1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a pathological condition that occurs when the

structure and function of the kidney changes, which in turn can lead to

complications, such as hypertension, edema, and oliguria, as well as high levels

of serum creatinine or blood urea nitrogen [1]. Kidney fibrosis (KF), the most

prevalent histological hallmark of CKD, is a condition marked by an increased

deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the interstitium. KF disrupts kidney

architecture and exacerbates kidney dysfunction [2]. Nowadays, it is widely

accepted that KF involves an epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) of renal

tubular epithelial cells prompted by abnormal activation of myofibroblasts and

subsequent ECM deposition. Transforming growth factor (TGF-)

regulates the most important processes of this complex mechanism. The first phase

of EMT is characterized by both the loss of stability of the various cell–cell

contacts and the disruption of apical–basal polarity. This destabilization is

caused by stimulating tubular epithelial cells through cytokines, such as the

epidermal growth factor (EGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2), and

TGF-1. These cytokines are secreted mainly by infiltrating mononuclear

cells, partially reducing epithelial membrane junctions and tight junction

proteins, such as E-cadherin and zonula occludens. In the intermediate phase,

there is a shift towards the expression of new mesenchymal proteins, including

-smooth muscle actin (-SMA) and fibroblast-specific protein 1

(FSP-1) synthesis. In this stage, there is a protein reorganization of the

cytoskeleton and an upregulation of both matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and

MMP-9) and enlarged spindle-shaped myofibroblasts, which show increased capacity

for cell migration and invasion into the tubular interstitium. The observation

that epithelial markers are expressed in interstitial cells in biopsies from End

Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) patients suggests that EMT is involved in KF. The

detection of FSP-1 in the tubular epithelium is another sign of EMT [3]. In human

biopsy samples, there is a correlation between tubular cells presenting EMT

markers, the appearance of interstitial fibrosis, and functional involvement [4].

However, there is a lack of support from in vivo cell-fate tracking

experiments in showing the direct involvement of EMT in contributing to the

myofibroblast population [5]. Recent studies have shown that a partial EMT

(pEMT—wherein tubular epithelial cells acquire one or two phenotypic markers

without leaving the local microenvironment) was induced by Snail1 or Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1) in

tubular epithelial cells, leading to the onset of fibrosis. Consistent with this,

pEMT has been observed in clinical samples and was found to correlate with the

progression of fibrosis in renal allografts [5]. Inflammatory processes,

beginning with the infiltration and activation of macrophages, are considered to

be major factors leading to fibrotic diseases [6]. The recruitment of macrophages

in the glomerular or tubular interstitium is necessary to promote innate immune

responses and important defensive and disruptive reactions in renal disease. The

subsequent macrophage infiltration leads to kidney structure disruption and

tissue fibrosis development. Glomerular and interstitial macrophages, although

believed to be associated with the development of interstitial fibrosis, play an

important role in stromal remodeling during tissue repair [7, 8]. In addition to

releasing inflammatory cytokines, activated macrophages also secrete matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs), including high levels of MMP-1, -3, -7, -9, -10, -12,

-14, and -25, along with lower levels of MMP-2, -3, -8, -10, -11, and -12 [9]. An

inflammatory injury in the kidney is also the result of these MMPs contributing

to the degradation of the extracellular matrix [10]. The profibrotic changes in

tubular epithelial cells [11] and the proteolytic activation of osteopontin in

kidney fibrosis led to macrophage recruitment, indicating that MMP-9 causes

fibrosis [12].

2. Matrix Metalloproteinases

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent endopeptidase enzymes. They

function to remodel the ECM and are fundamental to tissue development and

homeostasis. Previously, MMPs have been considered to have a negative impact on

human health; today, their role in physiology and general health is being

progressively clarified [11, 12, 13]. In fact, MMPs regulate many physiological

processes. These include angiogenesis, embryogenesis, morphogenesis, and wound

healing, although they may also induce various pathological conditions, similar

to myocardial infarction, fibrotic diseases, osteoarthritis, and cancer.

