1 Mackenzie Cancer Research Group, Department of Pathology and Biomedical Science, University of Otago Christchurch, 8011 Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand

2 Haematology Research Group, Department of Pathology and Biomedical Science, University of Otago Christchurch, 8011 Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand

Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are innate immune cells that exert far reaching influence over the tumor microenvironment (TME). Depending on cues within the local environment, TAMs may promote tumor angiogenesis, cancer cell invasion and immunosuppression, or, alternatively, inhibit tumor progression via neoantigen presentation, tumoricidal reactive oxygen species generation and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. Therefore, TAMs have a pivotal role in determining tumor progression and response to therapy. TAM phenotypes are driven by cytokines and physical cues produced by tumor cells, adipocytes, fibroblasts, pericytes, immune cells, and other cells within the TME. Research has shown that TAMs can be primed by environmental stimuli, adding another layer of complexity to the environmental context that determines TAM phenotype. Innate priming is a functional consequence of metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming of innate cells by a primary stimulant, resulting in altered cellular response to future secondary stimulation. Innate priming offers a novel target for development of cancer immunotherapy and improved prognosis of disease, but also raises the risk of exacerbating existing inflammatory pathologies. This review will discuss the mechanisms underlying innate priming including metabolic and epigenetic modification, its relevance to TAMs and tumor progression, and possible clinical implications for cancer treatment.

Keywords

- tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)

- innate priming

- epigenetic modification

- metabolic modification

- cancer

The immune system has classically been divided into two arms—the innate and adaptive systems. This division is based primarily on the type of receptor used to distinguish non-self. Cells of the innate system (namely natural killer cells, granulocytes and monocytes/macrophages) recognise foreign material through expression of multiple pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), whereas cells within the adaptive immune system specifically recognise a single antigen. Although originally thought to operate independently, it has become clear that these two arms of immunity act in concert to provide a powerful and effective system of immunosurveillance [1].

Innate immune cells provide the first line of defense against developing tumors through their capacity to not only rapidly detect and eliminate cancer cells, but also stimulate the adaptive immune response [2, 3]. However, immunogenic heterogeneity in cancer cells can emerge over clonal generations, allowing for the evasion of immunosurveillance [4]. Mechanisms by which the tumor microenvironment (TME) can potently influence both the development and function of immune cells include expression of immune checkpoint inhibitors, generation of immune regulatory cells and selection of immune resistant cancer cells [4, 5]. Further spatial and temporal heterogeneity within the TME generates a complex network of interacting immune, non-immune (e.g., fibroblasts, adipocytes and mesenchymal cells) and malignant populations that exert further influence on the immune system’s ability to eliminate the tumor [4, 6, 7, 8].

Macrophages are members of the innate immune system that are proficient phagocytes and serve as core orchestrators of tumor responses [9]. Driven by immunological cues, recruited monocytes and resident macrophages within the TME can be differentiated into what are termed tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [10, 11, 12, 13]. TAMs represent a major component of the infiltrating immune cells within the TME and have become the focus of increasing research due to their crucial roles in tumor growth, angiogenesis, immune regulation, metastasis and chemoresistance [11, 12]. However, the impact of TAM on tumor progression is not fixed as there is considerable functional and phenotypic plasticity in response to the TME derived signals they encounter. TAMs have been broadly grouped as pro-tumor or anti-tumor based on their phenotype and functional capabilities, and changes in the relative number or distribution of these TAM sub-types have been associated with prognosis in numerous cancers [11, 14, 15, 16]. The functional plasticity of TAMs reflects the metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming that occurs in response to multiple stimulants [17, 18]. However, this reprogramming may not solely reflect exposures to stimulants within the TME.

Recent research has suggested that macrophages can be primed by stimulation prior to their arrival in the local TME, which may further impact their phenotype and functional response, leading to potential clinical consequence [19, 20, 21, 22]. This adds a further layer of complexity to the understanding of immunotherapy response in patients. This review will discuss the relevance of this innate priming to TAMs, describe the underlying mechanisms driving innate priming and outline the implications for cancer treatment.

The first epidemiological data that provided some evidence for the presence of

an innate priming process was provided by studies on recipients of

live-attenuated Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine to prevent

tuberculosis [23, 24]. These studies suggested BCG vaccine induced a broader protection

