1 Department of Cardiac Surgery, Hainan General Hospital (Hainan Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University), 570311 Haikou, Hainan, China

2 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Ezhou Central Hospital, 436000 Ezhou, Hubei, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Being one of the pivotal adipocytokines, adiponectin binds to various receptors and exerts diverse biological functions, encompassing anti-fibrosis, anti-atherosclerosis, anti-ischemia-reperfusion, regulation of inflammation, and modulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Alterations in adiponectin levels are observed in patients afflicted with diverse cardiovascular diseases. This paper comprehensively reviews the impact of adiponectin on the pathogenesis and progression of cardiovascular diseases, elucidating the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms along with the associated cell signaling pathways. Furthermore, it deliberates on the diagnostic and predictive efficacy of adiponectin as a protein marker for cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, it outlines methods for manipulating adiponectin levels in vivo. A thorough understanding of these interconnections can potentially inform clinical strategies for the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords

- adiponectin

- cardiovascular disease

- endocrine system

- cell signaling

With advancements in medical treatments, infectious diseases are no longer the primary threats to human survival. In recent years, cardiovascular diseases have emerged as the most significant health challenges, particularly for middle-aged and elderly populations. Moreover, the risk of adverse cardiovascular events escalates with advancing age [1, 2, 3, 4]. In the past, adipose tissue was primarily viewed as an energy reservoir for metabolic processes. However, recent research has unveiled its significant secretory function. Adipose tissue secretes a multitude of hormones, thereby exerting diverse regulatory roles in biological metabolism. Among these, adiponectin emerges as a key adipokine released by adipocytes, also known as Acrp30, AdipoQ, APDN, and Adiponectin (APN). Studies have demonstrated its wide-ranging effects on various organs and tissues within the human body. Adiponectin is intricately linked to numerous chronic diseases, particularly playing a important role in the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease [5]. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adiponectin’s function in cardiovascular diseases is imperative to guide clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention strategies, aimed at mitigating the prevalence and mortality of associated conditions.

Discovered in 1995, adiponectin is a monomeric glycoprotein predominantly

secreted by adipocytes [6]. Notably, women tend to have higher average

adiponectin levels compared to men, possibly attributed to the influence of

estrogen on adipocyte function [7, 8]. Adiponectin is mainly secreted by

adipocytes, and the level of adiponectin in obese individuals is significantly

lower than that in non-obese individuals. The adiponectin molecular structure is

composed of 244 amino acids, including an N-terminal signal sequence,

non-homologous or hypervariable region and collagen domain, and a C1Q-like

globular domain at the C-terminal [9, 10, 11, 12]. Following translation,

intracellular adiponectin undergoes intricate processing and modification within

the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, giving rise to three distinct

molecular weight forms: low molecular weight adiponectin (LMW), medium molecular

weight adiponectin (MMW), and high molecular weight adiponectin (HMW).

Subsequently, adiponectin binds to Golgi-localizing

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the three adiponectin species with different molecular weights. (A) corresponds to LMW, (B) to MMW, (C) to HMW, (D) to G-ad. LMW, low molecular weight; MMW, medium molecular weight; HMW, high molecular weight.

The adiponectin gene, spanning approximately 15.8 kb, comprises three exons located on chromosome 3q27 [14]. Two polymorphisms within the adiponectin gene, +45T/G and 276G/T (rs1501299), have been independently linked to an elevated risk of metabolic diseases and obesity [15]. However, the rs1501299 polymorphism does not appear to be associated with the risk of atherosclerosis [16].

APN is released from adipocytes either in a paracrine or endocrine manner, with high molecular weight (HMW) APN predominating as the principal active form in circulation. HMW APN exhibits significantly higher anti-atherosclerotic and insulin-sensitizing properties compared to the other two forms [17, 18]. Atherosclerosis is the primary cause of malignant cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Anti-atherosclerotic therapy can reduce the deposition of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) within the vascular intima, decrease the production of oxidized LDL, and diminish vascular intimal thickening. This not only lowers the incidence of cardiovascular diseases but also slows the progression of associated vascular lesions, thereby reducing the occurrence of malignant events related to these diseases [19, 20].

Insulin sensitization promotes the optimal utilization of insulin, enhances the body’s ability to utilize and convert glucose, corrects insulin resistance in diabetic patients, reduces intra-body glucose levels, and consequently alleviates the chronic vascular damage caused by inflammation due to dysregulated glucose and lipid metabolism [21].

Collectively, the three forms of APN, interconnected by the globular and gelatinous domains, are referred to as full-length adiponectin (f-APN).

Additionally, another biologically active form of APN, termed globular adiponectin (g-APN), has been identified in circulation. The existence of g-APN was initially reported by Fruebis et al. [22].

Although there remains ambiguity regarding its production mechanism. Some researchers have employed trypsin or leukocyte elastase to hydrolyze f-APN in vitro, yielding hydrolyzed fragments with effects akin to g-APN [22, 23]. Furthermore, speculation persists that in vivo, f-APN may also undergo decomposition by these proteases. However, recent studies have elucidated that thrombin mediates the cleavage of f-APN between Arg-92 and Gly-93, converting it into g-APN in a Ca2+-dependent manner, thus refuting the notion of trypsin or leukocyte elastase mediation in vivo [24]. This study also utilized a modified form of f-APN (m-APN), which remains unconverted into g-APN in circulation but retains the ability to activate f-APN-related receptors. Such an approach effectively eliminates confounding factors associated with lipid and glucose metabolism, providing a novel avenue for future research. It is imperative for forthcoming experiments to explore whether interventions preventing the conversion of f-APN to g-APN can minimize experimental errors and enhance accuracy. Recent investigations have revealed the ability of various cell types, including cardiomyocytes, cardiac stromal cells, vascular endothelial cells, and skeletal muscle cells, to secrete APN [5, 25, 26, 27].

