1 Department of Ophthalmology, University Medical Center, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, 55131 Mainz, Germany

Abstract

Nitric oxide synthases (NOS) are essential regulators of vascular function, and their role in ocular blood vessels is of paramount importance for maintaining ocular homeostasis. Three isoforms of NOS—endothelial (eNOS), neuronal (nNOS), and inducible (iNOS)—contribute to nitric oxide production in ocular tissues, exerting multifaceted effects on vascular tone, blood flow, and overall ocular homeostasis. Endothelial NOS, primarily located in endothelial cells, is pivotal for mediating vasodilation and regulating blood flow. Neuronal NOS, abundantly found in nerve terminals, contributes to neurotransmitter release and vascular tone modulation in the ocular microvasculature. Inducible NOS, expressed under inflammatory conditions, plays a role in response to pathological stimuli. Understanding the distinctive contributions of these NOS isoforms in retinal blood vessels is vital to unravel the mechanisms underlying various ocular diseases, such diabetic retinopathy. This article delves into the unique contributions of NOS isoforms within the complex vascular network of the retina, elucidating their significance as potential therapeutic targets for addressing pathological conditions.

Keywords

- nitric oxide synthase

- endothelium

- blood vessels

- retina

The retinal circulation is a finely tuned system responsible for delivering

nutrients, oxygen, and maintaining an optimal microenvironment for blood vessels,

neurons and glia [1]. Nitric oxide (NO) is an essential molecule regulating blood

flow and tissue oxygenation by activating soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), and by

controlling mitochondrial O

Three NOS isoforms have been characterized in humans and other mammals; neuronal

(nNOS or NOS1), inducible (iNOS or NOS2), and endothelial (eNOS or NOS3) [6]. In

humans, these isoforms are encoded by three distinct genes situated on

chromosomes 12, 17, and 7, respectively [8]. While nNOS and eNOS are activated by

