1. Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a complex membrane system that serves as an

essential site for the synthesis, folding, and posttranslational modification of

secreted and membrane proteins [1]. Imbalance in ER caused by certain

physiological or pathological factors leads to the accumulation of a large number

of unfolded or misfolded proteins in cells, resulting in ER stress [2]. To

restore ER homeostasis and reduce the amount of faulty or unfolded proteins in

the reticulum, the unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated [3]. The UPR is

regulated by three proteins, including activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6),

protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK) and inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1)

[4]. These three ER transmembrane proteins reversibly bind to the endoplasmic

reticulum partner binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP)/heat shock protein family

A member 5 (HSPA5)/glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) to inhibit activity under

normal physiological conditions; however, HSPA5 dissociates from this protein

when the UPR occurs. These three proteins are activated and initiate a response,

thus regulating transcription and translation, activating protein degradation

pathways and reducing the accumulation of faulty proteins in the ER to restore ER

homeostasis [5]. More intense endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) occurs when the

three sensors of the UPR are insufficient to restore unfolded proteins in the ER

to a normal state [6].

As a new mode of death, ferroptosis differs from other programmed types of

death, such as apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy, and its occurrence depends on

the accumulation of iron in cells. Its biochemical, morphological and genetic

characteristics are significantly different from those of other types of

programmed cell death [7, 8]. Morphology is mainly manifested by mitochondrial

agglutination or swelling, increased membrane density, a reduced or disappeared

ridge and outer membrane rupture [9]. When glutathione (GSH) is exhausted in the

cell, the activity of GPX4 is reduced, the GPX4 catalytic reduction reaction

cannot metabolize lipid peroxides and a large amount of reactive oxygen species

(ROS) are generated to induce ferroptosis [10]. Intracellular iron accumulation,

lipid peroxidation and an abnormal antioxidant System Xc- are the key factors

involved in ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is induced by ROS, which are produced by

various sources, such as iron metabolism, the mitochondrial electron transport

chain and the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX)

protein family.

An increasing number of studies have shown that ferroptosis and ERS are mutually

regulated and that ferroptosis and ERS are involved in the occurrence of various

liver diseases. In this review, the authors summarize the mechanisms by which ERS

interacts with ferroptosis and the roles of these mechanisms in common liver

diseases.

2. Mechanism of ERS

2.1 PERK Pathway

PERK is a kinase of phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2

(eIF2) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2). When ERS

occurs, PERKs separate from HSPA5s and are activated. Activated PERK

phosphorylates eIF2 and Nrf2. The activation of eIF2 can

cause most protein translation to decrease, and the protein load in the

endoplasmic reticulum is also reduced [1]. The expression of activating

transcription factor 4 (ATF4) is upregulated when the level of phosphorylated

eIF2 reaches a certain level [11]. ATF4 is a major regulator of the

stress response and regulates the expression of genes involved in amino acid

metabolism and redox and protein homeostasis at the transcriptional level. ATF4

enhances mitochondrial respiration and promotes oxidative metabolism by

activating the comprehensive stress-promoting respiratory supercomplex [12]. The

activation of Nrf2 can promote the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), ATF3

activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) and solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11), which are other target groups, as well as upregulate ROS and induce

ERS [13].

2.2 The IRE1 Pathway

IRE1 is a type I transmembrane protein that recognizes unfolded

proteins and misfolded proteins in the ER via its N-terminal peptide-binding

domain. IRE1 and GRP78 bind to the downstream X-box-binding protein 1

(XBP1) mRNA transcript after it is bound to a misfolded protein. Spliced X-box

binding protein 1 (XBP1s) is a transcription factor responsible for regulating

the transcription of genes associated with the ER quality control and ERAD

pathways. In addition, regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD), which

degrades or translates mRNA, reduces the protein load in the ER and restores ER

homeostasis [14, 15, 16].

2.3 The ATF6 Pathway

ATF6 is a type II transmembrane protein with two subtypes known as

ATF6 and ATF6. ATF6 is separated from GRP78 and

disrupted by the site-1protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P) when ERS occurs.

The amino-terminal cytoplasmic fragment (ATF6f) is released and translocated to

the nucleus to participate in the expression of proteins, thereby increasing the

folding ability of the ER and restoring ER homeostasis [17, 18]. XBP1 is a target

molecule regulated by ATF6. ATF6 can also upregulate the transcription of XBP1

mRNA, increase the level of XBP1s and activate ERS [19, 20].

3. Mechanism of Ferroptosis

3.1 Iron Accumulation

Iron is an important trace metal in the body and is involved in biosynthesis,

oxygen transport and the respiratory chain. Cellular iron production is mediated

by transferrin (Tf) and transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1). Intracellular iron can be

transported outside of the cell by the ferroportin (FPN) [21]. Iron overload is

an important cause of ferroptosis. When a large amount of Fe accumulates

in the cell, it induces the Fenton reaction, results in the production of a large

number of ROS, hydroxyl groups and free radicals and activates iron-containing

enzymes. Many known organic compounds, such as carboxylic acids, alcohols and

esters, can be peroxidized by the Fenton reaction and produce corresponding

peroxide products, which ultimately lead to ferroptosis [22, 23, 24].

