1. Introduction

The most important components of the signaling system involved in the regulation

of the functional activity of the male and female reproductive system are

gonadotropins, such as luteinizing hormone (LH), chorionic gonadotropin (CG) and

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and their receptors. LH and CG, produced by

gonadotrophs of the adenohypophysis (LH, and sulphated CG), as well as the embryo

and placenta during the first trimester of pregnancy (hyperglycosylated and

classical CGs), are endogenous ligands of one G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR),

which is accordingly called the LH/CG receptor (LHCGR). They bind to a

high-affinity orthosteric site located in the ectodomain of this receptor. This

is not a common case for GPCRs, since most receptors in this superfamily are

activated by a single orthosteric agonist, but for a number of GPCRs, most

notably polypeptide hormone receptors, there are two or more orthosteric site

ligands, as has been demonstrated for the melanocortin receptors [1], orexin

receptors [2], apelin receptor [3], and N-formyl-peptide receptor [4].

In this case, the multiplicity of ligands can be due to various variants of

proteolysis or modification of the prohormonal molecule, a striking example of

which is the site-specific proteolysis of pro-opiomelanocortin, as well as

cross-interaction, which well illustrates the interaction of different orexin

isoforms with their receptors. The multiplicity of ligands is even more

characteristic of receptor tyrosine kinases, which is most clearly demonstrated

by the receptors of the insulin family peptides [5], the receptors of the

epidermal growth factor receptor family [6] and different isoforms of vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor [7].

LH and human CG (hCG) bind to LHCGR with high affinity, causing a wide range of

physiological responses, which is due to the functional interaction of activated

LHCGR with a large number of transducer proteins, through which the regulation of

many intracellular targets is carried out. Despite the fact that the regulatory

effects of LH and hCG are realized through the same receptor, and the

high-affinity orthosteric site responsible for their binding has a similar

structure and topology, the specificity of activation of intracellular cascades

by gonadotropins, and, accordingly, the cellular response caused by them can vary

significantly [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. This has a very definite biological significance, taking

into account the different physiological roles of LH and hCG in humans and some

other mammals. No less interesting is the fact that each of these hormones has a

large number of isoforms that differ in their specific activity, and this is

largely determined by the characteristics of the glycosylation of their

molecules, which significantly affects the binding of gonadotropin to LHCGR and

the bias of signal transduction [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Finally, the response to gonadotropin

may be regulated at the level of LHCGR through post-translational modifications

of the receptor, as well as through receptor complex formation, including

heterodi(oligo)merization with other receptors, most notably the FSH receptor

(FSHR) [14, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]. Glycosylation of gonadotropins and the processes of complex

formation and modification of LHCGR are the most important factors in the control

of LH/CG-mediated signal transduction in target cells, and they are based on

allosteric mechanisms that determine both the affinity of the gonadotropins for

LHCGR and the stability and pattern of activated conformations of LHCGR

responsible for selective signal transduction to intracellular effectors.

However, other, less studied factors in this aspect, such as the physiological

state of the organism, as well as the pathological processes, including

lipotoxicity, endoplasmic reticulum stress and overproduction of reactive oxygen

and nitrogen species, also have a significant impact on LH/CG-mediated signal

transduction, disrupting post-translational modification and “maturation” of

LHCGR and other signal proteins. In animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes

mellitus with hyperglycemia, insulin signaling dysfunctions, redox imbalance and

increased inflammatory processes, we and other authors have shown a significant

decrease in both LHCGR gene expression and the number of functionally

active LHCGRs on the surface of testicular and ovarian cells, which led to

weakened LH/CG signaling and impaired steroidogenesis [31, 32, 33, 34, 35].

All these factors, to one degree or another, influence the lipid composition of

membranes, the ionic and amino acid composition in the intra- and intercellular

environment, and the availability and activity of adapter and regulatory proteins

capable of forming complexes with LHCGR. It is known that cholesterol and

phospholipids, some simple ions (Na, Mg, Zn, Mn,

Cl, and others), amino acids and their derivatives (Tyr, Phy, Trp, Leu,

Ile, homocysteine, agmatine and others) can function as allosteric modulators of

GPCRs [36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. Their regulatory, modulating effect on the activity of LHCGR and

other components of LH/CG-stimulated cascades cannot be excluded, although strong

evidence for this has not yet been obtained. Autoantibodies to gonadotropins and

LHCGR, the formation of which has now been proven, can act as endogenous

allosteric regulators [43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. They are able to function as allosteric

regulators of LHCGR, which have their intrinsic activity, and to modulate the

effects of gonadotropins. It should be noted that with regard to other GPCRs,

there are numerous works on the allosteric effects of autoantibodies to GPCRs and

their key role in the development of autoimmune diseases [48, 49, 50, 51].

Thus, there are many mechanisms and targets of allosteric regulation of LHCGR

and the signaling pathways realized through it, which indicates the possibility

of fine-tuning the intensity and selectivity of LH/CG-induced signal

transduction. This tuning depends on the physiological status of the target cell,

the pattern of LH and CG glycoforms, the composition and ratio of

LHCGR-containing complexes, the activity of other signaling cascades modulating

LHCGR activity, and the presence of autoantibodies to gonadotropins and LHCGR.

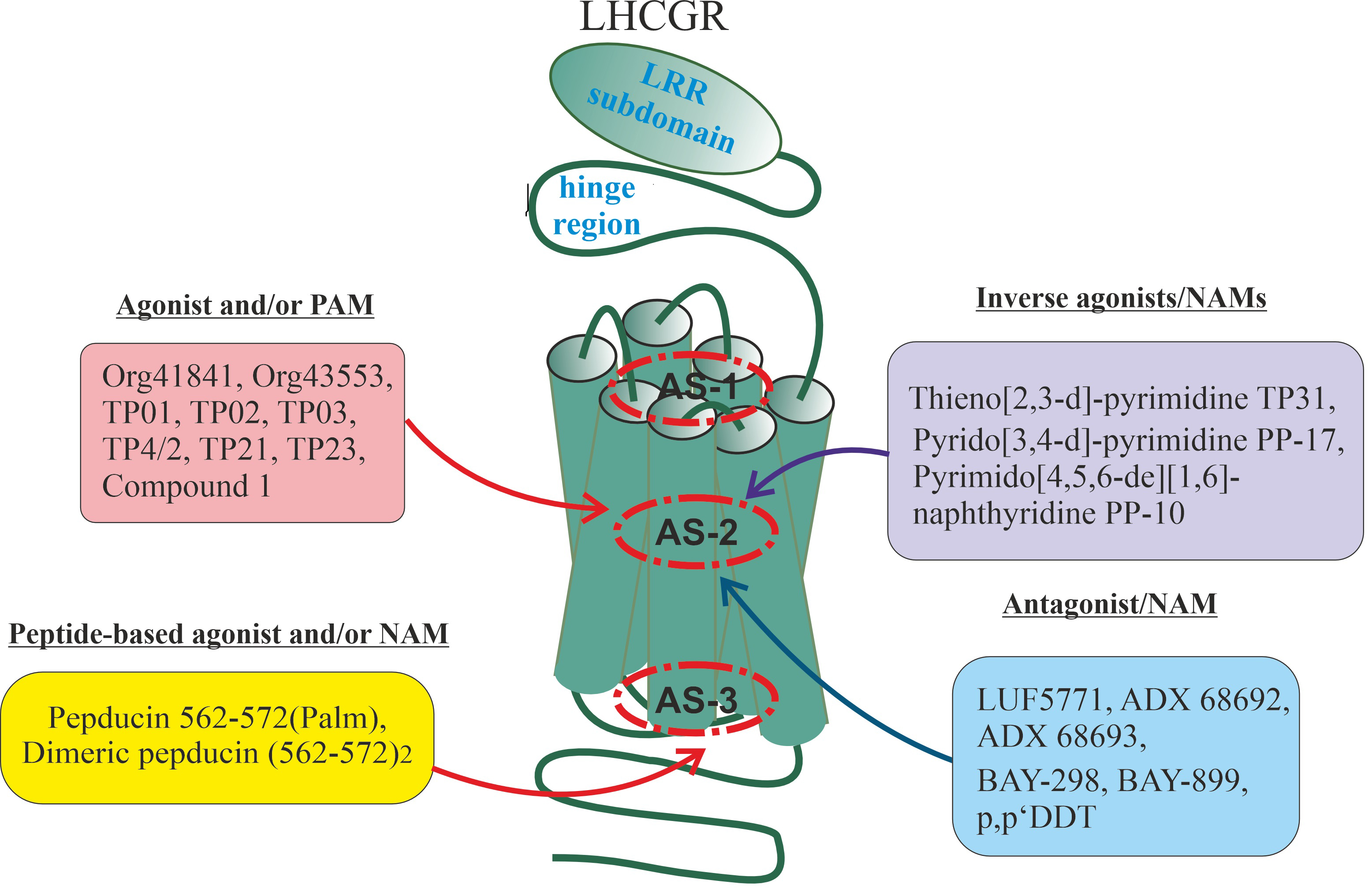

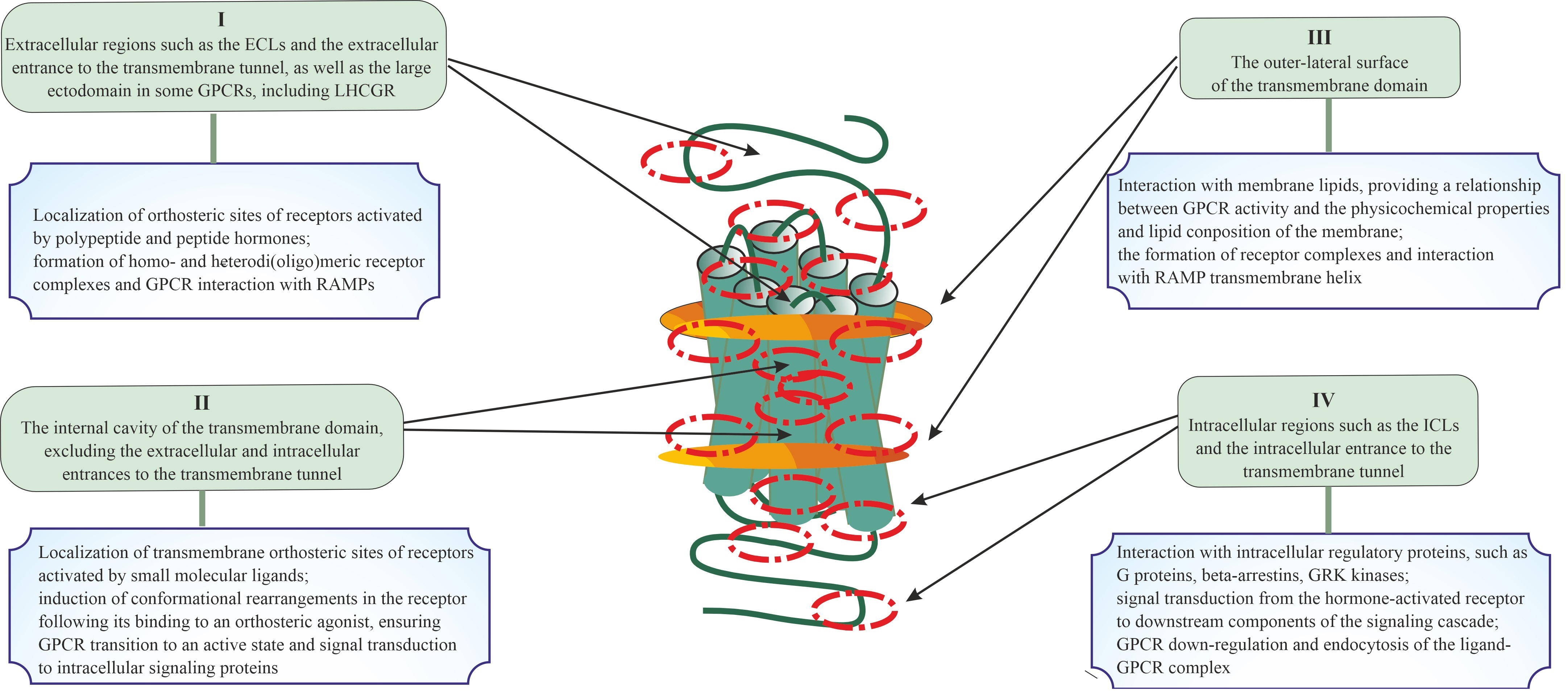

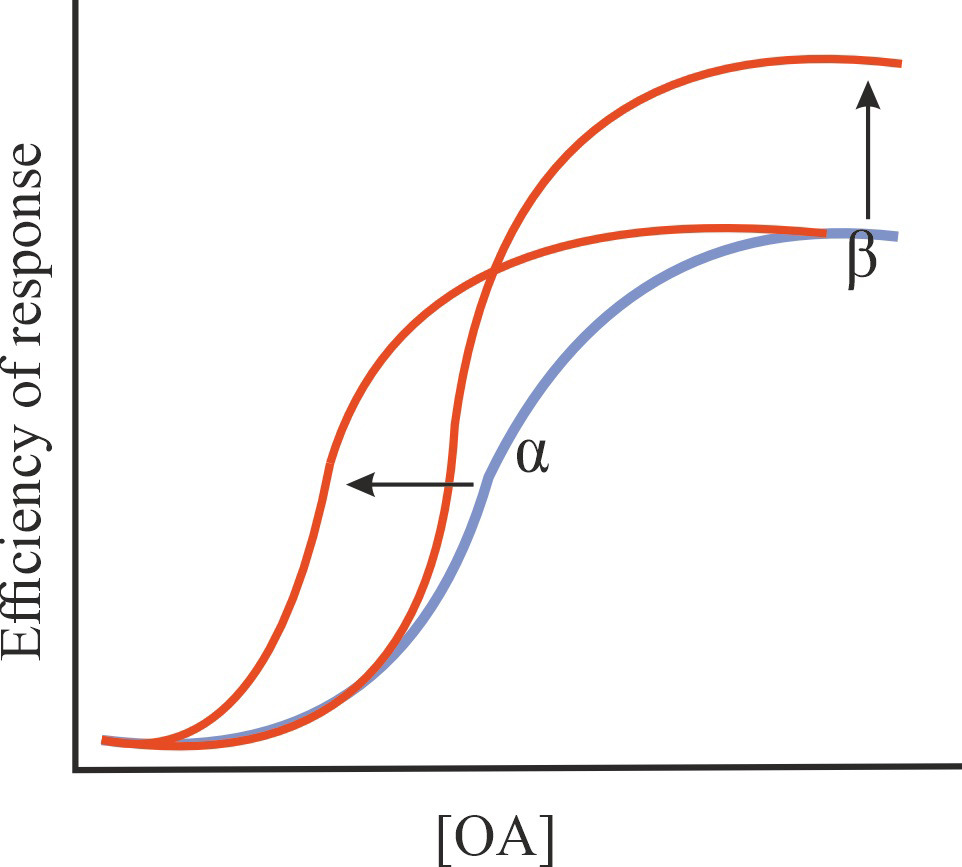

Such a variety of allosteric influences is predetermined by the existence of a

large number of allosteric sites in the LHCGR, as has been shown for other class

A GPCRs. These sites can be localized in various loci of the receptor molecule,

including in the extracellular loops (ECLs) and the external entrance to the

transmembrane tunnel, in the internal cavity of this tunnel, on the outer surface

of the transmembrane domain (TMD), which is in contact with the lipid bilayer of

the membrane, and in the intracellular loops (ICLs) and in the cytoplasmic

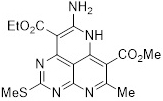

entrance to the transmembrane tunnel [42] (Fig. 1). Accordingly, it becomes

possible to develop site-directed allosteric ligands that will have a different

profile of pharmacological activity, being both modulators of the effects of

gonadotropin and having their intrinsic agonistic or antagonistic activity. As is

