1 Department of Translational Biomedicine and Neuroscience (DiBraiN), Section of Human Anatomy and Histology, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy

Abstract

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disease that can be classified as an epithelitis based on the immune-mediated attack directed specifically at epithelial cells. SS predominantly affects women, is characterized by the production of highly specific circulating autoantibodies, and the major targets are the salivary and lachrymal glands. Although a genetic predisposition has been amply demonstrated for SS, the etiology remains unclear. The recent integration of epigenetic data relating to autoimmune diseases opens new therapeutic perspectives based on a better understanding of the molecular processes implicated. In the autoimmune field, non-coding RNA molecules (nc-RNA), which regulate gene expression by binding to mRNAs and could have a therapeutic value, have aroused great interest. The focus of this review is to summarize the biological functions of nc-RNAs in the pathogenesis of SS and decode molecular pathways implicated in the disease, in order to identify new therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

- Sjögren’s syndrome

- epigenetic

- nc-RNA

- miRNA

- long nc-RNA

- siRNA

The term “epigenetics” indicates heritable alterations in gene expression linked to predominantly environmental factors, which do not involve changes to the sequence of bases in DNA [1]. It is now clear from gene sequencing that genetic alterations alone cannot provide a comprehensive answer explaining the complex biological processes in autoimmune diseases. Consequently, epigenetic modifications are now being considered as key regulators of immune responses. In fact, epigenetic alterations underlie the pathogenesis of many autoimmune diseases, directly influencing the functions of immune cells [2]. Major epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, Histone acetylation and deacetylation, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNA), have been identified as regulators modulating gene expression and transcription in target tissues and organs [3]. Discovered in the early 21st century, ncRNAs, which do not code for proteins, could play an important role in human diseases. ncRNAs include small noncoding RNAs (sncRNAs) and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) [3]. The study of ncRNAs is now a thriving field of research but still, in part, unexplored, due to the lack of bioinformatic technologies capable of accurately evaluating their expression. In recent years, aberrant expression of ncRNA has been linked to the development of specific human diseases. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that many ncRNAs play key functions in the regulation of immune functions and, consequently, in immune-mediated diseases [3].

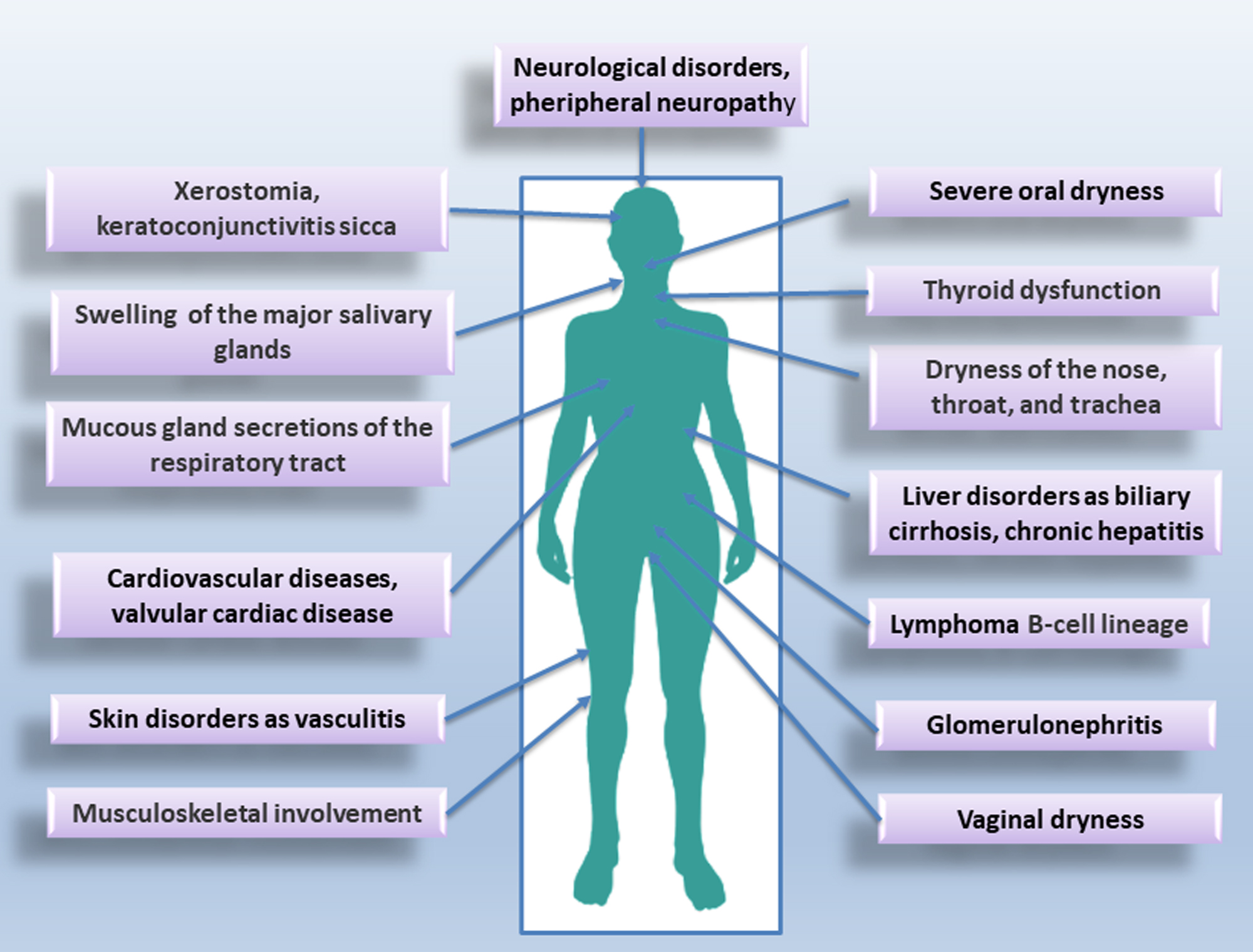

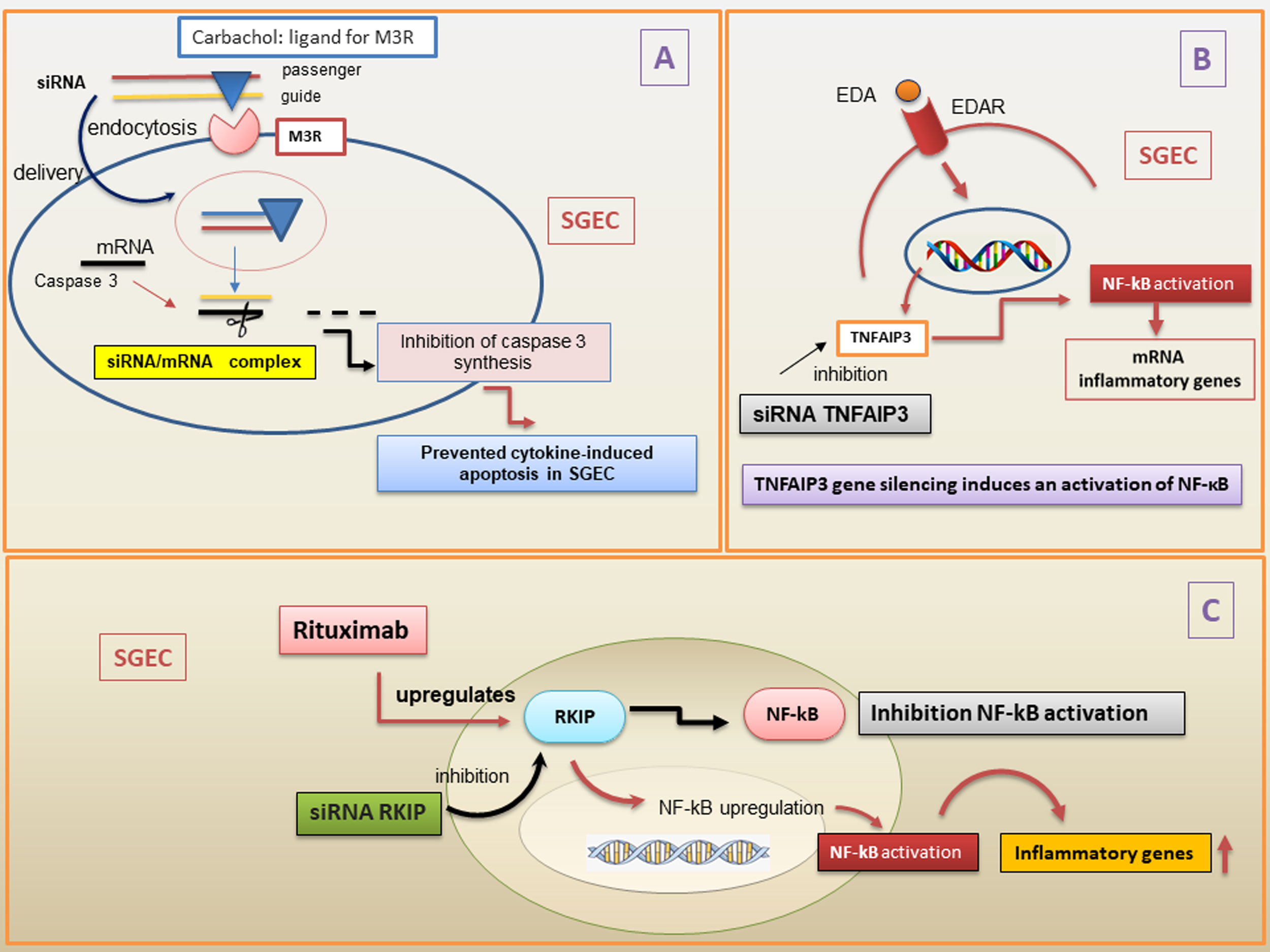

Sjӧgren’s syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune condition that is much more common in women than men. It mainly affects the epithelial cells of the lachrymal and salivary glands (SGs), which are characterized by focal and periepithelial T and B cell infiltration. Circulating autoantibodies, including anti-sicca syndrome type A (SSA/Ro) and type B (SSB/La) antibodies have been detected in SS patients [4, 5, 6]. SS is classified as primary (pSS) when it occurs alone, or as secondary (sSS) when associated with another autoimmune disease [7]. A diagram of the pathological picture associated with SS is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Typical glandular and extraglandular manifestations of Sjӧgren’s syndrome (SS).

