1 Department of Biology, Tyumen Medical University, 625023 Tyumen, Russia

2 Laboratory for Chronobiology and Chronomedicine, Research Institute of Biomedicine and Biomedical Technologies, Tyumen Medical University, 625023 Tyumen, Russia

3 Tyumen Cardiology Research Center, Tomsk National Research Medical Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, 634009 Tomsk, Russia

4 Helmholtz Research Institute of Eye Diseases, 105062 Moscow, Russia

5 Institute of Biology/Zoology, Martin Luther University, 06108 Halle-Wittenberg, Germany

6 Yakutsk Republican Ophthalmological Clinical Hospital, 677005 Yakutsk, Russia

7 Department of Ophthalmolgy, Pavlov First State Medical University of St Petersburg, 197022 St Petersburg, Russia

8 Halberg Chronobiology Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA

Abstract

This review explores the intricate relationship between glaucoma and circadian rhythm disturbances. As a principal organ for photic signal reception and transduction, the eye plays a pivotal role in coordinating the body's circadian rhythms through specialized retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), particularly intrinsically photosensitive RGCs (ipRGCs). These cells are critical in transmitting light signals to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the central circadian clock that synchronizes physiological processes to the 24-hour light-dark cycle. The review delves into the central circadian body clock, highlighting the importance of the retino-hypothalamic tract in conveying light information from the eyes to the SCN. It underscores the role of melanopsin in ipRGCs in absorbing light and initiating biochemical reactions that culminate in the synchronization of the SCN's firing patterns with the external environment. Furthermore, the review discusses local circadian rhythms within the eye, such as those affecting photoreceptor sensitivity, corneal thickness, and intraocular fluid outflow. It emphasizes the potential of optical coherence tomography (OCT) in studying structural losses of RGCs in glaucoma and the associated circadian rhythm disruption. Glaucomatous retinal damage is identified as a cause of circadian disruption, with mechanisms including oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and direct damage to RGCs. The consequences of such disruption are complex, affecting systemic and local circadian rhythms, sleep patterns, mood, and metabolism. Countermeasures, with implications for glaucoma management, are proposed that focus on strategies to improve circadian health through balanced melatonin timing, daylight exposure, and potential chronotherapeutic approaches. The review calls for further research to elucidate the mechanisms linking glaucoma and circadian disruption and to develop effective interventions to address this critical aspect of the disease.

Keywords

- glaucoma

- light

- retinal ganglion cells

- circadian disruption

- melatonin

- sleep

- mood

- metabolism

- light therapy

Glaucoma is a widespread neurodegenerative ocular condition and a significant contributor to global blindness [1]. In 2020, an estimated 3.6 million individuals experienced vision impairment due to glaucoma, with approximately 11% of all cases of blindness in adults over the age of 50 attributed to this condition [2]. The prevalence of glaucoma in Europe was reported to be 2.93% among individuals aged 40 to 80 years, with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) affecting most of them (2.51% of this demographic) [1, 2]. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can aid in identifying structural changes in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) that are indicative of glaucoma [2], including daily changes [3], and their associations with early stages of circadian rhythm disturbances [4, 5, 6, 7]. Compromised transmission of photic information to the brain results in diminished light signaling and a weakened amplitude of its circadian variation. Loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), including melanopsin-containing intrinsically photosensitive RGCs (ipRGCs) that are affected in advanced glaucoma [8, 9], can further impede light perception. It causes profound disruptions to the circadian rhythms [4, 5, 7], sleep patterns [4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15], and mood [16]. A major reason relates to the eye’s diminished ability to receive and transmit photic signals crucial for synchronizing the body’s internal clock with the environmental light-dark cycle. The multifaceted effects of circadian disruption in glaucoma extend beyond ocular functions. They include the misalignment between systemic and local rhythms [6] and metabolic dysregulation [17]. Effective management strategies for glaucoma should give precedence to interventions that foster circadian health [5]. Additionally, the exploration of chronotherapeutic methods [18] is crucial for alleviating the negative effect of glaucoma on the circadian system and breaking the detrimental cycle of circadian disruption exacerbating disease progression.

