1 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6H 3Z6, Canada

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

As professional phagocytes, macrophages represent the first line of defence against invading microbial pathogens. Various cellular processes such as programmed cell death, autophagy and RNA interference (RNAi) of macrophages are involved directly in elimination or assist in elimination of invading pathogens. However, parasites, such as Leishmania, have evolved diverse strategies to interfere with macrophage cell functions, favouring their survival, growth and replication inside hostile and restrictive environments of macrophages. Therefore, identification and detailed characterization of macrophage-pathogen interactions is the key to understanding how pathogens subvert macrophage functions to support their infection and disease process. In recent years, great progress has been achieved in understanding how Leishmania affects with critical host macrophage functions. Based on latest progress and accumulating knowledge, this review exclusively focuses on macrophage-Leishmania interaction, providing an overview of macrophage cellular processes such as programmed cell death, autophagy and RNAi during Leishmania infection. Despite extensive progress, many questions remain and require further investigation.

Keywords

- macrophages

- Leishmania

- host-pathogen interactions

- effector mechanisms

Macrophages, commonly abbreviated as “M

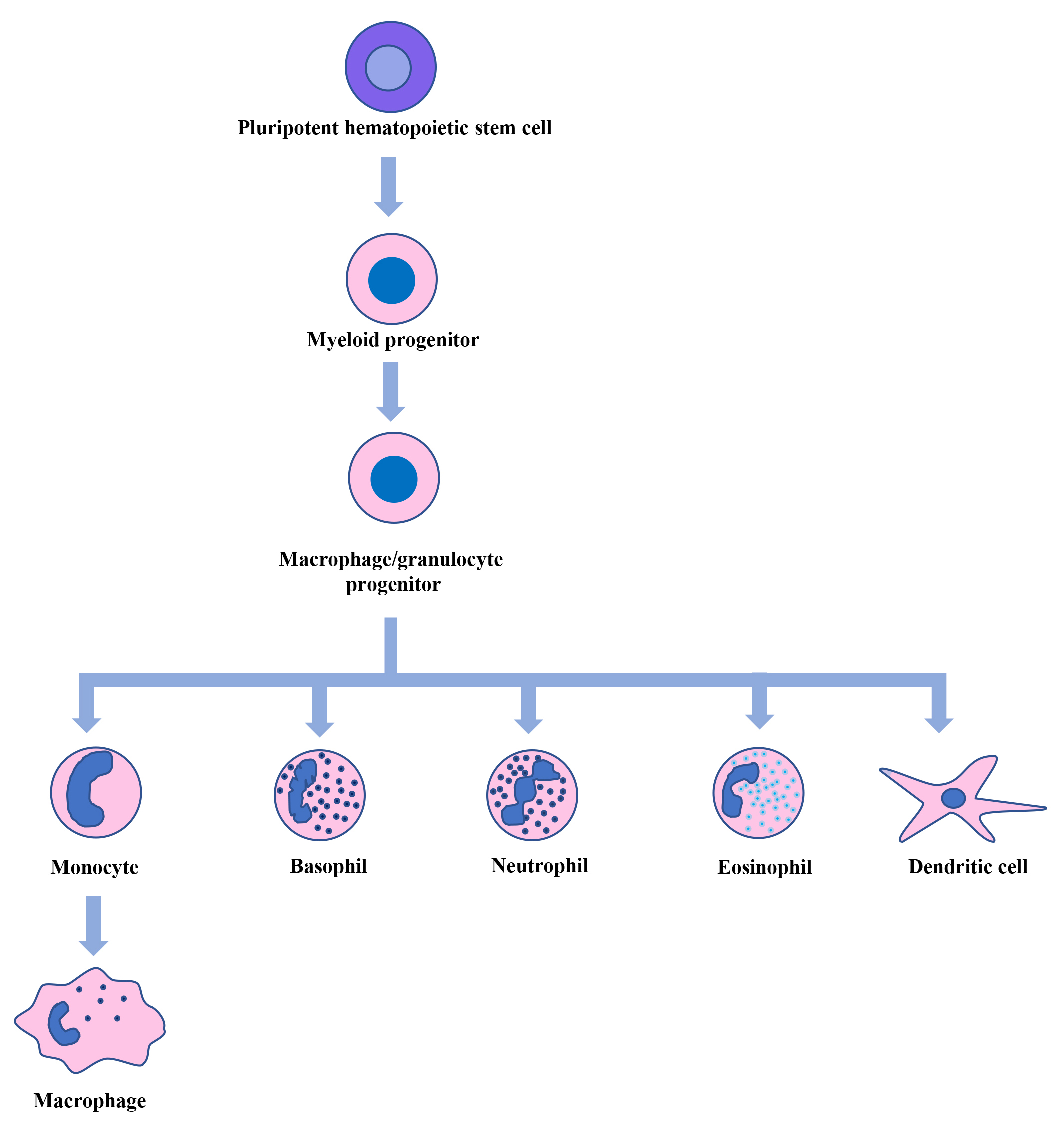

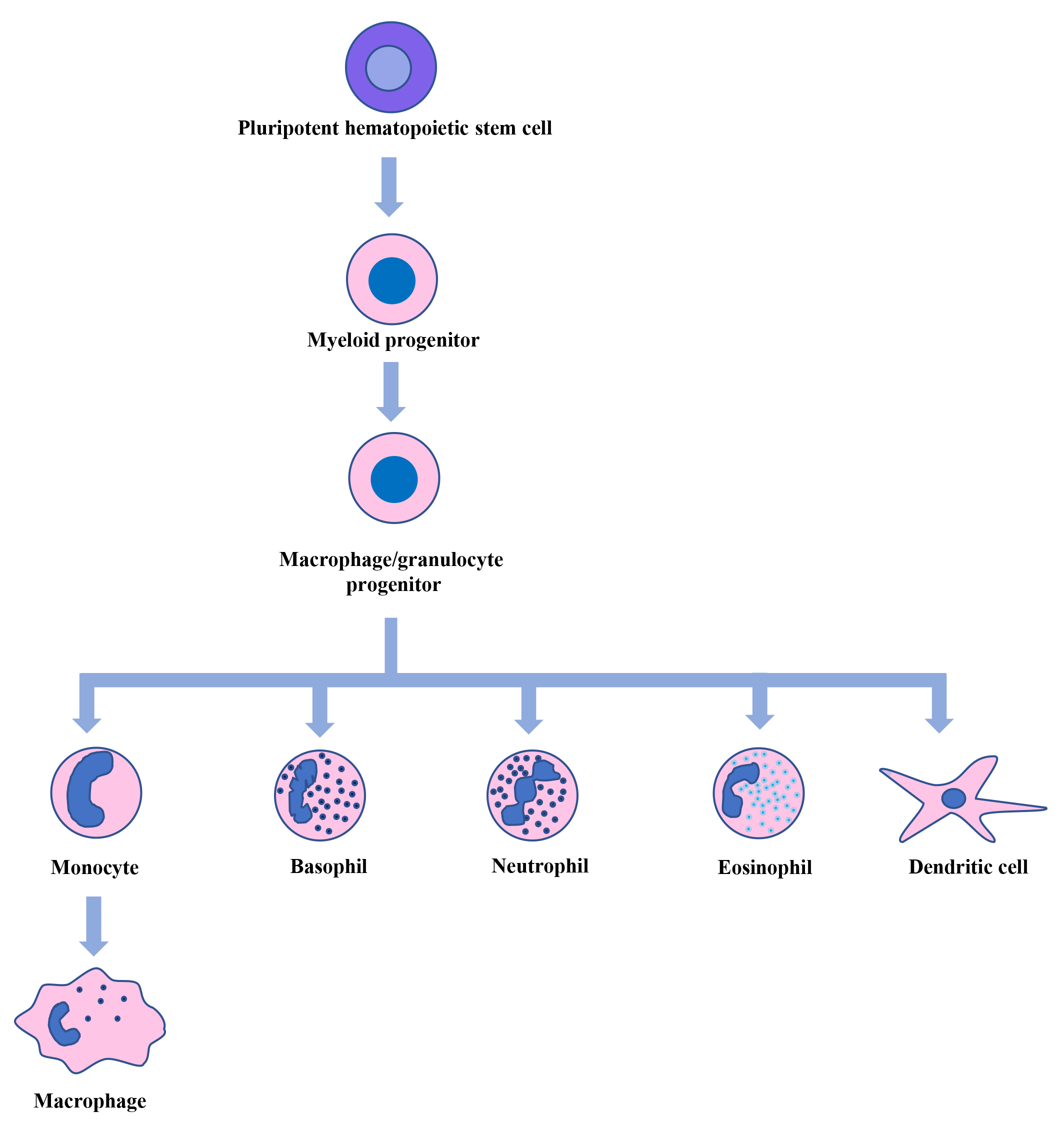

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hematopoiesis. Pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow generate myeloid, lymphoid, and erythroid progenitor cells. From myeloid progenitor cells, macrophage/granulocyte progenitor cells are formed, which give rise to monocytes, basophils, neutrophils, eosinophils, and dendritic cells. The circulating monocytes then move into different tissues and differentiate into macrophages.

