1 Department of Chemistry Education, Kongju National University, 32588 Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Chemistry, Kongju National University, 32588 Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea

Abstract

In recent years, the role of coenzymes, particularly those from the vitamin B group in modulating the activity of metalloenzymes has garnered significant attention in cancer treatment strategies. Metalloenzymes play pivotal roles in various cellular processes, including DNA repair, cell signaling, and metabolism, making them promising targets for cancer therapy. This review explores the complex interplay between coenzymes, specifically vitamin Bs, and metalloenzymes in cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Vitamins are an indispensable part of daily life, essential for optimal health and well-being. Beyond their recognized roles as essential nutrients, vitamins have increasingly garnered attention for their multifaceted functions within the machinery of cellular processes. In particular, vitamin Bs have emerged as a pivotal regulator within this intricate network, exerting profound effects on the functionality of metalloenzymes. Their ability to modulate metalloenzymes involved in crucial cellular pathways implicated in cancer progression presents a compelling avenue for therapeutic intervention. Key findings indicate that vitamin Bs can influence the activity and expression of metalloenzymes, thereby affecting processes such as DNA repair and cell signaling, which are critical in cancer development and progression. Understanding the mechanisms by which these coenzymes regulate metalloenzymes holds great promise for developing novel anticancer strategies. This review summarizes current knowledge on the interactions between vitamin Bs and metalloenzymes, highlighting their potential as anticancer agents and paving the way for innovative, cell-targeted cancer treatments.

Keywords

- cancer

- matrix metalloproteinases

- coenzymes

- metalloenzyems

- natural products

Vitamins are essential food nutrients that perform specific and vital functions in various body systems. They are classified based on their solubility as water-soluble (B and C complexes) (Fig. 1) and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) [1]. Water-soluble vitamins are essential organic compounds necessary for growth, development, and bodily functions. Unlike fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins dissolve in water and are readily absorbed into tissues for immediate use [2, 3]. However, they are not extensively stored in the body, emphasizing the need for a consistent dietary intake to maintain sufficient levels [3].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Structure of water-soluble vitamins.

Water-soluble vitamins are found abundantly in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fortified products, acting as coenzymes in biochemical reactions like energy metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, DNA synthesis, and exhibiting antioxidant functions [4]. The vitamin Bs, including thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pantothenic acid (B5), pyridoxine (B6), biotin (B7), folate/folic acid (B9), and cobalamin (B12), each contributes play a distinctive role in the bodily process [5, 6, 7]. Moreover, water-soluble vitamins, particularly vitamin C, possess antioxidant properties, combating oxidative stress [8].

Although classified as water-soluble, the solubility in water of these vitamins differs, leading to differences in absorption, excretion, and tissue storage. This could distinguish them from fat-soluble vitamins, which are metabolized and stored differently in the body [9]. Water-soluble vitamins are typically excreted in the urine of humans. Vitamin B1, B2, B6, B5, B7, and C are excreted in the urine mainly as free vitamins (rather than as coenzymes), while only a small amount of free vitamin B3 is excreted in the urine [9]. Understanding the roles and importance of water-soluble vitamins is crucial for maintaining optimal health.

In the context of diseases, particularly cancer, recent studies have shed light on the regulatory roles of various vitamin Bs and vitamin C in their treatments. These vitamins are increasingly recognized for their ability to modulate the activity of metalloenzymes involved in cancer progression and metastasis [10, 11, 12, 13]. For instance, vitamin C is a potent antioxidant which could neutralize harmful free radicals in the body [14, 15]. By scavenging these free radicals, vitamin C may help reduce oxidative stress and lower the risk of cancer initiation. Similarly, certain vitamin Bs, such as folate and cobalamin, are involved in one-carbon metabolism pathways that influence DNA synthesis and methylation, processes aberrantly regulated in cancer cells [16, 17, 18].

Furthermore, certain water-soluble vitamins have been demonstrated to regulate the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are associated with various diseases, including cancer, both directly and indirectly through different pathways [19, 20]. However, the amount of research in this area is still limited and further investigation is necessary. Understanding the intricate interplay between water-soluble vitamins and metalloenzymes, such as MMPs, in cancer regulation holds promise for the development of novel therapeutic strategies and personalized treatments for cancer patients.

MMPs are a class of proteases dependent on zinc for their activity. They can be activated by a diverse array of cytokines and growth factors [21]. These proteolytic enzymes share common functional domains and operate via a mechanism that involves the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components [22]. According to previous studies, MMPs are categorized based on their proteolytic substrate, which corresponds to specific extracellular matrix components they degrade. These classifications include collagenases (MMP-1 and MMP-13), gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), stromelysins like MMP-3, and membrane-bound MMPs [23]. Specifically, MMP-2 (also known as gelatinase A, 72 kDa) and MMP-9 (also known as gelatinase B, 92 kDa) consist of three domains, with a type II additional fibronectin domain inserted into the catalytic domain. These enzymes can degrade various extracellular matrix components including collagen, elastin, fibronectin, gelatin, and laminin [24, 25, 26].

MMPs play indispensable roles as regulators for a wide range of active biomolecules within the body, including chemokines, growth factors, proinflammatory cytokines, angiogenesis factors, cell proliferation, and migration factors, wound healing mediators, apoptosis regulators, and other physiological and pathological processes [27, 28, 29]. Dysregulation of MMP biological functions has been linked to the progression and development of various diseases, which can be categorized into three groups: (i) tissue remodeling, (ii) fibrosis, and (iii) matrix degradation. Additionally, MMPs play a significant role in tumor metastasis and invasion [30]. They are often excessively expressed during tumor progression [31, 32].

Among MMPs, MMP-2 and MMP-9 are crucial in degrading extracellular matrices, thereby facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis [33]. They play a crucial role in the breakdown of ECM components within cerebral blood vessels and neurons [34]. In the central nervous system (CNS), MMPs, particularly MMP-9, are implicated in the pathogenesis of several CNS diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and multiple sclerosis as well as cancer, arterial, and pulmonary diseases [35, 36, 37]. Moreover, MMP-2 expression correlates with cancer patient characteristics, serving as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for various human diseases [38]. Their specific biological functions are mentioned in Table 1 (Ref. [34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]). MMP-2/9 can be activated through signaling pathways such as the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK), Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-

| MMPs classification | Name | Substrates | Biological effects | Related diseases | Refs. |

| Metalloproteinase-2 | Gelatinase A | - Collagen (type I, III, IV, V, VII, X) | - Cancer development | Cancer | [34, 38, 39, 40, 41] |

| (MMP-2) | - Gelatine | - Antiinflammatory | Cardiovascular diseases | ||

| - Laminin | - Degrade extracellular matrices | Inflammatory diseases | |||

| - Fibronectin | - Augmentation of Transforming Growth Factor- | Neurological disorders | |||

| - Aggrecan | - Influence the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK)/ Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) signaling pathway | Asthma | |||

| - Elastin | Fibrosis | ||||

| - Vitronectin | - Enhanced A | ||||

| - Myelin basic protein | |||||

| Metalloproteinase-9 | Gelatinase B | - Collagen (type IV, V, XI) | - Activation of TGF- | Cancer | [35, 36, 37, 42, 43, 44] |

| (MMP-9) | - Cytokines | - Influence the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway | Cardiovascular diseases | ||

| - Elastin | - Involvement in angiogenesis | Inflammatory diseases | |||

| - Decorin | - Facilitation of A | Diabetes | |||

| - Laminin | - Modulation of Interleukin-2 (IL-2) response | Wound healing disorders | |||

| - Chemokines | Ophthalmic diseases | ||||

| - Myelin basic protein | |||||

| - IL-8 and IL-1 |

MMP, Matrix metalloproteinase; MAPK, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; IL, interleukin.