The iron uptake pathway mediated by Tf and TfR1 is involved in ferroptosis. The

inhibition of the expression of TfR1 can effectively reduce the ferroptosis

induced by erastin. The addition of fe-containing Tf or ferric ammonium citrate

to the cell medium resulted in an increase in the Fe concentration and

induced ferroptosis [25, 26]. Nedd4-like E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (NEDD4L) can

increase the degradation of lactotransferrin (LTF), inhibit intracellular iron

accumulation and reduce ferroptosis [27]. The initial signal of ferroptosis has

not yet been determined; however, ferroptosis must be involved, and the degree of

iron accumulation in the cell directly determines the course of ferroptosis.

3.2 Lipid Peroxidation

The initiation and execution of ferroptosis are regulated by lipids.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are essential substrates for fat metabolism

and are catalyzed by coenzyme A (CoA) and 4acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family

member 4 (Acsl4) to produce polyunsaturated fatty acid membrane phospholipids

(PUFA-PLs) [28]. PUFA-Pls is catalyzed by lipoxygenase (LOX) or cytochrome P450

oxidoreductase (POR) to produce lipid peroxides (LPOs) [8]. LPO can activate

protein kinase II (PKCII) to promote ACSL4 activation and

oxidize additional PUFAs to produce additional LPO [29]. LPO can produce lipids

to freely form lipid ROS through lipid oxidation reactions [30]. Furthermore,

malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) levels are biomarkers of

ferroptosis [31].

3.3 Antioxidant System Xc- Abnormalities

The oxidation and antioxidant reactions in the cell are in balance under

physiological conditions. When the redox balance system is disrupted, this

scenario causes the accumulation of free radicals and triggers ferroptosis.

System Xc- is a glutamate/cystine reverse transporter. Cystine, glutamate and

glycine are catalyzed by glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione synthase

(GS) to become glutathione (GSH). GSH is an important intracellular antioxidant

that can alleviate oxidative stress by scavenging free radicals in the body [32].

Additionally, GPX4 is a ferroptosis inhibitor that uses GSH as a coenzyme, which

can reduce LPO to nontoxic lipid alcohols and reduce ROS and free radical

accumulation [33]. Ferroptosis can be induced by reduced activity or insufficient

levels of GPX4 [34].

4. The Interaction between Ferroptosis and ERS

4.1 Ferroptosis-Inducing ERS

Ferroptosis and ERS play important roles in cell death. In recent years, studies

have shown that ferroptosis can be accompanied by ERS, which may be closely

related to ROS produced during ferroptosis. ROS can interfere with the activity

of protein folding enzymes, thus resulting in ER protein peroxidation,

dysfunction of ER molecular chaperones and the accumulation of unfolded proteins

in the ER. Eventually, ERS is induced. Additionally, ROS binds to the inositol

receptor 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3R) in the ER, resulting in high intracellular

Ca accumulation and ultimately ERS [35, 36]. Furthermore, organic extracts

of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can produce a large amount of ROS by binding

to the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and significantly increase the

expression level of CHOP. CHOP can simultaneously activate the three receptors of

ERS, PERK, IRE1, and ATF6, thereby inducing strong ERS [37]. Iron is also

involved in the occurrence of ERS, and iron activates the

PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP pathway, thereby inducing p53 to upregulate the

expression of apoptosis regulator (PUMA). Ferroptosis inducers that induce

ferroptosis in cells also activate ERS. Ferroptosis inducers can inhibit

cystine-glutamate exchange in cells, increase the expression of ERS-related

protein ChaC glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1), and

activate ERS. CHAC1 is involved in the ATF4-CHOP pathway in ERS [38]. Artesunate

can be used as an inducer of ferroptosis for the treatment of Burkitt lymphoma

(BL), but artesunate not only induces ferroptosis in BL cells but also induces a

strong UPR. Activation of the ATF4-CHOP-CHAC1 pathway induces an ERS response,

while CHAC1 reduces GSH levels, decreases cell tolerance to ROS and lipid

peroxidation, and increases ferroptosis. Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) and desferriamine

not only inhibit ferroptosis but also inhibit ERS [39]. Ferroptosis inducers can

also induce an increase in PUMA expression upregulated by p53 through the

ATF4-CHOP-CHAC1 pathway, thereby causing ERS [38]. In a model of cadmium-induced

hepatocyte damage, cadmium induced ferroptosis in hepatocytes and activated the

PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP pathway to induce ERS, and the iron chelating agent

deferriamine effectively inhibited ferroptosis and ERS [40]. Activation of the

PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP-CHAC1 pathway may be an important factor in the

