1 Organ Transplantation Center, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, 266003 Qingdao, Shandong, China

2 The Institute of Transplantation Science, Qingdao University, 266003 Qingdao, Shandong, China

3 Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Department, Affiliated First Hospital of Ningbo University, 315000 Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Liver cancer is a highly lethal malignancy with frequent recurrence, widespread metastasis, and low survival rates. The aim of this study was to explore the role of Endoglin (ENG) in liver cancer progression, as well as its impacts on angiogenesis, immune cell infiltration, and the therapeutic efficacy of sorafenib.

A comprehensive evaluation was conducted using online databases Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), 76 pairs of clinical specimens of tumor and adjacent non-tumor liver tissue, and tissue samples from 32 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients treated with sorafenib. ENG expression levels were evaluated using quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR), Western blot, and immunohistochemical analysis. Cox regression analysis, Spearman rank correlation analysis, and survival analysis were used to assess the results. Functional experiments included Transwell migration assays and tube formation assays with Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

Tumor

cells exhibited retro-differentiation into endothelial-like cells, with a

significant increase in ENG expression in these tumor-derived endothelial cells

(TDECs). High expression of ENG was associated with more aggressive cancer

characteristics and worse patient prognosis. Pathway enrichment and functional

analyses identified ENG as a key regulator of immune responses and angiogenesis

in liver cancer. Further studies confirmed that ENG increases the expression of

Collagen type I

This study found that ENG is an important biomarker of prognosis in liver cancer. Moreover, ENG is associated with endothelial cell differentiation in liver cancer and plays a crucial role in formation of the tumor vasculature. The assessment of ENG expression could be a promising strategy to identify liver cancer patients who might benefit from targeted immunotherapies.

Keywords

- liver cancer

- human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

- neovascular

- immune cell infiltration

- Endoglin (ENG)

Liver cancer has a high mortality rate and more effective therapeutics are therefore urgently required [1]. As well as having a high incidence, it also has a very poor 5-year survival rate, making it a significant public health concern [2]. The frequent recurrence and widespread metastasis of liver cancer are the main obstacles for long-term patient survival [3]. Despite improvements in technology, there is an ongoing research effort worldwide to develop more effective therapies against this cancer type [4]. Recent investigations have focused on the microenvironment of liver cancer due to its role in tumor cell escape and the suppression of immune defense mechanisms. The latter significantly diminishes the capacity of immune cells to fight cancer [5, 6, 7]. Although the liver microenvironment is complex, it is prone to rapid systemic dissemination of tumor cells, primarily due to the nature of the liver tissue vasculature [8]. Angiogenesis is an early hallmark of solid tumors and involves the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing endothelial cells (ECs) under favorable conditions [9]. Angiogenic activity promotes the growth and progression of tumors, which then become more invasive and develop a remarkable ability to metastasize. A reciprocal interaction takes place between the tumor cells and ECs in the neovasculature, whereby the stimulation of growth and survival alternates from one to the other. Tumor cells are known to produce specific cytokines that stimulate the growth of vascular ECs, which in turn deliver critical supplies of oxygen and nutrients to the tumor [10]. In-depth studies using glioblastoma models in mice have shown that vascular ECs can be derived directly from tumor cells and express human chromosomal markers upon xenografting [11]. This observation provides strong evidence for the plasticity of tumor cells during angiogenesis. Therefore, we hypothesize that inhibition of angiogenesis could be a potentially effective strategy in the treatment of liver cancer.

Endoglin (ENG), also known as the marker CD105, is strongly expressed on the surface of adult vascular ECs and primarily functions to promote angiogenesis in tumor tissue [12]. The expression of ENG increases during periods of high EC proliferation, especially in vitro proliferation, suggesting that it plays a crucial role in this process [13]. ENG is also expressed in tumor tissues, particularly during the critical phases of angiogenesis and vascular remodeling where it is a specific marker of angiogenic activity [14, 15]. ENG is differentially expressed in neovascular ECs in liver cancer tissue compared to normal tissue, indicating that it may be an accurate biomarker of angiogenesis in liver cancer [16]. Sorafenib is a targeted anti-angiogenic agent used in the clinic for the treatment of advanced liver cancer. It works by inhibiting Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR), Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR), and C-kit in a set of crucial signaling pathways involved in angiogenesis [17, 18, 19]. The impact of ENG on the efficacy of sorafenib in curbing tumor progression has yet to be definitively established, despite its important inhibitory role in oncological treatments. This study explored the specific mechanisms of tumor cell transdifferentiation into endothelial-like cells and the correlation between high ENG expression and the response to sorafenib treatment. We hypothesize that inhibiting angiogenesis through ENG could be a potentially effective strategy for treating liver cancer, providing a novel approach for liver cancer therapy.

A comprehensive dataset and clinical samples for 76 pairs of tumor and adjacent

non-tumor liver tissues was collected from January 2020 to September 2021 at the

Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (Supplementary Table 1). The

collection of specimens and associated research procedures were approved by the

Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University

(Approval Identifier: QYFYWZLL26589). Informed consent was obtained from

participants or their legal representatives before the start of any research

activity. For the animal experiments, 5-week old male Balb/c nude mice were

procured from SPF Biotechnology (Beijing, China), ensuring compliance with

ethical guidelines. The mice were maintained in an individually ventilated caging

(IVC) system to promote their well-being. Subsequently, 5

In addition, 32 liver cancer patients who were administered sorafenib were subjected to computed tomography (CT) imaging and their tissue specimens quantitatively assessed for ENG expression (Supplementary Table 2). Patients with high and low ENG expression in liver cancer were selected, and CT was used to assess changes in tumor diameter before and after treatment with sorafenib. All results were evaluated by three specialized radiologists.

Proteins from cellular extracts and tissue samples were isolated using

Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay (d) solution (R0010, Solarbio, Beijing, China).

The protein samples were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and immediately transferred

onto Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Prior to the application of

antibody, the membranes were first blocked using 5% non-fat milk. For the

detection of specific proteins, the membranes were probed with a series of

primary antibodies as follows: anti-ENG (1:2000 dilution, ab169545, Abcam,

Cambridge, UK), anti- Collagen type I

The cell lines Huh7 and HepG2, representative of liver cancer,

as well as human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), were purchased from the China Center for Type Culture

Collection (CCTCC, Wuhan, China). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle

Medium (DMEM) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 100

Lentiviral shRNA and vectors for the knockdown of ENG (sh-ENG) and

overexpression of COL1A1 (OE-COL1A1) were designed and constructed by Genechem

(Shanghai, China). The interference sequences are as follows: sh-ENG-1:

GATCTGGACCACTGGAGAATATT CAAGAGATATTCTCCAGTGGTCC AGATCTTTTTT; sh-ENG-2:

GCTCAGGATGACATGGACATCTT CAAGAGAGATGTCCATGTCATCC TGAGCTTTTTT; sh-ENG-3:

