1 Department of Immunology, Institute of Biomedical Research Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM, 04510 Mexico City, Mexico

2 Research Group Immunophysiology, Division of Neurophysiology, Institute of Physiology and Pathophysiology, Philipps Universität, 35037 Marburg, Germany

3 Research Directorate, National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery Manuel Velasco Suárez, Tlalpan, 14269 Mexico City, Mexico

4 Laboratory 4 Translational Sciences, Center for Research on Aging, CINVESTAV South Headquarters, 14330, Mexico City, Mexico

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating, neuroinflammatory, progressive disease that severely affects human health of young adults. Neuroinflammation (NI) and demyelination, as well as their interactions, are key therapeutic targets to halt or slow disease progression. Potent steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as methylprednisolone (MP) and remyelinating neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone (ALLO) could be co-administered intranasally to enhance their efficacy by providing direct access to the central nervous system (CNS).

The individual and combined effects of MP and ALLO to control the clinical score of murine experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), to preserve spinal cord tissue integrity, modulate cellular infiltration and gliosis, promote remyelination, and modify the expression of Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) were evaluated. In silico studies, to deep insight into the mechanisms involved for the treatments, were also conducted.

MP was the only treatment that significantly reduced the EAE severity, infiltration of inflammatory cells and ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1) expression respect to those EAE non-treated mice but with no-significant differences between the three treatments. MP, ALLO and MP+ALLO significantly reduced tissue damage, AhR expression, and promoted remyelination. Overall, these results suggest that MP, with or without the co-administration with ALLO is an effective and safe strategy to reduce the inflammatory status and the progression of EAE. Despite the expectations of the use of ALLO to reduce the inflammation in EAE, its effect in the dose-scheme used herein is limited only to improve myelination, an effect that supports its usefulness in demyelinating diseases. These results indicate the interest in exploring different doses of ALLO to recommend its use.

ALLO treatment mainly maintain the integrity of the spinal cord tissue and the presence of myelin without affecting NI and the clinical outcome. AhR could be involved in the effect observed in both, MP and ALLO treatments. These results will help in the development of a more efficient therapy for MS patients.

Keywords

- neuroinflammation

- remyelination

- allopregnanolone

- methylprednisolone

- AhR

- glucocorticoids

- neurosteroids

- intranasal

Multiple sclerosis (MS) a chronic autoimmune and demyelinating disease characterized by significant axonal injury and neuronal pathology, remains one of the leading causes of neurological disability in young adults, with increasing incidence and prevalence worldwide [1]. Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) is the most commonly diagnosed phenotype. It is characterized by recurrent episodes of Neuroinflammation (NI) and new lesions, with progressive loss of neurons and axons [2]. Currently, relapses in RRMS patients are treated with high doses of methylprednisolone (MP) administered orally or intravenously [3]. While it is known that effective control of NI favors recovery from MS relapses, recent evidence suggests that such control must be finely tuned. Indeed, myelin regeneration requires a delicate coordination between immune activation and regulation in complex interactive processes that are not yet fully understood [4].

Although MP reduces the severity of relapses and delays disease progression [5], the high doses required have adverse effects over time and may increase the risk of other morbidities [6]. To mitigate these drawbacks, the enhanced efficacy of intranasally administered MP for the treatment of MS relapses was demonstrated in a mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE). Intranasally administered MP reduced EAE clinical scores and NI more effectively than the intravenous route [7]. These results are consistent with previous reports that higher levels of dexamethasone were found in various brain regions of mice after intranasal (IN) administration of the steroid compared to intravenous administration. Similar results were observed when comparing MP administration by both routes assessed by immunofluorescence and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis [8].

On the other hand, RRMS patients have low peripheral allopregnanolone (ALLO) levels that can be restored by the exogenous administration of this neurosteroid, that also exhibited anti-inflammatory properties and promote remyelination. Furthermore, ALLO has been shown to have some anti-inflammatory properties while promoting remyelination [9, 10]. Here, the use of IN ALLO is proposed as a treatment to mitigate the progressive degenerative physiopathology associated to the EAE, alone or in combination with MP. Thus, we hypothesize that the addition of this neurosteroid, which is approved for human use in pathologies such as postpartum depression, could synergize the anti-inflammatory capacity of MP and promote myelin recovery in the EAE model as previously considered. Considering the higher efficiency of the IN route to reach the central nervous system (CNS) [7, 8], we explore herein the usefulness of IN administration of ALLO.

Control of NI is not only critical in RRMS, but is also essential in numerous

autoimmune diseases [11]. The Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a ligand-activated

transcription factor of the basic helix-loop-helix superfamily, has been proposed

as a modulator of inflammation [12]. In addition, neuroactive steroid analogues

of ALLO, such as 3

This study was aimed to evaluate the IN administration of MP plus ALLO as a therapeutic approach to control the severity of EAE and reduce the pathological outcome by controlling NI and promoting myelination.

Mice were obtained from the animal facilities at the Instituto de

Investigaciones Biomédicas (IIB), UNAM, Mexico City, Mexico. They were housed

at the same institution and maintained at 22

All experimental procedures, including anesthesia and euthanasia, were conducted in accordance with national (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) and institutional regulations for the use and care of laboratory animals, following the protocol approved by the IIB, UNAM, Mexico (approval number ID 140).

The handling of the animals was carried out to minimize their suffering and stress. The animals were killed by administering a lethal dose of ketamine (100 mg/mL) and xylazine (100 mg/mL).

EAE was induced in female mice as described previously [7]. Briefly, 14–16-week-old female C57BL/6J mice weighing at least 18 g were used. Mice were given ad libitum food and water before and during the experiments and were maintained under a 12:12 hours light/dark cycle. Each animal received 200 mg of a 1:1 emulsion of complete Freund’s adjuvant (263910 and 231141, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and MOG35-55 peptide (LT12018, LifeTein, Somerset, NJ, USA) at 4 sites distributed along the dorsal flanks. Mice received an intraperitoneal dose of 300 ng pertussis toxin (180, Listlabs, Campbell, CA, USA) and a second dose of pertussis 48 hours later. Thereafter, mice weight, and clinical EAE score signs of each animal were measured daily until euthanized.

