1 Department of Gynecology, Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University, 200011 Shanghai, China

2 Shanghai Key Laboratory of Female Reproductive Endocrine Related Diseases, 200011 Shanghai, China

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, 200032 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Most cervical cancers are related to the persistent infections of high-risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infections. Increasing evidence has witnessed the immunosuppressive effectiveness of HPV in the oncogenesis steps and progression steps. Here we review the immune response in HPV-related cervical malignancies and discuss the crosstalk between HPVs and the host immune response. Furthermore, we describe the identification and development of current immunotherapies in cervical cancer. Above all, we hope to provide a novel insight of the display between HPV infections and the host immune system.

Keywords

- Human Papillomavirus (HPVs)

- cervical cancer

- landscape

- immune response

- immunotherapies

Cervical cancer is one of the malignancies in reproductive system, which disturbs a large amount of women worldwide [1]. At the same time, cervical cancer is widely acknowledged as the first cancer which could be eliminated through prevention strategies [2, 3]. It is widely accepted that Human Papillomavirus (HPVs) could result in benign lesions, precancer lesions and malignant cancers by infections [4, 5, 6]. However, the persistence of “high-risk” HPVs (including HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) infectious contribute to the most cases of cervical cancers [7]. Although increasing screening strategies (HPV genotyping [8, 9], liquid-based cytology [10] and methylation screening [11, 12]) and HPV vaccines [13, 14] are regarded as effective methods to prevent cervical cancer. It is still in a low level of the coverage rates of HPV vaccines and routine HPV screening in developing countries. Thus, it is vital to understand the display of HPV virus and the host immune system which could perform the immune surveillance and immune elimination [15]. Emerging studies reported the roles of the host immune system during the HPV infections [16, 17, 18], however, the detailed crosstalk between the host immune system and the HPV virus (including HPV-infected cells) in diverse stages and lesions is still unclear. Thus, in the present review, we conclude the landscape of host immune system (including local immune system and the systematic immune system in peripheral circulation) after the HPV infections as well as the potential immune therapeutics in cervical cancer.

