1 Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, The Sixth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, 100048 Beijing, China

2 School of Medicine, South China University of Technology, 510006 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a common critical illness. Supportive therapy is still the main strategy for ALI/ARDS. Macrophages are the predominant immune cells in the lungs and play a pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis, regulating metabolism, and facilitating tissue repair. During ALI/ARDS, these versatile cells undergo polarization into distinct subtypes with significant variations in transcriptional profiles, developmental trajectory, phenotype, and functionality. This review discusses developments in the analysis of alveolar macrophage subtypes in the study of ALI/ARDS, and the potential value of targeting new macrophage subtypes in the diagnosis, prognostic evaluation, and treatment of ALI/ARDS.

Keywords

- macrophage polarization

- subtype analysis

- ALI (acute lung injury)

- ARDS (acute respiratory distress)

Acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a clinical syndrome characterized by uncontrolled inflammation [1], with a high incidence and mortality [2]. ALI/ARDS can be caused by a variety of direct or indirect factors, including pneumonia, gastric content aspiration, sepsis, trauma, pancreatitis, and blood transfusion [3, 4]. Excessive and uncontrolled inflammatory responses lead to epithelial and endothelial barrier damage, alveolar-capillary membrane dysfunction, increased vascular permeability, and pulmonary edema and hypoxemia [5, 6, 7].

Macrophages are the core immune cell population involved in the regulation of

pulmonary inflammation. They release inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and

cytotoxic molecules such as interferon (IFN)-

Macrophages serve as the primary line of defense in innate immunity within the lungs and play a pivotal role in phagocytosis of pathogens and maintenance of immune homeostasis, which makes them a promising target for inhibiting progression of ALI/ARDS. Macrophages can be divided into different subtypes based on functional differences and expression of surface and intracellular markers. However, the results of current research on macrophage subtypes in ALI/ARDS are unclear. This review focuses on the methods of macrophage subtype analysis in ALI/ARDS, and the potential of targeting new macrophage subtypes in the diagnosis, prognostic evaluation, and treatment of ALI/ARDS.

Macrophages, the principal effector cells defending the lungs against foreign stimuli, have essential roles in the pathogenesis of lung inflammation, and demonstrate notable heterogeneity and phenotypic alterations [13]. Pulmonary macrophages consist of two distinct types of macrophages situated in different anatomical locations: alveolar macrophages (AM) and interstitial macrophages (IM) [14]. AM constitute approximately 95% of the leukocytes in pulmonary tissue and serve as the primary defense against microorganisms [15]. They typically show high levels of Mer receptor tyrosine kinase (MerTK), Fc gamma receptor I (CD64), epithelial growth factor (EGF)-like module-containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like 1 (F4/80), sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin F (Siglec F), major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II), and CD11c, while demonstrating low levels of CD11b [16, 17, 18]. IM are situated within the connective tissue surrounding the bronchiolar airways and typically exhibit expression of CD64, CD11b, CD11c, major histocompatibility complex II, and MerTK. They play a pivotal role in inflammation, tissue damage, and repair [16]. AM are classified into two types: tissue-resident alveolar macrophages (TR-AM) and monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages (Mo-AM). TR-AM originate from the embryo and undergo self-renewal and proliferation in a quiescent state [19]. When the body encounters infection or injury, bone marrow or circulating monocytes rapidly migrate to the alveolar space and differentiate into Mo-AM, which facilitate inflammatory responses and eradication of pathogens. The recruited monocytes typically exhibit high expression of CD11b and lymphocyte antigen 6 family member C1 (Ly6C), while showing low expression of MerTK, CD64, and F4/80. Upon differentiation into Mo-AMs, these cells demonstrate high expression of CD64, CD11c, F4/80, and MerTK, with low expression of Siglec F [16, 17, 18, 20]. During the initial phase of the inflammatory response, the number of Mo-AM substantially surges, then decreases, thus leaving a small population of Mo-AM that persist after infection and exhibit phenotypic and functional similarities to TR-AM [14]. AM secrete substantial quantities of inflammatory factors, which in turn initiate a cascade effect leading to the recruitment and modulation of other immune cells and inflammatory factors, and inducing an uncontrolled local inflammatory response in the lungs, in a crucial mechanism underlying acute lung injury [21, 22].

Macrophages exhibit remarkable plasticity and are commonly categorized into two

distinct subpopulations, characterized by the classical activation phenotype (M1)

and the alternative activation phenotype (M2), which maintain a balanced state

under physiological conditions but become imbalanced during disease

progression [23, 24]. M1 macrophages possess proinflammatory characteristics with

robust phagocytic and cytotoxic capabilities, and express proinflammatory

cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-12, IL-1

AM play a critical role in orchestrating the immune response to infections and

in contributing to the pathogenesis of ARDS. Their phenotypic characteristics and

functional responses show marked variability depending on the nature of the

infection (viral, Gram-negative bacterial, or Gram-positive bacterial) and the

inflammatory status of ARDS (hyper-inflammatory vs. hypo-inflammatory).

