1 Department of Molecular and Clinical Medicine, Institute of Medicine, Gothenburg University, 41345 Gothenburg, Sweden

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) continue to be the leading cause of mortality worldwide, necessitating the development of novel therapies. Despite therapeutic advancements, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) show detrimental effects at high concentrations but act as essential signalling molecules at physiological levels, playing a critical role in the pathophysiology of CVD. However, the link between pathologically elevated ROS and CVDs pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Recent research has highlighted the remodelling of the epigenetic landscape as a crucial factor in CVD pathologies. Epigenetic changes encompass alterations in DNA methylation, post-translational histone modifications, adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent chromatin modifications, and noncoding RNA transcripts. Unravelling the intricate link between ROS and epigenetic changes in CVD is challenging due to the complexity of epigenetic signals in gene regulation. This review aims to provide insights into the role of ROS in modulating the epigenetic landscape within the cardiovascular system. Understanding these interactions may offer novel therapeutic strategies for managing CVD by targeting ROS-induced epigenetic changes. It has been widely accepted that epigenetic modifications are established during development and remain fixed once the lineage-specific gene expression pattern is achieved. However, emerging evidence has unveiled its remarkable dynamism. Consequently, it is now increasingly recognized that epigenetic modifications may serve as a crucial link between ROS and the underlying mechanisms implicated in CVD.

Keywords

- cardiovascular disease

- epigenetic

- ROS

- oxidative stress

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Despite significant advances in medical treatments and interventions, the complex mechanisms underlying the development and progression of CVDs continue to challenge researchers and healthcare professionals. In recent years, an emerging body of research has shed light on the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and epigenetic modifications in cardiovascular health and disease [1]. ROS are highly reactive molecules containing oxygen that are generated during various cellular processes. Under normal physiological conditions, ROS serves as essential signalling molecules involved in cellular communication, immune response, and regulation of vascular tone. However, excessive or uncontrolled ROS production can lead to oxidative stress, causing damage to cellular components such as DNA, proteins, and lipids [2]. This oxidative stress is implicated in the pathogenesis of several cardiovascular disorders, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, heart failure (HF), and ischemic heart disease [3].

At the same time, the field of epigenetics has been making remarkable step in understanding the regulation of gene expression without changes to the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNAs (miRNAs), play a crucial role in modulating gene expression patterns during normal development and cellular function [4]. However, epigenetic alterations can occur in response to various environmental and lifestyle factors, influencing the risk of developing complex diseases, including cardiovascular disorders [5].

Recent research has started to reveal intricate connections between ROS and epigenetic modifications in the context of CVDs. Oxidative stress triggered by ROS can directly impact epigenetic mechanisms, leading to changes in gene expression patterns in cardiovascular cells and tissues [6]. Conversely, epigenetic modifications can regulate the expression of genes involved in ROS production and antioxidant defense, further influencing oxidative stress levels and cardiovascular homeostasis [7].

Understanding the interplay between ROS and epigenetics in the context of CVDs holds immense promise for the development of novel therapeutic strategies and targeted interventions. Identifying key epigenetic regulators affected by oxidative stress may uncover potential drug targets to mitigate the harmful effects of ROS and enhance the body’s antioxidant defense systems. Furthermore, investigating how specific environmental factors and lifestyle choices influence epigenetic modifications in the presence of ROS can provide invaluable insights into personalized approaches for CVDs prevention and management [8, 9].

This review explores the ROS-epigenetics connection in CVDs, examining current research, molecular mechanisms, and potential clinical implications.

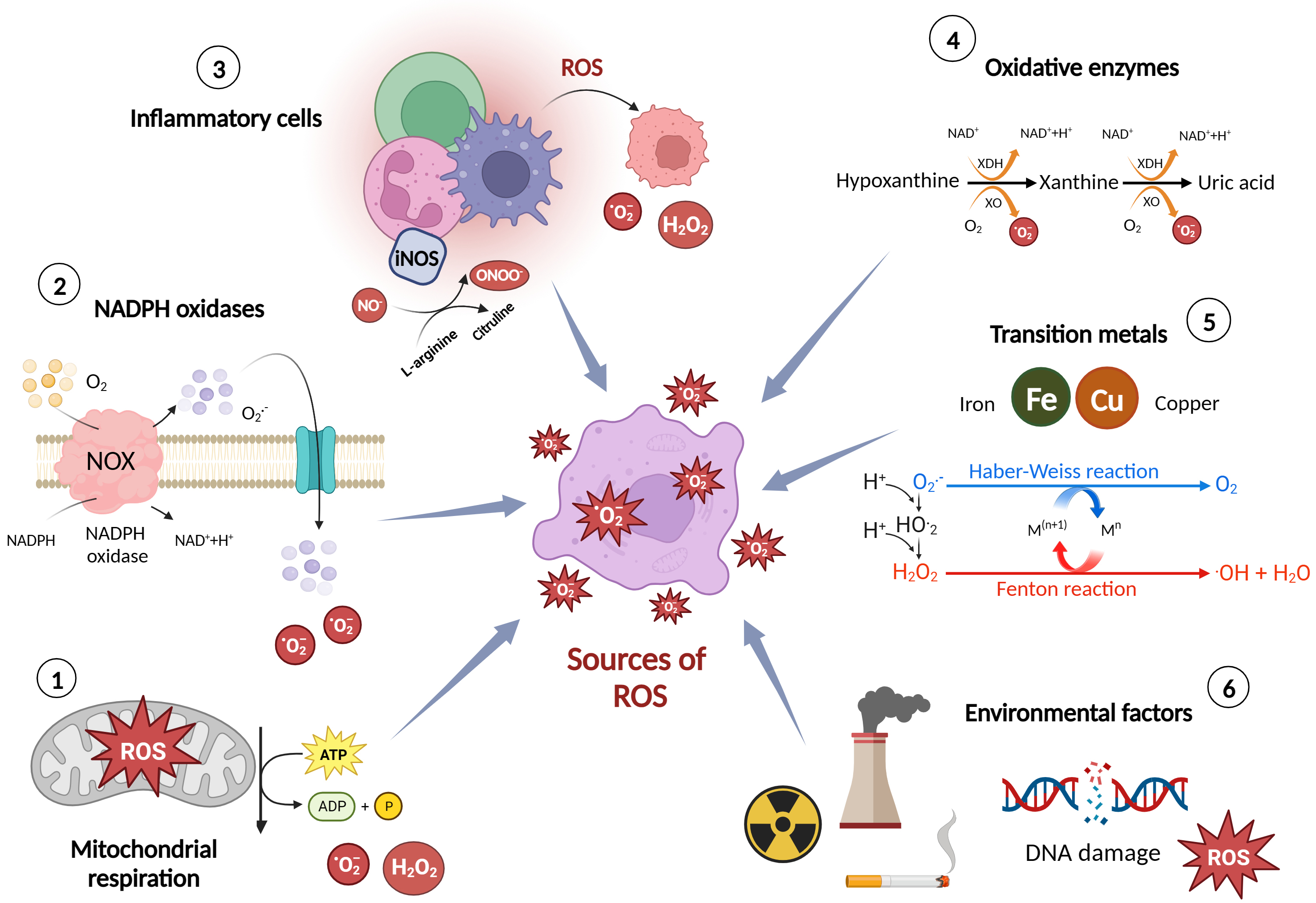

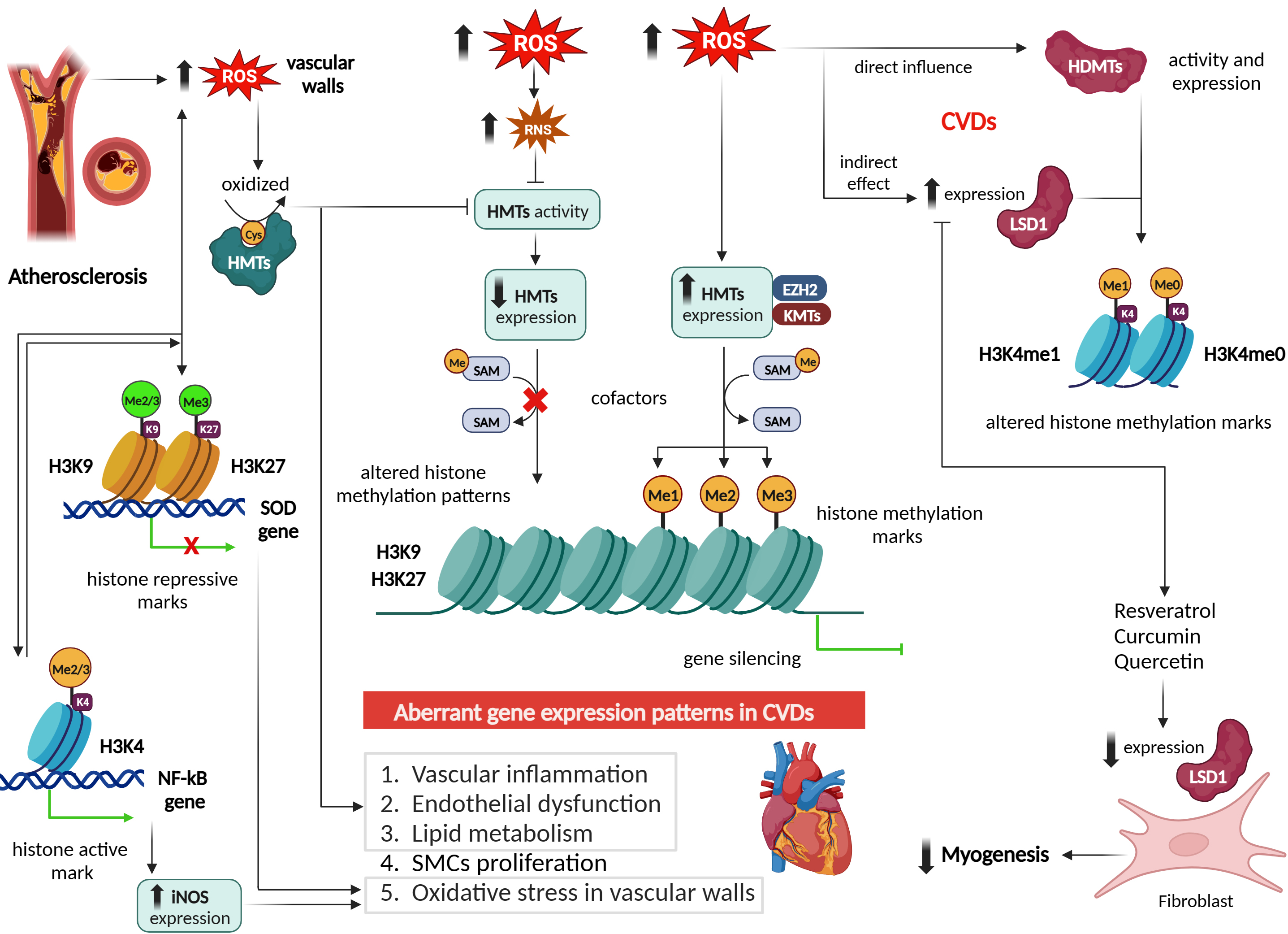

ROS are highly reactive molecules that are formed as natural by-products of cellular metabolism. They play essential roles in normal cellular functions and signalling pathways [10]. However, when their production exceeds the body’s antioxidant defense capacity, they can cause oxidative stress and damage to cells, tissues, and biomolecules. Here are some of the major sources and production mechanisms of ROS [11] (Fig. 1).