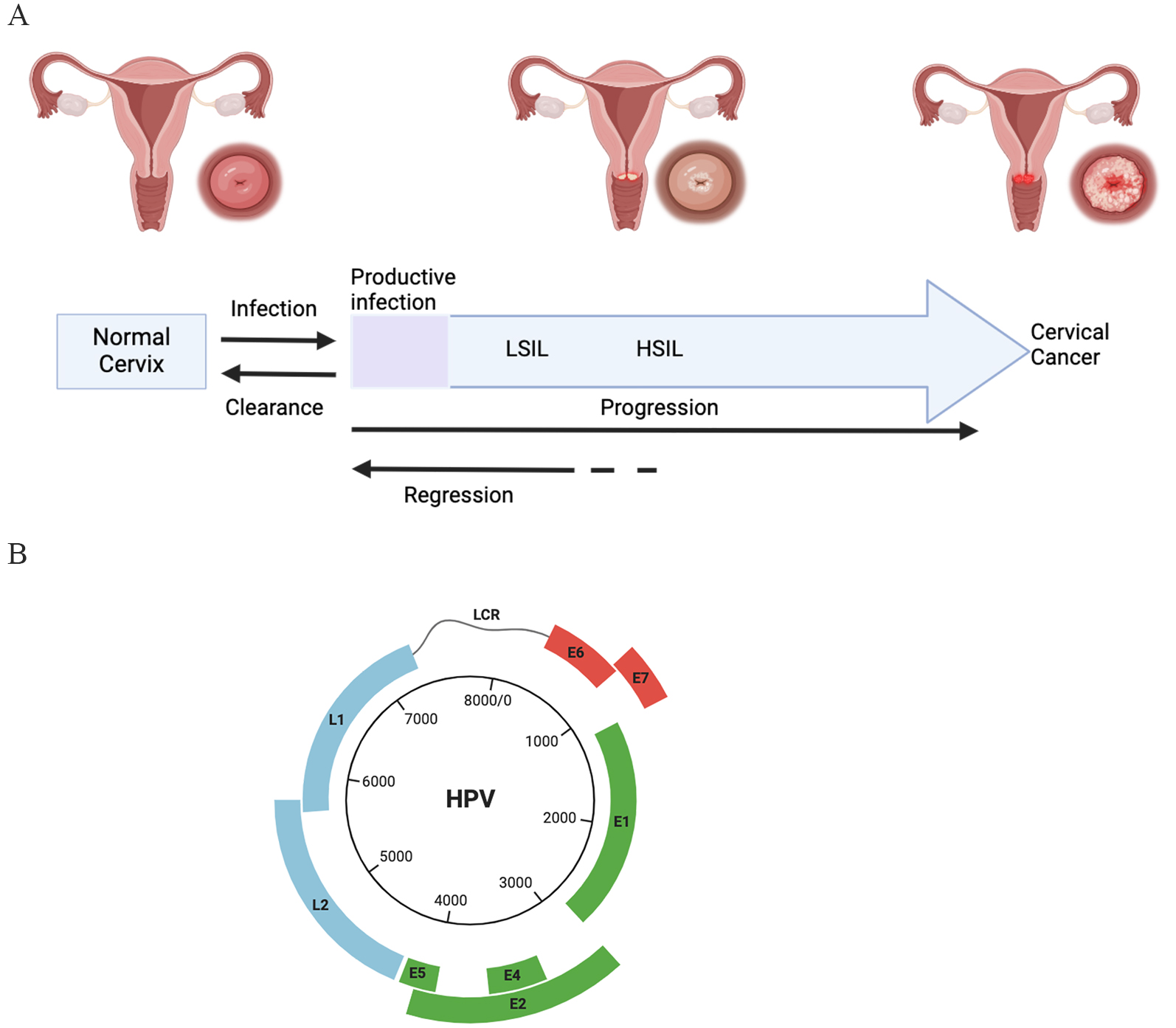

Cervical cancer is one of the most female malignancies in reproductive system. Among all the cervical cancer cases, over 95% of them are attributed to the infections of “high-risk” HPV virus. Women in their early stage of cervical cancer usually have no symptoms whereas irregular bleeding, abnormal discharge from the vagina and pain during sex is indications of severe illness. To diagnose cervical cancer, doctors recommend pap smear test, colposcopy and biopsy of potentially affected tissues [19]. Although the radiotherapy [20] and surgery [21] have saved many lives from cervical cancer, it is widely acknowledged that current HPV vaccinations could remarkably prevent diverse HPV-associated malignancies including cervical cancer and decrease the related economic burden worldwide [22, 23]. Normally, three types of HPV vaccines are widely applied in clinical practices, which are bivalent (2vHPV) vaccine, quadrivalent (4vHPV) vaccine and nonavalent (9vHPV) vaccine. The 2vHPV vaccine could protect people against HPV16 and HPV18, which are two most dangerous HPV types and contribute to most cervical cancers (approximately 70% to 75%). The 4vHPV vaccine could protect people against HPV16, HPV18 plus HPV6 and HPV11 (HPV6 and HPV11 are two HPV types which contribute to most genital warts cases worldwide). In addition, the 9vHPV vaccine could protect people against HPV16, HPV18, HPV6, HPV11 and plus HPV31, HPV33, HPV45, HPV52 and HPV58. When compared to the other 2 kinds of HPV vaccines, the 9vHPV vaccine could draw protection against 90% of genital warts and an additional approximately 20% of HPV-related cervical cancers [24, 25]. Better understanding of the display between HPV and host immune response would promote the development of the future HPV vaccine. As depicted in Fig. 1A, the natural history of HPV infection in cervix includes (1) initial acquisition, (2) persistence of HPV infections, (3) cervical lesions progression. Normally, the host immune system guards the safety and maintains the homeostasis of the human body [1], including to recognize the virus and to eliminate the foreign infections. In most cases, the surveillance of host immune system and subsequent elimination could keep healthy of the body without symptoms. It is widely acknowledged that the host immune (innate as well as adaptive) system could eliminate the infections as soon as the HPV virus infections occur. These processes include the elimination of the virus and destroying the infected cells. However, approximately 10% of these infections led to the precancer lesions, subsequently the malignant transformation with the ineffective immune response or immune exhaustion. Therefore, numerous immunotherapies are explored as a kind of promising approaches to against HPV-related cervical cancers and pre-lesions.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Natural history of Human Papillomaviru (HPV) infection in cervical cancer and HPV genome. (A) Infection with HPV could be cleared by the immune system. Persistent high risk HPV infection could regress but could also progress to pre-cervical lesion and invasive cancer. HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial Lesion; LSIL: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. (B) The HPV genome contains the long control region (LCR), the early region and the late region. E1 protein and E2 protein are required for the DNA replication. L1 and L2 could encode structure proteins for assembly. E4 protein, E5 protein, E6 protein and E7 protein are involved in the viral DNA replication in host cells and achieve immune evasion. Created by BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/).