The introduction to macrophages in this review is mainly in the context of immunity and infection.

Depending on various environmental cues, resting macrophages (M0) can adopt

distinct activation states, M1 (classically activated) and M2 (alternatively

activated). M0 macrophages, when activated by proinflammatory cytokines like

interferon(IFN)

Macrophages, strategically placed in almost all body tissues, can respond to injury, pathogens and antibody opsonized pathogens, by performing either effector or sentinel functions. As effector cells of innate immunity, macrophages eliminate microbial pathogens by phagocytosis, secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, antimicrobial mediators and initiation of apoptosis to limit intracellular pathogen load [15, 16]. Pathogen elimination begins with pathogen recognition—mainly involving pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)—which are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) found on the surface of innate immune cells. Some PRRs, like Toll-like receptors (TLRs), play a central role in host cell recognition of invading microbial pathogens. Other receptors, like complement receptors can also detect foreign pathogens. Interaction between host and pathogens triggers phagocytosis, starting with macrophage membrane protrusions surrounding pathogens and resulting in phagosomes, which ultimately fuse with lysosomes to transport pathogen into phagolysosomes for elimination. In the phagolysosomes, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADH)-oxidase produces ROS, and nitric oxide synthase produces NO. These reactive molecules play an important role in effectively killing phagocytosed pathogens [17, 18, 19]. Active NADH oxidase increases oxygen consumption, referred to as an “Oxidative burst” leading to the production of H2O2 by superoxide dismutase [17, 20].

In addition, macrophages can act as sentinel cells to commence innate or adaptive immunity activation by secreting chemokines and proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory factors or by presenting antigens on their surface to recruit adaptive immunity cells [16]. Moreover, they are also involved in the clearance of damaged/dead cells and tumor cells, thus promoting homeostasis.

In addition to phagocytosis, there are other mechanisms through which pathogen neutralization in macrophages can occur. Macrophage autophagy—a lysosomal degradation pathway for intracellular components—plays a key role in innate immunity, especially in the context of infection and inflammation [21, 22]. In most situations, activation of autophagy has antimicrobial effects by directly targeting pathogens to lysosomal degradation. The breakthrough in deep sequencing and other technologies have revealed the key role played by non-coding RNAs in shaping the immune response. In recent years, ample evidence has accumulated that microRNAs (miRNAs) are associated with innate immune processes through post-transcriptional regulation of proteins either by degradation of mRNAs or by translational interference [23, 24, 25, 26].

This review provides an overview of innate immunity-related macrophage functions, such as apoptosis, autophagy and RNA interference (RNAi), in the context of intracellular infections using Leishmania as a paradigm. The following sections highlight recent advances in understanding how Leishmania employs various complex strategies to regulate the numerous functions of host macrophages to survive the defence mechanisms/innate immunity rather than a detailed overview of all the literature in the field.

At the site of infection, macrophages get recruited, leading to phagocytosis of invading pathogens. Accordingly, macrophages have microbicidal arsenals to directly kill or coordinate the eliminating pathways. Paradoxically, many intracellular pathogens preferentially reside and replicate inside the hostile environment of macrophages. These pathogens have evolved to exploit the fundamental biology of macrophages to grow and proliferate in unique cellular and metabolic environment. An excellent example is Leishmania, an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite. Macrophages act as the primary host cells for Leishmania, where they reside, grow and proliferate. Over the years, studies related to Leishmania-macrophage interactions have provided critical information on host defence mechanisms against intracellular pathogens and how Leishmania has evolved to regulate numerous aspects of macrophage biology, ensuring its survival inside infected macrophages.

Various human pathogens are transmitted by blood-sucking arthropods, collectively called vector-borne diseases. Leishmaniasis is a spectrum of diseases caused by around 20 Leishmania species transmitted worldwide by infected female sandflies [27]. Out of almost 1000 sandfly species described thus far, only 10% of them are demonstrated or suspected vectors of Leishmania parasites [28]. Disproportionally affecting humans in resource-poor countries in the tropical and subtropical regions, leishmaniasis is considered a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) [29]. According to recent estimates, around 350 million people in 98 countries are affected by leishmaniasis [30, 31, 32]. Leishmaniasis most commonly occurs in tropical, subtropical and Mediterranean regions of the world [33]. However, there is a real risk of leishmaniasis spreading to non-endemic areas of the world facilitated by migration, globalization, changes in weather patterns, and war/conflicts in the endemic regions. Leishmaniasis is on the rise in endemic areas due to a lack of approved prophylactic human vaccines, drug resistance and a lack of interest among big pharmaceutical industries to develop new drugs against leishmaniasis [34, 35, 36].

Like many protozoan parasites, Leishmania has a complex digenetic life cycle that involves both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts and two morphologically distinct forms: the extracellular motile promastigotes (sandfly vector) and non-motile intracellular amastigotes (mammalian hosts). The promastigote form is found in the midgut of sandflies whereas the amastigote form occurs intracellularly, primarily in phagolysosomes of macrophages. The bite of an infected sandfly transmits Leishmania by injecting infective stage promastigotes into the dermis of a mammalian host during a blood meal. Infective promastigotes are ingested by host macrophages and transformed into non-motile amastigotes, which then multiply, leading to clinical manifestation. Sandflies become infected when they take a blood meal from an infected mammalian host. In the sandfly gut, amastigotes are transformed into promastigotes, multiply and move to proboscis [37]. Most Leishmania species that are pathogenic to humans have zoonotic transmission involving dogs, jackals, and rodents, serving as reservoir hosts for Leishmania pathogens. Leishmaniasis in nature is maintained by the complex interactions among Leishmania parasites, sandfly vectors, mammalian hosts (including humans) and zoonotic reservoirs. Interactions between Leishmania parasites and sandflies have recently been reviewed [38, 39] and won’t be reviewed here. The current review is mainly restricted to macrophage-Leishmania interactions.

It is becoming increasingly clear that Leishmania tropism/virulence is

not solely associated with disease pathogenesis. Complex interactions between

Leishmania and its host determine infection and disease progression. As

discussed above, leishmaniasis is initiated by the entry of promastigotes into

mammalian hosts’ dermis during an infected sandfly’s bite. Promastigotes are

inoculated into the pool of blood created by the bite of a sandfly, where they

interact with leukocytes. Many deposited Leishmania are quickly ingested

by neutrophils, recruited due to substantial tissue damage and inflammation [40, 41]. It is also gaining traction that sandfly microbiota is critical to

leishmaniasis development and transmission by host IL-1

In addition to Leishmania interaction with macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells, other cells such as fibroblasts [50] and B-1 cells [51] can also be infected with Leishmania spp. Interestingly, B-1 cells can be differentiated to phagocytic cells and have been shown to phagocytose L. major promastigotes [51]. Further, it was shown that internalized parasites transformed into amastigotes and were able to secrete pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines after stimulation [51]. These cells primarily used mannose receptors for phagocytosis of Leishmania. Despite the seemingly important role played by B-1 cells, few studies attempted to evaluate role of B-1 cells during Leishmania infection. Recently, these studies have been reviewed in the context of the role played by B-1 in disease progression during infection with Leishmania spp [52].

It is a conserved physiological process of non-lytic, programmed cell death which occurs in all multicellular organisms. It is mainly characterized by cytoplasmic shrinkage, chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, and plasma membrane blebbing [53]. Apoptotic cells also showcase cell surface markers like phosphatidylserine (PS), usually present on the inner surface of the cell’s plasma membrane. PS is recognized by the phagocytic cells, like macrophages, as an “eat me” signal [54, 55]. Apoptosis is considered ‘immunologically silent’, whereas other forms of cell death, such as pyroptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis, are considered relatively ‘violent’ types of cell death [56]. Apoptosis is mediated by the caspase enzymes, which have proteolytic activities to cleave proteins at aspartic acid. So far, twelve caspases have been described in humans [57]. Based on the type of stimulants, apoptosis can be carried out via—the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway, extrinsic or death receptor pathway and the caspase (aspartate-specific peptidases, dependent on cysteine)-independent pathway [58]. Extrinsic apoptosis is triggered by the binding of a ligand such as Fas ligand (FASL), TNF, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), and TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) to members of the TNF receptor superfamily, leading to receptor oligomerization and the recruitment of adaptor proteins containing death domains such as tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1)-associated death domain protein (TRADD) and Fas-associating protein with death domain (FADD). These complexes activate caspase-8, further activating caspase-3 and caspase-7, resulting in cell death. The intrinsic pathway is induced by cellular stress, which can originate from DNA damage, oxidative stress, radiation, hypoxia, and nutrient deprivation. Regardless of how this pathway is induced, it always leads to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and is intricately regulated by proteins that belong to the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family. The BCL-2 family of proteins contains both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members. Ultimately, the intrinsic pathway leads to the membrane potential dissipation, release of cytochrome c and other toxic proteins into the cytoplasm and inhibition of the respiratory chain. The cytochrome c released from the mitochondria also interacts with apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 (APAF1) to form apoptosomes, activating the initiator caspase-9. In the caspase-independent pathway, release of toxic proteins from the intermembrane space of the mitochondria to the cytoplasm due to mitochondrial damage can induce apoptosis and does not include caspases [58, 59, 60].

