1 Department of Life Sciences, School of Life and Health Sciences, University of Nicosia, 2417 Nicosia, Cyprus

Abstract

The Warburg effect, also known as ‘aerobic’ glycolysis, describes the preference of cancer cells to favor glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation for energy (adenosine triphosphate-ATP) production, despite having high amounts of oxygen and fully active mitochondria, a phenomenon first identified by Otto Warburg. This metabolic pathway is traditionally viewed as a hallmark of cancer, supporting rapid growth and proliferation by supplying energy and biosynthetic precursors. However, emerging research indicates that the Warburg effect is not just a strategy for cancer cells to proliferate at higher rates compared to normal cells; thus, it should not be considered an ‘enemy’ since it also plays complex roles in normal cellular functions and/or under stress conditions, prompting a reconsideration of its purely detrimental characterization. Moreover, this review highlights that distinguishing glycolysis as ‘aerobic’ and ‘anaerobic’ should not exist, as lactate is likely the final product of glycolysis, regardless of the presence of oxygen. Finally, this review explores the nuanced contributions of the Warburg effect beyond oncology, including its regulatory roles in various cellular environments and the potential effects on systemic physiological processes. By expanding our understanding of these mechanisms, we can uncover novel therapeutic strategies that target metabolic reprogramming, offering new avenues for treating cancer and other diseases characterized by metabolic dysregulation. This comprehensive reevaluation not only challenges traditional views but also enhances our understanding of cellular metabolism’s adaptability and its implications in health and disease.

Keywords

- Warburg effect

- cellular metabolism

- glycolysis

- cancer metabolism

- metabolic reprogramming

During a biochemistry course, I discussed that adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the energy currency of all types of cells [1]. Healthy adults at rest produce their body weight in ATP every day, and during maximal exercise, this number can increase to 0.5 to 1.0 kg per minute [2]. However, the human body contains less than 0.5 kg of ATP at any time [2], because it cannot be stored and is continuously recycled (from adenosine diphosphate, ADP) several times each day [2]. ATP is regenerated through two primary mechanisms: oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and substrate-level phosphorylation [3]. OXPHOS involves the conversion of ADP to ATP, harnessing energy from the oxidation of electron donors (e.g., nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NADH) in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. This process utilizes a proton motive force to generate ATP through an F-type ATP synthase [4]. In contrast, substrate-level phosphorylation occurs via the direct transfer of high-energy phosphoryl groups from high-energy compounds (such as phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) to ADP, producing ATP. This process takes place in the cytoplasm during glycolysis and within the mitochondria during the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [5].

I subsequently explained that in differentiated eukaryotic cells, carbohydrates,

which degrade into monosaccharides (such as glucose), remain the primary carbon

source for ATP production, despite the ability to use fatty acids and proteins as

alternative carbon sources [6]. The main stages of aerobic respiration include

glycolysis, the Krebs (or TCA) cycle, and OXPHOS, collectively generating

approximately 30 to 34 molecules of ATP [7]. On the other hand, fatty acids are

broken down into acetyl-CoA through

I then explained that the main advantage of sugars over fatty acids and proteins is that they produce ATP even in the absence of oxygen. For example, some cells, such as erythrocytes, which lack mitochondria, depend on ‘anaerobic’ glycolysis, a process similar to bacterial fermentation, for energy (ATP) production [11]. In this process, pyruvate, the final product of glycolysis, remains in the cytoplasm, where the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A), converts it into lactate while it also regenerates NADH to NAD+, a cofactor essential for sustaining the glycolytic reactions. Notably, ‘anaerobic’ glycolysis is significantly less efficient than OXPHOS, producing only 2 ATPs per molecule of glucose. This pathway, known as the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, developed before oxygen was abundant in Earth’s atmosphere [12].

One of my students inquired whether this pathway is also referred to as the ‘Warburg effect’. I explain that the Warburg effect, named after Otto Warburg, is observed in several cancer types that preferentially use glycolysis for energy production, even in the presence of sufficient oxygen. This process, known as ‘aerobic glycolysis’, is a hallmark of cancer cell metabolism [13, 14]. Similar to ‘anaerobic’ glycolysis, in the Warburg effect, LDH-A converts pyruvate to lactate, regenerating NAD+ for the continuation of glycolysis [15]. The student asked why we need to separate glycolysis into ‘aerobic’ and ‘anaerobic’ if both processes are similar.

The above suggests that there are prevalent misconceptions about anaerobic glycolysis/respiration, aerobic glycolysis/respiration and the Warburg effect. Notably, this confusion poses a significant educational challenge. Since oxygen does not participate in the process of glycolysis, the distinction between aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis is unnecessary. However, according to most biochemistry books, cells use glucose to regenerate ATP via aerobic and/or anaerobic respiration. During aerobic respiration (in the presence of oxygen), glycolysis concludes after ten enzymatic steps with the formation of pyruvate, which then enters the mitochondria for further processing in the TCA cycle. On the contrary, during ‘anaerobic’ respiration, glycolysis extends one step further to produce lactate [6]. Notably, over the years, lactate was considered merely a waste product of anaerobic metabolism, further supporting the distinction of glycolysis into ‘aerobic’ and ‘anaerobic’ processes.

Later that day, I was searching PubMed trying to address the above issue when I found the excellent opinion paper by Schurr [16] titled ‘How the ‘aerobic/anaerobic glycolysis’ meme formed a ‘habit of mind’ which impeded progress in the field of brain energy metabolism’, where the author states that the distinction between ‘anaerobic’ and ‘aerobic’ glycolysis persists among scientists, clinicians, and educators despite overwhelming evidence against such categorization. The author also highlights that glycolysis is a singular pathway and that pyruvate may not be the final product of glycolysis, even in normal cells. Importantly, lactate is probably produced at the end of glycolysis regardless of the presence of active mitochondria and sufficient amounts of oxygen [17].

Moreover, the perception of the ‘reverse Warburg effect’ has recently been introduced to explain the alterations in glucose metabolism in tumor cells [18]. According to this model, communication occurs between interstitial tissue and adjacent epithelium, where pyruvate is converted into lactate in the fibroblastic tumor stroma rather than in the epithelial cancer cells themselves. Epithelial cancer cells trigger the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) in nearby stromal fibroblasts, leading these fibroblasts to differentiate into myo-fibroblasts. As a result, these cancer-associated fibroblasts produce lactate and pyruvate as energy metabolites through aerobic glycolysis. The epithelial cancer cells absorb these energy-rich metabolites and utilize them in the mitochondrial TCA cycle, enhancing ATP production through OXPHOS which increases their proliferative capacity. In this alternative model of tumorigenesis, the epithelial cancer cells instruct the normal stroma to convert into a wound-healing stroma, creating an energy-dense microenvironment that promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis [19].

Thus, the fundamental questions that arose were whether the Warburg effect is exclusive to cancer cells, if lactate is indeed merely a metabolic byproduct, and whether a distinction between ‘aerobic’ and ‘anaerobic’ glycolysis should exist. In the past, it was assumed that the Warburg effect refers to the preference of cancer cells to produce energy via glycolysis even in the presence of sufficient oxygen, which differs from the traditional ‘anaerobic’ glycolysis seen in cells without mitochondria [20]. However, some cells, such as retina and immune cells, produce ATP using a process that resembles the Warburg effect; i.e., they convert pyruvate to lactate despite having fully active mitochondria and a sufficient amount of oxygen [21]. Moreover, erythrocytes lack mitochondria, but they have abundant oxygen. Thus, another question to be answered is whether erythrocytes utilize the ‘anaerobic’ or ‘aerobic’ glycolysis for ATP regeneration.

Inspired by my student’s questions and the insightful opinion paper by Schurr [16], this review explores the significance of the Warburg effect, examining how tumor cells adapt to their microenvironment and respond to oncogenic and tumor suppressor gene signaling. Moreover, this review highlights that the Warburg effect is not a privilege of cancer cells only and that normal cells may produce ATP mainly via glycolysis, despite having active mitochondria and abundant oxygen, a process similar to the Warburg effect. This review also contends that glycolysis is a singular pathway, with the key difference lying in the fate of pyruvate, which is considered the ‘end product’ of glycolysis. The fate of pyruvate determines the extent to which normal and cancer cells utilize the Warburg effect [22]. Finally, it discusses recent advancements in targeted therapies based on metabolic alterations observed in the Warburg effect. To avoid any further confusion in this review, ‘aerobic glycolysis’ will be referred to as the Warburg effect or Warburg-like glycolysis.

To understand the Warburg effect and its role in cancer and normal cell metabolism, I would like to begin with a brief overview of glucose metabolism. The human body utilizes various metabolic processes and carbon sources, including sugars, lipids, and amino acids, to produce ATP, adapting to the available metabolic conditions. As mentioned above, carbohydrates are the primary source of energy and their metabolism begins with the digestion of food in the gastrointestinal tract, followed by the absorption of carbohydrates as monosaccharides (sugars) by enterocytes. These monosaccharides (including glucose) are then transported to cells, where they are utilized for ATP synthesis, via the pathway of glycolysis, either in the presence or in the absence of oxygen [6].