As the predominant adipokine in plasma, adiponectin (APN) orchestrates cellular signaling alterations across various pathways by engaging with its receptors, thereby eliciting diverse biological responses. These encompass anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-atherosclerotic effects, alongside enhancements in glucose and lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Particularly notable are its profound cardiovascular protective effects mediated through multiple mechanisms [28, 29, 30]. Refer to Fig. 2 for details. However, numerous studies have suggested that APN may not solely exert protective effects but could also serve as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality. In a high-risk cohort comprising 325 individuals, APN levels were found to correlate with individual mortality [31, 32].

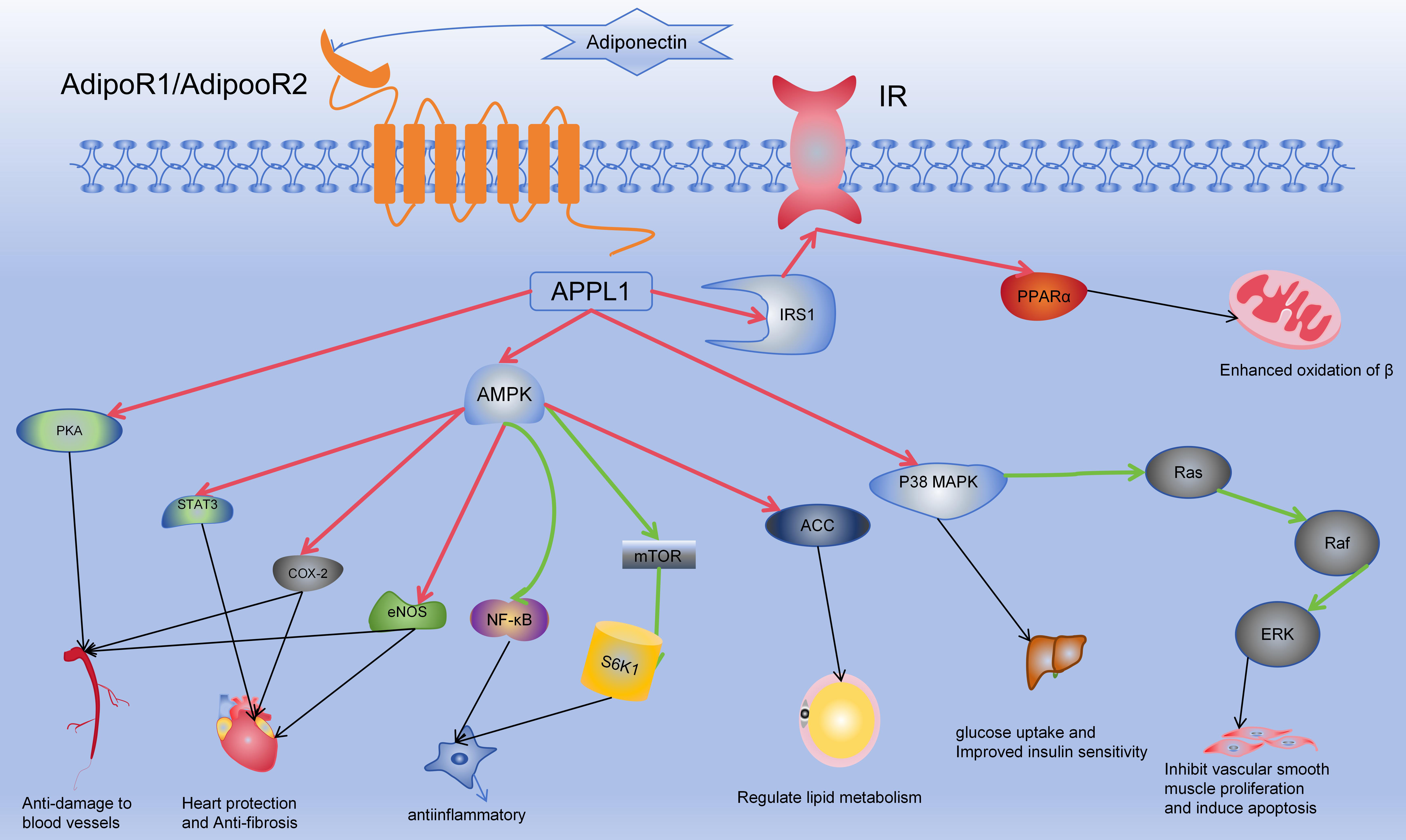

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of action of adiponectin. In the Fig. 2, red arrows

indicate activation, green arrows signify inhibition, and black arrows depict

subsequent effects on target organs and cells. Adiponectin binds to the

extracellular domains of AdipoR1/AdipoR2, activating their intracellular

segments. This activation involves APPL1, which subsequently influences

downstream targets such as AMPK, p38 MAPK, PPAR

There exist three recognized types of adiponectin (APN) receptors: adiponectin

receptor 1 (AdipoR1), adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2), and T-cadherin [33, 34].

Binding of APN to AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 initiates downstream effects through

adenylate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-alpha (PPAR

APPL1 was the first identified protein to directly interact with APN receptors, activated by the intracellular domain of APN receptors to further modulate APN function via related signaling pathways and regulate insulin sensitivity. APPL2, sharing similarity with APPL1, serves as a negative regulator of APN signaling by competitively binding to APN receptors [39, 40, 41, 42].