i. Mitochondrial respiration: Mitochondria, the powerhouse of the cell, generate

the majority of ROS during the process of oxidative phosphorylation. In this

process, electrons leak from the electron transport chain, leading to the

production of superoxide anion (O2•–) and hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) [11]. ii. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (NOX): NOX enzymes

are a family of membrane-bound enzymes that are involved in the regulated

production of ROS. They transfer electrons across biological membranes to

generate O2•– and other ROS. NOX enzymes are found in various

cell types, including endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells

(VSMCs), and immune cells [12]. iii. Inflammatory cells: Immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages

produce ROS as part of their defense mechanism against pathogens. These cells

contain specialized enzymes, such as myeloperoxidase and NOX, which generate ROS

to kill invading microorganisms [12]. iv. Oxidative enzymes: Certain enzymes, such as xanthine oxidase and cytochrome P450

enzymes, produce ROS as by-products of their enzymatic reactions. Xanthine

oxidase generates O2•– during the breakdown of purine

nucleotides, while cytochrome P450 enzymes produce ROS during various metabolic

processes [11]. v. Transition metals: Transition metals, such as iron and copper, can participate

in Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions, where they react with H2O2 to

produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH). These reactions can

occur in the presence of excess metal ions and elevated levels of H2O2 [11]. vi. Environmental factors: Exposure to environmental pollutants, such as air

pollutants, cigarette smoke [13], and radiation [14], can increase ROS

production. These external sources of ROS can lead to oxidative stress and

contribute to the development of various diseases, including CVDs [15].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Major sources and production mechanisms of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Figure was created with Biorender. Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; NOX, nitric oxide synthase; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ADP, Adenosine diphosphate; O2–, superoxide; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO–, nitrogen oxide; ONOO–, peroxynitrite; XO, xanthine oxidase; XDH, xanthine dehydrogenase.

It is important to note that while ROS are produced as natural by-products of cellular metabolism, their levels are tightly regulated by antioxidant defense mechanisms in healthy cells. Antioxidants, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), help neutralize ROS and maintain cellular redox balance. However, when there is an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses, oxidative stress occurs, leading to cellular damage and the development of various diseases, including CVDs [16, 17].

