1 Department of Immunology, Medical Faculty, First Saint Petersburg State I. Pavlov Medical University, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

2 Department of Immunology, Institute of Experimental Medicine, 197376 Saint Petersburg, Russia

3 Laboratory of Immunology, Saint Petersburg Pasteur Institute, 197101 Saint Petersburg, Russia

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

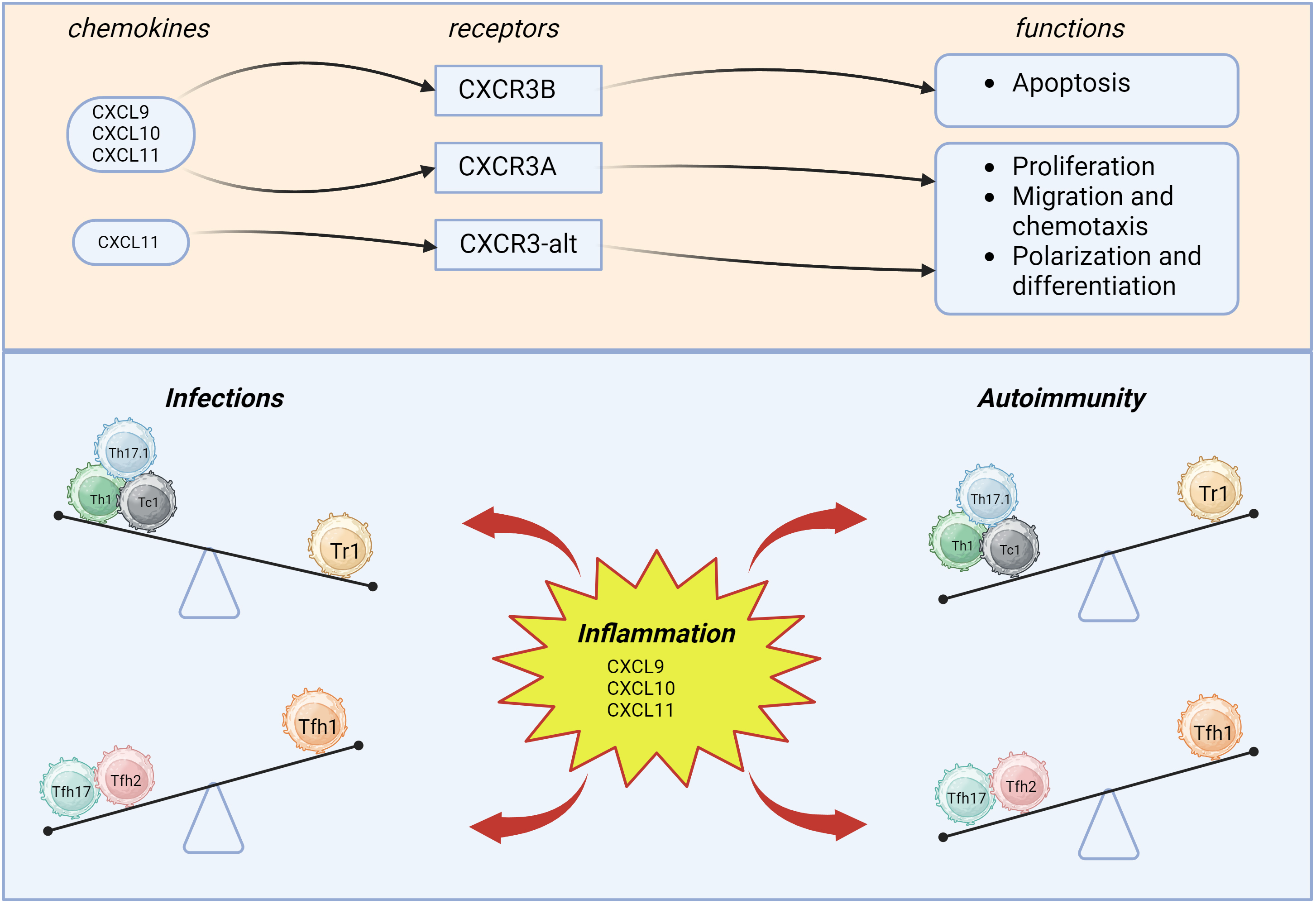

The chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligands (MIG/CXCL9, IP-10/CXCL10, and I-TAC/CXCL11) play a central role in the generation of cellular inflammation, both in the protective responses to invading pathogens, and in different pathological conditions associated with autoimmunity. It is worth noting that CXCR3 is highly expressed on innate and adaptive lymphocytes, as well as on various cell subsets that are localized in non-immune organs and tissues. Our review focuses exclusively on CXCR3-expressing T cells, including Th1, Th17.1, Tfh17, Tfh17.1, CXCR3+ Treg cells, and Tc1 CD8+ T cells. Currently, numerous studies have highlighted the role of CXCR3-dependent interactions in the coordination of inflammation in the peripheral tissues, both to increase recruitment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that upregulate inflammation, and also for recruitment of CXCR3+ T regulatory cells to dampen overexuberant responses. Understanding the role of CXCR3 and its ligands might help to apply them as new and effective therapeutic targets in a wide range of diseases.

Keywords

- CXCR3 receptor

- CXCR3 chemokines

- Th1 cells

- Th17.1 cells

- follicular Th cell subsets

- CXCR3+ Treg

- Tc1

- infection

- COVID-19

- autoimmunity

In 1996, the human chemokine receptor CXCR3 was discovered [1]. Two years later,

the relevant gene was found on chromosome Xq13.1 [2]. The CXCR3 receptor

is a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-family serpentine transmembrane protein classified as a CXC-type

receptor based on the structure of its cognate ligands. This receptor was

initially discovered on activated T cells selectively binding ELR-negative CXC

chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 [1]. It was found that the percentage of

CXCR3-expressing T cells exposed in vitro to Interleukin (IL)-2 and phytohemagglutinin

increased by up to 95% [2]. Accordingly, T cell activation promotes CXCR3 ligand

sensitivity. It was revealed that the transcription factor T-bet driving

differentiation of ‘naïve’ T cells into Th1 and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells

directly promotes the expression of CXCR3 [3, 4, 5]. In addition, transcription

factor T-bet induces Interferon (IFN)

After two more alternative splice variants CXCR3B and

CXCR3-alt of the CXCR3 gene were discovered, CXCR3 receptor was

named CXCR3A. CXCR3A consisting of 368 amino acids is the most common form that

interacts with cognate ligands CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 to trigger chemotaxis and

intracellular calcium mobilization. CXCL11 and CXCL10 induce activation of the

inhibitory G

Existence of two distinct CXCR3 variants potentially exerting opposing effects may account for angiostatic effect assigned to CXCR3 ligands. Moreover, a third alternative splice variant for CXCR3 was identified that results from exon skipping and called CXCR3-alt [15]. CXCR3-alt consists of 267 amino acids, showing marked structural and functional differences, containing only four or five transmembrane domains, however, this receptor variant, like CXCR3A, interacts with Gi-protein. Interestingly, CXCR3-alt isoform is able to bind solely CXCL11 to trigger moderately elevated intracellular calcium level and chemotaxis [16].

CXCR3 ligands exhibit diverse biological effects by acting on various

CXCR3-expressing cell types [17]. The presence or absence of the Glu-Leu-Arg

(ELR) motif before the first cysteine residue within the amino acid composition

of CXC chemokines accounts for downstream potential to stimulate or inhibit

angiogenesis. CXCR3-binding CXC chemokines bear no the ELR motif and act,

therefore, as angiogenesis inhibitors [18]. Thus, CXCR3 ligands comprise a

distinct group of angiostatic chemokines. Among them, two subgroups can be

described: (i) key CXCR3 ligands – IFN

The most common ligands for CXCR3 include CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11. All three

chemokines are encoded on chromosome 4. And their prodiction can be induced by

IFN

Besides the various domains of CXCR3 required for the functional activity of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 individually, there are receptor domains that are required for the functioning of three chemokines combined. For instance, the DRY site in the third transmembrance domain of the CXCR3 receptor is required for CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11-mediated cellular chemotaxis, calcium recruitment, and ERK phosphorylation [28].

The chemokines CXCL10, CXCL0, and CXCL11 can participate in T cell polarization.

For instance, CXCL10 and CXCL9 cause expression of T-bet and ROR

Although all three chemokines are able to chemoattract activated T cells [2],

CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 can contribute to the migration of CXCR3-expressing

cells. For instance,

It is worth mentioning that CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 have different patterns of expression by various cell types [38]. Flier et al. [39] showed differential expression of CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 in different skin diseases. The authors demonstrated expression of CXCL10 and CXCL11 mostly in basal keratynocytes, whereas expression of CXCL9 was localized mostly in derma infiltrates [39]. Other studies demonstrated that in chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis, alveolar macrophages mostly secreted CXCL10 and not CXCL9 or CXCL11 [40]. CXCL9, however, was associated with the macrophage activation syndrome seen in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [41]. In some pathologies, the three chemokines are not interchangeable. For instance, in experimental models of dengue fever, the loss of CXCL10 activity was not compensated for by CXCL9 or CXCL11 [42, 43].

Therefore, besides obvious similarities, CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 hold some spatiotemporal and functional differences. Spaciotemporal differences include the production of CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 by different cells of different localizations at different timespans, depending on the pathological process. Therefore, the abovementioned chemokines cannot substitute for each other in every pathology. Functional differences are caused not only by different types of CXCR3, but also by interactions of CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL9 with different receptor domains. The functionality of these chemokines can also depend on CXC3R-expressing cells.