SS is characterized by dryness of the eyes and mouth described as “xerophthalmia” and “xerostomia”; SS is characterized, in addition, by an increased risk of developing lymphoma [8] and by chronic inflammation that compromises the function of the affected organs. A genetic predisposition to SS has been widely demonstrated [9, 10]. In addition, other etiological causes of SS have been identified, such as environmental factors, exposure to chemicals, xenobiotics, and infectious agents [11]. To date, the genetic predisposition and/or the etiological factors mentioned do not fully justify the onset of the disease and the variability with which it evolves [9, 10, 11]. This has led scholars to hypothesize that epigenetic modifications could play a key role in the SS pathogenesis. Examples of DNA methylation in salivary gland epithelial cells (SGEC) and inflammatory cells derived from SS patients have been identified [12, 13]. Furthermore, the hypothesis of a probable correlation between epigenetic dysregulation in SS SGEC and the presence of infiltrating type B cells has been advanced; in addition, methylation alterations in SS have been correlated with the number of infiltrating lymphocytes and also with the amount of methylation/demethylation enzymes present in SS glands [14]. Moreover, most recent studies have demonstrated a decreased methylation of type I interferon (IFN) regulated genes both in SGECs and in SS immune cells [14, 15]. This review, after a summary related to the genetic susceptibility of SS, moves on to the most recent epigenetic discoveries related to the field of ncRNAs, highlighting the association between the ncRNAs expression and SS pathogenesis. A recent study has, in fact, put forward the hypothesis that some ncRNAs can function as biomarkers of SS, while others can play a direct role in the pathogenesis of the disease. This could help researchers open new perspectives in understanding the SS molecular characterization and could yield new insights into the development of novel therapeutic strategies [13].

Currently, it is clear that autoimmune diseases arise from a complex interplay among many polygenic risk factors and environmental influences. The etiology of pSS remains unclear, but evidence suggests that it develops in genetically susceptible individuals who have been exposed to unknown environmental conditions [16, 17, 18]. The identification and definition of the genetic risk of pSS is an essential key to characterizing molecular mechanisms underlying the disease pathogenesis and promoting the development of new therapeutic approaches to improve early diagnosis and treatment [17].

For several years, the genetics of pSS were widely underestimated as compared to those in other autoimmune conditions. Initially, the significant role of genetic factors in pSS was validated using data sourced from familial communities, including higher concordance rates among identical twins and an increased predominance of other autoimmune conditions among relatives of pSS patients [19].

Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), performed on pSS patients of European lineage, have identified 10 unknown genetic risk loci, and gene mapping and bio-informatic analyses have evidenced important implications that involve the expression of additional genes that can contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease [20].

