1 Biocompatibility Innovation Srl, IT-35042 Este, Padua, Italy

2 Avantea, IT-26100 Cremona, Italy

3 Mountain Hawk Consulting LLC, Glen Allen, VA 23059, USA

Abstract

Background: Recent studies highlighted the presence of

anti-

Keywords

- α-Gal antigen

- bioprosthetic heart valves

- calcification

- knockout mouse model

- GGTA1-/-

- CRISP/Cas9

- xenograft

Cardiovascular diseases rank among the primary causes of mortality globally and

addressing them appropriately continues to be a significant challenge in clinical

practice. Among these, calcific aortic valve disease represents one of the most

challenging issues worldwide with a high associated mortality rate that of 41%

and 52% after 5 years, for mild and severe aortic stenosis respectively. Due to

a lack of approved pharmaceutical treatments, the only usable clinical approach

is the surgical replacement of the valve with prosthetic heart valves [1, 2, 3].

Among the various options, the most used involves the implantation of

bioprosthetic heart valve (BHV) substitutes, usually made of pericardial tissue

of bovine or porcine origin [4]. Such BHVs are fixed with glutaraldehyde (GA) for

the improvement of the mechanical properties, assuring sterility and stability,

as well as the reduction of immunogenicity. These devices are usually implanted

in older people (

The

The choice to use rats or mice for in vivo biomaterial assessment, is a common practice, due to their cost-effectiveness, ready availability, manageability, and clearly defined immunological patterns. These animals are frequently employed to study the chronic changes that affect contemporary or novel BHVs’ leaflets when placed in a subcutaneous dorsal area. Specifically, the subdermal model guarantees a good serum and blood exposition of the implant ensuring cellular migration and enabling a reliable evaluation of anti-calcification treatments [14, 15].

Nevertheless, implanting BHV leaflets (mainly sourced from bovine or porcine

pericardium) into a wild-type (WT) mouse represents a concordant

xenotransplantation scenario with respect to the

This study described the creation of a knockout (KO) mouse, genetically modified

to be

The primary target of the experimentation was to estimate calcium deposition in

isolated leaflets from a surgical commercial BHVs of bovine pericardial origin

implanted for 1, 2, and 4 months in GGTA1 KO mice, comparing it with an

investigation conducted simultaneously in WT mice. Moreover, the possible remnant

All surgical and experimental procedures conducted on animals followed the guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as issued by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication 85-23, revised 1996). The utilization of a mouse animal model for experimental purposes received approval from the Italian Ministry of Health under project registration number 17E9C.154 and authorization number 542/2020-PR. The GGTA1 KO mouse animal model is the property of BCI - Biocompatibility Innovation Srl (Este, Padua, Italy). The model generation process was conducted in cooperation with Polygene Transgenetic (Rümlang, Switzerland), and the animals are presently homed at Charles River Laboratories Italia (Lecco, Italy).

To knockout the GGTA1 gene, the CRISP PolyGene I139 (PolyGene, Rümlang, Zürich) construct was used. The target exon of the intended gene was Ggta1-202_3. gRNAs for GGTA1 were designed using the publicly available algorithm from the Institut des Neurosciences [19]. The algorithm returned several possible guides, but only the two with the best specificity were chosen and used.

ES cell lines used in the generation of chimeras were validated by STR profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. 12000 ES cells were plated onto 6 cm plates and lipofected with 1 µg of both guide plasmid and the homology oligo in each region (Lipofectamin LTX, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Following a 24-hour incubation period, the cells underwent a 48-hour selection phase with 0.8 µg/mL puromycin. This selection aimed to isolate cells expressing the guide/Cas9 plasmids temporarily. Subsequently, after an 8-day interval, 48 clones were chosen from each guide. These selected clones, exhibiting visibly reduced amplicon sizes during Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) screening, were then expanded into a 24-well plate and cryopreserved at –80 °C. Further validation included retesting through PCR and sequencing. Despite a low yield of clones displaying visible deletions, six potential candidate clones were successfully identified. PCR was performed on the obtained clones using these primers:

I139.5 5

I139.6 5

The screening PCR utilizing primers I139.5/6 produces a 436 bp wild-type amplicon, a size conducive to detecting small deletions while still allowing for the identification of deletions within the range of 2–300 bp. Upon sequencing the candidate clones, the following results were obtained:

• Clone 3C8: 34 bp deletion and Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH)

• Clone 3C12: wild type

• Clone 3D7: 71 bp deletion and wild type

• Clone 4E3: 110 bp deletion and LOH

• Clone 4E7: 75 bp deletion/2 bp deletion

• Clone 4E8: 32 bp deletion and LOH

It is noteworthy that LOH, resembling homozygosity, is often misconstrued as such in CRISPR generation. In the mentioned cases, it is evident that distinct variants/mutations are highly improbable to occur simultaneously on corresponding alleles, suggesting a preferential amplification of the mutant and thus seemingly mutant-specific sequence information. Notably, it appears that the wild-type band, or at least a band of similar size to the wild type, is present in 3C8, 4E3, and 4E8, even if with a weaker intensity.

