1 Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, 47500 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

2 Neuropharmacology Research Laboratory, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, 47500 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

3 School of Dentistry and Medical Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia

Abstract

Neurotrauma plays a significant role in secondary injuries by intensifying the neuroinflammatory response in the brain. High Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB1) protein is a crucial neuroinflammatory mediator involved in this process. Numerous studies have hypothesized about the underlying pathophysiology of HMGB1 and its role in cognition, but a definitive link has yet to be established. Elevated levels of HMGB1 in the hippocampus and serum have been associated with declines in cognitive performance, particularly in spatial memory and learning. This review also found that inhibiting HMGB1 can improve cognitive deficits following neurotrauma. Interestingly, HMGB1 levels are linked to the modulation of neuroplasticity and may offer neuroprotective effects in the later stages of neurotraumatic events. Consequently, administering HMGB1 during the acute phase may help reduce neuroinflammatory effects that lead to cognitive deficits in the later stages of neurotrauma. However, further research is needed to understand the time-dependent regulation of HMGB1 and the clinical implications of treatments targeting HMGB1 after neurotrauma.

Keywords

- high mobility group box-1

- neurotrauma

- neuroinflammation

- cognition

Neurotrauma refers to the sudden disruption of central nervous system (CNS) functioning or the development of new CNS pathology due to applied external forces [1, 2]. It represents a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, affecting both the young and the elderly. Two major events classified under neurotrauma include traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke. In the United States, TBI alone impacts approximately 2.8 million individuals annually [2]. Within the realm of trauma-related injuries, TBI is often referred to as a silent epidemic because the resulting impairments may not be immediately visible [2]. Previous studies have provided compelling evidence that individuals who survive a TBI may experience persistent consequences, including memory issues and neuropsychological challenges that initiate an ongoing, potentially lifelong process affecting multiple organ systems, possibly leading to the development or acceleration of various other neurological diseases [3], such as neurodegenerative diseases or epilepsy.

Stroke, on the other hand, is a global epidemic that affects 1 in 4 adults over the age of 25 which poses a significant individual, societal and economic burden as well [4]. Moreover, the study has shown that TBI can result in stroke, where any damage to the brain typically results in impairment to the vascular system. A stroke, caused by a disruption in the brain’s blood supply, is a cerebrovascular event resulting in the loss of brain function, thereby neurotrauma [4]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that damage to the cerebrovascular system in the head caused by TBI could potentially increase the risk of stroke, either through bleeding from an artery (haemorrhagic stroke) or the formation of a clot at the site of injury that obstructs blood flow to the brain (ischemic stroke) [5, 6]. Cognitive impairments after neurotrauma poses a significant economic burden and leads to overall poor quality of life when patients are unable to return to work after the injury [7]. One study found high rates of morbidity and unemployment rates in patients who suffered a minor form of head injury 3 months post-trauma [8]. Approximately 30% of stroke patients have been found to develop dementia which mainly affects the domains of attention, memory, language and orientation within 1 year of the stroke onset [9]. Cognitive impairment may be the most significant comorbidity post neurotrauma as it affects a survivor’s quality of life, mainly in terms of their ability to carry out daily activities independently, readapting to social life, resumption of work and return to premorbid family roles [10].

Neuroinflammation occurs as a secondary response to neurotrauma which contributes to persistent and ongoing cognitive deficits and neurodegeneration [11]. This can be attributed to activation of microglia and astrocytes, leukocyte recruitment and migration via the blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption and the increase in neurotoxic or neuroprotective inflammatory mediators [12]. Damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by injured neurons during neuroinflammation tend to interact with toll like receptors (TLRs) on activated microglial cells in order to induce the release of inflammatory mediators. These mediators in turn leads to further upregulation microglial activation, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that ultimately leads to chronically dysregulated microglial activation and the release of neurotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain, thus precipitating neurodegeneration [11, 13].

