1. Introduction

The aging population is experiencing a significant rise in the incidence and

prevalence of age-related diseases, such as coronary heart disease (CHD) and

atrial fibrillation (AF) [1, 2]. Telomeres, consisting of repetitive sequences at

the distal ends of chromosome, serve as important biomarkers of aging, and the

shortened length of telomeres is strongly associated with cardiovascular aging

and disease. Patients with shorter telomeres in peripheral blood leukocytes are

at higher risk of cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure (HF) and AF [3].

Telomeres depend on telomerase to synthesize their own repetitive sequences as a

means of compensating for telomere shortening caused by cell division. Telomerase

reverse transcriptase (TERT) is the rate-limiting enzyme of telomerase, which

means that TERT directly influences telomerase activity and ultimately determines

telomere length [4]. Research has been increasingly focusing on the maintenance

of telomere length through activation of TERT to delay aging, as well as on the

prevention and even treatment of age-related diseases. TERT has shown promising

applications in the treatment of CHD, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)

injury, HF, and cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in mice. However, studies on its effects on the

electrophysiology of cardiomyocytes are sparse [5, 6]. Previous studies have shown

that telomere shortening can cause mitochondrial dysfunction and intracellular

Ca overload in cardiomyocytes, which may result in arrhythmias, but the

specific impact of TERT on mitochondrial function and intracellular Ca in

cardiomyocytes is not well understood [7, 8]. The objective of this study was to

investigate the role of TERT in the electrophysiology and mitochondrial function

of mouse atrial myocytes, particularly focusing on its regulatory effects on

intracellular Ca.

TERT plays a vital role in treating cardiovascular diseases and maintaining

heart function. Studies have shown that cardiac-specific TERT overexpression in

an acute myocardial infarction mouse model reduces infarct size in vivo,

and decreases apoptosis in cultured cardiomyocytes in vitro [9, 10].

Ale-Agha et al. [11] demonstrated that mitochondrial TERT reduces

cardiomyocyte apoptosis, ameliorates myocardial fibrosis, and promotes

endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Chatterjee et al. [12]

reported that overexpression of telomerase reduces doxorubicin-mediated apoptosis

and protects cardiac function in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity models.

Madonna et al. [13] observed that overexpression of TERT in cardiac stem

cells increases their survival after I/R injury. Conversely, reduced TERT

activity increases the risk of heart injury. Ait-Aissa et al. [14] noted

that telomerase deficiency predisposes to HF and I/R injury in rats.

Additionally, reduced TERT activity triggers mitochondrial and cellular oxidative

stress, leading to impaired cell division, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and even

death [15, 16, 17]. Previous studies have suggested that telomere shortening activates

p53 expression, subsequently inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) and leading to intracellular Ca

overload and mitochondrial dysfunction [7, 8]. A recent study reported that

telomere damage induces mitochondrial dysfunction via the p53/PGC-1

pathway [18]. Transformation-related protein 53, also known as p53, is critical

in regulating Ca-dependent apoptosis and mitochondrial function [19].

PGC-1 is implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and

energy metabolism. Moreover, PGC-1 not only directly reduces

intracellular Ca but also indirectly alleviates cellular oxidative stress

[20, 21]. Consequently, we hypothesize that TERT regulates cardiomyocyte

mitochondrial function and intracellular Ca homeostasis through the

p53/PGC-1 pathway, ultimately affecting cellular electrophysiology.

In this study, we silenced and overexpressed the TERT gene in vitro to observe its effects on mitochondrial function, intracellular

Ca homeostasis, and electrophysiology of atrial myocytes. Subsequently,

the regulatory effects of TERT on p53/PGC-1 pathway were confirmed by

silencing and overexpressing TERT and interfering with p53 and PGC-1.

Moreover, we explored the feasibility of PGC-1 as an intervention

target for cardiovascular diseases in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell Culture

HL-1 cells were purchased from Shenzhen Haodi Huatuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

(Cat. No. HTX2129; Shenzhen, China). The authors authenticated the cells shortly

before use with the short tandem repeat profiling technique. Mycoplasma testing

was performed using the MycoSensor PCR Assay Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa

Clara, CA, USA). HL-1 cells were cultivated in complete Claycomb Medium (Sigma,

St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Waltham,

MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 4 mM

l-glutamine (Gibco), and 100 µM norepinephrine (Solarbio, Beijing,

China). The cardiomyocytes were cultured on cell culture plastics coverslips

coated with 0.02% gelatin (Sigma) at 37 °C in 5% CO [22]. The medium was

refreshed every 48 h, and the cultures were split 1:3 using standard subculturing

procedures once cells reached high confluence at about 3–4 days.

2.2 Cell Transfection

For cell transfection, TERT-overexpressing lentiviruses and lentiviral-based

small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting TERT were purchased from Genechem Co., Ltd.

(Shanghai, China). Empty lentivirus vector was utilized as a negative control for

TERT and shTERT. The specific sequence of shRNA-TERT is provided in the

supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 1); shTERT#3 was selected

for subsequent experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1). When HL-1 cells

reached 50% confluency, the original medium was replaced with fresh medium

containing 6 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma). Next, virus suspension was added

according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the virus-containing medium was

replaced with fresh complete medium after 24 h. After 72 h, lentiviral-transduced

cells were selected with 3 µg/mL puromycin (Sigma) and verified by Western

blot (WB) analysis. Finally, the most effective shRNA-TERT was used for the

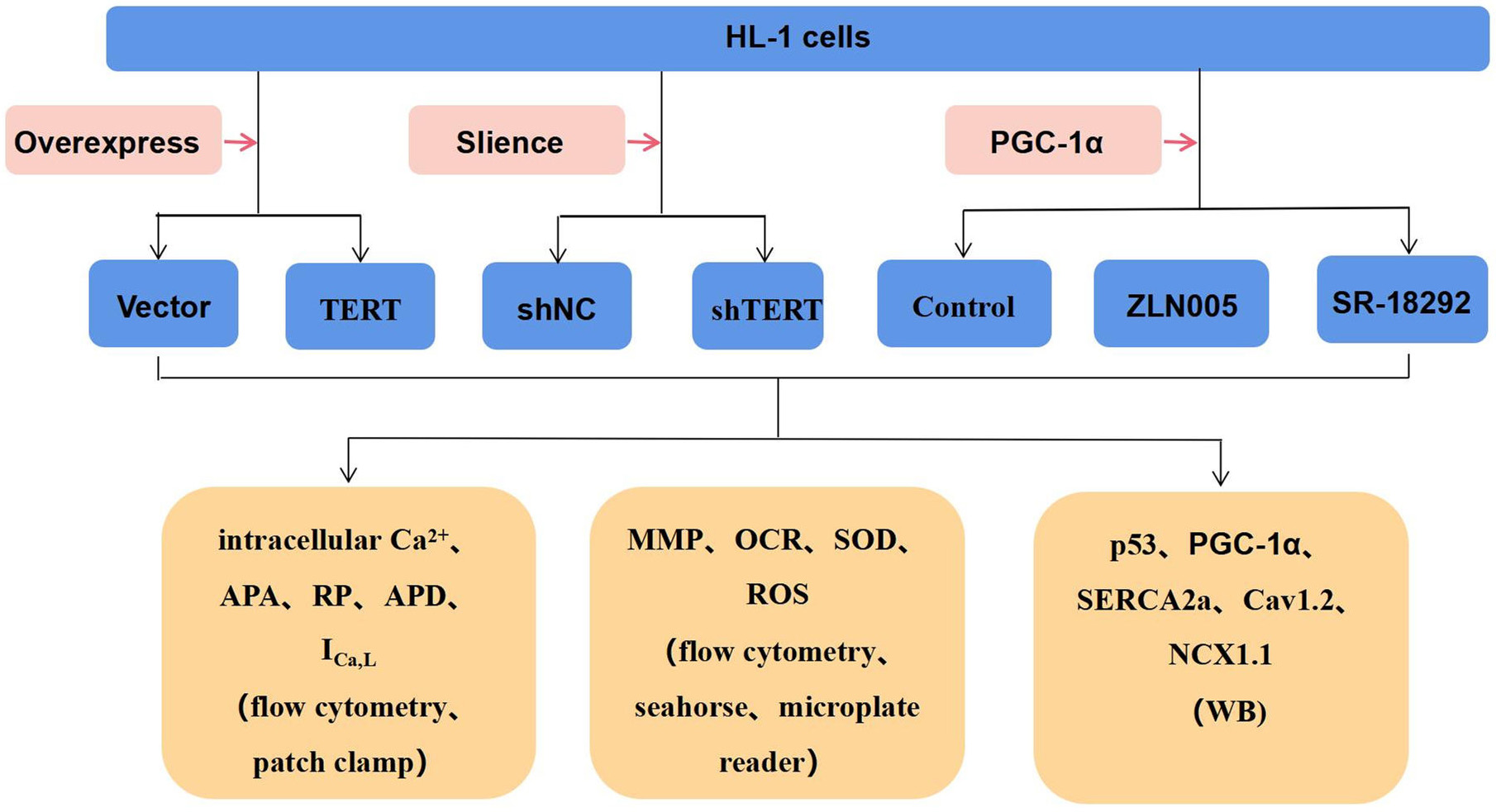

downstream functional experiments. The study design for the experiment is shown

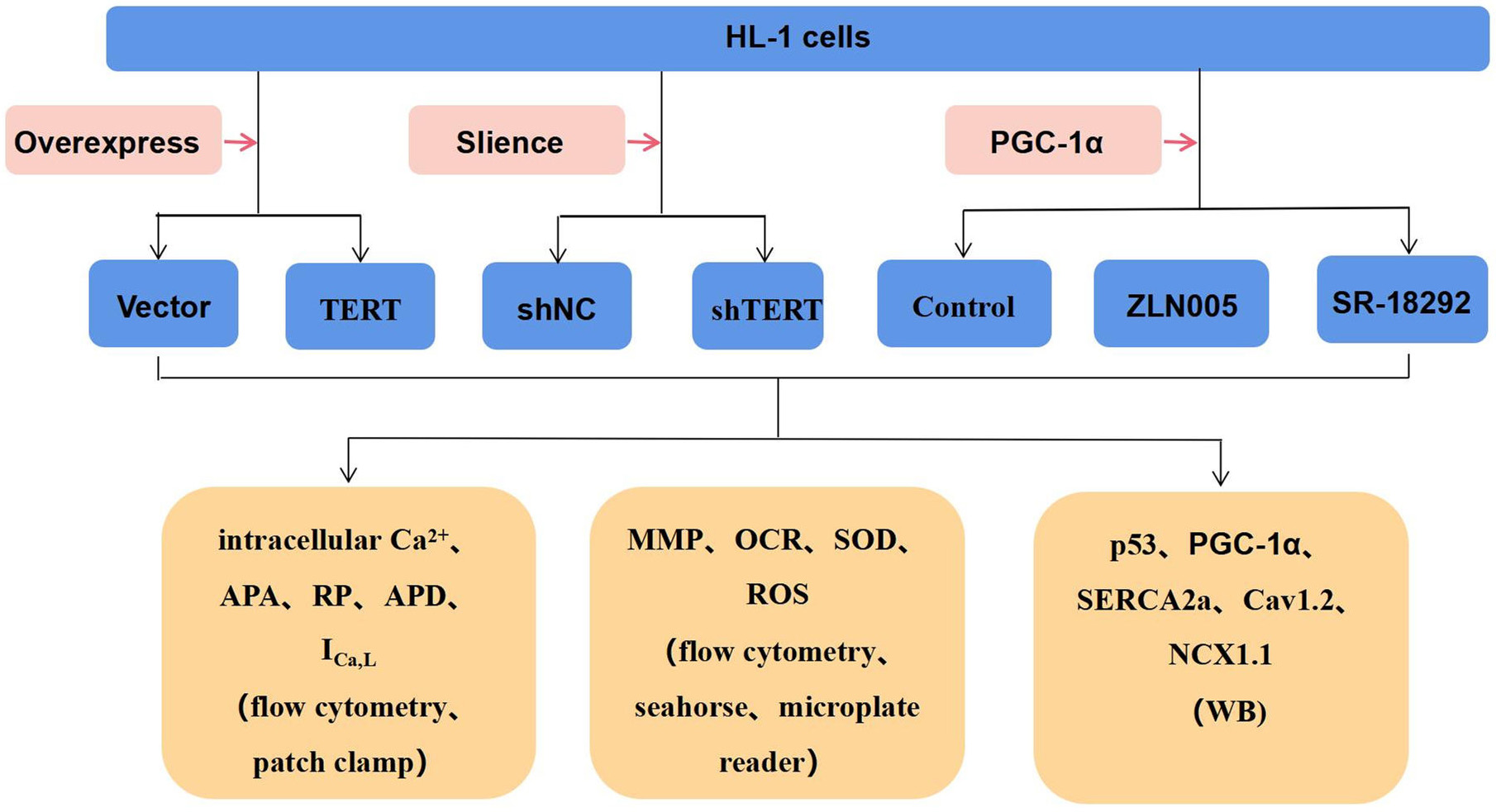

in Fig. 1.