It is widely acknowledged that HPV-associated infections lead to a significant global health burden world widely. Generally, HPV infections are associated with non-tumor diseases [26] as well as diverse malignancies including cervical pre-cancers, cervical cancers [2]. Beyond cervical cancer, studies showed that HPVs infections are also responsible to other malignancies including vulvar cancers [27], penile cancers [28, 29] as well as neck cancers [30]. According to the epidemiological data, high-risk HPV virus could lead to the most of cervical cancer cases and a significant proportion of anogenital and oropharyngeal carcinoma cases. It is reported that approximately one third of all the known HPV family could led to the anogenital tract infection. As depicted in Fig. 1B, most of the HPVs contain: (i) small circular double stranded DNA genomes (7000–8000 bp), (ii) conserved core proteins and (iii) structural proteins for assembly. Among these viruses, subtypes named HPV16, HPV18, HPV33, HPV52, HPV56, HPV58, HPV31, HPV35, HPV39, HPV45, HPV51 and HPV-59 were classified as high-risk HPV subtypes. Also, some other subtypes are classified as probably high-risk due to the potential affinity ability and infectious ability in mucosa. According to one of the previous studies, the chances of HPV infection in the first year of sexual intercourse is 20% while the chances of the whole lifetime is 80%, which depending on geographical region, life styles and so on [22].

