1 Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, 1153 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

This review article explores the intricate correlation between growth factors

and bone metastases, which play a crucial role in the development of several

types of malignancies, namely breast, prostate, lung, and renal cancers. The

focal point of our discussion is on crucial receptors for growth factors,

including Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), Transforming Growth

Factor-

Keywords

- transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ)

- epidermal growth factor (EGF)

- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

- fibroblast growth factor (FGF)

- bone metastases

- targeted therapies

The process of metastases is defined as cancer cells detaching from the original or primary tumor and migrating to a distant site. Bone metastases are particularly common in certain types of solid tumors such as breast, prostate, renal and lung cancer [1]. Bone metastases represent a significant clinical challenge, and the patient suffers from pain, pathological fracture and hypercalcemia, collectively known as skeletal-related events (SREs). Despite the recent advancement in cancer treatment, bone metastases are incurable. Treatment is typically palliative, focusing on pain management, maintaining mobility, and preventing SREs. Therapies may include radiation therapy, bisphosphonates, surgery, and targeted therapies [2, 3, 4].

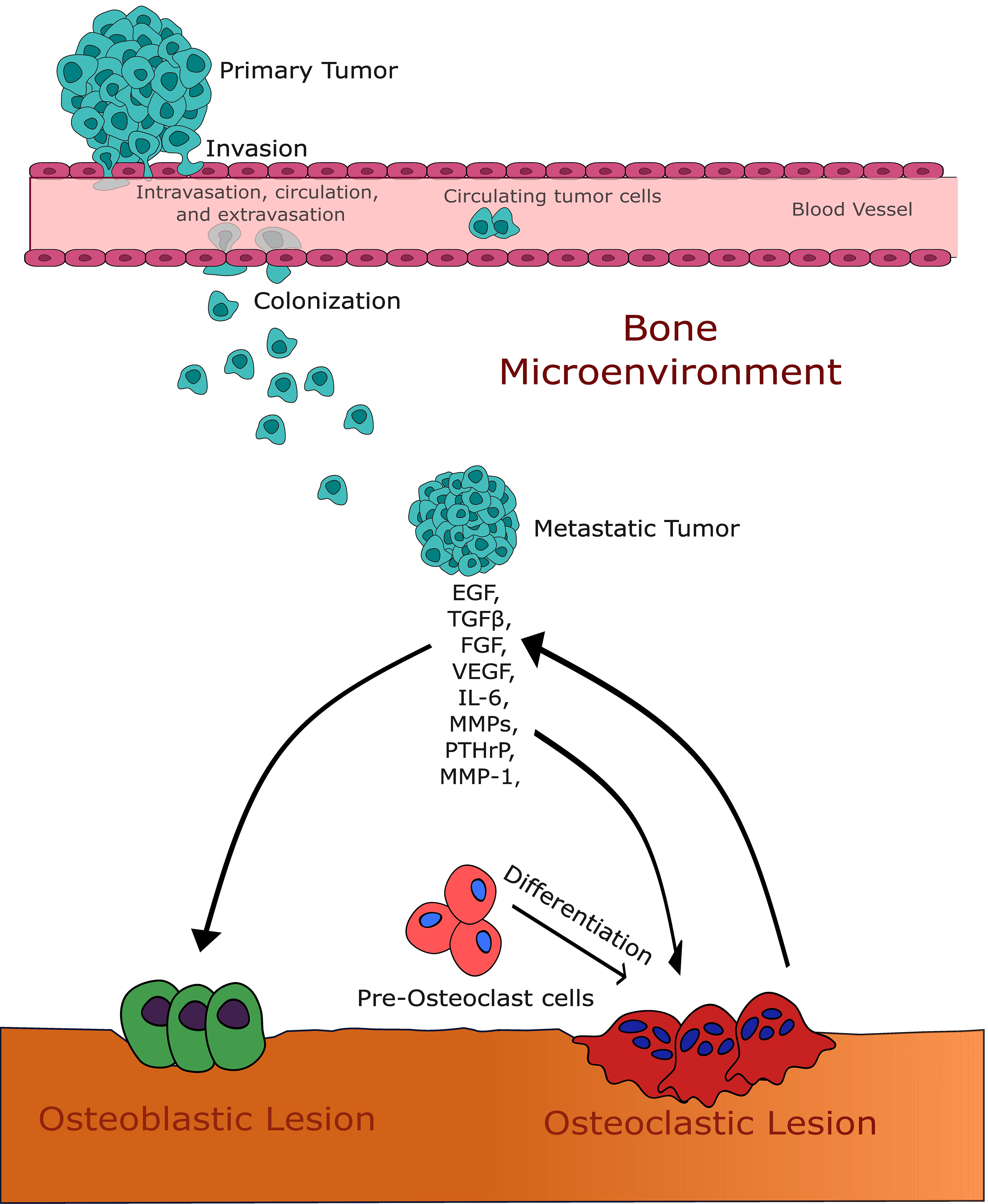

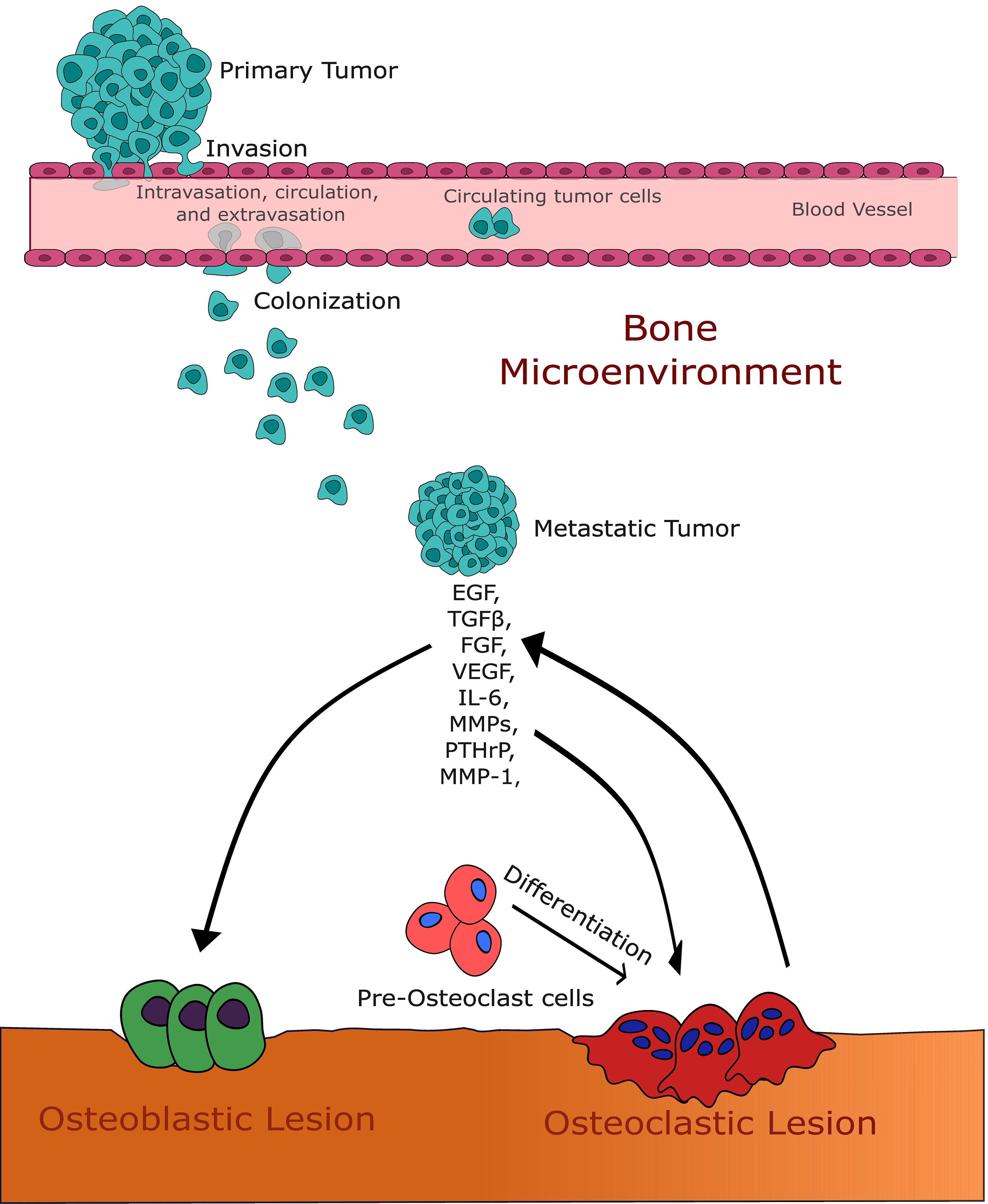

The mechanism of bone metastasis involves complex interactions between cancer cells and the resident cells of the bone microenvironment. When cancer cells seed into the bone, it disrupts normal bone remodeling and the balance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts [5, 6]. Depending on the type of cancer, metastases can lead to either osteolytic lesions (bone destruction), which are mainly seen in breast, renal, and lung cancers, or osteoblastic lesions (bone formation), commonly associated with prostate cancer. These bone lesions represent a spectrum of the disease, and mixed osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions are widely seen in X-rays in many of these cancer patients.

