1 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, The Affiliated Changsha Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, 410008 Changsha, Hunan, China

Abstract

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a serious cardiovascular condition. Vascular peroxidase 1 (VPO1) is associated with various cardiovascular diseases, yet its role in CHF remains unclear. This research aims to explore the involvement of VPO1 in CHF.

CHF was induced in rats using adriamycin, and the expression levels of VPO1 and cylindromatosis (CYLD) were assessed. In parallel, the effects of VPO1 on programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells were evaluated through cell viability assays, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level measurements, and analysis of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1/receptor-interacting protein kinase 3/mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL) pathway-related proteins. The impact of CYLD on RIPK1 protein stability and ubiquitination was also investigated, along with the interaction between VPO1 and CYLD. Additionally, cardiac structure and function were assessed using echocardiography, Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, Masson staining, and measurements of myocardial injury-related factors, including N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), LDH, and creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB).

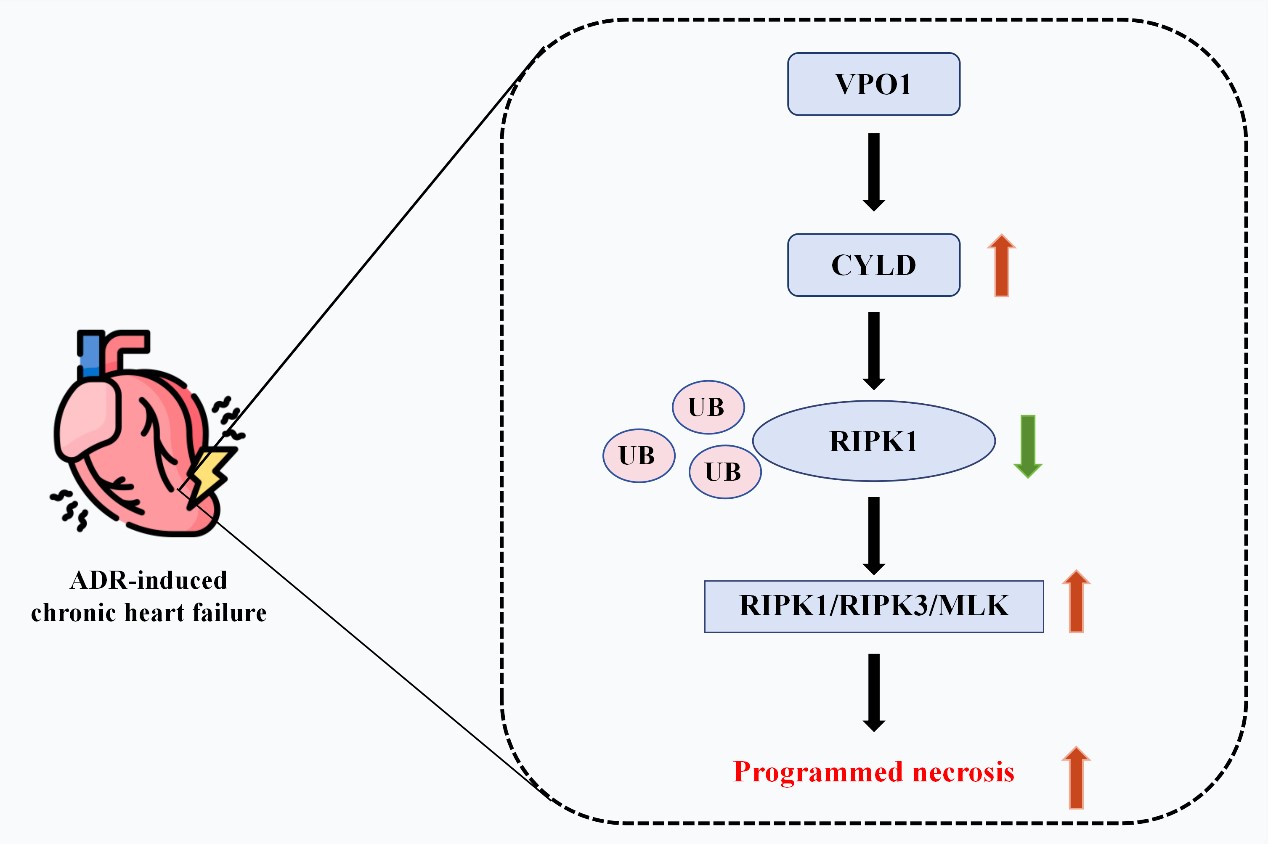

VPO1 expression was upregulated in CHF rats and in H9c2 cells treated with adriamycin. In cellular experiments, VPO1 knockdown improved cell viability, inhibited necrosis and the expression of proteins associated with the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL pathway. Mechanistically, VPO1 promoted cardiomyocyte programmed necrosis by interacting with the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD, which enhanced RIPK1 ubiquitination and degradation, leading to activation of the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway. At animal level, overexpression of CYLD counteracted the cardiac failure, cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial injury, myocardial fibrosis, and tissue necrosis caused by VPO1 knockdown.

VPO1 exacerbates cardiomyocyte programmed necrosis in CHF rats by upregulating CYLD, which activates the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway. Thus, VPO1 may represent a potential therapeutic target for CHF.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- VPO1

- chronic heart failure

- programmed necrosis

- CYLD

- RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL

Chronic heart failure (CHF) represents a significant public health challenge globally, characterized by the heart’s inability to efficiently pump blood to satisfy the body’s needs [1]. Patients with CHF commonly experience symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and reduced physical activity, which can severely impact their quality of life [2]. Additionally, CHF may lead to complications such as lung infections and arrhythmias, and in severe cases, it can be life-threatening [3]. Current treatments for CHF primarily include diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,