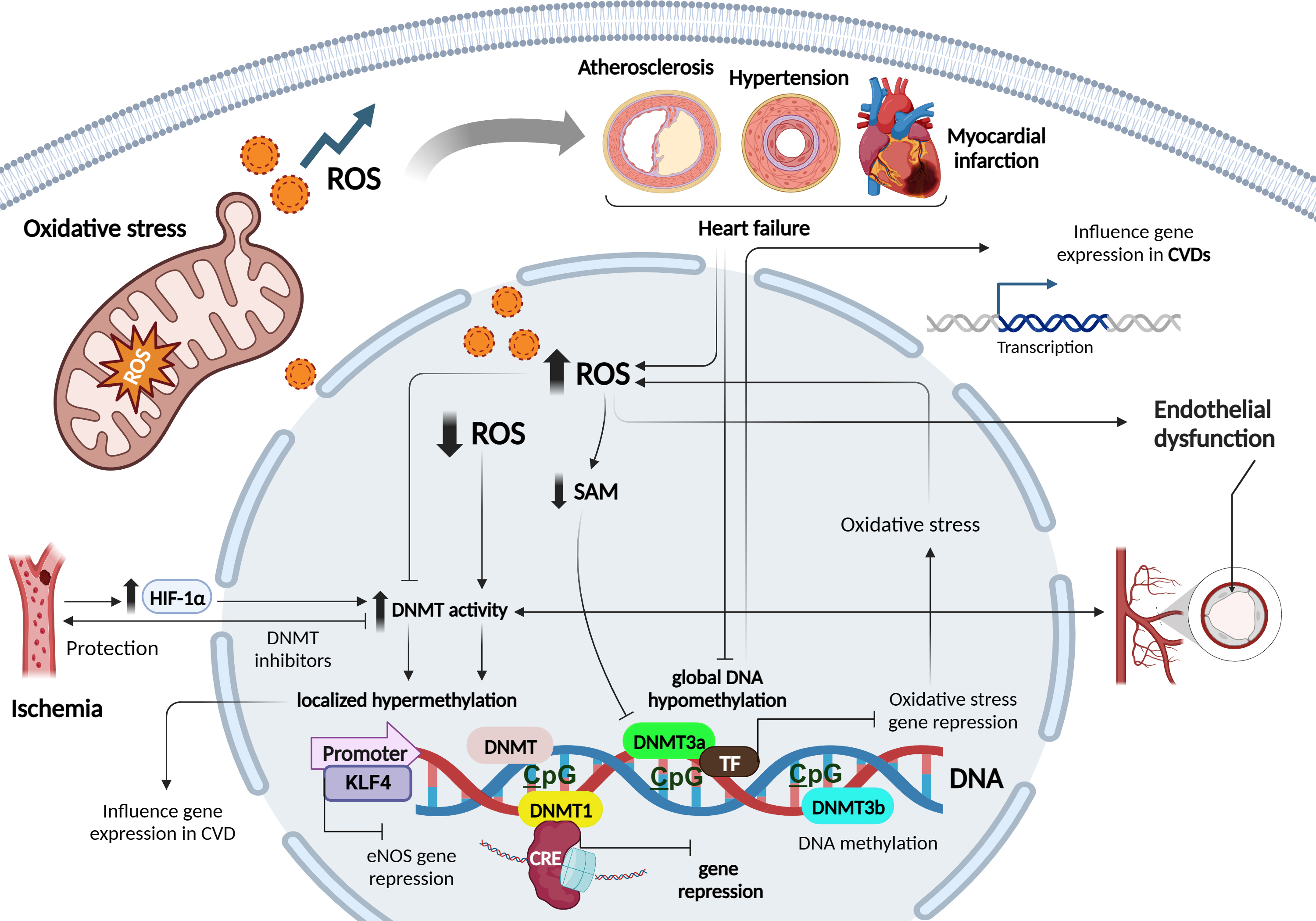

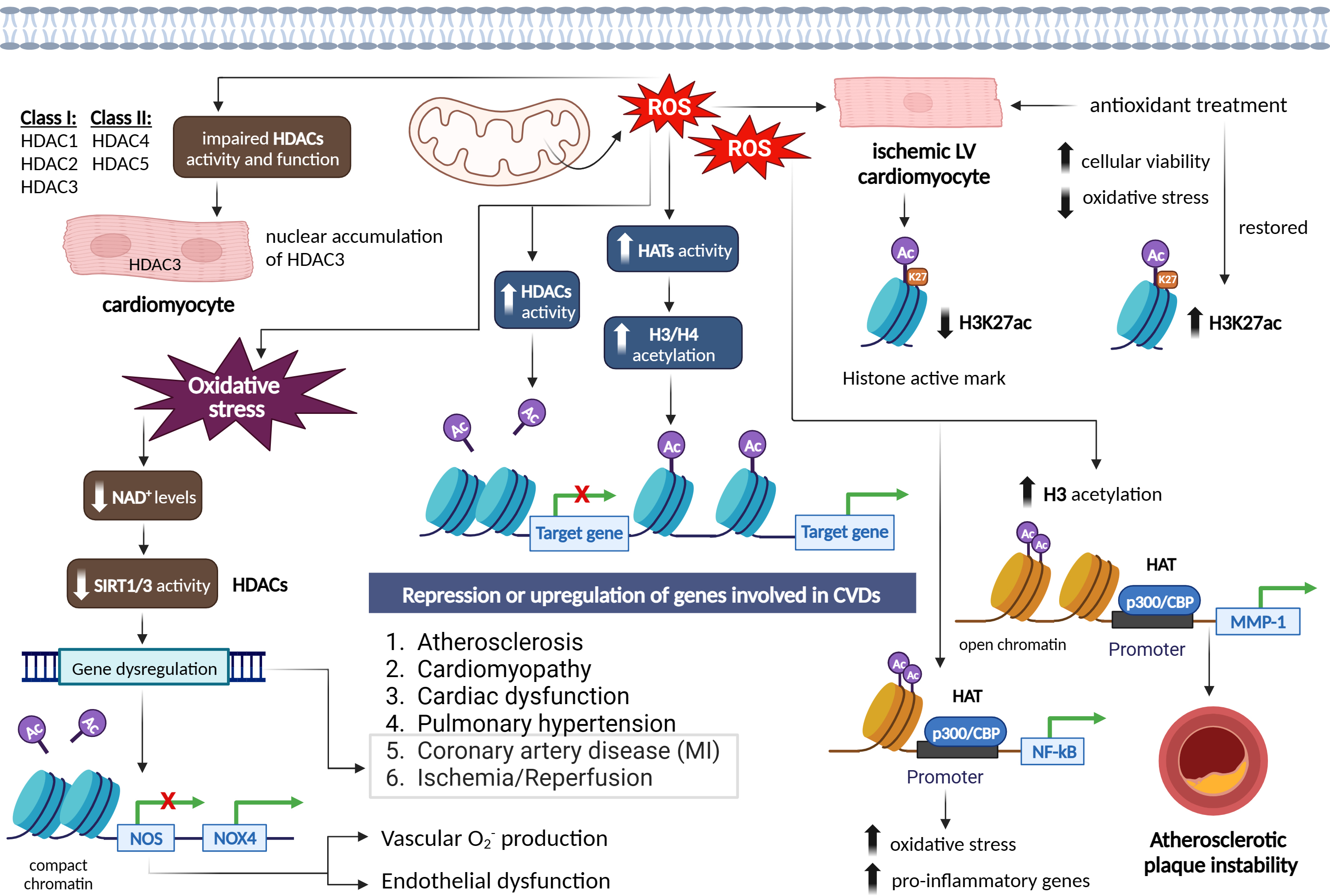

DNA methylation is an essential epigenetic modification that plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression and cellular function. It involves the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine base of DNA, primarily occurring in regions known as cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites, where a cytosine is followed by a guanine in the DNA sequence [18]. CpG methylation represses gene transcription by directly hampering the binding of transcription factors (TFs) to DNA, or indirectly via the recognition of methylated sites by chromatin-remodelling enzymes [18]. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), such as DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), DNMT3a, and DNMT3b process most DNA methylation. DNMT1 maintains the DNA methylation status during replication by detecting hypermethylated DNA. By contrast, the methyl-writing enzymes DNMT3a and DNMT3b are responsible for establishing a new methylation pattern to unmodified DNA, known as de novo methylation [18, 19] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

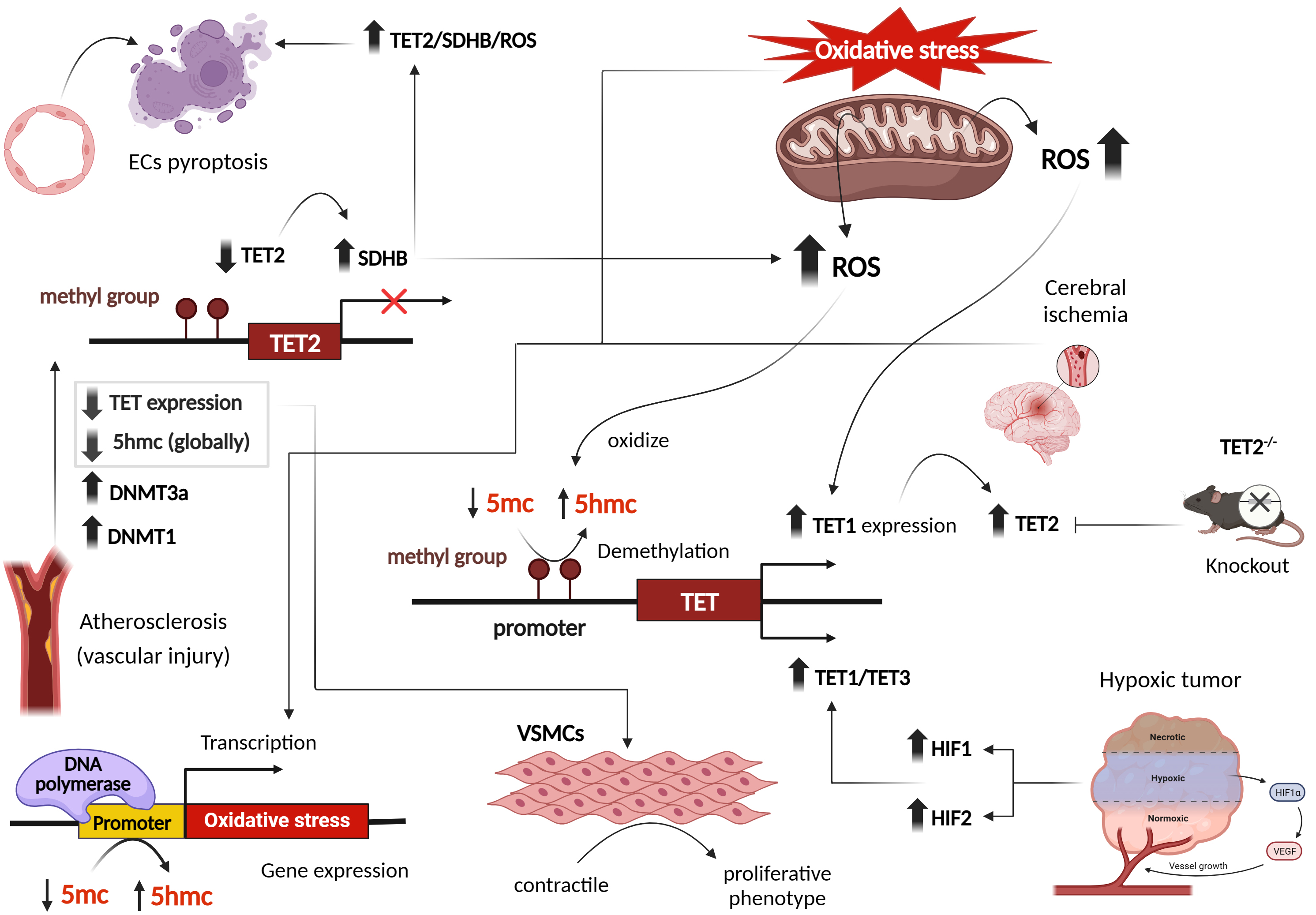

Fig. 2.

Role of oxidative stress and redox patterns on DNA

methylation mechanisms in cardiovascular diseases. Figure was created with

Biorender. Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; SAM, S-adenosyl

methionine; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; HIF-1

The relationship between ROS and DNA methylation is complex and can differ between local and global contexts. While elevated ROS levels have been associated with decreased global DNA methylation, primarily observed in cancer and CVDs, caution is necessary when generalizing these findings [7]. In local contexts, ROS can influence DNA methylation patterns in specific genes, contributing to localized changes in gene expression. For example, in cancer, oxidative stress can lead to hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes, thereby silencing their expression and promoting tumor progression [20, 21]. Conversely, hypomethylation of oncogenes can activate their expression, further driving cancer development [20].

ROS can alter DNA methylation by affecting DNMTs, enzymes responsible for adding methyl groups to DNA. ROS may directly oxidize the catalytic site of DNMTs or indirectly modulate their activity via redox signalling pathways. In CVDs, excessive ROS production in cardiovascular cells can directly affect DNMT activity, leading to changes in DNA methylation patterns [7]. Altered DNA methylation profiles have been observed in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, and HF [22]. Increased ROS can inhibit DNMT activity, resulting in global DNA hypomethylation, while elevated DNMT activity due to ROS can lead to localized DNA hypermethylation. These changes in DNA methylation can influence the expression of genes involved in crucial cardiovascular processes [23, 24].

Furthermore, ROS-induced changes in DNMT activity can affect the expression of antioxidant genes, reducing cellular antioxidant defenses and exacerbating oxidative stress [25]. This forms a feedback loop where ROS-induced changes in DNMT activity influence DNA methylation patterns, impacting gene expression networks involved in oxidative stress regulation [26].

ROS-mediated modulation of DNMTs also occurs through changes in cofactor

availability and recruitment to DNA. For instance, ROS can reduce the

availability of the DNMT cofactor S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), leading to reduced

DNMT activity and DNA hypomethylation [27]. On the contrary, ROS can stimulate

the expression of DNMTs, leading to increased DNA methylation. In experimental

ischemia models, the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor1-alpha

(HIF1

DNMT inhibitors have shown protective effects against ischemia or oxidative stress-induced injuries, underlining the therapeutic potential of targeting ROS-DNMT interactions [30]. Moreover, disturbed blood flow, often associated with increased ROS levels and endothelial dysfunction characteristic of atherogenesis, has been linked to elevated expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A, leading to DNA hypermethylation of CpG islands in various genes involved in mechanotransduction [7]. Notably, hypermethylation of the gene encoding the TF kruppel- like factor 4 (KLF4) has been shown to reduce endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression under these conditions [7]. While these findings suggest that ROS can induce specific hypermethylation by up-regulating DNMTs, other studies have indicated that ROS may also impact DNA methylation by modulating the recruitment of DNMTs to DNA, independent of changes in DNMT expression. For instance, ROS-induced Snail expression has been implicated in the recruitment of DNMT1 to the E-cadherin promoter, leading to hypermethylation [7].