The eye, an organ of remarkable specialization, transforms photic stimuli into neural impulses via a sophisticated process that encompasses light absorption, photoisomerization, and subsequent electrical signaling [19, 20, 21]. These electrical signals are then transmitted to the brain through the optic nerve allowing photic signal transduction [21]. The process of photic signal reception and transduction in the eye begins with light entering the cornea and undergoing refraction. The refracted light then passes through the pupil and lens, which further focus it onto the retina. The retina contains visual photoreceptor cells: rods and cones; rods are more sensitive to low light and are responsible for night vision and peripheral vision, while cones are responsible for color vision and high-resolution central vision. Light absorption starts when light strikes the photoreceptor cells and is absorbed by visual pigments. These pigments consist of two proteins – opsin and a chromophore molecule (11-cis-retinal) [22]. The absorption of light causes the chromophore molecule to undergo a shape change called photoisomerization. This change triggers a cascade of biochemical reactions within the photoreceptor cell. The photoisomerization process activates a protein called transducin, which then activates the enzyme phosphodiesterase (PDE). PDE breaks down cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), a molecule that keeps the photoreceptor cells open. The decrease in cGMP causes the photoreceptor cells to hyperpolarize, meaning their electrical potential becomes more negative. This hyperpolarization reduces the release of neurotransmitters from the photoreceptor cells. The hyperpolarization of the photoreceptor cells sends a signal to bipolar cells and then to ganglion cells, which are the output neurons of the retina. Ganglion cells transmit the processed visual information to the optic nerve and ultimately to the brain.