A key molecule that is involved in secondary insults to the brain following neurotrauma includes High Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB1), a non- histone chromatin protein released by damaged cells which signals cellular damage and amplifies neuroinflammation [14]. Kang et al. [15] describes intranuclear HMGB1 as “a DNA chaperone which bends DNA and modulates crucial DNA events such as repair, replication, transcription, recombination and genomic stability”. HMGB1 that is secreted extracellularly binds to the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), which signals cell damage and acts as an inflammatory mediator. The ability of HMGB1 to be secreted out of the cell depends on whether the cell undergoes necrosis or programmed cell death [16]. HMGB1 is released from the nucleus and cytoplasm of the injured cell when cell lysis occurs. HMGB1 acts by binding to a variety of cell surface receptors to trigger immune cell chemotaxis and the release of proinflammatory cytokines. These surface receptors include RAGE, TLR2, TLR4 and TLR9 [17, 18, 19]. To date, the role of RAGE and TLR4 have been widely studied [20]. For example, the binding of HMGB1 to TLR4 further stimulates HMGB1 release. This signalling creates a self-perpetuating cycle, which further amplifies the neuroinflammatory response in the human brain [21].

HMGB1 binding to TLR4 also varies in necrotic and apoptotic cells. This can be attributed to its varied redox states. A reduced form of HMGB1 released in necrotic cells is required in order for it to activate TLR4, whereas HMGB1 released during programmed cell death is oxidised rendering it unable to bind with TLR4 signalling receptors. Hence inflammatory responses are only triggered in necrotic cells alone [22]. HMGB1 has been studied as a biomarker that can prognosticate TBI as evidenced by similarities in prognostic values of HMGB1 and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [23]. There have been limited studies with regards to HMGB1 and cognition in the setting of overall neurotrauma. HMGB1 may be a promising target for neurotrauma initiated cognitive decline treatment in future studies. Therefore, this review aims to determine the role of HMGB1 in cognition in the setting of neurotrauma and to explore the potential for HMGB1 as a target for treatment and prevention of neurocognitive decline by summarizing and critically appraising the currently available literature on their pathological relationship.

A total of 1854 articles were retrieved from the initial literature database search where a total of 1322 articles were excluded due to duplicates and non-original research articles. An additional 513 articles that did not discuss HMGB1 in relation to cognition as well as articles unrelated to the subject of neurotrauma related cognitive deficits were also excluded. The remaining 19 studies, summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]), were included for critical appraisal. All 19 articles were pre-clinical studies investigating the relationships between HMGB1 and cognitive deficits in the context of neurotrauma. These studies included 11 on traumatic brain injury (TBI), 6 on stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic), and 2 on hypoxia-induced neurotrauma.

| Type of Neurotrauma | Sample Characteristics | HMGB1 Findings | Cognitive Findings | Mechanisms Involved | Study |

| TBI | RAGE and TLR4 | Aneja et al. 2019 [24] | |||

| TBI | IL-1 signaling. | Chung et al. 2019 [25] | |||

| TBI | TLR and RAGE | Teng et al. 2015 [26] | |||

| TBI | TLR4 | Wang et al. 2020 [27] | |||

| TBI | TLR4 | Webster et al. 2019 [28] | |||

| TBI | RAGE | Okuma et al. 2014 [29] | |||

| TBI | NA | Simon et al. 2018 [30] | |||

| TBI | RIP1/R IP3-M LKL signaling pathway | Bao, et al. 2019 [31] | |||

| TBI | TLR4 | Wang et al. 2013 [32] | |||

| TBI | NF- |

Xu et al. 2020 [33] | |||

| Stroke-Hemorrhagic | RAGE and TLR4 | Bahader et al. 2021 [34] | |||

| Stroke-Ischemia | TLR4/NF- |

Wang and Yang, 2020 [35] | |||

| Stroke-Ischemia | NA | Du et al. 2019 [36] | |||

| Stroke-Ischemia | NA | Hei et al. 2018 [37] | |||

| Stroke-Ischemia | NF- |

Zhang et al. 2020 [38] | |||

| Stroke-Ischemia | NA | Zhang et al. 2019 [39] | |||

| Hypoxia | TLR4 | Das et al. 2018 [40] | |||

| Hypoxia | TLR4, NF- |

Pascual et al. 2011 [41] | |||

Abbreviations: HMGB KO, High Mobility Group Box Knockout; WT, Wild Type; CCI,

Controlled Cortical Impact; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products;