activation of ERS by ferroptosis inducers. The pathways by which ferroptosis

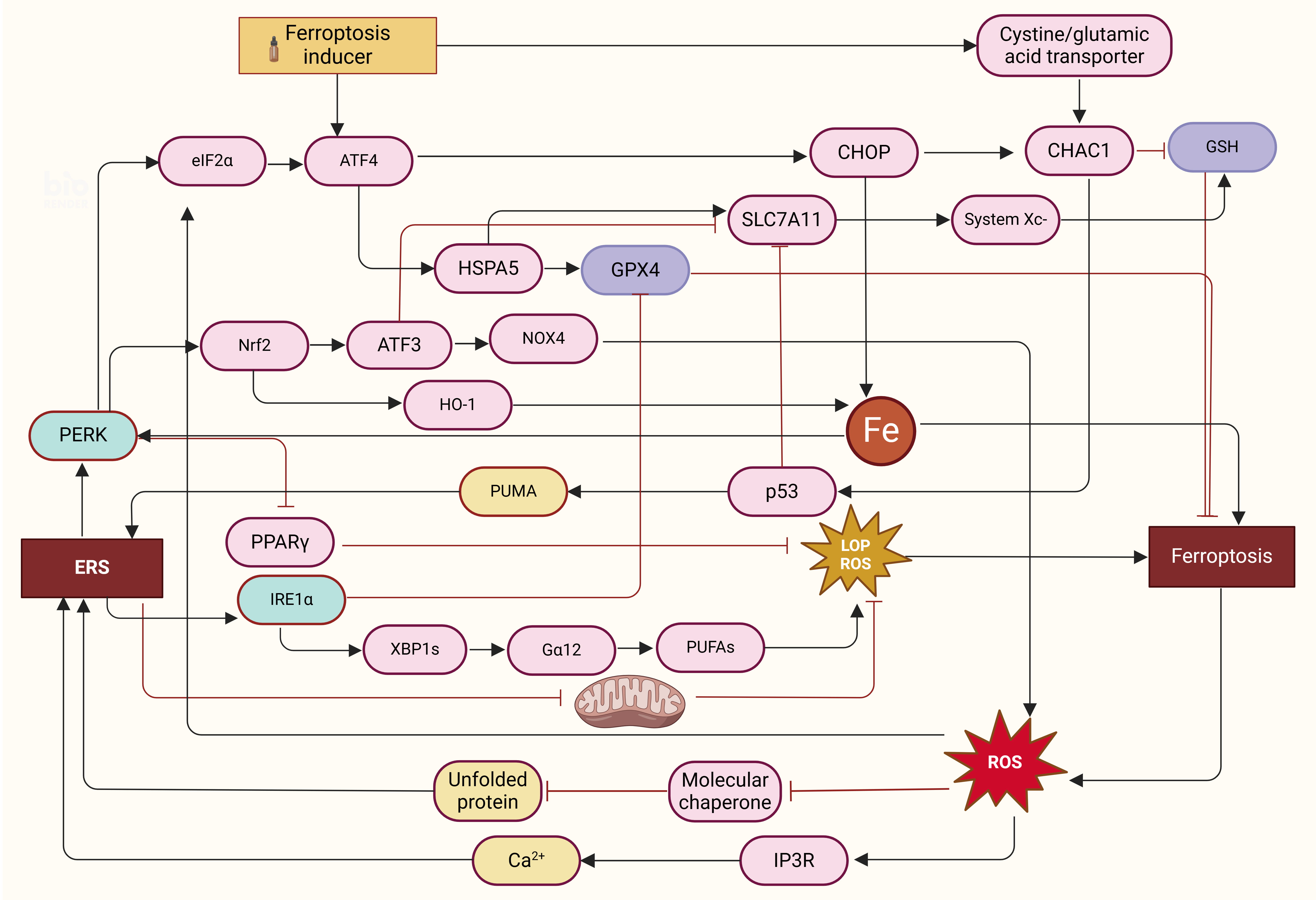

induces ERS are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The mutual regulatory mechanism between ERS and endoplasmic

death. (1) Ferroptosis induces ERS: Ferroptosis can inhibit the chaperone

function of molecules by releasing a large number of ROS, resulting in the

accumulation of a large number of unfolded proteins, and binding with IP3R

releases a large amount of Ca accumulation, resulting in ERS. Excess iron

activation via the PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP pathway induced increased

expression of PUMA. Ferroptosis inducers can inhibit cystine-glutamate exchange

in cells and increase the expression of CHAC1. (2) Ferroptosis induced by ERS:

ERS induces mitochondrial dysfunction and activates

PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP, PERK-Nrf2-HO-1, PERK-PPAR,

PERK-P53-SLC7A11-System Xc-, PERK-Nrf2-ATF3-SLC7A11/NOX4, and

IRE1-XBP1s-G12-PUFAs to induce ferroptosis. (3) ERS

negatively regulates ferroptosis: ERS increases the levels of System Xc- and GSH

and the activities of System Xc- and GPX4 in cells and reduces the production of

lipoperoxide by activating the PERK-ATF4-HSPA5/SLC7A11 pathway. ERS, endoplasmic

reticulum stress; ROS, reactive oxygen species; IP3R, inositol receptor

1,4,5-triphosphate; PUMA, p53 to upregulate the expression of apoptosis; GSH,

glutathione; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; LOP, lipid oxidation product.

