1 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Vali-e-Asr University of Rafsanjan, 7718897111 Rafsanjan, Iran

Abstract

Plant diseases caused by pathogens pose significant threats to agricultural productivity and food security worldwide. The traditional approach of relying on chemical pesticides for disease management has proven to be unsustainable, emphasizing the urgent need for sustainable and environmentally friendly alternatives. One promising strategy is to enhance plant resistance against pathogens through various methods. This review aims to unveil and explore effective methods for stimulating plant resistance, transforming vulnerable plants into vigilant defenders against pathogens. We discuss both conventional and innovative approaches, including genetic engineering, induced systemic resistance (ISR), priming, and the use of natural compounds. Furthermore, we analyze the underlying mechanisms involved in these methods, highlighting their potential advantages and limitations. Through an understanding of these methods, scientists and agronomists can develop novel strategies to combat plant diseases effectively while minimizing the environmental impact. Ultimately, this research offers valuable insights into harnessing the plant’s innate defense mechanisms and paves the way for sustainable disease management practices in agriculture.

Keywords

- stimulating plant resistance

- vigilant defenders

- priming

- ISR

- genetic engineering

- sustainable disease management

Plants play a crucial role in sustaining life on Earth, providing us with food, fiber, fuel, and numerous other resources [1]. However, their productivity and survival are constantly challenged by various pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and pests [2, 3, 4]. These pathogens can cause devastating diseases that lead to significant crop losses and threaten global food security [5, 6, 7]. In response to these challenges, plants have developed intricate defense mechanisms to protect themselves against pathogens. The concept of plant resistance refers to the ability of plants to recognize and respond to pathogen attacks [8, 9, 10, 11]. Understanding and harnessing plant resistance is of paramount importance for sustainable agriculture and crop protection. Traditional approaches to disease management often rely on the use of chemical pesticides, which can have detrimental effects on the environment and human health. Moreover, pathogens can develop resistance to these chemicals over time, rendering them less effective [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. Transitioning from a model of vulnerability to one of vigilance, where plants are empowered to defend themselves against pathogens, offers a more sustainable and environmentally friendly approach to disease management. By boosting plant resistance, we can reduce reliance on synthetic pesticides, minimize the environmental impact, and promote healthier ecosystems [17, 18, 19].

Various methods and techniques have been developed to stimulate and enhance plant resistance against pathogens. These methods can be broadly categorized into two main approaches: conventional breeding and biotechnological interventions. (1) Conventional breeding approach involves selectively breeding plants with desirable resistance traits through classical breeding techniques. It relies on natural genetic variations within plant populations and aims to develop new cultivars with improved resistance. Conventional breeding methods often take advantage of techniques such as marker-assisted selection and quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping to identify and incorporate resistance genes into breeding programs [20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. (2) Biotechnology offers powerful tools to engineer or augment plant resistance traits. Genetic engineering techniques, such as transgenic approaches, enable the introduction of specific genes into plants to confer resistance against pathogens [25, 26, 27]. For example, plants can be engineered to produce antimicrobial peptides or proteins that directly inhibit pathogen growth [28, 29]. Additionally, genome editing techniques, such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats–CRISPR-associated (CRISPR-Cas9), allow precise modifications of the plant’s own genetic material to enhance resistance [30, 31, 32].

Other biotechnological strategies include the use of beneficial microbes, such as rhizobacteria and mycorrhiza fungi, which can establish symbiotic relationships with plants and stimulate their immune responses [33, 34, 35]. Moreover, elicitors derived from pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or plant-derived compounds can be applied to induce systemic acquired resistance (SAR) or induced systemic resistance (ISR), respectively [36, 37, 38]. Also viral cross protection in plants is known as an acquired immunity phenomenon, that a mild virus isolate/strain can protect plants against economic damage caused by a severe challenge strain or isolate of the same virus [39, 40, 41]. These methods to stimulate plant resistance are not mutually exclusive and can be combined to achieve synergistic effects in enhancing plant defenses against pathogens [42, 43, 44].

In summary, understanding and harnessing plant resistance is crucial for sustainable agriculture. By transitioning from vulnerability to vigilance and utilizing various breeding and biotechnological methods, we can empower plants to defend themselves against pathogens, reduce reliance on chemical pesticides, and promote more sustainable crop protection practices.

Plant-pathogen interactions form a complex and dynamic field of study within the realm of plant pathology [45, 46, 47]. Plants have evolved intricate defense mechanisms to protect themselves against invading pathogens, while pathogens have developed various strategies to overcome these defenses and establish successful infections [48, 49]. Understanding the intricacies of these interactions is crucial for developing effective strategies to manage plant diseases and ensure global food security. This section will delve into the key components of plant-pathogen interactions, including the recognition process, signaling pathways, and defense mechanisms employed by both the plant and the pathogen.

This process consists of two main parts: (1) Pathogen-associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) and Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs); (2) Effector-triggered Immunity (ETI). The recognition process in plant-pathogen interactions begins with the detection of conserved microbial molecules known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by the plant’s pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [50, 51, 52]. PAMPs can be structural components of pathogens such as chitin or flagellin, which are recognized by specific PRRs present on the surface of plant cells [53, 54]. The binding of PAMPs to PRRs triggers a series of events leading to the activation of defense responses [55, 56].

Some pathogens, known as biotrophic pathogens, secrete effector molecules into the plant cells to suppress host defenses and establish successful infections [57, 58, 59]. However, plants have evolved Resistance (R) proteins that recognize specific effector molecules and trigger a strong immune response called Effector-triggered Immunity (ETI) [60, 61]. ETI often leads to localized hypersensitive responses, where the infected plant cells undergo programmed cell death to limit the pathogen’s spread [62, 63, 64].

Fig. 1 shows the different stages of the signaling pathway. Signaling pathway include three steps, that we explain these steps: (1) Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway: Upon PAMP perception or ETI activation, plants activate signaling pathways to transmit the defense signals throughout the plant [65, 66, 67]. One of the central signaling pathways involved in plant immunity is the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway [68, 69]. MAPK cascades are activated upon PRR or R protein activation and regulate various defense responses, including the production of antimicrobial compounds, reinforcement of cell walls, and induction of defense-related genes [70, 71, 72].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.The different stages of the signaling pathway. MAMPs, Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns; PRR, Pattern Recognition Receptor; MAPK, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase.

(2) Salicylic Acid (SA)-Mediated Signaling Pathway: The salicylic acid (SA)-mediated signaling pathway is a crucial component of plant defense against biotrophic pathogens [73, 74, 75]. SA acts as a signaling molecule and regulates several defense-related processes, including the expression of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes, accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and activation of SAR [76, 77]. The SA pathway often functions in parallel with other signaling pathways to provide robust and effective defense against pathogens [78, 79].

(3) Jasmonic Acid (JA)-Mediated Signaling Pathway: The jasmonic acid (JA)-mediated signaling pathway plays a significant role in defense against necrotrophic pathogens and herbivorous insects [79, 80, 81]. JA and its derivatives, known as Jasmonate, regulate the expression of numerous defense-related genes, leading to the production of toxic metabolites, proteinase inhibitors, and other defensive compounds [82, 83]. The JA pathway also interacts with other signaling pathways, such as the SA pathway, to fine-tune plant defense responses [84, 85].