CGCCATGACCCTGGTACTAAATT CAAGAGATTTAGTACCAGGGTCA TGGCGTTTTTT; and negative control

(NC) shRNA,

TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAA TTCAAGAGATTACGTGACACGTTCG GAGAATTTTTT. The

ENG knockdown vector is GV248, with the element sequence:

hU6-MCS-Ubiquitin-EGFP-IRES-puromycin, and the restriction sites are EcoRⅠ and

AgeⅠ. The COL1A1 overexpression vector is GV492, with the element sequence:

Ubi-MCS-3FLAG-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin, and the restriction sites are BamHⅠ and

AgeⅠ. The plasmid carries a 3

The density of neovascularization in tumor tissue was evaluated in vivo using an ultrasound system (VINNO 6 LAB, VINNO Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) designed for small animals and coupled with a laser confocal microscope (LSM 900 & Axio Imager M2, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Following sedation with 0.3% pentobarbital sodium (50–60 mg/kg), mice were positioned on the imaging platform of the ultrasound system. Subsequently, a high-resolution 40 MHz probe designed specifically for small animal research was prepared. The imaging process was begun by activating the software and applying a conductive gel to the tumor region. The ultrasound probe was then finely adjusted for optimal positioning to capture detailed images of neovascularization density.

Frozen tissue sections were preserved in 75% ethanol and permeabilized with

0.1% Triton X-100. To reduce non-specific binding, sections were first blocked

with 1% goat serum. The following primary antibodies were applied: anti-EGFP

(1:50 dilution, ab184601, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-CD31 (1 µg/mL

dilution, ab9498, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (1:50 dilution, 14550-1-AP,

Proteintech, Rosemont, USA). After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies

conjugated to Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) or Tetramethylrhodamine

Isothiocyanate (TRITC) (1:200 dilution) were used for visualization. Nuclear

staining was performed using 5 µL of 4

The IHC protocol followed the instructions given by the manufacturer (ZSGB,

Beijing, China). Tissue slices were first subjected to dehydration at 56

°C for 30 minutes and subsequently rehydrated. To minimize non-specific

interactions, blocking was initially performed using serum, followed by the

addition of 100 µL of diluted (1:100) primary antibody solution. Samples

were incubated at 37 °C for one hour, then treated with a biotinylated

secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:1000) followed

by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. 3,3

HUVECs in the logarithmic growth phase were suspended in conditioned medium for accurate counting. A 200 µL cell suspension was added to each Transwell chamber well, with 200 µL of 10% FBS growth medium added to the culture plates beneath. After 12 or 48 h of incubation, the adherent cells were fixed, stained, and imaged to assess their morphology and distribution. Cells were counted in six randomly chosen fields per group using microscopy. This experiment was repeated in triplicate.

Corning Matrigel was carefully dispensed into each well of a 96-well plate (60 µL per well), then placed in an incubator for 30 min to ensure thorough solidification of the Matrigel. Following this, HUVECs were prepared in a specialized conditioned medium. Each well was inoculated with 10,000 HUVECs, with three replicates for each experimental set. After incubation for 6 h, the progression and morphology of cells was evaluated by microscopic examination. Cells were systematically photographed and quantitatively counted.

The RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) dataset for single-cell analysis (GSE149614), along

with 9 additional RNA-seq datasets focused on liver cancer, were retrieved

directly from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE149614). Concurrently, 33

tumor RNA-seq datasets accompanied by comprehensive clinicopathological

characteristics were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The processing

and analysis of these single-cell RNA-seq datasets was performed using the Seurat

R package (v5.1.0), which facilitated detailed cellular profiling. To understand the

dynamic progression and fate determination of tumor cells, the Monocle2 R package (v2.32.0) was employed to efficiently analyze pseudo-time trajectories. The criteria for

identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were set with the stringent