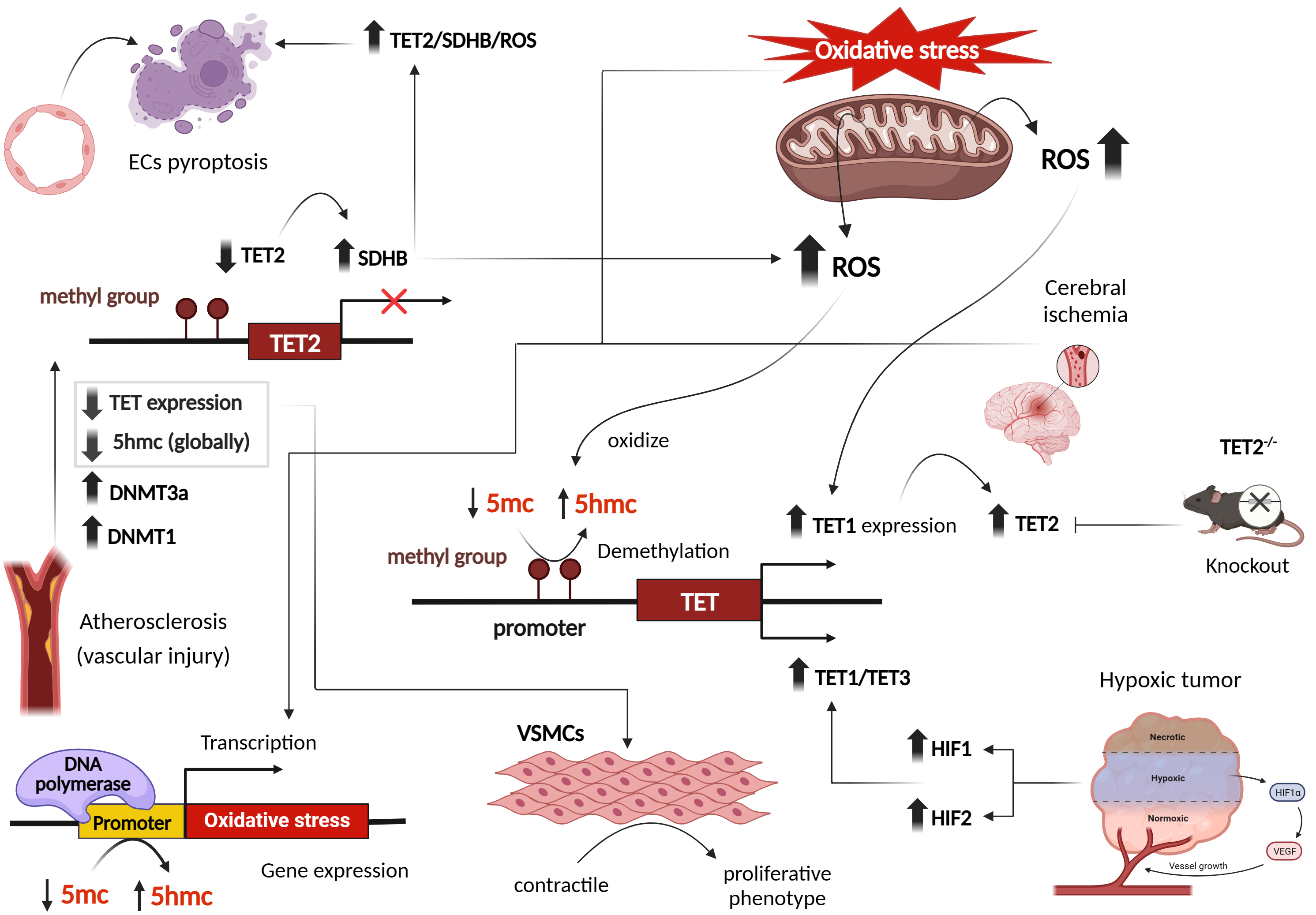

TET proteins, part of the 2-oxoglutarate oxygenase family, rely on cofactors like Fe2+ , oxygen, and ascorbate for their function. This enzyme family also includes prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), whose activity is reduced by hypoxia and ROS, primarily due to decreased availability of Fe2+ and ascorbic acid. Similarly, ascorbate enhances TET enzyme activity by interacting with its catalytic domain, resulting in increased levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). Thus, ROS-mediated depletion of these cofactors can significantly impact the function of TET enzymes, which are crucial for DNA demethylation and epigenetic regulation [31, 32, 33, 34].

In Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293) cells exposed to hydroquinones, an increase in ROS levels led to enhanced nuclear expression and activity of TET1, resulting in elevated 5hmC levels and reduced 5-methylcytosine (5mC) formation. Consequently, this ROS-induced demethylation affected various genes involved in cell cycle arrest and ROS detoxification [34]. Similar findings were observed in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia, where increased TET2 levels and 5hmC abundance were detected in ischemic regions [35]. Increased 5hmC modifications were particularly found at the promoter of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), accompanied by increased BDNF mRNA. However, these changes were absent in TET2 knockout mice, showing reduced BDNF mRNA and protein expression [35]. This emphasizes the role of TET proteins may play in response to oxidative stress.

A review by Tan et al. [36] on the modulation of DNA methylation by ROS through the regulation of TET family members showed that TET proteins oxidize 5mC to 5hmC, thereby influencing DNA methylation patterns. Notably, double-knockout mice lacking the antioxidant enzymes GPx-1 and GPx-2 showed increased levels of 5hmC, suggesting a complex interplay between oxidative stress, ROS formation and DNA methylation pathways [37].

Moreover, studies have linked hypoxic conditions to alterations in TET protein

levels and 5hmC marks through hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs). Under hypoxia,

increased expression of TET1 and TET3, mediated by HIFs, led to global or

localized elevation of 5hmC levels in different cancer cell lines [38, 39, 40]. Since

hypoxic cells respond by inducing a transcriptional program regulated by

oxygen-dependent dioxygenases that require Fe2+ and alpha-ketoglutarate

(

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effect of oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species on transcriptional patterns of DNA ten-eleven translocation (TET) methylcytosine dioxygenases, in cardiovascular and other disease phenotypes. Figure was created with Biorender. Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; TET, ten-eleven translocation; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells; SDHB, succinate dehydrogenase B; 5hmc, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; ECs, endothelial cells; 5mc, 5-methyl cytosine.

Studies examining atherosclerosis and vascular injury revealed reduced 5hmC content and TET2 expression. Interestingly, 5hmC and TET2 function as a switch in transforming VSMCs from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype [44]. Gene expression profiles during oxidative stress have demonstrated a global decrease in 5hmC marks [37]. However, specific hydroxymethylated regions associated with oxidative stress were identified on 5hmC-enriched sites [37] (Fig. 3). Endothelial cells (ECs) are also impacted by oxidative stress. Several studies have shown that ECs exposed to H2O2 display decreased TET activity and 5hmC content, while levels of DNMT3A, DNMT1, and 5mC are increased [45, 46, 47]. Similar observations were seen in kidneys subjected to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injuries, as well as in patients with gestational diabetes and preeclampsia, where reduced 5hmC levels were observed [26, 46]. In an ischemic mouse brain, reduced 5hmC levels were observed at intragenic islands and the transcription start site, while increased 5hmC marks were detected in exons, facilitating the expression of neuroprotective genes. This reveals distinct hydroxymethylation patterns [35].

Beyond I/R and vascular injuries, mitochondrial metabolites including fumarate and succinate, associated with ROS and mitochondrial metabolism, can also suppress TET activity. A Study reported that hypoxia-induced reductions in TET activity and 5hmC marks contribute to gene promoter hypermethylation in hypoxic tumors [48]. However, TET activity remains inhibited at oxygen concentrations below or equal to 2%, indicating a broad range of oxygen levels at which TET activity is maintained [48]. Hypoxia-induced TET upregulation and 5hmC marks exhibit cell type-specific responses dependent on TET abundance and oxygen availability [49] (Fig. 3).

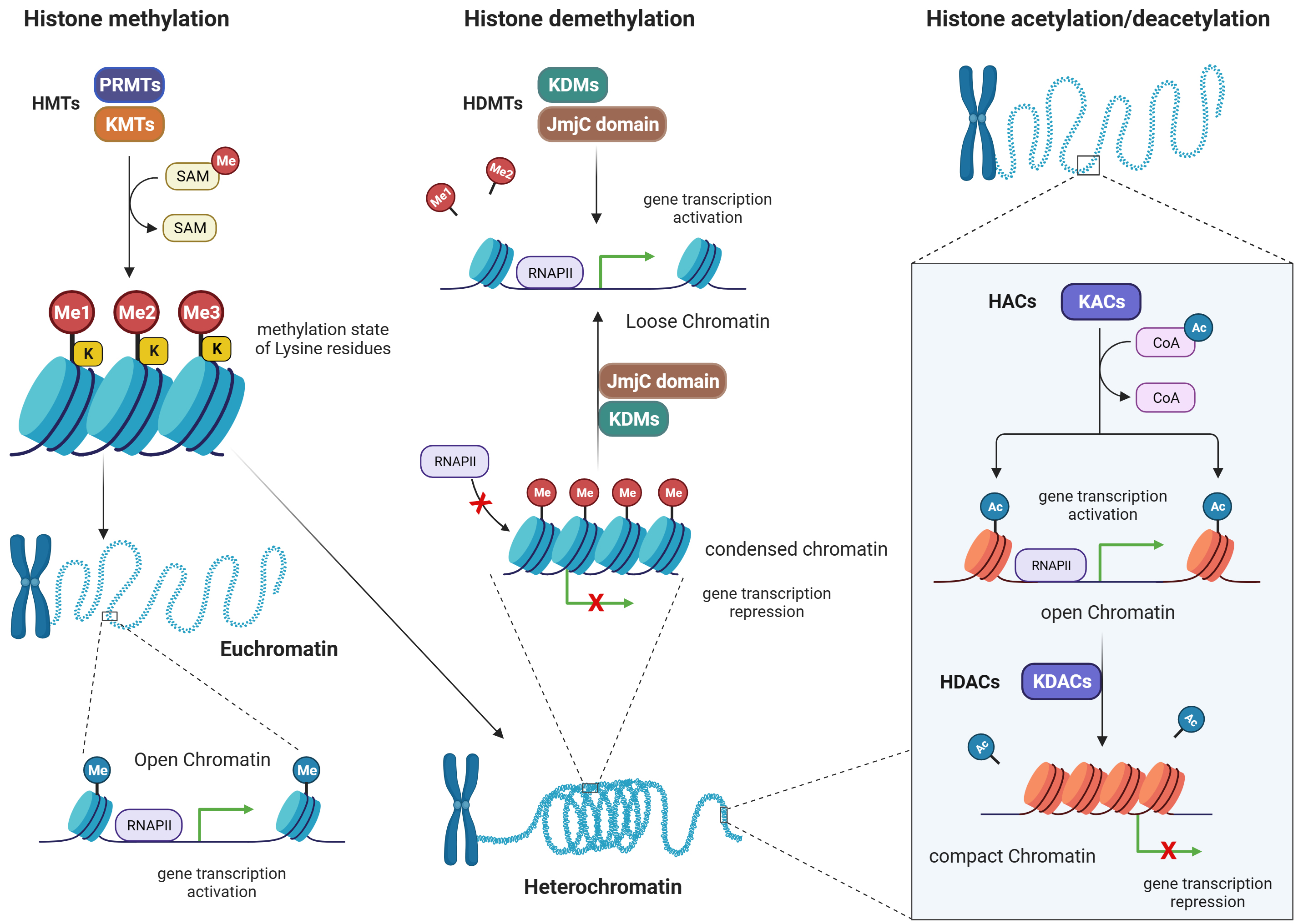

Post-translational modifications of histones, namely methylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation, are chemical modifications to histone tails. These modifications may affect the organization of chromatin architecture and gene expression patterns [4, 50]. Among these modifications, methylation and acetylation are the two modifications most affected by ROS, they will be overviewed in the following sections.