Some studies demonstrated that specific increases in MMP could play a role in

arterial remodeling, aneurysm conformation, venous dilatation, and pulmonary

embolism diseases [14, 15]. Many MMPs are secreted as pro-MMPs, requiring activation through

prodomain cleavage, typically by plasmin or other MMPs. Indeed, 24 MMP

genes have been identified in the human genome. Notably, MMP-23A is a

duplicated version of MMP-23B and is likely a pseudogene [16, 17]. Each

MMP contains the following components: (1) an N-terminal signal peptide that

directs the enzyme to the secretory pathway and (2) a prodomain with a conserved

PRCGXPD sequence responsible for the latency of the enzyme bound to a conserved

HEXGHXXGXXH motif [18]. Four twisted -sheets are present in the

hemopexin-like domain’s ‘propeller’, allowing substrate recognition [14]

Together, the hinge region and the hemopexin-like domain break down substrate

proteins for further degradation. The C-terminal domain interacts with Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) and

participates in substrate recognition [19]. MMPs are also able to cleave a range

of non-ECM substrates, such as cell adhesion molecules (cadherins and integrins),

as well as growth factors and their receptors (TGF-), fibroblast growth

factor receptor 1 (FGF-R1) [20]. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

or TIMPs, which have been identified in vertebrates, control the activities of

MMPs. There are four TIMP members, TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4, that inhibit all MMPs,

except for TIMP-1, which does not inhibit MMP-14, -16, or -24 [21]. TIMPs can

induce intracellular signaling such as proliferation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis

[22]. Based on substrate and sequence homology, MMPs are classified into six

distinct groups: collagenases (MMP-1, -8, -13, -18), gelatinases (MMP-2, -9),

stromelysins (MMP-3, -10, -11), matrilysins (MMP-7, -26), membrane-bound matrix

MMPs (MMP-14, -15, -16, -17, -24, -25), and the “other MMPs” (MMP-12, -19, -21,

-23a, -23b, -28) [21]. TIMPs are also classified numerically from TIMP-1 to

TIMP-4 [23]. Gelatinases are responsible for cleaving and further degrading

triple-helical fibrillar collagens. They also degrade basement membrane

constituents; for example, MMP-2 (but not MMP-9) can degrade laminin and

fibronectin [24]. Stromelysins degrade extracellular matrix proteins but not

triple-helical fibrillar collagens. Membrane-bound MMPs activate many proteases

and growth factors. All TIMP molecules have 190 amino acids, which are folded

into two distinct domains. These domains comprise a larger N-terminal domain

(approximately 125 amino acid residues) and a smaller C-terminal domain. Three

conserved disulfide bonds stabilize each domain. The N-terminal domain alone can

fold individually and is fully functional for MMP inhibition. While the function

of the C-terminal domain is not fully understood, it has been shown to tightly

bind to the hemopexin domain of latent MMPs [20]. Regulation of MMP activity may

occur through several mechanisms: (1) gene expression, by both transcriptional

and posttranscriptional modifications; (2) compartmentalization that occurs by

incorporating cell-specific and tissue-specific release of extracellular MMPs; or

(3) through the zymogen activation of the pro-enzyme forms of MMPs achieved by

the removal of the 80–84 residue terminal domain; (4) inhibition by TIMPs. While

TIMPs 1–4 all share some sequence similarity, TIMPs 2, 3, and 4 are more

identical than TIMP-1. Furthermore, TIMP-2 is unique in that it can both inhibit

and activate MMPs [25]. All TIMPs inhibit the pro- and active forms of the MMPs,

although with relatively low selectivity, and with which they form tight

non-covalent complexes. TIMP-1 has shown low inhibitory activity against MMP-19

and membrane-bound MMP-14, -16, and -24 while displaying greater potency against

MMP-3 and MMP-7 than TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 [26]. TIMP-2 has an effective inhibitory

activity against all MMPs. Similarly, TIMP-3 inhibits all MMP members while

extending its inhibitory profile to include members of the ADAMs (a disintegrin

and metalloprotease) family of metalloproteinases. MMP-1, -2, -3, -9, -11, -13,

-14, -24, -25, -27, -28 and TIMP-1, -2, -3, -4 are expressed in the kidney [27].

The distribution of MMPs and TIMPs in human kidney tissue and their localization

at the subcellular level and immunohistochemical study are available at

https://www.proteinatlas.org/[28].

Matrix Metalloproteinases in Kidney Fibrosis

The accumulation of proteins in the extracellular matrix and an increased

activity of myofibroblasts cause the development and progression of renal

fibrosis. In this process, MMPs and TIMPs play a very important role, and this is

demonstrated, for example, by the role that MMP-2 and MMP-9 play in particular.