Adiponectin (APN) is intricately associated with cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and diabetes [30, 43, 44, 45, 46]. Changes in adiponectin levels are observed in correlation with these diseases, as depicted in Table 1. Consequently, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying APN’s actions is crucial for understanding its role in disease onset and progression. Such insights can guide the development of clinical strategies aimed at preventing, managing, and treating these conditions, ultimately reducing their prevalence and mortality.

| Abnormal condition | Adiponectin content changes |

| Atherosclerosis | Reduce |

| Diabetes | Reduce |

| Heart failure | Increase |

| Obesity | Reduce |

| Pulmonary artery hypertension | Increase |

| Hypertension | Reduce |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Increase |

Adiponectin’s main active region is located in the globular domain at its

C-terminus. AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 are membrane receptors with seven transmembrane

regions, with their C-termini located on the extracellular side of the cell

membrane and their N-termini on the intracellular side [42]. When adiponectin

reaches the cell membrane of its target cell, the globular domain of adiponectin

binds to the C-terminus of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2, activating the adiponectin

receptor, thereby allowing its N-terminus to bind to APPL1 and subsequently

activate downstream cellular signaling pathways. It is worth noting that upon

activation, APPL1 not only functions through pathways such as AMPK/MAPK but also

through the insulin receptor. In its basal state, APPL1 forms a complex with

insulin receptor substrate proteins 1 and 2 (IRS1/2). When insulin stimulates the

activation of APPL1, phosphorylation of its Ser401 residue regulates its

binding to insulin receptor subunit

Macrophages are categorized into two distinct types: M1 and M2, which exhibit

contrasting characteristics. M1 macrophages are capable of producing various

pro-inflammatory factors such as Interleukin- 6 (IL-6), Tumor necrosis factor-

However, conflicting views exist regarding the anti-inflammatory effects of

adiponectin. Recent studies have unveiled distinct effects of full-length

adiponectin (f-APN) and globular adiponectin (g-APN) on macrophages. Culturing

mouse macrophage Raw264.7 cells with g-APN revealed an increase in

pro-inflammatory factors such as Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), IL-6, TNF-

Inflammation is a significant factor contributing to the occurrence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, which are leading causes of mortality worldwide [55]. Low-grade chronic inflammation also increases the risk of atherosclerosis and insulin resistance, which are primary mechanisms in the development of cardiovascular diseases. One of the mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis is the gradual development of vascular damage due to chronic inflammatory lesions [56]. The anti-inflammatory effects of adiponectin reduce the overall or local levels of inflammatory factors in the body, alleviate vascular microenvironmental changes caused by chronic inflammatory damage, enhance cardiovascular resistance to injury, and reduce the risk of developing coronary atherosclerosis.

Additional studies have revealed that adiponectin (APN) inhibits lipid accumulation in macrophages through the docking proteins AdipoR1, AdipoR2, and APPL1, while also regulating scavenger receptor-AI and associated inflammation via AdipoR1 and AdipoR2. This action impedes macrophage transformation into foam cells, thereby imparting anti-atherosclerotic effects [35, 36, 57].

Elevated levels of heat shock protein 60 (HSP 60) have been observed in patients

with atherosclerosis [58]. HSP 60 can modulate cellular activity across various

tissues, influencing pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-1

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) serves as a downstream effector of the AMPK signaling pathway, playing pivotal roles in cell growth, differentiation, and proliferation. However, AMPK activation negatively regulates mTOR expression. In a recent study, APN-treated mice exhibited significantly higher levels of AMPK compared to sepsis-induced mice, while mTOR levels were notably reduced [59]. APN inhibited mTOR activity, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory and anti-injury effects. Similarly, S6K1 has been identified as a critical downstream effector of the mTOR signaling pathway, regulating APN expression through direct binding to promoters and histone crosstalk [60]. Hence, the mTOR signaling pathway may serve as a conduit for adiponectin-mediated regulation of inflammation and macrophage functions.

Adiponectin activates the AMPK-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (AMPK-eNOS)

pathway in endothelial cells, thereby modulating endothelial cell function and

the vascular microenvironment. This process may involve selective

phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) mediation [5]. Furthermore, the upregulation of

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and eNOS activity enhances nitric oxide (NO) production, promoting

endothelial cell relaxation, reducing the risk of vascular plaque formation and

endothelial cell apoptosis, and improving vascular endothelial function.

Moreover, enhanced nitric oxide production suppresses the secretion of related

inflammatory factors and mitigates the damage caused by reactive oxygen species

(ROS) to endothelial cells. Adiponectin can also activate the cAMP-PKA signaling

pathway to stimulate nitric oxide production, inhibit ROS-mediated endothelial

cell damage, suppress the NF-

Perivascular adipose tissue serves as a critical modulator of vascular function.

It releases nitric oxide (NO) to regulate endothelial vasodilation, thereby

improving the vascular microenvironment and reducing endothelial cell death.

Additionally, it releases various adipokines that further regulate endothelial

constriction and dilation. For instance, activation of adipocyte

Adiponectin activates AMPK-dependent STAT3 by phosphorylating the Tyr705 locus of AMPK, thus reducing ROS production and exerting anti-ischemic perfusion effects [63]. Additionally, it can confer cardiovascular protective effects via non-AMPK-dependent pathways, with ischemic postconditioning (IPO) serving as a significant mechanism.

A pivotal process in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis involves the translocation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) to the intimal layer of the blood vessel wall, subsequent phagocytosis of lipids deposited beneath the arterial intima, foam cell formation, necrosis, and fibrosis, ultimately culminating in arteriosclerosis. With disease progression, plaques gradually enlarge, narrowing the blood vessel lumen, rendering the affected vessels increasingly susceptible to damage. Moreover, plaque rupture can trigger platelet aggregation and thrombosis. Adiponectin attenuates the secretion of various cytokines, thereby impeding the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells, exerting anti-atherosclerotic effects [64]. Furthermore, adiponectin mitigates hyperglycemia-induced premature aging in VSMCs by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway and activating the AMPK/TSC2/mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway. Additionally, it enhances telomerase activity in VSMCs to delay senescence [65].

