1 Department of Hematology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, 310009 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Hematology, Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province Affiliated to Wenzhou Medical University, 317000 Taizhou, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

In this comprehensive review, we delve into the transformative role of artificial intelligence (AI) in refining the application of multi-omics and spatial multi-omics within the realm of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) research. We scrutinized the current landscape of multi-omics and spatial multi-omics technologies, accentuating their combined potential with AI to provide unparalleled insights into the molecular intricacies and spatial heterogeneity inherent to DLBCL. Despite current progress, we acknowledge the hurdles that impede the full utilization of these technologies, such as the integration and sophisticated analysis of complex datasets, the necessity for standardized protocols, the reproducibility of findings, and the interpretation of their biological significance. We proceeded to pinpoint crucial research voids and advocated for a trajectory that incorporates the development of advanced AI-driven data integration and analytical frameworks. The evolution of these technologies is crucial for enhancing resolution and depth in multi-omics studies. We also emphasized the importance of amassing extensive, meticulously annotated multi-omics datasets and fostering translational research efforts to connect laboratory discoveries with clinical applications seamlessly. Our review concluded that the synergistic integration of multi-omics, spatial multi-omics, and AI holds immense promise for propelling precision medicine forward in DLBCL. By surmounting the present challenges and steering towards the outlined futuristic pathways, we can harness these potent investigative tools to decipher the molecular and spatial conundrums of DLBCL. This will pave the way for refined diagnostic precision, nuanced risk stratification, and individualized therapeutic regimens, ushering in a new era of patient-centric oncology care.

Keywords

- diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- spatial multi-omics

- artificial intelligence

- precision medicine

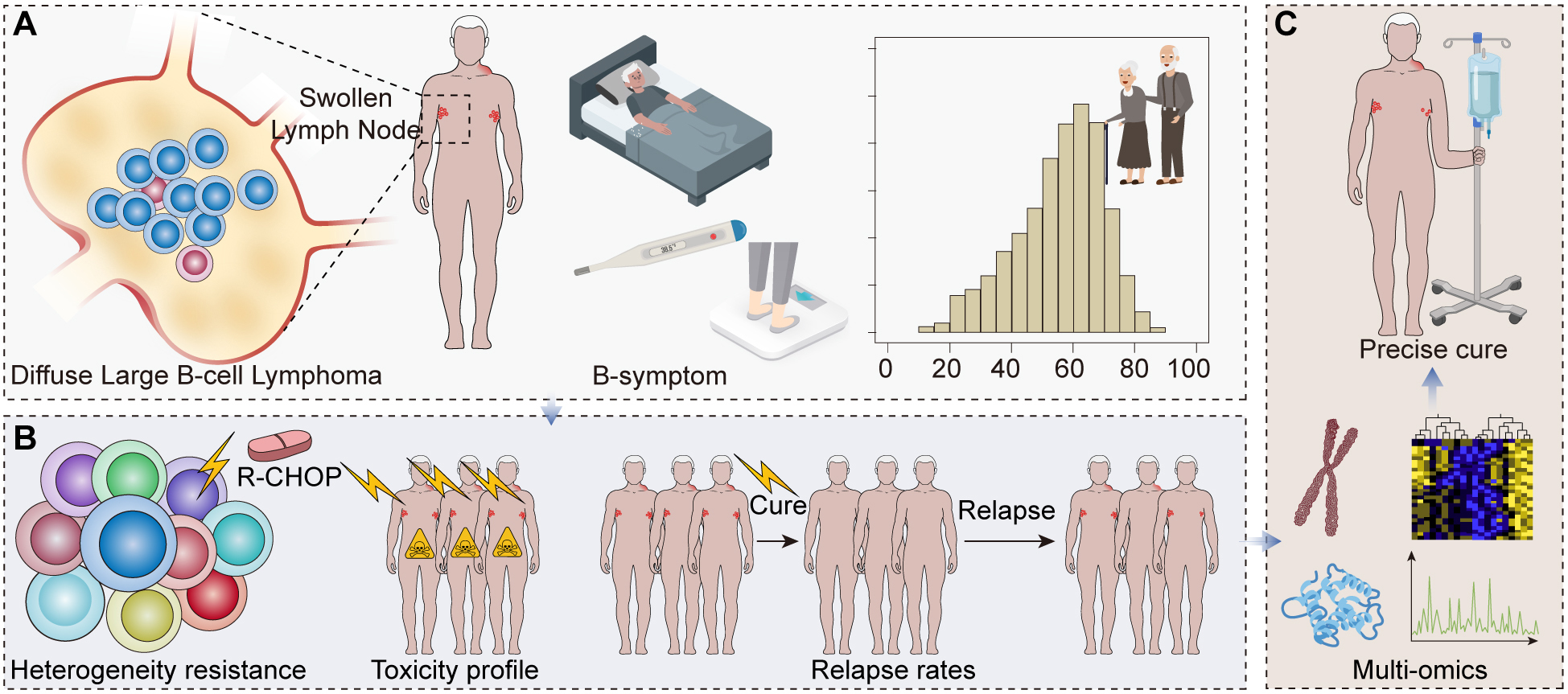

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for approximately 30% of new NHL cases worldwide, with a higher prevalence in developed countries [1]. It is identified by the uncontrolled growth of large-sized, atypical B cells widely scattered in lymph nodes [2] (Fig. 1). DLBCL usually appears as a rapidly growing lymph node mass accompanied by symptoms of systemic illness including fever, night sweats, and weight loss [3]. The disease typically strikes older people, diagnosed at a median age of approximately 70 [4] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The role of precision medicine and multi-omics in understanding and treating diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). (A) A graphical representation of DLBCL pathology with an illustration of diffuse large B-cell proliferation in a lymph node, coupled with a demographic chart highlighting the prevalence in older populations. (B) A chart showing the efficacy of the standard rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) treatment, displaying the split between responsive and non-responsive or relapsed patients. (C) A diagram emphasizing the heterogeneity of DLBCL and the shift towards personalized medicine illustrates the diversity of treatment responses and the move away from ‘one-size-fits-all’ therapies.

Despite the availability of aggressive treatment regimens, including the combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), the clinical outcomes for DLBCL patients vary substantially. Approximately 40% of patients do not respond to initial therapy or relapse after the initial response, leading to a poor prognosis [5]. The clinical heterogeneity of DLBCL calls for precision medicine approaches to better stratify patients and guide therapy [6] (Fig. 1).