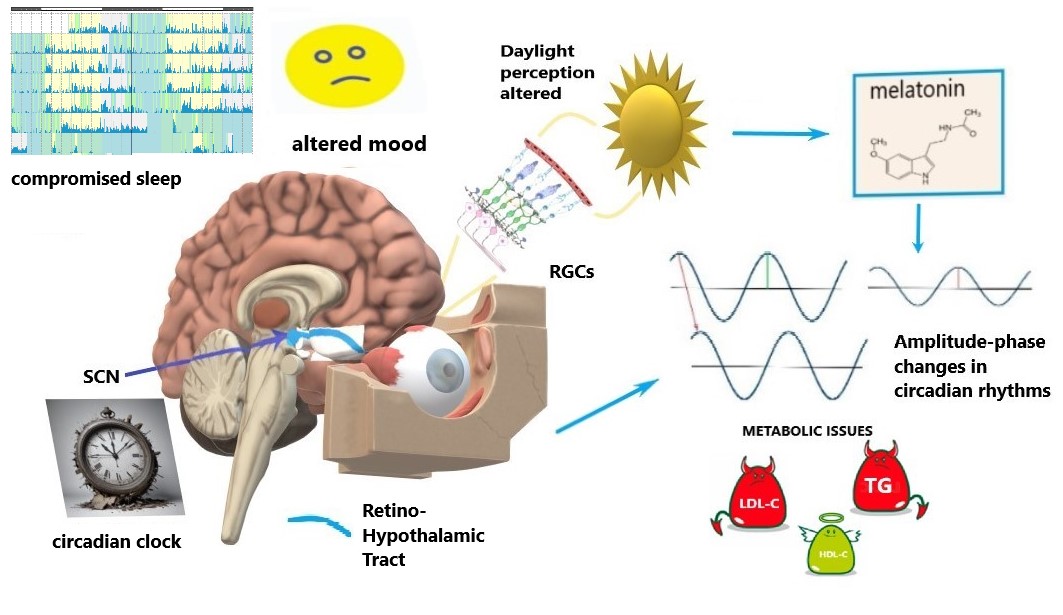

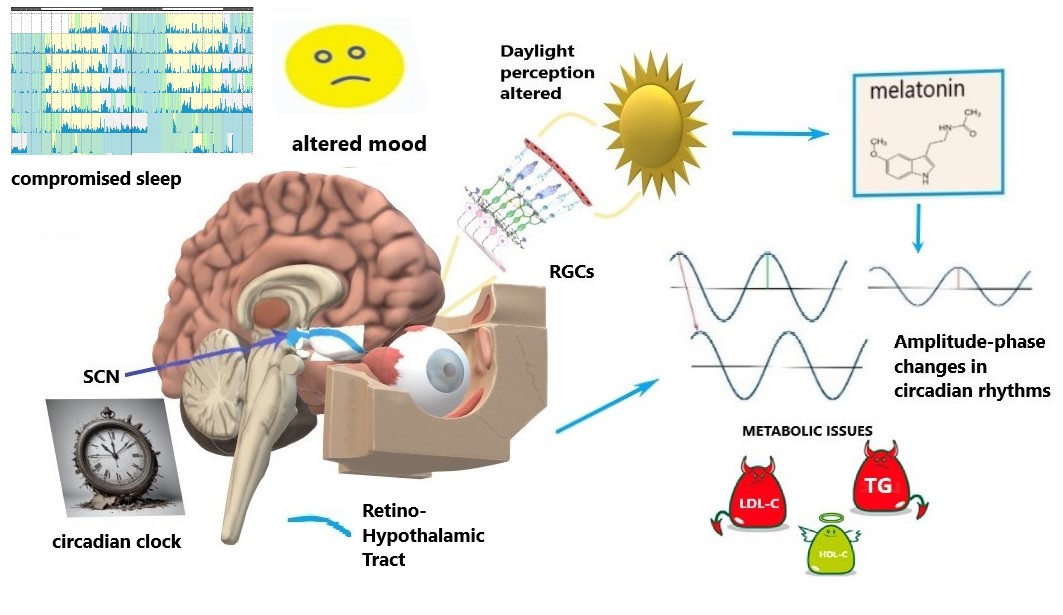

Specific intrinsically-photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells (ipRGCs) are a specialized group of RGCs that contain the light-sensitive pigment melanopsin, enabling them to directly detect light without the need for rods or cones [23, 24]. ipRGCs play a crucial role in regulating the body’s circadian rhythm, which synchronizes physiological processes to the 24-hour light-dark cycle [24]. They receive light input and transmit signals to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the brain region that coordinates the biological clock and has an effect on sleep [25]. ipRGCs play a role in light-dependent functions beyond circadian rhythms, such as prefrontal cortex activity controlling emotions, social activity and cognitive functions [26], and, also, mood [27] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of circadian disruption in glaucoma. Light signaling from the retina to the circadian clock via the retino-hypothalamic tract is compromised by the progressive loss and dysfunction of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), including intrinsically-photosensitive RGCs (ipRGGs) in advanced glaucoma stages. Altered light perception affects the circadian clock (suprachiasmatic nucleus, SCN), sleep, and mood. Such alterations modify melatonin patterns; they are also coupled with amplitude-phase changes in circadian rhythms that involve metabolic issues, i.e., circadian syndrome manifestations: altered lipids profiles and their 24-hour dynamics. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The figure was created by Microsoft Paint 3D V 6.2203.1037.0 available free at https://microsoft-paint-3d.en.softonic.com/.

The Retino-Hypothalamic Tract (RHT) contains a bundle of axons from ipRGCs that project directly to the SCN, which is the central clock (a self-sustained oscillator) [28]. The projection of light information from the eyes to the SCN via the RHT is essential for synchronizing circadian rhythms to the external light-dark cycle and coordinating various physiological and behavioral processes. Light information is projected to the SCN via ipRGCs, particularly though not exclusively in the short-wavelength blue light range [29]. The absorption of light triggers a cascade of biochemical reactions within ipRGCs, leading to the generation of electrical signals. The electrical signals are transmitted along the axons of ipRGCs, which form the RHT, and terminate in the SCN. The neurotransmitter glutamate is released, which activates glutamate receptors on SCN neurons. SCN synchronization relies on glutamate signaling from the RHT to synchronize the firing patterns of SCN neurons, aligning their circadian rhythms to the light-dark cycle [30, 31]. Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) play a key role in regulating circadian rhythms in humans by transmitting light information to the brain via the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), particularly to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the central circadian clock. ipRGCs primarily release glutamate as a neurotransmitter to activate the SCN. However, in addition to glutamate, these cells co-release pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) [32]. PACAP enhances the effects of glutamate in the SCN, modulating the circadian phase-shifting response to light. It acts through pituitary adenylate cyclase (PAC1) receptors, helping regulate the strength and timing of light-induced changes in circadian rhythms. PACAP’s role is particularly important in fine-tuning the sensitivity of the SCN to light stimuli, thus contributing to the precision of circadian entrainment to the day-night cycle. This combination of glutamate and PACAP ensures robust communication between the retina and the SCN, helping to maintain circadian synchronization. Light exposure resets the SCN clock, ensuring that our biological rhythms (e.g., sleep-wake cycle, hormonal secretion) are aligned with the external environment. Resetting the clock is primarily induced by light exposure at night, and for humans, light during the day typically affects the clock in the morning. According to Phase-Response Curves to light, the morning and evening are the most sensitive periods for resetting the circadian clock and drive its phase. Light information from the SCN also coordinates the pupillary light reflex, which adjusts the size of the pupils in response to changes in light intensity [33].

