1 The School of Public Health, Fujian Medical University, 350122 Fuzhou, Fujian, China

2 Department of Clinical Nutrition, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, 362000 Quanzhou, Fujian, China

3 Department of Dermatology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, 362000 Quanzhou, Fujian, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: This study investigated the impact of salvianolic acids, derived from Danshen, on melanoma cell growth. Specifically, we assessed the ability of salvianolic acid A (Sal A) to modulate melanoma cell proliferation. Methods: We used human melanoma A2058 and A375 cell lines to investigate the effects of Sal A on cell proliferation and death by measuring bromodeoxyuridine incorporation and lactate dehydrogenase release. We assessed cell viability and cycle progression using water soluble tetrazolium salt-1 (WST-1) mitochondrial staining and propidium iodide. Additionally, we used a phospho-kinase array to investigate intracellular kinase phosphorylation, specifically measuring the influence of Sal A on checkpoint kinase-2 (Chk-2) via western blot analysis. Results: Sal A inhibited the growth of A2058 and A375 cells dose-responsively and induced cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase. Notably, Sal A selectively induces Chk-2 phosphorylation without affecting Chk-1, thereby degrading Chk-2-regulated genes Cdc25A and Cdc2. However, Sal A does not affect the Chk1-Cdc25C pathway. Conclusions: Salvianolic acids, especially Sal A, effectively hinder melanoma cell growth by inducing Chk-2 phosphorylation and disrupting G2/M checkpoint regulation.

Keywords

- salvianolic acid A

- Danshen

- Chk2

- Cdc25A

- melanoma

Melanoma, derived from melanocytes, is the most pernicious form of skin cancer and is characterized by its invasive nature and high mortality rate [1]. Melanoma, in its nascent stages, is amenable to surgical excision; however, the disease frequently progresses insidiously, with approximately one-third of patients in advanced stages experiencing metastasis to critical organs, including lymph nodes, the liver, lungs, and brain [2]. Such dissemination requires a multipronged systemic approach that incorporates targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and chemotherapeutic regimens. These therapeutic agents have demonstrated marginal efficacy in managing metastatic melanoma, with only incremental advances in patient survival [3, 4].

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, belonging to the Lamiaceae family and prominently referred to as Danshen in traditional Chinese medicine, is known for its antineoplastic properties [5, 6]. This medicinal herb encompasses a range of chemical compounds, among which tanshinones and salvianolic acids are particularly popular for their therapeutic efficacy in treating cardiovascular diseases and cancer. These compounds were extensively investigated for their role in modulating inflammatory responses and cellular signaling pathways [7, 8, 9].

Salvianolic acids and Danshensu, the principal water-soluble constituents of Danshen, have been identified as key agents in its pharmacological profile [10]. Specifically, Danshensu has been recognized for its ability to suppress the growth of various cancer cell types, including breast, lung, and oral cancers, through its effects on the AKT (also known as protein kinase B, PKB) and p38 signaling pathways [11, 12, 13, 14]. Furthermore, Danshensu can downregulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-2, MMP-9, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in melanoma cells, thereby reducing their invasive behavior and angiogenic potential [15].

Salvianolic acids are one of the most abundant compounds in Danshen, and the scientific community has extensively documented their mechanisms of action on various cancer cells [16, 17, 18]. However, the specific effect of these compounds on melanoma cell growth remains unclear. This gap in the literature underscores the novelty of the current study, which aimed to confirm the effects of salvianolic acid A (Sal A) and salvianolic acid B (Sal B) on melanoma cell proliferation. The study determined checkpoint kinase-2 (Chk-2) to be the precise molecular target of salvianolic acid within the cellular milieu using phosphorylated protein expression profiling. Research on the Chk-2 signaling pathway reveals that salvianolic acid exerts regulatory effects on the growth of melanoma cells, potentially paving the way for new therapeutic strategies.

Human malignant melanoma cell lines A2058 and A375 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in a medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)

containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 units/mL

penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were maintained in a

humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO

For cell viability assessment, 2

Cell proliferation was analyzed by incorporating bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) into

DNA. Briefly, cells were seeded in triplicate in 24-well culture plates at a

density of 1

Cells were placed in 6-cm culture dishes at a density of 1

A2058 cells were placed in 6-cm culture dishes at a density of 1

Cells were placed in 6-cm culture dishes at a density of 1

Antibodies used in this study included anti-phospho-Chk-1 (Ser 345),

anti-phospho-Chk-2 (Thr68), anti-Chk-1, anti-Chk-2, anti-phospho-p53 (Ser 15),

anti-Cdc25A, anti-Cdc25C, anti-Cyclin A, anti-Cyclin B, anti-Cdc2, all purchased

from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-

Cells were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) and according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly,

30 µM of siRNA was first dissolved in opti-minimum essential medium (MEM) culture medium and left at

room temperature for 15 minutes, then placed into cells that had been cultured in

Opti-MEM and cultured at 37 °C for 6 h. After removing the siRNA and

Opti-MEM, the culture medium was then replaced with 1% FBS-containing DMEM, and

the cells were cultured for an additional 48 h. Cdc25A and Cdc2 siRNAs were

purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and the sequences of the siRNAs targeted to Cdc25A

and Cdc2 are 5

The melanoma tissue cDNA array (MERT301) was purchased from Origene Technologies

(Rockville, MD, USA) and supplied the melanoma tissue cDNA array (MERT301).