Apoptosis plays a crucial role in many biological processes, including cellular

defence, and cellular and tissue remodelling, which are essential for the

homeostatic balance of an organism. Due to this, apoptosis is tightly regulated

by various proteins and furthered by an intricate network of signalling pathways.

Depending on the situation, they can activate or deactivate apoptosis [61]. The

PI3K/AKT signalling pathway is one of the key pathway which negatively regulates

apoptosis, mainly by activating anti-apoptotic genes and deactivating

pro-apoptotic genes [61]. Active AKT can inhibit apoptosis by phosphorylating

BCL-2 associated agonist of cell death (BAD) protein, a member of the BCL-2

family, and promoting its degradation. It can also inhibit glycogen synthase

kinase-3

Apoptosis has been shown to play a key role in the development, regulation and function of the immune system. Induction of cell death during infection has been demonstrated in several bacterial, viral and parasitic infections that significantly impact pathogenesis [71, 72, 73]. The death of an infected cell often results in the death of an infecting agent, thus promoting pathogen clearance. Therefore, the initiation of cell suicide in infected cells is promoted to limit infection. In addition, phagocytosis of a dying infected macrophage by dendritic cells results in enhanced antigen presentation to T cells for adaptive immunity [74, 75, 76]. As already mentioned, apoptosis is an important host defence mechanism against intracellular pathogens. However, some pathogens employ a range of strategies to inhibit apoptosis and survive and reproduce [77, 78, 79, 80, 81]. Leishmania is an excellent example of an intracellular pathogen that promotes its survival inside host cells by employing numerous smart strategies to counteract this host cell defence mechanism. The following section mainly overviews the manipulation of host macrophage apoptosis by Leishmania.

Several protozoan parasites are known to regulate apoptosis for their survival

[82]. Moore and Matheshewski in 1994 [83] were the first to demonstrate that

L. donovani or lipophosphoglycan (LPG), the major surface molecule of

L. donovani promastigotes, can inhibit apoptosis in bone marrow-derived

macrophages (BMDMs) activated by deprivation of M-CSF. They could also

downregulate apoptosis when treated with supernatants of the L.

donovani-infected macrophages, indicating the involvement of soluble factors.

The cytokine profiling of the infected cells showed increased gene expression for

granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF), TNF

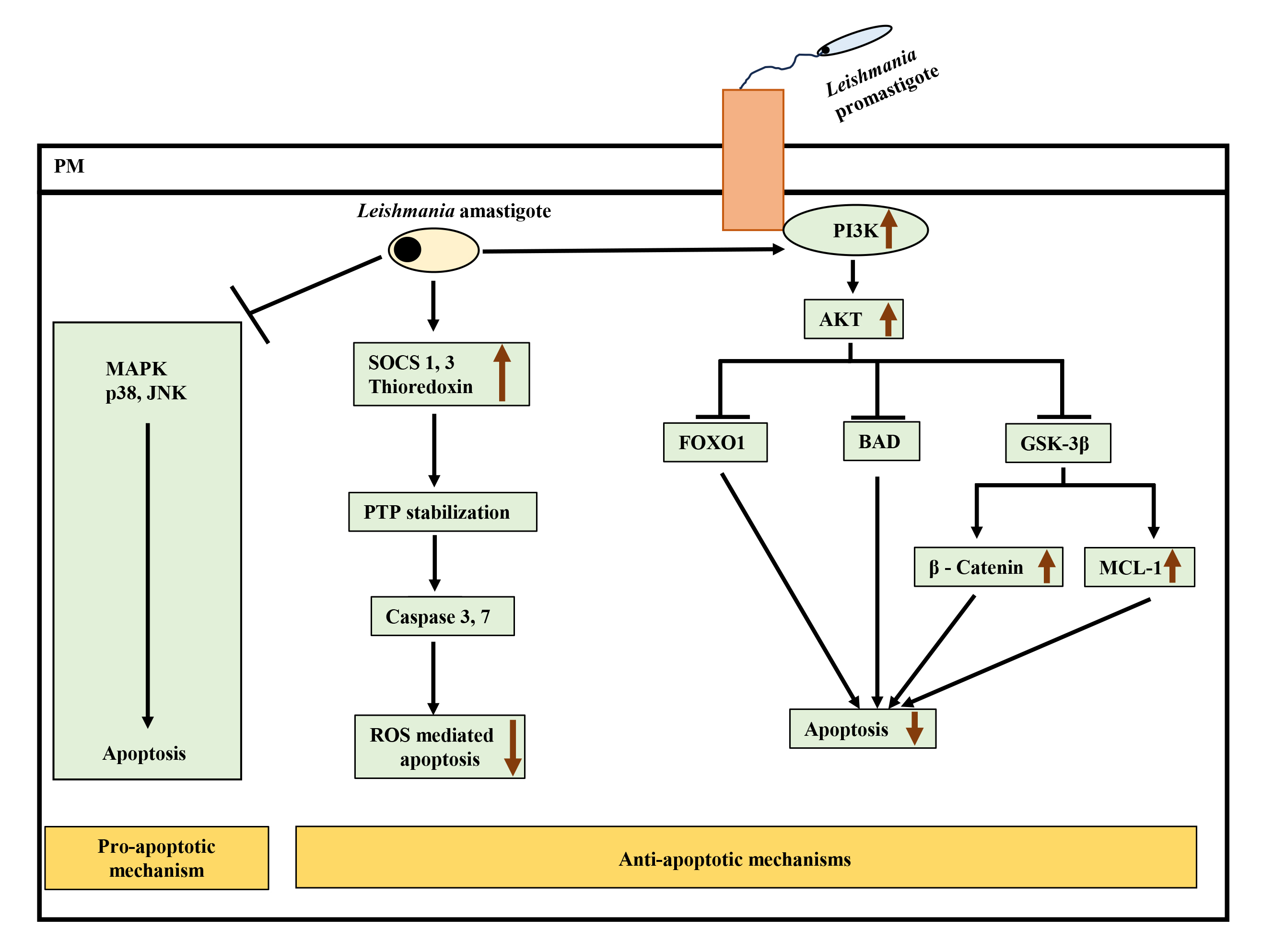

It has been shown that L. donovani evade the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in naïve

macrophages by not triggering phosphorylation of p38, JNK and ERK1/2, ensuring

parasite survival [87]. Later, in another study, it was also shown that upon

inhibiting p38 MAPK by pharmacological inhibitor SB203580, the number of infected