Light signaling of sufficiently large amplitude (abundant by day – avoided by night) is necessary for having robust circadian rhythms that are hallmarks of health and longevity [34, 35, 36]. Circadian light hygiene (i.e., optimal contrast between sufficient amount of daylight and the absence of light-at-night) facilitates robust circadian rhythms [37, 38], to support the alignment of the circadian system with daily patterns of physical activity to maintain overall health and well-being [39]. A greater difference between sufficiently high daylight exposure and no nocturnal light exposure relates to an optimal circadian light hygiene [40, 41].

In humans and animals, many physiological and even anatomical features, such as the ocular length of the eye undergo about 24-hour oscillations [42, 43, 44, 45]. Diurnal measurements of subfoveal choroidal thickness from 7 AM to 8 PM by optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed that it is typically thicker in the morning and thinner in the evening [44]; the authors concluded that accounting for time is necessary when comparing OCT data. In addition to the central circadian clock in the SCN, the eye also has its own local circadian clocks that regulate various ocular functions [5, 6, 44, 46, 47].

Retinal circadian rhythms are closely related to photoreceptor sensitivity and can be dampened when the amplitude of the 24-hour light-dark signal is small [42]. The sensitivity of photoreceptor cells to light varies throughout the day, with peak sensitivity occurring during the daytime when light is abundant. It is driven by changes in the levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-coupled receptors. The circadian modulation of retinal rhythms relies on the expression of genes such as OPN4 (melanopsin) [48] and OPN5 (neuropsin) [49], which also mediates the light-dependent entrainment of circadian clock genes in the skin [50]. Biochemically, retinal oscillations depend largely on the anti-phase relationship between melatonin and dopamine, in which melatonin inhibits dopamine release during circadian night, while dopamine inhibits melatonin synthesis during the day via dopamine D2-like receptors [42]. Retinal dopamine exhibits a circadian rhythm, with higher concentrations during the day than during the night [42, 44]. It plays a role in regulating retinal function and protecting photoreceptors from damage. A recent study showed that the release of dopamine may rely merely on rod photoreceptors, whose signaling mediates both a suppressive signal at low light intensities and stimulation of dopamine release at very bright light intensities [51].

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye, which experiences about 24-hour variations in thickness and curvature [52, 53, 54, 55], increasing gradually during daytime. Such diurnal increase in corneal thickness, measured by optical pachymeter throughout the day strongly correlates with central corneal sensitivity to mechanical stimuli, measured simultaenously by non-contact pneumatic esthesiometer (r = 0.8) [56]. Similarly, corneal hydration also exhibits a circadian rhythm, with higher hydration levels during the day and lower levels at night [57]. This rhythm can be important for maintaining corneal transparency and refractive power.

The outflow of intraocular fluid, known as aqueous humor, also follows a circadian rhythm. This fluid helps maintain the intraocular pressure (IOP) necessary for the eye to function properly. The ocular pulse, which refers to the rhythmic expansion and contraction of blood vessels in the eye in response to the cardiac cycle, is another aspect that exhibits circadian variations [6, 58]. This pulse helps regulate blood flow to the eye and plays a role in maintaining ocular health. Ocular blood flow and its related variable, ocular perfusion pressure, also show an about 24-hour rhythm, with increased flow during the day and decreased flow at night [59, 60]. It differs largely in phase, however, in humans between health and disease, and between non-human primate species [61]. In view of large individual variability in mean value and circadian phase that may depend on physiological conditions and health status, it helps to normalize variables to enhance the estimation of phase and amplitude of such variables, including IOP [6]. IOP rhythmicity depends on complex factors regulating aqueous humor balance, many of which follow a 24-hour cycle (reviewed in [58, 62, 63]). Typically, IOP peaks at night or early morning in both healthy individuals and normal-tension glaucoma patients, although daytime peaks are also observed. Body position affects IOP, with values increasing by about 5 mmHg in the supine position. Variability of IOP increases and the phase of the IOP rhythm becomes less predictable in conditions like primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and with age. Notably, the 24-hour IOP rhythm tends to shift to later hours in older patients. POAG progression is linked to higher IOP instability, resistance to treatments, and retinal ganglion cell damage [6].