An experimental study in mice infected with influenza A virus has demonstrated

that influenza A virus (IAV) elicits significant upregulation of IL-6,

granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, IFN-

Two distinct subtypes of ARDS, characterized by differential expression levels

of biomarkers, have been delineated: hypo-inflammatory and hyper-inflammatory

[38]. The expression levels of surface markers associated with M1 macrophages,

including IL-6, IL-8, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and

IFN-

In recent years, several novel subtypes of macrophages have been identified, which secrete chemokines, metallothionein, IFN-inducible genes, and cholesterol-biosynthesis-related genes. These factors play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis and progression of ALI/ARDS. Investigation of the functional heterogeneity, activation status, and biological implications of distinct macrophage subtypes in driving inflammation, orchestrating tissue repair processes, regulating fibrosis progression, and facilitating resolution of inflammation is crucial for elucidating the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS.

Currently, alongside the two primary macrophage subpopulations of M1/M2, lung tissue has also been found to contain CD169+, secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1), and CD163+ macrophages involved in immune tolerance and antigen presentation [46, 47, 48]. Advances in experimental techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), high-content screening, proteomics, single-cell multiomics analysis, and fate mapping have identified novel alveolar macrophage subtypes. This discovery offers a fresh perspective for investigating the role of alveolar macrophage subtypes in preventing and treating ALI/ARDS (Table 1, Ref. [30, 34, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]).

| Species and sources of samples | Cell type | Biomarkers | References |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | Siglec1 (CD169+) macrophages | CD169+ | [49] |

| Single-cell suspensions of macrophages derived from murine and human lung tissues | Neuron and airway-associated (NAM) macrophages | CD169, CX3C chemokine receptor 1, EGF-like module-containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like 1 (F4/80), Mer receptor tyrosine kinase (MerTK), CD64, high expression bone morphogenetic protein 2, CD206 (human) | [50] |

| Patients in the advanced stage of COVID-19 | SPP1 alveolar macrophages | SPP1, Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, MMP9, CHI3L1, and Platelet-Activating Factor Acetyl hydrolase | [51, 52] |

| BALF from patients with ARDS | High expression of CD169 and PD-L1 in alveolar macrophages | CD169 and PD-L1 | [53] |

| BALF from patients with ARDS | AM expressing CD33, CD71, and CD163 | CD33, CD71, and CD163 | [53] |

| BALF from patients with COVID-19 | Metallothionein (MT1G+) macrophages | Expresses multiple thioproteins | [54] |

| BALF from patients with COVID-19 | IL-1 |

IL-1 |

[30] |

| BALF from healthy volunteers | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1 (MIP-1) AM | High expression of CCL3, CCL4, and C-X-C chemokine ligand (CXCL) 10 | [55] |

| BALF from patients with COVID-19 | Monocyte-derived AM (Mo-AM) | CCL3L1 and FCGR3B | [56] |

| BALF from patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure (AHRF) | CD163/LGMN AM | High expression of CD163, legumain (LGMN), heme oxygenase 1, and Cathepsin L, and low expression of CD71 | [57, 58] |

| BALF from healthy patients receiving LPS nebulization | CD14CD16++-monocyte like cells | CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL10, and CXCL11 | [59] |

| BALF from healthy volunteers | Resident AM defined by pro-inflammatory and metallothionein enzymes | High expression of metal transport protein (SLC30A1) | [34] |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; AM, alveolar macrophages; MMP9, Matrix Metallopeptidase 9; CHI3L1, Chitinase 3 Like 1; PLA2G7, Phospholipase A2 Group VII; IL, interleukin, CCL, chemokine CC ligand; EGF, epithelial growth factor; CX3C chemokine receptor 1, C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; FCGR3B, Fc gamma receptor IIIb.

Pulmonary fibrosis represents the failure of end-stage repair in ALI/ARDS. Research on COVID-19-associated fibrotic changes in this stage has identified a novel pro-fibrotic macrophage subset of AM with elevated expression of SPP1, lipoprotein lipase, and chitinase 1. These molecules contribute to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis and therefore may be potential therapeutic targets for the disease [60]. Furthermore, in vivo study using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated ALI mice have demonstrated a significant increase in both the number and proportion of AM expressing high levels of Ly6C and CD38 in the alveoli on day 3 after LPS stimulation. Additionally, a substantial elevation was observed in the levels of iNOS, as well as the chemokines CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXC motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)2, CXCL3, CXCL9, and CXCL10. After mesenchymal stem cell immunotherapy intervention, a notable decrease in the Ly6C+CD38+ macrophage population has been reported. Analysis of phenotypic and functional alterations during disease progression among macrophages has provided new insights into targeting ALI/ARDS through modulation of macrophage responses [61].

