1 Division of Korean Medicine (KM) Science Research, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, 34054 Daejeon, Republic of Korea

2 Korean Convergence Medical Science, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM) Campus, University of Science and Technology, 34054 Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Abstract

Bacterial Artificial chromosome (BAC) recombineering is a powerful genetic manipulation tool for the efficient development of recombinant genetic resources. Long homology arms of more than 150 kb composed of BAC constructs not only substantially enhance genetic recombination events, but also provide a variety of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are useful markers for accurately docking BAC constructs at target sites. Even if the BAC construct is homologous to the sequences of the target region, different variations may be distributed between various SNPs within the region and those within the BAC construct. Once the BAC construct carrying these variations was precisely replaced in the target region, the SNP profiles within the target genomic locus were directly replaced with those in the BAC. This alteration in SNP profiles ensured that the BAC construct accurately targeted the designated site. In this study, we introduced restriction fragment length polymorphism or single-strand conformation polymorphism analyses to validate and evaluate BAC recombination based on changes in SNP patterns. These methods provide a simple and economical solution to validation steps that can be cumbersome with large homologous sequences, facilitating access to the production of therapeutic resources or disease models based on BAC-mediated homologous recombination.

Keywords

- single nucleotide polymorphism

- bacterial artificial chromosome

- homologous recombination

- single-stranded conformational polymorphism

- restriction fragment length polymorphism

- human pluripotent stem cell

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) possess several properties such as self-renewal, proliferation, and pluripotent differentiation abilities [1, 2, 3, 4]. Owing to these properties, hPSCs have substantially contributed to the development of drug screening, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine [5, 6, 7]. Moreover, through the application of genetic engineering techniques, hPSCs can provide a much more advanced and expanded platform for these research areas [8, 9, 10, 11]. The efficient application of genetic engineering techniques comes from the inherent ability of hPSCs to form individual clones, known as clonogenicity [6]. By exploiting these properties, genetically modified hPSCs can be efficiently obtained by introducing genetic modification tools at the single-cell stage and growing them into homogeneous clones through a subsequent modification process.

To date, a variety of genetic modification tools have been employed in hPSCs, including widely recognized programmable nucleases, such as Zinc finger nuclease (ZFN), Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) [12, 13, 14]. In addition, Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vectors, which act as nonprogrammable nuclease modes, have emerged as prominent tools for gene therapy and modification [15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Our research team has developed various genetically modified human pluripotent stem cell models for gene therapy and disease interpretation since the initial application of the BAC vector, which retains lengthy sequences without cleavage, in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) [20].

BAC vectors typically contain extensive insertions of 150 kb or more and have been used in genome sequencing efforts, such as the Human Genome Project [21, 22, 23, 24]. Furthermore, the elongated sequence characteristics of BAC vectors open up avenues for their use in developing disease models through genetic recombination [25, 26, 27, 28]. When generating genetically modified mice as disease models, only part of the BAC DNA sequence, not the entire sequence, is sufficient to induce genetic recombination [29, 30, 31]. This suggests that mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) can efficiently undergo genetic recombination using only a few kilobases (kb) of the BAC DNA sequence. Based on our experience with the genetic manipulation of mESCs, we attempted the genetic manipulation of hESCs. Regarding the length of the donor DNA sequence required to develop genetically modified mESCs, such as conventional knockout or knock-in, we initially employed short donor sequences of approximately 10 kb to attempt genetic modifications based on hESCs. In mESCS, a short BAC DNA sequence of a few kilobases was sufficient to efficiently cause genetic modification at the target site; however, in hESCs, constructing a BAC DNA sequence of that length was not practical, as it would hardly be targeted [20]. Considering that BAC DNA-based genetic recombination depends on the length of these sequences, we engineered genetically modified hESCs by transfecting them with BACs of varying lengths, ranging from 30 kb to extensive sequences exceeding 150 kb, to increase the frequency of homologous recombination. Rare homologous recombination was observed with BAC DNA featuring a 30 kb homology sequence, while an 80 kb homology sequence prompted homologous recombination with a mere 3% efficiency [20]. Notably, homologous sequences exceeding 150 kb substantially augment homologous recombination events, achieving efficiencies exceeding 20% at the target gene locus [20, 32, 33, 34]. In conclusion, although the suitable sequence length for efficient genetic recombination in mESCs is only a few kilobases, hESCs require a sequence length of at least 150 kb to promote efficient recombination, indicating the importance of BAC sequence length in hESCs.