thresholds of

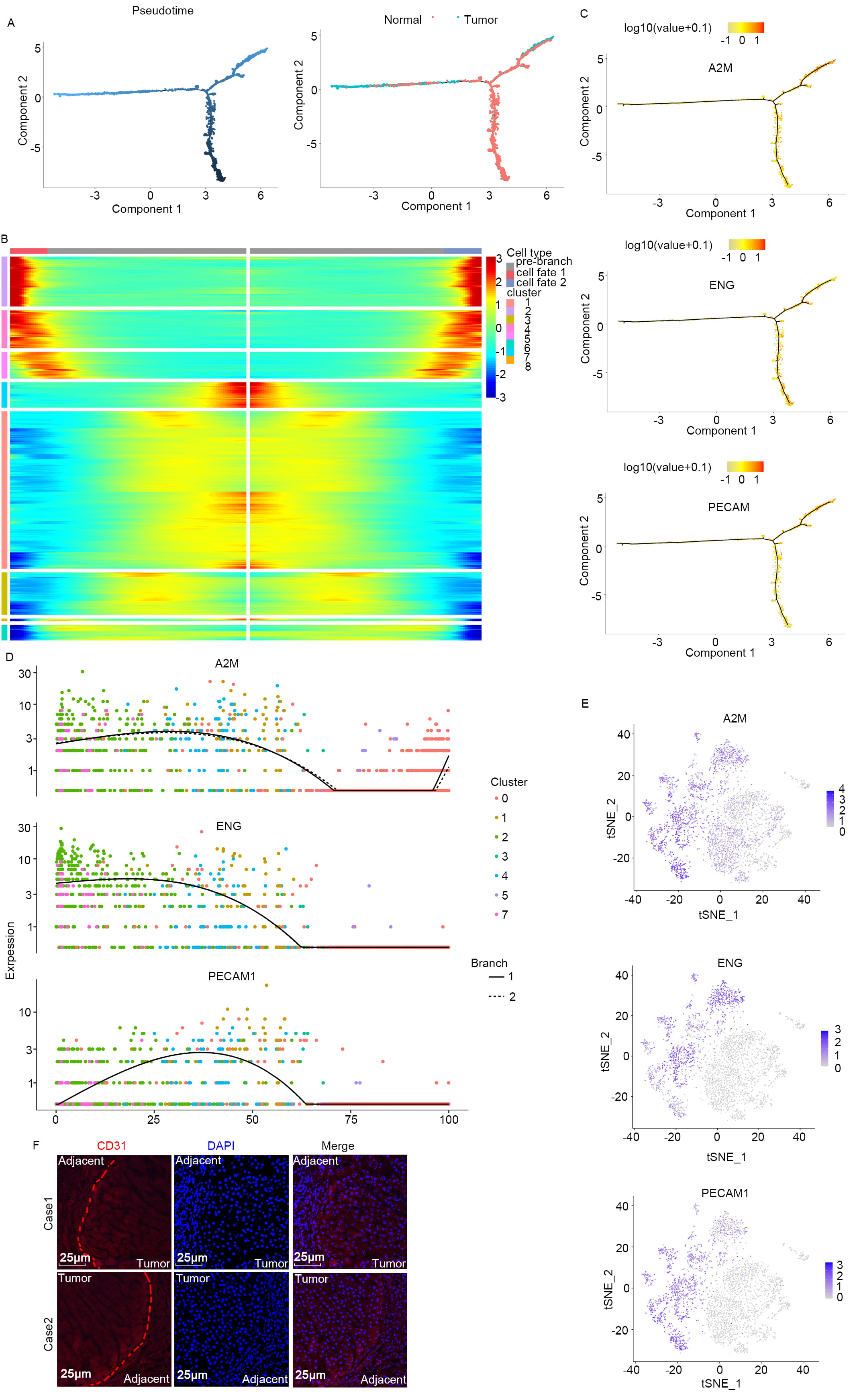

A correlation between specific types of liver cancer cells and the trajectory of disease progression is well documented [20]. However, the intricate details of how tumor cells evolve and progress in liver cancer have not been comprehensively elucidated. To address this gap in knowledge, we retrieved the single-cell dataset GSE149614 from the GEO database. Detailed cluster analysis of this dataset revealed the presence of 8 distinct tumor cell subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 1A,B), each identified by unique biomarkers (Supplementary Fig. 1C,D). These were present in both the primary liver cancer tissue and adjacent non-tumor tissue. A pseudo-time analysis was performed to unravel the evolutionary trajectories of each tumor cell subtype. This revealed that during migration from the central tumor mass to the adjacent normal tissue, the tumor cells underwent significant retro-differentiation at three major branch points (Fig. 1A). Retro-differentiation involved substantial changes in the expression profiles of specific markers in the tumor cell subpopulations (Fig. 1B). During this transformative process, a notable increase was observed in the expression of markers typically associated with vascular ECs, including ENG, Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M) and Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (PECAM1) (Fig. 1C–E). To further substantiate these observations, immunofluorescence staining was conducted on biopsy samples from liver cancer patients. This confirmed the elevated expression of CD31 (n = 6), a marker of vascular ECs, predominantly in the tumor cells located at the edges of the tumor mass (Fig. 1F). The findings suggest that as liver cancer cells migrate from the central tumor region to surrounding normal tissues, they transform into vascular endothelial-like phenotypes, indicating the presence of a complex mechanism of cancer progression and metastasis.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Retro-differentiation of tumor cells to vascular endothelial-like cells during the process of infiltrating para-carcinoma. (A) During infiltration from within the tumor to adjacent normal tissue, the tumor cellsretro-differentiate at three distinct branch points. (B) Heat map showing that specific markers of the subpopulation are reprogrammed during this retro-differentiation process. Markers in different subgroups exhibit different expression profiles as the cells undergo de-differentiation. From left to right represents the dynamic changes in gene expression levels from the starting point to the endpoint. (C–E) Markers of vascular endothelial cells (ECs) (Endoglin (ENG), Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M), Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (PECAM1)) increase during the retro-differentiation process. (C) Each dot represents a single cell, with the colors indicating different cell clusters. From left to right indicates the cell differentiation trajectory. (D) Colored dots indicate different tissue clusters. The vertical axis represents the expression level, with each point in the figure representing a single cell, and showing the overall expression level of the gene across these cells. (E) t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) plot showing gene expression data for the marker gene. (F) Pathological tissue at the cancer-peritumoral junction was collected and subjected to immunofluorescent staining, revealing a dense distribution of tissue cells at this junction. Scale bars, 25 μm. The vascular EC marker, CD31, was highly expressed in tumor cells at the tumor junction. The entire trajectory is shown, from malignant cells in tumor tissue to differentiated ECs in adjacent normal tissue. The red line represents the boundary between tumor tissue and adjacent tissue.

To investigate tumor cell transformation into ECs during invasion, Huh7 liver

cancer cells were genetically modified to express EGFP via stable infection with

an EGFP-shRNA lentivirus (Fig. 2A). A total of 5

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Transformation of liver cancer cells into neovascular ECs in a

nude mouse model of cancer. (A) The Huh7 cell line was stably infected with

exogenous EGFP gene. Scale bars, 25 µm. (B) The S-Sharp Prospect small animal ultrasound

imaging system was used to examine the distribution of blood vessels (box). (C)

After injecting 1% Evans blue into the tail vein, the vascular morphology of

tumor-bearing tissue was observed with a probe for small animals using in

vivo laser confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 20 µm. (D) Subcutaneous tumor-bearing tissues were

successfully generated in nude mice. (E,F) A representative image from confocal

microscopy. Case-1 and case-2 in (E) show that vascular ECs in tumor-bearing

tissues were derived from Huh7 tumor cells, especially ECs located in the

vascular cavity and which expressed both the EC marker CD31 and the tumor marker

enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Similarly, the two liver cancer cases

from patients shown in (F) also show that vascular ECs express both the liver

cancer marker Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and the EC marker CD31. 4