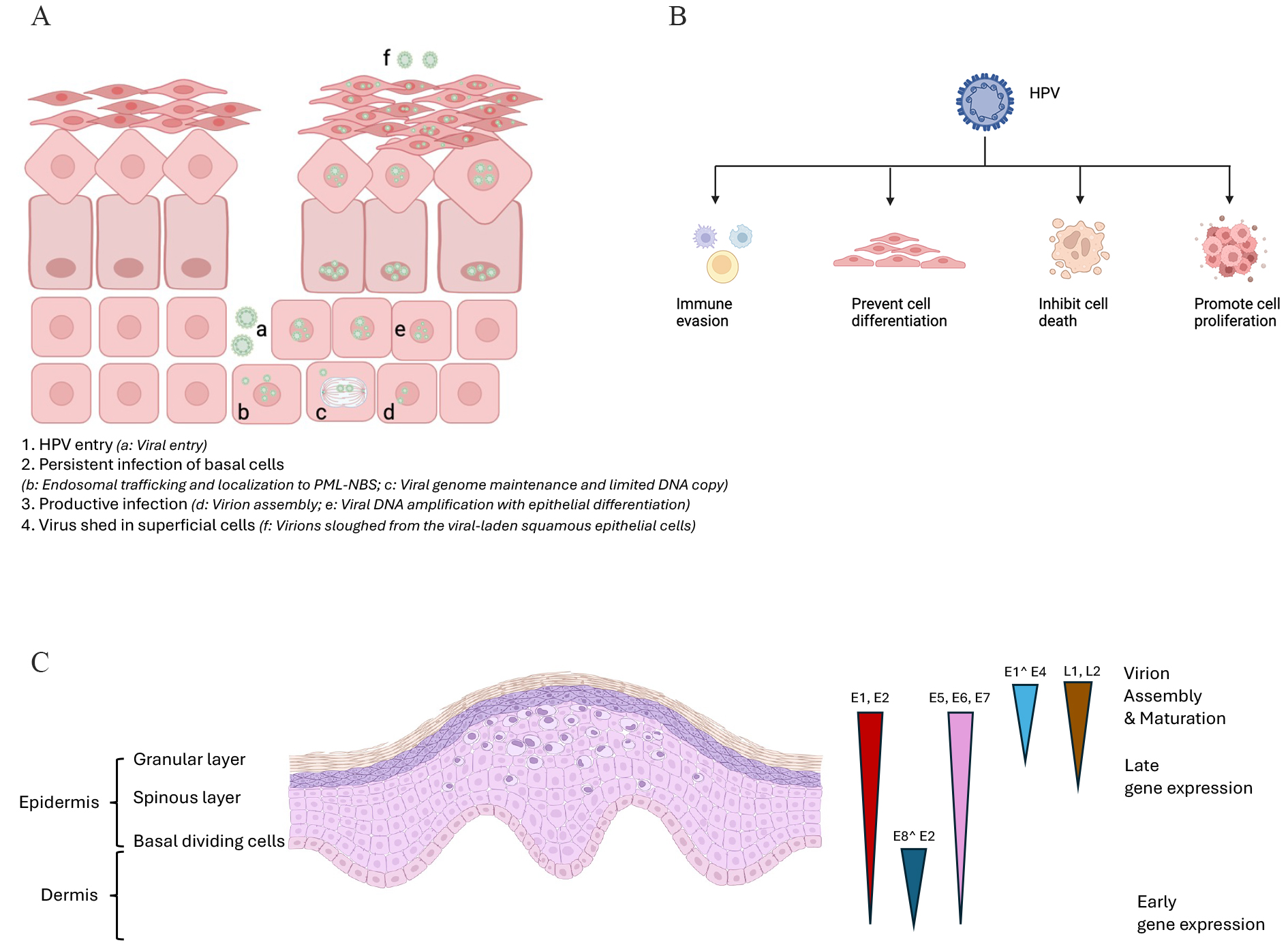

More than 70% of HPV infections are transient in cervical cases, which means that not all the HPV infections lead to the cervical precancer lesion or cervical cancer. When focus on the whole HPV infection life cycle, it is clear that the virus could reach the basal membrane of the epithelium through micro-wounds and infects keratinocytes [6]. As depicted in Fig. 2A, the HPV viral particles reach the dividing basal membrane of the epithelium through micro-wounds at the first step. Then, the HPV particles could enter the basal keratinocytes (KCs) through the endocytosis and bind to the host chromosomes with the help of L2 protein during the mitosis process. The viral DNA achieve the infection with the help of promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML-NBs). The infected basal cells serve as a kind of reservoir for persistent HPV infection. Then, the extrachromosomal viral genomes are tethered to host chromatin, followed by being partitioned into the daughter cells. However, the viral copy number still be kept in a limited level until these cells initiate to move to the epithelium. Finally, the virions were packaged and were shed from the viral-laden squamous epithelial cells. Once HPV viruses entered the body, the HPV will modulate a cellular environment to evade the host immune system and promote the infected cells proliferation, followed by the formation towards cervical lesions and pre-cancer niches, subsequently (Fig. 2B). During these stages, diverse immune responses and crosstalk between virus and host immune system result in elimination or persistent infections.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the infection life cycle of HPV and the cellular processes modulated by HPV. (A) The schematic image of HPV infectious cycle. 1. HPV entry (a: Viral entry); 2. Persistent infection of basal cells (b: Endosomal trafficking and localization to promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML-NBs); c: Viral genome maintenance and limited DNA copy); 3. Productive infection (d: Virion assembly; e: Viral DNA amplification with epithelial differentiation); 4. Virus shed in superficial cells (f: Virions sloughed from the viral-laden squamous epithelial cells). (B) The HPV could support infected cell proliferation and evade immune surveillance. (C) A viral life cycle in HPV-infected mucosal epithelium. The E1, E2, E6, E7, and E8^E2 expressed in basal keratinocytes, while E1^E4, L1, and L2 expressed in the upper epithelial layers. The perinuclear halo in the upper layers and enlarged nucleus could be observed in HPV infected cells. Triangles represent the expression profiles of viral early and late proteins. Created by BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/).

Almost all the HPV genomes (Fig. 1B) mainly are composed of three different regions. The first part is named the “upstream regulatory region (URR)”. It is acknowledged that HPV viruses drive the early transcription from this part. The second part is named “early coding region”. The early transcription ends at polyadenylation sites at the end of this part. Meanwhile, the late transcription starts from here. The third part is named “late coding region”, which is the end part of late transcription. In addition, it is acknowledged that all the HPV viruses encode 4 core proteins of highly conserved. These proteins are listed as below: (1) the E1 replication protein, (2) E2 replication protein, (3) L1 capsid protein and (4) L2 capsid proteins. These above viral proteins could interplay with numerous cellular factors and regulate related processes during the complicated HPV life cycle. Meanwhile, there are some proteins called “less well conserved proteins”, which play role as evolutionary elements during the HPV infections. E1 protein plays role in binding to the replication origin; E2 protein plays roles in binding to the E1 protein for keeping stable. In dividing cells process, E2 proteins could maintain the low viral genome copy number and could involve in the partitioning process. This above sophisticated and tricky strategy could maintain the persistent HPV infection without triggering innate immune responses during the early infection stage (Fig. 2C).

It is clear that the innate immune system and responses play vital roles during the early stage of HPV infections, which including developing a proinflammatory microenvironment, inducing the recruitment of immune cells, elimination of the infected cells. While it is well acknowledged that the high risk-HPV infection for a persistent period contribute most of cervical cancer cases, it is still not fully clear that which immunological mechanisms lead to the persistent infections in patients.