Specific primer mixtures and SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine (StepOne PlusTM, Waltham, MA, USA) were used

to detect gene expression. The primer sequence for Cdc25A is as follows: forward

primer: 5

Cell viability, proliferation, and death metrics were reported

as mean

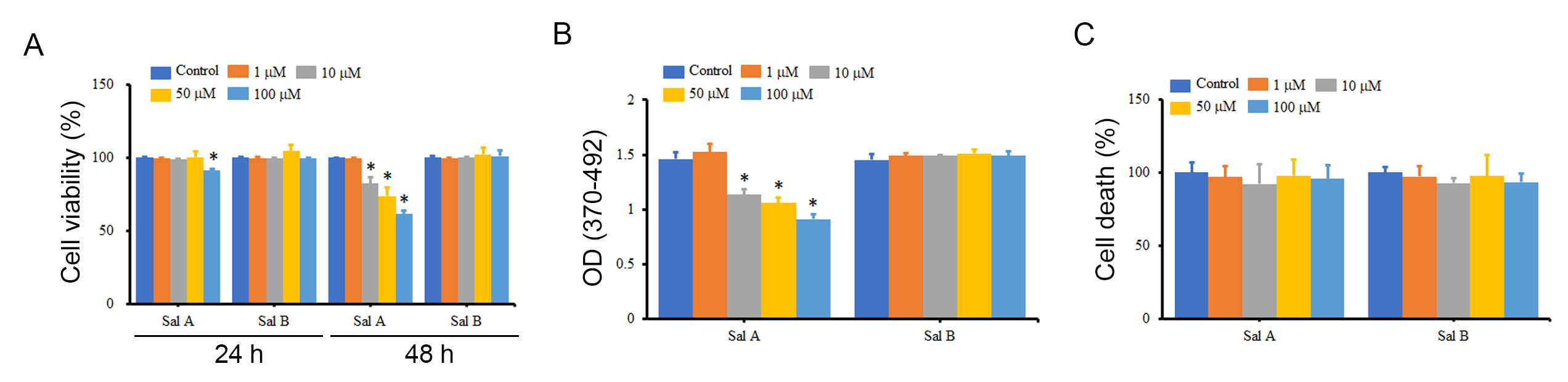

This study assessed the influence of salvianolic acids, specifically Sal A and Sal B, on melanoma cell viability using A2058 cells as a model. Fig. 1A showed that a 48-hour exposure to Sal A at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 µM notably reduced A2058 cell viability by 17.7 to 38.4%. In contrast, Sal B did not significantly affect viability. Subsequent analysis revealed that Sal A diminished A2058 cell proliferation to 62.3%–77.6% relative to the control, as depicted in Fig. 1B. Notably, Sal A did not trigger apoptosis in these cells (Fig. 1C). Conversely, Sal B exhibited no appreciable impact on either cell proliferation or death. These results suggest that the decrease in A2058 cell viability caused by Sal A is mainly due to the inhibition of cell proliferation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.The effects of Sal A and Sal B on the viability,

proliferation, and death of A2058 cells. A2058 cells were treated with different

concentrations of Sal A and Sal B for 24 h and 48 h, and the impact on cell

viability (A), cell proliferation (B), and cell death (C) was measured using

water soluble tetrazolium salt-1 (WST-1), BrdU incorporation assay, and LDH release, respectively. *p

Parallel observations were recorded with A375 cells, where Sal A elicited a decline in both cell viability and proliferation without inducing apoptosis, as delineated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Similarly, Sal B had no significant effect on A375 cell viability, cell proliferation, or cell death (Supplementary Fig. 1). Since Sal B did not have any impact on melanoma cancer cells. We focused on Sal A for the subsequent experiments; a 50 µM concentration of Sal A was selected to optimize potential therapeutic dosages.