Adiponectin protects spiral modiolar artery smooth muscle cells not only by modulating superoxide dismutase activity and malondialdehyde levels, but also by regulating the expression of Bcl-2, Bax, and cleaved caspase-3. This protective process can be inhibited by AMPK inhibitors, highlighting the critical role of the AMPK signaling pathway in adiponectin-mediated smooth muscle cell protection [66]. Globular adiponectin significantly attenuates apoptosis and vascular calcification both in vitro and in vivo, partly through inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress in vascular smooth muscle cells and decelerating the vascular calcification process [67]. Adiponectin concentration-dependently modulates mitofusin-2 (MFN2) expression, inhibiting the Ras-Raf-Erk1/2 signaling pathway, thereby suppressing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis, ultimately contributing to anti-atherosclerotic effects [68].

Fibrosis represents an end-stage pathological response to diverse injuries

affecting tissues, organs, and cells. During acute or chronic tissue injury,

fibroblast activation is often promoted, leading to fibrosis of associated organs

and tissues. The signaling pathways implicated in fibrosis include AMPK,

TGF-

To investigate the potential regulatory effect of adiponectin on fibrosis,

studies have demonstrated that adiponectin can inhibit lung fibroblast activity

by modulating the nuclear factor

Studies injecting adiponectin into mice with simulated myocardial hypertrophy

have revealed significant reductions in cardiomyocyte size, mRNA expression of

myocardial hypertrophy genes, and improvements in myocardial fibrosis, with the

AMPK pathway appearing to be involved in enhancing diastolic function [75].

Additionally, in cardiomyocytes, adiponectin mitigated diabetes-induced

activation of the TGF-

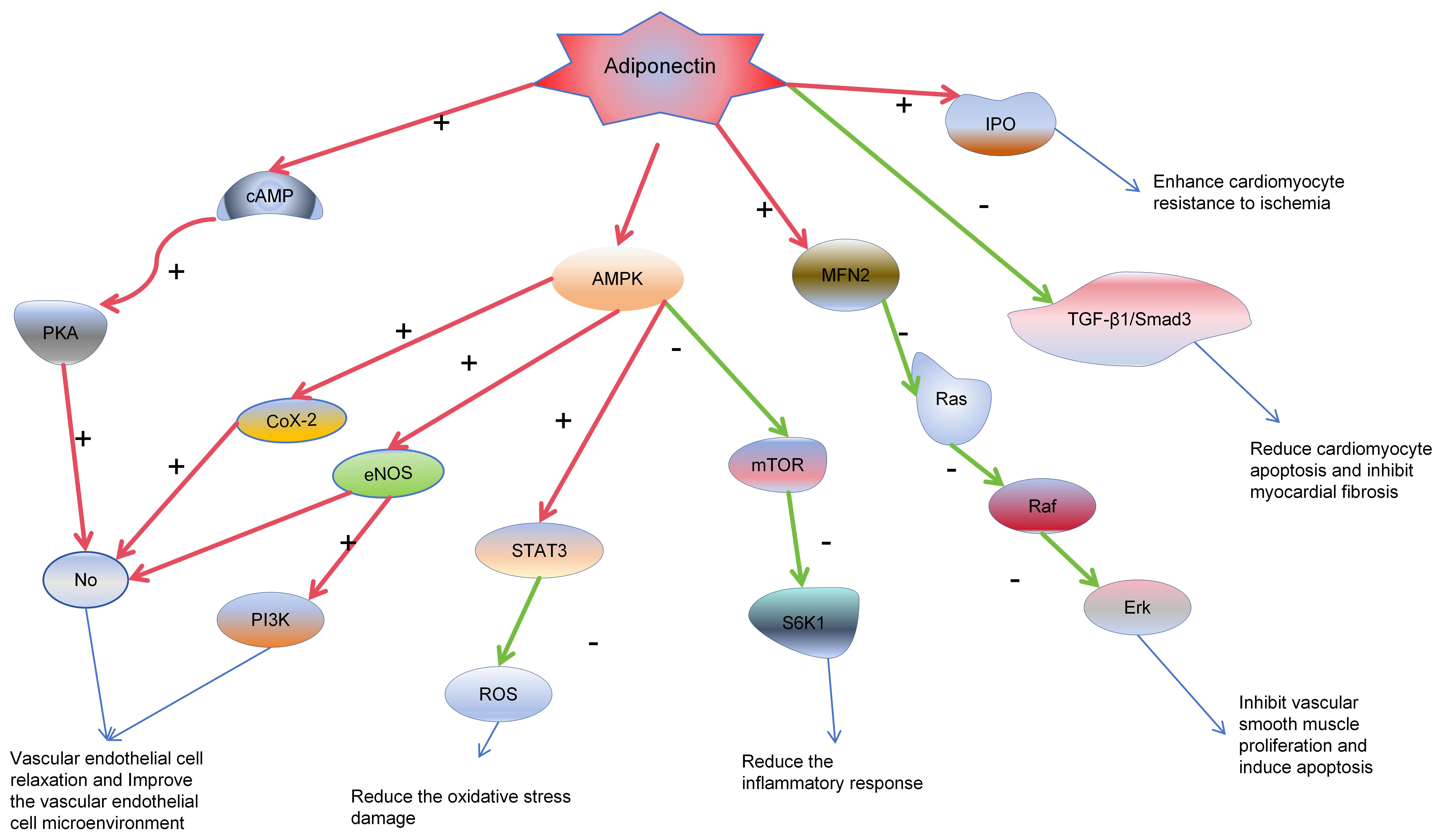

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Adiponectin cardiovascular protective mechanisms. In the

