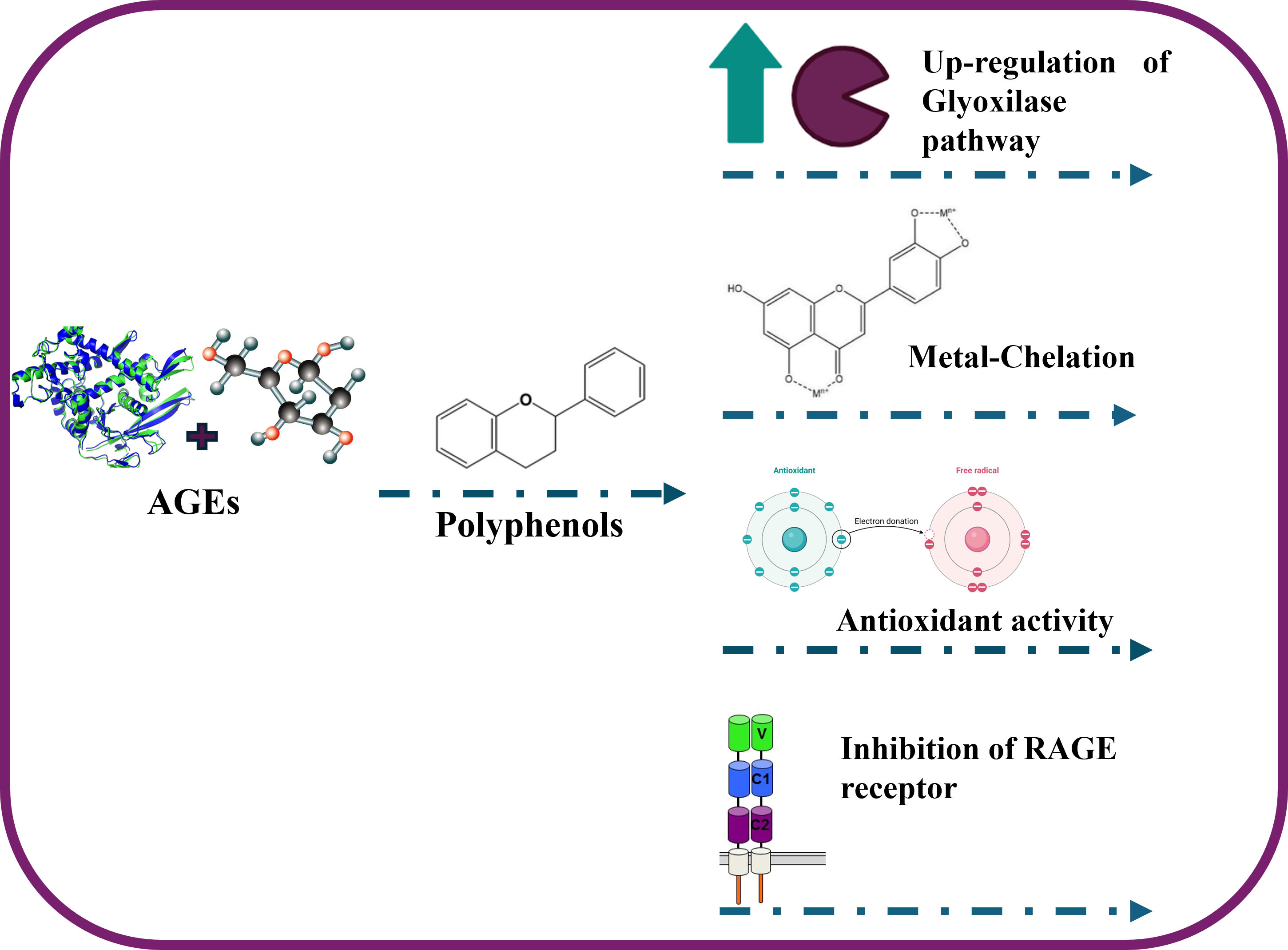

Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) are harmful compounds formed through a non-enzymatic reaction between reducing sugars and proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids. This process, known as glycation, is a complex molecular sequence involving multiple reaction stages. The Maillard reaction is the primary pathway leading to the formation of AGEs [1]. Initially, this reaction involves the interaction between the carbonyl group of reducing sugars and the amino group of amino acids, resulting in the formation of a Schiff base. This intermediate is highly unstable and quickly rearranges into Amadori products by the oxidative cracking process. The Amadori products subsequently undergo further structural changes; it was converted into highly reactive dicarbonyl compounds such as methylglyoxal (MGO), glyoxal (GO), and 3-deoxyglucosone (3-DG), which are generally known as intermediate glycation products. Obviously, the AGEs formation is exacerbated under hyperglycemic conditions [2], making AGEs a significant factor in the pathogenesis and progression of several diabetes-related complications [3] and in other chronic pathological dysfunctions [1]. From the molecular point of view, AGEs exert their action both extracellularly and intracellularly. In particular, at the extracellular level, AGEs could directly form cross-links with extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen and elastin, changing several tissues’ biomechanical and structural properties. Particularly, the AGEs-elastin complex formation plays a pivotal role in reduced elasticity and improved tissue stiffness, both at skin and blood vessel levels [4]. Additionally, AGEs can exert pathological effects also at the intracellular level through interaction with their specific receptors, Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products (RAGE), expressed by several cell types [1]. The binding of AGEs to RAGE activates various intracellular signaling pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-B) pathway, which promotes inflammation and oxidative stress. Polyphenols are naturally occurring secondary metabolites almost found in plants, structurally characterized by multiple phenol units. Recently, these compounds have gained valuable attention for their several studied heathy-promoting effects in humans [5, 6]. Increasing efforts are now focused on identifying natural substances that can inhibit AGEs formation. In this scenario, polyphenols have shown valuable anti-AGE activity in both in vitro and in vivo models [1]. It was well-reported that polyphenols could interfere with their formation at different levels of the AGEs synthesis process. Specifically, one of the primary mechanisms by which polyphenols confer health benefits is through their potent antioxidant activities. These compounds neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and alleviate oxidative stress, a key factor in AGEs formation. During the initial stages of the Maillard reaction, many free radicals are generated. The Schiff bases formed are highly susceptible to oxidation, producing more free radicals and reactive carbonyl compounds. By scavenging these free radicals early, oxidative stress is reduced, and the formation of reactive carbonyl and dicarbonyl compounds is minimized, inhibiting glycation. Several polyphenolic acids and flavonoids, due to their intrinsic antiradical activity, can counteract AGEs formation by alleviating oxidative stress conditions. While phenolic acids such as gallic acid, ferulic acid, and chlorogenic acid, compounds largely diffused in fruit and vegetables, have shown an inhibitory effect on the in vitro AGEs formation, with a calculated IC50 of 0.085 mM, 