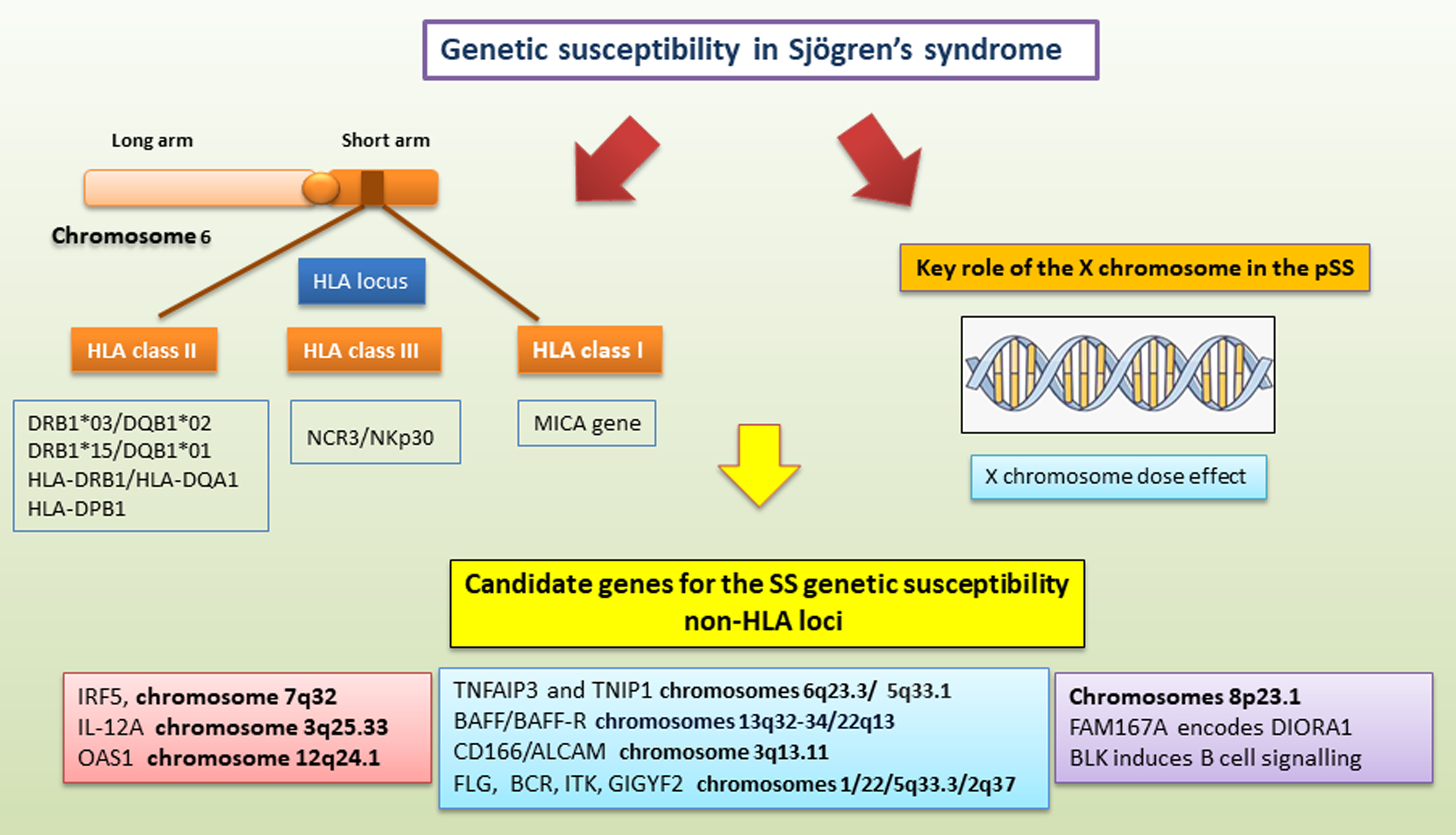

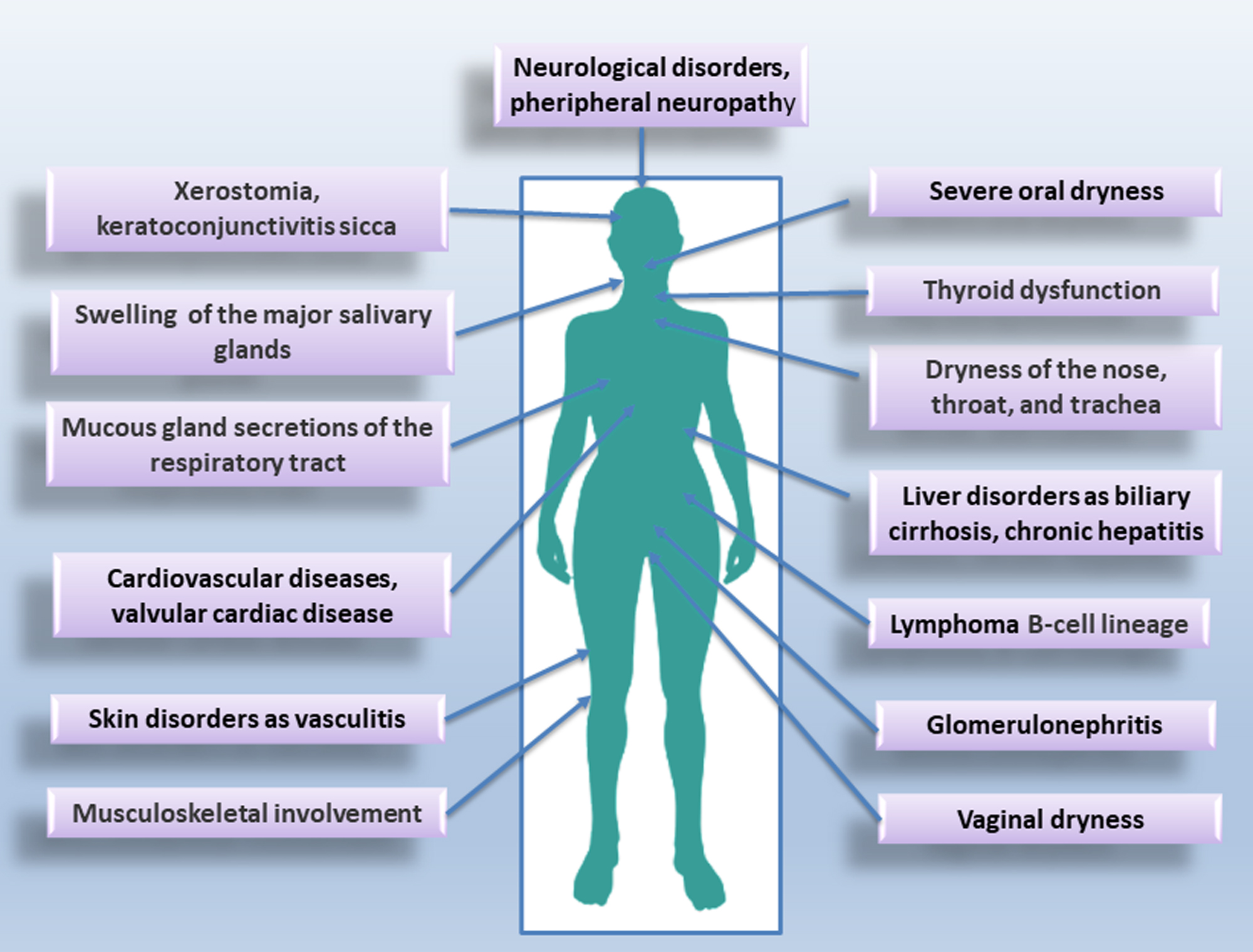

The strong influence of a genetic predisposition to pSS is referred to as the major histocompatibility (MHC) locus. MHC (also known in man as “Human Leukocyte Antigen”; HLA) genes are main drivers of a susceptibility to pSS, contributing to the development and manifestations of all autoimmune diseases [21]. A large number of variants associated with the pSS genetic predisposition are located within the HLA locus on chromosome 6 [17, 22]. In particular, individuals sharing haplotypes in the HLA-DQA_DQB_ region have the strongest genetic risk factors for pSS in different ethnic groups [23, 24]. These major histocompatibility haplotypes were presumed to result in an altered immune response linked to some environmental triggers. Laboratory investigations, as well as some indirect epidemiologic analyses, have demonstrated the involvement of viruses as environmental inductors, such as Epstein-Barr virus, human T-lymphotropic virus, hepatitis B virus, retrovirus, hepatitis C virus, and Coxsackie virus [25].

It is amply documented that pSS is associated with HLA class II types DR3 and DR2, in particular the DRB1*03/DQB1*02 and DRB1*15/DQB1*01 haplotypes, but only in patients whose serum contains autoantibodies against SSA/Ro and SSB/La antigens [26, 27, 28]. Actually, an important investigation corroborated the absence of HLA association in patients with pSS negative for SSA and/or SSB antibodies [29].

Interestingly, important recent studies conducted on a large sample of European pSS patients revealed an association with a haplotype at HLA-DQB1 and variants of a narrow region to HLA class II, within HLA-DQA1 [30, 31].

Furthermore, findings in GWAS performed in Chinese pSS patients demonstrated strong links with HLA-DRB1/HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DPB1 [28], while a low but significant association in the Asian subpopulation was found [28, 31].

Recent findings have identified, in the HLA region, a risk locus named MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA). The MICA gene is highly polymorphic, and it has been reported to have more than 100 MICA alleles that encode over 100 protein variants [32]. MICA is mainly expressed in epithelial cells, and was demonstrated to be a risk locus associated with pSS [22, 30]. Therefore, also in the class III region, TNF and, most recently, NCR3/NKp30 have been included among pSS risk factors [33, 34].

Several lines of evidence have analyzed the key role of the X chromosome in pSS. This syndrome occurs predominantly in women, and given the remarkable gender disparity, the X chromosome has been recognized as a specific, promising risk factor for genetic studies [35, 36]. An interesting study [36] evaluated an X chromosome dose effect in men affected by pSS and Klinefelter’s syndrome (47, XXY), demonstrating an analogous risk of pSS as in 46, XX women. Particularly, the coexistence of Turner syndrome (45, X) with pSS is infrequent, whereas the predicted predominance of pSS in women with 47, XXX is higher than that in women with 46, XX [37]. The identification of structural chromosomal alterations deriving from partial triplications of the X chromosome obsserved in three patients affected by pSS suggests that dosage-sensitive risk genes may be located within this chromosomal interval [38].

In the last few years, GWAS studies have analyzed candidate genes for SS genetic susceptibility, which also involve an abnormal regulation of innate immunity [29, 31]. This genetic predisposition involves genes such as IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), activator of transcription 4 (STAT4), interleukin-12A (IL-12A), and 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1), predominantly observed in pSS patients positive for anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB [31]. Indeed, studies have highlighted IRF5, a transcription factor implicated in IFN secretion, as a candidate gene for the genetic susceptibility to pSS [38, 39]. In particular, a significant association with a 5-bp (CGGGG) insertion/deletion polymorphism located in the promoter region of the IRF5 transcript has been demonstrated [39]. SS patients carrying the IRF5 allele had a high level of gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and salivary gland epithelial cells, and consequently had high levels of IFN secretion in PBMCs [39]. A key role of STAT4 in the genetic predisposition to pSS has been identified, being a transcription factor activated by type I IFN, IL-12, and IL-23, that is also linked to Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [40]. Furthermore, genetic models have discovered additive effects between IRF5 and STAT4 [41].

A transcriptome profiling study identified SS-associated variants of 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1), a type I IFN-induced gene that influences the expression of genes within the IFN pathway and is often demonstrated among the overexpressed genes in autoimmune conditions, such as pSS [42, 43]. At the protein level, the risk variant of OAS1 is linked with a diminished OAS1 enzymatic activity and increased susceptibility to viral infection, which is also associated with an increased risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [44].

Actually, genetic findings have discovered associations of the FAM167A-BLK locus with pSS in a study of Swedish and Norwegian patients and later re-examined in other European and Asian patients affected by pSS, demonstrating variants in a region included between these two genes, FAM167A and the BLK (B lymphocyte kinase), located at chromosome 8p23.1 [45]. BLK is implicated in B cell signaling, while FAM167A encodes a novel protein, DIORA-1, which is strongly expressed in the lung epithelium and has a key role in the pSS disease pathogenesis [45].

The importance of B cells is notable in pSS, as well as the presence of autoantibodies against Ro and La antigens, and consequently an increased risk of development of B-cell lymphomas [45].

In the last few years, disease susceptibility to anti-Ro/SSA- and anti-La/SSB-positive pSS has been linked with a variable haplotype associated to pSS-lymphoma. Lessard et al. [26] have identified a susceptibility locus in the coding region of CXCR5 on chromosome 11 and genetically linked to pSS [26]. Indeed, CXCR5 gene expression in B cells in salivary gland tissues of pSS patients is altered, featuring a decreased CXCR5 expression. Thus, decreased frequencies of CXCR5+ B cell subsets in peripheral blood and the recruitment of CXCR5+ cells in pSS may giving rise to ectopic lymphoid tissue assembly, posing an increased risk of lymphoma [46, 47].

Several studies have identified variants in TNFAIP3 and TNIP1 associated with a

genetic predisposition to pSS. TNIP1 binds TNFAIP3, which suppresses TLR-induced

apoptosis by negatively regulating NF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A schematic summary of genetic mechanisms linked to primary sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) predisposition. SS genetic susceptibility refers to (1) the HLA locus on human chromosome 6 located on the short arm of the chromosome from 6p21.1 to p21; (2) the X chromosome; and (3) candidate genes outside the HLA region. These candidate genes for SS genetic susceptibility involve both abnormal regulation of innate immunity and adaptive immune functions. ALCAM, activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; BLK, B lymphoid kinase; DIORA1, disordered autoimmunity 1; FAM167A, family with sequence similarity 167 member A; FLG, fillagrin; GIGYF2, GRB10 interacting GYF protein 2; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IRF5, IFN regulatory factor 5; ITK, tyrosine-protein kinase; NCR3/NKp30, natural cytotoxicity receptor 3/natural killer protein 30; MICA, MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A; OAS1, 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase 1; TNFAIP3, TNF alpha induced protein 3; TNIP1, TNFAIP3 interacting protein 1; IL-12A, interleukin-12A.

Genetic analyses have explored whether the BAFF gene is implicated in the pathogenesis of pSS, characterized by intensified fatigue levels, and investigated whether the BAFF/BAFF-R axis genetic variants could predispose to the development of fatigue among patients with pSS [50]. The authors have discovered a protective role of the BAFF gene variant against fatigue development in pSS patients. Interestingly, this genotype confers protection from fatigue independently of other contributing factors [50].

Genetic variants at loci CD5, CD6, coding for cell surface receptors implicated in the modulation of T and B lymphocyte activation were also demonstrated, and in CD166/ALCAM epithelial-immune cell adhesion (CD166/ALCAM), which regulates the clinical and analytical consequences in pSS patients [51].

Recently, an ample whole exome sequencing (WES) study identified novel susceptibility genes linked to pSS, locating pathogenic variants in FLG (gene encoding fillagrin), BCR (activator of RhoGEF and GTPase), and ITK (Grb10 interacting GYF protein 2), and one likely pathogenic variant in GIGYF2 (Grb10 interacting GYF protein 2) [52].

