1 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Massey Cancer Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298, USA

2 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kafrelsheikh University, 33516 Kafrelsheikh, Egypt

Abstract

The inhibitors of mammalian target of rapapmycin (mTOR), everolimus, temsirolimus and rapamycin, have a wide range of clinical utility; however, as is inevitably the case with other chemotherapeutic agents, resistance development constrains their effectiveness. One putative mechanism of resistance is the promotion of autophagy, which is a direct consequence of the inhibition of the mTOR signaling pathway. Autophagy is primarily considered to be a cytoprotective survival mechanism, whereby cytoplasmic components are recycled to generate energy and metabolic intermediates. The autophagy induced by everolimus and temsirolimus appears to play a largely protective function, whereas a cytotoxic function appears to predominate in the case of rapamycin. In this review we provide an overview of the autophagy induced in response to mTOR inhibitors in different tumor models in an effort to determine whether autophagy targeting could be of clinical utility as adjuvant therapy in association with mTOR inhibition.

Keywords

- autophagy

- cytoprotective

- cytotoxic

- rapamycin

- everolimus

- temsirolimus

- mTOR

This paper in one of a series of publications [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] that investigate the versatile roles of the autophagic machinery induced in response to various anti-neoplastic modalities. The ultimate goal of these articles is to investigate whether there are pre-clinical studies, and, where available, clinical trials, that support targeting or modulating autophagy as an adjuvant therapy to improve therapeutics outcome. The focus of this article is on the role(s) of autophagy induced in response to the clinically utilized mammalian target of rapapmycin (mTOR) inhibitors.

Autophagy is a survival mechanism whereby misfolded proteins and other damaged cytoplasmic components are recycled, thereby generating energy and metabolic intermediates to maintain cellular homeostasis [3, 5]. Three major forms of autophagy are evidenced in eukaryotic cells, macro-autophagy, which is commonly referred to as autophagy, micro-autophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy [9]. The three forms function through different mechanisms; in micro-autophagy, cargo is directly taken up by lysosomes and late endosomes through membrane protrusion and invagination, where the engulfed cargo is then degraded in the endo-lysosomal lumen [10]. On the other hand, in chaperone –mediated autophagy, the cytosolic cargo with KFERQ-like motifs is recognized by the chaperone protein HSPA8, then transported by lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP2A) and lysosomal HSPA8 to lysosomes for degradation [10]. The initiation of macro-autophagy, referred to as autophagy throughout the text, is controlled by various signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MAPK as well as AMPK [11]. The autophagic machinery is comprised of five major steps: initiation, nucleation, autophagosomes formation, and fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes, forming the autolysosome (or autophagolysosome) in which the cargo degradation, the last step, takes place [3, 4]. The role of autophagy in cancer has been investigated quite extensively, with four functional forms of autophagy having been identified in various experimental tumor models, specifically the cytotoxic, cytostatic, non-protective as well as cytoprotective forms [12]. The latter form, which contributes to the survival of the tumor population, is investigated extensively in the scientific literature in response to a spectrum of anti-neoplastic agents, including tamoxifen [13], cisplatin [14] and temozolamide [15]; however, the cytotoxic form, which upon activation leads to cell death, is also detected in response to various agents including chlorpromazine in glioma cells [16], colchicine derivatives [17, 18] and trastuzumab emtansine [19]. The non-protective and cytostatic forms of autophagy, that have emerged in various studies [12, 20, 21, 22], will require more extensive investigation to clearly understand their potential involvement in the tumor response to anti-neoplastic agents. Autophagy targeting, in the case of cytoprotective autophagy, could potentially increase the clinical effectiveness of various chemotherapeutic modalities, in part, by overcoming drug resistance. Clinical trials are currently in various stages investigating the possible utilization of autophagy inhibitors, most prominently, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), in combination with various chemotherapeutic agents as adjuvant therapy [6, 7].