macrophages and parasite survival in BMDMs increased [88]. Leishmania

can also prevent programmed cell death by upregulating anti-apoptotic pathways

like the PI3K/AKT pathway. For example, L. donovani induced AKT

phosphorylation, inhibiting FOXO-1 and, therefore, the transcription of

pro-apoptotic genes. Activated AKT also inhibited GSK-3

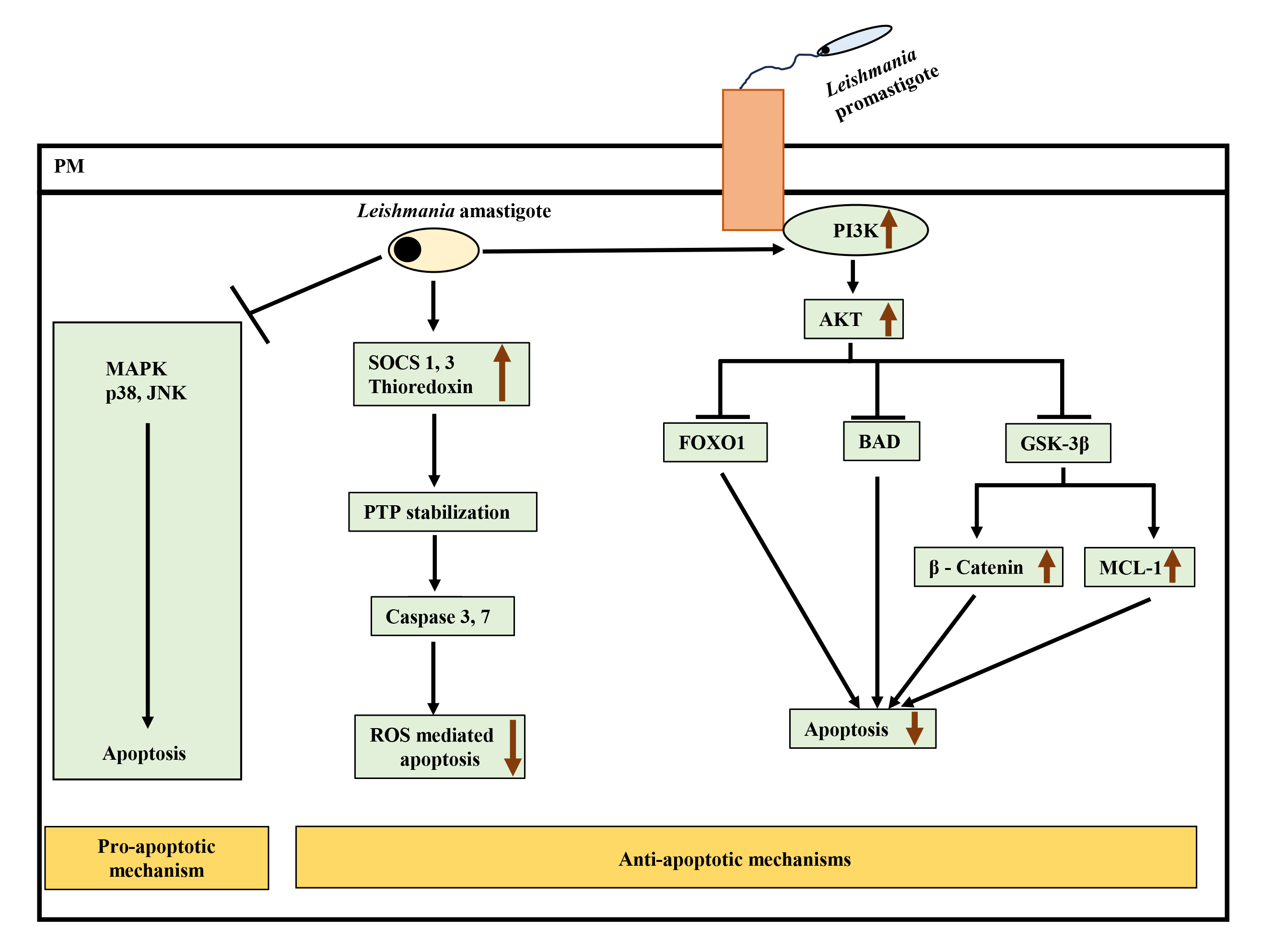

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Interplay of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic pathways leading

to inhibition of apoptosis after Leishmania infection.

Leishmania attenuates pro-apoptotic MAPK p38 and JNK signaling and

simultaneously activates anti-apoptotic PI3K-Akt pathway to inhibit apoptosis.

Active Akt negatively regulates forkhead box protein O (FOXO1), Bcl-2 associated

agonist of cell death (BAD), and glycogen synthase kinase-3

Leishmania can also interact with other BCL-2 family members to promote its survival. For example, L. donovani upregulated MCL-1 (anti-apoptotic protein of the BCL-2 family) in murine macrophages to prevent BAK-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis [91]. The activation of BCL-2 in L.donovani-infected macrophages led to NO production inhibition, enhancing parasite survival. In monocytes derived from the blood of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) patients, BCL-2 expression was observed to be increased significantly with reduced nitrites [92].

Interestingly, L. donovani infection in RAW264.7 cells has been shown to take advantage of the SOCS pathway to resist ROS-mediated apoptosis. Infection induced SOCS proteins 1 and 3 and thioredoxin, downregulating downstream caspases 3 and 7, leading to inhibition of ROS-mediated apoptosis [70] (Fig. 2). This study also reported downregulation of p38 activation upon infection.

In addition to the exploitation of host factors to inhibit apoptosis, proteins from Leishmania parasites can also inhibit host macrophage apoptosis. For instance, a structural ortholog of macrophage inhibiting factor (MIF) produced by L. major, when transfected into murine macrophages, was shown to activate ERK1/2 MAPK to inhibit macrophage apoptosis in vitro [93]. In another study, L. amazonensis was shown to delay apoptosis or prevent ATP-mediated cytolysis of murine macrophages by releasing nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) [94].