against diseases other than tuberculosis [23, 24]. In an international survey

consisting of

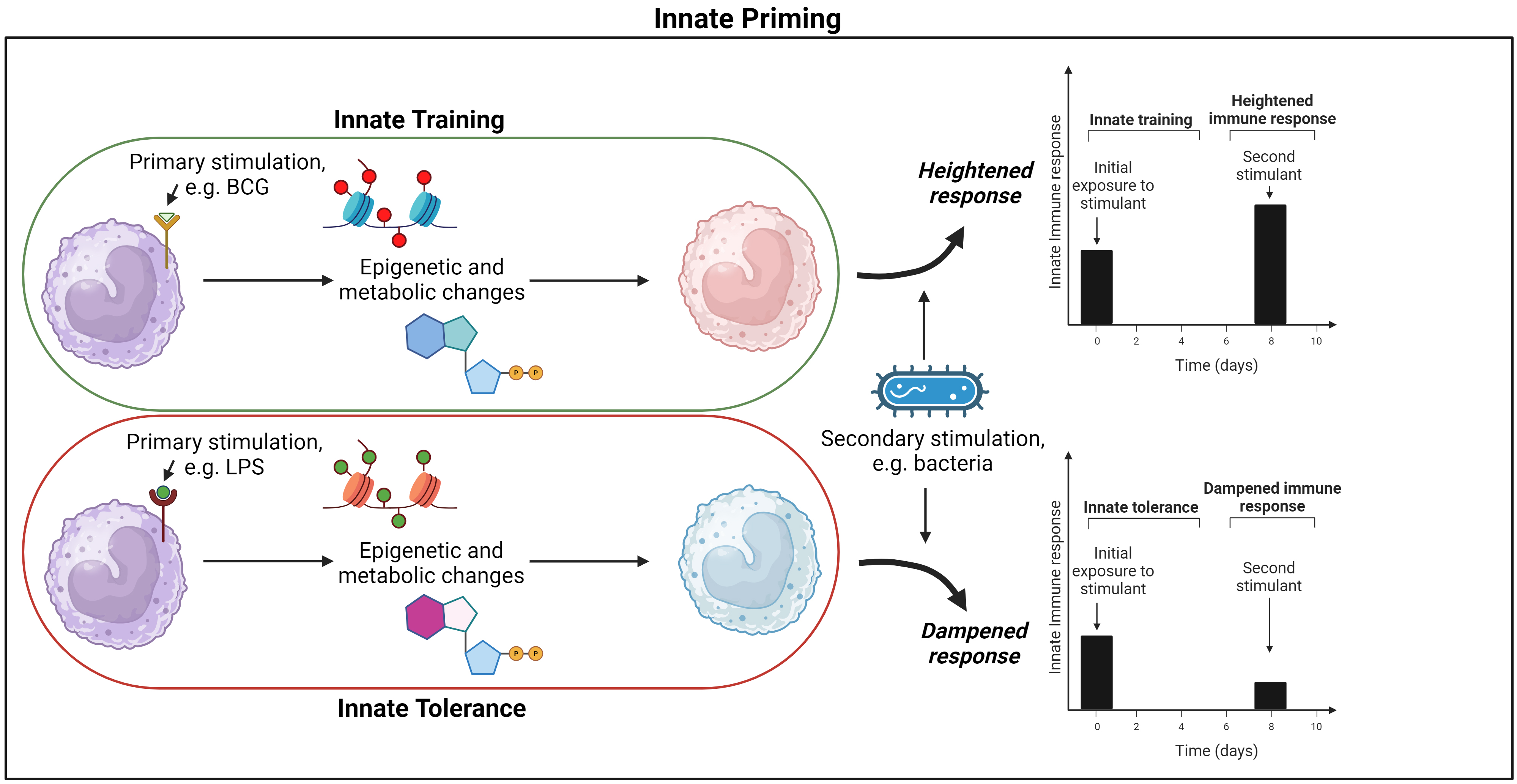

Innate “memory” is often used within literature to discuss lasting changes to innate cell phenotype induced by primary stimulants, but the biological mechanisms underlying this observation differs from those mechanisms involved in adaptive memory. In particular, innate memory does not lead to expansion of a subset of cells that are antigen specific [20, 30]. Instead the term innate memory describes a de facto memory of a primary stimulant. The “memory” is provided by the induced metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming of differentiated and progenitor innate cells, which result in long lasting changes in innate cell phenotype. These reprogrammed cells subsequently have altered responses to a range of secondary stimuli as compared to the original innate cells [19, 20, 21]. In this review, this de facto memory will be referred to as “innate priming”. The functional consequence of the epigenetic and metabolic changes that characterise innate priming can result in innate cells exhibiting heightened or dampened responses to secondary stimulants. Innate priming that results in heightened response to secondary stimulus will be referred to as “innate training” and priming that results in reduced response to secondary stimuli will be referred to as “innate tolerance” (Fig. 1) [31].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Priming of macrophages and functional consequence. Macrophages are activated by a primary stimulant that results in long-lasting epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming, changing the cells phenotypic and functional response to secondary stimulation for a prolonged period; this is termed “innate priming”. If primary stimulation heightens secondary response it is termed ‘innate training’, but if the secondary response is dampened it is termed “innate tolerance”. BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; LPS lipopolysaccharide. Figure created on BioRender.com (https://www.biorender.com/).