Although the utilization of long-sequence BAC vectors provides the distinct advantage of efficiently inducing homologous recombination, information on the experimental process for screening recombinant clones remain scarce. Although the entire process of BAC recombination has been previously described in detail, the superficial methodological description of the screening steps poses a hurdle in the development of gene therapy or genetically modified clones using BAC recombination [20]. This review aimed to introduce methods to efficiently verify and evaluate recombinant clones modified with long-sequence BAC vectors. Specifically, these methods encompass restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and single-stranded conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analyses based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. Therefore, we present a specific methodology on not only the importance of utilizing SNPs in BAC recombination through SNPs distributed in the BAC sequence, but also how two analytical methods can be applied to screening based on these. Through these analytical approaches, we endeavored to offer an economical and streamlined solution to the potentially intricate steps of BAC recombination, facilitating rapid, accurate, and cost-effective screening while minimizing time and labor requirements [40].

SNPs are variations in DNA sequences across populations [41, 42]. Thus, the SNPs confer genomic diversity by exhibiting varied patterns among individuals, thereby phenotypically revealing individual differences [43, 44]. Although most SNPs rarely affect health or development, certain variations may serve as risk factors for specific diseases or affect drug sensitivity and toxic reactions [45, 46, 47]. SNPs are typically distributed throughout the genome at an average frequency of approximately one occurrence per 300–2000 nucleotides, resulting in an estimated 84.7 million SNPs in the human genome pool [43, 44, 48]. The presence of various SNPs is also reflected in BAC libraries derived from the human genome. Typically, BAC DNA with approximately 150 kb or more of homologous sequences applied to genetic recombination may harbor dozens to hundreds of different SNPs across its entire length [49, 50]. In the genotyping step, SNPs present within the BAC can serve as useful analytical markers to ensure the accurate integration of exogenous BAC into the target locus via genetic recombination. Heterozygous SNPs can provide valuable information for genotyping analyses. The status of SNPs, heterozygosity, or homozygosity shows different patterns at the corresponding locus depending on each cell type [51, 52]; thus, it is essential to ascertain in advance whether heterozygous SNPs exist within the target DNA sequence of the cell before employing BAC. Specifically, heterozygous SNPs in the target region should be interspersed within the range covered by the BAC sequence. To determine BAC recombination, variants constituting a heterozygous SNP in the target region were examined to identify the variant that was replaced with the BAC sequence. Successful substitution of the target sequence with the corresponding BAC resulted in the conversion of the heterozygous SNP within the target region. Specifically, replacing an allele containing a variant different from that included in the BAC leads to a loss of heterozygosity and, ultimately, a gain of homozygosity for the SNP in the target region. Conversely, if the BAC targets another allele, the heterozygous SNP in the target region remains unchanged. In these cases, accurate BAC integration into the target locus cannot be confirmed. This indicates that there are limitations in determining whether genetic recombination exists based solely on a single heterozygous SNP. Thus, further investigation into the heterozygous status of SNPs adjacent to the target region is required for a definitive determination. If the heterozygous SNPs acquire homozygosity, it confirms the successful incorporation of the BAC into the target site. Therefore, genotyping based on SNPs relies on detecting changes in SNP patterns resulting from the integration of BAC into the target region. Genetic recombination can only be reliably confirmed if at least two informative SNPs within the target region are distributed across each other with the corresponding variants in the BAC sequence, indicating whether one of the two SNPs has achieved homozygosity.

To manipulate the TP53 gene in hESCs using BAC DNA, SNP-based genotyping analysis has been employed to identify or assess genetically modified hESCs generated using various BAC constructs [20]. Considering the application of this analytical method, we sought to determine the optimal length of the BAC sequence required to achieve efficient genetic recombination. Therefore, we constructed BACs of varying lengths: approximately 30, 83, and 167 kb. Our investigation revealed that BACs with a homology sequence of 167 kb or longer were efficiently integrated into the TP53 target locus in approximately 20% of the clones [20]. This confirmation was made possible by SNP genotyping, which allowed us to assess the accuracy and efficacy of genetic recombination mediated by the BAC structure. In addition, the long homologous sequence of BAC allowed more candidate SNPs to be distributed in the sequence, thereby facilitating genotyping analysis based on them. Among the various SNPs investigated in the TP53 gene, rs1042522 is notably recognized as the most prevalent heterozygous SNP and consists of two variants encoding either proline or arginine at codon 72 [53, 54, 55, 56]. The BAC construct contained a single cytosine, representing the rs1042522-C variant (Fig. 1A). HUES8 and HUES9, the two types of hESCs to which BAC technology was applied, harbored the rs1042522-G/C substitution as a common heterozygous SNP (Table 1, Ref. [20, 32, 33, 34, 57] and Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Targeting TP53 gene locus with a BAC vector. (A) Occurrence of a BAC-mediated homologous recombination event in either of the two alleles for the TP53 gene locus. (B) BAC targeting into allele 2 for rs1042522-G of rs1042522-C/G. (C) BAC targeting into allele 1 for rs1042522-C of rs1042522-C/G. rs1042522-C/G indicates a heterozygous SNP located in TP53 gene locus. See also Table 1. BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome; HR, homologous recombination; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