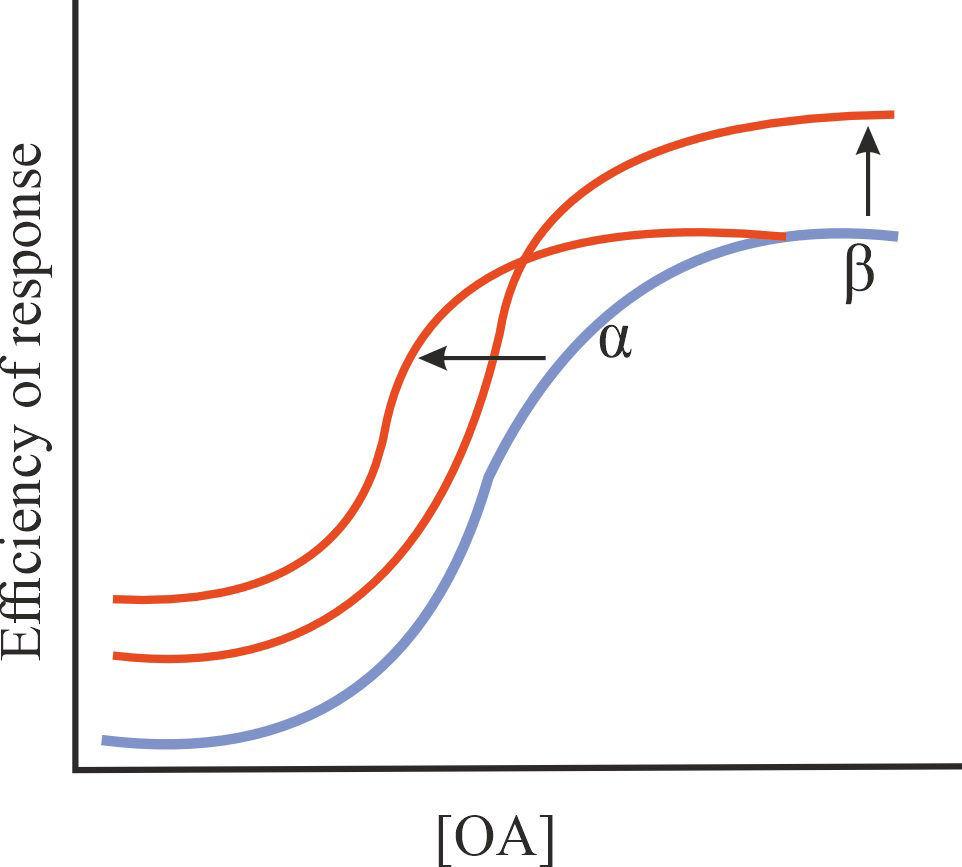

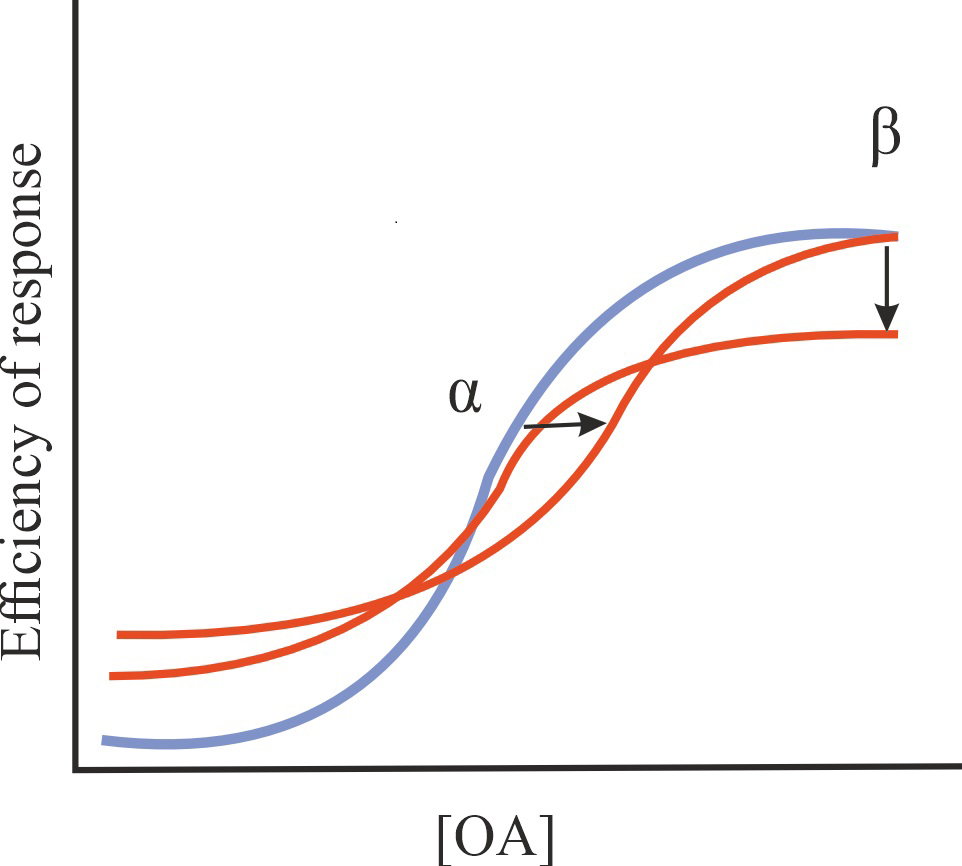

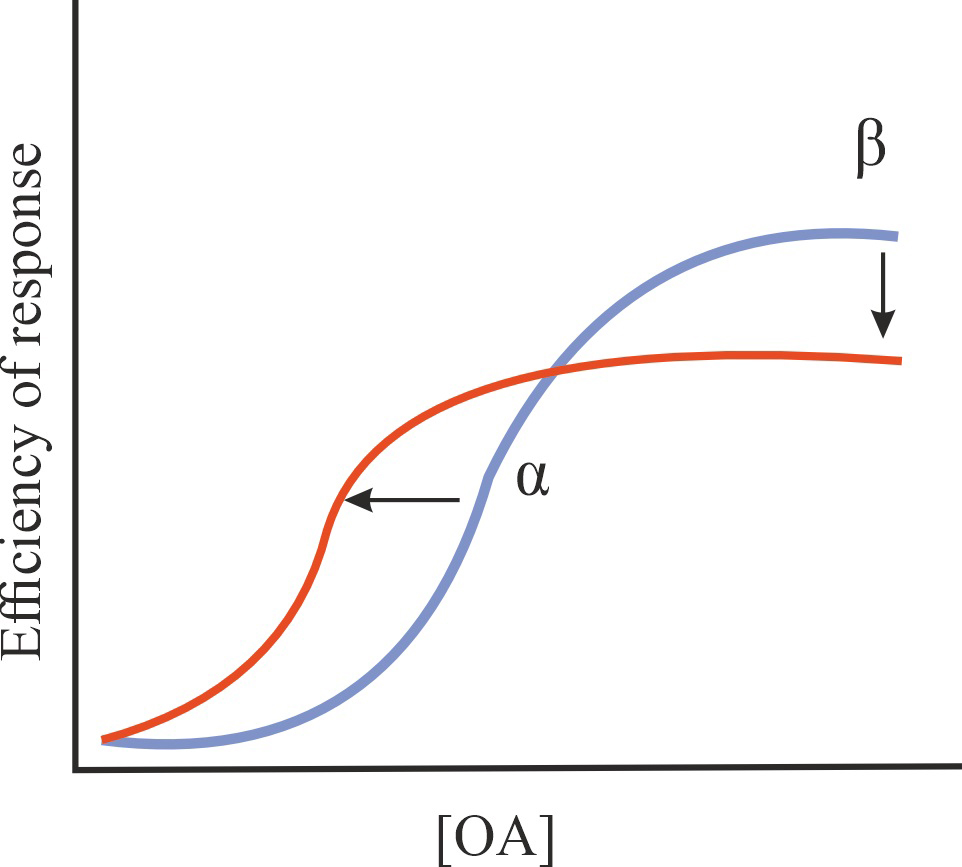

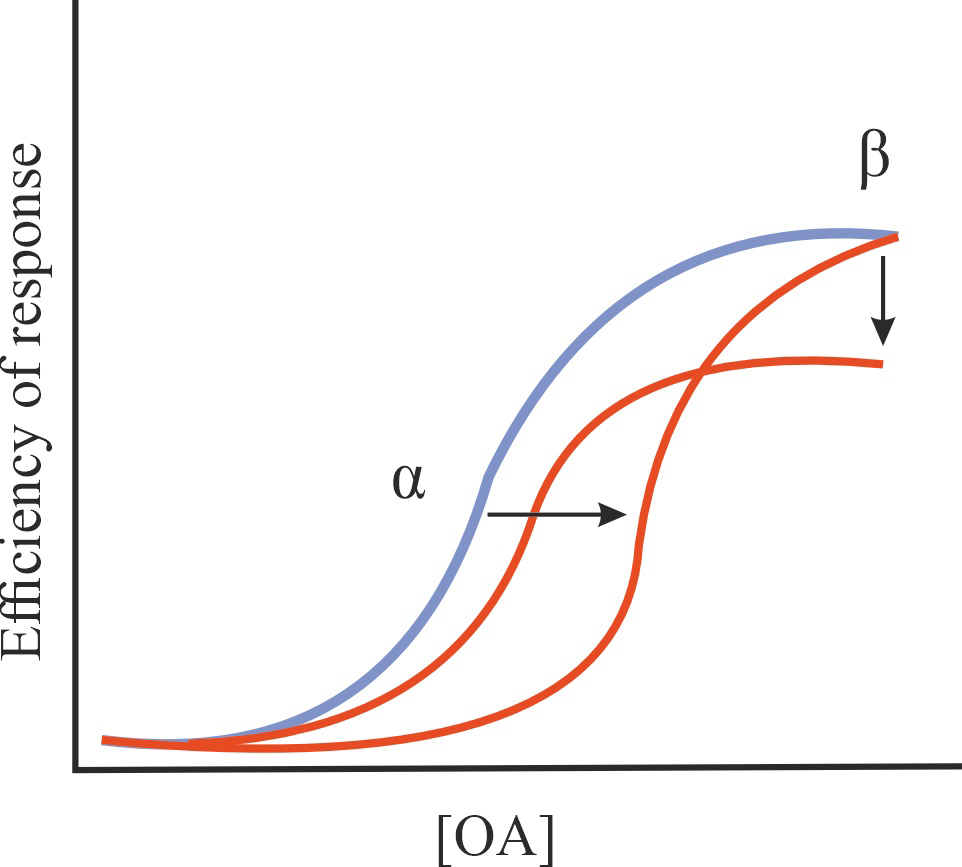

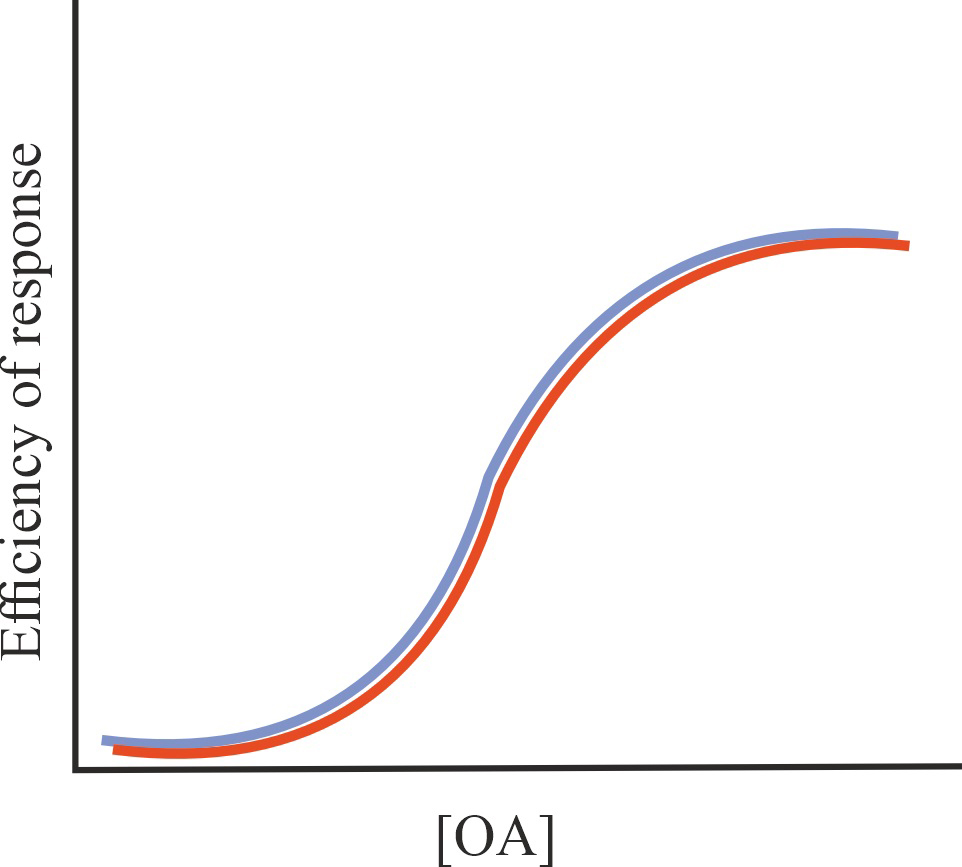

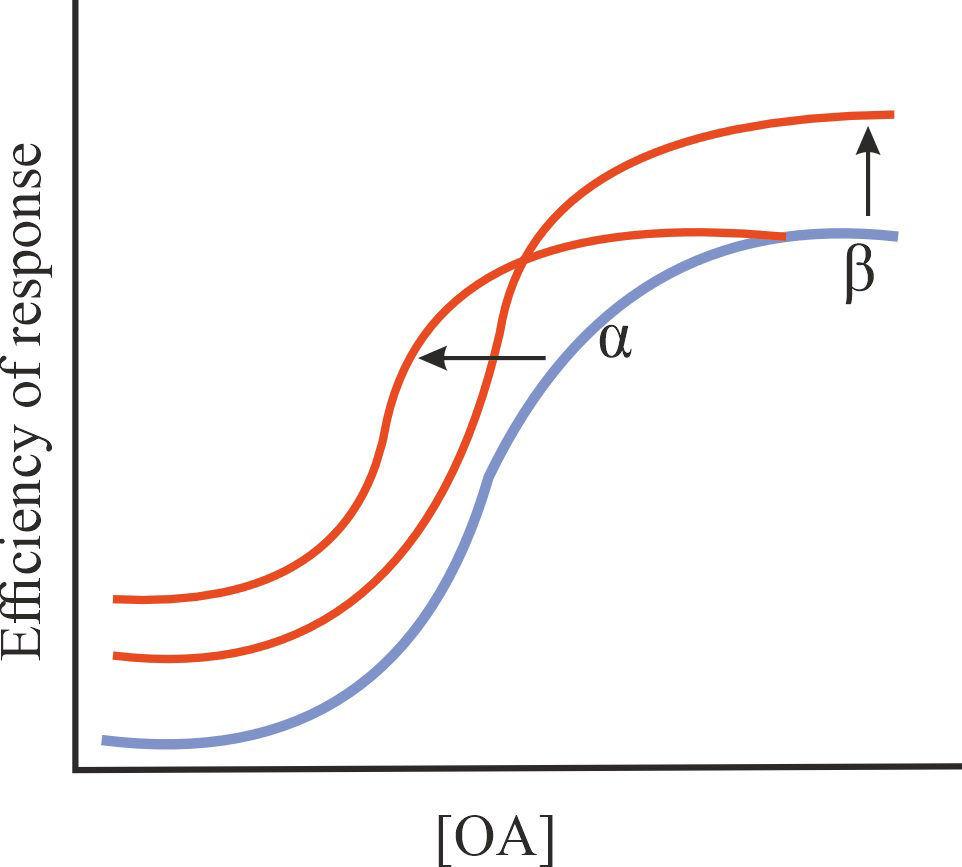

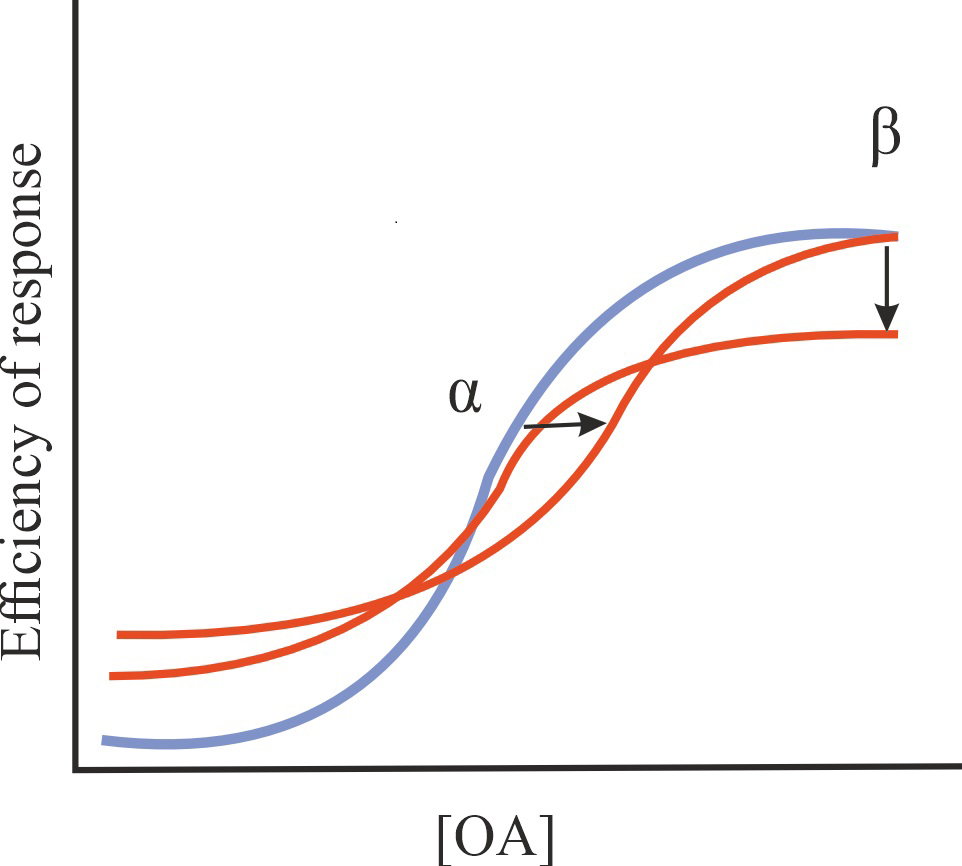

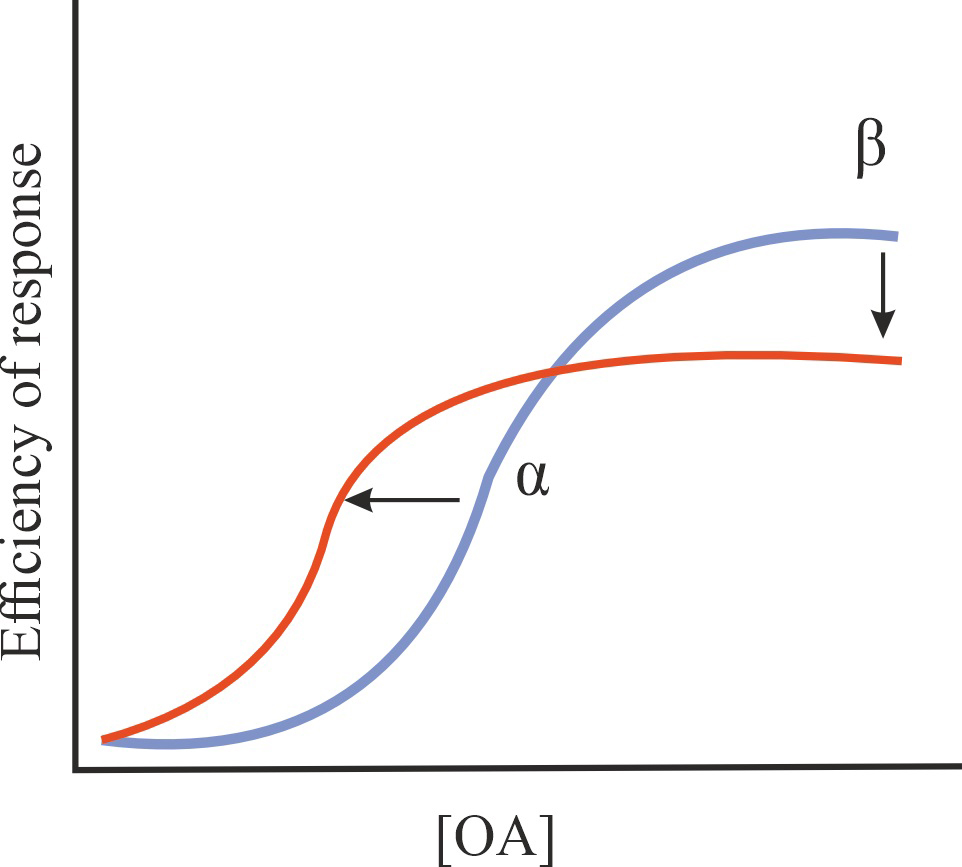

known, allosteric regulators can reduce (negative allosteric modulator, NAM) or

increase (positive allosteric modulator, PAM) the affinity and/or effectiveness

of an orthosteric agonist, do not directly affect these parameters, but modulate

other allosteric effects (silent allosteric modulator, SAM), exhibit its

intrinsic activity as a full agonist, inverse agonist or neutral antagonist in

the absence of an orthosteric agonist, as well as combine the activity of a full

agonist or antagonist with the activity of PAM (ago-PAM, PAM-antagonist) or NAM

(ago-NAM) [42, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56] (Table 1). Since allosteric sites functionally

interact not only with the orthosteric site, but also with each other, forming a

multidirectional network of such interactions, the activity profile of the

allosteric ligand can be very complex and cannot be described within the

framework of the proposed classification, which is to a certain extent true for

some low-molecular-weight (LMW) allosteric regulators of LHCGR.

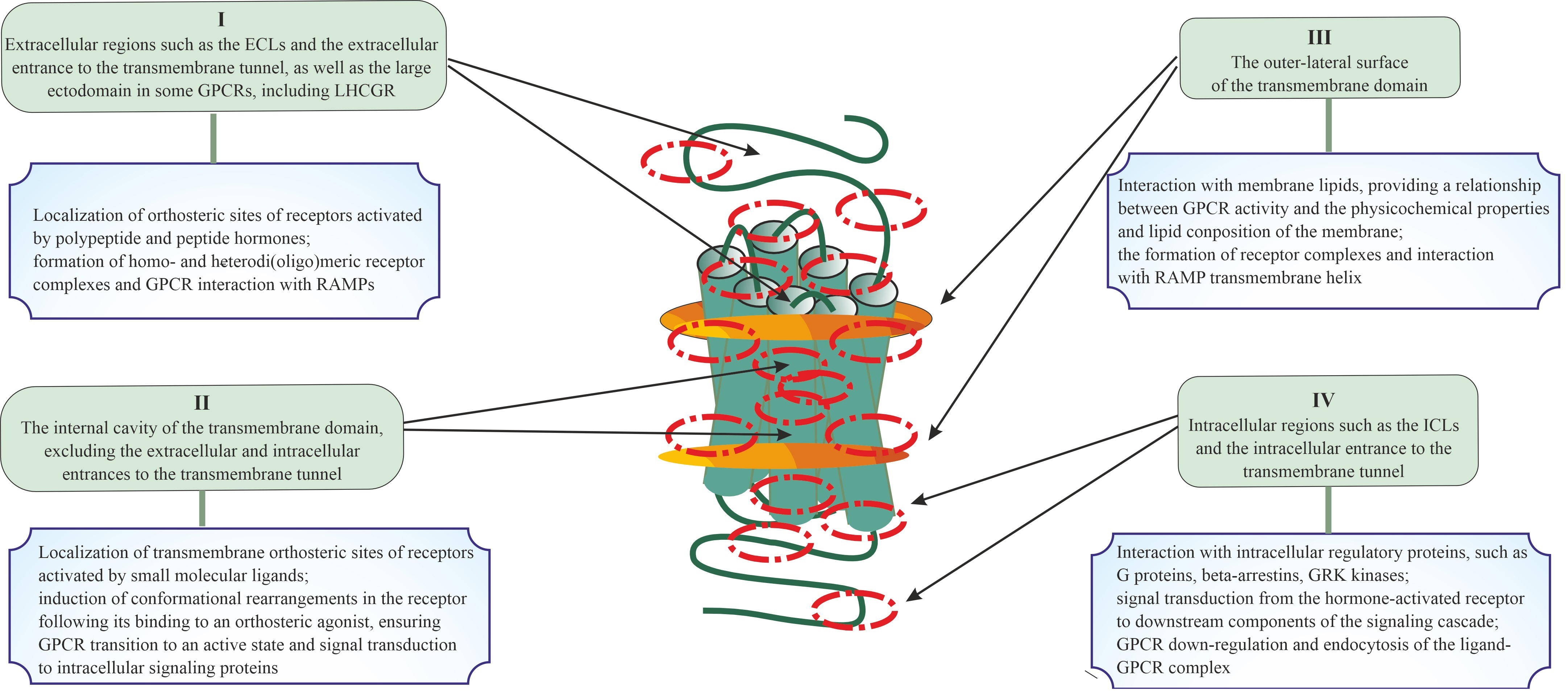

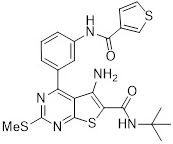

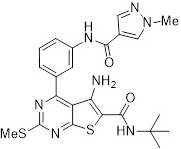

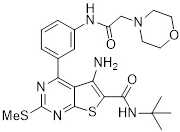

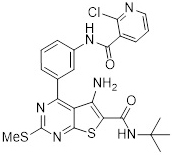

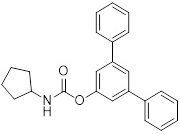

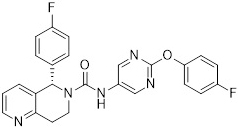

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Topologically distinct regions and domains of G protein-coupled

receptors (GPCRs) in which allosteric sites can be located, and the role of these

regions and domains in the signal transduction and the formation of di- and

oligomeric complexes. Four possible localizations for allosteric sites of GPCRs

are presented, including extracellular regions and/or domains (I), the

transmembrane tunnel of the TMD (II) and its side surfaces that contact plasma

membrane lipids (III), and cytoplasmic regions and/or domains (IV). The main

functions of these topologically different regions or domains of GPCR in signal

transduction and in the formation of various complexes (between GPCR protomers or

between the GPCR protomers and other signal and adapter proteins) are presented,

which indicates the possible role of allosteric sites located in them in the

implementation of these processes. At the same time, taking into account the

cross-talk between allosteric and orthosteric sites, as well as between

allosteric sites, this role can vary greatly and be much broader and more

diverse. ECLs, extracellular loops; LHCGR, luteinizing hormone/chorionic

gonadotropin receptor; RAMPs, receptor activity-modifying proteins; ICLs,

intracellular loops; GRK, G protein-coupled receptor kinase; TMD, transmembrane domain.

Table 1.

Pharmacological profile of ligands of G protein-coupled

receptors (GPCRs) allosteric sites, including allosteric modulators of the

effects of orthosteric agonist, allosteric regulators with their intrinsic

activity and with a combination of their intrinsic and modulating activity.

| Ligand type |

Effect on the basal and stimulated GPCR activity |

Characteristics of GPCR binding and/or activation |

| Positive, negative, silent and biased allosteric modulators (PAM, NAM, SAM, and BAM) |

| PAM |

Increase in the affinity of an orthosteric agonist (OA) for GPCR and/or in the effectiveness of its action without affecting the constitutive activity of GPCR |

1/1/=1 |

|

| NAM |

A decrease in the affinity of OA for GPCR and/or in the efficiency of its action without affecting the constitutive activity of GPCR |

1/1/=1 |

|

| SAM |

No effect on the affinity of OA for GPCR and (or) on the effectiveness of its action, possible change in some characteristics of the regulatory effect of allosteric agonists on GPCR activity (biased agonism, specificity of interaction with certain types of G proteins and -arrestins, formation of receptor complexes, availability of GPCR for allosteric regulators), no effect on the constitutive activity of GPCR |

=1/=1/=1 |

|

| BAM |

A change in the affinity of an OA for a GPCR and/or its efficiency of action, resulting in selective activation (positive allosteric modulator, PAM), inhibition (negative allosteric modulator, NAM) or modification (silent allosteric modulator, SAM) of a certain signaling cascade or a certain pattern of signaling cascades, which provides bias in OA action |

The values of , and vary depending on the specific cascade and the nature of the modulating allosteric action |

| Allosteric regulators with intrinsic activity, such as full (Full Ago) or inverse allosteric agonists (Inv Ago) and neutral allosteric antagonists (Ant) |

| Full Ago |

Stimulation of GPCRs in the absence of OA or other allosteric agonist, no effect on OA’s affinity for GPCRs or its effectiveness |

=1/=1/1 |

| Characterized by preferential activation of a certain signaling cascade (biased agonism), and more moderate stimulation of GPCR compared to OA |

| Inv Ago |

Reduction in constitutive GPCR activity in the absence of OA, as well as inhibition of OA- or allosteric agonist-stimulated GPCR activities |

=1/=1/1 |

| Characterized by preferential suppression of a specific OA-stimulated signaling cascade, as well as a selective influence on the pattern of active states of constitutively active GPCR; more moderate inhibition of constitutive and OA-stimulated GPCR activity as compared to orthosteric site inverse agonists |

| Ant |

Inhibition of OA- or allosteric agonist-stimulated GPCR activities without affecting constitutive GPCR activity |

=1/=1/1 |

| Characterized by a moderately pronounced inhibitory effect on OA-stimulated signaling cascades, which does not lead to their blockade, typical of orthosteric site antagonists |