Nominee clones were inoculated into C57Bl/6Ng blastocysts with high effectiveness. The procedure allows 80–100% chimeric males to be obtained from each litter born in three of the clones used. To evaluate germ line transmission 11 of the chimera mice resulting from blastocyst inoculations were paired with C57Bl/6Ng mice. Since 3C8 mice did not breed satisfactorily, it was decided not to pursue this further and focus on more successful breeding clones. Additionally, the deletion size in 3C8 appeared less appealing. Interestingly, mice from 3D7 exhibited segregation into two sublines, one with a characterized 71 bp deletion and another with an 18 bp deletion. All pups displayed either of the deletions, indicating a clean heterozygous configuration. The 18 bp deletion, located within exon 4 but 55 bp downstream of the start of the 71 bp deletion, was not visible in the overlap PCR. Despite its small size, the 18 bp deletion was challenging to identify on the agarose gel. Consequently, it was initially mistaken for the 2 bp deletion in clone 4E8, leading to breeding; however, all corresponding mice were later eliminated. Subsequent inspection clarified that 4E8 had not produced chimeric offspring. Screening for deletions utilized primers I139.5 and I139.6. Clone 3D7 (bearing 71 bp deletion) and clone 4E7 (bearing 75 bp deletion) were bred with high productivity and showed a Mendelian distribution in D71 (20/42 mice; all others D18) and D75 (23/40). Numerous pairs of D71 and D75 mice were established for breeding to generate homozygous F2 mice. A total of 227 F2 mice were generated, with 152 from the D71 and D75 breedings. The ratios in these mice were fairly accurate Mendelian ratios, suggesting no discernible effect on development or viability for the mutant heterozygous or homozygous genotypes. To reaffirm the genotypes, several homozygous mice were sequenced using the I139.5/6 PCR and I139.5 as a Sanger sequencing primer, corroborating the sequencing data obtained in ES cells.

Around 100 mg wet weight of fresh tissue samples from different organs of both

WT and KO mice were collected. Samples were then incubated with [1:50] M86

primary anti-

100 µL of

The signal was obtained by adding 100 µL per well of horseradish peroxidase substrate buffer incubated for 5 min and by reading the absorbance at 450 nm with Multiscan Sky plate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Epitope number calculation was generated with a calibration line obtained using rabbit red blood cells [21].

