1 Department of Ophthalmology, University-Town Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, 401331 Chongqing, China

Abstract

Dry eye disease (DED) is a prevalent ophthalmic ailment with intricate pathogenesis and that occurs primarily due to various factors which affect the ocular surface. DED is characterized by the disruption of tear film homeostasis, inflammatory reaction, and neuroparesthesia. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is a versatile receptor that can be stimulated by heat, acid, capsaicin (CAP), hyperosmolarity, and numerous inflammatory agents. There is accumulating evidence that implicates TRPV1 in the initiation and progression of DED through its detection of hypertonic conditions and modulation of inflammatory pathways. In this article, we present a comprehensive review of the expression and function of the TRPV1 channel in tissues and cells associated with DED. In addition, we outline the potential mechanisms that implicate TRPV1 in the pathophysiology of DED. The aim of this review is to establish a theoretical basis for TRPV1 as a possible therapeutic target in DED, thereby encouraging further investigations into its role in DED.

Keywords

- review

- TRPV1

- dry eye disease (DED)

The 2017 TFOS DEWS II (Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II) report presents a comprehensive overview of dry eye disease (DED), a complex condition affecting the surface of the eyes. DED is typically associated with various eye symptoms and is characterized by altered tear film homeostasis. The primary reasons for the occurrence of DED are instability in the tear film, increased osmotic pressure, inflammation of the ocular surface, and abnormal nerve sensations [1]. The symptoms and signs of DED often differ between patients, and further research on the pathophysiology of this condition is required. Moreover, the treatment of DED has been controversial in recent years, starting first with the use of basic tear supplements [2], followed by well-studied anti-inflammatory immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporin A [3], and evolving into trials of multiple formulations [4]. A combination of physical therapy, local medication, and systemic medication can improve the quality of tear film to achieve effective treatment. However, this is becoming increasingly difficult due to the combined effects of video terminals, social environmental factors, psychological factors, etc. [5]. Several studies have reported that patients with DED experience corneal neuropathic pain, despite the apparent absence of corneal injury. This pain manifests as a spontaneous sensation of burning in the eye due to sensitivity to light, wind, heat, or cold [6, 7]. Hence, there is an urgent need for further research into the pathophysiologic mechanisms of DED.

Both ionic and osmotic abnormalities have been linked to DED. Moreover, the interplay between inflammation and ion disturbances can alter the function of ocular surface cells. The health of the cornea in DED has been investigated by studying the expression and activity of over 30 different types of ion channels, including voltage-gated, ligand-gated, mechanosensitive, aquaporin, chloride, and sodium-potassium-chloride co-transporters [8]. Increased expression or activity of Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) was recently associated with the pathogenesis of DED. Over the past 30 years, TRPV1 was shown to have crucial functions in sensing hypertonic environments and ocular surface injury, as well as in regulating inflammatory pathways. TRPV1 expression in organs and tissues associated with DED has recently attracted the attention of many researchers in this field. Although clinical trials with TRPV1-related targeted drugs have already begun for the treatment of DED [9], the relationship between TRPV1 and DED has yet to be reviewed. The aim of this paper was therefore to provide a comprehensive overview of TRPV1 expression and function in ocular tissues and cells, as well as its importance in the pathophysiology of DED. Future research directions involving the role of TRPV1 in DED will also be covered.