Finally, apart from the HLA genes, the effect sizes of the detected genetic associations are generally short, and the functional impact of analyzed genetic variants has, in most cases, not been clarified. Analysis of the interaction of the genetic risk loci with epigenetic alterations may increase our knowledge of pSS genetic risk factors (Fig. 2).

Epigenetic modifications offer a very fruitful field of research to attempt to explain how the interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental events can lead to the onset of chronic autoimmune conditions, including SS. Among the processes of epigenetic modulation, non-coding RNAs (including microRNA and long non-coding RNA) are a cluster of RNAs that do not encode functional proteins, but are considered regulatory RNAs. Since the publication of the central dogma of molecular biology [53], researchers have directed their efforts toward evaluating the transcription of DNA into mRNA and, consequently, the translation into proteins. The recent discovery that only a small portion of the genome has a coding value was therefore quite shocking [54]. The description of multiple kinds of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) has exponentially increased in the last few years, and it is now widely accepted that ncRNAs play major biological roles in cellular organization, function, and development and show an altered expression in a variety of diseases [55]. These ncRNAs have the capacity to modify protein levels through mechanisms independent of transcription [56], and the epigenetic modifications incurred by these ncRNAs were also shown to be transmittable. Today, SS appears to be a multifactorial disease, and the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of SS have so far been limited by our incomplete understanding of the molecular causes that drive this disease. The most recent research demonstrates that the regulation of ncRNA is related to the development and progression of SS [57, 58]. The next paragraphs will focus on the study of this topic and the latest discoveries in this field. The characterization of the ncRNA profiles in SS may be the key to the identification of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of the disease. In the following paragraphs, we collect the most recent discoveries relating to the role of ncRNAs in SS, focusing separately on microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNA molecules whose mechanism is to modulate gene expression post-transcriptionally through messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation or translational repression [59]. Among non-coding RNAs, miRNAs are the category that has been most closely studied. Since they play a crucial role in many regulatory functions, a change in their expression has a notable impact on the target molecules. The scenario is complicated by the fact that a single miRNA can act on multiple molecules, and a single gene can be regulated by multiple miRNAs. Many dysregulated miRNAs have been found in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), SGs, and saliva of SS patients.

The miRNA known to negatively regulate the inflammatory response that characterizes SS, carrying out a modulating activity in innate and adaptive immunity, is hsa-miR-146 [59]. The expression of hsa-miR-146a was analyzed in PBMCs from SS patients [60]. As well as demonstrating an upregulation of hsa-miR-146a in SS patients, the authors also showed that this miRNA is implicated in the upregulation of phagocytic activity and in a decreased release of inflammatory cytokines. These results led the authors to hypothesize that the activity of hsa-miR-146a is concentrated in the early stages of the disease. Confirming what was demonstrated by Pauley, other researchers found an upregulation of hsa-miR-146a in SS PBMCs [61, 62]. Investigators have studied both the expression of hsa-miR-146a and its targets IRAK1, IRAK4, and TRAF6 in the PBMCs of SS patients. Given the high expression of TRAF6 in SS patients, researchers have deduced its possible use as a distint marker for this condition [61]. Shi et al. [61], in addition, demonstrated a correlation between the overexpression of hsa-miR-146a and a scoring scale (VAS, visual analog scale) that serves to classify SS patients based on the degree of dry mouth, dry eyes, and swelling of the SGs [62]. Additional studies confirmed these data, observing a higher expression of miRNA-146a in patients affected with SS than in healthy controls in PBMC [62, 63]. Talotta et al. [64] detected a differential expression of miR-146a in CD4+ T cells from SS patients. Therefore, miR-146a are overexpressed in saliva collected from pSS patients, and, in addition, miR-146b levels are related with EULAR SS Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI) scores [65]. Shi et al. [61] detected a lower expression of miR-155 in patients with pSS, also demonstrating a correlation with the degree of dry eye. The situation, however, appears unclear, as Chen et al. [65] described a higher expression of both the miR-155 gene and the SOCS1 gene in PBMCs from patients with pSS [66]. Furthermore, not all scientists agree on an altered expression of miR-155 in SS, while this has been detected in SLE patients [67].

A study performed on the Chinese population by Peng et al. [67] found that 200 miRNAs were upregulated and other 200 miRNAs were downregulated in PBMC from patients with pSS. In particular, miRNA-let-7b, miRNA-142-3p, miRNA-142-5p, miRNA-146a, miRNA-148b, miRNA-155, miRNA-18b, miRNA-181a, miRNA-223, miRNA-23a, and miRNA-574-3p are regulatory molecules in immune processes. Among these, miR-181a is the one that shows a very different degree of expression between patients and healthy individuals. MiRNA-181a is only correlated with anti-nuclear antibodies, suggesting that PBMC miRNA-181a is an important biomarker to differentiate pSS from healthy patients, but cannot be used to discriminate between several disease phenotypes. Interestingly, they demonstrated that several virus-derived miRNAs dysregulated, supporting the hypothesis of a viral aetiology for SS [68]. To clarify the role of miRNA-181a in SS, Gourzi et al. [68] found a positively or negatively correlated expression of miR-181a, let7b, miR-16, miR-483-5p and miR-200b-3p with Ro52/Ro60 mRNA. On the contrary, there was a correlation between the expression of Let7b, miR-200b-5p and miR-233, and La/SSB-mRNA [69]. Furthermore, regarding the expression of miR-200b-5p, Kapsogeorgou et al. [69] added a very interesting fact, correlating the low expression of this miRNA with the possibility that pSS patients may develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). miR-200b-5p values could, therefore, represent an important predictive factor for the development of NHL [70].

More specific techniques have been used to evaluate the differential expression of miRNAs in B lymphocytes from SS patients, including the isolation of specific cell populations through the use of magnetic beads [64]. An inverse correlation was highlighted in CD19+ B lymphocytes between hsa-miR-30b expression and B-cell activating factor (BAFF) expression. This was confirmed by the fact that inhibiting hsa-miR-30b resulted in an increase in BAFF expression [64]. This discovery could clarify the role played by BAFF in SS, associated with the onset of an autoimmune response and the production of autoantibodies [71].

The role played by conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) in SS based on their interaction with CD4+ T cells has been considered [72]. Also at the level of these cells, an anomalous expression of miRNA was observed in SS, demonstrating a decreased expression of hsa-miR-130a and hsa-miR-708 [73]. In addition, the target gene for hsa-miR-130a, called MSK1, was also shown to be involved in the increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in SS. Some authors also evaluated whether interleukin (IL)-17 secretion was altered in SS by miRNA. IL-17 is a cytokine that has been widely implicated in the pathogenesis of SS [74, 75] and was shown to be modulated by hsa-let-7d-3p [76], which is underexpressed in SS and is inversely correlated with IL-17 expression. The list of miRNAs correlated with SS is becoming increasingly longer, and, in fact, hsa-miR-768-3p and hsa-miR-574 have also been correlated with the onset of the disease, and are now recognized to have a prognostic value for SS [77]. All this information is reported in Table 1 (Ref. [60, 66, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82]).

| miRNAs | Biological sources | Expression in Sjogren’s Syndrome | References |

| hsa-miR-146a | PBMCs, CD4+ T cells | Upregulated in PBMCs; upregulated in saliva | [60] |

| hsa-miR-155 | PBMCs, CD4+ T cells | Modulator of T-cell responses; upregulated in PBMCs | [66] |

| hsa-miRNA-181a | MSGs, SGECs, PBMC | Upregulated in minor SGs tissue, SGECs and PBMC | [69] |

| let7b, miR-16 and miR-483-5p, miR-200b-3p | SGECs, SGs, PBMCs | Upregulated in minor SGs tissue, SGECs and PBMC | [69] |

| miR-200b-5p | SGECs, SGs, PBMCs | Down regulation of miR-200b-5p in pSS patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | [70] |

| hsa-miR-30b | B cells | Expression is inversely correlated with the expression of BAFF | [71] |

| hsa-miR-130a, hsa-miR-708 | DCs | Deminished expression in dendritic cells | [72] |

| hsa-let-7d-3p | CD4+ T cells | Negatively linked with IL-17 expression | [73, 76] |

| hsa-miR-1248 | SGECs | Overexpression in SGEC lead to the activation of IFN- |

[78, 79] |

| hsa-miR-142 | SGs | Upregulated in SGs lesions and implicated in Ca2+ signaling | [79] |

| hsa-miR-1207-5p, hsa-miR- 4695-3p | SGs | Downregulated in SGs | [80] |

| hsa-miR-146a | SGs | Increased in saliva | [66] |

| hsa-miR-29a | SGs | Increased in SGs | [81] |

| hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-34a-5p, hsa-miR-142-3p, hsa-miR-223-3p | LGs | Upregulated in tears | [81] |

| hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p, hsa-miR-30d-5p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, hsa-miR-134-5p, hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-302d-5p, hsa-miR-365b-3p, hsa-miR-374c-5p, hsa-miR-487b-3p | LGs | Downregulated in tears | [81] |

| hsa-miR-744-5p | Primary human conjuctival epithelial cells (PHCEC) | Upregulated in PHCEC determines a decreased expression of PELI3, gene that regulates negatively inflammation | [82] |

miRNAs, microRNAs; MSGs, minor salivary glands; DCs, dendritic cells; LGs, lachrymal glands; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; SGs, salivary

glands; SGEC, salivary gland epithelial cells; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; IFN-

Some miRNAs have been correlated with the altered calcium metabolism observed in

SS patients. For example, hsa-miR-1248 has been demonstrated to play a double

role by modulating, on one hand, the production of IFN-

Since the lachrymal glands are the other organ predominantly affected in SS, other than SGs, some authors have decided to evaluate the differential expression of miRNA in the lachrymal glands of SS patients [81]. A comparison between tear samples from SS patients and healthy controls, demonstrated that several miRNAs were overexpressed (hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-34a-5p, hsa-miR-142-3p and hsa-miR-223-3p), and others were underexpressed (hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p, hsa-miR-30d-5p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, hsa-miR-134-5p, hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-302d-5p, hsa-miR-365b-3p, hsa-miR-374c-5p, and hsa-miR-487b-3p) [81].