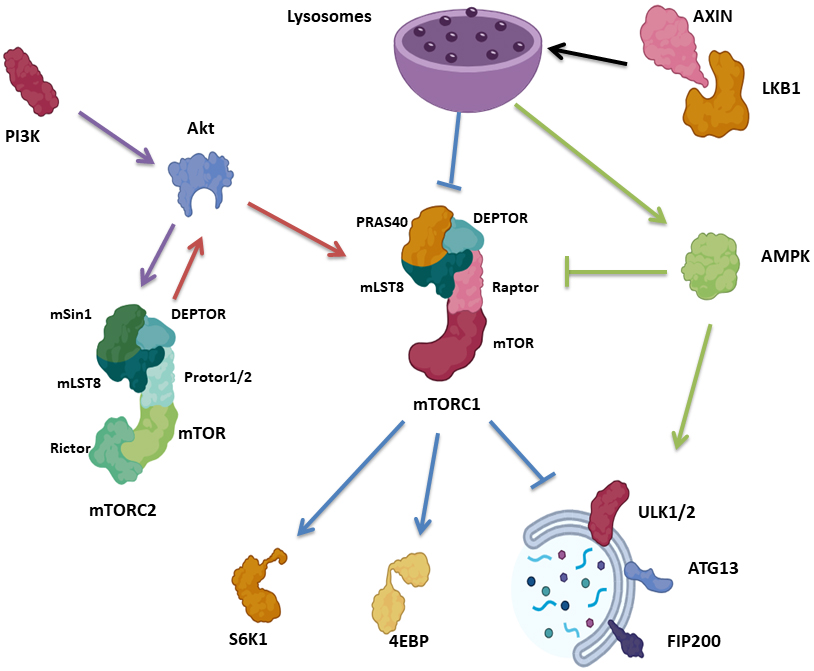

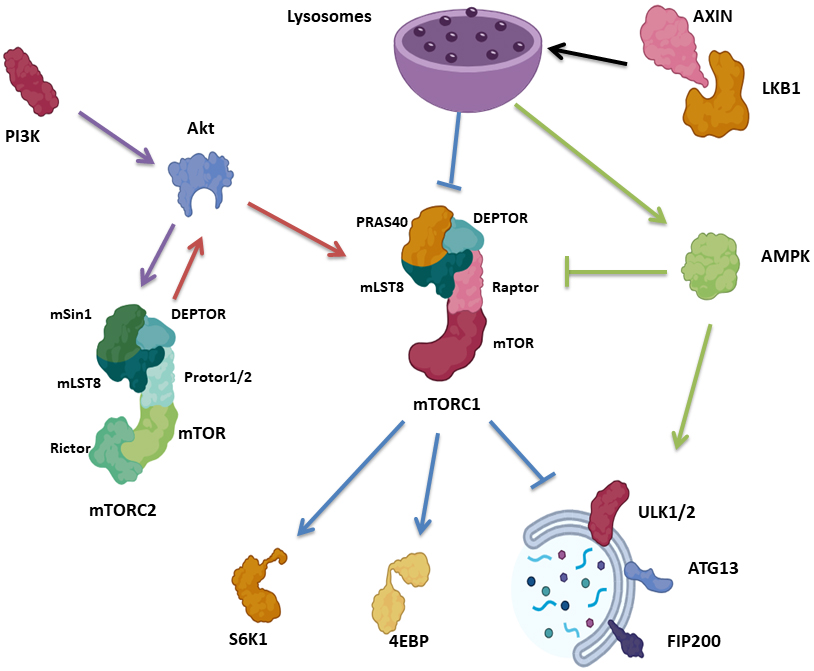

One of the major signaling molecular pathways know to regulate the initiation of autophagy is the mammalian target of rapapmycin (mTOR) [4]. mTOR, the catalytic subunit of mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) and 2 (mTORC2) [23], is a serine/threonine kinase belonging to the PI3K-related kinase (PIKK) family that is highly responsive to starvation and nutrient deprivation It consists of three core units: mTOR, Raptor, a regulatory protein associated with mTOR that facilitates substrate recruitment and maintenance of the cellular localization of mTORC1, as well as mammalian lethal with Sec13 protein 8 (mLST8), which stabilizes the kinase activation loop [24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. mTORC1 contains two additional inhibitory subunits, proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40) and DEP domain containing mTOR interacting protein (DEPTOR) [29, 30] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Autophagy signaling pathways associated with mTOR. mTORC1 consists of mTOR, Raptor, mLST8, PRAS40 and DEPTOR, while mTORC2 consists of mTOR, mLST8, Rictor, DEPTOR, mSin1 and Protor1/2. mTORC1 control protein synthesis via S6K1 and 4EBP. Upon nutrient deprivation, AXIN translocates to the lysosomal surface, in combination with LKB1, activating AMPK and suppressing mTORC1. mTORC1 suppresses autophagy via phosphorylation of ULK1/2, ATG13 as well as FIP200. mTORC2 block autophagy indirectly in response to PI3K/Akt, where mTORC2 phosphorylate Akt, which in turn activate mTORC1. AMPK initiates autophagy via ULK1 activation, as well as suppressing mTORC1. mTORC1, mammalian target of rapapmycin complex 1; mLST8, mammalian lethal with Sec13 protein 8; PRAS40, proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa; DEPTOR, DEP domain containing mTOR interacting protein; mTORC2, mammalian target of rapapmycin complex 2; Rictor, rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR; mSin1, mammalian SAPK interacting protein 1; S6K1, p70S6 Kinase 1; 4EBP, eIF4E Binding Protein.

mTORC2, which is responsive to growth factor availability, is comprised of mTOR, mLST8 as well as rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor), which is needed for mTORC2 kinase activity [31, 32, 33]. mTORC2 also contain DEPTOR [30], mSin1 regulatory subunits [31] and Protor1/2, Rictor-binding components [34] (Fig. 1). mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes are stress sensors, regulating protein translation and energy supply [4]. mTORC1 regulates protein synthesis in response to nutrient depletion via p70S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) and eIF4E Binding Protein (4EBP) [35, 36], while mTORC2 is involved in cell metabolism, is sensitive to PI3K and phosphorylates Akt [4, 23] (Fig. 1).

With respect to autophagy, mTORC1 suppresses the autophagic machinery via the phosphorylation of multiple kinases necessary for autophagy initiation, specifically ULK1/2, ATG13 as well as FIP200 [4, 37]. Conversely, the low level of mTORC1 in response to nutrient deprivation activates these kinases via dephosphorylation and ultimately triggers autophagy. Of note, upon glucose deprivation, AXIN, a cytosolic protein involved in Wnt signaling [38], in complex with LKB1 [39], translocates to the lysosomal surface, activating the lysosomal pool of AMPK, inhibiting mTORC1 by phosphorylating TSC2 and RAPTOR. Importantly, AXIN translocation results in mTORC1 inhibition via facilitating mTORC1 dissociation from the lysosome, even in the absence of AMPK [40] (Fig. 1).

mTORC2 blocks autophagy indirectly via mTORC1 activation. The PI3K pathway activates mTORC2, which in turn activates Akt via phosphorylation. Akt, in turn, activates mTORC1 indirectly by phosphorylation and inactivation of TSC2, which suppresses the activity of the Rheb GTPase, an activator of mTORC1 [41, 42] (Fig. 1).

Another pathway for autophagy activation begins with AMPK, which is activated in response to energy depletion, further activating ULK1, and inhibiting Raptor via phosphorylation, leading to mTORC1 inactivation [4, 41, 42] (Fig. 1). The dysregulation of the mTOR signaling pathway often occurs in a variety of human malignant diseases, with tumor cells generally showing a higher susceptibility to mTOR inhibitors than normal cells [43].