TLRs, toll-like receptors; TBI, Traumatic Brain Injury; CHI, Closed Head Injury;

IL-1R KO, Interleukin-1 Receptor Knockout; Db, Diabetic; ICH, Intracranial

Haemorrhage; Au, Aucubin; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2; Gly,

Glycyrrhizin; Nle4, D-Phe7, NDP-melanocortin analogue; A20, Tumor necrosis factor alpha induced protein

3; Nec-1, Necrostatin-1; SAH, Subarachnoid Haemorrhage; SD, Sprague Dawley; BDNF,

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; MSCs-Exo, mesenchymal stem cell-derived

exosome; PBS, Phosphate Buffered Saline; SSa, Saikosaponin A; MCAO, Middle

Cerebral Artery Occlusion; tGCI/R, Transient Global Cerebral Ischemia

Reperfusion; FC, Fluorocitrate; PFC, Prefrontal Cortex; HI, Hypoxia Ischemia; Ab,

Antibody; NA, not available; AAV, adeno-associated virus; NF-

The role of HMGB1 as an inflammatory biomarker in neurotrauma associated cognitive impairment was explored in the studies selected for this review. The studies cited explored the effects of therapeutics such as Melatonin, Nec-1, Aucubin, Thalidomide, Minocycline, Glycyrrhizin, Saikosaponin A, Necrostatin-1, melanocortin analogue and celastrol on hippocampal, cortical, serum and cerebrospinal serum fluid (CSF) HMGB1 levels. Subsequently, the effects of disease modalities such as hypoxia, stroke and traumatic brain injuries on spatial memory, working memory, spatial learning and recognition memory were explored. A total of 10 studies were conducted using Sprague Dawley rat models, 3 studies utilized of C57BL/6 mice, 1 study consisted of HMGB1-knockout (KO) transgenic mice, 1 study consisted of Wistar rats, 1 study consisted of interleukin (IL)-1 receptor KO transgenic mice, 1 study consisted of BALB/c mice and 2 studies consisted of ICR mice. Thirteen of these studies consisted of adult mice between 6 weeks to 24 months of age. Four studies consisted of younger mice of less than 6 weeks. The age of mice used in the remaining studies were unspecified. Male mice were used in 18 of the experimental models. The sex of subjects used in 1 study was unspecified.

The majority of non-treatment based studies showed increased HMGB1 upregulation and decreased cognitive performance of mice that experienced TBI, stroke and hypoxic injury. Hippocampal HMGB1 levels were reduced across all intervention groups studies. Subjects belonging to the treatment arm in the majority of these studies showed significant improvement in spatial learning and memory acquisition.

Overall, the currently available literature provided clear evidence regarding the role of HMGB1 as a key mediator and link between neurotrauma and the consequent neuroinflammation that may have led to neurotrauma-related cognitive impairment. The studies (Table 1, Ref. [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]) demonstrated an increased HMGB1 expression within the hippocampus of rats postinjury and this was linked with an increased susceptibility to impairments in spatial learning and memory acquisition. Furthermore, the literature also showed that the suppression of HMGB1 ameliorated the cognitive deficits and that it may have potential for the development of targeted therapy to improve cognitive outcomes in a clinical setting of neurotrauma.