The latter causes the EMT of tubular cells. It favors the activation of resident

fibroblasts, endothelial–mesenchymal transition (EndoMT), and

pericyte–myofibroblast transdifferentiation [29]. Many cells, including

mesangial, endothelial, epithelial, collecting duct tubular cells, macrophages,

and fibroblasts, express MMP-2 and MMP-9, which could directly induce the entire

course of renal tubular cell EMT, as demonstrated by in vitro studies

[30, 31]. MMPs are usually responsible for the degradation of mature ECM proteins,

such as collagens and fibronectin. TIMPs decrease MMP activity and reduce ECM

degradation rates. The accumulation of collagen types I, III, and IV in the

glomeruli, interstitial tissue, and vessels causes progressive renal scarring.

TGF-1 induces increased MMP-9 expression and decreased TIMP-1

expression, altering ECM homeostasis and leading to kidney fibrosis. This process

has been recognized as an essential component of EMT activation and permits the

migration and invasion of newly transformed mesenchymal cells in the interstitial

space, resulting in fibrosis progression through extracellular matrix deposition

[32]. However, it should be noted that some investigators have reported an

increased expression of TIMP-1 by TGF-1. One study observed the

induction of TIMP-1 by TGF-1 via the proximal promoter activator protein

1 (AP1) site while having the opposite effect on MMP-1 expression [33]. Another

study investigating animal models of intestinal fibrosis observed increased

phosphorylation of Smad-2 and Smad-3 proteins upon treatment of myofibroblasts

with TGF-1 and increased TIMP-1 levels [34]. Akool et al. [35]

also noted TIMP-1 expression induced by nitric oxide (NO) in mesangial cells—NO

exerted this effect through the TGF-1/Smad-2 signaling pathway. Yang and

co-workers underlined the importance of MMPs in disrupting the tubular basement

membrane and demonstrated that the tubular basement membrane integrity was

preserved due to the indirect reduction of MMP-9 activity in mice with

tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) deficiency. This reduction caused a

decrease in tubular cell EMT and kidney fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy.

Furthermore, Fernandez-Patron and Leung [29] reported that MMP-2 could

reduce inflammation because it antagonizes phospholipase A2 (PLA2). Additionally,

MMP-2 may facilitate the activation of the MMP-1, MMP-9, and MMP-13 zymogens.

MMP-2 performs many pathophysiological functions, creating a close association

between fibrosis and inflammation. In fact, many studies report that it is

produced in many nephron sites (such as the glomerular mesangial cells, renal

tubular epithelial cells, and interstitial cells) and can play different roles

during the progression of CKD. The rapid progression of CKD is also due to the

ability of MMP-2 to degrade the basement membrane, alter the glomerular

filtration membrane, activate TGF-1, and promote the phenotypic

transformation of tubular epithelial cells [36]. Deficient MMP-2 activity leads

to renal tubular atrophy, fibrosis, and excessive ECM deposition in the basement

membrane and interstitium, a sign of advanced chronic kidney disease. This not

only contributes to ECM degradation and the development of chronic inflammation

but also leads to insufficient degradation of endothelin-1, adrenomedullin, and

calcitonin gene-related peptides by MMP-2, exacerbating the intrarenal arteriolar

spasms and sclerosis [30]. MMP-7 may also contribute to renal fibrosis mainly

through EMT transition, TGF- signaling, and ECM accumulation [31]. MMP-7

mediates EMT through three distinct pathways: Through the first mechanism, MMP-7

causes ECM destruction by cleaving collagen type IV and laminin. Secondly, MMP-7

mediates E-cadherin degradation, leading to a disruption of tubular epithelial

integrity. The last process induces the expression of the Fas ligand (FasL) in

interstitial fibroblasts, leading to apoptosis [31]. MMP-7 expression in

the kidney is also upregulated by age, and its level correlates with renal

healing [37]. The thickening of the basement membrane and mesangial expansion

precede the onset of renal scarring and are favored by MMP-7. The latter also

enzymatically cleaves numerous extracellular matrix proteins such as type IV

collagen, laminin, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and entactin. Interestingly, in a

rat model of age-associated renal interstitial fibrosis, MMP-7 expression is

significantly elevated in fibrotic samples, whereas non-fibrotic samples do not

show this expression profile. Furthermore, the expression of MMP-7 strongly

correlates with the fibrosis degree [38].

