastasis stage, degree of differentiation, and tumor size, but not with sex, age, tumor location, or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 expression [32]. This study showed that increased expression of MSI2 leads to a poor prognosis in GC patients. Although cisplatin drugs have a certain effect on early and late-stage GC, resistance to cisplatin is still an important factor affecting the prognosis of GC. There is increasing evidence that long noncoding RNA is closely related to resistance to chemotherapy drugs. LINC00942 (LNC942) destroying the LNC942-MSI2-c-Myc axis may be a new treatment strategy for GC patients with chemotherapy resistance [45]. MSI2 mRNA is a prognosis-related gene in GC and is involved in the construction of weighted correlation network analysis, which may also provide new insights into the treatment of GC [46].

MSI2 is currently considered a potential therapeutic target for a variety of malignant tumors. In 2020, it was discovered that MSI2 may be a predictor of colorectal cancer (CRC) and play an important role in the pathogenesis of CRC [47]. Subsequent study has also confirmed that MSI2 expression increases during CRC progression and is associated with poor prognosis; depletion of MSI2 reduces the growth of CRC cells [48]. MSI2 acts as a relay point, and upstream or downstream regulatory factors targeting MSI2 can be found. It has been found that ubiquitin-specific protease 10 (USP10) can pantothenate MSI2, and after USP10 is knocked out, the proliferation of CRC cells is inhibited [49]. It has also been found that gossypol can be used to develop molecular therapies to modulate MSI1/MSI2 overexpression in CRC [50]. Small molecule bamipines may serve as direct and functional MSI2 antagonists for cancer therapy [51]. TGF-