Investigations conducted on the conjunctiva of SS patients have also yielded interesting results, demonstrating that hsa-miR-744-5p is overexpressed in SS, and this leads to a reduced expression of PELI3, a gene involved in inflammatory responses, and to a decrease in the chemokines CCL5 and CXCL10. This has led to hypothesizing a key role of hsa-miR-744 in the chronic inflammation that characterizes SS [82] (Table 1).

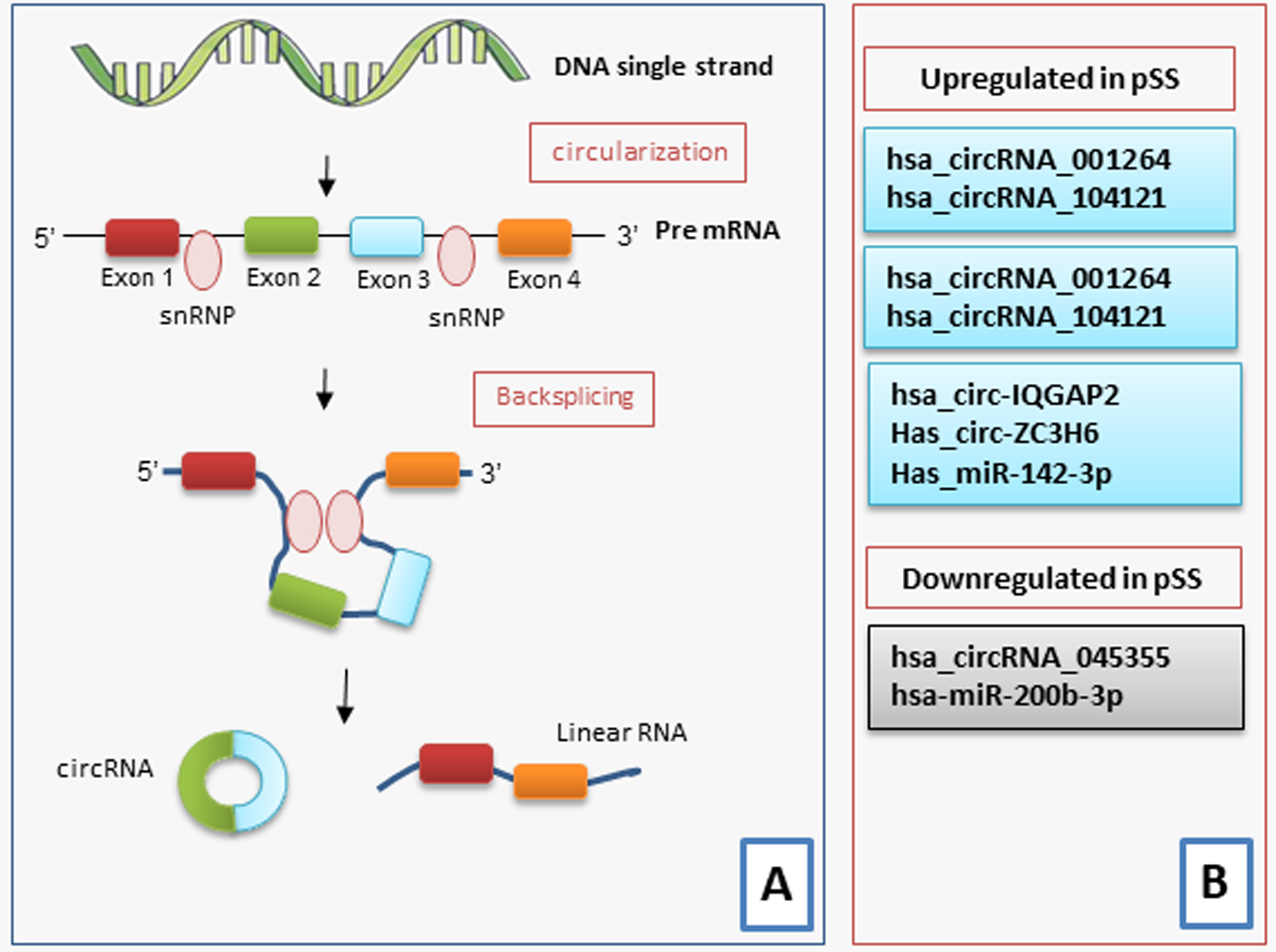

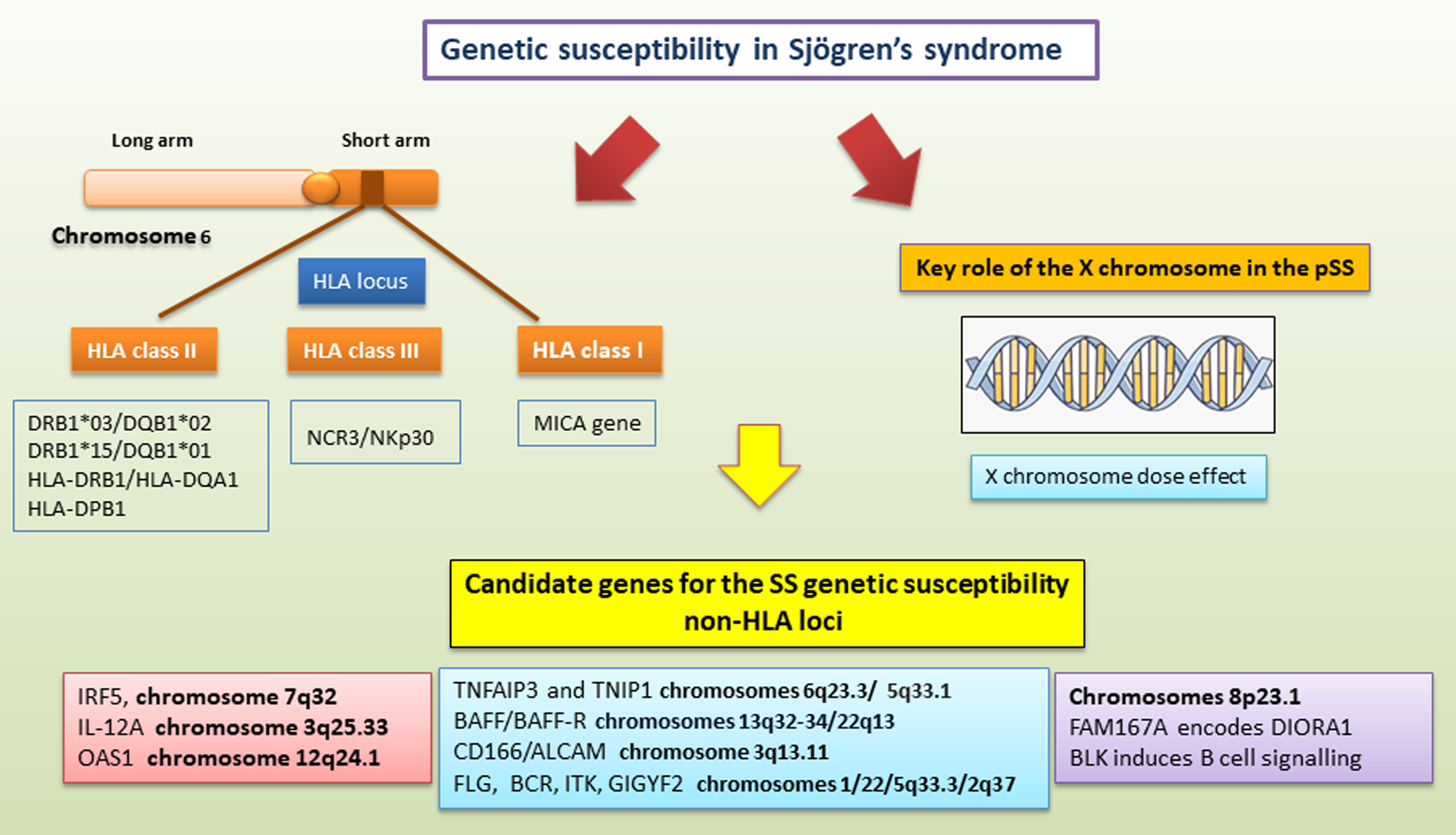

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are endogenous non-coding RNA that can be used as miRNA sponges with different miRNA binding sites and thereby change the functions of miRNAs [83]. Furthermore, circRNAs are constituted by a loop structure covalently closed, lacking 5′ to 3′ polarity or a polyadenylated tail, with an elevated stability and resistance to RNA exonucleases in the blood or plasma [84]. CircRNAs have been indicated to have central roles in modulating the expression of the genes both at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels [84] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

An illustration of the biogenesis and functions of circRNA in pSS. CircRNAs are synthesized from pre-mRNA. (A) Most circRNAs are produced from the back-splicing of exons, which results in the formation of a loop structure. The circularization depends on small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNP). CircRNAs function either by directly regulating the transcription of the gene, by serving as miRNA sponges, protein decoys or dynamic scaffolds, or translating regulatory peptides and regulation of epigenetic modification. (B) A scheme illustrating the various circRNAs that are either upregulated or downregulated in pSS.