Historically, it was believed that only one type of vitamin B has a critical role in maintaining growth and health as well as preventing characteristic skin lesions [48]. However, recent studies have uncovered that vitamin B is, in fact, a group of compounds collectively known as the ‘vitamin Bs’ [49]. The vitamin Bs, comprising a group of water-soluble vitamins as presented in Fig. 1. These vitamins are found abundantly in both animal and plant-based foods, offering a diverse array of sources for dietary intake [7]. Each type of vitamin Bs serves a unique function in metabolic processes within the human body, as mentioned in Table 2 (Ref. [50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81]) [49]. Collectively, all vitamin Bs help the body convert food (carbohydrates) into fuel (glucose) as a major energy source and use fats and protein for building tissues and cells [82]. They are also required for a healthy liver, skin, hair, and eyes, and for keeping the nervous system in good condition. Thus, they could be considered to play a vital role in maintaining overall health, homeostasis, and bodily functions [83]. In addition, the essentiality of vitamin Bs lies in their role as key intermediates in pathways that generate essential cofactors, including B1, thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP); B2, flavin mononucleotide/flavin adenine dinucleotide (FMN/FAD); B3, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD); B5, coenzyme A (CoA); B6, pyridoxal phosphate (PLP); B7, biotin-adenine monophosphate (biotin-AMP); B9, tetrahydrofolate (THF); and B12, methylcobalamin (Me-B12). These cofactors are required for hundreds of enzymes that carry out critical cellular functions [7].

| Vitamin Bs | Sources | Main functions | Refs. |

| Vitamin B1 | Nuts, dried beans, whole grain cereals, liver, eggs, and pork products | Effect diabetes | [50, 51, 52, 53, 54] |

| Keeping the nervous system, mental health, brain function, and cardiovascular systems healthy | |||

| Enhancing immune function | |||

| Vitamin B2 | Milk, eggs, lean meats, green leafy vegetables | Influencing cell proliferation | [55, 56, 57, 58] |

| Preventing anemia, cancer, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus | |||

| Vitamin B3 | Offal, meat, fish, wheat | Inflammatory functions | [59, 60, 61, 62] |

| Preventing atherosclerosis | |||

| Effect neurological disorders | |||

| Skin health | |||

| Vitamin B5 | Eggs, avocados, whole grains, meat, intestinal bacteria and royal jelly | Enhance wound-healing processes | [63, 64, 65, 66, 67] |

| Effect neurological disorders | |||

| Vitamin B6 | Fruits, poultry, fish, potatoes, chickpeas, whole grains, beef liver, and spinach | Antioxidant activity | [68, 69, 70] |

| Impact diabetes | |||

| Neurotransmitter synthesis | |||

| Supports immune function | |||

| Vitamin B7 | Leafy greens, eggs, beef liver, avocado, cheese, and cauliflower | Effect neurological disorders | [71, 72, 73, 74] |

| Skin and hair health | |||

| Inflammatory functions | |||

| Vitamin B9 | Leafy greens, citrus fruits, beans, fortified cereals | Cardiovascular diseases | [75, 76, 77] |

| Effect neurological disorders | |||

| Vitamin B12 | Meat, seafood, eggs, milk, and dairy products, cereals, and flour | Enhances brain health | [78, 79, 80, 81] |

| Impact heart health | |||

| Effect neurological disorders |

Typically, vitamin Bs are fundamental nutrients as they need to be obtained through diet and cannot be synthesized by the body [84]. Although they are grouped because they are commonly found in the same foods, they have distinct biochemical compositions [83]. Because they are water-soluble, daily intake is necessary as they are not stored in significant amounts in the body tissues, and any excess is typically excreted through the kidneys. In summary, vitamin Bs are essential for various metabolism in the human body by serving as coenzymes in various metabolic pathways [18, 85].

Vitamin B1, also known as thiamine, is the firstly identified among vitamin Bs and serves as a cofactor for numerous enzymes involved in energy metabolism [86]. Dietary sources of thiamine encompass nuts, dried beans, whole grain cereals, liver, eggs, and pork products. However, ingested thiamine is not the sole source within the human body, as intestinal bacteria also produce some thiamine [50]. Thiamine which is essential in all mammalian diets is synthesized by bacteria, fungi, and plants [87, 88]. It is comprised of a thiazole ring and a pyrimidine group, forming a sulfur-containing structure composed of two rings linked by a methylene group (Fig. 2; top left) [89].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Chemical structures of thiamine and its phosphorylated forms.

Thiamine is indispensable for cellular metabolism. Its biologically active form, thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), serves as an essential coenzyme in oxidative metabolism [90]. Moreover, thiamine could affect indirectly various metabolic steps of the electron transport chain, aiding in the extraction of energy from carbohydrate sources [91]. Acting as a prosthetic group or coenzyme, it facilitates the conversion of glucose to ATP and catalyzes the conversion of several carbon skeletons in the Krebs cycle [92]. Assisted by ATP, thiamine undergoes a process wherein a double phosphate is added to its structure, transforming it into its coenzyme forms: TPP, thiamine monophosphate (TMP), and thiamine triphosphate (TTP) as shown in Fig. 2 [89, 93]. Thiamine also keeps the nervous system, mental health, brain function, and cardiovascular systems healthy and enhances immune function [51, 52, 53].

Although thiamine is a water-soluble vitamin, it is stored in small amounts within the human body and distributed throughout various organs. In humans, free thiamine and TMP collectively account for 5–15% of total thiamine, while thiamine diphosphate (TDP) serves as the principal biologically active form, constituting 80–90% of total thiamine [94]. TDP is predominantly found in high concentrations in skeletal muscle, liver, heart, kidneys, and brain, where it plays essential roles in energy metabolism and cellular functions [95]. Furthermore, blood thiamine levels vary in populations. Approximately 75% is stored in erythrocytes for oxygen transport, emphasizing its role in red blood cell function. Another 15% is in leukocytes, suggesting a role in immune function, while 10% is in plasma, indicating systemic distribution [96]. Maintaining stable thiamine levels in the bloodstream has implications for overall health and physiological functions.

Tissue concentration of thiamine varies among different tissues in the body and it is regulated by various metabolic processes and transport mechanisms. Higher concentrations of thiamine are typically found in organs with higher metabolic activity, such as muscle, heart, liver, kidneys, and brain [97]. Unfortunately, thiamine has a relatively short half-life, typically ranging from 1 to 12 h. Thus, a consistent dietary intake is necessary to maintain adequate tissue thiamine levels [98, 99]. Once thiamine is deficient, multiple health problems, including neurological disorders, cardiovascular dysfunction, and metabolic abnormalities could be progressed [100]. Therefore, maintaining optimal tissue concentrations of thiamine is fundamental for overall health and well-being.

Thiamine is efficiently absorbed from dietary sources in the proximal small intestine, primarily in the upper jejunum. The absorption process is dose-dependent and occurs through two mechanisms: (i) carrier-mediated active transport, predominant when oral intake is less than 5 mg, and (ii) passive diffusion, more significant at higher doses [101]. Before absorption, dietary thiamine is typically present in phosphorylated forms such as TMP and TDP. Intestinal phosphatases facilitate the conversion of these forms into free thiamine, enabling absorption across the intestinal mucosa [102]. Upon ingestion, free thiamine is absorbed into enterocytes, specialized intestinal mucosal cells, through two saturable and high-affinity transporters: Thiamine transporter 1 THTR1 (encoded by the SLC19A2 gene) and Thiamine transporter 2 THTR2 (encoded by the SLC19A3 gene) [103]. THTR1 is located on both the apical brush-border membrane and the basolateral membrane of enterocytes, while THTR2 is exclusively found on the apical surface [93, 104]. Additionally, other transporters such as organic cation-transporters organic cation-transporter 1 (OCT1) and OCT3 also play a role in this process [94].

Following uptake from the intestinal tract, thiamine is primarily transported to the blood where it is mainly found in erythrocytes (75%) [105] and bound to erythrocytes. It is then delivered to cells with high metabolic demands in critical organs such as the brain, liver, pancreas, heart, and various muscle types for energy metabolism and cellular functions via transporter proteins [106]. Thiamine is rapidly excreted through the urinary system and is not known to accumulate in the body to significant levels. It is generally considered as non-toxic [107]. This transport mechanism ensures that thiamine is efficiently delivered to tissues where it is needed most for energy metabolism and cellular functions.

Thiamine undergoes rapid conversion to its active cofactor, TPP, catalyzed by thiamine pyrophosphokinase-1 (TPK-1) [108, 109] when thiamine is taken up by the cells (Fig. 3). TPP is the active form of thiamine and serves as a cofactor for multiple enzymes involved in energy metabolism, particularly in the decarboxylation of

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Cellular uptake and intracellular transformation of thiamine.

In cells, thiamine acts as a coenzyme for dehydrogenation in the glucose/amino acid metabolism pathway, playing an essential role in energy metabolism [86, 115]. It also supports the activity of four key enzymes in cellular metabolism: (i) pyruvate dehydrogenase, (ii)

Maintaining thiamine homeostasis is necessary to carry out essential functions including energy metabolism and supporting various biological processes. Table 2 presents detailed information, including the specific functions of thiamine, highlighting its importance in these areas. Interest in brain thiamine homeostasis is growing due to its relevance in neurodegenerative disorders. Thiamine deficiency could lead to a variety of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including memory disorders [117], cognitive impairment [118], and mood disorders such as depression [119]. Abnormalities in thiamine-dependent enzymes, oxidative stress, and altered metabolism are observed in various diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease, dry beriberi, neuropathy, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [120, 121, 122].