| Allosteric regulators with combined modulating and agonistic activity (Ago-PAM – full allosteric agonist-PAM; Ago-NAM – full allosteric agonist-NAM; Ant/PAM – neutral allosteric antagonist/PAM) |

| Ago-PAM |

Increase in the affinity of OA for GPCR and/or in the efficiency of its action, stimulation of basal GPCR activity in the absence of OA, possibly potentiation of the effect of OA on GPCR activity |

1/1/1 |

|

| Ago-NAM |

Reduction in the affinity of OA for GPCRs and/or in the efficiency of its action, stimulation of basal GPCR activity in the absence of OA |

1/1/1 |

|

| Ant/PAM |

A decrease in the effectiveness of OA on GPCRs (antagonistic effect), but an increase in the affinity of OA for GPCRs (PAM effect) |

1/1/=1 |

|

Note: – the factor of binding cooperativity between the OA

and allosteric modulator; – the operational factor of cooperativity

for quantitative evaluation of the effects of allosteric modulator on operational

efficacy of OA (receptor activation); – operational efficacy for the

complex of GPCR with allosteric ligand. The values of binding cooperativity

() and operational cooperativity () greater than 1 denote

positive cooperativity, and the corresponding values below 1 denote negative

cooperativity. The value 1 for operational efficacy () is normalized

since the absolute value of can vary widely depending on the basic

design parameters used. For BAM and other cases of biased allosteric regulation,

different variants of the values of , and are

possible, since in this case it is necessary to differentiate the factors being

assessed for each specific signaling cascade regulated by OA or allosteric

regulator. PAM, positive allosteric modulator; NAM, negative allosteric modulator; SAM, silent allosteric modulator.

In addition, given the multiplicity of signaling cascades activated by

orthosteric agonists through GPCRs, allosteric modulators can selectively enhance

or, conversely, attenuate only a certain signaling cascade, thereby demonstrating

biased allosteric modulator (BAM) activity [54, 56, 57]. Such modulators are

important for ensuring selectivity of action and achieving target physiological

effects when using an orthosteric agonist that has low selectivity for

intracellular signaling. Allosteric regulators with their intrinsic activity,

full or inverse agonists, can also specifically regulate only a certain signaling

cascade, functioning as biased allosteric full or inverse agonists (Table 1).

This review is devoted to the analysis and discussion of the similarities and

differences in the regulatory effects of LH and various forms of hCG on the

activity of LHCGR and its signaling pathways, the role of glycosylation of LH and

CG and LHCGR complex formation in signal transduction, including its

heterodimerization with FSHR, as well as the possible contribution of

autoantibodies against gonadotropins and LHCGR in the control of LHCGR activity

and in the etiology and pathogenesis of reproductive dysfunctions. Along with

this, the review examines modern advances in the development of allosteric

regulators of LHCGR, including full and inverse LMW agonists and allosteric

modulators capable of interacting with the transmembrane allosteric site of LHCG.

The regulators with agonistic activity are of significant interest for the

correction of hypogonadotropic conditions and in the assisted reproductive

technologies (ARTs), while regulators with antagonistic activity may be in demand

in the treatment of hormone-dependent tumors and in contraception. The discussion

of the issues presented above is preceded by a brief description of the

structural and functional organization of gonadotropins and their receptors, the

molecular basis of their interaction, as well as the LHCGR signaling realized

through G proteins and -arrestins.

2. Structure of Luteinizing Hormone and Chorionic Gonadotropins

The LH is a -heterodimer with a molecular weight of about 30

kDa. LH secretion is carried out by gonadotrophs, specialized cells of the

adenohypophysis, and is controlled by the hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing

hormone (GnRH) [58, 59, 60]. Along with GnRH, the synthesis and secretion of LH are

regulated by polypeptide factors such as kisspeptin, melanocortin peptides,

gonadotropin-inhibiting hormone, leptin, adiponectin, activins and inhibins, as

well as steroid hormones, corticosteroids and, by a negative feedback mechanism,

sex steroid hormones, primarily estrogens, and some growth factors and cytokines

[61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69]. These factors can act either at the level of control of GnRH release,

directly or indirectly affecting the activity of GnRH-expressing neurons, or

directly influence the synthesis and secretion of LH by pituitary gonadotrophs.

Along with this, some of these regulators can influence both the secretion of

GnRH and the production of LH, as shown, for example, for leptin [70, 71] and

gonadotropin-inhibiting hormone [72].

Among the isoforms of human CG (hCG), the isoform of hCG expressed in the

pituitary gland, the so-called sulphated hCG [73], and the classical hCG, which

has an extrapituitary origin, are known. Classical hCG is synthesized and

secreted by the embryo and placenta during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Sulphated hCG is produced by the gonadotrophs of both men and non-pregnant women,

and despite its small quantities, it is significantly more active than LH, and

thus makes a significant contribution to the total LH-like activity of the common

pool of gonadotropins [73]. A hyperglycosylated form of the hormone has also been

discovered, which is expressed at the early stages of embryo development, mainly

at the cytotrophoblast stage and significantly differs in functional properties

from LH and other forms of hCG [74, 75].