The broad spectrum of clinical and biological heterogeneity of DLBCL complicates the task of optimizing the treatment for individual patients. The current treatment strategies, mainly the R-CHOP regimen, do not consider the intrinsic variability in tumor biology and patient characteristics, the therapeutic response rates are variable, and the clinical outcomes are diverse [7]. Potential guidance for personalized treatment selection, guided by molecular profiling of individual tumors, is one of the promises of precision medicine [6] (Fig. 1). The recent development of multi-omics and spatial multi-omics approaches offers the possibility to understand the molecular complexity of DLBCL better and design personalized treatment strategies [8].

Multi-omics involves genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data to analyze biological samples deeply. In DLBCL, multi-omics analysis has detected molecular heterogeneity, identified subtypes with distinct features, and improved pathogenesis [9]. Genomic analysis has revealed recurrent mutations and chromosomal alterations, which shed light on disease drivers and potential therapeutic targets [10, 11, 12]. Transcriptomic profiling has refined the classification of DLBCL by identifying subtypes with different origins and therapeutic responses [6, 13, 14, 15]. Proteomic and metabolomic studies have provided insights into protein expression changes and metabolic alterations relevant to DLBCL pathophysiology [16, 17, 18]. Spatial multi-omics is a technique that integrates molecular data with tissue architecture, which gives “insights” relating to tumor microenvironment, immune interactions, and structural organization. Tissue structure is used primarily in the study of tumor microenvironment, tumor response to therapy, and the clinical management of cancers [19, 20, 21, 22]. These methods are avenues for precision medicine in DLBCL.

Artificial intelligence (AI) integration into multi-omics research is necessary to revolutionize our comprehension and management of complex diseases like DLBCL. Moreover, it has been noted that AI, in the form of machine learning (ML) algorithms, can be utilized to examine vast and intricate datasets beyond the human brain’s capacity for discerning patterns and associations [23]. Deep learning, a subcategory of ML, unifies different -omics data types to characterize DLBCL pathogenesis and progression [24]. Disease outcome prognoses by AI-based models are useful for patient stratification and identifying therapeutic responses [25]. Besides, natural language processing (NLP) pulls structured information from unstructured data sources that strengthen multi-omics analysis [26]. Nevertheless, challenges concerning the standardization of data, interpretability of results, and generalizability to other scenarios still hinder the use of AI in this area [26]. Combining multi-omics with artificial intelligence (AI) could be a game changer for DLBCL research.

The article examines the status of multi-omics and spatially based multi-omics techniques driven by AI in the study of DLBCL. The aim is to critically evaluate how these integrative technologies improve our understanding of molecular and spatial heterogeneity characterizing DLBCL, outline difficulties faced, and suggest possible solutions. This review also investigates the synergy between AI and multi-omics for precision medicine in DLBCL. In conclusion, this manuscript summarizes the transformative potential of AI in improving precision medicine, focusing on diagnostic improvement, specifically early-stage treatment.

DLBCL, the predominant form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, exhibits a vast heterogeneity that manifests in its histopathological presentation and molecular underpinnings [27]. Histologically, DLBCL is marked by the diffuse proliferation of large B lymphoid cells, which surpass the size of normal macrophage nuclei within lymph nodes. This proliferation is often accompanied by a high mitotic rate and can include necrotic areas [28]. The disease is morphologically diverse, encompassing variants such as centroblastic, immunoblastic, T-cell/histiocyte-rich, and anaplastic types, each with distinct histological features [29].

Molecularly, DLBCL is stratified into subtypes based on the cell-of-origin (COO) classification, which includes germinal center B-cell-like (GCB), activated B-cell-like (ABC), and an unclassified category. These subtypes are discernible by their unique gene expression profiles and are closely linked to clinical outcomes. Patients with ABC-DLBCL tend to have a less favorable prognosis than those with GCB-DLBCL [13, 30]. Recent genomic explorations have unveiled recurrent mutations, with MYD88 and CD79B mutations frequently observed in the ABC subtype [31]. Advances in multi-omics analyses, integrating genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic data, have allowed for delineating distinct molecular subgroups, suggesting varied therapeutic vulnerabilities within this complex disease landscape [6].

The intricate histopathological and molecular attributes of DLBCL underscore the disease’s heterogeneity, which is critical for assessing prognosis and individualizing treatment modalities. Thus, it emphasizes the need for precision approaches in therapeutic intervention and management.

Traditionally, the diagnosis of DLBCL relies on histological examination of biopsy tissue, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and conventional cytogenetic analysis [29]. However, these methods have several limitations. Specifically, IHC often requires subjective interpretation and can lead to misclassification of the disease, especially in the distinction between the germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC) subtypes [32]. Additionally, conventional cytogenetic techniques may miss cryptic or submicroscopic genetic alterations with prognostic or therapeutic implications [33].

In terms of therapy, R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) remains the standard first-line treatment for DLBCL [5]. However, approximately one-third of patients are refractory to R-CHOP or relapse after an initial response [34]. This reflects the heterogeneity of DLBCL, as different subtypes and genetic variants may respond differently to R-CHOP [35].

Furthermore, R-CHOP can have serious side effects, including myelosuppression, infection, cardiotoxicity, and secondary malignancies [36]. The treatment is particularly challenging in elderly patients, who often have comorbidities and may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy [37].

In summary, traditional diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for DLBCL face significant limitations due to their inability to fully capture the heterogeneity of the disease and lack of personalization in treatment.

Multi-omics is an integrated research approach that combines data from multiple ‘omics’ fields, such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, to comprehensively understand complex biological systems [38].

The importance of multi-omics lies in its capacity to provide a holistic view of the molecular mechanisms underlying biological processes and diseases. By examining multiple layers of biological information, multi-omics allows for a more complete understanding of disease pathogenesis than single ‘omics’ studies [39].

In the context of cancer research, including DLBCL, multi-omics approaches have the potential to reveal the complex interplay between genetics, epigenetics, and environmental factors that drive tumorigenesis and influence treatment response [40]. Integrating genomics and transcriptomics data can uncover the functional consequences of genetic alterations while combining proteomics and metabolomics data can shed light on the metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells [41, 42].

Multi-omics profiling can inform the development of personalized medicine strategies by identifying molecular subtypes of diseases, novel therapeutic targets, and biomarkers for predicting treatment response and prognosis [38].

In summary, multi-omics represents a powerful tool for unraveling the complexity of biological systems and diseases, with promising applications in precision medicine.