4.2 ERS Induces Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is regulated by ERS, and under certain conditions, ERS can promote

ferroptosis. The PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP pathway is not only involved in

ferroptosis-induced ERS but also involved in ferroptosis induced by ERS. Xu

et al. [41] reported that the levels of iron ions and phospholipids in

the intestinal epithelial cells of the ulcerative colitis (UC) group were

significantly greater than those in the control group, and the observed

mitochondrial atrophy was consistent with the morphological characteristics of

ferroptosis. These findings suggested that ferroptosis may be closely related to

UC. However, the activation of PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP pathway was also

observed during this process. Combining PERK inhibitors with RSL3 (a ferroptosis

inducer) did not inhibit PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP and ERS activation but

also reduced ferroptosis in cells. ERS was also found to activate the

PERK/eIF2 signalling pathway and induce mitochondrial dysfunction to

regulate ROS production and promote ferroptosis in cells induced by whole-smoke

condensates [42]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) is involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism and blood

glucose. PPAR is also involved in ferroptosis induced by ERS. When ERS

occurs, the PERK signalling pathway is activated, the expression of

PPAR is inhibited, the level of PPAR decreases, and the level

of lipid peroxide increases, promoting ferroptosis [43, 44]. Additionally, PERK

can upregulate p53 to inhibit the transcription of SLC7A11, decreasing the

activity of System Xc- and promoting ferroptosis [45]. In exploring novel

therapeutic strategies for lung cancer, Fu et al. [46] also reported

that biomineralized liposomes (LDMs) containing dihydroartemisinin (DHA) and

pH-responsive calcium phosphate (CaP) can drive and enhance ferroptosis by

inducing ERS. Mechanistically, CaP causes a sharp increase in the intracellular

Ca concentration, triggering intense ERS, followed by mitochondrial

dysfunction, ROS accumulation, and ferroptosis. This is followed by a surge of

Ca entering the cell through iron pathways on the cell membrane, driving

the “Ca burst-ER stress-ferroptosis” cycle. Further experiments revealed

that the process by which ERS promotes ferroptosis is also the process by which

ROS and LPO accumulation trigger cell swelling and cell membrane destruction.

Nrf2 is also involved in ERS-induced ferroptosis. Nrf2 is an upstream element

involved in the PERK-Nrf2-HO-1 cascade in ERS. Activated Nrf2 activates target

genes, including HO-1, and increases HO-1 expression. HO-1 metabolizes

heme to Fe and induces ferroptosis by regulating the increase in unstable

iron content and ROS production in the iron pool [13, 47]. ATF3 is an ERS-induced

transcription factor that can regulate the transcription of target genes

according to the cellular environment [48]. When activated, Nrf2 can bind to the

ATF3 promoter and upregulate the expression of ATF3 through ROS, inhibiting the

expression of SLC7A11 and resulting in reduced activity of System Xc-, a lack of

intracellular GSH, the promotion of lipid peroxidation, and the induction of

intracellular ferroptosis [49]. ATF3 can also upregulate the expression of NADPH

oxidase 4 (NOX4), activate NADPH oxidase, promote the production of superoxide

and ROS, and promote iron-mediated cell death [50]. Therefore, ATF3 plays an

important role in the regulation of ferroptosis by ERS. IRE1 is also

involved in the regulation of ferroptosis. On the one hand, IRE1 can

inhibit GPX4 expression and promote ferroptosis; on the other hand,

IRE1 can promote the transcription of XBP1s and activate G12

to promote iron peroxide-mediated death in PUFAs [51, 52]. The pathways by which

ferroptosis is induced by ERS are shown in Fig. 1.

4.3 ERS Inhibits Ferroptosis

ERS and ferroptosis coparticipate in cell death. Under certain conditions, ERS

can inhibit ferroptosis and participate in cancer cell resistance. In cancer cell

ferroptosis induced by ferroptosis inducers, the ERS response is simultaneously

activated, and the PERK-eIF2-ATF4 pathway inhibits ferroptosis by

upregulating the expression of HSPA5, System Xc-, and other molecules [53]. When

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells were treated with a certain dose of

erastin, the transcriptional translation level of the ER chaperone HSPA5 was

significantly greater than that in the control group. The PERK and

eIF2-ATF4 pathways were also activated in these cells, the expression

of ATF4 and the molecule CHOP was upregulated, and the expression of the ATF4

target gene HSPA5 was also upregulated. Erastin-induced lipid peroxidation can be

significantly enhanced by inhibiting HSPA5 expression via RNA interference (RNAi)

or knocking out the ATF4 gene, leading to ferroptosis. The above results

indicate that HSPA5 can inhibit ferroptosis in PDAC cells, which might be related

to the inhibition of GPX4 degradation by HSPA5 to improve the intracellular

antioxidant capacity [54]. As an anticancer drug, dihydroartemisinin can induce

ferroptosis in glioma cells, and the activation of PERK-ATF4-HSPA5 pathway was

also found when studying the related mechanism; additionally, upregulated HSPA5

increased the activity of GPX4 and reduced the production of lipoperoxide [53].