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three mTOR inhibitors for the treatment of various malignancies and for suppression of transplant rejection in the clinical setting; these include rapamycin (sirolimus), everolimus, and temsirolimus [44]. These agents have shown clinical efficacy in various settings; however, as is the case with other chemotherapeutic agents [45], the development of drug resistance often constrains drug efficacy [46]. As inhibitors of mTOR pathways are potent autophagy inducers [47], it is of interest to investigate the nature of the autophagy induced together with its possible targeting or modulation. In this review, we attempt to provide a comprehensive overview of the relationship between the autophagic machinery and mTOR inhibitors in various tumor models, together with the results, where available, of relevant clinical trials, in an effort to develop a consensus as to whether autophagy targeting or modulation could represent an effective adjuvant strategy to increase mTOR efficacy.

Everolimus is the first oral inhibitor of mTOR that entered the clinical setting [48]. Everolimus showed broad clinical activity and was consequently approved by the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for treating advanced renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, in combination with exemestane in advanced hormone-receptor (HR)-positive, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma associated with tuberous sclerosis, and HER2-negative breast cancer [49]. Several studies investigated the relation between everolimus and autophagy in tumor models. Lui et al. [50] showed that one of the possible mechanisms for everolimus insensitivity in breast cancer is autophagy. Everolimus induced the autophagic machinery in MCF-7, MCF-7:5C and MCF-7:2A cells, as shown by increased LC3II levels and elevated autophagosome formation visualized by electron microscope. Interestingly, the pharmacologic autophagy inhibitor, Chloroquine (CQ), enhanced the anti-proliferative effect of everolimus in MCF-7 cell lines, suggesting a cytoprotective role of the autophagic flux induced by everolimus. However, studies utilizing both additional pharmacologic inhibitors coupled with genetic inhibition of autophagy would be required to more conclusively establish a cytoprotective role for autophagy in these experimental systems [51].

Rosich et al. [52] studied the contribution of autophagy in the development of resistance to everolimus in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Initially, the effect of everolimus was screened in a panel of 8 MCL cell lines and 11 MCL primary samples; everolimus was found to induce primarily a cytostatic effect with minimal apoptosis, as shown by flow cytometry and MTT proliferation assays, where UPN-1, GRANTA-519, JEKO-1, and REC-1 cell lines were more sensitive than Z-138, MAVER-1, JVM-2, and HBL-2 cells. Everolimus also induced a G0–G1 phase cell cycle arrest in the sensitive cells, REC-1 and GRANTA-519; on the other hand, the low sensitivity Z-138 cell line showed a slight increase in the S phase cellular fraction. Interestingly and in contrast to the limited cytotoxicity of everolimus in the cell lines, the majority of MCL primary samples demonstrated significant cytotoxicity in response to everolimus. Mechanistically, there was a dose-dependent decrease in the phosphorylation of Akt and mTOR, together with the downstream targets, S6RP and 4E-BP1, in both REC-1 and GRANTA-519 cell lines. However, somewhat surprisingly, these effects were not sustained; after prolonged drug exposure, rephosphorylation of Akt and mTOR was evident. Furthermore, in the low sensitive Z-138 cell line, a transient downregulation of p-S6RP and p-4E-BP1 proteins was detected, with no significant alteration in the levels of phospho-mTOR; a slight decrease in Akt phosphorylation was noted at the higher dose and time of exposure. However, everolimus efficiently reduced the phosphorylated mTOR, Akt, S6RP, and 4E-BP1, without compensatory Akt reactivation, in MCL primary samples. These data suggested a connection between the limited efficacy of everolimus and Akt phosphorylation, especially the rephosphorulation associated with the prolonged exposure. Rosich et al. [52] further investigated the impact of Akt inhibition, using Akti-1/2, in combination with everolimus, on the viability of REC-1, GRANTA-519, and Z-138 cell lines. Akti-1/2 alone did not affect cell viability, while the combination with everolimus was more effective in REC-1 and GRANTA-519 cell lines, with only a cytostatic effect observed in the low sensitivity Z-138 cell line. The combination showed a synergistic effect in all of the MCL primary samples. Mechanistically, the combination blocked Akt phosphorylation together with inhibiting the mTOR targets, p-S6RP and p-4E-BP in REC-1 and Z-138 cells. Apoptosis induction was detected only in the REC-1 cells but not in Z-138 cells.

In the course of investigating the molecular aspects associated with the low sensitivity to everolimus and Akti-1/2 in the resistant cells, autophagy was shown to be induced in response to the combination therapy in Z-138 and REC-1 cells. Autophagy was more pronounced in the low sensitivity Z-138 cells, as monitored by the conversion of LC3I to LC3II, and enhanced autophagolysosome formation. Critically, using ATG7/ATG5/ATG3 triple silencing via siRNA, autophagy inhibition sensitized the resistant cell line to the combination of everolimus and Akti-1/2 treatment. This sensitization was also observed, but to lesser extent, in REC-1 cells, suggesting that the resistance in Z-138 cells was likely mediated by autophagy induction and highlighting a cytoprotective role for the autophagic machinery. This putative cytoprotective role of autophagy was further confirmed using the pharmacological autophagy inhibitor, HCQ, where the triple combination of HCQ, everolimus and Akti-1/2 treatment significantly induced apoptosis in both Z-138 and REC-1 cells, with a greater sensitivity identified in the resistant Z-138 cells. Furthermore, the use of the triple therapy showed a synergistic effect in all MCL primary cases, with elevated cell death only evident in those cases with poor response to everolimus combined with Akti-1/2. These studies suggested that autophagy may interefere with drug-induced cell death and consequently could be involved in the development of resistance to the combination of everolimus and Akti-1/2.

Zeng et al. [53] reported that everolimus induced autophagy in 786-O and A498 renal cell carcinoma cell lines in a dose-dependent manner, as evidenced by elevated LC3-II/I and p62/SQSTM1 degradation. Subsequently, CQ addition significantly enhanced everolimus-induced cytotoxicity, as shown by an MTT assay together with enhanced apoptosis induction compared to everolimus alone, suggesting a cytoprotective role for the everolimus induced autophagy. Mechanistically, everolimus treatment upregulated p-ERK expression in both cell lines. The further combination of AZD6244, an ERK signaling inhibitor [54], with everolimus, induced a more pronounced cell killing than each drug alone, together with suppression of everolimus-induced autophagy, suggesting that ERK signaling inhibition suppressed the cytoprotective autophagy induced by everolimus.