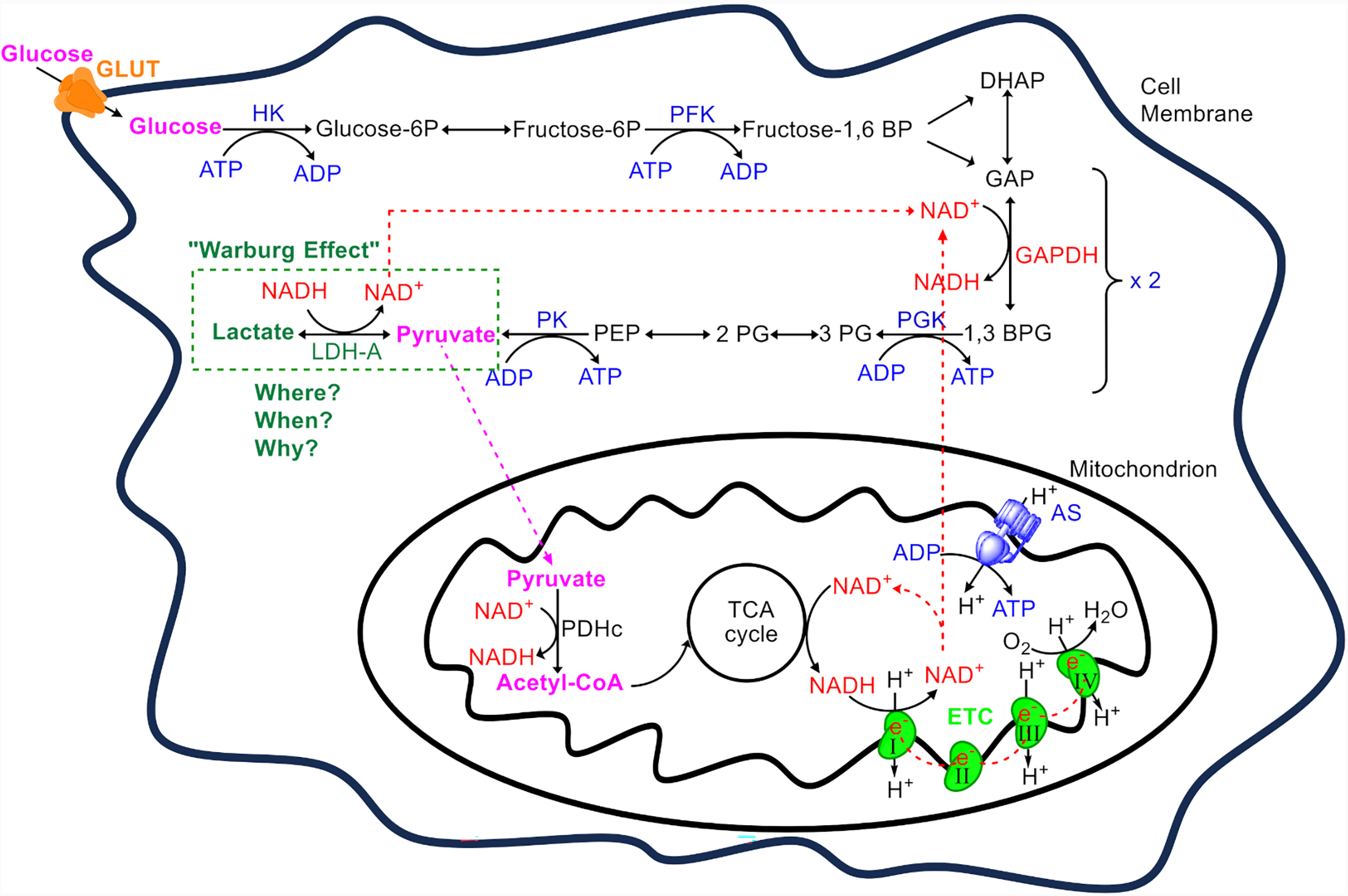

The pathway of glycolysis, comprises 10 enzyme-catalyzed reactions that divided into two phases: the preparatory phase, where hexokinase (HK) and phosphofructokinase (PFK) consume two ATP molecules, and the pay-off phase, where glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK), and pyruvate kinase (PK) collectively produce four ATP and two NADH molecules (Fig. 1). Thus, the net yield from glycolysis is two ATP molecules per glucose molecule. NADH production occurs at the GAPDH stage, the midpoint of glycolysis [23]. Importantly, the pathway of glycolysis does not involve or regulated directly by oxygen [6]. In the majority of normal differentiate cells, the two molecules of pyruvate enter the mitochondria, where they are converted into acetyl-CoA by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc). Acetyl-CoA then enters the Krebs cycle where more high-energy molecules (NADH and flavin adenine dinucleotide, FADH2) are produced, which then donate electrons to the electron transport chain (ETC) in the inner mitochondrial membrane, ultimately driving the production of the bulk of ATP through OXPHOS [7, 24]. Complete oxidation of glucose in the mitochondria yields 30–34 ATPs, while NADH is converted to NAD+ which is essential for the continuation of aerobic respiration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

An overview of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production from glucose. Glucose enters the cell via glucose transporters (GLUT) and is used as a primary substrate for ATP production. The metabolic process begins with glycolysis, which consists of 10 enzymatic steps. Initially, glucose undergoes glycolysis where hexokinase (HK) and phosphofructokinase (PFK) each consume one ATP to trap glucose in the cytoplasm and destabilize it. This results in the formation of two triose molecules, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP). DHAP is converted to GAP by the triose phosphate isomerase, allowing two GAP molecules to proceed to the payoff phase. Here, GAP dehydrogenase (GAPDH) converts GAP into 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3 BPG) while reducing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to NADH. The payoff phase yields four ATP molecules through substrate-level phosphorylation, catalyzed by phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and pyruvate kinase (PK). Thus, from one glucose molecule, two molecules of pyruvate, two ATPs, and two NADHs are produced. Pyruvate’s fate varies depending on the cell type, ATP demand, and other factors, as discussed within the text. In normal cells, usually pyruvate enters the mitochondrion, where it is converted to acetyl-CoA by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc). This acetyl-CoA enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), generating high-energy electrons transferred to the electron transport chain (ETC) via NADH and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) (not shown). Electron flow from complexes I (from NADH) and II (from FADH2) to complex IV in the ETC drives proton pumping from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space. Protons return to the matrix through ATP synthase (AS), driving the phosphorylation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to ATP in a process known as oxidative phosphorylation, while also regenerating NAD+ (from the oxidation of NADH) for use by NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases. In contrast, erythrocytes, which lack mitochondria, and certain cancer cells or normal cells under specific conditions, keep pyruvate in the cytosol where lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A), convert it to lactate, regenerating NAD+ for the continuation of glycolysis. This production of lactate from glucose even in the presence of oxygen is termed the ‘Warburg effect’. The reasons (when) specific normal cell in different organ (where) follow the Warburg effect (why) are extensively discussed within the text. Only the enzymes participating in the ATP/ADP cycle are shown (in blue). NADH, nicotinamide adenine din- ucleotide; PEP, Phosphoenolpyruvate.

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg discovered a distinctive metabolic phenomenon in cancer cells known as the Warburg effect, where these cells preferentially produce ATP through glycolysis (via substrate level phosphorylation) despite the presence of ample oxygen [25]. This process leads to increased glucose consumption and lactate production. Unlike most normal tissues, tumors exhibit a high rate of glucose fermentation to lactate, bypassing oxidation via respiratory pathways [26]. Although less efficient than OXPHOS, this pathway supports rapid ATP production, marking a key aspect of proliferative metabolism across many kingdoms of life [27]. The Warburg effect is evident in various tumor types, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and glioblastoma, which consume high amounts of glucose and primarily ferment it to lactate instead of oxidizing it [28].

Notably, certain cell types, such as erythrocytes lack mitochondria, and therefore convert pyruvate to lactate via LDH-A recycling NADH to NAD+ which is essential for the activity of GAPDH and the continuation of glycolysis a process similar to bacterial fermentation and the Warburg effect (Fig. 1). Interestingly, under specific conditions, normal cells (such as muscle cells, the brain, and retina) can sometimes utilize glycolysis to regenerate ATP and produce lactate even in the presence of sufficient oxygen and active mitochondria, a process similar to the Warburg effect [17].

However, following Warburg’s observations, the conversion of glucose to lactate in the presence of oxygen has been closely associated with cancer cells. Over the previous decades, the terms ‘aerobic glycolysis’ and ‘anaerobic glycolysis’ have been used to distinguish between lactate production in the presence of oxygen and lactate formation under low oxygen conditions, respectively. Notably, these distinctions are based on the various fates of pyruvate, which depend on cell type, external and internal signals, the cell’s energy status, and its developmental stage (discussed further below). Therefore, there is only one glycolytic pathway, and the terms ‘aerobic’ or ‘anaerobic’ glycolysis should not be overstated. Lactate can be the final product of this pathway regardless of oxygen presence, not only in cancer cells but also in normal cells [16, 17].