| Cell types | Genes | SNPs | Bases | Restriction endonucleases | References |

| HUES8 | TP53 | rs1625895 | A/G | HpaII | [20] |

| rs1042522 | C/G | BstUI | |||

| HUES9 | TP53 | rs1042522 | C/G | BstUI | [20] |

| rs35850753 | C/T | SpeI | |||

| H1 | DROSHA | rs3805525 | A/G | HpyCH4IV | [57] |

| hiPSC (From fibroblast; CCD1112Sk) | TP53 | rs12944939 | G/A | AciI | [34] |

| rs1042522 | C/G | BstUI | |||

| hiPSC (From LCL; ND14317) | LRRK2 | rs34637584 | G/A | BceAI | [32] |

| hiPSC (From fibroblast; ND40996) | SNCA | rs104893877 | C/T | Tsp45I | [33] |

BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; hiPSC, human induced pluripotent stem cell.

During BAC recombination, hESCs lost inherited heterozygosity due to BAC carrying rs1042522 and gained homozygosity by specifically targeting the allele carrying rs1042522-G (Fig. 1B). This successful replacement indicated the accurate integration of the BAC with rs1042522-C into the allele with the rs1042522-G variant. However, the authenticity of BAC recombination could not be definitively confirmed if the BAC with rs1042522-C was integrated into the other allele carrying rs1042522-C, maintaining the acquired heterozygosity (Fig. 1C).