ATF4 is highly expressed in injured cardiomyocytes induced by Sorafenib (SOR),

and ATF4 can enhance the expression of SLC7A11, the active regulatory subunit of

System Xc-, through transcriptional regulation, increase the activity of System

Xc-, inhibit ferroptosis, and promote the survival of cardiomyocytes [55].

Harding et al. [56] reported that wild-type mouse fibroblasts were prone

to amino acid depletion when the ATF4 gene was knocked out. In the

absence of exogenous amino acid supplementation, peroxides rapidly accumulate in

cells, resulting in cell death. Ferroptosis inducers such as artesunate and

dihydroartemisinin can induce ferroptosis in cells and negatively regulate

ferroptosis, and ERS is activated. The expression of HSPA5 and SLC7A11 increased

under the regulation of ATF4, which increased the levels of System Xc- and GSH

and the activities of System Xc- and GPX4 in cells and reduced the occurrence of

ferroptosis [53]. This finding suggested that the expression level of ATF4 may be

closely related to the sensitivity of cells to oxidative stress and that ATF4 may

be another important molecule involved in the regulation of ferroptosis by ERS.

The pathways by which ERS inhibits ferroptosis are shown in Fig. 1.

5. The Role of ERS and Ferroptosis Cross-Talk in Common Liver Diseases

5.1 Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

The disease progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encompasses

a range of diseases from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic hepatitis (NASH),

which can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a metabolic

syndrome of liver damage with an unknown pathogenesis. However, ferroptosis and

ERS are closely related to the occurrence of NAFLD. IRE1/XBP1 plays an

important role in lipid regulation in hepatocytes. IRE1/XBP1 can

directly upregulate the regulation of sterol regulatory element-binding

protein-1c (SREBP-1c), which is involved in fatty acid synthesis. When

IRE1/XBP1 is continuously activated, it leads to the accumulation of

triglycerides and cholesterol in the liver, resulting in NAFLD [57]. GRP78 is an

ER molecular chaperone, and the expression of ATF6, an ERS receptor, is

significantly increased in the cells of mice fed a high-fat diet. Aerobic

exercise can reduce the expression levels of GRP78 and ATF6 and reduce ERS, thus

improving the symptoms related to NAFLD [58]. PERK is also activated in ERS

through the PERK-eIF2-ATF4 pathway to increase the intracellular CHOP

level, activate the CHOP pathway, and induce cell apoptosis; at the same time,

CHOP can induce PPAR expression and promote lipid accumulation in NAFLD

[59]. In NAFLD cells, the increased expression level of lysophosphatidylcholine

acyltransferase (LPCAT) increases the content of intracellular amino acids, which

are one of the substrates of PUFAs. The increase in the content of amino acids

can significantly increase the level of lipid peroxidation and induce

ferroptosis. Although GPX4 can inhibit ferroptosis, the overexpression of GPX4 in

liver cells can activate enolase3 (ENO3) and increase the content of

intracellular lipids to induce ferroptosis [60]. Ferroptosis and ERS participate

in the occurrence of NAFLD and can regulate each other. Sodium arsenite (NaAsO2)