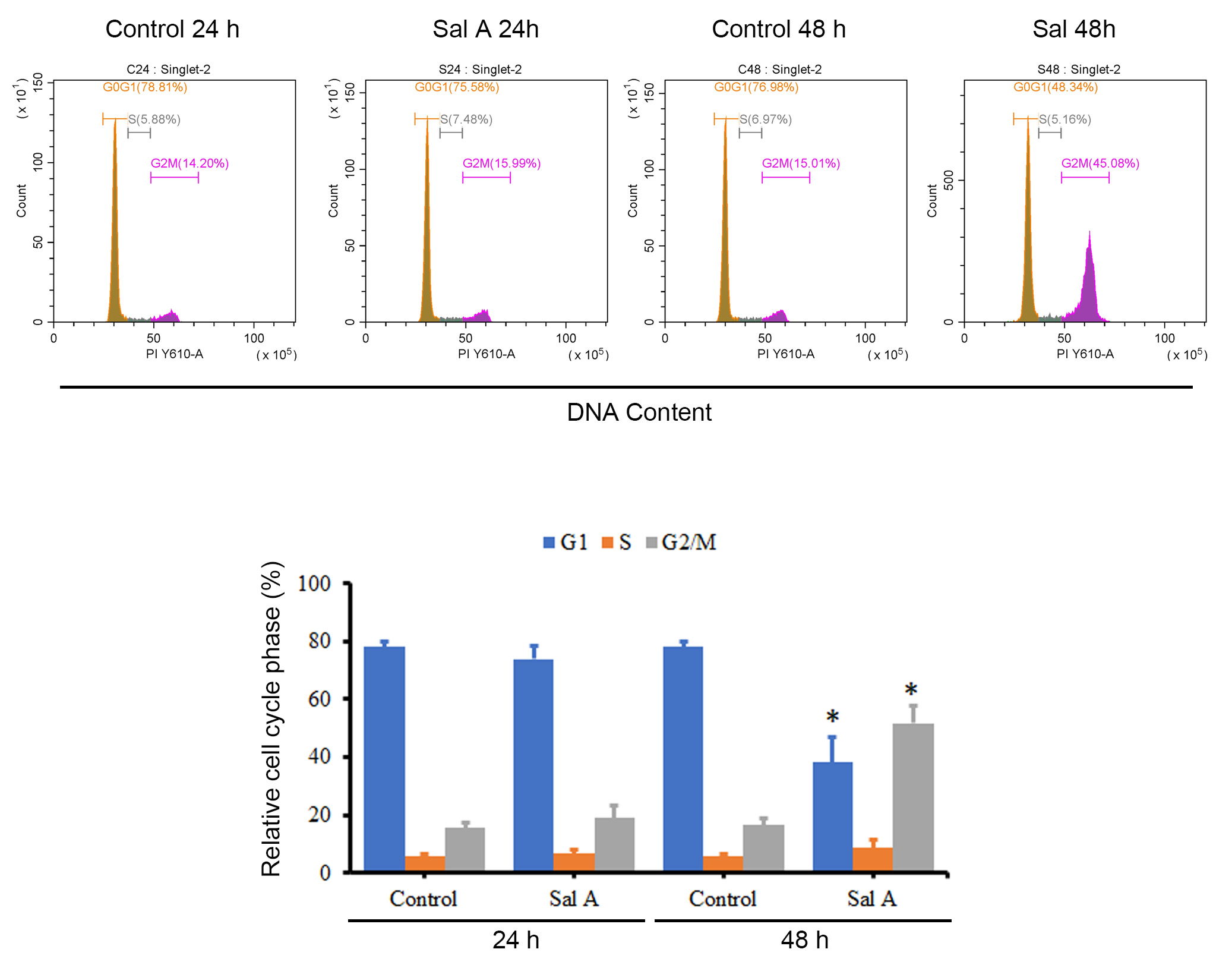

Given the inhibitory effect of Sal A on melanoma cell proliferation, further investigation into its impact on cell cycle progression was conducted. Fig. 2 reveals that a 48-hour treatment with Sal A precipitated a reduction in the G1 phase population and an augmentation in the G2/M phase population of A2058 cells relative to controls, suggesting an induced cell cycle arrest at the G2/M transition. Concordant findings were documented in A375 cells, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.The effect of Sal A on the cell cycle of A2058 cells. A2058

cells were treated with 50 µM Sal A for 24 h and 48 h, fixed and stained

with propidium iodide (PI), and the cell cycle was analyzed using flow cytometry. The presented data