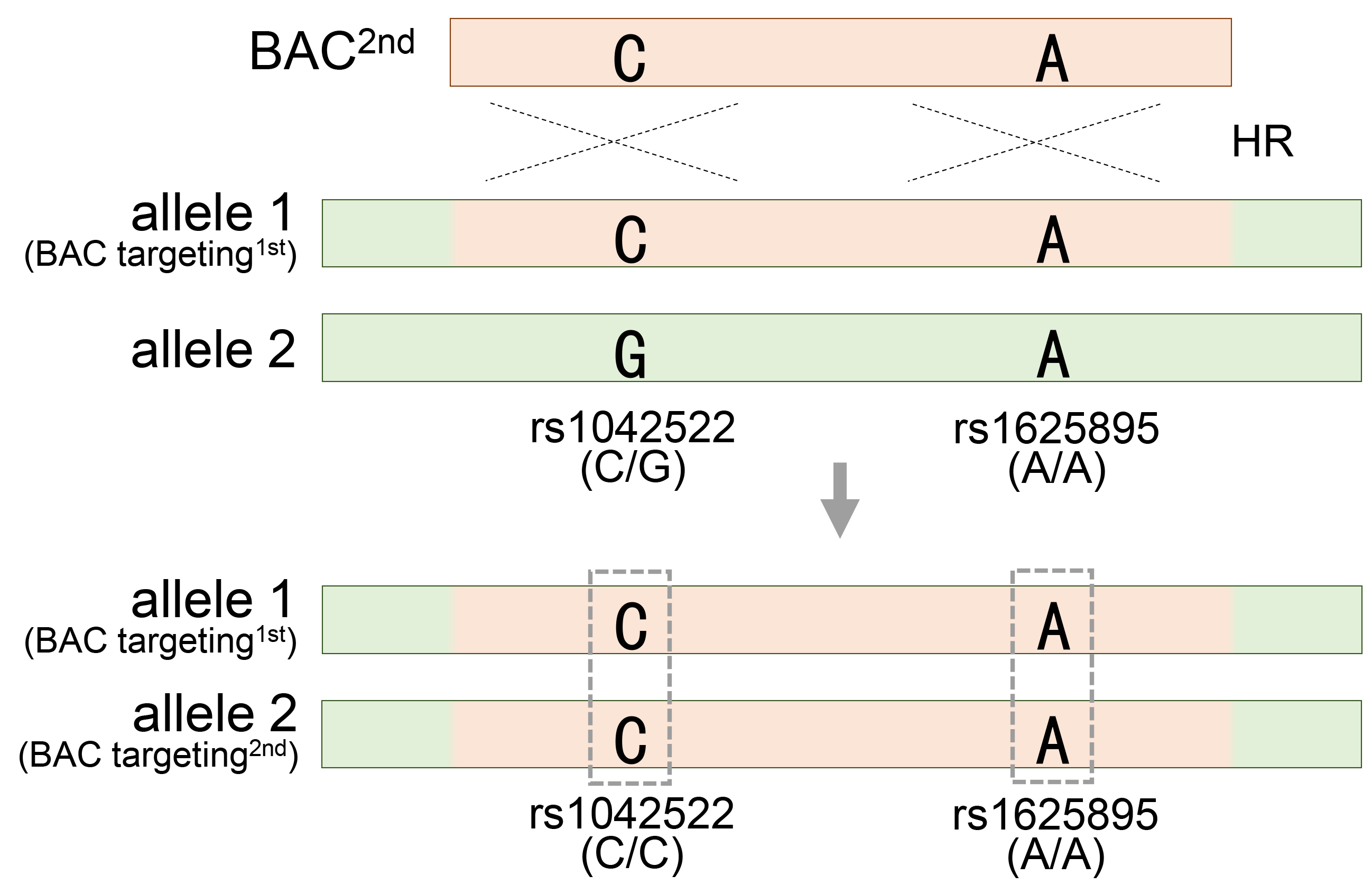

Therefore, it is necessary to further explore the heterozygosity of SNPs distributed in other regions. Fortunately, HUES8 cells exhibited rs1625895-A/G substitutions as heterozygous SNPs adjacent to rs1042522 (Fig. 2A). This additional SNP serves as a valuable marker for assessing whether homozygosity has been achieved through BAC recombination, providing further insight into the genetic modifications facilitated by the BAC construct (Fig. 2A). Similarly, genotyping solely for rs1042522 restricted the reliable determination of the outcome of BAC recombination in HUES9 cells, as these cells may also retain heterozygosity for rs1042522-C/G even after recombination (Fig. 2B). Therefore, an additional investigation involving rs35850753-C/T genotyping is imperative to draw definitive conclusions regarding the integration of BAC containing rs35850753-C into the allele with rs35850753-T, leading to the acquisition of homozygosity, such as the rs35850753-C/C genotype (Fig. 2C). In another type of pluripotent stem cell, TP53 manipulation has been extended to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from human fibroblasts [34]. Similar to the two types of hESCs introduced earlier, these cells were also heterozygous for the commonly encountered SNP rs1052522-C/G. Additionally, to assess BAC recombination more confidently, the heterozygosity for rs12944939-G/A, located in intron 1, was further explored (Fig. 2C). As expected, if genotyping based on two SNPs distributed across each other suggests acquired homozygosity for either allele, it means that BAC is definitely integrated into one of the two alleles (Fig. 2C). In summary, heterozygous SNP in genotyping analysis offer valuable genetic information to discern the acquisition of homozygous SNP following BAC-mediated genetic manipulation. In particular, additional SNP analysis ensures recombination results that may be missed when analyzing only one SNP. Therefore, the inclusion of at least two heterozygous SNP markers ensures the accuracy and productivity of genotyping.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Acquiring homozygosity of other heterozygous SNPs other than heterozygous rs1042522 on allele 1 targeted by the BAC vector (continued from Fig. 1C). (A) Acquisition of homozygosity of heterozygous rs1625895 by BAC targeting in HUES8 cells. (B) Acquisition of homozygosity of heterozygous rs35850753 by BAC targeting in HUES9 cells. (C) Acquisition of homozygosity of heterozygous rs12944939 by BAC targeting in hiPSC cells. rs1042522-C/G indicates a heterozygous SNP located in TP53 gene locus. See also Table 1.