Besides, thiamine deficiency results in TPP deficiency, impairing the Krebs cycle, and leading to the accumulation of ketone bodies. This induces free radical production, inhibits

Vitamin B2, also referred as riboflavin, is a water-soluble compound with a yellow-orange color. Although riboflavin was first identified as a yellow fluorescent pigment in milk in 1872 [55], its properties as a vitamin were established only in the early 1930s [123]. Its molecular structure consists of a methylated isoalloxazine core and a ribityl side chain, which enhances its solubility and aids in the production of active cofactors [91]. Riboflavin is essential for the growth and reproduction of both humans and animals and is widely available in the food supply, being produced by all plants and most microorganisms [124]. Biologically, riboflavin functions as a precursor for the coenzymes, FAD and FMN, which play essential roles in redox reactions across all organisms along with the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, ketone bodies, and proteins, contributing significantly to the energy derivation process in living organisms [125].

While plants and certain microorganisms can synthesize riboflavin, it remains an essential nutrient for human health and must be obtained through the diet [123]. Detailed dietary sources of riboflavin are provided in Table 2. Its active forms, FMN and FAD, are shown in Fig. 4, which could facilitate enzymatic reactions crucial for overall health and well-being [126].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Chemical structure of riboflavin and its active forms.

Riboflavin is distributed widely throughout the body. It is found in various tissues and organs, including the liver, kidneys, heart, and brain [127]. Riboflavin is also existed in blood plasma and can cross cell membranes easily due to its small size and water solubility [128, 129]. The concentration of riboflavin varies in different tissues and organs. Liver and kidneys typically have higher concentrations of riboflavin compared to other organs [130, 131]. Additionally, riboflavin is presented in high concentrations in the brain and nervous tissue, indicating its importance in neurological functions [132].

Dietary riboflavin, when bound to proteins in food, is broken down into free riboflavin through hydrolysis. This free riboflavin is primarily absorbed in the proximal small intestine through a carrier-mediated, saturable transport process [133]. In various cells, riboflavin uptake occurs via specialized carrier-mediated processes supported by three specific members of the solute carrier family 52 (SLC52A), known as riboflavin transporter 1 (RFVT1; SLC52A1), RFVT2 (SLC52A2), and RFVT3 (SLC52A3), respectively [134, 135] (Fig. 5). While most absorption occurs in the small intestine, riboflavin is also absorbed in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach, duodenum, colon, and rectum, mediated by RFVT3, ensuring its distribution throughout the body [98]. At the apical membrane of enterocytes, riboflavin is absorbed primarily through the action of RFVT3, which is expressed at a higher level compared to other riboflavin transporters. The vitamin is subsequently released into the bloodstream by RFVT2 and RFVT1, which are mainly localized at the basolateral membrane domain [136, 137]. After intestinal absorption, which primarily occurs in the small intestine, riboflavin is distributed from the blood to various tissues, mostly in its free form or bound to albumin and globulins [135, 137, 138].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Absorption, transportation, and metabolism of riboflavin.

In addition to that, dietary sources contain not only free riboflavin but also flavoproteins with bound flavin mononucleotide(FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), which require hydrolysis to release riboflavin [139]. FMN and FAD act as proton carriers in redox reactions essential for energy metabolism, metabolic pathways, and the synthesis of certain vitamins and coenzymes [140]. Moreover, these coenzymes participate in various metabolic pathways, including energy production through the electron transport chain and the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins [141, 142]. The primary function of RFVT3 is to absorb riboflavin from the diet [143]. Inside the gastrointestinal cells, riboflavin is phosphorylated to form FMN by riboflavin kinase (RFK), and subsequently, FMN is further metabolized to FAD by FAD synthase (FADS), playing a key role in various enzymatic reactions in energy and metabolic pathways [144]. Excess riboflavin is excreted in the urine as riboflavin itself, along with its metabolites, including 7-hydroxymethyl riboflavin and lumiflavin [143].

The body tightly regulates the homeostasis of riboflavin to ensure optimal levels for cellular functions. Riboflavin deficiency can lead to various health problems. Conversely, excessive intake of riboflavin is usually excreted in urine, and toxicity is rare [145]. The majority of riboflavin in tissues is bound to enzymes [146]. Unbound flavins are relatively unstable and undergo rapid hydrolysis to free riboflavin, which then diffuses from cells and is excreted. Therefore, the intracellular phosphorylation of riboflavin represents a form of metabolic trapping crucial for maintaining riboflavin homeostasis [147].

Given its critical role in various metabolic pathways and cellular processes, riboflavin has been confirmed to serve as a cofactor in metabolism of fat, amino acids, carbohydrates, and vitamins. Additionally, it plays a role in reducing oxidative stress and influencing cell proliferation and angiogenesis [56, 148]. Previous studies have shown that a low intake of dietary riboflavin can lead to negative health consequences, including an increased risk of developing several cancers (e.g., colorectal cancer) [57, 149]. Moreover, riboflavin-dependent enzymes are essential for activating pyridoxine (vitamin B6), the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway, and homocysteine metabolism, with pyridoxal phosphate demonstrating neuroprotective potential [126]. Also, riboflavin helps alleviate oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and glutamate excitotoxicity, all of which contribute to the pathogenesis of PD, migraine headaches, and other neurological disorders [126]. Furthermore, the role of riboflavin extends to the prevention of various health conditions, including migraine, anemia, cancer, hyperglycemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and oxidative stress, either directly or indirectly [58].

Vitamin B3, alternatively known as niacin or nicotinic acid, was identified as the precursor in the synthesis of NAD+ and its analog nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+) [150]. These coenzymes participate in numerous physiological processes, including energy metabolism, DNA repair, and cell signaling [151, 152]. Humans obtain niacin from two sources: (i) an exogenous source, where the vitamin is obtained from the diet via intestinal absorption, and (ii) an endogenous source, where the vitamin is produced through the metabolic conversion of tryptophan when the exogenous supply of the vitamin is insufficient [153, 154]. Niacin is naturally present in various foods: offal, meat, and fish are particularly rich sources of nicotinamide, although smaller amounts are found in vegetables [59]. Among cereal crops, wheat has the highest nicotinamide content, whereas corn contains very low levels [60]. Besides, the aforementioned food sources are also rich in tryptophan, an amino acid that can be converted into niacin in the liver [155]. Vitamin B3, in general, includes several forms such as niacin (pyridine-3-carboxylic acid), nicotinamide (niacinamide or pyridine-3-carboxamide), and related derivatives like nicotinamide riboside, as shown in Fig. 6 [156, 157].

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Precursors of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) in the diet.

After ingestion, niacin is absorbed in the small intestine through both passive diffusion and active transport mechanisms. It is then distributed throughout the body via the bloodstream, where it reaches various tissues and organs [158]. The liver plays an essential role in the metabolism of exogenous niacin and stores niacin for future use. This role has been demonstrated by both in vivo and in vitro studies, which show that niacin is taken up in a saturable manner by human hepatocytes [159, 160]. Niacin can also be accumulated in adipose tissue, where it may be stored for later release and utilization [161]. Tissue concentrations of niacin vary, with higher levels found in tissues with high metabolic activity, such as the liver, kidney, and heart [162, 163, 164]. Although the concentrations could be dependent on dietary intake, metabolic activity, and individual physiological conditions, niacin exists in plasma at levels typically ranging from 0.1 to 1 µM [159].

Nicotinamide riboside, another form of niacin, can be found in some foods and is then converted into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), an essential intermediate step in the synthesis of NAD+. Also, tryptophan can be metabolized into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) through a series of biochemical reactions [165]. Nicotinamide is rapidly absorbed, primarily through Na+-dependent diffusion at low concentrations. Even at extremely high dosages of 3–5 g, niacin is predominantly absorbed through passive diffusion [154]. Through the bloodstream, it distributes to all parts of the body. Nicotinamide can then be converted into niacin through hydrolytic reactions. All these forms of vitamin B3 can be converted into active forms of NAD+ and NADP+, two essential compounds in energy transmission and oxidation processes within cells [166].

In terms of clearance, at low doses, a significant portion of niacin is metabolized through nicotinamide to N-methyl-nicotinamide, which further breaks down into N-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide and N-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide, eventually being excreted via the kidneys [167]. At intermediate and high pharmacological doses (1–3 g), an increasing fraction of niacin is conjugated with glycine to form nicotinuric acid and excreted by the kidneys as nicotinuric acid [168]. Renal excretion plays a significant role in the clearance of excess niacin from the body, particularly at higher doses used for therapeutic purposes.