Plant defense mechanisms against pathogens are extremely complex. Different ways of protecting themselves against external factors are used by plants. In the event that a defense barrier against the pathogen attack is not effective, the plant uses a different method to suppress the pathogen attack. Plant defense mechanisms against pathogens are summarized in Fig. 2. A further description of each of these mechanisms will be provided.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Plant defense mechanisms against pathogens. PGPR, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria; miRNA, microRNA.

Plants possess physical barriers that act as the first line of defense against pathogens. The plant cell wall provides a physical barrier that can prevent pathogen entry. Additionally, plants produce specialized structures like trichomes, thorns, and waxes that can impede pathogen movement and colonization. Furthermore, stomatal closure, induced by pathogen detection, restricts pathogen entry through leaf pores [86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94].

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites from plants is related to induced chemical defense generated for protection against different phytopathogenic attack [95]. Plants produce an array of chemical compounds that can inhibit pathogen growth, deter herbivores, and attract beneficial organisms. These chemical defenses include antimicrobial compounds (phytoalexins), toxic secondary metabolites (alkaloids, terpenoids), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that can act as signaling molecules to attract natural enemies of the pathogen [96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102]. For example in Calceolaria spp. (a notorious weed and as a popular ornamental garden plant) is synthesized a number of iridoids, flavonoids, naphthoquinones and phenylpropanoids that have been shown to possess biological activities. These metabolites have activities insecticides, fungicides, and Bactericidal [95]. In the Gramineae, the cyclic hydroxamic acids 2,4-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIBOA) and 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA) form part of the defense against insects and microbial pathogens [103]. Benzoxazinoids are a class of indole-derived plant chemical defenses comprising compounds. These phytochemicals are widespread in grasses, including important cereal crops such as maize, wheat, and rye, as well as a few dicot species, and display a wide range of antifeedant, insecticidal, antimicrobial, and allelopathic activities [104]. Also DIMBOA in Maize seedlings is directly associated with multiple insect-resistance against insect pests such as Asian corn borer and corn leaf aphids [105].

RNA silencing is an important defense mechanism employed by plants to regulate gene expression and combat invading pathogens. Small RNA molecules, known as small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or microRNAs (miRNAs), can target pathogen-derived nucleic acids, leading to their degradation and subsequent inhibition of pathogen gene expression. RNA silencing also plays a role in regulating plant developmental processes and stress responses [106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117].

ISR is a defense mechanism in which local infection by certain pathogens triggers enhanced resistance throughout the entire plant. ISR is mediated by beneficial microbes present in the rhizosphere, such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). These microbes induce systemic defense responses in the plant, priming it to mount stronger defenses against future infections [38, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124]. The use of beneficial microorganisms as biocontrol agents has gained significant attention in recent years due to their potential to reduce chemical pesticide dependence, mitigate environmental risks associated with synthetic pesticides, and contribute to sustainable agricultural practices. These biocontrol agents can act directly or indirectly in plant defense by antagonizing pathogenic microbes through competition, antibiosis, parasitism, induced resistance, or by enhancing the plant’s own defense mechanisms [125, 126]. Various groups of microorganisms have been identified as inducers of systemic resistance in plants. (1) PGPR: PGPR are a diverse group of bacteria that colonize the rhizosphere and promote plant growth through various mechanisms. Many PGPR strains are capable of inducing systemic resistance in plants. Examples include strains of Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Serratia, which have been shown to effectively protect crops against diseases caused by fungal, bacterial, and viral pathogens [127, 128, 129, 130]. (2) Mycorrhizal Fungi: Mycorrhizal fungi form mutualistic associations with plant roots, facilitating nutrient uptake and providing other benefits to the host plant. Certain species of mycorrhizal fungi, such as Trichoderma and Glomus, have been found to induce systemic resistance in plants. These fungi can colonize the plant roots and trigger a range of defense responses that confer protection against pathogens [131, 132, 133]. Table 1 (Ref. [134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156]) shows the types of defense mechanisms in plants against pathogens and defense pathways in plant-pathogen interaction.

| Defense mechanisms | Pathogen | Host | Signaling pathway | Reference |

| Physical Barriers | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi | Pea | cell wall strengthening, formation of papilla-like structures at penetration sites and accumulation of different substances within and between cells | [134] |

| Physical Barriers | Botrytis bunch rot | Grapes | Increase in cuticle thickness | [135] |

| Physical Barriers | Alternaria alternata | Tomato | enhancement of alkaloids and terpenoids along with increase in cell wall hemicellulose content (cellulose, lignin and pectin) | [136] |

| Physical Barriers | Pseudomonas solanacearum | Tomato | In resistant cultivars, tyloses occluded the colonized vessels and the contiguous ones, limiting bacterial spread | [137] |

| Chemical Defenses | Rhizoctonia solani | rice | alkaloid and terpenoid compounds in the leaf extracts of Zizyphus jujube: increase in chitinase, |

[138] |

| Chemical Defenses | Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici | Wheat | high expression of metabolites from thiamine and glyoxylate, such as flavonoid glycosides: defense response strategy by wheat varieties and biochemical changes in the expression of wheat metabolites | [139] |

| Chemical Defenses | Blumeria graminis | Wheat | tryptophan and pyrimidine metabolism, soquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, phenolic acids, flavonoid carboglycosides, indole alkaloids, phenolic amines, amino acids | [140] |

| Chemical Defenses | Fusarium crown rot | Wheat | higher content of benzoxazolin-2-one (BOA) and 6-methoxy-benzoxazolin-2-one (MBOA): resistance to Fusarium crown rot | [141] |

| Chemical Defenses | streak mosaic virus | Wheat | increase in amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism and alkaloids pathways | [142] |

| Chemical Defenses | late blight | Potato | increase in benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) in response to pathogen infection and cell wall reinforcement | [143] |

| Chemical Defenses | Alternaria solani | Tomato | Activation metabolic (steroidal glycol-alkaloid, lignin, and flavonoid biosynthetic pathways) | [144] |

| RNA Silencing | Verticillium genus | Arabidopsis | RNA silencing: role in defence against bacterial plant pathogens through modulating host defence responses | [145] |

| RNA Silencing | Fusarium graminearum | Barley | targeting key components of the fungal RNAi machinery via spray-induced gene silencing: protect barley leaves from Fusarium infection | [146] |

| RNA Silencing | Hyaloperonospora parasitica | Arabidopsis | The RPP5 (for recognition of Peronospora parasitica 5) locus is poised to respond to pathogens that disturb RNA silencing | [147] |

| RNA Silencing | barley stripe mosaic virus | Wheat | Virus-induced gene silencing: a powerful tool for dissecting the genetic pathways of disease resistance in hexaploid wheat | [148] |

| RNA Silencing | Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici | Wheat | RNA interference: efficiently and durably control, hyphal development strongly restricted; necrosis of plant cells as resistance responses | [149] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by different strains bacterial (from the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere) | Fusarium root and crown rot | Wheat | Pseudomonas mediterranea: by inducing antioxidant enzyme activity and resistance to disease | [150] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by Pseudomonas fluorescens | Take-all disease | Wheat | Increased the activities of |

[151] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by Trichoderma pubescens | Rhizoctonia solani | Tomato | Increase in antioxidant enzyme production | [152] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by Trichoderma hamatum | tobacco mosaic virus | Tomato | Increases in the transcriptional levels of polyphenol genes and pathogenesis-related proteins | [153] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by Trichoderma | powdery mildew | Grapevines | Increase in chitinase and |

[154] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by Bacillus | Sarocladium oryzae | Rice | Increase in defense enzymes and reactive oxygen species | [155] |

| Induced Systemic Resistance by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae | Phytophthora parasitic | Tomato | Increase in phenolics and plant cell defense responses | [156] |

2.3.4.1 Role of Beneficial Microorganisms in Plant Defense

Beneficial microorganisms lead to the induction of defense reactions and ISR through different processes (Fig. 3). These processes include:

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.The role of beneficial microorganisms in plant defense.