Growth factor receptors are integral membrane proteins that regulate cellular

processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and survival. These

receptors are especially important in bone metastases because they play a part in

the metastatic cascade and the tumor-bone microenvironment [7]. Bone metastases

occur when cancer cells from primary sites, like the breast, prostate, or lung,

migrate to the bone, a process facilitated by interactions between growth factor

receptors and their ligands. The metastatic cascade is a complex process where

aggressive cancer cells leave the primary tumor, enter the bloodstream, and form

new tumors in distant organs. The steps of the cancer metastatic cascade involve

tumor cell detachment, migration, invasion, intravasation, circulation,

extravasation, and colonization. Tumor cells detach from neighboring cells and

undergo migration either as single cells or as cell clusters [8]. They then

invade surrounding tissues and intravasate into the bloodstream [9]. Circulating

tumor cells (CTCs) travel through the bloodstream and eventually extravasate into

distant organs. Once in the new site, tumor cells establish a metastatic focus

and form secondary tumors [10]. Recent references for these steps include studies

on the signaling pathways involved in metastasis formation Growth factors like

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Transforming Growth Factor-

Recent studies highlight the significance of these growth factors in metastasis.

For instance, TGF

The EGFR family, the TGF

On the other hand, TGF

Activation of the FGFR signaling pathway impacts the bone microenvironment in

metastatic cancer by altering the interactions between cancer cells and bone

stromal cells [19]. When activated, FGFR results in elevated production of

cytokines and growth factors, like IL-6 family members, that attach to receptors

on bone stromal cells and trigger subsequent signaling pathways, such as STAT3.