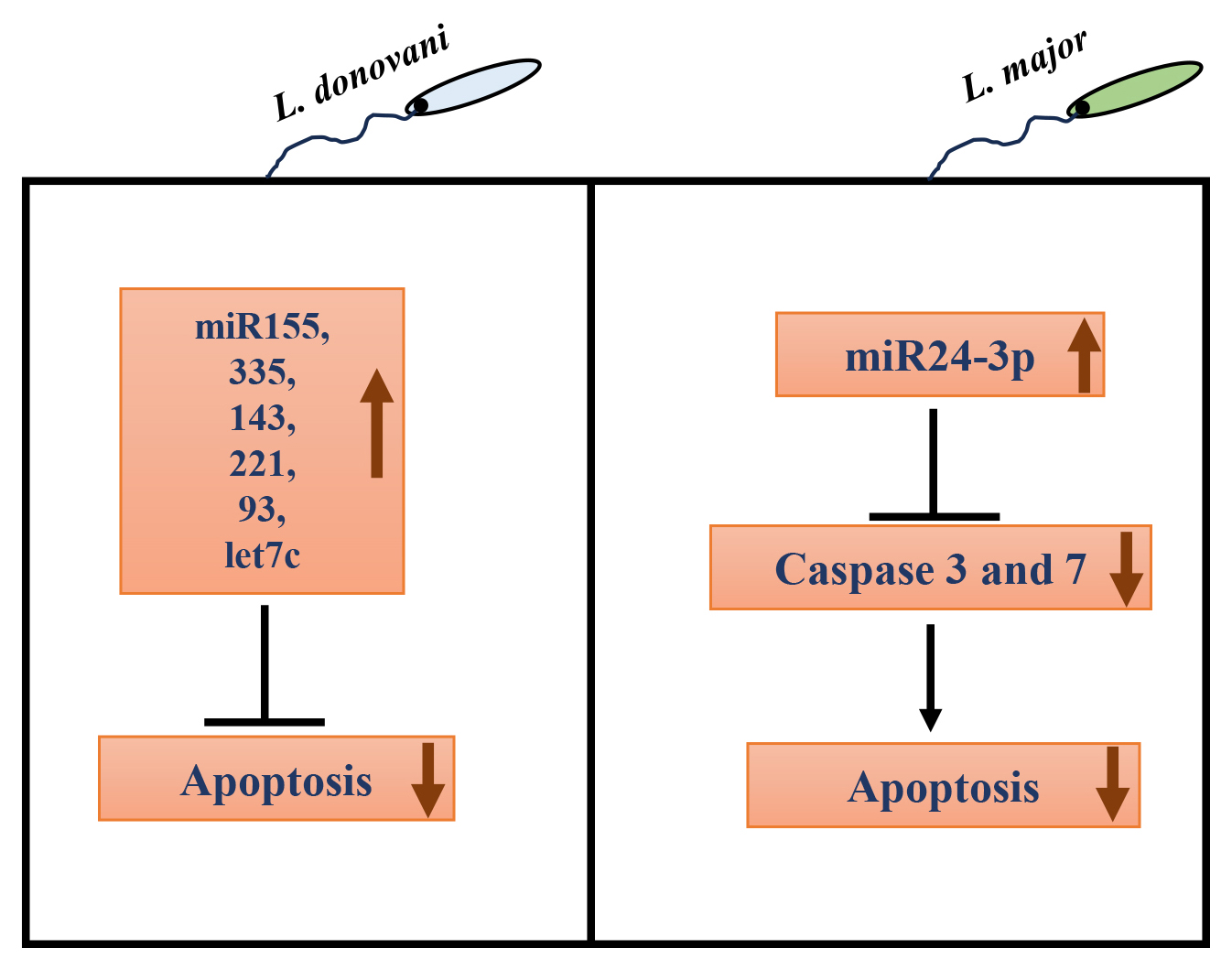

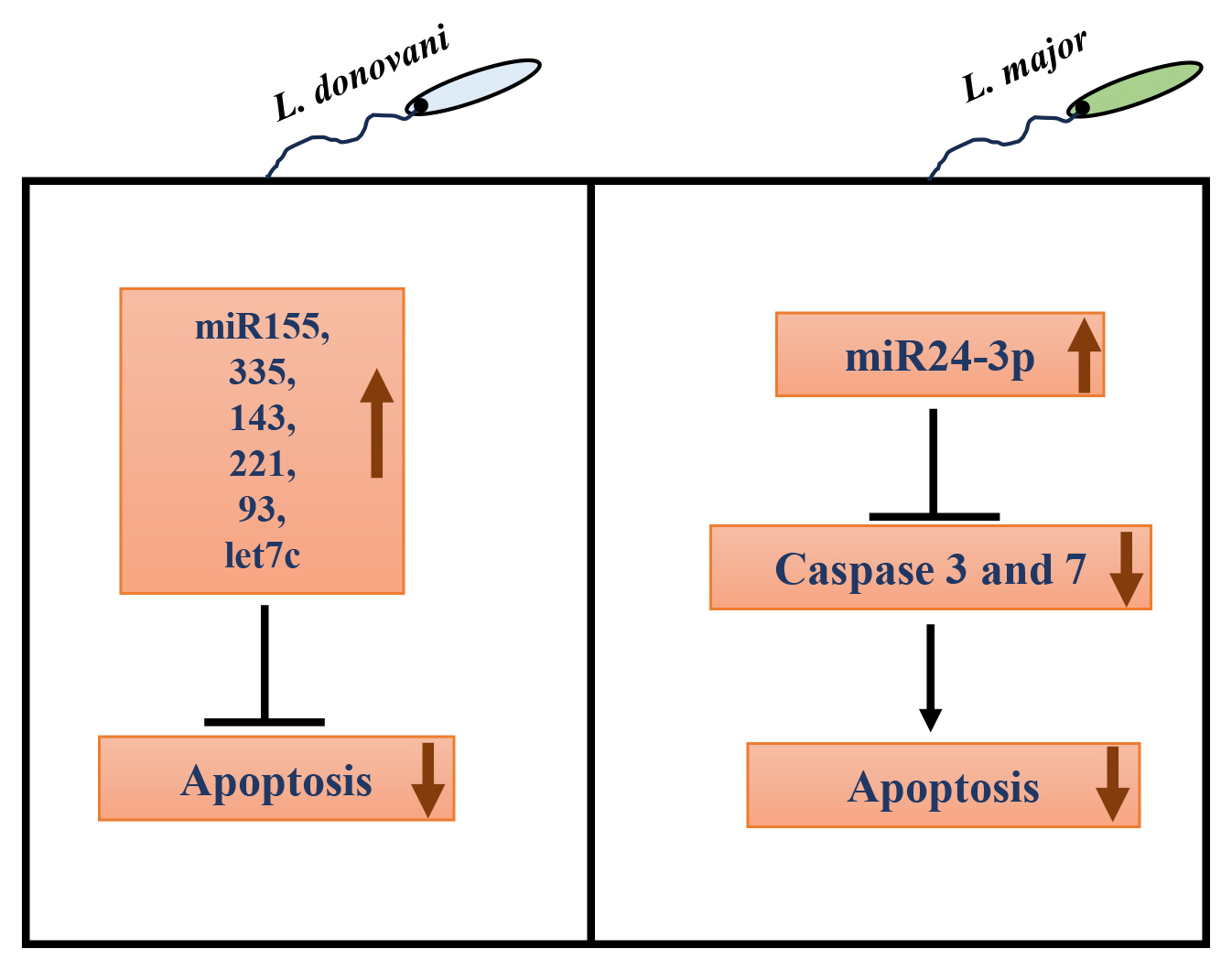

Recently, in addition to the involvement of host/parasite protein factors, the role of host miRNAs in regulating apoptosis upon infection with protozoan parasites like Leishmania has only begun to emerge. In L. donovani-infected macrophages, various miRNAs like miR-155, miR-335, miR-143, miR-221, miR-93, and let7c have been associated with negative regulation of apoptosis [95]. In L. major infected RAW264.7 cells and BALB/c mice, miR-155 inhibitor and miR-15a mimic increased apoptosis, reducing parasite burden [96]. In another study, L. infantum infection in macrophages also upregulated miR-155a expression [97]. miR-155a is known to destabilize caspase 3 mRNA, resulting in decreased apoptosis [98, 99]. On the other hand, miR-15a negatively regulates Bcl-2 and Mcl-2 gene expression and cell survival [100]. The expression of another miRNA, miR-24-3p, was also upregulated in L. major infected macrophages rapidly post-infection. Further, bioinformatic analysis revealed the anti-apoptotic effect of miR-24-3p by repressing pro-apoptotic genes like caspases 3 and 7 [101] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Role of host microRNAs (miRNAs) in autophagy regulation in Leishmania infected macrophages. In L. donovani infection, many host miRNAs like miR-155, miR-335, miR-143, miR-221, miR-93, and let7c have been associated with negative regulation of apoptosis. In L. major infected macrophages, miR24-3p increases, which decreases pro-apoptotic caspase 3 and 7 gene expression, inhibiting apoptosis.

The studies reviewed in this section show that host apoptosis plays an important role in leishmaniasis. However, further investigation delineating the detailed molecular mechanisms of Leishmania-mediated regulation of host apoptosis is needed to understand the pathophysiology of leishmaniasis fully. The knowledge generated will provide the basis for novel discoveries about leishmaniasis.

Although this section is mainly restricted to exploitation of apoptosis by

Leishmania. It is of interest to point out that other trypanosomatid

pathogens such as T. cruzi also take advantage of apoptosis to

facilitate parasite spreading. It has been shown that T. cruzi infection

triggers activation-induced cell death of T-lymphocytes during the acute phase of

infection [102, 103]. Interaction of apoptotic, but not necrotic, T-lymphocytes

with T-cruzi-infected macrophages promoted parasite growth. This

interaction triggered the release of TGF-

In this section, we overview a limited number of studies regarding the interaction of Leishmania with host macrophage autophagy that could play critical roles in the outcome of infection.

It is an evolutionarily conserved pathway that enables cells to digest their cytoplasmic contents, aiding in recycling and maintaining homeostasis. In eukaryotic cells, there are three mechanistically distinct types of autophagy—macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. In this review, we focus on macroautophagy—the most important type of autophagy—and will be referred to as autophagy herein. Autophagy is characterized by the active degradation of cytoplasmic constituents that are engulfed by double-membrane structures, known as autophagosomes. These distinctive structures ultimately fuse with lysosomes to form autophagolysosomes. It is at this stage that the intravesicular contents are degraded [105]. Autophagosome biogenesis is a complex process involving multiple proteins and lipids [106, 107, 108]. Central to autophagy are evolutionarily conserved proteins called autophagy-related proteins or ATGs. Among more than 30 autophagy-related (ATG) proteins identified thus far, the lipid-conjugated protein marker, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3b (LC3-II)/ATG8, associates with the autophagosome double membrane, has been used extensively as an indicator of autophagy in a wide variety of cells and tissues [109].

Autophagy can be regulated via multiple signalling pathways. Broadly, the two most commonly defined pathways are either mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent or mTOR-independent [105, 110]. The mTOR-dependent pathway involves PI3K-AKT activating mTOR, which leads to the inhibition of cellular autophagy. This is considered to be the classical pathway of autophagy regulation. mTOR-independent regulation of autophagy has also been identified [111]. Inositol-lowering agents, such as lithium, induce autophagy independent of any change in mTOR activity [112]. Previously, it was assumed that autophagy was exclusively a bulk process involving a non-selective pathway. However, recent evidence has clearly established that through the use of autophagy receptors and adaptors, autophagy can be selective and exclusively degrade specific cellular constituents and better fulfil the catabolic needs of the cell [113, 114]. It is well established that LC3-II plays a vital role in the biogenesis of autophagosomes. In addition, it also seems to play a key role in selective autophagy by tethering cargo to the sites of engulfing autophagosomes and by serving as docking sites for adaptor proteins [115, 116, 117, 118, 119].