GGTA1

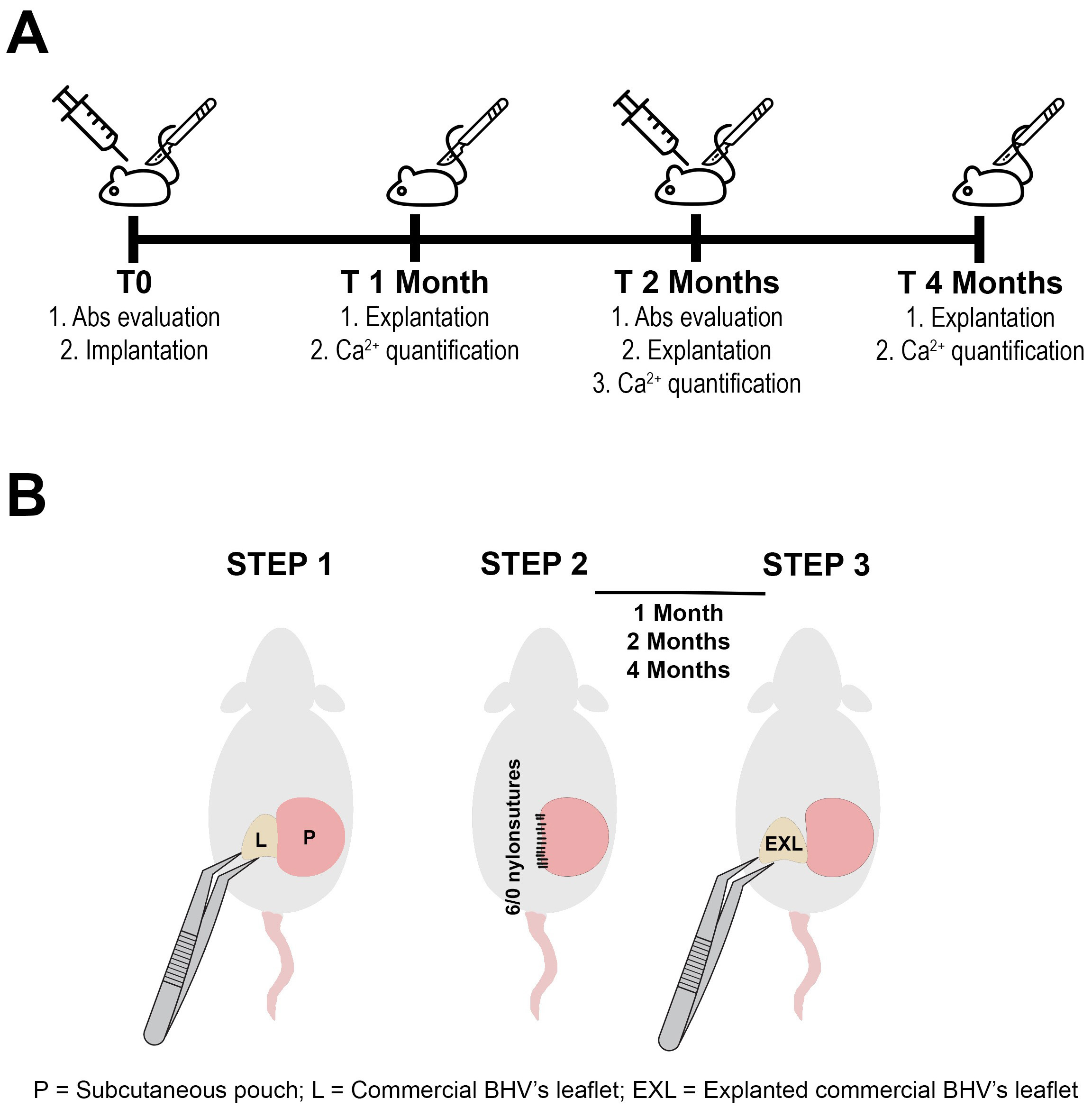

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Experiment timeline and schematic implant procedure. (A) Study timeline (Abs = antibodies). (B) Schematic representation of subcutaneous surgical implant of commercial BHV’s leaflet. BHV leaflets (L) were inserted in a subcutaneous pouch (P) in the dorsal area of the animal (STEP 1). Puoch was sutured with 6/0 nylon (STEP 2). Explanted commercial BHV leaflets (EXL) were carefully harvested after 1, 2, and 4 months of incubation (STEP 3). BHVs, bioprosthetic heart valves.

IgM and IgG anti-Gal antibodies in the serum of KO mice were assessed both

before and 2 months after BHV’s leaflet implantation using an ELISA test.

Approximately 0.75 mL of blood per mouse was collected through infraorbital

venous plexus sampling (n = 10). A Polysorp 96-well plate (Nunc) was coated with

100 µL of

Leaflets of the tested BHV were carefully removed from both KO and WT animals

and washed twice in sterile cold PBS for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples

underwent acid hydrolysis in HCl 6N at 110 °C for 12 hs. Calcium

assessment in hydrolyzed samples was conducted using inductively coupled plasma

spectroscopy following EPA 6010D method’s guidelines [22] and reported as

µg Ca

The same evaluation carried out on un-implanted, off-the-shelf, valve leaflets

was taken as a control. The determination of ddw was made by comparing

lyophilized dry-weight samples before and after delipidation treatment. Following