Many studies have demonstrated the diverse biological effects of macrophages in regulating the inflammatory response and repair processes in ALI/ARDS, with different roles in different states, indicating their pivotal role in mediating inflammation and repair [8, 62, 63]. Novel macrophage subtypes and differentially expressed genes have been identified by bioinformatics analysis of samples from healthy control and ARDS model groups, enabling exploration of the pathogenic roles of these genes and macrophage subtypes in ARDS. This knowledge could contribute to improved diagnosis, prognostic assessment, and development of novel therapeutic strategies for ARDS.

Various methods are used to investigate the functions and phenotypic analysis of

macrophages (Table 2, Ref. [16, 53, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80]), primarily

involving assessment of cytokine secretion and characterization of different

phenotypes. In vitro experiments have used diverse features to

characterize the phenotype of macrophages. For instance, M1 and M2 macrophages

can be distinguished based on distinct patterns of surface receptor expression,

secretion profiles, and functional characteristics [15, 81, 82]. LPS and

IFN-

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| ELISA | The method exhibits high sensitivity and specificity, enabling the detection and quantification of a given marker. | Poor reproducibility; many interfering factors | [74, 75] |

| RT-qPCR | The data are reliable. Absolute quantification of DNA or RNA. | Long times required to design probes or primers | [64, 76, 77] |

| Immunofluorescence | This highly specific and sensitive method enables direct visualization of the nucleus and simultaneous multi-color staining. | Substantial observer subjectivity | [78, 79] |

| Flow cytometry and immunomagnetic cell sorting | This method detects immune cell-related phenotypic markers; cell viability detection; cell function. | High technology costs | [53, 65] |

| HCS | This method can simultaneously detect multiple candidate compounds and reveal the disease mechanisms. | Experimental conditions requiring high standards | [66, 67] |

| Proteomics | This method has a high sequence coverage rate for the analysis of protein profiling. | High technology costs | [68, 69] |

| scRNA-seq | This method has high resolution for construction of cell atlases, refinement of cell subpopulations, identification and analysis of rare cell types. | High technology costs | [70, 71] |

| CITE-seq | This multi-omics analysis can assess the heterogeneity of immune cells. | High sequencing costs; errors; limited protein markers | [72, 80] |

| Spatial transcriptomics | This method integrates multi-dimensional data and invest alterations in gene expression across various tissues. | Data processing complexity | [16, 73] |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR; HCS, high-content screening; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; CITE-seq, sequencing.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) are commonly used for assessing

the polarization phenotype of macrophages, and measuring mRNA and protein levels

of inflammatory factors secreted by cells during phenotypic changes [64, 85, 86].

ELISA offers the advantage of convenience and speed in detecting cell proteins,

while RT-qPCR exhibits higher sensitivity and requires less cellular volume[85] .

Similar to ELISA, Luminex multifactor detection enables simultaneous measurement

of multiple cytokines with high sensitivity, parallel detection, and rapidity

[87, 88]. ELISA and RT-qPCR are frequently utilized to determine the levels of

TNF-

Immunofluorescence is an important technique that enables the visualization of diverse antigens in tissues or cell types by utilizing fluorescently labeled specific antibodies, thereby achieving exceptional sensitivity and signal amplification [91, 92]. Immunofluorescence has been used extensively in the analysis of macrophage polarization. F4/80 is commonly utilized as a marker for mouse macrophages; CD80, CD86, CD163, and iNOS are used to label M1 macrophages; and CD206, CD209, and IL-10 are used to identify M2 macrophages [93].

Morrell et al. [53] used flow cytometry to discriminate between different subtypes of macrophages in BALF from patients with ARDS, and characterized immune cells in human BALF and lung tissue to distinguish surface marker profiles that differentiate alveolar from interstitial macrophages. Expression of CD169 differed significantly between human alveolar and interstitial macrophages: AM had high expression of markers such as CD169, CD71, CD80, CD86, and CD206; whereas CD169 macrophages were specifically confined to the interstitial space [65].

AM play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS. Current methods for classifying macrophages primarily rely on surface marker expression and functional alterations following exogenous stimulation [83]. However, the heterogeneity of AM makes it difficult to use traditional approaches to detect the intricate internal expression changes that occur during tissue injury. Recent advances in quantitative techniques have gradually unraveled the types, states, and heterogeneity of lung macrophages.