Among the innate immune system, Keratinocytes [31], Langerhans cells (LC) [32],

dendritic cells (DC) [33], and

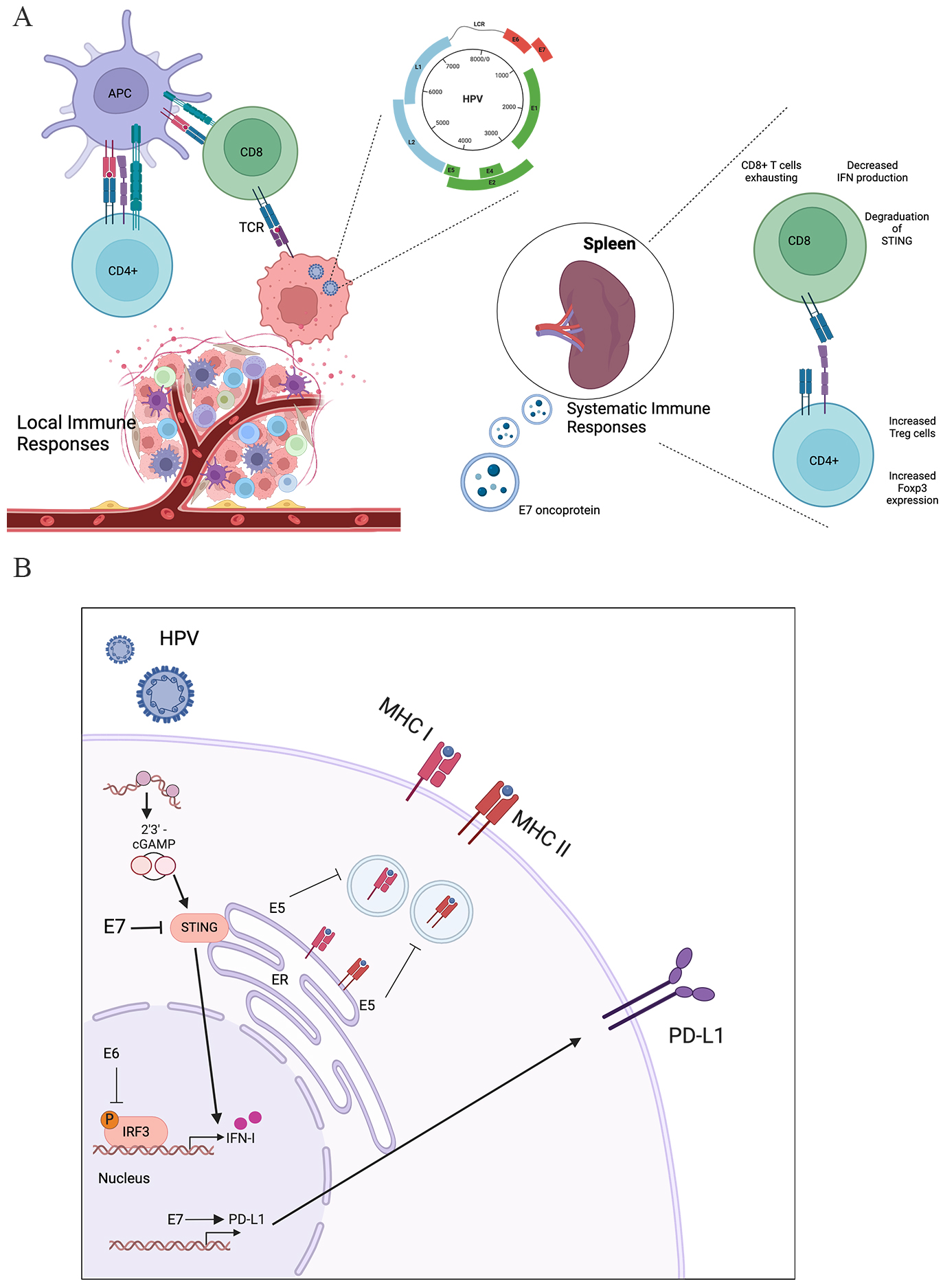

The adaptive immune response plays the leading role in the crosstalk between HPV and host immune system, and HPV virus and immune cells interact in a dynamic equilibrium shaping the progression of the disease. As depicted in Fig. 3A, among these immune cells, T cells is essential to eliminate the infected virus [42]. One of previous studies had showed that T cell mediated-immune responses play a pivotal role in the immune surveillance of cervical cancer and are important effector cells of anti-tumor immunity among the adaptive immune system. Numerous evidence has witnessed the decrease of CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell through the development of HPV-related cervical cancer [43]. One of previous studies had showed that the ratio of CD4+ T cells to CD8+ T cells subtypes in cervical cancer tissue was significantly lower than that in the peripheral blood [44]. Furthermore, the result showed that the alteration of CD4+/CD8+ is related to the prognosis in cervical cancer. Patients with decreased CD4+ Treg level and the increased CD4+/CD8+ ratio obtain better prognosis. What’s more, another study reported that there is a significant inhibition of the level of CD8+ and CD4+ in cervical cancer [45]. In addition, Munk et al. [46] reported that the relationship between cervical intraepithelial neoplasms (CIN) and the infiltration of cervical tissue T cell subsets. CIN patients have higher cervical CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell infiltration than healthy women.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The immuno-microenvironment in local tumor site and systematic immune system modulated by HPV. (A) In the local tumor site, HPV could inhibit the effector T cells and promote the Treg cells. In the systematic immune system, HPV E7 oncoprotein could promote the exhausting of effector T cells and induce the expression of Foxp3 in CD4+ T cells. (B) The cellular mechanism of HPV immune regulation. The HPV virus infects the cell and achieves the immune suppression via the oncoprotein (E5, E6, and E7). HPV E7 protein could inhibit the cGAS-STING pathway and HPV E6 could downregulate the interferon (IFN) production. Meanwhile, HPV E5 cold inhibit the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression and antigen presentation. HPV E7 could upregulate the Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint. APC, antigen-presenting cell; CD, cluster of differentiation; TCR, T cell receptor; LCR, locus control region; cGAS, Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; Foxp3, forkhead box P3; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; cGAMP, cyclic GMP-AMP; IRF3, interferon regulatory factor 3. Created by BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/).