Recent reports have begun to elucidate the abnormally expressed circRNAs in inflammatory autoimmune disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and multiple sclerosis (MS) [85, 86, 87]. Microarray analysis has identified hsa_circRNA_407176 and hsa_circRNA_001308 in the plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). These circRNA can act as novel biomarkers for SLE [85]. Furthermore, hsa_circRNA_003524 and hsa_circRNA_104871 have been detected in RA patients [86]. CircRNAs have also been used as potential biomarkers for MS [87].

The data relating to the altered expression of some circRNAs in SS are very recent, and the identification of circRNAs that may be considered biomarkers for pSS may improve the understanding of the complex pathogenesis of pSS. Su and colleagues [87] have recently identified 234 circRNAs that were differently expressed between pSS patients and healthy controls. Among these abnormally expressed circRNA, the mRNA expression of hsa_circRNA_001264 and hsa_circRNA_104121 was upregulated in pSS patients, and hsa_circRNA_045355 expression was diminished in pSS patients when compared to those in healthy individuals [88]. Interestingly, pSS patients with early disease showed a higher expression of hsa_circRNA_001264, and hsa_circRNA_104121 and downregulated expression of hsa_circRNA_045355 compared to those in patients with longer lasting disease. These circRNAs were related to renal involvement, arthritis, and laboratory data such as anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-SSA and anti-SSB [88].

More recently Li et al. [88, 89] have demonstrated that the use of circRNAs as biomarkers can contribute to the diagnosis of pSS through evaluation of the exosomes. Exosomes are small membrane-bound vesicles isolated from different biological fluids, including blood, milk, and urine [90]. Copious and stable circRNAs have been detected in exosomes, which play roles in cell-to-cell communication, transfer genetic information, modulate cell behaviors, and can be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis of several human diseases [85, 86, 87]. These authors first identified upregulated expression of circ-IQGAP2 and circ-ZC3H6 in the minor SGs (MSGs) and exosomes isolated from the plasma of pSS patients. However, no correlation was detected between the expression levels of these two circRNAs in MSGs and exosomes, although interestingly, the expressions of circ-IQGAP2 and circ-ZC3H6 were significantly correlated with serum IgG levels and the focus score [91].

It is now known that circRNAs can also have a reverse or non-transcription-dependent expression of linear transcripts [92]. Indeed, this study highlighted that the expression of circ-IQGAP2 and circ-ZC3H6 did not correspond to that of the IQGAP2 and ZC3H6 transcripts, which showed no differences between SS patients and healthy controls. In particular, the IQGAP2 gene, actively involved in mechanisms such as cell migration, cell proliferation and the inflammatory response [93], seems to be linked to a wide lymphocyte infiltration in SS SGs. Furthermore, ZC3H6 was demonstrated to be associated with the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [94]. The key role in SS is not yet clear, although evidence obtained in other disease conditions raises the hypothesis that these circRNAs could act by influencing the expression of their miRNA targets in SS [90]. A schematic representation of the most recent discoveries in this field is represented in Fig. 3.

Another group of non-coding RNAs are long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), recently acknowledged to play a regulatory role in the evolution of some autoimmune conditions [95]. LncRNAs are RNA transcripts with more than 200 nucleotides that do not encode proteins and are discovered in the nucleus or cytoplasm. They have been reported to play a crucial aspect in epigenetic regulation, transcription, and translation. Findings have highlighted that lncRNAs are implicated in several biological mechanisms such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and immune responses [96]. In particular, recent studies have reported their implication in the modulation of immune cell differentiation, activation, and immune responses. The biological role of lncRNAs remains uncertain, but it was shown that lncRNAs interact with other non-coding RNAs, such as miRNAs, acting as “miRNA-sponges”. The binding to miRNA prevents their modulation on the mRNAs [95, 96].

The activity of lncRNAs has also been shown to underlie the process known as X chromosome inactivation (XCI) [97], which is observed in females. The master regulator of XCI is the lncRNA XIST (NONHSAG054780.3) [97]. XIST works by binding to a genomic region on the X chromosome called the X inactivation center (XIC), and promotes binding to a series of inactivating proteins, determining gene silencing of the X chromosome [97]. The activation of XIST determines a profound remodeling of chromatin, which leads to the alteration of histone signals and the formation of H3K27me3-positive heterochromatin, known as Barr bodies [97, 98]. In SS, an asymmetric XCI was observed, representing an abnormal activation of the X chromosome in mesenchymal stromal cells. Simultaneously, a decrease in XIST levels was detected [98], resulting in altered chromatin reorganization in SS. Furthermore, some authors have demonstrated that the expression of XIST is regulated by miR-6891-5p [98], a miRNA encoded in the HLA locus, typically associated with the genetic predisposition to the onset of SS [21].

In addition, it has been demonstrated that during XCI, XIST interacts with a very large number of proteins to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that is active during silencing [48]. Among these proteins, which are subsequently degraded and exposed on the cell surface as antigens, the small RNA-binding exonuclease protection factor La (La/SSB) and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1 (HNRNPH1) [99] have been identified, two autoantigens characterizing SS patients [4, 5, 6]. This correlation could be further examined to elucidate the female predominance of SS [100].