The ability of the lens to change shape to focus light on the retina varies throughout the day. Accommodation amplitude is typically higher during the day and lower at night, although age differences are evident [64]. Seasonal factors [64] and dynamic ambient illumination [65] may modify the accommodation amplitude and its 24-hour pattern. The transparency of the lens also fluctuates in a circadian manner with lowest transparency at night, which is driven by core clock genes [66]. It can be due to changes in hydration and in protein composition of the lens. Additionally, the optical density of the lens, which affects the eye’s ability to focus light onto the retina, can also change throughout the day due to factors like hydration and metabolic processes within the lens. Understanding these circadian changes in the eye is essential for evaluating ocular health and managing ocular diseases.

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) belongs to a heterogeneous group of

neurodegenerative eye diseases, common to which is characteristic optical

neuropathy with corresponding visual field defects due to the progressive death

of RGCs [67], including ipRGCs that are affected in advanced stages of POAG [8, 9, 68]. Elevated IOP remains to date the only modifiable factor in the

development and progression of glaucoma/POAG. Modern methods of treating POAG,

whether by medication or surgery, however, eliminate only the symptom of ocular

hypertension and do not affect the main mechanisms of pathogenesis and do not

take into account the pathophysiology of the disease. Glaucoma has recently been

considered as a common pathological process, with neurohormonal mismatch of many

pathophysiological mechanisms in the body due to dysregulation of biological

rhythms of metabolic and vascular homeostasis [7, 17, 69]. Currently, there is

convincing evidence that besides an elevated IOP, other independent factors are

involved in the progression of glaucoma, including a certain genetic

predisposition [70], vascular dysregulation and ischemia [71, 72, 73], oxidative

stress [74], and inflammation [75]. Glaucoma also involves neuroinflammation

[76], which can alter the function of the SCN and other circadian clock

components [77]. The most straightforward mechanisms include damage of RGCs,

which are essential for transmitting visual information to the brain. This damage

can disrupt the communication between the eye and the SCN, diminish the amplitude

of light signaling between daytime light and nocturnal darkness, consequently

leading to changes in circadian amplitude and phase. A smaller amplitude of light

signaling leads to a delay in circadian phase and compromised sleep [4, 7]. Our

recent research showed that glaucoma is associated with complex disruptions in

systemic and local circadian rhythms [4, 5, 6, 7, 17]. These disruptions include

circadian misalignment between systemic and local rhythms [6], alterations in

sleep [4, 5, 7], mood [4, 16], and metabolism [17] (Table 1, Ref. [3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17], Fig. 1). Impaired circadian rhythms can further destabilize many vital

functions, contributing to the development and progression of chronic diseases,

including exacerbating glaucoma itself. These disruptions affect the coordination

of the sleep-wake cycle, mood regulation, antioxidant defenses, immune function,

and metabolism, creating a vicious cycle that perpetuates health issues.

Glaucoma-induced disturbances in the retina’s circadian rhythms, which govern

aspects such as photoreceptor sensitivity, dopamine secretion, and retinal blood

circulation, may exacerbate retinal injury and progressive vision impairment,

thereby perpetuating a detrimental cycle. POAG progression impairs both

image-forming and non-image-forming visual functions attributable to RGCs. Recent

research [78] identified a significant correlation between glaucoma severity and

impaired function of ipRGCs, independently of confounding variables. IpRGCs,

pivotal in relaying non-image-forming photic input to the circadian clock, become

dysfunctional early in glaucoma, diminishing light signals to the SCN [8, 79, 80]. This dysfunction disrupts circadian rhythms, impairs sleep, and alters mood,

with an associated increase in depression scores [4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Glaucoma patients

have an increased risk of developing mood disorders, such as depression [81] and

anxiety [82, 83]. Compared to age-matched controls, POAG patients exhibit

circadian rhythm alterations, which are exacerbated with disease advancement [4, 6], paralleling the progressive loss of ipRGCs [9]. Glaucoma has been linked to

an increased risk of metabolic disorders, particularly lipid metabolism.

Compromised light perception due to RGCs loss is associated with serum lipids

being unevenly altered in the morning vs. the evening [17]. Metabolic

disturbances in POAG are very similar to what has been termed “circadian

syndrome” [83, 84]. It is particularly evident for diurnal lipid metabolism,

which emerges alongside POAG progression [17]. RGCs loss in POAG related to lipid

metabolism in a time-dependent manner, and was linked to a decrease in

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and in increase in triglycerides