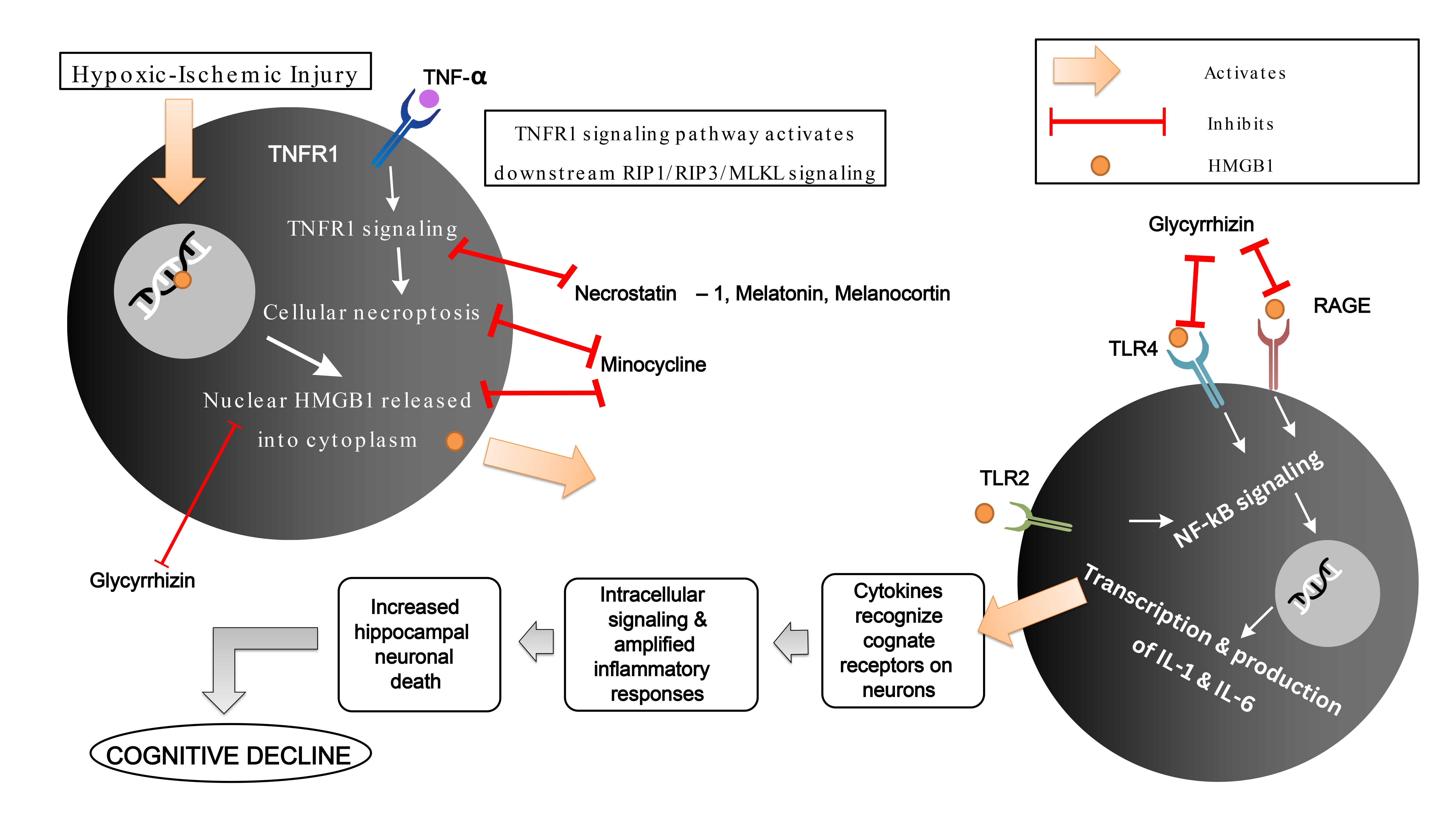

High Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB1) is a protein that behaves as a nuclear factor

that is secreted extracellularly by activated monocytes and macrophages during

necrosis and cellular damage. Within the nucleus, it modifies the structure of

the DNA via chromatin bending in order to initiate the assembly of DNA targets

[15]. HMGB1 that is secreted extracellularly binds to the various receptors such

as RAGE, TLR4 and TLR2 which signals cellular damage and behaves as an

inflammatory mediator [17, 41, 42]. HMGB1 binding to these receptors leads to

NF-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A potential mechanism of HMGB-1 induced cognitive decline in