Grimaldi et al. [55] also studied the effect of autophagy inhibition in combination with everolimus in renal cancer. The combination of CQ and everolimus showed anti-proliferative activity in A498, RXF393, SN12C and 769P renal cancer cell lines using an MTT assay. Interestingly, the drug combination induced apoptosis in A498, and RXF393 cell lines, as shown by annexin V/PtdIns followed by FACS analysis, as compared to each drug alone. Furthermore, the observed increase in MDC staining intensity in response to the combination therapy as compared to each drug alone may reflect late autophagy inhibition and autophagosome accumulation caused by CQ.

Pattingre and Levine [56] has shown that the anti-apoptotic protein,

Bcl

The Tai et al. [57, 58] group investigated the combinations of arsenic trioxide or propachlor [59] with everolimus in prostate cancer. The combination of arsenic trioxide with everolimus [57] inhibited colony formation for LNCaP and PC3 cells as compared to each drug alone. Furthermore, the combination synergistically inhibited both cell lines as showed by a cell luminescence assay together with the promotion of apoptosis (by annexin V/flow cytometry, upregulation of cleaved PARP, as well as cleaved caspase 3). Interestingly, the combination of arsenic trioxide and everolimus induced the autophagic machinery, as shown by the enhanced conversion of LC3I to LC3II as compared to each drug alone. Autophagy induction was further confirmed by the elevated autophagosomes formation observed by electron microscopy as well as via a GFP-LC3 assay, suggesting that the two agents synergistically increased the extent of the autophagic flux, which played a cytotoxic role in this model. Importantly, they showed that the combination increased protein/mRNA expression levels of Beclin 1, while upon Beclin 1 depletion using siRNA, the extent of the apoptosis induced in response to the combination was reduced, further highlighting the cytotoxic role of the induced autophagic machinery. These results were further validated in vivo using LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts, where the combination significantly suppressed the proliferation of the tumor xenografts as compared to each drug alone. Additionally, the levels of Beclin 1 and LC3II were elevated. These results suggested that arsenic trioxide in combination with everolimus induced a cytotoxic form of autophagy in prostate cancer. Similarly, Liu et al. [60] reported that this combination induced a cytotoxic form of autophagy in ovarian cancer in vitro using SKOV3 and OV2008 cell lines, and in vivo using SCID mice inoculated with SKOV3 cells.

The combination of propachlor [59], a compound that was chosen after a high

throughput screen of 5000 widely used small molecules that could possibly

synergize with everolimus, and everolimus [58] synergistically reduced the

numbers of PC3 and C4-2 cells and promoted apoptosis (annexin V and 7-AAD/flow

cytometry, upregulation of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3 as well as reduced

Bcl

In contrast to the above findings, Chen et al. [61] showed that

autophagy induction may contribute to everolimus resistance in prostate cancer.

Specifically, the combination of everolimus together with CQ significantly

reduced the viability of PC3 and LNPER cells compared to each drug alone.

Furthermore, apoptosis induction was evident based on the upregulation of

Bax, cleaved PARP, and reduced levels of Bcl

The variability in autophagy forms reported by Tai et al. [57, 58], Liu et al. [60] and Chen et al. [61] may be attributed to the nature of the compounds under study as well as the tumor cell lines. Tai et al. [57, 58], and Liu et al. [60] utilized a combination of everolimus together with either arsenic trioxide or propachlor, where the nature of the autophagy-induced by the combination was investigated in different tumor models (rather than each drug alone), which may modulate the nature of the autophagy induced from a cytoprotective form into a cytotoxic form, a phenomenon known as the autophagic switch [62]. In contrast, Chen et al. [61] focused mainly on the cytoprotective autophagy induced by everolimus in prostate cancer, which was consistent with the other studies [50, 52, 53, 55] investigating the nature of the autophagy triggered by everolimus.

Haas et al. [63] investigated the clinical outcomes of inhibiting autophagy induced by everolimus by performing a phase I/II trial for 10 mg daily everolimus in combination with 600 mg twice daily HCQ in patients with previously treated/advanced renal cell carcinoma. The utilized regimen was tolerable. Out of 33 patients, 22 patients (67%) showed disease control with partial response evidenced in 2 patients (6%). Furthermore, progression-free survival of greater than 6 months was achieved in 15 patients (45%), who showed disease control.

Collectively, these pre-clinical and clinical results tend to support the utilization of autophagy inhibitors as adjuvant therapy to overcome the cytoprotective autophagy induced by everolimus, and ultimately increasing its effectiveness.

Temsirolimus is a prodrug for sirolimus [64], which selectively inhibits mTOR signaling, preventing the progression of cells from the G1 to S phase of the cell cycle and suppressing the overexpression of angiogenic growth factors [65]. Temsirolimus has shown substantial activity in pre-clinical studies, which led to its approval in 2007 by FDA for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma [64]. As described in detail below, autophagy induced by temsirolimus in various tumor models has generally appeared to play largely a cytoprotective role.