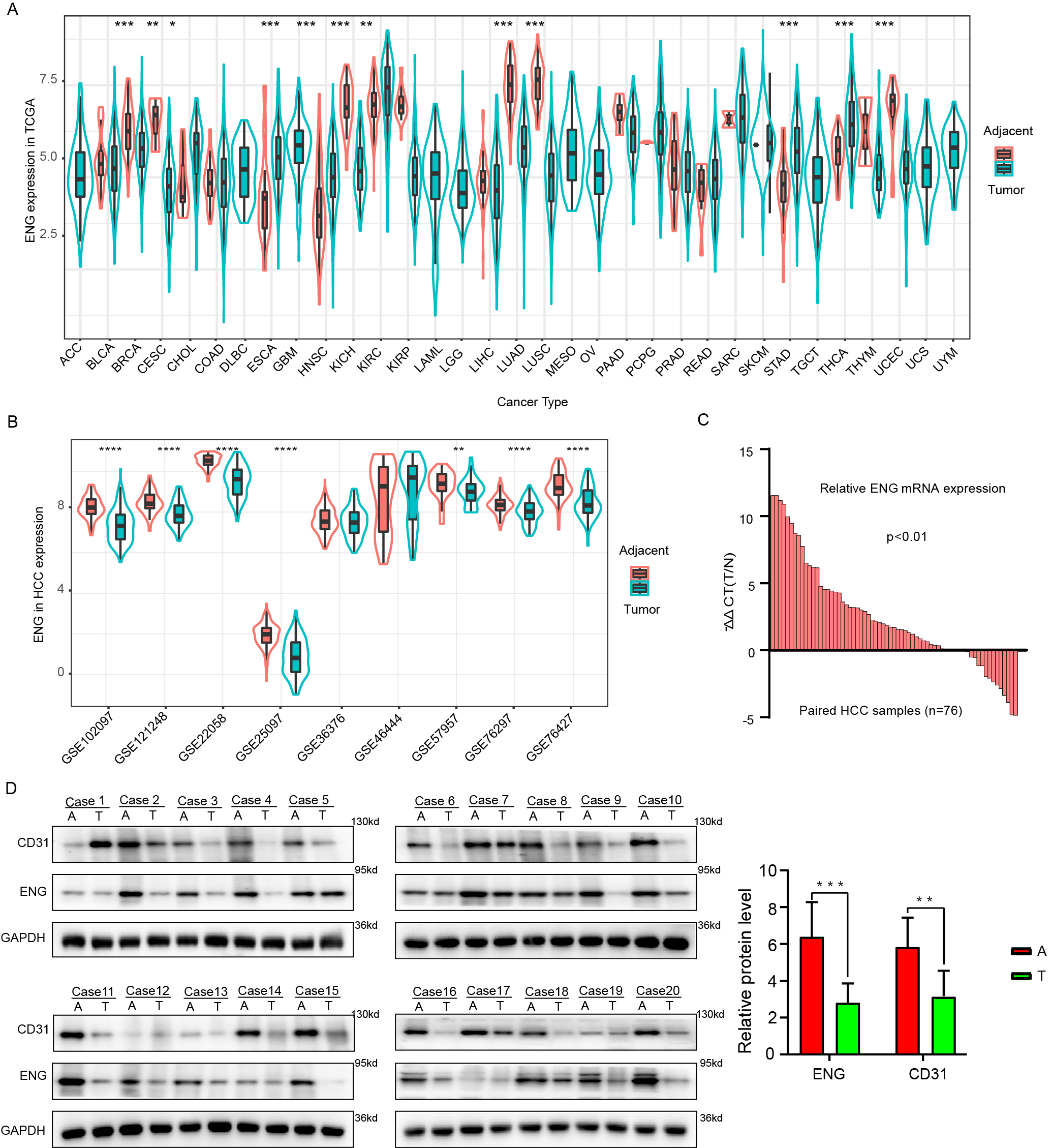

We next incorporated transcriptomic data from 33 distinct cancer types, supplemented with 9 datasets from the GEO. Analysis of these datasets revealed specific expression patterns for ENG, FLT1, A2M, and PECAM1. Of note, these genes were found to be significantly overexpressed in 12, 15, 15, and 17 of the 33 surveyed tumor types (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). In-depth analysis was carried out of the specific GEO datasets targeted at liver cancer, including GSE102097, GSE22058, GSE25097, GSE12128, GSE36376, GSE46444, GSE76297, GSE57957, and GSE76427. This revealed notable expression of ENG, FLT1, and A2M in 7, 4, and 9 datasets respectively, as shown in Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 2D,E. The ENG mRNA level in liver cancer samples was evaluated using qRT-PCR. This method confirmed that the ENG mRNA level was substantially upregulated in non-tumor tissue adjacent to the primary tumor, relative to the tumor tissue (Fig. 3C). To further validate these findings, Western blot analysis was performed on 20 pairs of human liver cancer samples, thereby allowing correlation of ENG protein and mRNA levels. A consistent pattern was found between ENG protein and mRNA expression, thus confirming the transcription data (Fig. 3D). This study found that vascular EC biomarkers are highly expressed in the tissue adjacent to liver tumors, suggesting their involvement in the surrounding pathological landscape of liver cancer.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The vascular EC biomarker ENG is highly expressed in adjacent

tissues. (A) Differential expression of ENG in different cancer types from the

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Green represents tumor tissue, while red

represents non-tumor tissue. (B) Differences in the expression of ENG between

tumor (green) and non-tumor (red) tissue in 9 different GSE databases. (C)

The mRNA level of ENG in 76 pairs of liver cancer tissue samples

(tumor and adjacent normal tissue) was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). (D) Western blot