High-content screening (HCS) is a microscopy-based approach that enables

high-throughput analysis of complex cellular phenotypes within tissue sections,

while preserving cellular structure and functional integrity [66]. In comparison

to conventional techniques, HCS offers improved assessment of macrophage

phenotypes in diverse cell models, facilitating generation of comprehensive

cellular response profiles and enabling drug discovery for disease treatment

[93]. Hoffman et al. [67] employed ex vivo high-content image

analysis to investigate the responses of AM to various safety medicines upon

inhalation. Nizami et al. [94] have identified several small molecule

inhibitors targeting heat shock protein 90, Janus kinase (JAK), and I

Significant advances in quantitative techniques have made it possible to identify thousands of proteins in a single sample. The continuous improvement of high-throughput proteomics and deep proteomic coverage further enhances our ability to validate the functional relevance of sequence variations or new transcripts identified in RNA-seq data [68]. Proteomics has emerged as a powerful tool for the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of diseases, and several studies have used proteomics to identify potential therapeutic targets [69, 95]. Proteomics is particularly advantageous for investigating the polarization of AM due to their high heterogeneity and the dynamic changes in cell damage during ALI [95]. Proteomic analysis characterizes the surface markers of fully polarized macrophages and elucidates the temporal alterations in cell signaling and metabolism throughout the macrophage polarization process [96]. These findings provide a solid foundation for targeted macrophage therapy [97].

Currently, the investigation of macrophages using the aforementioned techniques primarily relies on cell-surface-specific markers and is unable to analyze unidentified cell types. scRNA-seq, however, is not constrained by previously defined markers and enables the assessment of transcriptional similarity and diversity within cell populations [98]. Gene expression profiles can be utilized to identify distinct subpopulations, discover unique surface markers, and trace lineages, thereby offering the potential for identifying novel cell subtypes [99, 100].

In immunology research, single-cell genomics analysis aids in clustering immune cells and observing their dynamic classification into subtypes. It even allows for inference of gene regulatory networks that underlie functional heterogeneity and cell-type specificity beyond what can be achieved with current immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry methods [70]. Based on RNA-seq analysis of human and mouse lung macrophages, two distinct subpopulations were identified: CD169+CD11C- neuronal macrophages and CD169+CD11C+ airway-associated macrophages [50]. These subsets differ from other macrophage subpopulations but play crucial roles in immunoregulation and homeostasis maintenance. In organs characterized by a conserved core gene profile, tissue stratification was based on common core gene expression (phosphatidylserine receptor T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 4 (TIMD4), lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE1), folate receptor beta (FOLR2), and chemokine receptor C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2)). Dick et al. [71] have further classified three macrophage subpopulations: TLF+ (expressing TIMD4 and/or LYVE1 and/or FOLR2) macrophages, CCR2+ (TIMD4-LYVE1-FOLR2-) macrophages and MHC-IIhi macrophages (TIMD4-LYVE1-FOLR2-CCR2-). scRNA-seq has now provided a new starting point for identifying disease biomarkers, new cellular subsets, therapeutic targets, and diagnostic approaches [101].

While scRNA-seq enables the identification of novel cell subtypes, distinguishing functionally distinct immune cells with similar transcriptomic profiles, such as M2 macrophages across different subtypes, remains challenging. Cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) is an advanced technique that allows for simultaneous detection of multiomics data within individual cells [102], encompassing single-cell genomics, epigenetics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [103, 104]. Additionally, it facilitates quantification of cell surface protein and transcriptomic data during single-cell sequencing. By jointly analyzing proteomic and transcriptomic data sets, the gene expression profile of macrophages can be determined. Through comparative analysis of proteomics and transcriptomics in 12 distinct mouse tissue macrophages, specific molecules including Mucin 1, macrophage receptor with collagenous structure, programmed cell death ligand 1, and C-type lectin domain family 5 member A were identified to differentiate resident macrophages in tissues from lung and liver macrophages [105]. CITE-seq revealed a panel of simple cell surface protein markers (CD14, CD44, CD48, CD71, CD86, CD123 and CD163) that offer potential avenues for future research focused on identifying and purifying alveolar monocyte/macrophage subpopulations from large clinical cohorts [57].

CITE-seq enables the identification of distinct alveolar monocyte/macrophage subpopulations in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) and facilitates the discovery of cell surface protein markers that can distinguish these subpopulations. High-throughput flow cytometry methods have been used to validate a subset of these subpopulations in an independent clinical cohort, thus revealing a significant association between CD163/legumain (LGMN) macrophages and mortality. Analysis of paired blood and alveolar samples has demonstrated that ficolin-M alveolar monocytes, inflammatory alveolar monocytes, and IFN-related macrophages exhibit transcriptomic similarities with blood monocytes [57, 58]. IL-18 has been identified as a key molecule for discriminating tissue-resident from recruited macrophages [105]. By using epigenetic sequencing and RNA-seq multiomics analysis, we identified IFN regulatory factor 1 and early growth response factor 1 as the predominant DNA-binding transcription factors expressed during M1 and M2 macrophage polarization [106]. Guilliams et al. [72] have used single-cell CITE-seq, spatial transcriptomics, and spatial proteomics datasets to establish a comprehensive spatial proteogenomic single-cell atlas of the liver while validating various surface markers for distinguishing and localizing liver macrophages. The integration of multiomics techniques is increasingly being used to assess macrophage heterogeneity while providing novel insights into diagnostic and prognostic assessment of ALI/ARDS.