is a carcinogen that can cause immune inflammation, fibrosis, and even cancer in

liver cells. Ferroptosis in a NaASO2-induced NAFLD rat model involved ERS. After

NaAsO2 treatment, the iron content significantly increased, MDA, ACSL4, and

5-hydroxy eicosatetraenoic acid (5HETE) expression increased, GSH expression

decreased, and linear membrane rupture and ridge reduction were observed in rat

hepatocytes. When liver cells were pretreated with Fer-1 or ACSL4 inhibitors,

GPX4 levels were significantly restored, mitochondrial structure and morphology

were significantly improved, and ferroptosis was inhibited. In rat hepatocytes

treated with NaAsO2, the expression of IRE1, one of the receptors of

ERS, was upregulated, which activated ERS, and IRE1 promoted NAFLD and

ferroptosis in hepatocytes by upregulating 5-HETE, ACSL4, and MDA and inhibiting

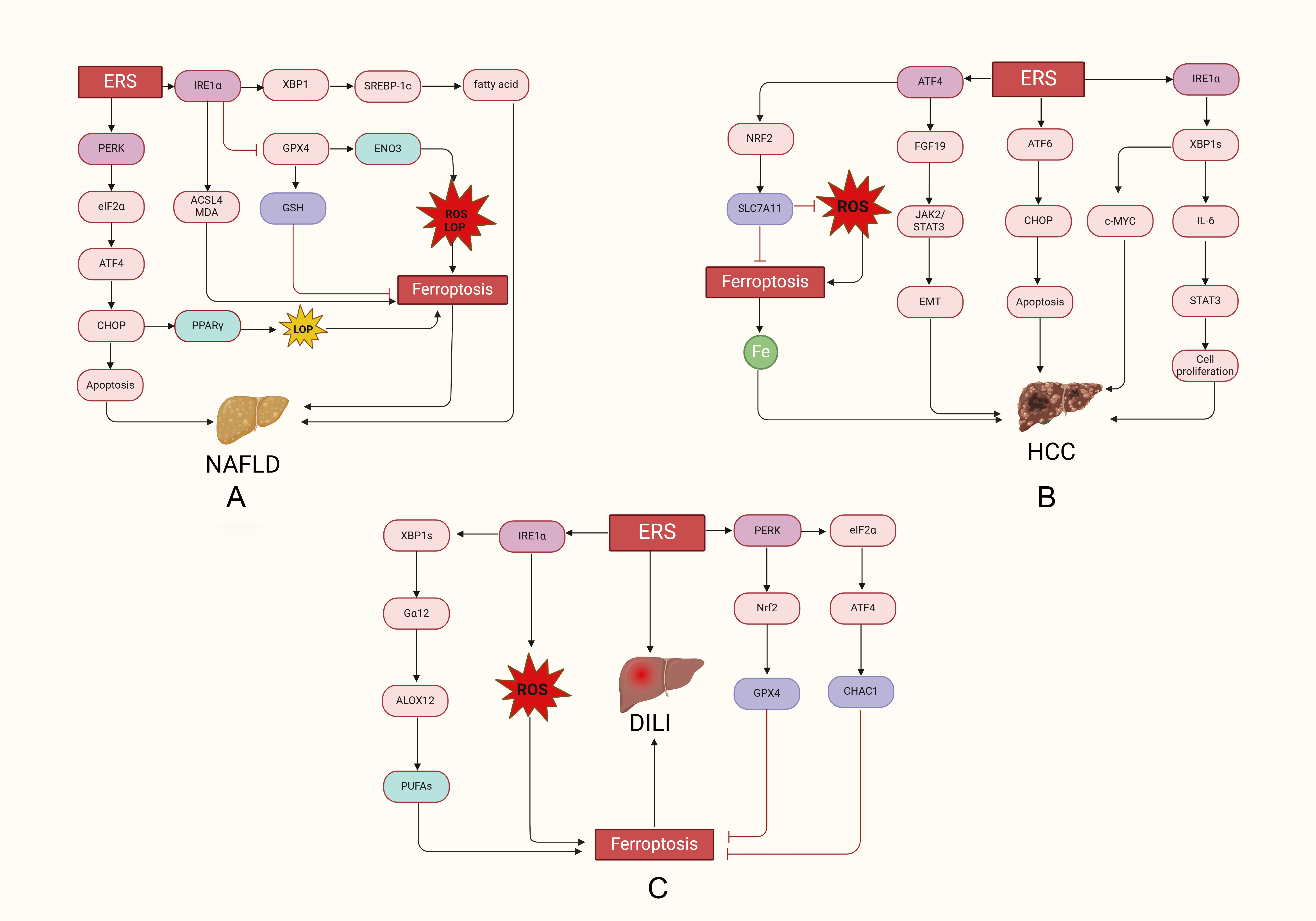

GPX4 expression [51]. The ferroptosis and ERS pathways in NAFLD are shown in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Ferroptosis and the regulation of ERS in liver disease. (A)

In NAFLD, ERS increased the expression of IRE1, PERK, ACSL4 and GRP78

related proteins, and IRE1 promoted ferroptosis in hepatocytes by

upregulating 5-HETE, ACSL4 and MDA and inhibiting GPX4 expression. (B) In HCC,

ERS promotes the growth and proliferation of cancer cells through the

ATF4-FGF19-JAK2/STAT3-EMT, IRE1-XBP1s-IL-6-STAT3, and

IRE1-XBP1s-c-MYC pathways and inhibits ferroptosis through the

PERK-ATF4-Nrf2-SLC7A11 pathway. (C) In DILI, ERS induces ferroptosis in

hepatocytes by activating IRE1-XBP1-G12-ALOX12-PUFAs and PERK

eIF2-ATF4-CHAC1, but ERS inhibits ferroptosis in hepatocytes via PERK

Nrf2-GPX4. NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; DILI, Drug-induced liver

injury; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PERK, protein kinase R-like ER kinase;

ACSL4, 4acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; GRP78, glucose-regulated

protein 78; MDA, malondialdehyde.