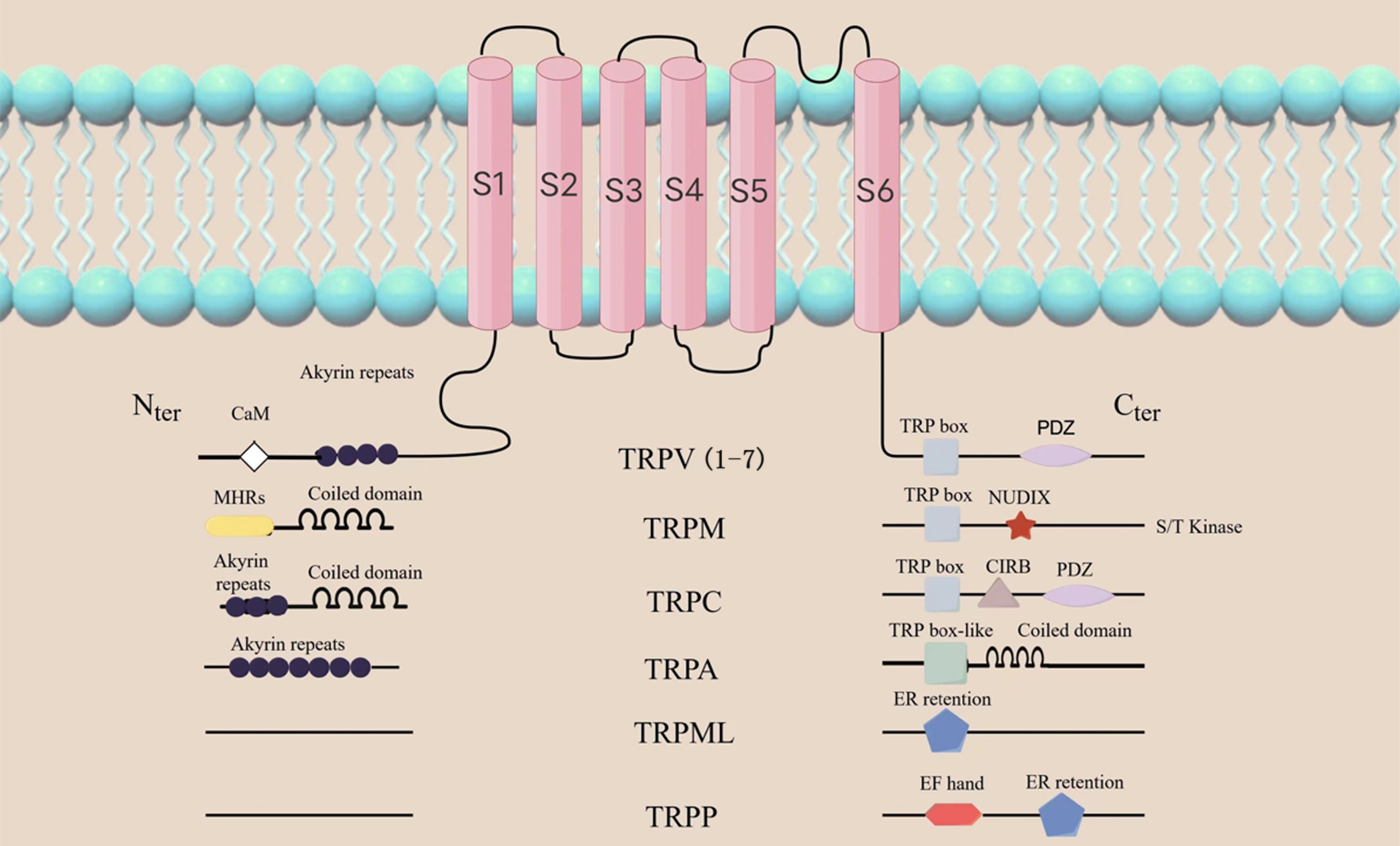

TRPV1 is one of the 7 major subfamilies of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. It is categorized amongst the TRPV subfamilies as TRPV1-7. Other subfamilies with variations in amino acid sequence, topology and function include TRP ankyrin (TRPA), TRP canonical (TRPC), TRP melastatin (TRPM), TRP mucolipin 1-8 (TRPML1-8) and TRP polycystin (TRPP). (Fig. 1) [10, 11]. TRPs are found in different tissues on the surface of the eye, including the corneal epithelium and endodermis, interstitial fibroblasts and nerve fibers, and the trigeminal ganglion (TG) [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. TRPV1 helps to maintain tissue homeostasis and initiate the wound healing response, therefore making it the most studied of all the TRP channel [17]. Similar to the structure of potassium ion channels, TRPV1 consists of six transmembrane domains (S1-S6), with four subunits surrounding the ion channel at the N- and C-terminals of the molecule (Fig. 1). Caterina et al. [18] successfully cloned and isolated TRPV1 in 1997. TRPV1 was the first neuronal receptor found to be sensitive to capsaicin, and is thus commonly referred to as the capsaicin receptor. It is also a vanillic acid compound, and is therefore also referred to as vanilloid receptor (VR1) [18].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.General topology of the TRP channel superfamily. The structure of the TRP channel is shown as in the figure,

among which TRPV1 consists of six transmembrane domains (S1-S6), with four subunits