the lyophilization step, tissue samples were incubated for 36 hs under 10 kPa

over P

Data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel® and

Prism®7 for Windows (v7.03, GraphPad Software lnc., San Diego,

CA, USA) and expressed as mean

Table 1 shows that GGTA1 gene silencing determined the inhibition of

| Tissue/Organ | % of |

KO | WT |

| Eye | 100% | 0 | 7.68 × 10 |

| Spleen | 100% | 0 | 1.70 × 10 |

| Tail | 100% | 0 | 4.13 × 10 |

| Thymus | 100% | 0 | 5.26 × 10 |

| Myocardium | 86.3% | 2.08 × 10 |

1.52 × 10 |

| Kidney | 82% | 2.76 × 10 |

1.53 × 10 |

| Lung | 80% | 5.86 × 10 |

2.93 × 10 |

| Liver | 80% | 4.10 × 10 |

2.05 × 10 |

| Skin | 44.4% | 9.55 × 10 |

1.72 × 10 |

| Brain | 44.2% | 1.87 × 10 |

3.35 × 10 |

WT, wild-type; GGTA1,

Due to food uptake during growth, KO mice develop a microbial flora expressing

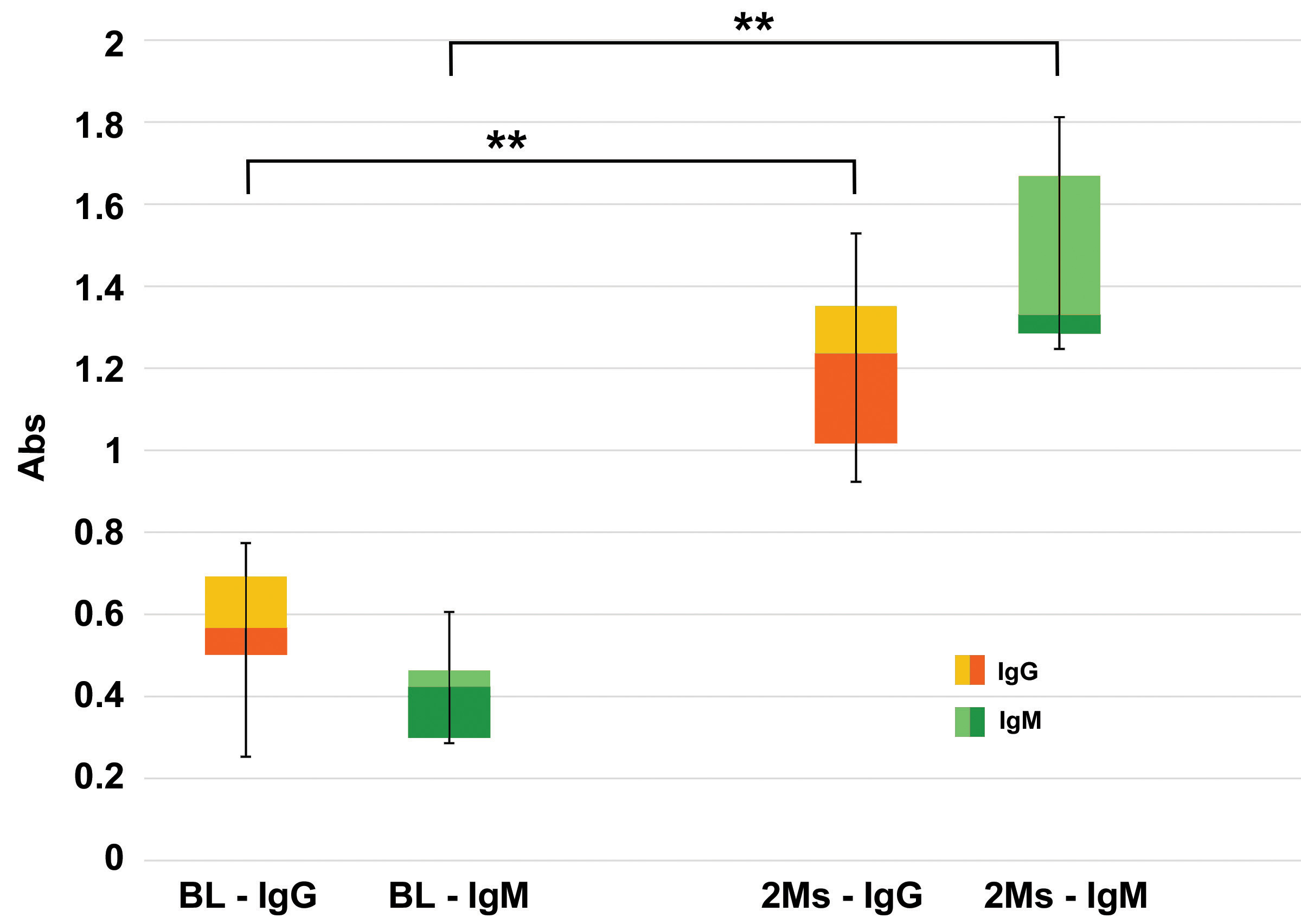

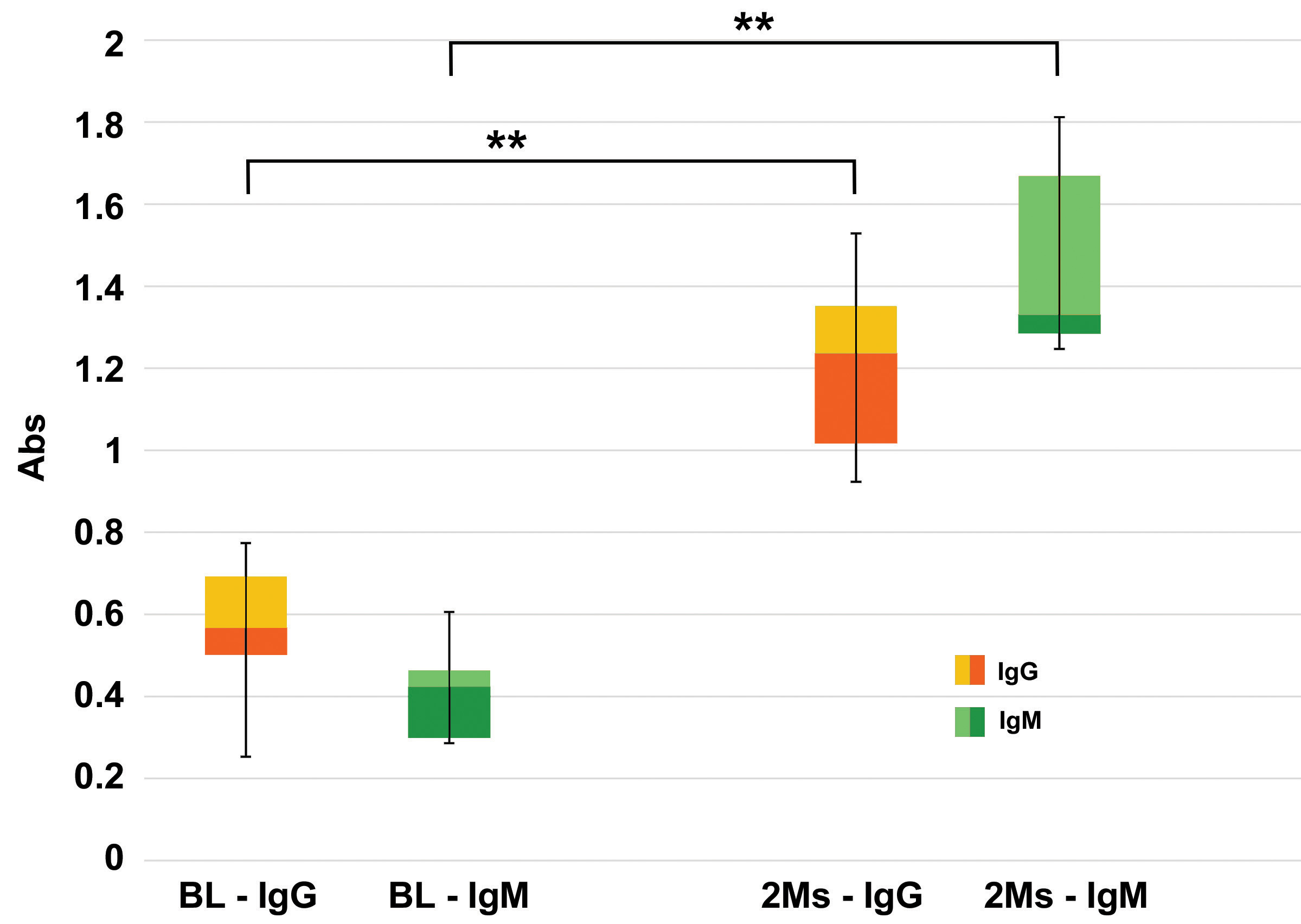

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Evaluation of anti-Gal antibodies. Quantitative evaluations of