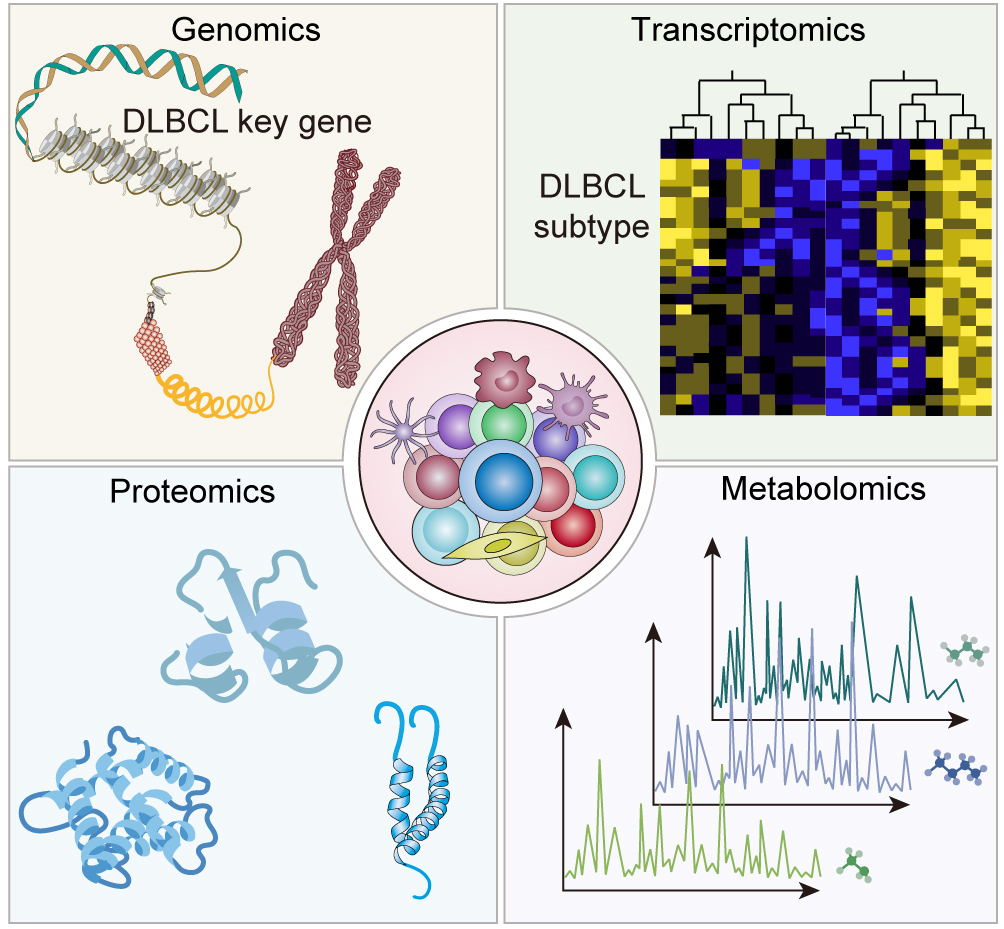

Genomics has been instrumental in unraveling recurrent genetic alterations that contribute to the pathogenesis of DLBCL and consequently improve our understanding. Genomic studies have identified multiple mutations within genes involved in crucial cellular pathways. Mutations affecting B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathways [43, 44, 45] have been reported in DLBCL, which is essential for B-cell development and activation. Further, genome-wide studies have shown various modifications of genes associated with chromatin remodeling as a process of modifying chromatin structure determining gene expression. In DLBCL, however, such are deregulated leading to abnormal gene expression patterns that can affect the disease progression [46, 47]. Genomic studies have revealed numerous mutations within genes, such as those linked with programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1). These mutations may hinder interaction between immune system cells and DLBCL cells, thus modulating response to immunotherapies [48]. Furthermore, genomic analysis has demonstrated that diverse molecular subtypes of DLBCL have varied genetic profiles and clinical outcomes [14]. The two major subtypes are the germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC) types [49]. These subtypes show differences in their gene expression profiles and molecular attributes, reflecting variations in their intrinsic biology or possible treatment responses. Consequently, comprehending the two major subtypes is crucial for improving the outcomes of patients as well as optimizing treatment choices. Genomics studies have identified such recurrent genetic alterations and molecular subtypes, which provides crucial insights into DLBCL pathogenesis and its underlying heterogeneity (Fig. 2). This information may help direct the development of personalized treatment strategies and targeted therapies for DLBCL patients.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The power of multi-omics integration: unraveling the complexity of DLBCL.

Transcriptomics: Transcriptomics has played a role in understanding DLBCL by studying gene expression patterns using RNA sequencing. One key aspect of transcriptomics is the discovery of subtypes within DLBCL, which complements the classification based on features. Through analyzing gene expression, a subset with a host response signature has been found, showing immune infiltration. This subset is linked to a prognosis, highlighting the significance of the response in determining DLBCL outcomes [15]. Transcriptomic investigations have also given a glimpse of the functional implications behind the recurrent genetic changes seen in DLBCL. Examining gene expression changes associated with a given mutation or genetic abnormality could help determine how the mutation alters cellular functions and signaling pathways [50]. In addition, transcriptomics has contributed to uncovering the dysregulated signaling pathways in DLBCL. This gives critical information about the molecular drivers of the disease and allows for the development of targeted therapeutics that can alter only those known pathways [31] (Fig. 2).

Proteomics: Several groups have used proteomic technologies, including mass

spectrometry, to identify DLBCL protein changes, resulting in an understanding

of the perturbations that can alter protein functions and cellular response

post-transcriptionally and post-translationally. The application of mass

spectrometry-based analysis has resulted in a variety of different

identifications of protein alterations in DLBCL [51, 52]. These alterations

include differential protein expressions, post-translational modifications (e.g.,

phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation), and protein-protein interactions

[53]. These discoveries have brought the identification of dysregulated cellular

pathways and signaling networks in DLBCL to light. Proteomic studies have

captured abnormal phosphorylation events in key signaling pathways relevant to

DLBCL pathobiology, including the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway [54],

the phosphatidylinositol 3′ -kinase (PI3K)-Akt (PI3K-AKT) pathway [55], and the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-

Metabolomics: Metabolomics has been used to provide new insight into DLBCL, unveiling the metabolic reprogramming that supports the distinguishing hallmark of this disease. Metabolic reprogramming in DLBCL: One of the key metabolic alterations identified in DLBCL is metabolic reprogramming. To meet the increased energy and biosynthesis demands, DLBCL cells undergo a metabolic reprogramming to rely on nuclear-pentose phosphate pathway (n-PPP), which potentially favors rapid proliferation and survival. Two pivotal changes in metabolism, identified in metabolomic studies, include potentiated glycolysis and glutaminolysis (Fig. 2). In addition, the metabolomic studies also showed dysregulation of lipid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and others in DLBCL. These changes all feed into the widespread metabolic reprogramming in DLBCL to enable the aggressive growth characteristic of DLBCL cells [57, 58, 59].