surrounding the ion channel at the N- and C-ends of the molecule. The N-terminal contains ankyrin repeat domains, while the C-terminal

has a TRP domain and multiple calmodulin binding domains. TRP, transient receptor potential; TRPV, transient receptor potential

vanilloid; TRPM, transient receptor potential melastatin; TRPC, transient receptor potential canonical;

TRPA, transient receptor potential ankyrin; TRPML, transient receptor potential mucolipin; TRPP, transient receptor potential polycystic;

PDZ, Postsynaptic density 95 / Discs large / ZO-1 domain; NUDLX, Nucleoside diphosphate sugar transferase 9 homology domain binding ADP ribose (ADPR) or ADPR-2’-phosphate (ADPRP);

CIRB, calmodulin and inositol triphosphate receptor-binding site; EF, a canonical Ca

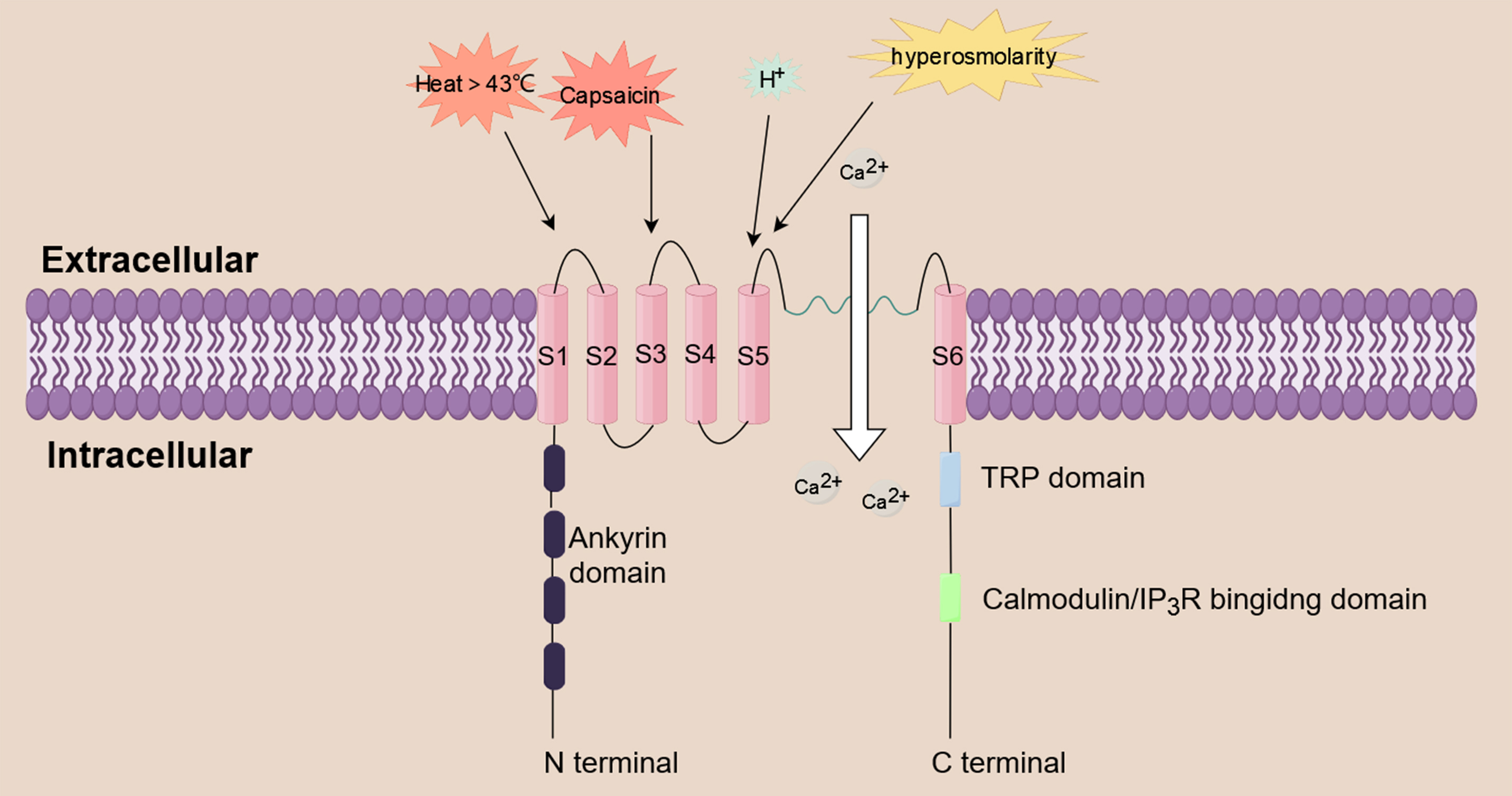

Both excitable and non-excitable cells and tissues express TRPV1 channels. These

have been linked to a number of physiological and pathological disorders, such as

pain and nociception [19]. TRPV1 is a non-selective cation channel that functions

as a multimodal nociceptor. It is triggered by a variety of substances, including

inflammatory mediators (e.g., prostaglandin, histamine), acidity, heat above 43 °C

hyperosmolarity, and capsaicin [20, 21, 22, 23]. TRPV1 can trigger a series of biological

effects by mediating the influx of extracellular cations, including Ca

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Calcium influx induced by TRPV1. TRPV1 is a non-selective

cation channel that functions as a multimodal nociceptor. It is triggered by a

variety of substances, including prostaglandin, histamine, acidity, heat above 43