A critical pathological feature of CHF is the significant loss of myocardial cells [9], which is closely associated with programmed cell necrosis [10]. The receptor-interacting protein kinase 1/receptor-interacting protein kinase 3/mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL) signaling pathway is essential for regulating programmed cell necrosis [11, 12, 13]. In this pathway, RIPK1 forms a complex with RIPK3, leading to the activation of inflammatory necrosis and endogenous necrosis pathways [11]. MLKL, a substrate of RIPK3, is phosphorylated by RIPK3 [12], causing MLKL to translocate to the cell membrane, where it disrupts membrane integrity and induces cell death [13]. Additionally, the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway interacts with cylindromatosis (CYLD) [14]. CYLD, a deubiquitinating enzyme, plays a crucial role in regulating cell apoptosis and inflammation by removing ubiquitin from RIPK1, thus inhibiting RIPK1-mediated cell death [15, 16]. Furthermore, CYLD can modulate the activation of RIPK3 and MLKL, influencing the necroptosis process [17].

Cell necrosis is often linked to inflammation [18, 19]. During inflammatory responses, Vascular peroxidase 1 (VPO1) regulates oxidative stress [20]. VPO1-mediated reactions facilitate ubiquitination and intracellular signaling processes [21]. VPO1 is implicated in the development of various cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, and hypertension [22, 23]. However, the specific mechanisms and roles of VPO1 in CHF require further investigation.

Therefore, this study aims to elucidate the role of VPO1 in cardiomyocyte programmed necrosis in rats with CHF and to identify key regulatory factors involved in the pathological processes of CHF at the molecular level. Additionally, we investigated the roles of CYLD and the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway in this context to identify new therapeutic targets for the clinical management of CHF.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 8 weeks and weighing 220–250 g, were procured from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). They were acclimated for one week prior to the initiation of experimental procedures. They were randomly assigned to one of 6 groups: Control, Model, Model + small interfering RNA-negative control (Model + si-NC), Model + small interfering RNA for VPO1 (Model + si-VPO1), Model + si-VPO1 + overexpressed negative control (Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC), and Model + si-VPO1 + overexpressed CYLD vector (Model + si-VPO1 + oe-CYLD), with 5 rats per group. The Model group received weekly intraperitoneal injections of 2.0 mg/kg adriamycin (ADR, 25316-40-9, Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) for 6 consecutive weeks to construct the CHF rat model [24]. In addition to ADR, rats in the Model + si-NC, Model + si-VPO1, Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC, and Model + si-VPO1 + oe-CYLD groups were also administered 500 µL of 8

Rat myocardial cells, H9c2 (AW-CNR083, Abiowell, Changsha, China), were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, AW-M003, Abiowell) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10099141, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (AWH0529a, Abiowell) and maintained in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All cell lines were validated by STR profiling and tested negative for Mycoplasma sp.