(1) Competition: Certain beneficial microorganisms compete with plant pathogens for resources such as space, nutrients, and moisture, thereby limiting the growth and establishment of pathogenic populations. This competitive exclusion can effectively suppress pathogen colonization and subsequent disease development [157, 158, 159, 160].

(2) Antibiosis: Some biocontrol agents produce antimicrobial compounds, such as antibiotics or antifungal metabolites that inhibit the growth and activity of plant pathogens. These compounds can directly kill or inhibit the pathogens, preventing them from causing diseases in plants [161, 162, 163, 164].

(3) Parasitism: Certain beneficial microorganisms are parasites of plant pathogens. They can infect and consume the pathogens, leading to their decline and control [165]. Examples include mycoparasitic fungi that attack other fungi [166, 167], bacteriophages that infect and destroy bacteria [168, 169, 170], and nematodes that feed on plant-parasitic nematodes [171, 172, 173].

(4) Plant Growth Promotion: In addition to their role in plant defense, beneficial microorganisms can promote plant growth and development. They can produce plant growth-promoting substances like auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins, which enhance root and shoot growth, increase nutrient availability, and improve stress tolerance in plants.

2.3.4.2 Application Methods and Considerations for Using Biocontrol Agents

The successful implementation of biocontrol agents relies on appropriate application methods and considerations to ensure their efficacy and sustainability. The following aspects need to be taken into account when using biocontrol agents:

(1) Selection of Effective Strains: The first step in utilizing biocontrol agents is selecting appropriate strains with demonstrated efficacy against specific plant pathogens. These strains should have a proven track record of disease suppression, compatibility with target crops, and environmental adaptability [174, 175, 176]. In choosing a biocontrol strain, it should be noted that not all biocontrol agents have the same biocontrol activity and the best type of strain should be identified with laboratory screenings [176, 177]. Some strains may induce plant resistance under field conditions, providing effective suppression of disease and that there may be some benefit to the integration of rhizosphere-applied strains and foliar-applied biological control agents [178]. The effectiveness of plant growth—promoting bacteria is variable under different biotic and abiotic conditions. Abiotic factors may negatively affect the beneficial properties and efficiency of the introduced PGPR inoculants [179]. Also has been reported the combination of microorganisms gives better results probably due to the different mechanisms used [180, 181].

(2) Formulation Development: Biocontrol agents are typically formulated into products that facilitate their storage, handling, and application. Formulations can include granules, powders, liquids, or carrier-based systems. The choice of formulation depends on factors such as target pathogens, crop type, application method, and economic feasibility [182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196]. The application of delivery system based on encapsulation technology shows a promising technique to store and deliver biocontrol agents [197, 198]. Generally encapsulation improves the viability, stability, and controlled release of bacteria [199]. The encapsulation process consists of incorporation of an active core into a matrix structure through mechanical action, followed by stabilization by chemical or physicochemical means [200].

Of course, in encapsulation, attention should also be paid to the coating in

which the biocontrol agents are enclosed. Today, much attention is paid to

polymer and protein coatings such as chitosan, alginate, and whey, which have

biocompatibility properties [192, 194, 195, 199, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207]. For example in a

research in order to biological control of Damping-off disease due to

Pythium aphanidermatum was synthesis a suitable formulation for a

Streptomyces fulvissimus Uts22 strain based on alginate–Arabic gum and

nanoparticles (SiO

(3) Application Timing: Timely application of biocontrol agents is crucial for effective disease management [212, 213]. It is essential to identify the critical periods during which pathogen establishment and infection are most likely, and apply biocontrol agents accordingly. Early preventive application is often employed to establish a protective layer around the plant roots or foliage before pathogens become established.

(4) Application Methods: Several application methods can be used to introduce biocontrol agents into the plant system. These methods include seed treatment, soil drenching, foliar spraying, root dip, and soil incorporation. The choice of application method depends on factors such as the target pathogen’s location, stage of crop growth, formulation type, and available equipment [214, 215]. The delivery of a high number of viable cells to the plant is a prerequisite to reach a satisfactory colonization rate, which in turn enhances the desired effect in the field. A product has to display a sufficiently long shelf life, which describes the stability throughout the production process, packaging, storage and transport conditions. During subsequent application on the field, the inoculant is confronted with additional factors that are detrimental to its viability such as UV radiation, temperature and pH [216, 217, 218]. A suitable formulations is nesasory to enhance biocontrol agents efficiency at the target site and to facilitate the practical use by farmers [218, 219, 220, 221, 222].

(5) Environmental Factors: Environmental conditions can influence the success of biocontrol agent applications. Factors such as temperature, humidity, pH, and soil moisture should be considered to ensure optimal survival, establishment, and activity of the biocontrol agents. Compatibility with existing agricultural practices and pesticides should also be assessed to avoid potential interactions or negative effects [223, 224]. Selection of strains with multiple capabilities in different biological conditions can help in the sustainable management of diseases. For example in research a number of bacterial strains (Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas and Peribacillus) were examined under waterlogged conditions. Waterlogging shown to induce shifts in the bacterial strains potential, as well as on the structure of a population exhibiting a particular trait. The abundances of populations promoting nutrient availability to plants were found to increase after waterlogging, biocontrol protease activity proved to be the trait most sensitive to waterlogging. Enterobacter and Pantoea species were identified as main players in biofilm formation under waterlogging conditions. Waterlogging also appears to trigger the emergence of extremophilic and acidophilic bacteria, aspect important for potential adaptation of soil bacteria to future climate projections, with Bacillus and Pseudomonas showed best potential [225]. The efficiency of Bacillus biocontrol agents, however, is negatively influenced by ultraviolet (UV) radiation. But has been reported that preventive and repair molecular mechanisms of DNA caused by UV radiation are in B. subtilis. B. subtilis spores use recombination repair (in repairing damage resulting from UV–A), nucleotide excision repair (to repair UV–B and UV–C), and spore photoproduct lyase (to repairing UV–B and UV–C) [226]. Biological control agents have different growth in different temperature conditions [227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232]. Also, PGPR can compete with other bacteria by colonizing rapidly and accumulating a greater supply of nutrients, preventing other organisms from growing. PGPR has different strategies to colonize, of which each is related to a particular host [233, 234, 235]. It is necessary to mention researchers have explored sustainable tools for plant protection against pathogens, including the use of biological control agents (BCAs), which have the potential to complement or replace chemical fungicides. The complex interactions among a target pathogen, a host plant, and the BCA population in a changing environment can be studied by process-based, weather-driven mathematical models, able to interpret the combined effects on BCA efficacy of: (1) BCA mechanism of action, (2) timing of BCA application with respect to timing of pathogen infection (preventative vs. curative), (3) temperature and moisture requirements for both pathogen and BCA growth, and (4) BCA survival capability [236]. The environmental responses of BCAs should be considered during their selection, BCA survival capability should be considered during both selection and formulation, and weather conditions and forecasts should be considered at the time of BCA application in the field [236].