The -subunit is encoded by a single gene and is common to all

gonadotropins. It is a polypeptide with a length of 116–120 amino acid residues

(AARs) and is characterized by a high degree of homology of the primary

structure. Thus, when comparing the human -subunit with those of

monkeys, up to 98% identity of the amino acid sequence was shown, when comparing

with the -subunits of rat, mouse, bovine, pig, dog, cat and rabbit,

75–76% identity was found, and when comparing with orthologues of birds,

amphibians, reptiles, and fish only 70–73% identity was shown.

-Subunits vary greatly in primary structure and determine the type of

gonadotropin. When comparing the -subunits of human LH, hCG and FSH,

only 33% of identical AARs were identified. At the same time, cysteine residues,

which determine the 3D structure of -subunits and are responsible for

the formation of functionally active -heterodimer complexes,

are highly conserved. The degree of identity of the sequences 45–153

-LH and 29–139 human -hCG is significantly higher and amounts

to 83%, which indicates their structural and functional similarity and

determines the ability of these hormones to specifically bind to the same

receptor. The homology of the -subunits of LH or hCG varies among

different animal species, but on average is quite high [18, 76]. Thus, when

comparing human and monkey -LH, the identity of the primary structure

varies only from 95 to 99%, and when comparing human -LH with rat,

mouse, rabbit and cat -LH it decreases to 72–75%. Moreover, among

various species of primates, the homology of -LH and -CG is

noticeably higher than when compared with -LH of other animals, which

indicates a relatively late divergence of -LH and -CG in the

evolution of higher vertebrates.

In the 1990s, based on X-ray diffraction data, the 3D structure of the

heterodimeric hCG was first identified [77, 78], and subsequently the 3D

structure of the LH was established [79, 80]. The main structural characteristic

of the - and -subunits that make up gonadotropins is the

presence of intramolecular disulfide bonds in them. They connect segments of

- and -subunits that are distant from each other, causing them

to cross each other and form a rigid knot structure called a cystine knot.

Cystine knots are localized in the central part of the - and

-subunits and stabilize three loops (L1, L2, and L3) extending from the

center of the dimer. Two of them (L1 and L3) are rigid in structure and have the

shape of a hairpin (the so-called hairpin structures), while the L2 loop is more

flexible and is located on the opposite side from the center of the molecule [76, 79]. In a heterodimer, the - and -subunits are located

symmetrically with respect to each other, have an elongated shape and are

characterized by a large ratio of surface area to volume of the molecule. The

polypeptide, which corresponds to the C-terminal region of the

-subunit and extends beyond its central part, held together by cystine

knots, functions as a safety belt by wrapping around the antiparallel

-helices that form the L2 loop of the -subunit. The 3D

structure of the seat belt is stabilized by an intramolecular disulfide bond, the

formation of which involves cysteine residues, one of which is localized in the

L1-loop of the -subunit, and the other is closer to its

C-terminus (Cys and Cys in -hCG). It should be

noted that the segment that forms the central part of the seat belt of the

-subunit (the region 93–100 in -hCG) determines the

specificity of the interaction of gonadotropin with LHCGR. It is important that

in -LH and -hCG this segment has a net positive charge, which

determines its interaction with the negatively charged orthosteric site LHCGR

[79, 81]. The C-terminal segment 88–92 of the -subunit of hCG

is also involved in binding to LHCGR [82, 83].

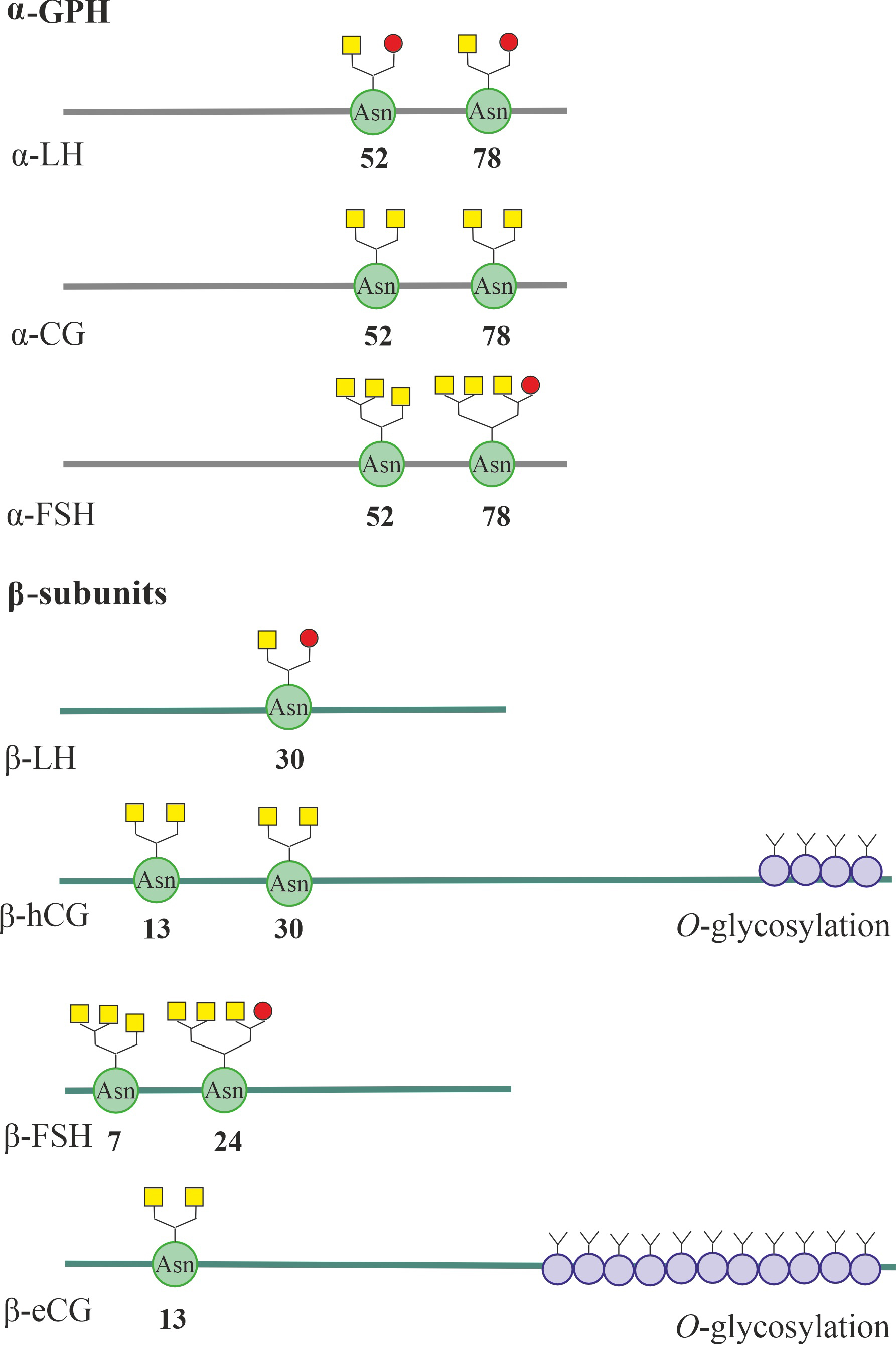

Both - and -subunits of gonadotropins undergo

N-glycosylation because they contain asparagine-containing sites,

targets for N-glycosyltransferases, with the consensus motifs

Lys-Asn-(Val/Ile) or (Glu/Tyr)-Asn-His [18]. In the -subunit, common to

all gonadotropins, two such sites are localized (Asn, Asn), while

in the -subunit there are one (-LH, Asn) or two

(-hCG, Asn and Asn) sites for N-glycosylation.

The -subunit of FSH, like -hCG, also has two sites for

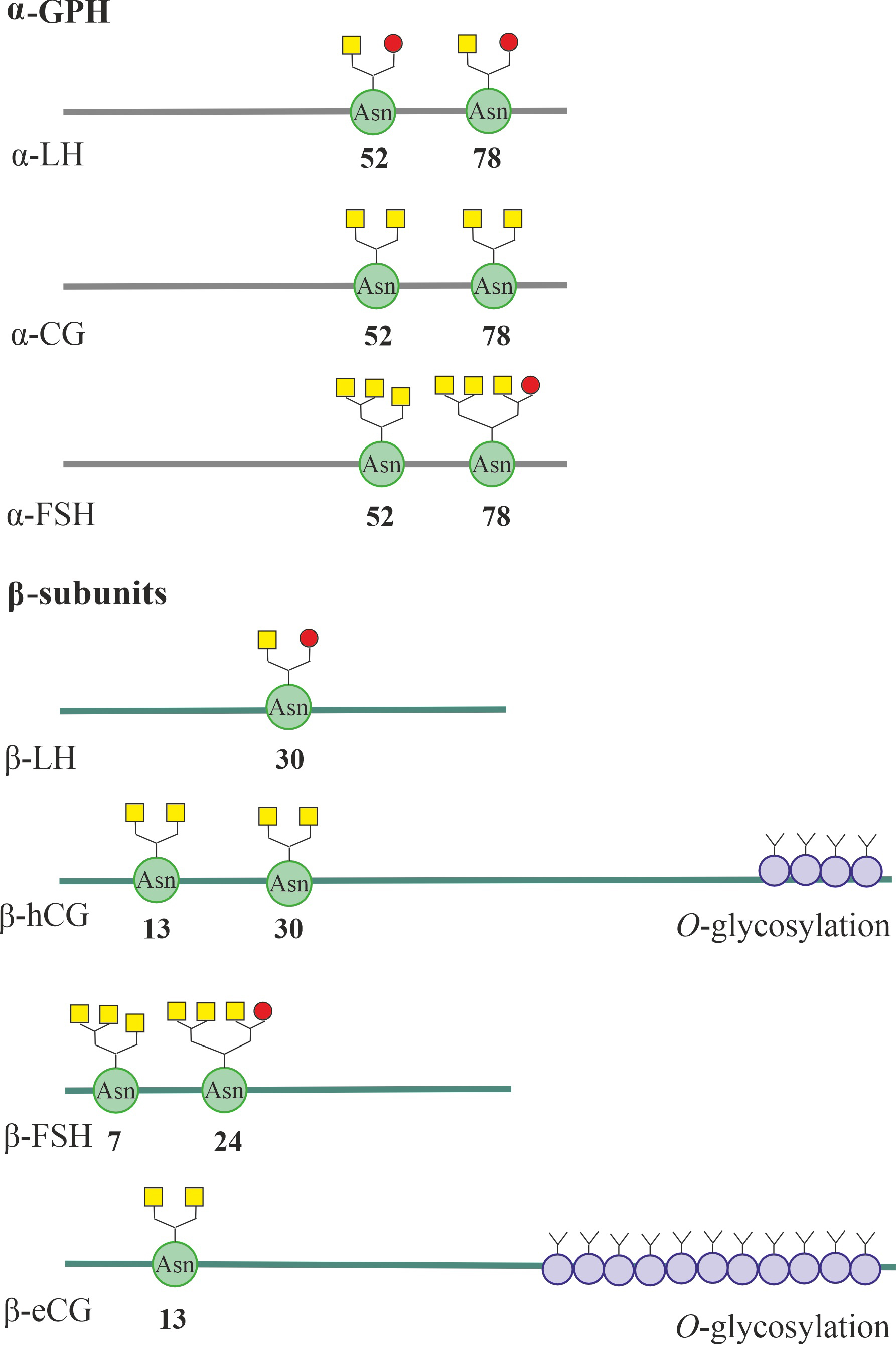

N-glycosylation (Fig. 2). The C-terminal extension of

-hCG also has four sites for O-glycosylation, including the

residues Ser, Ser, Ser, and Ser as targets. Sites

that are modified by N-glycans are located in all three loops (L1–L3)

of the - and -subunits [18, 19, 84, 85] (Fig. 2). The degree

of glycosylation, localization and structure of N-glycans (branching,

charge, etc.) in - and -subunits make a significant

contribution to the formation of gonadotropin heterodimeric complexes and their

stability, and also determine the binding characteristics and effectiveness of

gonadotropins, the bias of their signaling, and affect their pharmacokinetics

[18, 19, 85, 86] (see also Section 6).

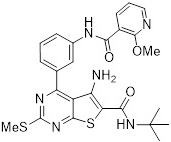

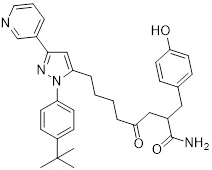

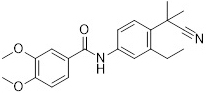

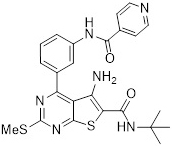

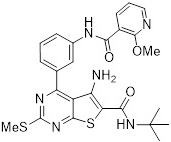

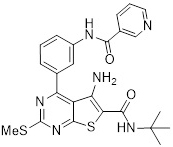

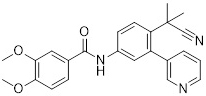

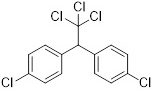

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The N- and O-glycosylation of the

luteinizing hormone (LH) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) subunits, as well

as the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) subunits shown for comparison. For

-LH, -FSH and -CG, glycoforms of

-glycoprotein hormone (-GPH) are presented, characteristic of

the molecules LH, FSH and classical (placental) hCG. All gonadotropin subunits

show sites for N-glycosylation, including asparagine residues. In the

C-terminal part of the -subunits of human and equine CG, sites

for O-glycosylation, including serine and threonine residues, are also

localized. The most typical structures of N-glycans characteristic of

the presented gonadotropins are presented. In the - and

-subunits of human and horse LH and CG, weakly branched (hybrid and

bi-antennary) N-glycans predominate, and in LH secreted by the pituitary

gland there is more terminal sulphated N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc),

and in CG secreted by the fetus and placenta, sialic acid residues predominate.

The - and -subunits of FSH contain a significant number of

more branched (three- and four-antennary) N-glycans enriched in sialic

acid residues. It should be noted, however, that under specific conditions (a

certain phase of the estrous cycle, age, pathological conditions, etc.),

N-glycans can differ significantly structurally, both between the same

types of subunits and between the - and -subunits that form

the dimeric gonadotropin complex. The terminal sialic acid residues are indicated

by yellow squares, and the terminal sulphated N-acetylgalactosamine

(GalNAc) residues are indicated by red circles. CG, chorionic gonadotropin; eCG,

equine chorionic gonadotropin.

A representative of a rather unusual group of gonadotropins with LH activity is

equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG), which is encoded by a single gene and

combines the properties of LH and FSH when acting on the reproductive system of

various (non-equid) mammals [87, 88, 89, 90]. Unlike hCG, the -subunit of eCG

has only one site for N-glycosylation (Asn), but in the

C-terminal region it contains up to 11–12 sites for

O-glycosylation, and the targets of O-glycosyltransferases are

serine (Ser, Ser, Ser, Ser, Ser,

Ser, Ser, and Ser) and threonine residues (Thr,

Thr, Thr, and Thr) [91] (Fig. 2). The degree of

glycosylation of these sites ranges from 20 to 100%, and this is the reason that

-eCG is one of the most highly glycosylated proteins, in which the

glycosyl component accounts for up to 40% of the molecular weight. Along with

-eCG, the horse has -LH, which is also encoded by a single gene

and has dual specificity, activating both gonadotropin receptors, LHCGR and FSHR.

Like -eCG, -eLH has up to 11 sites for

O-glycosylation, but is glycosylated to a lesser extent (the degree of

glycosylation of these sites is from 10 to 77%) [87, 91, 92] (Fig. 2).

3. Structure of the Luteinizing Hormone/Chorionic Gonadotropin Receptor

and the Mechanisms of Its Binding to Gonadotropins

The LHCGR belongs to the superfamily of serpentine receptors functionally

coupled to heterotrimeric G proteins (GPCRs), and is included in the group

of the rhodopsin family, together with FSHR, thyroid-stimulating

hormone receptor (TSHR), and relaxin and insulin-like factor-3 (INSL3) receptors.

Gonadotropins bind specifically to the high-affinity orthosteric site of LHCGR,

which is formed by a large extracellular domain, similar to that observed in

other receptors of the group.

The LHCGR ecdomain includes up to 360 AARs and contains two structural

subdomains, the first of which includes 9 leucine-rich repeats (LRRs), while the

second is a large hinge region. connecting the LRR subdomain to the TMD. The main

structural elements of the TMD are seven hydrophobic transmembrane helices (TMs)

that form the transmembrane tunnel. At the N- and C-termini of

the hinge region there are two more LRR segments, LRR10 and LRR11, between which

the -helix Pro–Asn (hinge helix) and an extended hinge

loop [28]. At the C-terminus of the hinge region, where the

extracellular domain connects to the TMD, a small region of P10

(Phe–Tyr) is located. The hinge region finely regulates the

binding of gonadotropins to the ectodomain and ensures the signal transduction

generated by them to the TMD, largely determining the differences in LH- and

hCG-induced intracellular signaling [28, 93].