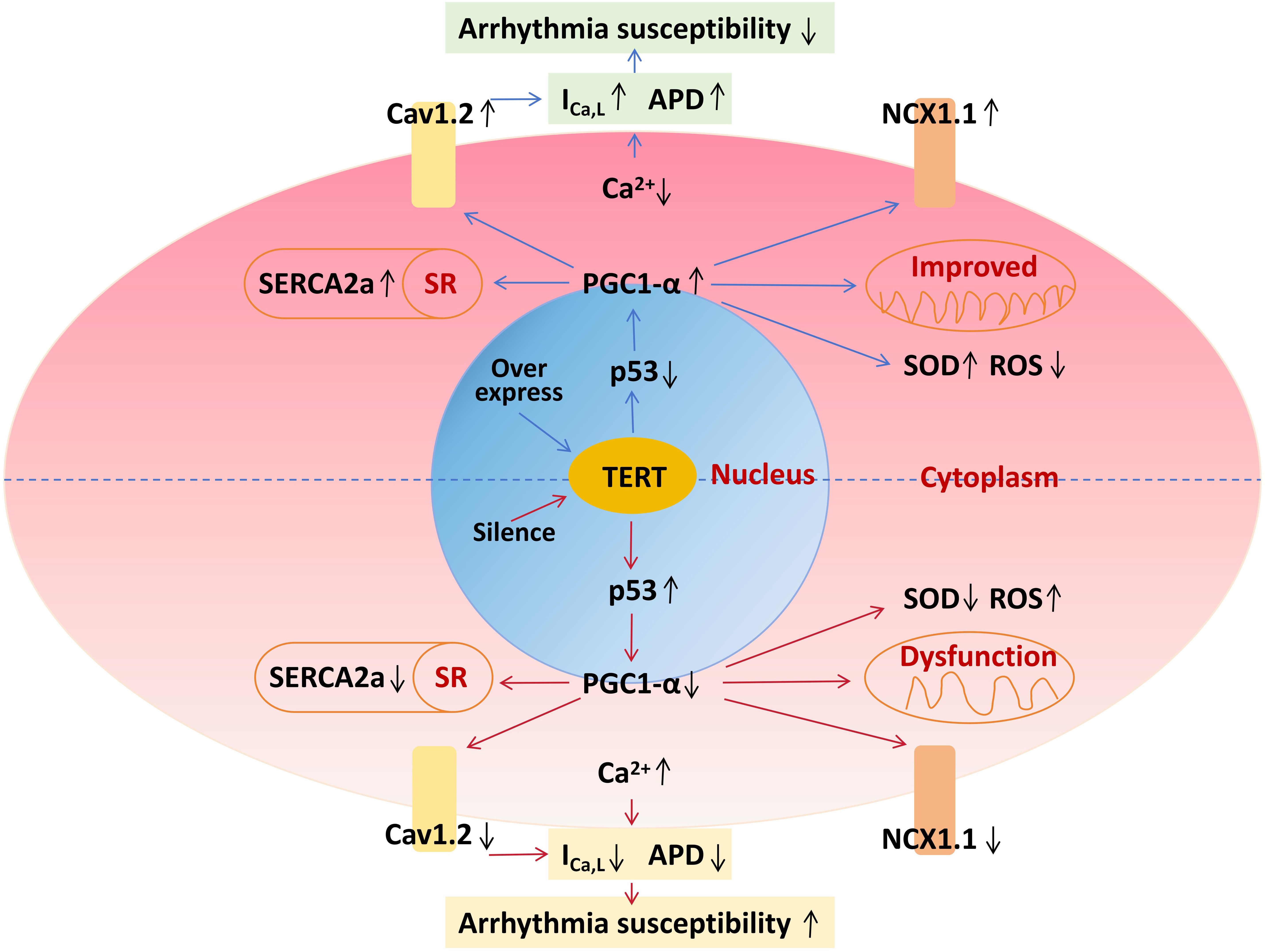

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design for the experiment. TERT, telomerase reverse

transcriptase; PGC-1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

coactivator 1-alpha; APA, action potential amplitude; RP, resting potential; APD,

action potential duration; I, L-type Ca currents; MMP,

mitochondrial membrane potential; OCR, oxygen consumption rate; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; WB, Western blot; shNC, negative control.

2.3 Drug Treatment

When validating the p53/PGC-1 pathway, the concentration of each drug

was determined based on previous literature and preliminary test results [18, 23].

To investigate the effects of p53 on PGC-1, HL-1 cells were treated

with the p53 agonist Tenovin-6 (final concentration of 15 µM; Selleck

Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) and the p53 inhibitor PFT (final

concentration of 15 µM; Selleck), while the control group received an equal

volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Solarbio), and all were co-cultured for 24 h.

To validate the role of PGC-1, HL-1 cells were treated with the

PGC-1 agonist ZLN005 (final concentration of 20 µM;

MedChemExpress [MCE], Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and the PGC-1

inhibitor SR-182923 (final concentration of 20 µM; MCE); the control group

received an equal volume of DMSO (Solarbio) with a co-culture duration of 24 h.

2.4 Cellular Electrophysiology

As we previously described [24], the Axon Multiclamp 700B Amplifier (Molecular

Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) and pClamp software (version 10.4; Axon Co.,

Scottsdale, AZ, USA) were used for the whole-cell patch-clamp study. An electrode

with a tip diameter of 2–4 µm was pulled with the PP-83

Microelectrode Puller (Narishige Co., Tokyo, Japan).

To measure the action potential (AP), the patch clamp was set to “current

clamp” mode, with a clamping potential of 0 mV and stimulation applied at 1500

pA for 10 ms. The AP of the cells in each group was recorded, and parameters such

as AP duration (APD), AP amplitude (APA), and resting membrane potential (RMP)

were calculated. The extracellular solution composition was (in mM): NaCl 140,

KCl 4, CaCl 1, MgCl 1, HEPEs 10, and glucose 10, adjusted to a pH of

7.4 with NaOH. The intracellular solution consisted of (in mM): K-aspartame 120,

KCl 20, NaATP 4, MgCl 1, HEPES 10, and glucose 10, and the pH was

adjusted to 7.4 with KOH.

For voltage-gated L-type Ca current (I) measurements, the patch

clamp was set to “voltage-clamp” mode. A holding potential of –40 mV was used,

with a depolarizing pulse of 0 mV for 150 ms applied to record a slowly

inactivated inward current, which was controlled with 5 µmol/L nifedipine,

a Ca channel blocker. Extracellular solution comprised (in mM): NaCl 135,

CaCl 1, MgCl 5, CsCl 5.4, BaCl 0.3, NaHPO 0.33,

HEPEs 10 and glucose 10, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Intracellular

solution included (in mM): TEA-Cl 10, CaCl 1, MgCl 5, CsCl 120, EGTA

10, NaATP 5, HEPEs 10 and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH.

2.5 Intracellular Ca

HL-1 cells were washed twice with Ca-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

(Solarbio), and incubated with Fluo-4/AM (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 60 min

at a 10 µM final concentration. The cells were digested with 0.25%

trypsin-EDTA (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA), centrifuged at 1000 rpm for

5 min to eliminate excess dye, washed twice with Ca-free PBS, and finally

resuspended to 0.3 mL with Ca-free PBS. Subsequently, Ca

fluorescence intensity was quantified using the FACS Calibur Flow Cytometer (BD

Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and

emission wavelength of 520 nm. A total of 2 10 cells were

collected, and the intracellular Ca concentration was expressed as mean

fluorescence intensity. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (VX10.6.2,

TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.6 Reactive Oxygen Species

The reactive oxygen species (ROS) Detection Assay Kit (Sigma) was utilized to

determine the intracellular oxidative stress level. Following the manufacturer’s

protocol, the cells were suspended in culture medium at a density of 5

10 cells/mL. Subsequently, 1 µL ROS Detection Reagent Stock Solution

was added to 1 mL culture solution, and it was incubated in a cell incubator with

5% CO at 37 °C, for 30–60 min in the dark. Fluorescence intensity was

measured using the FACS Calibur Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) at an excitation

wavelength of 540 nm and emission wavelength of 570 nm. Then 2

10 cells were collected and the ROS concentration was expressed as mean

fluorescence. Data were analyzed with FlowJo VX10 software.

2.7 Superoxide Dismutase Activity

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) was measured using an assay kit (Sigma). The

superoxide interacts with WST-1 and an electron-coupling reagent to produce the

formazan product. SOD converts superoxide to hydrogen peroxide, yielding a

reduced colorimetric signal at 450 nm. A microplate reader

(BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) was used to measure the optical density value of each

well at a wavelength of 450 nm and calculate the SOD (%) = ([A –

A ] – [A – A ])/(A – A

) 100%. The results were normalized to the protein

concentration.

2.8 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

For mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) assessment, HL-1 cells were prepared

in complete Claycomb Medium at a density of 5 10 cells/mL.

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, 2 µL of 500X MitoTellTM Orange

was added to 1 mL cell solution and incubated in a cell incubator with 5%

CO at 37 °C, for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity was measured using the FACS

Calibur Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) at an excitation wavelength of 540 nm and

an emission wavelength of 590 nm. Then 2 10 cells were collected

and the MMP was expressed as mean fluorescence. Data were processed using FlowJo

VX10 software.

2.9 Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption Rate

To determine the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR), a Seahorse

analyzer (XF96; Agilent Technologies) was used [25, 26]. When cells were 70–80%

confluent, OCR was assessed. Prior to measurement, cells were incubated at 37

°C without CO for 1 h. Basal OCR was initially measured in

triplicate. Subsequently, to inhibit ATP synthase, cells were treated with 1.5

µM oligomycin, and 1.0 µM carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)

phenylhydrazone (FCCP) was added for maximal uncoupled respiration. Next, 0.5

µM rotenone/antimycin A was used to test non-mitochondrial respiration.

ATP-linked respiration was the basal OCR subtracted from the uncoupled (after the

addition of oligomycin). After FCCP addition, the maximum respiratory capacity

was tested, while the spare capacity was calculated by subtracting basal from

FCCP-induced OCR. All Seahorse results were normalized to protein concentration,

which was quantified by the Bradford assay (Solarbio).

2.10 WB Analysis

WB analysis was conducted following previously established protocols [24].

Protein samples were equally loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels

and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes [24]. The membranes were blocked in

5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 °C

with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-actin monoclonal (1:1000,

ab179467; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-p53 polyclonal (1:1000,

ab131442; Abcam), rabbit anti-PGC-1 polyclonal (1:1000, ab54481;

Abcam), rabbit anti-SERCA2a monoclonal (1:1000, ab150435; Abcam), rabbit

anti-NCX1.1 monoclonal (1:1000, ab177952; Abcam), rabbit anti-CaV1.2 monoclonal

(1:1000, ab270987; Abcam), mouse anti-TERT monoclonal (1:500, sc-377511; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). The chemiluminescence detection reagent

(Western Lightning Plus®ECL, N0775330; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA)

showed a specific signal after 2 h of incubation with the appropriate secondary

antibody (A0277, Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

2.11 Statistical Analyses

For statistical evaluation, SPSS version 21.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY,

USA) was employed. The results are expressed as the mean standard error

of the mean. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was utilized to assess the

normality of the data distribution. For comparisons between two groups, the

unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U tests were

applied for normally or non-normally distributed data, respectively. Comparisons

among three groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by

Dunnett’s post hoc test. p 0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