In cells, nicotinamide is converted into NAD+ through a series of enzymatic reactions. These reactions occur in various cellular compartments, including the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and nucleus. NAD+ serves as a coenzyme in redox reactions, energy metabolism, and cellular signaling processes [169]. It participates in key metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle), and oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, facilitating ATP production, and energy metabolism [165]. The process of niacin metabolism within cells is similar both in the liver and in other cells throughout the body. Niacin and nicotinamide undergo metabolic transformations crucial for their biological functions. One of their primary roles is their involvement in the synthesis of NAD+ and NADP+ [170]. More specifically, niacin undergoes conversion to niacin mononucleotide, subsequently progressing to niacin dinucleotide, before finally transforming into NAD+ [171] (Fig. 7). On the other hand, nicotinamide (NAM) can be transformed into NMN, which is further converted into NAD+. Similarly, NAD+ can also convert into NADP+ by adding a phosphate group, a process catalyzed by NAD+ kinase [172]. This enzyme transfers a phosphate group from ATP to NAD+, forming NADP+.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Cellular uptake and intracellular activities of niacin.

Moreover, NAD+ plays critical roles in DNA repair, gene expression regulation, and cell survival [173, 174]. It acts as a substrate for enzymes like poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerases (PARPs) and sirtuins, which are involved in DNA repair and epigenetic modifications, respectively [175]. These activities are critical for maintaining genomic stability, cellular homeostasis, and response to stressors. Additionally, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced (NADH) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced (NADPH) also hold significant functions in cellular metabolism and homeostasis [176].

Niacin plays a pivotal role in numerous biological processes including energy metabolism, DNA repair, and cell signaling within the body as mentioned in Table 2. Additionally, its involvement in these processes is closely linked to the development and progression of various diseases [156]. The symptoms of niacin/nicotinamide deficiency are notably evident in the gastrointestinal tract, nervous system, and particularly in the skin [60]. Niacin has been also observed to play a role in reducing inflammation. This mechanism involves the stimulation of the PGD2/DP1 signal in endothelial cells, which inhibits vascular permeability in intestinal tissues, thereby mitigating inflammation [177]. Niacin has been shown to inhibit the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory mediators induced by various stimuli in cultured human endothelial cells [61, 178].

In addition, niacin is integral for preventing neuronal death [62]. In particular, nicotinamide is emerging as a key player in protecting neurons against various forms of damage, including traumatic injury, ischemia, and stroke which have the potential to cure three prominent neurodegenerative disorders: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD) [62]. Previously, it has been reported that nicotinamide could stabilize the epidermal barrier, enhances moisture in the horny layer, smoothens wrinkles on aging skin, and inhibits photocarcinogenesis. These effects are achieved by enhancing protein and keratin synthesis, stimulating ceramide production, and accelerating keratinocyte differentiation [60]. Niacin also has been widely utilized for the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis by improving lipid profiles, which are key factors in cardiovascular health [179]. Furthermore, niacin could inhibit the production of atherogenic chemokines and upregulate the atheroprotective adiponectin in adipocytes [180].

Vitamin B5, also known as pantothenic acid, is essential for various bodily processes and indispensable for the normal function of cells [181]. The name “pantothenic” is derived from the Greek word “pantothen”, meaning “from everywhere”, reflecting its ubiquitous presence in a wide variety of foods [182].

Due to its widespread presence, pantothenic acid is sourced from two main origins: dietary intake and bacterial synthesis [183]. Pantothenic acid is not synthesized by animal tissues but is instead produced by intestinal bacteria as well as many other bacteria, fungi, and plants. It is also found widely in various foods [184]. A wide variety of plant and animal foods contain pantothenic acid, ensuring its availability in the diet. Major dietary sources of pantothenic acid include meat, offal (such as liver and kidney), eggs, dairy products (milk, cheese), nuts, mushrooms, yeast, whole grain cereals, legumes, cruciferous vegetables (such as broccoli or cauliflower), avocado, potatoes, and tomatoes (Table 2) [63, 124, 185]. Royal jelly is indeed considered one of the richest natural sources of pantothenic acid [64, 186].

Approximately 85% of dietary pantothenic acid is present in the form of CoA (Fig. 8) or its precursor, phosphopantetheine, which are essential coenzymes involved in various metabolic processes within the body [187]. However, smaller amounts exist as free pantothenic acid or as a component within the acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) [188]. Our bodies utilize pantothenic acid to convert nutrients into energy through its role in the synthesis of CoA [189]. Additionally, it is involved in the synthesis and breakdown of fats, playing a vital role in lipid metabolism [190]. This essential nutrient is involved in numerous metabolic pathways, making it indispensable for maintaining overall cellular health and metabolic functions.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Structure of pantothenic acid active form (CoA).

Pantothenic acid is distributed widely throughout the tissues for numerous physiological functions. Certain organs contain higher concentrations due to their metabolic activity and demand for CoA. The liver is one of the organs with the highest concentrations of pantothenic acid for the synthesis and breakdown of fats and cholesterol [191]. Adrenal glands also have significantly high concentrations of pantothenic acid, as it is necessary for the synthesis of adrenal hormones, such as cortisol and aldosterone [192]. Other tissues with notable concentrations of pantothenic acid include the kidneys, heart, brain, and skeletal muscles [91]. Intracellularly, with the highest concentration of pantothenic acid found in mitochondria as 2.2 mM, serving as a precursor for CoA [193]. Additionally, pantothenic acid is present in peroxisomes (20–140 µM) and the cytoplasm (less than 15 µM), where it continues to play essential roles in metabolic reactions [193].

After entering the body, pantothenic acid is absorbed primarily in the small intestine with the duodenum and jejunum as the main sites of absorption [194, 195]. The absorption process involves passive diffusion and active transport mechanisms. The sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter (SMVT, SLC5A6) is responsible for actively transporting free pantothenic acid across cell membranes, particularly at low luminal concentrations [196]. Pancreatic enzymes help release pantothenic acid from food sources, making it available for absorption [91]. This mechanism ensures the absorption of pantothenic acid in the intestine or other relevant tissues. Once absorbed, pantothenic acid is transported across the intestinal epithelium into the bloodstream. Then, it binds mainly to plasma proteins, notably albumin, acting as a carrier protein to transport pantothenic acid to various tissues and organs throughout the body [197]. Additionally, pantothenic acid can enter cells through both free diffusion across cell membranes and specific transport proteins [198].

Unlike other vitamins, pantothenic acid is absorbed directly into the bloodstream from the intestines. It is then transported to various tissues and organs [199]. In addition to intestinal absorption, pantothenic acid can also be absorbed in the colon and promptly enter the bloodstream, particularly at higher dosages [200, 201, 202]. Red blood cells play a role in distributing pantothenic acid throughout the body. They serve as carriers, transporting pantothenic acid to various tissues and organs where it is needed for various metabolic processes [203, 204]. Intestinal cells absorb panthetheine, which is the dephosphorylated form of phosphopantetheine, and subsequently convert it into pantothenic acid before releasing it into circulation [205]. Ultimately, pantothenic acid and its metabolites are excreted primarily through urine, with excess amounts being eliminated via the kidneys [197, 206]. The turnover of CoA and ACP can result in the recycling of pantothenic acid for further use or its excretion unchanged in the urine, helping to maintain optimal levels of this essential nutrient within the body [207].

Pantothenic acid is a key component of CoA and ACP both playing critical roles in cellular metabolism [208]. Five enzymatic steps are required for pantothenic acid to convert into CoA as shown in Fig. 9. Phosphorylation by pantothenate kinase, marking the first step in CoA synthesis. This phosphorylation yields phosphopantothenate [209]. Subsequently, phosphopantothenate undergoes condensation with cysteine, catalyzed by 4′-phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthase (PPCS), followed by decarboxylation to form 4′-phosphopantetheine, mediated by 4′-phosphopanthenoylcysteine decarboxylase (PPCDC). Next, 4′-phosphopantetheine is adenylylated to dephospho-CoA by phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT) [210, 211]. Last, dephospho-CoA is phosphorylated by dephospho-CoA kinase (DPCK) at the 3′-OH of the ribose, leading to the production of CoA [210, 211]. Serving as a carrier of carboxylic acid substrates, CoA facilitates essential biochemical processes like the citric acid cycle, sterol biosynthesis, amino acid metabolism, and the synthesis and breakdown of fatty acids and lipids [212]. Besides, pantothenic acid also participates in the synthesis of ACP, which is essential for fatty acid synthesis and supports the ATP synthesis process [213].

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. Cellular uptake and intracellular activities of pantothenic acid.

Pantothenic acid is essential for both metabolic processes and immune function in the body. It triggers immune cells to produce cytokines, key proteins regulating immune responses to various pathogens [188]. Besides, pantothenic acid is suggested to act as a profibrotic agent, potentially enhancing and expediting wound-healing processes. It achieves this by attracting migrating fibroblasts to the affected areas, promoting the proliferation and activation of fibroblasts, and stimulating collagen synthesis [65, 214].