Ca

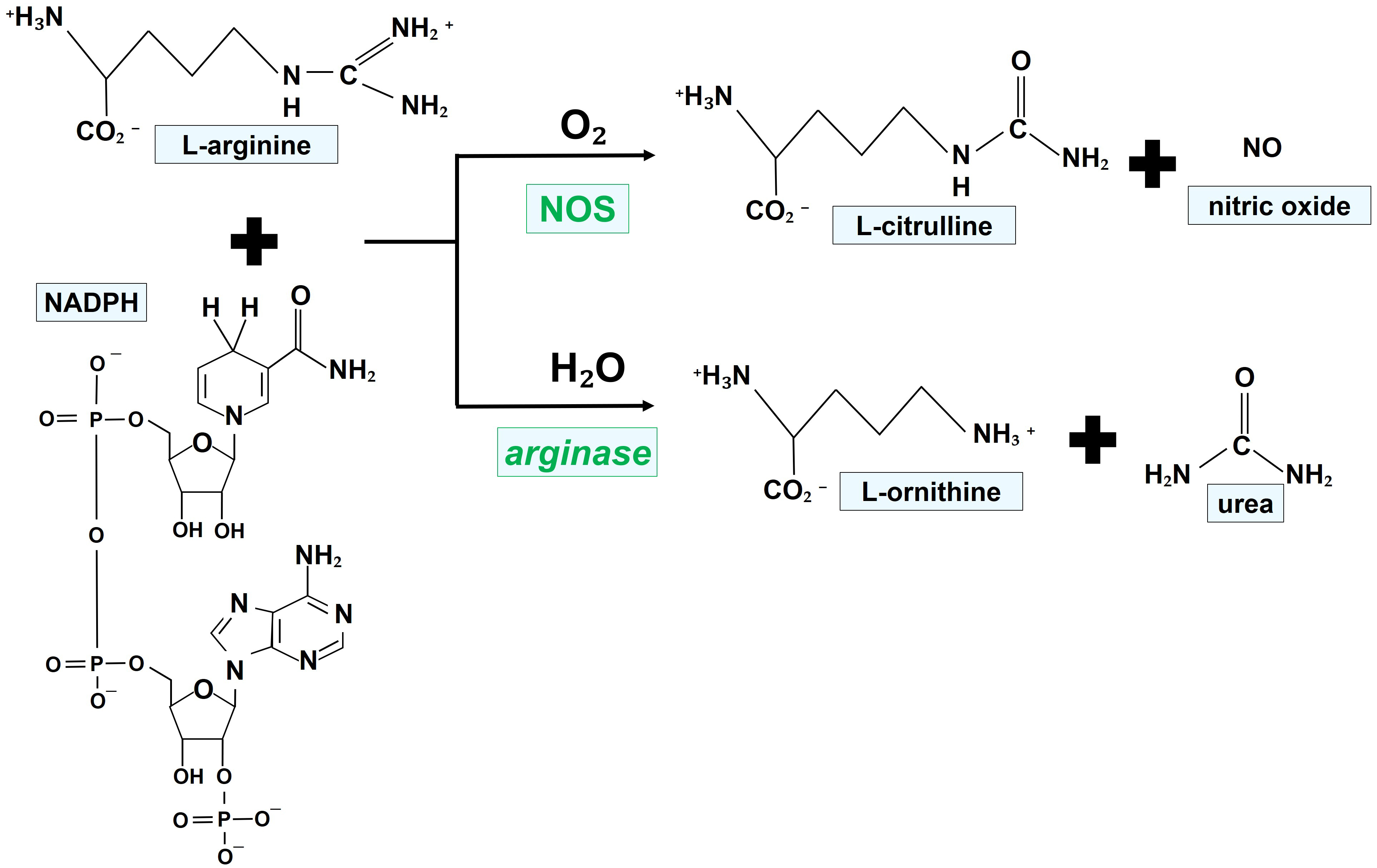

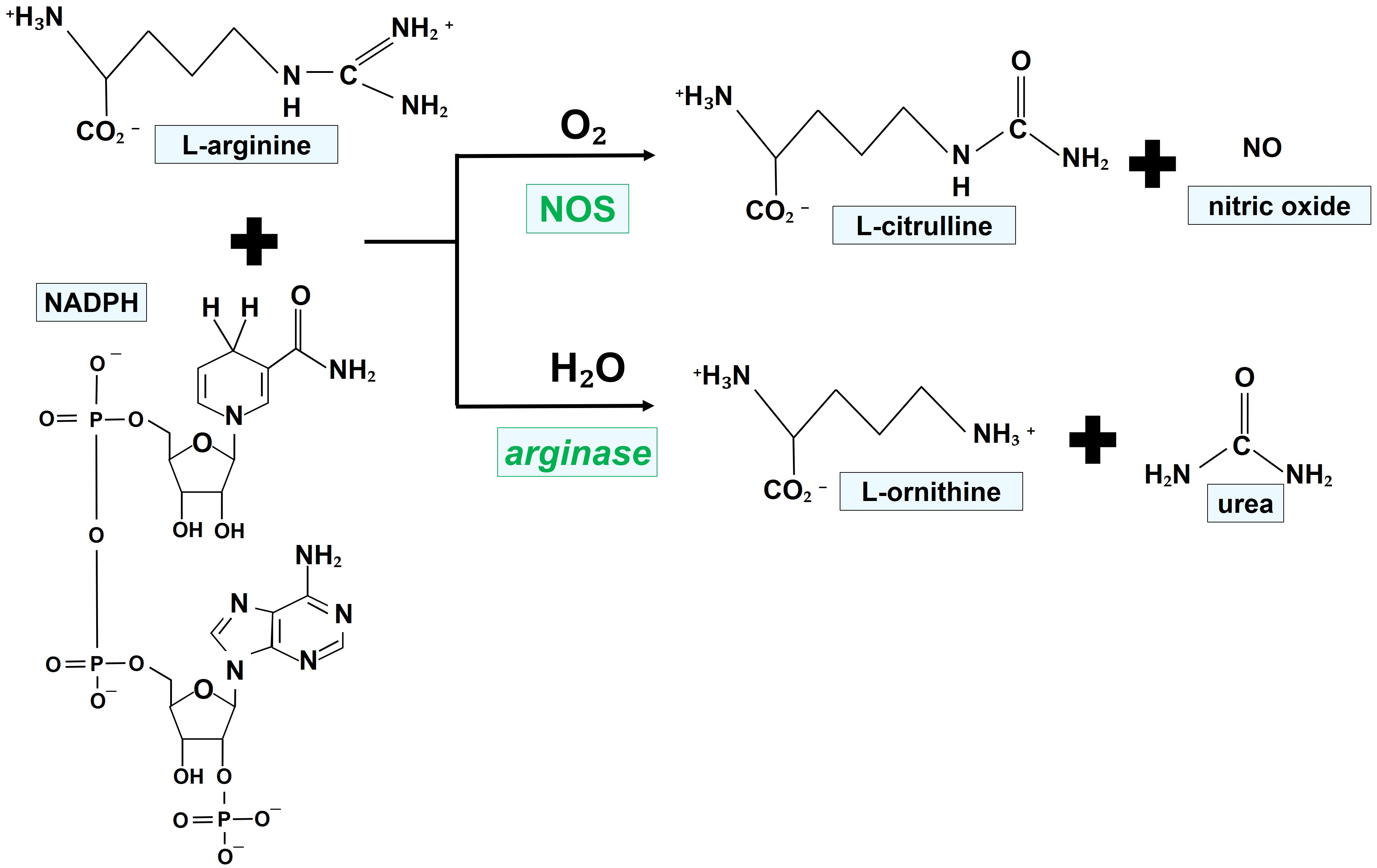

Fig. 1 illustrates the chemical reactions leading to the generation of NO, favored by the enzymatic activity of NOS.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Mechanisms of NO generation by NOS isoforms. NOS oxidize a guanidino nitrogen of L-arginine by using molecular oxygen and NADPH as cosubstrates, resulting in the production of NO. NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase.

The NO/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling pathway stands as one of the most extensively studied pathways, alongside the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathways. This pathway governs numerous physiological parameters including smooth muscle relaxation, neuronal transmission, wound healing, and suppression of platelet aggregation [2]. NO triggers the activation of cytoplasmic sGC, which harbors a heme structure within its binding domain. Upon binding to the heme structure, NO dramatically enhances the enzyme’s catalytic rate by 300-fold [14]. Soluble GC facilitates the conversion of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cGMP, a pivotal regulator of diverse cellular responses such as vascular smooth muscle relaxation [15, 16].

Remarkably, all three NOS isoforms have been identified in retinal blood vessels under physiological conditions. Our previous investigations, conducted on isolated mouse retinal arterioles utilizing real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), demonstrated that messenger RNA (mRNA) for eNOS was the most abundant, whereas that for iNOS was the least prevalent [17]. Similarly, another study identified the expression of eNOS on the protein level in mouse retinal blood vessels [18]. Under physiological conditions, eNOS immunoreactivity was observed in rat retinal vessels but not in neurons [19]. Abundant eNOS mRNA and/or protein expression were also noted in human and bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells, along with pig retinal arterioles [20, 21, 22, 23].