neurotrauma via TLR4/TLR2/RAGE/NF-

HMGB1 in various oxidative or reductive forms serve various purposes during the

inflammatory cascade in the brain during an insult. Disulphide HMGB1-induced

cytokine production mediates the activation of NF-

A study on the effect of Glycyrrhizin on HMGB1 showed that HMGB1 inhibition led

to a reverse in hypoxic-ischemic-induced myelination disorder and hippocampal

neuronal loss via the TLR4/RAGE/NF-

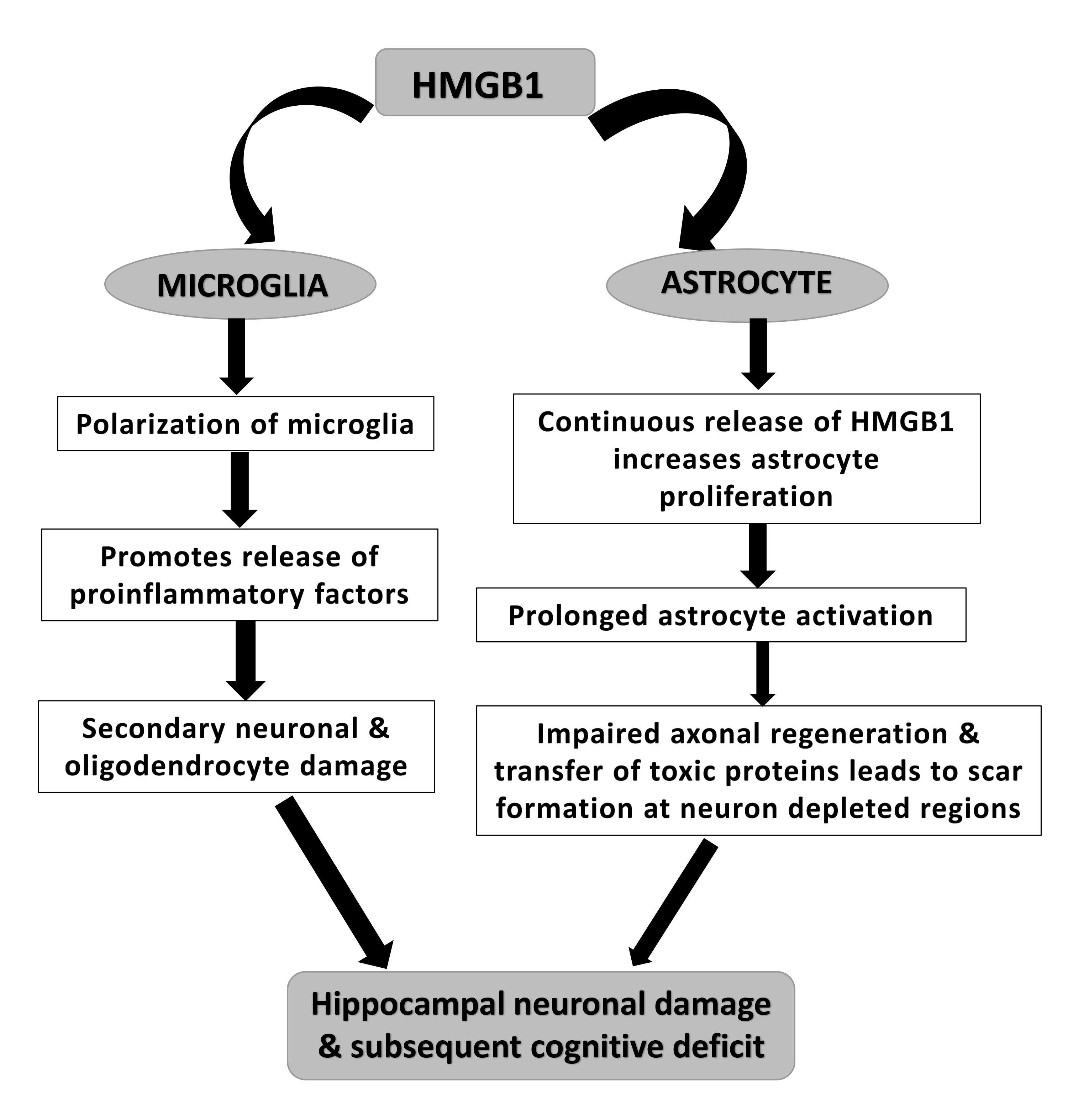

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A potential mechanism of HMGB-1 induced cognitive decline in neurotrauma via loss of healthy hippocampal neurons due to microglial and astrocyte activation.