Zhang et al. [39] investigated the role of TIMP-1 in fibrosis using a

transgenic TIMP-1 mouse model and observed that intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression was increased

in these mice partly due to MMP-9 inhibition. They also noted that the increase

in ICAM-1 level led to increased renal macrophage infiltration, kidney collagen

levels, and renal fibrosis, which correlated with the age of the transgenic

animal. Zhang et al. [39] suggested that an imbalance between TIMPs/MMPs

and inflammation could lead to fibrosis. A recent study utilizing TGF-1

transgenic mice also demonstrated that renal fibrosis was correlated with TIMP-1

expression, and using an anti-TIMP1 neutralizing antibody ameliorated

glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis [40]. They also observed

increased TIMP1 levels in human kidneys with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis,

suggesting a correlation between TIMP-1 and fibrosis. Other groups have also

noted a correlation between TIMP-1 and renal fibrosis: Increased expression of

TIMP-1 mRNAs in glomerular resident cells and tubular epithelial cells have been

associated with interstitial injury [41]; a reduction in TIMP-1 mRNA levels was

associated with improved symptoms of nephritis in a murine model of lupus

nephritis [42]; decrease in TIMP-1 expression was also accompanied by a reduction

in renal collagen expression and glomerulosclerosis in diabetic rats treated with

the soluble guanylate cyclase activator cinaciguat [43].

3. MMP Gene Polymorphisms and Kidney Disease

Gene polymorphisms can influence both the expression and activity of MMP-9. Two

functional polymorphisms affecting the transcriptional activity of the

MMP-9 gene were identified in the promoter region, namely the

C-1562T (rs3918242) and microsatellite (CA) (rs3222264) polymorphisms [44]. In particular, the microsatellite

(CA)n region located near the -90 positions functions as a binding site

for a specific DNA regulatory protein and also promotes the unwinding of the DNA

helix and the transcription process by allowing the DNA to adopt a Z structure.

The longest repeat alleles of the microsatellite were correlated with the highest

activity, as demonstrated in vitro. The single nucleotide polymorphism

C-1562T prevents the nuclear repressor protein from binding to the

MMP-9 gene promoter region, resulting in increased MMP-9 expression, as

observed in some in vitro studies [45, 46]. A large Japanese cohort study

has highlighted that the MMP-9-1562T/279R/668Q haplotype reduced the

risk of CKD compared with the MMP-9-1562C/279R/668R. Furthermore, the

MMP-9-1562TT/279RR/668QQ genotype combination has been linked to a

decreased CKD risk compared with the major combination of homozygous allele

MMP-9 -1562CC/279RR/668RR. The association of these genotypes supports

the idea that they play a protective role in kidney disease and could cause an

increase in MMP-9 expression [47]. Earlier studies have also shown that the

CC genotype for the -1562 C/T (rs3918242) polymorphism in the

promoter region causes a significant increase in serum MMP-9 in hemodialysis (HD)

patients compared with the CT genotype [48]. Conversely, in

nephrolithiasis, the -1562 TT (rs3918242) genotype, but not the

Q279R (rs17576) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the

MMP-9 gene, was associated with a higher risk of lithiasis [49]. It has

been shown, in a 3-year study of HD patients, that the 2G/2G homozygous

genotype for MMP-1 was associated with increased mortality in contrast to the

6A/6A homozygous genotype for MMP-3 in the same population [48]. These

findings suggest that investigating the genetic polymorphisms in MMP genes might

help identify high-risk populations that can benefit from a targeted treatment

approach.

4. MMP-9 Signaling

Identifying the molecular components involved in the signal transduction

pathways activated by MMPs may allow interventions to be developed by modifying

their activity. However, there have only been a few studies investigating the

signaling pathways involved in the cellular actions of MMP-9, with several

molecules identified as playing a role in MMP-9 signaling, as discussed in the

following subsections.