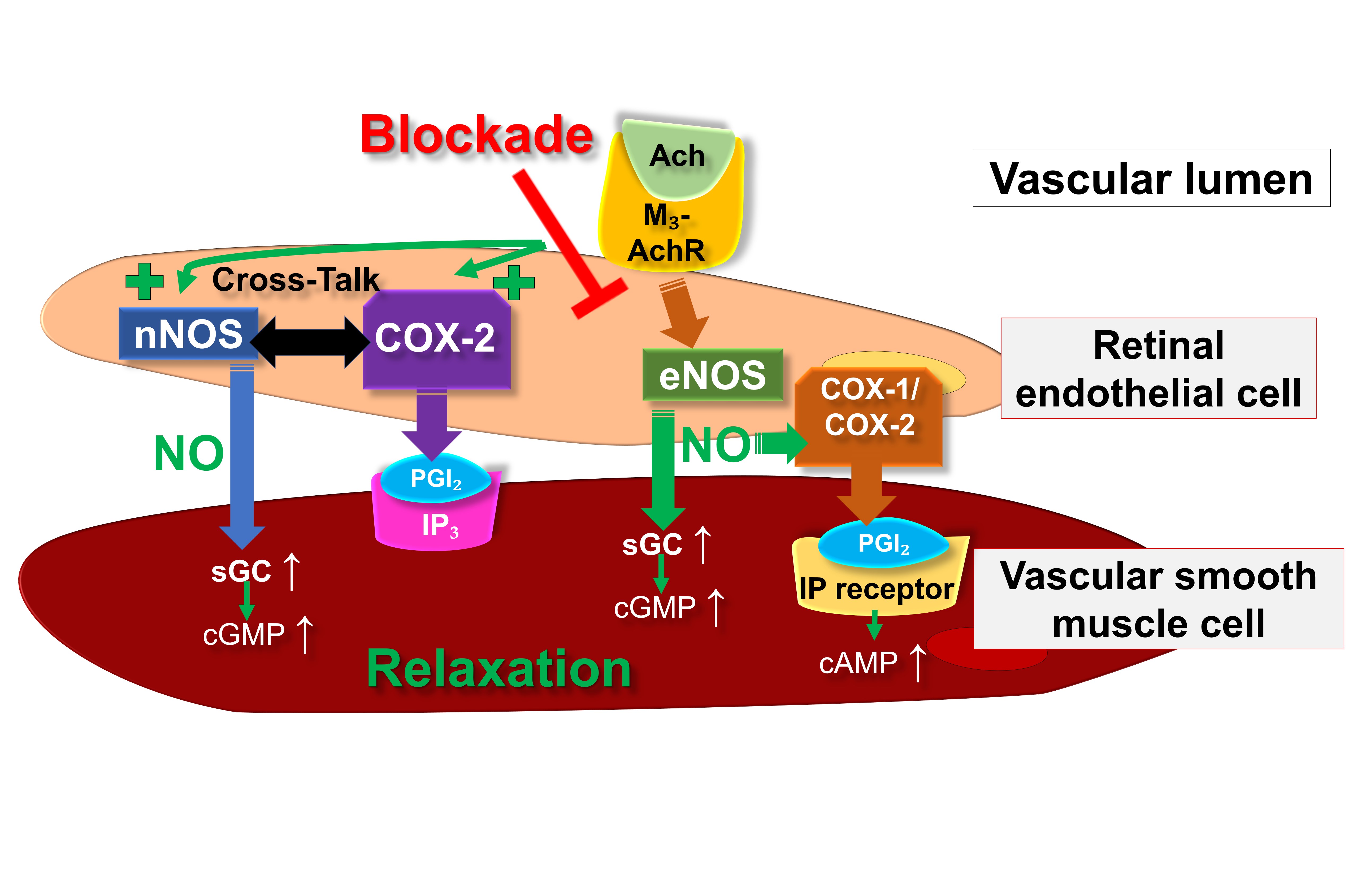

Consistent with these expression studies, experiments utilizing various NOS blockers revealed that endothelium-dependent vasodilatory responses of murine retinal arterioles are primarily driven by eNOS [17]. Supporting this notion, our observations indicated that eNOS-deficient (eNOS–/–) mice exhibited impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatory reactions in arterioles of the retina [24]. Intriguingly, in eNOS–/– mice, endothelium-dependent vasodilation was partially preserved by nNOS and COX-2 metabolites, showcasing reciprocal regulation [24].