Activating FGFR signaling in osteoblasts leads to elevated expression of

molecules such as receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), and osteoprotegerin (OPG). FGFR inhibitors have

been demonstrated to reduce osteoclastogenesis and tumor-induced osteolysis in a

breast cancer bone metastasis mice model [19]. VEGFR plays a significant role in

the development of bone metastases. VEGF-A and its receptors, including VEGFR-1

and VEGFR-2, are involved in both osteoclastogenesis and tumor growth [20].

Inhibition of VEGFR-2 reduces osteosarcoma cell metastatic abilities and

attenuates migration and invasion [21]. VEGFR-1 activation in tumor cells induces

cell chemotaxis and extracellular matrix invasion, contributing to tumor

progression and metastasis [5]. Targeting VEGFR-1 or VEGFR-2 expressing cells can

inhibit tumor progression in bone and reduce the number of tumor-associated

osteoclasts. Studying the growth factors in bone metastases is of utmost

importance due to their pivotal role in the progression of cancer and the

dissemination of metastases, particularly in the skeletal system. Growth factors

such as EGF, TGF

The process leading to metastatic growth of cancer in bone is regulated by a signaling interaction between the bone microenvironment and cancer cells [22, 23]. The “seed and soil” hypothesis, established by Dr. Paget [24] in 1889, posits that for optimal development, seeds need a suitable soil environment. If cancer is present, the cancer cells, referred to as “the seed”, need a suitable environment, known as “the bone microenvironment”, in order to flourish [24]. Bone is a constantly changing tissue that undergoes remodeling in response to physical and metabolic demands during an individual’s lifespan. The osteoblast, responsible for bone production, and the osteoclast, responsible for bone resorption, are the primary contributors to both bone remodeling and the development of metastases [25, 26, 27]. When tumor cells infiltrate the bone, they disrupt the usual bone remodeling process. In the case of prostate cancer, the cells promote bone formation, while in breast, lung, and renal cancer, they stimulate bone resorption [28, 29, 30, 31]. The function of the osteoclast, which is responsible for bone resorption, in the formation of bone metastases has been widely researched in recent decades. Drugs that target the osteoclast have been used to treat bone metastases and other metabolic bone diseases [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38].

Although osteoblasts and osteoclasts are primarily involved in the formation of

bone metastases, recent research has shown that many other cells residing in the

bone marrow also significantly contribute to the course of the disease

progression [39]. Adipocytes and osteoblasts share a common lineage originating

from mesenchymal progenitor cells [40]. These progenitor cells have the potential

to differentiate into either adipocytes or osteoblasts [41]. The process of

adipocyte transdifferentiation into osteoblasts has been observed in both

in vitro and in vivo experiments [42]. The prevalence of bone

marrow adipocytes increases with age and obesity [43, 44]. Dysregulation of the

osteo-adipogenic fate-determination can lead to bone diseases such as

osteoporosis, accompanied by an increase in bone marrow adipose tissue. A

definitive correlation has been established between the rise in bone marrow

adipocytes and the occurrence of bone metastases. This was shown partly by the

production of certain cytokines such as IL-6, which trigger the process of

osteoclastogenesis [45, 46]. It was also published that S100A8/A9 genes, which

are up-regulated in bone metastatic lung cancer cells, may be responsible for the

crosstalk between lung cancer cells and bone marrow adipocytes and play a role in

promoting osteolytic bone destruction in lung cancer bone metastasis [47]. There

has been growing acknowledgement of the immune system’s involvement in both

normal bone remodeling and bone disease. The bone marrow harbors a variety of

immune cell populations, each with unique roles and functions. Cells such as Natural Killer (NK)

cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and neutrophils all contribute to the

complex immune landscape of the bone marrow. These different cell populations

have specialized functions that contribute to the overall defense mechanisms of

the bone marrow against various immunological challenges. For example, NK cells

have the ability to directly attack and eliminate cancer cells and thus represent

an important line of defense against malignancies [48, 49]. Macrophages, on the

other hand, have the ability to adopt different phenotypes depending on the

specific context in which they are activated. They can adopt either a

proinflammatory (M1) or a tumor-promoting (M2) phenotype, underlining their

versatility. The M2 macrophage subtype, also known as tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs), emerges as a significant contributor to tumor progression

within the bone marrow microenvironment [50, 51]. These M2 macrophages actively

participate in the promotion of tumor growth, including the establishment of bone

metastasis. It was demonstrated that upon arriving at the tumor site, monocytes

initially differentiate into motile TAMs. These TAMs, guided by CCR2 signaling,

subsequently undergo a TGF

Moreover, the bone marrow is also home to other immune cell populations, such as

MDSCs and neutrophils, which play crucial roles in both immune suppression and

tumor growth. MDSCs are derived from the myeloid lineage and function to suppress

immune responses. They possess immunosuppressive properties that contribute to

the evasion of immune surveillance by tumors [53, 54]. Additionally, neutrophils,

another significant cell population within the bone marrow, also exhibit

functions related to immune suppression and tumor growth. These immune cells can

be influenced by various factors, including the cytokine TGF

Bone metastases, often arising from primary tumors such as breast, prostate, and

lung cancers, pose significant clinical challenges because of their ability to

disrupt normal bone homeostasis, leading to SREs [59, 60, 61]. The rationale for

targeting GFR pathways in this context stems from their pivotal role in mediating

tumor growth and metastatic progression. Growth factor receptors, including the

EGFR, TGF

The presence of several growth factors and their corresponding receptors on tumor cells is vital for the malignant transformation and progression. Tumor cells have the ability to generate growth factor ligands and react to these signals by expressing corresponding receptors in an autocrine fashion. Tumor epithelial cells and stromal components of the tumor may interact by producing various growth factors. Tumor cells may secrete PDGF, which stromal cells including macrophages, myofibroblasts, and fibroblasts have receptors for. Stromal cells react to PDGF by secreting IGF-1, which promotes tumor development and survival. EGFR signaling is crucial in cancer growth and epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and its function is often disrupted in epithelial malignancies. A constitutively activated IGF-IR triggers cells to undergo epithelial to mesenchymal transition within mammary gland epithelial cells. This is linked to a significant increase in cell migration and invasion [62, 63].