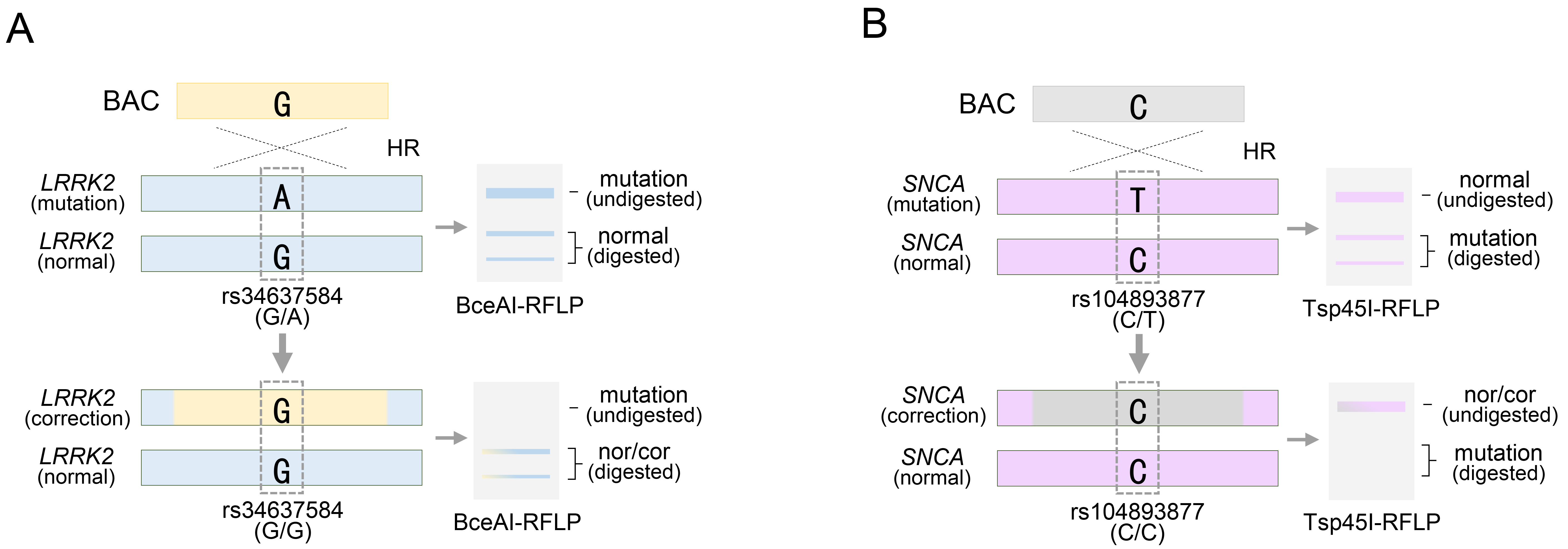

Furthermore, BAC technology has been employed in the genetic treatment of LRRK2 or SNCA genes, which are representative autosomal dominant genes associated with Parkinson’s disease [32, 33]. Notably, mutations in these genes, such as LRRK2 G2019S and SNCA A53T, exhibit high penetrance during Parkinson’s disease (PD) pathogenesis [58, 59, 60, 61]. Unlike autosomal recessive mutations, pathological mutations in these genes must be eliminated from the genome. The method used to assess mutation removal was identical to that used for SNP-based genotyping. The LRRK2 G2019S substitution, identified as rs34637584-G/A in PD patient-derived cells, represents a heterozygous mutation, and among the two genotypes, the pathological allele containing rs34637584-A is subject to correction (Fig. 3A). Using a BAC with a 195 kb homology sequence, the PD-causing mutation was effectively treated by replacing the pathological allele with the normal rs34637584-G allele within the BAC sequence [32]. Confirmation of homozygous acquisition, such as rs34637584-G/G, was sufficient to validate successful genetic recombination mediated by BAC (Fig. 3A). Previously, we mentioned the value of two or more heterozygous SNPs, but the BAC only requires the replacement of the pathological allele and does not require targeting of normal alleles. Therefore, additional SNP exploration was unnecessary. Similarly, BAC technology has been applied to address mutations in SNCA, another pivotal gene implicated in PD. Specifically, we targeted the rs104893877-T mutation in SNCA, which affects the onset of PD (Fig. 3B). By employing a BAC with a 168 kb homologous sequence containing the normal rs104893877-C allele, the pathological allele containing rs104893877-T was replaced. Similar to the genotyping for the LRRK2 G2019S gene therapy approach, SNCA gene therapy required confirmation of the removal of the PD-related pathogenic variant rs104893877-T from the inherited heterozygous SNP rs104893877-C/T. As a result, the acquisition of a homozygous SNP, such as rs104893877-C/C, indicated successful genetic recombination by the BAC (Fig. 3B). Collectively, the value of SNP genotypes has been evaluated to distinguish variations in BAC and their replacements distributed in target sites during the process of identifying genetic modification models or genetic mutation treatments by BAC recombination. Furthermore, this can be manifested by introducing SNP-based experimental methods in detail, as follows:

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Targeting Parkinson’s disease (PD)-related pathogenic allele with a BAC vector. (A) BAC targeting into pathogenic allele for rs34637584-A located in LRRK2 gene locus. (B) BAC targeting into pathogenic allele for rs104893877-T located in SNCA gene locus. rs34637584-G/A or rs104893877 represents a heterozygous SNP in the LRRK2 or SNCA gene, respectively. See also Table 1. HR, homologous recombination.

During genetic manipulation based on hPSCs, it is important to identify genetic recombination clones among candidate clones in a timely manner to avoid the arduous task of maintaining uncertain clones [36]. Hence, a rapid and accurate evaluation method is imperative for screening recombinant genetic clones. To comply with this requirement, we proposed the use of RFLP analysis as an evaluation method for BAC recombination. RFLP analysis can detect subtle differences in DNA sequences by distinguishing the length of fragments digested by restriction endonucleases that specifically recognize genetic variations harbored in products amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67]. When SNPs in the target region were replaced by SNPs in the BAC sequence via BAC recombination, the SNP pattern in the target region changed. A change in the SNP pattern may result in the creation or disappearance of a site that can be specifically recognized by a restriction endonuclease. A restriction endonuclease that specifically recognizes one variation of heterozygous SNP cannot recognize the other, which may result in two fragments: digested and undigested. However, acquiring homozygous SNPs through BAC recombination generates only one type of mutation that can be recognized by restriction endonucleases, resulting in only one digested or undigested fragment. Enzymatic reactions of short products of PCR based on genomic DNA prepared from candidate clones not only simplify the screening process but also contribute to substantial labor savings, allowing rapid and accurate evaluation of genetic recombination events.