Polarized macrophages are critical components of the innate immune response and are essential for the upkeep of lung environmental homeostasis. Nevertheless, because of the overlap in cell surface markers among tissue-resident alveolar and interstitial cells and elicited macrophages, their differentiation via conventional methodologies presents a considerable challenge. Spatial transcriptomics has substantially contributed to the delineation of macrophage heterogeneity within the lung microenvironment. By the analysis of clinical specimens derived from 646 people with COVID-19, this technique has been instrumental in differentiating ARDS and the transcriptomic alterations induced by COVID-19 from those caused by seasonal influenza viruses and other etiologies. This advancement has facilitated deeper understanding of the molecular underpinnings of COVID-19 [73]. Aegerter et al. [16] have used RNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics to proficiently delineate and differentiate human from mouse lung macrophage subsets, thereby shedding light on the maturation and functional aspects of these cells.

The analysis of macrophage subtype technology plays an essential role in the

diagnosis, treatment, and prognostication of ALI/ARDS. scRNA-seq and flow

cytometry can be applied to assess the proportion and activation status of

distinct macrophage subpopulations during the early phases of ALI/ARDS, thereby

facilitating timely diagnosis of these conditions [73]. The surface markers and

secreted factors, including IL-1

The duration, degree, and proportion of macrophage polarization, as well as the

subpopulation of macrophages, play crucial roles in determining the severity and

prognosis of ALI/ARDS [109]. During the exudative phase of ALI/ARDS, M1

macrophages are predominantly activated by pathogens, leading to elevated levels

of IL-1

M2 is the predominant macrophage subtype involved in the resolution phase of ALI/ARDS, and plays a pivotal role in regulating excessive inflammatory responses and promoting anti-inflammatory and wound healing processes. M2a and M2c macrophages possess the ability to modulate Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway activation through IL-10 in LPS-induced ALI, thereby mitigating inflammatory infiltration and preserving lung function in murine models [114].

Many studies have demonstrated that the fibrotic phase of ALI/ARDS primarily

correlates with M2 macrophages expressing diverse cytokines, including CD206 and

chemokine CCL18. The levels of cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth

factor-

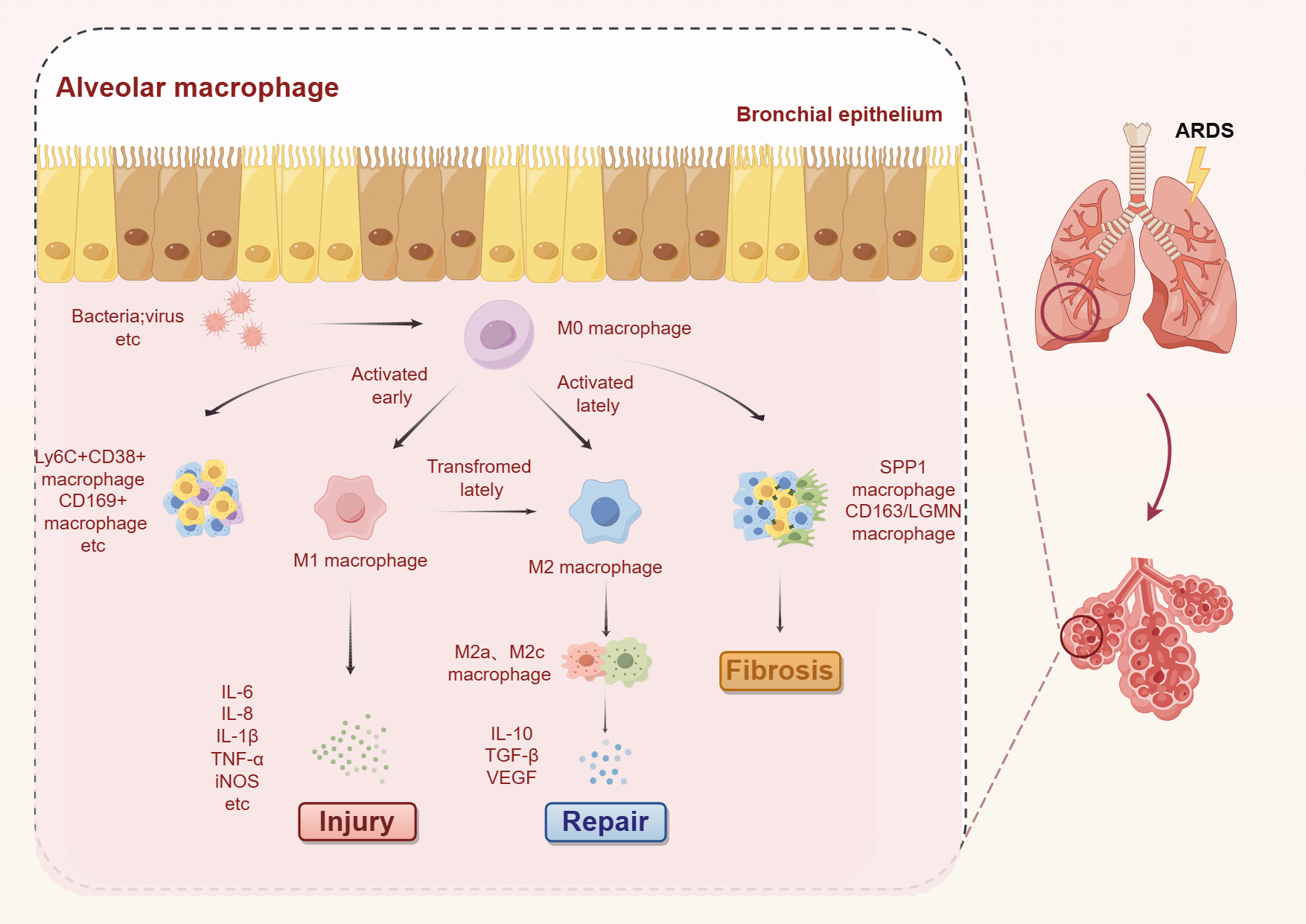

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Dynamic changes in macrophages during the inflammatory,

recovery, and fibrotic phases of ALI/ARDS. Upon viral infection, AM recognize

pathogen-associated molecular patterns and undergo polarization into M1

phenotype, leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to

tissue damage. Novel macrophage subsets, such as Ly6C+CD38+ and CD169+

macrophages, also participate in the response to tissue injury. In later stages

of damage, AM transition from the M1 to the M2 phenotype and secrete

anti-inflammatory cytokines that facilitate tissue repair. Notably,

SPP1-expressing macrophages and CD163/LGMN-positive macrophages significantly

increase during the fibrotic phase of ALI/ARDS and play a pivotal role. ALI, acute lung injury; M0, nonactivated phenotype; M1,