Furthermore, pantothenic acid is involved in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in brain tissue, underscoring its pivotal role in neuronal function and neurotransmission [66]. Recent studies have revealed that pantothenate, a salt form of pantothenic acid, deficiency may have a significant impact on myelin loss, acetylcholine deficiency, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairment observed in age-related dementias such as AD and HD [67, 215].

Emerging research also highlights the impact of pantothenic acid on chronic conditions like diabetic kidney disease (DKD). In a study, researchers found that people with DKD had abnormalities in pantothenic acid levels and metabolism [216]. This was accompanied by various mechanisms including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, increased serum C-reactive protein (CRP), metabolic pseudo-hypoxia, and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [216]. As a result of the proliferation and migration of dermal fibroblasts, pantothenic acid promotes skin regeneration and facilitates the successful healing of burn and surgical wounds [214]. Therefore, the pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis pathway plays a significant role in various cellular physiological and pathological processes [217].

Vitamin B6, commonly referred to as pyridoxine (PN), is vital for general cellular metabolism [218]. Since its discovery in 1935 by György and colleagues [48], it has been recognized as a cofactor in more than 140 biochemical reactions within the cell [219]. Vitamin B6 comprises a group of six related substances: pyridoxine (PN), pyridoxal (PL), pyridoxamine (PM), and their respective 5′-phosphates (pyridoxine 5′-phosphate (PNP), pyridoxal 5′-phosphate PLP, and pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate (PMP)) as shown in Fig. 10 [220]. PMP has been identified as a cofactor for certain enzymatic reactions, and PLP has been reported as the biologically most active form [221, 222].

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Metabolism of vitamin B6.

Dietary sources of vitamin B6 are notably diverse. It is abundant in various foods such as fruits, starchy vegetables, poultry, fish, organ meats, fortified cereals, lentils, sunflower seeds, cheese, brown rice, carrots, chickpeas, whole grains, beef liver, ground beef, chicken breast, watermelon, and spinach as shown in Table 2 in detail [68]. In human body, vitamin B6 participates in various metabolic processes, including the transformation of carbohydrates, lipids, amino acids, and nucleic acids. It serves as a coenzyme in key reactions such as glycogen breakdown, amino acid transformations (transamination and decarboxylation), and reactions catalyzed by amino acid synthases or racemases [223]. Additionally, vitamin B6 plays a role in neuronal signaling by facilitating the synthesis of neurotransmitters [224]. The extensive roles of vitamin B6 across various reactions underscores the profound clinical consequences of its deficiency [223].

Regarding its distribution, vitamin B6 is distributed widely throughout the body, with significant amounts found in the liver, muscles, and brain [225, 226, 227]. It is also existed as smaller amounts in other tissues and organs, including the kidneys, heart, and red blood cells [228]. Tissue concentrations of vitamin B6 vary depending on the metabolic demands. The highest concentrations of vitamin B6 are typically found in the liver, where it is involved in numerous metabolic processes [229]. Vitamin B6 is in the brain for neurotransmitter synthesis and in muscles for protein metabolism [83, 230]. Although the concentration of vitamin B6 in other tissues is lower, it is still significant for maintaining cellular functions and metabolism [231].

The absorption of vitamin B6 in the intestines occurs through two sources: (i) dietary intake in the small intestine and (ii) the absorption of vitamin B6-producing bacteria in the large intestine [232]. Upon passive absorption in the intestine, the majority of pyridoxine is converted in the liver to PLP [233, 234] as illustrated in Fig. 10. Two enzymes mediate this pathway: PL kinase and PNP oxidase [235]. The first enzyme catalyzes the phosphorylation of the 5′-alcohol group of PN, PL, and PM to produce PNP, PLP, and PMP, respectively. Subsequently, both PNP and PMP are converted to PLP in an FMN-dependent oxidative process catalyzed by PNP oxidase [235]. Then, following the hydrolysis of PL by alkaline phosphatases, PLP is transported to various tissues through the bloodstream. Most of the excess PL beyond tissue requirements is oxidized by the liver to 4-pyridoxic acid, which is the major degradation product of pyridoxine excreted in urine [236]. 4-Pyridoxic acid is the primary excretory product.

Cells take up various forms of Vitamin B6, including PN, PL, and PM through specific transporters located in the cell membrane. Once inside cells, vitamin B6 undergoes phosphorylation to generate its active form, PLP, by the enzyme pyridoxal kinase, as observed in the liver [237]. Within cells, PLP participates in numerous biochemical reactions, including the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA [238, 239]. PLP is also involved in the metabolism of amino acids, such as the conversion of tryptophan to niacin and the synthesis of heme and nucleic acids [240].

Vitamin B6 homeostasis is tightly regulated to maintain optimal cellular function to prevent deficiency or toxicity [231]. Vitamin B6-dependent enzymes are needed for the biosynthesis of at least three important neurotransmitters; epinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin [241]. As vitamin B6 is essential for neurotransmitter synthesis, it is reasonable to anticipate that the availability of its active form, PLP, may influence various neurological disorders such as AD, PD, epilepsy, autism, and schizophrenia [69].

PLP deficiency may impact diabetes by affecting the conversion of tryptophan to niacin, as PLP is a cofactor for enzymes in this pathway [242, 243]. Moreover, PLP deficiency may impact insulin resistance by regulating genes involved in adipogenesis [244]. In the immune system, vitamin B6 is pivotal for the generation of T lymphocytes and interleukins. A deficiency in vitamin B6 results in compromised immunity, characterized by reduced serum antibody formation, diminished interleukin (IL)-2 production, and elevated IL-4 levels. Consequently, the body becomes more susceptible to infections and struggles to combat diseases effectively [245]. In addition, PLP has been suggested to influence carcinogenesis through various pathways, including those related to DNA metabolism. This suggests that the antitumor properties of vitamin B6 may be attributed to its protective role against DNA damage [246]. Especially, PLP is also involved in reactions related to antioxidant activity, the inflammatory process, homocysteine catabolism, and phosphorylation, all of which are metabolic processes associated with the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [70].

Vitamin B7, also known as biotin, is important for the metabolic processes of all known organisms and serves as a cofactor for five carboxylases: propionyl-CoA carboxylase, pyruvate carboxylase, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2. These enzymes catalyze essential steps in the metabolism of fatty acids, glucose, and amino acids [247, 248]. However, unlike plants and microorganisms, animals do not possess the enzymatic machinery necessary for synthesizing biotin internally. Therefore, animals rely on dietary intake to meet their biotin requirements [248]. Although biotin is existed in various foods (i.e., yeast, whole-wheat bread, green leafy vegetables, eggs, beef liver, avocado, cheese, and cauliflower), it is typically found in relatively low concentrations compared to other water-soluble vitamins [71]. While biotin is widely distributed in nature, it is presented in a protein-bound form in most foods, which is not easily accessible for cellular metabolism [248, 249]. Biotin serves as an essential cofactor for biotin-dependent enzymes across organisms from all three domains of life including those in bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. These enzymes play pivotal roles in various metabolic pathways, including gluconeogenesis, amino acid metabolism, and fatty acid synthesis [250, 251, 252]. Dietary sources and its roles are also presented in Table 2.

Biotin is widely distributed throughout different tissues and organs, with varying concentrations depending on their metabolic demands and roles [253]. It is present in relatively low concentrations compared to other water-soluble vitamins but is essential for various metabolic processes. Tissue concentrations of biotin vary, with higher levels typically observed in organs with high rates of metabolism, such as the liver, kidneys, and brain [254]. These organs require biotin for key metabolic processes, including gluconeogenesis, fatty acid synthesis, and amino acid metabolism [255, 256]. Additionally, biotin is fundamental for maintaining the health of the skin, hair, and nails, which also contribute to its distribution throughout the body [257, 258].

Upon ingestion, gastrointestinal proteases and peptidases degrade the protein-bound biotin into biocytin and biotin-oligopeptides. These compounds are subsequently processed by biotinidase, an enzyme present in the intestinal lumen, to release free biotin [249]. This free biotin is then absorbed in the small intestine, with the liver serving as the primary storage site for most biotin [249]. The sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter (SMVT) is known to transport biotin and pantothenic acid across biological membranes [259]. Specifically, SMVT facilitates the uptake of biotin into cells, aiding in the distribution of this essential vitamin throughout the body.

In the intestine, biotin is absorbed primarily through a sodium-dependent transporter at normal concentrations [260, 261]. This mechanism of absorption was demonstrated in studies using the human intestinal cell line Caco-2, which serves as a useful model for studying cellular and molecular regulation of biotin uptake. Free biotin is transported across the cell membrane by various sodium-dependent transporters with distinct kinetic properties and tissue localization [196, 262, 263]. However, at higher biotin concentrations, passive diffusion becomes the predominant mechanism of absorption [264, 265]. Once inside the cell, biotin participates in numerous essential biological processes. Biotin clearance primarily occurs through renal excretion, where the kidneys filter biotin from the blood and excrete it into the urine [266].