As an inhibitor of mTOR signaling, temsirolimus is a potent inducer of autophagy, as shown, for example, by the studies of Pinto-Leite et al. [66] in urinary bladder cancer using 5637, T24, and HT1376 cell lines [66]. Temsirolimus inhibited the growth of the three cell lines in dose-dependent manner, but with minimal induction of apoptosis. Autophagosome accumulation was evident in the three cell lines upon temsirolimus treatment, suggestive of active autophagic flux. Consistent with the findings of Pinto-Leite et al. [66], Liu et al. [67] showed that temsirolimus induced autophagy in the adenoid cystic carcinoma ACC-M cell line. Autophagy was detected based on autophagosome formation by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and increased Beclin 1, LC3I and LC3II levels. The induction of autophagy was accompanied by a reduction in cellular proliferation. Autophagy induction was confirmed in vivo, where temsirolimus inhibited the growth of tumor xenografts, together with increased LC3 and Beclin 1 expression. However, while the studies by both Pinto-Leite et al. [66] and Liu et al. [67] establish the ability of temsirolimus to induce autophagy, the nature of the autophagy and its contribution to drug effects was not defined utilizing either pharmacological or genetic inhibition experimental strategies [51].

Kaneko et al. [35] studied the efficacy of temsirolimus in colorectal

cancer in vivo and in vitro. Temsirolimus reduced the

proliferation of CaR-1 and Colon26 cells, in which Akt is highly activated [68],

in a dose-dependent manner together with G0/G1 phase growth arrest, while no

inhibitory effect was observed in HT-29 cells, where Akt was weakly activated

[68]. Temsirolimus did not induce apoptosis in any of the three cell lines.

Mechanistically, they showed that temsirolimus reduced the expression of p-p70S6K

and p-4E-BP1, the downstream targets of mTOR in all the cell lines. Furthermore,

they showed that temsirolimus slightly reduced p-AKT or p-mTOR in CaR-1 and

Colon26 cells, while their expression levels increased in HT-29 cells. Based on

these results, Kaneko et al. [35] suggested that a relatively increased

p-AKT level canceled the inhibitory effect of temsirolimus on p-mTOR in the HT-29

cell line with unactivated Akt when untreated. Temsirolimus also reduced the

levels of cyclin D1 in CaR-1 and Colon26 cells, with no effect observed in HT-29

cells. Interestingly, they investigated the effect of temsirolimus on p-mTOR,

VEGF and HIF-1

Kaneko et al. [35] investigated the nature of the autophagy by combining the autophagy inhibitor, CQ, with temsirolimus in Colon26 cells. Temsirolimus induced the autophagic machinery in Colon26 cells as shown by increased levels of LC3II coupled with p62/SQSM1 degradation. The combination of CQ with temsirolimus reduced the proliferation of Colon26 cells to a greater extent than each drug alone, together with increasing the extent of apoptosis, indicative of a cytoprotective role of temsirolimus-induced autophagy. These results were further confirmed in vivo using Balb/c mice bearing a subcutaneous allografted tumor, where the autophagy induction by temsirolimus was confirmed by increased LC3II and p62/SQSM1 degradation. The combination with CQ resulted in a significantly greater anti-tumor effect than each drug alone together with apoptosis induction, confirming the cytoprotective role of temsirolimus-induced autophagy. Interestingly, the combination did not show a greater anti-angiogenic activity as compared to temsirolimus alone.

Shiratori et al. [69] investigated the possible utilization of temsirolimus in combination with CQ to increase radio-sensitivity in colorectal cancer using SW480 and HT-29 cells. Initially, they showed that ionizing radiation (IR) induced autophagy, based on the conversion of LC3I to LC3II, and p62/SQSM1 degradation, as well as via increasing autophagosome formation using acridine orange staining in both cell lines [69]. Furthermore, IR activated the mTOR pathway as evidenced by the elevated phosphorylation of mTOR pathway-related proteins, S6 ribosomal protein and 4E-BP1. Interestingly, neither temsirolimus nor CQ alone affected the IR-suppressive effect, as shown by a clonogenic survival assay; however, the combination of temsirolimus and CQ enhanced radio-sensitivity at 2, 4 and 6 Gy in SW480 cells and at 4 and 6 Gy in HT-29 cells. Temsirolimus or CQ reduced the proliferation of irradiated cells, whereas the combination of temsirolimus and CQ showed a greater reduction in the proliferation of irradiated cell lines. Furthermore, the triple combination therapy only modestly increased the apoptotic population as showed by annexin V-FITC and PI assay [69]. These results suggest that autophagy inhibition leads to growth suppression without significant apoptosis induction, highlighting the cytostatic role of the autophagic machinery.

Mechanistically, temsirolimus suppressed the IR-mediated elevation in the levels of S6 ribosomal protein and 4E-BP1, which were not affected by CQ, suggesting that CQ does not directly influence mTOR signaling. Furthermore, temsirolimus alone induced autophagy as confirmed by decreased p62/SQSTM1 levels and am increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio [69]. Importantly, upon combining temsirolimus with IR, p62/SQSTM1 degradation was enhanced, suggesting autophagy induction, and suppression upon CQ addition. LC3I conversion to LC3II was increased with IR and temsirolimus, and further increased upon adding CQ to the combination. Furthermore, the number of autophagosomes increased with IR and temsirolimus as shown by acridine orange staining, which further increased upon adding CQ. These results indicate that IR induced autophagy in SW480 and HT-29 cells, which was further increased upon mTOR inhibition using temsirolimus, and that autophagic flux was suppressed with CQ addition [69]. In this system, the role of the autophagic flux seems to be cytostatic; however, investigating the role of autophagy is needed in this system using the genetic knockdown approach to clearly define the autophagic role.