Specifically, in the bone microenvironment, GFR signaling influences the activity of bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts, the critical cells responsible for bone remodeling [64]. Dysregulation of these pathways in cancer cells and the bone microenvironment can exacerbate osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions, leading to enhanced bone destruction or abnormal bone formation. Thus, targeting GFR pathways can disrupt these deleterious interactions, curtail tumor progression, and ease SREs. Moreover, GFR-targeted therapies may synergize with treatments like bisphosphonates or RANK ligand inhibitors, offering a more comprehensive management strategy for bone metastases. The growing understanding of molecular oncology and the emergence of precision medicine, which promises more effective and less toxic therapeutic options, also fueled the pursuit of GFR pathway inhibitors. However, the development of such therapies necessitates a nuanced understanding of GFR signaling dynamics within the bone metastatic niche, alongside considerations of drug resistance and patient-specific factors.

Following the tumor’s colonization of the bone marrow, the initiation of

micro-metastasis begins. During this phase, tumor cells release a variety of

factors, initiating osteolysis and mobilizing factors embedded within the

mineralized bone matrix [65]. This release fosters a bidirectional interaction

between the tumor cells and the bone microenvironment. A critical factor in this

process is TGF

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.This figure illustrates the intricate interaction between growth

factors and the bone microenvironment in the context of bone metastases. It

highlights the pivotal roles of transforming growth factor-

Exosomes, which are extracellular vesicles produced by all cells, play crucial roles in the development and progression of cancer. They are involved in several aspects of tumor development including tumor initiation, immune suppression, immune surveillance, metabolic reprogramming, angiogenesis, and the polarization of macrophages [68]. Exosomes can carry different types of biomolecules, including growth factors, which contribute to intercellular communication and the alteration of recipient cell behavior [69]. These exosomal contents can be transferred into recipient cells, leading to changes in cellular interactions [70]. Exosomes also have the ability to modulate components of the tumor microenvironment and influence the proliferation and migration rates of cancer cells. Additionally, exosomes can enhance or reduce cancer cell response to various types of cancer therapy including radiation therapy and chemotherapy and can trigger chronic inflammation and immune evasion [71].

Exosomes carry “cargo” and are internalized by endothelial cells to induce

angiogenesis. It was published that exosomes derived from ovarian cancer cells

affect VEGF expression in endothelial cells. It was found that these exosomes

enhance VEGF expression and secretion in endothelial cells, potentially promoting

angiogenesis. The study highlights the role of cancer cell-derived exosomes in

modifying the tumor microenvironment to favor cancer progression [72]. A recent

study provided new insights into the role of exosomes in cancer biology,

particularly in the context of tumor dormancy and the microenvironment’s role in

cancer progression. This study showed that exosomal ITGB6 from dormant lung

adenocarcinoma cells activates cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through a

KLF10 positive feedback loop and the TGF

The Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR) family represents a pivotal group of cell surface receptors crucial for regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. The history of FGFR discovery traces back to the late 1970s and early 1980s when the groundbreaking work of researchers like Michael Stoker and George Todaro identified a family of proteins called fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) that stimulated cell growth in fibroblast cultures. Following this discovery, efforts were made to elucidate the receptors through which FGFs exert their effects. In 1988, Jaye et al. [74] identified the first member of the FGFR family, FGFR1, using a combination of molecular cloning techniques. Subsequent research led to the identification of additional FGFR family members, including FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4 [75]. The discovery of FGFRs has led to several novel findings and insights into cellular signaling mechanisms. One significant discovery involves the diverse roles of FGFRs in various cellular processes beyond traditional cell growth and differentiation [76]. For instance, FGFR signaling has been implicated in cell migration, angiogenesis, tissue repair, and organogenesis, highlighting the multifaceted nature of FGFR-mediated signaling pathways. Additionally, the identification of FGFR mutations in various cancers has provided critical insights into the role of aberrant FGFR signaling in tumorigenesis [77, 78]. Furthermore, recent studies have uncovered intricate crosstalk between FGFR signaling and other signaling pathways, such as the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways, elucidating complex regulatory networks that govern cellular behavior and fate [79, 80].

A high level of diversity characterizes the FGF family, with 22 ligands found in mammals. These ligands are grouped into six subfamilies based on their sequence homology and phylogenetic relationships. There are five paracrine subfamilies and one endocrine subfamily included in this classification [75].

Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) and Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR)

Signaling is crucial in the process of bone formation and maintaining a stable

internal environment [81]. Both FGFR1 and FGFR2 activating mutations enhance

osteoblast differentiation [82]. Conversely, FGFR3 is recognized as an inhibitory

factor in bone development [83]. FGF8 was shown to impact osteoblast

differentiation in laboratory settings by influencing the differentiation of bone

marrow mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts and promoting bone formation [84].