are representative graphs and summarized as mean

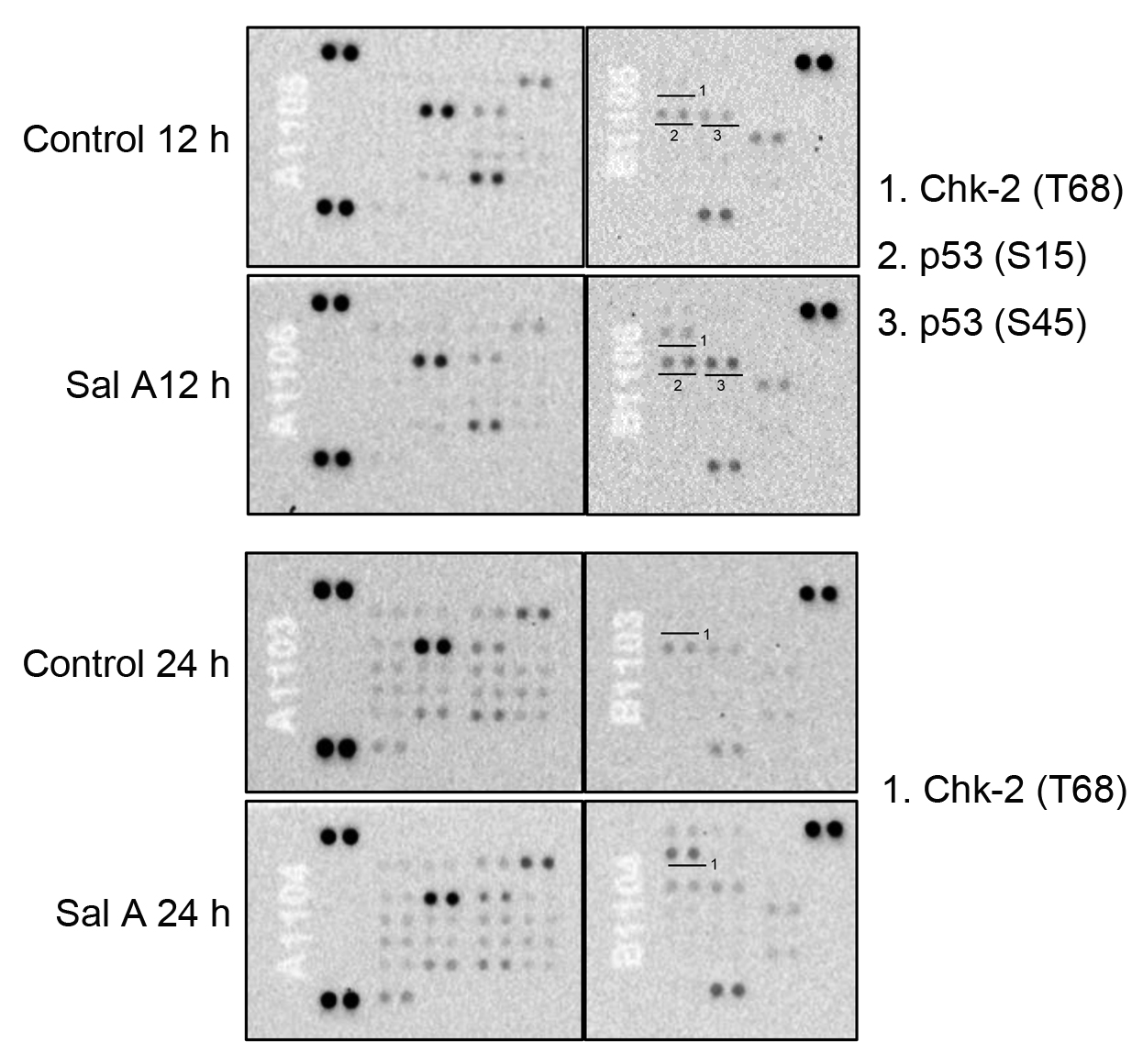

To identify the protein targets of Sal A in melanoma cells, a human phospho-kinase array was employed to profile the expression of key signaling proteins in A2058 cells post Sal A exposure. Fig. 3 indicated that a 12-hour treatment with Sal A upregulated the levels of phosphorylated p53 and Chk-2 compared to untreated controls. Notably, after 24 hours of Sal A treatment, the phosphorylation of Chk-2 remained pronounced, whereas phosphorylated p53 levels did not differ substantially from controls. Sal A appeared to selectively modulate the phosphorylation status of p53 and Chk-2 without broadly impacting other phosphorylated proteins within the cellular signaling network.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.The effect of Sal A on protein phosphorylation in A2058 cells. A2058 cells were treated with 50 µM Sal A for 12–24 h, and cell extracts were collected for human phospho-kinase array assays.