°C, hyperosmolarity, and capsaicin. TRPV1 triggers a series of biological effects

by mediating the influx of extracellular Ca

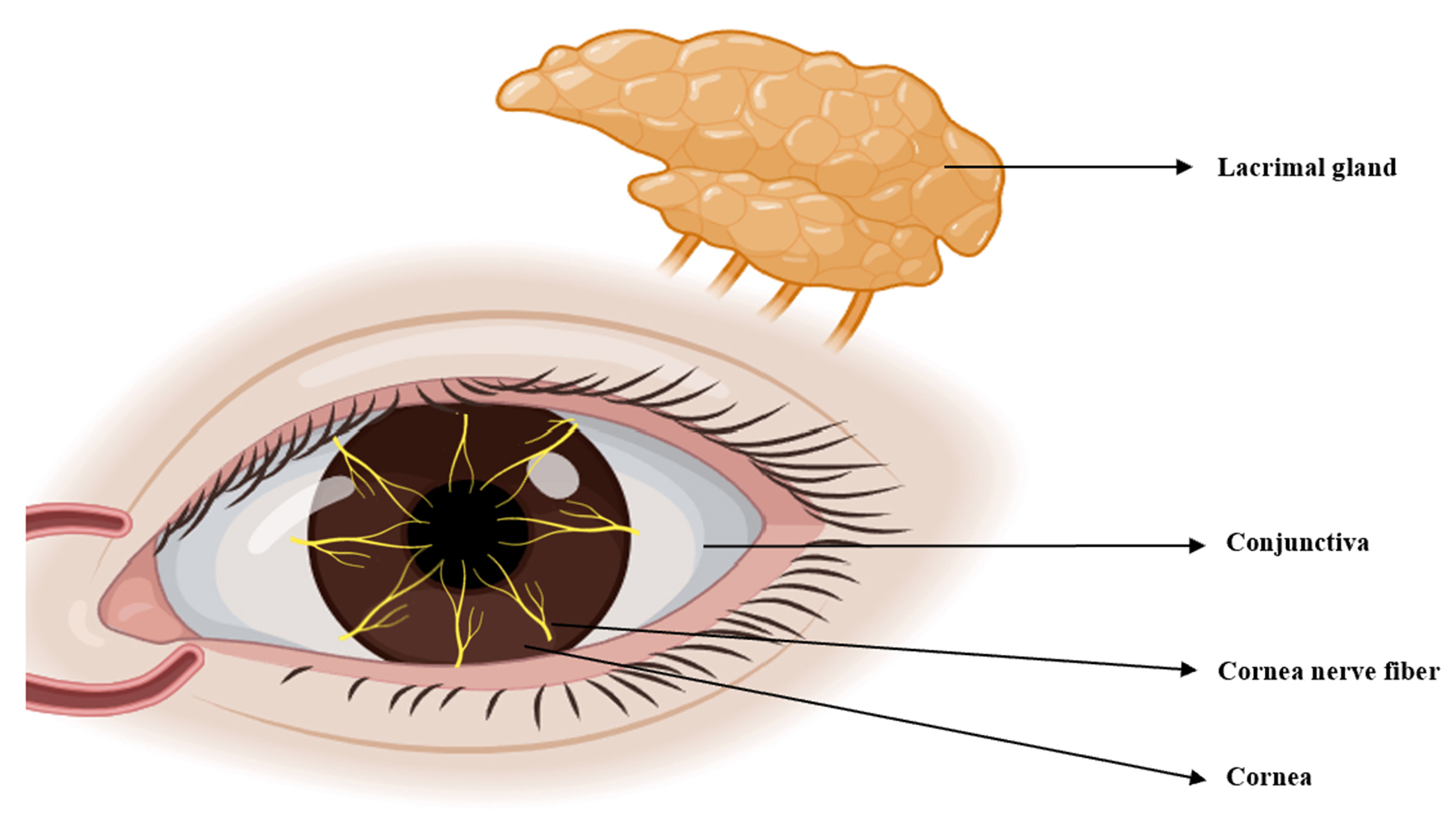

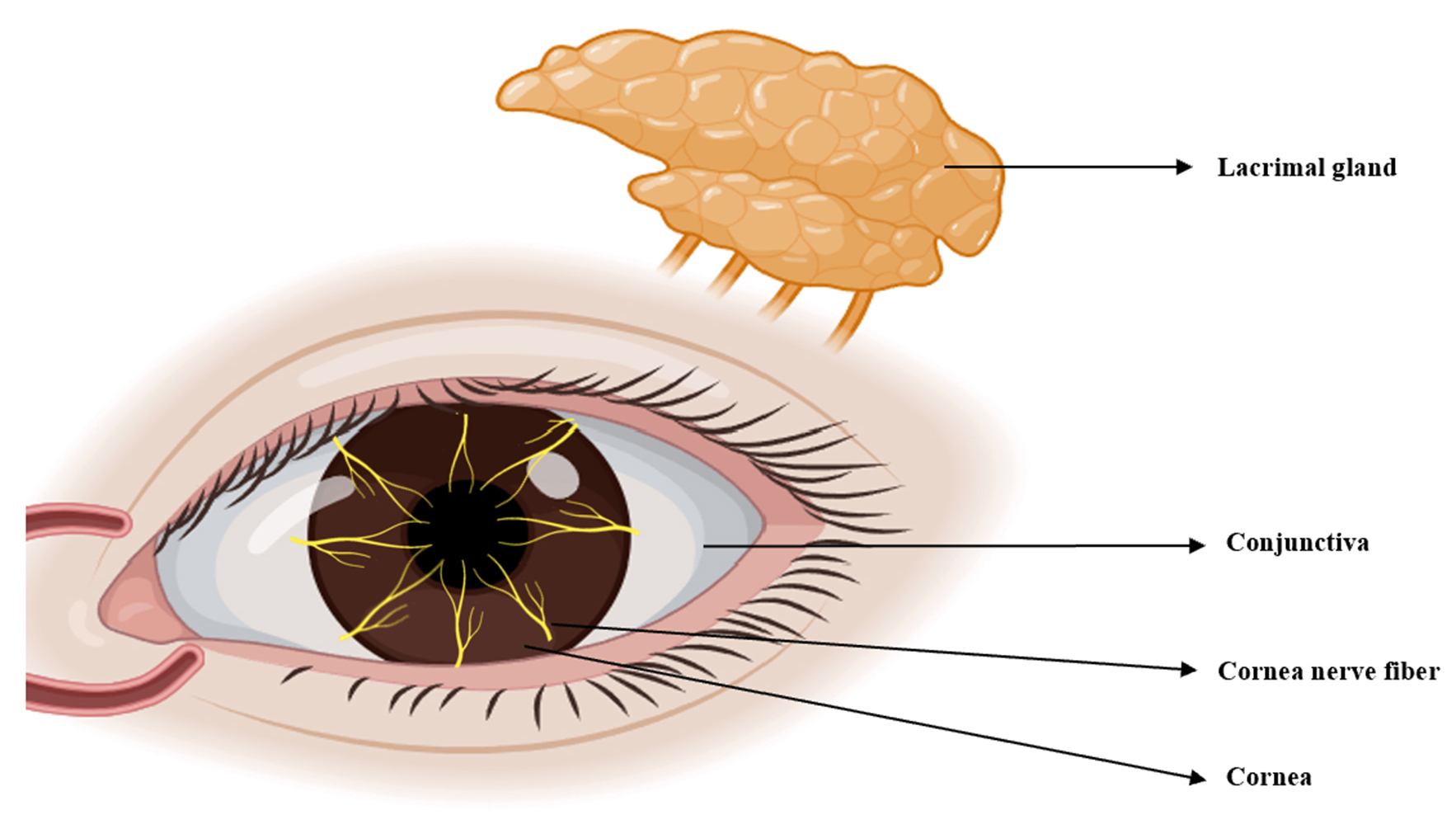

TRPV1 is widely expressed in various organs, including the eyes. Tissues and cells throughout the body utilize TRPV1 for diverse physiological and pathological functions, including coughing, pain, inflammation, itching, hearing, taste and apoptosis [33]. Here, we review the expression of TRPV1 in the anterior segment, corneal nerve fibers, TG and lacrimal gland, as well as its association with DED (Fig. 3).

Zhang et al. [12] first reported functional activity of TRPV1 in corneal epithelial cells in 2017. The TRPV1 channel has been identified in human corneal epithelial cells (HCEC), as well as in the corneal epithelial cells of rats and mice [12, 34, 35, 36]. TRPV1 controls the entry of inflammatory mediators in the corneal epithelium, as well as the subsequent development of hyperalgesia in DED patients and in a mouse model of corneal wound healing [37]. Due to its ability to induce the release of inflammatory mediators, TRPV1 may therefore be crucial for maintaining tissue integrity and the function of HCEC [38].

The structure of the corneal stromal layer plays a role in maintaining corneal transparency [12]. Primary cultured human corneal fibroblasts were found to express functional TRPV1 [13, 39, 40, 41]. Recent studies have shown that keratinocytes also express TRPV1 [42, 43].

The corneal endothelium is a single layer of postmitotic cells that maintains

corneal transparency by regulating the flow of fluid from the stroma into the

anterior chamber [44]. Several studies have shown expression of the TRPV1 channel

in human and rabbit corneal endothelial cells [14, 45]. Moreover, endothelial

TRPV1 is thought to be responsive to temperature changes, thereby contributing to