0.090 mM and 0.150 mM, flavonols such as quercetin and especially rutin, have shown a more relevant inhibition of AGEs with an IC50 of 0.025 mM and 0.020 mM [7]. This variation in terms of anti-AGEs activity was related to the structural difference between these two polyphenolic classes. From the chemical point of view, when the base-phenolic chemical backbone was functionalized with many phenolic groups, it could be able to trap the MGO by the formation of hydrogen bonds between their phenolic functions and the carbonyl groups of MGO, leading to form a stable complex with no attitude to react with proteins [7]. In this regard, quercetin and hesperidin, the main flavonols in citrus species [8], as well as epigallocatechin gallate [9], the major catechin in green tea, and procyanidins, the principal bioactive component in grape seeds have shown valuable MGO-trapping activity [10]. Another polyphenolic mechanism of action proposed to contrast the glycation process is the detoxification of MGO formed [11]. In particular, hesperidin, resveratrol, epigallocatechin gallate, and rutin have been reported to upregulate the glyoxalase system, a specific enzymatic pathway consisting of two main enzymes, Glyoxalase I (GLO I), which catalyzes the conversion of MGO and GSH to S-D-lactoylglutathione, and Glyoxalase II (GLO II), which is able to hydrolyze S-D-lactoylglutathione to D-lactate and regenerate reduced glutathione (GSH) [11]. Specifically, such polyphenols can activate the transcription of the GLO I gene by activating the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway. Specifically, Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates the expression of a wide types of genes involved in antioxidant defence, detoxification, and cellular stress responses. In this context, Nrf2, when activated, binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) in the promoter region of the GLO I gene, enhancing its expression. Another strategy by which polyphenols combat the glycation process is the chelation of several metal ions such as iron (Fe2⁺) and copper (Cu2⁺), which play a catalytic role during the oxidative formation of Schiff bases and Amadori products rearrangement [12]. In this regard, quercetin and rutin can chelate these metals, reducing their availability to participate in oxidative reactions, resulting in a reduction rate of AGEs formation. Finally, the last polyphenols-related anti-AGEs mechanism of action is the inhibition of RAGE receptors. Specifically, it was reported that resveratrol could exert a protective function against MGO-induced injury and can reduce liver injury caused by type 2 Diabetes mellitus by reducing the expression levels of RAGE in the liver [13], while Epigallocatechin-3-gallate was able to directly block the RAGE [14]. In conclusion, polyphenols offer a natural and promising strategy to combat AGEs formation, safeguarding against the harmful effects of glycation in diabetes, chronic diseases, and cosmetic concerns. Their different mechanisms of action, position them as potent inhibitors of AGE formation. Nonetheless, their clinical application faces challenges due to poor bioavailability, limiting their oral efficacy. To overcome this, the development of gastro-resistant formulations and advanced delivery systems is crucial to enhance their absorption and therapeutic potential. Further research is essential to fully understand the benefits of polyphenols in managing AGEs, especially in humans.

Author Contributions

MM: conceptualization, writing, writing and editing; GCT: supervision, writing and editing. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Given his role as the Editorial Board member, Gian Carlo Tenore had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Graham Pawelec.