(6) Integrated Disease Management (IDM): The integration of biocontrol agents into an IDM program is essential for sustainable disease management [237, 238]. Biocontrol agents can be combined with other cultural, physical, or chemical control measures in a complementary manner to maximize their effectiveness while minimizing reliance on synthetic pesticides [239, 240, 241].

(7) Monitoring and Evaluation: Regular monitoring and evaluation of biocontrol agent efficacy are crucial for assessing their performance and making necessary adjustments. This may involve monitoring disease incidence, severity, crop health, and yield parameters. By monitoring the effectiveness of biocontrol agents, growers can make informed decisions regarding their continued use or the need for alternative control strategies [242, 243].

(8) Host genetic: The success of microbial biocontrol depends on the outcome of complex interactions among the plant host, beneficial microflora, pathogens, and environment [244, 245]. The host effect on biocontrol is mediated by different mechanisms. The discovery of a genetic basis in the host for interactions with a biocontrol agent suggests new opportunities to exploit natural genetic variation in host species to enhance understanding of beneficial plant-microbe interactions and develop ecologically sound strategies for disease control in agriculture [246, 247]. Various reports show that significant potential there is to exploit genetic variation in the host through breeding to enhance beneficial interactions with microorganisms. Plant breeding uses tremendous genetic variation in plant germplasm to increase crop productivity and enhance the plant’s ability to endure pathogens, pests, and abiotic stresses [246, 248, 249]. For example research to assess the role of the plant host in disease suppression, used a genetic mapping population of tomato to evaluate the efficacy of the biocontrol agent Bacillus cereus against the seed pathogen Pythium torulosum. This research detected significant phenotypic variation among recombinant inbred lines (RIL) that comprise the mapping population for resistance to P. torulosum, disease suppression by B. cereus, and growth of B. cereus on the seed. Genetic analysis revealed that three QTL associated with disease suppression by B. cereus explained 38% of the phenotypic variation among the recombinant inbred lines. In two cases, QTL for disease suppression by B. cereus map to the same locations as QTL for other traits, suggesting that the host effect on biocontrol is mediated by different mechanisms [246].

2.3.4.3 Application of ISR in Agriculture

The concept of induced systemic resistance has significant implications for sustainable agriculture and disease management. Harnessing the potential of beneficial microorganisms to enhance plant defense offers an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic pesticides and fungicides. Some key applications of ISR in agriculture include:

(1) Biological control of plant diseases: Beneficial microorganisms that induce systemic resistance can be used as biological control agents to protect crops against pathogens. By applying these microorganisms to the soil or seed treatments, farmers can reduce reliance on chemical pesticides and promote sustainable disease management [250, 251, 252].

(2) Enhanced crop productivity: Induced systemic resistance not only improves disease resistance but also has positive effects on plant growth and productivity. Plants treated with beneficial microorganisms often exhibit increased vigor, nutrient uptake efficiency, and tolerance to abiotic stresses, leading to higher yields and improved crop quality [253, 254].

(3) Reduction of chemical inputs: Utilizing induced systemic resistance can help reduce the dependence on synthetic chemicals in agriculture. By promoting natural defense mechanisms in plants, the need for chemical fungicides and pesticides can be minimized, thus reducing environmental pollution and potential health risks [255, 256].

(4) Crop rotation and intercropping strategies: Incorporating crops with different induced systemic resistance profiles into rotation systems or intercropping arrangements can help manage diseases more effectively. This approach disrupts the buildup of specific pathogens in the soil and promotes a diverse microbial community that enhances overall disease suppression [257, 258, 259].

2.3.4.4 Mechanisms of ISR

The mechanisms by which beneficial microorganisms induce systemic resistance in plants are complex and multifaceted. Several key processes have been identified:

(1) Priming: Beneficial microorganisms can prime the plant’s immune system, preparing it to respond more rapidly and effectively to pathogen attacks. This priming involves the activation of various signaling pathways and the up regulation of defense-related genes [260, 261, 262].

(2) Production of antimicrobial compounds: Some beneficial microorganisms produce antimicrobial compounds, such as antibiotics and antifungal metabolites that directly inhibit the growth and development of plant pathogens. These compounds can help protect the plant from infection and reduce disease severity [263, 264, 265].

(3) Induction of systemic acquired resistance (SAR): SAR is a long-lasting immune response that occurs throughout the entire plant following localized pathogen attack. Beneficial microorganisms can induce SAR in plants, leading to the production of antimicrobial proteins, phytoalexins, and other defense molecules that confer resistance against a wide range of pathogens [36, 266].

(4) Hormonal signaling: Beneficial microorganisms can modulate the plant’s hormonal balance, particularly the levels of salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene. These hormones play critical roles in regulating plant defense responses. By manipulating hormone levels, beneficial microorganisms can enhance the plant’s ability to defend against pathogens [267, 268, 269].

(5) Systemic signaling: Beneficial microorganisms can also elicit systemic signaling within the plant, where chemical signals are transmitted from the site of microbial colonization to distant parts of the plant. This systemic signaling helps activate defense responses in uninfected tissues, providing protection against future pathogen attacks [266].

In conclusion, understanding plant-pathogen interactions is essential for developing effective disease management strategies and ensuring global food security. The recognition process, signaling pathways, and defense mechanisms discussed in this section highlight the intricate mechanisms involved in plant immunity and pathogen virulence. Further research in this field is crucial to unravel the complexities of plant-pathogen interactions and discover new targets for disease control. One area of research that holds immense potential is the identification and characterization of effector proteins. Effector proteins are produced by pathogens and play a crucial role in suppressing plant defenses and promoting infection [270, 271]. Understanding the function and mode of action of these effectors can provide valuable insights into how pathogens manipulate the plant’s immune system. By targeting specific effectors, scientists can develop novel strategies to disrupt pathogen virulence and enhance plant resistance. Advancements in molecular biology and genomics have revolutionized the study of plant-pathogen interactions. Techniques such as next-generation sequencing and high-throughput functional genomics enable comprehensive analysis of pathogen genomes and the identification of key genes involved in virulence and host adaptation [272, 273, 274, 275, 276, 277, 278, 279]. This information can be utilized to develop diagnostic tools for early detection of pathogens and design crop breeding programs for enhanced disease resistance. Furthermore, exploring the role of beneficial microbes in plant immunity has gained significant attention in recent years. Certain microorganisms can form symbiotic relationships with plants, providing protection against pathogens through mechanisms such as induced systemic resistance. Harnessing the potential of these beneficial microbes could offer sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives to conventional chemical-based disease management strategies [38, 280, 281, 282, 283]. Collaboration between researchers, plant breeders, farmers, and policymakers is vital to translate scientific discoveries into practical solutions. By bridging the gap between academia and agriculture, innovative disease management strategies can be implemented on a larger scale, benefiting both small-scale farmers and large-scale agricultural systems. In conclusion, ongoing research into plant-pathogen interactions is instrumental in developing effective disease management strategies, reducing crop losses, and ensuring global food security. Continued investment in this field will lead to the discovery of novel approaches for disease control, ultimately contributing to sustainable and resilient agricultural systems.