Histone methylation is a post-translational modification that is carried out by methyltransferases (MTs), while the removal of methyl groups from histones is mediated by demethyltransferases (DMTs) [51]. Condensation of chromatin structure happens because of methylation of histone proteins. This is associated with either activation or repression of gene transcription, based on which amino acid residues are being methylated [52, 53]. For example, MTs are responsible for adding methyl groups (-CH3) to specific amino acids on histone proteins. There are two major families of MTs involved in histone methylation: lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) (Fig. 4).

i. Lysine methyltransferases (KMTs): KMTs catalyze the transfer of a methyl group

from the methyl donor molecule SAM to specific lysine residues on histones.

Different KMTs have preferences for specific lysine residues and can add one,

two, or three methyl groups to the target lysine, resulting in mono-, di-, or

trimethylation, respectively. The methylation state of lysine residues can have

diverse functional consequences for gene expression and cellular processes [52]. ii. Arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs): PRMTs add methyl groups to specific

arginine residues on histones. Like KMTs, PRMTs also utilize SAM as the methyl

donor. Arginine methylation can occur in different states, including

monomethylation, symmetric dimethylation, and asymmetric dimethylation, depending

on the specific PRMT involved. Arginine methylation is involved in gene

expression regulation and other cellular processes, like lysine methylation [53].

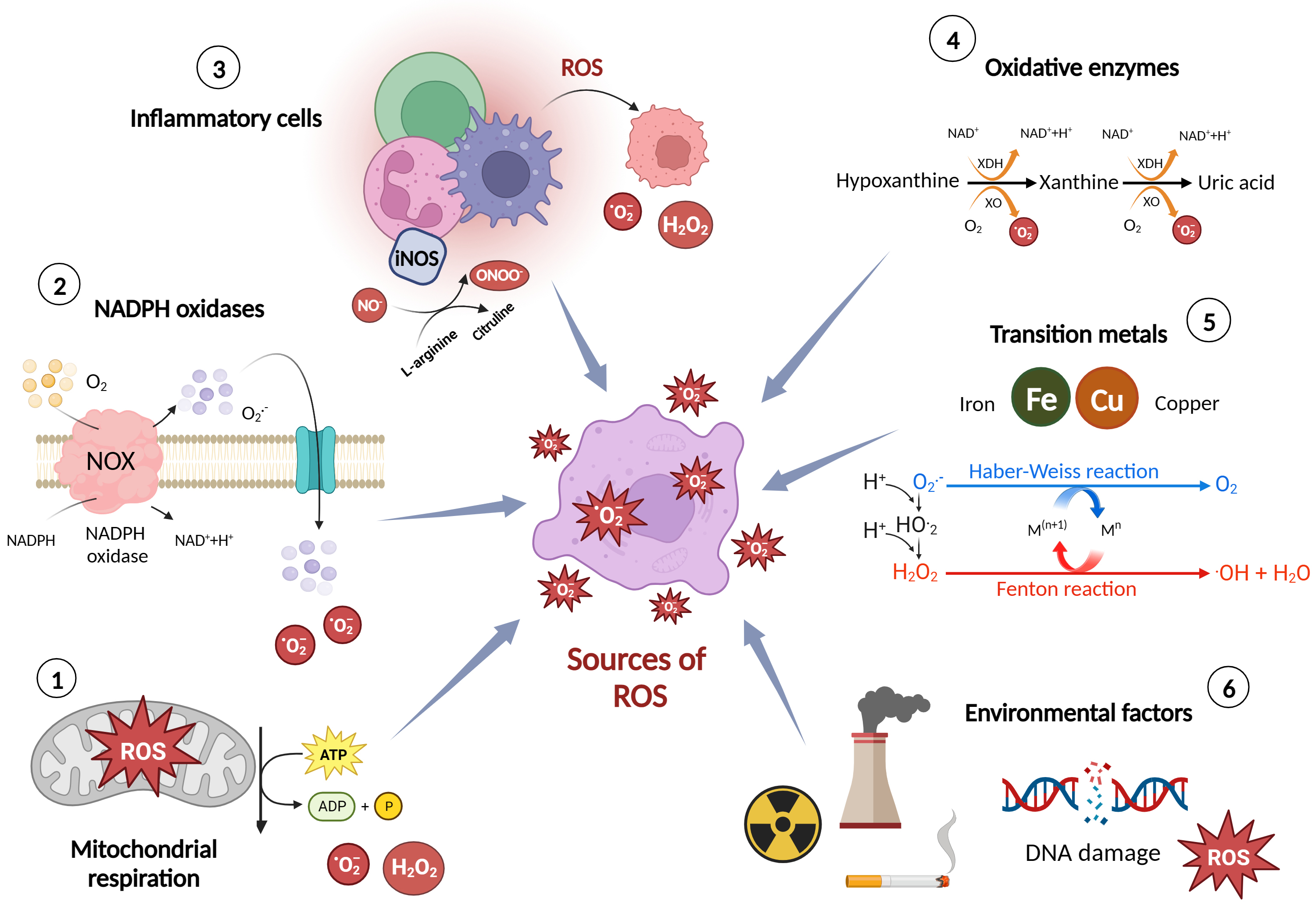

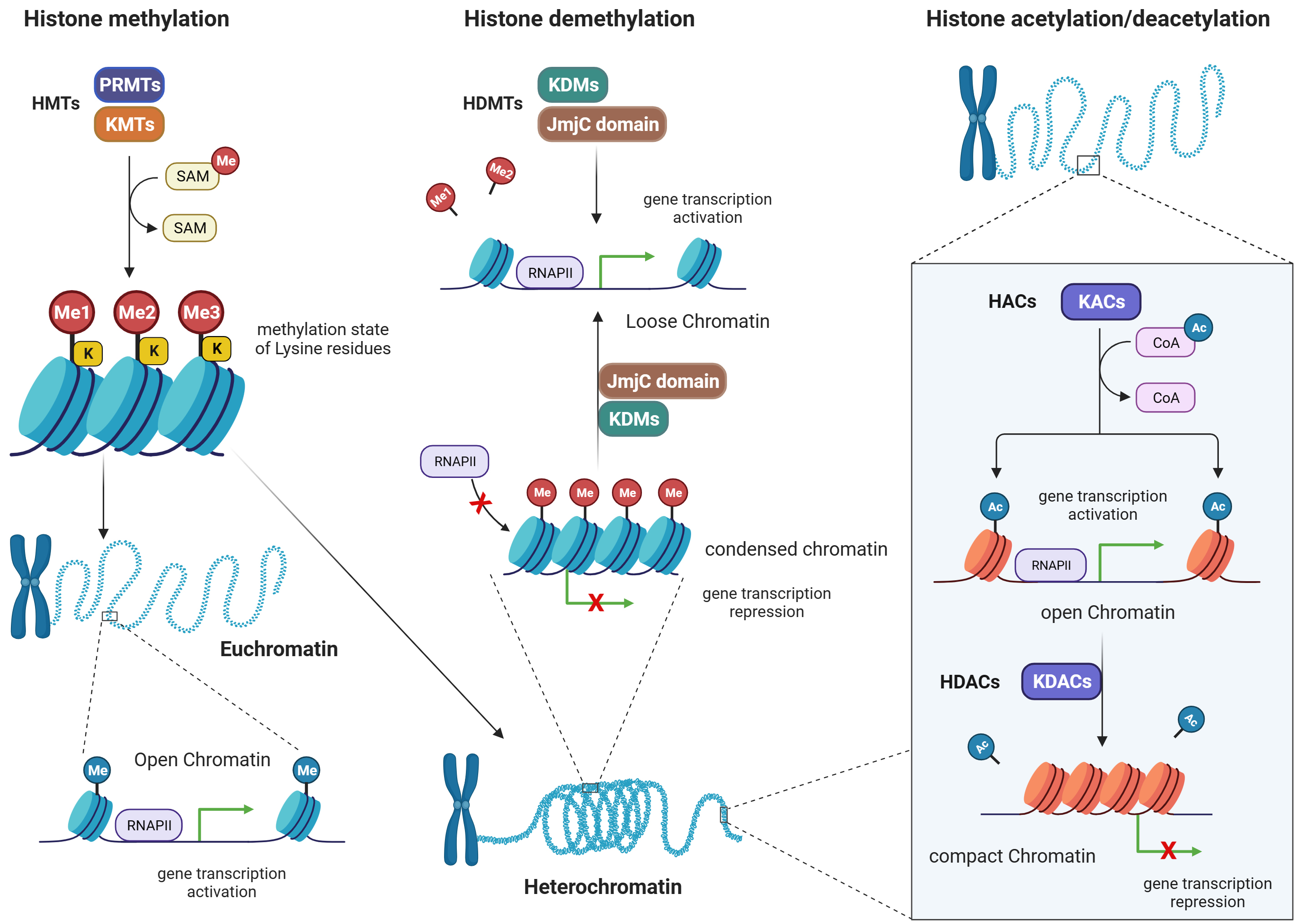

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Histone methylation/demethylation, and histone acetylation/deacetylation patterns. Figure was created with Biorender. Abbreviations: HMTs, histone methyltransferases; PRMTs, arginine methyltransferases; KMTs, lysine methyltransferases; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine; HDMTs, histone demethyltransferases; KDMs, lysine demethyltransferases; JmjC, jumonji C domain- containing demethylases; RNAP, RNA polymerase; HACs, histone acetylases; KACs, lysine acetylases; KDACs, lysine deacetylases; RNAPII, RNA polymerase II; HDACs, histone deacetylases; CoA, coenzyme A.