classical activation phenotype; M2, alternative activation phenotype; TNF, tumor

necrosis factor; TGF, transforming growth factor-

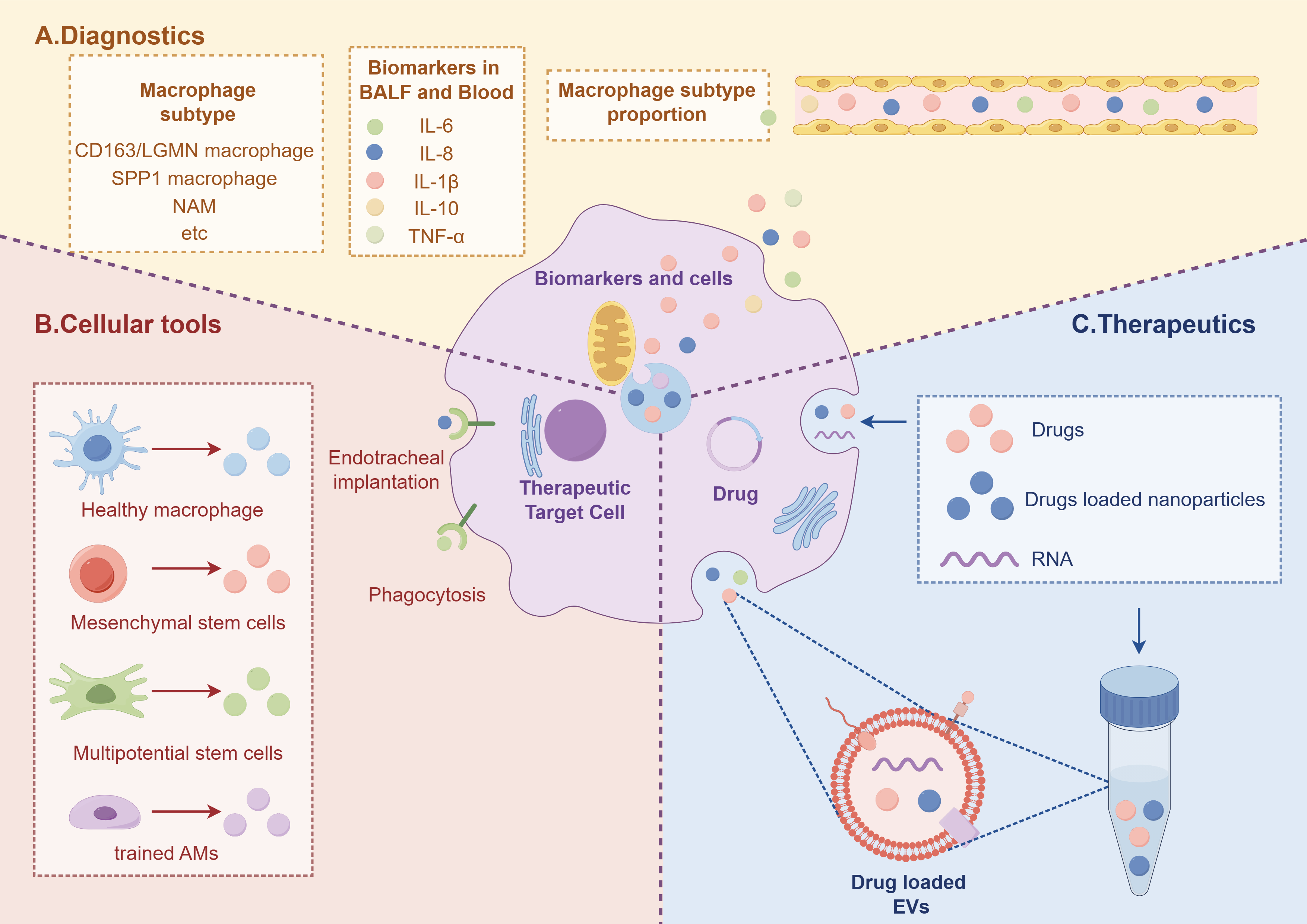

By investigating novel subtypes of macrophages and identifying appropriate targets, it may be feasible to slow disease progression and enhance patient survival rates. Tailored therapeutic strategies can be developed for distinct macrophage subtypes. Numerous targeted therapeutic approaches for macrophages have been developed to modulate macrophages from a proinflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state, enhance the anti-inflammatory phenotype of macrophages, suppress the proinflammatory phenotype, and target signaling pathways associated with inflammation. These strategies encompass pharmaceutical agents, nanoparticles, small interfering RNA, and cell-based therapy specifically designed for targeting macrophages (Fig. 2) [117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Diagram depicting diagnosis and treatment of ALI. (A) Identification of novel subtypes of macrophages in blood and BALF, based on their specific surface markers and proportions, holds promise for prognostic assessment of disease outcome. (B) Various cellular tools can be reprogrammed into macrophages. (C) Therapeutic strategies targeting inhibition of macrophage proinflammatory activity and promotion of anti-inflammatory responses involve the use of drugs, nanoparticles, and exosomes for ALI management (Fig. 2). EVs, extracellular vesicles. The figure was created by Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com).

Despite extensive research on ALI/ARDS, the current optimal clinical approach

for ALI/ARDS remains protective mechanical ventilation; however, the mortality

rate has not declined. Investigating alternative molecular mechanisms beyond

supportive therapy is imperative to decrease mortality. For instance, inhibiting

the amplification of signaling pathways may provide an efficacious strategy for

managing ALI [123, 124]. If emodin reduces the production of exosomes from

isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 pancreatic acinar cells, it weakens the polarization

of macrophages towards M1 type macrophages by inhibiting the peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors

Nanocarriers hold substantial promise for overcoming the limitations of

conventional drug therapy for ALI/ARDS by facilitating targeted delivery to

specific cells, precise drug release, and improved pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics [129, 130]. Su et al. [131] have prepared dexamethasone

(DXM)/mannose co-modified branched polyethyleneimine (DXM-PEI-mannose, DPM)

prodrug nanoparticles that effectively target the mannose receptor on AM in the

lungs, thus offering a potential treatment for ALI/ARDS. DXM-PEI exhibits

excellent serum stability and biocompatibility. Furthermore, DXM-PEI

significantly decreases the infiltration of inflammatory cells and TNF-

Gene silencing is a promising paradigm for specifically and effectively

inhibiting these mechanisms, thereby creating new treatment opportunities for

ALI/ARDS. The modulation of pro-inflammatory mediators at the mRNA level in

ALI/ARDS can be achieved through short interfering RNA (siRNA), thereby

demonstrating the potential of gene silencing as an effective molecular therapy

for treating lung injury by targeting siRNA to lung tissue. Intrabronchial

administration of siRNA significantly attenuates the production of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in the lungs by suppressing NF-

Recent studies have proposed that targeted cell-based therapy specifically aimed at macrophages could be a promising therapeutic strategy for ALI/ARDS [139, 140, 141]. This can be achieved by introducing multipotent/hematopoietic stem cells into the trachea via intubation, followed by in vivo induction of their differentiation into macrophages. These differentiated macrophages can then mitigate the progression of ALI/ARDS through neutrophil phagocytosis and promotion of lung tissue repair. A multi-center study in patients with COVID-19 has demonstrated that transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells significantly decreases the mortality rate in patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by epidemic influenza A (H7N9) infection [142, 143]. Additionally, in vitro induction of an anti-inflammatory and repair-promoting state in macrophages, followed by injection of healthy macrophages into the lungs, can rectify immune dysregulation and suppress cytokine storms, thereby enhancing the survival rate of patients with ALI/ARDS [144]. Gorki et al. [121] showed that primary AM were successfully transplanted into mice with alveolar macrophage deficiency. This transplantation effectively decreased the accumulation of surfactants and proteins in the lungs of mice lacking pulmonary AM, thus demonstrating their ability to perform crucial macrophage functions when implanted in vivo. Another study has indicated that repeated stimulation of alveolar macrophage subpopulations with LPS or Pseudomonas aeruginosa expressing high levels of MERTK and macrophage receptor with collagenous structure, and low levels of CD163 and F4/80+, accelerates the resolution of lung injury and decreases mortality in mice with Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury after transfer of these cells into the lungs [145]. Furthermore, Aegerter et al. [146] have demonstrated that mice that have recovered from COVID-19 for 1 month are protected against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, a finding potentially attributed to the presence of IL-6-high AM derived from monocytes in the lungs. A separate study has revealed that the subtype of pulmonary macrophages in mice experiencing recurrent pneumococcal infections differs from that of resident alveolar macrophages, and that a novel subtype suppresses bacterial proliferation during repeated infection [147] .