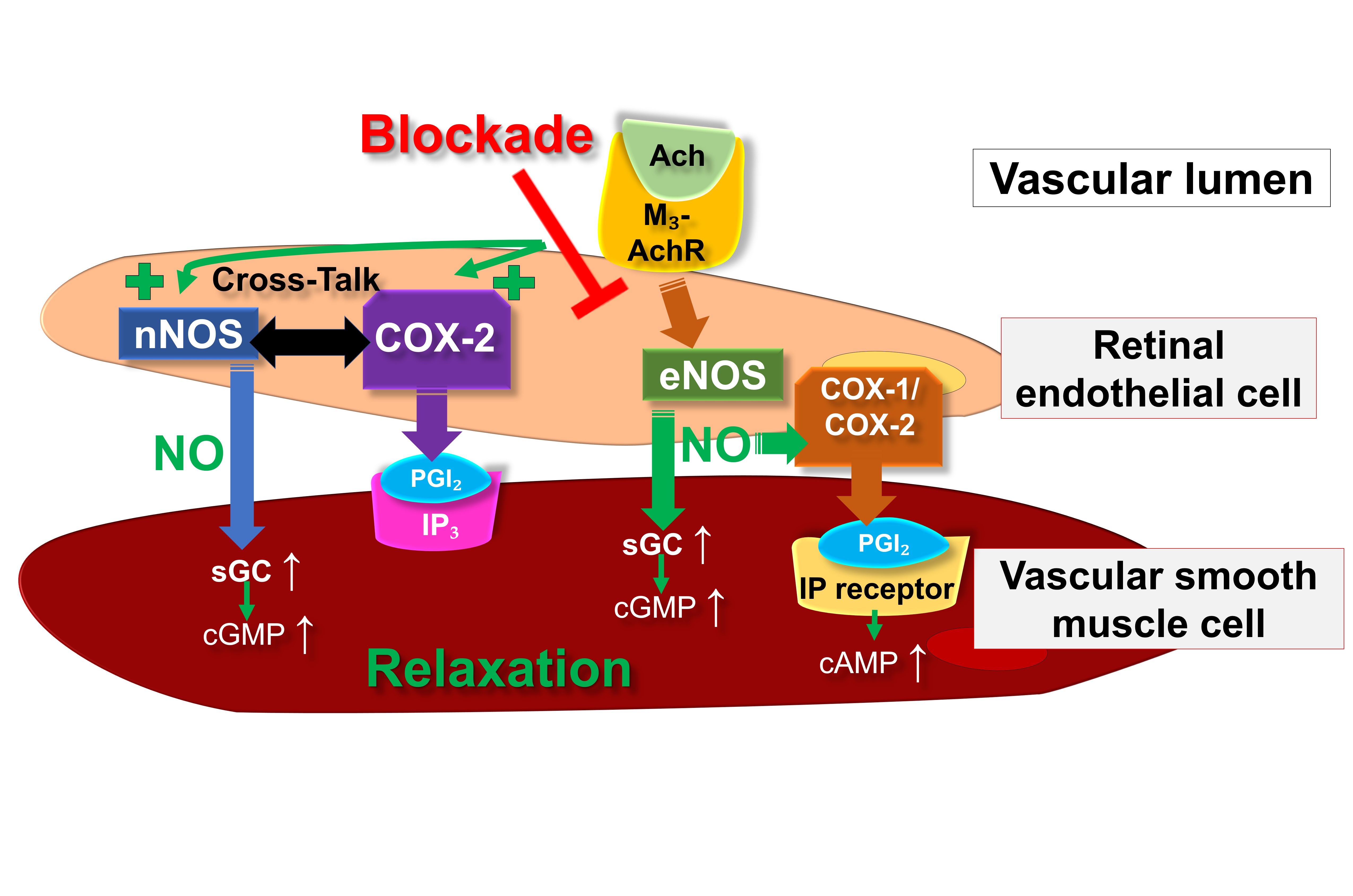

Significantly, certain studies have also indicated the involvement of COX metabolites in endothelium- and NO-dependent vasodilation in ocular blood vessels. For instance, based on an in vitro study, Hardy et al. [25] proposed a NO-mediated activation of endothelial COX-dependent mechanisms in porcine ocular blood vessels. An in vivo investigation conducted on Brown Norway rats concluded that bradykinin-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation in retinal blood vessels involves a COX-2-dependent pathway [26]. However, other in vivo studies on retinal vessels of Wistar rats suggested that NO-related vasodilation is mediated by the COX-1/PGI2/prostanoid IP receptor/cAMP signaling pathway [27, 28]. Additionally, in vitro experiments conducted on human retinal endothelial cells further revealed that the NO donor NOR3 induced the production of PGI2 through the involvement of COX-1 [28]. These results imply that in retinal blood vessels, NO might facilitate vasodilation not only via the sGC/cGMP pathway but also through the involvement of COX-dependent pathways. The predominance of the respective pathway may vary depending on the species or strain.

Fig. 2 provides an overview on the putative endothelial vasodilatory signaling mechanisms in retinal arterioles under physiological conditions as well as during eNOS suppression or dysfunction.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Proposed endothelial vasodilatory mechanisms in mouse

retinal arterioles under physiological conditions and during deficiency of eNOS.

Ach, acetylcholine; COX, cyclooxygenase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase;

IP

Studies conducted on anesthetized cats utilized laser Doppler velocimetry to evaluate retinal blood flow before and after the administration of various NOS inhibitors. The results indicated that eNOS likely participates in the restoration of retinal blood flow following exposure to hyperoxia, while nNOS might contribute to enhancing retinal blood flow during hypercapnia [29, 30]. Experiments conducted on anesthetized rats, involving the administration of two distinct nNOS blockers, 1-(2-trifluoromethylphenyl) imidazole (TRIM) and (4S)-N-(4-amino-5 [aminoethyl] aminopentyl)-N-nitroguanidine (AAAN), suggested that nNOS plays a role in the maintenance of basal vascular tone in the retinal circulatory system [31]. Recent studies have revealed that nNOS-derived NO may be crucial in glial cell-mediated vasodilatory responses in the retina by generating epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and PGE2. Someya et al. [32] demonstrated in rat retinal arterioles that intravitreal administration of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid induced retinal vasodilation, which was attenuated following pharmacological nNOS inhibition. This evidence further suggested that NO stimulates the generation of vasodilatory prostanoids and EETs in glial cells in a ryanodine receptor type 1-dependent manner, ultimately leading to vasodilatory responses in the retina. Subsequently, the same research group proposed that the nNOS-derived NO/PGE2/EP2 receptor cascade, particularly, may be implicated in glia-mediated vasodilation in the retina of rats [33].

Furthermore, another study proposed that iNOS is responsible for cholinergic

vasodilation in the rat retina. This conclusion was drawn from observations where

the iNOS blocker aminoguanidine diminished cholinergic vasodilatory responses

induced by carbachol, possibly mediated via M

Intriguingly, our investigations revealed no discernible loss of neurons in the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) layer of eNOS–/– mice, despite observed impairment in endothelium-dependent vasodilatory reactions in retinal blood vessels [24, 35]. Similarly, no alterations in neuron numbers within the RGC layer were noted in mice lacking nNOS and iNOS, suggesting that the absence of individual NOS isoforms may not exert detrimental effects [35]. Furthermore, retinal vascular development appeared unaffected in eNOS–/– mice, indicating that its absence may not play a critical role in this process or could be compensated for by other NOS isoforms, facilitating regular vascular development [36].