Historically, the Warburg effect was thought to be exclusive to cancer cells. Warburg’s observations were based on the fact that ATP can be derived from glucose through two primary pathways: fermentation and aerobic respiration [29]. Both pathways start with glycolysis, breaking down glucose into two molecules of pyruvate, yielding two ATP and two NADH molecules. In fermentation, NADH is used to convert pyruvate into lactate (via LDH-A), resulting in a net production of two ATPs and two lactate molecules per glucose molecule, typically occurring in the absence of oxygen. Conversely, in ‘aerobic’ respiration, NADH and pyruvate from glycolysis are transported to the mitochondria, where they participate in reactions that generate substantial amounts of ATP [29]. Furthermore, the ‘Pasteur effect’ indicates that low oxygen levels favor fermentation, while higher oxygen concentrations inhibit it, promoting aerobic respiration and reducing pyruvate conversion to lactate [30]. This mechanism supports efficient energy usage and carbon utilization for synthesis processes. When NADH is transported into the mitochondria and oxidized, it suppresses lactic acid production. However, during hypoxia, NADH cannot be oxidized via the respiratory chain, leading pyruvate to serve as a hydrogen acceptor, reducing to lactate [31].

Warburg discovered that, in contrast to normal tissues, cancer cells often convert glucose into lactate through ‘fermentation’ even when there is an adequate supply of oxygen [32]. This hypothesis received foundational support from the Nobel Prize-winning work of Hans Adolf Krebs on the TCA cycle, also known as the Krebs cycle. Krebs and his colleague Johnson [33] proposed that pyruvic acid (pyruvate), a product of glycolysis, combines with oxaloacetic acid to form citric acid. This marks a pivotal step in aerobic metabolism, where pyruvate enters the TCA cycle [33, 34]. It should be noted, however, that the TCA cycle was formulated three years before the glycolytic pathway, influencing the prevailing concepts regarding the roles of certain substrates and products of glycolysis [21]. This understanding led to the differentiation of glycolysis into ‘aerobic’ and ‘anaerobic’ forms. As also discussed above, a misconception that has influenced the distinction between aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis is the belief that lactate is merely a metabolic waste, leading to the erroneous view that pyruvate is beneficial while lactate is detrimental.

The precise molecular mechanisms initiating the Warburg effect in cancer remain elusive. Warburg initially posited that mitochondrial damage and dysfunction in the OXPHOS chain might trigger this preference for glycolysis, potentially causing cancer [35]. However, a subsequent study by Pedersen [36] revealed that cancer cells have functional mitochondria and sufficient oxygen, debunking Warburg’s initial theory. These findings suggest that the Warburg effect stems not from hypoxia but from metabolic reprogramming during early carcinogenesis. Such reprogramming includes the loss of tumor suppressor functions, altered signaling pathways, and oncogene activation, all of which foster cell proliferation and malignancy [37]. The prevalence of the Warburg effect in various cancers is influenced by factors including oncogene activation, tumor suppressor loss, mitochondrial DNA mutations, and the tissue of origin [38]. Furthermore, cancers are highly heterogeneous diseases, each with unique metabolic traits. Within even a single cancer type, cells exhibit a wide range of metabolic phenotypes [26].

A key feature of cancer cells is their altered metabolism, which significantly affects tumor growth, spread, and interaction with the tumor microenvironment (TME) [39]. While hypoxia contributes to cancer biology, cancer cells often exhibit glycolytic metabolism even in oxygen-rich environments, as seen in leukemic cells in the bloodstream and lung tumors during tumorigenesis. This indicates that tumor hypoxia, although significant, may not be the primary driver of the switch to the Warburg effect in cancer cells [37, 40]. Tumor suppressors like tumor protein 53 (p53) and oncogenes such as proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (SRC), protein kinase B (AKT), and RAS often influence key transcription factors like the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) and the oncogenic transcription factor MYC proto-oncogene BHLH transcription factor (MYC), which regulates many glycolytic enzymes through hypoxia-response elements (HRE) in their promoters [41]. HIF is typically degraded under normal oxygen conditions but stabilizes under hypoxia [42]. Additionally, gene mutations, TME remodeling, and interactions with the immune system all contribute to the Warburg effect, which involves heightened glycolysis over OXPHOS [43]. Moreover, mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes influence cancer metabolism by regulating metabolic enzyme activities—for example, MYC enhances glutamine uptake, and TP53 controls lipid metabolism [44].

The diversity in enzymes and transporters, including overexpressed LDH, particularly the LDH-A subunit with its high affinity for pyruvate, suggests potential new treatment strategies. LDH-A is linked to tumor progression, invasion, and drug resistance [39]. Despite functional mitochondria, many cancer cells ferment glucose into lactate rather than oxidizing it, possibly because of mitochondrial overload. This shift suggests that mitochondrial metabolism in cancer might increase to a point of saturation, promoting lactate release [45]. Abnormal levels of LDHs have been observed in various tumors, such as those found in pancreatic, breast, nasopharyngeal, gastric, bladder, and endometrial cancers (reviewed in [46]). Blocking LDH-A to inhibit the conversion of pyruvate to lactate reduces tumorigenicity and disrupts cancer cell metabolism without affecting normal tissue, highlighting glycolysis’s essential role in cancer energy production and offering a promising therapeutic avenue [47].

Notably, it is now recognized that the Warburg effect is not exclusive to tumor cells. Extensive research has shown that many non-tumor cells and tissues in conditions such as pulmonary hypertension, fibrosis, heart failure, atherosclerosis, and polycystic kidney disease also exhibit this metabolic pattern. Conditions like trauma, infection, or myocardial infarction induce aerobic glycolysis, leading to lactate production, even when oxygen is ample. This observation challenges the conventional dogma that in aerobic respiration glycolysis strictly ends with pyruvate entering the mitochondria for further energy production in the presence of oxygen [21].

Therefore, the short answer to the question ‘What is the Warburg effect?’ is that it refers to the phenomenon where glycolysis ends in lactate production and ATP is regenerated via substrate level phosphorylation even in the presence of sufficient oxygen and active mitochondria. This phenomenon is observed not only in specific types of cancer cells but also in normal cells. Before continuing with the discussion on the Warburg effect and examining when, where, and why ‘Warburg-like effects’ occur in normal cells, it is beneficial to clarify some potentially confusing terms related to glucose metabolism (Table 1).

| Term | Description |

| Glycolysis | The metabolic pathway that breaks down glucose into pyruvate, producing two molecules of ATP and NADH. It occurs in the cytoplasm and does not require oxygen. However, recent evidence suggests that lactate may be the final product of glycolysis. |

| Fermentation (Anaerobic glycolysis) | A form of glycolysis that occurs when oxygen is scarce or in cells lacking mitochondria, including microbes, leading to the conversion of pyruvate into lactate (or ethanol). This process allows for the regeneration of NAD+, enabling glycolysis to continue. |

| Aerobic respiration | Cells oxidase further pyruvate in the mitochondria through the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, yielding |

| Warburg effect | The observation that cancer and normal cells preferentially produce energy through glycolysis followed by lactate production in the cytoplasm, even in the presence of sufficient oxygen. ATP is regenerated via substrate level phosphorylation. |

As aforementioned, the Warburg effect, has been traditionally linked with cancer metabolism, however, this metabolic shift is not confined solely to cancer cells; it is also observed in various non-cancerous cells under certain physiological or pathological conditions. Moreover, Abdel-Haleem et al. [48] noted that the Warburg effect is prevalent in rapidly dividing cells under both normal and pathological conditions, prompted by a range of internal and external signals. These observations highlight the metabolic flexibility of cells to adapt to specific energy requirements and environmental stressors. Additionally, the principles and mechanisms of the Warburg effect are applicable across a diverse spectrum of cellular contexts, emphasizing the adaptive capacity of cellular metabolism [49]. Recent research on non-proliferating cells has significantly enhanced our understanding of metabolic pathways in differentiated tissues [32].

Nearly a century later, the use of the term ‘Warburg effect’ has broadened to encompass any instance where cells use glucose and produce lactate despite ample oxygen availability [21]. The Warburg effect extends beyond cancer, influencing various cell types involved in immunity, angiogenesis, pluripotency, and pathogen infections, such as malaria. This raises critical questions about the cellular mechanisms that determine whether glycolysis concludes with pyruvate or lactate, suggesting that lactate may be an inevitable end product of the glycolytic pathway, independent of oxygen and mitochondrial involvement. This insight fundamentally changes in viewing lactate solely as a waste product to recognizing its broader role in cellular metabolism under various physiological and pathological conditions [50]. Notably, it has been suggested that the metabolic fate of pyruvate is central to determining the extent to which cells utilize the Warburg effect [51] as discussed in the following paragraph.