A range of exogenous and endogenous compounds have been shown to be capable of

inducing innate training (Fig. 1) [20, 32, 33]. Ex-vivo

During development of innate tolerance, once primary stimulation concludes,

effector genes are silenced instead of being activated prior to secondary

stimulation (Fig. 1). This functional reprogramming results in a dampened innate

immune response [31]. For example, LPS can induce a strong inflammatory response

in macrophages through interaction with receptors including toll-like receptor 4

(TLR4), however, upon re-stimulation, the cells were tolerized and exhibited

reduced production of pro-inflammatory mediators and attenuated TLR activation to

secondary stimulants [26, 38, 39, 40]. Interestingly, if LPS was presented to innate

cells at low concentrations (

The overall status of the current literature is that there are numerous studies describing the occurrence of innate priming with the resultant outcome being either enhanced (termed innate training) or suppressed (termed tolerance) responses to secondary stimulants. The references associated with these particular areas are outlined in Table 1 (Ref. [20, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63]).

| Study reference | |

| Characterising innate training | [20], [26], [32], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [41] |

| Characterising innate tolerance | [20], [26], [31], [38], [39], [40] |

| Induction of innate priming with exogenous compounds | [20], [25], [26], [28], [34], [36], [41] |

| Induction of innate priming with endogenous compounds | [20], [27], [28], [32], [37], [47], [48], [49] |

| Effect of priming with a combination of stimulants | [50], [51], [58] |

| Innate priming increasing TAM tumoricidal activity | [44], [45], [46] |

| Epigenetic regulation of innate priming | [31], [52], [53], [54] |

| Metabolic regulation of innate priming | [20], [31], [55], [56], [57] |

| Clinical implications of innate priming in disease | [20], [25], [28], [29], [41], [49], [59], [60], [61], [62] |

| Cancer Therapies utilising and/or trialling strategies based on or relevant to innate priming | [42], [43], [63] |

TAM, tumor-associated macrophage.

TAMs are innate cells that have functional plasticity and therefore cannot be considered as strictly pro- or anti-tumorigenic. Depending on the immunological context, TAMs can support anti-tumor immune responses through neo-antigen presentation to the adaptive immune system, tumoricidal reactive oxygen species generation, pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and induction of cytotoxicity and apoptosis of transformed cells [14, 15, 16]. Alternatively, they can promote tumor progression through inducing angiogenesis, cell invasion and immunosuppression [11]. In the literature, TAMs are usually reported to have tumor promoting roles [11, 12, 64]. However, exceptions can be found and TAMs have been reported to exhibit a more protective role in melanoma and colorectal cancer [15, 65]. While previous research has clearly demonstrated the contrasting roles TAM can play in the TME, further work is required to fully understand the stimuli that drive the metabolic and epigenetic development of TAMs in a manner that results in either a tumor promoting or suppressing phenotype.

Macrophages have been well characterized as receptive to innate priming and are

the main focus of the literature exploring this biological mechanism. In most

studies investigating innate priming in macrophages, the priming stimulants have

been exogenous, including the BCG vaccine and

Although the literature has predominantly focused on exogenous stimuli in the

context of innate priming, recent studies have also pointed to the role of

endogenous stimuli. oxLDL has been the most studied endogenous stimulant to

induce macrophage priming, but this has now been expanded to include endogenous

compounds such as aldosterone, uric acid and butyrate [20, 27, 47, 48]. In

monocytes, ex-vivo studies have shown that endogenous compounds

including oxLDL induce priming effects similar to those induced by exogenous

stimulants [20, 48]. oxLDL primed macrophages exhibit increased ROS and cytokine

production, glycolytic metabolic modification, and enhanced presentation of

scavenger receptors including CD36 [20, 32]. Moreover, oxLDL stimulation enhances

expression of cytokines such as IL-8, TNF-

The effects of combinations of stimuli is another crucial factor to consider when discussing innate priming, as in-vivo models do not expose the immune system to singular stimulants. Research has shown that although butyrate and oxLDL can individually prime innate cells, when used in combination these priming effects are reduced [20, 27, 50]. This relationship was also observed when training macrophages with metformin and oxLDL, as metformin inhibits glycolytic pathways [51]. The combined impact of stimulants on the immune system is often overlooked and should be an ongoing consideration within studies investigating innate priming. This may be particularly relevant for TAMs due to the complexity of the TME and systemic stresses individuals receiving treatment for cancer experience [4, 6, 7, 8, 72, 73]. Upregulation of endogenous compounds induced by stress, the presence of neoantigens and systemic inflammation that an individual experience from treatment, and the administration of other medications may all influence priming and how TAMs respond within the TME [73, 74, 75]. This demonstrates the necessity of in-vivo and clinical work to explore the impact of innate priming on TAMs and therapeutic outcome.

Studies published to date have shown clear evidence that TAMs can undergo innate priming in response to both exogenous and endogenous stimuli and this may result in enhancement or suppression of anti-tumor and/or therapeutic responses. The references associated with these particular areas are outlined in Table 1.