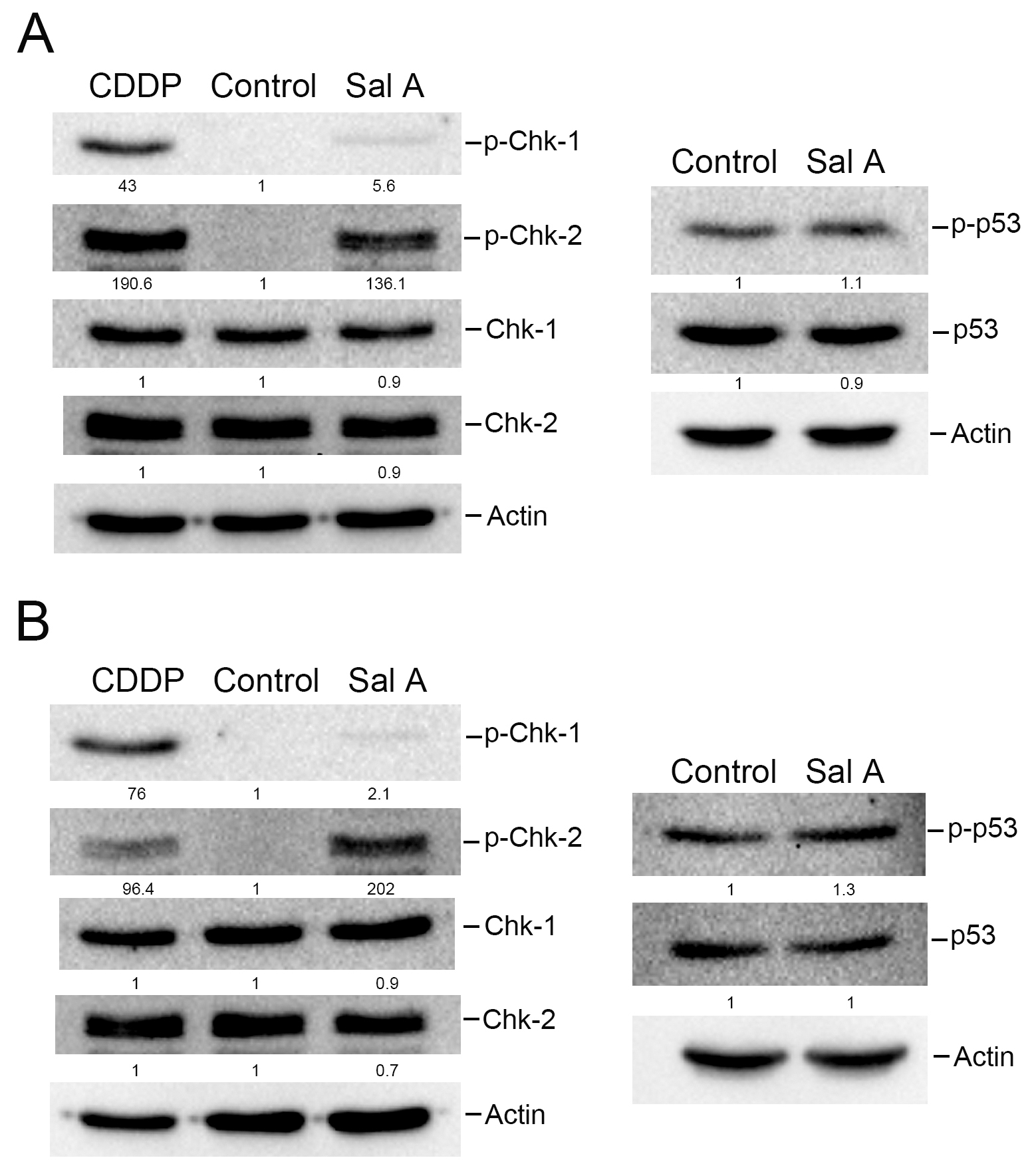

To corroborate the phospho-kinase array findings, Western blot analyses were conducted on cell lysates from Sal A-treated melanoma cells. The results from Fig. 4A indicate that treatment with the chemotherapeutic drug Cisplatin (CDDP) significantly improved the phosphorylation of Chk-1 and Chk-2 levels in A2058 cells after 24 h, whereas treatment with Sal A only slightly increased the phosphorylated Chk-1 levels but markedly increased the phosphorylated Chk-2 levels in A2058 cells. A similar upregulation of phosphorylated Chk-2 was detected in A375 cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we observed that 6-h Sal A treatment of A2058 cells with Sal A for 6 h induced phosphorylation of Chk-2 in the cells and maintained it for at least 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, the phosphorylated p53 expression was evaluated after 24 h of Sal A treatment. Fig. 4A,B indicate no notable alteration in phosphorylated p53 levels, suggesting that p53 does not play a major role in Sal A modulation of the melanoma cell cycle.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.The effect of Sal A on the expression of phospho-Chk-1, phospho-Chk2, and phospho-p53 in melanoma cells. A2058 cells (A) or A375 cells (B) were treated with 50 µM Sal A along with 10 µM Cisplatin (CDDP) for 24 h, and cell extracts were collected. Levels of Chk-1, Chk-2, and p53 were analyzed using western blotting.