As the end-product of glycolysis, pyruvate serves as a crucial juncture between glycolysis in the cytosol yielding lactate and TCA cycle in the mitochondria [52]. The transition of pyruvate into the TCA cycle is facilitated by the PDHc, which enables the entry of pyruvate carbons into the cycle. PDHc activity is negatively regulated by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs), viz. phosphorylation inactivates PDHc. Inhibiting PDK can suppress the Warburg effect, favoring the oxidation of glucose carbons in the TCA cycle over fermentation. Genetic suppression of PDKs has been demonstrated to decelerate the growth of cancer cells both in culture and in tumor models [53, 54]. Besides being converted into lactate or entering the mitochondrion for further oxidation, the two molecules of pyruvate produced during glycolysis can have different fates. Prochownik and Wang [22] recently reviewed the metabolic pathways of pyruvate, emphasizing that its fate is determined by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include cell type, redox state, ATP levels, metabolic demands, and the activity of other metabolic pathways. Extrinsic factors encompass extracellular oxygen levels, pH, and nutrient availability, all controlled by vascular supply. In this context, Table 2 (Ref. [22]) outlines six pathways that affect pyruvate content and utilization.

| Pathway | Function |

| The Lactate Dehydrogenase | Converts excess pyruvate into lactate or recycles lactate back into pyruvate for use as an energy source or biosynthetic substrate. |

| The Alanine | Synthesizes alanine and other amino acids. |

| The Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex | Generates acetyl-CoA, the starting substrate for the TCA cycle. |

| The Pyruvate Carboxylase Reaction | Anaplerotically supplies oxaloacetate. |

| The Malic Enzyme | Links glycolysis to the TCA cycle and produces NADPH to aid in lipid biosynthesis. |

| The Acetate Biosynthetic | Converts pyruvate directly to acetate. |

Regarding energy (ATP) production, pyruvate has two main fates in cells [55]: it is converted to (i) lactate via LDH-A or (ii) acetyl-CoA in mitochondria via the PDHc to enter the TCA cycle. These fates are regulated but not limited by cell type, ATP status, and several intrinsic and extrinsic factors as follows:

In normal differentiated eukaryotic cells, pyruvate enters the mitochondrion,

where it is converted into acetyl-CoA by the PDHc. This conversion initiates the

TCA cycle, followed by OXPHOS, where oxygen serves as the final electron acceptor

from NADH and FADH2. This step is crucial as it reoxidizes NADH to

NAD+, essential for the continuation of glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the

conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA (Fig. 1). Thus, under aerobic conditions,

glycolysis and subsequent OXPHOS are the preferred pathways for ATP production,

with the majority of ATP being generated through mitochondrial oxidative

activity. In rapidly contracting skeletal muscle cells, when the energy demand exceeds

what OXPHOS can provide alone, pyruvate remains in the cytoplasm and the

Warburg-like glycolysis becomes a vital alternative for rapid ATP production.

Glycolysis can produce ATP approximately 100 times faster than OXPHOS. Under

hypoxic conditions, the glycolysis product, pyruvate, is converted into lactate

by LDH-A to sustain ATP production. This shift to lactate production is regulated

by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), a transcription factor that plays a

critical role in oxygen homeostasis and is upregulated in response to low oxygen

levels through various signaling pathways. Thus, it can be assumed that muscle

cells under specific conditions employ the Warburg effect to produce ATP [56]. In cells that completely lack mitochondria, such as mature erythrocytes,

pyruvate cannot undergo OXPHOS regardless of oxygen availability. Consequently,

these cells rely solely on the ‘Warburg effect’ to produce ATP as oxygen is

abundant in erythrocytes [57]. In specific tissues like the inner medulla of the kidney, which is poorly

vascularized, pyruvate remains in the cytosol and is converted to lactate.

Despite having mitochondria, these tissues rely largely on fermentation of

glycolysis for energy production due to limited oxygen availability [58].

After elucidating the central role of pyruvate in ATP production and Warburg-like glycolysis, the subsequent paragraphs will present and discuss examples of non-carcinogenic cells that employ Warburg-like glycolysis for energy production.

As mentioned above, under certain conditions, normal cells may temporarily or constantly exhibit a preference for Warburg-like glycolysis. This phenomenon is also observed during rapid cell division, activation of immune cells, or during the regeneration phase of tissue repair, where cells rely more heavily on glycolysis for energy. Overall, the microenvironment of the cell determines the fate of pyruvate following the initial ten steps of glycolysis. Recent studies have revealed significant roles for Warburg-like glycolysis in various proliferative cell types, including pluripotent stem cells [59] and angiogenic endothelial cells [60].

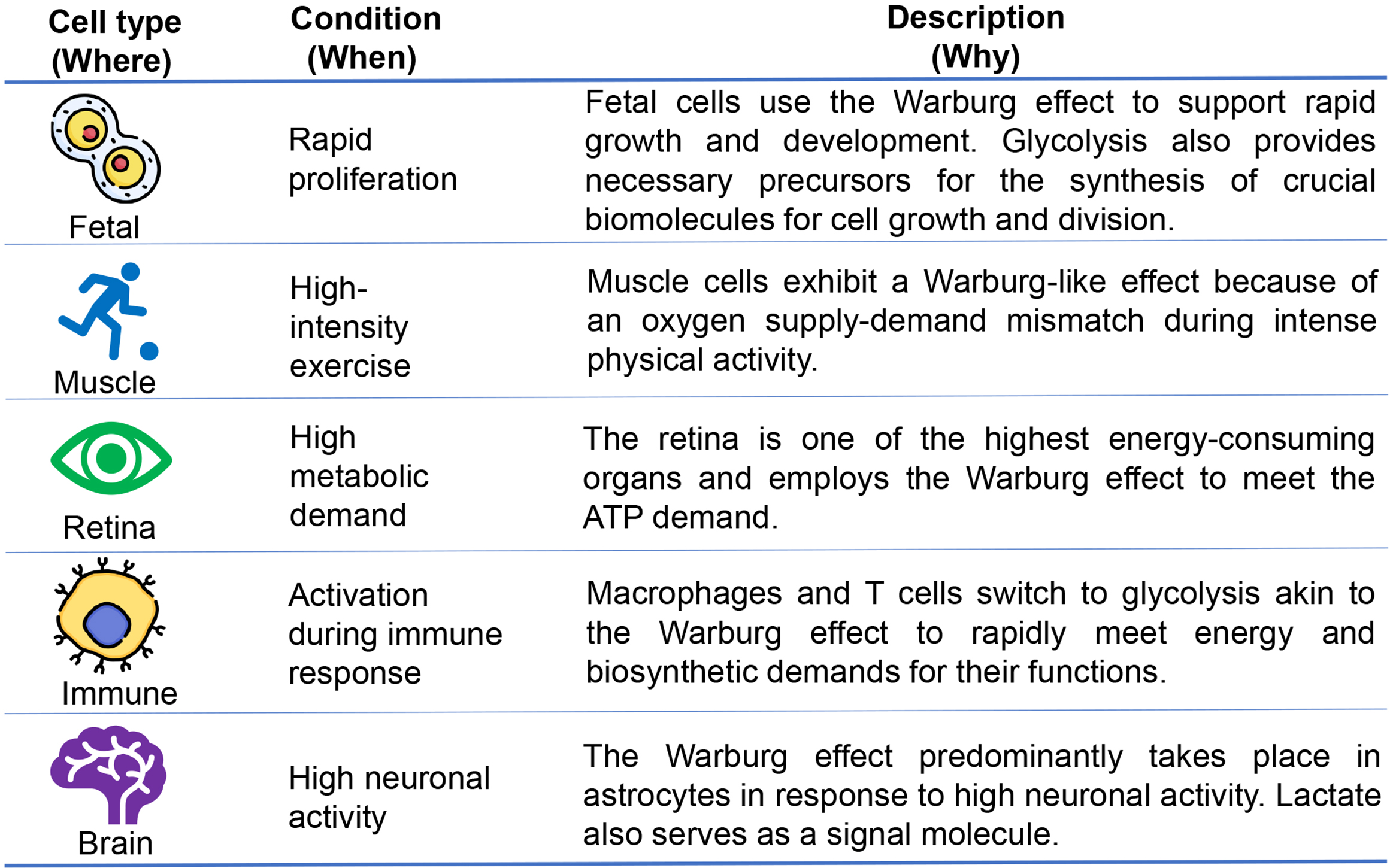

Examples of non-carcinogenic cells (where) that employ the Warburg effect for ATP production under specific conditions (when) highlight the metabolic flexibility of cells (why) are summarized in Fig. 2 and further explored in the subsequent paragraphs.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Occurrences of the Warburg effect in non-carcinogenic cells. The Warburg effect, a hallmark of proliferating cells, including fetal cells, is essential as glycolysis provides intermediates for the synthesis of important biomolecules necessary for growth and division. In addition to fetal cells, normal differentiated cells, including muscle cells, retina, immune cells, and brain cells, show a preference for glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation to meet their energy and biosynthetic demands.