analysis showing ENG protein expression in tumor tissue (T) and paired adjacent

tissue (A) from 20 liver cancer patients. Results are presented as mean

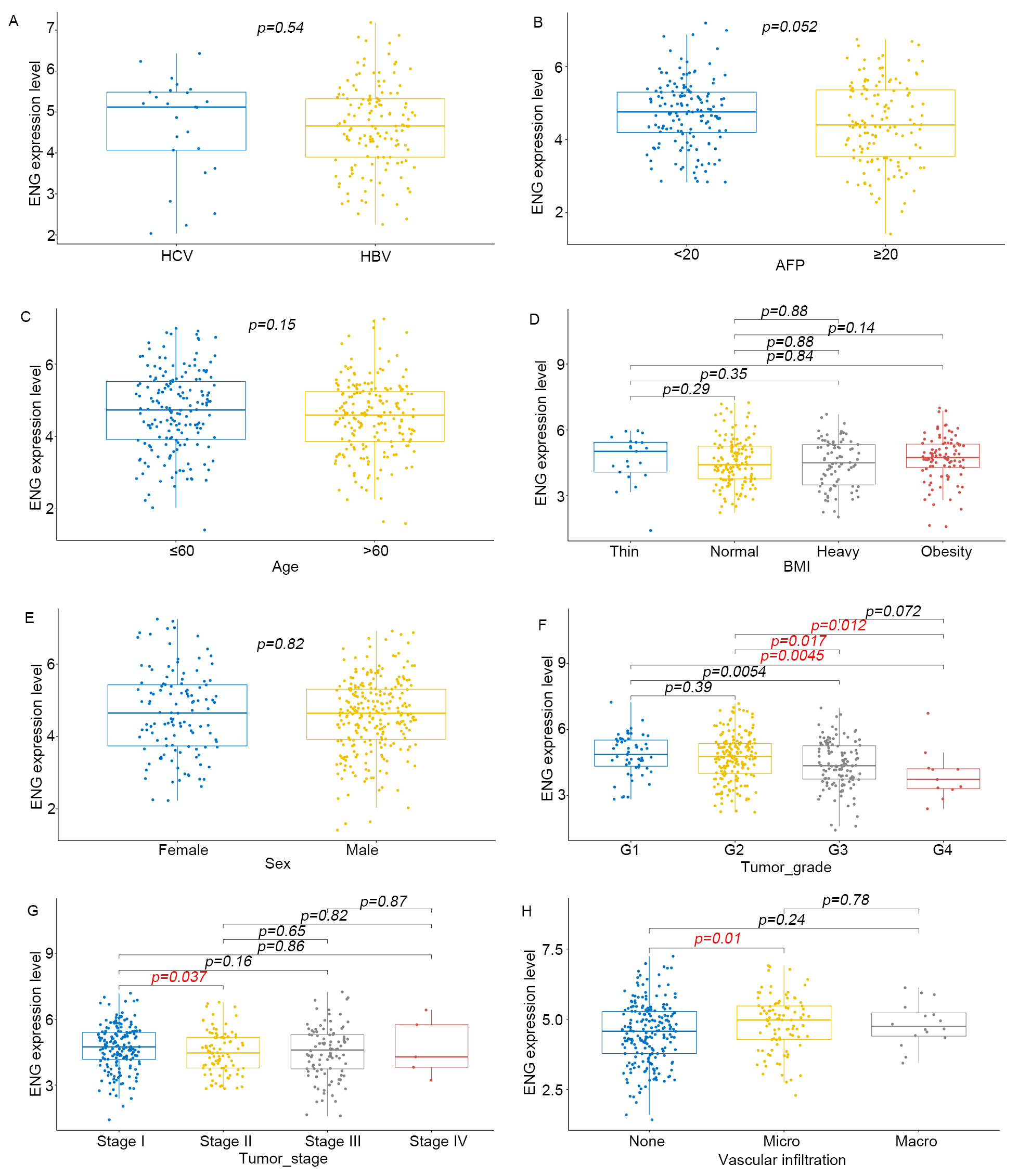

We next analyzed correlations between the expression of vascular EC markers and

various clinicopathological parameters, including microvascular invasion, tumor

stage and grade, age, gender, Body Mass Index (BMI), AFP levels, and Hepatitis B

Virus (HBV) infection status. This analysis found no significant correlations

between ENG expression and gender, age, BMI, or HBV status (Fig. 4). However,

strong positive correlations were found between ENG expression and the severity

of microvascular invasion and higher tumor grades. Additionally, significant

positive correlations were found between A2M gene expression and both

patient age (p = 0.028) and AFP level (Supplementary Fig. 3,

p = 0.036). Moreover, PECAM1 expression was significantly associated

with tumor grade (Supplementary Fig. 4, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The expression of ENG in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated

with clinical characteristics. (A–H) Correlation of ENG expression in liver

cancer with clinicopathological characteristics such as AFP, age, Body Mass Index

(BMI), gender, Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), microvascular infiltration, pathological

grade, and pathological stage of tumor specimens in the TCGA database. p

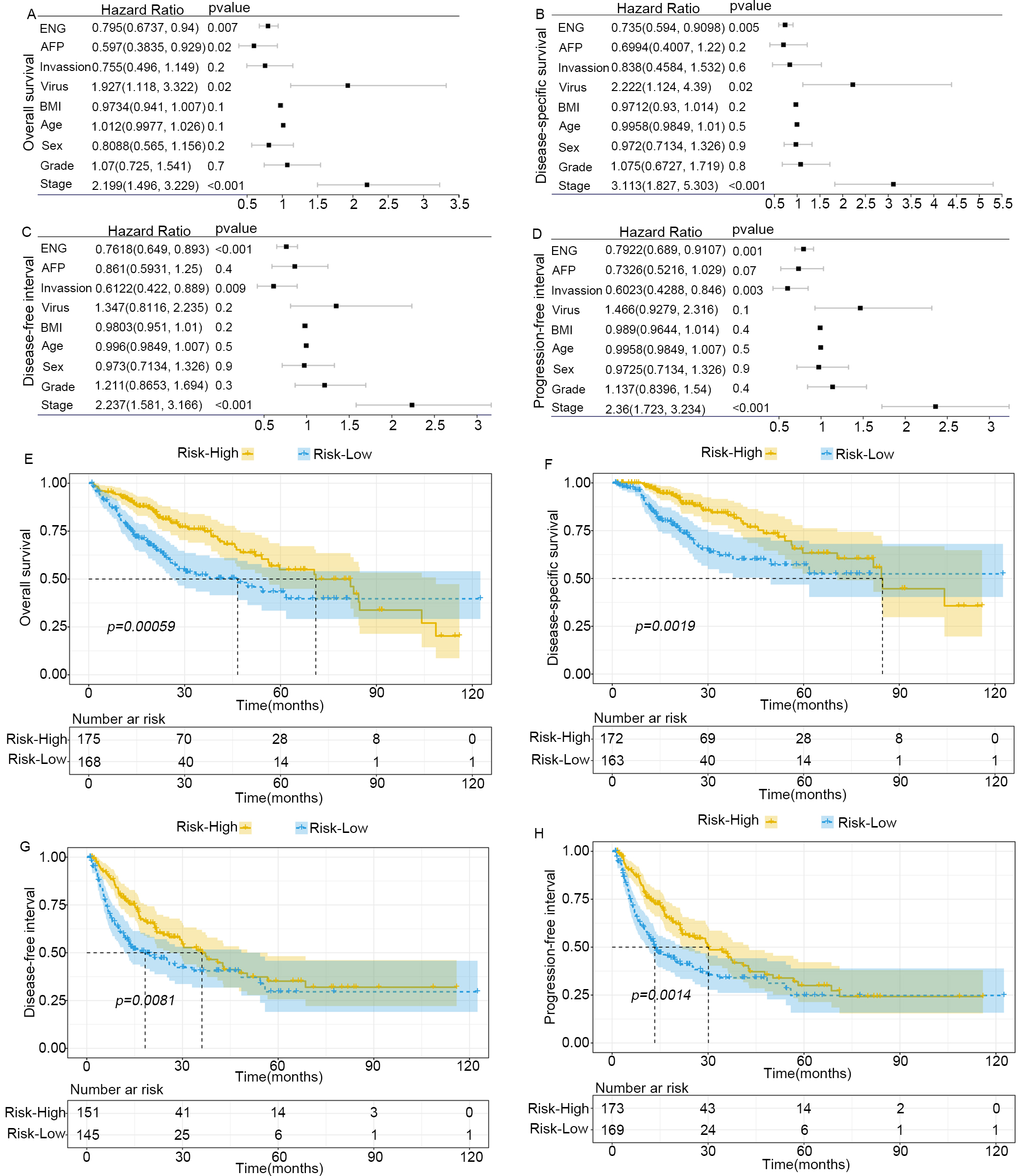

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Elevated expression of ENG in adjacent tissue promotes the

progression of liver cancer. (A–D) Forrest plot of stepwise Cox univariate and

multivariate proportional hazard regression models used to analyze the

association between ENG expression and the outcome of patients with liver cancer.

(A) overall survival (OS). (B) disease-specific survival (DSS). (C) disease-free

interval (DFI). (D) progression-free interval (PFI). AFP,

This investigation initially used the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) database to analyze the relationship between ENG and the well-established vascular marker CD34. Analysis confirmed a strong positive correlation between the expression of ENG and CD34, suggesting a potential interactive role in tumor vascularization (Fig. 6A). To further substantiate this finding, the microvessel density (MVD) was assessed in liver tumor samples from a cohort of 65 patients. IHC staining for CD34 was used to quantify the vascular structures. Samples with high ENG expression exhibited a significantly higher MVD compared to samples with low ENG levels (Fig. 6B–D). Lentiviral vectors were used to introduce ENG shRNA into the liver cancer cell lines Huh7 and HepG2, with an empty vector serving as a control. Following 72 h incubation, protein extraction and subsequent Western blot analysis revealed a marked decrease in ENG expression in cells treated with ENG shRNA compared to controls (n = 3) (Fig. 6E). Transwell migration and HUVEC tubule formation assays were conducted to assess the impact of ENG downregulation. A significant reduction in tubular structure formation (n = 3) (Fig. 6F) was observed following the suppression of ENG, as well as a significant decrease in migration (n = 3) (Fig. 6G). Together, these results suggest that ENG plays a role in the angiogenesis of liver cancer.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