In the BAC recombination for the TP53 gene, RFLP analysis was performed based on SNPs, especially during the evaluation stage for discovering TP53 genetically engineered clones. As previously mentioned, rs1042522-C/G, located within the exon region of the TP53 gene, is a heterozygous SNP and is notable for RFLP analysis, because the two variations can be distinguished by a specific restriction endonuclease (Fig. 4A). Therefore, of the two genetic variations of this SNP, only rs1042522-G and not rs1042522-C could be recognized using BstUI, a type of restriction endonuclease that cleaves this variant. Therefore, employing BstUI-RFLP analysis, the presence of heterozygosity at the rs1042522 SNP in these cell types was clearly indicated by the distinction between digested and undigested fragments (Fig. 4A). A BAC containing rs1042522-C, which is not recognized by BstUI, can target either an allele harboring rs1042522-G or an allele harboring rs1042522-C. When BAC targeted an allele with a variant differing from that of rs1042522-C, the inherited heterozygous SNP is replaced with a homozygous SNP (Fig. 4B). BstUI did not recognize the homozygous SNP rs1042522-C/C, resulting in the retention of an undigested fragment (Fig. 4B). This indicated successful BAC targeting at the desired site, facilitating clone acquisition. However, if BAC targets the other allele with rs1042522-C, the heterozygosity of the rs1042522-G/C SNP remains and determination of BAC recombination using the BstUI-RFLP analysis method is inconclusive (Fig. 4C). Therefore, additional heterozygous SNPs were required. The intronic region 4 of the TP53 gene contains the heterozygous SNP rs3585073-C/T, which can be discerned using the SpeI restriction endonuclease (Fig. 4A). RFLP analysis using SpeI clearly distinguished between digested and undigested fragments in HUES9 cells, indicating that this SNP is heterozygous [20]. Upon analyzing the status of these added SNPs, RFLP analysis using SpeI for clones in which BAC recombination could not be confirmed by BstUI revealed only undigested fragments (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that rs3585073-C in the BAC sequence was integrated into the allele with rs3585073-T. Therefore, the inherited heterozygous SNP was lost, and the homozygous SNP rs3585073-C/C was acquired. BstUI cannot conclusively ascertain BAC recombination; however, successful BAC engineering was ultimately confirmed using additional SpeI. These findings emphasize the need for supplementary SNP analyses of recombinant clones, which may be overlooked in SNP analyses. In addition, through RFLP analysis between different SNPs, it was possible to accurately distinguish the intra-allelic variation of the variation constituting the two SNPs and the distribution location of the inter-allelic variation (Fig. 4B,C).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

RFLP analysis of alleles for rs1042522 or rs35850753 following BAC targeting in HUES9 cells. (A) Two restriction endonucleases, BstU1 or SpeI, are provided for RFLP analysis for rs1042522 or rs35850753, respectively, subsequent to BAC targeting at the TP53 gene locus. (B) BAC targeting to allele 2 of rs1042522-C/G to rs1042522-G and acquisition of homozygosity confirmed by BstUI restriction endonuclease. (C) BAC targeting into allele 1 for rs35850753-T of rs35850753-C/T and acquisition of homozygosity confirmed by SpeI restriction endonuclease. rs1042522-C/G or rs35850753 represents a heterozygous SNP located in the TP53 locus. See also Table 1. RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Seong et al. [57] introduced BAC DNA targeting DROSHA into H1 hESCs. In H1 hESC, the rs3805525 SNP is located within intron 35 of DROSHA. This SNP consists of a heterozygous rs3805525-A/G, and knock-in was confirmed by the loss of heterozygosity due to BAC DNA targeting. The restriction endonuclease, HpyCH4IV, applied in this experiment recognized only rs3805525-G and could distinguish the heterozygosity of the SNP. Thus, the presence of a BAC DNA target was confirmed using RFLP genotyping. As a result, BAC DNA contains rs3805525-G in the informative SNP, indicating that a homologous recombination event occurred due to the loss of heterozygosity when BAC DNA was targeted to the rs3805525-A allele (Table 1).

It is meaningless to target alleles with normal nucleotides in LRRK2 or SNCA gene therapy if BAC does not target pathogenic mutations. Therefore, the presence of homozygous rs34637584-G/G or rs104893877-C/C in each LRRK2 or SNCA gene exhibiting therapeutic effects can be easily confirmed through BceAI or Tsp45I restriction endonuclease-based RFLP analysis without exploring additional heterozygous SNPs (Fig. 5A,B). Thus, the RFLP analytical method based on specific restriction endonucleases can feasibly distinguish or recognize the mutation site and rapidly determine whether the patient should undergo gene therapy. However, commercially available restriction enzymes have limitations in covering all combinations of DNA sequences. Thus, the RFLP analytical method, which relies on specific restriction endonucleases, has been circumscribed in universal applications. Therefore, alternative methods that can achieve the same effect while overcoming the limitations of the RFLP analytical methods are required.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

RFLP analysis of PD-related pathogenic alleles for rs34637584 or rs104893877 following BAC targeting. (A) BAC targeting for rs34637584-A, a pathogenic allele of the LRRK2 gene, and acquisition of homozygosity confirmed by BceAI restriction endonuclease. (B) BAC targeting for rs104893877-T as a pathogenic allele of the SNCA gene, and acquisition of homozygosity confirmed by Tsp45I restriction endonuclease. See also Table 1.