When analyzing CXCR3 surface expression of T helpers, Kim et al. [44]

found this chemokine receptor expressed on nearly 3% of ‘naïve’

CD45RA+CD45RO–CD4+ T cells, and on 41.5

CXCR3+ comprise around 50–90% of CD8+ T cells [47, 48, 49, 50]. Our own data

has shown that among naïve CD8+ T cells, CXCR3+ percentage

comprised 80.67

A decrease in CXCR3+ cells when transitioning into mature effector cells was described by Brainard et al. [47]. Besides circulating CM, EM and TEMRA T cells, CXCR3 expression can be found in tissue-resident memory cells (tissue-resident memory (TRM), CD69+CD103+), a special population of T cells that permanently resides in peripheral tissues (e.g., lungs, skin, intestine, etc.) [51], and such positioning at the site of inflammation allows for them to rapidly respond to invading pathogens, as has been recently shown in M. tuberculosis infection [52].

As for CXCR3 expression on naïve T cells, it can be associated with stem-like memory T cells (TSCM) in circulation [53]. In murine models, CD8+T cell transplant to secondary recipient was followed by increased development of graft vs host-like reactions. Murine TSCM phenotype was described as CD44lowCD62Lhigh, which matched surface markers of naïve murine T cells. However, surface antigens included Sca-1 molecule (stem cell antigen-1), usually seen on stem cells. Besides, these cells showed high levels of B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) expression, and expressed surface receptor CXCR3. Subsequent studies showed a similar T cell population in the peripherial human blood; it held CD45RO–CCD7+CD45RA+CD62L+CD27+CD28+CD127+ phenotype, usually seen in naïve cells, but they also had surface CD95, CD122, CXC3, and Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) [54].

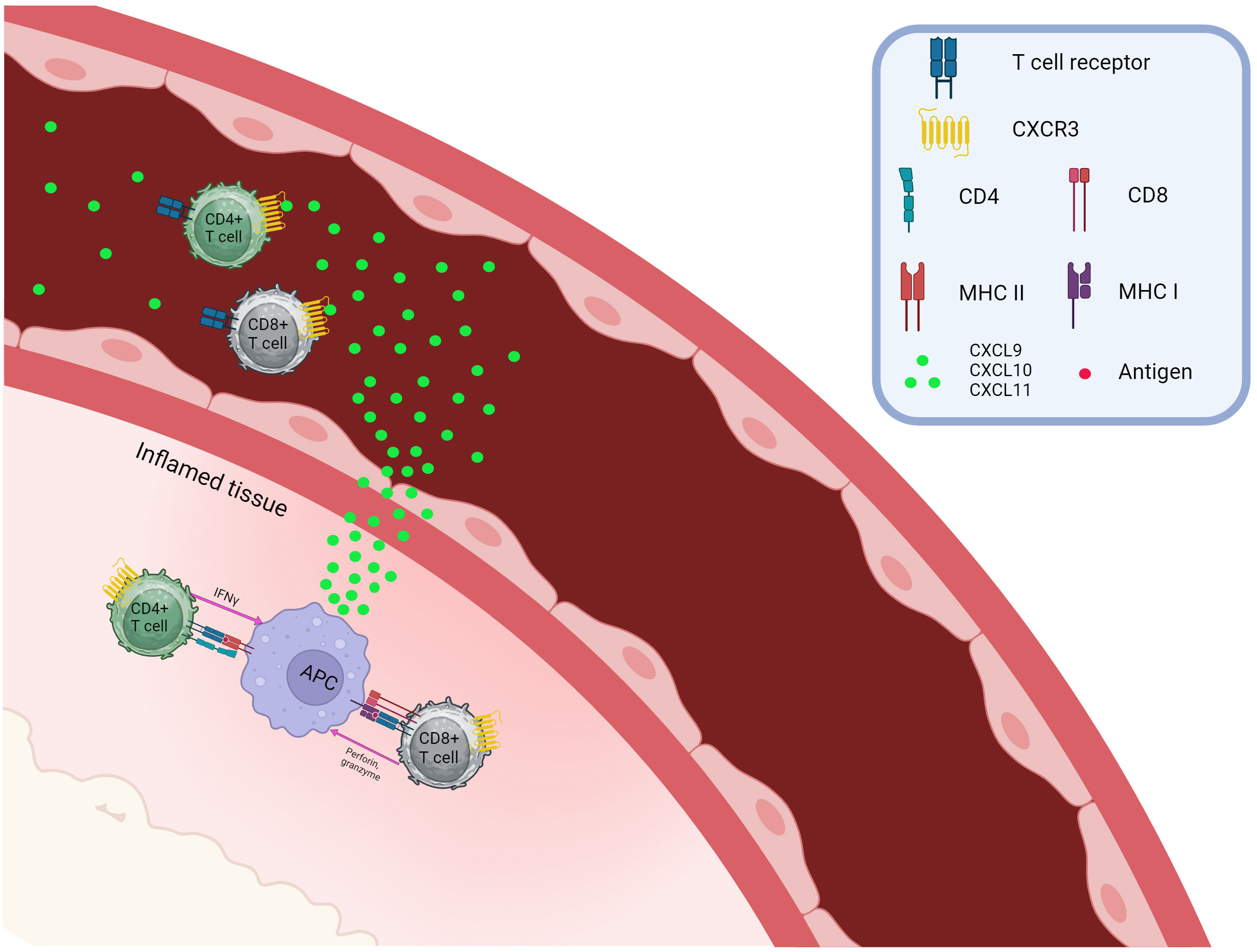

Fig. 1 demonstrates the chemoattraction of CXCR3+CD4+, and CXCR3+CD8+ T cells. Th1, Th17.1, Tc1, and Tr1 are able to migrate into the inflammatory site based on concentrations of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, where, after interacting with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and inflamed tissue cells, they provide their effector functions.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemotaxis of CXCR3-positive T cells. CXCR, C-X-C chemokine receptor; CXCL, C-X-C Ligand; CD, Cluster of Differentiation; APC, Antigen presenting cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex. Created with BioRender.com.

The studies mentioned above highlighted a crucial role played by CXCR3 in

migration of Th1 and Tc1 CD8+ T cells to the site of inflammation in peripheral

tissues during type 1 reactions as well as underlie a feedback loop mediated by

lymphocyte produced IFN

In the absence of pro-inflammatory signals, the key CXCR3 ligands CXCL9, CXCL10,

and CXCL11 are found at very low levels in the bloodstream and peripheral

tissues. At the initial stage of the inflammatory process, their levels increase

in the inflammation site, so that IFN

| CXCL9 | CXCL10 | CXCL11 | References | |

| TB | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [55] |

| COVID-19 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61] |

| HIV | ↑ | [62] | ||

| HCV | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [63, 64] |

| MS (blood) | ↑ | ↑ | [68, 69] | |

| MS (liquor) | ↑ | ↑ | [65, 66, 67, 68] | |

| RA (blood) | ↑ | ↑ | [70, 71] | |

| RA (synovial fluid) | ↑ | ↑ | [72, 73] | |

| T1D | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [74, 75, 76, 77] |

| SLE | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [78, 79, 80, 81] |

| pSS | ↑ | ↑ | [82, 83] | |

| AS | ↑ | ↑ | [84, 85] | |

| IBD | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [86, 87] |

| Sarcoidosis (blood and BALF) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [88, 89, 90] |

| Psoriasis (blood and skin) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [39, 91] |

| Graves’ disease | ↑ | [92, 93] |

TB, tuberculosis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MS, multiple sclerosis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; T1D, type 1 diabetes; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; pSS, Primary Sjögren’s syndrome; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ↓ indicates decreased levels of circulating cells, ↑ signifies increased levels.

High serum levels for all three CXCR3 ligands were observed in tuberculosis (TB) [55], so that for CXCL9, it correlated with systemic organ involvement, whereas CXCL10 levels strongly correlated with respiratory outcomes [94, 95]. During M. tuberculosis infection, high levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10 were observed in active pulmonary and latent TB infections [96], whereas effective therapy was paralleled with lowered levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10 [97].

A high serum CXCL10 level was strongly associated with severe COVID-19 [56, 57, 58]. Moreover, COVID-19 patients with abruptly elevated serum CXCL9 and CXCL10 levels are more likely to result in an unfavorable outcome compared to patients with severe and mild COVID-19 [59]. Finally, computer tomography-verified pneumonia lung injury positively correlated with CXCL10 level [98]. Along with this, elevated levels for all three CXCR3 ligands were found in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples collected from patients with acute COVID-19 [60, 61].

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection during antiretroviral therapy (ART) was associated with a consistently high CXCL10 level being an important predictor of low therapeutic effectiveness [62], and, in contrast to CD4+ T cell level or viral load, CXCL10 concentration serves as an earlier predictor of disease progression [99]. Moreover, the levels of all three chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 inversely correlated with those of ‘naïve’ circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but positively correlated with the level of peripheral blood Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)–DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells, whereas increased CXCL9 and CXCL11 levels were closely associated with higher viral load. Also, plasma levels of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in primary HIV-1 infection served as crucial markers for the long-term prognosis of HIV disease [100].

Plasma CXCL10 levels were significantly higher in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients with advanced fibrosis, which were also strongly associated with extrahepatic manifestations, including active vasculitis in HCV-associated cryoglobulinemia and autoimmune thyroiditis [63]. It should also be highlighted that CXCL10 level is positively correlated with liver fibrosis score and liver enzyme concentration [101]. Moreover, baseline serum concentrations of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 were higher in HCV infection compared to the control group, with a peak level observed for CXCL10, but after successful therapy, those for CXCL10 and CXCL9 decreased significantly, whereas for CXCL11 they remained elevated [64]. A study by Arsent’eva et al. [102] also noted increased serum levels of CXCL9/Monokine induced gamma interferon (MIG), CXCL10/Interferon gamma-induced protein (IP)-10, and CXCL11/ITAC in chronic HCV infection, whereas liver biopsies contained higher CXCL10 mRNA levels closely associated with developing fibrosis.