ENG expression can promote microvessel formation in liver

cancer. (A) Analysis of the GEPIA database showed that ENG and CD34 expression

were positively correlated. (B) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed significantly

elevated expression of CD34 in tumor tissues with high expression of ENG. Scale

bars, 100 µm. (C,D) The MVD in the group with high ENG expression

was significantly higher than in the group with low ENG expression. (E) Western

blot assay showed that the protein level of ENG decreased significantly after

downregulating ENG. (F) The tubule formation assay with HUVECs revealed

significantly reduced ability for tubule formation after interference of ENG

expression. Scale bars, 100 µm. (G) Transwell migration assay

indicated that the migration ability of HUVECs cultured with conditioned medium

was significantly reduced following downregulation of ENG expression. Scale bars,

100 µm. Results are presented as mean

Initially, we conducted an enrichment analysis that focused on pathways involved in different cancer types. This analysis consistently indicated that angiogenesis is a prevalent pathway in almost all the cancer types examined (Fig. 7A,B). We next examined the direct relationship between ENG and angiogenesis. A strong positive correlation was found between ENG expression and angiogenic activity in tumors (Fig. 7C). Given the crucial role of COL1A1 in the development and progression of various cancer types [21, 22, 23], the study was expanded to examine interactions between ENG and COL1A1. Analysis of extensive datasets from TCGA, LIHC, Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx), and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle) revealed a strong positive correlation between the levels of ENG and COL1A1 expression (Fig. 7D–G). To empirically verify these correlations, Western blot assays were performed on cell lines that express low levels of ENG. This revealed that downregulation of ENG led to a marked decrease in COL1A1 expression in both Huh7 and HepG2 cells, indicating a potential regulatory relationship (n = 3) (Fig. 7H, Supplementary Fig. 10). Based on these insights, we hypothesized that ENG may regulate HUVEC migration and tubule formation by influencing COL1A1 expression. To test this hypothesis, the Huh7 and HepG2 cell lines, which typically show low ENG expression, were genetically modified to overexpress COL1A1. Following introduction of the COL1A1 overexpression plasmid and a 72 h incubation period, the results showed that overexpression of COL1A1 reversed the significant reduction in COL1A1 expression caused by ENG downregulation (Fig. 7I). Subsequently, Transwell migration and tubule formation assays were performed on the cells. The results showed significant restoration of migration ability and tubule formation in HUVECs, with a reversal of the deficits observed in the low ENG expression group (n = 3) (Fig. 7J–M).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

ENG promotes microvessel formation in liver cancer by

upregulating Collagen type I

Bioinformatics analysis indicated that ENG potentially regulates immune cell infiltration and the extracellular matrix (ECM) in liver cancer, suggesting it is significantly involved (Supplementary Fig. 6). Subsequent investigations using the ESTIMATE algorithm assessed the immune, stromal and estimated score, as well as overall tumor purity (Supplementary Table 4). These results showed that elevated levels of ENG expression were directly associated with higher immune, stromal and estimate scores, but inversely related to tumor purity (Supplementary Fig. 7A–D). The CIBERSORT algorithm was subsequently utilized to further characterize the immune cell composition in patients with varying levels of ENG expression (Supplementary Table 5). This profiling identified substantial infiltration of various immune cell types in patients with elevated ENG levels, including central memory CD4+ T cells, memory CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, and natural killer T cells (Fig. 8A,B). To substantiate these findings, Spearman’s correlation analysis was employed to examine correlations between ENG expression and the prevalence of various immune cell types. This revealed significant positive correlations with Type 1 T helper cells (r = 0.55), central memory CD4 T cells (r = 0.57), activated CD8 T cells (r = 0.2), Regulatory T cell (r = 0.51), T follicular helper cell (r = 0.44), Central memory CD8 T cell (r = 0.29), Gamma delta T cell (r = 0.21), Effector memeory CD8 T cell (r = 0.5), Effector memeory CD4 T cell (r = 0.31), CD56dim natural killer cell (r = 0.35), Natural killer T cell (r = 0.36), Natural killer cell (r = 0.65), Plasmacytoid dendritic cell (r = 0.48), Immature dendritic cell (r = 0.33), Activated dendritic cell (r = 0.23), and Macrophage (r = 0.55) (Fig. 8C–R). To further confirm the association of ENG with immune cell dynamics, IHC was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections of liver cancer. Patients with high ENG expression exhibited significantly increased levels of immune markers such as CD3, CD8 and CD45 compared to those with low ENG expression, thus substantiating the bioinformatic predictions (Supplementary Fig. 8). These findings validate the role of ENG in tumor angiogenesis and immune cell infiltration, as well as highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Correlation of ENG expression with specific tumor-infiltrating immune cell types. (A,B) The heatmap represents tumor-infiltrating immune cells, memory CD4 cells, memory CD8 cells, natural killer cells, and natural killer T cells in patients with high expression of ENG. (C–R) Spearman’s correlation analysis reveals the correlations between ENG expression and the level of infiltrating immune cells using quantitative data. MDSC, Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells.

Detailed analyses involving data extracted from the TCGA, LIHA, GTEx, and CCLE databases were performed to explore interactions between ENG and several crucial target genes for sorafenib involved in angiogenesis, including VEGFR, PDGFR, KIT Proto-Oncogene Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (KIT), and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA). Consistent and significant positive correlations were found between ENG expression and these key angiogenic indicators (Supplementary Fig. 9). A cohort of 32 liver cancer patients undergoing sorafenib treatment was used to further investigate the clinical significance of these findings, consisting of 19 responders and 13 non-responders. Analysis revealed that non-responders typically expressed lower levels of ENG (Fig. 9D). Patients with higher levels of ENG expression generally experienced a reduction in tumor diameter after receiving sorafenib treatment (Fig. 9E). Furthermore, the level of ENG expression was negatively correlated with changes in tumor diameter (Fig. 9F). Two cases showing changes in tumor diameter following treatment with sorafenib are presented in Fig. 9A, while four cases with different levels of ENG expression are presented in Fig. 9B,C. These findings indicate the efficacy of sorafenib for suppression of tumor growth may be influenced by the expression level of ENG.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

The expression level of ENG correlated with the efficacy of

sorafenib in patients with liver cancer. (A) Tumor diameter was recorded by a

radiologist based on the CT imaging with a black line. (B,C) Representative

images of IHC staining of ENG expression in tumors from liver cancer patients.

Scale bars, 100 µm, n = 32. (D) The expression level of ENG in liver

cancer patients who were responders or non-responders to sorafenib, n = 32. (E)

Changes in tumor diameter (mm) in liver cancer patients treated with sorafenib.

Increased tumor diameter is shown in red, and decreased tumor diameter in blue.