In conclusion, multi-omics data integration has significantly enriched our understanding of DLBCL, revealing the complex interplay between genetic, transcriptional, translational, and metabolic changes underlying this disease.

Spatial multi-omics is an emerging field that combines traditional multi-omics analysis with spatial context within biological tissues. Traditional multi-omics approaches, which include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, provide a comprehensive view of the molecular mechanisms within a cell. However, these methods often neglect the spatial context of these molecular events. Spatial multi-omics fills this gap by preserving the spatial information during the analysis, thereby providing a comprehensive, contextual view of the molecular landscape within tissues [22].

The significance of spatial multi-omics lies in its ability to provide a more holistic view of biological tissues. By preserving the spatial information, researchers can correlate molecular events with their precise location within the tissue, leading to a more thorough understanding of the complex interplay between cells and their environment. This is particularly important in diseases such as cancer, where the tumor microenvironment plays a critical role in disease progression and response to treatment [60].

Spatial multi-omics has wide-ranging applications in biology and medicine. It has been utilized to study the complex tissue architecture of the brain, the heterogeneous tumor microenvironment in cancer, and the intricate cellular interplay in the immune system. One study has provided novel insights into disease mechanisms, leading to the identification of new therapeutic targets [61].

The future of spatial multi-omics is promising. As technology advances, we can expect more accurate, high-throughput methods to capture a broader range of molecular events. This will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of complex diseases and pave the way for personalized medicine [62].

DLBCL is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, characterized by significant heterogeneity at the clinical, pathological, and molecular levels [13]. Spatial multi-omics has recently been applied to DLBCL research, providing vital insights into the tumor microenvironment and the spatially distinct molecular patterns within the tumor [22].

Spatial multi-omics has revealed intricate heterogeneity within DLBCL tumors. By capturing the spatial context of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data, researchers have identified distinct subpopulations of cancer cells within a single DLBCL tumor, each characterized by unique molecular profiles [61].

The application of spatial multi-omics in DLBCL has also significantly advanced our understanding of the tumor microenvironment. The spatial distribution of immune cells and their interactions with cancer cells have been mapped in detail, shedding light on the complex interplay between the immune system and cancer cells and its impact on disease progression and treatment response [60].

Spatial multi-omics has not only deepened our understanding of DLBCL but has also opened new avenues for treatment. More targeted and personalized treatment approaches can be devised by identifying molecularly distinct subpopulations of cells and understanding their spatial distribution within the tumor [63].

The seminal work of Chapuy et al. [15] on multi-omics highlighted the utility of integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data to stratify DLBCL into five molecular subtypes with distinct characteristics [6]. Their genomic data, derived from whole-exome sequencing, provides insights into somatic mutations and copy number variations. Transcriptomic data from RNA sequencing offers a landscape of gene expression, while epigenomic data, acquired through DNA methylation profiling, reveals patterns of epigenetic modifications across the subtypes.

The analytical tools employed in this study included bioinformatic pipelines for variant calling, differential gene expression analysis, and methylation array analysis. Unsupervised clustering algorithms, such as hierarchical clustering, delineated molecular subtypes based on the multi-dimensional data. The biological insights gained included the identification of unique driver mutations, dysregulated pathways, and epigenetic markers that define each subtype, offering new avenues for targeted therapies and prognostic biomarkers.

Schmitz et al. [6] focused on the genetic underpinnings of DLBCL by integrating whole-exome sequencing with transcriptomic data to unearth four genetic subtypes. Advanced computational methods, such as mutual exclusivity analysis and gene set enrichment analysis, were applied to dissect the intricate network of genetic interactions and pathway involvements.

The study by Schmitz et al. [6] provided a nuanced genetic classification system that holds prognostic value and identifies actionable targets. For instance, one subtype, characterized by B-cell receptor pathway mutations, might be amenable to B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors.

Vickovic et al. [64] took advantage of the spatial transcriptomics platform to map the gene expression landscape of DLBCL in relation to the tumor’s histological structure. This technique enabled the generation of spatially resolved gene expression data by capturing RNA from histological tissue sections and associating each transcript with its original location.

The analytical methodology involved spatial barcoding, image registration, and computational deconvolution to integrate the spatial information with gene expression profiles. Vickovic et al.’s study’s [64] insights provided a molecular counterpart to the morphological features observed in DLBCL, which has implications for understanding the tumor microenvironment and its role in lymphomagenesis.

Moncada et al. [65] combined spatial transcriptomics with single-cell RNA sequencing to elucidate the cellular heterogeneity and spatial organization within DLBCL tumors. Single-cell RNA-seq provided a high-resolution view of the transcriptomic diversity at the individual cell level. At the same time, spatial transcriptomics offered a global view of the spatial distribution of these heterogeneous populations.

These datasets were integrated using computational frameworks that allow for the alignment of single-cell transcriptomic data with spatial gene expression patterns. This multi-faceted approach uncovered spatially distinct cell subpopulations, which could have profound implications for understanding the microenvironmental niches within DLBCL, identifying potential therapeutic strategies, and predicting treatment responses.

The multi-omics and spatial multi-omics studies by Chapuy et al. [15], Schmitz et al. [6], and Davidson-Moncada et al. [66] have collectively advanced our understanding of DLBCL’s molecular and spatial heterogeneity. These studies have laid the groundwork for precision medicine by uncovering distinct molecular subtypes and spatial heterogeneity.

The identification of genetic and epigenetic alterations, as well as the spatial organization of tumor cells, provides critical insights for the development of personalized therapies. For instance, targeting subtype-specific driver mutations or dysregulated pathways can lead to more effective and less toxic treatments.

Furthermore, understanding the spatial heterogeneity within DLBCL tumors can lead to strategies that account for the tumor’s microenvironmental complexity, potentially improving the efficacy of immunotherapies or other targeted treatments. This could involve spatially targeted drug delivery or the modulation of the tumor microenvironment to enhance treatment response.

In conclusion, these case studies underscore the transformative potential of multi-omics and spatial multi-omics in pursuing precision medicine for DLBCL. They exemplify how integrating diverse data types can yield a more comprehensive understanding of cancer biology, ultimately guiding the development of more personalized and effective therapeutic strategies. Continued research in this domain is expected to refine our understanding of DLBCL further and improve patient outcomes in the clinical setting.