The clinical score was assessed by mice observation according to the criteria previously reported. Briefly, at clinical score cero (0) mice have no clinical signs, with normal gait and tail movement, tail can wrap around a round object if mouse is held at the base of the tail. At clinical score 1, mice have partially limp tail, with normal gait but the tip of the tail droops. At clinical score 2, mice have a paralyzed tail, with normal gait and complete tail drops. At clinical score 3, mice have hind limb paresis and uncoordinated movement, with uncoordinated gait, tail limps and hind limbs still respond to pinching (Supplementary Table 1). Complete clinical score criteria can be consulted at Bittner et al., 2014 [17].

All treatments were intranasally given following the protocol described by Hanson et al. [18]. In brief, mice were held, completely immobilizing the forelimbs and head with the non-dominant hand. While maintaining the grip on the scruff, the mice back was positioned on the holder palm and the chin was maintained as close as possible to a 180-degree angle. While each mouse was in this position, the treatments were administered using a 100 µl micropipette (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) making sure that the micropipette tip entered to the mouse nostril. For each mice nostril, the total administered volume was 10 µL, so the final volume in which each mouse treatment was dissolved was 40 µL.

A commercially available formulation of methylprednisolone sodium succinate

(Solumedrol, Pfizer, Manhattan, NY, USA) was administered at a concentration of

200 mg/kg as described elsewhere [7]. ALLO (PA STI 004670, Pharmaphilliates,

Haryana, India) was administered at the reported optimal dose of 10 mg/kg diluted

in sulfobutyl ether-

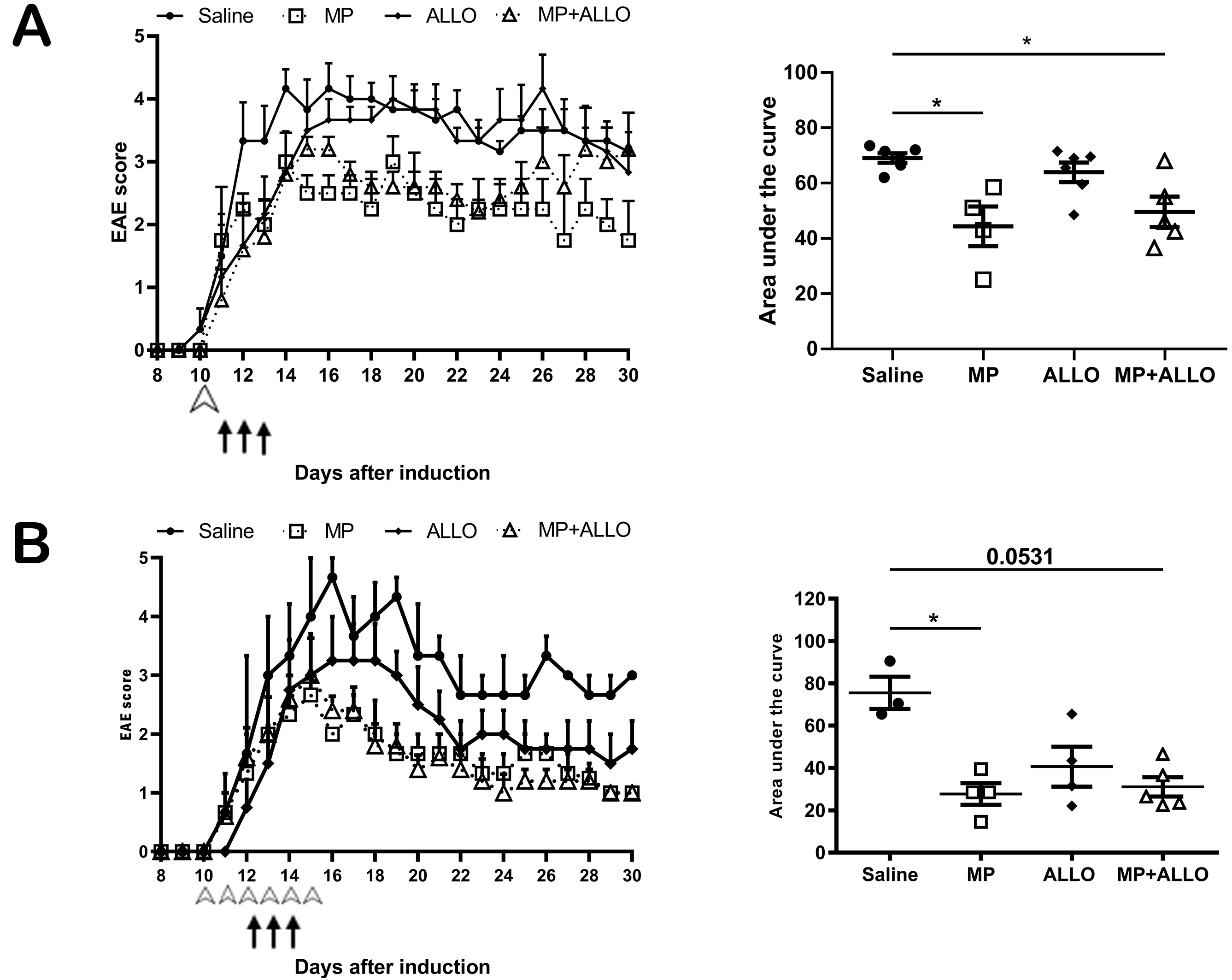

Two experiments with five groups of 3 to 6 mice each were performed. In each experiment groups were assigned as follows, naive mice group (naive), saline solution (SS) treated mice group (saline), MP treated mice group, ALLO treated mice group and MP+ALLO treated mice group.MP treated group received three doses of MP, which were administered for three consecutive days, when mice reached level two in the EAE clinical score, as previously described [7]. One (Fig. 1A) or six doses (Fig. 1B) of ALLO were administered on day 10 when mice had no symptoms, with or without the same MP dosage. Results shown in Figs. 2,3,4,5,6 correspond to the experiment shown in Fig. 1B.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