(TG) in the morning, while total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol (LDL-C) increased in the evening. Such a positive

morning

| Marker | Mild Glaucoma | Advanced Glaucoma |

| ipRGCs | Preserved [9] | Affected [8, 9] |

| Melatonin | Preserved amplitude and phase [5] | Delayed with smaller amplitude (can depend on SNPs, e.g., MTNR1B rs10830963) [5] |

| Systemic circadian phase (Tb) | Preserved position, reduced inter-daily phase stability [4] | Delayed position, reduced stability [4] |

| Circadian amplitude (Tb) | Preserved [4] | Reduced [4] |

| Circadian alignment local (IOP) vs. systemic (Tb) | Slightly changed [6] | Profoundly changed [6] |

| Systemic circadian robustness (Tb) | Lowered Tb [4]; Lowered inter-daily stability of circadian activity rhythm [14] | Much lowered, Tb [4] |

| Local circadian amplitude (IOP) | Slightly Increased [6] | Increased (can depend on gene polymorhisms, e.g., ACE I/D) [6] |

| Local circadian robustness (IOP) | Increased phase scatter, Amplitude-to-Mean MESOR preserved [6] | Decreased robustness: increased phase scatter, Amplitude-to-Mean MESOR increased [6] |

| Sleep | Increased wake after sleep onset, decreased sleep efficacy [10, 12, 14] | Decreased nocturnal sleep efficacy [3, 10, 11]; Bedtime delayed; Sleep duration shortened [4, 12] |

| Shorter sleep duration [12]; Longer and shorter sleep duration associates with prevalence of glaucoma [13] | ||

| Mood | Mild decrease in mood, weak correlation with RGCs loss [16] | Depression score strongly correlates with RGCs loss (may depend on SNPs, e.g., G-protein GN |

| Circadian syndrome | Mild adverse changes in lipid metabolism [17] | Profound changes, evening gradient in elevation of LDL-C correlates with RGCs loss (can depend on SNPs, e.g., CLOCK rs1801260) [17] |

Notes: Tb, body temperature; IOP, intraocular pressure; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphism; MTNR1B, melatonin nuclear receptor 1b; ACE I/D, Alu-repeat deletion/insertion in angiotensin converting enzyme gene; RGCs, retinal ganglion cells; MESOR, Midline Estimating Statistics of Rhythm.

Glaucoma patients show diminished post-illumination pupil responses [79] and reduced nocturnal melatonin suppression by light [78]. Melatonin synthesis is also compromised in POAG [5, 7, 85], with clinical data indicating shifts in the timing and average production levels of endogenous melatonin [5]. Notably, advanced POAG stages present pronounced alterations, including in the timing of peak melatonin secretion. These changes may arise from various factors, such as decreased light sensitivity and specific gene polymorphisms that heighten susceptibility. Our investigations of 24-hour salivary melatonin profiles under controlled lighting conditions, alongside analyses of clock genes and MTNR1B melatonin receptor gene polymorphisms [5], revealed that stable POAG patients maintain normal circadian rhythms of salivary melatonin and body temperature. However, these rhythms are delayed in advanced POAG, with a reduction in both the 24-hour mean value and circadian amplitude of melatonin [4, 5, 7]. Specifically, carriers of the MTNR1B rs10830963 G-allele with advanced POAG exhibited these alterations. This allele was also linked to altered melatonin patterns [86] and metabolic susceptibility to poor light hygiene [40]. Pronounced circadian phenotype changes in POAG patients occur when multiple factors converge, such as significant RGC loss in individuals with genotypes associated with extended melatonin production. The MTNR1B rs10830963 G-allele, while primarily linked to increased fasting glucose levels and type 2 diabetes risk, is also implicated in POAG development, independently of diabetes [87], suggesting melatonin’s broader physiological roles in POAG pathogenesis.