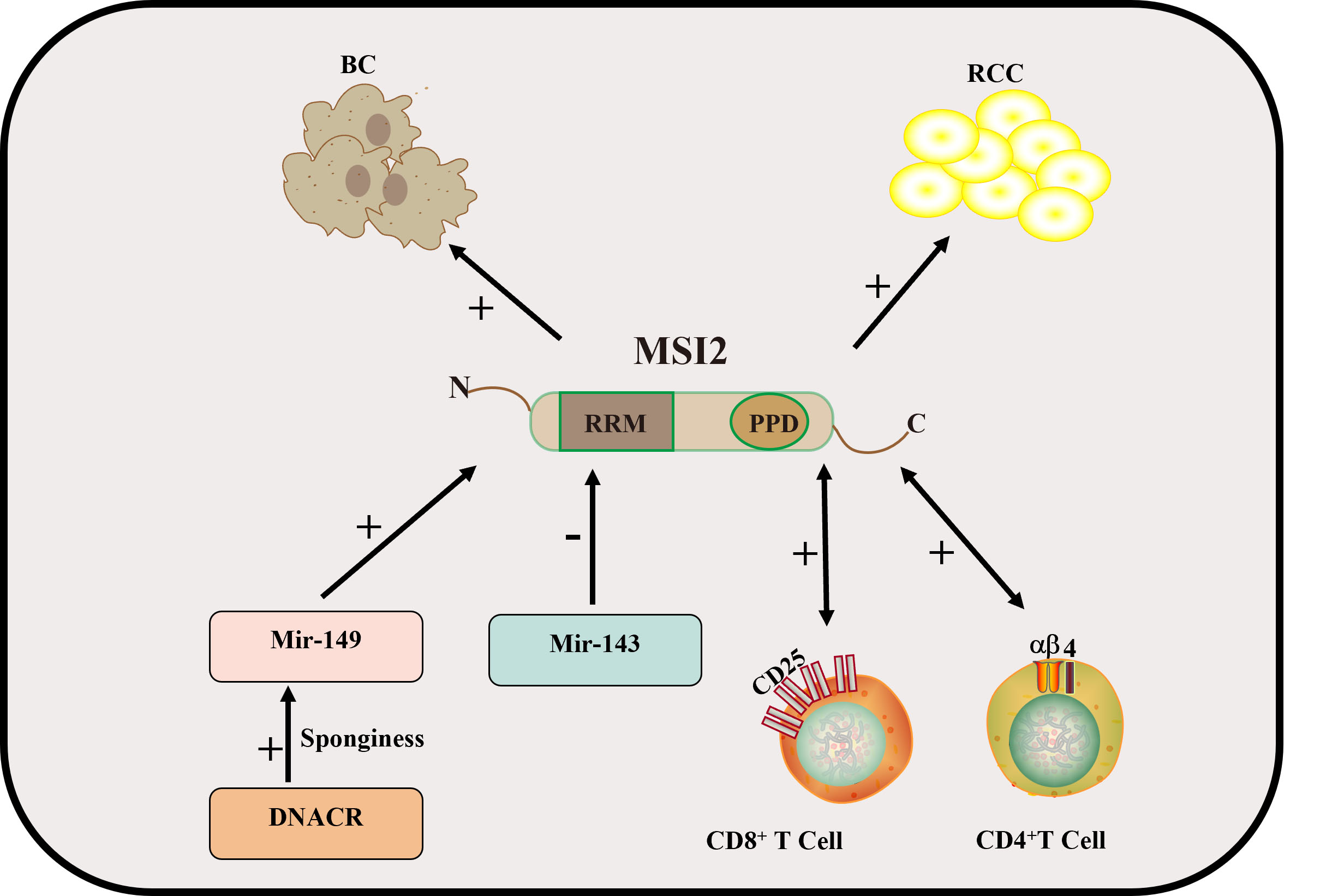

As early as 2013, data showed that MSI1 was highly and indifferently expressed in both bladder tumor tissue and apparently normal bladder tissue, and when quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) control experiments were performed using primers specific for MSI1 and TATA box-binding protein, MSI1 was found to be expressed at relatively high levels in all tumor and nontumor bladder tissue specimens examined [55]. At present, there is still controversy about the correlation between MSI1 and bladder tumors. In 2016, a detailed study was conducted on the mechanism of MSI2 in the occurrence and development of bladder tumors [12]. The statistical analysis of this study showed that MSI2 expression was significantly correlated with the clinical advanced stage of bladder tumors, lymph node metastasis, and poor prognosis. Overexpression of MSI2 promoted the migration and invasion of bladder cancer (BC) cells. By contrast, knockout of MSI2 inhibited the migration and invasion of BC cells. MSI2 regulates the metastasis and invasion of BC by activating the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/STAT3 pathway and promoting the expression of JAK2/STAT3 downstream genes in BC. MSI2 may be a valuable prognostic detection marker [33]. Subsequently, in 2018, Zhan et al. [56] found that differentiation antagonistic non-protein nodule RNA (DANCR) is mainly distributed in the cytoplasm. DANCR acts as a microRNA (miRNA) sponge, which positively regulates the expression of MSI2 by sponging miR-149, thereby promoting the malignant phenotype of BC cells, thus playing a carcinogenic role in the pathogenesis of BC [56]. MSI2 is an RBP that regulates the stability and translation of certain mRNAs. In 2019, a study showed that synthetic miR-143 negatively regulates the RBP MSI2 in BC cell lines. The study showed that MSI2 positively regulates the expression of Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) by directly binding to the target sequence of KRAS and promoting its translation [57] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Mechanism of MSI2 in BC and kidney cancer. In kidney cancer, CD4 and CD8 T cells positively regulate MSI2. MSI2 regulates the JAK2/STAT3 pathway to promote the occurrence and development of BC. MiR-149 and MiR-143 regulate MSI2 to promote the progression of BC. In the figure, “+” indicates an upward adjustment and “-” indicates a downward adjustment. CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; BC, bladder cancer; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; DNACR, differentiation antagonistic non-protein nodal RNA; JAK2/STAT3, Janus tyrosine Kinase 2/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3.

Regarding the treatment of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), with the development of combined therapy in recent years, it has obvious clinical effects; however, patients still do not achieve good treatment effects [58]. With the discovery of MSI2 in other malignant tumors and its potential as a test indicator for malignant tumors, researchers studying renal cancer have also become interested in MSI2. Li et al. [59] first discovered that the expression of MSI2 is associated with immune infiltration in advanced ccRCC, especially with CD4 and CD8 T cells. The expression signature of MSI2 can be used as a new indicator to predict the clinical outcomes of patients with advanced ccRCC, and will help us further explore the role of cellular metabolic reprogramming and immune infiltration in advanced ccRCC. In addition, it was innovatively discovered that patients with MSI2 overexpression are more sensitive to sorafenib, sunitinib, and gefitinib because the expression levels of immunosuppressive factors are very low in these tumors. Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare but highly aggressive adrenocortical cancer with a poor prognosis. Although rare, completely resected ACC has a high risk of recurrence. MSI2 is considered to be a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for many cancers. The study has also shown that MSI2 has value as a prognostic marker for completely resected ACC and has strengthened research on its role as a possible therapeutic target for patients with ACC [34] (Fig. 3).