AI has emerged as a transformative force in biomedical research, particularly in analyzing complex datasets generated by multi-omics studies. AI encompasses a suite of computational techniques that emulate aspects of human cognition, such as learning and problem-solving, to process and interpret data. ML, a subset of AI, involves algorithms that enable computers to learn from and make predictions or decisions based on data [67]. This capability is particularly pertinent to biomedical research, where the volume and complexity of data have outstripped the capacity of conventional statistical approaches.

Supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning are three broad categories of ML algorithms. Support vector machines (SVMs) are a group of powerful supervised learning algorithms used for classification in a wide range of biomedical research. SVMs find a hyperplane that maximizes the margin between classes—so it classifies more effectively [68]. On the other hand, random forests are ensemble learning methods that combine multiple decision trees to make predictions [69]. They can deal with high-dimensional data and encode complex relationships. Applications of unsupervised learning algorithms are used to extract the patterns or clusters in the data that have no previous labels. This feature makes them ideal for conducting exploratory analysis and discovering hidden structures within datasets. For example, K-means clustering is a method of clustering data into a set number of clusters using data point similarity. Data points are associated with the nearest mean of a cluster [70]. Principal component analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction method that can convert high-dimensional data into a set of lower-dimension data reflecting most of the information in the data [71]. Reinforcement learning is a ML technique that learns to act in a dynamic environment to obtain a reward [72].

The advent of transformer models, initially conceived for complex sequence-based tasks in natural language processing (NLP), presents a novel paradigm for analyzing multi-omics data in DLBCL research [73]. These models, particularly noteworthy for their self-attention mechanisms, can recognize intricate patterns within vast datasets, making them well-suited for identifying biomarkers and therapeutic targets [74]. Transformers can be applied to multi-omics data by treating molecular profiles as sequences, where each omics feature—be it a gene expression level, a mutational status, or an epigenetic mark—can be considered analogous to a word in a sentence [46]. This allows for capturing long-range dependencies between disparate omics features, potentially unraveling complex biological interactions that underpin DLBCL pathogenesis and patient heterogeneity [75].

In DLBCL research, transformers can be trained to predict clinical outcomes by learning the high-dimensional relationships between genetic alterations, transcriptomic profiles, and patient responses to therapy. Such models could also be fine-tuned to stratify patients into molecular subtypes with greater precision, thereby facilitating the development of subtype-specific treatments [76]. Moreover, transformer models can facilitate the integration of spatial multi-omics data, which combines molecular profiling with spatial information, providing insights into the tumor microenvironment and its role in lymphomagenesis. By doing so, researchers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of DLBCL, leading to the identification of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets [77].

Many statistical considerations and practices must be addressed when applying AI techniques, including ML and transformer models, to biomedical research and analysis of multi-omics data in DLBCL. It is important to appreciate that the specific implementation of statistical tests, the validated assumptions, the p-values, and the correction for multiple testing may differ depending on the ML algorithms, programming libraries, and software tools used in DLBCL research. Therefore, DLBCL research must include proper statistical approaches and guidelines for robust and reproducible multi-omics data analysis.

In multi-omics, AI algorithms are applied to synthesize and interpret data across genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic layers. Deep learning, an advanced ML technique characterized by the use of neural networks with multiple layers, has proven particularly adept at handling the non-linear and high-dimensional nature of multi-omics data. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are a particular type of feedforward neural network and have been shown to be quite successful in interpreting DNA sequences [78]. Convolutional layers in CNNs process input data to extract local features of input data and identify patterns. CNNs can also be used to analyze genomic data (e.g., DNA sequences) to discover significant genomic regions, regulatory elements, or sequence motifs associated with the progression of the disease or specific molecular subtypes in DLBCL research [79]. In contrast, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) appear well-suited for capturing the inherent sequential information present in transcriptomic data [80]. RNNs are meant to deal with sequence data introduction of feedback connections that store information from previous inputs. Thus, they are ideal for uncovering patterns in time series or longitudinal data (e.g., gene expression profiles at different stages of DLBCL progression or treatment response) [81]. The model can learn dynamic gene expression patterns, regulatory networks, or disease outcome prediction, as RNNs can capture temporal dependencies within the data [82].

The utilization of AI in oncology currently faces a pivotal challenge, as the prevalent single-modality approach needs to harness the comprehensive clinical landscape richly detailed by the array of patient data available. To elevate the precision and dependability of AI-driven diagnostic and prognostic models—and to facilitate their integration into clinical practice—it is imperative that we amalgamate disparate data modalities. These include, but are not limited to, radiology, histology, genomics, and electronic health records. The strategic integration of such multimodal data enhances model performance and positions AI to reveal intricate patterns that traverse these modalities. These patterns may prove crucial in elucidating the heterogeneity in patient outcomes and treatment resistance. Discoveries precipitated by such an integrated AI approach hold the promise of propelling investigative studies and fostering the emergence of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Moreover, the application of AI methods in multimodal data fusion—and the pursuit of strategies to render AI models interpretable and exploratory—will be instrumental in addressing the existing challenges and catalyzing the clinical adoption of AI in oncology [83].

AI facilitates multi-omics data integration by aligning disparate data types onto a unified analytical framework. This process is critical, given that different -omics data can have varying scales, distributions, and levels of noise. AI-powered integration strategies enhance the ability to uncover meaningful biological insights that would be obscured if each data type were analyzed in isolation [84].

Regarding analysis, AI algorithms are adept at sifting through the noise to identify signals of biological relevance. For instance, feature selection techniques reduce dimensionality and improve model interpretability by isolating the most informative attributes from complex datasets.

Visualization is another area where AI contributes significantly. Techniques such as t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) employ ML to reduce the dimensionality of data for visualization, enabling researchers to discern patterns and clusters within multi-omics datasets [85].

The advent of predictive modeling through AI has opened new horizons in managing and treating DLBCL. AI’s capacity to integrate and analyze complex multi-omics data allows for the generation of prediction models that can forecast disease trajectory, evaluate patient outcomes, and predict individual responses to various therapeutic interventions [86].

The power of AI in this context lies in its ability to sift through extensive datasets, identifying patterns and biomarkers that might otherwise elude human analysis. Such biomarkers are essential tools for patient stratification, enabling clinicians to categorize individuals into distinct groups based on their risk profiles or anticipated responsiveness to specific treatments. This stratification is paramount, as it facilitates tailoring treatment regimens to individual patient needs, thereby enhancing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [87].