3. Results

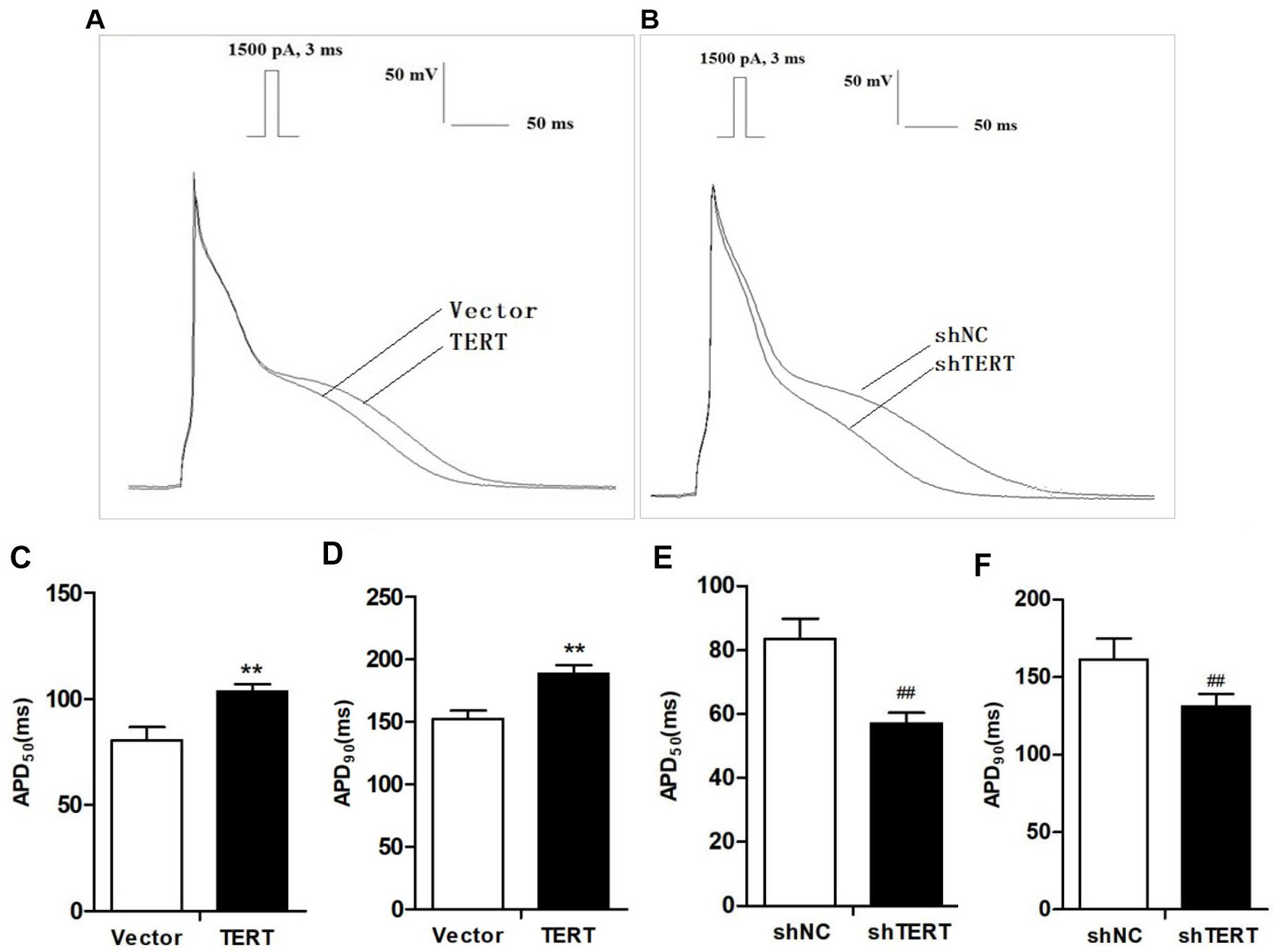

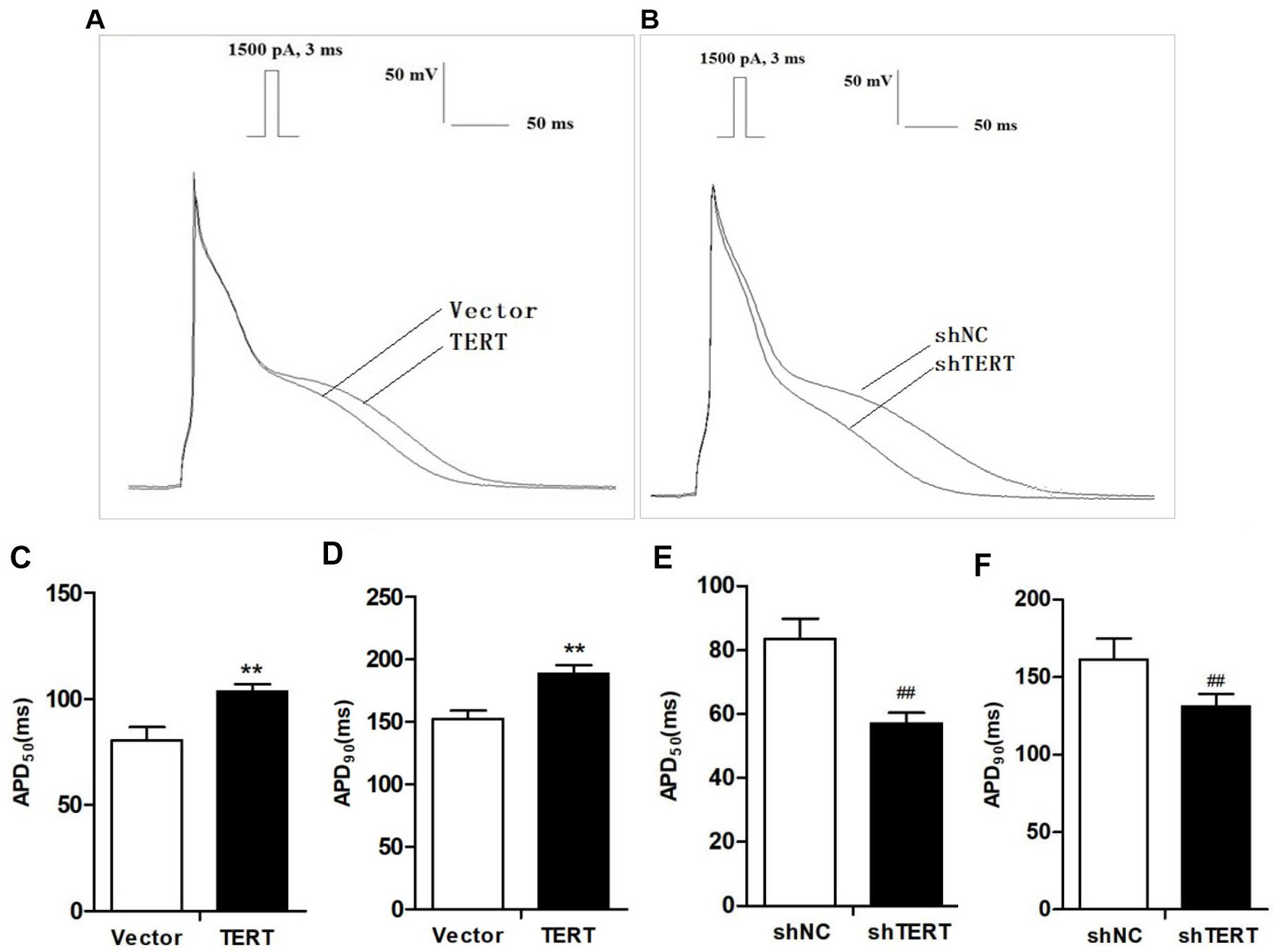

3.1 TERT Regulates the APD

AP was recorded with the patch-clamp technique, and the original AP recording of

the HL-1 cells is shown in Fig. 2A,B. TERT silencing significantly shortened

action potential duration at 50% repolarization (APD) and APD

(Fig. 2E,F). In contrast to silencing, TERT overexpression significantly

prolonged APD, especially APD and APD (n = 10, p 0.01)

(Fig. 2C,D). Neither TERT overexpression nor silencing had a significant impact

on APA and RMP compared to the respective control groups (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of TERT on APD. (A,B) Original recording of the action

potential (AP) in TERT overexpression (A) and TERT-silenced (B) HL-1 cells. (C)

TERT overexpression significantly prolonged APD. (D) APD of the

TERT overexpression group was clearly prolonged compared with the Vector group.

(E) TERT silencing significantly shortened APD. (F) TERT silencing

shortened APD. **p 0.01 vs. Vector group;

p 0.01 vs. shNC group. TERT, telomerase reverse

transcriptase; APD, action potential duration; APD, action potential

duration at 50% repolarization; APD, action potential duration at 90%

repolarization.

Table 1.Effects of TERT on AP parameters in HL-1 cells (n = 10, s).

| Parameters |

Vector |

TERT |

shNC |

| APA (mV) |

110.0 11.2 |

113.5 6.1 |

107.1 5.7 |

| RP (mV) |

–80.1 2.5 |

–79.1 3.5 |

–77.7 2.9 |

| APD (ms) |

12.3 1.0 |

12.0 1.3 |

10.8 1.2 |

| APD (ms) |

80.5 6.2 |

103.4 3.7** |

83.5 6.3 |

| APD (ms) |

152.2 6.7 |

188.4 6.7** |

161.5 13.5 |

**p 0.01 vs. Vector group; p

0.05, p 0.01 vs. shNC group. AP, action potential;

APA, action potential amplitude; RP, resting potential; APD, action potential

duration.