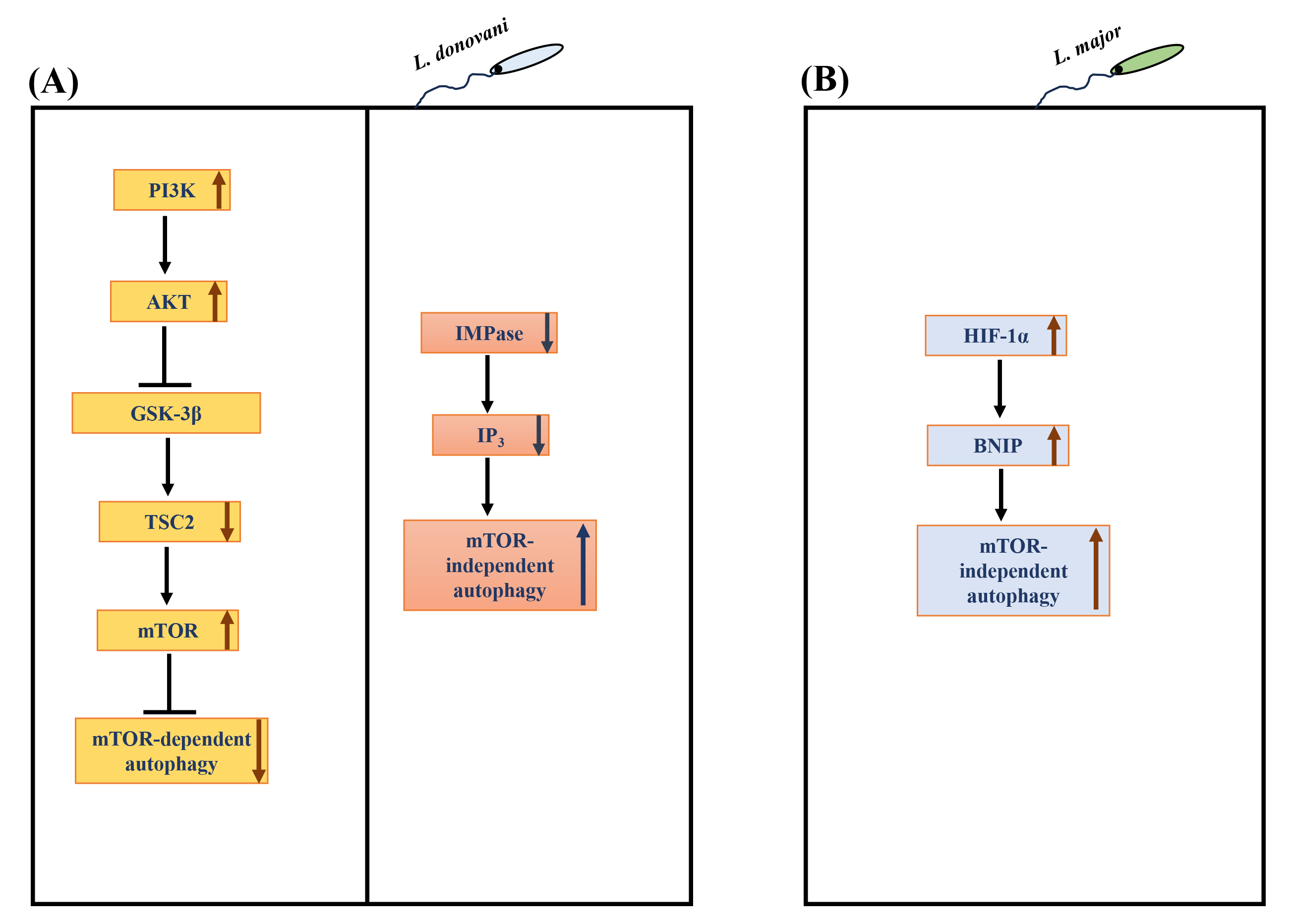

Due to its role in many physiological processes, it is unsurprising that the dysregulation/manipulation of autophagy is implicated in various diseases [22] and infections [120, 121, 122, 123]. In addition, autophagy has been involved in defence against intracellular pathogens [22, 124]. Notably, macrophage autophagy attenuates the survival of numerous pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Shigella flexneri, among others [22]. On the other hand, certain intracellular pathogens such as Toxoplasma gondii [123], Hepatitis C virus [125] and Coxiella burnetiid [126] appear to have evolved to regulate host autophagy to their advantage. Several species of Leishmania have been observed to induce macrophage autophagy [127, 128, 129, 130, 131], but the molecular mechanism(s) involved in the autophagy response are yet to be established. Understanding the regulatory mechanisms and key players involved in autophagy will provide critical insights into Leishmania-macrophage interactions. Our group recently showed bidirectional regulation of macrophage autophagy by L. donovani to promote their survival in human mononuclear phagocytes [132]. L. donovani uses the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway to actively attenuate host autophagy in infected hosts at early and late-stage infection. Continuous L. donovani-mediated activation of host AKT sustains mTOR activity, which, in turn, suppresses autophagy at early and late-stage infection. However, once infection becomes established, L. donovani promotes mTOR-independent autophagy selectively [132] (Fig. 4A). Disruption of autophagy by downregulating macrophage ATG5 or ATG9A (essential autophagy proteins) resulted in a marked decrease in L. donovani survival [132], leading to the discovery that autophagy promotes intracellular survival. These exciting findings regarding the regulation of macrophage autophagy by L. donovani indicate that pathogen uses dual strategies to exert countervailing effects on host autophagy. Based on these findings, it is tempting to hypothesize that L. donovani fine-tunes autophagy to suit its catabolic needs to promote optimal parasite survival. Another recent study from our group [133] further explored the role of autophagy in Leishmania-infected cells. This study identified the protein constituents of L. donovani-induced autophagosomes. The proteomic content of autophagosomes upon Leishmania infection was compared with the proteome of autophagosomes of THP-1 cells induced with known autophagy inducers like rapamycin and starvation. This study revealed that 146 proteins were significantly modulated in L. donovani-induced autophagosomes compared to the rapamycin-induced autophagosomes, whereas 57 were significantly modulated compared to starvation-induced autophagosomes. Therefore, it showed that the composition of Leishmania-induced autophagosomes was more similar to starvation- rather than rapamycin-induced autophagosomes, which suggests the non-selective nature of L. donovani-induced autophagy. Interestingly, 23 Leishmania proteins were also detected in the proteome of L. donovani-induced autophagosomes.

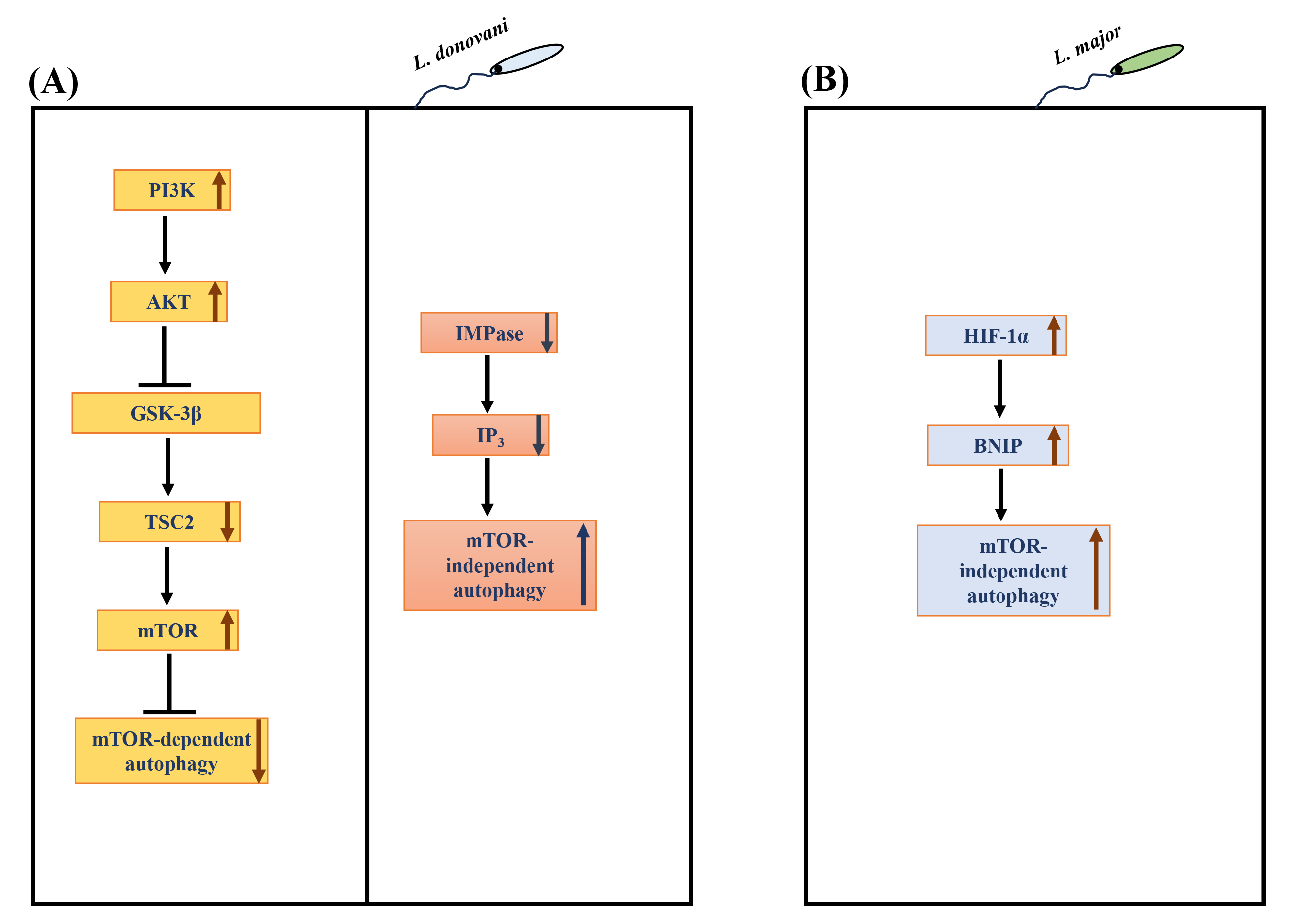

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of autophagy in Leishmania infected

macrophages. (A) L. donovani hijacks the

PI3K-AKT-GSK3

Infection with L. major has also been reported to induce host

autophagy. Elevated levels of LC3-II increased the number of autophagosomes

[131]. An elevated level of ubiquitin, an adaptor protein important for

autophagy, was also upregulated in L. major infection in BMDMs.

Interestingly, the autophagy was not mTOR-dependent; rather, hyperphosphorylation

of mTOR and ribosomal protein S6 was seen. This mTOR-independent autophagy was

verified by elevated levels of BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting

protein 3 (BNIP) in L. major infected cells [131]. BNIP is known to have

a role in autophagy-mediated elimination of L. major. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1

Despite several contradictory studies in Leishmania infected cells, it is evident that autophagy induction is important for survival. However, in-depth studies are needed on how autophagy is regulated during intracellular infection and how this contributes to microbial pathogenesis and influences host defence mechanism(s).

The literature review in this section represents accumulating evidence that host and pathogen non-coding RNAs play critical roles in the outcome of infection. The main focus is how Leishmania regulates macrophage non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and the associated RNA interference (RNAi) components to promote its survival.