the regulation of Ca

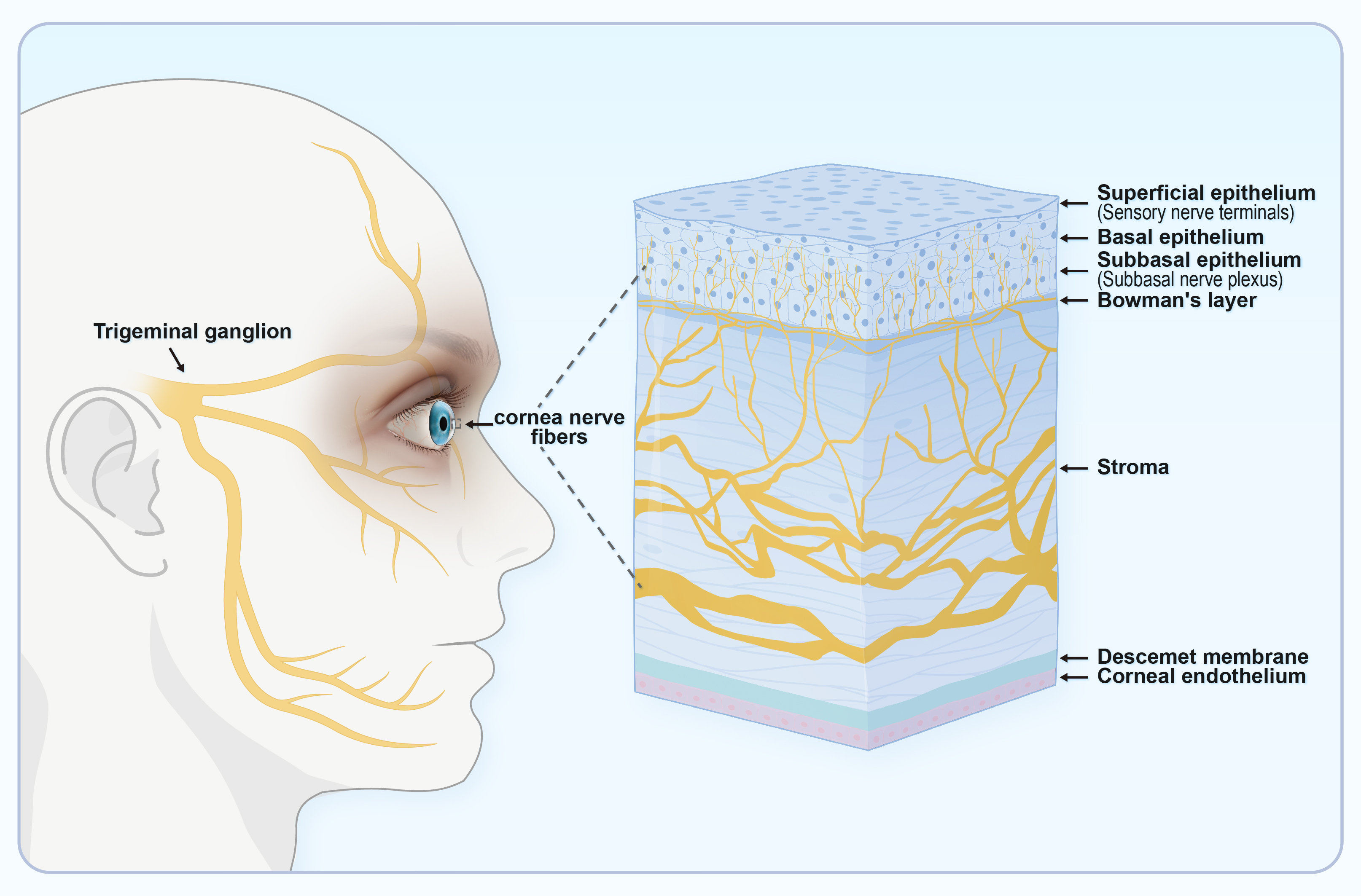

The cornea is innervated by dense nerves that respond to a variety of sensations

[46]. Corneal innervation comprises the sensory axons of trigeminal neurons, as

well as sympathetic autonomic axons from postganglionic neurons in the superior

cervical ganglion [47]. Nerve endings in the corneal epithelium can be divided

into subgroups according to their morphology and to their molecular and

functional phenotypes. Morphologically, the ends of corneal nerve fibers can be

divided into simple, forked, and complex. In terms of their molecular phenotype,

the branched and complex endings express glial cell line-derived neurotrophic

factor family receptor alpha3 (GFR

Due to its role in the structure and physiology of the cornea, the corneal nerve is involved in the pathophysiology of the cornea, including DED. First, the reflex arcs that control tear flow and blinking depend on sensory input from the ocular surface. Hence, the maintenance of adequate tear film depends on corneal nerves. Secondly, corneal nerves contribute to the integrity of the corneal epithelium and to local immune regulation [51, 52, 53], and are thus vital for ocular surface homeostasis. DED usually affects the cornea because of abnormalities in the tear film [54]. The pathophysiology of corneal nerve involvement in DED is manifested mainly through morphological changes, including a reduced density and the presence of deformity [55, 56, 57]. Somatosensory dysfunction of corneal nerves in DED is related to changes in basal tears and blinking, leading to further pathophysiological mechanisms of inflammation and corneal injury [49].

TRPV1 has been extensively described in the corneal nerve fibers of mice, guinea pigs and humans. It was first observed in small primary sensory neurons in the cornea, and later also in non-neuronal cell types. The expression of TRPV1 in the corneal sensory nerve fibers of mice and humans is consistent with the expression observed in non-corneal sensory nerve fibers [11, 15, 58].

TRPV1 is expressed in conjunctival epithelial cells [59]. The conjunctiva accounts for 85% of the total ocular surface area, with the conjunctival epithelium serving as an anatomical mechanical barrier. The integrity of this structure prevents entry by pathogens and contributes to the maintenance of tissue hydration. Disruption of epithelial cells in the conjunctiva of some types of DED is associated with increased osmotic pressure in the tear film, leading to impaired barrier function by the dense conjunctiva and the triggering of inflammatory disorders [60, 61]. Martínez-García et al. [45] confirmed the presence and activity of TRPV1 protein in the human conjunctiva. Subsequent research indicated that TRPV1-mediated calcium influx is inhibited by L-carnitine, leading to osmotic protection against hyperosmolarity. Therefore, the current evidence indicates that TRPV1 is crucial for controlling the osmotic pressure in conjunctival tissue [62].

Corneal sensitivity is innervated by the ocular branch of the TG. This is abundant in the cornea and facilitates the transmission of touch or pain from the outer tissues to the center. Impaired corneal sensitivity can lead to decreased blinking and tear reflexes (Fig. 4) [11]. TRPV1 is abundant in the TG and facilitates sensory transmission. TRPV1 stimulation in peripheral sensory neurons enhances action potential discharge and the release of neuropeptides such as CGRP, neurokinin, and substance P (SP). This results in the production of numerous immune cells and pro-inflammatory agents, thus creating a beneficial signaling feedback cycle that triggers TRPV1 activation and nociceptive signaling to the center [63, 64].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.The ocular sensory pathway. Corneal sensitivity is due to innervation by the ocular branch of the TG, which has abundant nerve endings in the cornea. TG, trigeminal ganglion. (Created using Figdraw).

Immunostaining studies found elevated levels of TRPV1 protein in the TG of rats with DED [65]. However, Yamazaki et al. [66] reported reduced levels of corneal TRPV1 protein in an animal model of DED created by removal of the extra-orbital lacrimal gland. Moreover, Hegarty et al. [16] reported that exposure to capsaicin suppressed natural blinking in rats. Interestingly, the corneal nerve terminal connected to the trigeminal nerve, which is stimulated by capsaicin, did not show TRPV1 expression [16]. These observations suggest possible inconsistencies in the expression of central TRPV1 [67].

Expression of TRPV1 in the epithelial cells of lacrimal glands was first

demonstrated by Martínez-García et al. [45] in 2013. This

observation suggests a potential role for TRPV1 in regulating both lacrimal

secretion and Ca

Research has demonstrated that TRPV1 functions as a hypertonic osmotic sensor.

Therefore, inhibition of TRPV1 could provide osmotic protection and minimize

ocular surface damage caused by hyperosmolality [68].

Osmo-protective agents are one of the conventional treatments

for dry eyes. In conjunction with suitable solutes, they can stop hyperosmosis

from harming the cornea [69]. Khajavi et al. [62] used

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and

immunohistochemistry in a human conjunctiva-derived cell line

(IOBA-NHC) to show that the osmo-protective effect of

L-carnitine in hyperosmosis-induced HCE was due to the prevention of Ca

The cornea has the highest density of nociceptor nerve endings

in the body, and is therefore the organ most able to produce pain [73, 74]. Slow

pain sensation is attributed to sensory nerve fibers called C fibers, which

constitute approximately 80% of the nerve fibers in the cornea. The remaining

corneal nerve fibers, known as A

Following injection into newborn rats, capsaicin binds to the

TRPV1 receptor, resulting in a range of symptoms including neurogenic

inflammation, visceral hyper-reflexia, and pain [79]. When administered

topically, capsaicin produces a strong burning sensation due to it being a TRPV1

agonist. Following this burning sensation, mucous membranes exposed to capsaicin

do not respond negatively to harmful stimuli for a considerable length of time.

Moreover, TRPV1-related ocular pain can be caused by many commonly used

chemicals, including some found in shampoos and soaps [80, 81].