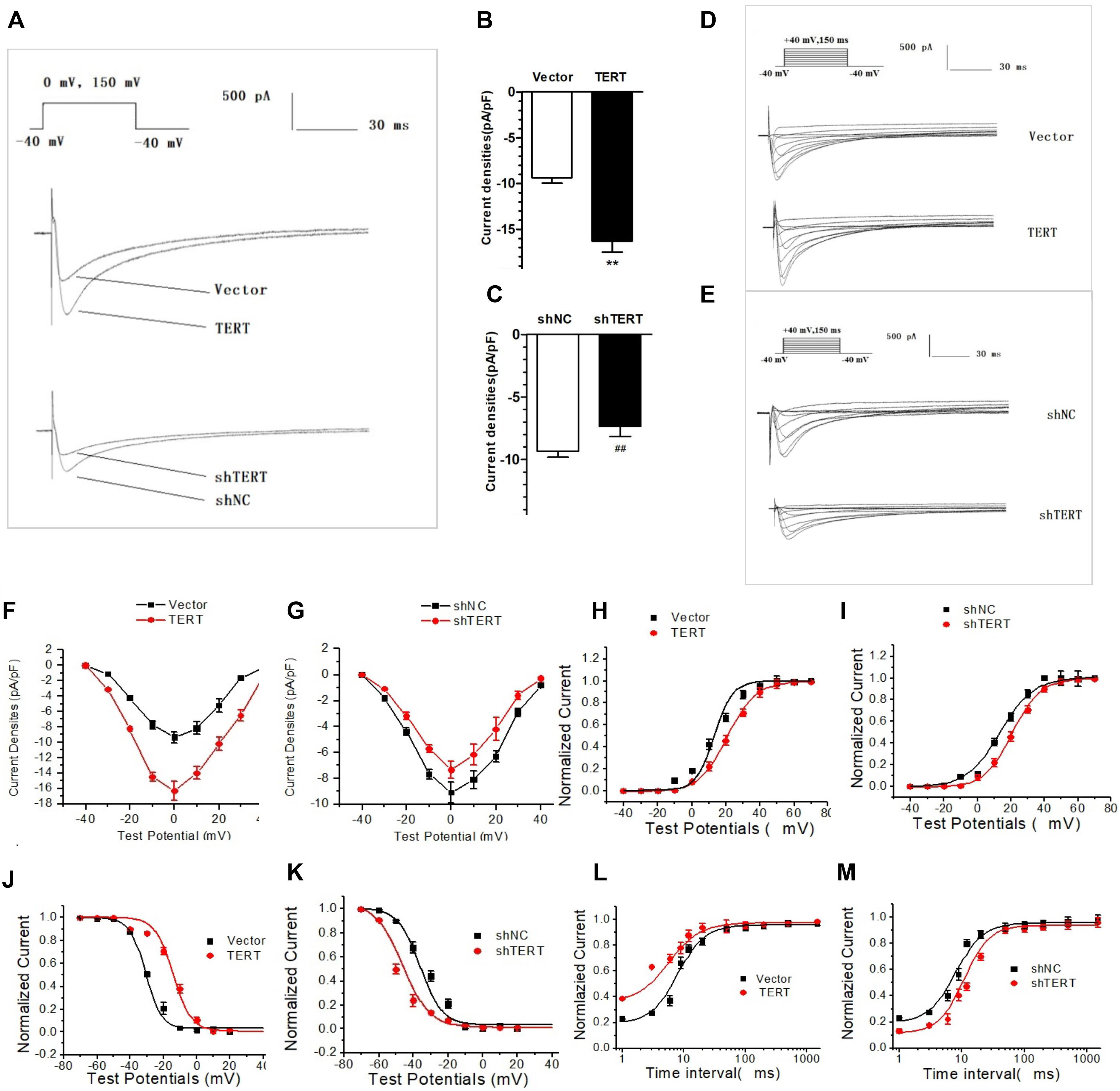

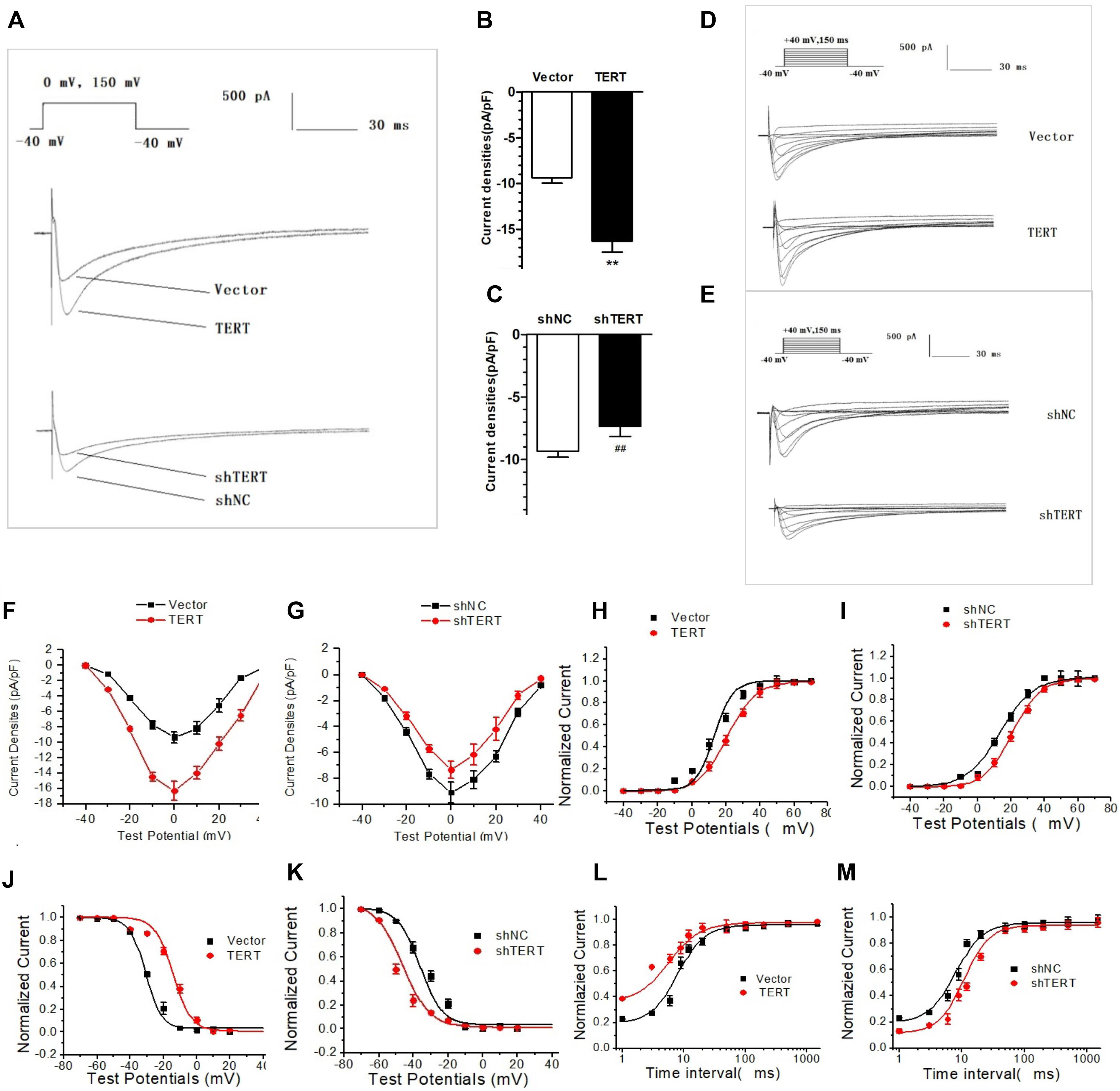

3.2 TERT Regulates L-type Calcium Channel Current and Expression of

the CaV1.2

Previous studies have indicated that a decrease in Cav1.2, accompanied by

reduced I, is a primary pathological change in APD shortening [27, 28].

As demonstrated in Fig. 3A, I amplitude in the TERT-silenced group was

markedly lower compared to the shNC group. Conversely, TERT overexpression

significantly increased I amplitude in HL-1 cells. Furthermore, when the

current amplitude was replaced by current density, we found that silencing TERT

led to a decrease in peak I density from –9.31 0.5 pA/pF to

–7.35 0.8 pA/pF (n = 10, p 0.05; Fig. 3C). For the opposite

condition, the peak I density of the TERT overexpression group (–16.3

1.2 pA/pF) was significantly greater than that of the control group

(–9.35 0.6 pA/pF) at 0 mV depolarization (n = 10, p 0.01;

Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of TERT on I. (A) Original recording of the

effects of TERT on the amplitude of I in HL-1 cells. (B) TERT

overexpression significantly increased the peak I density. (C) Silencing

TERT caused decreased the peak I density. (D,E) Original recording of

the voltage-dependent effect of TERT overexpression (D) and TERT silencing (E) on

I. (F,G) I-V curve of TERT overexpression (F) and TERT silencing (G) in

HL-1 cells. (H,I) The steady-state activation curve of I in TERT

overexpression (H) and TERT silencing (I) group. (J,K) The steady-state

inactivation curve of I in TERT overexpression (J) and TERT silencing

(K) groups. (L,M) I recovery curve after inactivation in TERT

overexpression (L) and TERT silencing (M) groups. **p 0.01

vs. Vector group; p 0.01 vs. shNC group.

TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; I-V curve, current density–voltage

curve.

I was elicited by continuous stimulation, and the changes in I

at each stimulation voltage were observed at the same time (Fig. 3D,E). The I-V

curve was obtained by plotting the current density and stimulation voltage, which

showed a typical “inverted bell” Ca current characteristic (Fig. 3F,G),

indicating that the role of TERT on I is voltage-dependent.

The steady-state activation curve of I showed that the half-activation

voltage shifted to the right in the TERT-silenced group (Fig. 3I), while the

slope of the curve increased in the TERT overexpression group (Fig. 3H), but

neither was statistically significant (p 0.05). These findings

indicated a limited effect of TERT on the steady-state activation of I.

Compared with the control group, the steady-state inactivation curve of

I in TERT-silenced cells shifted to the left, which means that it moved

to the hyperpolarization direction, indicating that channel steady-state

inactivation increased near the resting potential (RP) (Fig. 3K). However, when overexpressing TERT,

the above curve changed to the opposite direction. The steady-state inactivation

curve of I in the TERT overexpression group shifted to the right from

the control group (Fig. 3J), suggesting that the steady-state inactivation of

Ca channels was slowed; that is, the channel inactivation process was

weakened at the same stimulation pulse, which may be the reason for the increase

in current density. These results indicate that TERT may mediate current changes

by altering channel inactivation.

Regarding the effects of TERT on the kinetics of recovery after I

inactivation, we found that when the TERT gene was silenced, the

recovery curve after channel inactivation shifted to the right and the recovery

time was prolonged, indicating that TERT changed the current density by affecting

the recovery kinetics of Ca channels (Fig. 3M). However, the process of

recovery after Ca current inactivation was accelerated in the TERT

overexpression group, suggesting that it may have been another factor for the

current increase (Fig. 3L).

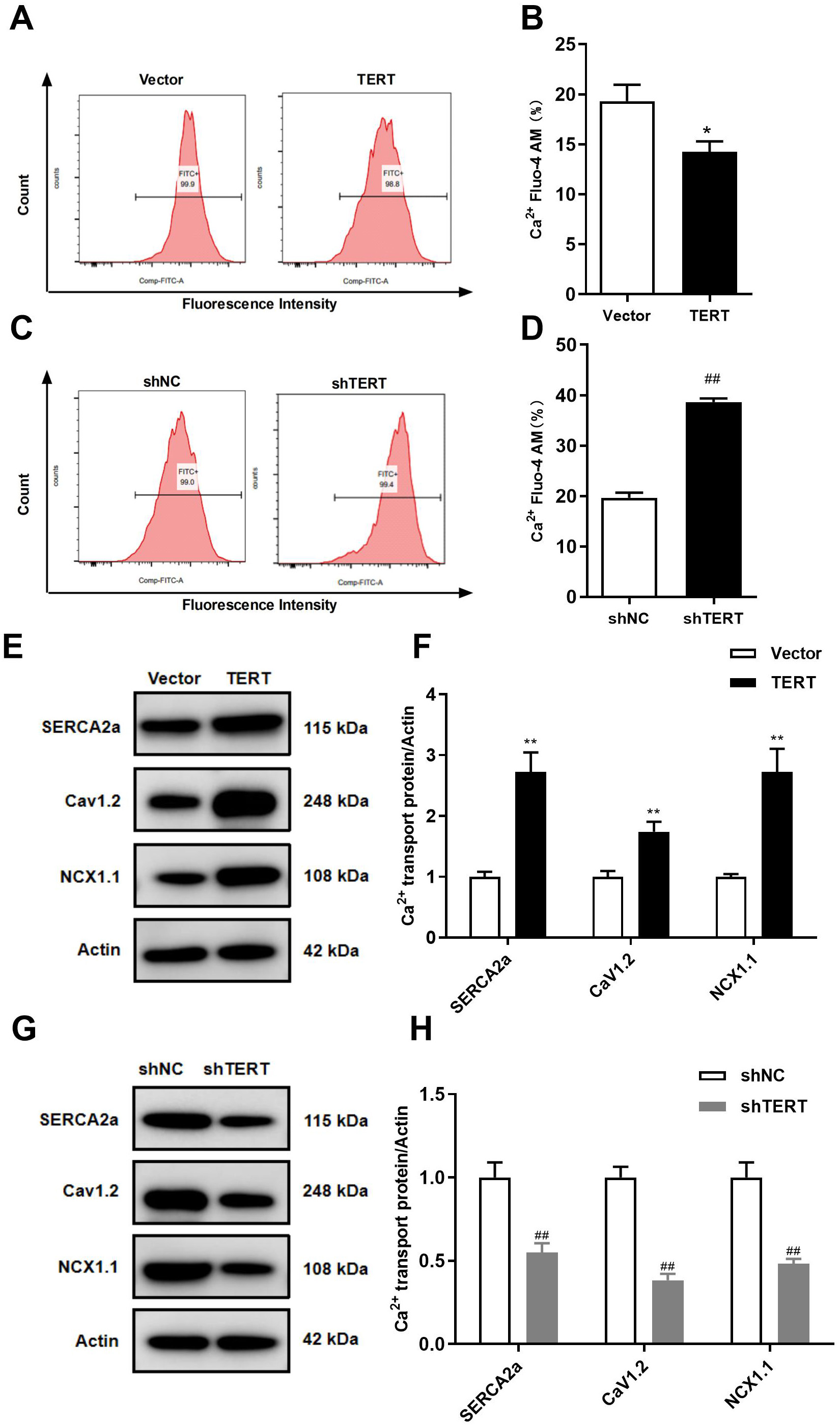

CaV1.2 is linked to Ca inward flow. The expression of CaV1.2 in

TERT-silenced cells was significantly decreased, while TERT overexpression led to

CaV1.2 upregulation (Fig. 4E–H).

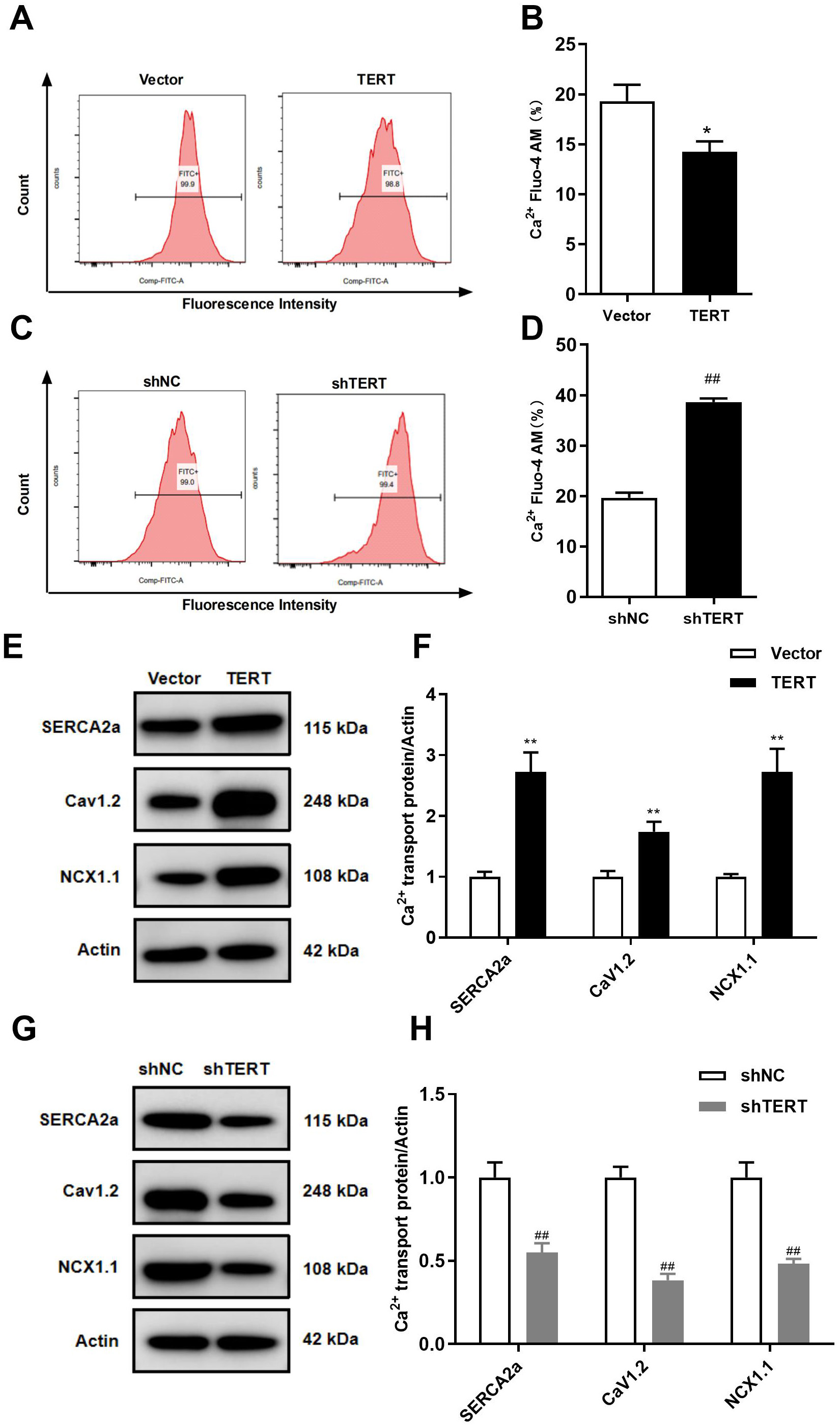

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Effects of TERT on intracellular Ca and Ca transporters. (A) Representative images of Ca concentration in

TERT overexpression HL-1 cells. (B) Intracellular Ca concentration

quantified by mean fluorescence intensity in TERT overexpression HL-1 cells. (C)

Representative images of Ca concentration in TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. (D)

Intracellular Ca concentration quantified by mean fluorescence intensity

in TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. (E,F) WB analyses of the Ca transporter in

TERT overexpression HL-1 cells. (G,H) WB analyses of the Ca transporter in

TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. *p 0.05, **p 0.01

vs. Vector group; p 0.01 vs. shNC group.

TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase.

3.3 TERT Regulate Intracellular Ca

Ca is the most important second messenger in cardiomyocytes, and

abnormally increased intracellular Ca can lead to electrical remodeling,

APD shortening, and a decrease in I. As depicted in Fig. 4C,D, TERT

silencing led to intracellular Ca overload (n = 5, p 0.01).

However, TERT overexpression significantly reduced the intracellular Ca

concentration compared to the control (Fig. 4A,B).

The maintenance of intracellular Ca homeostasis is co-regulated by the

sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca transporter, cell membrane Ca

transporter, and mitochondrial Ca transporter [29]. The concentration of

extracellular Ca is much higher than that of intracellular Ca. When

cells are stimulated, extracellular Ca flows into the cell through the

CaV1.2 Ca channel on the cell membrane, activating the cardiac ryanodine

receptor, RyR2, to release Ca and eventually leading to the contraction of

cardiomyocytes. Subsequently, the vast majority of intracellular free Ca

is recovered by SERCA2a in the SR, and the remaining Ca is transported

extracellularly by NCX1.1. Mitochondria act as intracellular Ca pools

providing a buffering effect on intracellular Ca, and proteins such as

mitochondrial calcium uniporter, mitochondrial calcium uptake 1, and

voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 1 are involved in mitochondrial

Ca uptake [29, 30].

WB analysis revealed that silencing TERT significantly downregulated the

expression of SERCA2a (Fig. 4G), and TERT overexpression upregulated the

expression of SERCA2a (Fig. 4E). The primary role of NCX1.1 in the heart is to

extrude Ca from the cell, countering the Ca that enters the

cytoplasm during systole through CaV1.2 [31]. In this study, we found that

silencing the TERT gene significantly downregulated the expression of

NCX1.1, while TERT overexpression had the opposite effect (Fig. 4E–H). The above

results suggest that telomere shortening decreases Ca uptake and reduces

Ca efflux, ultimately leading to intracellular Ca accumulation.

3.4 TERT Regulates Mitochondrial Function

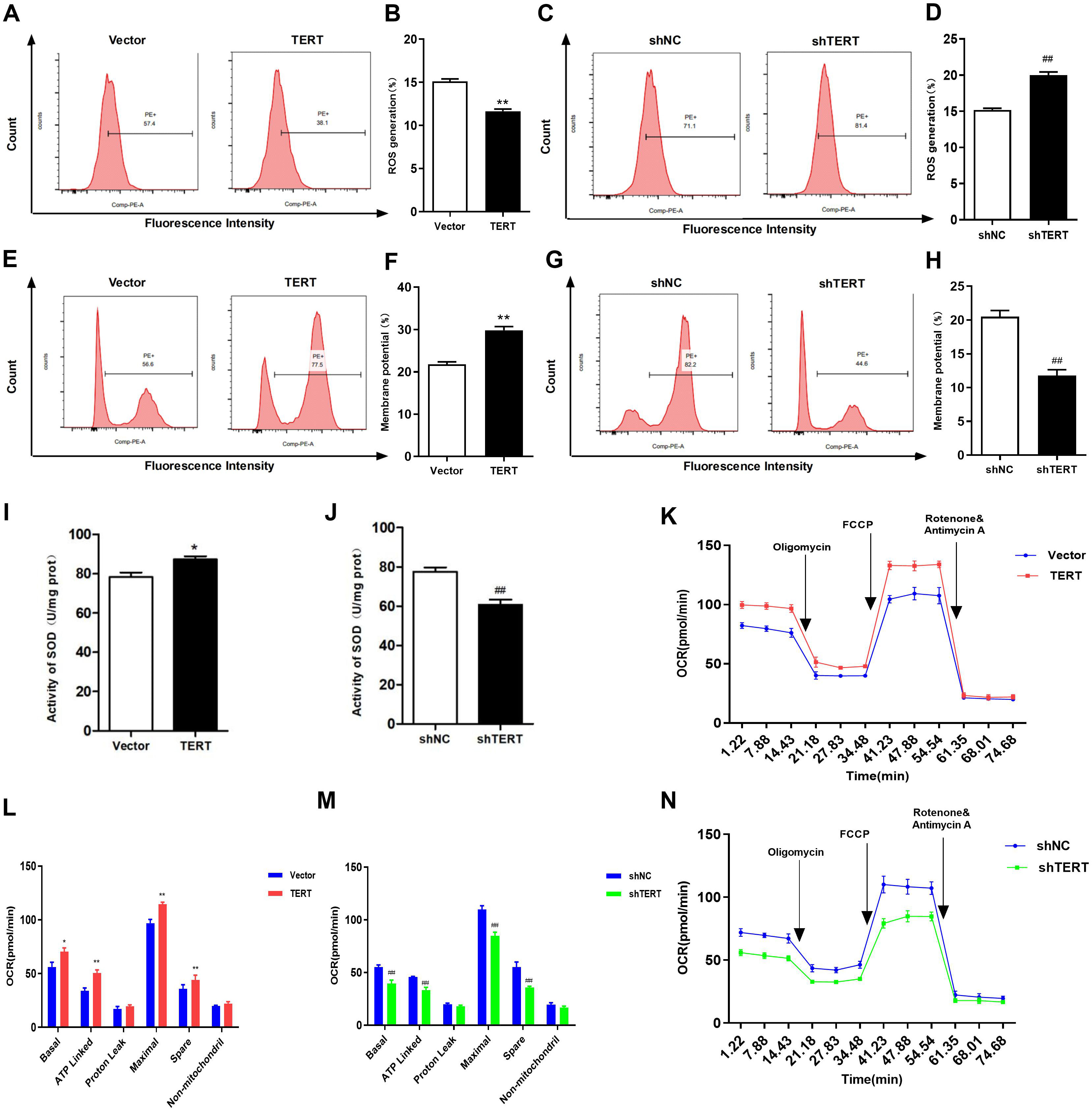

In this study, flow cytometry was used to detect intracellular ROS. As indicated

in Fig. 5C,D, compared with the shNC group, silencing of TERT in HL-1 cells

caused a significant increase in ROS (n = 5, p 0.01). Conversely,

ROS levels in TERT overexpression HL-1 cells was significantly lower compared

with control cells (Fig. 5A,B). SOD is an important member of the intracellular

antioxidant system, and can scavenge harmful ROS to relieve the damage caused by

oxidative stress. Compared with the respective control groups, SOD activity in

the TERT overexpression group was increased, while it was significantly decreased

in TERT-silenced cells (Fig. 5I,J). These findings demonstrate that TERT

silencing can lead to an increase in ROS content and decrease in SOD activity,

consistent with the finding that telomere shortening can lead to increased

oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes [32, 33].

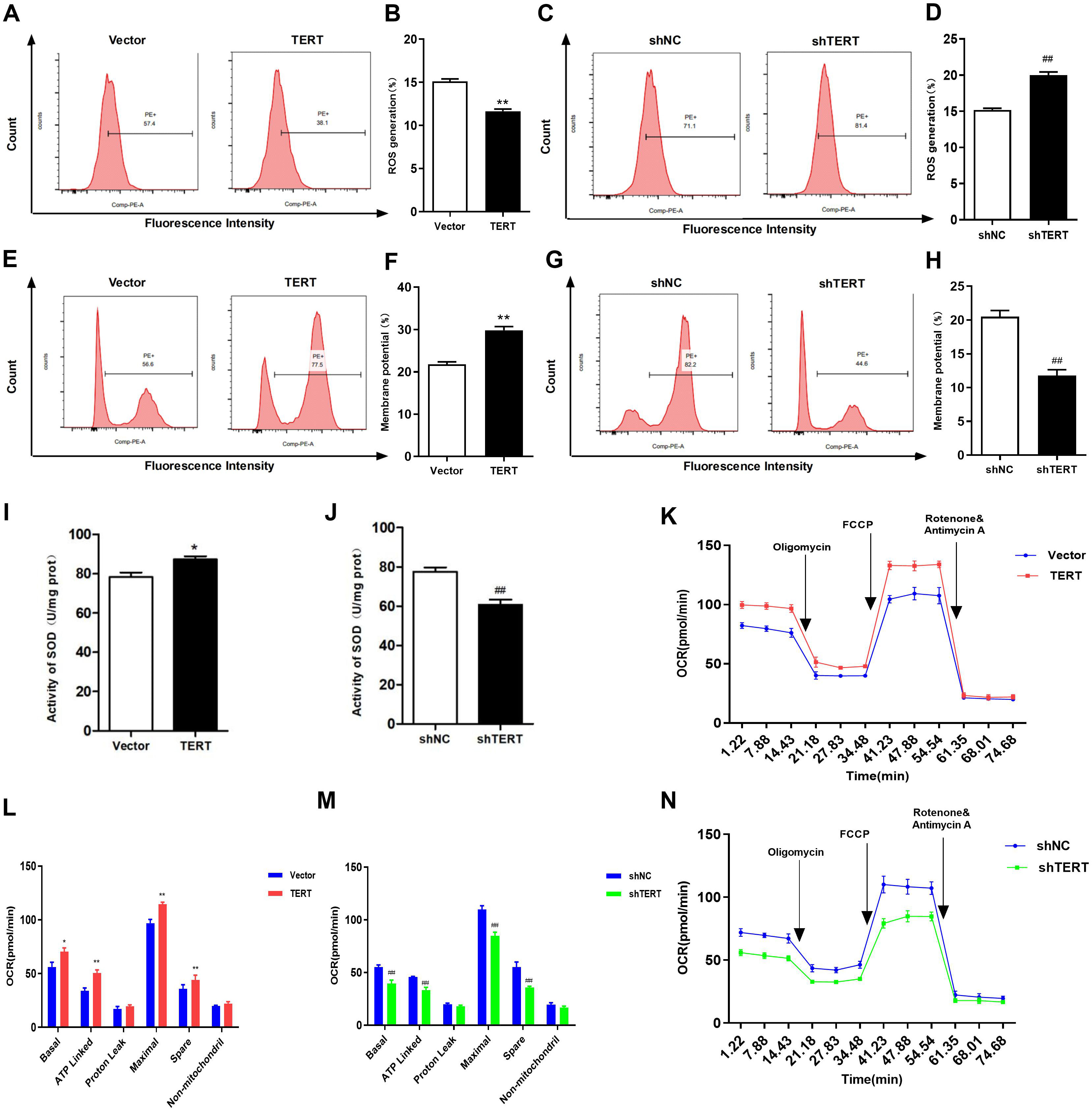

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of TERT on mitochondrial function. (A) Representative

images of ROS detected by flow cytometry in TERT overexpression HL-1 cells. (B)

ROS were quantified and found to be significantly lower in TERT overexpression

HL-1 cells than in the controls. (C) Representative images of ROS detected by

flow cytometry in TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. (D) ROS were quantified and found to

be significantly higher in TERT-silenced HL-1 cells than in the controls. (E)

Representative images of MMP in the TERT overexpression group. (F) Quantification

of MMP in TERT overexpression HL-1 cells. (G) Representative images of MMP in

TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. (H) Quantification of MMP in TERT-silenced HL-1 cells.

(I) SOD activity in TERT overexpression HL-1 cells was higher than that in the

control group. (J) Silencing of TERT significantly decreased SOD activity. (K)

OCR curve of TERT overexpression HL-1 cells. (L) The OCR of TERT overexpression

HL-1 cells. (M) OCR curve of TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. (N) The OCR of

TERT-silenced HL-1 cells. *p 0.05, **p 0.01 vs.

Vector group; p 0.01 vs. the shNC group. TERT,

telomerase reverse transcriptase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MMP,

mitochondrial membrane potential; SOD, superoxide dismutase; OCR, oxygen

consumption rate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; FCCP, Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone.