With the in-depth study of the mechanism of MSI2 and tumors, it has been found that MSI2 promotes the proliferation and division of tumor cells in other tumors. In lung cancer, it has been confirmed that MSI2 promotes the malignant progression of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). ETS variant transcription factor 4 (ETV4) gene overexpression directly binds to the promoter region of MSI2 to regulate the transcription of MSI2 [60]. Then it was found that MSI2 protein expression is significantly increased in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) primary tumor samples compared with normal lung tissue [61]. The specific mechanism has also been newly discovered. MSI2 directly binds to the consensus motif in the EGFR mRNA, promoting the translation of the EGFR, thereby promoting the malignant progression of LUAD [62]. MSI2 directly positively regulates Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated protein expression and the DNA damage response to promote lung cancer [63]. It may also be pathway-related. Krüppel-like factor 4 can significantly inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and migration of NSCLC cells by inhibiting the MSI2/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway [64]. The latest study revealed that MSI2 plays an important role in cancer-associated fibroblast-mediated NSCLC cell invasion and metastasis through IL-6 paracrine signaling [65]. The therapeutic effect and drug resistance of MSI2 in lung cancer have also been further studied. Apigenin reprogrammed the alternative splicing of Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) death receptor 5 (DR5) and cellular-FADD-like IL-1β-converting enzyme (FLICE) inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) by interacting with hnRNPA2 and MSI2, resulting in increased DR5 protein levels and decreased c-FLIP protein levels, thereby enhancing TRAIL-induced apoptosis of primary lung cancer cells [66]. As aforementioned, MSI2 may have clinical value for NSCLC with EGFR mutations, and blocking MSI2 can enhance the activity of targeted inhibitors for NSCLC with EGFR gene mutations [62]. Overexpression of MSI2 can make parental cells resistant to gefitinib. In summary, targeting MSI2 in combination with EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors can effectively prevent the emergence of acquired resistance [67].

In breast cancer, MSI2 expression is highly enriched in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. MSI2 alters ESR1 by binding to specific sites in ESR1 RNA and increasing the stability of ESR1 protein, and promotes the progression of ER-positive breast cancer [68]. Choi et al. [69] discovered that MSI2 is a novel ubiquitination target protein of deficient breast cancer factor 2 (DBC2), and that MSI2 and DBC2 can directly interact to promote the polyubiquitination and proteasome degradation of MSI2 in breast cancer cells. Subsequent experiments showed that DBC2 can inhibit MSI2-related oncogenic functions and induce cell apoptosis. The expression of MSI2 is significantly downregulated in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tissues. MSI2a is a functional isoform of MSI2. Its expression inhibits the invasion of TNBC by stabilizing TP53INP1 mRNA and inhibiting the activity of ERK1/2 [70]. MSI-binding proteins are dysregulated in inflammatory breast cancer and are associated with tumor proliferation, CSC phenotype, and radio resistance [71].

In glioma, the positive feedback loop of MSI2-TGF

In recent years, the study has found that MSI2 is also expressed in ovarian cancer (OC), and its mRNA-binding protein is highly expressed in cervical cancer (CC) tissues, leading to a poor prognosis [76]. The mechanism may be that MSI2 promotes CC cell growth, invasiveness, and spheroid formation by directly binding to c-Fos mRNA and increasing c-Fos protein expression. In this study, it was also found that p53 can reduce the expression of MSI2 by increasing the level of miR-143/miR-107, thereby reducing the poor prognosis. There are also studies showing that MIR4435-2HG knockout inhibits CC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by regulating the miR-128-3p/MSI2 axis [77]. miR-149 exerts anti-OC effect by regulating MSI2 through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT [78]. In general, the study of miRNA provides a possible treatment strategy and a new research direction for CC.