Consequently, maintaining a balanced inflammatory state within macrophages and targeting them specifically may represent a pivotal therapeutic approach for ALI/ARDS.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the analysis of macrophage subtypes in

ALI/ARDS through the utilization of cell surface markers and gene expression

profiling has potential for prognostic assessment of disease progression. In a

single-center study, multivariate analysis of patients with ALI/ARDS demonstrated

direct correlation between the level of IL-8 in BALF and patient mortality [107, 108, 148].

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1

Distinct cell subpopulations and cytokines have been identified in ALI/ARDS

patients with a favorable prognosis. One study reported elevated levels of

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor in BALF among patients with

improved prognosis for ARDS [150]. A single-center trial observed a reduction to

baseline levels in the number and proportion of IL-1

Macrophages are the most abundant immune cells in alveoli and play crucial roles in regulating inflammation and promoting tissue repair during ALI/ARDS [10]. Macrophages can differentiate into various subtypes due to their high heterogeneity in different environments [151]. Advanced experimental techniques such as scRNA-seq, proteomics analysis, single-cell multiomics analysis, fate maps, and bioinformatics analysis have gradually revealed new macrophage subtypes with distinct secreted inflammatory factors, surface-specific markers, and epigenetic profiles.

Conventional experimental techniques continue to be widely used for evaluation of diverse functions and phenotypes of macrophages. Approaches such as scRNA-seq, proteomics analysis, and single-cell multiomics analysis are indispensable in constructing immune cell atlases, refining cellular subpopulations, and identifying rare cell types. Despite recent advances, these methods still have limitations, including high technical costs and limited coverage at the single-cell level, necessitating further enhancements and exploration.

ALI/ARDS has long been recognized as a highly heterogeneous clinical syndrome due to the diverse array of pathogenic factors, clinical symptoms, onset time, and disease course [3]. In healthy or diseased states, different subsets of macrophages have specific locations and functions. In the early stage of ALI/ARDS, M1 macrophages predominate in the alveoli, and play a proinflammatory and pathogen-clearing role. In the late stage of the disease, M2 macrophages secrete large amounts of inflammatory factors to promote tissue remodeling and repair [25]. In addition, during the progression of ALI/ARDS, the numbers and proportions of new subpopulations of CD163/LGMN AM, Ly6C+CD38+ AM, and SPP1 AM are upregulated. These cells have different numbers and proportions in alveoli depending on patient age, severity of ARDS, ARDS stage, and treatment during progression, and to some extent, they can directly predict the mortality rate. Therefore, more precise phenotypic analysis is needed to study the new subpopulations of macrophages and their dynamic changes in the disease process, and to explore the relationship between these dynamic changes and clinical outcomes.

The exploration of novel subtypes of macrophages is anticipated to advance our understanding of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of ALI/ARDS. However, the clinical significance of these newly identified macrophage phenotypes in diagnosing and assessing prognosis for ARDS remains undetermined, necessitating further investigation into the specific alterations occurring in macrophages during inflammatory and reparative processes. This will provide valuable insights for selecting diagnostic markers and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

Currently, targeted macrophage or macrophage-based therapies are still in the early stages; however, they have demonstrated promising outcomes in experimental models of ALI/ARDS [117, 119]. For instance, this includes the conversion of mesenchymal and hematopoietic stem cells into macrophages, followed by their administration via tracheal injection in mice [139]. Additionally, there is potential for drugs, nanoparticles, and exosomes to modulate macrophages from a proinflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state [122, 125, 126]. Consequently, further investigation into strategies for targeted macrophage therapy is imperative to establish a solid foundation for clinical translation.

ALI, acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; AHRF, acute hypoxemic respiratory failure; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; CCL, chemokine CC ligand; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; HCS, high-content screening; JAK, Janus kinase; TIMD4, phosphatidylserine receptor T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 4; LYVE1, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1; FOLR2, folate receptor beta; CCR2, chemokine receptor C-C motif chemokine receptor 2; TGF-

JT and JS contributed equally to this work. JT and JS recommended a structure for the review and wrote the initial draft. ZH and XC revised the manuscript and prepared figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (NO.7232169).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.