The MMP is a crucial indicator of mitochondrial function. A decrease in MMP is

often observed in the early stages of apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5G,H, silencing

of TERT caused a significant decrease in MMP (n = 5, p 0.01);

however, in TERT overexpression HL-1 cells, the MMP was higher than that in the

control cells (Fig. 5E,F). In this study, TERT silencing resulted in a decrease

in OCR in HL-1 cells, with a significant decrease in basal OCR, ATP-linked OCR,

maximal OCR, and reserve OCR (Fig. 5M,N). Conversely, the OCR of TERT

overexpression HL-1 cells was higher than that of the control, and the basal OCR,

ATP-linked OCR, maximal OCR, and reserve OCR were significantlyincreased

(p 0.01). Besides, proton leak OCR and non-mitochondrial OCR were

also increased, with no statistical difference compared with the control group

(Fig. 5K,L). In summary, TERT silencing led to impaired mitochondrial function,

increased ROS production, and decreased OCR, MMP, and SOD activity.

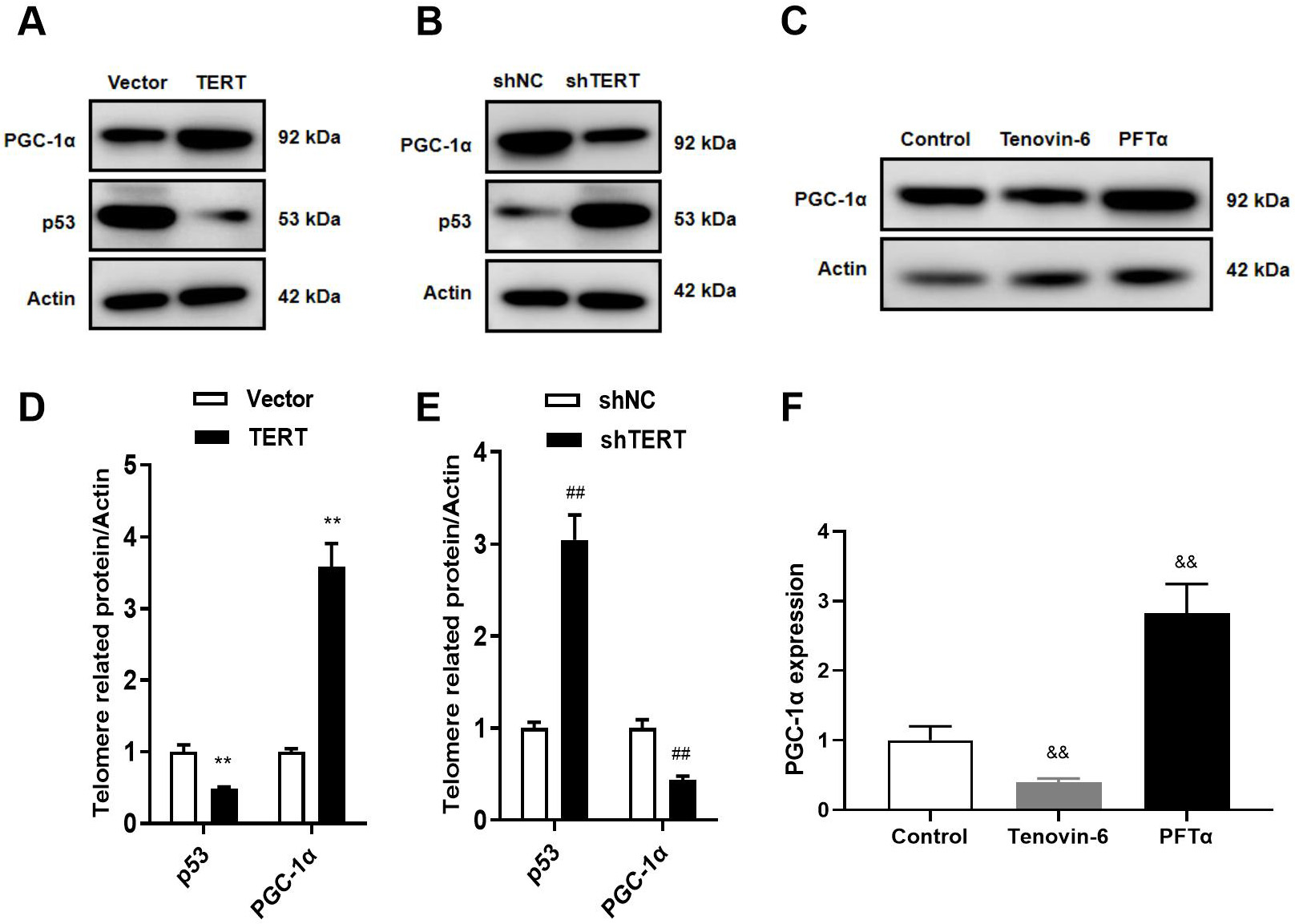

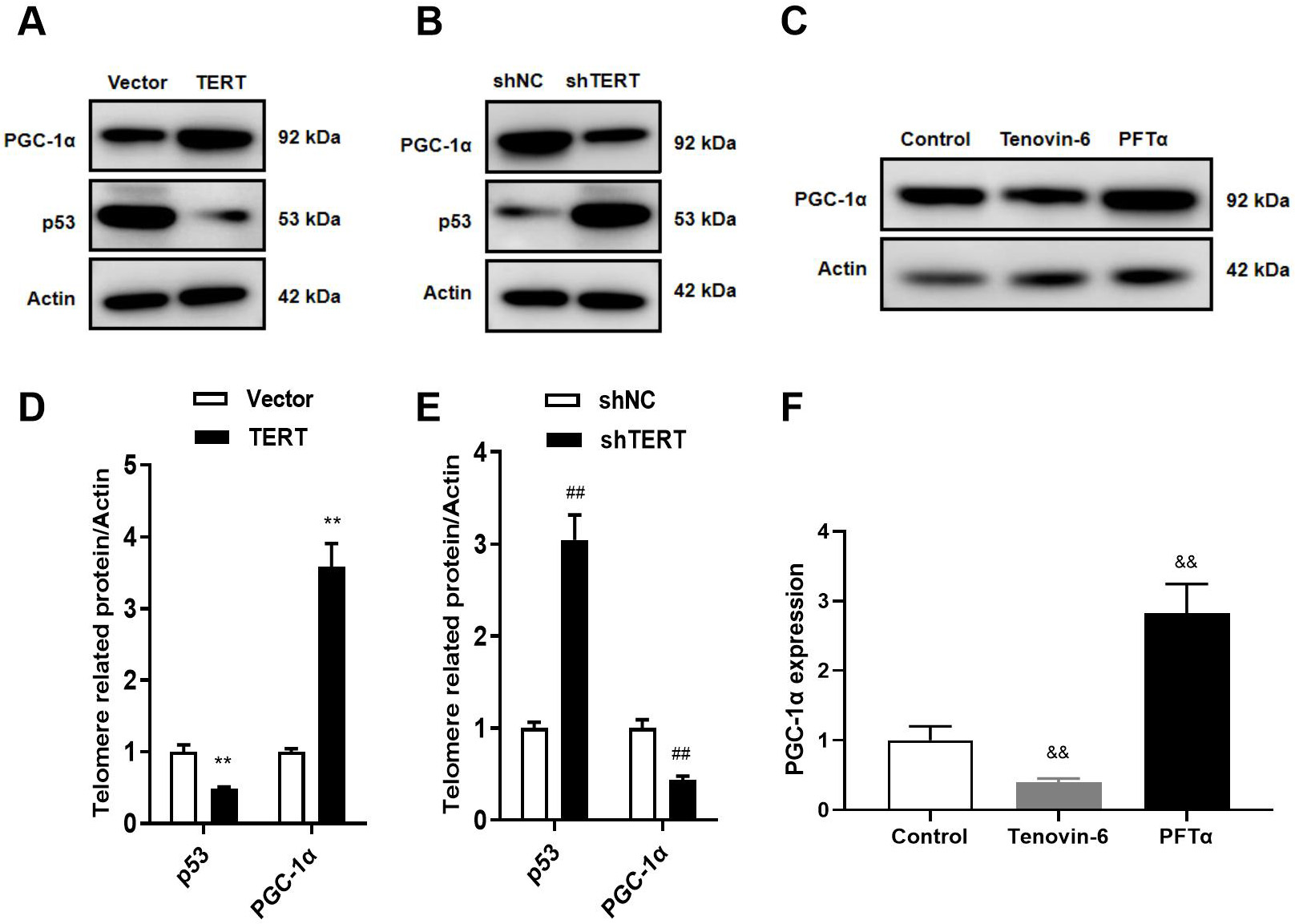

3.5 TERT Regulates the p53/PGC-1 Pathway

Telomere shortening leads to intracellular Ca overload and dysfunction of

mitochondria via the p53/PGC-1 pathway [7, 8, 18, 19]. To validate this

pathway, we intervened the molecules on upstream of the regulatory axis. It is

noteworthy that the expression of p53 was upregulated and the level of

PGC-1 was downregulated in TERT-silenced cells (Fig. 6B,E). Conversely,

TERT overexpression decreased p53 expression and increased PGC-1

expression in HL-1 cells (Fig. 6A,D). Subsequently, we treated HL-1 cells with

the p53 agonist Tenovin-6 and inhibitor PFT. The results showed that

treatment with PFT upregulated the expression of PGC-1, while

Tenovin-6 downregulated expression (Fig. 6C,F). These results suggest that TERT

regulates the p53/PGC-1 pathway in atrial myocytes.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

TERT regulates the p53/PGC-1 pathway. (A,D) WB in

TERT-overexpressed cells. (B,E) WB in TERT-silenced cells. (C,F) WB after

treatment with the p53 agonist Tenovin-6 and inhibitor PFT. **p 0.01 vs. Vector group; p 0.01 vs.

shNC group; p 0.01 vs. Control group. TERT,

telomerase reverse transcriptase; PGC-1, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha.