H9c2 cells were categorized into six groups: Control, Model, Model + si-NC, Model + si-VPO1, Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC, and Model + si-VPO1 + oe-CYLD. Cells in the Model group were treated with 0.5 µmol/L ADR for 24 h [26]. Cells in the Model + si-NC group were transfected with si-NC for 20 min following ADR treatment. For the Model + si-VPO1 group, H9c2 cells were transfected with si-VPO1 (5′-GGGCAGAGATACAGCACATCA-3′) for 20 min post-ADR treatment. In the Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC and Model + si-VPO1 + oe-CYLD groups, cells were transfected with oe-NC and oe-CYLD, respectively, in addition to the si-VPO1 treatment.

Total RNA was extracted from rat myocardial tissues and H9c2 cells using the Trizol reagent (15596026, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After converting the RNA to cDNA with the effective mRNA reverse transcription kit (CW2569, Beijing CoWin Biotech, Beijing, China), 2 µL of cDNA was used for RT-qPCR analysis on a QuantStudio1 system (ABI, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The reaction conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds. The relative mRNA levels of target genes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Specific primer sequences are detailed in Table 1.

| Gene | Primer sequence | Product length |

| R-VPO1 | F: 5′-TGCCTCTCTAGAGCAACTGT-3′ | 146 bp |

| R: 5′-CCAACTGACTGAACGTCCCA-3′ | ||

| R-RIPK1 | F: 5′-CTTAGACGCGTAGGAGCGG-3′ | 173 bp |

| R: 5′-GACGGAGCTAGGTGCTGAAG-3′ | ||

| R-RIPK3 | F: 5′-GCAAGGAGTCAGGGGAATCA-3′ | 244 bp |

| R: 5′-TGGGTTTGGAAGGATGCTCG-3′ | ||

| R-MLKL | F: 5′-GCGCAGGATAGACCAAGACC-3′ | 140 bp |

| R: 5′-TTATCCATACCCCGAGTTCCAG-3′ | ||

| R-GAPDH | F: 5′-ACAGCAACAGGGTGGTGGAC-3′ | 252 bp |

| R: 5′-TTTGAGGGTGCAGCGAACTT-3′ |

VPO1, Vascular peroxidase 1; RIPK1, receptor-interacting protein kinase 1; RIPK3, receptor-interacting protein kinase 3; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein.

Total protein was extracted from rat myocardial tissues and H9c2 cells. The BCA protein quantification kit (AWB0156, Abiowell) was used to determine the protein concentration. Proteins were mixed with 5

| Name | Catalog | Dilution ratio | Company |

| VPO1 | ABS1675 | 1:1000 | Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany |

| p-RIPK1 | AWA48187 | 1:1000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| RIPK1 | AWA48186 | 1:2000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| p-RIPK3 | AWA57678 | 1:2000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| RIPK3 | AWA57677 | 1:1000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| p-MLKL | AWA10442 | 1:5000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| MLKL | AWA51934 | 1:2000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| CYLD | AWA55911 | 1:2000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| A20 | AWA44305 | 1:1000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| Ovarian tumor deubiquitinase 1 (OTUD1) | 29921-1-AP | 1:2000 | Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA |

| Ovarian tumor deubiquitinase 7B (OTUD7B) | AWA50003 | 1:2000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| Ovarian tumor deubiquitinase with linear linkage specificity (OTULIN) | AWA53412 | 1:1000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | AWA80009 | 1:5000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

| HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | AWS0002 | 1:5000 | Abiowell, Changsha, China |

CYLD, cylindromatosis; A20, tumor necrosis factor

To assess protein stability, proteins were treated with 50 µg/mL cycloheximide (CHX, 583794, Gentihold, Beijing, China) for 0, 1, 2, and 3 h. The treated proteins were then analyzed according to the WB procedure described above [27].