EAE clinical score of mice from two experiments. (A) Daily

recording of EAE clinical score in treated and non-treated mice. White arrow

points a single dose of ALLO 10 days after EAE induction, while the black arrows

point a three-day administration of MP, the same administration scheme was used

for the MP+ALLO group. (B) Daily recording of EAE clinical score in treated and

non-treated mice. White arrow points a six-day dose of ALLO 10 days after EAE

induction, while the black arrows point a three-day administration of MP, the

same administration scheme was used for the MP+ALLO group. For A and B, three to

five mice were included in each group, error bars indicate SEM, *p

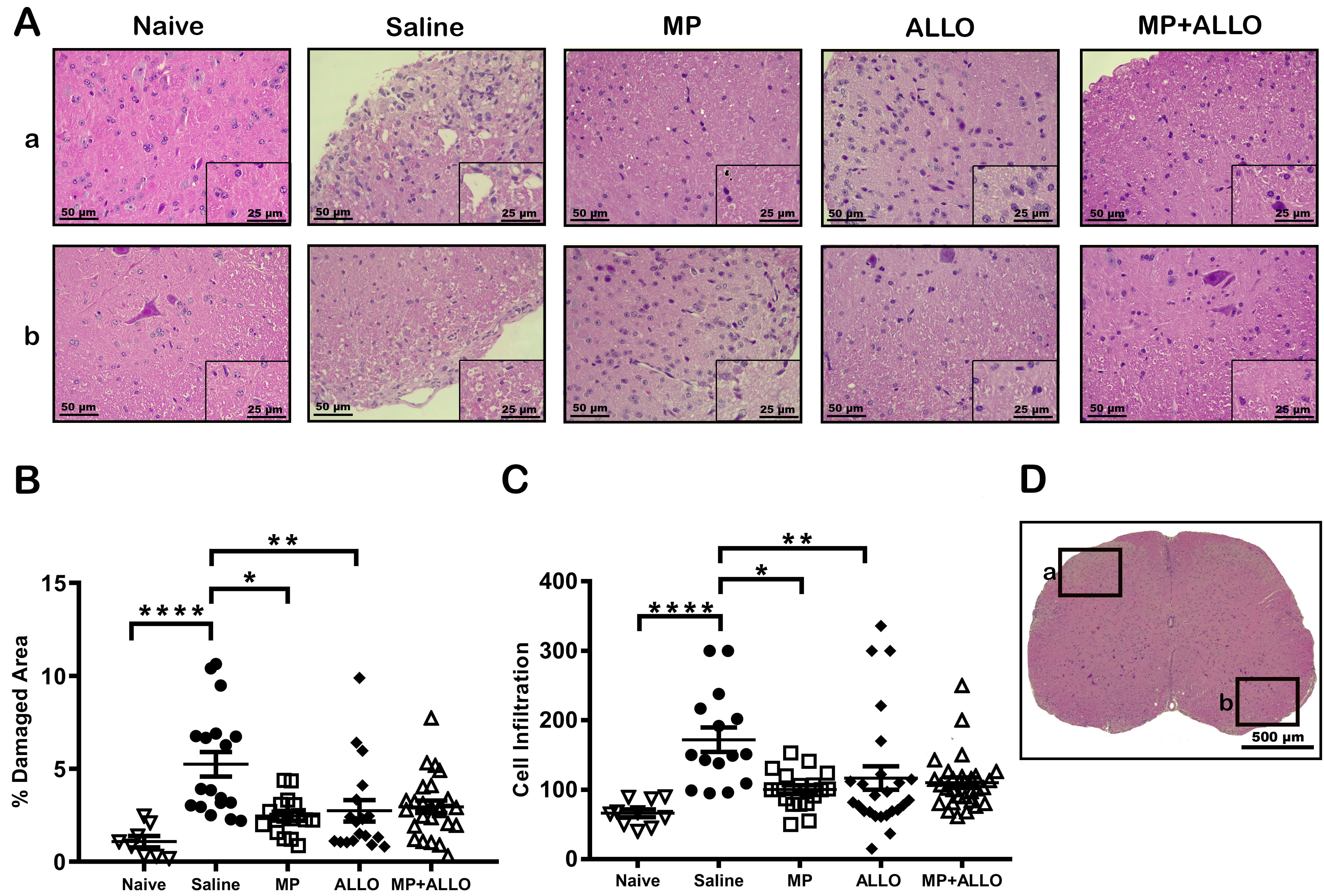

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Histologic analysis of lumbar spinal cord sections. (A)

Representative images of the analyzed areas of different zones (a and b)