A rise in the level of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) CXCR3 ligands in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) may be closely related to the recruitment of CXCR3+T cells from peripheral blood into the nervous tissue, which plays an important role in developing inflammation and the formation of tertiary lymphoid strictures in the central nervous system (CNS). For instance, an increased level of CSF CXCL9 was noted in multiple sclerosis compared to the control group [65]. Moreover, serum CXCL9 levels were correlated with clinical parameters such as the number and volume of brain and spinal cord lesions [66]. Patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) vs. secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) were found to have an increased concentration of CSF CXCL10 that also correlated with CXCR3+ T helper cell level [67]. It was also shown that IP-10 concentration was elevated in both serum and CSF in RRMS and SPMS but not in primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) [68]. A rise in serum CXCL11 level was noted in relapsing-remitting MS compared to the control group [69], although another study found that it remained unaltered [103].

Patients with early-onset and long-term rheumatoid arthritis (RA) vs. control group had elevated serum CXCL9 and CXCL10 levels [70, 71], which decreased during effective therapy [70, 104]. Importantly, CXCL10 level was tightly related to RA clinical picture and correlated with multiple disease activity measures, including Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), swollen joint counts (SJC), tender joint counts (TJC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [71]. In turn, higher level of multiple chemokines regulating various aspects of cell functioning at the site of inflammation was noted in the synovial fluid [5, 105, 106]. In particular, levels of synovial fluid (SF) CXCL9 and CXCL10 were also increased in RA [72, 73, 107], exceeding those for serum counterparts [108]. The data on CXCL11 are quite controversial. For example, Ueno et al. [73] showed that serum and SF CXCL11 levels differed insignificantly [94], whereas Aldridge et al. [108] found lower SF vs. serum CXCL11 (I-TAC) level.

Patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) showed elevated serum CXCL10 levels [74], whereas in another study, CXCL9 levels, rather than CXCL10 [75] levels, decreased. Increased CXCL9 concentration was also confirmed in the work of Hakimizadeh et al. [76]. Powell et al. [77] observed elevated levels of CXCL10 and CXCL11 in newly diagnosed individuals and those with long-standing diabetes compared to the control group, whereas CXCL9 levels showed no statistical differences between groups.

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had a lowered CXCL9 level that

correlated with the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) score, while atorvastatin

therapy was associated with a progressive serum decline for CXCL9 [78]. Along

with this, a high plasma CXCL10 level was observed in SLE that additionally

correlated with disease activity, anti-DNA antibody level, and SLEDAI score [79, 80]. Furthermore, serum CXCL11 levels in SLE patients also exceeded those in the

control group but decreased during Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)

Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) was associated with a higher serum CXCL9 level compared to the control range and was correlated with IgG concentration as well as the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Sjogren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) score [82]. In addition, elevated serum CXCL10 levels were also associated with disease activity [83]. However, the serum CXCL11 level was unchanged; it correlated with that of CXCL9 and CXCL10 [110]. Apart from this, it was uncovered that during inflammation, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 were produced in tear fluid, also involving corneal and conjunctival epithelium in dry eye syndrome [111]. Noticeably, CXCL11 level correlated with various parameters of the lacrimal film and eye surface, such as basal tear secretion, tear clearance rate, keratoepitheliopathy score, and goblet cell density.

In patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) vs. the control group, serum CXCL9 levels were found to rise [84]. Moreover, it was also noted that newly diagnosed AS patients contained higher CXCL10 concentrations that correlated with Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), CRP, and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), whereas therapy applied decreased CXCL10 levels [85]. However, some studies reported that AS patients had serum CXCL11 levels unchanged [112]. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, were found to have higher level for all three chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 [86, 87] that was further corroborated in animal model [87].

Patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis had increased serum CXCL9 and CXCL10 levels compared to the control group [88]. Moreover, CXCL10 was also accumulated in granulomas, which is believed to mirror its important role in granuloma formation [89]. It was also shown that CXCL9 was stronger correlated with systemic organ involvement, whereas CXCL10 was more predictive for lung outcomes [94]. Also, high levels of all three CXCR3 ligands were observed in BALF samples [90].

Assessing the serum concentration of CXCR3 ligands CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in patients with psoriasis is important not only for understanding the disease pathogenesis but also to represent promising targets for evaluating therapeutic effectiveness [113]. For instance, serum CXCL9 level was increased in psoriasis vs. control group [91]. Moreover, elevated CXCL9 expression was associated with a high risk of developing psoriasis [114]. However, opposite results were obtained by Lima et al. [115], failing to note a change in CXCL9 and CXCL10 levels and detecting no relation between them and clinical data. In situ production of CXCL10 and CXCL11 at the site of inflammation is mainly performed by keratinocytes, whereas CXCL9 is primarily released by dermis-infiltrating cells [39].

CXCR3 ligands play an essential role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid lesions [116]. CXCL10 levels were increased in newly diagnosed patients with Graves’ disease compared to the control group, whereas histology examination revealed that expression of IP-10/CXCL10 and MIG/CXCL9 was predominantly associated with lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrating thyroid gland tissue and resident epithelial follicular cells [92]. Moreover, CXCL10 levels remained elevated even in remission [93].

The majority of the pathological events described above were paralleled with

increased levels of CXCR3 ligands in both the serum samples and at the site of

inflammation. CXCR3 ligands were produced not only by blood cells infiltrating

inflamed tissues, but also by resident tissue cells. Apparently, the initial

entry of CXCR3+ T cells into the site of inflammation is accompanied by

their activation followed by the by the production of proinflammatory cytokines,

including IFN

As was previously described, it is CXCR3 ligands that form the microenvironment required for cellular attraction in type I inflammation. Moreover, effective CXC3+ involvement in inflammatory sites will determine the efficacy of pathogen elimination in infectious diseases and autoimmune inflammation. Therefore, one of the main goals of our review was to analyze the functions and dynamics behind CXCR3+ T cells in different populations and how CXC3 ligands make them accumulate and interact during inflammation.

Th1 cells are characterized as

CD3+CD4+CXCR5–CXCR3+CCR6–CCR4– cells [117] able

to secrete IFN

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and conventional dendritic cells (cDC1), IL-12, and IFN

It was observed that the N- and S-proteins of Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) stimulated the

production of IFN

Patients with active pulmonary TB were shown to have increased level of peripheral blood CD4+CXCR3hi cells able to rapidly secrete cytokines in response to diverse M. tuberculosis antigens [139]. M. Tuberculosis (MTB)-specific Th1 cells might be able to migrate into foci of infection. Nikitina et al. [140] noticed that dominant lung CD4+ T cells in active pulmonary tuberculosis mimicked CXCR3+CCR6– population. On the other hand, highly expressed CXCR3 and its cognate ligands CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11 were also demonstrated in tuberculosis granuloma [141, 142]. Moreover, increased CXCR3+ central memory (CM) and CXCR3+ EM T cell levels were observed in BALF vs. peripheral blood paired samples from TB patients [143]. Hence, Th1 cells in TB contribute to granuloma formation and restrain spreading of infectious process.

Chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its IP-10 ligand are considered as markers to assess the size of the HIV cell reservoir [144, 145]. CXCR3 and IP-10 are more often found in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) than in peripheral blood in chronically simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected primates, CXCR3 and IP-10 are more often found in GALT than in peripheral blood [145] that was related to HIV reservoir size. CXCR3 is predominantly expressed in Th1 cells that together with CCR6 defines a CD4+ T-cell subset mainly enriched with HIV DNA in ART-treated HIV-infected subjects [146]. Serum IP-10 level in HIV-positive patients is increased while CXCR3 becomes activated in memory CD4+ T cells [147, 148]. In particular, chemokines such as IP-10 acting on resting CD4+ T cells ensure effective HIV-1 nuclear localization and HIV-1 provirus integration [149]. Thus, CXCR3/IP-10 axis can stimulate HIV-1 replication in periphery and mucous membranes and, therefore, chronic activation of host immunity. In addition, the HIV replication-competent viruses were mainly found in peripheral blood CXCR3-expressing CD4+ T cells in HIV+ patients [150], whereas serum IP-10 level correlate with blood and semen virus reservoir size [145, 151]. CXCR3 and IP-10 stimulating the HIV-targeted T cells to migrate into the focus of inflammation in peripheral tissues are abundantly produced in the small intestine and stimulate HIV replication in vitro [146]. Moreover, it was shown that CXCR3/IP-10-blocking monoclonal antibody lowers in vitro HIV-1 replication. Furthermore, Augustin et al. [152] assessed a role for CXCR3 and IP-10 in GALT in HIV-infected individuals. Although a percentage of peripheral blood CD4+ T cells was similar in peripheral blood, terminal ileum and rectum, HIV and CXCR3 DNA expression was markedly elevated, whereas IP-10 level was downmodulated in the ilium compared to serum samples. No significant correlation between CXCR3 expression and memory CD4+ T cell subsets, IP-10 and HIV DNA levels measured in the blood, terminal ilium and rectum was observed. Thus, neither CXCR3 nor IP-10 level in chronic HIV-1 infection point at GALT HIV reservoir size [152].

Patients with HCV were found to have elevated CD3+CD4+CXCR3+ and CD3+CD4+CCR6+ Th cell levels, particularly showing that the percentage of CXCR3+ Th cells (CD3+CD4+CXCR3+) was increased, although it was solely observed for CD3+CD4+CXCR3+CCR6+ cells [153]. Furthermore, the majority of liver-derived T cells expressed CXCR3 chemokine receptors, representing high enrichment over levels of CXCR3+ T cells in blood from patients with HCV [154].