diagram, red arrows indicate activation, green arrows signify inhibition, and

blue arrows represent subsequent effects on target organs and cells. Adiponectin

triggers the release of nitric oxide (NO) from vascular endothelial cells through

the AMPK/PKA/Ras-Raf-Erk pathway, enhancing the microenvironment of endothelial

cells. This effect reduces the proliferation of endothelial cells, induces

apoptosis, and thus contributes to anti-atherogenic effects. Moreover,

adiponectin lowers the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reducing

damage to endothelial cells. In cardiomyocytes, it dampens inflammatory

responses, alleviates damage following myocardial ischemia, and minimizes

myocardial death and fibrosis through the TGF-

The decline in circulating adiponectin levels correlates strongly with increased oxidative stress [77]. Moreover, the inverse association between adiponectin levels and the risk of myocardial ischemia suggests its contribution to antioxidative stress mechanisms [78]. Shibata et al. [79] reported decreased adiponectin levels in the plasma and heart tissue of mice subjected to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Following adiponectin injection in adiponectin knockout (APN-KO) mice, a reduction in myocardial infarction area was observed, indicating adiponectin’s inhibitory effect on ischemia-reperfusion injury. Furthermore, a study involving animals subjected to double reperfusion after 30 minutes of myocardial ischemia demonstrated that adiponectin treatment prior to reperfusion reduced ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial iNOS protein expression [78]. This process led to decreased nitric oxide and superoxide release, thereby inhibiting peroxynitrite synthesis and reducing myocardial infarction, ultimately exerting a protective role in myocardial preservation. Additionally, adiponectin can mitigate cardiomyocyte apoptosis through the AMPK pathway, thereby preserving cardiomyocyte numbers [80].

Recent studies indicate that in diabetic mice with adiponectin deficiency, following ischemia-reperfusion, there is an upregulation of miR-449b in the heart. This upregulation leads to an increase in superoxide production, which in turn enlarges the myocardial infarction area. Additionally, miR-449b inhibits the expression of the antioxidant genes Nrf-1 and Ucp3. However, this phenomenon is not observed in non-diabetic mice [81].

Adiponectin has been shown to reduce platelet aggregation [82, 83]. However,

globular adiponectin (g-ad) serves as a novel ligand for the collagen receptor

GPVI, promoting platelet adhesion and aggregation [84]. g-ad induces pro-platelet

aggregation and secretion effects by activating integrin

In skeletal muscle, adiponectin (APN) primarily functions via its globular form (g-ad) due to its high affinity for AdipoR1, the predominant APN receptor expressed in skeletal muscles. APN enhances glucose uptake and utilization through the AMPK pathway, contributing to reduced blood glucose levels [85]. Furthermore, the AMPK pathway is partially activated by liver kinase B1 (LKB1), an upstream regulator of AMPK. Recent research demonstrated that LKB1 knockout partially attenuated the hypoglycemic effect of APN. APN exerts its effects on blood glucose regulation by inhibiting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, primarily by downregulating the activity of key enzymes involved in glucose metabolism in the liver, such as glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase [10, 86, 87, 88]. Additionally, APN may decrease gluconeogenic substrates, thereby reducing gluconeogenesis and overall glucose content in the body [89].

Insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) plays a crucial role in insulin-mediated glucose uptake. APN can directly influence IRS-1 and promote glucose uptake, potentially contributing to enhanced insulin sensitivity [90]. The synergistic effect of adiponectin and insulin sensitivity may also involve ALY688, a process closely associated with increased levels of insulin-stimulated Akt and IRS-1 phosphorylation [91].

Abnormalities in glucose metabolism often indicate a decrease in the body’s ability to utilize glucose, frequently accompanied by the occurrence of insulin resistance. In a state of insulin resistance, the body exhibits hyperinsulinemia and elevated blood glucose levels in the circulation. Currently, the mechanisms underlying the mutual promotion of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases are not fully understood. However, it is certain that the incidence of cardiovascular diseases increases by 2–10 times in individuals with diabetes. Moreover, the prognosis is poorer and the risk of adverse events is higher when cardiovascular diseases occur in individuals already suffering from diabetes [92]. Speculations suggest that this situation may be related to the stimulation of chronic inflammation in the body under conditions of high blood sugar.

The content of adiponectin is inversely related to the degree of obesity [93].

While obesity often correlates with decreased adiponectin levels in the body, it

has been observed that in the state of obesity, there is a barrier to the

clearance of adiponectin, suggesting that the decrease in adiponectin may be

attributed to reduced production [94]. Consequently, increasing circulating

adiponectin expression can mitigate food-induced obesity development in mice

[95]. Likewise, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels exhibit a

positive correlation with adiponectin levels [96, 97, 98], indicating a potential

close association with lipid metabolism. Adiponectin enhances the transcriptional

expression of fatty acid transporter 4 and fatty acid-binding proteins by

activating AMPK signaling. This activation promotes

Recent studies highlight distinct effects of full-length adiponectin (f-ad) and

globular adiponectin (g-ad) on lipid processing and glucose metabolism in obese

individuals. While g-ad may promote adipocyte hypertrophy, this effect has not

been observed with f-ad [24]. G-ad may deactivate acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) by

stimulating 5

Reverse cholesterol transport is a pivotal pathway in atherosclerosis prevention in vivo [101]. HDL facilitates the transport of cholesterol back to the liver via ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and scavenger receptor pathways, enhancing cholesterol efflux from foam cells. Adiponectin deficiency in mice leads to reduced Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1)-mediated cholesterol efflux and ABCA1 expression in macrophages. Conversely, adiponectin treatment increases ApoA1-mediated cholesterol efflux in mouse macrophages, potentially dependent on ABCA1 [101]. Adiponectin upregulates ABCA1 receptor expression in human macrophages, bolstering ApoA1-mediated cholesterol efflux, elevating HDL levels [10], facilitating reverse cholesterol transport, and reducing lipid deposition. Additionally, it enhances the catabolism of high triglyceride-containing lipoproteins, consequently lowering serum triglyceride levels [102].