Demethyltransferases (DMTs) are enzymes responsible for removing methyl groups from histones, thus reversing the methylation marks. There are two major families of DMTs involved in histone demethylation: lysine-specific demethylases (KDMs) and Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing demethylases.

i. Lysine-specific demethylases (KDMs): KDMs catalyze the removal of methyl groups

from lysine residues on histones. They employ a variety of mechanisms, including

oxidative reactions, to achieve demethylation. KDMs exhibit specificity for

methylation states and lysine residues. For example, some KDMs are specific for

removing mono- or di-methyl groups from specific lysine residues, while others

can remove trimethyl marks [54]. ii. Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing demethylases: JmjC domain-containing

demethylases are a family of DMTs that use an iron (Fe2+)- and

alpha-ketoglutarate (

The balance between MT and DMT activities is crucial for maintaining the dynamic and precise regulation of histone methylation patterns, which are essential for gene expression and cellular function. Dysregulation of these enzymes can lead to aberrant gene expression and contribute to CVDs [56, 57].

Histone methylation is a heterogeneous process with various sites and distributions, leading to euchromatin or heterochromatin and activating or repressing gene transcription [58]. A large body of evidence supports the notion that histone methylation is essential in maintaining genome integrity, transcriptional gene regulation, and cancer metastasis. It also plays a critical role in heart development, and the pathophysiology of HF [59].

Studies have reported that ROS can alter histone methylation marks such as

active marks H3K4me2/3 and repressive marks H3K9me2/3 and H3K27me3 [45].

Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) exposed to short and long-term of

effect of H2O2 exhibited an increased level of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3.

This effect was mediated by reduction of cofactors Fe2+ and

However, these mechanisms work bidirectionally, where histone methylation can

lead to overproduction of ROS, either by activating or by repressing the

transcription of prooxidants or antioxidants, respectively. For example,

methylation of H3K9 and its binding at the promoters of prooxidants such as SOD,

cause excessive ROS production in vascular walls. While increased H3K4

methylation at the promoter region of nuclear factor kappa B

(NF-

Increased methylation of H3K4 on the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and kelch like ECH associated protein 1 (Keap1) promoters was also addressed in the context of diabetic microvascular pathology (Fig. 5), showing a modulating effect on intracellular antioxidant glutathione (GSH) biosynthesis [63, 64]. Nrf2 is a TF involved in regulating the expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (Gclc), an enzyme crucial for GSH synthesis. In diabetes, however, Nrf2 binding at the antioxidant response element 4 (ARE4) is reduced [63, 64]. Mishra et al. [63, 64] investigated the role of epigenetic modifications of H3K4 in the diminished Nrf2 binding at Gclc-ARE4 in diabetic retinopathy. Their results from chromatin immunoprecipitation from diabetic rat retinas showed an increase in the H3K4me2 signature at Gclc-ARE4, while H3K4me3 and H3K4me1 levels were decreased. Transfecting retinal ECs with lysine-specific demethylase (LSD1) small interfering RNA (siRNA) reversed the glucose-induced decrease in H3K4me1 at Gclc-ARE4, restoring Nrf2 binding at Gclc-ARE4 and increasing Gclc transcripts. These findings suggest that the histone methylation signature at Gclc-ARE4 regulates the Nrf2–Gclc–GSH cascade and targeting this epigenetic modification could help inhibit or slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy [63]. Epigenetic modifications at the Keap1 promoter, a cytoplasmic repressor of Nrf2, were investigated in the context of diabetic retinopathy using streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and retinal ECs. The study revealed that in hyperglycemic conditions, there was an increase in the binding of the TF Sp1 at the Keap1 promoter, accompanied by an enrichment of the H3K4me1 signature at this site. Additionally, the methyltransferase enzyme Set7/9 (SetD7) was activated in retinal ECs. Transfecting these cells with SetD7 siRNA prevented the hyperglycemia-induced increase in Sp1 binding at the Keap1 promoter, thereby suppressing Keap1 expression. This intervention also ameliorated the decrease in Nrf2-regulated antioxidant genes [64].

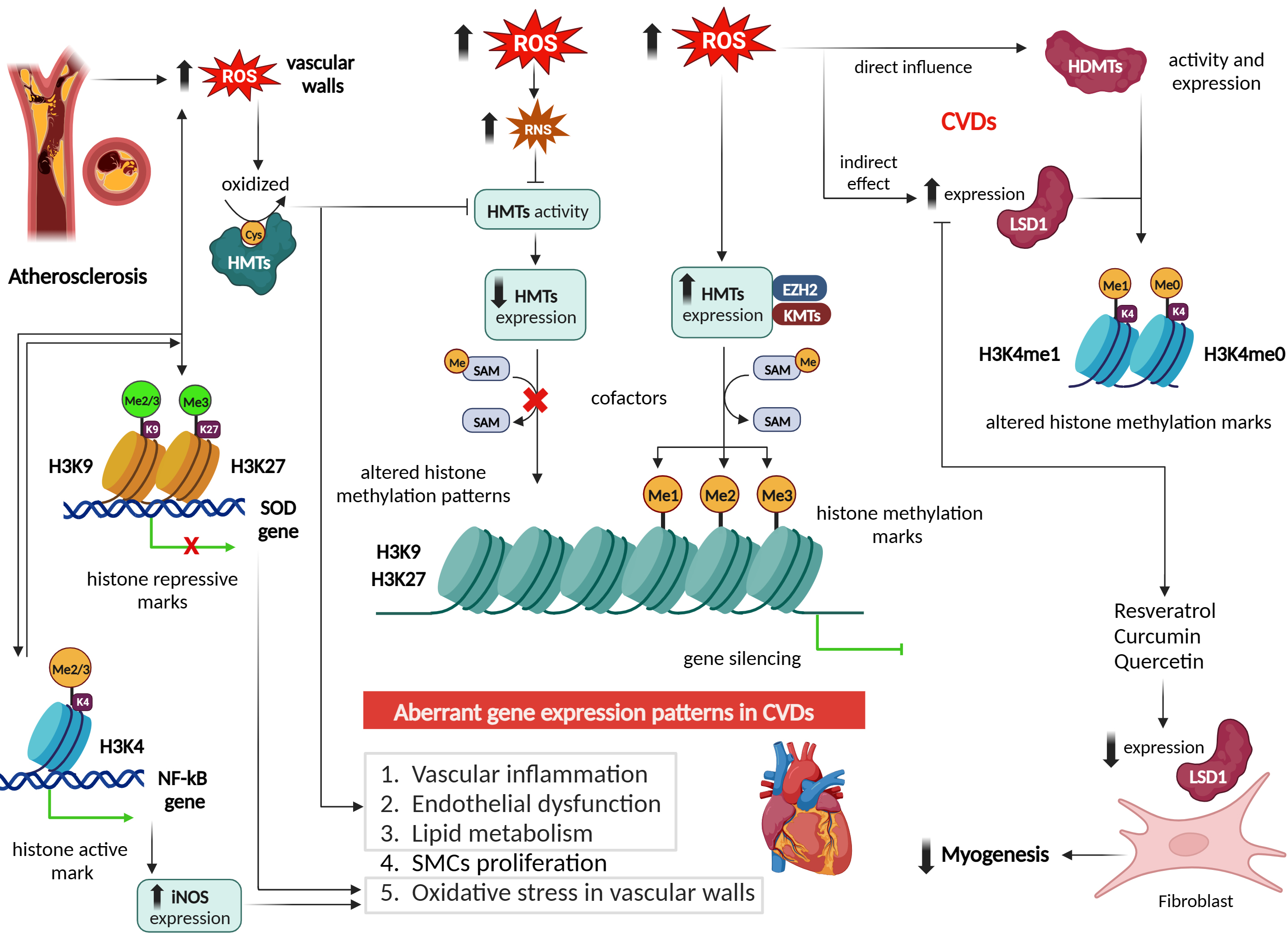

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effect of reactive oxygen species on histone

methylation/demethylation patterns and epigenetic regulation in cardiovascular

diseases. Figure was created with Biorender. Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen

species; HMTs, histone methyltransferases; H3K9, histone 3 lysine 9; H3K27,

histone 3 lysine 27; SOD, superoxide dismutase; H3K4, histone 3 lysine 4; NF-

Consistent results were observed in the retinas of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, even after cessation of hyperglycemia. Notably, the increase in Sp1 binding at the Keap1 promoter, ongoing methylation of the Keap1 promoter, increased Keap1 expression, and decreased expression of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant genes persisted despite normalization of blood glucose levels. These findings highlight the pivotal role of epigenetic regulation at the Keap1 promoter in influencing the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway in diabetic retinopathy [64].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that ROS can influence HMT activity and histone methylation patterns in CVDs [65, 66, 67]. ROS can directly oxidize critical residues within HMTs, leading to alterations in their enzymatic activity. For example, in atherosclerosis, increased ROS levels can oxidize cysteine residues within HMTs, resulting in the inhibition of their MT activity [68]. This inhibition can disrupt the normal regulation of genes involved in vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and lipid metabolism, contributing to disease progression [56] (Fig. 5).

Moreover, ROS can indirectly modulate HMT activity by affecting the availability of cofactors required for their function. In CVDs, ROS can promote the production of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as peroxynitrite (ONOO–), which can oxidize and inactivate enzymes involved in SAM biosynthesis, the methyl donor for HMTs [69]. Consequently, reduced levels of SAM impair HMT activity, leading to altered histone methylation patterns and subsequent changes in gene expression associated with CVDs [7] (Fig. 5).