Priming plant defense responses is a strategy employed by plants to enhance their ability to respond rapidly and effectively to potential threats such as pathogens, pests, and environmental stresses. This process involves the activation of various defense mechanisms, which are prepped and ready to be deployed when a threat is detected. Primed plants exhibit an enhanced defense response upon subsequent exposure to stressors, allowing them to mount a quicker and more efficient defense compared to non-primed plants [284, 285, 286, 287]. Priming mechanisms, sources of priming and its benefits are shown in Fig. 4. We will continue to explain these things.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Priming mechanisms, sources of priming and its benefits. BABA,

The factors that induce priming can be mentioned as follows:

(1) Beneficial Microbes: Certain beneficial microbes, such as rhizobacteria and mycorrhiza fungi, have been shown to prime plant defense responses. These microbes establish symbiotic relationships with plants and activate systemic signaling pathways that enhance plant defenses. They can induce hormonal changes, trigger defense gene expression, and enhance nutrient uptake, all of which contribute to priming [34, 43, 288, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293].

(2) Plant Extracts and Elicitors: Application of specific plant extracts or elicitors derived from microbial pathogens can also prime plant defense responses. These extracts contain bioactive compounds that mimic signals generated during pathogen invasion, triggering a defense response in the absence of actual threat. This pre-emptive activation prepares the plant for a rapid and effective response when encountering real pathogens or pests [294, 295, 296].

(3) Priming Agents: Synthetic compounds known as priming agents can be used to

induce priming in plants. These compounds are designed to mimic endogenous

signals or modulate hormone levels, thereby enhancing plant defense responses

[297]. Examples of priming agents include chemical inducers like

The mechanisms of priming are include: (1) Hormonal Signaling: Plant hormones

play a crucial role in priming plant defense responses. Jasmonic acid (JA),

salicylic acid (SA), ethylene (ET), and abscisic acid (ABA) are among the key

signaling molecules involved. These hormones regulate gene expression and

metabolic processes that contribute to defense responses. Priming promotes the

accumulation of these hormones or sensitizes the plant to their action, enabling

a faster and stronger defense response upon attack [304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312, 313, 314, 315]. (2) Reactive Oxygen

Species (ROS): Priming can induce the production of ROS, including hydrogen

peroxide (H

Priming has many advantages, which can be mentioned as follows: (1) Enhanced Defense Capacity: Primed plants possess an increased capacity to defend against various stresses, including biotic and abiotic challenges. The priming process allows them to rapidly activate defense mechanisms, resulting in faster pathogen recognition and containment, reduced damage, and improved survival rates [331, 332]. (2) Resource Allocation Efficiency: Priming enables plants to allocate resources more efficiently by priming only when necessary without constitutive activation of defense responses. This strategy minimizes energy expenditure under normal conditions while ensuring swift and effective responses in times of stress. (3) Systemic Protection: Priming can induce SAR or ISR, where the entire plant becomes more resistant to subsequent attacks by pathogens or pests. This systemic protection extends beyond the initially primed tissue, providing a broad-spectrum defense response throughout the plant [333, 334, 335].

In conclusion, priming plant defense responses is a sophisticated and dynamic process that prepares plants for potential threats. By priming various defense mechanisms, plants can mount faster and stronger responses when faced with pathogens, pests, or environmental stresses, ultimately improving their chances of survival and reducing damage. Understanding and harnessing the mechanisms of priming could have significant implications for sustainable agriculture and crop protection strategies in the future.

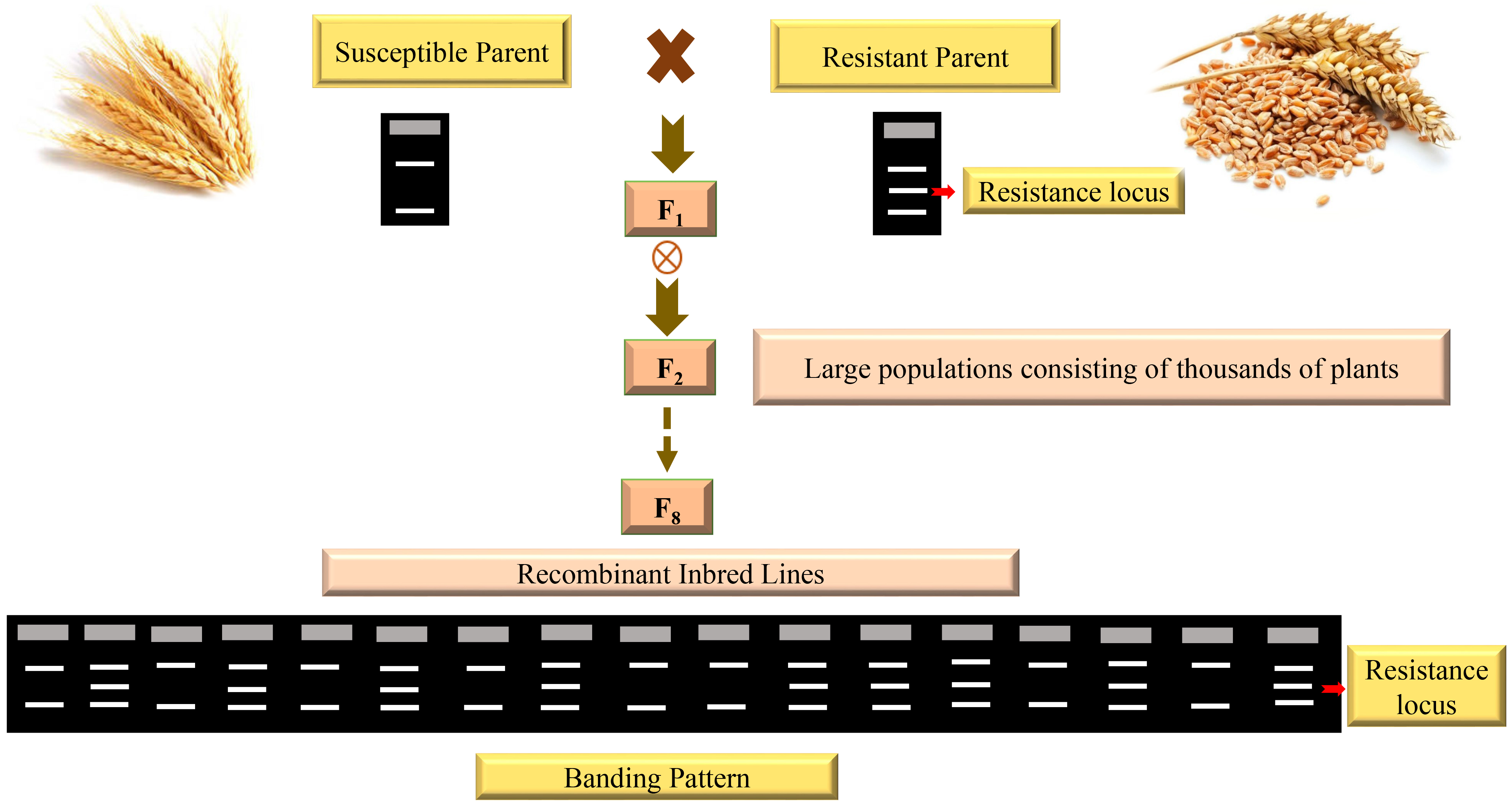

Breeding for resistance traits has long been a traditional approach to enhance plant resistance against pathogens. This method involves selecting and crossing plants with desirable resistance traits to develop new varieties that are resistant to specific pathogens. Through careful selection and breeding, plant breeders can introduce and amplify genes that confer resistance, resulting in improved disease resistance in subsequent generations. Advancements in genetic research and technology have aided breeders in identifying and incorporating specific resistance genes into commercial crop varieties more efficiently. The use of molecular markers and marker-assisted selection (MAS) techniques enables breeders to identify and track the presence of desired genes during the breeding process (Fig. 5). This targeted approach expedites the development of resistant varieties, saving time and resources compared to conventional breeding methods [336, 337, 338, 339, 340, 341, 342, 343, 344].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.Marker assisted selection.