One might assume that a dividing cell would require a large amount of energy. However, many unicellular organisms proliferate using the Warburg effect, showing that this metabolism can provide sufficient energy for cell proliferation [32]. This raises the question of why proliferating cells select less efficient metabolism. Despite its inefficiency, Warburg-like glycolysis provides a special advantage for rapidly dividing cells, as seen across various species, suggesting a link between this energy generation method and cell proliferation. Beyond basic energy needs for cellular functions, growth and cell division require the synthesis of new cellular components [32]. The Warburg effect might represent an ancient evolutionary strategy that balances ATP production with the generation of necessary components for new cell mass. The underlying reasons why many proliferating cells exhibit the Warburg effect remain elusive. One possible explanation is that inefficient ATP production becomes an issue only when resources are limited, which is not the case for proliferating mammalian cells that have a steady supply of glucose and nutrients [61]. It is speculated that this effect could enable cells to sustain substantial reserves of glycolytic intermediates. Such reserves could promote the activation of the pentose phosphate pathway and other biosynthetic pathways derived from glycolysis [62]. This benefit might persist even when a significant portion of the glycolytic flow results in the secretion of lactate. Recent studies on actively proliferating cells indicate that ATP may never be limiting. Regardless of how much they are stimulated to divide, cells using aerobic glycolysis exhibit high ATP/ADP and NADH/NAD+ ratios [63, 64].

Minor alterations in the ATP/ADP ratio can hinder cell growth, and cells lacking sufficient ATP often undergo apoptosis [65, 66]. In normal proliferating cells, ATP production from glucose is crucial, and if compromised, they may experience cell cycle arrest and re-engage in catabolic metabolism. Signaling pathways are in place to monitor and respond to the cell’s energy status. Proliferating cells not only need to produce ATP but also require substantial amounts of nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids for biomass replication. Metabolic pathways are tailored to support these demands; for example, the palmitate synthesis, a key component of cellular membranes, needs elevated levels of ATP and acetyl-CoA derived from glucose [67]. This underscores a broader view of metabolism where glucose is not solely used for energy but also serves as a critical building block for cell growth and function.

Notably, embryos display a metabolic phenotype distinct from differentiated somatic cells, similar to rapidly proliferating cancer cells [68]. This adaptation steers pyruvate away from the TCA cycle, favoring its conversion to lactate, which leads to an accumulation of glycolytic intermediates. Although this method of ATP generation is inefficient, it satisfies other crucial metabolic needs, such as biomass production and redox balance, providing proliferating cells with a selective growth advantage. This model advances our understanding of embryo metabolism, highlighting a complex network of metabolic processes that impact viability, which contrasts with the prevailing belief that carbohydrate metabolism primarily occurs through oxidative phosphorylation. A better grasp of embryo metabolism can enhance embryo viability in vitro and prevent embryos from having to adjust to less-than-ideal culture conditions, thereby reducing potential harm to their future growth and development [68].

To meet the increased energy demands of exercise, skeletal muscle activates various metabolic pathways to produce ATP both anaerobically (without oxygen) and aerobically from the onset of exercise, aligning precisely with the requirements of the exercise situation [69]. During high-intensity exercise, physiological conditions can lead to increased lactate production due to oxygen limitations, resembling the Warburg effect [70]. However, this increase is largely due to an oxygen supply-demand mismatch rather than the intrinsic metabolic preference observed in cancer cells. The continual supply of ATP is crucial for skeletal muscle contraction during exercise, vital for sports performance in events lasting from seconds to several hours [71]. As muscle stores of ATP are limited, pathways such as phosphocreatine breakdown, muscle glycogen degradation, and OXPHOS, using reducing equivalents from carbohydrate and fat metabolism, are activated to sustain ATP resynthesis. The contribution of these pathways varies primarily with the intensity and duration of the exercise [70].

Cells in high-energy demanding organs, such as the retina [72], may shift to Warburg-like glycolysis under stress or specific physiological demands. Notably, the retina is one of the most energy-intensive organs, surpassing even the brain in metabolic rate. In response to these high energy demands, blood vessels in the retina dynamically grow and regress, leading to elevated lactate levels despite adequate oxygen availability and increased mitochondrial activity [21].

The retina houses two types of photon-absorbing receptors: rods, which are crucial for vision in dim light, and cones, necessary for daylight and color vision [73]. These photoreceptors are encapsulated by a plasma membrane that includes disc membranes loaded with rhodopsin, a light-absorbing G-protein coupled receptor. Daily, approximately 10% of the outer segment tips of these photoreceptors are shed and ingested by neighboring retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. This material is partially recycled back to the photoreceptors and other retinal cells in a process known as phagocytosis [74], which is essential for the continuous provision of critical nutrients like glucose and oxygen for the survival and maintenance of photoreceptor cells [75]. The synthesis of new membrane discs (disc biogenesis) is crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of photoreceptor cells and effective RPE-photoreceptor interactions, suggesting that the Warburg effect might be vital for photoreceptor membrane biosynthesis [76].

Additionally, the retina is a post-mitotic neuronal tissue comprising seven layers of cells, including the highly metabolic rod and cone photoreceptor cells. These cells have an energy expenditure nearly equivalent to that of cancer cells. Glycolysis is indispensable for the survival of photoreceptor cells; its ablation leads to retinal degeneration [71], whereas upregulation is neuroprotective [77]. Warburg-like glycolysis is crucial for normal rod function and helps prevent cone degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa [78], while it also facilitates the synthesis of cone outer segments [79].

Emerging research underscores a significant metabolic parallel between activated inflammatory immune cells and glycolytic tumor cells. Upon activation, cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells undergo a dramatic shift from OXPHOS to Warburg-like glycolysis [80]. This metabolic reconfiguration is crucial, as it facilitates rapid ATP production and generates necessary metabolic intermediates for the biosynthesis of immune and inflammatory proteins, thereby equipping these cells to swiftly respond to pathogens or injury [81, 82].

This shift is characterized by an increased accumulation of specific TCA cycle intermediates, particularly citrate and succinate [83]. Citrate is strategically rerouted from the TCA cycle to support lipid biosynthesis, which is vital for maintaining the structural integrity and signaling functions of immune cell membranes. This lipid synthesis also plays a role in creating lipid-based signaling molecules that are essential for initiating and regulating inflammatory responses [84]. Disruption of citrate metabolism not only affects cell membrane integrity but can also severely impair the ability of dendritic cells to activate T cells, thereby dampening the adaptive immune response [85].

Moreover, succinate serves as a crucial signaling molecule that modulates the

activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1

However, the advantages of this metabolic shift come with inherent challenges, notably the induction of lactic acidosis, which can profoundly impair immune cell function [88]. The accelerated glycolysis seen in activated immune cells leads to significant production of lactate and protons. To manage this, cells upregulate lactate transporters like MCT1 and MCT4, which are critical for exporting these byproducts to maintain glycolytic flux [89]. However, in the sites of chronic inflammation (similar to the tumor TME), an adverse lactic acid gradient can develop, leading to the reuptake of lactate and protons by immune cells. This results in a lowered intracellular pH, which can significantly hamper further glycolytic activity and, consequently, impair the functionality of monocytes and T cells, reducing their ability to defend against pathogens and inflammation [90, 91].

However, regulating immune responses extends beyond a simple balance between glycolysis and OXPHOS, encompassing a broad spectrum of interacting metabolic pathways that influence immune function [88, 92]. Additionally, pro-inflammatory stimuli induce metabolic reprogramming in both myeloid and lymphoid cells, causing an upregulation Warburg-like glycolysis that regulates the balance between inflammatory and regulatory immune phenotypes [93]. The understanding of these complex metabolic adaptations opens avenues for novel therapeutic interventions. By targeting the metabolic pathways engaged during the Warburg effect in immune cells, it might be possible to modulate their activity—either enhancing their response in conditions where immune activation is needed or suppressing it in diseases characterized by excessive inflammation, such as autoimmune diseases. Potential strategies could involve pharmacological inhibitors of key glycolytic enzymes or transporters, as well as dietary interventions like glucose restriction or ketogenic diets, which have been shown to affect glycolytic metabolism and could thereby influence immune cell function [94].

Research on brain energy metabolism has lagged behind that of muscle metabolism, yet striking parallels exist between these two tissues. In both cases, two types of neighboring cells interact during periods of heightened activity: neurons and astrocytes in the brain, and type I and II fibers in skeletal muscle. Research focusing on muscle have more thoroughly explored glycolytic metabolism than those studying the brain cells. For instance, Pedersen et al. [95] debunked the long-held belief that lactate causes muscle fatigue. Instead, they suggest that lactate is a predominant product of glycolysis in the brain, occurring in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions within neuronal and astrocytic cells. This notion is central to the ongoing debate over the primacy of glucose versus lactate, positing that both are essential—glucose as the initial glycolysis substrate and lactate as a fuel for the mitochondrial TCA cycle. Furthermore, it is suggested that lactate is the primary product of cerebral glycolysis and thus a major substrate for the TCA cycle [50].

In their study, Mächler et al. [96] observed that lactate in the blood is more readily absorbed by astrocytes and neuronal cells, with higher concentrations in astrocytes, supporting the transfer of lactate from astrocytes to neurons via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs). Research by Suzuki et al. [97] found that lactate release in the hippocampus is linked to memory formation in rats, noting that blocking MCT1 expression in astrocytes impedes long-term memory formation, highlighting the critical role of astrocyte-neuron metabolic coupling in neurological disorders, including memory impairment and cognitive deficits like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [98, 99]. Notably, lactate is predominantly formed in astrocytes from glucose or glycogen in response to neuronal activity, illustrating tight metabolic coupling between neurons and astrocytes. It is transferred from astrocytes to neurons to meet energetic needs and modulate functions such as excitability, plasticity, and memory consolidation. Lactate also plays a role in various homeostatic functions, setting the ‘homeostatic tone’ of the nervous system [99].