5.2 Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

HCC is a malignant tumor that occurs in hepatocytes or intrahepatic bile duct

epithelial cells and has a poor prognosis, and it is urgent to explore the

pathogenesis of HCC [61]. Recent studies have shown that HCC can develop from

NAFLD and viral hepatitis B [62, 63]. The team of Wu [64] reported that ERS

was activated in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-induced HCC cells. HBV significantly

increased the expression of ERS-related proteins BiP and ATF4, and the secretion

of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) increased under the regulation of ATF4,

which activated Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)

pathway and leaded to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in HCC cells. EMT

is closely related to the occurrence of HCC, and when EMT is inhibited, it can

inhibit the formation of hepatic vessels [65, 66]. IRE1 is also involved

in the development of HCC. IRE1 is overexpressed in HCC cells, and a

large amount of IRE1 accumulates in cells to stimulate RNase activity

and catalyze the formation of XBP1s. XBP1s increased IL-6 expression through

signal transduction, induced STAT3 activation, and promoted the proliferation of

HCC cells. Treatment of HCC with toluene can significantly improve the

value-added effect of IL-6-STAT3 on HCC [67]. c-MYC is closely related to the

occurrence of cancer and has a strong carcinogenic effect, participating in the

drug resistance of cancer cells. Knockout of IRE1 can inhibit

the IRE1-XBP1s-C-MYC pathway, which can significantly improve the

resistance of HCC to sorafenib [60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69]. In addition, ATF6 and its target gene

(CHOP apoptosis gene) are involved in the development of HCC [70].

ATF6/CHOP is significantly activated in hepatocytes treated with cytochrome P450

2E1 (CYP2E1), which inhibits the apoptotic pathway of hepatocytes and promotes

the occurrence and development of HCC [71]. Moreover, single nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs) in ATF6 significantly increase the risk of HCC

[72]. Studies have shown that long-term iron overload in cells can cause cell

damage, which eventually manifests as HCC [73]. Excessive accumulation of iron in

HCC can promote the proliferation of cancer cells and promote the growth of

tumors [74]. Moreover, studies have shown that the expression of GPX4, a

regulator of ferroptosis, is significantly increased in HCC, which may be related

to the reduction in oxidative stress in cancer cells caused by GPX4 [75]. Both

ERS and ferroptosis regulators are involved in the development of HCC, and

inducing ferroptosis in HCC is a promising therapeutic strategy. Thus, there is

mutual regulation between ERS and ferroptosis, and the same is true in HCC. ATF4

is a transcription factor activated by ERS, and ATF4 and Nrf2 can coupregulate

the expression of SLC7A11 in HCC, reduce oxidative stress, and inhibit

ferroptosis [76]. The ferroptosis and ERS pathways in HCC are shown in Fig. 2B.

5.3 Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI)

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) refers to liver damage caused by the drug

itself or its metabolites, as well as due to the supersensitivity or tolerance of

special constitutions to the drug during the use of the drugs, which can lead to

liver failure. Moreover, liver injury caused by acetaminophen (APAP) is more

common [77]. APAP is catalyzed by cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) to produce

N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), which is a highly toxic product. An

excessive concentration of APAP in vivo increases GSH consumption and

NAPQ and ROS levels, and this process leads to ferroptosis and ERS, ultimately

leading to hepatocyte death [78, 79]. ERS is involved in drug-induced liver

damage, and Galpha12 (G12) is associated with cell activity.

Apap-induced acute liver damage in patients with significantly increased

G12 expression, downregulated GPX4 expression, lipid peroxide

accumulation and typical ferroptosis may also be observed. An increase in ERS was

positively correlated with the expression of G12 and trans-activated

G12 through the IRE1-XBP1 pathway. Moreover, G12

can promote the peroxidation of PUFAs and induce ferroptosis in hepatocytes by

inducing arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase (ALOX12) [52]. These results indicate that

ERS can promote ferroptosis in hepatocytes by increasing the expression of

G12 and that G12 is expected to be a new target for the

treatment of DILI. Xu and his team [80] reported the protective effect of ERS in

mouse hepatocytes with APAP-induced acute liver injury, which promoted

ferroptosis in hepatocytes through the activation of

PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHAC1. The morphology of mitochondria is a

characteristic feature of ferroptosis, and a large amount of ROS, iron and lipid

peroxides can accumulate in a liver injury model induced by carbon tetrachloride

(CCl). Similarly, the expression levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4 were

significantly lower in these cells than in control cells. However, bicyclol can

improve ferroptosis by directly increasing the activity of other enzymes. This

effect can also be achieved by activating another branch of PERK known as the

Nrf2-GPX4 axis [81]. In addition, CCl can lead to decreased transcription

levels of antioxidant enzymes, including GSH and superoxide dismutase (SOD), as

well as increased ROS levels and activation of the ERS-related protein

IRE1-. The production of excessive ROS further promotes the occurrence

of ERS. P. umbrosa can significantly improve ferroptosis in hepatocytes

and ERS [82]. The ferroptosis and ERS pathways involved in DILI are shown in Fig. 2C.