Within the cell, biotin is converted to biotin-AMP (B-AMP) through the action of holocarboxylase synthetase (HCS) [254, 267] (Fig. 11). B-AMP is then attached to apocarboxylases, converting them into active holocarboxylases including carboxylase pyruvate, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, propionyl-CoA carboxylase, and ethylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase [268]. Holocarboxylases participate in vital carboxylation processes within the cell, essential for fatty acid synthesis and gluconeogenesis. Biotin-dependent carboxylases play critical roles in energy metabolism, macronutrient metabolism, and the synthesis of key cellular building blocks [269]. However, after a period of activity, they are degraded through proteolysis to biocytin. To recycle biocytin and regenerate biotin, the biotinidase enzyme cleaves the peptide bond between biotin and lysine [270]. This process releases biotin and lysine separately. Biotin can then be reused in various metabolic processes, while lysine can be utilized for protein synthesis or other cellular functions [271]. This procedure is shown in Fig. 11. Biotin is involved in the regulation of gene expression, cell signaling, and maintenance of chromatin structure. Biotinylated histones have been identified in chromatin, suggesting a potential role in epigenetic regulation [272, 273].

Fig. 11.

Fig. 11. Cellular uptake and intracellular activities of biotin.

Maintaining normal body functions in the heart muscle and brain relies on essential biotin homeostasis [274]. This balance is maintained through (i) efficient transporter-mediated absorption in the intestines, (ii) cellular transport facilitated by enzyme-mediated conjugation of biotin to carboxylases, and (iii) an effective recycling mechanism that minimizes urinary excretion of biotin [267]. Imbalances in biotin levels can lead to various disorders, including biotin deficiency or excess. A severe deficiency of biotin can result in a range of clinical abnormalities observed in human patients, including growth retardation, neurological disorders, and skin problems [72, 73, 251].

Additionally, recent study indicate that biotin could regulate gene expression, suggesting its potential role in metabolic and neurological disorders as well [254]. Transcription factors such as NF-

Vitamin B9 is a collective term referring to a group of chemically similar forms of the water-soluble vitamin known as folate. It was identified in the 1930s, where it was described as a new hematopoietic factor found in yeast and the liver [275, 276]. In food, folate is commonly found in the form of pteroylpolyglutamate. Rich sources of folate include green leafy vegetables, sprouts, fruits, brewer’s yeast, liver, and kidney [75]. On the other hand, folic acid is a synthetic form of folate commonly added to fortified foods and vitamin supplements [277].

Folate plays a pivotal role as a methyl donor in various biochemical reactions, contributing to neurotransmitter synthesis, DNA biosynthesis, regulation of gene expression, and amino acid synthesis and metabolism [278]. Its involvement in methylation reactions is particularly important for processes such as DNA methylation, which plays a critical role in regulating gene expression and maintaining genomic stability [279, 280]. Folic acid, being a synthetic form of folate, plays a vital role in cell division, as well as in the synthesis of amino acids and nucleic acids. Consequently, it is indispensable for supporting growth processes within the body [281]. In addition, folic acid and its metabolites play a crucial role in the synthesis of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides [282].

Folate is distributed throughout the body via the bloodstream [283]. After absorption in the small intestine, it enters the bloodstream and is transported to various tissues and organs where it is needed. Folate is distributed to tissues, primarily distributed in the liver and bone marrow [284, 285], that require it for cellular processes such as DNA synthesis and repair [286]. The liver contains a significant amount of folate and plays a vital role in its synthesis and storage. While folate also exists in other organs such as connective tissue and the nervous system [287].

Folate absorption primarily takes place in the proximal part of the small intestine, particularly in the duodenum and jejunum [288]. Folate in dietary sources primarily exists in the polyglutamate form, which must undergo hydrolysis to the monoglutamate form before absorption. This hydrolysis process is facilitated by glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII), predominantly found in the brush border of the proximal part of the jejunum (Fig. 12) [289]. Once converted to monoglutamate folate, it is transported across the apical membrane of enterocytes primarily by the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) [288, 290]. Within enterocytes, folate undergoes metabolism to THF by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). After combining with THF in the liver, it undergoes conversion into the active form, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) [291]. The transmembrane transport of folate is mechanistically facilitated by a combination of receptors and specific carriers that are active across cell membranes [292].

Fig. 12.

Fig. 12. Transportation, metabolism, and biological functions of folate.

Folinic acid serves as a highly metabolically active form of folate, acting as an immediate precursor to 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-MTHF) (Fig. 12). This compound is swiftly metabolized to generate active folate (5-MTHF), which plays essential roles in various cellular metabolic processes [75]. Within the liver, similar to the intestines, THF is converted into 5,10-MTHF by the enzyme Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1). Then from 5,10-MTHF to the final active form of 5-MTHF by Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), which is distributed throughout the tissues and organs [293]. Unused or excess folate, along with its metabolites, is excreted primarily in the urine [294]. The liver and kidneys play essential roles in folate metabolism and excretion. This intricate process ensures efficient folate absorption and utilization throughout the body, supporting various cellular functions essential for overall health [295].

Once inside cells, folate undergoes a series of enzymatic reactions to be converted into 5-MTHF which serves as the active form of folate and is the primary circulating form of folate in the body [296]. Additionally, 5-MTHF is the predominant type of folate found in food sources. Folate, specifically 5-MTHF, is pivotal in folate-dependent one-carbon metabolism, essential for amino acid metabolism and the biosynthesis of purine and pyrimidine, which are key for DNA and RNA synthesis [297]. Additionally, folate contributes to the formation of the primary methylating agent S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM), which serves as the universal methyl donor for DNA, histones, proteins, and lipids [298]. Moreover, 5-MTHF participates in the production of neurotransmitters, vital chemical compounds facilitating signal transmission between nerve cells [278]. Another active form, THF, also plays a significant role through a series of enzymatic reactions. THF serves as a cofactor in one-carbon transfer reactions, essential for nucleotide synthesis (the building blocks of DNA and RNA) and amino acid metabolism [299, 300]. It is particularly essential during periods of rapid cell division and growth, such as fetal development, and in tissues with high turnover rates, like bone marrow [301].

The body tightly regulates folate homeostasis through various mechanisms to maintain optimal levels of this essential vitamin. The liver plays a significant role in folate homeostasis by storing and releasing folate as needed [302]. A poor folate status may lead to chronic diseases stemming from abnormalities in protein synthesis, DNA replication, and gene expression [303, 304]. Low levels of folate are linked to reduced synthesis of methionine and elevated plasma homocysteine levels [305]. This increase in homocysteine is a recognized risk factor for several conditions including atherosclerosis, recurrent thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, dementia, and mortality from cardiovascular disease [76, 306].

A recent study demonstrated a significant association between AD and low serum folate levels which might contribute to an elevated risk of AD [77]. Folate deficiency has been shown to induce oxidative stress and trigger the production of ROS, contributing to neuronal deterioration and cellular death in brain regions implicated in AD [307].

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a nutrient-containing cobalt in its structure and represents one of the most intricately structured small molecules created by nature [308]. It plays an essential role in various physiological functions throughout life. Since cobalamin is synthesized by certain microorganisms (archaea and bacteria), humans acquire it exclusively from their diet, particularly from animal-derived foods such as meat, seafood, eggs, milk, and dairy products as shown in Table 2 [78, 309]. Specifically, the meat and milk derived from herbivorous ruminant animals serve as valuable sources of cobalamin for human consumption [78]. Plant-based foods typically do not contain cobalamin, except cereals, milk substitutes, and flour [310].

Cobalamin is of paramount importance for various physiological functions, particularly in collaboration with vitamin B6 and folate. It serves a critical role in red blood cell formation and nucleic acid synthesis, especially within neurons. Cobalamin deficiency can have severe consequences, including megaloblastic anemia and neurological symptoms like peripheral neuropathy, which is characterized by numbness in the hands and feet [311].

Cobalamin is distributed and stored in various tissues throughout the body. After absorption in the small intestine, cobalamin is transported through the bloodstream bound to transport proteins such as transcobalamin II (TCII) or haptocorrin which help distribute cobalamin to different tissues and organs throughout the body, including the liver, bone marrow, muscles, brain, and nervous system [312]. Different tissues and organs utilize cobalamin for various biochemical reactions. It is particularly concentrated in tissues with high metabolic activity and rapid cell turnover [313]. The liver serves as the primary storage site for cobalamin ensuring a steady supply for metabolic needs [314]. The liver stores a significant reserve of cobalamin approximately 50–90% of total amounts in the entire body (1 to 1.5 mg) [315].