Disruption of these signaling pathways may lead to various illnesses. Specific

skeletal defects in humans are associated with mutations in FGFR. The presence of

FGFR2 mutations in humans is linked to craniosynostosis, bent bone dysplasia, and

other skeletal diseases, suggesting its involvement in bone formation [85, 86].

In a more recent study by Shin et al. [87] they showed that in a mouse

model of Fgfr

FGF plays a pivotal role in bone metastases. Several FGF ligands have been reported to be involved in prostate cancer tumor initiation and progression. FGF1, FGF2, FGF6, FGF8, FGF19, and FGF23 have been reported to be involved in prostate cancer tumor initiation and progression [88, 89, 90]. TME-secreted FGFs play a crucial role in tumorigenesis and tumor resistance to therapy. In estrogen receptor-positive (ER+ve) breast cancer, the tumor microenvironment secretes FGF2, which is considered a major factor and has been identified as a significant factor in promoting drug resistance to anti-estrogens, mTORC1 inhibitors, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors. This resistance, which was linked to FGF2 signaling and mediated by ERK1/2 activation affecting Cyclin D1 and Bim, was reversed by targeting FGF2 or FGF receptors [91]. When ER+ve breast cancer cells were cultured in fibroblast-derived extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds, it exhibits increased ER signaling via a mechanism dependent on the MAPK pathway and independent of estrogen. This enhanced signaling is attributed to the ECM acting as a reservoir for FGF2, which binds to the ECM and promotes ER signaling. As a result, cells in the ECM environment show reduced sensitivity to ER-targeted therapies, a challenge that can be countered by inhibiting the FGF2-FGFR1 interaction [92].

In a study using 25 patient bone metastases sample, immunohistochemical analysis showed that 76% of these samples expressed FGF-8. In PC-3 prostate cancer cells, FGF-8 expression led to increased growth of intratibial tumors in mouse model and the formation of both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions. These data suggest that FGF-8 plays a major role in modulating the interactions between prostate cancer cells and the bone microenvironment, thus contributing to the development of bone metastasis [93, 94]. FGF23 is extensively expressed in osteocytes, which are the most abundant bone cells. Mansinho et al. [95], reported from a study that involved 122 patients with types of solid tumor and bone metastases treated with bone-targeted agents, that lower baseline levels of serum FGF23 are associated with longer overall survival and time to skeletal-related events (SREs). The findings suggest the potential of FGF23 as a prognostic biomarker for bone metastases and warrant further research into drugs targeting the FGF signaling pathway [95]. When MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line cultured in vitro or injected into mammary glands (without bone metastasis) exhibited weak FGF23 immunoreactivity. On the other hand, these cells showed intense FGF23 immunoreactivity when metastasized in the long bones of nu/nu mice, indicating that these cells synthesize FGF23 in a bone metastatic environment [96].

The importance of FGFR1 in bone metastases was highlighted recently by Labanca et al. [97]. This group showed that different isoforms of FGFR1 are expressed in various PCa subtypes. They reported that in an Intracardiac mouse model of bone metastases, injection of FGFR1-expressing PC3 cells led to reduced survival and an increased incidence of bone metastases. Furthermore, immunohistochemical studies on human castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) bone metastases showed significant enrichment of FGFR1 expression compared to nonmetastatic primary tumors. The study also identified an increase in the expression of ladinin 1 (LAD1), an anchoring filament protein, in FGFR1-expressing PC3 cells, which was also enriched in human CRPC bone metastases. This study highlights the novel finding that FGFR1 expression in PCa cells enhances metastatic behavior [97].

The history of the EGF and its receptor (EGFR) is marked by groundbreaking discoveries that have significantly advanced our understanding of cellular signaling and cancer biology. The story began in the late 1950s when Stanley Cohen and Rita Levi-Montalcini [98] identified a substance in mouse salivary glands that stimulated epidermal growth. This substance was later characterized as EGF, a potent mitogen capable of promoting cell proliferation and differentiation [98]. Subsequent research efforts led to the purification and sequencing of EGF, unraveling its role as a key regulator of epithelial cell growth and development. In the early 1980s, the discovery of EGFR, the receptor through which EGF exerts its effects, revolutionized our understanding of signal transduction mechanisms [99]. Michael Waterfield [100] and Antony Ullrich [101] independently identified and characterized EGFR, revealing its role as a tyrosine kinase receptor involved in mediating cellular responses to EGF and other ligands. The elucidation of the EGF-EGFR signaling pathway paved the way for numerous groundbreaking discoveries, including the identification of EGFR mutations in various cancers and the development of targeted therapies such as EGFR inhibitors [102, 103]. Moreover, recent research has unveiled novel mechanisms underlying EGFR signaling, including receptor dimerization, endocytosis, and downstream signaling cascades, providing new insights into the complexity of EGFR-mediated cellular responses and offering potential avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases.