The myocardial tissue sections were first baked, placed in xylene and subjected to ethanol at concentrations of 100%, 95%, 85%, and 75%. For antigen retrieval, the sections were immersed in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer (AWT0732a, Abiowell), microwaved to boiling, and allowed to cool for 20 min. After rinsing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, AWR0213a, Abiowell), the antigen retrieval process was completed. Sections were treated with 1% periodate (AWI0186a, Abiowell) at room temperature for 10 min to block endogenous enzyme activity, followed by three rinses with PBS. Primary antibody VPO1 (PA5-144080, 1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was incubated with the sections overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-rabbit IgG (SA00001-2, 1:1000, Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA) was applied to the sections for 30 min at 37 °C. The sections were then treated with the diaminobenzidine (DAB) working solution (ZLI9017, Zsbio, Beijing, China) for color development. Following re-staining with hematoxylin (AWI0009a, Abiowell) and dehydration through graded alcohol (60–100%) for 5 min each, the sections were cleared in xylene. Finally, the sections were mounted and examined under a microscope (DSZ2000X, Cnmicro, Beijing, China).

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were harvested, counted, and seeded at a density of 5

The cellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was measured using the LDH assay kit (A020-2, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level was assessed with the NT-proBNP kit (CSB-E08752r, Cusabio, Wuhan, China). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were determined using the AST assay kit (C010-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). The creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB) level in myocardial tissues was evaluated with the CK-MB kit (CSB-E14403r, Cusabio).

The cells were stained with 30.0 µL of fluorochrome-labeled inhibitor of pan-caspase (FLICA) staining solution (ab219935, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 h in the dark. Following staining, cells were rinsed with washing buffer (ab219935, Abcam). The cells were then mixed with propidium iodide (PI, ab219935, Abcam) and washed with PBS. Flow cytometry was performed using a flow cytometer (A00-1-1102, Beckman, Pasadena, CA, USA) to analyze the results.

Detection of protein levels: H9c2 cell sections were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (AWI0056a, Abiowell). Cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 (AWT0107a, Abiowell) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, AWT0206a, Abiowell) for 60 min at 37 °C. Primary antibody RIPK1 (17519-1-AP, 1:50, Proteintech) was incubated with cells overnight at 4 °C. Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (AWS0005c, 1:200, Abiowell) was applied for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Nuclei were stained with the DAPI working solution (AWC0291a, Abiowell). Sections were mounted with buffered glycerol (AWI0178a, Abiowell) and visualized using a fluorescence microscope (BA410T, Motic, Xiamen, China).

Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) Staining: Rat myocardial tissue sections were treated with sodium borohydride solution (C189300050, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Sections were subsequently blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (80070961, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd) and 5% BSA. Primary antibody Evans blue dye (EBD, bs-1558R, 1:100, Bioss, Beijing, China) was incubated with the sections overnight at 4 °C. Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody was applied for 30 min at 37 °C. Sections were then reacted with TYP-570 (AWI0693a, Abiowell) and stained with WGA staining solution (W21405, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were stained with the DAPI working solution. Tissue sections were cleared with Sudan Black solution and examined under a fluorescence microscope.

Detection of Co-localization: The rats’ heart tissues were embedded and baked at 60 °C for 12 h. Sections were deparaffinized, treated with Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0, AWI0117a, Abiowell), microwaved to boiling, cooled to room temperature, and washed with PBS for 3 min to complete antigen retrieval. Sections were then treated with sodium borohydride solution for 30 min at room temperature, followed by 75% ethanol for 1 min, Sudan Black B (AWI0468a, Abiowell) for 15 min, and 10% normal serum 5% BSA for 60 min. Primary antibody VPO1 (1:200) was incubated with the sections overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000) were applied for 30 min at 37 °C. After rinsing with PBS, sections were incubated with TSA-520 fluorescent dye (AWI0693a, Abiowell) at 37 °C away from light. Moreover, this process was repeated using Troponin T (1:100, ABS1675, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), Vimentin (1:100, 10366-1-AP, Proteintech), or platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31, 1:100, 11265-1-AP, Proteintech) as primary antibodies and TSA-570 (AWI0693a, Abiowell) as the fluorescent dye. Nuclei were stained with DAPI at 37 °C. Sections were mounted with buffered glycerol and observed under a fluorescence microscope for documentation.