anti-Gal IgG and IgM antibodies production in KO mice after 2 months (2 Ms) of

commercial BHVs leaflets subcutis implant compared to the basal level (BL),

evaluated before the tissue implant. Data are expressed as absorbance units (450

nm), n = 10 for each type of sample. Data points represent the means

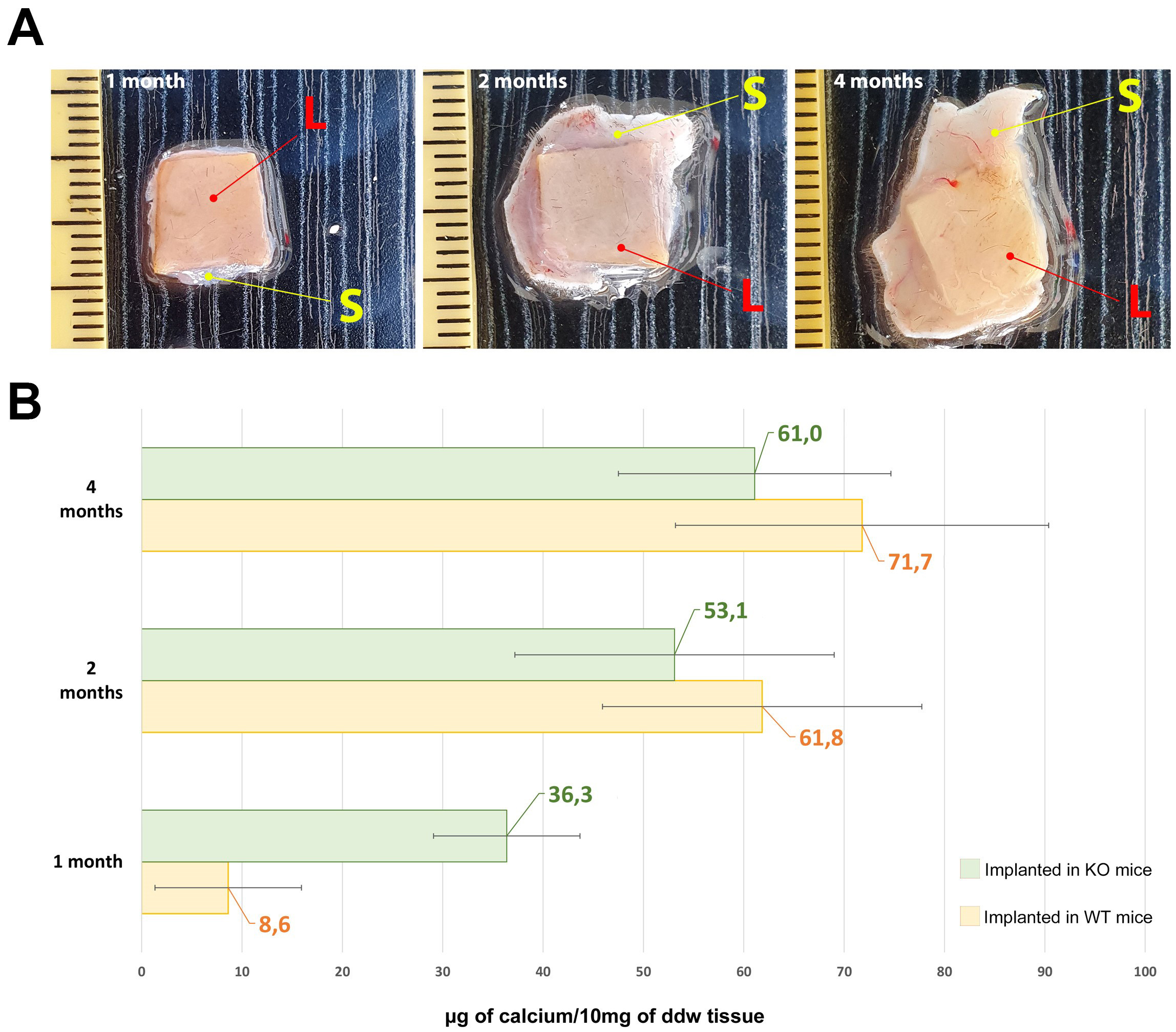

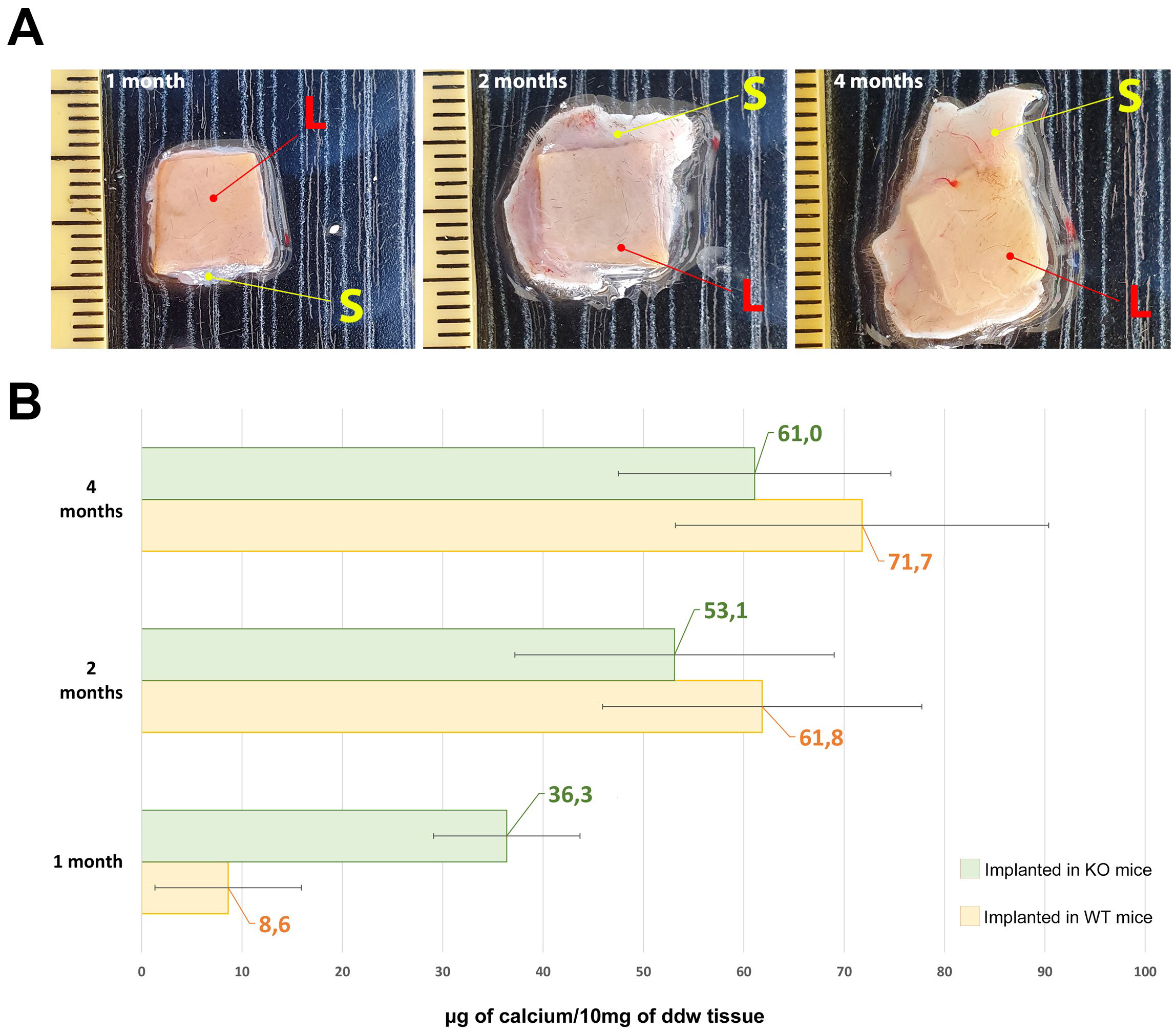

As reported by Fig. 3, the leaflets of the commercial BHV explanted from KO

mice, show a significant calcium deposition (green bar) after just one month,

surpassing more than fourfold the quantity detected in the WT mouse (yellow bar)

during the equivalent period (1 month KO vs. 1 month WT, p = 0.005).

Despite an escalation in mineralization intensity after 2 and 4 months,

significant differences were not observed between the KO and WT mice (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Calcium evaluation in explanted leaflets. (A)

Representative photos of explanted leaflet tissue after 1, 2 and 4 months of

implantation (L = leaflets; S = skin). (B) Quantitative evaluation of calcium

deposits in commercial BHVs leaflet implanted in the back subcutis area of Knockout (KO)

(green bars) and Wild-type (WT) (yellow bars) mice at 1, 2, and 4 months. As a control

sample, calcium quantification was also carried out in non-implanted

off-the-shelf commercial BHV leaflets resulting in 1.19

BHV degeneration appears as a multimodal process engaging mechanical, chemical,

and immunological pathways, leading to structural degradation over different time

frames [24]. To date, GA still represents the gold standard fixative and

sterilizing agent for almost all BHVs available on the market. Unfortunately, GA

possesses an intrinsic chemical instability that consequently leads to a host

immune response which is the first step in an articulated series of mechanisms

that result in tissue calcification. The deposition of calcium is mainly due to

the presence of the free aldehydic and carboxylic groups, which can attract

Ca

To mitigate the impact on the calcification process, BHV manufacturers have

proposed various modifications to GA fixation protocols. These modifications

include additional steps aimed at chemically stabilizing reactive chemical

groups. Processes such as GA detoxification by urazole, diamine spacer extension,