Currently, researchers focuse on lymphocyte infiltration in local cervical tissues cause normally there is little lymphocyte infiltration in normal cervical tissue. Lucena et al. [47] had confirmed that local cell-mediated immune response of cervical lesions is an important mechanism for virus clearance. The activation of CD4+ T cells mediated by cytokines is vital process in the immune response [48, 49]. After HPV infection, the expression of interferon-induced genes is down-regulated through the synthesis of E6 and E7, which prevents mRNA transcription and inhibits the production of interferon by T cells. Up-regulation of Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, binding with PD-1, inhibition of lymphocyte activity, resulting in T lymphocyte failure [50]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of T cells (including CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells) from the cervix is HPV subtype specific. The interferon (IFN)-gamma production level in T cell from cervix is higher than in peripheral blood [51]. What’s more, there is a remarkably higher population of infiltrating lymphocytes as well as forkhead box P3 (FOXP3+) Tregs in HPV-derived lesions, indicating the vital roles of Tregs in the host immune response [52]. What’s more, it was reported that the low infiltration of CD8+ T cells is a potential predictor of lymph node metastasis in cervical cancer [53].

It is widely acknowledged that not only the local immune cells determine the eliminate of HPV virus, the immune cells in peripheral circulation and distance immune organs are also play vital roles in virus elimination [54]. T cells from peripheral blood could provide a large amount of antitumor T cells [55]. However, even though one study reported that T cells can mediate the protection effect against the tumor cells, most of them are exhausted in cervical cancer [56].

As for the effective cytokines, it is reported that patients with high-grade

squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) express reduced IL-2 level, reduced

IFN-

It was widely acknowledged that there are three aspects in the host innate immune responses to against the viral infection: (1) detecting the foreign nucleic acids from viruses, (2) activating related molecular signaling pathways, (3) producing cytokines and developing inflammatory environment. However, “high-risk” HPVs could achieve immune evasion relying on several sophisticated strategies. Firstly, the E6 oncoprotein and E7 oncoprotein could inhibit the DNA sensors as well as disturb the cytokine secretion, which could together suppress the related host inflammatory responses [65]. The E7 oncoprotein could inhibit the expression level of cytosolic DNA sensor stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and subsequently suppress the type I interferons (IFNs) production [17, 66]. Secondly, many viruses could avoid the virus replication inhibition from the host immune responses (APOBEC3, as abbreviation for “apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3” is an example) [67, 68]. Thirdly, E5 protein, E6 protein and E7 proteins could disturb the process of presenting foreign antigens in antigen presenting cells (APCs), which is the first line of defense for activating the subsequent adaptive immune response. HPV viruses could inhibit the recruitment and assemble of epidermal APCs, followed by suppressing the virus-related antigen uptake process [69]. What’s more, HPV viruses could inhibit the expression level of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC I) molecules [70] in virus infected keratinocytes to avoid the antigen presenting process.