We have delineated the expression and role of the MSI2 gene and regulatory protein in diverse tumors; however, certain disparities exist concurrently. For example, the expression of MSI2 in leukemia and abdominal malignancies exhibits the following similarities and dissimilarities. There is high expression of MSI2 in leukemia, particularly AML, and the expression of MSI2 is frequently clearly elevated and is associated with adverse disease progression and prognosis. The expression of MSI2 in abdominal malignancies demonstrates variability; for example, in LC, PC, GC, and CRC, there is a certain degree of variation in the expression level of MSI2. Moreover, in some types of abdominal tumors, the expression of MSI2 is also significantly augmented and is associated with the malignancy degree of the tumors and poor prognosis. The role of MSI2 in leukemia cells primarily encompasses maintaining the self-renewal of leukemia SCs and promoting cell proliferation, and influencing cell proliferation by regulating several signaling pathways including the STAT3 and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. The role of MSI2 in abdominal malignancies involves promoting the proliferation, migration, and invasion ability of tumor cells, as well as maintaining the properties of CSCs, which also operates by regulating multiple signaling pathways such as Notch, Wnt, and Hippo. MSI2 has been less investigated in abdominal malignancies compared to leukemia, but existing research indicates that MSI2 might be an important regulator and potential therapeutic target for these tumors.

Although MSI2 is highly expressed in both leukemia and abdominal malignancy and is associated with a poor disease prognosis, its specific expression level and regulatory mechanism may vary with different tumor types. In leukemia, MSI2 is mainly related to the maintenance of SCs and cell proliferation, while in abdominal malignancies, MSI2 may be more implicated in the proliferation, migration, and invasion of tumor cells. Overall, the role of MSI2 in these diseases renders it an important subject of study and potential therapeutic target.

In the human body, MSI2 affects the occurrence and progression of a variety of tumors, it encompasses diseases of the blood system and common solid tumors in the abdomen such as leukemia, lymphoma, HCC, PC, kidney cancer, stomach cancer, glioblastoma, breast cancer, tumors of the female reproductive system, lung cancer, and CRC. In leukemia, MSI2 primarily maintains the self-renewal of leukemia SCs and promotes cell proliferation and influences the cell cycle by regulating signaling pathways. In lymphoma, MSI2 can facilitate the proliferation of T-ALL through post-transcriptional regulation of Myc, and in combination with TP53 mutants, leads to drug resistance in patients with B-cell lymphoma. High expression of MSI2 leads to poor prognosis of HCC, CRC, GC, BC, and renal cancer, while high expression of MSI2 in PC may inhibit the occurrence and development of cancer. In liver cancer, MSI2 affects the occurrence and progression of cancer by regulating the EGF, TGF, Notch and Wnt pathways to promote the EMT process, but the specific mechanism is still unclear. In PC, MSI2 is regulated through various pathways, thereby promoting the EMT pathway or affecting the drug resistance and poor prognosis of tumors. Studies have also demonstrated that a high expression level of MSI2 in PC results in a more favorable prognosis. In CRC and BC, MSI2 can serve as an intermediate target for upstream regulation, thereby regulating downstream pathways. All of these indicate that the process of cancer occurrence and development can be affected by controlling MSI2, and it may also serve as a specific marker for tumor detection, prognosis, and recurrence. Of course, there are still many areas that have not been clearly elucidated, and it still has great potential research value.

In summary, the research progress on MSI2 has a clear relationship with the proliferation and differentiation of cancer, and affects the drug resistance and stemness of various malignant tumors. Its mechanism not only acts on the MSI2 gene coding sequence (e.g., MSI2 directly binds to the consensus motif in EGFR mRNA, promotes EGFR translation, and thus promotes the malignant progression of LUAD), and acts on its transcribed mRNA (e.g., in OC, MSI2 promotes CC cell growth, invasiveness, and globular formation by directly binding to c-Fos mRNA and increasing c-FOS protein expression), and is more likely to act on the ribosome (e.g., SYNCRIP and MSI2 share the same ribosome network target and influence each other). MSI2 indirectly or directly affects the synthesis of small molecules to regulate pathways, and ultimately affects the division of tumor cells, or affects the migration and invasion of tumors by acting on the EMT. These can prove the feasibility of using MSI2 as a target, and unique molecular inhibitors can be developed for different mechanisms and pathways in each tumor. However, it is worth mentioning that in the process of tumor migration and metastasis, the only clear mechanism of action may be EMT, and the mechanism affecting distant metastasis has not yet been elucidated. Better research methods may obtain previously undiscovered mechanisms, such as network data analysis, and we also look forward to technological innovations in MSI2 gene research.