A recent review by Barros et al. [98] highlights further the role of the Warburg effect in brain tissue, where glucose is metabolized to lactate even in the presence of ample oxygen, particularly during high neuronal activity. This suggests a strategic metabolic adaptation rather than mere inefficiency. The study emphasizes that astrocytes, not neurons, primarily exhibit the Warburg effect. Their robust glycolytic activity, facilitated by the stabilization of the enzyme PFKFB3, is crucial for meeting the dynamic metabolic demands of the brain. Astrocytes also demonstrate the Crabtree effect—the suppression of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism by glycolysis, driven primarily by extracellular potassium (K+), enhancing lactate production to maintain energy supply to neurons. Factors such as nitric oxide (NO) and ammonium (NH4+) further inhibit mitochondrial respiration in astrocytes, boosting glycolysis. In contrast, neurons maintain a balance between glycolysis and respiration, regulated by the Na+/K+ ATPase pump, to ensure efficient ATP production. During extreme neuronal activity or excitotoxicity, neurons may shift to producing lactate due to mitochondrial failure, underscoring a sophisticated metabolic interplay that is critical for maintaining brain function and health.

Together, the data presented above indicate that Warburg-like glycolysis is an alternative strategy that normal cells employ to satisfy their energy needs and maintain homeostasis. Importantly, the above highlights that lactate is not merely a metabolic waste product; rather, it plays a central role in metabolism, particularly in Warburg-like glycolysis, where it serves as the final product. The pivotal role of lactate in the Warburg effect is further discussed in the following section.

Lactate, often misunderstood since its discovery in 1780 as merely a metabolic waste product, has undergone a significant reevaluation of its biochemical and physiological roles [99]. Initially thought to be associated with harmful effects under hypoxic conditions, lactate is now acknowledged as a versatile and crucial metabolite in various biological processes, challenging conventional views of its function under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions [100]. However, much of our knowledge on the formation and fate of lactate originates from previous investigations on muscular exercise [101].

Introduced by Brooks [102], the lactate shuttle hypothesis has been pivotal in reshaping our understanding of lactate. This hypothesis elucidates lactate’s roles in transporting oxidative and gluconeogenic substrates and its involvement in cellular signaling mechanisms. Contrary to previous beliefs, Brooks’ research demonstrated that lactate formation and utilization occur under completely aerobic conditions, establishing it as a significant modulator in coordinating systemic metabolism. This hypothesis proposes (the ‘lactate shuttle’ concept), that lactate, actively shuttled between tissues, serves dual roles: as a fuel consumed by mitochondria for energy production and as a signaling molecule that communicates metabolic status between cells. For example, lactate produced in muscle during intense exercise is transported to neurons or heart cells, where it is utilized as a primary energy source. This intracellular and intercellular shuttle system optimizes energy resources under various physiological conditions, ranging from intense physical activity to changes in metabolic demand due to diet or fasting. The hypothesis also emphasizes lactate’s role in cell signaling, suggesting that it triggers adaptations in metabolism based on the energy needs and functional status of different tissues. Brooks’ research showed that this shuttling mechanism is a fundamental aspect of metabolism, challenging the traditional view of lactate as merely a byproduct of anaerobic metabolism and establishing it as a significant modulator in coordinating systemic metabolism. This paradigm shift has profound implications for understanding energy distribution and utilization in the body, highlighting the metabolic versatility of lactate beyond its conventional roles.

In the area of neuroscience, lactate is recognized as an essential supplementary energy source for the brain, particularly when glucose levels are insufficient [103]. It supports neuronal activity, notably maintaining the function of proopiomelanocortin neurons, integral to the body’s energy balance. This underscores lactate’s importance beyond mere energy supply, highlighting its role in neural function and brain health [104]. A recent study by Cerina et al. [105] have further shown that lactate can enhance memory formation and recovery from nerve injury, underscoring its neuroprotective effects.

Moreover, lactate serves as a major promoter of the TCA cycle, especially in conditions such as fasting or intense physical activity. It can exceed glucose concentrations in the bloodstream, reflecting its role as a primary fuel source [106]. Lactate’s significant contribution to the TCA cycle in specific tissues, including those affected by lung and pancreatic cancers, emphasizes its pivotal role in cellular metabolism and as a potential target in cancer treatment [107].

Lactate’s regulatory functions are evident through its accumulation, which inhibits glycolysis via a feedback mechanism [108]. It also facilitates the release of magnesium from the endoplasmic reticulum, linking it to essential metabolic feedback loops and mitochondrial bioenergetics. These processes illustrate lactate’s central role in energy regulation and stress response at the cellular level [109].

Despite the traditional view that lactate signifies anaerobic metabolism, it is continuously produced and utilized across various cells and tissues under fully aerobic conditions, including during rest. This production is evident in physiological states such as exercise, high altitude exposure, trauma, and cardiac events, challenging outdated notions that glycolytic flux is directed solely to mitochondrial respiration through pyruvate [29].

In oncology, lactate’s role is crucial for cancer cell survival and proliferation. The acidic environment created by lactate production facilitates the breakdown of the basement membrane, enhancing cancer cell access to blood vessels and promoting metastasis. This aspect of lactate metabolism in cancer underscores its potential as a therapeutic target. Lactate’s influence extends even to altering the immune environment around tumors, making it a key player in the immune response to cancer [110].

Lactate is also integral in exercise physiology, where it serves as a rapid fuel source for muscles during intense physical activity [110, 111]. This challenges the old misconception that lactate production during exercise is a marker of anaerobic metabolism and muscle fatigue. Instead, lactate acts as a critical energy reservoir, particularly for heart and skeletal muscles, supporting sustained high-energy activities [112].

Furthermore, lactate plays a significant role in adapting to chronic conditions, such as heart failure, where it can indicate alterations in metabolic processes [113]. Elevated lactate levels may reflect a compensatory mechanism in response to decreased cardiac output, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for assessing disease severity and progression [114]. Lactate’s implications in medical research are profound. It is increasingly recognized as a crucial biomarker in critical care settings, where its levels are monitored to assess the severity and progression of conditions like sepsis and multiorgan failure. The rate of lactate clearance is used to guide therapeutic interventions, highlighting its importance in clinical diagnostics and treatment strategies [100].

In summary, the understanding of lactate has evolved from viewing it as a simple byproduct of metabolic distress to recognizing it as a versatile and indispensable metabolite with complex roles in cellular metabolism, signaling, and pathophysiological conditions. This shift in perception has debunked long-held dogmas and opened new avenues for biomedical research and therapeutic applications. Lactate now stands as a central figure in the link between glycolytic and aerobic pathways, highlighting its multifaceted roles in health and disease.

Having elucidated the diverse cellular contexts in which the Warburg effect manifests, as well as the central role of lactate in this pathway, the next section discusses the implications of this metabolic phenomenon in clinical realms. This includes its role in the treatment of cancer and other diseases, and the potential for therapeutic targeting.

Stable glucose metabolism is crucial for cancer cell survival and progression.

Cancer cells depend on the Warburg effect to satisfy their metabolic demands,

while oncogenic mutations trigger glycolytic enzymes [115]. Glucose enters the

cell via glucose transporters (GLUTs) transporters and is phosphorylated by HKs in the cytoplasm,

trapping it inside the cell. Oncogenes like MYC, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral

oncogene homologue (KRAS), and yes-associated protein (YAP) upregulate GLUT1

expression in cancer cells [116, 117, 118]. YAP overexpression and p53 loss-of-function

mutations enhance GLUT3 expression, leading to its accumulation in the plasma

membrane [41]. In cancer cells, the hyperactivated

hosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway boosts HK2 activity by promoting

its association with mitochondria [119]. HIF-1

Various subtypes of enzymes associated with the Warburg effect are active in

different cancer types, in including glucose transporters (GLUTs) 1/2/3/4, HK

1/2/3, triosephosphate isomerase (TPI), GAPDH, aldolase A (ALDOA),

glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI),

phosphofructokinase-2/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFKFB) 3/4, phosphoglycerate

kinase 1 (PGK1), phosphoglyceric acid mutase-1 (PGAM1), pyruvate kinase M2

(PKM2), LDH A/B, monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT-1), hexose-6-phosphate

isomerase (HPI), PFK-L, aldolase (ALD)-A, and enolase (ENO)-

Non-coding RNAs, including lncRNAs, miRNAs, and circular RNAs, directly regulate the Warburg effect [123]. Gene mutations, TME remodeling, and immune system interactions are closely associated with the Warburg effect. Rather than an OXPHOS-to-glycolysis switch, there is an upregulation of glycolysis for biomass synthesis and reducing equivalents, in addition to ATP production [124]. Significant glycolytic intermediates are diverted to the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to produce NADPH, which helps cancer cells cope with reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and oxidative stress, opening new avenues for anticancer interventions [125].