Nitro-oxidative stress, marked by an imbalance between the production of

reactive oxygen species (ROS)/reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and antioxidant

defense mechanisms, emerges as a pivotal pathogenetic factor in various ocular

conditions, including ischemic processes involving neurons and retinal cells

[37]. Among the most detrimental ROS, the superoxide anion

(O

Under conditions of ischemia and oxidative stress, individual NOS isoforms have

been demonstrated to contribute to the onset or progression of diseases. For

instance, eNOS-derived NO has been reported to trigger proangiogenic effects in

the retina under ischemic conditions, partly by promoting upregulation of

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [45, 46]. Conversely, eNOS has

negligible effects on choroidal neovascularization, while iNOS and nNOS play

significant roles [46]. Following transient ocular ischemia in a rat model, eNOS

expression was shown to be increased in retinal vessels and occured de novo in

retinal neurons [19]. Similarly, in an oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) model of

rats, eNOS, but not nNOS or iNOS, exhibited increased activity and expression

during exposure to hyperoxia [47]. In a mouse OIR model, eNOS-derived NO was

reported to destabilize adherens junctions, leading to vascular

hyperpermeability, by interacting with the VEGFA/VEGFR2/c-Src/VE-cadherin pathway

[48]. Another study on OIR in mice demonstrated that hyperoxia reduces the

bioavailability of BH

Further investigations into OIR models have explored the role of iNOS in the retina. Studies conducted by Sennlaub et al. [51] in a murine OIR model demonstrated that both iNOS–/– mice and the inhibitory action of a selective and potent iNOS inhibitor, N-(3-(Aminomethyl)benzyl)acetamidine (1400W), enhanced physiological neovascularization and mitigated pathological intravitreal vessel formation. Additionally, the same research group illustrated in the same mouse model that iNOS expression is linked to retinal degeneration via apoptosis [52]. This is consistent with another study by Wu et al. [53] on transgenic mice overexpressing iNOS, which exhibited oxidative stress-mediated retinal degeneration and apoptosis in the photoreceptor layer of the retina.

During diabetes mellitus, nitro-oxidative stress and hyperglycemia emerge as

relevant pathogenetic factors leading to aberrant structural microvascular

changes in the retina, culminating in diabetic retinopathy (DR) [54]. The

reduction of NO bioavailability and the formation of peroxynitrite result in

protein nitration events, characterized by the generation of nitrotyrosine,

leading to tissue damage and cell injury through lipid peroxidation, protein

inactivation, and DNA damage [55]. Under diabetic conditions, dysfunctional

activity of eNOS, nNOS, and iNOS can lead to retinal injury, leukostasis, and

increased vascular permeability [7]. Importantly, oxidative stress triggers an

event of eNOS uncoupling, wherein the physiological function of eNOS as a

NO-generating enzyme converts to a superoxide producer due to the depletion of

the eNOS cofactor BH

Hence, akin to the pathogenetic events occurring in OIR, eNOS is critically involved in DR. Numerous studies have documented an association between specific eNOS gene polymorphisms and an increased risk of developing DR [61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69]. Laboratory studies have revealed that elevated glucose levels and osmotic stress escalate the generation of nitrotyrosine in bovine retinal endothelial cells, thereby enhancing eNOS activity and inducing superoxide formation due to eNOS uncoupling and activation of aldose reductase [70]. In diabetic rats, VEGF induces retinal eNOS and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression, initiating early diabetic retinal leukocyte adhesion in vivo [71]. Furthermore, high glucose levels promote retinal endothelial cell migration through the activation of Src family kinases, phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/AKT1 kinases/eNOS, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) [72]. In another investigation, diabetic eNOS–/– mice exhibited a broader spectrum of retinal vascular complications, including vessel leakage, gliosis, a heightened count of acellular retinal capillaries, and augmented basement membrane thickening within retinal capillaries, compared to age-matched controls [73]. These findings suggest that eNOS is essential for maintaining vascular integrity in diabetes.

In bovine microvascular retinal endothelial cells, increased glucose levels diminished the activity of eNOS stimulated by agonists and flow [74]. Another investigation conducted on bovine retinal microvascular endothelial cells revealed that high glucose levels and AGE suppress eNOS expression [21]. This suppression aligns with studies in rats, where decreased eNOS expression was reported in various vascular beds during diabetes progression, accompanied by elevated iNOS expression and nitrotyrosine levels, potentially contributing to vascular disease exacerbation in diabetes [75]. In support of this premise, pharmacological inhibition of iNOS with aminoguanidine enhanced dilation responses in retinal arterioles of diabetic rats, suggesting a contribution of iNOS to impaired vasodilation in DR [76]. These findings are consistent with observations in other vascular beds affected by diabetes, where induction of iNOS expression was linked to impaired NO-dependent vasodilation responses [77, 78]. Additional studies have also elucidated the regulatory role of the bradykinin 1 receptor (B1R) on iNOS expression. Brovkovych et al. [79] demonstrated in HEK293 cells that B1R modulates iNOS expression via the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. Further investigations determined that inhibition of B1R through diverse antagonists such as LF22-0542 or SSR240612 can reverse iNOS upregulation in the rodent diabetic retina [80, 81]. The axis B1R–iNOS and the significance of iNOS in the diabetic retina were also assessed employing the selective iNOS inhibitor 1400W. Othman and colleagues [82] evaluated the effect of iNOS inhibition on inflammation and oxidative stress, as well as the relationship between B1R and iNOS expression, in a murine model of type 1 diabetes, applying 1400W as eye drops twice a day. The authors concluded that B1R and iNOS establish a reciprocal auto-induction and amplification loop, fostering NO formation and inflammatory processes in the diabetic mouse retina [82]. Particularly noteworthy is the significant role of iNOS in leukostasis events and the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in the diabetic retina. In this regard, Leal et al. [83] reported that in diabetic iNOS–/– mice, these events are prevented, akin to the inhibitory effect observed after the administration of L-NAME. Consistent with these findings, an investigation by Iwama and colleagues [84] in iNOS–/– mice during endotoxin-induced uveitis described how a deficiency in iNOS hindered leukocyte–endothelial cell interaction in the retina, suggesting the potential targeting of iNOS in the treatment of uveitis and other inflammatory conditions.

Therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating NOS isoforms typically focus on either enhancing or inhibiting NOS expression or activity through cofactor supplementation or oxidative stress reduction. Intriguingly, research indicates that prolonged administration of L-arginine, the substrate for NOS, fails to elevate NO production or enhance endothelial function. Instead, chronic L-arginine administration has been found to elevate products of the arginase pathway, namely urea and L-ornithine, without a concomitant increase NOS pathway products [85]. Arginase manifests in two distinct isoforms, namely arginase 1 and arginase 2, both of which compete with NOS for L-arginine. This competition restricts NO production and leads to uncoupling of NOS [86, 87]. Uncoupled NOS utilizes molecular oxygen to generate a superoxide anion. The superoxide then rapidly reacts with available NO, forming the harmful oxidant peroxynitrite, exacerbating nitro-oxidative stress. Therefore, reducing arginase expression and/or function may represent a strategy to alleviate oxidative stress. A recent study on retinal arterioles from pigs with early type 1 diabetes revealed that elevated arginase activity impaired NOS-mediated dilation. Blocking arginase activity with 2S-amino-4-[[(hydroxyamino)iminomethyl]amino]-butanoic acid (nor-NOHA) fully restored arteriolar vasodilator function, suggesting that inhibiting vascular arginase could enhance endothelial function in the early stages of diabetes [11]. In mice with diabetes, retinal arginase activity and arginase 1 expression significantly increased after two months of hyperglycemia or after treatment of retinal microvascular endothelial cells with high glucose concentrations [88]. Double knockout of one copy of arginase 1 and both copies of arginase 2 in mice with diabetes, or blockade of arginase in retinal microvascular endothelial cells, significantly reduced superoxide production, affirming the involvement of arginase in diabetes- or hyperglycemia-triggered oxidative stress. Furthermore, the advantages of inhibiting arginase in these diabetic models were associated with increased NO generation and diminished leukocyte adhesion, implying the contribution of NOS uncoupling to the pathological process [88]. Additionally, a study utilizing in vivo and ex vivo models demonstrated that diabetes compromises endothelium-dependent relaxation of retinal blood vessels. Notably, heterozygous deletion of arginase 1 or arginase blockade provided significant protection from diabetes-driven retinal vascular impairment [89]. In a recent study involving a mouse model of type 2 diabetes, arginase 2 was implicated in obesity-induced retinal injury. Mice that were fed a Western diet for 16 weeks displayed notably elevated levels of arginase 2 in their retinas, which correlated with abnormal or exaggerated photoreceptor light responses. The removal of arginase 2 provided significant protection against this obesity-induced photoreceptor abnormality, leading to reduced retinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and microglia/macrophage activation [90]. Furthermore, other studies have shown increased levels of arginase 2 during the ischemic phase of OIR, coinciding with elevated nitro-oxidative stress, increased iNOS expression, impaired physiological vascular repair, and notable vitreoretinal neovascularization. Remarkably, these effects were ameliorated by the deletion of arginase 2 [91, 92].

In mice subjected to ischemia/reperfusion, there was a significant increase in

retinal arginase 2 mRNA and protein levels 3 hours following the event

[93]. Deletion of arginase 2 provided protection against

ischemia/reperfusion-induced impairment of retinal function and neuronal

degeneration, thwarting the formation of acellular capillaries by mitigating

nitro-oxidative stress and inhibiting glial activation [93]. Conversely,

heterozygous deletion of arginase 1 exacerbated neurovascular

degeneration after ischemia/reperfusion, suggesting a protective role for

arginase 1 expression in certain cells [94]. Recently, it has been demonstrated

in mice subjected to ocular ischemia/reperfusion that arginase 1 exerts

anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages through ornithine decarboxylase-mediated

suppression of histone deacetylase 3 and interleukin-1

A critical regulator of NO production by all three NOS isoforms is the cofactor

BH

A promising agent recognized for its capacity to reduce oxidative stress and enhance eNOS expression and function is the phytoalexin resveratrol. Resveratrol, along with resveratrol-containing red wines, has been demonstrated to upregulate eNOS expression in vascular endothelial cells [98, 99, 100]. In a previous investigation, resveratrol mitigated ischemia/reperfusion-triggered endothelial dysfunction and impairment of vascular autoregulation in mouse retinal blood vessels by downregulating NOX2 expression and nitro-oxidative stress [101]. Notably, in this study, resveratrol did not modulate the mRNA levels of any of the three NOS isoforms [101]. However, besides enhancing eNOS expression, resveratrol has been shown to augment the enzymatic activity of eNOS through post-translational modifications. This includes promoting eNOS Ser-1177 phosphorylation, facilitating SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of eNOS at Lys-496 and Lys-506, or diminishing caveolin-1 expression or its interaction with eNOS [102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107]. Moreover, resveratrol prevents from eNOS uncoupling, a phenomenon wherein eNOS generates superoxide under pathological conditions [108, 109, 110].

Interesting compounds capable of mitigating ischemic and diabetic retinopathy include NOX inhibitors. As previously discussed, NOX emerges as a potential therapeutic target due to its central role in promoting ROS generation and excess in these conditions. Not surprisingly, numerous synthetic molecules and natural compounds have been proposed as NOX inhibitors to counteract nitro-oxidative stress in ischemic and DR [111]. For example, promising synthetic NOX inhibitors include GKT136901 and GKT137831, acknowledged as potent, orally active, bioavailable, and specific NOX1/4 inhibitors [112]. Research by Appukuttan et al. [113] demonstrated that GKT136901/GKT137831 markedly reduced ROS production and VEGF-A expression in dimethyloxalylglycine-exposed human retinal endothelial cells. In another study by Jiao et al. [114], GKT137831 treatment attenuated caspase-3 activity in retinal cells exposed to high glucose levels. Additionally, research by Deliyanti and colleagues [57] indicated that GKT136901 treatment decreased ROS levels and mitigated vascular permeability in a rat diabetic model. Dionysopoulou and colleagues [58], using a rodent model of diabetic retinopathy—demonstrated the efficacy of a topical administration of GLX7013114 (NOX4 inhibitor) in preserving retinal ganglion cell function and in decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators in the diabetic retina, collectively reducing diabetes-related leakage in retinal tissue.