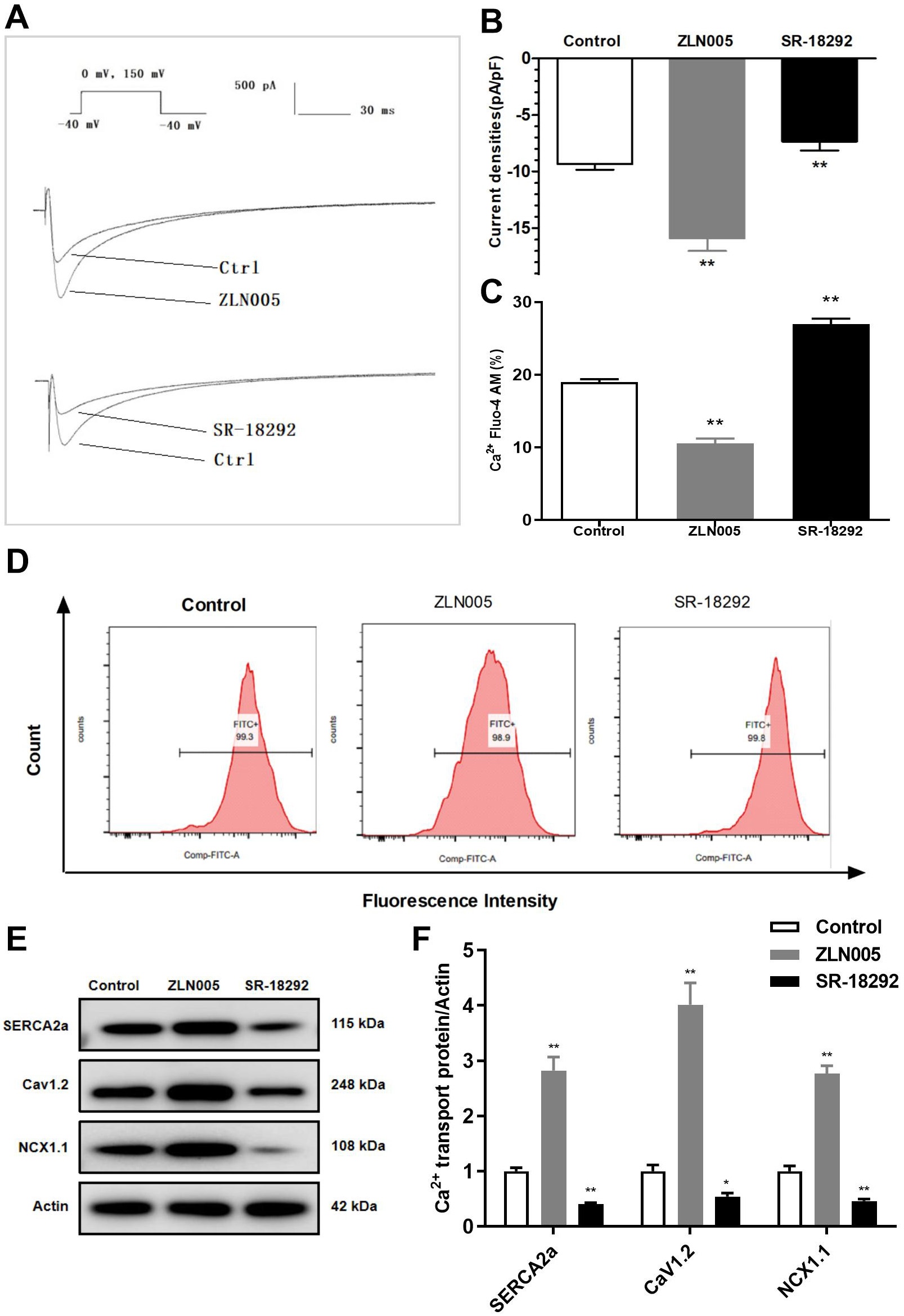

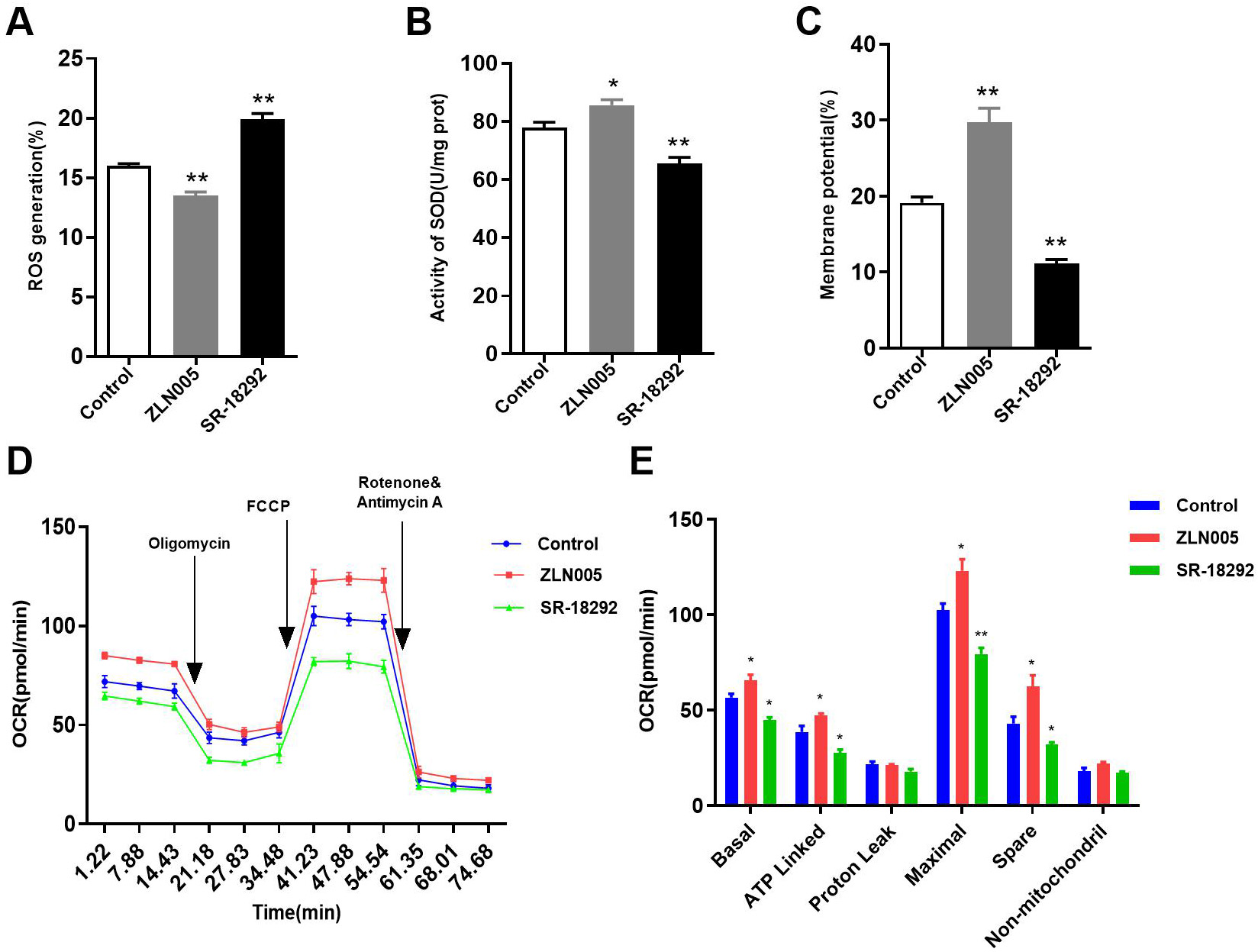

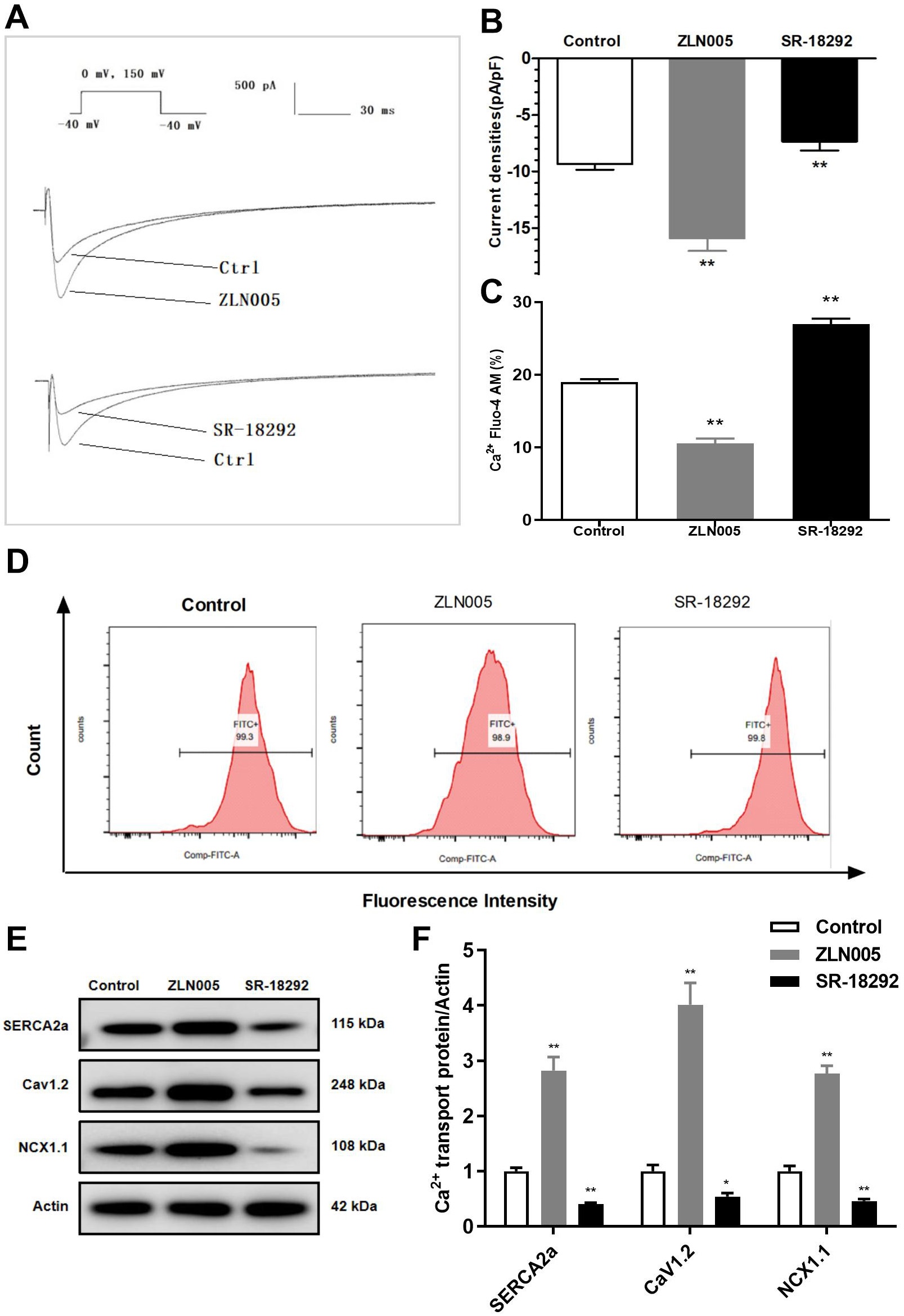

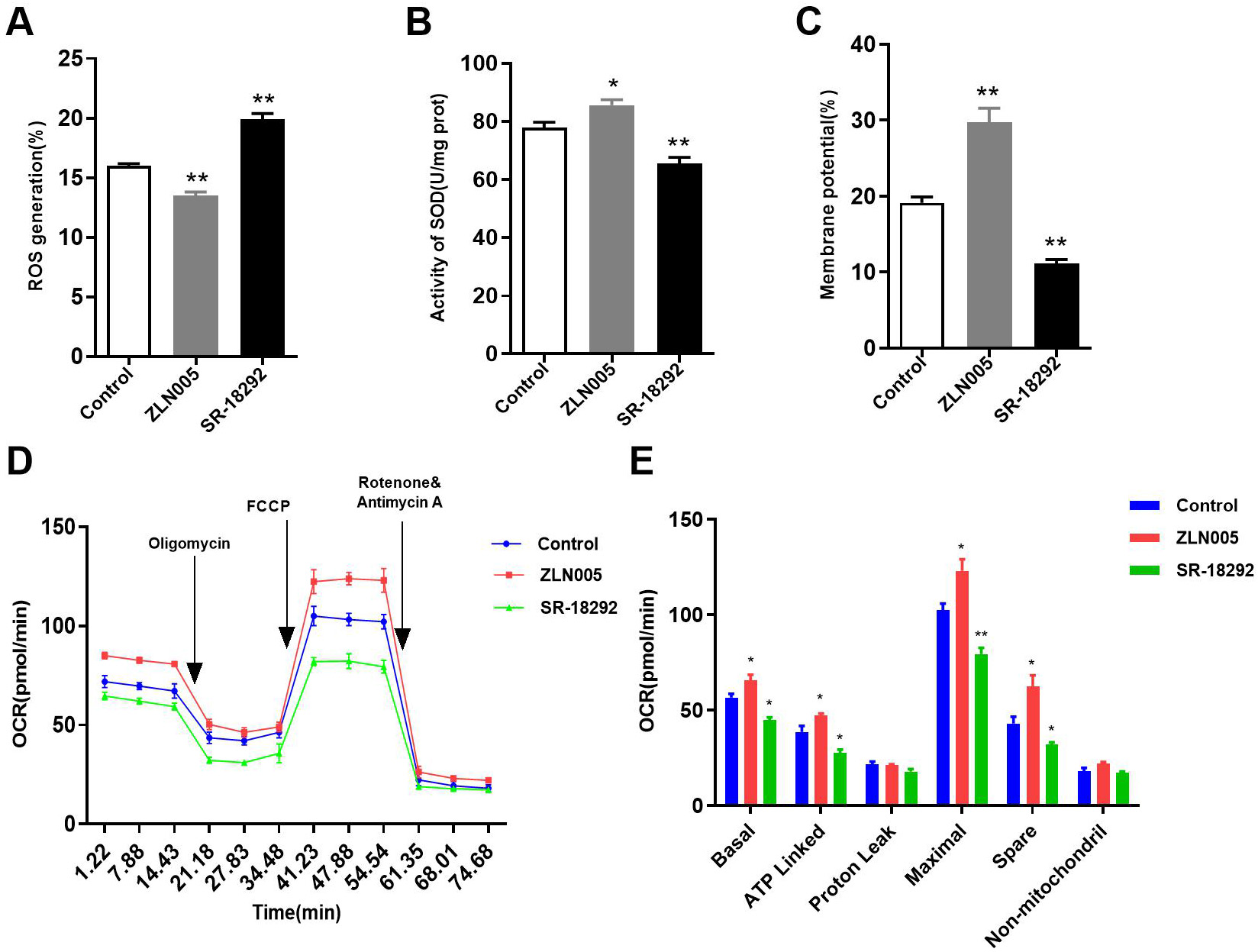

3.6 PGC-1 Regulates Intracellular Ca and Induces

Electrical Remodeling

PGC-1 is known for its role in mitochondrial biosynthesis, but its

effect on intracellular Ca has been less studied. In this study, we

treated HL-1 cells with the PGC-1 agonist ZLN005 and PGC-1

inhibitor SR-18292 to observe their effects on cellular electrophysiology,

intracellular Ca, and Ca transporters. The results showed that the

SR-18292 led to decreased I, intracellular Ca overload, increased

ROS, and decreased MMP, OCR, and SOD activity. In addition, the expression of

SERCA2a, CaV1.2, and NCX1.1 was downregulated (Figs. 7,8). However, ZLN005

treatment increased I (Fig. 7A,B) and decreased intracellular Ca

levels (Fig. 7C,D). Additionally, ZLN005 upregulated the expression of SERCA2a,

CaV1.2, and NCX1.1 (Fig. 7E,F). Furthermore, we also found that ZLN005 reduced

ROS levels and increased SOD activity, MMP, and OCR compared with the control

group (Fig. 8). These results indicate that ZLN005 has similar effects as TERT

overexpression, and coculture with SR-18292 resulted in similar effects as TERT

silencing. Therefore, PGC-1 may be a new target for the treatment of

cardiovascular diseases.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Effects of PGC-1 on I, intracellular

Ca, and Ca transporters. (A) Original record of I. (B)

Role of PGC-1 on I current density. (C) Quantification of

intracellular Ca. (D) Representative images of Ca concentration

detected by flow cytometry. (E,F) WB analyses of Ca transporters.