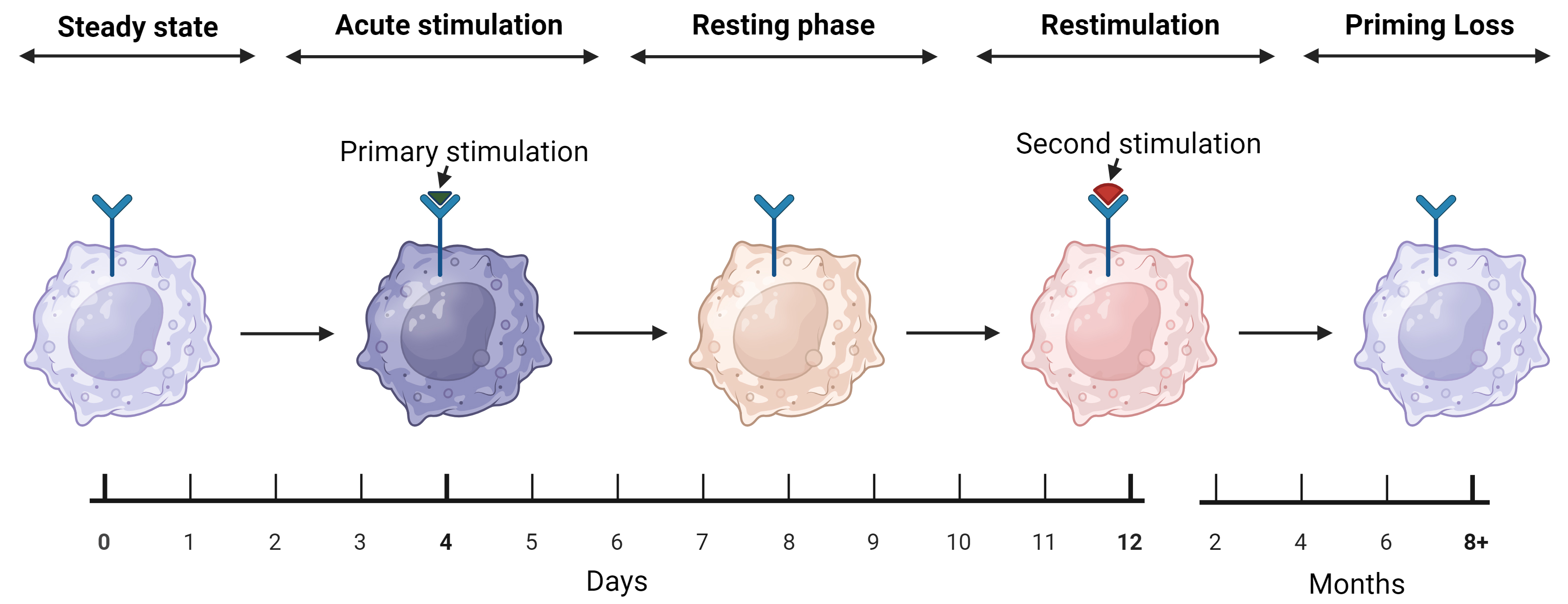

Innate priming can be grouped into four phases—steady state, acute stimulation, resting phase and restimulation (Fig. 2) [31]. Steady state describes unstimulated cells that possess low activity. During acute stimulation, exogenous/endogenous stimulants bind to cytoplasmic and membrane-bound PRRs, which are activated through exogeneous pathogen-associated molecular patterns and/or endogenous damage-derived molecular patterns [31, 76]. These binding events result in alterations to the epigenome, allowing for transcription of effector genes that orchestrate cellular response to the stimulants [76]. With the cessation of stimulation, the cell enters a resting phase, as the effector factors are no longer required. However, the promoter regions of metabolic and effector genes remain open or become silenced [31]. With rechallenge, the primed (trained or tolerized) cell enters the restimulation phase, which is facilitated by altered metabolic activity and enhanced or suppressed effector response, respectively, depending on the previously modified epigenetic landscape [26, 31]. A final phase remains, which is the loss of innate cell priming. Innate priming is not permanent, with heightened responses only lasting for a suggested period of 3–12 months (Fig. 2) [21]. This timeframe is based on epidemiological evidence and needs to be further verified [77]. Furthermore, the way(s) in which innate priming changes during this period also remain to be characterized.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The five stages of macrophage priming. Steady state describes unstimulated macrophages and remains until the innate cell is activated by a stimulant, inducing an immune response that is termed acute stimulation. The primary stimulation induces epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming, changing macrophages phenotype into a primed state. Acute stimulation is followed by the resting phase, where the cell retains its reprogramming but is no longer engaged in an active immune response. The resting phase continues until the macrophage encounters a secondary stimulant, inducing an enhanced (trained) or dampened (tolerized) immune response. The final stage of innate priming is priming loss, as the reprogramming that enhances or dampens secondary response is lost over 3–12 months, returning macrophages back to steady state. Figure created on BioRender.com (https://www.biorender.com/).