For many years, scientists have focused on proteins as main effector molecules

used by pathogens. Recent progress in deep sequencing and other technologies has

revealed that the majority of the genome (90–95%) is transcribed to RNAs, which

are not translated into proteins. These RNAs are known as non-coding RNAs

(ncRNAs) and constitute about 90% of total cellular RNAs [135, 136, 137]. Based on

their size, ncRNAs can be classified into two groups: the small ncRNAs (

It is known that Leishmania modulates macrophage transcription to its

advantage. Previous studies have investigated global changes in gene expression

in several Leishmania-host cell models, including primary human

macrophages [154], patient’s lesions [155] and human and murine macrophage cells

[156, 157, 158, 159]. The majority of the above studies are related to transcripts that

encode proteins. However, due to recent advancements in RNAseq, the involvement

of ncRNAs in leishmaniasis has begun to emerge. The main focus of these studies

is restricted to host miRNAs [95, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164] playing roles during

Leishmania-macrophage interactions either favoring parasite survival or

enhancing effector functions against Leishmania persistence. For

instance, host miR-210 was upregulated during L. donovani infection of

macrophages, enhancing parasite survival by targeting p50 of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), leading to

attenuation of TNF

Regarding the role of host macrophage miRNAs as regulator of gene expression in cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) caused by L. braziliensis, there are three recent elegant studies. First study demonstrated that level of miR-361-3p and miR-140-3p were significantly elevated in CL lesions compared to normal skin from the same patient. Interestingly, miR-361-3p was correlated with failure of antimonial therapy and, consequently, longer healing time for cutaneous ulcers [168]. In another study, the expression of miRNAs related to the TLR/NF-kB pathway in human macrophages infected with Leishmania isolates from three clinical forms of disease caused by L. braziliensis: cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucosal (ML) and disseminated (DL) leishmaniasis was investigated. Interestingly, significant differential expression of miRNAs in macrophages infected with Leishmania isolated from ML and DL forms of leishmaniasis was observed. Some of these miRNAs were found to be correlated with parasite loads [169]. In a more recent focused study, same group investigated the functional role of miR-155a-5p in CL pathogenesis caused by L. braziliensis. They showed that miR-155a-5p is correlated with increased ROS and impaired apoptosis in human macrophages infected with L. braziliensis. Together, this study suggests a role of host miR-155 in regulating ROS production and apoptosis [170] in leishmaniasis.

Recently, our group demonstrated that L. donovani downregulated a broad subset of miRNAs in human primary macrophages [162]. This Leishmania-mediated miRNA inhibition occurred at the level miRNA gene transcription and was transcription factor c-Myc-dependent. c-Myc itself was upregulated markedly by infection, and inhibition of c-Myc activity, either by using a specific inhibitor (10058-F4) or downregulation by short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), restored macrophage miRNA levels to normal. Moreover, and of special interest in terms of infection biology, c-Myc silencing also brought about a dramatic reduction (approximately 90%) in the intracellular survival of Leishmania. Taken together, this investigation found c-Myc not only acts to bring about genome-wide repression of host miRNAs but also plays an essential role in promoting Leishmania survival. This identifies c-Myc as a novel virulence factor by proxy, contributing to Leishmania pathogenesis. Thus, this study identified one mechanism of how the miRNA machinery is targeted during Leishmania infection [162]. It will be of interest to extend this study since identification of c-Myc sensitive factor(s) in infected cells will have potential to be developed as novel therapeutic targets for leishmaniasis. In addition to the role of miRNAs in Leishmania pathogenesis, the role of long ncRNAs has begun to emerge. A recent study has implicated long ncRNAs in regulating macrophage functions [171]. This study has shown that the repression of 7SL RNA promotes a pro-parasitic environment.

There is a lack of information about the contribution of pathogen-related ncRNAs to host immune evasion and disease outcomes. An in-depth analysis of the L. major genome has revealed 1884 unique ncRNAs in the parasite [172]. The contribution of these parasite-derived ncRNAs to the outcome of parasite-host interactions needs to be investigated. As discussed above, ncRNAs need to be loaded onto Ago proteins to perform their function in RNAi. Leishmania seems to target this important class of molecules to regulate host RNAi.

RNAi is a conserved biological response to endogenous/exogenous double-stranded RNA that regulates the expression of protein-coding genes in a wide variety of organisms, including plants, animals and fungi [173, 174, 175]. In most cases, double-stranded RNA is diced into small fragments, approximately 21–25 base pairs, by Drosha and Dicer. These tiny fragments of double-stranded RNAs bind to Argonaute proteins, an integral constituent of effector complex RISC. Double-stranded sncRNA unwinds during RISC assembly, followed by the degradation of one strand (known as passenger strand). The remaining mature/guide strand hybridizes with a complementary mRNA, leading to either slicing of mRNA or translation inhibition due to RISC stuck on the target mRNA [173].

AGO proteins are central components of RISC in addition to sncRNAs and/or accessory proteins directly or indirectly interacting with them. This includes glycine/tryptophan repeat-containing 182 protein (GW182 protein), and heat shock proteins (HSP70/HSP90), among others [176, 177, 178, 179]. GW182 is a vital scaffolding protein that directly binds to Ago proteins and bridges its interaction with additional factors that coordinate all downstream steps of RNAi [177].

Humans have four AGO proteins, AGO1-4, which share a high sequence identity [180]. Despite sharing the same catalytic (Asp-Glu-Asp-His) tetrad, only AGO2 has been shown to possess slicing activity when the target mRNA sequence has complete complementarity to the guide sncRNA strand [181, 182]. All four AGO proteins have four distinct domains: N-terminal, Piwi-Argonaute-Zwille (PAZ), Middlle (MID) and P-element induced wimpy testis (PIWI) domain [183, 184]. AGO proteins have a bilobed configuration connected by Linker 1 and Linker 2 involved in structural rearrangements after binding to sncRNAs. A recent review nicely describes common features and target specificities across the four AGO proteins [180].

It is known that the majority of AGO functions are restricted to cytoplasm. However, several recent studies have reported non-canonical functions of the AGO proteins in the nucleus, where they remodelled chromosomes, and played roles in alternate splicing and DNA repair processes [185, 186, 187]. Thus, eukaryotic AGO proteins have a spectrum of functions involving many cellular processes. In recent years, AGO proteins have been implicated in several human diseases, such as viral infections, autoimmune diseases, cancer, neuronal diseases and metabolic deficiencies as reviewed by Pantazopoulou et al. [188]. Thus, evidence has emerged showing the role of AGO proteins in both physiological and pathological conditions.

As described above, several studies have implicated macrophage miRNAs in the pathogenesis of Leishmania infection. However, the role of AGO proteins in Leishmania infection and disease outcome has begun to emerge. Recently, our group showed the selective involvement of macrophage AGO1 in the survival of Leishmania in infected cells [189]. Leishmania infection selectively upregulated the abundance of macrophage AGO1 in infected cells. Interestingly, an increased level of AGO1 in infected cells positively correlated with the enhanced level of AGO1 in functional RISC, indicating a preference for AGO1 in regulating RNAi in infected cells. In virus-infected mammalian cells, it has recently been shown that sncRNAs other than miRNAs were selectively loaded onto AGO1 but not AGO2 [190]. Similarly, in Drosophila, it has been demonstrated that perfectly matched sncRNA duplexes are loaded onto AGO2, whereas non-perfectly matched sncRNAs are loaded onto AGO1 [191]. Deliberate knock down of AGO1 using siRNAs attenuated Leishmania survival in infected cells. Moreover, the expression of several Leishmania pathogenesis-related proteins seems to be dependent on the optimal level of AGO1 [189]. Interestingly, 53 of the 71 proteins are related to the pathogenesis of other intracellular pathogens [189]. This study could provide a framework for further analysis of the role of RNAi in Leishmania pathogenesis in humans (Fig. 5). A deep understanding of inter-species RNAi in the context of Leishmania infection could offer novel therapeutic strategies to control and treat leishmaniasis and may have implications for other intracellular pathogens. We note that this research is restricted to proteomic analysis, and it will be of interest to complement these findings with relevant biological assays. Further, identification and characterization of Leishmania ncRNAs and their host targets and host ncRNAs relevant to leishmaniasis could add to the molecular understanding of Leishmania pathogenesis.