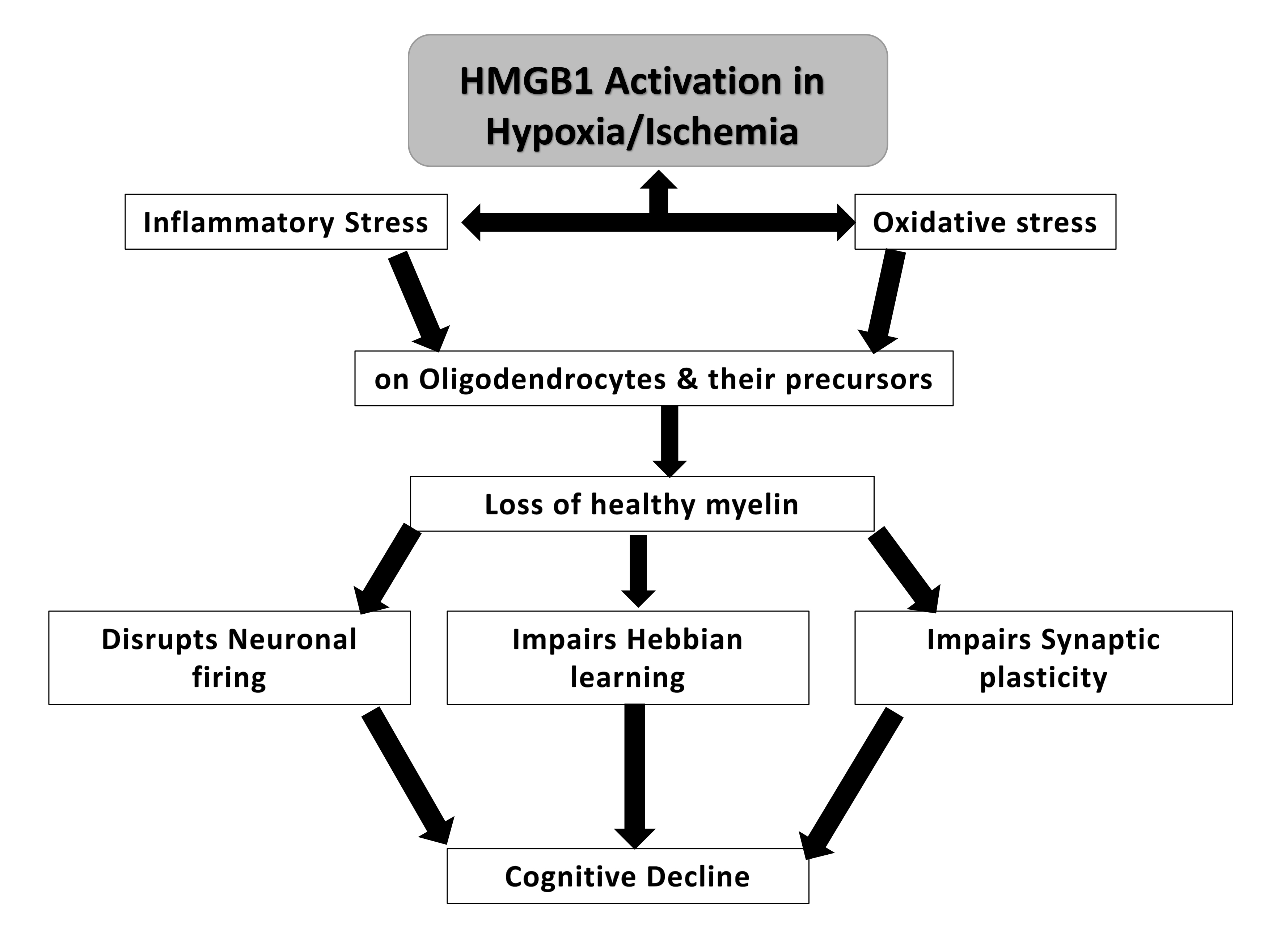

The loss of healthy myelin has been proposed to lead to cognitive decline. HMGB1 was postulated to increase inflammatory and oxidative stress upon oligodendrocytes, which play a role in myelin formation [49]. The loss of healthy myelin that follows could potentially lead to changes in neuronal firing, synaptic plasticity and Hebbian learning, which is a mechanism by which neurons become more efficient at communicating when they are repeatedly activated together. However, when myelin is damaged, this process can be disrupted, leading to further cognitive impairment [50, 51] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

A potential mechanism of HMGB-1 induced cognitive decline in neurotrauma via loss of healthy myelin.