highlighted at D (Black squares pointing different areas in the lumbar spinal

cord sections). MP, ALLO and MP+ALLO treatments diminished the EAE effect on the

tissue integrity and the inflammatory cellular infiltrate. Scale bars, 50

µm and 25 µm (A) and 500 µm (D). (B,C) Mean of damaged area and

cell infiltration in 3 to 6 mice from each group. Analyzed data corresponds to

the experiment showed in Fig. 1B, for each group, according to the availability

of the material 2 to 4 sections were analyzed, naive n = 4, saline n = 3, MP

n = 4, ALLO n = 4, MP+ALLO n = 5, Kruskal-Wallis Test and for group differences

an unpaired t test with Welch correction, error bars indicate SEM,

*p

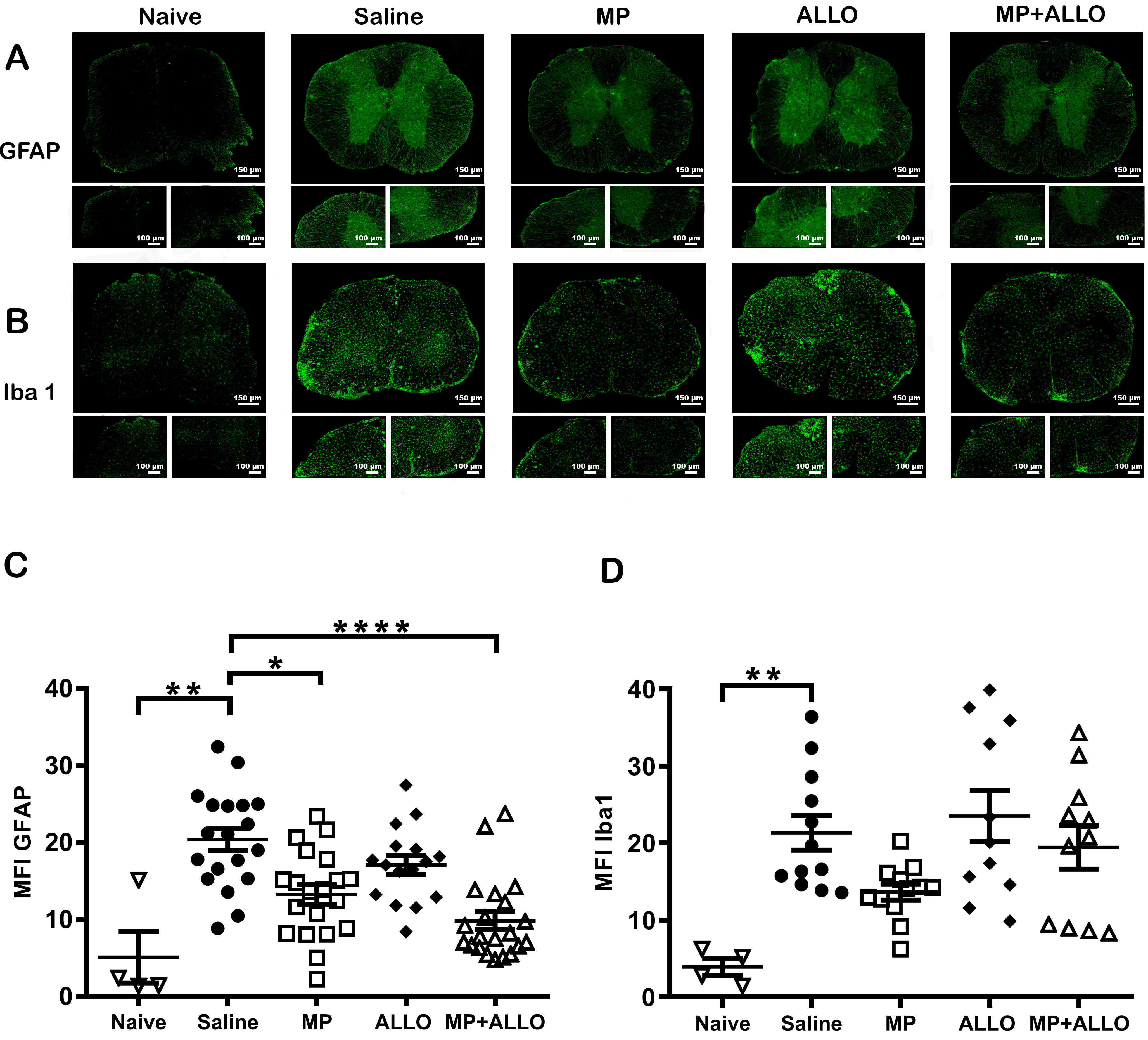

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

GFAP and Iba1 expression. (A,B) Lumbar spinal

cord sections photographs (20x and 40x). Scale bars, 150 µm and 100

µm respectively. (C,D) Mean MFI of GFAP and Iba1

expression in spinal cord sections in 3 to 6 mice from each group. Analyzed data

corresponds to the experiment showed in Fig. 1B, for each group, according to the

availability of the material 2 to 4 sections were analyzed, naive n = 4, SS

n = 3, MP n = 4, ALLO n = 4, MP+ALLO n = 5, for GFAP Kruskal-Wallis Test

and for group differences an unpaired t test with Welch correction, for

Iba1 One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, error bars indicate SEM,