In recent years, there has been evidence of interaction between adiponectin and HDL. Levels of adiponectin and HDL-C are positively correlated in serum. Additionally, it has been found that in adults, the capacity for high-density lipoprotein cholesterol efflux is positively correlated with HDL-C, apoA1, and serum adiponectin levels [103]. Adiponectin can stimulate the production of HDL, facilitating cholesterol efflux and thus reducing cholesterol deposition within the vascular wall. This inhibition of atherosclerosis occurrence protects the cardiovascular system. Adiponectin maintains the quantity and function of HDLs relatively stable by preventing the accumulation of triglycerides (TG) in HDL [104].

Disruptions in lipid metabolism are closely related to cardiovascular diseases. Atherosclerosis occurs when lipids deposit beneath the vascular endothelium, leading to the formation and progression of foam cells through the engulfment by macrophages and smooth muscle cells. Lipid metabolism abnormalities often accompany elevated LDL and reduced HDL levels, or elevated cholesterol or triglycerides. Lipid deposition within the vasculature, coupled with endothelial dysfunction caused by chronic inflammation, increases the susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases [105]. Research has found a correlation between atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemia [106]. Therefore, adiponectin can effectively regulate relevant lipoproteins, cholesterol levels, and triglyceride levels, promoting cholesterol excretion, stimulating HDL production, and enhancing HDL-mediated reverse cholesterol transport. This can effectively reduce lipid deposition in the vessel walls and inhibit the development of atherosclerosis.

Although adiponectin has numerous protective effects, elevated plasma adiponectin levels are not always beneficial to the cardiovascular system. Moreover, high adiponectin levels have been reported in patients with stable angina causing heart failure or death [107, 108]. Similarly, adiponectin levels showed a positive correlation with disease severity in patients with heart failure. In addition, higher adiponectin levels often represent a poor prognosis in heart failure [46, 109]. Increased adiponectin expression is also observed in patients with other advanced cardiovascular diseases. This is the opposite of the “protective role” of adiponectin, which is the “adiponectin paradox”.

At present, it is not possible to explain the cause of the adiponectin paradox, It is hypothesized that when the body is severely damaged, cells could over-secrete adiponectin to protect the body, to resist intense inflammatory damage, to protect the function of organs and cells in the body, and prevent excessive cell damage and mass cell death. In addition, does the multi-organ dysfunction or multi-organ failure caused by the later stage of cardiovascular disease interfere with the adiponectin metabolism, resulting in impaired excretion of adiponectin, resulting in hyperadiponectinemia? The appeals are conjecture and have not been confirmed, the reasons for which need to be further explored.

Changes related to adiponectin content have also been found in diseases other than cardiovascular disease. High adiponectin levels have also been found in inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), chronic kidney disease, and other diseases [42, 110, 111, 112], which possibly promote disease development and progression. Therefore, the role of adiponectin requires extensive analysis. This protein not only has a strong and recognized protective effect, but may also play a role in accelerating the development of certain diseases. However, related research has been slow and limited. Therefore, further research is needed to investigate the role of adiponectin in disease progression.

A notable reduction in adiponectin levels has been observed in patients with coronary atherosclerosis, prompting inquiry into its potential as a predictor of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. However, current research indicates that adiponectin has limited predictive utility for related diseases. The scarcity of studies specifically addressing the prediction of coronary heart disease by adiponectin has resulted in most investigations analyzing the blood of patients with associated conditions, rather than comprehensive analyses of adiponectin levels in larger populations, such as those undergoing routine physical examinations. Consequently, it raises the question of potential bias in the analysis results stemming from this discrepancy.

High levels of adiponectin have been detected in patients with advanced coronary artery disease (CAD) experiencing terminal events [43, 109]. Circulating adiponectin has been identified as an independent predictor of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [31]. However, the dual effect of adiponectin and the absence of a definitive explanation have hindered the progression of adiponectin’s predictive capability for coronary heart disease. Although controversial, it appears that adiponectin may forecast the risk of death in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease. In a prospective cohort study, elevated circulating adiponectin levels predicted heightened cardiovascular mortality in men, albeit not in women [113]. In high-risk cohorts, plasma adiponectin levels have shown promise in predicting the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality in men undergoing coronary angiography [32]. This prompts speculation about potential gender differences in adiponectin’s predictive ability for cardiovascular endpoints. However, the small sample size of phase studies necessitates further scrutiny to ascertain the accuracy of this conclusion.

Analysis of 106 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) revealed a negative correlation between adiponectin levels and left ventricular systolic function, alongside a positive correlation with Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) content. Adiponectin, in conjunction with BNP, may serve as a marker for assessing left ventricular damage severity in HCM patients [114].

In dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), there exists a correlation between adiponectin levels and mortality. Adiponectin could potentially predict heart failure development in later-stage DCM patients. Elevated adiponectin levels in the initial years often indicate a notably higher risk, with prognostic implications [115].