Th1 cells exert multifaceted effects in development of autoimmune diseases. In this regard, Th1 cells may trigger induction of inflammation or antagonize autoreactive cells in a context-dependent manner. Autoreactive Th1 cells are considered as the major T cell subset promoting development of autoimmune inflammation in a wide range of autoimmune disease before Th17 and Th17.1 cells were identified.

In multiple sclerosis, Th1 cell function remains controversial because some studies report that these cells migrate across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and participate in developing autoimmune inflammation [155, 156], whereas others demonstrate that they provide immunosurveillance, but Th17.1 cells display an autoimmune phenotype [157]. Taking into consideration recent discoveries in the autoimmune mechanism of multiple sclerosis, it may be concluded that it is Th17.1 cells that are mainly involved in this pathology. However, studies conducted in the 2000s suggested a role for the CXCR3 receptor in T cell migration across the BBB [156, 158, 159]. Hence, it implies that CXCR3-positive Th1 cells may enter brain tissue and maintain autoimmune inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Moreover, Sørensen et al. [156] demonstrated CXCR3+ T cell accumulation during multiple sclerosis lesion formation, whereas Nakajima et al. [160] showed increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) CXCR3–expressing CD4+ T cell level in patients with multiple sclerosis as well as a higher percentage of peripheral blood CD4+CXCR3+ cells in recurrent multiple sclerosis. Thus, despite the fact that Th17.1 cells are crucial to nerve tissue damage in multiple sclerosis, Th1 level may be a prognostic factor for the disease course.

In rheumatoid arthritis, the level of peripheral blood CD4+CXCR3+ T

cells was decreased [161], whereas in SF and the synovium it tended to increase

[108, 161]. The data presented above suggests Th1 migration to affected joints in

rheumatoid arthritis. Presumably, IFN

In type 1 diabetes, peripheral blood Th1 (CD4+CXCR3+) cell levels were

decreased if compared to healthy donors [164, 165], and their frequencies were

affected by the disease’s clinical manifestation. In particular, patients with

fulminant onset of T1D had decreased CXCR3-expressing CD4+ T cells if

compared to typical and healthy subjects, while patients with a typical pattern

of T1D onset had significantly higher levels of Th1 cells than healthy controls

and patients with fulminant onset of T1D [165]. It is plausible that Th1 cells

may migrate into the pancreas and take part in pancreatic beta cell lysis. Uno

et al. [166] showed that pancreatic beta cells from T1D patients

selectively express the CXCL10 ligand for the CXCR3 receptor. Moreover, beta

cell-positive regions in the pancreatic islets were infiltrated with

CD3+CXCR3+ lymphocytes [166], thereby supporting the hypothesis about

selective destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Blahnik et al. [167]

described beta cell-specific CXCR3+CCR7–T cells in T1D patients,

suggesting a Th1-like effector phenotype. Assessing peripheral blood Th1 cell

subset composition in T1D may be prognostic based on the data reported by Aso

et al. [168], who revealed that T1D duration was positively correlated

with IFN

In diffuse connective tissue diseases (DCTDs), the role of Th1 cells was also assessed. For instance, patients with SLE were found to have peripheral blood Th1 and Th17 cell subsets with high IL-21 expression levels, suggesting that they may provide help to B cells [169]. In addition, a rise in CD4+CXCR3+ T cell level was associated with disease severity, showing that active vs. remission patients with SLE and healthy subjects had significantly higher levels of CXCR3– and CCR5–expressing CD4+ T cells [170, 171]. Such a T cell subset plays a role in SLE-related kidney damage, so Enghard et al. [172] revealed that around 50% of kidney CD4+ T cells were CXCR3 positive, and CD4+CXCR3+ T cell levels also mirrored lupus nephritis activity.

In the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome, Th1 cells are involved in damaging target organs. In this regard, lung biopsies were noted to be enriched in Th1 cells within the area of fibrosis, whereas in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a similar sign was not observed [173]. In contrast, the level of peripheral blood Th1 cells was decreased in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome [174]. In dermatomyositis, musculocutaneous flap biopsies showed mononuclear cells predominantly with a CD4+CXCR3+ phenotype, whereas skin biopsies in discoid SLE usually lacked CXCR3–positive cells [175].

Few studies were aimed at analyzing the role of Th1 cells in the pathogenesis of systemic vasculitis. For instance, Lintermans et al. [176] demonstrated a decline in peripheral blood effector memory (EM) Th1 cell level in Wegener’s granulomatosis. On the contrary, other studies demonstrated elevated peripheral blood CD4+CXCR3+ T cell percentages in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive vasculitis [177]. Hence, a role for Th1 cells in systemic vasculitis remains unclear and requires further exploration.

The percentage of Th1 cells was significantly increased in mild and severe AS

compared with control subjects, whereas that of Th2 cells remained affected

insignificantly [178]. Moreover, the Th1/Th2 cell ratio was markedly higher in

mild and severe ankylosing spondylitis patients. Th17 cell levels were also

significantly increased in mild and severe ankylosing spondylitis, whereas

inter-group Treg cell percentages did not differ. Therefore, Th17/Treg cells are

prominently higher in mild and severe ankylosing spondylitis. Assessing

expression for key cytokines typical of “polarized” Th cells revealed a

significantly increased level of IFN

Patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) had decreased peripheral blood CD4+CXCR3+ T cell levels [182]. However, an immunohistochemistry study assessing foci of inflammation showed that this cell type was enriched in the inflamed mucosa of IBD patients. Papadakis et al. [183] showed that CXCR3 is expressed on the majority of gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. An in-depth study analyzing lymphocytic infiltrate in CD intestinal mucosa revealed that CCR6 and CXCR3 were co-expressed on CD4+ T cells [184], allowing to assign them to the Th17.1 phenotype. It is also known that Crohn’s disease is characterized by altered immune tolerance to commensal bacteria. For instance, Cook et al. [185] assessed the flagellin-specific responses of diverse Th cell subsets isolated from CD patients and found that FliC- and Fla2-specific CD4+ T cells were dominated by Th17 and Th17.1 rather than Th1 cells. Thus, a key role in emerging granulomatous inflammation in Crohn’s disease is related not only to Th1 cells but also to Th17.1 cells.

In pulmonary sarcoidosis, circulating CD4+CXCR3+ T cell levels were significantly decreased compared to healthy controls [186]. Th1 cells are among those essential cells involved in the development of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions and granuloma formation typical for sarcoidosis. Such data suggest that Th1 cells migrate to the site of inflammation. The study by Facco et al. [187] showed high infiltration of CD4+CXCR3+ T cells into the lungs during pulmonary sarcoidosis, corroborating our assumption. Also, patients with chronic sarcoidosis had an increased level of BALF CD4+CXCR3+ T cells [188]. After BALF and peripheral blood cells obtained from patients with sarcoidosis and volunteers were stimulated with phorbol ester and ionomycin, types 1 and 2 Th cells and CTL levels were analyzed for cytokine secretion. It was found that Tc1 and Tc2 secretory potentials in both biological materials did not significantly differ between patients and control subjects. In contrast, BALF Th1 cell cytokine production (post-stimulation) was higher in patients with sarcoidosis. On the other hand, while comparing BALF Th1 with Th2 cells collected from volunteers, it was shown that the former was a priori more abundant under normal conditions [189]. Thus, it may be concluded that Th1 cells are involved in emerging granulomatous inflammation during chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Regarding psoriasis, it was revealed that CCR6–CCR4+CXCR3+ memory Th cell levels tend to decline [190]. Similar findings may also mirror partial antigenic stimulation of autoreactive Th1 cell clones. Flier et al. [39] CXCR3 was expressed by the majority of psoriasis skin-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, suggesting a functional interplay between locally produced chemokines and CXCR3-expressing T cells. The latter may become recruited into the skin layers upon disease exacerbation. Furthermore, Flier et al. [39] showed that CXCR3 was expressed by the majority of psoriasis skin-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, suggesting a functional interplay between locally produced chemokines and CXCR3-expressing T cells. Diani et al. [191] also noted that effector CXCR3+CD4+ T cells were selectively recruited to the skin compartment during psoriasis. Furthermore, CXCR3+ T cell accumulation in the joint tissue of patients with psoriatic arthritis was followed by an increase in CXCL10 levels in SF [50].

Patients with coexisting Graves’ disease and T1D had decreased peripheral blood Th1 cell levels compared with the control and patient’s groups with either disease alone [168]. Moreover, normal thyroid tissue virtually lacked expression of IP-10/CXCL10, MIG/CXCL9, and CXCR3, whereas the onset of the inflammatory process in patients with Graves’ disease was paralleled with their abruptly elevated level, which may cause Th1 cell infiltration into inflamed tissue [92]. A high CXCL10 level was also observed in active Graves’ ophthalmopathy [192]. Elevated serum CXCL9 and CXCL11 levels were also related to active first-onset Graves’ disease and recurrent hyperthyroiditis, whereas efficient therapeutic intervention downmodulated their production [192].

Patients with myasthenia gravis vs. healthy subjects showed decreased levels of circulating CXCR3+CD4+ T cells as well as inverse correlation between the level of these cells and disease severity according to the MGFA scale, whereas therapeutic intervention gradually restored level of these cells to control range [193].