Furthermore, AI-driven predictive models can potentially revolutionize the clinical approach to DLBCL by providing a more nuanced understanding of the disease’s heterogeneous nature. By elucidating the underlying biological processes that drive DLBCL progression and response to treatment, AI can assist in designing personalized medicine strategies [88]. These strategies aim not only to improve survival rates but also to optimize the quality of life for patients by minimizing exposure to ineffective treatments and their associated toxicities.

Moreover, the prognostic precision offered by AI models is invaluable. Accurate prognostic assessments can inform clinical decision-making, leading to better resource allocation and patient counseling. As such, integrating AI into the clinical workflow for DLBCL can significantly enhance patient management, from diagnosis to survivorship [89].

To harness the full potential of predictive modeling in DLBCL, ongoing research and collaboration between computational scientists and clinical experts are essential. The continuous refinement of AI algorithms and the expansion of high-quality, annotated omics datasets will undoubtedly lead to improved model accuracy and reliability. As AI models become increasingly sophisticated and validated in clinical settings, they promise to become indispensable tools in the fight against DLBCL, ultimately leading to more informed, effective, and personalized patient care.

The recent progress in DLBCL driven by AI has been awe-inspiring. These accomplishments have changed research and medical practices, such as predicting prognosis, diagnosing, evaluating treatment responses, and classifying subtypes.

A notable advancement is the creation of the “contained model” (McPM) by Peng et al. [81]. This innovative model combines AI analysis of markers with information to predict overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in DLBCL patients. By surpassing models like the international prognostic index (IPI), the McPM has opened doors for personalized treatment approaches by integrating data into prognostic models.

AI-driven image analysis has made strides in assessing programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in patients [90]. These developments have enhanced the objectivity and clarity of PD-L1 measurement, thereby advancing targeted immunotherapy research for DLBCL. The introduction of a PD-L1 scoring system highlights how AI can precisely measure PD-L1 expressions, supporting immunotherapy advancements.

On the diagnosis front, deep learning-based diagnostic systems have achieved unprecedented diagnostic accuracy in DLBCL cases [91] by using convolutional neural networks and addressing image-to-image variation and data rarity challenges with pre-trained networks, data augmentation, regularization, and cross-validation. A consequent result is diagnostic accuracy of nearly 100%, which is instrumental in improving DLBCL diagnosis and patient management.

Moreover, deep learning and digital pathology have enabled the prediction of DLBCL treatment response [92]. Combining clinical data with pathology image features, multimodal prediction models have been able to predict relapse-free survival as well as identify histological features related to treatment response. This innovation supports the potential of AI-based diagnosis as a robust diagnostic and prognostic tool in DLBCL management.

It is possible to predict treatment responses using meticulous algorithms of convolutional neural networks and maximum intensity projection (MIP) images [93]. In less than two years, these AI networks have exceeded accuracy in predicting time-to-progression (TTP) over traditional models, including the established IPI. It allows clinicians to adapt treatment strategies at an early stage for these more at-risk patients in order to improve care.

AI networks have also helped categorize lymphomas. Specifically, interpretable AI methods such as LymphoML reach a diagnostic accuracy similar to pathologists on H&E-stained tissue [94]. Three dimensional (3D)—and AI-based approaches have had a major impact on morphologic boundary-breaking, texture, and architectural boundary-breaking. By integrating these features with immunostains, AI tools can help pathologists improve diagnostic accuracy and subtyping of lymphomas.

ML approaches to predict DLBCL molecular subtypes using gene expression data have significantly advanced in recent years [95]. Different models from ML methods have exhibited substantial accuracy for extracting subtypes in subtype classification, critically highlighting the importance of AI in this domain.

In summary, AI has revolutionized the way that DLBCL is currently challenged. These advances have been major in the context of prognosis prediction, diagnosis, treatment response evaluation, and subtyping. They have provided opportunities for improving patient outcomes in DLBCL through better molecular integration, more understandable prediction, and wider applicability given currently advanced AI techniques.

The evolution of AI in multi-omics necessitates the development of more sophisticated computational methods to integrate diverse -omics data types effectively. Novel integration approaches, such as deep integration, that leverage the representational learning abilities of deep learning architectures promise to capture the complex, non-linear relationships inherent to multi-omics data [96]. One emerging method uses variational autoencoders (VAEs) that can learn latent representations of data, potentially unveiling new biological insights that are not readily apparent from individual-omics layers [97].

High-resolution technologies, such as single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics, are expected to advance, enabling the understanding of DLBCL in unprecedented detail. Integrating AI with these technologies will facilitate the identification of cellular heterogeneity and microenvironmental influences on DLBCL pathogenesis [97]. Advances in imaging technologies, combined with AI-like convolutional neural networks, will enhance our ability to visualize and quantify the spatial arrangement of tumor cells and their microenvironments.

The prognostic and therapeutic landscapes of DLBCL are poised to benefit from the compilation of large-scale, well-annotated multi-omics datasets. Such datasets should encompass comprehensive genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles and clinical data such as treatment history and patient outcomes. Efforts like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have laid the groundwork for multi-omics data repositories, but DLBCL-specific initiatives are needed to address the heterogeneity of the disease [98]. These datasets will be invaluable for training AI models to uncover novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The path from bench to bedside for AI-enhanced multi-omics in DLBCL involves the translation of computational discoveries into clinical applications. AI algorithms must be validated in preclinical studies and clinical trials to assess their predictive power and clinical utility [99]. Additionally, integrating AI with electronic health records (EHRs) will facilitate real-time predictive analytics, potentially improving the management of DLBCL.

In the era of personalized medicine, treatments for DLBCL will increasingly be tailored to the molecular and spatial profiles of individual tumors. AI will play a critical role in interpreting these complex datasets, aiding in selecting targeted therapies and predicting treatment responses [100]. Furthermore, integrating spatial multi-omics will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the tumor microenvironment, thus enabling the identification of novel therapeutic windows and the development of more efficacious combination therapies [101].

Collectively, these future directions underscore the potential of AI-enhanced multi-omics to revolutionize our understanding and treatment of DLBCL, ultimately leading to more precise and effective clinical interventions. Continuous advancements in computational methods, high-resolution technologies, and the acquisition of large-scale multi-omics datasets will be the cornerstone of this transformative journey in cancer immunology.