Epigenetic modification is the first pillar of innate priming that can affect

TAMs phenotype. The epigenetic landscape drives innate priming, with changes in

chromatin architecture facilitating the promotion and silencing of effector

genes. In the context of innate priming, epigenetic modification exists at

several levels, including methylation, acetylation, enhancer modulation and

transcription of non-coding RNAs. For example, following pattern recognition receptors (PRR) activation

transcription factors nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), signal

transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and/or nuclear factor

kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-

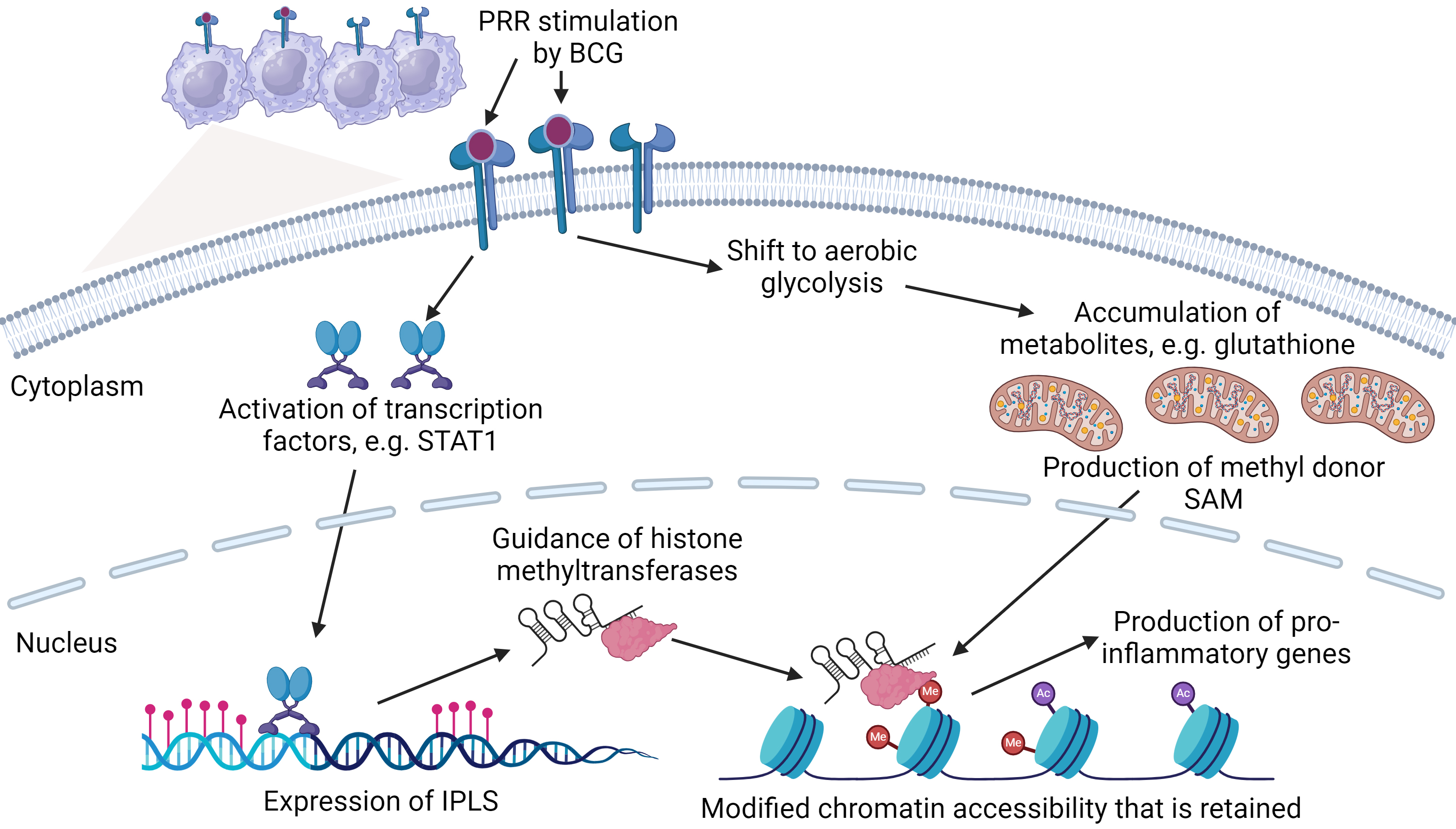

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between primed immunity, epigenetics and metabolism. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) interacts with pattern recognition receptors (PRR) to induce transcription factor(s) such as signal transduced and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) that result in the activation of Immune-gene Priming Long non-coding RNAs (IPLs). IPLs direct epigenetic modifications by guiding proteins including histone methyltransferases to downstream effector genes including pro-inflammatory cytokines. Simultaneously, macrophages shift metabolism to aerobic glycolysis, resulting in the accumulation of metabolites including glutathione. Glutathione promotes the production of s-adenosyl methionine (SAM) that donates methyl groups during epigenetic modification, promoting chromatin restructuring to induce gene expression. Consequently, downstream epigenetic and metabolic pathways are activated and retained, priming macrophages for future encounters with non-specific stimulants. Figure adapted from Fanucchi et al. [31], using BioRender.com (https://www.biorender.com/).