4.1 p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and NF-kB

In addition to its proteolytic action on the ECM, MMP-9 activates

interleukin-1 [50] and plays a role in cell signaling. Notably, a study

by Al-Sadi et al. [51] reported that MMP-9, at clinically relevant

concentrations, rapidly upregulated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)

levels in Caco-2 cells. This, in turn, led to an increase in myosin light-chain

kinase gene and protein levels. However, no details on the mechanism through

which MMP-9 caused activation of the MAPK were given. Furthermore, it was noted

that MMP-9 did not activate the extracellular-signal-regulated protein kinases

(ERK)1/2 and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) members of the MAPK family [51]. In a

subsequent report, the same authors observed that p38 activation led to the

activation and subsequent nuclear translocation of the proinflammatory

transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-B) [52]. Notably, the

p38 isoform may regulate MMP-9 expression [53]. While these studies

were conducted in non-renal cells, it is possible that MMP-9 could have similar

effects in renal cells. In such a scenario, the p38/NF-B axis would

lead to inflammation and increase MMP-9 levels, creating a positive feedback loop

that could intensify the inflammatory milieu.

4.2 Collagen Degradation Products

MMP-9 action on the ECM leads to the production of collagen fragments, such as

the tripeptide N-acetyl Pro–Gly–Pro (Ac-PGP), a neutrophil chemoattractant

[54]. AcPGP also binds to neutrophils to induce further production of MMP-9

via an ERK1/2–MAPK-dependent pathway [22], creating a positive feedback

loop. AcPGP binding appears to be on the CXC motif chemokine receptor 1 and CXC

motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR1 and CXCR2) receptors on neutrophils and may

interact with these receptors wherever they are present in other cells, including

renal cells [55].

4.3 Notch Signaling

Zhao et al. [56] reported the induction of Endo-MT in human kidney

glomerular endothelial cells (HKGECs) by recombinant MMP-9 (rMMP-9). It was

observed that rMMP-9 caused a decrease in Notch1 receptor levels while

simultaneously increasing the levels of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD)

[56]. The Notch signaling pathway consists of the Notch receptors together with

several ligands, although in the canonical signaling pathway, Notch is cleaved to

form the NCID, which is then transported to the nucleus to regulate transcription

of its target genes [57]. Zhao et al. [58] also demonstrated that using

a Notch pathway inhibitor, a -secretase inhibitor (GSI), inhibited the

rMMP-9-induced morphological changes and decreased NICD levels in HKGECs. In a

following study performed by the same group, Zhao et al. [58] used

primary mouse renal peritubular endothelial cells (MRPECs) to observe Endo-MT

following induction by MMP-9. Once again, rMMP-9 caused an increase in NICD,

whose levels were decreased by GSI. Furthermore, in MRPECs isolated from MMP-9

knockout (KO) mice and subjected to TGF-1, higher levels of Notch1 and

lower levels of NICD were observed. Finally, Zhao et al. [58] performed

unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) of the kidneys in MMP-9 KO and wild-type

mice to induce fibrosis. Zhao et al. [58] noted that the MMP-9 deficient UUO

kidneys had less fibrosis, and levels of hairy/enhancer-of-split related with

YRPW motif 1 (Hey-1), a downstream target gene in the Notch signaling pathway,

decreased, implicating Notch signaling in the MMP-9 mechanism of action.

Interestingly, it is worth mentioning that a complex interaction between Notch

and NF-B exists, which could activate the NF-B pathway (Fig. 1) [59].