Currently, engineered effector T cells therapies have become the more popular and act as a cornerstone of immune-therapeutics against most cancers, and the HPV-related malignancies. Even though immune system (including the innate immune system and adaptive immune system) could build a microenvironment to eliminate the infected virus in human body, HPV viruses also mediate some tricky processes to achieve the evasion from immune surveillance as well as promoting an anti-inflammatory effectiveness [71]. It is reported that the enhanced levels of activated T cells are related to the higher tumor stage, which suggests that the HPV-antigen-primed cytotoxic T cells is tightly associated with the tumor burden [72].

It is reported that the oncogenic viruses with transforming epithelial cells promote the potential immune evasion. As depicted in Fig. 3B, after HPV infection, the expression of interferon-induced genes is down-regulated through the synthesis of E6 and E7, which prevents mRNA transcription and inhibits the production of interferon by T cells [50]. In cervical cancer, HPV16 E7 induced PD‑L1 could result in the lymphocyte dysfunction (Fig. 3B), which could be restored by the soluble PD‑1 by inhibiting the PD‑L1/PD‑1 signaling pathway in tumor‑infiltrating lymphocytes [50]. The HPV infection is also related to the PD-L1 expression in cervical cancer, which suggests HPV oncoproteins might be responsible for the upregulating PD-L1 expression [73]. What’s more, the expression level of HPV E7 oncoprotein was found to be significantly related to the expression level of PD-L1 on the tumoral surface, while E7 oncoprotein induced PD-L1 expression could result in the increased percentage of dysfunctional CD8+ T cells [74].

It is acknowledged that CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg cells) could downregulate effector T cells to inhibit antitumor immunity (Fig. 3A). Several studies showed that the enhanced population of Treg cells in CIN and cervical cancers [75, 76]. Additionally, the proportion of Tregs is related to the severity of lesion. What’s more, the decreased proportion of Treg cells was found in peripheral blood with cervical cancer, which suggests that cervical cancer could promote the systemic immunosuppression [77].

The activation of effector T cells is dependent on the processes of antigen presentation by MHC molecules [78] (Fig. 3). As depicted in Fig. 3B, the HPV virus could regulate the antigen presentation process, and then inhibit the expression of MHC-I molecules and MHC-II molecules [79]. Mechanically, the E5 protein could inhibit the presenting of antigen on MHC molecules, which help the HPV avoid from the effector T cells [80]. As a result, the HPV associated oncoprotein could allow the HPV to achieve the immune evasion through modulate the MHC antigens presentation pathways.

Recently, increasing evidence have witnessed the vital influence of DNA-sensing receptor called “Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS)” [81] and the downstream STING in the complicated tumor immune process (Fig. 3B). It is widely reported that the activation of STING is essential to enhance the anti-tumor immunity [82]. And another study showed that the expression level of STING is associated to the clinical prognosis in cervical cancer [83].

Among these reported mechanisms, viral proteins are reported that might influence the innate immune signaling complexes (including the regulating the stimulator of interferon genes-tANK binding kinase 1 (STING-TBK1) complex [84]) to regulate the downstream pathway. As depicted in Fig. 3B, the HPV E7 oncoprotein could regulate the immune evasion through inhibiting the IFN-I system [85] by STING-TBK1 pathway. One of previous studies showed that HPV16 E7 oncoproteins could drives cancer immune escape by the NLR family member X1 (NLRX1) mediated STING/type I interferon (IFN-I) pathway [86]. Once inhibited the expression of NLRX1, the IFN-I-dependent T cell infiltration was enhanced significantly. Also, other mechanisms are also reported to show how HPV virus achieve the immune evasion from immune system. In addition, HPV16 E5 oncoprotein [87] could also interfere in the immune response. It could help HPV evade from the surveillance of the immune system, and subsequently regulate the cell transformation. In addition, one previous study showed that the vaginal microbial environment also affect the elimination of immune system in cervical cancer [40].