The EGFR, sometimes referred to as erbB1 or HER1, is a constituent of the EGFR receptor family, which encompasses HER2/neu (erbB2), HER3 (erbB3), and HER4 (erbB4). EGFR functions as a receptor tyrosine kinase [104, 105]. Once the ligand binds to its receptor, the receptor is dimerized, and its cytoplasmic tails get phosphorylated, and activating several cellular signaling pathways, including the MAPK pathway, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT pathway, and the STAT pathway. This pathway activation can lead to an increase in cell proliferation, migration, and survival [106]. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) mutations of the EGFR genes is considered a major driver of the disease [107, 108]. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) has a high incidence rate and a poor prognosis because of late diagnosis and the absence of effective therapy [109]. Overexpression of the EGFR is commonly associated with pancreatic cancer progression, but its correlation with survival rates remains unclear [109, 110]. Although it is shown that EGFR plays an important role in the pathogenesis of pancreatic ductal carcinoma, its overexpression is associated with poor prognosis. On the other hand, EGFR somatic mutations are not typically common in pancreatic cancer and EGFR mutations in pancreatobiliary tumors are primarily loss-of-function mutations and are not responsive to anti-EGFR treatment [111].

Several EGFR-targeting agents for the treatment of various human cancer types have been in clinical development. This includes anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab and reversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib and erlotinib. Some have been approved to treat several types of cancer [112, 113, 114]. In a study analyzing data from 295,213 patients with invasive breast cancer covering the period from 2010 to 2014, it was found that at diagnosis, bone metastases occurred in 3.28% of newly diagnosed breast cancers. This was the highest incidence rate among the studied metastatic sites, which also included lung (1.52%), liver (1.20%), and brain (0.35%) metastases. The HR+/HER2- subtype was associated with an elevated risk of bone metastases compared to HR+/HER2+. The triple-negative subtype (HR-/HER2-) was associated with a significantly lower risk of bone metastases compared to HR+/HER2- tumors [115].

A study aimed to determine the prevalence of ERBB2/HER2 mutations in bone metastases of breast cancer and the associated phenotypes. A total of 231 breast cancer patients with bone metastases were analyzed. It was found that 7 out of 231 patients (approximately 3%) with bone metastases had gain-of-function mutations in the ERBB2/HER2 gene. All reported cases with the HER2 mutation were HER2-ve based on conventional testing for protein expression and gene amplification, indicating a potential oversight in identifying candidates for specific anti-HER2 therapies [116].

EGFR mutations are presently utilized as predictive markers of clinical response to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs); these mutations can cause amplification and overexpression of the EGFR protein and other carcinogenic mechanisms of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity abnormality [117]. Mutations in EGFR and kRAS genes are linked to overall survival in NSCLC patients with symptomatic bone metastases. In 139 patients with NSCLC treated for symptomatic bone metastases between 2007 and 2014, with known mutation statuses, it was reported that patients with EGFR mutations, comprising 15% of the study population, had a significantly longer median OS of 17.3 months. In contrast, patients with kRAS mutations, making up 34% of the study population, had a much shorter median OS of only 1.8 months. Compared with patients who were EGFR-positive, those who were EGFR-negative had a 2.5 times higher risk of death. This data highlights the significant impact of EGFR and kRAS mutations on the overall survival of NSCLC patients with symptomatic bone metastases [118].

In metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients who had failed androgen-deprivation therapy and received docetaxel chemotherapy, circulating tumor cells (CTCs) were enumerated and EGFR expression was also assessed. Among patients with five or more CTCs, 40.5% (15/37) were found to have EGFR-positive CTCs. Patients with EGFR-positive CTCs had a notably shorter overall survival of 5.5 months compared to 20.0 months in those with EGFR-negative CTCs. The study concluded that EGFR expression in CTCs is a crucial factor in assessing response to chemotherapy and predicting disease outcome [119].

The receptor activator of Nuclear Factor

When EGFR mutations were compared between primary lung adenocarcinoma tumors and corresponding bone metastases, EGFR mutations were found in 61 primary tumors (53.04%) and 67 corresponding metastases (58.26%). The consistency of EGFR mutations between matched BMs and primary tumor samples was 80.87%, while the disparity was 19.13% suggesting that both primary tumor and metastatic sites should be considered for EGFR mutation testing to guide treatment decisions effectively [124].

The history of TGF

The multifunctional cytokine known as Transforming Growth Factor-

In many cases, tumor cells find ways to circumvent TGF

TGF

A complicated interplay between TGF

The history of VEGF and its receptors represents a cornerstone in our understanding of angiogenesis and vascular biology. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, pioneering work by researchers including Napoleone Ferrara [149] and Harold Dvorak [150] led to the identification and characterization of VEGF as a potent angiogenic factor. This discovery revolutionized our understanding of how new blood vessels form and grow [151, 152]. Subsequent research efforts focused on unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying VEGF signaling, leading to the identification of several VEGF receptor isoforms, notably VEGFR-1 (Flt-1), VEGFR-2 (KDR/Flk-1), and VEGFR-3. These receptors, primarily expressed on endothelial cells, mediate the biological effects of VEGF through intricate signaling pathways [153]. Novel discoveries in recent years have elucidated additional roles of VEGF and its receptors in various physiological and pathological processes, including lymphangiogenesis, vascular permeability, and tissue repair. Moreover, the identification of VEGF receptor mutations and alternative splicing variants in diseases such as cancer has opened new avenues for targeted therapies aimed at disrupting pathological angiogenesis [154, 155].

Since the isolation of VEGF and its identification as a potent mitogen for endothelial cells, VEGF has been proven to be crucial in vasculogenesis during embryonic development and angiogenesis in embryonic, postnatal, and adult instances like wound healing and female reproductive cycles [156, 157]. VEGF’s primary receptors are VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) and VEGFR-2 (KDR) [158, 159]. VEGFR-2 has greater signaling activity than VEGFR-1 and is the main mediator of VEGF’s mitogenic effects, despite a lower binding affinity [158]. Elevated levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) have been observed in a range of tumors, both benign and malignant. This includes various cancer types, such as melanoma, kidney cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer and others [160, 161].