The cells were rinsed with PBS and lysed using IP cell lysate (AWB0144, Abiowell). After centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated overnight with VPO1 or RIPK1 antibodies. To capture antigen-antibody complexes, 20 µL of protein A/G agarose was added to the lysate and incubated with the antibodies at 4 °C for 2 h with gentle shaking. Following Co-IP, the levels of VPO1 and CYLD, as well as the expression of RIPK1 and Ubiquitin (#3936, 1:1000, Boston, MA, USA), were assessed by WB.

Cardiac performance indices were calculated using Vevo software (Vevo 1100, VisualSonics, Canada). During surgery, rats were anesthetized with 2.5% isopropyl ether (80111128, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd). Parameters analyzed included left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD).

Rat myocardial tissue sections were baked at 60 °C for 12 h. The sections were then immersed in xylene (10023418, Sinopharm) for 20 min, followed by sequential immersion in ethanol at concentrations of 100%, 100%, 95%, 85%, and 75% for 5 min each. Sections were stained with hematoxylin (AWI0009a, Abiowell) for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water and PBS, and then stained with eosin (AWI0032a, Abiowell) for 3 min. After dehydration with gradient alcohol (95–100%), sections were cleared in xylene for 10 min, mounted with neutral gum (G0503, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA), and observed under a microscope.

Myocardial fibrosis was assessed using a Masson staining kit (AWI0253a, Abiowell). Rat myocardial tissue sections were first baked. A sufficient amount of nuclear staining solution was applied dropwise to cover the entire section, and staining was performed for 1 min. The sections were then immersed in distilled water, followed by soaking in PBS for 5–10 min to restore the blue color of the cell nuclei. Next, the plasma staining solution was applied to the sections. After staining, the solution was discarded, and the sections were treated with a re-staining solution, and then rinsed with anhydrous ethanol. Finally, the tissue sections were dried, cleared with xylene, and sealed.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (8.0.2.263, San Diego, CA, USA). The data are presented as mean

To investigate the role of VPO1 in CHF, we induced CHF in rat models using ADR. Our results demonstrated a significant upregulation of VPO1 expression in these CHF models (Fig. 1A). IHC further confirmed an elevated level of VPO1 in the Model group compared to controls (Fig. 1B). These findings suggested that VPO1 may play a role in CHF-related processes.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Vascular peroxidase 1 (VPO1) was upregulated in rats with adriamycin (ADR)-induced Chronic heart failure (CHF). (A) Expression of VPO1 was assessed by reverse transcription‑quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‑qPCR) and western blot (WB). (B) VPO1 levels confirmed by Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. 400× scale bar = 25 µm, 100× scale bar = 100 µm. *p

We also examined the expression of VPO1 in cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells derived from rat heart tissues. By using markers such as Troponin T for cardiomyocytes, vimentin for fibroblasts, and CD31 for endothelial cells [28], we performed co-localization studies. Our findings indicated that VPO1 co-localized with Troponin T, vimentin, and CD31. Moreover, CHF may affect VPO1 expression in cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells, suggesting that VPO1 may also influence CHF pathology (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C).

To further explore the relationship between VPO1 and programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells, we transfected cells with VPO1-specific siRNA to silence VPO1 expression. Transfection with si-VPO1 markedly reduced VPO1 levels (Fig. 2A). ADR administration upregulated VPO1 expression, whereas si-VPO1 transfection mitigated this increase (Fig. 2B). The level of LDH, a marker of cell necrosis [29], was also measured. Knockdown of VPO1 reversed ADR-induced decreases in H9c2 cell viability and increases in LDH levels and cell necrosis (Fig. 2C–E). RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL are key markers of programmed cell necrosis [13]. Therefore, we assessed their relative expression and protein phosphorylation. At the mRNA level, VPO1 knockdown diminished RIPK3 and MLKL expression but had no effect on RIPK1 mRNA levels (Fig. 2F). At the protein level, VPO1 knockdown lowered the phosphorylation of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL (Fig. 2G). Additionally, immunofluorescence analysis revealed a reduction in RIPK1 levels following VPO1 knockdown (Fig. 2H). These findings suggest that VPO1 downregulation alleviates programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. VPO1 downregulation alleviates programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells. (A) VPO1 mRNA levels were assessed by reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR. (B) VPO1 protein levels were evaluated by WB. (C) Optical density (OD) value. (D) LDH levels were measured with a kit. (E) Necrosis rate was detected by flow cytometry with Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. (F) mRNA levels of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL were examined by RT-qPCR. (G) Phosphorylation of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL was measured by WB. (H) RIPK1 protein levels were assessed by immunofluorescence (IF). Scale bar = 25 µm. *p