Therefore, in infections caused by intracellular pathogens (e.g., viruses or M. tuberculosis), CXCR3-expressing Th1 cells have an important role in the induction of the infectious process and the activation of effector cells via key cytokine production. At the same time, long-term activation of Th1 cells (increase in expression of activation surface markers, excessive cytokine production, and accumulation of cells in inflammation cytote) is followed by damage to surrounding cells of the host, leading to defects in the functioning of inflamed organs and, potentially, to the progression of autoimmune diseases.

Thus, despite the long-standing discovery of the Th1 cell subset, their role in autoimmune diseases continues to raise questions. In connection with recent research, other cells expressing CXCR3 such as Th17.1 cell subset come to the fore while exploring development of autoimmune granulomatous diseases. The essential role for Th17.1 cell subset was also noted in organ-specific diseases such as multiple sclerosis. However, Th1 cells still play a dominant role among other CXCR3+ T lymphocytes in some autoimmune diseases, e.g., type 1 diabetes.

Th17 cells and the pro-inflammatory cytokines they produce play an essential role in regulating type 3 inflammation [194] aimed at elimination of extracellular bacteria and fungi. Such inflammation is characterized by influx of circulating neutrophils into inflamed tissues as well as activation of barrier tissue cells (primarily mucosal epithelial cells) along with elevated mucus production and antimicrobial factor release [195]. Currently, Th17 cells are divided into several separate subpopulations based on CCR4 and CXCR3 co-expression by distinguishing “classical” CCR4+CXCR3–, “double-positive” CCR4+CXCR3+, “non-classical” Th17.1 CCR4–CXCR3+, as well as “double-negative” CCR4–CXCR3– cells [196]. “Classical” Th17 cells consist of two major cell types solely bearing surface CCR6 or co-expressing CCR6 and CCR4 markers [197], able to abundantly produce IL-17A in response to stimulation, whereas the remaining cytokines, primarily IL-22 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), they produce at much lower level are less pronounced in them. Proliferative potential of such cells in vitro co-cultured with autological Tregs becomes inhibited much less profoundly compared to Th1 and Th2 cells evidencing that they are poorly sensitive to action of anti -inflammatory cytokines [198].

The population of “non-classical” Th17 – Th1/Th17 or Th17.1 – bearing Th1

and Th17 cell features including expression of the nuclear factors TBX21 and RORC

and potential to produce IFN

Two more new Th17 cell subsets were also characterized: CCR4–CXCR3–

(“double negative” or CCR6+DN) and CCR4+CXCR3+ (“double

positive” or CCR6+DP), which fundamentally differed in related functional

features from the previously described Th17 cells [201]. For instance,

CCR6+DN vs. “classical” Th17 cells expressed more IFN

For instance, CCR6+DN Th17 cells were characterized by a high mRNA level

for molecules driving migration into lymphoid tissue (CCR7, CXCR5, CXCL13, SELL,

SIRP1, JAM3, and AIF1). On the contrary, CCR6+DP Th17 cells expressed mainly

adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors necessary for migration into inflamed

intestinal tissues (

Peripheral blood CM and EM Th17.1 cell levels in acute COVID-19 are lowered

compared to control groups [131, 202]. It is also associated with an increased

CXCR3 ligand, IP-10 [131]. These data suggest that during acute COVID-19, Th17.1

cells migrate to the site of inflammation. After recovery, peripheral blood

Th17.1 cell levels returned to the control ranges [132]. The depletion of Th17.1

may be due to both the SARS-CoV-2-triggered hyperactivated immune response and

impaired T-helper cell polarization in the secondary lymphoid organs occurring

during acute infection. It is plausible that Th17 cells migrate to the site of

inflammation with varying efficacy at different stages of the infectious process.

Therefore, the data assessing BALF samples are crucial because they indicate Th17

cell accumulation with a pro-inflammatory phenotype in the affected lung tissues

[203]. In particular, such Th17 cells had a tissue-resident memory T cell

phenotype by expressing the genes associated with cytolytic properties (SRGN,

GZMB, and GNLY) and those for the cytokines IL-21, IL-17F, IL-17A, IFN

Previously, it was noted that Th17.1 cells play a hallmark role in the formation of noncaseating granulomas during autoimmune pathologies. In this regard, they were also analyzed for M. tuberculosis-caused infections. It is known that this pathology is associated with caseous granulomas formed in various organs. While analyzing peripheral blood Th cell subset composition in TB-infection in vitro nonspecific stimulation, it was shown that the level of circulating CD4+IL-17A+ cells declined, whereas levels of CD4+IL-4+ T cells significantly increased [205]. For instance, Wang et al. [206] found in active TB patients vs. control subjects a higher IL-17+CD4+ T cell level in the circulation that corroborated earlier data showing an increased IL-17 mRNA level in peripheral blood lymphocytes [207]. On the other hand, two independent research groups revealed a decline in peripheral blood Th17 cell levels in TB patients [208, 209]. We also found that the circulating Th17.1 cell level was decreased, whereas that of “classical” and CCR6+DP Th17 cells was significantly increased in patients compared to the control group [210].

To better understand the role of Th17.1 cells in pulmonary tuberculosis,

Mtb-specific CD4+ T cell responses were assessed in numerous studies of

latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and active pulmonary tuberculosis. The study

by Nikitina et al. [140] showed that IFN

In HIV infection, CCR6+CCR4+ Th17 and CCR6+CXCR3+ Th17.1 cells exert pathogenic effects because they carry in vivo integrated HIV DNA, and their levels are significantly lowered in HIV-infected individuals, including those with undetectable plasma viral load during antiretroviral therapy [215]. Similar data were obtained by El Hed et al. [216], showing a decreased total Th17 cell count during HIV infection. Moreover, depletion of Th17 and Th17.1 cells in the GALT may be a major cause of microbial translocation, chronic immune activation, and the emergence of non-AIDS-related comorbidities in HIV-infected individuals [217]. Moreover, altered Th17 cell composition in HIV infection is suggested by the data that CCR6+DN is the most predominant Th17 cell subset in the peripheral blood and lymph nodes of ART-treated HIV-infected individuals, and it is these cells that carry integrated HIV viral DNA [201].

Patients with HCV infection are characterized by a lowered Th17 cell level in

the circulation [218], although these data remain controversial [219]. Of note,

binding to human sinusoidal endothelium was dependent on

It should be noted that Th17.1 cells play a critical role in the pathogenesis of

multiple sclerosis associated with significantly increased peripheral blood

levels, with such cells co-producing IL-17 and IFN

Interestingly, the level of peripheral blood Th17.1 cells is decreased in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis [226]. In addition, synovial fluid in RA vs. osteoarthritis patients had a low level of such cells but an increased concentration of CXCR3 ligands (CXCL9 and CXCL10) that was associated with a high infiltration of CXCR3-expressing cells found in immunohistochemistry examination [72]. Thus, it is plausible that during RA, Th17.1 cells migrate to the site of inflammation from the circulation and participate in the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures in joints. As noted by some studies, Th17 cells in RA are able to acquire the Th17.1 phenotype at the site of inflammation due to the high level of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12 [227, 228]. To support these data, Jimeno et al. [229] showed a pathogenic profile for memory Th17 and Th17.1 cells in RA. Baseline peripheral blood Th17.1 cell level in patients with RA may serve as a predictor for response to Abatacept therapy. It should be emphasized that the surface of Th17.1 cells highly expresses the surface MDR-1 protein P-glycoprotein, which accounts for blocking the response to immunosuppressive therapy [199, 230]. The percentage of baseline Th17.1 cells but not other Th cell subsets in Abatacept responders vs. non-responders was significantly decreased [230]. Also, Th17.1 levels were closely associated with disease activity. RA activity assessed according to the DAS28 scale is inversely correlated with peripheral blood Th17.1 cell level [230]. It is likely that RA Th17.1 cells are involved in autoantibody production. Paulissen et al. [231] showed that patients with CCP Ab-positive vs. CCP Ab-negative RA had higher surface expression of Th cell CCR6 and CXCR3. Thus, Th17.1 cells in rheumatoid arthritis can be a predictor of response to immunosuppressive therapy and also affect disease course [232].

Indirectly, Th17.1 cells were also noted to play a role in T1D. Marwaha et al. [233] demonstrated that Ustekinumab (an anti-IL-17A antibody) in T1D reduced C-peptide and peripheral blood Th17.1 cell levels, which, along with the Th1 subset, may be involved in the lysis of pancreatic beta cells.

On the other hand, Th17.1 cells are also found to exert pathological effects in

DCTDs. Thus, patients with SLE were observed to have an increased peripheral

blood Th17.1 cell level that was inversely correlated with serum complement

component C4 concentration [234]. Th17.1 cells may be involved in the

pathogenesis of anti-DNA antibody formation. Zhong et al. [235] reported

that anti-DNA+ patients with SLE have a higher percentage of CCR6 and

CXCR3–expressing Th cells, including the Th17.1 subset. A rise in

peripheral blood Th17.1 cell percentage was also observed in Sjögren’s

disease [236]. Presumably, this Th cell subset migrates to the site of autoimmune

inflammation. Salivary gland IHC from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome

demonstrates higher infiltration of IFN

In systemic vasculitis, a role for Th17.1 cells was not thoroughly investigated; however, many studies report that its level changed. For instance, Takayasu’s arteritis is associated with a higher peripheral blood Th17.1 cell count [239]. Singh et al. [239] also observed that they decreased after immunosuppressive therapy based on tacrolimus or metatrexate together with corticosteroids. Furthermore, Th17.1 cell level is also altered in ANCA-positive vasculitis, e.g., in Wegener’s granulomatosis, characterized by its decline in peripheral blood EM Th17.1 cell subset [176]. In addition, Liao et al. [177] showed an inverse relation between peripheral blood Th17.1 cell level and CRP concentration, as well as a higher risk of poor renal outcomes in ANCA-positive vasculitis.