Targeting the Warburg effect is considered a potential strategy to fight various types of cancer relying on glycolysis for ATP synthesis. This metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells via the Warburg effect supports rapid cell proliferation and creates vulnerabilities that can be targeted therapeutically [126]. Insights into the Warburg effect have led to innovative strategies to disrupt this pathway and stifle cancer growth. Importantly, the development of drugs targeting the Warburg effect shows promising potential in tumor treatment [43]. Key target enzymes for potential therapeutics include GLUTs, hexokinases (HKs), phosphofructokinases (PFKs), LDHs, and PKM2 [127].

Previous reviews have identified several compounds that mediate the Warburg effect [128], including: (i) enhanced expression and uptake of glucose transporters, (ii) increased NADPH production via the PPP pathway, (iii) changes in glycolytic enzyme activity, such as HIF/MYC-driven activation of HK2, LDH-A, and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-1, along with a shift from the active pyruvate kinase isozyme M1 to the less active M2, and (iv) elevated lactate production. Targeting these mechanisms holds therapeutic promise. For example, blocking glucose transport can reduce cancer cell glucose availability, triggering apoptosis [129]. Studies have also explored the efficacy of GLUT inhibitors and the role of compounds like 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), dichloroacetate (DCA), and 3-bromopyruvate (3-BP) in cancer treatment [128]. This review does not cover therapeutics that target enzymes involved in the Warburg effect, as these have been reviewed recently. For example, in their review, Barba et al. [126] discussed pharmacological strategies targeting glycolytic enzymes, highlighting challenges in achieving therapeutic efficacy and examining the Warburg effect’s utility as an early diagnostic tool. Shimi [130] explored dietary regimens targeting the Warburg effect, suggesting that combining cancer therapies with diet-based strategies may improve treatment outcomes. Tran et al. [128] reviewed the research efforts targeting the Warburg effect to sensitize chemoresistant cancers to treatments, emphasizing metabolic plasticity within the tumor microenvironment. Liao et al. [43] reviewed the roles of regulatory enzymes in the Warburg effect, presenting novel approaches for early diagnosis and treatment. Poff et al. [131] focused on interventions inducing ketosis to target the glycolytic phenotype of cancers, particularly for secondary chemoprevention of low-grade gliomas, as evidenced by reductions in disease progression markers and clinical symptoms. Some examples of drugs targeting enzymes implicated in the Warburg effect and their targets are summarized in Table 3 (Ref. [132, 133, 134, 135]).

| Drug name | Target enzyme | Status/Usage | Reference |

| Lonidamine | Hexokinase (HK) | Used in some countries for cancer treatment; not approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | [132] |

| Tebentafusp-tebn | Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) | FDA approved for uveal melanoma as an immune therapy; indirect relation to PKM2 | [133] |

| Gossypol (AT-101) | Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A) | In clinical trials for cancer therapy; not FDA approved as LDH-A inhibitor | [134] |

| AZD3965 | Monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) | In clinical trials for cancer therapy; targeting lactate export | [135] |

Increasing research indicates that the Warburg effect plays significant roles not only in tumors but also in non-tumor diseases such as inflammation [136], pulmonary hypertension [137], idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [138], and structural remodeling in the heart [139]. A study by Abdel-Haleem et al. [48], also suggested that the Warburg effect is involved in other non-cancerous conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, where metabolic dysfunction plays a crucial role. The Warburg effect may also be central to the metabolism of rapidly proliferating parasites, such as Plasmodium and Toxoplasma, and in rapidly growing microbes like yeast and Escherichia coli [48].

The immunologic Warburg effect presents a promising avenue for treating autoimmune diseases using both pharmacological and dietary strategies [140]. Pro-inflammatory signals can trigger a metabolic switch in both myeloid and lymphoid cells, leading to the upregulation of glycolysis in a manner similar to the Warburg effect observed in cancer cells [141]. This metabolic reprogramming occurs in various cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems, including lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages. In response to inflammatory stimuli, these cells undergo a shift to Warburg-like metabolism, characterized by increased glycolysis which supports their rapid proliferation and functional demands during immune responses [84]. Blocking the upregulation of the Warburg-like effect diminishes inflammatory responses, hinders the differentiation and function of pro-inflammatory cell types, and fosters anti-inflammatory and regulatory immune phenotypes [140]. However, the reasons for glycolytic reprogramming in immune cells are not fully understood, and the common assumptions linking it to anabolic biomass production or ATP production kinetics have yet to be definitively proven. Therefore, further research is essential to comprehensively understand the necessity of Warburg-like glycolysis for inflammatory immune functions.

Moreover, inhibiting the Warburg effect is increasingly considered as a therapeutic strategy for autoimmune diseases. Notably, key insights include the role of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH in regulating cytokine mRNA translation and the importance of glycolytic enzymes and metabolites in controlling inflammatory transcriptional programs [83]. Pharmacologic inhibitors targeting key enzymes are among the strategies aiming at this pathway. For instance, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), a derivative of fumarate, inactivates the catalytic cysteine of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH in animal models and humans, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects through the inhibition of Warburg-like glycolysis. DMF covalently attaches to cysteine residues in a process called succination and has been used to treat autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and multiple sclerosis (MS) [142]. In 2013, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved DMF for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS under the name Tecfidera [143]. Moreover, Kornberg [144] has recently reviewed the pharmacologic and dietary approaches targeting the Warburg effect to treat immune system-related diseases, which will not be discussed here.

Collectively, these insights suggest that Warburg-like glycolysis, a common feature among inflammatory cell types and a crucial regulator of immune function, is a promising therapeutic target for treating immune dysregulation disorders without causing widespread toxicity to normal tissues that depend on oxidative metabolism. Unlike cancer treatments that require total eradication, managing autoimmune diseases only necessitates modulating the immune response. The mechanisms through which Warburg-like glycolysis and the balance between glycolysis and OXPHOS influence immune responses continue to be explored, with significant advancements anticipated in the future.

The Warburg effect has been also implicated in cardiovascular diseases such as

atrial fibrillation (AF)—the most common sustained arrhythmia. In AF, the

fibrillating atria tend to prefer glucose over fatty acids due to a metabolic

shift towards a ‘fetal phenotype’ under pathological stress [48]. This shift

manifests as decreased fatty acid and pyruvate oxidation in mitochondria, coupled

with an increase in aerobic glycolysis, which generates two ATP molecules per

glucose molecule. Such metabolic alterations are accompanied by heightened atrial

lactate production, upregulated glycolytic enzymes, and downregulated PDHc

echoing the patterns observed in the Warburg effect. Furthermore,

HIF-1

Thus, targeting the Warburg effect as a therapeutic strategy shows considerable promise in both cancer and various non-tumor diseases. Cancer cells rely on the Warburg effect for stable glucose metabolism, which supports rapid proliferation and survival by upregulating key glycolytic enzymes and pathways. Oncogenic mutations further enhance glycolysis, making these pathways attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. This metabolic reprogramming presents vulnerabilities that can be exploited to inhibit cancer growth, with drugs targeting enzymes such as GLUTs, HKs, PFKs, LDHs, and PKM2 showing potential in preclinical and clinical studies. Beyond oncology, the Warburg effect plays a crucial role in non-cancerous conditions, including inflammation, pulmonary hypertension, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and cardiovascular diseases like atrial fibrillation. Inflammation and immune responses often involve Warburg-like metabolic reprogramming in various immune cells, suggesting that inhibiting aerobic glycolysis could mitigate inflammatory diseases and autoimmune conditions. This reprogramming also occurs in cardiovascular diseases, where it supports pathological structural remodeling and could be targeted to improve heart function. Additionally, the Warburg effect is implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, where metabolic dysfunction is a key factor. The effect is also central to the metabolism of rapidly proliferating parasites and microbes, indicating broader implications for infectious diseases. Overall, the Warburg effect represents a multifaceted target for therapeutic strategies across a range of diseases. Continued research into its mechanisms and the development of drugs that inhibit key enzymes involved in glycolysis will probably enhance treatment outcomes for both cancer and other metabolic disorders.

Cancer cells show a notably distinct metabolic profile compared to most normal tissues, characterized by their high uptake of glucose and glutamine to fuel glycolysis. Besides the well-studied and characterized roles of glutamine and glucose in cancer cell metabolism, N-acetylaspartate (NAA), one of the most abundant brain metabolites [146], emerges as a notable player in the metabolic reprogramming associated with certain cancers [147]. Derived in part through glutaminolysis, NAA is synthesized within mitochondria from aspartate and acetyl-CoA, akin to the synthesis of citrate from oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA [148]. Analogous to citrate, NAA is exported from mitochondria and utilized in lipid biosynthesis—a critical process for biomass accumulation in proliferating cancer cells. Under normoxic conditions, cancer cells predominantly rely on glycolysis coupled with glutaminolysis for their carbon sources [149]. However, under hypoxic conditions, the reliance shifts towards alternative substrates like acetate for lipid synthesis, with NAA providing a significant source of acetate upon hydrolysis. Interestingly, the biosynthetic enzyme for NAA, aspartate N-acetyltransferase (gene: NAT8L), which is normally expressed in tissues known for high lipid turnover such as adipose tissue and the nervous system, is also found upregulated in several cancers, including lung [150] ovarian [151], and prostate [152] cancers. This upregulation suggests a specialized adaptation of cancer cells to harness NAA for metabolic needs beyond its conventional roles, emphasizing the complexity and versatility of metabolic reprogramming in cancer pathophysiology.