The surface of hCG, which is an -heterodimer complex,

contains clusters enriched with positively charged AARs that electrostatically

interact with clusters of negatively charged AARs that form the ligand-binding

surface of the LHCGR ectodomain. Using cryoelectron microscopy, it was shown that

both subunits, the hCG-specific -subunit and the -subunit

common to all glycoprotein hormones (-GPH), are involved in the

interaction with LHCGR. The C-terminal segment 92–106 of -hCG

specifically interacts with the residues Arg, Ser, Ala and

Tyr, located in LRR1, and with the Glu, located in LRR7, and the

residues Val and Gln of -hCG form contacts, respectively,

with the residues Gln and Arg located in LRR10. In turn, residues

Tyr, Tyr, and Ser of -GPH interact with residues

Tyr, Ile, Lys, and Tyr, located in LHCGR repeats

LRR4–LRR6 [28]. When hCG binds to the receptor, significant conformational

changes are observed in four segments: in a region localized in -hCG,

called the “seat belt”, which is responsible for stabilizing the

-heterodimer of hCG, as well as in -sheet structures

localized in -hCG (L2, L3) and -hCG (L3) [28, 94]. Despite the

similarity of the “seat belt” in the -hCG and -LH, there are

significant differences between the -sheet structures of these subunits,

which entails significant differences in the efficiency of their interaction with

LHCGR and in the ability to selectively activate intracellular signaling

cascades, first all due to the different pattern of their interaction with the

hinge region LHCGR [28, 93].

As in the case of a number of other representatives of class A GPCRs, during

gonadotropin-induced activation of LHCGR, a change in the superposition of the

TM6 helix and the interacting TM5 and TM7 helices in the TMD occurs, despite the

fact that gonadotropin binding occurs in the extracellular part of LHCGR. Changes

in the relative position of TMs and the configuration of the internal cavity of

the TMD are a trigger for conformational changes in the heterotrimeric G protein

associated with the cytoplasmic regions of the receptor. These conformational

changes promote the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)/guanosine triphosphate (GTP)

exchange in the G subunit of the G protein and weaken its association

with the G dimer, which leads to the activation of G

subunit and G dimer-dependent intracellular signaling

cascades.

When hCG binds to LHCGR, the C-terminal segment of the TM6 moves

outward (by 12.8 angstroms), and this is accompanied by a slight outward shift

(by 2 angstroms) of the TM5 helix and an inward shift (by 3.6 angstroms) of the

TM7 helix [28]. An assessment of the distance between different segments of the

TM6 and TM7 by Xinheng He and his colleagues [95] using molecular dynamics showed

that when LHCGR binds to hCG, the distance between them increases both in the

outer vestibule of the transmembrane tunnel and in its central part, and this is

accompanied by a significant increase in the volume of the internal cavity of the

transmembrane tunnel. As a result, in the hCG-bound LHCGR, the average distance

between the -carbon atoms of the Ala and

Lys residues, localized in the extracellular ends of the TM6 and

TM7, is 12.9 1.3 angstroms, while in the hormone-unbound receptor it is

significant in short, only 7.7 3.5 angstroms. The distance between the

-carbon atoms of residues Cys and Asn,

located in the central part of the TM6 and TM7, in hCG-bound LHCGR is 8.5

0.2 angstroms, which also, although to a small extent, exceeds this value in

hormone-free receptor (7.2 0.9 angstroms).

It should be noted that in the ternary complex of hCG–LHCGR–G protein,

the distance between the TM6 and TM7 is similar to that in the double complex of

hCG–LHCGR. It is important that the calculated volume of the internal cavity of

the TMD for the double (253.7 121.1 Å) and ternary (188.4

111.3 Å) complexes significantly exceeds that for the

hormone-free receptor (313.03 162.09 Å) [95]. In this case, the

entrance to the transmembrane tunnel expands to the greatest extent, which also

occurs when small ligands bind to the TMD of a large number of GPCRs [96]. The

result of an increase in the volume of the internal cavity of the TMD and

associated changes in the superposition of its TMs is a change in the

conformation of the cytoplasmic regions proximal to the membrane, belonging to

its second and third ICLs (ICL2, ICL3) and the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain.

These regions contain the main molecular determinants responsible for the

interaction of LHCGR with various types of G proteins and -arrestins.

The basis for changes in the superposition of TMs upon activation of LHCGR by

gonadotropin is a change in the interaction between the LRR subdomain and the

hinge region of the ectodomain, on the one hand, and the TMD, primarily the ECLs,

forming the outer vestibule of the transmembrane tunnel, on the other [95]. In

the absence of hormonal activation, the close interaction between the LRR

subdomain and the TMD ensures that the latter remains in an inactive state. After

binding to gonadotropin, the interaction of the LRR subdomain with the TMD is

weakened, as indicated by a significant increase in the distance between them. In

this case, the LRR subdomain moves into a vertical position relative to the TMD.

In turn, the hinge region, on the contrary, as a result of its rotation,

approaches the extracellular vestibule of the TMD, while simultaneously moving

away from the LRR subdomain [97]. This is indicated by the results of assessing

the mobility and structural changes in the LRR subdomain, hinge region and TMD of

LHCGR during its transition from the active to the inactive state using molecular

dynamics methods. Calculations show that upon activation of LHCGR, the distance

between the LRR subdomain and the TMD can increase on average from 60 to 88

angstroms, while the distance between the hinge region and the TMD decreases from

79 to 48 angstroms [97]. Of key importance in the association and functional

coupling of the ectodomain and the TMD of LHCGR are the interactions between the

helix of the hinge region of the ectodomain and the helix formed by the middle

part of ECL1, as well as the interactions between the C-terminal segment

P10 of the hinge region, which borders the upper part of the TMD bundle, with one

side, and the outer vestibule of the transmembrane tunnel formed by the

extracellular ends of helices TM1, TM2 and TM7 and all three ECLs, on the other

[28, 95, 98, 99]. A change in the nature of these interactions upon binding of

LHCGR to gonadotropin affects the relative position of the TM5, TM6 and TM7

helices and the conformation of the TMD as a whole, including its cytoplasmic

regions, thereby activating intracellular signaling.

Among the molecular determinants located in the LHCGR ectodomain that mediate

its activation by gonadotropin, the Tyr residue plays an extremely

important role, which undergoes sulfation at the hydroxyl group in the phenolic

ring and therefore acquires a negative charge. This residue is located in the

middle of the hinge region and is surrounded by negatively charged AARs, thereby

forming a cluster with a high negative charge density. The Tyr and its

neighboring residues Asp and Glu electrostatically interact with

positively charged hCG clusters, thereby controlling the relative position of the

hinge region and the TMD of LHCGR. Substitutions of these residues with other

AARs that disrupt the integrity of the anionic cluster prevent effective

interaction with gonadotropin and lead to a significant decrease in its ability

to activate LHCGR [100]. Another important determinant is Ser, which is

involved in the formation of the Pro–Asn helix, localized in the

N-terminal part of the hinge region. It mediates the interaction of

helix 272–280 with the ECL1 helix and thereby modulates the stability of the

complex between the ectodomain and the TMD. It is also suggested that the

hydroxyl group of Ser is capable of forming a hydrogen bond with

Asn, located in the highly conserved region P10 [28], which is often

considered as a tethered agonist for LHCGR [98]. It should be noted that a

structurally similar region is also localized in the corresponding TSHR locus,

which also functions as a tethered agonist.

Along with the full-length forms of LHCGR, shortened soluble forms that lack the

transmembrane domain are generated in men and women [101, 102]. The blood level

of the soluble LHCGR form negatively correlates with the success of embryo

implantation and is one of the risk factors for premature birth and miscarriage

[103]. Soluble LHCGR forms, localized in the cytosol, make a significant

contribution to the malignancy of adrenal cells [104]. These forms of the LHCGR

are capable of negatively influencing LH signaling by suppressing the effects of

LH and hCG, including the formation of inactive heterodimeric complexes with

protomers of the full-length LHCGR, and thus can be considered as negative

allosteric LHCGR modulators [105]. In addition, the protomers of the soluble

LHCGR form a complex with FSHR and prevent its translocation into the plasma

membrane, thereby reducing the number of surface FSHRs and weakening

FSH-dependent responses [106].

4. Common Principles of Organization and Functioning of

Gonadotropin-Regulated Signaling Cascades

4.1 Intracellular Signaling Cascades, Targets of LH and hCG

Specific binding of -heterodimers of LH and hCG to the

extracellular domain of LHCGR induces conformational rearrangements in it, which,

as noted above, affect the hinge region and the ECL2 and ECL3 contacting this

region. The relative position and conformational mobility of ECL2 and ECL3

directly affect the structure of the TMD and the interaction of ICL2 and

especially ICL3 with the G proteins and -arrestins. Using a multi-step

mechanism of conformational rearrangements, gonadotropins regulate intracellular

signaling cascades, both through the activation of various types of G proteins

associated with LHCGR, and by recruiting adapter and regulatory proteins,

including various isoforms of -arrestins, into complex with the

receptor. It is necessary to take into account the fact that LHCGRs embedded in

the membrane are capable of forming both homodimeric (homooligomeric) complexes

and heterodimeric (heterooligomeric) complexes with other GPCRs, including FSHR.

This will have a significant impact on the molecular mechanisms and selectivity

of signal transduction from the extracellular domain of LHCGR to intracellular

effector proteins. Transactivation of LHCGR is also important. It consists in the

fact that the hormone binds to one of the protomers of the di(oligo)meric

receptor complex, while signal transduction to intracellular effectors occurs

through another protomer, and the latter can be the protomer of another GPCR, for

example, FSHR.

Two pathways play a decisive role in the implementation of gonadotropin

signaling via LHCGR [12, 14, 15]. There are the cyclic adenosine monophosphate

(cAMP)-dependent pathway, including LHCGR–G protein–adenylyl cyclase

(AC)–cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA)/Exchange Protein directly activated by Cyclic

AMP (EPAC) family factors, and the phospholipase pathway, including

LHCGR–G protein–phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C

(PLC)–diacylglycerol (DAG)/inositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (IP3)–protein

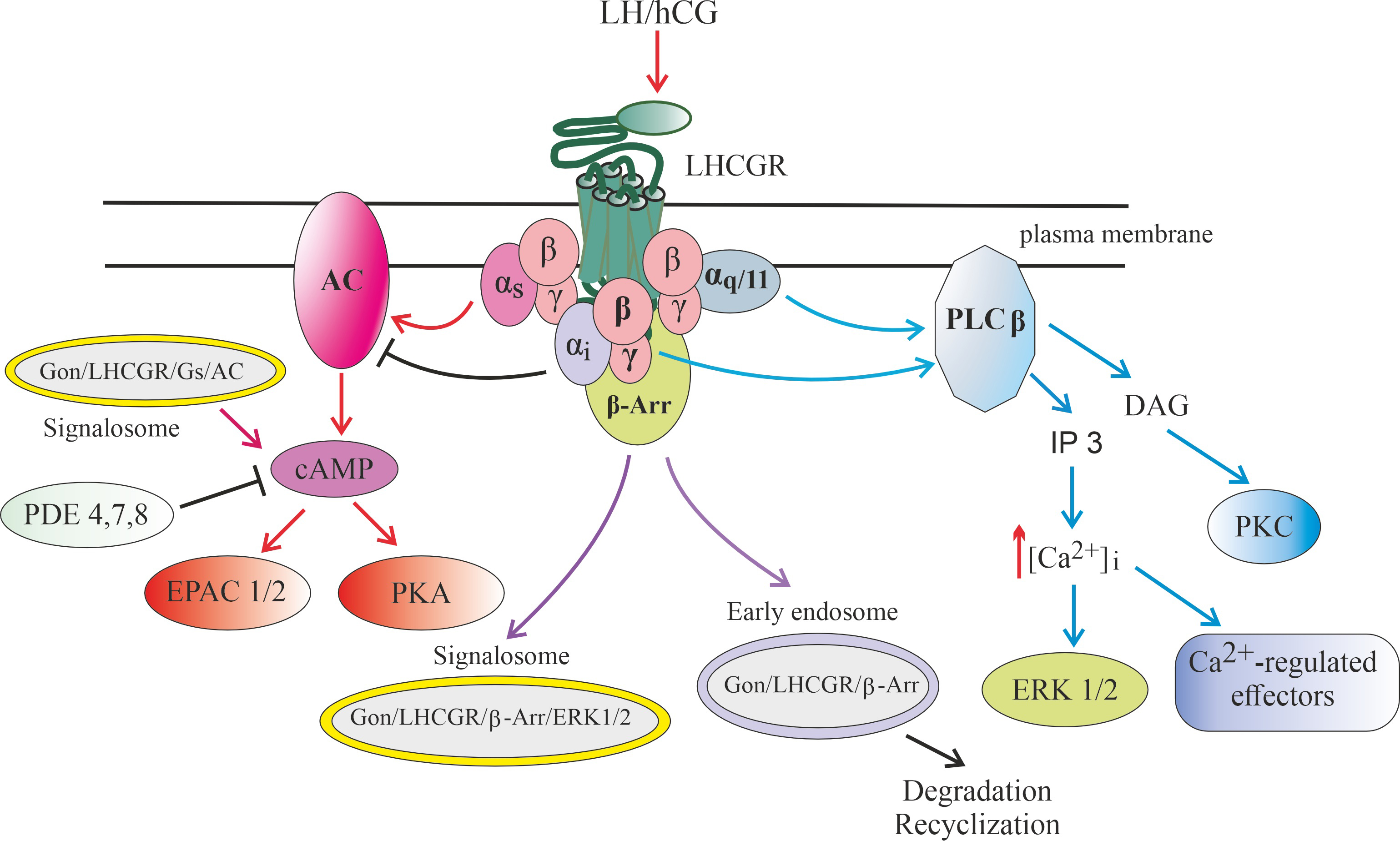

kinase C (PKC)/calcium signaling (Fig. 3). In cells of the reproductive system,

they participate in the gonadotropin-induced regulation of steroidogenesis, in

the control of proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, autophagy and other

fundamental cellular processes [12, 14, 15]. In this case, -arrestin

pathways, which have been intensively studied recently, also play a significant

role. Through them, the cascade of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) is

activated, the regulation of which can also be carried out through a G

protein-dependent pathway, including cAMP-activated PKA (Fig. 3). These signaling

pathways themselves and their regulation by gonadotropins with LH activity are

discussed below, with an emphasis on the differences in the signaling properties

of LH and hCG.