*p

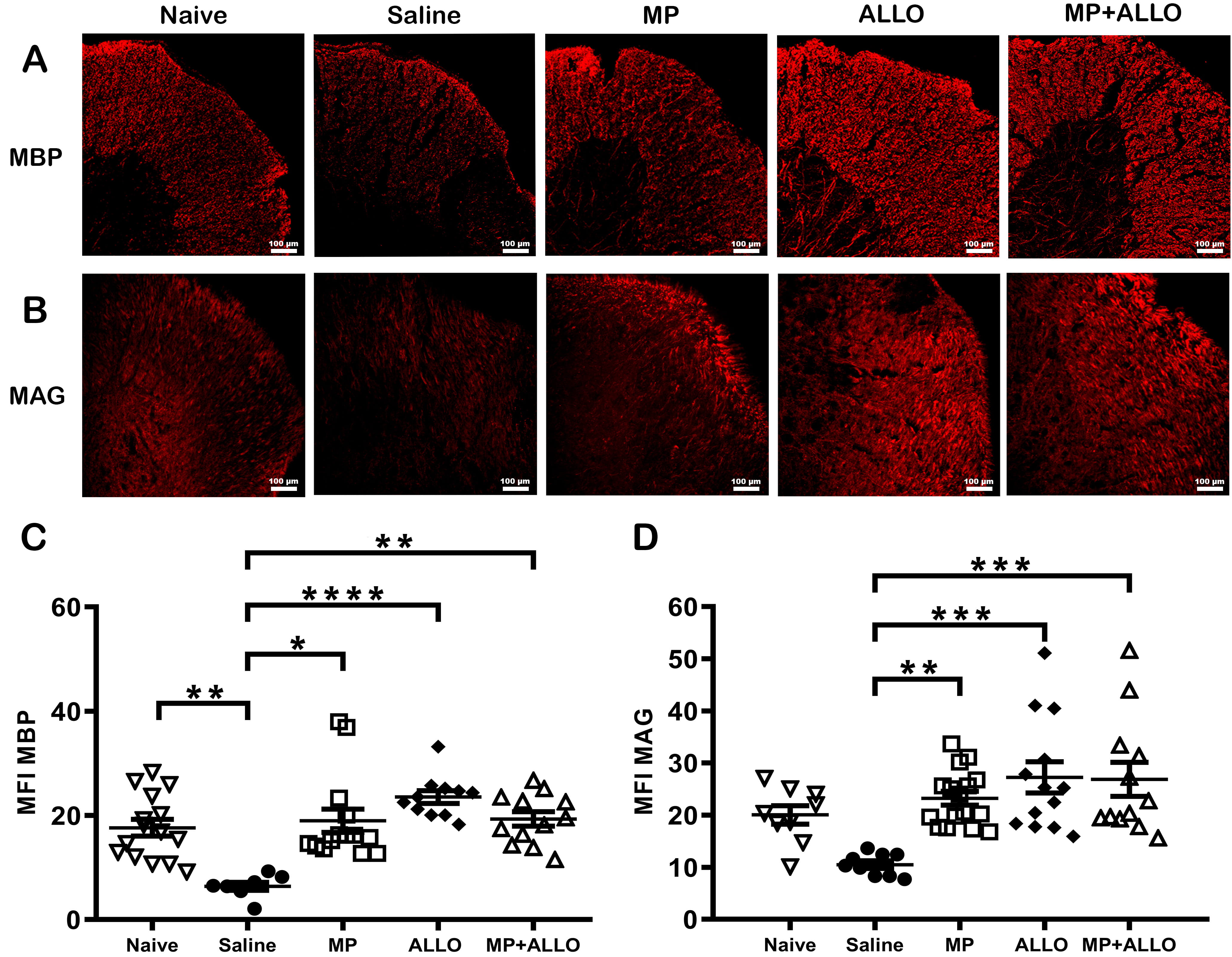

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Expression of MBP and MAG in lumbar spinal

cord sections. (A,B) Micrographs of spinal cord sections at 20x magnification.

MP, ALLO and MP+ALLO treatments rise the expression of MBP and

MAG in comparison to the SS treated group. Scale bar, 100 µm.

(C,D) MFI of MBP and MAG expression in spinal cord sections in

3 to 6 mice from each group. Analyzed data corresponds to the experiment showed

in Fig. 1B, for each group, according to the availability of the material 2 to 4

sections were analyzed, nave n = 4, SS n = 3, MP n = 4, ALLO n = 4, MP+ALLO n =

5. MBP data were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis Test followed by the

unpaired t test with Welch correction. MAG data were analyzed

usinf the ome-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test. Mean of the MFI was included

with an error bar that indicates the SEM, *p

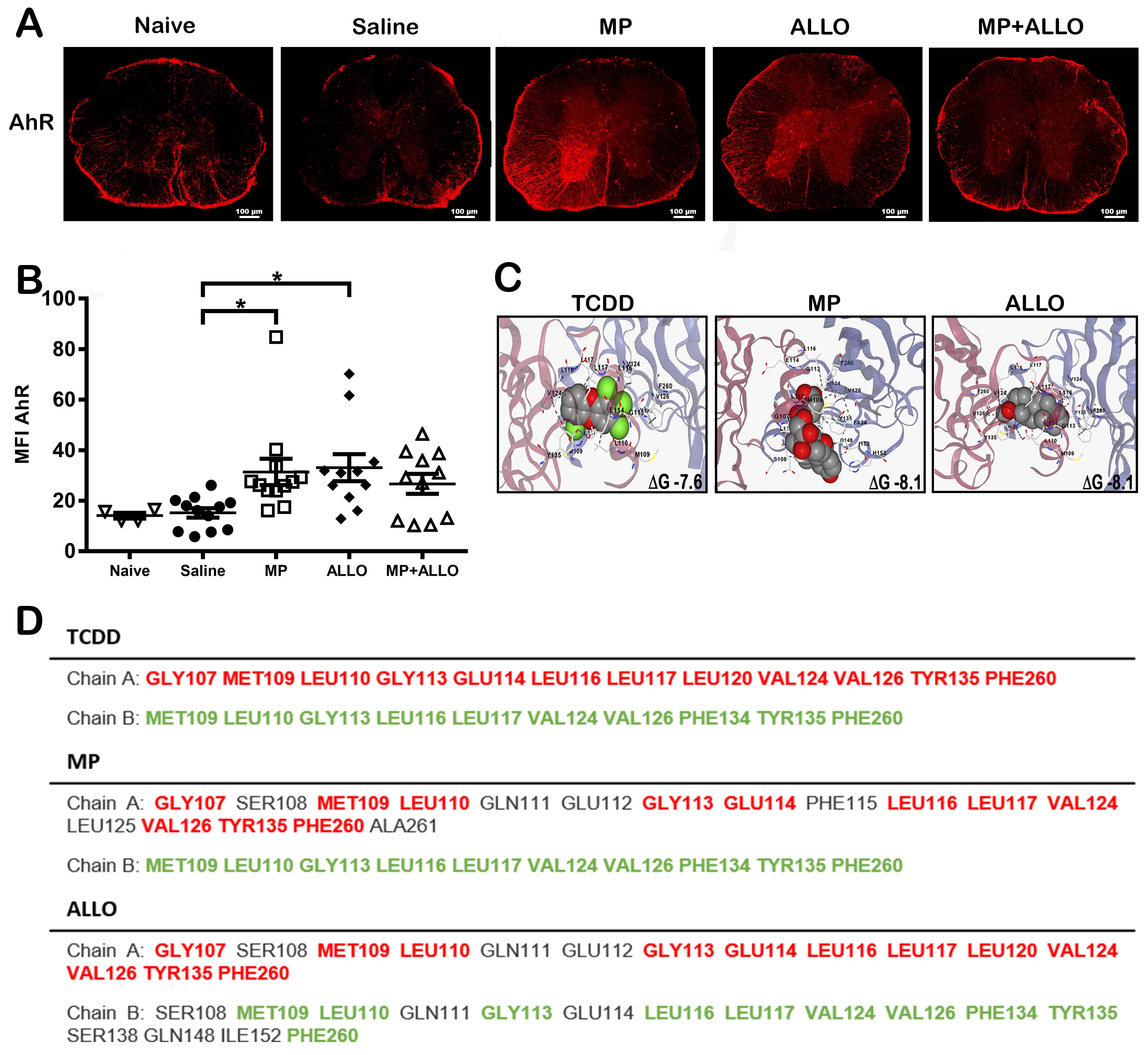

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

AhR expression and ligand interactions. (A) AhR expression in

spinal cord sections. MP, ALLO and MP+ALLO treatments rise the expression of AhR

in comparison to the SS treated group. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) MFI analysis

of AhR expression in spinal cord sections in 3 to 6 mice from each group.