(F) Spearman’s rank correlation was performed to analyze the correlation between

changes in tumor diameter and the expression level of ENG. *p

Liver cancer is distinguished by a high recurrence rate, widespread metastasis, and low survival rates. These daunting challenges are exacerbated by the highly vascular nature of the liver and the complex dynamics within the TME [24]. Recent studies have established the essential role of angiogenesis in the progression of liver cancer, highlighting it as a key factor in this process. Despite widespread clinical application, anti-angiogenic therapies are often limited by the heterogeneity and complexity of tumor microvessels [25]. ECs that contribute to neovascularization in tumors have diverse origins, including from the bone marrow [26], cancer stem cells [11] and vascular channels [27]. This poses significant challenges for the effectiveness of such therapeutic strategies, and often results in variable treatment outcomes.

We analysed the single-cell dataset GSE149614, obtained from the GEO public database, to investigate whether liver cancer cells can undergo transdifferentiation into vascular ECs. This analysis revealed 8 distinct subgroups of liver cancer cells and also identified various subgroups within the paired adjacent non-tumor tissue, thus providing insight into the heterogeneity of tumor cells across liver cancer samples. Further examination revealed the expression of unique markers specific to each tumor cell subpopulation. Notably, tumor cells located in adjacent non-tumor tissue were found to express the typical vascular EC markers CD31 and ENG. A pseudo time-course analysis was then carried out to investigate the origin of tumor cell subgroups present in adjacent tissues. This revealed that liver cancer cells infiltrating into these areas might transdifferentiate into vascular ECs. Recent studies confirm the existence of tumor-derived endothelial cells (TDECs) in glioblastoma and myeloma [28, 29, 30]. Moreover, our experimental model involving mice transplanted with Huh7 cells showed that induced neovascular ECs exhibited simultaneous expression of the neovascular marker CD31, together with either EGFP (engineered into cultured Huh7 cells) or AFP, which is indicative of liver cancer (Fig. 2). In similar experimental models, ECs were reported to display human chromosomal features rather than those of mice, suggesting they contribute to angiogenesis within tumors [31]. Remarkably, the genesis of TDECs appears to be independent of traditional angiogenic factors such as VEGF and FGF [28]. This indicates a potential mechanism for tumor resistance to anti-VEGF therapies, and suggests that targeting of TDECs could enhance therapeutic efficacy. In conclusion, the extensive growth of new blood vessels in tissues adjacent to liver cancer may primarily involve TDECs, thereby facilitating tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

To investigate the significance of vascular EC markers for liver cancer progression, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation using both online databases and clinical specimens to assess the effectiveness of these markers for diagnosis and prognosis. Understanding the expression of EC surface markers is crucial for improving early detection, prognostication, and therapeutic targeting of liver cancer. Previous studies have established ENG, CD34, CD31, FLT1, and PECAM1 as markers associated with ECs [32, 33, 34]. However, unlike ENG, these other markers are less specific for the identification of neovascularization in liver cancer.

ENG expression is notably concentrated in the capillary ECs at the tumor margins, but is scarcely detectable in the vascular ECs of healthy tissue. This distinct expression pattern makes ENG a crucial marker for understanding EC proliferation in tumors, and enables the dynamic monitoring of EC proliferation in oncology [35, 36]. Recent research suggests that high levels of ENG expression are strongly linked to angiogenesis, ECM formation, and the activation of immune cells. Both Gene Ontology (GO) and GSEA analyses have confirmed the pivotal role of ENG in these biological processes. The present study found that ENG expression is substantially elevated in para-cancerous tissues compared to the tumor core, suggesting the TME can potentially enhance the progression of liver cancer. Moreover, patients exhibiting higher levels of ENG were found to have lower overall rates of survival. Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that ENG expression was an independent prognostic marker, with significant impacts on DFI, PFI, OS, and DSS. Previous reports in the literature indicate that high ENG expression in tissue adjacent to tumors is closely associated with an increased rate of recurrence after liver transplantation [37, 38]. This suggests that ENG is a predictive biomarker for post-transplant tumor recurrence, and may be a therapeutic target for reducing new blood vessel formation after surgery. In liver cancer, ENG is critical for angiogenesis, recurrence, and metastasis, although the specific mechanism by which it regulates tumor angiogenesis in this cancer type requires further study. Our initial investigations using the GEPIA database revealed a positive correlation between ENG and CD34 expression. Subsequent IHC analysis of 65 liver cancer samples found that elevated ENG expression was associated with significantly greater MVD.

We also studied the effect of ENG on the functional properties of vascular ECs.

Reducing the expression of ENG was found to significantly decrease cell migration

and the tube formation ability of HUVECs. These results strongly implicate ENG in

the vascularization process of liver cancer and suggest that it may be a

therapeutic target for inhibition of new blood vessel formation, thus providing a

novel strategy to control blood metastasis in liver cancer. In further studies,

we observed a positive correlation between ENG expression and angiogenesis in

liver cancer. Moreover, a positive association was found between ENG and COL1A1

expression, with the latter being essential for the ECM and for cell growth,

proliferation, and differentiation [39]. COL1A1 is overexpressed in most

malignant tumors and is crucial for metastasis involving cancer invasion [23].

Recent studies have emphasized the role of COL1A1 overexpression in angiogenesis,

particularly under the conditions of hypoxia, malnutrition, and ischemia that

promote EC migration and proliferation during vascular injury [40, 41]. Mutation

or abnormal expression of COL1A1 is associated with various vascular diseases.

For example, COL1A1 gene mutations have been associated with the development and

progression of familial aneurysms and atherosclerosis [42, 43]. In the context of

oncology, COL1A1 is involved in promoting tumor angiogenesis and invasion. It is

also quite important in the TME, which can affect tumor recurrence and metastasis

[44, 45]. Additionally, COL1A1 interacts with other related molecules such as

transforming growth factor

We hypothesized that ENG may regulate COL1A1 expression and hence vascular development in liver cancer. To investigate this, we conducted a series of in vitro experiments to analyze changes in COL1A1 expression in relation to ENG. Following downregulation of ENG expression, the expression of COL1A1 protein decreased significantly. Transducing HUVECs with LV-COL1A1 restored the reduced migration and tubule formation abilities of these cells caused by ENG downregulation. These findings confirm that ENG promotes microvascular development in liver cancer primarily by regulating COL1A1.