Higher adiponectin levels observed in patients with inflammatory cardiomyopathy typically signify reduced inflammation and a favorable prognosis. Similarly, elevated adiponectin levels in mice with autoimmune myocarditis have been associated with inflammation suppression. However, adiponectin has not been definitively established as a marker for inflammatory cardiomyopathy [116]. To date, no study has validated its role as a marker for this condition.

Elevated adiponectin levels may correlate positively with the risk of mortality from heart failure. Circulating adiponectin levels tend to rise with the severity of heart failure [109]. High circulating adiponectin levels often indicate a poorer prognosis in congestive heart failure patients. Adiponectin, when combined with pro-BNP, could serve as a predictor for overall mortality in congestive heart failure patients, and potentially as an independent prognostic indicator in this population [117].

The possible link between adiponectin and atrial fibrillation has been a subject of considerable study, albeit with inconclusive findings regarding their association [118]. High adiponectin levels have been detected in individuals with type 2 diabetes complicated by atrial fibrillation [119]. Additionally, studies have found that high baseline levels of adiponectin appear to be closely associated with the development of new-onset atrial fibrillation. High adiponectin levels may be an independent risk factor for the occurrence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during follow-up, particularly in follow-up observations exceeding 10 years [120]. However, the existing research on adiponectin and arrhythmias remains limited, and no significant relationship between adiponectin and atrial fibrillation has been firmly established.

In a prospective study, no significant disparity in adiponectin levels was observed among patients with aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction when compared to a control group. Furthermore, adiponectin levels were found to be influenced by the severity of coronary atherosclerosis, independent of aortic coarctation type [121].

Among patients with pulmonary hypertension, circulating adiponectin levels exhibited an inverse correlation with right ventricular function, suggesting a potential association with heart failure [122].

Currently, the literature exploring the correlation between adiponectin and cardiac conditions such as arrhythmias, aortic valve stenosis, and pulmonary hypertension is limited. Consequently, there is insufficient evidence to establish a definitive relationship between adiponectin and these cardiac disorders. In essence, Elevated levels of adiponectin are closely associated with subsequent adverse cardiovascular events in patients with underlying medical conditions. For instance, in individuals with diabetes or cardiovascular diseases, high adiponectin levels often indicate increased risk of mortality and higher mortality rates, as well as a positive correlation with the occurrence of heart failure [123]. Moreover, as adiponectin levels can fluctuate in numerous diseases and given its diverse biological effects, its predictive value for specific diseases may be limited. However, this also implies that adiponectin holds promise as a broad-spectrum predictor of diseases. Future research could explore whether combining adiponectin with other predictive markers enhances the accuracy of disease prediction, facilitating early prevention and intervention strategies. Understanding the mechanisms underlying adiponectin’s actions is crucial for maximizing its utility in predicting disease outcomes.

Adiponectin levels are associated with a variety of diseases. In the face of so many adiponectin related diseases, people are also exploring to regulate the content of adiponectin through intervention measures in the condition of disease or bad state. Table 2 shows how adiponectin levels are changed.

| Means of intervention | Possible mechanism | |

| Lifestyle regulation | ||

| Calorie-controlled diet | Weight loss | |

| Kinesitherapy | Weight loss | |

| Medication | ||

| Statins | Simvastatin, Rosuvastatin | HDL increased |

| LDL decreased | ||

| Fibrate | HDL increased | |

| LDL decreased | ||

| Thiazolidinediones | Rosiglitazone, Pioglitazone | Increased expression after transcription insulin sensitization |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | Liraglutide | Regulates Sirt1 and transcription factor Foxo-1 |

| Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors | Ipragliflozin, Dapagliflozin | Weight loss, insulin sensitization |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Temocapril, Ramipril | Reduce inflammation insulin sensitization |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | Valsartan, Candesartan, Losartan | Reduce inflammation insulin sensitization |

| Surgery | Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass | Weight loss, HDL increased |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; Sirt1, silent information regulator sirtuin 1; Foxo-1, forkhead box O1.

After implementing a caloric restriction diet, adiponectin levels were observed to increase, leading to improved insulin sensitivity and enhanced glucose metabolism tolerance. However, it was noted that the lifespan of APN-KO mice was significantly shortened [124]. This suggests that caloric restriction plays a vital role in elevating adiponectin concentrations. In a 12-week randomized intervention study involving 79 obese subjects randomly assigned to exercise, caloric restriction, or a combination of both, increased adiponectin mRNA expression and adiponectin levels were observed [125]. Additionally, engaging in aerobic exercise 2–3 times per week for 60 minutes each session resulted in a significant increase in adiponectin concentration and improved insulin sensitivity after 16 weeks [126]. It is noteworthy that the adiponectin levels induced by exercise are strongly dependent on changes in the subjects’ BMI [127]. This means that the positive effect of aerobic exercise on adiponectin is not only closely related to the duration, intensity, and frequency of the aerobic exercise but also to the diet of the patients after exercise. If the exercise intensity does not result in weight loss, there will not be a significant change in adiponectin levels in the body.

In terms of pharmacotherapy, several medications have been identified to augment adiponectin levels in the body. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are recognized as among the most effective drugs for increasing adiponectin content. A systematic analysis revealed that TZDs exert a positive effect on promoting adiponectin elevation, stimulating adiponectin production, which is independent of their impact on patient weight loss [128]. Administration of low-dose pioglitazone (7.5 mg/day) has been shown to elevate high molecular weight adiponectin levels, improve glycemic control, and reduce the incidence of associated side effects, such as weight gain and cardiovascular risk events [129]. Both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone induce an increase in adiponectin levels in humans, possibly by stimulating adiponectin expression in adipocytes at a post-transcriptional level [130, 131].