treatment with 2-amino oleic acid, or incubation in ethanol are among the

strategies developed to enhance GA stabilization, to delay calcific tissue

dystrophy [26, 27]. Besides BHV calcification, which usually occurs over a long

period (average of 10 years in

Thanks to their low cost, ready availability, ease of handling, and well-defined

immune parameters, small animal models such as rats and mice are a common and

practical choice for in vivo study of biomaterials. However, in the

majority of the cases, the selected models are WT, preventing the possible

immunological implications in the studied process. Conversely, the use of an

The GGTA1 gene, silenced in the model under investigation in this study, encodes

for

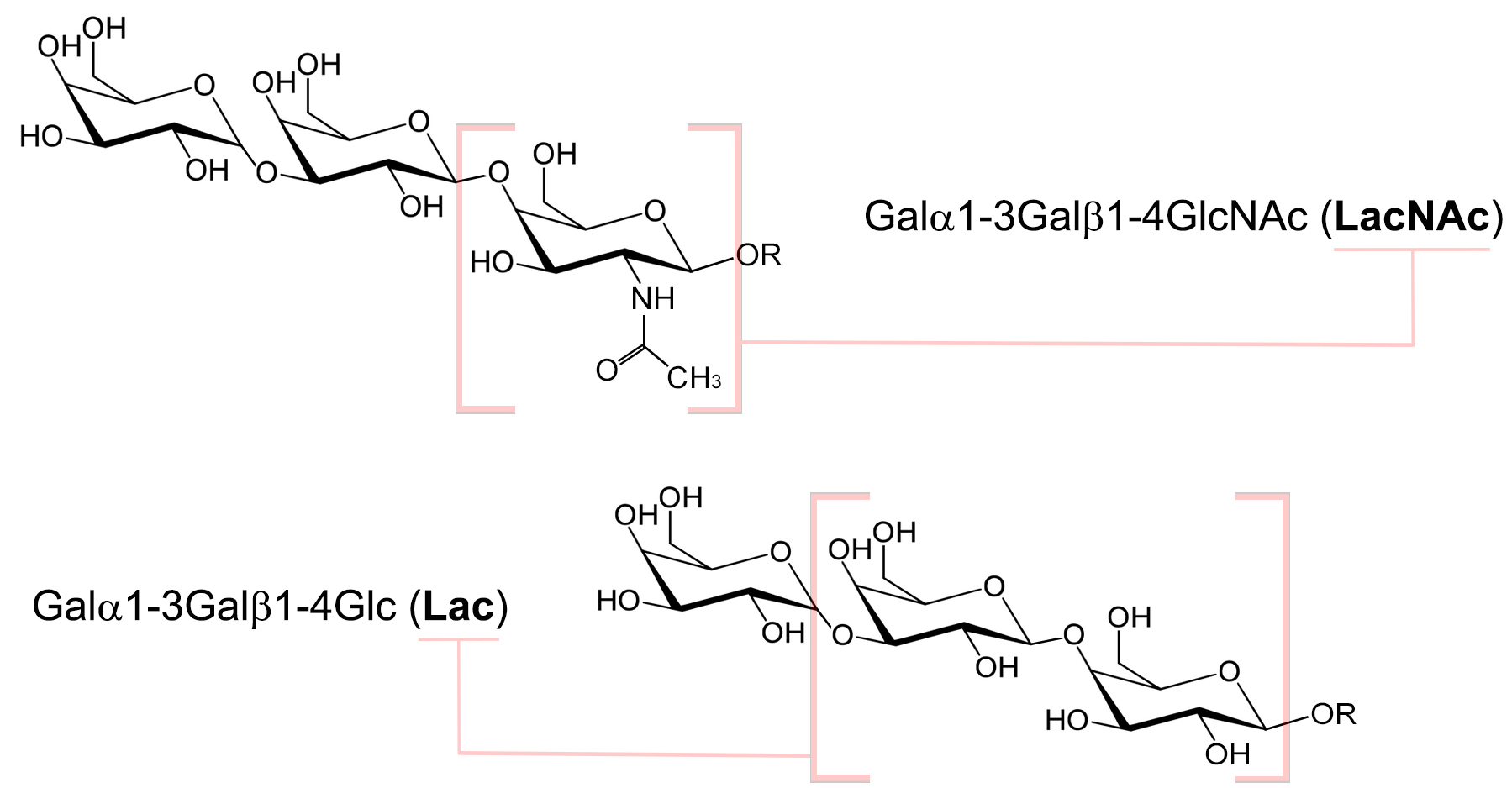

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Chemical structure of the two different types of the

From the collected data,

It is important to underline that the presence of iGb3s in the KO model is not

sufficient to trigger an immune response that involves the destruction of the

cells presenting the epitope. This fact was validated by the work of Murray and

colleagues who found that it is necessary to have a minimum basal level of

In 2016 Butler and colleagues [42] demonstrated that the silencing of the porcine

iGb3S gene did not impact assessments of expected acute rejection in pig-to-human

and pig-to-primate xenotransplantation showing that iGb3S does not play a role in

antibody-mediated rejection. The

Since other pathological conditions have been linked to variations in

circulating anti-Gal antibodies in humans, this animal model could also prove

useful for the development of novel diagnostic approaches. Our research group has

recently demonstrated a variation in the levels of circulating anti-Gal

antibodies in Alzheimer’s disease patients compared with healthy subjects [43].

Since Alzheimer’s disease is a condition in which the mechanisms are not yet

fully established and the treatments not optimized, the possibility of being able

to study it in a reliable animal model seems promising and could open new

diagnostic rather than curative approaches. In addition, Dahl and colleagues [44] have

seen that GGTA1 KO mouse models show glucose intolerance and reduced pancreatic

Given the increasing attention being focused on

Small animal models, such as mice and rats have been widely used for years as a reliable tool for in vivo assessment of calcification propensity of biomaterials through subcutis implantation. This approach is technically easier and cheaper than implanting entire bioprostheses in large animals moreover, mice present an accelerated calcium metabolism that can mimic what is observed in clinical specimens especially in young patients [54]. However, the implanted biomaterial is not subjected to continuous blood flow and pressure or to any other mechanical stress to which a BHV may be subjected that can influence the calcification response.

The implantation of commercial BHV leaflets has been shown to activate the

The authors declare that all datasets on which the conclusions of the manuscript depend are included in the study and are available to the readers.

FN and AG designed the research study. GS and FN performed the research. RM and CG analyzed the data. GS and FN wrote the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

All animal experiments and surgical procedures adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication 85-23, revised 1996). The utilization of a mouse animal model for experimental purposes received approval from the Italian Ministry of Health under project registration number 17E9C.154 and authorization number 542/2020-PR.

The GGTA1 KO mouse animal model was kindly supplied by Biocompatibility Innovation Srl.

This research received no external funding.

Alessandro Gandaglia, Giulio Sturaro, and Filippo Naso are employees of Biocompatibility Innovation Srl. Robert J. Melder is a scientific consultant for Biocompatibility Innovation Srl. Cesare Galli declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.