Analyzed data corresponds to the experiment showed in Fig. 1B, for each group,

according to the availability of the material 2 to 4 sections were analyzed,

naive n = 4, sline n = 3, MP n = 4, ALLO n = 4, MP+ALLO n = 5,

Kruskal-Wallis Test and for group differences an unpaired t test with

Welch correction, error bars indicate SEM, *p

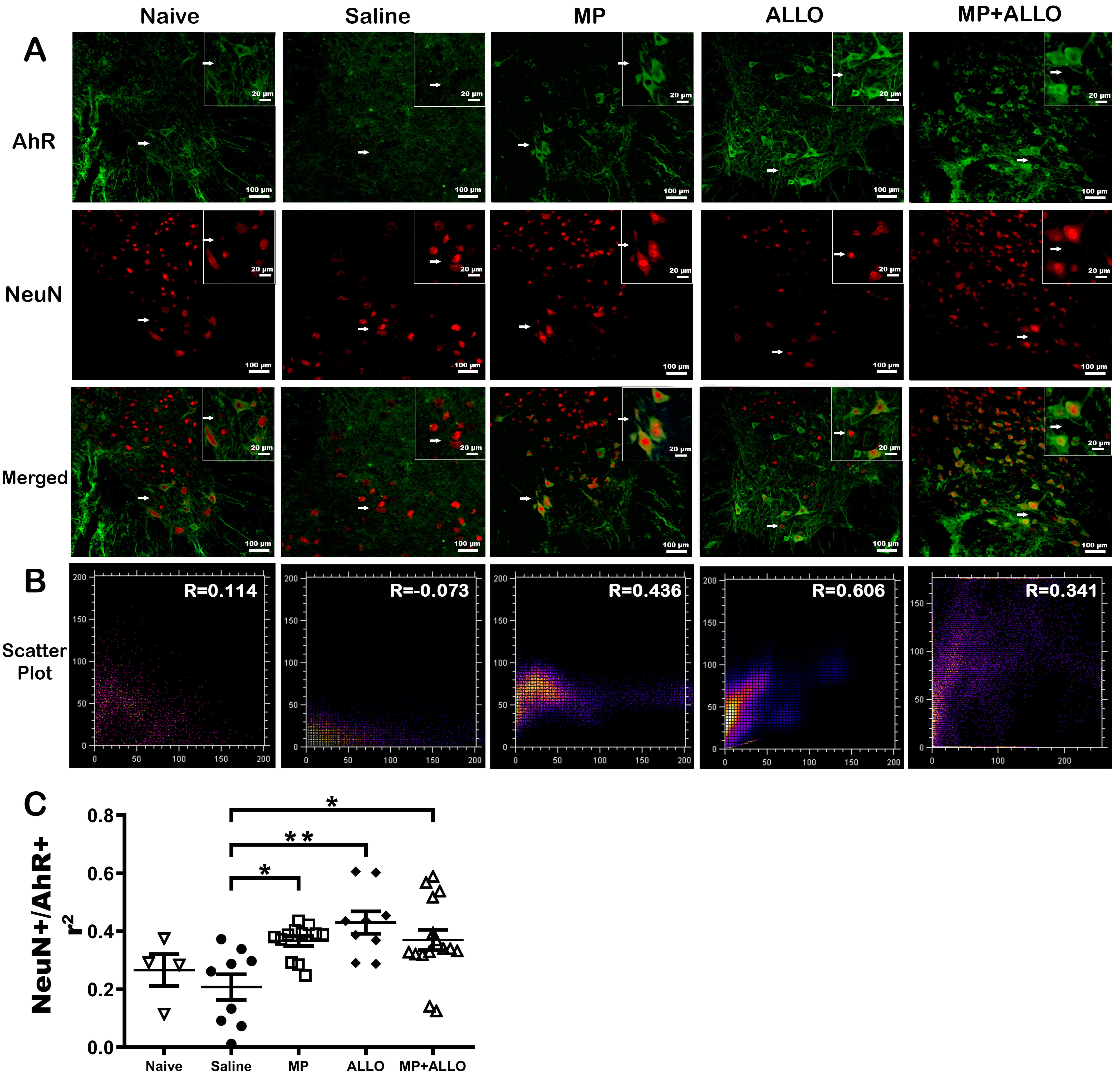

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Colocalization of NeuN and AhR. (A) Micrographs of spinal cord

sections at 40x and 60x magnification. Green AhR expression, red NeuN expression

and blue DAPI. MP, ALLO and MP+ALLO treatments promoted the colocalization of AhR

and NeuN, compared to the SS treated group. Scale bars, 100 µm and 20

µm respectively. (B) Scatter plot of AhR and NeuN colocalization. (C)

Analysis of AhR and NeuN colocalization by Pearson’s Correlation analysis in

spinal cord sections in 3 to 6 mice from each group. Analyzed data corresponds to

the experiment showed in Fig. 1B, for each group, according to the availability

of the material 2 to 4 sections were analyzed, naive n = 4, SS n = 3, MP n =

4, ALLO n = 4, MP+ALLO n = 5, One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test, error bars

indicate SEM, *p

Mice were euthanized on day 30 after EAE induction and tissues were stored for further processing. Briefly, mice were euthanized under deep anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine. Mice were bled and sera was collected and frozen at –80 °C for cytokine quantification. Immediately after bled, mice were perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C to fix tissues. Spinal cord sections were obtained, and lumbar fractions were used for histological analysis by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or immunofluorescence (IF) labeling.