The mechanism of MSI2 resistance to tumors has been extensively studied. For example, TP53 mutations and MSI2 binding proteins induce lymphoma patients to develop resistance to PRMT5 targeted therapy. The RBP MSI2 sustains the growth and leukemogenic potential of MLL-rearranged ALL, and is involved in glucocorticoid resistance [79]. However, it seems that drug inhibitors based on the action of MSI2 are still in the theoretical stage. For example, QC can downregulate the expression of MSI2 and upregulate the expression of Numb to induce lymphoma cells to stagnate in the G0/G1 division cycle, but clinical trials have not yet been conducted for verification. The findings described above show that the regulatory mechanism of MSI2 in various tumors span several signaling pathways. Key signaling pathways include the classic Notch signaling pathway, Wnt/

Under the influence of these mechanisms, the clinical treatment of these cancer patients should be personalized and combined. In early cancer diagnosis, MSI2 exhibits potential due to its involvement in maintaining cancer cell stemness and proliferation. This encompasses the utilization of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and miRNA as biomarkers, providing minimally invasive options for detecting cancer-related genetic and molecular alterations, thereby enhancing early detection rates and patient outcomes. Platforms for miRNA assays and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) strategies have been developed to quantify miRNAs in clinical samples with the aim of identifying reliable biomarkers for early cancer screening [83]. According to the results of the MSI2 expression level in patients, personalized treatment may be developed; for example, patients with high MSI2 expression may be more sensitive to specific MSI2 inhibitors or combination therapy. To monitor the treatment effect, the expression of MSI2 before and after treatment can be detected. In addition to conventional anticancer chemotherapy drug therapy, some other targeted therapy strategies are also considered to be promising; for example, developing specific monoclonal antibodies against MSI2 protein to inhibit its function by blocking the binding of MSI2 to its RNA target. Specific anti-MSI2 antibodies can also be combined with cytotoxic drugs to target and kill cancer cells that express MSI2. RNAi is a good method in which small interfering RNAs are designed to specifically target MSI2 mRNA and degrade MSI2 mRNA through RNAi to reduce its expression. Short hairpin RNA is expressed using gene vectors that continuously interfere with MSI2 gene expression. Antisense oligonucleotides bind to MSI2 mRNA and prevent its translation, thus downregulating MSI2 protein expression.

In the above malignant tumors, MSI2 directly or indirectly regulates the occurrence and development of tumors, and its high expression is closely related to the poor prognosis of many cancers. MSI2 has great potential as a specific detection index for early tumor screening and diagnosis. Its high specificity and sensitivity make it expected to become an important tool in precision medicine, contributing to the early detection and accurate diagnosis of tumors, especially in noninvasive detection methods such as liquid biopsy, MSI2 has a particularly broad application prospect. At the same time, targeted therapy strategies for MSI2 also show high research value. Targeting MSI2 through various means such as small molecule inhibitors, antibody drugs, and RNAi is expected to significantly inhibit the growth and metastasis of tumor cells, thereby improving the efficacy of tumor therapy. To summarize, the versatility of MSI2 and key role in tumor biology make it a hot spot in tumor research. Future studies should continue to explore the molecular mechanism and clinical application potential of MSI2; promote its application in tumor screening, diagnosis, and treatment; and ultimately achieve accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment of tumor patients. This will lead to revolutionary breakthroughs in cancer research and clinical practice, and create a new era of cancer treatment.

ACC, Adrenocortical carcinoma; BC, Bladder Cancer; CML, Chronic myelogenous leukemia; CSCs, Cancer stem cells; CRC, Colorectal cancer; DANCR, Differentiation antagonistic non-protein nodal RNA; EGF, Epidermal growth factor; EMT, Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition; GC, Gastric cancer; HC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; ISYNA1, Inositol-3-phosphate synthase 1; MSI, Musashi; MSI1, Musashi-1; MSI2, Musashi-2; PC, Pancreatic cancer; PDAC, Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; RCC, Renal cell carcinoma; TGF-

YTN and YJL designed the research study. YTN and TZ searching and collating literature. YTN drawing figures. YTN, TZ and YJL wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and instruction from Dr Rui Li and Dr Panpan Zheng of the Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.