Rats treated with resiniferatoxin (RTX), a strong TRPV1 agonist, used less eye

wipes than rats treated with capsaicin (CAP). This continued for several days without

interfering with the ability of the cornea to blink, or with healing of the

epithelium. Consequently, RTX is regarded as a safe and efficient medication for

managing pain associated with eye disorders and surgery [82].

In cases of allergic conjunctivitis (AC),

Acosta et al. [83] showed that the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine could

reverse the increased blink rate, tear film rupture rate, and multi-mode

nociceptor sensitization to CO

Reduced tear production in dry eye causes inflammation, sensitization of nociceptor nerve endings and thermoreceptors, and long-term alterations in the molecular, structural, and functional pathways of the trigeminal nerve, which in turn causes ocular pain [7]. Research on DED suggests that TRPV1 is likely to underlie the increased corneal cold-sensitive, multimode nociceptor response in chronic tear insufficiency. This is reflected in the enhancement of corneal excitability to cold stimulation [83]. An increased number of corneal neurons expressing TRPV1 and GCRP was observed following lacrimal gland excision (LGE) in a mouse model. The increased expression of TRPV1 in corneal neurons following LGE may activate neuroprotective systems after long-term injury [84]. Amplification of pain and neurogenic inflammation is largely dependent on the sensitization mechanism of GPCRS via the TRPV1 channel [33]. Research using animal models has shown that DED can upregulate genes in the TG that are linked to inflammatory and neuropathic pain. This upregulation can be prevented by repeat treatment with the TRPV1 inhibitor capsazepine, thereby decreasing the sensation of eye pain [38].

Multiple anterior segment tissues and nerve fibers are impacted by

TRPV1-mediated inflammatory damage [33]. TRPV1 perceives a range of environmental

stimuli and is triggered by these to stimulate cellular Ca

Neurogenic inflammation is a particularly important mechanism by which TRPV1

causes inflammation of the ocular surface in DED [87]. Guzmán et al.

[88] found that hyperosmolarity (THO) in conjunctival epithelial cells activates

nuclear factor-

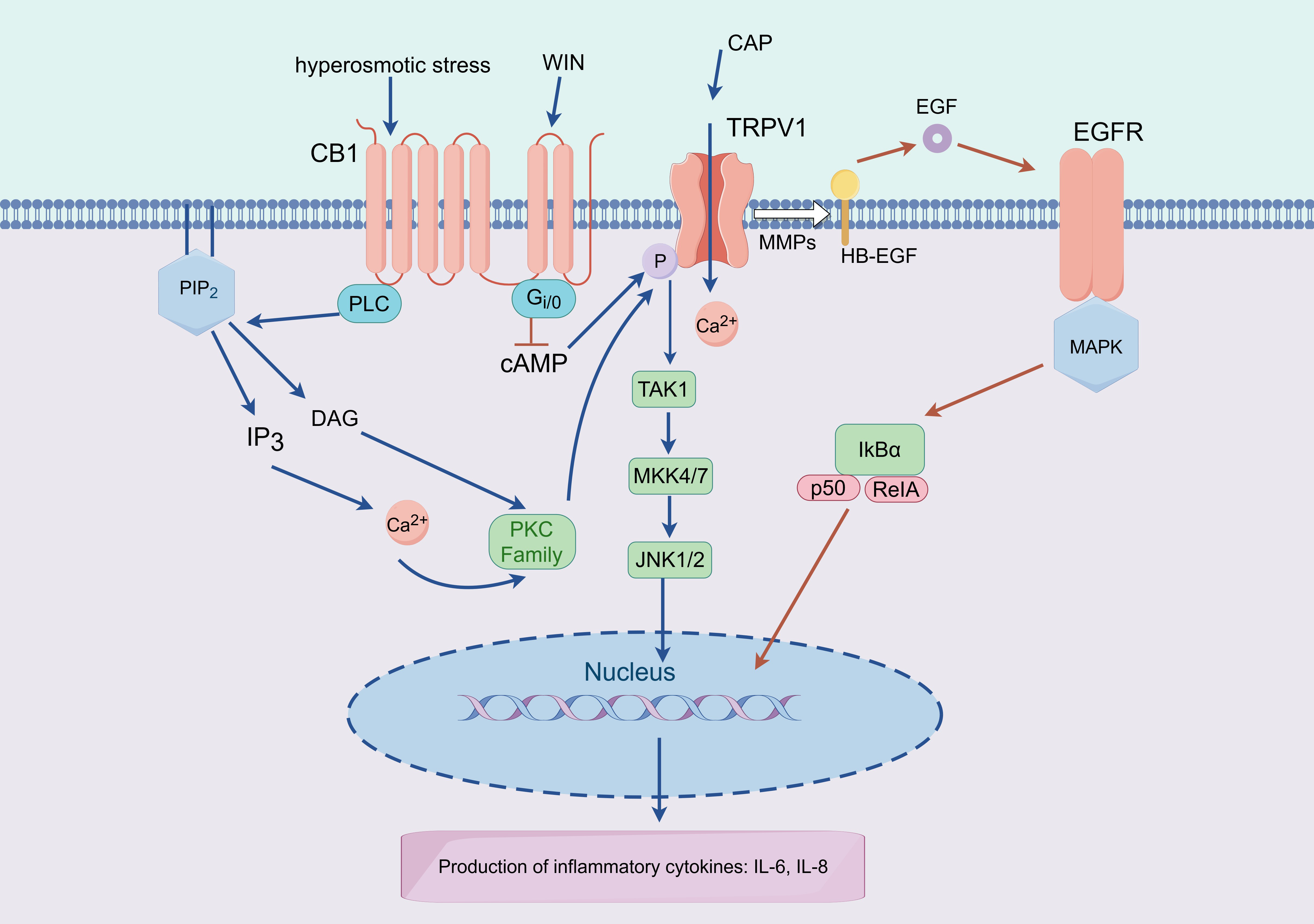

TRPV1 and the GPCR cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) coexist and interact

functionally in HCEC, with TRPV1 mediating Ca

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.Working model of TRPV1-CB1 and TRPV1-EGFR interactions that

mediate expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Lipid precursors (DAG) are

produced by PLC activity and CB1 stimulation, which then stimulate kinases (PKC)