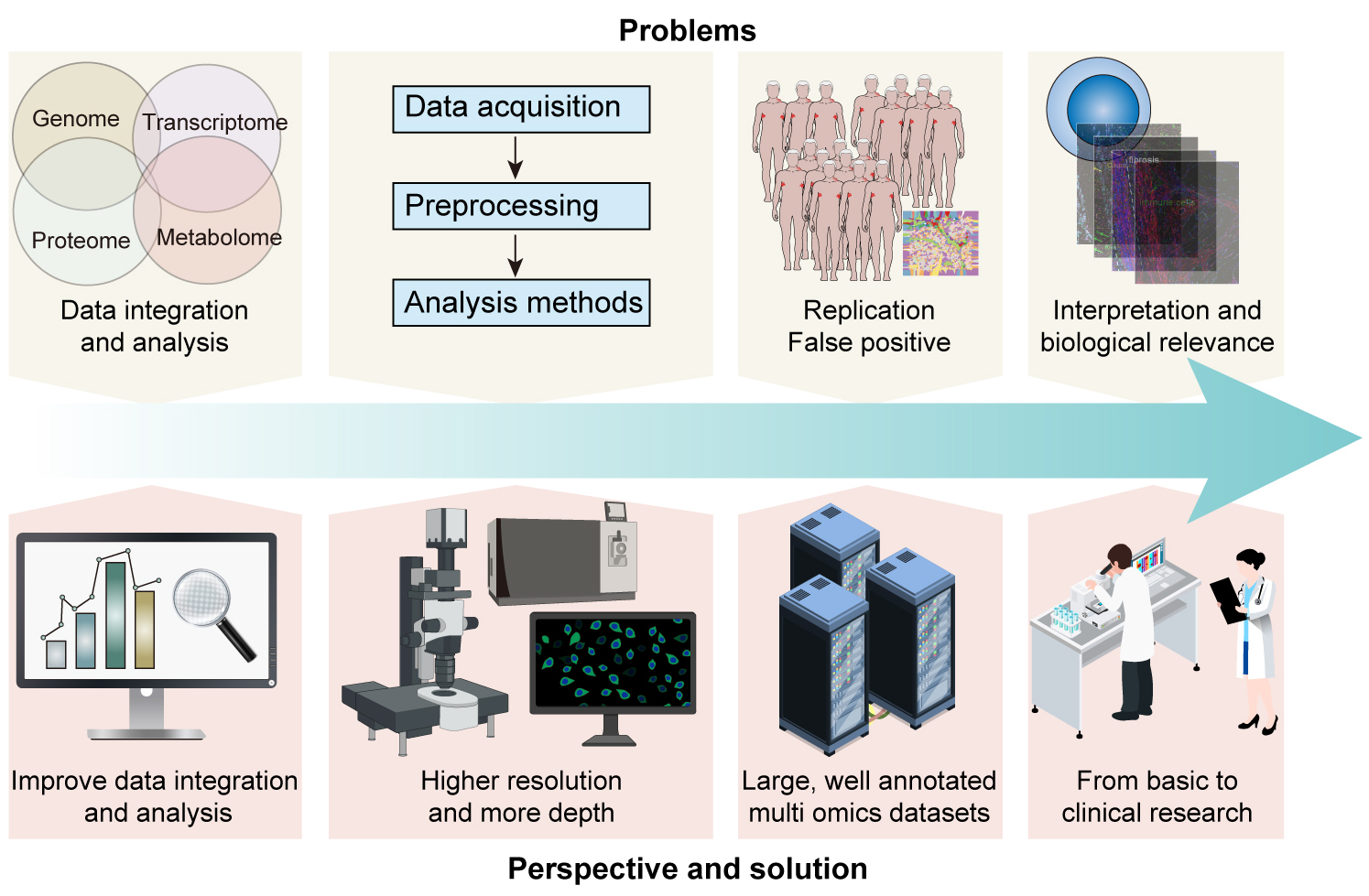

One of the key challenges in multi-omics studies is the integration of data from different omics platforms. When we provide data for each omics layer (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics), each comes with a large amount of data, and individual properties and difficulties [38]. Meeting the challenge: Computational methods and algorithms are being developed to provide robust data integration for analyzing multi-omics data [102, 103, 104, 105]. These methods intend to capture the inherent relationships and dependencies that exist among diverse omics layers and, in doing so, provide a more systems-level interpretation of the biological system being interrogated [102]. However, accurate and robust integration across this diversity of omics layers into the network view of the cell is a formidable challenge, as the data formats, measurement technologies, and noise levels across those omics layers are inevitably different [106]. In addition, the interpretation and validation of integrated multi-omics results pose additional hurdles [103]. Conclusion-Comprehensive biological validation: Studies that perform biological validation of findings across multiple omics layers are essential but must be carefully designed and executed. Moreover, the integration of multi-omics data is typically reductionist in practice, requiring considerable approximations and assumptions that could compromise the accuracy and robustness of the outcome.

Batch effects, the non-biological variations that occur due to differences in experimental conditions, pose a significant challenge to multi-omics studies [107]. These effects can confound the interpretation of results and affect the reproducibility of the studies. Therefore, proper experimental design and normalization techniques are necessary to mitigate these effects.

For spatial multi-omics, one of the primary technical challenges is maintaining the spatial resolution while obtaining omics data [22]. While methods like spatial transcriptomics provide spatial context, they are often limited by their resolution. Additionally, linking the spatial distribution of different omics layers (like mRNA and proteins) is currently a challenge due to limitations in technological capabilities.

Interpreting the results from spatial multi-omics studies can also be challenging. Understanding how the spatial organization of different molecular features correlates with biological function and disease progression requires sophisticated computational tools and a deep understanding of the biology [65]. Developing new analytical methods and visualization tools that can handle spatially resolved multi-omics data is an active area of research.

One of the major challenges in multi-omics and spatial multi-omics is the integration and analysis of high-dimensional data from different omics layers [38]. Each layer (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) generates a massive amount of data with unique characteristics, and integrating these data in a biologically meaningful way poses a significant computational challenge.

Multi-omics data is high dimensional data, which results in an increased complexity of analysis and interpretation. In addition, interoperability of multi-omics and spatial omics data relies on specific computational tools [108]. On the other hand, spatial omics, e.g., spatial transcriptomics or imaging mass cytometry, deliver information on the spatial distributions of molecularly distinct profiles within tissues or cells. However, with the integration of these spatially-resolved datasets with multi-omics data, the computational analysis composes a more complicated problem [108]. Identifying crucial patterns and correlations within the data of high-dimensional multi-omics is another challenge. As many factors are involved, it becomes more difficult to separate actual biological signals from noise [109].

Various computational methods to address the computational challenges in multi-omic and spatial multi-omics analyses — dimensionality reduction approaches, network-based analysis methods, and state-of-the-art ML algorithms — are being actively investigated by researchers [108, 110]. Such approaches are designed to reduce the dimensionality, select relevant points, and extract biologically informative data from high-dimensional data.