After dehydration and paraffin embedding, lumbar spinal cord fractions were cut into 5-µm slices. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in 100–75% gradient ethanol, and stained with H&E (Cat. ab245880, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) to characterize tissue damage. Images were acquired using a Leica DM500 microscope with a Leica ICC50 digital camera (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were analyzed for tissue integrity and inflammatory infiltrate using Fiji, a distribution of the open-source software ImageJ 1.54i (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA) [20]. Briefly, tissue integrity was assessed by analyzing four areas per lumbar spinal cord section on photographs at 10x magnification. To analyze only the tissue contained on each photograph, the total tissue area of each section was delimited using the “Polygon Selection” tool [20]. Then, using the “Color Threshold” tool, each photo was optimized for binary visualization, white for the tissue areas and black for non-tissue areas, making sure that the “Dark background” and “B&W” boxes were selected. Finally, the “Analyse Particles” tool [21] was used to measure the total stained and unstained areas. The unstained spaces, corresponding to the damaged tissue (black sections) were deployed in the “% area” column in the emergent window. The number of infiltrating cells was assessed by counting the stained nuclei in four areas per lumbar spinal cord section on photographs at 40x magnification with the “Multi-Point” tool of Fiji, which allows adding a small mark on counted nuclei.

Upon fixation, lumbar spinal cord fractions were embedded in Tissue-Tek (Cat. DBK-4583, Dibbiotek, Mexico City, Mexico) for further cryo-sectioning using a Leica CM1860/CM1860 UV cryostat (Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse, Germany). Briefly, 20 µm sections were preserved in phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) 1x until IF labeling, as reported elsewhere [7].

The following antibodies were used for immunostaining: Iba1, microglia and macrophage marker, 1:200 goat anti-Iba1 (ab5076, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1:1000 donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 (ab150129, Abcam); glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), astrocyte marker, 1:500 rabbit anti-GFAP (Z0334, Dako, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 1:500 goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (A11008, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA); myelin basic protein (MBP): 1:500 rabbit anti-MBP (ab40390, Abcam) and 1:500 goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (A11012, ThermoFisher); myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG): 1:500 rabbit anti-MAG (D4G3, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and 1:500 goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (A11012,ThermoFisher); AhR: 1:500 mouse anti-AhR (MA1-514, ThermoFisher) and 1:500 goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A28175, ThermoFisher); NeuN: 1:500 rabbit anti-NeuN (702022, ThermoFisher) and 1:500 goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (A11012, ThermoFisher). At the end of the incubation time, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (P3696, ThermoFisher) was added to each section to visualize nuclei.

Sections tissues analyzed by immunofluorescence were photographed using a Nikon AX/AX R confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) analysis was performed using Fiji [19]. Briefly, for each analyzed photograph, the “Split Channels” tool was used to separate color channels, and the selected marker labeling was analyzed. Then, the “Measure” tool was used to assign the MFI value for each photograph, which corresponds to the “Mean” value in the resulting emergent window.

The molecular structure of Mus musculus AhR was obtained from Protein Data Bank [22]. Both MP and ALLO structures were obtained from PubChem (MP PubChem CID 23680530, ALLO PubChem CID 92786). For molecular docking analysis and docking reconstruction images, blind docking was performed using the online molecular docking tools CB-DOCK and CB-DOCK2 (http://clab.labshare.cn/cb-dock/ and https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/index.php) following the procedure previously reported [23, 24].

The colocalization of NeuN+/AhR+ was performed using the “JACoP” and “Colocalization Finder” plugins [25]. Briefly, on each analyzed section, the color channels were separated so that the green (AhR+) and red (NeuN+) channels could be visualized individually. Subsequently, the “JACoP” plugin was used to calculate the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, while the “Collocation Finder” plugin was used to generate the scatter plots corresponding to each section.

Data were first tested for a normal distribution using the Kolmogorov and Smirnov test and tested for homogeneity of variance using Bartlett’s method. If data were normally distributed, one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used with a post hoc Tukey test. If data were not normally distributed, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis Test (Nonparametric ANOVA) was used and the statistically significant differences between groups were estimated using the Unpaired t test with Welch correction.

All statistical analyses were performed with Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.,

San Diego, CA, USA). Results were considered statistically significant at

p

In a previous study, Rassy et al. (2020) [7] demonstrated that MP intranasally administered reduced signs of EAE more effectively than the intravenous route. The effect of IN administration of MP and ALLO, both individually and in combination, was evaluated herein. As shown in Fig. 1A,B, MP and MP+ALLO treatments significantly reduced the clinical EAE score compared to the saline-treated group. Meanwhile, ALLO treatment only tends to diminish the EAE score.

The lumbar region of the spinal cord was analyzed since it is the most affected region in EAE. As shown in Fig. 2A, the induction of the model significantly increased cellular infiltration and the percentage of damage areas. The three treatments reduced the size of the damaged areas, but cellular infiltration was significantly reduced only in the lumbar section of animals treated with MP and MP+ALLO.

The expression levels of GFAP and Iba1 in astrocytes and microglia, respectively, are considered indicators of glial activation. As shown in Fig. 3, treatment with MP and MP+ALLO significantly reduced the MFI values of GFAP compared to saline-treated mice. Iba1 expression was significantly reduced only in MP-treated animals.

Loss of the myelin sheath is a hallmark in EAE. As shown in Fig. 4, all treatments induced recovery of MBP and MAG expression, both structural components of myelin. A slightly higher effect was induced in ALLO- and MP+ALLO-treated mice.

To evaluate if differences in decreasing severity by the two steroids tested, the possible participation of the level of receptors expressed was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 5A,B, both MP and ALLO increase the expression of AhR to a similar extend, a receptor involved in myelinization and the regulation of inflammation. This increase could be resulted by interaction of MP and ALLO with this receptor, a feature supported by the theoretical predictions when both drugs are structurally compared with 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), also known as dioxin, that is a potent agonist of AhR (Fig. 5C,D).

AhR has been reported to have different functions depending on the type of cells and its location, either cytoplasmic or nuclear. As shown in Fig. 6, all treatments promoted nuclear translocation of AhR in neurons as measured by its colocalization with NeuN, a neuronal nuclear marker. It can also be observed that EAE decreased AhR nuclear translocation.

MP has been recognized as an effective alternative to reduce the pathological signs in MS and EAE (a well-studied RRMS model), by reducing immune cell infiltration and demyelination [7]. It is also known that ALLO expression is downregulated in RRMS adult patients [10, 26], a neurosteroid involved in the myelination in the CNS [9]. On the other hand, we previously demonstrated that the IN route is more effective than the intravenous to reach the CNS [8]. Based on this information, herein the evaluation of the efficacy of IN administration of MP and ALLO, alone and in combination, was performed to control EAE pathologic signs.