To explore the effect of VPO1 on RIPK1 ubiquitination, we employed cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit protein synthesis, thereby promoting the gradual degradation of existing proteins and revealing their stability [27]. As exhibited in Fig. 3A, RIPK1 levels decreased progressively with increasing CHX treatment time. Notably, the knockdown of VPO1 exacerbated the reduction in RIPK1 stability induced by CHX treatment (Fig. 3A). Additionally, VPO1 knockdown led to increased ubiquitination of RIPK1 (Fig. 3B). Ubiquitination of RIPK1 is known to be regulated by deubiquitinases [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. We measured the levels of several deubiquitinases, including CYLD [30], A20 [31], OTUD1 [32], OTUD7b [33], and OTULIN [34], using WB. However, VPO1 knockdown specifically lowered CYLD levels without affecting other deubiquitinases (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we observed that VPO1 interacted with CYLD (Fig. 3D), suggesting that VPO1 may inhibit RIPK1 ubiquitination through CYLD. To further validate this, we overexpressed CYLD. Compared to the Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC group, overexpression of CYLD increased both CYLD and RIPK1 levels while reducing RIPK1 ubiquitination (Fig. 3E,F). These results demonstrated that VPO1 inhibited RIPK1 ubiquitination via CYLD.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. VPO1 inhibits RIPK1 ubiquitination via deubiquitinase CYLD. (A) RIPK1 protein stability was assessed by WB. (B) RIPK1 ubiquitination was examined by Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP). (C) Levels of deubiquitinases CYLD, A20, OTUD1, OTUD7b, and OTULIN were measured by WB. (D) Interaction between VPO1 and CYLD was visualized by Co-IP. (E) Levels of CYLD and RIPK1 were determined by WB. (F) RIPK1 ubiquitination was calculated by Co-IP. *p

Next, we investigated whether the alleviation of programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells by VPO1 downregulation was associated with the CYLD/RIPK1 axis. As depicted in Fig. 4A–C, overexpression of CYLD counteracted the reduction in H9c2 cell viability, lower LDH levels, and decreased cell necrosis observed with VPO1 knockdown. Moreover, in contrast to the Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC group, CYLD overexpression enhanced the phosphorylation of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL (Fig. 4D). These findings suggested that VPO1 downregulation could alleviate programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells through the CYLD/RIPK1 axis.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. VPO1 downregulation alleviates programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells via the CYLD/RIPK1 axis. (A) H9c2 cell viability was measured by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. (B) LDH levels were calculated using a kit. (C) Necrosis rate was detected by flow cytometry with Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate/propidium iodide (Annexin V-FITC/PI) staining. (D) Phosphorylation levels of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL were measured by WB. *p