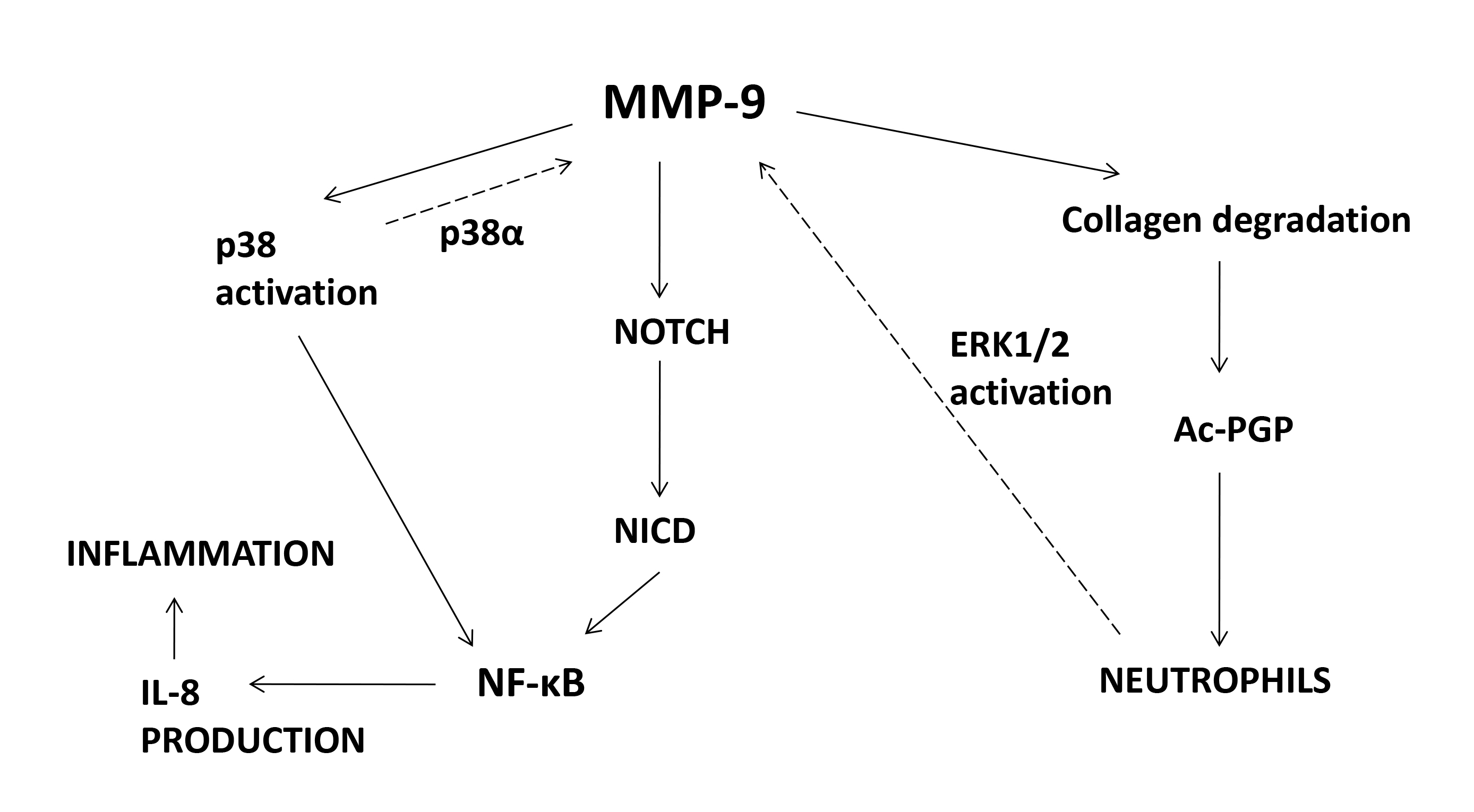

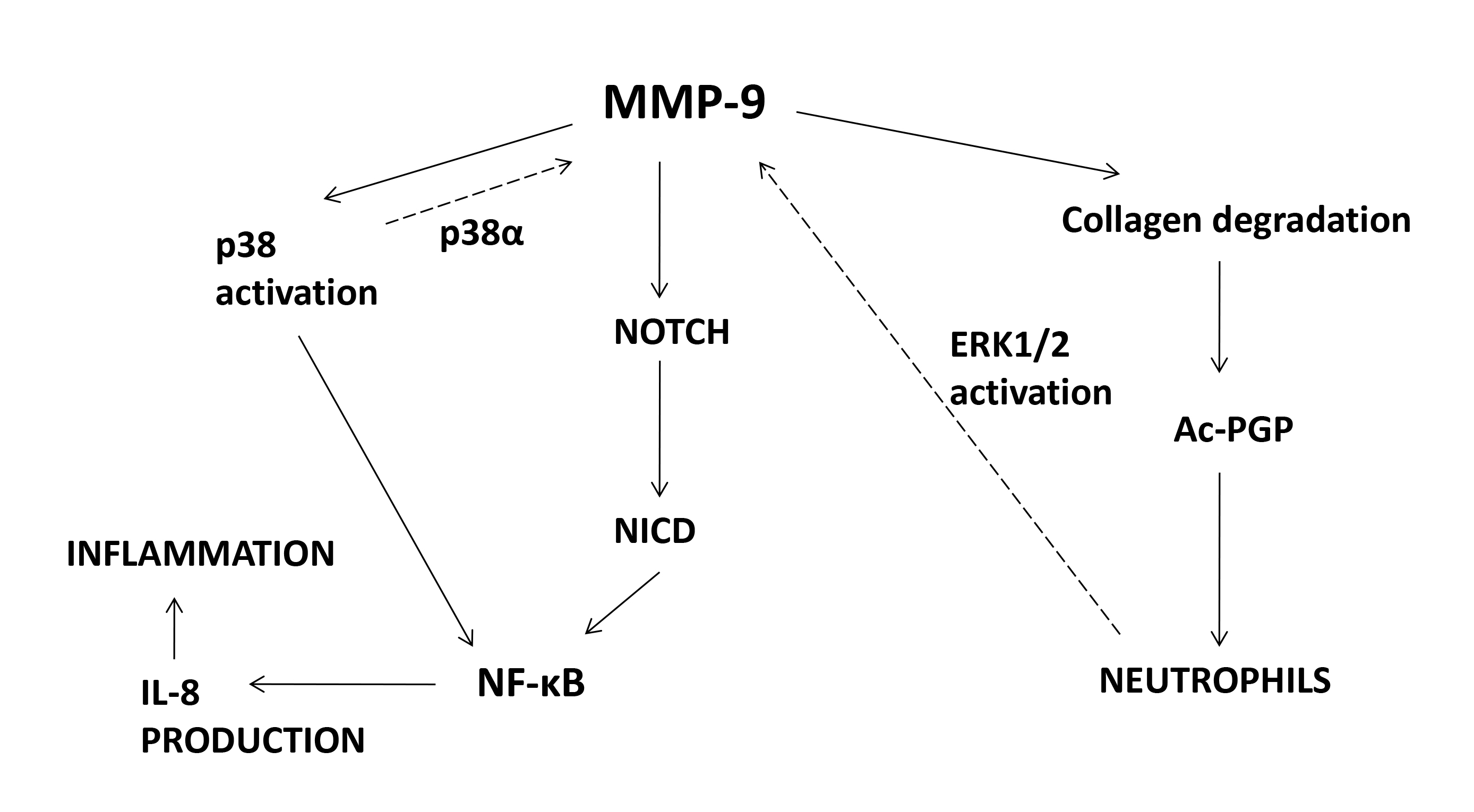

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Signaling molecules affected by MMP-9. MMP-9, matrix

metalloprotease-9; Ac-PGP, N-acetyl–proline–glycine–proline; NICD, Notch

intracellular domain; IL-8, interleukin-8; NF-B, nuclear

factor-B; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2;

p38, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase.

5.MMP-9 as a Promising Therapeutic Target

Several studies have indirectly demonstrated the involvement of MMP-9 in renal

fibrosis through the inhibition of t-PA (as t-PA is an inducer of MMP-9) and

through knockout mice. To determine the role of MMP-9 in vivo, direct

inhibition of MMP-9 activity is the recommended approach [60]. Indeed, a study

[60] has shown that inhibiting the activity of the MMPs early, particularly of

MMPs-2, 3, and 9, seems to protect against Alport’s disease in mice deficient in

the 3(IV) chain of type IV collagen. The study showed that late-stage

inhibition of MMP activity results in more rapid disease progression, which is

associated with interstitial fibrosis and early mortality. Some macrophage

phenotypes may contribute to fibrosis, and evidence suggests that neutralizing

proinflammatory macrophages may prevent renal fibrosis [61]. In vitro

studies have shown that MMP-9 cleaves osteopontin, inducing migration of

macrophages, and that MMP-9 from both tubular epithelial cells (TECs) and

macrophages induces EMT in tubular cells [12]. In the same study, a unilateral

ureteral obstruction murine model of renal fibrosis was used to show that TECs

were the main source of MMP-9 in the early stages of UUO, whereas TECs,

macrophages, and myofibroblasts were the main sources in the later stages. Using

a murine renal tubular epithelial cell line, a study investigated the effects of

incubating these cells in an activated macrophage-conditioned medium (AMCM)

containing MMP-9 secreted by Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages. They noted that the AMCM

could induce EMT in tubular cells, and this effect was inhibited in the presence

of MMP-9 inhibitors and by immunoprecipitation of MMP-9 from the AMCM [11]. A

recent study also demonstrated how diosmin has a potential multicomponent

molecular mechanism of action in treating renal fibrosis. The study indicates

that caspase 3, MMP-9, annexin A5, and heat shock protein 90-alpha family class A