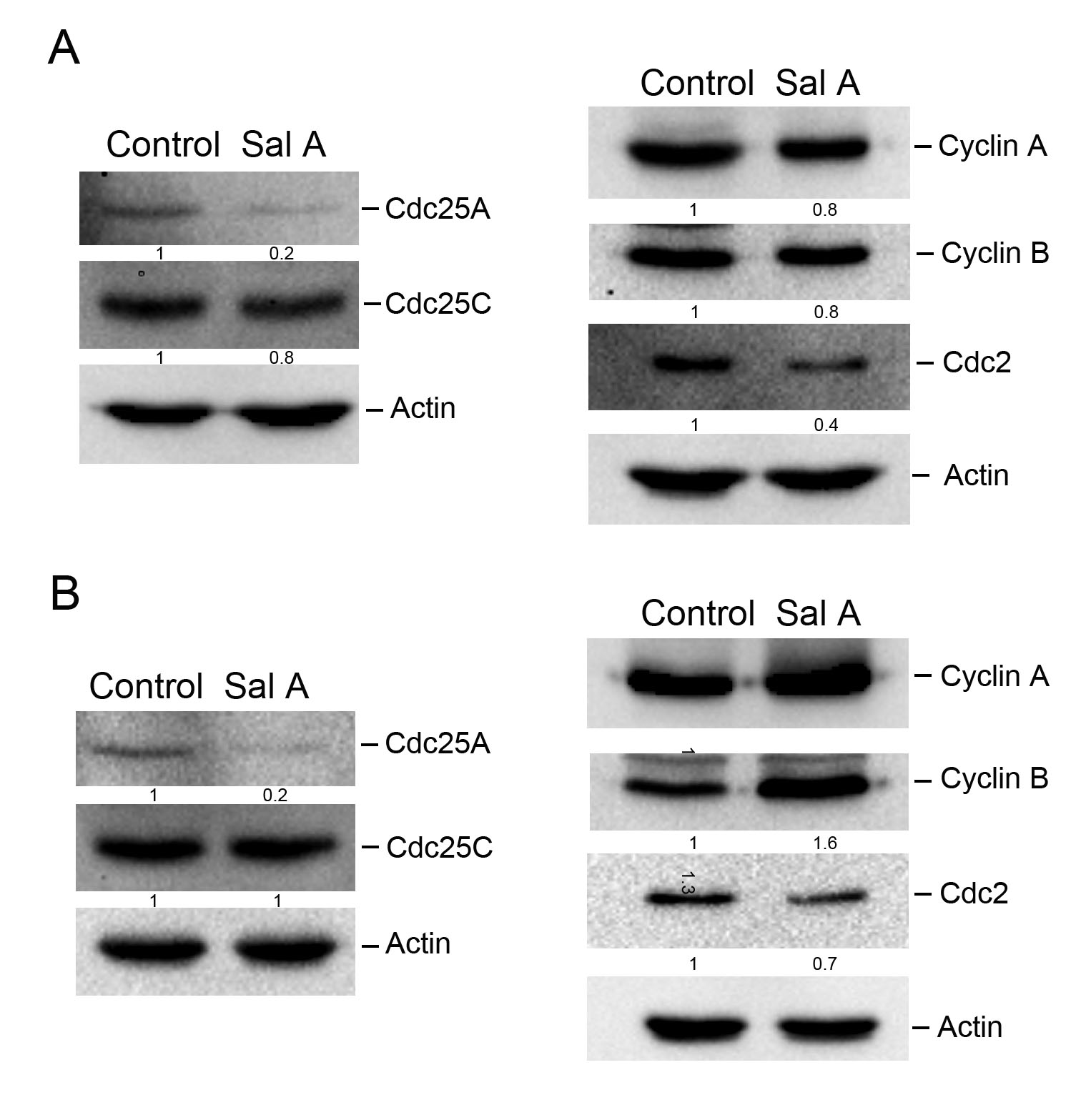

Chk-1 and Chk-2 are recognized as inhibitors of Cdc25C and Cdc25A proteins, contributing to downstream signal transduction events [19, 20]. Considering the upregulation of phosphorylated Chk-2 by Sal A, the investigation was expanded to examine its effects on Cdc25A and Cdc25C. Fig. 5A,B showed that Sal A suppressed Cdc25A expression in both A2058 and A375 cell lines, while Cdc25C levels were unaltered. Given the pivotal function of Cyclin A, Cyclin B, and Cdc2 in the G2/M phase transition, with Cdc2 being modulated by Cdc25A and Cdc25C [21, 22, 23]. Their expressions post Sal A exposure were also evaluated. Although Cyclin A and Cyclin B responses to Sal A varied across melanoma cell types, a consistent downregulation of Cdc2 was observed in both A2058 and A375 cells. Hence, the findings suggest that Sal A attenuates the production of both Cdc25A and Cdc2 proteins, implicating a targeted disruption of cell cycle regulation in melanoma cells.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.The effect of Sal A on the expression of G2 checkpoint-related proteins in melanoma cells. A2058 cells (A) or A375 cells (B) were treated with 50 µM Sal A for 24 h, and cell extracts were collected. Levels of Cdc25A, Cdc25C, Cyclin A, Cyclin B, and Cdc2 were analyzed using western blotting.