However, the landscape of cancer metabolism showcases extreme heterogeneity, as each type of cancer not only originates from different tissues but also exhibits unique metabolic phenotypes [153]. Such diversity is evident even within a single type of cancer, where individual cells within the same tumor can display varying metabolic behaviors [154]. It is worthwhile to mention that these metabolic phenotypes are highly adaptable and show greater plasticity than those observed in normal tissues, providing cancer cells with a robust mechanism to survive and thrive in adverse conditions [155]. This adaptability allows cancer cells to modify their metabolic strategies in response to dynamic changes in the microenvironment, thus offering them a selective advantage in otherwise unfavorable conditions [156].

The traditional concept of the Warburg effect does not fully encapsulate the complexity of cancer metabolism [157]. While the Warburg effect is prevalent in many malignant tumors, OXPHOS still plays a crucial, and sometimes dominant, role in the energy production of some cancers [158]. Warburg’s observation that cancer cells produce lactate while normal cells produce CO2 from glucose led to the misconception that cancer cells rely on glycolysis due to mitochondrial destruction. However, mitochondria in cancer cells are intact, and their respiratory rate is higher than in normal cells [159].

Contrary to earlier beliefs, research shows that the ATP production in cancer cells can vary significantly; glycolysis can contribute as little as 1% to as much as 64% of the total ATP production, with the majority often being supplied by OXPHOS [27]. This variability has been confirmed by the study conducted by Zu and Guppy [38], which highlight that the extent of ATP production from glycolysis significantly differs across various cancer types, with the remainder being sourced predominantly from mitochondrial OXPHOS. Furthermore, both OXPHOS and the Warburg Effect are found to contribute to ATP production in different extents, influenced by the specific tumor environment, such as conditions of normoxia or hypoxia [18]. Such metabolic flexibility suggests that the Warburg effect is not a universal characteristic of all cancers. Instead, it becomes apparent that tumor cells within a single mass can exhibit a diverse array of metabolic phenotypes [160, 161]. Additionally, mutations in mitochondrial components like succinate dehydrogenase and metabolic enzymes such as isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 have a significant impact on these metabolic characteristics [162]. Disruption of mitochondrial OXPHOS by knocking down mitochondrial transcription factor A decreases tumorigenesis in lung cancer models [163]. Furthermore, Lee et al. [164] demonstrated that glucose is not a major ATP source in cancer cells; instead, fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and OXPHOS play key roles in ATP production. NADH from FAO is used for ATP synthesis via OXPHOS, and a calorie-balanced, low-fat diet significantly reduces tumor formation, whereas a high-fat diet increases it in pancreatic cancer models.

To elucidate these contradictory phenomena further, the concept of the ‘reverse Warburg effect’ was introduced [165]. This model proposes a complex metabolic interplay between glycolytic and oxidative cells within the tumor microenvironment. According to this model, Warburg-like glycolysis predominantly occurs not in the cancer cells themselves but in the stromal compartment surrounding the tumor. Stromal cells, such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), undergo glycolysis to produce pyruvate and lactic acid, which are then transferred to cancer cells [19, 166]. These metabolites are utilized by cancer cells to fuel their mitochondrial OXPHOS, thereby promoting efficient ATP production and enhancing their proliferative capacity. This metabolic coupling is facilitated by monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), which efficiently transport lactate and other high-energy fuels from the CAFs to the cancer cells, sustaining the tumor’s energy demands under both anoxic and aerobic conditions. In this way, epithelial cancer cells induce aerobic glycolysis in neighboring stromal fibroblasts, which then secrete lactate and pyruvate that the cancer cells uptake for use in the mitochondrial TCA cycle, leading to efficient ATP generation [167]. This host-parasite relationship, where epithelial tumor cells ‘corrupt’ the normal stroma, resonates with Warburg’s initial observations of a metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis in tumors, although in a reversed context [165].

Moreover, unbiased proteomic analysis and transcriptional profiling of

cancer-associated fibroblasts, particularly those deficient in caveolin-1

(CAV-1), reveal an upregulation of myofibroblast markers and glycolytic enzymes

under normoxic conditions [19]. The loss of stromal CAV-1 in human breast cancers

is associated with increased tumor recurrence, metastasis, and poor clinical

outcomes, suggesting that it may serve as a potential biomarker for the reverse

Warburg effect [19]. This underscores the critical role of stromal interactions

in the metabolic heterogeneity of tumors, where some cells maintain a glycolytic

phenotype while others predominantly utilize oxidative phosphorylation.

Therefore, the reverse Warburg effect describes a scenario where glycolysis in

the cancer-associated stroma supports the adjacent cancer cells metabolically.

This catabolite transfer allows cancer cells to generate ATP, increase

proliferation, and reduce cell death, playing a key role in their metabolic

adaptation and survival. Monocarboxylates such as lactate, pyruvate, and ketone

bodies are crucial in this process. MCT4, regulated by HIF-1

Recent evidence underscores the critical role of the TME in carcinogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The interactions between cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) significantly influence growth, metabolism, metastasis, and the overall progression of carcinoma [160, 169]. The reverse Warburg effect exemplifies how cancer cells and CAFs become metabolically intertwined. Cancer cells secrete hydrogen peroxide into the microenvironment, triggering oxidative stress in CAFs. This stress prompts CAFs to undergo aerobic glycolysis, producing energy-rich fuels such as pyruvate, ketone bodies, fatty acids, and lactate. These substrates are utilized by cancer cells to feed their mitochondrial OXPHOS, enhancing efficient ATP production. Loss of Cav-1 in stromal cells amplifies oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in CAFs, while upregulated monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) facilitate the transfer of these high-energy fuels from CAFs to cancer cells [170, 171, 172, 173].

Additionally, an increasing body of research indicates that lactate, often produced by glycolysis under hypoxic conditions in tumor cells or stromal cells, is not merely a waste product. Instead, it can be taken up by oxygenated tumor cells as a viable source of energy. Lactate is converted back to pyruvate by LDH-B and then enters the mitochondria to support OXPHOS, generating ATP [27]. This metabolic symbiosis is not exclusive to cancer; similar interactions are observed in normal physiological processes. For example, in the brain, neurons depend on OXPHOS to satisfy their energy needs, while astrocytes primarily utilize glycolysis. The lactate produced by astrocytes is then taken up by neurons, serving as an essential energy source and forming the basis of the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (ANLS) [174]. This phenomenon illustrates how metabolic cooperation between different cell types supports various tissue functions and energy demands.

Together, the above suggest that the Warburg effect and the reverse Warburg effect underscores the complex and heterogeneous nature of cancer metabolism. While the Warburg effect highlights the prevalence of glycolysis in cancer cells despite the presence of oxygen, the reverse Warburg effect reveals a collaborative metabolic relationship between cancer cells and their stromal environment. These phenomena illustrate that cancer cell metabolism is not uniformly glycolytic but can also significantly depend on oxidative phosphorylation, facilitated by metabolic coupling with the tumor microenvironment. Understanding these metabolic strategies enhances our ability to design targeted therapies that disrupt specific metabolic pathways unique to cancer cells’ survival and proliferation. Future research should focus on the molecular mechanisms that regulate metabolic flexibility in cancers and how these pathways can be exploited to develop more effective, personalized cancer treatments. By broadening our perspective beyond the traditional views of cancer metabolism, we open new avenues for research and treatment, challenging the long-held misconceptions about cancer cells’ energy production. This evolving understanding promises to refine therapeutic strategies and improve outcomes for patients with diverse types of cancer.

This review highlights that the Warburg effect, traditionally associated with cancer metabolism, also plays a crucial role in non-cancerous cells under various conditions, challenging the notion that it is inherently detrimental. Recent insights have revolutionized our understanding of lactate formation; it is now recognized that lactate can be produced even in the presence of sufficient oxygen, debunking the old belief that it forms only during oxygen scarcity [23].

The metabolic reprogramming observed in cancer cells, known as the Warburg Effect, influences tumor signal pathways and cellular responses far beyond genetic mutations, making it a prime target for therapeutic interventions. Emerging treatments are being developed to exploit these cancer-specific metabolic traits, promising more selective and effective strategies that could enhance clinical outcomes with fewer side effects.

Importantly, the Warburg Effect is not exclusive to cancer. It manifests in various cell types, reflecting a universal cellular strategy for energy production and adaptation to environmental stresses. This effect involves metabolizing glucose to lactate despite ample oxygen, challenging the traditional view of lactate as merely a waste product and recognizing its integral role in cellular metabolism under both physiological and pathological conditions.

The distinction between aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis has traditionally been linked to cancerous and non-cancerous states, respectively. However, this distinction is overly simplistic, as both processes are manifestations of the same glycolytic pathway. The fate of pyruvate—and whether it leads to lactate or continues into the mitochondria for further oxidation—depends on various factors, including cell type, signaling, energy needs, and developmental stage.