*p 0.05, **p 0.01 vs. Control group.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Effects of PGC-1 on mitochondrial function. (A) Role

of PGC-1 on ROS. (B) Role of PGC-1 on SOD activity. (C) Role

of PGC-1 on MMP. (D) The OCR curve of HL-1 cells treated with ZLN005

and SR-18292. (E) Effects of PGC-1 on the OCR. *p 0.05,

**p 0.01 vs. Control group. ROS, reactive oxygen species;

SOD, superoxide dismutase; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; OCR, oxygen

consumption rate; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone;

ATP, adenosine triphosphate.

4. Discussion

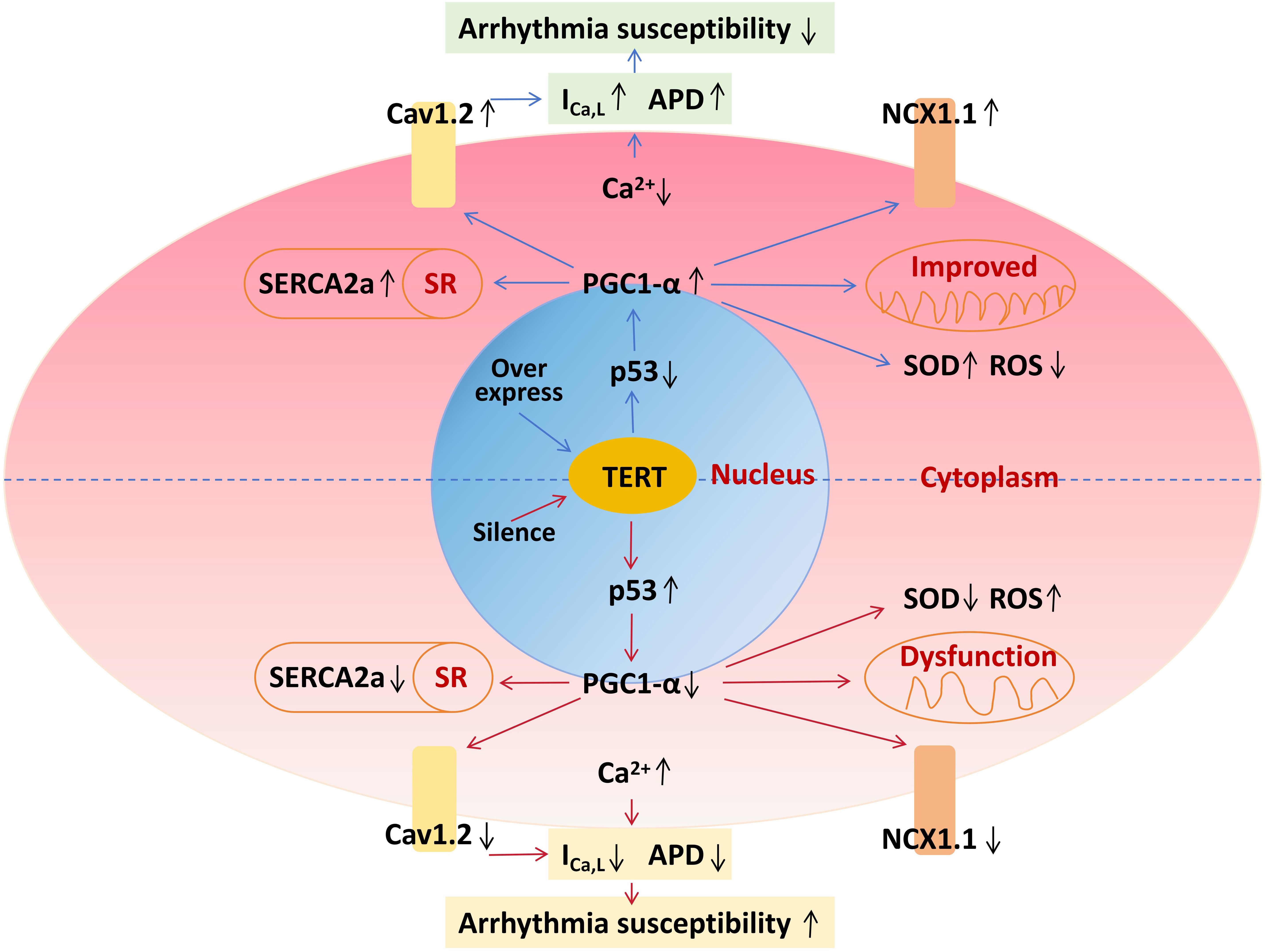

In this study, we demonstrated that TERT silencing led to intracellular

Ca overload, shortened APD, and decreased I, forming a critical

electrophysiological basis for arrhythmias (Fig. 9). Conversely, TERT

overexpression not only prevented the induction of arrhythmias but also appeared

to reduce the risk of arrhythmia, suggesting its safety in treating cardiac

diseases. Additionally, we established that TERT regulates intracellular

Ca homeostasis and mitochondrial function via the p53/PGC-1

pathway. Finally, we found that PGC-1 is a key downstream effector

molecule of TERT, and for the first time, we explored the role of PGC-1

in atrial myocyte electrophysiology. We found that PGC-1 has potential

as a novel target for arrhythmia intervention, such as in AF, suggesting that

intervention for AF should not be limited to abnormal cation handling.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Schematic diagram of TERT on cell electrophysiology. TERT,

telomerase reverse transcriptase; PGC-1, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; APD, action potential

duration; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

The therapeutic potential of TERT overexpression in various cardiac diseases has

been recognized, but previous research has focused primarily on the effects on

disease, and there are no reports on the effects of TERT on the electrophysiology

of cardiomyocytes [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Our study, conducted on mouse atrial myocytes,

demonstrated that TERT overexpression can improve cellular mitochondrial

function, reduce intracellular Ca accumulation, and prolong APD,

indicating a potential for reducing arrhythmia risk. Chen et al. [34]

found that growth differentiation factor 11 alleviated myocardial I/R injury by

activating TERT and improving mitochondrial function, consistent with our

findings. Similarly, Chatterjee et al. [12] observed that overexpression

of TERT attenuated the cardiotoxic effects of doxorubicin, possibly through

mitochondrial function enhancement. AF is a common age-related disease, the

prevalence of which increases significantly with age, but its pathogenesis is not

fully understood, with most studies showing an association with telomere

shortening [1, 2, 35, 36]. It has been reported that telomere length and telomerase

activity may serve as predictors of AF recurrence after radiofrequency ablation

and as indicators of arrhythmias in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy

[35, 37]. Our findings indicate that TERT silencing can lead to the overloading of

intracellular Ca, shortening of APD, amd decrease of I, which are

crucial electrophysiological underpinnings for AF, suggesting an important role

for TERT in age-associated AF.

TERT regulates intracellular Ca homeostasis and mitochondrial function

via the p53/PGC-1 pathway in HL-1 cells. Sahin et al. [8]

observed that telomere shortening in mouse cardiomyocytes was accompanied by

increased p53 protein expression and decreased PGC-1 expression,

leading to mitochondrial oxidative stress and an increase in ROS generation.

Those results led them to propose the “Telomere/p53/PGC-1 regulatory

axis” concept [7], which has been verified by other studies [18, 38, 39]. Given

that TERT is the rate-limiting enzyme of telomerase and directly determines

telomere length, we hypothesized that TERT could regulate intracellular Ca

and mitochondrial function through the p53/PGC-1 pathway. Our findings

support this hypothesis, revealing that TERT silencing upregulated p53 and

downregulated PGC-1. Treatment with the p53 agonist Tenovin-6 decreased

PGC-1 expression, while TERT overexpression and PFT treatment

had the opposite effects. These results suggest that TERT may act through the

p53/PGC-1 pathway.

PGC-1 can directly or indirectly reduce intracellular Ca by

inhibiting cellular oxidative stress [20, 21]. By contrast, p53 has the opposite

effect on intracellular Ca [40]. Birket et al. [41] found that

PGC-1 knockdown mice had increased systolic Ca and Ca

transients. Summermatter et al. [42] demonstrated that PGC-1

reduced Ca release from the SR of skeletal muscle cells. Additionally, as

a key regulator of mitochondrial function, PGC-1 also reduced oxidative

stress by decreasing mitochondrial ROS production, thereby lowering intracellular

Ca levels [43]. In our study, we observed that TERT silencing led to

intracellular Ca overload by altering Ca transporter protein

expression and gated channel inactivation, shortening APD, and decreasing

I, which culminated in the electrical remodeling of atrial myocytes.

Taken together, our study confirms that TERT regulates intracellular Ca

homeostasis and mitochondrial function via the p53/PGC-1 pathway in

HL-1 cells.

PGC-1 shows promise for treating heart diseases such as AF.

PGC-1 is a key factor in mitochondrial energy metabolism. The

disturbance of mitochondrial energy production will lead to abnormal electrical

conduction and Ca imbalance, which will directly lead to the reduction of

ATP production, slow down the local electrical signal conduction in the

myocardium, enhance the heterogeneity, and promote the occurrence of AF. In

addition, insufficient ATP synthesis will also affect the opening of ion

channels, such as the Na/K pump and ATP-dependent Ca pump,

leading to intracellular Ca overload and promoting the occurrence and

maintenance of AF [32]. By comparing the preoperative and postoperative serum

PGC-1 levels of patients with coronary artery bypass graft surgery

(CABG), Jeganathan et al. [44] found that the PGC-1 level in

patients with postoperative AF was significantly lower than that before surgery

(p = 0.002), suggesting that serum PGC-1 level can be used as

a predictor of new-onset AF after CABG. We previously found that the serum level

of PGC-1 was lower in patients with AF than in controls in an elderly

male population [36]. Li et al. [45] found that the PGC-1

agonist ZLN005 protected cardiomyocytes from high glucose-induced cytotoxicity in

neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. Liu et al. [46] found in human

pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes that treatment with ZLN005 could

upregulate the expression of mitochondrial function-related genes and promote

energy metabolism, while improving cellular Ca handling capacity and

enhancing intercellular connectivity. Xu et al. [47] confirmed in PC12

cells and rats that ZLN005 can upregulate the expression of antioxidant genes

SOD1 and heme oxygenase 1, improve the activity of SOD, and effectively improve

neuronal damage caused by ischemia. However, treatment of AF with PGC-1

has not been reported. In our study, we found that PGC-1 inhibitors

cause intracellular Ca overload and impaired mitochondrial function in

atrial myocytes, leading to electrical remodeling, a result similar to the effect

of TERT silencing. By contrast, PGC-1 agonists exerted opposite

effects. These findings offer theoretical support for the feasibility of

PGC-1 interventions in AF treatment.

This study had several potential limitations worth noting. First, while studying

cellular Ca homeostasis, our focus was on changes in the expression of

Ca transporters without assessing their activity, which are susceptible to

external environmental factors. Second, our discussion of mechanisms primarily

revolved around Ca dynamics; however, other ions such as K and

Na also warrant further exploration. Finally, this study was only conducted

at the cellular level, and the findings were not validated in animal experiments.

Since in vivo experiments are influenced by more factors than in

vitro, the effectiveness and mechanisms need to be further explored.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that TERT regulated intracellular Ca homeostasis

and mitochondrial function via the p53/PGC-1 pathway in HL-1 atrial

myocytes, which might be one mechanism of age-related AF. Additionally, we

confirmed that TERT overexpression was safe and did not increase the risk of

arrhythmia. Finally, we verified the effects of PGC-1 on intracellular

Ca and expression of the Ca transporter protein in vitro.

The results suggest that PGC-1a might be a novel target for AF and intervention

for AF should not be limited to abnormal cation handling.

Abbreviations

TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; APD, action potential duration;

I, L-type calcium currents; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; OCR,

oxygen consumption rate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; AF, atrial fibrillation;

CHD, coronary heart disease; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; PGC-1, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1; WB, western blot; AP, action

potential; APA, action potential amplitude; RMP, resting membrane potential;

FCCP, carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone; shRNA, small hairpin

RNA; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Availability of Data and Materials

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the

article/supplementary material, and further inquiries can be directed to the

corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CL, KL, QX, and YL designed the research study. ZX, YC, DL, JF, NL and XW

performed the research. YC, SG and QX analyzed the data. CL, ZX, QX and YL wrote

the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated

sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the

work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by National Nature Science Foundation of China

(82200366, 82370327), Beijing Nova Program (20220484020), Young Talent Project of

Chinese PLA General Hospital (20230433).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.