Another noteworthy therapeutic avenue in retinal microvascular disorders is the

endocannabinoid system. This system encompasses endogenous, bioactive lipid

mediators known as endocannabinoids (e.g., N-arachidonoylethanolamine,

2-arachidonoylglycerol), the enzymes involved in their synthesis and metabolism,

and their receptors—cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) and cannabinoid receptor 2

(CB2R) [115]. Both CB1R and CB2R belong to the G protein-coupled receptor

superfamily, and their molecular cascades are diverse and complex, depending on

the cell type. They involve the downstream modulation of various intracellular

mediators, including NOS, adenyl cyclase, mitogen-activated protein kinases

(MAPKs), protein kinases A and C, in addition to regulating the functionality of

various Ca

Exendin-4, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, has been demonstrated to restore injured microvascular permeability in a rat retinal ischemia/reperfusion model through activation of the GLP-1 receptor-PI3K/Akt-eNOS/NO-cGMP pathway [134]. Zhou et al. [135] observed in a OIR model that another GLP-1 receptor agonist, NLY01, inhibited activation of mononuclear phagocytes and expression of cytokines in vivo, thereby significantly suppressing retinal inflammation, promoting reparative angiogenesis, and inhibiting pathological retinal neovascularization. Similarly, Tang and colleagues [136] provided mechanistic insights into the effects of GLP-1 in diabetes, demonstrating in diabetic rats that GLP-1 mitigated endothelial barrier injury through activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway and inactivation of RAGE/Rho/ROCK as well as MAPK signaling pathways. Consistent with these findings, Wei et al. [137] showed in diabetic mice that GLP-1 treatment reduced retinal leakage and improved blood-retinal barrier function by suppressing the RhoA/ROCK pathway.

A study investigating therapeutic approaches in diabetic retinopathy suggested that the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, captopril, alleviated oxidative damage in DR by reducing iNOS, peroxynitrite, ROS, and NO levels, while increasing eNOS expression [138]. Similarly, tert-butylhydroquinone, a synthetic aromatic organic compound, was found to protect the diabetic rat retina from oxidative stress by upregulating the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway [139]. Simvastatin, used to treat high cholesterol and triglyceride levels, was shown to suppress the formation and progression of diabetic retinopathy in rats by increasing circulating endothelial progenitor cells, reducing mRNA expression levels of iNOS, Ang-1, and Ang-2, and increasing eNOS mRNA expression in the retina [140]. Ginger extract was reported to improve DR by reducing oxidative damage, inflammation, iNOS, and VEGF expression, while enhancing eNOS and G6PDH function [141]. Naringenin, a natural flavonoid compound, was demonstrated to upregulate GTPCH1/eNOS signaling to ameliorate high glucose-induced retinal endothelial cell injury [142].