Cobalamin absorption primarily occurs in the small intestine, specifically ileum [199, 316]. In the stomach, cobalamin is released from dietary proteins, including protein from meat, fish, eggs, and dairy products by the action of gastric acid and pepsin. Cobalamin binds to a protein called intrinsic factor, which is secreted by parietal cells in the stomach [317]. The complex of cobalamin and intrinsic factors travels through the digestive tract to the ileum, where it binds to receptors on the mucosal surface. Only approximately 1% of free cobalamin is recognized to be passively absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract [318]. The dietary uptake of cobalamin involves a sequential process where it first binds to haptocorrin and intrinsic factors [319]. Following its release by gastric acid, Cobalamin Interacting Factor (Cbl–IF) travels to the terminal ileum, where it is absorbed with intrinsic factor, an enzyme secreted by the parietal cells of the stomach [320].

After being absorbed by the ileal mucosa, cobalamin bound to TCII enters the portal circulation. TCII is a physiological transport protein synthesized by hepatocytes, endothelial cells, and enterocytes. It is responsible for transporting cobalamin in the bloodstream. Cobalamin is released into the bloodstream, forming a complex with TCII (in 1:1 ratio) then transported to various tissues [315]. The Cobalamin–Transcobalamin II (Cbl–TCII) complex can also be transported from the liver to tissues and some are stored in the liver for later use [321]. Although cobalamin belongs to the group of water-soluble vitamins, it is excreted in both urine (ca. 1%) and feces (together with bile) [322, 323].

Within cells, cobalamin is transported to various organelles (i.e., mitochondria) where it participates in metabolic pathways involved in energy production and lipid metabolism [324]. Cobalamin is initially bound to TCII in the bloodstream [325, 326]. Cells expressing receptors for TCII, such as cubilin and megalin, facilitate the uptake of the Cbl–TCII complex through receptor-mediated endocytosis. This process primarily occurs in tissues with high metabolic demands, such as the liver, kidney, and bone marrow [327].

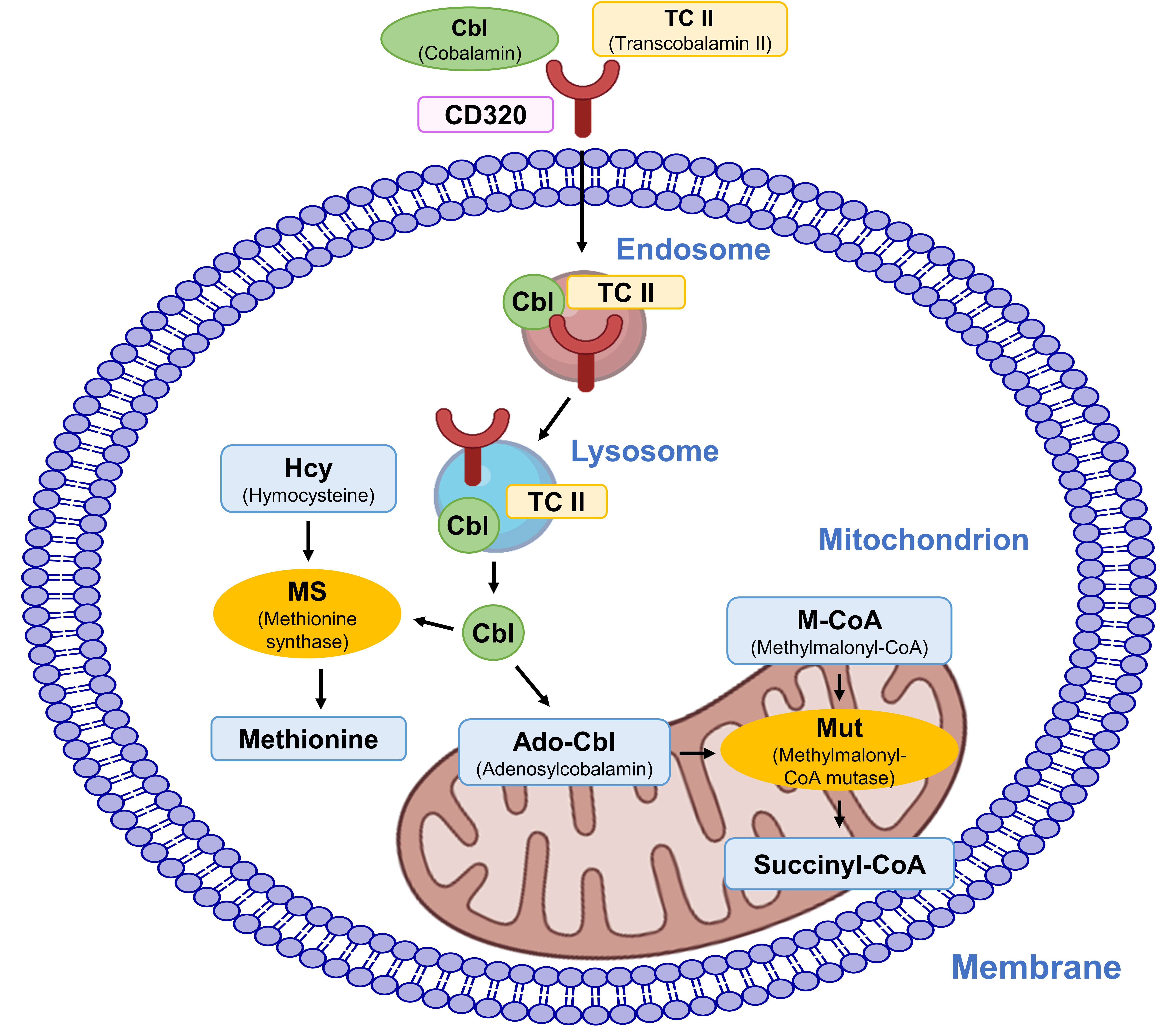

Once internalized the Cbl–TCII complex associates with the CD320 cluster, which is a protein on the cell surface, facilitating its internalization into the endosome [328]. Then, this complex is trafficked to lysosomes within the cell. In the acidic environment of the lysosome, TCII dissociates from cobalamin (Fig. 13). This process allows for the release of cobalamin from lysosomes into the cytoplasm [329]. In the cytoplasm, cobalamin serves as a cofactor for two key enzymes: methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and methionine synthase [330, 331]. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase converts methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, which is critical for fatty acid metabolism. Methionine synthase facilitates the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, a process essential for the synthesis of nucleic acids and proteins and for maintaining normal neurological function [332].

Fig. 13.

Fig. 13. Cellular uptake and intracellular activities of cobalamin.

Cobalamin is necessary for maintaining DNA stability. It acts as a cofactor for enzymes like methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which are essential for DNA methylation and nucleotide synthesis [333]. Additionally, cobalamin possesses antioxidant properties that aid in shielding DNA from damage inflicted by ROS [334, 335]. It has also been demonstrated that cobalamin, particularly when combined with folate, exhibits antioxidant activity in vivo [333]. In addition to its fundamental functions, cobalamin provides a range of benefits for overall health. It helps regulate mood and prevent depression, enhances brain health and cognitive function, and may positively impact heart health [79, 80].

Low serum cobalamin levels have been associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis [336, 337]. Besides, low serum cobalamin levels, particularly low holotranscobalamin (Cbl–TCII, active form of cobalamin in serum) levels, are associated with an increased risk of AD [338, 339]. In the nervous system, cobalamin acts as a coenzyme in myelin synthesis. Deficiency of cobalamin consequently impairs myelin synthesis, resulting in various dysfunctions within both the central and peripheral nervous systems [81].

Cobalamin deficiency also can manifest with neuropsychiatric syndromes even in the absence of hematological signs. Notably, mood disorders such as depression and mania, chronic fatigue syndrome, and psychosis can occur [340]. Additionally, cobalamin is essential for the synthesis of SAM which is recognized for its antidepressant properties [341].