Tumor neovascularization is critical for their proliferation and sustenance.

VEGF is a major tumor proangiogenic factor that is upregulated during tumor

growth [162, 163]. Hypoxia is a potent stimulator of VEGF expression.

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 or HIF-1 is known to be the regulate over 60

downstream genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [164]. High

levels of HIF-1

Biopsy samples from patients with SCLC were examined using IHC, a significant

correlation between HIF-1

In an in vitro experiment using conditioned medium from a prostate cancer cell line (C4-2B), which is rich in VEGF, showed the induction of osteoblast differentiation as well as the production alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin which are bone formation markers. They found that the use of VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor PTK787 blocked these osteoblastic activities induced by the conditioned medium and reduced the bone lesion in prostate cancer mouse model suggesting the important role of VEGF in prostate cancer bone metastases [170]. When renal cell carcinoma cell line (RCC-Luc) was compared to breast and prostate tumor cell lines, it was found that vegf-a expression is 10-fold more in RCC cells. When tested in vivo, it was shown that the bone metastatic nature of this cell line is independent of tumor vascularity [171]. The most important findings on the role of growth factors in bone metastases are summarized in Table 1.

| Growth Factor Receptor | Role in Cancer and Bone Metastases | Key Findings |

| FGFR | Crucial for cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. FGFR mutations in various cancers indicate aberrant signaling in tumorigenesis. | FGFR1 and FGFR2 mutations enhance osteoblast differentiation, whereas FGFR3 inhibits bone development. FGF ligands, notably FGF1, FGF2, FGF6, FGF8, FGF19, and FGF23, play roles in tumor initiation and progression in prostate cancer and drug resistance in ER+ve breast cancer. FGF8 and FGF23 specifically implicated in bone metastases. |

| EGFR | Key regulator of epithelial cell growth. EGFR mutations associated with various cancers and targeted therapies. | EGFR overexpression is linked with pancreatic cancer progression and poor prognosis. EGFR mutations serve as predictive markers for clinical response. EGFR-positive CTCs in mCRPC associated with shorter survival. EGFR signaling promotes osteoclast formation and is important in bone remodeling. |

| TGF |

TGF |

TGF |

| VEGFR | Critical for angiogenesis and vascular biology. VEGF and its receptors play roles in various physiological and pathological processes. | VEGF signaling is crucial for tumor neovascularization and sustenance. High levels of HIF-1 |

FGFR, Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor; EGFR, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor;

TGF

AZD4547 is a specific inhibitor of the FGFR1, 2, and 3 tyrosine kinases. AZD4547 effectively decreased the activity of recombinant FGFR kinase in laboratory conditions and inhibited FGFR signaling and proliferation in tumor cell lines that exhibited an abnormal expression of FGFR [172]. The efficacy of the selective FGFR inhibitor, AZD4547, has been studied in the bone microenvironment. In an orthotopic breast cancer bone metastasis mouse model, AZD4547 suppressed osteoclastogenesis and tumor-induced osteolysis, indicating its potential to suppress both tumor and stromal components of bone metastasis. This data suggests that AZD4547 can be a potential therapeutic agent for metastatic bone disease in breast cancer [19]. AZD4547 was tested in a PDX model of pancreatic cancer bone metastases. Before drug testing, the PDX model of pancreatic cancer bone metastases showed significant FGFR1 expression. AZD4547 reduced growth better than capecitabine, a chemotherapeutic medication. The two synergistically increased total growth inhibition (TGI) by 70.5%. In addition, AZD4547 reduced tumor cell proliferation and FGFR1 targets like p-Akt expression [173]. The researchers did not explain AZD4547’s mechanism of action, and more studies are necessary to establish this mechanism.

Over the last two decades, two primary targeted therapeutics have been discovered to inhibit HER-driven pathways: small molecule drugs that reduce intracellular tyrosine kinase activity and mAbs that target the extracellular domain (ECD) of the receptors. While targeted treatment has made great progress, there is still a strong need for novel therapies for HER-positive tumors. Targeted therapy using TKIs or mAbs alone may be ineffective owing to limited cytotoxicity to cancer cells as well as and poor tumor penetrance [174].

The majority of studies focused on EGFR gene alterations specifically in primary lung cancer. There is less information known about the prevalence of these genetic alterations in metastatic adenocarcinoma tumors and their impact on the effectiveness of EGFR TKIs treatment in such instances. The presence of genetic abnormalities in the cells of the primary tumor makes it highly likely that these abnormalities will also be found in the metastases [175]. The relationship between the presence of EGFR gene mutations and the occurrence of metastases, as well as their organ location, remains unknown [176, 177]. A retrospective study was conducted to investigate the relationship between patients NSCLC with bone metastases harboring and EGFR mutations and the therapeutic efficacy of EGFR-TKIs. A total of 604 patients were enrolled in the study, unfavorable progress free survival and overall survival were observed in the bone metastases versus non metastatic group [178].