Genetic modification techniques, such as genetic engineering or transgenic approaches, offer another avenue to enhance plant resistance to pathogens. This method involves introducing genes from other organisms into the plant’s genome to confer resistance against specific pathogens. By inserting genes encoding pathogen-derived resistance proteins or proteins involved in defense signaling pathways, scientists can create genetically modified (GM) crops with enhanced resistance [338, 345, 346]. One common genetic modification technique is the introduction of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) genes into crop plants to confer resistance against insect pests. Bt genes encode proteins toxic to specific insect pests, providing an effective means of pest control without the need for chemical insecticides [347, 348, 349, 350]. Similarly, researchers have successfully engineered plants with increased tolerance to viral, fungal, and bacterial infections by introducing genes encoding antiviral proteins, antimicrobial peptides, or enzymes involved in defense mechanisms [351, 352, 353, 354, 355, 356, 357].

(1) Bt cotton: Bt cotton is one of the most prominent examples of genetically modified crops exhibiting enhanced resistance. By introducing Bt genes into cotton plants, scientists have successfully conferred resistance against bollworms and other devastating insect pests. This has led to increased crop yield, reduced pesticide use, and improved economic outcomes for farmers [358, 359].

(2) Rainbow papaya: The rainbow papaya is an example of a genetically modified fruit that achieved resistance against the papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) [360, 361, 362]. By introducing a gene from the PRSV into the papaya genome, researchers developed transgenic papaya varieties that exhibited strong resistance to the virus [363, 364, 365]. This genetic approach saved the Hawaiian papaya industry from severe losses caused by PRSV infection.

(3) Late blight-resistant potato: Late blight is a devastating fungal disease that affects potato plants worldwide. Researchers have utilized genetic modification techniques to introduce genes from wild potato relatives that confer resistance against late blight. By incorporating these resistance genes into commercial potato varieties, scientists have successfully developed genetically modified potatoes with enhanced resistance to late blight, reducing crop losses and the need for fungicide applications [366, 367, 368, 369].

These case studies demonstrate the effectiveness of genetic approaches in enhancing plant resistance to pathogens. Genetic techniques offer targeted and precise solutions to combat specific diseases, providing sustainable options for improving crop productivity and reducing the reliance on chemical inputs. Nonetheless, it is crucial to consider the potential environmental and socioeconomic impacts associated with the deployment of genetically modified crops while ensuring rigorous safety assessments and regulatory frameworks are in place.

Cultural practices play a crucial role in managing and mitigating the impact of pathogens on crops. These practices involve various techniques and approaches that farmers can adopt to prevent, control, and reduce the occurrence of plant diseases. Cultural practices offer sustainable and environmentally friendly alternatives that promote long-term resilience in agricultural systems [370, 371, 372, 373]. One of the primary benefits of cultural practices is their ability to create an unfavorable environment for pathogens. By modifying growing conditions, farmers can discourage pathogenic organisms from thriving and spreading. This approach reduces the reliance on chemical inputs and minimizes the risks associated with pesticide resistance and environmental contamination [374].

Crop rotation is a widely employed cultural practice that involves systematically changing the type of crops grown in a particular field over successive seasons. This practice disrupts the life cycles of many pathogens, as different plants have varying susceptibility to specific diseases. By alternating crops, farmers can break the cycle of pathogens that rely on a single host species for survival, reducing their population densities and preventing the buildup of soil-borne pathogens. Additionally, crop rotation can improve soil health, nutrient availability, and overall plant vigor, further enhancing the ability of crops to resist diseases [375, 376, 377, 378, 379].

Sanitation practices focus on maintaining clean and pathogen-free farming environments. This includes removing infected plant debris, weeds, and diseased or dead plant material promptly. Infected plant residues left on the field provide a breeding ground for pathogens to survive and proliferate. Farmers should also regularly clean and disinfect tools, equipment, and machinery to prevent the transmission of pathogens between plants and fields. Proper sanitation measures minimize the chances of pathogen introduction and reduce inoculum levels, consequently lowering disease incidence and severity [380, 381].

Adopting appropriate planting techniques is another essential cultural practice for managing plant diseases. These techniques involve careful consideration of factors such as plant spacing, depth of planting, and timing of sowing [382, 383, 384]. By optimizing these parameters, farmers can promote better air circulation and light penetration within the crop canopy, reducing humidity and creating an unfavorable environment for many foliar pathogens. Additionally, proper planting techniques ensure optimal seedbed [385, 386, 387, 388, 389].

Water management practices have a significant impact on disease development in crops. Excessive or poorly timed irrigation can create favorable conditions for pathogens, especially those that thrive in moist environments [390, 391, 392, 393, 394]. On the other hand, deficit irrigation, as appropriate for specific crops, can induce stress responses in plants, making them more susceptible to certain diseases. By adopting precise and targeted irrigation methods, farmers can regulate moisture levels, minimize disease-friendly environments, and promote plant health and resilience [395, 396, 397, 398, 399].