In line with this, a study by Li et al. [70] demonstrated that arsenic induces serine 21 phosphorylation of the EZH2 protein in BEAS-2B cells via JNK, STAT3, and Akt pathway activation, with ROS playing a crucial role. Pretreatment with the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) inhibited both EZH2 phosphorylation and kinase activation, supporting ROS involvement. H2O2, a key ROS, also induced EZH2 phosphorylation and activation of JNK, STAT3, and Akt. Moreover, arsenic and H2O2 triggered EZH2 translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. These findings indicate that ROS-driven oxidative stress is central to arsenic-induced EZH2 phosphorylation [70]. Furthermore, it is well established that exposure to ROS can lead to DNA damage and activation of DNA damage response [71]. In this context, a study by Takahashi et al. [72] demonstrated that, in senescent cells, the DNA damage response triggers the proteasomal degradation of H3K9 methyltransferases G9a and GLP through Cdc14B- and p21-mediated activation of the APC/CCdh1 ubiquitin ligase. This degradation results in decreased H3K9 dimethylation and increased expression of Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, which are key components of senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Collectively, these findings underscore the critical role of the APC/CCdh1-G9a/GLP axis in integrating the DNA damage response with epigenetic regulation to drive senescence-associated gene expression [72]. This integration may have a significant impact on CVDs, given the critical role that cellular senescence plays in shaping cardiovascular phenotypes [71]. It is crucial to recognize that the relationship between ROS and HMTs is bidirectional. On one hand, ROS can impact HMT activity and expression; on the other hand, alterations in HMT activity through various mechanisms can also lead to increased ROS production. A recent study revealed that EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 is a key epigenetic driver of hyperglycemia- induced ROS generation and endothelial dysfunction in HAECs and aortas from db/db mice, while its inhibition may attenuate oxidative stress and prevent vascular disease in diabetes setting [57].

Furthermore, ROS-mediated alterations in histone methylation can have specific

effects on key genes and pathways associated with CVDs [2]. For instance,

ROS-induced dysregulation of HMTs has been linked to the aberrant expression of

genes involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and

smooth muscle cell proliferation, all of which contribute to the development and

progression of CVDs [3] (Fig. 5). A study by El-Osta el al. [73] it was

demonstrated that brief exposure of aortic ECs to hyperglycemia induces

persistent epigenetic changes in the promoter of the NF-

In summary, ROS play a significant role in modulating HMTs and histone

methylation patterns in CVDs. ROS can directly oxidize HMTs, modulate the

availability of cofactors, and influence HMT expression and stability, leading to

dysregulated gene expression associated with cardiovascular pathophysiology. On

the other hand, histone methylation can also lead to ROS production in CVDs, such

as by repressing or activating antioxidant or prooxidant genes. For example, H3K9

methylation and binding at the promoter region of SOD causes excessive ROS

formation in vascular walls. Increase methylation of H3K4 at the promoter of

NF-

Emerging evidence suggests that ROS may play a role in histone methylation regulation by influencing the expression and activity of HDMs, while HDMs can also lead to overproduction of ROS [75]. For instance, in the setting of obesity, the demethylase JMJD2C decreases H3K9me2/me3 signatures at p66𝑆ℎ𝑐 promoter, leading to overproduction of mitochondrial ROS in visceral fat arteries [56]. Vascular ECs (VECs) exposed to hypoxia-reoxygenation, lysine demethylase 3A (KDM3A) interacts with Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1) to decrease H3K9me2 binding to the promoters of NOX2 and NOX4, thereby activating the expression of these genes and inducing overproduction of ROS, contributing to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI) [76]. In one study on ECs exposed to hyperglycemia, it was revealed that LSD1 knockdown lead to an increase in H3K4me1 at the promoters of NOX4 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) genes and ROS production, suggesting that LSD1 is a key factor in endothelial dysfunction and an important target in reducing diabetes-associated endothelial dysfunction [77]. Increased levels of LSD1 have been observed in CVDs such as cardiomyopathy and hypertension, resulting in changes to H3K4me1 and H3K4me0 methylation marks. This suggests that ROS may influence LSD1 expression and contribute to these conditions [17, 78] (Fig. 5).

Interestingly, natural polyphenols like resveratrol, curcumin, and quercetin, which are known for their ability to lower ROS levels, have also been shown to inhibit LSD1 activity in C2C12 fibroblasts [79], subsequently reducing myogenic expression and differentiation [80]. Despite these insights, a direct connection between ROS and the regulation of LSD1 in cardiovascular events has not yet been established. Additionally, LSD1 activity is linked to H2O2 bursts, which can lead to the formation of 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) and trigger the activation of base excision repair enzymes for DNA repair [81]. These findings suggest a complex interplay, where ROS may influence HDMTs like LSD1, while HDMTs themselves could contribute to ROS generation [81]. Further research is needed to thoroughly investigate and clarify these interactions.

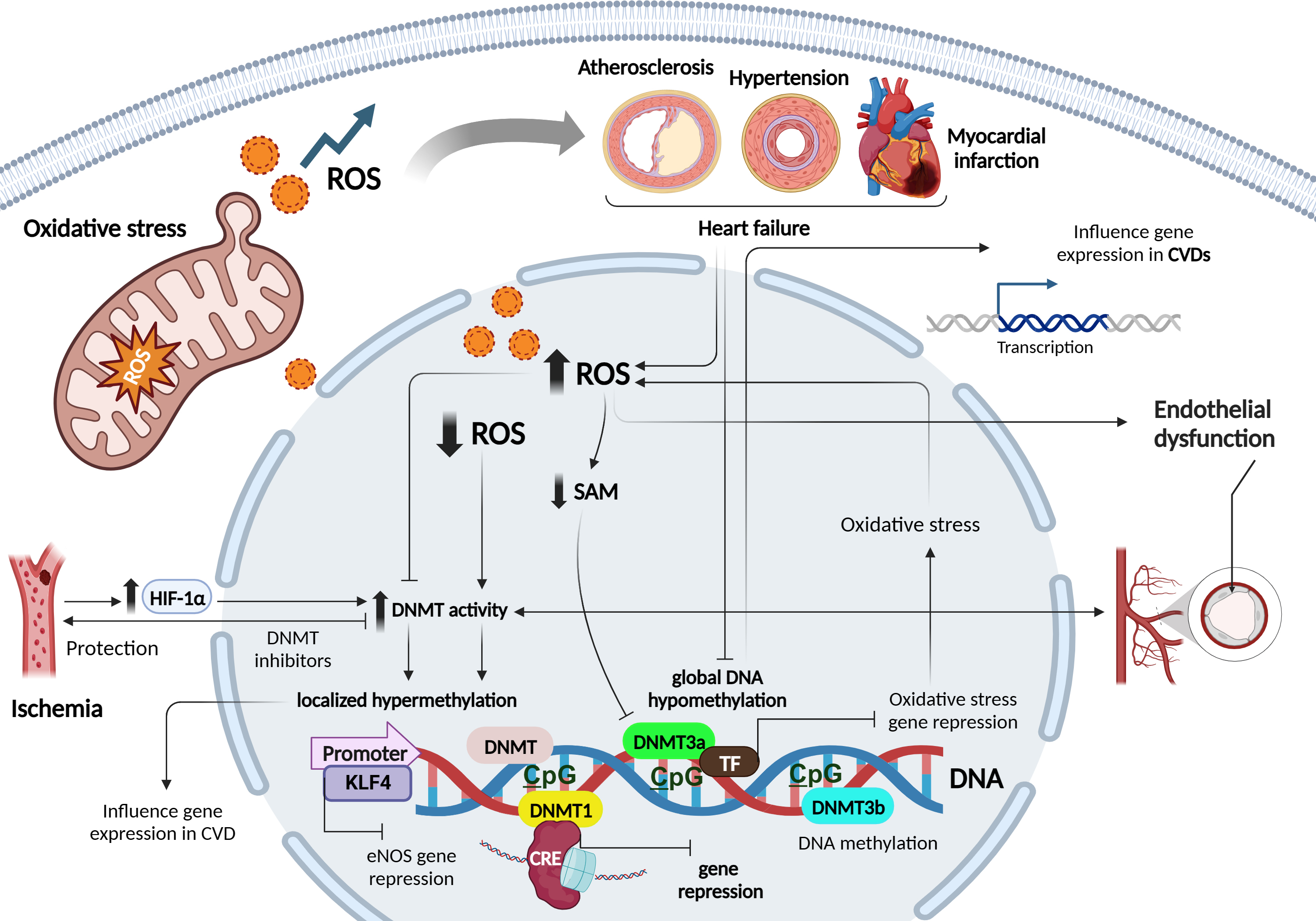

Histone acetylation is a reversible post-translational protein modification process by lysine acetyltransferases (KATs), where an acetyl group is added to histone proteins, which engage in packaging DNA [82]. This modification neutralizes the positive charge of lysine residues on histones, loosening their interaction with DNA and other proteins [82]. As a result, the chromatin structure becomes more open, allowing easier access for regulatory proteins and TFs to bind to DNA. This modification plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression, as acetylated histones are associated with active transcription [82, 83]. Conversely, removing the acetyl group, carried out by histone deacetylases (HDACs), leads to a more compact chromatin structure and gene silencing [84]. Histone acetylation is an important mechanism in epigenetics that influences cellular processes and is implicated in CVDs including atherosclerosis, MI, and cardiomyopathy [85]. Modulating histone acetylation has potential therapeutic applications in CVDs, where increased acetylation is associated with active gene transcription and deacetylation associated with gene repression [85] (Fig. 6).