Within the TME, macrophages are differentiated into TAMs that are typically

anti-inflammatory through epigenetic modification [78]. Previous evidence has

shown that tumor-derived exosomes can induce TAM expression of jumonji

domain-containing protein 3 (JMJD3), a H3K27 demethylase that is associated with

anti-inflammatory polarization [79]. However, JMJD3 has also been associated with

inducing macrophage expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to

inflammatory mediators including LPS [80, 81]. This suggests that JMJD3 may be

activated prior to reaching the TME by alternative stimuli, including exogenous

and endogenous compounds or neoantigens, inducing a pro-inflammatory phenotype as

opposed to an immunosuppressive phenotype. However, innate priming may also

induce tumor-promoting epigenetic modification within TAMs. With LPS stimulation,

H3K4 histone methyltransferase SETD4 has been shown to induce expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF

Tumors have been reported to manipulate histone acetylation within TAMs, with a recent study reporting that colorectal cancer cells through the secretion of exosomes can downregulate histone deacetylase (HDAC)11 activity, promoting anti-inflammatory phenotypes [84]. Prior stimulation may also influence anti-inflammatory TAM phenotypes through acetylation mechanisms. Previously, interaction through decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) has been reported to induce histone deacetylation of the class II major histocompatibility complex transactivator (CIITA) promoter, reducing expression of major histocompatibility II (MHC-II) [85]. However, acetylation manipulation can contribute in generating pro-inflammatory phenotypes. Through tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) stimulation, macrophages were reported to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines as HDAC1 was suppressing negative regulation by miR-146a [86]. Moreover, with TL4 activation, increased activity of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and glycolysis results in accumulation of acetyl-coenzyme A, facilitating polarization towards pro-inflammatory phenotypes through histone acetylation [87]. Depending on mode of mechanism manipulating histone acetylation profiles within TAMs, this may promote pro- or anti-tumor phenotypes as the cells arrives within the TME, but further evidence is required before conclusive statements can be made.

Previous evidence has shown that tumors can manipulate DNA methylation within

TAMs through activating ten-eleven translocation 2 by inducing the interleukin-1

receptor/myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (IL1R/MyD88)

pathway, resulting in the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine production

[88]. However, stimulation of macrophages prior to arrival at the TME may also

manipulate TAM methylation profiles. Macrophages stimulated with LPS have been

reported to upregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production through

hypermethylation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) from

DNA-methyltransferase I (DNMT1) [89]. In agreement, a study characterising the

methylation pathway of macrophages exposed to LPS and IFN

Immunometabolism is the second pillar of innate priming and intertwines with the

epigenetic landscape. Typically, primed innate cells utilise aerobic glycolysis

instead of oxidative phosphorylation (Warburg effect), with maintenance of this

metabolic pathway by epigenetic mechanisms fulfilling cellular energetic

requirements [55]. However, immunometabolism extends beyond energy fulfilment,

with metabolic products having active roles in regulating epigenetic enzymes

(Fig. 3) [31]. For example, the accumulation of

Immunometabolism has a pivotal role in modulating the function of TAMs, as the

cell responds to different cues within the TME [94]. Acidic pH, lactic acid and

IL4 within the TME have all been found to upregulate Arg1 expression

within TAMs, promoting L-arginine degradation and resulting in reduced cytotoxic

T cell capacity and promotion of tumor growth [94, 95]. Compared to macrophages,

TAMs have been shown to possess significantly higher volumes of intracellular

lipids [96]. This is not surprising, as pro-tumor TAM phenotypes favor fatty acid

oxidation, which leads to induction of genes including Arg1 within TAMs

and reduces T cell proliferation through the degradation of arginine [94, 96, 97]. In addition, many TMEs possess high concentrations of arachidonic acid, that

produces metabolic by-products including prostaglandin E2, which has been

shown to generate an immunosuppressive phenotype within TAMs through the

upregulation of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), thus reducing T cell activation [58, 98]. Innate priming