Inamura et al. [70] studied the possible utility of combining temsirolimus with docetaxel in prostate cancer cells. As would be expected, each treatment alone inhibited the growth of both PC3 and LNCaP cells in a dose-dependent manner, while the combination produced a more effective response than each drug alone. Regarding apoptosis, docetaxel alone induced cleaved caspase 3 accumulation in PC3 cells; however, temsirolimus did not change cleaved caspase 3 levels. Interestingly, the combination of temsirolimus together with docetaxel showed an enhanced accumulation of cleaved caspase 3 as compared to each drug alone. These results were further validated in vivo using prostate cancer xenograft mouse models, where the combination therapy showed a greater anti-tumor activity than each drug alone. Mechanistically, temsirolimus induced autophagy as shown by elevated LC3II levels, whereas docetaxel did not affect the LC3 levels. The autophagy induction by temsirolimus was further confirmed by p62 degradation. Interestingly, temsirolimus-induced growth suppressive effects were enhanced by combination with the autophagy inhibitors, CQ or 3-MA in the PC3 cell line. Furthermore, the autophagy induced by temsirolimus was suppressed upon combination with docetaxel, as shown by decreased LC3II/I ratio, as well as p62/SQSTM1 accumulation, indicating that docetxel suppressed temsirolimus induced autophagy. Inamura et al. [70] also investigated whether the combination of temsirolimus and docetaxel blocked autophagosome membrane formation, through validating the combination effect on phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase (PI3K) class III complex. Temsirolimus alone induced PI3K phosphorylation in the PC3 cell line, which was decreased upon combination with docetaxel, suggesting that docetaxel blocked the autophagosome membrane formation induced by temsirolimus. They also showed that the combination therapy did not affect the temsirolimus induced-reduction in mTOR and p-Akt expression levels, suggesting that docetaxel did not affect the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. These results may be a reflective of cytoprotective form of autophagy induced by temsirolimus in prostate cancer cells, which was blocked by docetaxel via the inhibition of PI3K class III. However, the effect of combining the autophagy inhibitors CQ and 3-MA with temsirolimus requires confirmation through the utilization of genetic inhibition of the autophagic machinery.

Chow et al. [71] investigated the combination of temsirolimus together with THZ1, a cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (CDK7) inhibitor [72], in renal cell carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. THZ1 in combination with temsirolimus synergistically reduced the viability of 786-O and Caki-2 cell lines as compared to temsirolimus alone. Furthermore, the combination of temsirolimus with THZ1 promoted an increase in cleaved PARP accumulation. Temsirolimus alone induced autophagic flux in both cell lines as shown by an increased LC3II/I ratio, ATG12 and ATG5, while THZ1 alone did not significantly alter their levels; however, the combination produced a marked reduction in the levels of these markers as shown by immunoblotting. Consequently, Chow et al. [71] suggested that THZ1 suppressed the cytoprotective autophagy-induced by temsirolimus, resulting in cytotoxic activity. Of note, p62/SQSM1 results presented by Chow et al. [71] were inconsistent with the LC3II/I ratio, and ATG12 and ATG5 data, where THZ1 addition to temsirolimus resulted in a further reduction in p62/SQSTM1 levels in 786-O cells, while in the Caki-2 cell line, temsirolimus resulted in p62/SQSM1 accumulation, that was reduced upon THZ1 addition, highlighting the need for investigating the p62/SQSM1 expression levels in this system. When the efficacy of the combination was investigated in vivo using athymic nu/nu mice injected with renal cell carcinoma xenografts, the combination therapy moderately enhanced anti-tumor activity over and above that of each drug alone, together with no obvious toxicity. These results further support the cytoprotective role of autophagy induced by temsirolimus.

Rangwala et al. [73] performed a phase I clinical trial for 27 patients with advanced solid tumors and 12 with metastatic melanoma, where the combination of temsirolimus and HCQ was investigated. The combination of HCQ and temsirolimus was well tolerated with signs of mild toxicity including, anorexia, fatigue, and nausea. Importantly, 14/21 (67%) patients with solid tumors and 14/19 (74%) patients with melanoma achieved stable disease. Furthermore, they reported that the combination produced metabolic stress on tumors as shown by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) measurements, together with pharmacodynamic evidence for autophagy inhibition in serial peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples and tumor biopsies, suggesting that the combination of HCQ and temsirolimus was safe, tolerable, inhibited autophagy in patients, as well as demonstrating significant antitumor activity.

These results tip the scale towards a cytoprotective role of autophagy induced by temsirolimus, with clinical evidence from Rangwala et al. [73] supporting the possible targeting of autophagy to increase the effectiveness of temsirolimus as adjuvant therapy.

Rapamycin or sirolimus is a potent immunosuppressive drug, which is approved for suppressing organ rejection in kidney transplant patients as well in the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis [74]. The relationship between autophagy and rapamycin has been studied extensively in various tumor models. For instance, Dai et al. [75] investigated the efficacy of rapamycin in pancreatic cancer using PC-2 cells. Rapamycin was shown to inhibit PC2 cell proliferation in a dose and time-dependent manner. Rapamycin also induced apoptosis based on multiple apoptotic markers including chromatic agglutination, fragmentation of nuclei, chondriosome swelling, as well as apoptotic body formation [75]. Dose-dependent apoptosis was further confirmed by increased Bax levels (an indirect indicator) as well as by annexin V-FITC/PI staining together with flow cytometry. Dose-dependent induction of autophagy was shown by autophagosome formation (visualized by TEM), an increase in MDC-labeled autophagic vacuoles, and increased Beclin 1 mRNA levels [75]. Although these results would be considered to be consistent with a cytotoxic role of the autophagy induced by rapamycin in the pancreatic cancer model, such a conclusion would be premature in the absence of studies involving the pharmacological and genetic suppression of autophagy to determine the impact on drug sensitivity [51].

Lin et al. [76] studied the effect of rapamycin in another model, specifically neuroblastoma, using the SK-N-SH and SH-SY5Y cell lines. Here again, rapamycin inhibited the proliferation of both cell lines in dose and time-dependent manner, together with G0/G1 cell cycle growth arrest. The induction of the autophagic machinery was shown in SK-N-SH and SH-SY5Y cell lines based on autophagosome formation, increased Beclin 1 and LC3II/I levels, as well as p62/SQSM1 degradation. These outcomes were accompanied by a reduction in mTOR and p-mTOR levels; however, as with the studies noted above in pancreatic cancer, the fact that autophagy was induced does not provide any indication as to how the autophagy is functioning in this experimental model system.