Cellular programmed necrosis is tightly related to CHF [10]. To explore whether the downregulation of VPO1 could improve ADR-induced CHF in rats through the CYLD/RIPK1 axis, we utilized the CHF rat model for subsequent experiments. LVEF, LVFS, LVESD, and LVEDD are commonly recognized for evaluating cardiac structure and function [35]. As shown in Fig. 5A, rats in the Model group exhibited lowered LVEF and LVFS levels and elevated LVESD and LVEDD levels in contrast to the Control group, suggesting that CHF weakened heart function in rats. However, the knockdown of VPO1 attenuated the decline in cardiac function of CHF mice, and this effect could be reversed by CYLD overexpression (Fig. 5B). Additionally, CHF is often accompanied by cardiac enlargement and thickening [36]. Thus, we determined the ratios of heart weight/body weight (HW/BW) and heart weight/tibia length (HW/TL). Compared to the Control group, the ratios of HW/BW and HW/TL were raised in the Model group, suggesting that the heart was enlarged and thickened under the impact of CHF. Comparatively, the knockdown of VPO1 alleviated this phenomenon, but the role of VPO1 knockdown was inhibited by overexpression of CYLD (Fig. 5B). Next, we observed the levels of myocardial damage and fibrosis in the left ventricle of rats. Rats in the Model group had exacerbated myocardial damage and myocardial fibrosis relative to the Control group. However, VPO1 knockdown alleviated myocardial morphological damage and myocardial fibrosis and CYLD overexpression suppressed this ameliorative effect of VPO1 knockdown on myocardial damage and fibrosis (Fig. 5C,D). Moreover, we hypothesized that the levels of cardiac injury-related factors NT-proBNP, AST, LDH, and CK-MB in serum. CHF raised the levels of NT-proBNP, AST, LDH, and CK-MB, suggesting that cardiac injury was increased, and our results showed that VPO1 downregulation reduced the NT-proBNP, AST, LDH, and CK-MB levels. Overexpression of CYLD reversed the mitigating effects of VPO1 downregulation on cardiac injury (Fig. 5E). The above results postulated that downregulation of VPO1 could improve ADR-induced CHF in rats via the CYLD/RIPK1 axis.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. VPO1 downregulation improves ADR-induced CHF in rats via the CYLD/RIPK1 axis. (A) Cardiac function was assessed by echocardiography measuring LVEF, LVFS, LVESD, and LVEDD. (B) Ratios of HW/BW and HW/TL were calculated. (C) Myocardial damage was evaluated using HE staining. The arrows represent the areas of myocardial injury. 400× scale bar = 25 µm, 100× scale bar = 100 µm. (D) Myocardial fibrosis was assessed by Masson staining. The arrows represent the areas of myocardial fibrosis. 400× scale bar = 25 µm, 100× scale bar = 100 µm. (E) Serum levels of NT-proBNP, AST, LDH, and CK-MB were measured. *p

We further validated whether VPO1 downregulation could improve ADR-induced programmed necrosis of rat myocardial cells through the CYLD/RIPK1 axis. VPO1 knockdown reversed the ADR-induced elevation of both VPO1 and CYLD levels. In contrast to the Model + si-VPO1 + oe-NC group, overexpression of CYLD enhanced CYLD levels without significantly altering VPO1 levels (Fig. 6A), indicating that changes in CYLD expression did not affect VPO1 levels. To assess myocardial cell necrosis, we applied WGA to localize myocardial cells and EBD to label damaged cells [37, 38]. IF analysis implicated that VPO1 downregulation lowered myocardial cell necrosis in rats, whereas CYLD overexpression reversed this effect (Fig. 6B). Additionally, CYLD overexpression negated the reductions in phosphorylation of RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL caused by VPO1 knockdown (Fig. 6C). These findings confirmed that VPO1 downregulation improved ADR-induced programmed necrosis of rat myocardial cells via the CYLD/RIPK1 axis.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. VPO1 downregulation improves ADR-induced programmed necrosis of rat myocardial cells via the CYLD/RIPK1 axis. (A) Levels of VPO1 and CYLD were examined by WB. (B) Myocardial tissue necrosis was evaluated by immunofluorescence (IF). Scale bar = 25 µm. (C) Levels of p-RIPK1/RIPK1, p-RIPK3/RIPK3, and p-MLKL/MLKL were measured by WB. *p

The treatment of CHF remains a prominent area of research [39]. This study highlighted the role of VPO1 in CHF, demonstrating that VPO1 activated the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway by upregulating CYLD, thereby promoting programmed necrosis of cardiomyocytes in rats. Our investigation into VPO1’s role in CHF is a novel contribution to the field.

VPO1 is primarily expressed in endothelial and smooth muscle cells of the cardiovascular system [21]. It plays a critical role in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, endothelial cell apoptosis, and smooth muscle cell proliferation through oxidative stress [40, 41, 42]. Furthermore, VPO1 influences conditions such as atherosclerosis and myocardial fibrosis [23, 43]. In this study, we observed increased VPO1 expression in ADR-induced CHF rats, aligning with its known involvement in cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, VPO1 was found in cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells in the heart, suggesting a potential link between VPO1 expression and cardiac function. The activity and level of LDH are commonly used to evaluate tissue damage or cell lysis [44]. The RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL pathway is a crucial signaling mechanism for programmed cell necrosis [45]. In our cellular experiments, ADR-induced programmed necrosis in H9c2 cells was mitigated by VPO1 knockdown, which improved cell viability, reduced LDH levels, and decreased cell necrosis. Additional experiments suggested that VPO1 promotes CHF progression, possibly through its interaction with the deubiquitinase CYLD. This interaction contributed to the ubiquitination and degradation of RIPK1, thereby modulating cardiomyocyte necrosis via the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway.