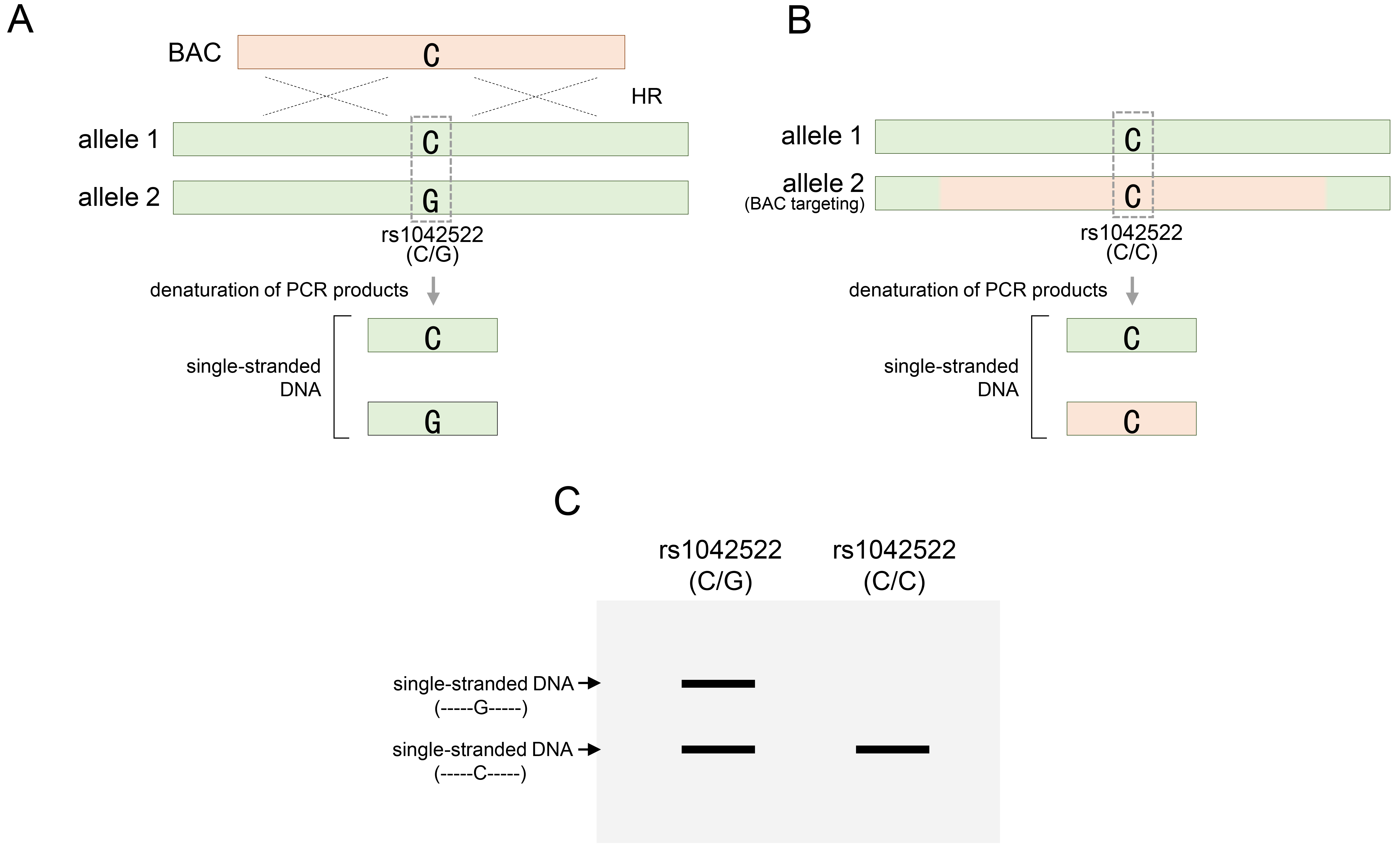

SSCP analysis directly distinguishes the altered patterns of SNP variations in homologous sequences replaced by BAC, without requiring restriction endonucleases [68]. In addition to RFLP, it is a simple and cost-effective analysis method that can be rapidly and accurately [69, 70, 71]. SSCP analysis relies on single-stranded DNA conformational changes that reflect differences in DNA migration subsequent to DNA conformation [70]. In principle, even a single mutation within a homologous DNA sequence can induce conformational changes in single-stranded sequences. Unlike electrophoresis on conventional DNA gels, which are distinguished mainly by DNA sequence length, these conformational differences cause migration changes in each single strand to appear in different patterns in a particular DNA gel [70]. Through SSCP analysis, the type of specific variant sequence could not be determined, but the presence or absence of variations could be confirmed through changes in the pattern compared to the control group. Based on this principle, single-stranded DNA resulting from each variant constituting heterozygous SNPs exhibited a distinct conformation that manifested as two distinct band patterns on the SSCP gels. Conversely, acquiring homozygous SNPs through BAC recombination resulted in a singular conformation that aligned with one of the bands revealed by the heterozygous SNP. Consequently, through the loss of heterozygosity via BAC recombination, changes in the band patterns facilitate the determination of BAC recombination within the target region. As shown in Fig. 6, two different types of single-stranded DNA were formed from heterozygous rs1042522 through denaturation (Fig. 6A). Each strand has a unique conformation due to a single nucleotide difference. Unlike electrophoresis on conventional DNA gels, which is distinguished mainly by the DNA sequence length, these conformational differences cause migration changes in each single strand to appear in different patterns under SSCP electrophoresis conditions. When the BAC DNA was targeted to allele 2, rs1042522 lost its heterozygosity and formed only one type of single-stranded DNA (Fig. 6B). These results can be identified by the pattern in which one of the two strands disappears, unlike the pattern that appears when heterozygosity is maintained under SSCP electrophoresis conditions (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Identification of BAC DNA targeting through SSCP analysis. (A) Single-stranded DNA denatured from PCR products containing heterozygous rs1042522 for the TP53 gene. (B) BAC targeting into allele 2 for rs1042522-G of rs1042522-C/G, and single-stranded DNA denatured from PCR products containing homozygous rs1042522. (C) Confirmation of heterozygosity of rs1042522 before (A) or after (B) BAC targeting in SSCP gel. rs1042522-C/G indicates a heterozygous SNP located in TP53 gene. SSCP, single-strand conformation polymorphism.

Genetic modification tools, including ZFNs, TALENs, CRISPR, and their derivatives, have evolved into various versions that remove, insert, or replace nucleotides, thereby expanding the range of genetic modification options. Each genetic manipulation tool pursues simplicity, convenience, and efficiency while resolving the drawbacks of each tool [12, 72, 73]. However, despite improvements, there remains a need to enhance the efficiency of gene editing reproducibly across all types of sequences, ranging from single-base modulation to extended transgene introduction, while minimizing off-target effects that affect genome safety [74, 75].