and the release of intracellular Ca

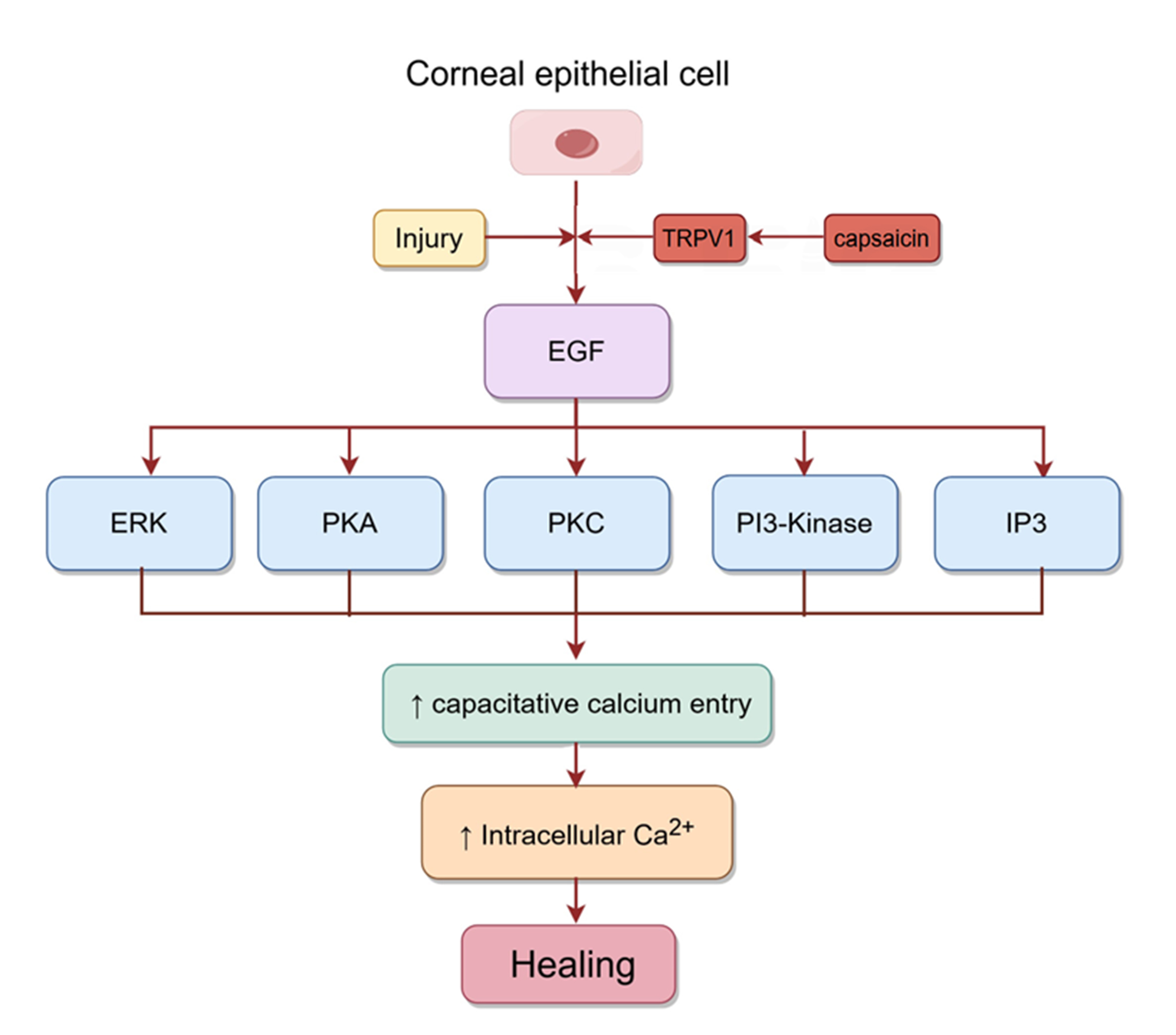

The corneal epithelium is most susceptible to damage during dry eye conditions.

It serves as a protective shield against damaging stimuli, and epithelial cells

are maintained by the migration of basal cells to the upper layers of the tissue

to replace terminally differentiated cells at the surface [36]. Corneal

epithelial injury can promote wound healing by inducing the release of several

growth factors, including EGF. Capsaicin activates TRPV1 in

corneal epithelial cells, which then further activates EGFR by increasing the

release of EGF. The PLC-IP3 cascade subsequently reduces intracellular Ca

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.Signaling pathways involved in corneal epithelial healing.

Injury to corneal epithelial cells activates TRPV1, which then activates EGFR by

mediating the release of EGF. Subsequently, the rise in intracellular Ca

The loss or blocking of TRPV1 expression in mice with alkali burns inhibits the production of TGF1 and other proinflammatory factors, resulting in severe and long-lasting corneal inflammation and scarring [39]. Inactivation of TRPV1 may therefore be a potential therapeutic target to improve inflammatory/fibrous wound healing [41].

The sensation of cold pain in the cornea requires TRPV1 activity and SP release.

The ion channels TRPV1 and TRPM8 are essential for detecting pain and

temperature. Indeed, the sensation of cold pain depends on the co-localization of

these factors [94, 95]. The sensation of cold pain in the eye is typically

indicated by feelings of intense irritation and burning, leading to speculation

the burning feeling may be due to thermal channels like TRPV1. Li et al.

[96] reported that nearly half of all neurons that stained positively for TRPM8

(TRPM8

Previous research indicated that

VEGF-induced Ca

The presence of TRPV1 in tears collected from dry eye patients after exposure to

hypertonic conditions suggests that it may be a potential drug target for

reducing osmotic pressure at the ocular surface [100]. Osmo-protectants maintain

cell volume and stabilize cell structure when cells are exposed to high osmotic

pressure. These small organic molecules play a crucial role in restoring cellular

balance under osmotic stress [70]. Their osmo-protective function is thought to

be associated with the uptake of Na

Activation of TRPV1 could potentially accelerate the healing of corneal epithelium, whereas its inhibition could help to reduce stromal opacity and hyperosmolar inflammation. These properties make TRPV1 a potential target for drug development [34, 35, 93]. The contrasting wound healing effects indicate that TRPV1 antagonists should be restricted to cases of deep interstitial injuries, whereas TRPV1 agonists may be effective for superficial epithelial damage.