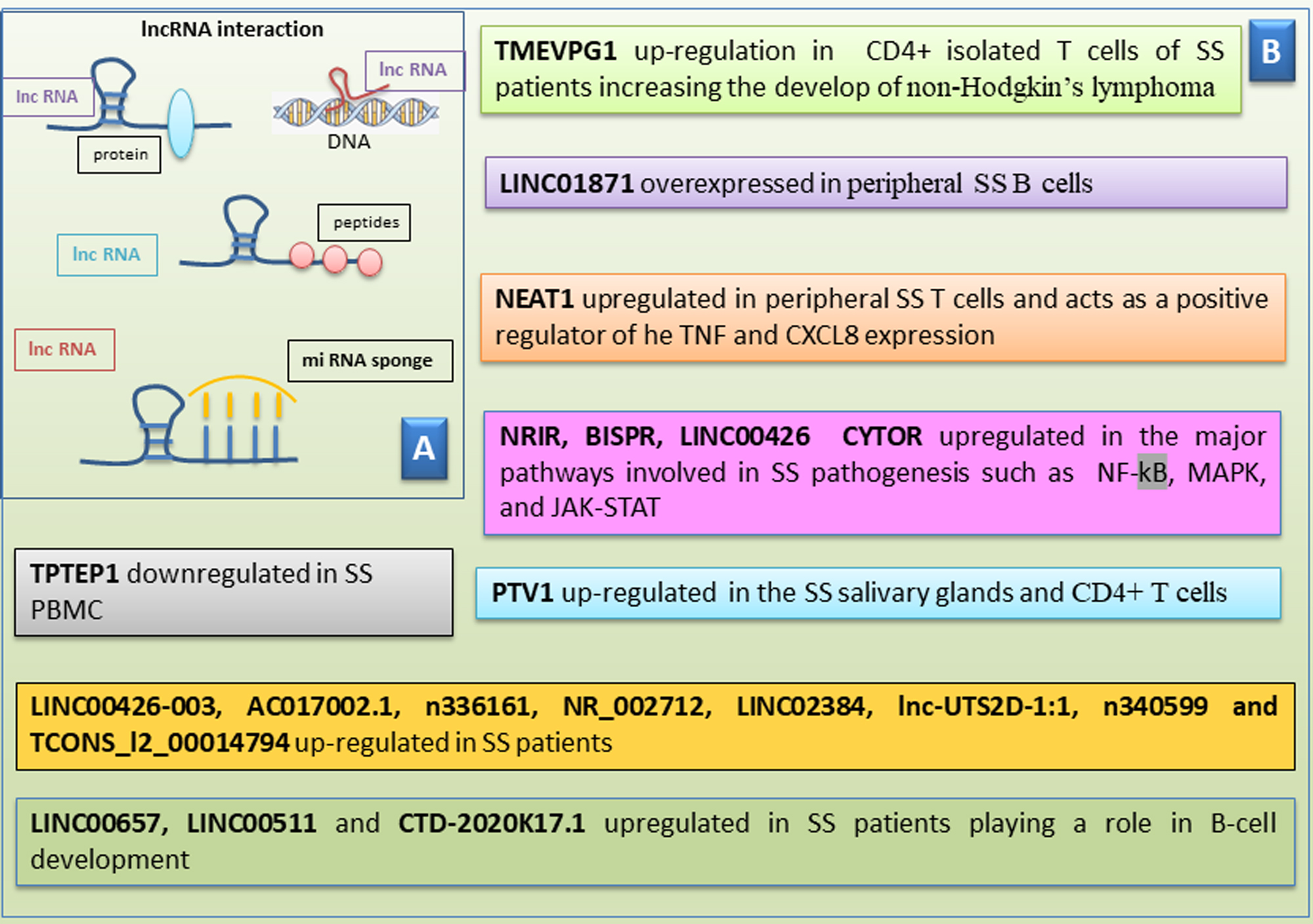

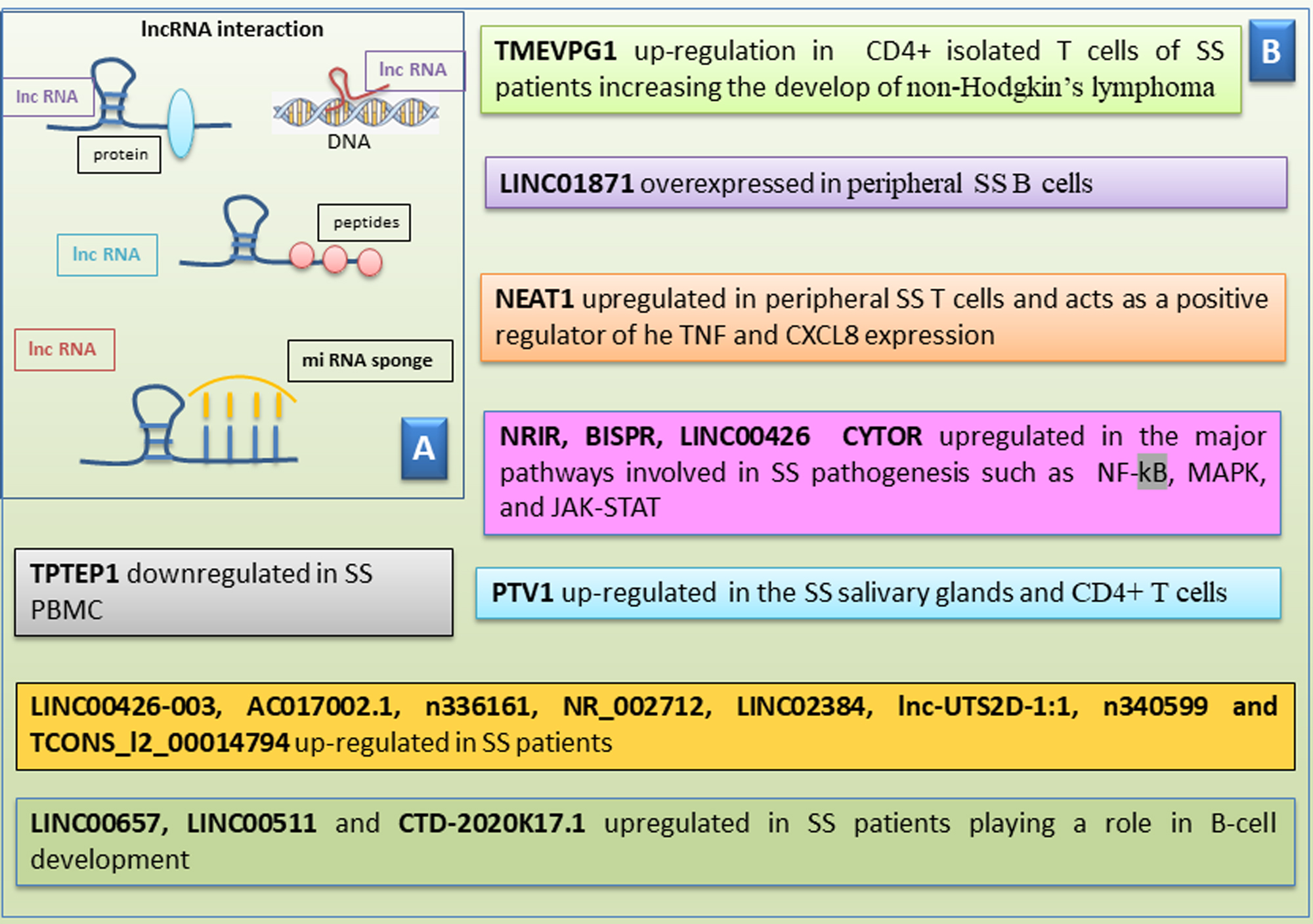

Research on the regulatory role of lncRNAs in SS has been very intense in the

last few years, and numerous interesting data have been obtained. LncRNA TMEVPG1

is encoded by a gene located near the IFN gene and is implicated in modulating

the production of interferon gamma (IFN-

More recently, lncRNA LINC00487 was demonstrated to be overexpressed in

peripheral B cells derived from SS patients, linked to IFN-

Another lncRNA correlated with SS is NEAT1, that has a crucial role in regulation of the immune response. NEAT1 is augmented in peripheral SS T cells and acts as a positive regulator of SS, modulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8 (CXCL8) expression, for example [106]. Interestingly, studies of the expression profile of lncRNA Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (PTV1), which is the most up-regulated lncRNA in the SS SGs, was performed [107, 108]. In particular, PTV1 expression was examined in isolated CD4+ T cells derived from PBMC samples of SS patients, demonstrating that PTV1 was significantly upregulated in these cells, inducing CD4+ T cells proliferation and activation. Therefore, PTV1 influences the expression of Myc, which is involved in the reorganization of glycolysis and is crucial for cell activity. PTV1 could be linked to the pathogenesis of SS, and indeed, the inhibition of glycolysis could diminish the disease evolution of SS [109].

A very broad investigation aimed at analyzing a panel of lncRNAs in SS also led

to the identification of overexpressed lncRNAs such as Negative Regulator Of Interferon Response (NRIR), BST2 Interferon Stimulated Positive Regulator (BISPR), Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNA 426 (LINC00426),

and cytoskeleton regulator RNA (CYTOR) and others that are downregulated, such as TPTEP1. The very

interesting finding that emerged from these investigations were the correlation between

these lncRNAs and the major pathways involved in SS pathogenesis, such as those

mediated by nuclear factor-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Scheme of human long non-coding RNAs in Sjӧgren’s

syndrome (SS). (A) Human long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) interact with

various biomolecules. LncRNAs can link to proteins, peptides, and DNA and also

act as sponges for microRNAs. (B) A list of lncRNAs that shows either

upregulation or downregulation in pSS. pSS, primary Sjӧgren’s Syndrome; NRIR, negative regulator Of interferon response; BISPR, BST2 interferon stimulated positive regulator; LINC00426, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 426; CYTOR, cytoskeleton regulator RNA; NF-

In addition, hopeful results emerged from the study of the interactions between lncRNA and miRNA in SS. In fact, a wide cohort of lncRNAs studied in SS patients, such as LINC00657, LINC00511, and CTD-2020K17.1, evidenced the very important fact that they regulate some miRNAs that play a role in B-cell development [110]. Several targeted genes with a high degree of connectivity were implicated with a severe inflammatory status, such as the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and the increase of IL-6 production or in the immune response, such as GATA3, which is crucial for T cell progression, and the three type I interferon-responsive-genes IRF5, IRF9, and KLHL20 [110].

Since the main target in SS is the SGs, emerging studies have explored abnormal expression of lncRNAs in SS SGs, demonstrating that the lncRNAs: LINC00426-003, AC017002.1, n336161, NR_002712, LINC02384, lnc-UTS2D-1:1, n340599, and TCONS_l2_00014794 are over-regulated in SS patients. Furthermore, as often happens, the abnormal expression of these lncRNAs was found to be linked with the course of the disease and its immunological findings [110, 111]. See Fig. 4 for an overview of the correlation between long-RNA and the SS pathogenesis.