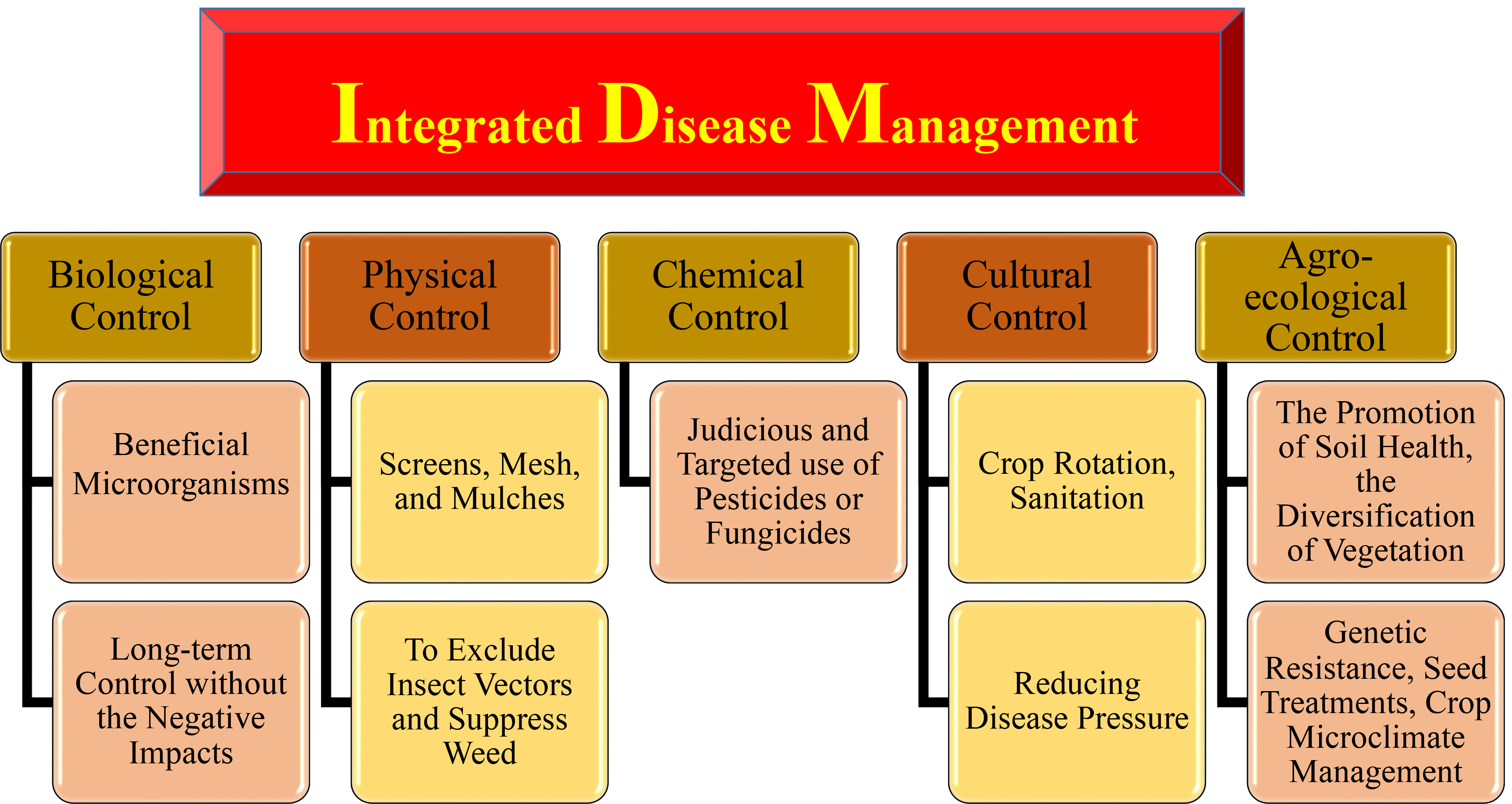

Integrated Disease Management (IDM) is an approach that combines various cultural, biological, physical, and chemical control methods to manage plant diseases effectively (Fig. 6) [400, 401, 402, 403].

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.Integrated Disease Management.

IDM strategies aim to integrate multiple approaches into a holistic management plan that maximizes disease control while minimizing negative environmental impacts and reducing reliance on any single control method [404, 405, 406]. The following are key components of IDM:

(1) Cultural Control: As discussed earlier, cultural practices form the foundation of IDM. Crop rotation, sanitation, and other cultural practices play a vital role in preventing the establishment and spread of pathogens [407, 408]. By adopting a comprehensive cultural control program, farmers can create an environment that promotes plant health and reduces disease pressure.

(2) Biological Control: Biological control involves the use of beneficial organisms to suppress or control plant pathogens. This includes the introduction of natural enemies such as predatory insects, parasitic nematodes, and microorganisms that antagonize pathogens [409, 410, 411, 412]. Biocontrol agents can help reduce pathogen populations, disrupt their life cycles, and provide long-term control without the negative impacts associated with chemical interventions.

(3) Physical Control: Physical control methods focus on creating physical barriers or modifying the environment to prevent pathogen entry or spread. This may involve the use of barriers like screens or mesh to exclude insect vectors [413, 414], employing mulches to suppress weed growth [415, 416, 417, 418], or implementing measures to improve air circulation and light penetration within plant canopies [419].

(4) Chemical Control: While the emphasis of IDM is on minimizing chemical inputs, judicious and targeted use of pesticides or fungicides can be part of an integrated approach. However, it is crucial to prioritize the use of low-risk or bio-based products and employ them only when other control methods are insufficient to manage disease outbreaks effectively. Integrated pest management (IPM) principles should guide the application of chemicals to minimize their impact on non-target organisms and the environment.

(5) Agro-ecological control: the objective of agro-ecological control is to promote healthy crops. The principles of agro ecological crop protection are identical to the principles of agro ecology from which they originate and they are inspired by certain principles of crop protection used in organic agriculture [403]. Agro ecological crop protection is a concept of crop protection based on cropping systems whose aim is to improve the sustainability of agroecosystems by taking into account their ecological functioning. Agro ecological crop protection aims to promote the ecological health of agroecosystems by directly or indirectly optimizing interactions between living (plant, animal, microbial) communities both below and above the ground. Agro ecological crop protection considers both biodiversity and soil health, to make agroecosystems less susceptible to biotic stresses [403, 420]. Agricultural management of diseases implies a comprehensive approach, in which farmers first consider the characteristics of the type of agriculture and its socio-economic context. Plant pathogens can be understood as a community or assemblage of organisms that includes a large genetics. Their functional diversity can be determined by using functional groups that are in accordance with their relationship with the design and management of system agriculture. These have different relationships with major agricultural management strategies, such as vegetation diversity, soil health promotion and landscape heterogeneity. Therefore, there is a need to complete general strategies including seed disinfection and selection of genotypes and cultivars with high genetic capability (resistant to living and non-living stresses) [403].

In conclusion, cultural practices form a cornerstone in the management of plant diseases. By implementing techniques such as crop rotation, sanitation, and adopting integrated disease management (IDM) strategies, farmers can create an environment that suppresses pathogens, enhances plant resistance, and promotes sustainable agricultural systems. Therefore, paying attention to all aspects of disease resistance, especially genetic resistance, and paying attention to the ecosystem is one of the basic criteria in agro ecological control.

Chemical elicitors are compounds that stimulate the defense responses in plants, leading to enhanced resistance against pathogens, pests, and environmental stresses. These elicitors can be naturally occurring or synthetic compounds that mimic the signals produced by pathogens during an attack. When applied to plants, chemical elicitors trigger a cascade of biochemical and physiological responses that ultimately result in the activation of various defense mechanisms [421, 422, 423, 424]. Chemical elicitors possess certain characteristics that make them effective in inducing plant resistance. Firstly, they have a high degree of specificity, meaning they can selectively activate specific defense pathways without causing harm to the plant. This specificity allows plants to allocate their resources efficiently towards combating the particular stress they are facing [423, 425, 426]. Secondly, chemical elicitors typically have low phytotoxicity, meaning they do not cause significant damage to plant tissues when applied at recommended concentrations. This is crucial for the practical application of these elicitors, as excessive phytotoxicity could offset the benefits gained from enhanced resistance [427, 428].

Furthermore, effective chemical elicitors are stable and easily applicable. They should remain active under a range of environmental conditions and be compatible with common application methods such as foliar sprays, seed treatments, or soil drenches. This ensures that the elicitor can be conveniently integrated into existing agricultural practices.