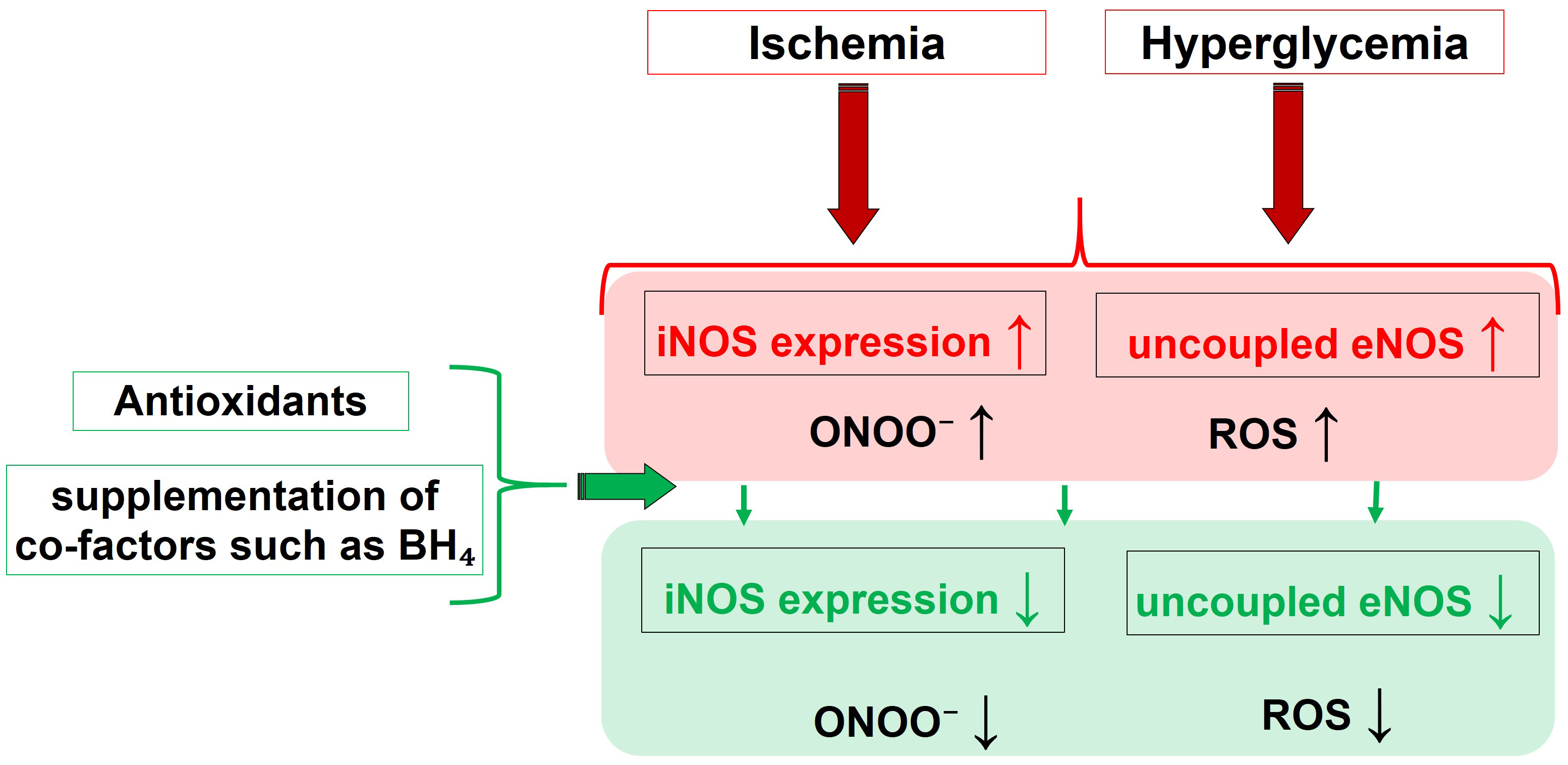

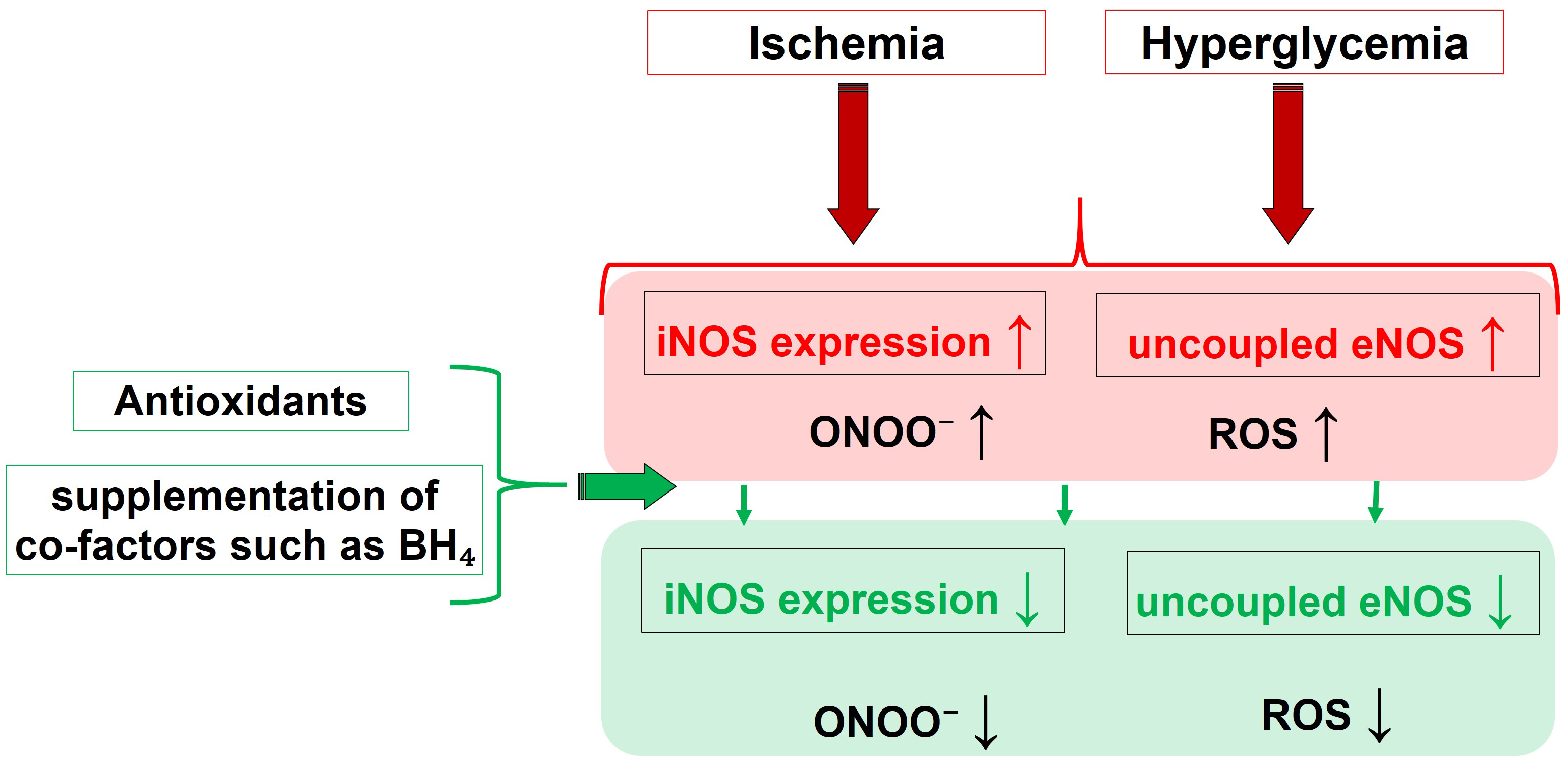

Fig. 3 summarizes the main pathophysiological triggers and their influence on the activity of different NOS isoforms, leading to nitro-oxidative stress, and highlights the effects of molecules capable of restoring altered redox status and NOS functionality.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Pathophysiological drivers and their effect on the NOS

functionality, that culminate into nitro-oxidative Stress. Molecules able to

restore the eNOS function, like BH

In summary, all three NOS isoforms are detectable within retinal blood vessels. While eNOS and nNOS play roles in maintaining retinal perfusion under normal physiological conditions, iNOS becomes activated in response to pathophysiological conditions such as retinal ischemia or elevated glucose levels. The overproduction of NO by iNOS induces nitro-oxidative stress, culminating in vascular endothelial dysfunction and cellular damage within the retina. Likewise, eNOS may become dysfunctional under oxidative stress, amplifying ROS generation and adding to endothelial dysfunction and cellular harm.

Potential strategies to restore proper NOS function include modulating arginase

expression/activity and supplementing BH

Conceptualization, AG; writing—original draft preparation, AG and FB; writing—review and editing, AG; visualization, FB; supervision, AG. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

Given his role as Guest Editor, Adrian Gericke had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Said El Shamieh. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.