The percentage of both IL-17- and IL-22-positive Th cells found in patients with

AS was higher than in the healthy control group but did not significantly affect

the level of IFN

Currently, only a few studies have analyzed the Th17 cell subset composition in

patients with various IBD forms. For instance, it was shown that in IBD,

circulating Th cells capable of specifically recognizing antigens derived from

intestinal microbiota-derived bacterial cells usually secrete IL-17A,

IFN

In sarcoidosis, Th17.1 cells are involved in the formation and maintenance of granulomatous inflammation in the affected organs. Also, they can serve as a prognostic factor, mirroring disease chronicity. A rise in peripheral blood and BALF Th17 cell levels in patients with Löfgren’s syndrome was a predictor for the resolution of the acute process without sarcoidosis chronicity [248]. Furthermore, Lazareva et al. [249] noted that the frequency of peripheral blood DP Th17 was significantly increased in patients with chronic and Löfgren’s syndrome vs. the control group, while “non-classical” Th17.1 was shown to have a significantly reduced level only in chronic sarcoidosis vs.healthy subjects. However, Th17 cells migrating to the site of inflammation can transform into the Th17.1 phenotype, which promotes granuloma formation and sustained chronic inflammation. For instance, BALF Th17.1 cell level was higher in patients with chronic disease than in patients with disease resolved within a 2-year clinical follow-up [250]. A immunohistochemistry examination revealed a higher Th17.1 level both in the sarcoid granuloma center and periphery [251, 252], reflecting their possible role in autoimmune inflammation. Examining peripheral blood in patients with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis reveals both a rise [252] and a decline [253] in CD4+CCR6+CXCR3+ T cell levels. Despite this, Th17.1 cells in patients with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis migrate to the site of inflammation, which agrees with recent studies. Moreover, Ramstein J et al. [254] showed that a higher Th17.1 cell level is found in mediastinal lymph nodes and BALF vs. peripheral blood in chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thus, Th17.1 cells in chronic sarcoidosis migrate to the site of inflammation, promote granuloma formation via macrophage chemotaxis and activation [251], and serve as a negative predictor of disease course. At the same time, some studies report a favorable disease prognosis and granuloma resolution upon increased T-bet+RORgT+CD4+ T cell levels in the BALF of patients with Löfgren’s syndrome [255]. However, T-bet+RORgT+CD4+ T cells may represent transitional Th17.0 cells acting as Th17.1 precursors yet lacking CXCR3 expression [256].

It should be noted that the Th17.1 subset plays an important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis because it promotes keratinocyte apoptosis and proliferation in skin lesions [257]. Also, Th17.1 correlates with disease severity [258]. Tsiogkas et al. [259] showed an increased content of CD3+CD4+CXCR3+ T cells and CXCR3 expression among the CD3+CD4+CCR6+CCR4– and CD3+CD4+CCR6+CCR4+ lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of patients with psoriasis. The elevated levels of these cells in the circulation may be due to high antigenic stimulation occurring in peripheral lymphoid organs. Next, they migrate into the dermis, as evidenced by Lowes et al. [260]. Moreover, Tsiogkas et al. [259] showed that anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibodies downmodulate Th17 (CD3+CD4+CCR6+), Th1 (CD3+CD4+CXCR3+), and Th17.1 (CD3+CD4+CCR6+CCR4–CXCR3+) cell frequencies as well as CXCR3 expression on CD4+CCR6+CCR4+ and CD4+CCR6+CCR4+ cell types in patients with psoriasis 3 months post-treatment. Thus, similar to systemic autoimmune pathologies, Th17.1 cells are also directly involved in autoimmune skin disorders.

In infections, the role of Th17.1 requires further investigation. However, the data, although controversial, hints at the protective role of these cells. Th17.1 also forms a memory phenotype and acquires cytolytic activity against intracellular pathogens. This feature might reflect their positive impact on infectious diseases, although it is followed by the attraction of neutrophils and the death of the host’s cells. In autoimmunity, we see the same controversy concerning Th17.1 dynamics. It happens due to the technical disparities when analyzing these cells, a lack of standardization in methodology, and a shortage of accessible data on the topic.

In autoimmune diseases, Th17.1 cells exhibit a wide range of pathogenic functions and are able to migrate to sequestered organs, initiate and maintain autoimmune inflammation, and contribute to disease progression. Moreover, the Th17.1 cell phenotype often underlies resistance to immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune pathologies.

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells play an essential role in B cell maturation and

differentiation during the germinal center reaction in peripheral lymphoid organs

[261, 262]. These cells control antibody class switching, triggering somatic

hypermutations, and selecting high-affinity B cell clones, which subsequently

differentiate into plasma cells and memory cells. At present, Tfh cells

circulating in the peripheral blood are considered a heterogeneous population

that may be subdivided into several independent lineages based on the

co-expressed chemokine receptors CCR6 and CXCR3, as well as the presence of

various transcription factors typical of polarized Th cell subsets [263]. For

instance, Th1-like Tfh or Tfh1 cells bear solely surface CXCR3 along with the

transcription factor T-bet, whereas Th2-like Tfh or Tfh2 cells lack both of the

above-noted chemokine receptors but express transcription factor GATA3 at a high

level. And finally, Th17-like Tfh or Tfh17 cells display the

CXCR3–CCR6+ROR

Using experimental animal models allowed us to show that IFN

Patients during acute COVID-19 were found to have an imbalanced ratio between peripheral blood CXCR3+CCR6–Tfh1 cells due to a decreased percentage of regulatory Tfh1 and an increased level of pro-inflammatory Tfh17 cells [202]. COVID-19 convalescent patients had circulating virus S-protein-specific CD45RA–CXCR5+ Tfh cells along with an extremely low percentage of RBD-specific Tfh cells [271]. Moreover, the vast majority of SARS-CoV-2-specific Tfh cells belonged to the CCR6+CXCR3– Tfh17 subset, and only a few of them had the Tfh1 phenotype (CCR6–CXCR3+). A high count of cTfh1 and cTfh2 cells was positively correlated with high serum neutralizing activity in COVID-19 convalescent patients [271]. At the same time, after acute COVID-19, a change in peripheral blood Tfh cell subset composition was observed, which could persist long-term. Interestingly, COVID-19 convalescents might have elevated Tfh levels within several months after recovery, which was closely related to a higher percentage of Tfh2 and Tfh17 cells [272]. Similar data was obtained by Similar results were obtained by Gong et al. [135], who noted an increase in the proportion of CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh1 and CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh2 cells compared to the control, while the level of CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh17 was significantly reduced. The high activity of Tfh1 cells in COVID-19 convalescents may contribute to the initiation of chronic autoimmune inflammation [273].

Recently published data revealed that lymph node germinal center (GC-Tfh) Tfh

cells are reservoirs for HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). The number

of GC-Tfh cells increases during chronic HIV and SIV infection [274, 275, 276], which

is considered a highly favorable prognostic parameter of the HIV and SIV

infection course [277, 278]. In addition, it was shown that productive SIV

infection occurs in resident intrafollicular CD4+ Tfh cells in the lymph

node B-cell follicles of SIV-infected elite controller rhesus macaques [279] and

is protected from cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. It was hypothesized that latent

infection is established in circulating memory CD4+ T cells when they pass

through a chemokine-rich environment such as lymph nodes [149, 280]. Using

activation-induced marker assays, Niessl et al. [281] assessed CXCR3 and

CCR6 expression on activation-induced Ag-specific cTfh cells in Antiretroviral therapy (ART)-treated

individuals. HIV– and CMV– specific cTfh cells were dominated by

Th1-like (CXCR3+CCR6–) phenotype cells, whereas HBV-specific cTfh

cells showed a mixed cTfh profile with Th2-like (CXCR3–CCR6–) and

Th1-like polarization. However, a large percentage of Ag-specific CXCR3+

cTfh cells also produce the Tfh cell cytokines CXCL13 and IL-21. Altogether, a

co-expression assay revealed a higher CXCL13 and IL-21 level, along with Tfh cell

cytokines and IFN

It was shown that HCV infection is accompanied by cTfh cells skewed towards

differentiation of CXCR3+ cTfh cells highly expressing Tfh-associated

molecules, including Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), Inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS), IL-21, and Bcl-6, compared to CXCR3– cTfh

cells [282]. Along with this, the level of circulating CXCR3+ cTfh cells

positively correlated with HCV titers and nAbs. Moreover, cTfh cells and

autologous memory B cells co-cultured in vitro showed that CXCR3+vs. CXCR3– cTfh cells promoted clonal expansion of HCV E2-specific

B cells from HCV-infected individuals. Such data suggest that HCV infection

promotes cTfh cell expansion and skews cTfh cells toward CXCR3+ cTfh cell

differentiation, which aligns with the study showing that the majority of MHC II

tetramer-positive antigen-specific CD4+ T cells express CXCR3 and exhibit

properties similar to Tfh cells during acute infection with HCV [283]. It should

be noted that the presence of activated ICOS+CXCR3+ Tfh cells is

closely related to effective antibody production and the successful resolution of

HCV infection [284]. Also, in chronic HCV infection, the level of peripheral

blood Tfh1 (IFN

Patients with relapsing and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis were characterized by a lowered percentage of Th1-like Tfh cells, whereas in PPMS it was increased [286]. Another study showed that the Tfh subset cell composition in RRMS undergoes profound change related to a decreased percentage of Tfh2 cells and an increase in the proportion of Tfh17.1 cells among total CD45RA–CXCR5+ Th cells [287]. It should also be emphasized that the percentages of Tfh1 and Tfh17 cells in MS patients and the comparison group did not significantly differ, which may suggest a pro-inflammatory shift in Tfh cell polarization. The use of the first-line drug dimethyl furamate was accompanied by gradually increased Tfh2 along with decreased Tfh1 and pathogenic Tfh17.1 cells in the total Tfh cell population. It should also be noted that dimethyl furamate was able to reduce both serum IgA, IgG2, and IgG3 levels as well as memory IgD–CD27+ B cell levels, which underwent antibody class switching. Choileáin et al. [288] noted in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) a higher percentage of cTfh1 (CXCR5+CXCR3+CCR6–) cells, but that of cTfh1-Tfh17 (CXCR5+CXCR3+CCR6+) and cTfh17 (CXCR5+CXCR3–CCR6+) cells remained unaltered. Moreover, Haque et al. [289] showed that the percentage of CXCR3–CCR6+ Tfh17 and CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh17.1 within CXCR5+PD1+ Th cells in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients increased compared to control subjects. On the other hand, Tfh17.1 cells were dominated by in vitro IL-21 production, so the level of IL-21+ Tfh17.1 cells in MS patients exceeded that in the control group. Finally, CSF from patients with MS was characterized by increased levels of CXCR3+CCR6+ cTfh1 and CXCR3+CCR6+ cTfh17.1 cells [290]. Thus, these data suggest that Tfh17.1 cells may represent one of the crucial arms in MS pathogenesis, although more detailed studies regarding their role in the formation of autoreactive B cell clones and foci of tertiary lymphoid tissue in MS are required.