Chemical elicitors exert their effects through various modes of action, targeting different stages of the plant’s defense response. One common mode of action involves the recognition of the elicitor by specific receptors on the plant’s cell surface. This recognition triggers a signaling cascade that leads to the activation of defense-related genes and the production of defense compounds [36, 429]. Another mode of action involves the stimulation of the plant’s SAR pathway. SAR is a long-lasting defense response that occurs throughout the entire plant following an initial localized attack. Chemical elicitors can induce SAR by activating the production of signaling molecules, such as salicylic acid, that initiate the defense response in distal parts of the plant [429, 430, 431]. Chemical elicitors can also enhance the activity of certain enzymes involved in defense responses, such as chitinases or glucanases, which degrade the cell walls of pathogens. By increasing the activity of these enzymes, chemical elicitors contribute to a more effective defense against invading pathogens [432, 433, 434, 435, 436]. The effectiveness of chemical elicitors varies depending on several factors. Firstly, the specific elicitor and its mode of action play a crucial role. Different pathogens may trigger different defense pathways in plants, so an effective elicitor should be capable of activating the appropriate defense mechanisms for the given stress. Additionally, the timing and method of elicitor application are important. Applying the elicitor before the pathogen attack or at the early stages of infection often yields better results.

Furthermore, environmental conditions can influence the efficacy of chemical elicitors. Factors such as temperature, humidity, and light intensity can affect the responsiveness of plants to elicitors, highlighting the need for tailored application strategies based on the local environmental conditions.

While chemical elicitors hold significant potential as plant resistance inducers, there are several considerations and challenges associated with their use. One key consideration is the cost-effectiveness of incorporating elicitors into agricultural practices. Currently, many commercially available elicitors are relatively expensive, limiting their widespread adoption, particularly among small-scale farmers. Therefore, efforts are underway to develop cost-effective formulations and delivery methods to make these products more accessible [437, 438, 439, 440, 441, 442, 443]. Another challenge is the potential development of resistance in pathogens towards the elicitors. Continuous and extensive use of specific elicitors can exert selective pressure on the target organisms, potentially leading to the emergence of resistant strains. To mitigate this risk, it is important to rotate or combine different elicitors with distinct modes of action, making it more difficult for pathogens to develop resistance [444, 445].

Formulation and stability of chemical elicitors also pose challenges. Elicitors can degrade rapidly under certain conditions, reducing their shelf life and effectiveness. Developing stable formulations that ensure the long-term viability of the active compounds is crucial for practical application. Furthermore, the potential impact of chemical elicitors on non-target organisms and the environment must be carefully evaluated. While efforts are made to select elicitors with low toxicity and environmental persistence, comprehensive studies are needed to assess any potential risks associated with their use. Lastly, understanding the complex signaling networks and interactions between elicitors and plants is an ongoing challenge. Elucidating these mechanisms would enable the design of more specific and efficient elicitors and their optimal application strategies. In conclusion, chemical elicitors have emerged as valuable tools for boosting plant resistance against pathogens, pests, and environmental stresses. Their specificity, low phytotoxicity, and ease of application make them attractive options for integrated pest management and sustainable agriculture. However, addressing the considerations and challenges associated with their use is essential to maximize their efficacy and minimize potential risks. Continued research and development in this field hold promise for harnessing the full potential of chemical elicitors in promoting plant health and crop productivity.

As the field of plant resistance continues to evolve, several emerging research trends are shaping the future direction of this area. Researchers are increasingly focusing on understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying plant resistance and exploring innovative approaches to stimulate resistance in plants. One key trend is the exploration of plant immune system components, such as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI), to develop effective strategies for enhancing resistance. Additionally, there is growing interest in studying the role of plant hormones, such as salicylic acid and jasmonic acid, in modulating plant resistance responses. Furthermore, researchers are investigating the potential of microbiome manipulation to enhance plant resistance through beneficial interactions between plants and associated microorganisms.

The advent of new technologies, particularly CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, offers exciting opportunities for enhancing plant resistance [446]. CRISPR enables precise and targeted modifications of plant genomes, allowing researchers to manipulate genes involved in plant defense pathways. By engineering specific genes associated with resistance, it may be possible to develop crops with enhanced protection against pathogens, pests, and environmental stresses. CRISPR technology also holds potential for accelerating the breeding process by introducing desirable traits into crop plants, ultimately leading to improved resistance profiles [447, 448, 449]. However, ethical considerations, regulatory frameworks, and public acceptance will need to be addressed to ensure responsible and sustainable use of these technologies.

Despite significant advancements, several challenges and limitations persist in the field of plant resistance. One major challenge is the rapid evolution of pathogens and pests, which can render resistance mechanisms ineffective over time [450, 451, 452]. Developing durable resistance strategies that can withstand evolving threats remains a key priority [453, 454, 455, 456]. Another challenge lies in translating laboratory-based research findings into practical applications in agriculture [457]. Scaling up resistance-enhancing techniques and ensuring their efficacy under field conditions is crucial for widespread adoption.

Additionally, addressing the potential trade-offs between plant growth and resistance is essential to avoid compromising crop productivity [458, 459]. Finally, there is a need to consider the ecological and environmental impacts of resistance-enhancing technologies to ensure they do not disrupt natural ecosystems or harm beneficial organisms.

In conclusion, future directions in plant resistance research involve exploring emerging trends such as understanding plant immune system components, studying plant hormones and microbiome interactions, and leveraging new technologies like CRISPR for enhancing resistance. However, addressing challenges related to pathogen evolution, translating research into practical applications, managing trade-offs, and considering ecological implications will be critical in advancing the field and maximizing its positive impact on agriculture and food security.

In conclusion, this paper has explored various methods to stimulate plant resistance against pathogens and highlighted the importance of adopting integrated approaches for sustainable disease management. Throughout the discussion, several key methods have been identified as effective means to enhance plant resistance against pathogens. These methods include:

(1) Genetic approaches: Breeding resistant plant varieties through traditional breeding techniques or genetic engineering can provide plants with inherent resistance against specific pathogens.

(2) Cultural practices: Implementing proper sanitation measures, crop rotation, and intercropping can disrupt pathogen life cycles and reduce disease incidence.

(3) Chemical control: The judicious use of fungicides and other chemical agents can help manage diseases in agricultural settings. However, it is important to use these chemicals responsibly to minimize negative impacts on the environment and human health.

(4) Biological control: Utilizing beneficial organisms such as biocontrol agents, antagonistic microbes, and predatory insects can effectively suppress pathogen populations and protect plants from diseases.

It is crucial to recognize that no single method alone can provide comprehensive protection against plant pathogens. Integrated approaches that combine multiple strategies are essential for sustainable disease management. By integrating genetic, cultural, chemical, and biological control methods, farmers and researchers can develop holistic and long-term solutions that mitigate the risk of disease outbreaks. Integrated disease management not only enhances plant resistance but also minimizes the reliance on chemical inputs, reduces environmental pollution, preserves natural resources, and promotes the overall health and sustainability of agricultural systems. While significant progress has been made in understanding plant-pathogen interactions and developing resistance strategies, there is still much to learn. Further research is needed to identify new resistance mechanisms, improve the efficacy of existing methods, and develop innovative approaches for disease management.

Additionally, it is essential to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and practical implementation. Farmers, extension services, and policymakers should be encouraged to adopt and promote sustainable disease management practices. This can be achieved through educational programs, outreach initiatives, and policy support at local, national, and international levels.

In conclusion, addressing plant diseases requires a collaborative effort from researchers, farmers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers. By investing in research, implementing effective strategies, and promoting sustainable practices, we can better protect our crops, enhance food security, and ensure the long-term resilience of agricultural systems in the face of evolving pathogen threats.

RSR designed the research study. RSR performed the research. MGV provided help and advice on figures. RSR and MGV wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors would like to acknowledge Vali-e-Asr University of Rafsanjan.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.