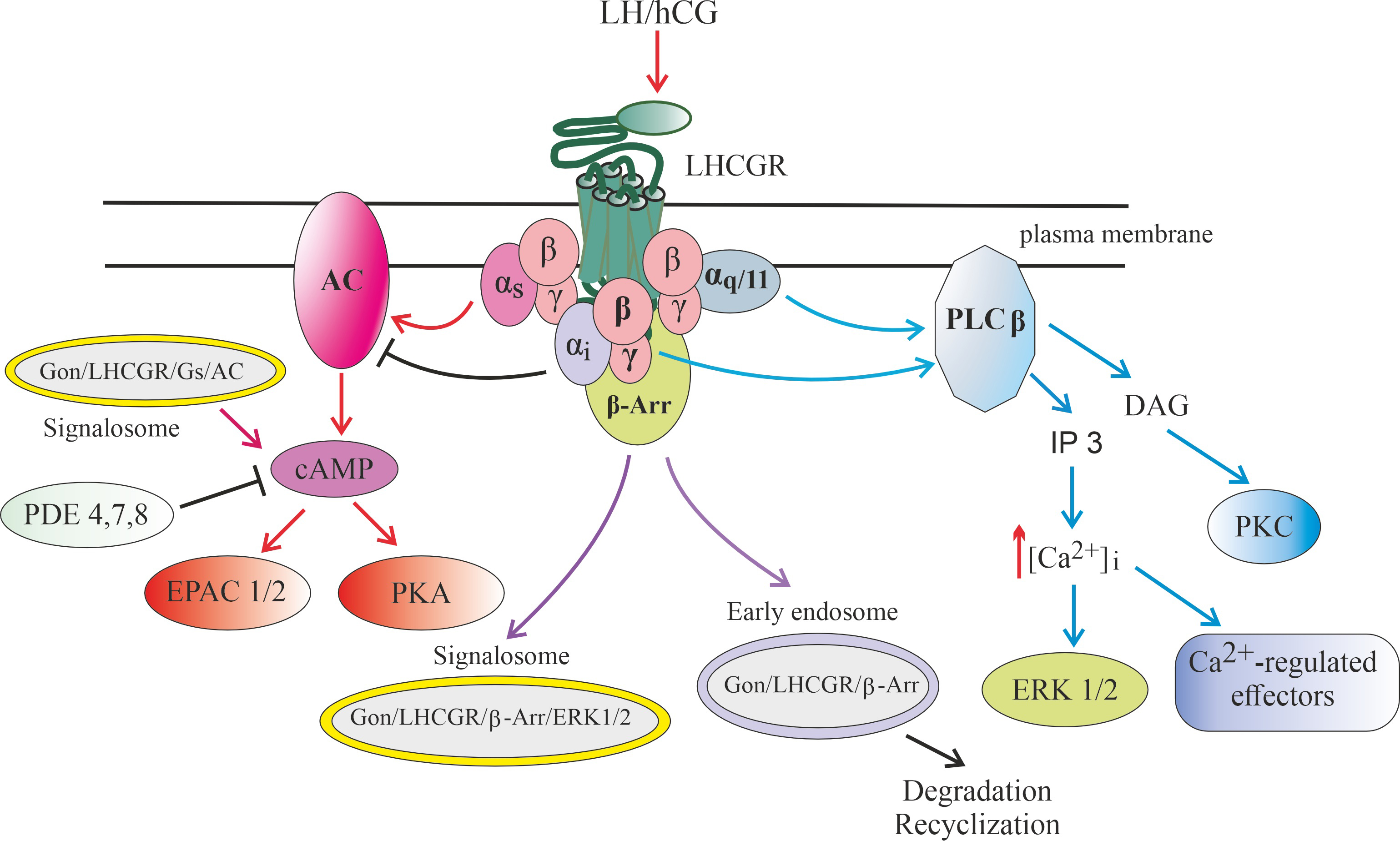

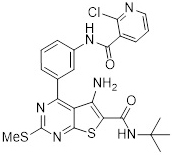

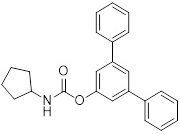

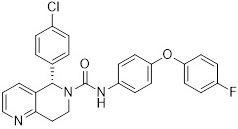

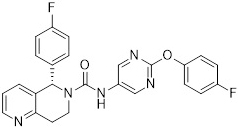

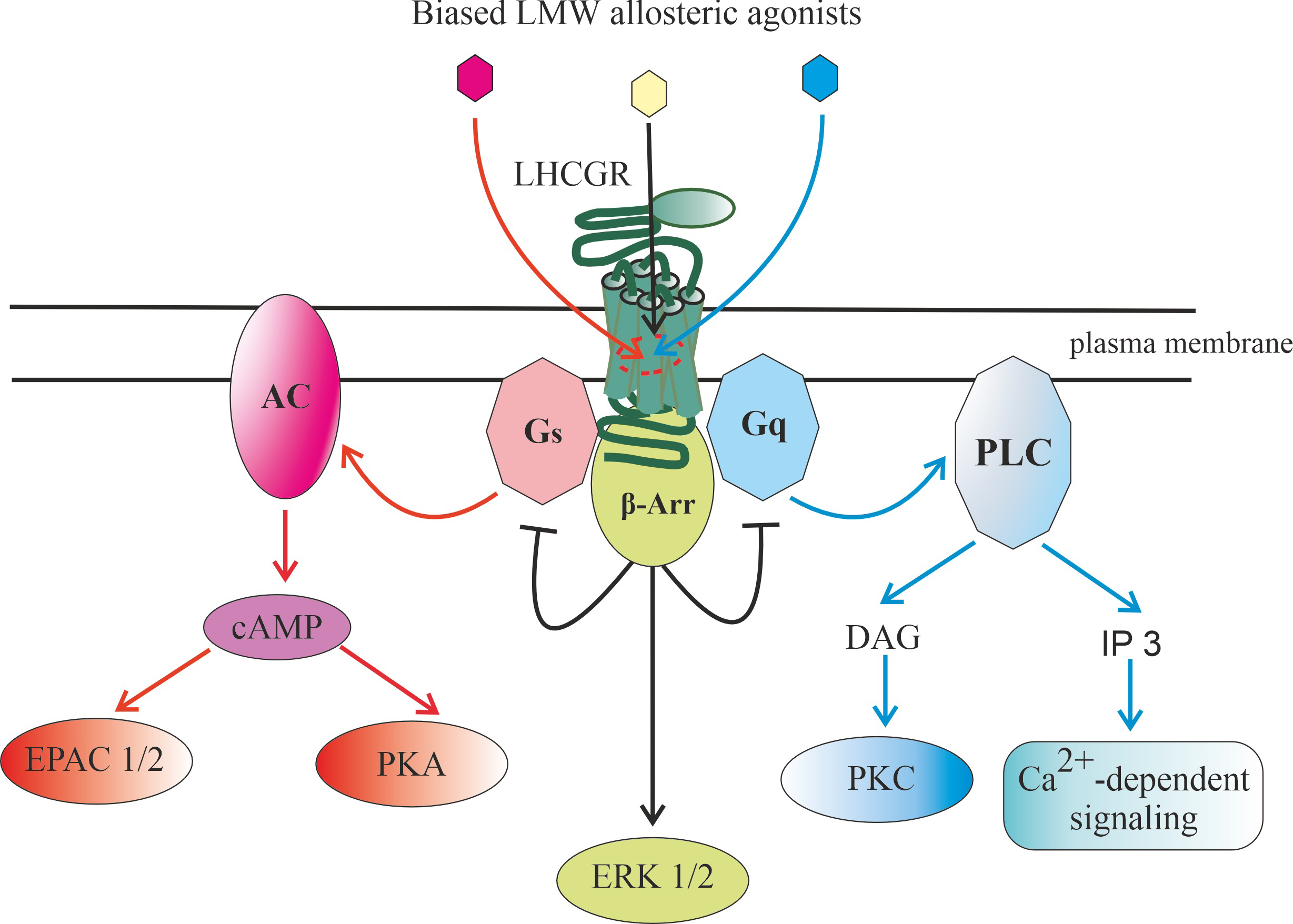

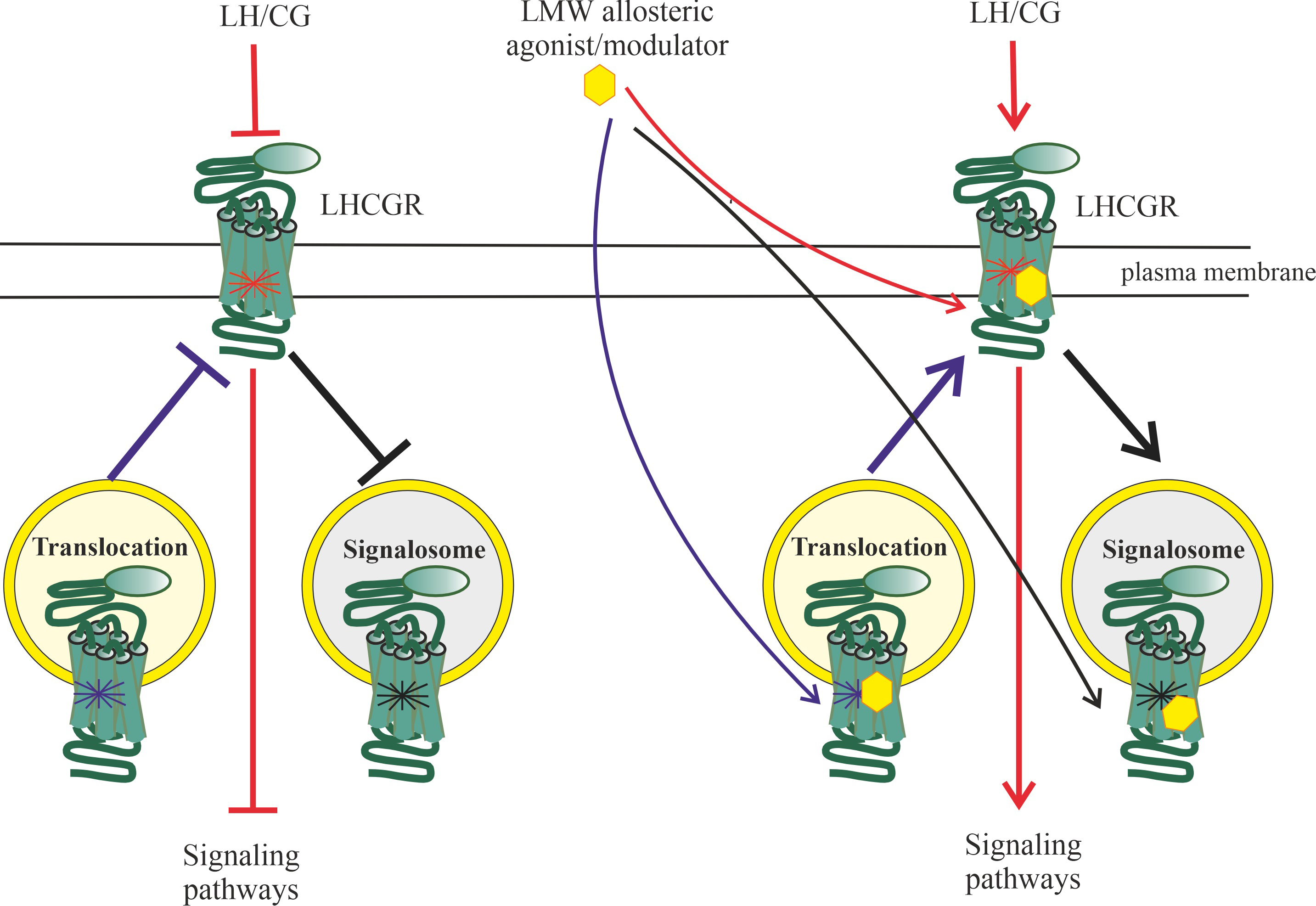

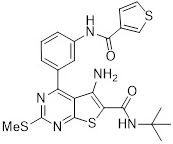

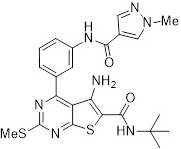

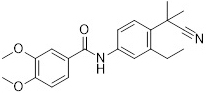

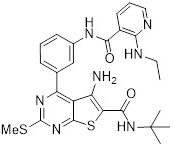

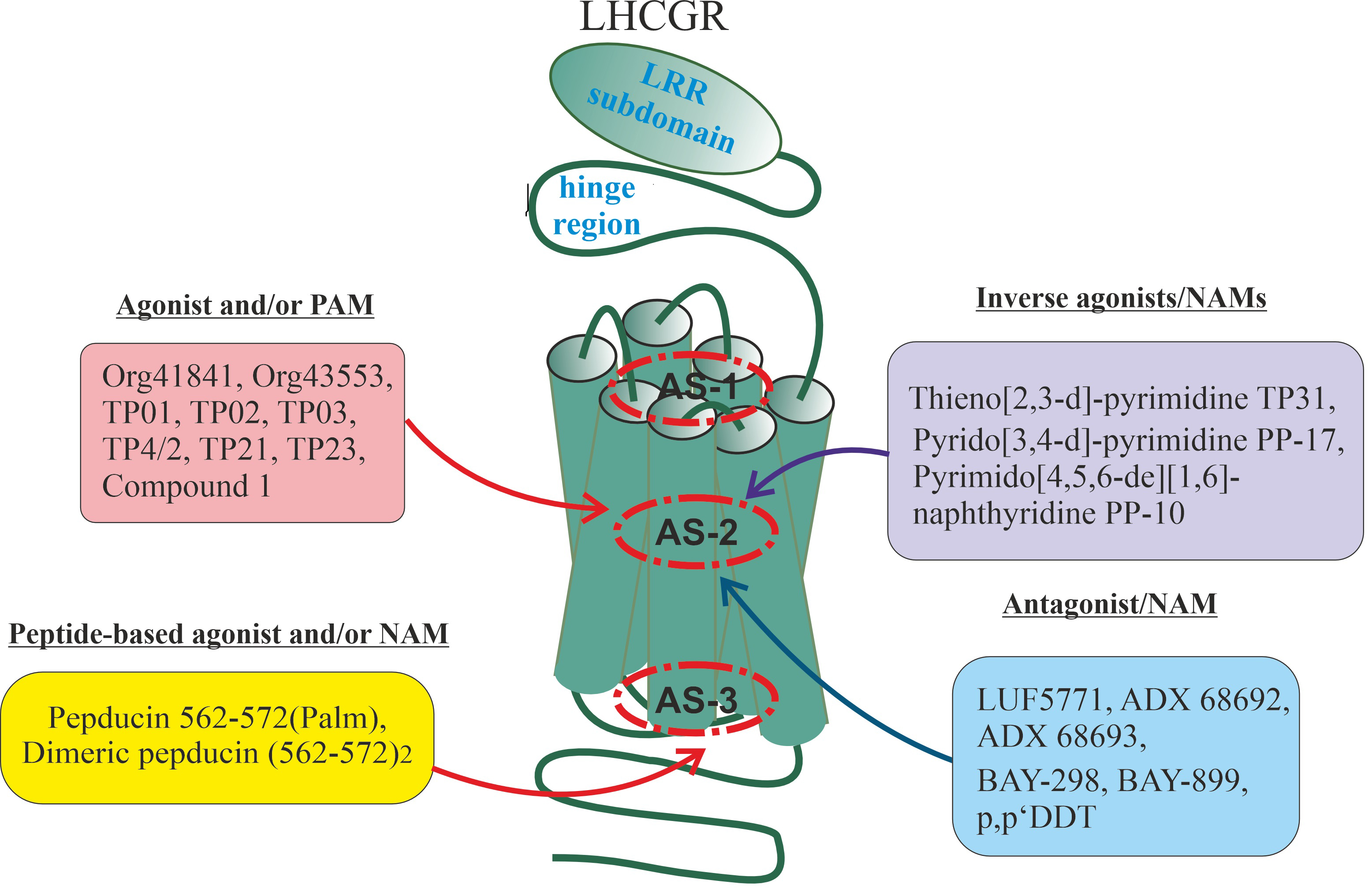

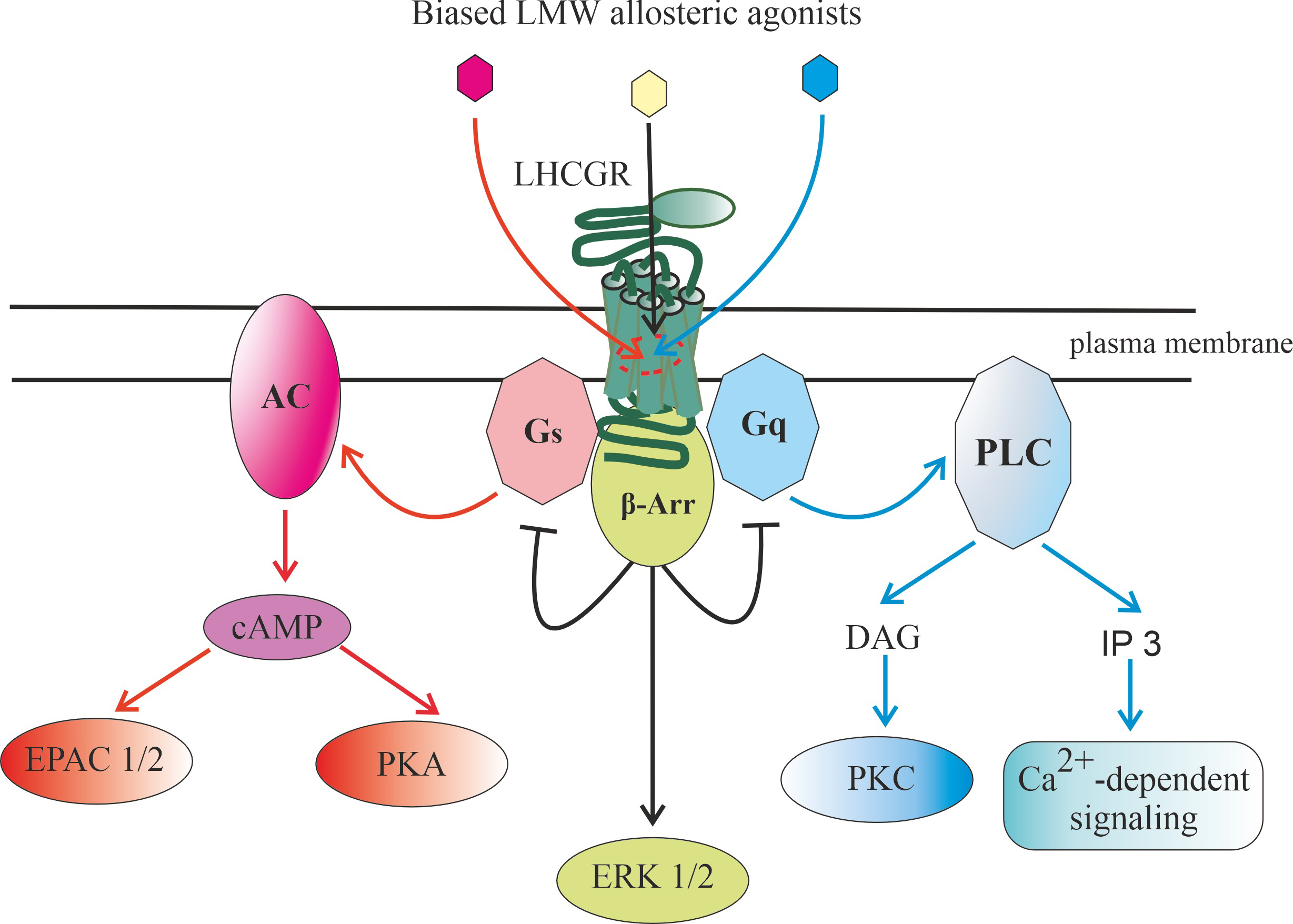

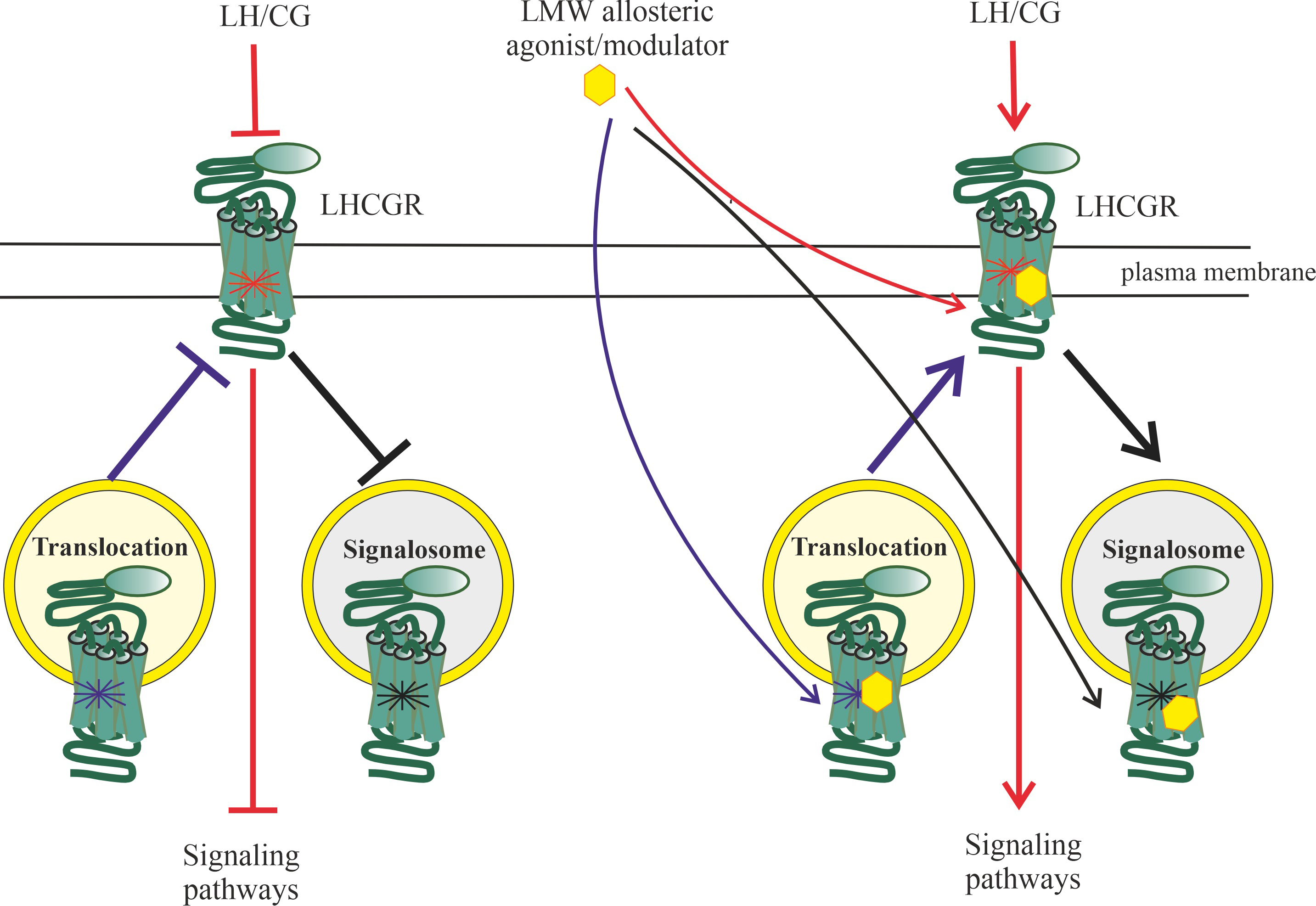

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Signaling pathways realized through luteinizing

hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor (LHCGR), as well as endosomal signaling

carried out with the participation of gonadotropin-bound LHCGR. Abbreviation: AC, adenylyl cyclase; cAMP, 3-5-cyclic adenosine

monophoshate; -Arr, -arrestin; [Ca], intracellular

concentration of calcium ions; DAG, diacylglycerol; EPAC1/2, Exchange Protein

directly activated by Cyclic AMP, types 1 and 2; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinases, types 1 and 2; , ,

, subunits of

-heterotrimeric G, G and G

proteins, respectively; IP3, inositol-3,4,5-triphosphate; LHCGR, receptor of

luteinizing hormone (LH) and chorionic gonadotropin (CG); PDE4,7,8,

cAMP-activated phosphodiesterases, types 4, 7 and 8; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC,

phorbol-sensitive protein kinase C, isoforms and ;

PLC, phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C.

Binding of LH or hCG to the receptor leads to its transition to an active

conformation and triggering of several intracellular signaling cascades, which

can be carried out both through various classes of heterotrimeric G proteins and

through arrestins. After activation of the G protein, a free GTP-bound

subunit is formed, which mediates stimulation of the

membrane-bound AC, and this leads to an increase in the level of intracellular

cAMP and stimulation of PKA and/or factors of the EPAC family.

Along with this, after the formation of the gonadotropin-receptor-G

protein-AC complex, it is possible to form a signalosome that includes this

complex, which is translocated into the cell, providing a targeted increase in

the level of cAMP in its individual compartments. PKA phosphorylates a large

number of intracellular proteins that have specific sites for PKA

phosphorylation, including the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding

protein (CREB), and this largely ensures the regulatory effects of gonadotropins

on steroidogenesis, maturation of generative cells, as well as on metabolism,

growth, and survival of cells of the reproductive system.

Gonadotropin-induced dissociation of G protein leads to the generation

of a free subunit, which activates PLC, which

catalyzes the formation of second messengers, DAG and IP3. DAG causes stimulation

of DAG/phorbol-activated PKC isoforms and PKC-mediated phosphorylation of

intracellular effector proteins, while IP3 leads to activation of calcium

channels of the endoplasmic reticulum, causing the release of Ca from

intracellular stores and changes in the activity of many Ca-dependent

proteins, as well as activation of the MAPK cascade, primarily the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2). Some PLC

isoforms, PLC2 and PLC3, can also be activated by the

dimer, the main donor of which is the G protein. In

this case, the subunit formed during the dissociation of this

protein can have an inhibitory effect on gonadotropin-induced AC activation,

preventing the overproduction of cAMP. In addition, a decrease in the level of

cAMP occurs due to its hydrolysis by cAMP-specific phosphodiesterases, such as

type 4 phosphodiesterase (PDE4), PDE6 and PDE7.

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRK)-mediated phosphorylation following hormonal activation of the LHCGR leads to

the recruitment of -arrestins, which not only inhibit G protein

signaling, but also lead to the formation of early endosomes into which the

ligand-receptor complex is included. Depending on the pattern of GRK

phosphorylation, the resulting endosomes can either provide endosomal trafficking

of such a complex with its subsequent lysosomal degradation or recycling of the

LHCGR into the plasma membrane, or form a signalosome responsible for the

activation of intracellular effectors, including ERK1/2, the effector components

of the MAPK cascade.

4.2 cAMP-Dependent Signaling Pathways

Hormones, including LH and hCG, stimulate cAMP-dependent effector proteins and

transcription factors through the “classical” AC signaling system, including as

the main components GPCR, a heterotrimeric G protein consisting of a

G subunit and a G dimer, and a membrane-bound

isoform of AC, the catalytic component of this system. AC catalyzes the reaction

of converting ATP into cAMP, which is a universal second messenger. After binding

to the hormone, the conformation of the G protein-binding surface of the receptor

changes, which includes segments of the ICLs and the intracellular vestibule of

the tunnel formed by the TMD. This ensures effective interaction of the receptor

with the G protein and its activation, including the replacement of GDP in

the guanine nucleotide-binding site of the G subunit with GTP and

the subsequent dissociation of the GTP-bound G subunit from the

G dimer. The monomeric Gs subunit in the active,

GTP-bound state is capable of maintaining weak bonds with the

G dimer, which allows it later, after hydrolysis of GTP and

the transition of the G subunit to the inactive, GDP-bound state,

to reassociate with G dimer at a high rate to form the

inactive complex. The GTP-bound G subunit interacts with

regulatory sites of AC, causing an increase in its catalytic activity and

stimulating the production of intracellular cAMP.

Synthesized cAMP interacts with effector proteins specific to it, primarily with

serine/threonine PKA and factors of the EPAC (Exchange Protein directly activated

by Cyclic AMP) family, which are also called cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide

exchange factors exchange factor (cAMP-GEF) (Fig. 3). PKA in its inactive state

is a heterotetrameric complex consisting of two regulatory (inhibitory) and two

catalytic subunits. Each regulatory subunit includes two cAMP binding sites and

two sites located in the N-terminal region that interact with the

catalytic subunits [107]. When bound to cAMP, the regulatory subunits dissociate

from the complex, the released catalytic subunits are activated and catalyze the

transfer of the -phosphate group from ATP to the

serine/threonine-containing site of the phosphorylated protein, the target of

PKA. The main targets of the enzyme are cAMP-regulated transcription factors,

including the factor CREB (cAMP-responsive element binding protein), which

controls the expression of many genes.

The EPAC family factors, Epac-1 (cAMP-GEF-I) and Epac-2 (cAMP-GEF-II), have one

(Epac-1) or two (Epac-2) cAMP-binding sites in the N-terminal part, and

in their C-terminal part there is a catalytic GEF domain, the function

of which is to ensure GDP/GTP exchange and activation of small G proteins, such

as Rap1 and Rap2 [108]. As in the case of PKA, one of the targets of the EPAC1

and EPAC2 is the transcription factor CREB, through which they regulate gene

transcription, cell growth, apoptosis, cell migration, and mitochondrial dynamics

[109]. It should be noted that, in addition to the activation of small G

proteins, EPACs also activate a number of other effector proteins, including

PLC [110], Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)

[111], phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [112], and the components of the MAPK