OCT. Recent advancements in glaucoma diagnosis have been marked by the adoption of sophisticated diagnostic studies, particularly those involving the visualization of the optic nerve disc (OND) [88, 89, 90]. Structural OCT and OCT angiography (OCTA) facilitate retinal imaging, yielding high-resolution morphological insights into the retinal and choroidal strata. OCT’s diagnostic utility in glaucoma is substantial, enabling the assessment of OND parameters, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the ganglion cell complex, encompassing approximately 20 morphometric parameters [88, 89, 90]. The hierarchy of diagnostic relevance among OCT parameters for glaucoma diagnosis can be delineated as follows: the global volume loss index (GLV), the mean thickness of the ganglion cell complex (GCC Average), the thickness of the GCC in the inferior segment (GCC Inferior), and the thickness of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer in the lower temporal quadrant (RNFL IT Thickness). The neuroretinal rim volume (Rim Volume) also possesses considerable diagnostic value, albeit less than that of the GCC complex and retinal nerve fiber layer parameters. This sequence of the five most informative morphometric parameters may serve as a systematic algorithm for interpreting OCT findings in glaucoma diagnosis, with the majority characterizing the RGC complex [91]. In glaucoma monitoring, the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber parameters are of paramount diagnostic importance, specifically the thickness of the peripapillary fibers in the lower temporal and upper temporal quadrants (RNFL IT and ST Thickness) and the average thickness of the peripapillary fibers (RNFL Average Thickness). The GLV of the GCC complex also demonstrated high diagnostic informativeness. OCT exhibits exceptional sensitivity in both diagnosing and monitoring glaucoma. In the early detection of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) using OCT, the most informative morphometric parameters pertain to the characteristics of the retinal ganglion cell complex [92, 93, 94, 95]. Contemporary research [96, 97, 98, 99] has furthered diagnostic enhancements in glaucoma by introducing an innovative optic nerve head feature derived from OCT images and leveraging deep learning to significantly surpass existing models in automated detection accuracy.

Pattern Electroretinography (PERG) is a useful tool used to assess the functionality of RGCs. PERG measures the electrical responses of the retina to visual stimuli, specifically patterned stimuli such as alternating black and white checkerboards or gratings. The PERG response is generated primarily by the RGCs and their axons, making it a sensitive indicator of their functional status in glaucoma, when the loss of RGCs leads to a reduction in the amplitude of the PERG signal [100]. This reduction can be detected even in the early stages of the disease, before significant visual field loss occurs, making PERG a useful tool for early diagnosis and monitoring of glaucoma progression. Additionally, PERG can be used to monitor the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions aimed at preserving RGC function [101]. Amplitudes, assessed by PERG can vary time-dependently, as are changes after melatonin treatment [5].

Pupillary Light Reflex (PLR). PLR assesses the response of the pupil to light stimuli. The melanopsin-mediated response can be isolated by using specific wavelengths and intensities of light, providing insights into ipRGC function [102, 103]. By using specific wavelengths (typically in the blue range, around 480 nm) and controlled intensities of light, the melanopsin-driven response can be isolated, allowing researchers to assess ipRGC function independently of the rods and cones. This selective stimulation helps to evaluate the contribution of ipRGCs to the overall pupillary response and provides insights into their role in regulating non-visual processes, such as circadian rhythms and light-induced mood regulation.

Elucidating the relationship between glaucoma and circadian rhythm disturbances is pivotal for the strategic management of the disease. Given the evidence that glaucoma can disrupt the intrinsic circadian rhythms within the ocular environment, the development of therapeutic interventions focused on reinstating these rhythms may prove instrumental in the protection of RGCs and the conservation of visual function. The translation of a body of knowledge accumulated by circadian biology into personalized circadian medicine should improve the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [18, 42]. Strategies to improve circadian health focus on achieving a balance between the timing and quantity of melatonin and exposure to daylight. Enhancing circadian signals through exposure to daylight [104, 105, 106, 107] and/or the administration of melatonin during nighttime [5, 108, 109] can fortify the circadian system. Enhancing lighting conditions with adjustable lighting systems has been shown to have a positive influence on the mood and behavior of elderly individuals [110, 111]. Key regulators of the circadian clock in the brain, such as light and the hormone melatonin, can potentially alleviate, and perhaps even prevent neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration [5, 7, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116].

Consistent with phase response curves [117, 118, 119], exposure to morning/daytime light and the use of evening/nocturnal melatonin can facilitate advances in circadian phase, mitigating the negative consequences associated with late chronotypes [120, 121, 122, 123]. Furthermore, melatonin, as a ubiquitous molecule has profound antioxidant properties [124, 125], complemented by specific receptor interactions [126, 127], altogether offering multi-facet therapeutic benefits for various eye diseases, including glaucoma, dry eye, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, and uveitis, through its neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and IOP-lowering effects [128, 129], particularly when administered topically using advanced nanotechnological formulations to enhance its ocular delivery [130]. Combining light therapy with melatonin [131, 132] or physical activity [133] may be more effective in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases than strategies without combination of these factors. Timed physical activity also shows promise in this regard [134]. Maintaining regular patterns of light exposure may aid in the maintenance of sleep regularity, even in healthy young adults [135]. The effect of physical activity as an isolated factor on the development and progression of glaucoma remains ambiguous [136, 137, 138, 139, 140]. Nonetheless, it is plausible that this effect may exhibit variability across different demographic groups, manifesting more significantly in certain populations compared to others. It suggests a potential interplay between physical activity and population-specific characteristics that warrants further investigation to elucidate the mechanisms involved. The role of circadian timing in the context of physical activity and its correlation with exposure to daylight to prevent circadian disruption [39] is a subject that has not received adequate scholarly attention. Overall, improving circadian health requires the preservation of adequate amplitude, alignment of phases, and stability of the signals that regulate key bodily functions (such as activity, temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure), which can be monitored using wearable devices.