may influence TAM metabolism within the TME. Treg cells help orchestrate an

immunosuppressive environment by supressing the production of IFN

Priming of macrophages prior to arrival at the TME may also contribute towards

the generation of anti-inflammatory phenotypes. Butyrate has been reported to

suppress innate training, inhibiting HDACs from promoting pro-inflammatory

cytokine production [50, 100]. Itaconate, a derivative from the TCA cycle, has

been reported to inhibit succinate dehydrogenase, inducing anti-inflammatory

response [101]. However, an itaconate catabolism intermediate, itaconyl-CoA was

shown to clears vitamin B12, limiting conversion of S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH)

to methionine, a metabolite reported to reduce production of pro-inflammatory

cytokines when allowed to accumulate [31, 59]. Moreover, TLR4 activation can

induce NAD+ dependent SIRT1 binding to the promoters of IL1

Epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming are the cornerstones of innate priming, enabling innate immune cells to maintain a trained or tolerized response to secondary stimuli. The mechanisms that govern these modifications may be induced prior to reaching the TME, influencing whether TAMs exhibit pro- or anti-tumor phenotypes in response to the tumor challenge. Summary of papers detailing innate priming epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming can be found in Table 1.

The application of innate priming could be of therapeutic benefit in a range of diseases. Support for the potential of this approach is provided by a study that utilised transcriptional signatures of monocytes that had undergone in-vitro priming to identify primed cells in different diseases. The transcriptional signature of primed monocytes was found within individuals with immune-mediated diseases such as COVID-19, ulcerative colitis and sepsis. This suggests that these primed cells may have a role in these diseases [28].

In the area of immunotherapy, the PD-1/PD-L1 axis has been the focus of

considerable clinical interest as blockade if this pathway can overcome

suppression of anti-tumor responses and results in long term survival of a

proportion of patients [61, 103]. However, as progression-free survival is only

20–30% after 5 years, it is clear that enhancement of this approach would be

required to extend its life extending benefits to a wider group of patients

[103]. Interestingly, transcription signatures associated with myeloid cell

activation in-vitro were found at higher levels in melanoma patients who

responded well to anti-PD1 immunotherapy and exhibited longer overall survival

[104]. Additionally, in a urethane-induced inflammation-driven lung

adenocarcinoma murine model, TNF

The relationship between innate priming and cancer therapy may be bidirectional. Prior research has demonstrated that the release of immunogenic agents from apoptotic tumor cells exposed to oncolytic adenoviruses were capable of polarizing TAMs towards pro-inflammatory phenotypes, promoting extended survival of mice with peritoneal metastasis when receiving anti-PD1 therapy [112]. Release of immunogenic agents during immunotherapy may prime innate cells resulting in the generation of anti-tumor phenotypes that enhance favorable therapy outcomes [37]. Influencing TAMs phenotype heavily shapes the immune landscape of tumors, particularly as TAMs have been identified to be one of the most abundant immune cells within the TME and have been correlated with therapy suppression [113, 114]. Through promoting TAM anti-tumor phenotypes with innate priming, this would induce an active tumor immune response, as TAMs are generating a pro-inflammatory environment, recruiting and activating T cells, and engaging in tumoricidal activity [115]. However, it is important to understand how innate priming exacerbates inflammation, as this may also promote development of immune-related adverse events in different circumstances [116, 117]. Taken together, these bodies of work suggest that manipulation of innate priming could be of clinical significance to immunotherapy and should become an active area of research.

BCG is already widely used in the oncology clinic as a standard adjuvant therapy

for superficial bladder cancer, and for intralesional treatment of inoperable

stage III in-transit melanoma [42, 43]. Patients with carcinoma in-situ

and high-risk papillary bladder tumors were reported to have experienced an

initial complete response rate of 70–75% and 55–65%, respectively, after

administration of the BCG vaccine. However, 40% of individuals relapsed during

treatment. Examination of the bladder wall revealed that the vaccine induced

gigantocellular and epithelioid granuloma formation, which comprised of

fibroblasts, lymphocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells and macrophages. Moreover,

the vaccine upregulated chemokine and cytokine production, induced a Th1 favored

response and increased infiltration of inflammatory and cytotoxic cells into the

bladder, including macrophages [43]. Additional in-vivo and

in-vitro studies have also shown that BCG vaccination is associated with

promoting recruitment of CD8+ T cells, increased production of cytokines in

macrophages including TNF, IL6, IL1

Endogenous compounds may also influence immunotherapy outcome in patient

cohorts, with a recent meta-analysis reporting that obese patients with advanced

lung cancer, melanoma and renal cell carcinoma had better survival outcomes

compared to non-obese patients [71]. In agreement, a recent retrospective

analysis of six independent patient cohorts consisting of 2046 patients with

metastatic melanoma assigned to various treatment strategies reported obesity was

associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma

receiving anti-PD1 immunotherapy, and that this association was particularly

strong in males [118]. Compounds that increase with obesity including acetate,

methylglyoxal, estradiol, butyrate and leptin have been found to modulate innate

immune cell function, including enhancing pro-inflammatory cytokine production

and cytotoxic capacity of macrophages [119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131]. Furthermore, drugs commonly used