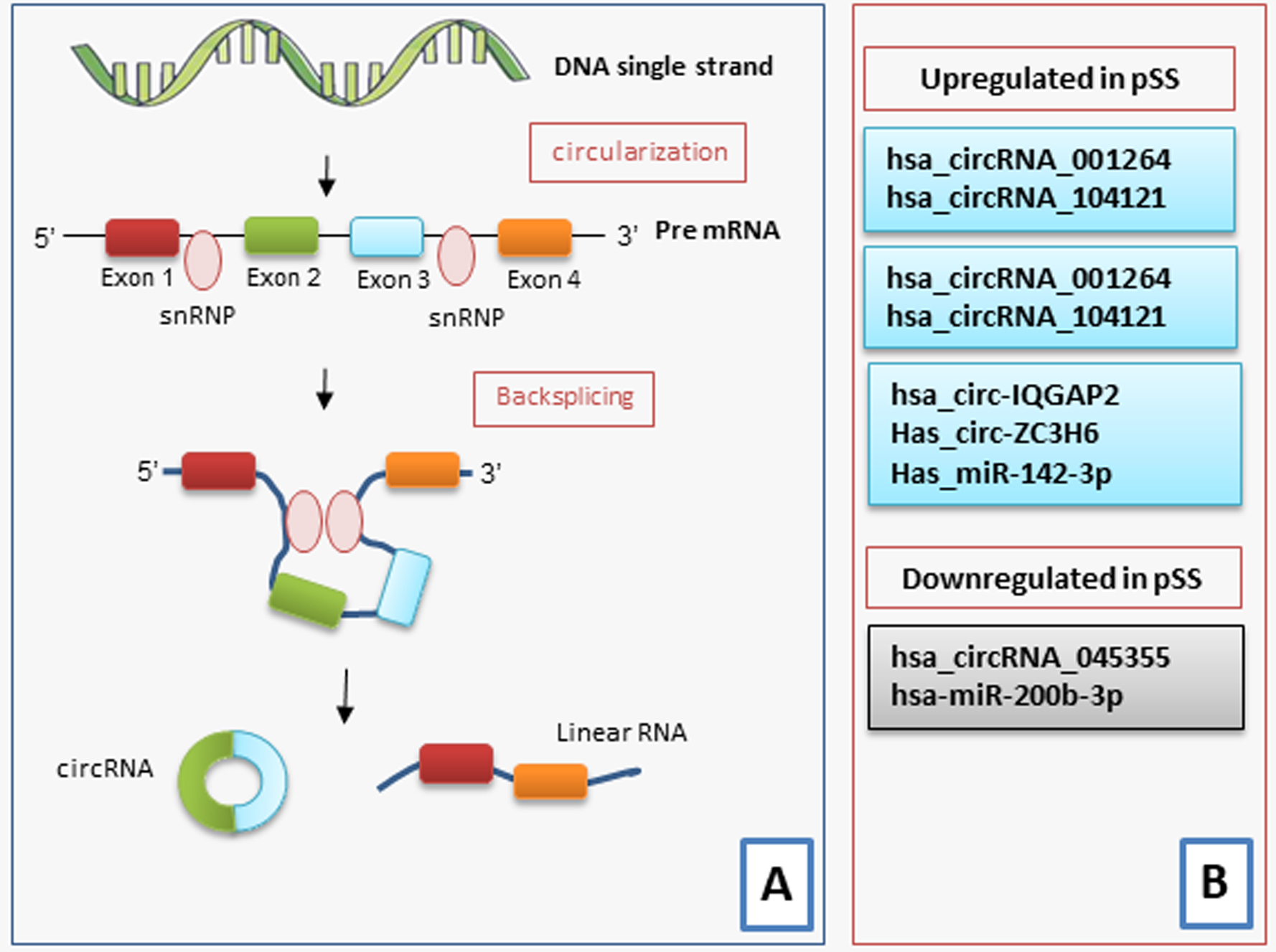

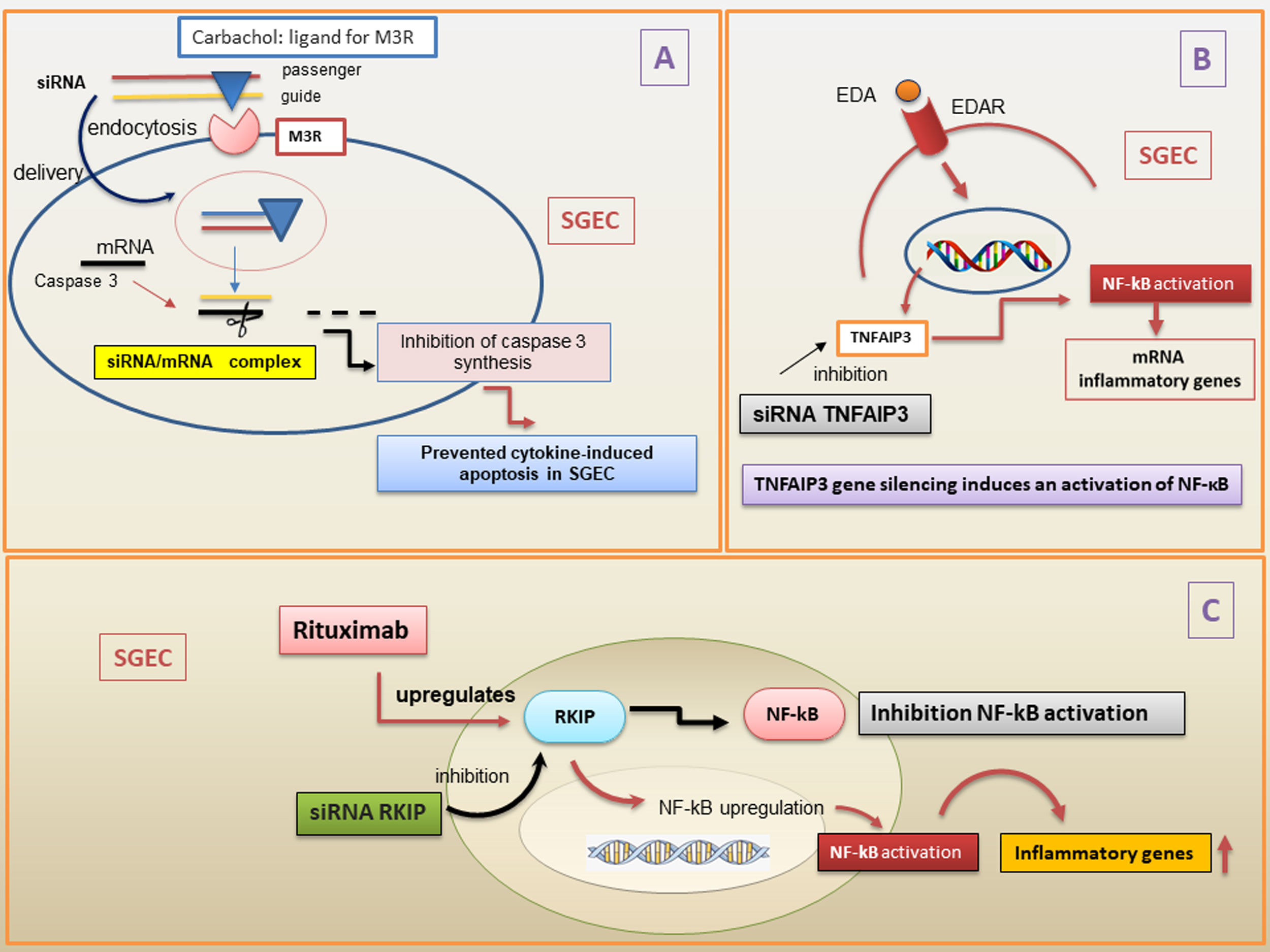

The chronic inflammatory response contributes to worsening the clinical picture in SS patients and consequently, many therapies have been aimed at achieving a regulation of the inflammatory state [112]. Among the future prospects, gene silencing could block or modulate the main molecular pathways underlying the evolution of SS disease. Gene knockdown therapies using siRNA have recently attracted great attention in the treatment of many immune-mediated diseases [113]. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are silencing RNAs (double-stranded non-coding RNA molecules) consisting of approximately 20–25 base pairs involved in gene silencing [114]. siRNAs offer a new and promising therapeutic possibility in autoimmune diseases based on epigenetics, which may lead to the inactivation of key genes involved in the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying these pathologies [115].

Various methods have been tested to stably introduce siRNAs into cells, for example, by inserting them into multiple promoter/shRNA structures, or tethered to long hairpin RNAs (hpRNAs) and miRNAs. Furthermore, siRNAs can be introduced into cells via viral vectors [116] or electroporation [117]. Currently, several limitations persist in the use of siRNAs for therapeutic purposes, linked to the low percentage of siRNA localization in target tissues, as well as unstable gene expression, and rapid removal from the bloodstream. This has led, in the last few years, to the identification of new siRNAs nanodelivery systems that seem to overcome many of these problems and offer a more promising therapeutic prospect in autoimmune diseases [118, 119]. The use of siRNA complexed with nanoparticles, which has been shown to give excellent results in several organs examined [120], was recently tested in epithelial cells of SGs, and Arany et al. [121, 122] demonstrated that novel pH-sensitive nanoparticles efficiently deliver and release functional siRNAs into cultured SGECs and in mouse submandibular glands in vivo (Fig. 5). There have been numerous attempts to introduce siRNAs into SGECs that adhered to the most realistic situation possible, including a very interesting study carried out by Pauley and colleagues [123]. Based on their expertise regarding the muscarinic type-3-receptor (M3R), the researchers utilized ligands specific to the muscarinic receptor to deliver siRNA into cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, thereby altering epithelial cell responses to external cues such as pro-inflammatory or death signals, while simultaneously stimulating secretion. During these experiments, in particular, siRNA targeting caspase-3 conjugated to the muscarinic receptors agonist carbachol can be delivered to cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, providing a novel approach for cell type-specific RNAi therapy to preserve epithelial cells and maintain secretory function in SS [123].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Overview of the siRNAs mechanisms in pSS. (A) siRNA conjugated

with carbachol, a ligand for M3R, is used to deliver siRNA into cells via

receptor-mediated endocytosis in the cytoplasm. The two strands of siRNA are

constituted by the guide and the passenger. Then, the passenger strand is removed

and degraded. When the complementary target mRNA caspase 3 has hybridized with

part of the guide strand, caspase 3 synthesis is inhibited, preventing

cytokines-induced apoptosis in SGEC. (B) TNFAIP3 gene silencing determines an

over-activation of EDA-A1/EDAR expression and NF-

Despite these very interesting advances, however, the use of siRNA as a

therapeutic strategy in SS is still in its infancy. Very encouraging discoveries,

however, have been made in terms of the molecular mechanisms underlying the SS

pathogenesis, using the gene silencing technique via siRNA. Recent data

demonstrated that gene silencing of the natural NF-

The importance of the NF-

It is now acknowledged that complex and intricate molecular processes are modulated by an enormous variability of ncRNAs. In the last few years, ncRNAs have become a ‘hot’ topic in genetics research, especially into the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. In recent years, interesting progress has been made in this field, also in the context of SS. A wide variety of recent studies [11, 12, 13] have identified differentially expressed ncRNAs in SS patients compared to healthy individuals or disease controls. The use of cutting-edge techniques in the IT field and gene sequencing have revealed a very complex scenario that seems difficult to understand in its entirety, also because the ncRNA itself seems to be able to carry out antagonistic actions depending on the molecular milieu. In SS, since the disease is predominantly linked to the female sex, it would be interesting to analyze and understand the role of mitochondrial ncRNAs, which could clarify many points that are still obscure. The observations collected in this review, which summarize the most recent discoveries about ncRNA-mediated regulation of molecular mechanisms identified in the pathogenesis of SS, could lead on to pioneering studies that could contribute to identify potential biomarkers aiding diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy.

MS and SL have contributed totally and equally to the conception and design of the paper. MS and SL were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and both authors approved the final version for publication. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Margherita Sisto and Sabrina Lisi are serving as two of the Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Margherita Sisto and Sabrina Lisi had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Agnieszka Paradowska-Gorycka.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.