cascade [113, 114]. All this significantly expands the range of their

physiological effects in response to cAMP stimulation. Since the dissociation

constants for the binding of cAMP to PKA and EPACs have similar values, in each

specific case the choice of effector is determined not by the intensity of cAMP

production, but by the availability of PKA and EPACs for activation by the cyclic

nucleotide [115].

In addition to the effector components of cAMP signaling, phosphodiesterases

(PDEs) play a significant and, in some cases, a decisive role in its regulation,

causing the degradation of cyclic nucleotides, including cAMP, and thereby

terminating the transduction of cAMP-dependent signals into the cell. The cells

of the male and female reproductive system contain PDE4, PDE7 and PDE8, which are

highly selective towards cAMP and hydrolyze it to inactive adenosine

5-monophosphate (Fig. 3). Importantly, the expression and activity of these

PDEs are characterized by cell and tissue specificity. In the ovaries, the PDE8A

and PDE8B isoforms are found in significant quantities in theca cells and

oocytes, the PDE4A isoform is found in oocytes and medullar stromal tissue, the

PDE4C and PDE4D isoforms are found in follicles, the PDE7A and PDE7B isoforms are

found in oocytes, while the PDE4B isoform is mainly in the outer layer of theca

cells [116]. Dual-specificity PDEs that hydrolyze both cAMP and cyclic guanosine

monophosphate (cGMP) may play a certain role in the control of cAMP signaling,

for example, the ovarian isoform PDE3B. The hydrolytic activity of PDE7 and PDE8

is detected even at low concentrations of cAMP inside the cell, while PDE4 is

activated only by relatively high concentrations of cAMP, under conditions of

intense AC stimulation with gonadotropins [116]. Leydig cells have demonstrated

high activity of the PDE8A and PDE8B isoforms and have been shown to be involved

in the regulation and modulation of the steroidogenic effects of gonadotropins

through cAMP-dependent pathways, and inhibition of these PDEs leads to increased

signal transduction, similar to hormonal stimulation [117, 118]. Thus, specific

PDE inhibitors mimic the stimulating effect of gonadotropins with LH activity on

target cells, which is of great practical importance for the pharmacology of

reproductive disorders [116, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122].

Phosphatases, which are targets for PKA and undergo phosphorylation, can also

play a certain role in the transduction of the LH-induced signal. It has been

shown that in ovarian granulosa cells the protein phosphatase 1 regulatory

subunit 12A (PPP1R12A) and serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A 56 kDa

regulatory subunit delta isoform (PPP2R5D) undergo cAMP-dependent

phosphorylation, which leads to changes in the functional activity of the enzymes

and causes dephosphorylation and inactivation of the receptor guanylate cyclase

natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (NPR2), which is involved in the control of oocyte meiosis [123]. However, there is

no reliable data on the direct influence of phosphatases on upstream components

of cAMP signaling.

Important for cAMP signaling are scaffold proteins, which ensure the integration

of GPCR, G proteins, AC, PKA, PDEs and other signaling and effector proteins into

multicomponent molecular assemblies. Among scaffold proteins, proteins of the

A-Kinase Anchoring Proteins (AKAP) family, which specifically interact with the

regulatory subunit of PKA, play an important role in the control of cAMP

signaling. This interaction includes the N-terminal helical domain of

the PKA regulatory subunit, responsible for its dimerization and docking

(N-terminal Dimerization/Docking domain), and the amphipathic

-helix of AKAP. These helical regions form a superhelical structure

responsible for the retention of PKA in a particular cellular compartment and for

the specificity of its interaction with target proteins [124]. Ezrin, radixin and

moesin (ezrin-radixin-moesin, ERM), which are responsible for the formation and

reorganization of the cytoskeleton and lipid rafts, participate in the regulation

of the activity of EPACs. By specifically interacting with the

N-terminal region of EPAC1, ERM proteins ensure the translocation of

EPAC1 to the membrane and its inclusion in the signalosome, thereby redirecting

cAMP signaling to the EPAC-dependent pathway [125].

4.3 Phospholipase Signaling Pathways

The result of hormonal activation of the G protein, mediated through

GPCRs, including LHCGR, is the exchange of guanine nucleotides in the

-subunit of the G protein, the dissociation of the GTP-bound

G subunit from the G dimer and its

functional interaction with phosphoinositide-specific PLC. Activated in

this way, PLC hydrolyzes the membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol

4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), generating two important second messengers, such as

membrane-bound diacylglycerol (DAG) and water-soluble inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate

(IP3). DAG causes activation of phorbol-sensitive PKC isoforms, while IP3

mobilizes calcium ions from intracellular stores [126, 127, 128] (Fig. 3). The

regulatory effects of IP3 are realized through its binding to IP3-specific

receptors localized in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum [129]. This

leads to the leakage of calcium ions from intracellular stores, an increase in

their concentration in the near-membrane space of the endoplasmic reticulum and,

as a consequence, to the activation of Ca-activated ryanodine receptors,

which have a high conductivity for Ca [130]. A rapid increase in Ca

concentration inside the cell leads to the activation of a large number of

calcium-regulated proteins, primarily Ca-calmodulin-dependent, among which

the most important are various isoforms of Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase II [127]. The rapid increase in Ca concentration in certain cell

compartments caused by IP3 is subsequently quickly eliminated by pumping

Ca out of the cytosol using both plasma membrane calcium channels and

Ca-ATPases localized in the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane. This is due

to the need to protect cells from hyperactivation of Ca-dependent effector

systems, which reduces cell survival. Termination of the G-mediated

signal is also carried out by the elimination of DAG and IP3, which are recycled

and, after phosphorylation, are converted back into PIP2, replenishing the

reserves of this phosphoinositide for the subsequent signal transduction cycle

[131, 132]. Within just a few minutes after hydrolysis induced by activation of

the G-mediated phospholipase pathway, rapid restoration of the PIP2 pool

begins, despite continued exposure of the cell to the hormonal stimulus.

Back in the early 1990s, it was found that the hormone-activated G

protein, or more precisely its G subunit, stimulates all four

known isoforms of PLC (PLC1, PLC2, PLC3 and

PLC4), while two of them, PLC2 and PLC3, can also be

activated by the G dimer, the main donor of which is the

pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins [133, 134, 135]. Since the generation of

free G dimer occurs mainly due to the activation of

G-coupled GPCRs, their agonists, like agonists of G-coupled

GPCRs, can activate phospholipase pathways. Moreover, in the case of

PLC2 and PLC3, a synergistic calcium response can be observed

when agonists act simultaneously on G- and G-coupled GPCRs

[136]. Another possibility is a synergism between the G- and

G-mediated signaling pathways, which are activated by the hormone through

the same GPCR, characterized by coupling to both types of G proteins, which is

also true for LHCGR.