The deubiquitinases CYLD, A20, OTUD1, OTUD7b, and OTULIN are known to regulate RIPK1 [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. Our study found that only VPO1 knockdown specifically reduced CYLD levels, with CYLD overexpression not affecting VPO1 levels, suggesting that CYLD functions downstream of VPO1. Previous research indicates that CYLD regulates the nuclear factor-

Our present study further validated the effects of VPO1 knockdown on ADR-induced CHF in rats. Evaluation of cardiac structure and function was performed using LVEF, LVFS, LVESD, and LVEDD [50, 51]. Myocardial fibrosis, which contributes to myocardial stiffness and impairs heart function and contraction, was assessed [52]. Additionally, myocardial injury was estimated through serum levels of NT-proBNP, BNP, AST, and CK-MB [53]. Research has demonstrated that VPO1 mitigates oxidative damage in the heart [41], and VPO1 signaling may also regulate mitochondrial fragmentation and senescence in cardiomyocytes [54]. In our study, CYLD overexpression reversed the benefits of VPO1 knockdown, including the reduction in heart failure, myocardial hypertrophy, myocardial injury, myocardial fibrosis, and myocardial cell necrosis observed in rats. These findings suggested that VPO1 may influence RIPK1 ubiquitination through CYLD, thereby modulating cardiac structure and function via the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL pathway, and playing a protective role in CHF development. Moreover, the interaction between VPO1 and CYLD appeared to have a significant regulatory impact on CHF pathogenesis. Beyond its role in ubiquitination, we hypothesized that this interaction might also influence NF-

Our findings indicated that VPO1 could be an effective target for CHF treatment. By modulating the expression or interaction of VPO1 and CYLD, it may intervene in the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway, thereby reducing programmed necrosis of cardiomyocytes and improving cardiac structure and function. However, several technical challenges remain, such as the time and cost associated with translating these findings into clinical applications, and the need for individualized treatment strategies and interventions targeting VPO1 and CYLD.

Despite these promising results, the study had some limitations. While we confirmed the interaction between VPO1 and CYLD, further research is needed to elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying this interaction and its involvement in additional signaling pathways. Furthermore, as the current study relies on a rat model, clinical research is essential to determine whether drug-mediated inhibition of VPO1 can effectively improve heart failure in human patients.

In summary, this study demonstrated that VPO1 promoted programmed necrosis of cardiomyocytes in rats with CHF by upregulating CYLD and activating the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL signaling pathway. These findings offered new insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CHF and highlight VPO1 as a potential target for future heart failure treatments. Future research will focus on exploring additional molecular signaling pathways involving VPO1 and CYLD and examining the role of VPO1 within the clinical context of CHF.

CHF, Chronic heart failure; VPO1, Vascular peroxidase 1; CYLD, cylindromatosis; LDH; lactate dehydrogenase; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s; si-NC, small interfering RNA-negative control; oe-NC, overexpressed negative control; CHX, cycloheximide; ECL, enhanced chemiluminescence; CCK-8, Cell counting kit-8; IHC, Immunohistochemistry; WB, Western Blot; RT‑qPCR, Reverse transcription‑quantitative polymerase chain reaction; IF, Immunofluorescence; WGA, Wheat Germ Agglutinin; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening; HW/TL, heart weight/tibia length; HW/BW, heart weight/body weight; SD, standard deviation.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YZ and LF designed the experimental framework. LF provided the administrative support. ZS and ZM collected the data. YZ, DH and CL visualized the data. YZ, ZS and LF analyzed the data. YZ, ZS and ZM wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All experimental procedures and animal handling were performed with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Affiliated Changsha Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University (No. 2021-69), in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and studies involving laboratory animals follows the ARRIVE guidelines.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 2022JJ40517, 2022JJ30627), and the Natural Science Foundation of Changsha (Grant No. Kq2202001).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2912425.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.