Another area for improvement in the field is the need for more standardization in data acquisition, preprocessing, and analysis methods. Different labs may use different protocols, which could result in inconsistencies when comparing results from different studies [107]. Efforts are ongoing to establish standardized protocols and best practices, but this remains a significant hurdle for the field.

Another important issue is the reproducibility of findings from multi-omics and spatial multi-omics studies. Given the complexity and high dimensionality of the data, false positives can be a problem [111]. Therefore, rigorous validation of findings, both computationally and experimentally, is necessary to ensure the robustness of the results.

Finally, interpreting the results from multi-omics and spatial multi-omics studies can be challenging. It is not always clear how the observed molecular and spatial patterns correlate with biological function and disease phenotypes [103]. Further biological experiments are often required to validate and explore the biological relevance of these findings (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Overcoming challenges and shaping future directions in DLBCL: Leveraging multi-omics and spatial multi-omics for precision medicine. This figure illustrates the challenges of data integration, method standardization, reproducibility, and biological interpretation in DLBCL research. It further outlines future directions, including enhanced computational tools, advanced spatial multi-omics technologies, the creation of comprehensive omics databases, and translational applications. The central theme of DLBCL is visually anchored, with arrows indicating the flow from current challenges to future innovations.

Despite the potential of AI in multi-omics, several challenges persist. One significant hurdle is the “black-box” nature of some AI algorithms, particularly deep learning, which can make the interpretation of results difficult for clinicians. Efforts are being made to improve the transparency and interpretability of AI models. Techniques such as model explainability and interpretability allow researchers to gain insights into the decision-making process of AI models. This can help identify and mitigate biases and ensure that AI models make fair and reliable predictions [112].

Another challenge is the need for large, well-annotated datasets to train AI models. Biases can arise from various sources, such as imbalances in the training data, human annotator biases, or systemic biases in the data collection process. If the training data does not represent the target population or contains inherent biases, the AI model may perpetuate or amplify these biases in its predictions and decisions. Techniques such as transfer learning, where a model trained on one task is repurposed for another related task, and data augmentation, which artificially expands the training dataset, are potential solutions to this challenge [113].

Lastly, ethical considerations must be addressed, particularly regarding patient privacy and data security. Ensuring the ethical use of AI in biomedical research requires adherence to established guidelines and ongoing dialogue between researchers, ethicists, and policymakers [114].

AI technologies can achieve important insights and assist in risk stratification, prognosis prediction, and subtype classification, but they have not transformed the DLBCL diagnosis and treatment landscape.

One of the primary limitations is the complexity and heterogeneity of DLBCL [115, 116]. This hematological malignancy shows high inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity, thereby hampering an accurate diagnosis and therapy. Significant heterogeneity is found within DLBCL, describing the disease as several molecular subtypes with apparent differences in clinical behavior and requiring different treatment modalities [117]. Even though AI models may help find subtypes and predict outcomes, translating these findings into personalized treatment decisions is difficult.

DLBCL diagnosis requires multiple time-consuming diagnostic modalities, such as histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and genetic testing [118]. It is notoriously difficult to integrate those diverse data sources and interpret the results cohesively. Although AI algorithms can help in data integration and exploration analysis, they have not yet had a large impact on enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of DLBCL diagnosis.

Treatment decision-making in DLBCL is mainly driven by established protocols and clinical guidelines derived from large-scale clinical studies [118]. Although precision medicine has progressed tremendously, AI-based models have only recently been integrated into treatment planning. Treatment of DLBCL has been adapted to patient characteristics, disease stage, genetic markers and a vast number of predictors of response for different interventions [118]. Whilst AI models may provide support for treatment stratification and prediction, their implementation within routine clinical care and validation of their effectiveness is a recurring challenge.

To overcome these limitations, concerted efforts involving multidisciplinary collaborations between researchers, clinicians, and regulatory bodies are required. Longitudinal studies, prospective clinical trials, and the establishment of comprehensive databases are essential for generating high-quality data, validating AI models, and integrating them into clinical workflows.

In conclusion, AI is proving to be a catalyst for interpreting and applying multi-omics data in DLBCL research. By leveraging AI’s capabilities in data integration, analysis, and predictive modeling, researchers can advance the frontiers of personalized medicine for DLBCL. However, the challenges associated with AI, such as interpretability, data requirements, ethical considerations, and the complex nature of DLBCL, must be diligently navigated to realize AI’s transformative potential fully.

Despite the advent of multi-omics and spatial multi-omics, downstream challenges in integrating and analyzing high-dimensional data remain [38]. The complexity and interdependence of multi-omics data represent a significant clinical challenge critical in developing computational tools and statistical models. In light of this, it is necessary to create more advanced data integration tools, and the focus should be on creating easily usable tools that can deal with all the complexities of multi-omics datasets.

Existing spatial multi-omics technologies are restricted by resolution and the number of features that can be simultaneously measured [22]. Thus, a critical avenue for future research is to develop the technology to increase the resolution and the multi-omics depth. Improving these parameters allows researchers to get more accurate and in-depth information about the spatial structure and molecular interactions in the biological states.

Most diseases need more large, well-annotated multi-omics datasets that are publicly available [103]. These datasets are precious resources used to develop and test new computational tools and better understand disease. Therefore, there is a need to focus on creating and disseminating complete multi-omics data to promote discovery and help make considerable progress toward a better comprehension of complex diseases.

Although multi-omics and spatial multi-omics have considerable benefits in discovering new biology and diseases, using these data to transform clinical care is a significant challenge [119]. Future research needs to concentrate on how to apply these techniques to the prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of a myriad of disease forms (Fig. 3). In translating research findings to the clinic, the integration of multi-omics and spatial multi-omics can bring new knowledge and insights to personalized medicine, providing effective healthcare.

In conclusion, the review underscores the transformative potential of integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with multi-omics and spatial multi-omics technologies in the realm of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) research. Such sophisticated methodologies are being used by researchers in an attempt to make sense of the molecular complexities and spatial variability characteristic of DLBCL, thereby leading to improvements in diagnostic accuracy, individualized treatment strategies, and improved risk classification. While considering the challenges in data standardization, result interpretability, and generalizability, the synergy between AI and multi-omics can hopefully propel precision medicine in DLBCL. More sophisticated AI-driven frameworks are needed, and large multi-omics datasets should accumulate so that the laboratory findings can be translated into bedside practice in the new era of patient-centric oncology care for DLBCL treatment.

YS wrote the manuscript, edited the drafts, and conceptualized the figures. XL and SY searched the literature and created the charts, and wrote the original draft. QG designed the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.