The target of the G subunit and G dimer is

the C-terminal domain of PLC, which, being in close interaction

with the catalytic domain, inhibits the hydrolytic activity of PLC. In

the case of the G subunit, both the distal and proximal

regions of the C-terminal domain are involved in binding to it, while in

the case of the G-dimer, only its distal regions, and the

interaction of PLC with the G dimer induces more

pronounced conformational changes in the C-terminal domain [137]. In

both cases, binding of the C-terminal domain to the G protein prevents

the inhibitory effect of this domain on the catalytic domain and ensures high

levels of PLC activity.

4.4 -Arrestin Signaling Pathways

Adapter proteins -arrestins, which, like G proteins, are capable of

specifically interacting with the membrane-proximal regions of the ICLs and the

cytosol-oriented vestibule of the GPCR transmembrane tunnel, are present in all

types of cells and tissues and are involved in the control of most physiological

processes [138, 139, 140, 141]. Of decisive importance for GPCR signaling, including that

realized through LHCGR, are two forms of -arrestins, such as

arr1 and arr2, which are also designated as

-arrestins-2 and -3 (78% homology of the primary structure).

arr1 and arr2 are cytosolic proteins, although arr1

can be localized within the nucleus. Their main function is the ability to

disrupt the interaction of ligand-activated GPCR with G protein and cause

internalization of the ligand-receptor complex within the early endosome into the

cell [142]. Along with this, -arrestins form an active complex with

GPCRs, which has its own signaling functions. This complex is responsible for the

activation of a number of intracellular effectors, including ERK1/2

(extracellular signal-regulated kinases, types 1 and 2), the effector

components of MAPK cascade [141]. Formation of an active complex with the

receptor requires dephosphorylation of Ser (arr1) or Thr

(arr2) located in the C-terminal part of -arrestins,

which are in a phosphorylated state before interacting with the ligand–GPCR–G

protein complex [141, 143]. It is important to note that dephosphorylation of

-arrestins is not necessary for -arrestin-mediated GPCR

desensitization that occurs upon receptor association with -arrestins,

since this process depends primarily on the pattern of -arrestin

isoforms and their relationship with receptors and other components of signal

transduction.

-Arrestin-mediated GPCR desensitization is due to the interaction of

-arrestin with receptor sites that, after hormonal activation, are

phosphorylated either by GPCR-specific kinases (GRK, homologous desensitization)

or by low-specific PKA and PKC (heterologous desensitization). However, in the

cytoplasmic regions of GPCRs, as a rule, there are several target sites for

phosphorylation by protein kinases, and the phosphorylation pattern depends on

many factors. Among them are the structural features of the active, hormone-bound

conformation of the receptor, the ability of the receptor to form homo- or

hetero-oligomeric complexes, the type and ratio of heterotrimeric G proteins

interacting with the receptor, as well as the type of protein kinases acting on

the receptor, including various isoforms of GRKs, the action of which on GPCR

sites, targets for phosphorylation, is characterized by high specificity. The

GPCR phosphorylation pattern is, in a certain sense, a “phosphocode” that

determines further signaling events involving -arrestins. Thus, the

“phosphocode” programs the internalization and subsequent degradation or

recycling of GPCRs, or favors the formation of a signalosome comprising the

GPCR--arrestin complex and the initiation of -arrestin-mediated

signaling cascades.

Among the effector components of the MAPK cascade, the main target of

-arrestins is protein kinases of the ERK-family [141, 144, 145] (Fig. 3), and various mechanisms of their activation are possible. According to one of

them, -arrestins act as scaffold proteins that ensure colocalization and

coordinated functioning of components of the MAPK cascade, such as protein

kinases Raf1, MEK1 and ERK1/2 [145, 146], and arr1 and arr2

differ in their influence on the activity of this cascade [141, 147]. Along with

this, there is evidence of the ability of -arrestins, mainly

arr1, through other mechanisms to directly activate Raf kinase, an

upstream component of the MAPK cascade [148], and a downstream effector protein,

the proto-oncogenic kinase Src [149]. The binding of arr1 to c-Raf

kinase occurs in its Ras-binding domain, since in the presence of the small

GTPase H-Ras, which also stimulates the activity of c-Raf kinase, the binding of

the enzyme to -arrestin is inhibited [148]. It has been established that

-arrestins can stimulate the activity of other members of the MAPK

cascade, such as p38-MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, but no direct interaction

between them has been detected [150, 151].

A study of the molecular mechanisms of -arrestin involvement in

GPCR-mediated signal transduction using genetically modified cells lacking

certain types of G proteins showed that -arrestin signaling, including

that mediating the activation of the MAPK cascade, requires the presence of

functionally active heterotrimeric G proteins, at least in small quantities

[152]. It is believed that the functions of -arrestins consist of fine

regulation and modulation of MAPK activity, which is based on their

allosterically determined influence on the functional interaction of the

hormone-activated receptor complex, including G proteins, with protein kinases

ERK1/2 [153, 154]. Thus, the question of the independence of -arrestin

signaling from G proteins has not been fully resolved, and the discussion here,

most likely, should be about the coordinated interaction of G proteins and

-arrestins within the signalosome at the post-receptor stages of signal

transduction.

5. Regulatory Effects of hCG and LH on Intracellular Signaling

Cascades: Similarities and Differences

5.1 Stimulating Effects of LH and hCG on cAMP-Dependent Signaling

Pathways

Back in the early 1990s, it was shown that both hormones, LH and hCG, despite

their inherent structural differences, including different glycosylation

patterns, are capable of stimulating the activity of membrane-bound AC isoforms

and increasing the level of cAMP in frog oocytes and in cultured intestinal

L-cells that express mouse LHCGR [155, 156]. Gonadotropins also stimulated the

phospholipase cascade and caused the mobilization of calcium ions from

intracellular stores. Both processes were to a certain extent independent of each

other, which indicated the absence of significant interaction between signaling

cascades realized through heterotrimeric G and G proteins, which

are transducers between hormone-activated LHCGR and the effector proteins, AC and

PLC respectively [155, 156]. An increase in cAMP levels and a sharp rise

in intracellular Ca concentration after activation of LHCGR by

gonadotropins occurred quite quickly, on average one minute after exposure,

indicating similar kinetics of these processes [11, 157]. Back in 1996, it was

suggested that G proteins, with which ligand-activated LHCGR is also able

to interact, may be involved both in the negative regulation of AC activity after

its G-mediated stimulation by gonadotropin (short negative feedback) and

also act as donors G dimer involved in the activation of

PLC2 and PLC3, responsible for the regulation of calcium

signaling and stimulation of various isoforms of PKC [158] (Fig. 3).

The half-maximal concentration (EC) for stimulation of AC activity and

increase in intracellular cAMP levels by gonadotropins are in the picomolar range

of their concentrations, while nanomolar concentrations of LH and hCG are

required to trigger -arrestin (arr2)-mediated internalization

of LHCGR [11]. Along with this, it was established that to achieve the maximum

stimulating effect of gonadotropins on cAMP-dependent cascades, occupancy of no

more than 10% of LHCGR is sufficient, while for effective translocation of

-arrestins to the ligand-receptor complex and its further

internalization, the degree of occupancy of LHCGR should have exceeded 90% [11].

Activation of AC by gonadotropins with LH activity leads to an increase in the

level of phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB and stimulation of

CREB-dependent expression of the gene encoding the cholesterol-transporting

Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory protein (StAR), which catalyzes the first,

rate-limiting stage of steroidogenesis, as demonstrated in Leydig cells [12].

Thus, the mechanisms of the influence of LH and hCG on AC activity and

cAMP-dependent intracellular targets are characterized by a certain similarity.

At the same time, the effectiveness of such influence varies quite significantly

[10, 12, 14].

Most of the data obtained using cell cultures demonstrate a higher potential of

hCG, compared to LH, regarding the activation of the AC system and downstream

effector units (PKA) (Table 2). In cultured COS-7 cells expressing LHCGR, the

ED value for the stimulatory effect of hCG on cAMP production was shown to

be 107 14 pmol/L, while the corresponding value for LH was five times

higher at 530 51 pmol/L [9]. When using hCG, the maximum stimulating

effect on intracellular cAMP levels was achieved one hour or more after

treatment, while when using LH this occurred faster, after 10 min [9]. The

efficiency of increasing cAMP levels in HEK-293 cells with LHCGR expressed in

them when exposed to hCG was significantly higher than when exposed to LH, and

the EC value for hCG was 213 pmol/L and was significantly lower than that

for LH (426 pmol/L), with the maximum response for both gonadotropins being

achieved at a concentration of about 10 nmol/L [17]. The differences in the

effectiveness of LH and hCG were greatest in ovarian granulosa cells [14].

Treatment of a primary culture of human granulosa cells (hGLC) for 36 hours with

hCG caused a more pronounced and time-sustained increase in cAMP levels compared

to treatment with recombinant LH taken at an equivalent dose. As a result, in the

culture treated with hCG, progesterone production was significantly higher than

in the control and in the culture treated with LH, indicating a more pronounced

stimulation of ovarian steroidogenesis caused by hCG [9].

Table 2.

Comparison of the effects of luteinizing hormone (LH) and human

chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) on adenylyl cyclase activity and cyclic adenosine

monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent pathways—similarities and differences.

| Similarities |

| Both gonadotropins in picomolar concentrations stimulate the gonadotropin–LHCGR–G protein–AC–cAMP–PKA/EPAC1/2 system, resulting in stimulation of the activity of cAMP-dependent transcription factors, including CREB, and stimulation of steroidogenesis and other cAMP-dependent processes. |

| Gonadotropins exert their effects with high efficiency both in ovarian cells (theca and granulosa cells) and in testicular Leydig cells. |

| Differences |

| (1) The stimulating effect of hCG on AC and cAMP production is achieved at lower concentrations and is more stable over time than that of LH, and this difference is specific to certain cell types and is most pronounced in granulosa cells, where the AC stimulating effect of LH is weakly expressed. The result is a more pronounced stimulatory effect of hCG at the early stages of steroidogenesis, despite the fact that at the later stages of steroidogenesis the effects of the hormones become comparable. |

| (2) The stimulatory effect of hCG on the activity of ERK1/2, an effector component of the MAPK cascade, realized via cAMP-dependent pathways and PKA is more pronounced than that of LH. This, along with differences in the influence of LH and hCG on the expression of proteins that regulate apoptosis, determines that hCG preferentially activates pro-apoptotic cascades, and LH anti-apoptotic cascades. |

| (3) LH and hCG have different effects on cAMP-dependent cascades during heterodimerization of LHCGR with FSHR. In the case of hCG, there is a potentiation of the AC stimulating effect, and in the case of LH this effect does not change significantly. |

Note: AC, adenylate cyclase; CREB, cAMP-dependent transcription factor (cAMP

Response Element-Binding protein); EPAC1/2, Exchange Protein directly activated

by Cyclic AMP, types 1 and 2; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinases,

types 1 and 2, the effector components of mitogen-activated protein kinase

cascade; FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; LHCGR, luteinizing

hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor; MAPKs, mitogen-activated protein

kinases; PKA, protein kinase A.

Similar results were obtained with long-term treatment of cultured goat ovarian

granulosa cells with gonadotropins, where hCG increased the intracellular level

of cAMP and activated PKA with significantly greater efficiency than LH [159].

The stimulating effect of hCG on cAMP levels and cAMP-dependent phosphorylation

of ERK1/2 during treatment of primary Leydig cell culture also significantly

exceeded the corresponding effects of LH, in the case of stimulation of

intracellular cAMP production by almost 10 times [12]. The higher potential of

recombinant hCG for AC activation, compared with recombinant LH, was demonstrated

in mouse Leydig tumor cells (mLTC-1), in which mouse LHCGR was expressed, as well

as in HEK273 cells expressing human LHCGR [13]. This indicates that the

peculiarities of obtaining recombinant forms of gonadotropins do not

significantly affect the higher potential for stimulation of the AC system

detected in the case of hCG, since both urinary and recombinant hCG were equally

superior to LH.

It should be noted, however, that cAMP level-dependent indicators such as the

degree of phosphorylation of the CREB factor and the expression of the gene for

the steroidogenic protein StAR in cultures of Leydig cells and HEK273 cells

treated with hCG and LH did not differ significantly [12, 14]. This may be due to

counter-regulatory influences that are triggered in the target cell with a

long-term and sustained increase in cAMP concentration, among which an increase

in the activity of cAMP-specific PDEs plays a significant role. It is also

interesting that progesterone production in different cell types treated with hCG

was significantly higher than with LH treatment, while testosterone levels varied

slightly [13]. Laura Riccetti et al . [13] explain this disappearance of

differences in the testosterone levels by the fact that in the case of exposure

to LH, the synthesis of testosterone is carried out to a greater extent by the

pathway that includes 17-hydroxyprogesterone as an intermediate instead of

progesterone (the so-called 5-pathway), while hCG ensures the synthesis

of large quantities of progesterone, which functions as a “parallel accumulation

product” and then largely enters the less efficient 4 pathway of

androgen synthesis. The result of this is a leveling off of testosterone

production induced by both gonadotropins during later stages of testicular

steroidogenesis, despite significantly greater amounts of progesterone

accumulating in hCG-treated cells [13].

A study of the effects of hCG and LH (100 pmol/L) in human granulosa-lutein

cells revealed that hCG not only stimulates phosphorylation of the factor CREB

and increases the expression of the StAR protein gene with greater efficiency

compared to LH, but also enhances proapoptotic cascades to a greater extent

[160]. The proapoptotic effect of hCG was strongly attenuated in the presence of

physiological doses of -estradiol (200 pg/mL), as illustrated by

increased activity of the anti-apoptotic enzyme Akt kinase, assessed by its

Ser phosphorylation, and inhibition of the cleavage of procaspase-3, a

key component of the apoptotic pathway, leading to increased cell survival. With

regard to the expression of the aromatase (cytochrome CYP19A1) gene, the

situation is the opposite, and the stimulating effect of LH 72 hours after

treatment exceeded that of hCG. This causes an increase in aromatase activity and

stimulates the conversion of androgens into estrogens, which are necessary to

maintain the growth of follicles and oocytes and increase the survival of

granulosa-luteal cells [160]. LH also more effectively, compared to hCG,

increased the expression of genes encoding the anti-apoptotic protein XIAP

(X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein) and cyclin D2, thereby exerting a

pronounced anti-apoptotic effect [160]. This indicates that LH-stimulated

cAMP-dependent pathways are characterized by a greater anti-apoptotic potential,

while the corresponding hCG-activated pathways are primarily triggers of

proapoptotic cascades, although the resulting effect of gonadotropins on

apoptosis is thought to depend on from many factors and counter-regulatory

influences (Table 2).

Since testing for LH and hCG is carried out in both human and rodent cell lines

and uses gonadotropins from different sources, it is important to evaluate the

possible species-specific effects of their effects on cAMP-dependent pathways.

With various combinations of gonadotropins and target cells, their primary

effect, which consists of activation of the AC signaling system, in the case of

hCG, as a rule, significantly exceeds that of LH, and this is due to differences

in the efficiency of interaction of the ligand (LH or hCG) with the LHCGR

ectodomain and the peculiarities of conformational changes caused in the TMD and

the LHCGR–G protein interface due to such interaction [12, 13, 14, 160, 161, 162].

However, at later, effector, stages of hormonal signal implementation, at the

stage of phosphorylation of the factor CREB and the final stages of

steroidogenesis, the differences in the effectiveness of LH and hCG begin to

weaken and, ultimately, may disappear altogether. It should be noted, however,

that this applies most to the stimulation of testicular steroidogenesis, while in

follicular cells the differences between LH and hCG tend to persist into the

later, effector stages of gonadotropin signaling [12]. To a certain extent, the

equivalence of LH and hCG in terms of stimulation of testicular steroidogenesis

is important for the treatment of androgen deficiency and hypogonadotropic

hypogonadism in men with gonadotropins. Thus, there is an observation that

treatment of a man with central hypogonadism sequentially with LH and hCG

normalized his blood testosterone level to the same extent [163].

An important point is that the AC-stimulating effects of hCG and LH may be

modulated differently in the presence of FSH. This is due to both the

heterodi(oligo)merization of LHCGR and the structurally similar FSHR, which

changes the efficiency and pattern of their activation by gonadotropins, and the

cross-interaction of intracellular signaling cascades activated by FSH and

gonadotropins with LH activity inside the target cell. Under the in

vitro conditions using human granulosa-luteal cells, it was shown that in the

presence of FSH, the ability of hCG to enhance the production of intracellular

cAMP increases on average five times, which entails increased phosphorylation of

the factor CREB and the steroidogenic response to hCG [164]. In this case, the AC

stimulating effect of recombinant LH in the presence of FSH does not change

significantly, as a result of which treatment of cells with a combination of

recombinant LH and FSH does not lead to a significant increase in the level of

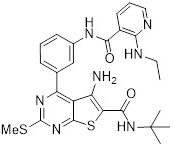

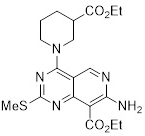

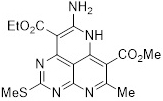

CREB phosphorylation and the production of steroid hormones (Table 2).