Rezazadeh et al. [77] studied rapamycin under normoxic and hypoxic

conditions in the long-established Hela cervical cancer cell line. Rapamycin

moderately affected the viability of HeLa cells under normoxic condition, while a

slightly more pronounced effect was evident under hypoxic condition. The

induction of apoptosis by rapamycin was more pronounced under hypoxic condition,

as indicated by a number of fundamental apoptotic characteristics including cell

blebbing, chromatin condensation, as well as an increased Bax/Bcl

In the M14 melanoma cell line, Li et al. [78] showed that rapamycin

inhibited proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. The antiproliferative drug

effect was accompanied by apoptosis induction, as evidenced by increased

Bax and reduced Bcl

In oral cancer, Semlali et al. [79] investigated rapamycin activity using the human gingival epithelial carcinoma Ca9-22 cell line. Initially, they showed that rapamycin treatment inhibited the proliferation of Ca9-22 cells and colony forming ability as well as promoting cell death (shown by an LDH release assay) in dose-dependent manner. These outcomes were accompanied by the promotion of apoptosis, as confirmed by annexin/PI followed by flow cytometry together with increased cleaved caspase 3 and 9 levels. Autophagy induction in Ca9-22 cells upon rapamycin treatment was demonstrable based on increased LC3II/I levels, and increased autophagic intensity detected by flow cytometry; however, an assessment of p62/SQSTM1 levels was somewhat inconsistent with the other findings in that accumulation of this protein was more suggestive of autophagy inhibition. These cytotoxic functions of the autophagy induced by rapamycin in Ca9-22 cells was more firmly established in experiments where autophagy was inhibited pharmacologically utilizing 3-methyl adenine (3-MA), where the 3-MA suppressed the cytotoxicity promoted by rapamycin.

Li et al. [80] studied the possible utilization of rapamycin to

sensitize A549 lung carcinoma cells to radiation. Initially, they showed that

rapamycin inhibits the proliferation of A549 cells in a dose and time-dependent

manner. Either rapamycin or radiation exposure (4 Gy) alone was able to promote

autophagy, as reflected by increased autophagosome formation visualized by

electron microscope. As would be expected, the number of the autophagosomes

increased upon combining radiation with rapamycin. The induction of autophagy by

either treatment was further confirmed by an increased LC3III ratio as well as

p62/SQSTM1 degradation. Treatment with either rapamycin or radiation resulted in

a modest reduction in colony formation, which was significantly enhanced by the

combination treatment, raising the possibility that sensitization of the tumor

cells to radiation was reflecting a possible cytotoxic action of the

rapamycin induced autophagy. Rapamycin was found to sustain elevated levels of

Ishibashi et al. [83] investigated the possibility that inhibition of the autophagy induced by rapamycin could serve to increase its efficacy in MG63 osteosarcoma cells. These investigators showed that CQ enhanced the anti-proliferative effect of rapamycin. Importantly, they showed that rapamycin increased the levels of LC3II, and the Atg12-Atg5 complex together with p62/SQSM1 degradation, reflecting an active autophagic flux. Conversely, the combination of CQ and rapamycin generated the apoptotic markers cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-9, and cleaved PARP. This apoptosis upon inhibition of the rapamycin induced autophagy was further confirmed using annexin V-FITC/PI staining followed by flow cytometry, suggesting a cytoprotective role of the autophagy induced by rapamycin in osteosarcoma, which contrasts markedly with the findings indicated above in Rezazadeh et al. [77], Semlali et al. [79], and Li et al. [80].

Recently, Masaki et al. [84] investigated the potential targeting of autophagy in liposarcoma using the 93T449 cell line. Initially, they showed that the combination of rapamycin with CQ significantly inhibited the cell viability as compared to each drug alone. Autophagy inhibition (accumulation of autophagosomes indicating that autophagy was not proceeding to completion) under the conditions of combining rapamycin with CQ was demonstrated by LC3II accumulation by immunocytochemical staining. The combinations resulted in increased apoptosis, as assessed by the TUNEL assay. The reduced cell viability and promotion of apoptosis in the 93T449 cell line upon incorporation of a pharmacological autophagy inhibitor would suggest that autophagy was cytoprotective; however, the authors neglected to clearly demonstrate whether rapamycin by itself induced the autophagic machinery in this cell line. Furthermore, additional autophagy markers, including assessment of p62/SQSM1 degradation, together with genetic inhibition of the autophagic process would be necessary to confirm the cytoprotective autophagy in these cells.

The same research group [85] also tested rapamycin in combination with CQ in vivo using patient-derived orthotopic xenograft mice models of dedifferentiated liposarcoma. The combination showed a marked tumor growth arrest as compared to each drug alone, together with increased apoptosis induced as showed by the TUNEL assay, more firmly arguing for a cytoprotective role for the autophagic process. Two primary limitations of this work are that the authors did not study any autophagic markers in vivo and that chloroquine may have effects that are not related directly to autophagy inhibition.

Clinically, several clinical trials have been performed in lymphangioleiomyomatosis that appear to support autophagy targeting [86, 87]. For example, El-Chemaly et al. [86] performed a phase I clinical trial, where the combination of HCQ and rapamycin was tolerable with no significant toxicity.