for co-morbidities associated with obesity, such as metformin, have been reported

to downregulate CD206, upregulate the presentation of MHC-II, and increase

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF

There have been numerous studies whose results suggest potential links between innate priming, the PD1/PD-L1 axis and immunotherapy responses as summarised in Table 1. Whether the heightened immune response and improved response to immunotherapy described by a number of these in-vivo and retrospective patient studies reflect TAM priming by endogenous or exogenous compounds prior to arrival at the tumor site remains to be fully revealed [49, 71, 118]. However, together these studies provide the rationale for further investigation into the role of priming and its influence on TAM phenotype and function, and the consequent effects on tumor immune response.

While many studies have provided extensive insight into the capacity of innate priming and discussed how this immunological trait may be relevant to disease, common limitations are found within the literature. Many studies have a narrowed characterisation of innate priming through focusing on cytokine output and functional assays including reactive oxygen species generation. While informative of whether primary stimulants elicit alterations in response, detailed information on phenotypical changes remain elusive particularly as the pleiotropic nature of many cytokines are becoming apparent [133]. Moreover, while reactive oxygen species assays do provide information on functional changes, it does not provide information at the cellular level. This is limiting interpretation of the literature characterising innate priming as all ROS molecules are not the same and provide different effects and are involved in different molecular pathways [134]. Additionally, many of the models used within the literature are simplistic, comprising of in-vitro and ex-vivo culture within a 2D model consisting of single immune cell populations. This model does provide a repeatable environment to trial potential priming compounds, reducing potential result confounders. However, it does not replicate environmental complexity found within in-vivo models, as innate cells are exposed to numerous stimulants and communicate with one another to orchestrate an immune response [135]. This is particularly highlighted by studies that reported on attenuated innate priming when cells were exposed to several primary stimulants, representing more physiologically relevant exposure events [50, 51]. Furthermore, in-vivo models have utilised broad acting primary stimulants and focused on correlating effects with priming events. While providing information on potential consequence of priming in a complex environment, correlating outcomes does not direct to specific biological mechanisms. Research into innate priming is still in its infancy, but the necessary framework to investigate priming and its relevance in disease has been established. However, methodology limitations need to be addressed to further characterise the implications of innate priming.

In conclusion, exogenous and endogenous compounds have been shown to prime macrophages, resulting in epigenetic modification and metabolic changes that alter phenotype and function, and determine macrophage response to secondary stimulation. Investigations have demonstrated different primary inducers of innate priming and the implications of innate priming in various diseases, many of which are applicable to the TME and may offer potential therapeutic opportunity. In particular, administration of the BCG vaccine as therapy for bladder cancer and imprime PGG in conjunction with cetuximab to colorectal cancer patients has demonstrated the potential therapeutic benefit of priming-capable immunogenic agents. Together, these studies provide evidence that priming the innate immune system could be a potential strategy to improve the efficacy of cancer therapy [43, 63]. To explore the potential therapeutic value of innate priming, future work should further focus on characterizing primed macrophages response to secondary tumor stimulants at an in-vivo and ex-vivo level. With greater foundational work, this would provide justification to combine innate priming stimulants with existing immunotherapy regimes. Additionally, exploring patients’ immune profiles for signatures of innate priming and correlating with treatment outcome would provide confidence that priming could be an effective therapeutic strategy. In summary, innate priming adds to the complexity of the mechanisms that determine whether TAMs exhibit a pro- or anti-tumor phenotype and extends influence on TAMs beyond the immediate TME to potentially include systemic endogenous and/or exogenous factors. Investigating the influence of innate priming on TAM phenotype should become an active area of study, as it offers the potential to discover mechanisms to therapeutically manipulate TAM phenotype to improve current immunotherapy outcomes and create novel treatment regimes against cancer.

Ash1L, Lysine-specific Methyltransferase 2H; BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CD11b, Cluster of Differentiation 11b; CIITA, Class II Major Histocompatibility Complex Transactivator; CoA, Coenzyme A; CXCL1, Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand 1; DNMT1, DNA-Methyltransferase I; H3K27Ac, H3 Lysine 27 Acetylation; H3K4me3, Histone H3 Lysine 4 Trimethylation; HDACII, Histone Deacetylase II; HR, Hazard Ratio; IFN

BT, BH and MC involved in conceptualization, literature collection, and figure creation. GW and EP involved in conceptualization and literature collection. BT, BH and MC involved in drafting and reviewing work. GW and EP involved in reviewing work. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to members of Mackenzie Cancer Research Group and Haematology Research Group, University of Otago Christchurch.

This research was funded by the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust, the Canterbury Medical Research Foundation, the Maurice Wilkins Centre, the Professor Sandy Smith Memorial Trust and the Mackenzie Charitable Foundation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.