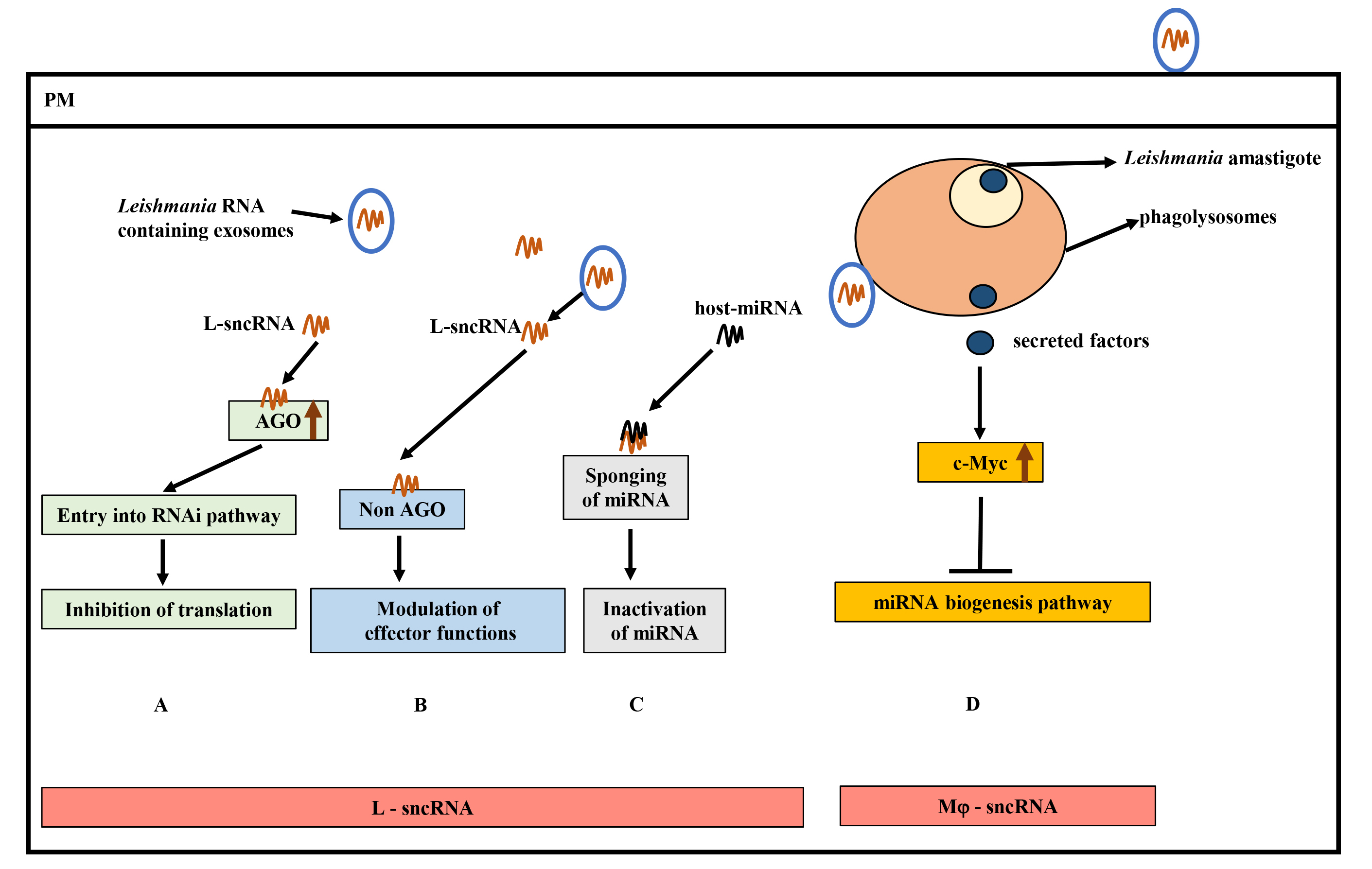

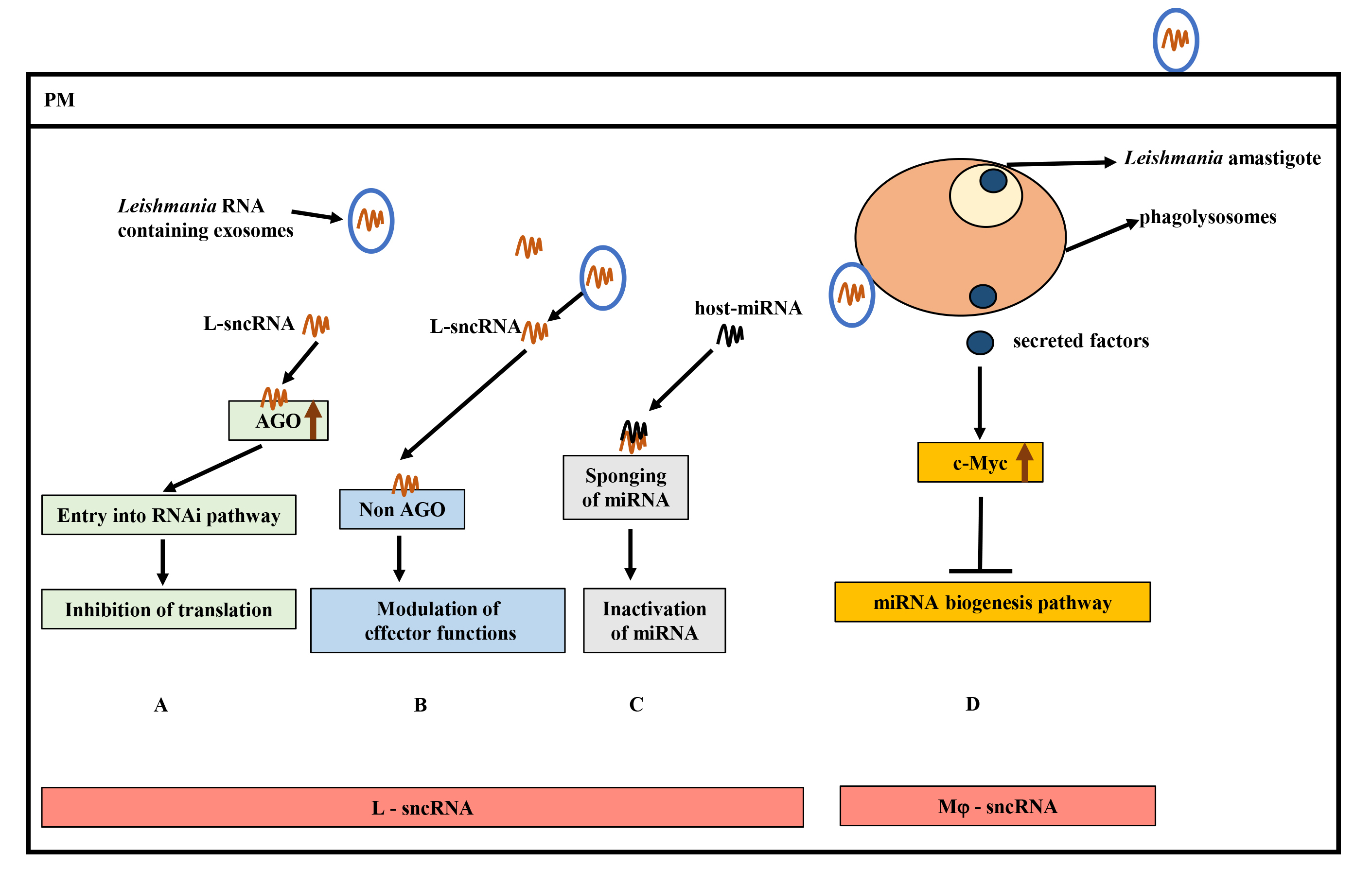

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Hypothetical model of small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) and contributions to Leishmania pathogenesis. (A) Hijacking of host RNA interference (RNAi) pathway by Leishmania sncRNAs (L-sRNA) by interacting with host Ago proteins (critical component of RNA Induced Silencing Complex (RISC)) to inhibit translation. (B) Binding of L-sncRNA to host non-AGO proteins, leading to modulation of host effector functions. (C) Inactivation of host-microRNA (miRNA) function by L-sncRNAs by complementary base-pairing. (D) Inhibition of host miRNA expression by Leishmania secreted effectors by upregulating c-Myc levels. Increased c-Myc levels target the miRNA biogenesis pathway at the transcription level. AGO, Argonaute; miRNA, MicroRNA.

Given the knowledge summarized in this review, it is clear that leishmaniasis provides an excellent paradigm of immune evasion in several ways. Over the years, we have learned that Leishmania has evolved to acquire the ability to regulate the cell biology of its host macrophages through complex mechanisms to reside, grow and proliferate inside inhospitable and restricted environment of parasitophorous vacuoles (PVs) of infected cells. The evasion strategies include inhibition of apoptosis, regulation of host autophagy and targeting of host ncRNAs. Exploitation of macrophage autophagy and RNAi are emerging themes in many intracellular pathogens, including Leishmania. The role of host ncRNAs during Leishmania infection is mainly restricted to miRNAs. There is a need to investigate the role of other ncRNAs during Leishmania infection. In RNAi, how Leishmania targets RISC to regulate host gene expression is an important question that needs to be answered. The molecular and functional characterization of virulence factors and investigating their effects on host ncRNAs and autophagy is likely to provide new insights into pathogenesis. This knowledge could be the key to identifying new targets for intervention to combat and prevent leishmaniasis. We note that host immune response and Leishmania pathogenesis are highly variable and influenced by infecting Leishmania species, their virulence factors and choice of the host. Extension of current knowledge of Leishmania-macrophage interactions with all diseases causing Leishmania species will be very helpful in designing new approaches to this neglected disease.

DN and HKB were involved in planning and collecting the data for this review and drafting/editing the manuscript. NR was involved in the conceptualization, interpretation of data, fund acquisition, and critical review of figures. NR planned and acquired the funding. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

We thank Dilraj Longowal for her assistance in making figures, Atieh Moradimotlagh and Fabian Chang for reviewing the manuscript critically.

The funding for this review was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2018-04991) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (PJT-162191) awarded to NR.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.