While analyzing Th cell subset composition from patients with rheumatoid

arthritis, it was shown that patients with high (DAS28

An experimental model of type 1 diabetes mellitus revealed that pancreatic CXCR3+CCR6–Tfh1 but not CXCR3–CCR6+ Tfh2 and CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh17 cell levels were higher in SAP–/–/NOD vs. Wild type/Non-obese diabetic (WT/NOD) mice [297]. On the other hand, no significant change in CXCR5+ T cells expressing different CXCR3 and/or CCR6 patterns was observed in T1D patients vs. the control group [298].

On the contrary, patients with active SLE (SLEDAI score

In Sjögren’s syndrome, the level of peripheral blood CD4+CXCR5+ T cells becomes elevated compared to the control group [304]. This was primarily due to the higher percentage of circulating Tfh cells displaying the CXCR5+CCR6+ phenotype, considered a distinct cell population called Tfh17. Moreover, a direct correlation between increased Tfh17 levels and clinical signs such as the level of immunoglobulins, anti-Ro/anti–Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A autoantibodies (SSA), anti-La/anti–Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen B autoantibodies (SSB), and EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) disease activity index (ESSDAI) scores was found. The percentage of CXCR3–CCR6– (Tfh2) and CXCR3–CCR6+ (Tfh17) tended to rise in parallel with the decreasing level of CXCR3+CCR6–(Tfh1) Tfh cells noted by Kim et al. [305], although no significant differences were identified as compared with the control group. Another study revealed no significant differences while analyzing the levels of CXCR3+CCR6– Tfh1, CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh1/17, CXCR3–CCR6– Tfh2, and CXCR3–CCR6+ Tfh17 cells in Sjögren’s syndrome vs. control subjects [306]. Similar data were also obtained in an experimental mouse model of Sjögren’s disease (NOD/ShiLtJ mice), demonstrating an increased level of Tfh cells (CD4+CXCR5+PD1+), whereas for individual splenic subpopulations such as Tfh1, Tfh2, and Tfh17, their level did not change significantly compared to the control group [307]. At the same time, CD4+CXCR5+ Tfh cell clusters were found in affected salivary glands [308], whereas upregulated expression of Tfh-associated molecules (Bcl-6, IL-21, and CXCR5) was closely associated with disease progression [309].

Before the onset of therapy, patients with ankylosing spondylitis had a higher level of CD4+CXCR5+CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh1 cells, whereas the percentage of CD4+CXCR5+CXCR3+CCR6+ Tfh17 lymphocytes was decreased compared to the control group; no inter-group differences were found in Tfh2 cell level [310]. On the other hand, Yang et al. [311] revealed in patients with AS a decline in the percentage of CXCR3+CCR4+CXCR5+ Tfh1 cells along with an elevated level of CXCR3+CCR4+CXCR5+CCR6+ Tfh17. Our personal studies uncovered that the central memory CXCR5+CD45RA–CD62L+ Th population contained a lower level of Tfh1 cells in parallel with a higher percentage of Tfh2 and Tfh17 cells, and an imbalance between these cell types was associated both with Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) exacerbation and remission [312].

Similar changes manifested as a decreased level of peripheral blood CXCR3–CCR6+ Tfh17 cells and a rise in the percentage of CXCR3–CCR6– Tfh2 cells were described in ulcerative colitis [313]. Regarding Crohn’s disease, a single relevant work is currently available showing that peripheral blood Tfh1- and Tfh17-like cell levels displaying the phenotypes CXCR3+CCR6– and CXCR3+CCR6+ (although recently, such cells are commonly called Tfh17.1-like lymphocytes) were increased relative to the control group, whereas that of Tfh2-like cells (CXCR3–CCR6–) did not differ significantly from control subjects [314]. Hence, in some autoimmune diseases, not only changes in Tfh subset composition may be observed, but they may be related to the clinical picture and severity of pathological processes.

Patients with IgG4-related disease contained a higher percentage of Tfh2 cells compared to control subjects and patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome [315, 316]. Moreover, a high positive relation was also revealed between circulating Tfh2 cell level and IgG4 concentration as well as IgG4:IgG ratio, and a relationship between Tfh2 cell percentage and level of peripheral blood circulating CD19+CD20–CD27+CD38+ plasma cell precursors as well as IL-4 level were also shown. Similar data were obtained by Grados et al. [317], who noticed that the rise in circulating CD4+CXCR5+PD1+ Tfh cells was primarily associated with a higher percentage of Tfh2 as well as Tfh17 cells. Another study noted an increased percentage of Tfh1 and Tfh17 cells in patients with active disease compared to control subjects, so that the level of Tfh1 cells was positively correlated not only with IgG4 concentration but also with disease activity according to the IgG4-related disease (RD) responder index (RI) scale scores [318].

Patients with sarcoidosis examined by us revealed an increased level of circulating CXCR3–CCR6– Tfh2 cells, whereas the percentage of CXCR3+CCR6–CCR4– Tfh1 and CXCR3+CCR6+CCR4– Tfh17.1 cells was significantly reduced relative to the control range [319]. Moreover, an altered Tfh1/Tfh2/Tfh17 cell balance was noted not only in peripheral blood but also in the BALF samples from patients with sarcoidosis [320, 321]. A marked role for diverse Tfh cell subsets was also indicated by identifying them in lung lesions [322].

The prevalence of peripheral blood Tfh17 cells in psoriasis patients was significantly increased along with Tfh2 and Tfh1 cell percentages that tended to increase and decrease, respectively [323, 324]. Moreover, the level of Tfh17 cells positively correlated with the volume of skin layer lesions, psoriasis area, and severity index (PASI). In response to therapy that alleviates psoriasis symptoms, the percentage of circulating Tfh17 cells also decreased. Similar data were obtained by Liu et al. [325], who showed a higher percentage of circulating Tfh17 cells with the PD-1+CXCR5+ phenotype that also correlated with disease severity and serum CXCL13 level. These data indicate a crucial role of Tfh cells as well as the CXCL13/CXCR5 axis in psoriasis pathogenesis and can also be considered a promising therapeutic target. Patients with Graves’ disease were found to have a significantly increased level of Tfh2 cells (CXCR3–CCR6–) compared to the control group, whereas for Tfh1 (CXCR3+CCR6–) and Tfh17 (CXCR3–CCR6+) cells, it was decreased in total CD4+ T cells [326]. Patients with myasthenia gravis were found to have circulating Tfh2 and Tfh17 cells at significantly higher levels than in the control group, whereas the percentage of Tfh1 cells that remained intact did not differ from the control [327]. A rise in peripheral blood Tfh17 but not in Tfh1 and Tfh2 cells was also observed in patients with MuSK-antibody-positive myasthenia gravis [328]. Yang et al. [329] also reported that patients with myasthenia gravis have high levels of peripheral blood Tfh17 vs. other Tfh cell subsets, which also highly express ICOS, PD-1, and IL-21, suggesting their activation. Moreover, the level of cTfh-Th17 cells correlated with that of plasma cell precursors and anti-acetylcholine receptor (anti-AChR) antibodies. A type of Guillain-Barré syndrome called acute motor axon neuropathy was noted to be associated with an increased level of circulating Tfh cells [330]. Such patients had a higher absolute count of the major Tfh subsets, such as Tfh1, Tfh2, and Tfh17, that exceeded not only its magnitude in the control group but also that found in acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Apart from this, such patients had an increased percentage of Tfh2 and Tfh17 cells compared with the above-noted groups, whereas Tfh1 cell levels did not differ significantly.

Follicular T cells and their subpopulations are quite new; therefore, our understanding of their bilogy and function is limited. At the same time, we can presume that there is a balance between pro-inflammatory CXCR3+ Tfh1 cells and anti-inflammatory Tfh2 and Tfh17 cells. This balance is crucial for the effective functioning of the humoral part of antigen-specific immunity. For effective responses against intracellular pathogens, it is important to have high levels of Tfh1 circulating cells; this allows them to migrate throughout the lymphoid tissues and regulate the functions of antigen-specific B cells in regional lymph nodes and lymphoid nodules in the gut.