member 1 could be important direct targets of diosmin and that the MAPK, Ras,

phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) Protein kinase B (Akt), FoxO, and hypoxia

inducible factor-1 (HIF) signaling pathways could play a major role in its

mechanism of action. Further studies on diosmin in treating renal fibrosis should

be performed to demonstrate its efficacy [62]. However, as evidence for the role

of MMP-9 in renal fibrosis increases, understanding its secretion, regulation,

and mechanism of action is necessary to develop therapeutics to regulate its

action.

Control of Secretion and Expression

Bellosta et al. [63] reported that the hydroxyl methyl glutaryl

coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor (statin), Fluvastatin, could reduce

MMP-9 activity by up to 50% in human macrophages. Furthermore, they hypothesized

that the statin interfered with the prenylation of small Ras-like guanine

nucleotide-binding proteins (GTPases) that regulate membrane traffic involving

endocytic and exocytic processes, leading to reduced MMP-9 secretion by

macrophages. Other studies have also reported similar effects of various statins

on MMP-9 secretion by different cell types and macrophages [64, 65, 66]. However,

other workers have observed that under certain conditions, some statins may

increase MMP-9 levels in macrophages [67]. Surprisingly, one report attributes

the beneficial effects of a hydrophilic statin, rosuvastatin, on preventing an

increase in MMP-2 and a decrease in MMP-9 in hypertensive stroke-prone rats [68].

Confocal microscopic analysis of kidney sections from Zucker diabetic rat kidneys

showed increased MMP-9 in the glomeruli, particularly in the parietal epithelial

cells (PECs) [69]. Albumin administration of cultured primary PECs resulted in a

dose-dependent increase in MMP-9 in the culture medium, together with increased

phosphorylation (activation) of extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERKs)1/2 of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family. Other kinases

investigated included Akt and p38 MAPK, which showed no increase in their

phosphorylation status. Furthermore, using the inhibitor U0126, which inhibits

the upstream kinases, MAPK kinase1/2 (MEK1/2), of the ERK1/2 kinases, resulted

in lower MMP-9 levels. Many factors positively regulate MMP-9 gene expression

including transcription factors E-26 (Ets), NF-B, polyomavirus

enhancer-binding protein 3 (PEA3), activator protein 1 (AP-1), specificity

protein 1 (Sp-1) and serum amyloid A activating factor (SAF)-1 [70], all of which

may be considered as viable targets for MMP-9 regulation, together with the

signal transduction pathways that modulate their activity. However, more research

must be undertaken to delineate these pathways in renal cells and determine the

conditions under which they are activated.

6. Conclusions

Renal fibrosis is caused by excessive accumulation of the extracellular matrix

(ECM), and its pathogenesis is a progressive process that leads to end-stage

renal disease. The accumulation of ECM and uncontrolled matrix degradation play

an important role, mainly involving MMPs and TIMPs, which are particularly

important in the development and progression of renal glomerulosclerosis and

tubular interstitial fibrosis. MMPs have traditionally been considered

antifibrotic factors due to their proteolytic activity and extracellular matrix

degradation. However, a decrease in MMP proteolytic activity or an increase in

MMP tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) is thought to be responsible for extracellular

matrix accumulation and fibrosis [27]. In particular, in this review, we have

highlighted the important role that MMP-9 plays in up-regulating pathways

involved in renal fibrosis [58]. Therefore, further studies are needed to

demonstrate that inhibition of MMP-9 pathways could represent a therapeutic

strategy for treating renal fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. In addition, it

would be interesting to understand the intracellular signaling pathways involved

in the action of MMPs, particularly the role of MMPs and TIMPs in the kidney, to

elucidate the underlying mechanisms and develop biomarkers and therapeutic

targets for renal fibrosis.

Author Contributions

ALR, RS and MA designed the study. ALR, RS, TF, GCr, AB, GCo, DB, YB, NI, DC, AM

and MA performed the search and analyzed the data. ALR, RS, AM and MA wrote the

manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated

sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the

work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Raffaele Serra is serving as one of

the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Raffaele Serra had

no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to

information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial

process for this article was delegated to Amancio Carnero Moya.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.