In a mouse model of intratibial human NSCLC cell line H1975 bone metastases, Osimertinib alone showed a better effect on bone metastases pathology compared to Osimertinib + bevacizumab or vehicle treated mice [179]. The study demonstrates that osimertinib, both alone and in combination with BV, is effective in regressing bone metastases from EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma in a mouse model, suggesting its potential as a clinical treatment option for NSCLC patients with bone metastasis. A case report of patient with lung cancer and solitary bone metastases received osimertinib monotherapy for 12 month shows the bone metastasis to have no viable cancer cells upon pathological examination [180]. In a more recent study by Brouns et al. [181], the examination of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC who were subjected to osimertinib treatment revealed a notable observation. It was shown that at the initiation of treatment, approximately 51% of patients exhibited bone metastases. Subsequently, during the median follow-up period of 23.4 months, it was observed that 10% of patients developed new bone metastases or experienced progression of SRE, while 39% of patients encountered at least one skeletal-related event (SRE). The median overall survival (OS) subsequent to the occurrence of bone metastasis was found to improve. These findings serve to emphasize the noteworthy prevalence of bone metastases and SREs both before and during osimertinib treatment. Consequently, these findings advocate for the adoption of bone-targeted agents in this particular patient cohort, as well as the incorporation of bone-specific endpoints in clinical trials [181].

Bisphosphonates (PBs) are class of antiresorptive drugs that are commonly used in patients with bone metastases. Bisphosphonates decrease the occurrence of skeletal-related events (SREs). The data available on the use of such bisphosphonates to treat lung cancer patients with these agents are scarce [182]. Testing was done to evaluate the combined effect of bisphosphonates and EGFR-TKIs in treating NSCLC with bone metastases. The study found that bisphosphonates combined with EGFR-TKIs led to a statistically significant longer progression-free survival (PFS) compared to EGFR-TKIs treatment alone and that patients without SREs had significantly better overall survival (OS) [183].

Correctly assessing the bone lesion is crucial for patients with non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Harboring Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation. In a cohort of 45 patients treated with Osimertinib, despite the fact that some of these patients developed osteoblastic bone reaction (OBR) as accessed by x-ray, but also showed a trend toward longer skeletal related events-free survival (SRE-FS) than the non-OBR group [184]. This observation highlights that, in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC treated with Osimertinib, OBR should not be mistaken for disease progression.

The mineralized bone matrix is the largest store of TGF

Both preclinical and clinical investigations, including those focused on zoledronic acid (ZA), a class of bisphosphonates, have demonstrated that the combination of BPs and targeted systemic cancer treatments can potentially impact the prognosis of individuals with metastatic bone cancers [194]. Although tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and bevacizumab have proven to be effective in treating individuals with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (m-ccRCC), their effectiveness seems to be reduced when used to treat patients with bone metastases [195]. In order to deliver optimal care to patients with bone metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (m-ccRCC), a common approach is to administer a combination of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and bisphosphonates (BPs), with a specific focus on zoledronic acid (ZA). When administered together, TKIs and bisphosphonates can exert a stronger impact on the amount of VEGF and other potential anticancer activities. Combining these two drugs can enhance the effectiveness of the treatment, but it can also raise its toxicity [196].

Growth factor receptors, such as TGF

| Target | Agent | Effectiveness & Observations | Model/Study | References |

| FGF/FGFR | AZD4547 | Inhibits FGFR signaling & proliferation in FGFR-abnormal tumors. Suppresses osteoclastogenesis & tumor-induced osteolysis. | Orthotopic breast cancer & pancreatic cancer PDX model in mice. | [19, 172, 173] |

| EGF/EGFR | TKIs, mAbs, Osimertinib | Varied effectiveness in HER-driven pathways. Osimertinib showed notable efficacy against bone metastases in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. | NSCLC patients & mouse model of intratibial human NSCLC. | [174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182] |

| TGF |

TGF |

Inhibition of TGF |

Various cancer models & mouse model of breast and prostate cancer. | [17, 18, 61, 144, 185] |

| VEGF/VEGFR | Mouse model of breast cancer & prostate cancer, phase III METEOR trial. | [187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193] |

TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; NSCLC. non-small cell lung cancer.

Future research should focus on advancing targeted therapies against specific

growth factor receptors involved in bone metastases. This includes further

exploration of the molecular mechanisms underpinning the interaction between

tumor cells and the bone microenvironment. The ‘vicious cycle’ of bone

destruction and tumor growth, driven by factors like parathyroid hormone-related

peptide and transforming growth factor

To effectively address the future directions concerning growth factors involved

in bone metastases, it is of utmost importance to concentrate on individual

growth factors and their specific functions. For example, the targeting of

Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF

Another critical area for future research is the development of novel modalities for predicting and monitoring treatment responses in bone metastases. This entails not only refining existing therapeutic approaches but also discovering biomarkers that can precisley predict the efficacy of targeted therapies. Emphasizing personalized medicine, research should aim to tailor treatments based on individual patient profiles, considering the specific growth factor receptor pathways active in their cancer. Future research should also emphasize the intricate interplay among these growth factors, exploring combination therapies that target multiple pathways to enhance the effectiveness of treatment and overcome resistance.

In conclusion, our expedition through the realm of growth factors and bone metastases marks not an end, but a beginning. It beckons a future where the intricacies of molecular interactions are not just understood but harnessed, where targeted therapies become not just a possibility but a reality, and where the specter of bone metastases is met with not just hope but tangible, effective treatments. As we approach these groundbreaking advancements, our determination grows stronger, our curiosity intensifies, and our commitment to overcoming this significant challenge remains steadfast. This manuscript, therefore, serves as both a testament to our current understanding and a clarion call to the scientific community: the journey continues, and the fight against bone metastases marches on, fueled by innovation, perseverance, and the unyielding spirit of scientific discovery.

KSM and SAA, Conceptualization, writing, and editing. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.