6. The Application of ERS and Ferroptosis in the Treatment of Liver

Disease

Compared with that in normal cells, the metabolism of iron in cancer cells is

significantly increased, and the demand for iron is also increased, so cancer

cells have a higher susceptibility to ferroptosis. Sorafenib is a systemic

therapy for the treatment of advanced HCC, and the development of drug resistance

is the main reason for its limited use. Metallothionein (MT)-1G is an

Nrf2-dependent protein that can reduce the levels of GSH and lipid peroxidation

in HCC, inhibiting ferroptosis in cells. The upregulation of MT-1G expression is

related to the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to sorafenib [83].

Additionally, ERS participates in sorafenib resistance by upregulating pyruvate

kinase subtype M2 (PKM2) through the microRNA-188-5p (miR-188-5p)/heterogeneous

nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2B1 (hnRNPA2B1) pathway [84]. These findings

demonstrate that both ferroptosis and ER are involved in sorafenib resistance.

The Nrf2, as the junction of ferroptosis and ER stress, may effectively improve

sorafenib resistance and enhance its anticancer efficacy. Currently, there is a

lack of effective drugs for NAFLD treatment, but acacetin can effectively improve

NAFLD by leveraging the crosstalk between ERS and ferroptosis. Acacetin can

reduce the expression of MDA, GSH, ATF6, and CHOP in high-fat diet-fed mice,

inhibiting ferroptosis and ERS. Acacetin can directly inhibit ferroptosis and

indirectly inhibit the expression of ACSL4, a promoter of ferroptosis, by

inhibiting the ATF4-CHOP axis in ERS. Therefore, acacetin has a strong ability to

inhibit lipid accumulation in liver cells and is expected to become a candidate

drug for the treatment of NAFLD in the future [85]. ERS and ferroptosis promote

each other and participate in the occurrence and development of drug-induced

liver injury. Salidroside inhibited the cationic transport regulator CHAC1 and

the PERK-eIF2-ATF4 pathways in mouse models, reducing GSH degradation

and the intracellular iron content, inhibiting ferroptosis, and preventing

APAP-related liver damage caused by ERS. Increased transcription of the PERK

activators CCT020312 and ATF4 can reduce the inhibitory effect of salidroside on

CHAC1. Additionally, the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase

(AMPK)/sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) signal transduction plays an important role in the

inhibition of ferroptosis and ERS by salidroside, and when SIRT1 is inhibited,

the protective effect of salidroside on ferroptosis and ERS can be weakened [80].

In fact, many studies have shown that daglizin and irisin can inhibit ferroptosis

and ERS by activating SIRT1, reducing ROS and MDA production, reducing the

intracellular iron content, and inhibiting the PERK-eIF2-ATF4 axis

[86, 87]. These findings suggest that the activation of SIRT1 may be a valuable

target for evaluating DILI treatment.

7. Summarize

According to recent studies, ferroptosis can induce ERS by activating the

PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP pathway and upregulating PUMA and ROS, while ERS

can negatively regulate ferroptosis by activating the PERK-ATF4-HSPA5/System Xc-,

PERK-Nrf2-GPX4, and other pathways. However, ERS can also induce ferroptosis

through PERK-eIF2-ATF4-CHOP, PERK-Nrf2-HO-1, and other pathways.

Additionally, cross-talk between ferroptosis and ERS also plays an important role

in diseases. In NAFLD, HCC and DILI, ferroptosis characteristics are observed,

such as increased ROS and lipid peroxides, as well as iron accumulation, while in

NAFLD, ERS manifests as increased expression of IRE1, PERK, and GRP78.

In HCC, the expression of ERS-related proteins such as IRE1, XBP1s,

ATF6, and CHOP was upregulated, and ferroptosis was inhibited by

PERK-ATF4-Nrf2-SLC7A11. In DILI, the activation of the

IRE1-XBP1-G12-ALOX12 pathway promotes ferroptosis, but ERS

inhibits ferroptosis through the PERK-Nrf2-GPX4 pathway. Understanding the

circumstances under which the ability of ERS to induce ferroptosis is greater

than that of ERS to negatively regulate ferroptosis may lead to the

identification of new therapeutic targets for overcoming cell drug resistance.

Moreover, the targeting of ferroptosis plays an important role in preventing

diseases mediated by ROS, lipid peroxidation and inflammatory infiltration. The

involvement of the ERS also provides additional options and directions for the

treatment of related diseases. The combination of ERS and ferroptosis inhibitors

may achieve improved efficacy. However, the mechanism of crosstalk related to ERS

and ferroptosis has still not been studied in detail, and the crosstalk between

ERS and ferroptosis has not yet undergone clinical translation. A further

elucidation of the crosstalk mechanism between ERS and ferroptosis for clinical

application will be beneficial for the treatment of related diseases.

Author Contributions

MH, YW, WL and XW conceived and designed the study. MH, YW,

and XW drafted the manuscript. MH and YW revised the paper. WL edited the

article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have

participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all

aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(82100894, 82100630).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.