Consistent with previous results [7], MP intranasally administered effectively reduced the peak value of clinical scores in two independent experiments performed (Fig. 1). ALLO alone did not affect the clinical score in EAE mice, but used in combination with MP, did not diminish the beneficial effect of the latter, used before or after the appearance of the symptoms neither at one nor at six doses administered. The absence of effect on clinical outcomes induced by ALLO is compatible with its lower anti-inflammatory capacity relative to the high potency of MP [27, 28, 29]. Indeed, MP effectively controlled the cellular infiltration and down-regulate the gliosis induced in EAE control mice [30, 31]. Gliosis, directly involved in RRMS progression [32], is characterized by activation of astrocytes and microglia that overexpressed GFAP and Iba1, respectively [33, 34, 35, 36, 37]. The lack of effect of ALLO on the clinical improvement of the mice is accompanied by a sustained inflammation that is manifested by the maintenance of the increased inflammatory infiltrate in EAE together with the increased levels of astrocytes and microglia activation. However, Noorbakhsh et al. 2011 [26], reported the effectiveness of ALLO daily administered for 30 days, from the induction of the model to the euthanasia of the animals, in controlling the clinical score in EAE mice. This sustained schedule probably compensates for the lower anti-inflammatory capacity of ALLO, allowing the clinical improvement of mice.

Despite the low anti-inflammatory capacity of ALLO, it could reduce the areas of damage in the spinal cord and increase the level of the expression of the Aryl receptor and myelin expression. This profile is compatible with the capacity of ALLO to modulate the specific immunity elicited against myelin in EAE that could be overridden by the sustained increased global inflammation. This possibility must be further explored.

Another point that merit comments are the possible effects of steroids and neurosteroids on oligodendrocytes. These cells produce myelin, the protein that wraps around nerve fibers essential to promote signal transmission. Under neuroinflammatory conditions, that prevail in MS and EAE, oligodendrocytes become dysfunctional, leading to myelin damage and axonal degeneration, that affect white and grey matter of the CNS. Under pathological conditions such as demyelinating injury, several neuroactive steroids, including ALLO, have shown remyelinating effects [38]. In this study the possibility of myelin regeneration by treatment with MP and/or ALLO was investigated. We found increased expression levels of the MBP and MAG, more significantly in mice treated with ALLO than with MP. The effective anti-inflammatory capacity of MP may favor the increase level of the expression of both myelin proteins. On the other hand, the remyelinating effect of ALLO could be mediated by its interaction with aminobutyric acid receptors A (GABAA) receptors expressed in precursor and mature myelinating cells since it occurs on an exacerbated cellular infiltration and gliosis, a finding that point to the potential utility of ALLO as a therapy to improve RRMS patients.

It has been reported that the deletion of AhR, a highly conserved receptor expressed on a variety of cells, including resident CNS cells such as oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, microglia, and neurons [39, 40], expressed in microglia inhibit the remyelination [41]. In addition, in the CNS, AhR has been implicated in the modulation of NI, cell proliferation, and myelination [14, 15, 16, 42]. Considering that AhR receptors could be involved in the increase of myelin proteins induced by both steroids [41, 43], the outcome of the treatments on the expression of AhR was tested. The three treatments, MP, ALLO and MP+ALLO, increased AhR expression to a similar extent, that could be due to their high affinity observed in the molecular docking analysis (Fig. 5), which is even higher than its specific agonist TCDD. On the other hand, several functions of AhR have been described in CNS resident cells, depending on whether AhR is expressed in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus [44]. As shown in Fig. 6, EAE induction inhibited AhR translocation to the nucleus of spinal cord neurons, a finding that is accompanied by the reduced levels of MBP and MAG in untreated or saline-treated mice that can be counteracted by ALLO administration even more effective than the other treatments. This nuclear translocation could be mediated by the GABAergic pathway, that has been reported to trigger remyelinating communication between neurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells [45]. Indeed, several reports support our findings and highlight the beneficial effects of AhR overexpression and activation in demyelinating pathologies. It is worthy to mention that AhR depletion or downregulation of its expression promotes not only NI, but also demyelinating pathologies, locomotor defects, and altered myelin structure [16, 43]. Overall, our findings sustained that AhR could contribute to the myelinating effects induced by both MP and ALLO, while the effective anti-inflammatory properties of MP could favor the induced remyelination.

This study highlights the efficacy of MP intranasally administered to effectively control the NI reducing the severity of EAE pathology in mice, whilst IN ALLO treatment mainly maintain the integrity of the spinal cord tissue and the presence of myelin without affecting NI and the clinical outcome. Different mechanisms could underlie the MP and ALLO effects on EAE, but part of them could be mediated by the increased expression of AhR, a receptor that has been reported to have multiple functions under different physiological and pathological conditions whose participation merit to be further explored. These results will help in the development of a more efficient therapy for MS patients.

Data and imaging of the datasets generated in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

ES, GF, HB, and MATR designed the study. CÁG, RGF, JAEC, and INPO performed the research. ES, CÁG, and INPO analyzed data. ES, GF, MATR, and INPO drafted the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Care and Animal Use Committee (CICUAL, protocol ID 140) at the IIB-UNAM, following the Mexican regulation (NOM 062-ZOO-1999) and in accordance with the recommendations from the National Institute of Health of the USA (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals).

We gratefully acknowledge PhD Marisela Hernández, Gonzalo Acero and MVZ Georgina Díaz Herrera for her technical support and to the “Unidad de Modelos Biológicos” of the IIB, UNAM, Mexico for animal lodging and handling. Also, we acknowledge the CONAHCyT Grant 3004601 to INNNMVS for the confocal microscope facilities usage.

This research was funded by the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías: CY002261 FRONTERAS, Dirección General de Personal Académico, UNAM: PAPIIT IN207720, IN211823; the Institutional Program “Programa de Investigación para el Desarrollo y la Optimización de Vacunas, Inmunomoduladores y Métodos Diagnósticos del IIBO” (PROVACADI, UNAM).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2912420.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.