Modulation of circadian light input during the day and melatonin release at night can enhance circadian rhythmicity by improving amplitude, phase alignment, and robustness of signals in overt circadian rhythms. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of studies investigating light or melatonin therapies tailored to an individual’s circadian phase or chronotype. A recent phase 2 clinical trial demonstrated that targeted daylight therapy led to enhanced deep sleep quality in individuals with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease. Notably, no significant difference was observed between controlled daylight therapy and melanopsin booster light therapy [108]. These results suggest that personalized indoor daylight interventions may hold promise for improving sleep patterns in early to moderate stages of neurodegenerative disease, highlighting the need for further exploration, particularly in advanced stages of glaucoma. It is essential that recommendations for achieving an optimal equilibrium between the potential risks associated with blue light exposure and the advantageous effects of red light exposure, as delineated by Ahn et al. (2023) [141] for photobiomodualtion strategies, incorporate the critical element of (circadian) timing. This inclusion is imperative to fully understand the multifaceted effect of light exposure on human health, taking into account the temporal aspects that may influence the biological outcomes.

Chronotherapeutic approaches aimed at further personalizing the timing of interventions according to individual chronotype or marker-rhythm phase position can be pivotal to enhance the efficacy of interventions while reducing its side-effects [18]. Several strategies can be employed to quantify circadian rhythm parameters, such as phase and amplitude, potentially enabling personalized timing of therapies. Actigraphs and wearable technology can monitor physiological markers like body temperature, physical activity, and, particularly relevant in ophthalmology, light exposure. Emerging devices are also capable of measuring local rhythms, such as IOP, in a less obtrusive manner. In the future, integrating these tools could enable clinicians to develop tailored chronotherapy plans, optimizing treatment efficacy and reducing neurodegenerative risks [18]. Researchers are exploring the potential of such as light therapy [141, 142] and melatonin supplementation [5, 7, 143] to protect retinal cells [144, 145] and improve sleep quality in glaucoma patients. Furthermore, addressing sleep disturbances in glaucoma patients may help to improve their overall health and well-being. Novel techniques available for monitoring circadian rhythms in glaucoma patients may help to identify those at risk of developing complications and guide treatment decisions [62, 146, 147].

This review explores the intricate connection between glaucoma and circadian rhythm disturbances, focusing on the crucial role of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) in regulating circadian rhythms through light signals transmitted to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). It highlights the impact of glaucomatous retinal damage on circadian disruption that involves systemic and local circadian rhythms, sleep, mood, and metabolism; and proposes strategies for enhancing circadian health in glaucoma patients, such as timed light exposure, melatonin supplementation, and lifestyle modifications. The review emphasizes the significance of understanding the complex interaction between circadian regulation and glaucoma progression, highlighting the need for further research. Promising findings suggest that combining light therapy, melatonin supplementation, and physical activity may be beneficial in managing glaucoma and other neurodegenerative diseases [7, 8, 39, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137]. Recommendations are made to consider circadian timing when determining optimal light exposure. This includes weighing the advantages and disadvantages of different types of light, such as blue and red lights. In this review, we aim to foster additional research efforts to better understand the link between glaucoma and circadian disruption. We also aim to develop effective interventions, such as chronotherapeutics, light therapy, and melatonin supplementation. These interventions can help protect retinal cells, improve sleep quality, and promote overall health in individuals with glaucoma.

Conceptualization, DG, TM, DW and GC; collection and analysis of literature, DG, TM, EZ, SA; writing—original draft preparation, DG; writing—review, revision and discussing, DG, TM, DW, EZ, SA and GC; supervision and resources supply, DG, TM, EZ; funding acquisition, DG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues: Sergey Kolomeichuk for his valuable insights into genetics, and ophthalmologists Yulia Filippova and Anastasia Vlasova for their indispensable support during research sessions.

The study was supported by the West-Siberian Science and Education Center, Government of Tyumen District, Decree of 20.11.2020, No. 928-rp. The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research. The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.