Since the immunotherapies are emphasized by numerous studies in the cancer therapy field. There are multitudinous strategies to activate the immune system to against the HPV infections. Normally there are mainly three parts: (i) immune system activation, including inhibition of immune checkpoints (Immune Checkpoint Blockade, ICB), (ii) therapeutic vaccination, (iii) adoptive cell therapies and (iv) others. As depicted in Table 1 (Ref. [88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109]), there are numerous immunotherapies in the treatment of cervical cancer.

| Type | Subtype | Targeting | Clinical Trails |

| Immune system activation | Immune checkpoint inhibitors | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) | NCT01711515 [88] |

| NCT01693783 [89] | |||

| PD-1/PD-L1 | KEYNOTE-028 [90] | ||

| KEYNOTE-158 [91] | |||

| CHECKMATE-358 [92] | |||

| NCT02635360 [93] | |||

| NRG-GY017 [94] | |||

| cGAS-STING | STING | NCT03937141 [95] | |

| SB11285 [96] | |||

| Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy | Dendritic cell-based therapy (DC-based therapy) | NCT02432846 [97] | |

| prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) | NCT03356795 [98] | ||

| CD22 | NCT04556669 [99] | ||

| Therapeutic vaccination | ADXS11-001 vaccine | HPV16E7 | NCT02853604 [98] |

| Vvax001 | HPV16 | NCT03141463 [100] | |

| TVGV-1 | HPV+ HSIL | NCT02576561 [101] | |

| Intramuscular TA-CIN | priming T cells | NCT02405221 [98] | |

| BNT113 vaccine | HPV16+ | NCT03418480 [102] | |

| Adoptive cell therapies | tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) | T lymphocytes | NCT02360579 [103] |

| CXSL2200061 [104] | |||

| NCT01585428 [105] | |||

| NCT03108495 [106] | |||

| Others | Antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) | Tissue factor (TF) | Innova TV 201 [107] |

| Innova TV 204 [108] | |||

| Innova TV 301 [109] |

Currently, most of the standard-of-care chemotherapies in cervical cancer draw unsatisfactory outcomes [110]. Thus, researchers start to explore the effectiveness of combing chemoradiation (CRT) and PD-1 or PD-L1 blockade in locally advanced cervical cancer. One study showed that CALLA (named “durvalumab”), NCT02635360 (named “pembrolizumab”) and NRG-GY017 (named “atezolizumab”) are ongoing clinical trials. In addition, in other malignancies, there is a phase III trial of CRT versus CRT plus avelumab (anti–PD-L1) stopped early [110].

As for the aspect of vaccines, increasing studies focus on the exploration and application of HPV vaccines. Some studies conduct the study on improving the function and effectiveness of dendritic cells (DCs) and T lymphocytes. One previous study reported that the HPV E6 and E7 tumor antigens are expressed only on cervical cancer cells surface rather than normal tissues [111]. This fact indicates the HPV E6 and E7 tumor antigens might be potential targeting. What’s more, the adoptive cell therapy also exhibits an attractive strategy against HPV-related cancers. The study about the tumor infiltration lymphocytes (TIL) therapy showed attractive outcomes including those durable complete responses (2/9) as well as the partial response (1/9). Furthermore, there is also growing interest in engineering NK cells as a potential immunotherapy method against cervical cancer. Strategies including engineering effective NK cells, enhancing the cytolytic effectiveness of NK cells and optimizing the targeting ability [112].

Immunity system is closely related to the development of cervical precancer lesions and cervical cancer. The crosstalk between host immunity and the HPV infection is of significance during the progression of cervical cancer. HPV could alter the homeostasis of microenvironment and induce the immune suppressive status to achieve the evasion. In the present review, we review the landscape of immune system (innate immune system and adaptive immune system) in HPV-infected conditions. Not the local T cell immune response but also the peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in patients with cervical HSIL and cervical cancer associated with HPV infection were reviewed. The review of the immune status of the patients after HPV infection, which would provide theoretical basis for the early prevention of cervical lesions, disease monitoring and the improvement of immunotherapy.

APCs, antigen presenting cells; APOBEC3, apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3; cGAS, Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasms; DC, dendritic cells; HPV, Human Papillomavirus; ICB, Immune Checkpoint Blockade; IFN-I, type I interferon; KC, keratinocyte; LC, Langerhans cells; LCR, long control region; MHC I, major histocompatibility complex I; PML-NBs, promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies; STING, sensor stimulator of interferon genes; TIL, tumor infiltration lymphocytes; TSCM, stem cell-like memory T cells; URR, upstream regulatory region.

YYG, TTL and MLZ designed the study. FS participated the design and provided help during the revision phase. JHC analyzed the involved references. JXD designed the review study, wrote and reviewed the manuscript. GNZ, modified the conception of the study, finished the figures, and revised the manuscript. KQH, analysed and interpretation of the data, wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.