In autoimmune diseases, an imbalance between Tfh cells can be associated with autoantibody production. Moreover, in some cases, the imbalance can be related not only to the decrease of Tfh1 in circulation but also to the increase of Tfh2 and/or Tfh17 while Tfh1 levels stay within the norm. Therefore, when analyzing different Tfh populations, it is important to consider the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cell types. However, it is the different types of Tfh cells and their cytokines that can be used as targets for biological therapy in autoimmunity.

Regulatory Th cells (Tregs) mainly target innate (tissue macrophages,

antigen-presenting cells, and natural killer cells) and adaptive immune (effector

cytotoxic T lymphocytes and T helper cells, as well as B lymphocytes) cells. For

this, Tregs enable diverse mechanisms traditionally divided into “non-contact”

(mediated by various Treg-released soluble molecules, which diffuse in tissue

fluids) and “contact” (mediated by interaction between Treg receptors and

surface ligands on target cells) effects [331]. The ability to exhibit regulatory

properties varies markedly among different Treg subsets, which can be detected by

assessing the expression of various surface and intracellular markers. Chemokine

receptor CXCR3 and CCR6-based Treg classification allows to divide total memory

Tregs into Th1-, Th2-, and Th17-like Treg subsets [332, 333]. For instance,

Th1-like Tregs are characterized by transcription factor T-bet, surface CXCR3

expression, and IFN

In the case of Tregs, CXCR3 expression was observed not only on memory cells but

also on around 10% of CD4+CD45RA+CD45RO–CD25hiCD127lo

‘naïve’ Tregs [332]. CXCR3+ Tregs are commonly recognized as a highly

specialized population of Th1-like Tregs that in humans may differentiate

in vitro after exposure to cytokines such as IL-12, IFN

During infections, CXCR3+ Th1-like Tregs may migrate to the site of pathogen entrance and decrease efficacy of innate and adaptive immune responses fighting against microbes. The pathogenic role of for such cells is of special importance in type 1 inflammatory reactions aimed at clearance of pathogens localized inside host cells shown, e.g., in viral infections, including COVID-19.

In COVID-19, increased circulating Treg levels were typical of severe forms of the disease and were also strongly associated with poor outcomes [342]. On the other hand, it was shown that peripheral blood Treg levels progressively increased with COVID-19 severity escalating from mild to severe forms but abruptly decreased in critically ill patients [343]. Moreover, an association between higher CXCR3+ Treg levels and disease severity was also shown [344]. Apart from this, Tregs from patients with severe COVID-19 were characterized by upregulated expression of markers associated with Th1 cells such as CXCR3, GZMK, IL12RB1, and T-bet [342]. In addition, the effect of altered Treg subset composition and functional activity in post-COVID-19 syndrome has been extensively debated [345]. In this regard, the former parameter remained disturbed for up to 6 months even after mild COVID-19 [346], but some studies suggest that both of them may recover to the normal range [347, 348].

A higher CXCR3+ Treg level was observed in patients with HIV infection [349]. Similar data were reported by Yero et al. [350], also noting that before ART, the percentage of circulating CXCR3+ Tregs increased in HIV-infected patients but progressively decreased during therapy.

A crucial role for Th1-like Tregs was demonstrated in liver lesions during

chronic hepatitis C virus infection [351] as well as lethal oral Toxoplasma

gondii infection in mice [352]. Surface OX40 expression is found to coincide with

IFN

In infectious processes, both resident tissue cells and effector T cells may

trigger Tregs expression of transcription factor T-bet and IFN

A whole body of clinical and experimental data revealed that altered Treg cell levels in the bloodstream as well as phenotypic changes and dysfunction at the site of inflammation are related to a high risk of developing human autoimmune diseases [354].

Using in vivo experimental models allowed us to show that CXCR3 and its

ligands play a crucial role in the migration of CXCR3+ Tregs into nervous tissue,

accompanied by a lowered severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

(EAE) [35, 355]. In addition, a rise in CXCL10 as a key ligand for CXCR3+

Tregs was found in nervous tissue lesions, whereas the EAE model in

CXCR3(-/-) mice observed reduced CXCR3+ Treg infiltration into

lesions accompanied by severe chronic inflammation and stronger demyelination and

axonal damage [355]. Also, a high level of CXCR3 ligands was found in nervous

tissue lesions in patients with MS [156, 356]. For instance, MS patients had a

higher IFN

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis were shown to have significantly lower

Th1-like Treg levels in parallel with elevated ESR and CRP levels, as well as a

high level of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP) and anti-mutated

citrullinated vimentin (anti-MCV) autoantibodies, whereas the level of Th1-like

Tregs in the joint capsules was negatively correlated with the DAS28 scale [337].

However, Th1-like Tregs from RA patients could not effectively block in

vitro T-cell proliferation assessed in functional tests, indicating thereby that

their suppressive properties were impaired for yet unknown reasons. Similar data

were obtained by Kommoju et al. [361], showing higher levels of

CXCR3+ Tregs in peripheral blood and SF from patients with RA, as well as a

direct relation between their level and seropositivity along with disease

activity. Children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, the most

common form of chronic inflammatory arthritis, were found to have synovial fluid

Tregs dominated by phenotype, with highly expressed CXCR3, IFN

Furthermore, IL-17+Foxp3+ Th17-like Tregs were also detected in

the SF of RA patients. Patients with T1D vs. control subjects had comparable levels of peripheral blood

CD4+CD127lo/-CD25+ Tregs, whereas the percentage of Th1-like Tregs

(Foxp3+IFN

Impaired thymic Treg differentiation was shown primarily in SLE and might profoundly affect relevant cell subset composition and functional properties both in peripheral tissues and in in vitro settings [370]. A decline in the level of circulating CD4+CD25–CD127dim/- Tregs was observed in SLE, so these cells exerted lower in vitro potential to suppress effector T cell proliferation, and they were also characterized by an increased level of apoptosis that correlated with disease activity [371]. It was shown that Foxp3+Helios+ Tregs in SLE patients expressed surface chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR4 at a level that insignificantly differed from that in the control group [372]. Also, some studies reported that SLE patients had an increased level of Th17-like Tregs able to produce IL-17 [373]. Moreover, mouse models revealed that the loss of Th17-like Tregs was accompanied by exacerbated pulmonary vasculitis, Th17 cell accumulation, and markedly higher mortality [374]. On the contrary, another in vivo study demonstrated that, at least in mice, Th17-like Tregs exhibited both protective and proinflammatory effects [375].

An experimental model of Sjögren’s syndrome was associated with increased

peripheral blood IFN

Available publications assessing peripheral blood Treg percentage and absolute number in patients with AS are quite contradictory. For instance, some studies showed that circulating Treg levels in patients vs. control subjects did not differ significantly [178, 379, 380], whereas others noted significantly decreased CD4+CD25+FoxP3+, CD4+CD25+CD127–[381]and CD4+CD25highCD127low/- Treg subsets [382]. In addition, Treg level was found to negatively correlate with BASDAI scores [383]. In connection with this, a role for individual Treg subsets, however, has not yet been thoroughly investigated.

A high level of Th1-like Tregs was found in intestinal lamina propria lesions

during ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, implying that IFN

Relatively recently, it was shown that patients with IgG4-related disease had elevated levels of peripheral blood CD4+CD25hiCD127lowCD161+ Th17-like Tregs that negatively correlated with serum C3 and C4 complement component concentrations [389]. Moreover, a high Treg infiltration level in inflamed tissue was observed in autoimmune pancreatitis, IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, and salivary gland tissues in Mikulicz disease [390].

In the case of sarcoidosis, a rise in the level of CXCR3-expressing Tregs—Th1-like and Th17.1-like Tregs—was shown, along with a decline in CXCR3–CCR6+ Th17-like Tregs among the total CD45RA-CCR7-effector memory Treg population [391]. Numerous studies point to increased concentrations of all three CXCR3 ligands, CXCL9 (MIG), CXCL10 (IP-10), and CXCL11 (I-TAC), both in serum [88, 94, 392] and BALF samples, where they are abundantly produced by alveolar macrophages [393, 394], which may be a hallmark cue for Treg recruitment into the site of inflammation. Despite this, CXCR+CCR6+ Th17.1 cells dominated in BALF, whereas Treg levels were significantly lower than those in peripheral blood [253], potentially suggesting poor BALF Treg activity in suppressing inflammatory reactions in sarcoidosis.

In psoriasis, elevated phosphorylation of the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) was

found in the circulating cells, which exerted a lowered potential to exhibit

suppressive properties but produced large amounts of IFN

Decreased peripheral blood Treg levels were observed in patients with Graves’ disease [399], which was further corroborated by molecular and biological study [400]. At the same time, the level of Tregs expressing surface CD69 activation markers in patient peripheral blood was increased, but their potential to suppress in vitro T cell proliferation was downmodulated [401]. Later, it was evidenced that Treg effector functions may be impaired [402]. which is also demonstrated in the meta-analysis by Chen et al. [403]. However, no experimental data on Treg subset composition is currently available.

The data indicates that CXCR3+ Tregs provide an important role in inflammatory reactions and their regulation, especially in tissues rich in CXCR3 ligands. In the early stages of immunity, CXCR3 ligands attract large amounts of effector cells, which initiate inflammation and pathogen elimination. CXCR3+ Tregs are not enough to suppress immunity. At the same time, when inflammation becomes chronic, there is an increase in the CXCR3+ Treg population; such a tendency can play a role in compensation mechanisms. These cells can be potentially used as a marker for therapy efficacy. Unfortunately, at this point in time, data on the matter is still lacking.

Tc1 CD8+ T lymphocytes like Th1 cells are essential in underlying type 1

inflammatory reactions, which is coupled to their prominent cytolytic properties

mediated by perforin and granzymes stored in the cytosolic granules as well as

the production of effector cytokines IFN