Many patients with moderate to severe dry eye syndrome experience symptoms such

as redness, burning, itching, and pain. TRPV1 inhibitors are therefore often

designed to relieve neuropathic and inflammatory pain caused by DED. Tivanisiran

is a synthetic, RNA-interfering, oligonucleotide intraocular infusion designed to

silence human TRPV1 (proto-SYL1001, Sylentis). It has been shown to improve

ocular congestion and tear quality in humans, reduce eye discomfort, and avoid

ocular surface damage (congestion and corneal staining). In a Phase II trial,

Tivanisiran (11.25 mg/mL) significantly reduced eye pain scores, improved

conjunctival congestion from abnormal to normal in 50% of patients, and extended

the tear film rupture time by two seconds [9]. Most current research is focused

on the development of TRPV1 antagonists to relieve neuropathic and inflammatory

pain. Paradoxically, TRPV1 agonists also have analgesic properties. For example,

a concentrated (8%) version of capsaicin called Qutenza is approved in the

United States for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Results from a Phase

2B clinical trial suggest that topical application or injection of capsaicin may

lead to long-term dysfunction of TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons due to

excessive activation of the TRPV1 channel. TRPV1 can cause desensitization when

exposed to capsaicin over a long time period, although the mechanism behind this

de-functionalization is unclear [92, 101]. Bates et al. [82] proposed

that TRPV1 agonists could be used to treat post-operative or post-injury ocular

pain. Their reasoning was based on the observation that direct application of

capsaicin to the cornea in cats reduced pain sensitivity. However, administration

of the powerful TRPV1 agonist RTX eliminated the eye rubbing reaction caused by

capsaicin without affecting the mechanical sensitivity of the cornea [82]. Fakih

et al. [38] also found that topical infusion of an isolated ocular

formulation of capsaicin (10

Based on studies of gabapentin (GBT) use for neuropathic pain, experiments in rabbits showed that GBT eye drops not only have analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, but also stimulate the secretion of tears [102, 103]. Systemic administration of GBT has been used to relieve neuropathic pain in glaucoma patients caused by high intraocular pressure [104]. Biggs et al. [105] found that GBT could enter cells more quickly (500 times faster than via the transporter) through the activated TRPV1 channel to exert an analgesic effect [105]. TRPV1 expression is upregulated at the ocular surface and TG of patients with dry eye [65, 84]. If used for local treatment of DED, it is therefore worth exploring whether GBT has a stronger effect on relieving neuropathic pain via up-regulated TRPV1.

The cornea is comprised of the corneal

epithelium, stroma, endothelium, and nerve fibers. It is currently the subject of

extensive studies into the distribution of TRPV1 in eye tissues and cells

associated with dry eye. The distribution of TRPV1 in the conjunctiva has mainly

been studied in the context of allergic conjunctivitis (AC). Children with AC and

dry eye share characteristics such as unstable tear films. The strong

similarities between DED and AC, and the significant overlap in their symptoms

likely reflects common mechanistic aspects of the two disorders [106, 107].

However, more experimental studies are needed to ascertain TRPV1 expression,

distribution, and function in patients with DED. For example, it has yet to be

confirmed whether TRPV1 is expressed in the meibomian gland. Although some

studies have confirmed the involvement of other TRP channels in tear secretion,

little research has been done on the expression of TRPV1 in the lacrimal gland.

There are two main reasons for the lack of studies on TRPV1 in lacrimal glands.

TRPV1 is a multimode nociceptor that was first observed in neurons. Most research

on DED has therefore focused on the role of TRPV1 in neuro-regulation. Moreover,

most studies have used lacrimal gland resection to create animal models of DED,

and hence the expression of TRPV1 in this tissue could not be evaluated. In

addition, TRPV4 has the same role in the lacrimal gland as it does in the

salivary gland, which is to regulate the ANO1 transporter through Ca

The distribution and expression of TRPV1 channels are clearly different between animal and human tissues. This may underlie functional differences, thereby limiting the use of animal models in TRPV1 research. Whether functional differences exist between different physiological and pathological states also requires further study [67].

Immune dysregulation is involved in the development of dry eye, and hence the

immune function of TRPV1 in allergic diseases has been extensively studied.

During AC, activated TRPV1 can induce inflammatory cells to infiltrate into

tissues and increase Th2 cytokine levels [108]. In the absence of other

pathogenic factors, corneal nerves may be sensitive to immune-driven damage

mediated by Th1 CD4

TRPV1 and TRPM8 are the most commonly studied TRP channels in dry eye, with co-expression of TRPV1 and other TRP subchannels. TRPV1 appears to respond to thermal stimulation and hyper-osmosis, whereas TRPM8 responds to cold stimulation. However, the two channels are co-expressed and interact with each other. Hence, the expression and characteristics of both TRPV1 and TRPM8 should be assessed when studying dry eye, and other TRP channels such as TRPA1 should also be considered.

Under environmental stimuli, the activation of TRPV1 triggers a basic response

that has adaptive functions in preventing or reducing functional damage to

tissue. The ocular surface expresses TRPV1 in order to adapt to different

conditions. This is evident when capsaicin is applied to the eyes, resulting in

intense pain. Due to the growing reliance on video display terminals and the

ongoing process of urbanization, various daily life stressors can activate

corneal TRPV1 channels, thereby contributing to the increasing worldwide

prevalence of dry eye syndrome [112]. DED can be characterized

as abnormal sensations in response to minor stimuli. Corneal paraesthesia is one

of the main symptoms of DED and has become a considerable social burden due to

its increasing prevalence. Based on current research with TRPV1-related targeted

therapy, both TRPV1 agonists and antagonists have potential value not only for

inhibiting corneal sensitivity, but also for inhibiting eye pain. The improvement

of symptoms after using TRPV1 antagonists can be explained by the decreased

response of the ocular surface to stimulation. This further reduces the release

of inflammatory mediators such as SP, thereby relieving pain. With regard to the

efficacy of agonists, there could be additional explanations based on the

principle of desensitization therapy, although further research is needed to

identify the specific reasons. Agonist-mediated inhibition of TRPV1 activity via

down-regulation initially aggravates pain due to the activation of TRPV1, but

this diminishes over time. New and more selective TRPV1 antagonists are being

developed to block nociception. This requires the screening of many candidates,

as it must be shown that any reduction in the functional expression of TRPV1

results in localized and targeted effects, with no systemic response. Moreover,

it is now clear that the use of TRPV1 antagonists to restore corneal function

should be limited to patients with severe injury, and not those with epithelial

injury. This distinction must be made because it is only after damage to the

basement membrane that TGF-

YG and JWL designed the study. YG and JWL provided help and advice on grammar. QQG wrote the manuscript and ZS provided help to the revision. ZS performed the acquisition and interpretation of data. QQG and YG designed the figures. All authors contributed to the editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

We acknowledge Figdraw (www.figdraw.com) for design support of the figures.

This study was financially supported by Natural Science Foundation Project of Chongqing, Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (Grant No. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX0065 and No. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0194), the Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine, Chongqing Medical University (Grant No. W0158), and the Research Start-up Fund of “High-level Talent Introduction Program” of University-Town Hospital of Chongqing.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.