mTOR inhibitors have demonstrated clinical efficacy in various malignancies in the clinical setting; however, resistance development, as is frequently the case with other chemotherapeutic modalities, hinders their efficacy [46]. One of the molecular mechanisms that may contribute to resistance development is autophagy [8, 88]. Autophagy is a survival mechanism, with four roles having been identified in various cancer models; however, the cytotoxic and cytoprotective functions are the ones most frequently considered in the scientific literature [12]. Many clinical trials are in progress, investigating the potential utilization of autophagy inhibition as adjuvant therapy to improve the clinical utility of anti-neoplastic agents, and presumptively to overcome drug resistance [7, 89]. It is important to note that the nature of the role played by the autophagic machinery is dependent on both the chemical nature and the cell lines being utilized [3]. As summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [35, 50, 52, 53, 55, 57, 58, 60, 61, 63, 66, 67, 69, 70, 71, 73, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87]), the roles of autophagy induced by rapamycin, temsirolimus as well as everolimus have not been shown to be consistent in preclinical studies. The primary role of the autophagic flux induced in response to everolimus is cytoprotective with a clinical trial performed by Haas et al. [63] supporting the clinical utility of the autophagy inhibitor, HCQ, to improve everolimus clinical outcomes. The combination of everolimus with either arsenic trioxide or propachlor [58, 60] generated a cytotoxic form of autophagy, which may be attributed to the autophagic switch [62]. Temsirolimus induced primarily the cytoprotective form of autophagy, with clinical data supporting the utilization of HCQ in combination with temsirolimus [73]. In the case of rapamycin, both cytoprotective and cytotoxic functions were identified, depending on the experimental model(s), although the literature generally leans towards the cytotoxic form. Another recent mTOR inhibitor, ridaforolimus, is being investigated in many clinical trials, including endometrial carcinoma [90] and sarcoma (NCT00538239); however, information as to its relationship with the autophagic machinery in preclinical studies is quite limited, at least to our knowledge.

| mTOR inhibitor | Cancer/Cell line | Autophagy induced or suppressed | Autophagy role | References |

| Everolimus | MCF-7, MCF-7:5C and MCF-7:2A breast cancer cells | Induced | Cytoprotective | [50] |

| Everolimus and Akti-1/2 | A panel of 8 mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) cell lines; UPN-1, GRANTA-519, JEKO-1, REC-1, Z-138, MAVER-1, JVM-2, and HBL-2 cell lines and 11 MCL primary samples | Induced | Cytoprotective | [52] |

| Everolimus | 786-O and A498 renal cell carcinoma cell lines | Induced | Cytoprotective | [53] |

| Everolimus + CQ | A498, RXF393, SN12C and 769P renal cancer cell lines | Cytoprotective | [55] | |

| Arsenic trioxide + Everolimus | LNCaP and PC3 cells, LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts | Induced | Cytotoxic | [57] |

| Arsenic trioxide + Everolimus | SKOV3 and OV2008 ovarian cancer cell lines and SCID mice inoculated with SKOV3 cells | Induced | Cytotoxic | [60] |

| Propachlor + Everolimus | PC3 and C4-2 prostate cancer cells, and SCID mice subcutaneously injected with PC3 cells | Induced | Cytotoxic | [58] |

| Everolimus + CQ | PC3 and LNPER prostate cancer cells | Cytoprotective | [61] | |

| Everolimus + HCQ | Patients with previously treated/advanced renal cell carcinoma (clinical trial) | [63] | ||

| Temsirolimus | 5637, T24, and HT1376 urinary bladder cancer cell lines | Induced | [66] | |

| Temsirolimus | Adenoid cystic carcinoma ACC-M cell line | Induced | [67] | |

| Temsirolimus | CaR-1 and Colon26 cells, HT-29 cells and Balb/c mice bearing a subcutaneous allografted tumor | Induced | Cytoprotective | [35] |

| Temsirolimus + radiation +CQ | SW480 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells | Induced | Cytostatic | [69] |

| Temsirolimus | PC3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cells and prostate cancer xenograft mouse models | Induced | Cytoprotective | [70] |

| Temsirolimus + THZ1 | 786-O and Caki-2 renal cell carcinoma cell lines and athymic nu/nu mice injected with renal cell carcinoma xenografts | Induced | Cytoprotective | [71] |

| HCQ + Temsirolimus | 27 patients with advanced solid tumors and 12 with metastatic melanoma (clinical trial) | [73] | ||

| Rapamycin | PC-2 pancreatic cancer cells | Induced | Cytotoxic | [75] |

| Rapamycin | SK-N-SH and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines | Induced | [76] | |

| Rapamycin | HeLa cervical cancer cell line | Induced | Cytotoxic | [77] |

| Rapamycin | M14 melanoma cell line | Induced | Cytotoxic | [78] |

| Rapamycin | human gingival epithelial carcinoma Ca9-22 cell line | Induced | Cytotoxic | [79] |

| Radiation + Rapamycin | A549 lung carcinoma cells | Induced | Cytotoxic | [80] |

| Rapamycin | MG63 osteosarcoma cells | Induced | Cytoprotective | [83] |

| Rapamycin + CQ | 93T449 liposarcoma cell line | Cytoprotective | [84] | |

| Rapamycin + CQ | Patient-derived orthotopic xenograft mice models of dedifferentiated liposarcoma | Cytoprotective | [85] | |

| Rapamycin + HCQ | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (clinical trial) | [86] | ||

| Rapamycin + HCQ | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (clinical trial) | [87] |

HCQ, hydroxycholoroquine; CQ, choloroquine.

Many of the studies mentioned in this review lack experiments involving the pharmacological and genetic inhibition of the autophagy induced by mTOR inhibitors [51]. Furthermore, it is difficult to understand why drugs that ostensibly target the same biochemical and molecular pathways should induce different functional forms of autophagy. Given these limitations, and despite some promising clinical studies, the preclinical work does not provide sufficient confidence that autophagy inhibition would prove to be a consistent and useful strategy to improve the clinical efficacy of mTOR inhibitors. Additionally, the side effects associated with mTOR inhbitor utilization, including stomatitis, lymphocele, poor wound healing, diarrhea, cytopenias, hypertension, rash, and interstitial lung disease [91], are a major concern that need to be minimized; recent strategies emerging to improve mTOR inhbitor side effect profiles are discussed in the Kaplan et al. [92] review.

All authors contributed to the conception or design of the work. AME, and AAE wrote the original draft and DAG edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Rresearch in the Gewirtz laboratory is supported by grants # CA268819 and CA239706 from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Given David A. Gewirtz’s role as Guest Editor for the journal, he had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Kavindra Kumar Kesari.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.