Numerous investigations have documented a strong link between the expression of

ENG and both the progression and outcome of liver and lung cancers [46]. ENG can

also regulate T-cell activity within the TME, thereby affecting the immune

surveillance mechanisms in tumors. In certain cancer types, high levels of ENG

are associated with reduced activity of CD8+ T-cells within the tumor. This

decreases the secretion of effector molecules needed by the immune system, such

as IFN-

Tumor-activated macrophages (TAMs) are prevalent immune cells within the TME and

significantly infiltrate tumor tissues. Our detailed analysis indicated that M1

macrophages enhance anti-tumor responses by promoting the secretion of cytokines

such as IL-1, Tumor Necrosis Factor

The present study found a strong correlation between the level of ENG expression and the presence of immune cells within the TME. These results suggest that tumors with extensive vascular networks exhibit enhanced recruitment of immune cells. However, an excess of tumor blood vessels typically leads to an immunosuppressive environment within the TME, thus limiting the effectiveness of immunotherapeutic interventions. By targeting and blocking pro-angiogenic factors, anti-angiogenic therapy can effectively remodel the tumor vasculature, resulting in enhanced blood perfusion, alleviation of hypoxia and acidosis, and mitigation of the immunosuppressive conditions that hinder immune cell functions. This offers a novel anti-tumor approach by integrating targeted therapy with immunotherapy. Such an approach could increase the quantity and functionality of immune cells in the tumor tissue, thus making it a highly promising treatment strategy. Angiogenesis inhibitors are critical in this strategy, as they specifically curb the amount of tumor angiogenesis. Sorafenib is a leading targeted therapy in liver cancer management that inhibits critical angiogenic pathways. It does this by targeting receptors and growth factors including VEGFR, PDGFR, KIT, and VEGFA that are essential for inhibiting tumor growth. The present investigation revealed strong associations between ENG expression and the mRNA levels of target genes for sorafenib. These associations were consistently observed across various platforms, including from the analysis of liver tissues and associated data within the TCGA, LIHC, CCLE, and GTEx databases. The tumor suppressive effect of sorafenib is known to occur through the modulation of its specific target genes. This prompted us to further investigate the potential of sorafenib as a targeted treatment for liver cancers characterized by high ENG expression. Our study involved 32 liver cancer patients treated with oral sorafenib, and the relationship between ENG expression and therapeutic efficacy of the drug was evaluated by IHC analysis of pathological tissues and assessment with computed tomography, respectively. The specific pathways through which ENG modulates the expression of genes targeted by sorafenib remain to be fully elucidated. However, our results indicate that elevated levels of ENG markedly increase the anti-tumor effects of sorafenib in liver cancer patients. Our findings highlight the role of ENG in enhancing the efficacy of sorafenib, as well as its potential as a biomarker for refining the use of anti-angiogenic therapy in the clinical setting, thereby transforming current treatment strategies for liver cancer.

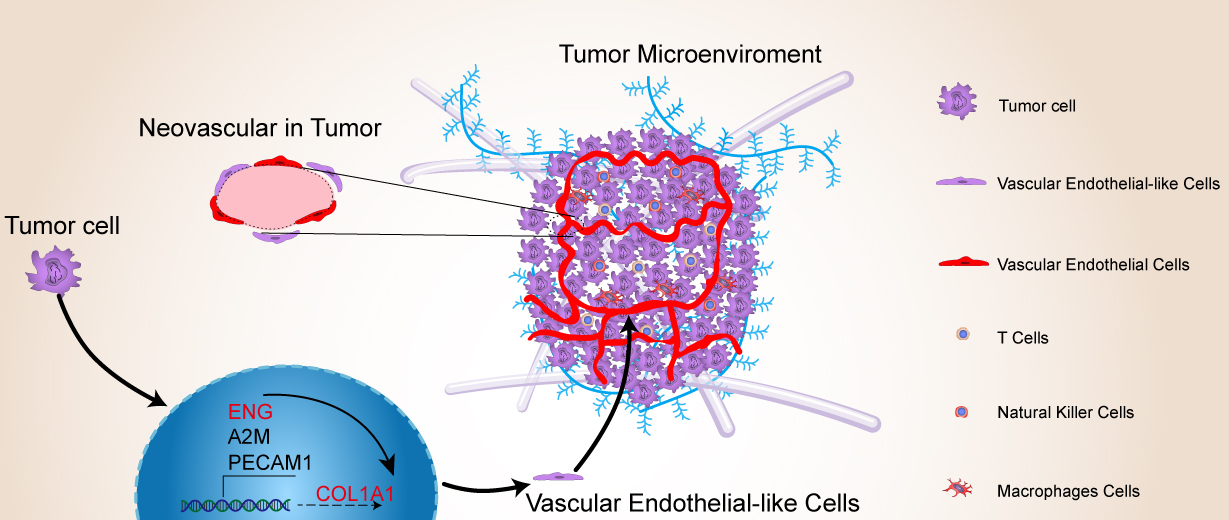

This study has made several critical findings regarding the role of ENG in liver cancer. Firstly, it established that the neovascular structures in liver cancer are primarily composed of ECs derived from the tumor itself. Secondly, a robust positive association was found between elevated ENG expression in the tissue surrounding liver tumors and the activation status of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, thus highlighting the potential for ENG to influence tumor immunity. Thirdly, our findings indicate that ENG plays a important role in promoting angiogenesis in liver cancer by increasing the expression of COL1A1. Fourthly, ENG enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of the therapeutic agent sorafenib in liver cancer. Lastly, our research underscores the potential utility of ENG as an integral biomarker in the clinical management of liver cancer. Fig. 10 illustrates this utility for ENG in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of liver cancer. The precise molecular mechanisms through which ENG contributes to new blood vessel formation and the recruitment of tumor-specific immune cells remains to be fully elucidated. However, the results of this study may contribute to the further development of targeted immunotherapies, as well as to improvements in the diagnosis and prognostication of liver cancer.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Working model showing the roles of ENG and COL1A1 in promoting angiogenesis in liver cancer through the process of tumor cell retro-differentiation into vascular endothelial-like cells. This pattern diagram was drawn using Adobe Illustrator 2023. (Adobe Inc.,San Jose, CA, USA)

ENG, Endoglin; ECs, endothelial cells; TDECs, tumor-derived endothelial cells; COL1A1, Collagen type I

All analyzed data supporting the study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. And the raw data will be made available from the corresponding author on request.

Conceptualization: SHS, CLZ and QGX ; methodology: SHS, CLZ, PJ and JXZ ; data curation: PJ and JXZ; formal analysis: YH; investigation and project administration: SHS and CLZ ; resources: YH ; software: PJ and JXZ ; supervision: QGX ; writing—original draft: SHS, CLZ, PJ and JXZ ; writing—review and editing: QGX. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (Ethic Approval Number: QYFYWZLL26589). Informed consent was obtained from participants or their legal representatives. All research processes are carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Qingdao University (Ethic Approval Number: 20220309BALB/c-nu3020221009059) in compliance with the national guidelines for the care and use of animals.

The authors acknowledge Hua Guo and Shuo Han for their technical assistance. The authors also thank Professor Dexi Chen (Beijing Institute of Hepatology, Beijing Youan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China) for sharing his small animal in vivo laser confocal microscope and ultrasound imaging system for these studies.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 82272973), Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan Youth Talent Project (grant number: 2021RC121) and Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan Project (grant number: 2023KY1055).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2909315.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.