HMGB1 was postulated to increase blood brain barrier permeability in neurotrauma in many studies. Using HMGB1 KO mice and Wild Type (WT) mice, Aneja and colleagues [24] studied the effect of HMGB1 loss on tissue sparing and cognition post Controlled Cortical Impact (CCI) and described that naive HMGB1 KO mice after TBI exhibited no difference in performance in spatial memory testing compared to WT mice when cognitive improvement was expected in the absence of HMGB1 in the mice. Aneja and colleagues [24] postulated that these differences could be attributed to differences in species studied (rat model vs mouse model) and differences in models and severity of the injuries. Despite the absence of HMGB1, blood brain barrier permeability increased 24 h post injury, indicating that other DAMPs besides HMGB1 may have played a role in increasing BBB permeability [24].

BBB breakdown has been postulated to cause the increase of blood related immune cell chemotaxis into the brain that leads to activation of resident immune CNS cells and subsequent inflammatory amplification [52]. However, HMGB1 may not be the only DAMPs involved in mediating BBB breakdown. Chung and colleagues [25] and Teng and colleagues [26] found an increase in HMGB1 level post TBI in the setting of CCI or Closed Head Injury (CHI) and alcohol exposure post TBI respectively, both of which were associated with poorer cognitive outcomes. Teng and colleagues [26] speculated that the increase in HMGB1 expression could signify that neuroinflammatory processes were aggravated by alcohol ingestion post TBI via astroglial activation and enhanced release of proinflammatory cytokines, which ultimately led up to increased secondary injuries. Teng and colleagues [26] established a significantly positive correlation between HMGB1 and Neurological Severity Score (NSS), suggesting that HMGB1 release may have contributed to neuroinflammatory processes and further exacerbated neurocognitive decline.

Bahader and colleagues [34] proposed that ICH increased the induction of proinflammatory cells and mediators such as HMGB1, which in turn led to higher proportion of glial and astrocytic activation and an increase in oxidative and nitrosative stress, leading to raised hematoma volume and severe neurological and cognitive deficits via TLR4 and RAGE receptor activation [27, 53].

Thus, it is acknowledged that intracellular HMGB1 plays a role in repair and

regulation of autophagy, whereas extracellular HMGB1 acts as a trigger and

enhancer of neuroinflammation. The initiation of neuroinflammatory responses

often stems from inherent “damaging” events. During neuroinflammation, HMGB1 is

primarily secreted by activated microglial cells. This secretion induces

heightened release of inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factors

(TNF)-

Wang and colleagues found that Aucubin (Au) treated mice had lower HMGB1 expression and improved cognitive outcomes when compared to mice that did not receive treatment. It was postulated that Au reduced oxidative stress by inhibiting intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increasing the concentration of serum and brain enzymes that inhibit ROS synthesis [27]. Au, by reducing oxidative stress in the hippocampus has a potential to reduce neuronal loss and alleviate cognitive deficits in secondary injuries induced by TBI. This suggests that HMGB1 may lead to downstream increase in oxidative stress which may exacerbate neuronal injury and death, leading to cognitive decline.

Simon and colleagues found that Minocycline’s ability to block the translocation

of HMGB1 reduced microglial activation within the thalamus post TBI. This may

have had a neuroprotective effect via inhibition of nuclear HMGB1 release and

subsequent cytoplasmic HMGB1 release from the lysed injured cell leading to

better cognitive outcomes in the treatment group, similar to that of Gly [30]. In

another experiment conducted by Bao and colleagues, Nec-1 and Melatonin were

found to reduce necroptosis in an A-20 (TNF) dependent manner [31]. In other

words, the inhibition of HMGB1, RAGE, NF-

TLR4 activation and subsequent direct NF-

Wang, X and colleagues found that Saikosaponin (SSa) pretreatment attenuated the

increase in HMGB1 and nuclear NF-

Du and colleagues [36] also explored the effect of Minocycline but global cerebral ischemia (GCI). In this study, Minocycline (MIN) was noted to significantly reduce serum HMGB1 levels, the release of its downstream inflammatory mediators and subsequent microglial activation. However in this study, no significant cognitive improvement was observed, but a trend of cognitive improvement was seen in the group that received MIN [36]. This may have been attributed to cognitive function being studied in the short term similar to that of Okuma and colleagues [29].