BAC recombination enables precise genetic modification with high efficiency and consistency, regardless of the length of the transgene sequence, ranging from a single base to several kilobases. The effectiveness of BAC recombination relies on the principle of homologous recombination, wherein transgenes spanning a range of lengths between the extended homology arms of the BAC are effectively integrated at the target site. BACs with homologous sequence lengths of more than 150 kb substantially improved the targeting efficiency to a designated site by more than 20%. Unlike the programmable nuclease mode, which requires enzymatic reactions triggered by molecules, such as restriction enzymes, BAC recombination relies solely on sequence complementarity, which consists of long homologous sequences, thus eliminating concerns about potential genomic damage caused by the enzyme. Therefore, BAC recombination has the potential to address genome safety issues associated with other gene editing systems.

A longer BAC sequence not only increases the efficiency of gene recombination by homologous recombination but also provides useful information for evaluating and validating BAC recombination. The extensive BAC sequence contains numerous SNPs that exhibit distinct patterns compared to those in the target region. When a BAC is integrated into a target region, SNPs in the original target region are replaced by SNPs present in the BAC, thereby changing the SNP pattern in the surrounding regions. These changes in the SNP patterns serve as informative markers for assessing and quantifying the efficacy of BAC recombination. At least two heterozygous SNP markers are required to obtain BAC engineering results. Therefore, 50% of BAC recombinants can be predicted by analyzing only one heterozygous SNP in a specific region. The remaining recombinants that could have been missed through additional heterozygous SNP analyses can also be successfully obtained. If one of the two heterozygous SNPs acquires homozygosity (rs1625895), the other remains heterozygous (rs1042522), indicating that genetic recombination occurs in only one of the two target sites, the heterozygote (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, the heterozygous SNP rs1042522 was used to evaluate and validate the homozygous recombinant clone, which underwent a second genetic recombination event with the other allele. If both heterozygous SNPs sequentially achieve homozygosity, it ultimately means that both allelic regions have undergone accurate genetic recombination (Fig. 7). As a result, determining recombination experimentally can be cumbersome because of the large length of the homology arms of BAC. Therefore, the use of changes in SNP patterns to evaluate them accurately during the screening stage requires important insights. To meet this requirement, RFLP and SSCP analysis methods, which can clearly detect changes in SNP patterns accompanied by BAC recombination, provide a simple solution that simplifies the screening process.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Generation of homozygous mutant cell by introduction of a second BAC vector in the heterozygous mutant cell. Acquiring homozygosity for heterozygous rs1042522, which means generating homozygous TP53 mutant HESC8 cells through secondary BAC targeting in the heterozygous TP53 mutant HUES8 cells. See also Fig. 2A and Table 1.

SKC was responsible for the entire preparation of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was funded by Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, KSN2213010.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.