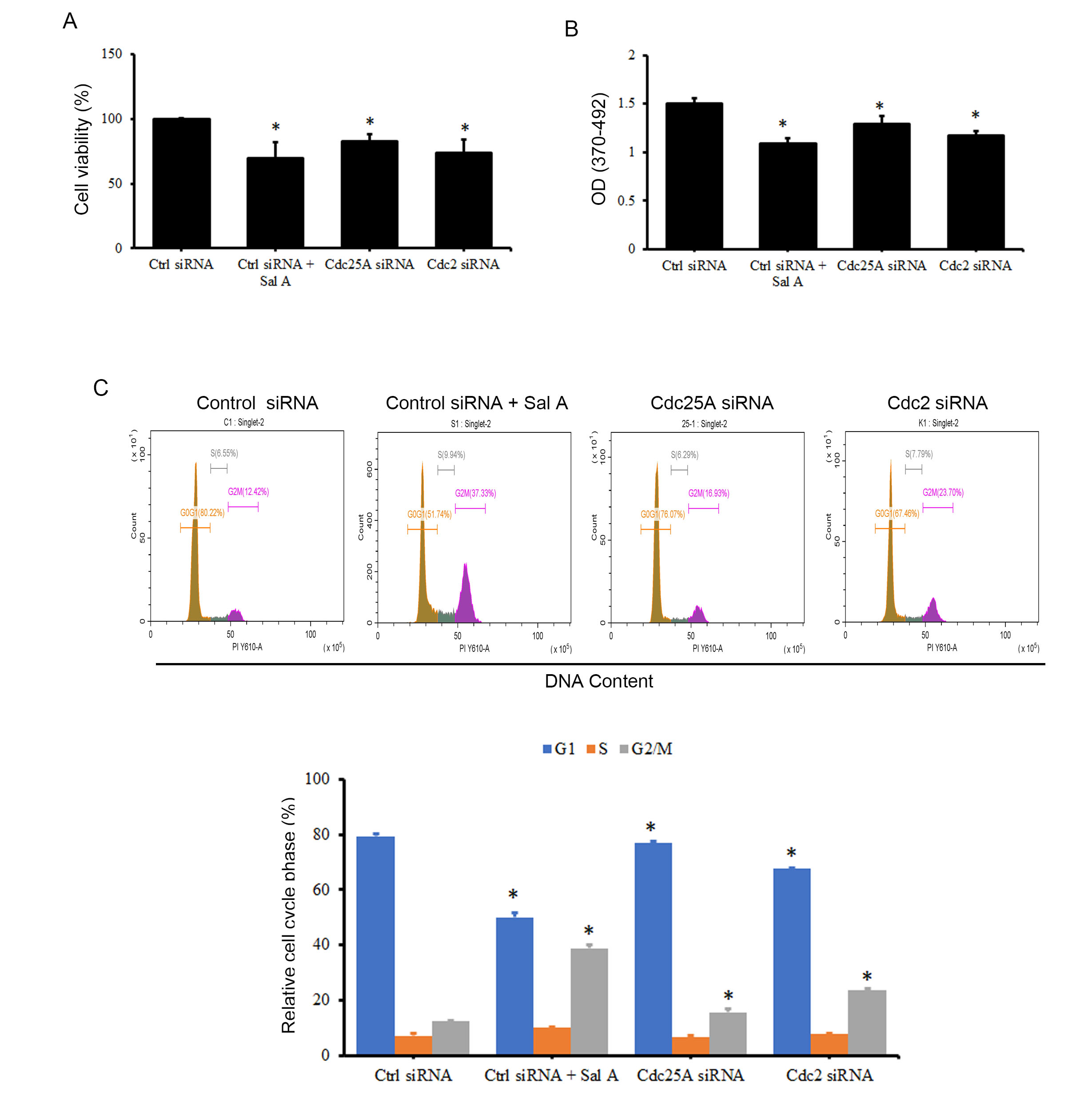

The effect of Sal A, an inhibitory compound, on cell viability and proliferation in melanoma cancer cells was explored by investigating its impact on the degradation of Cdc25A and Cdc2 via the Chk2 pathway. Additionally, the direct influence of Cdc25A and Cdc2 degradation on cell growth was examined. To achieve this, A2058 cells were transfected with Cdc25A or Cdc2 siRNA, resulting in a decrease in cell viability by 17.2% and 26.1%, respectively (Fig. 6A). Moreover, cell proliferation was reduced by 13.9% and 21.7%, respectively (Fig. 6B). Similar trends were observed in A375 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, the impact of inhibiting Cdc25A and Cdc2 on cell cycle progression was investigated. The results suggest that although the effect on cell cycle arrest is not as prominent as that seen with Sal A treatment, inhibiting the expression of either Cdc25A or Cdc2 significantly induces cell arrest in the G2/M phase (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.The effects of Cdc25A and Cdc2 siRNA on the cell cycle of A2058

cells. A2058 cells were transfected with Cdc25A or Cdc2 siRNA for 48 h, and cell

viability (A), cell proliferation (B), and the influence on the cell cycle (C)

were measured using WST-1, BrdU incorporation assay, and PI staining,

respectively. *p

The aforementioned cell line studies indicated that Sal A inhibits the growth of melanoma cancer cells through the Chk-2 pathway. Therefore, we further investigated the activation status of Chk-2 during melanoma cancerization by analyzing Cdc25A and Cdc2 expression. Analysis results from purchased melanoma cancer tissue arrays indicate no significant difference compared with normal cells despite an increasing trend in intracellular Cdc25A and Cdc2 expression in cancer tissues (Supplementary Fig. 5).