Studies showed that Glycyrrhizin (Gly) treatment reduced the expression of HMGB1 and prevented and improved cognitive decline. Webster and colleagues found that Gly reduced brain HMGB1 treatment and reduced brain edema on the ipsilateral side of the injury, a hallmark feature of neuroinflammation [58, 59]. However, this finding was limited to mice receiving treatment prior to injury and within 1 hour after the injury, suggesting that Gly may have beneficial effects in TBI in a very acute setting [29]. Gly also was shown to have beneficial effects on cognition in terms of cognitive outcomes. The neuroprotective effects of Gly were hypothesized to be attributed to the downregulation of HMGB1 via TLR4 inhibition and the subsequent decline in hippocampal microglial activation [53]. Similar results were observed in a study conducted by Okuma and colleagues [29], who postulated Gly caused RAGE inhibition in an acute setting. In this experiment however, Gly’s beneficial effects ceased at most after 7 days. However, studies about cognition were not conducted after 7 days and therefore the long term effects of Gly were not established in this study and have not been investigated in previous literature as well.

In another experiment, Fluorocitrate (FC) aided stroke induced memory impairment via structural alterations in astroglial cells [39]. It was also noted that HMGB1 was raised in a biphasic manner (3 days and 2 weeks postoperatively) and that FC administration had to be done in a prudent manner as HMGB1 played the role in mediation of neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation depending on the stages of cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury [60]. Therefore, it was suggested that FC treatment was best avoided during the recovery phase of ischemic stroke, in order to promote HMGB1 mediated neurological remodelling [39]. Similarly, in another study, it was found that raised HMGB1 levels of hippocampal cornu ammonis (CA1) neurons occured 3 days after surgery could suggest that HMGB1 release occurred in the acute phases of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) and that hippocampal HMGB1 likely originates from CA1 neurons. The study also found that remarkable neuronal loss and cognitive impairment occurred in the control group during the chronic phases of CCH, indicating that acute treatment of neurotrauma could potentially ameliorate cognitive deficits in the chronic phases of the disease [37]. This could potentially explain why across the majority of studies, targeted therapy in the acute phases of neurotrauma led to improvement of cognitive outcomes over the long term.

Based on these selected studies, HMGB1 appears to be a crucial mediator of the

neuroinflammatory processes in the hippocampus that occur during/post-

neurotrauma, which functions via the stimulation of TLR4/RAGE/NF-

HMGB KO, High Mobility Group Box Knockout; WT, Wild Type; CCI, Controlled Cortical Impact; TBI, Traumatic Brain Injury; CHI, Closed Head Injury; IL-1R1 KO, Interleukin-1 Receptor Knockout; Db, Diabetic; ICH, Intracranial Haemorrhage; Au, Aucubin; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2; Gly, Glycyrrhizin; Nle4, D-Phe7, NDP-melanocortin analogue; MSH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone; A20, Tumor necrosis factor, alpha induced protein 3, Nec-1, Necrostatin-1; SAH, Subarachnoid Haemorrhage; SD, Sprague Dawley; BDNF, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; MSCs-Exo, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes; PBS, Phosphate Buffered Saline; SSa, Saikosaponin A; MCAO, Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion; tGCI/R, Transient Global Cerebral Ischemia Reperfusion; FC, Fluorocitrate; PFC, Prefrontal Cortex; HI, Hypoxia Ischemia; Ab, Antibody.

TR, AA and MFS have conceptualized and designed the study. LN performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. TR and LN collected and assembled the data. LN, TR, AA and MFS analyzed the articles. TR, AA and MFS revised manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript version. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received funding from the Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Seed Grant 2022 and the Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Seed Grant 2023.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Given his role as a Guest Editor, Mohd. Farooq Shaikh had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Thomas Heinbockel.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.