Due to their involvement in various cellular processes, many vitamin Bs are known for their important roles in cancer prevention and treatment. Thiamine supplementation exhibits a dual effect on cancer cell survival and proliferation. At low to moderate doses, 12.5 to 75 times the recommended daily allowance (RDA), thiamine has been demonstrated to promote cancer cell proliferation [342]. However, at high doses (

Since disrupted oxidative metabolism is indeed one of critical factors in the development of cancer, thiamine could be applied to prevent or treat cancers [345]. Thiamine and its derivative, TPP, are essential for glutathione production directly impacting cancer cell oxidative stress and prosurvival responses [346, 347]. Besides, thiamine’s role in cellular metabolism contributes to the intricate interplay between oxidative stress and cancer development [102]. Tumor cells typically exhibit higher levels of ROS compared to healthy cells which play crucial roles in tumor cell transformation, proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, and metastasis [348, 349, 350]. Simultaneous delivery of anticancer drugs and thiamine effectively inhibited the cancer cell growth [351]. Furthermore, when administering the highest thiamine dose (approximately 2500 times of the dose of the RDA) 7 days before tumor inoculation, tumor growth was prohibited by 36% [343]. Moreover, thiamine deficiency is linked to gastrointestinal and hematological cancers due to decreased absorption and accelerated thiamine metabolism [352, 353]. An increased risk of colon cancer was observed with thiamine deficiency, possibly due to enhanced genotoxic

Riboflavin serves as a cofactor and is an integral component of two important coenzymes: FAD and FMN [355, 356]. These coenzymes enhance one-carbon metabolism, maintain mucous membranes, and have been implicated in preventing inflammatory bowel diseases and reducing the risk of colorectal cancer [357]. Additionally, a case-control study conducted in China found that increased dietary riboflavin intake was associated with a decreased risk of esophageal cancer [358]. Riboflavin (vitamin B2), combined with thiamine (vitamin B1) and niacin (vitamin B3), may also collectively contribute to cancer inhibition. This involvement could be attributed to their roles as cofactors in folate metabolism or their independent roles in DNA synthesis, maintenance of genomic stability, DNA repair, and regulation of cell division and apoptosis [139, 359, 360].

Moreover, a potent inhibitory effect of riboflavin on melanoma metastasis formation in the lung was observed in an animal model [361]. Riboflavin is linked to a potential reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer among women. A low intake of riboflavin may disturb the activity of MTHFR, potentially contributing to colorectal cancer [57]. In post-menopausal women, the intake of riboflavin and vitamin B6 is also associated with a decreased risk of colorectal cancer [362]. In addition, the dietary supplement riboflavin can be selectively and efficiently photosensitized to induce cell death in human breast adenocarcinoma cells SK-BR-3 and exert a tumoricidal effect on grafted SK-BR-3 tumors in immunodeficient mice [363]. Riboflavin was also demonstrated to suppress solid tumor growth by inhibiting the expression of tumor-promoting factors [364]. The irradiated riboflavin inhibited matrix-degrading proteases, leading to the downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the upregulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), indicating its potential as an antimetastatic agent [364]. Riboflavin deficiency may elevate carcinogenesis risk by increasing carcinogen binding, as indicated by research on carcinogen-DNA binding [365].

Niacin has been shown to mitigate the development of colon cancers, likely due to its antiinflammatory effects [366, 367]. Niacin was able to decrease the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-

Nicotinamide (NAM) is a variant of niacin which mediates effects against various neoplasms including inhibiting tumor growth, promoting cell death, or suppressing tumor metastasis [372]. NAM has been demonstrated to enhance the repair of UV radiation-induced DNA damage, which is one of the components contributing to UV-driven carcinogenesis, in primary human keratinocytes [373, 374]. Clinical trials using NAM have supported that niacin effectively mediates chemoprevention against non-melanoma skin cancer [375, 376]. NAM may limit the development of cancer by maintaining normal cellular energy metabolism. Disruptions in energy metabolism have been linked to the transformation of normal cells into cancerous ones and the progression of tumors in various tissues [377, 378]. Also, deficiency of niacin may disrupt DNA damage/repair mechanisms when exposed to chemical carcinogens. This potentially contributes to carcinogenesis as NAD+, dependent on niacin, is essential for DNA damage protection [379, 380].

In cancer treatment, pantothenic acid may play a role through its involvement in several metabolic pathways. Pantothenic acid supplementation has been investigated as a potential adjunctive therapy in cancer treatment although more research is needed to understand its specific mechanisms and effectiveness [381]. It also has been demonstrated to offer protection against ROS, suggesting a potential role in cancer prevention [184]. The previous findings, along with their observations on the protective effects of pantothenic acid and its derivatives against ROS-induced cell and tissue injury, suggest their potential as valuable tools to reduce oxidative stress [382].

CoA, synthesized from pantothenic acid, is essential for cellular metabolism, including fatty acid synthesis, energy production, and regulation of gene expression. Alterations in CoA metabolism have been linked to cancer development and progression [383]. Pantothenic acid and CoA act essential roles in stimulating anticancer immune responses by enhancing the production of Tc22 and IL-22 cells as well as activating immune-related gene expression factors [381]. Besides, they stimulate T-cell responses against cancer, likely by promoting the differentiation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [384]. In mice, periodic injections of pantothenic acid enhance the effectiveness of PD-L1–targeted cancer immunotherapy, and in vitro culture of T cells with CoA enhances their antitumor activity [385].

Vitamin B6 also has been investigated for its potential in colorectal cancer prevention and treatment, possibly due to its involvement in multiple biological reactions including DNA synthesis and repair, inhibition of cell proliferation, enhancement of chemotherapy cytotoxicity, and modulation of gene expression [386, 387]. For instance, pyridoxine has been demonstrated to inhibit the growth of both murine and human melanoma cell lines. Also, its vitamers pyridoxal exhibited significantly greater effects compared to pyridoxine [388].

Epidemiological studies demonstrated a negative correlation between vitamin B6 levels and the risk of developing cancer. Specifically, an increased intake of vitamin B6 and elevated blood levels of PLP were associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer [389]. Conversely, inadequate intake of vitamin B6 has been linked to an elevated risk of cancer [390], while dietary intake of vitamin B6 has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer [391]. Furthermore, vitamin B6 has the ability to inhibit the proliferation of monocytic lymphoma cells and exert antitumor effects [392]. Additionally, the Schiff base Mn(II) complex derived from vitamin B6 holds the potential as an effective therapeutic agent for combating breast cancer [18]. In liver cancer, several clinical trials have also observed an antihepatocellular carcinoma effect through direct supplementation of vitamin B6 [393, 394]. Besides, vitamin B6 assumes a necessary role in the kynurenine pathway by serving as a cofactor for the enzyme kynureninase. This pathway is responsible for generating antiinflammatory molecules like kynurenine [392]. Maintaining an optimal level of kynureninase, along with its cofactor, can effectively impede cancer progression in vivo [395].

Folate significantly contributes to DNA synthesis, repair, and methylation, providing a mechanistic basis for its potential involvement in cancer prevention [359]. Folate is integral to one-carbon metabolism, used by cells for DNA synthesis and methylation. Thus, these nutrients can influence pathways that promote cancer cell proliferation and modulate DNA, affecting the likelihood of developing neoplastic cells [396]. As folate mediates DNA synthesis and methylation via one-carbon reactions, deficiency of it may initiate carcinogenesis in normal tissues [397]. Epidemiological study have linked low folate intake to an increased risk of epithelial cancers, such as colorectal cancer and cervical cancer [359]. As of now, a substantial body of epidemiological evidence consistently suggests that individuals with high folate status, as measured by either elevated dietary intake or blood concentrations, tend to exhibit a decreased risk of colorectal cancer [398, 399, 400, 401, 402]. This robust consensus underscores the potential protective effect of folate against the development of colorectal cancer. Adequate folate intake appears to act a critical role in maintaining normal patterns of DNA methylation and minimizing DNA damage [403]. Folate levels in plasma have been observed to inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of breast cancer cells, thereby reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence and metastasis [404]. An inverse association between dietary folate intake and the risk of breast cancer has been reported, particularly a decreased risk of breast cancer among women who do not regularly consume alcohol and have a high folate consumption [405]. Moreover, a folate deficiency may lead to hypermethylation occurring at specific sites within the promoter regions of particular tumor suppressor genes by silencing these genes and contributing to cancer development [406, 407]. Folate plays a vital role in DNA synthesis by facilitating the conversion of deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP). Consequently, a low folate level may result in uracil misincorporation in DNA, potentially inducing DNA breaks and increasing the risk of carcinogenesis [408].

One of the benefits of cobalamin is its potential role in reducing the risk of cancer. Studies have indicated that individuals with lower levels of cobalamin may have an increased risk of developing certain types of cancers, including breast cancer [409], lung cancer [410], and colorectal cancer [411]. Specifically, according to a prior study, increasing plasma levels of cobalamin, either alone or in combination with other factors related to one-carbon metabolism, may lower the risk of rectal cancer [412]. Several biological mechanisms have been proposed to elucidate the inverse relationship between cobalamin levels and cancer development. Similarly to folate, cobalamin also plays a pivotal role in cancer prevention by supporting DNA synthesis and repair, regulating gene expression, and enhancing immune function [413]. In addition, at the cellular level, cobalamin has an important role in one-carbon metabolism, a critical pathway involved in DNA synthesis, methylation reactions, and redox metabolism. Thus, cobalamin may play a role in influencing pathways that could potentially contribute to the enhanced proliferation of cancer cells [16, 17].