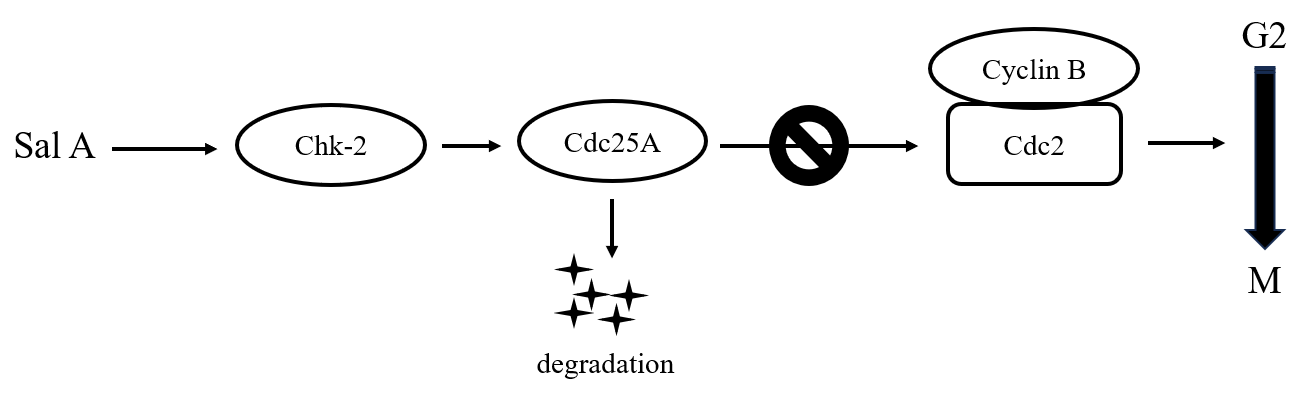

The oncological potential of Danshen is well documented, with ongoing research focusing on its bioactive constituents and their mechanistic pathways in cellular signaling gaining prominence. Existing literature posits that Sal A and B demonstrate comparable bioactivities [16], while our results distinctly reveal that only Sal A hampers melanoma cell proliferation. Our data confirm that Sal A induces Chk-2 phosphorylation within the cell, subsequently activating its downstream signaling cascade. Consequently, this molecular pathway leads to the degradation of Cdc25A and Cdc2, resulting in cell cycle arrest, specifically at the G2/M transition phase (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.Schematic representation of Sal A’s regulation of Chk-2 protein leading to melanoma cell cycle arrest in the G2 phase.

Salvianolic acids, which are key constituents of Danshen, have been reported to display anti-inflammatory activity and anticancer properties. Notably, Sal A and B are recognized for inducing apoptosis in breast and colon cancer cells via Bcl-2 suppression and caspase activation [24, 25]. Additionally, they have been observed to thwart cell proliferation and invasion by inhibiting AKT and MAPK phosphorylation [26, 27, 28, 29]. Contrary to these findings, our study found no substantial alteration in AKT and MAPK phosphorylation in melanoma cells treated with Sal A compared with controls. This indicates that these proteins do not mediate Sal A, which exerts antiproliferative effects on melanoma cells. Our results reveal that Sal A modulates cell growth through distinct molecular targets across various cell types, with Chk-2 emerging as a significant regulator of melanoma cell growth inhibition.

DNA integrity disruption causes cell cycle arrest, with the G1 and G2 checkpoints serving as pivotal junctures. Aberrations in DNA damage response mechanisms are often indicators of genomic instability, which is a contributing factor in melanoma pathogenesis [30]. Such defects in cell cycle checkpoints frequently correlate with N-RAS or B-RAF oncogene mutations in melanoma [31, 32]. Notably, the A2058 and A375 melanoma cell lines both demonstrate constitutive B-RAF signaling activation due to the prevalent B-RAF V600E mutation, with A2058 particularly showing pronounced impairments at the G2 checkpoint [33]. Hence, therapeutic intervention by Sal A could orchestrate G2 checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest via an alternative pathway, particularly in melanoma cells with compromised DNA damage responses stemming from aberrant RAS signaling.

Contemporary research has broadened to include the role of the RAS signaling pathway in melanoma progression, indicating a significant proportion of approximately 22% of melanoma cell lines that exhibit genetic deletions in critical regulators such as Chk-2, Apaf1, and Rb1 [34]. Clinical studies have investigated Chk-2 gene variants, revealing an association with heightened melanoma susceptibility. The Chk-2*1100delC mutation, in particular, has been related to doubling the risk of melanoma [35, 36]. In this study, phosphorylated protein expression arrays indicated that Sal A induces Chk-2 phosphorylation, demonstrating its constrained effectiveness in melanoma variants with Chk-2 alterations. The limitations of this study are partly rooted in the unavailability of specific data on melanoma tissues within The Cancer Genome Atlas database, which restricts our ability to definitively identify the activation status of Chk-2-regulated downstream genes during melanoma carcinogenesis. These observations did not achieve statistical significance despite tissue array analyses showing a trend toward increased expression of genes, such as Cdc25A and Cdc2, in melanoma cells. This gap in these data highlights the imperative need for comprehensive genetic screening to detect gene variations associated with melanoma. Such screenings are crucial for improving our understanding of melanoma pathogenesis and for developing more targeted and effective therapeutic strategies. Recognizing this limitation highlights the necessity for future studies to focus on the genetic underpinnings of melanoma, thereby contributing to the enhancement of treatment modalities.

Sal A is structurally analogous to Danshensu and can be derived by adding ortho-vanillin to Danshensu [37]. The anticancer properties of Danshensu were extensively documented despite a limited focus on melanoma. Danshensu does not reduce the proliferation of B16F10 melanoma cells; however, it inhibits VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 secretion, thereby attenuating cellular invasiveness [15]. These results reveal that Danshensu’s influence on melanoma may be independent of cell proliferation, indicating a divergent mechanism from Sal A’s regulation of the G2 checkpoint in the cell cycle. The potential parallelism between Sal A and Danshensu in impeding melanoma cell invasion warrants further investigation.

Sal A and B constitute primary salvianolic acid derivatives from Danshen, with Sal A uniquely demonstrating melanoma growth inhibition properties. Furthermore, the Chk2-Cdc25A-Cdc2 signaling pathway plays a role in the G2 checkpoint regulation of the melanoma cell cycle induced by Sal A. The results of this study define the pathways involved in the anticancer efficacy of Danshen and suggest Sal A as a therapeutic agent for melanoma.

The data used to support the findings of this study have been included in this article.

CYK and YM designed the research study. XYP and ZQ performed the research. XYP and YM analyzed the data. CYK and YM wrote the manuscript. CYK and YM got funding acquisition. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments on a draft of the paper.

This research was funded by the Startup Fund for Scientific research of Fujian Medical University (Grant No. 2020QH1112).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.