With the advancement of research in diabetes and related treatments, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have gained attention. In a study involving 134 predominantly obese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with ipragliflozin at 50 mg/day orally for 24 weeks, an increase in adiponectin levels was observed [132]. Similarly, in a prospective study of 54 Japanese patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, dapagliflozin administration for 6 months led to increased vascular endothelial clearance, elevated adiponectin levels, and reduced body fat content [133]. It was found that in 316 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, the use of the dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist tirzepatide at a dosage of 10 or 15 mg/day for 26 weeks resulted in weight loss and a significant increase in adiponectin levels [134]. Another study seems to corroborate this finding. A meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials involving 1497 subjects indicated that the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists, particularly liraglutide, can increase adiponectin levels, and this process is independent of weight loss [135]. This process may be related to the ability of GLP-1 agonists to upregulate adiponectin mRNA in adipocytes through silent information regulator sirtuin 1(Sirt1) and the transcription factor Foxo-1, thereby enhancing adiponectin expression [136].

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) used as antihypertensive agents have shown positive effects on adiponectin regulation. Adiponectin and insulin sensitivity were found to increase after 2 months of treatment with losartan alone or in combination with simvastatin in patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia, with more pronounced changes observed in the combination group [137]. Similarly, in a cohort of 50 patients with type 2 diabetes treated with ramipril (10 mg) and simvastatin (20 mg), blood pressure reduction, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and increased plasma adiponectin levels were observed with ramipril alone or in combination, with greater improvements seen in the combination therapy group [138]. A study involving sixteen patients with essential hypertension, where nine received the Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor temocapril and seven received the angiotensin-II receptor blocker candesartan for 2 weeks, revealed a 15% and 30% increase in adiponectin levels, respectively, two weeks later in both groups [139].

Currently, two main classes of lipid-regulating medications can influence

adiponectin levels: statins and fibrates. A meta-analysis revealed that

simvastatin increased adiponectin levels only with long-term usage (

Fibrates, another class of antilipidemic drugs, also appear to raise adiponectin levels. A systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that fibrate therapy significantly increased adiponectin levels in the body [143]. Moreover, comparative analysis suggests that both statins and fibrates have similar efficacy in promoting adiponectin elevation, with the differential effects of statins and fibrates on cardiovascular diseases seemingly independent of changes in adiponectin levels [144].

It is worth noting that besides discovering drugs that can increase adiponectin levels in the body, there have also been efforts to develop certain medications as adiponectin receptor agonists. These drugs exert adiponectin-like effects by stimulating adiponectin receptors. Currently, the most promising drugs in this regard are ADP355 and AdipoRon. ADP355 is an active peptide derived from adiponectin. It exhibits favorable adiponectin-mimetic effects in vivo, demonstrating good efficacy in anti-fibrosis, reversal of hyperinsulinemia, and regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism [145].

AdipoRon, as an orally active adiponectin receptor agonist, exhibits selective activation of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 in vivo. It demonstrates adiponectin-like effects including anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, and anti-ischemic properties. Furthermore, it exerts favorable effects in anti-tumor activity and inhibition of neointima formation induced by arterial injury [145, 146, 147].

Although the effects of ADP355 and AdipoRon are quite extensive, their mechanisms and specific outcomes are still under investigation and have not been fully elucidated. While some potential effects have been demonstrated in animal studies and in vitro experiments, further research and validation are required to understand their clinical application and long-term effects in the human body.

With the development of surgical techniques, it has been found that, in addition to medication, bariatric surgery can also positively affect adiponectin levels in the body. By comparing relevant biochemical substances in 50 severely obese female patients, with or without metabolic syndrome, before and six months after undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, it was found that postoperatively, adiponectin levels increased significantly, leptin levels decreased significantly, and the adiponectin/leptin ratio increased significantly. This phenomenon may be related to the reduction in the patients’ BMI and the increase in HDL levels. The specific mechanisms underlying these changes require further research and exploration [148].

In recent years, numerous studies have elucidated the biological role of adiponectin and its underlying mechanisms. As an adipocytokine, adiponectin is intricately linked to various chronic cardiovascular diseases. It is increasingly evident that elevated adiponectin levels predict a higher risk of mortality and poor prognosis in cardiovascular patients. However, adiponectin cannot be conclusively deemed a marker for coronary heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or heart failure. Further validation necessitates multicenter, large-scale hematological data analysis and mechanistic studies. While many studies have underscored the manifold protective effects of adiponectin, it is noteworthy that g-ad and f-ad exhibit divergent effects in several respects. Several investigations have demonstrated a positive correlation between g-ad levels and disease severity, suggesting a potential mediating role of g-ad in disease progression. Moreover, most studies on the mechanisms of adiponectin action have struggled to account for the influence of circulating f-ad and g-ad conversion on experimental outcomes, indicating a promising avenue for future research. Despite the considerable progress in unveiling the potent regulatory effects of adiponectin on inflammation, injury, atherosclerosis, fibrosis, as well as glucose and lipid metabolism, its complex association with inflammatory and metabolic heart diseases, such as coronary heart disease, suggests a potential relevance of adiponectin as a marker for the severity of atherosclerotic coronary diseases. However, consensus on the underlying mechanism remains elusive. In conclusion, further investment in studying the mechanisms of adiponectin action is warranted, and its potential as a protein marker for cardiovascular diseases remains promising.

SL and XH drafted the manuscript. SL produced the Figs. 1,2,3. JS consulted the literature and produced Tables 1,2. XH interpreted and analyzed the collected literature and proofread the manuscripts. TX and MD designed and guided this paper. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (821RC684, 823RC572). Hainan Health Science and Education project (22A200236).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.