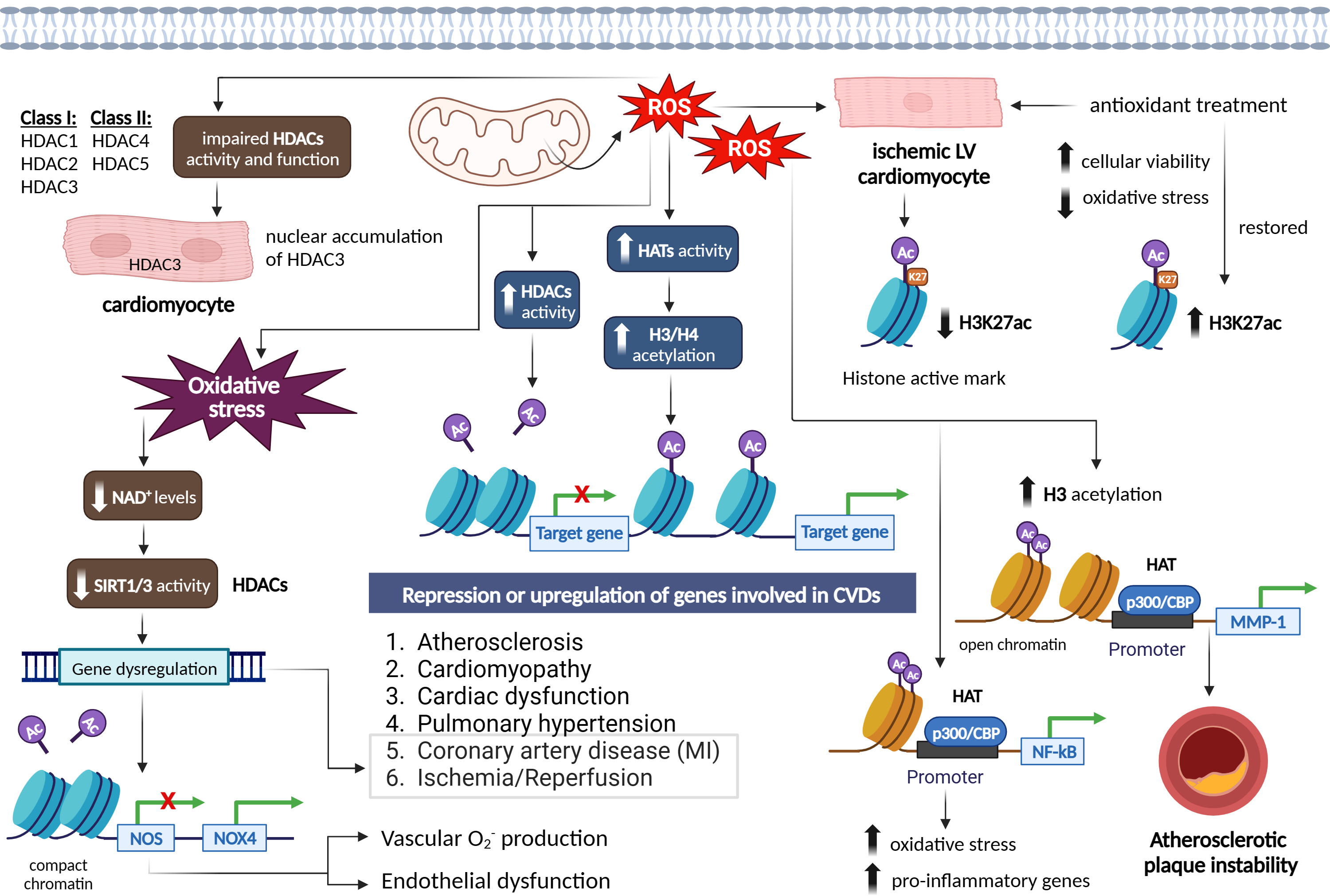

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Epigenetic signatures via the effect of reactive oxygen species

on histone acetylation/deacetylation patterns in different cardiovascular

diseases and vascular function. Figure was created with Biorender.

Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; HATs, histone acetyltransferases;

HDACs, histone deacetylases; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; SIRT,

sirtuin; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; H3K27ac, histone 3

lysine 27 acetylation; NF-

Histone acetylation is crucial for the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. This process is regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), which enhance transcription by adding acetyl groups that reduce the interaction between histones and DNA, and by HDACs, which repress transcription by removing these acetyl groups [85]. The relationship between ROS and histone acetylation is complex, as ROS can influence not only the acetylation status of histones, but also the activity of key regulatory proteins involved in cell survival and death [86]. In this context, de la Vega et al. [86] demonstrated that moderate concentrations of ROS act as essential signaling molecules, while excessively high levels can lead to cell death. Their research identified ROS-induced acetylation of the pro-apoptotic kinase HIPK2 as a critical mechanism that determines a cell’s sensitivity or resistance to ROS-mediated cell death [86]. At normal ROS levels, HIPK2 undergoes sumoylation, allowing it to maintain its association with HDAC3 and remain in a non-acetylated state. However, elevated ROS levels disrupt this sumoylation, decreasing HIPK2’s interaction with HDAC3 and resulting in its acetylation [86]. Reconstitution experiments revealed that HIPK2-regulated genes contribute to reduced ROS levels. Notably, a HIPK2 mutant that cannot be acetylated increased ROS-induced cell death, while an acetylation-mimicking variant promoted cell survival even under high oxidative stress [86].

In relation to cardiovascular conditions such as cardiac hypertrophy, coronary artery disease (CAD), and cardiac dysfunction, histone acetylation changes have been observed [87, 88]. It is worth noting that increased levels of ROS have generally been linked to increased histone acetylation, although some studies have reported conflicting results [89, 90]. Increased cellular and mitochondrial ROS under ischemic condition in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (CMCs) significantly reduced the histone active mark H3K27ac, however, treatment with antioxidants, restored H3K27 acetylation accompanied with improved cellular viability and reduced oxidative stress through regulation of HMGN1 gene and protein expression [52, 53] (Fig. 6). In regard to atherosclerosis, EC activation induced by hyperlipidemia is a critical initial step in monocyte recruitment and the progression of atherosclerotic disease [91]. Li et al. [91] discovered that Interleukin-35 (IL-35) was markedly elevated in the aortas and plasma of an apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout mouse model of atherosclerosis, as well as in plasma samples from hypercholesterolemic patients. They observed that IL-35 exerted an inhibitory effect on mitochondrial ROS-induced acetylation of histone H3 lysine 14 (H3K14), leading to the suppression of EC activation and effectively halting the progression of atherosclerosis [91].

ROS have been found to enhance HAT activity in various cell types, leading to

increased acetylation of histones H3 and H4 [92]. This increase in acetylation has

been associated with the upregulation of genes involved in CVDs. For instance,

increased ROS levels resulting from the overexpression of SOD2 facilitate H3

acetylation and the recruitment of the HAT p300/CBP to the MMP-1promoter, leading to increased instability of atherosclerotic plaques [92]. ROS

generation has also been linked to increased HAT activity of p300/CBP, which is

associated with NF-

ROS can also modify histones through post-translational modifications, including S-nitrosylation, S-glutathionylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation. These modifications can impair the enzymatic activity or binding of class I HDACs (e.g., HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3) and class II HDACs (e.g., HDAC4 and HDAC5), resulting in a state of euchromatin [84]. ROS-induced modifications of HDACs include alkylation, carbonylation, tyrosine nitration, and phosphorylation, which can lead to impaired HDAC function and increased histone acetylation. Loss of HDAC function and subsequent histone acetylation have been associated with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and have been observed in diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OPD) [96] (Fig. 6).

Interestingly, ROS can have both activating and inhibitory effects on HDACs. Mitochondrial ROS, for example, can induce nuclear accumulation and activity of HDAC3 in CMCs [97], while ROS can increase HDAC2 activity in various cellular contexts [95]. ROS-induced oxidative stress can also influence the activity of class III HDACs, known as sirtuin (SIRT) proteins, which require NAD+ for their activation. Oxidative stress conditions reduce cellular NAD+ levels and decrease SIRT1 activity, leading to the dysregulation of genes involved in aging, metabolic syndrome, and CVDs, such as MI and I/R [88, 98, 99]. The activity of SIRT proteins is dependent on its highly conserved zinc tetra-thiolate motif in the deacetylase domain. ROS can oxidize or S-nitrosylate critical motifs in SIRT1 and SIRT3 proteins, impairing their deacetylase activity of target genes, such as NOS, and contributing to endothelial dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress [100, 101]. Inhibition of SIRT1 by ROS also mediated the increased expression of NOX4, vascular O2•– production, and endothelial dysfunction [102]. Decreased levels and activity of SIRT1 were also addressed in the setting of oxidative stress- induced MI and ischemic stroke [103] (Fig. 6).

Taken together, the evidence suggests that ROS play a role in modulating histone acetylation through various mechanisms, including altering HAT expression and activity, modifying HDACs, and affecting the activity of SIRT proteins. These ROS-mediated effects on chromatin remodelling have significant implications for cardiovascular health and diseases.

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are a diverse class of RNA molecules that do not encode proteins but exert regulatory functions by modulating gene expression at various levels. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), are two well-characterized classes of ncRNAs that have been implicated in the development and progression of several disease within the cardiovascular system [104, 105]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNA molecules (18–22 nucleotides) that bind to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of target mRNAs, resulting in their cleavage and degradation or translational inhibition [106]. When miRNAs are aberrantly expressed, they are implicated in pathophysiological processes that underlie the development of atherosclerosis and other CVDs, including endothelial dysfunction, vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and migration, macrophage function, and foam cell formation [107]. On the other hand, lncRNAs are longer than 200 nucleotides and can regulate gene expression through cis and trans-regulation and by various mechanisms, including chromatin modification and remodelling, transcriptional regulation, post-transcriptional modulation, and nucleosome localization changes [108].

The interplay between ROS and ncRNAs in CVDs is complex and bidirectional. Interactions between cardiac miRNAs and ROS are established in different cardiovascular events including atherosclerosis, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), MI in animal models [109]. Increased ROS production initiates fibrosis, necrosis, apoptosis, proliferation and hypertrophy of smooth and cardiac muscles, ECs, and cardiac fibroblasts [110, 111].

On one hand, ROS can modulate the expression and activity of ncRNAs. For example, H2O2-induced oxidative stress has been shown to upregulate the expression of specific miRNAs, such as miR-21 and miR-155, in cardiovascular cells [109]. These miRNAs, in turn, target genes involved in antioxidant defense and inflammation pathways, further exacerbating oxidative stress, and promoting the development of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), CH and heart failure (HF). Additionally, ROS can also modify the biogenesis and stability of ncRNAs [112]. For instance, ROS-mediated oxidation of RNA-binding proteins can affect their interaction with miRNA precursors, leading to altered miRNA processing and expression [112].

On the other hand, ncRNAs can regulate ROS production and detoxification pathways, thereby influencing oxidative stress levels in cardiovascular cells. Several studies have identified ncRNAs that directly target key components of ROS signalling pathways. For example, miR-92a has been shown to target the antioxidant enzyme sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), resulting in increased ROS production and endothelial dysfunction [113]. Similarly, lncRNA MALAT1 has been implicated in the regulation of ROS levels through its interaction with ROS-responsive TFs, such as Nrf2 [114]. Dysregulation of these ncRNAs can disrupt redox homeostasis and contribute to CVD development [114].

Importantly, the dysregulation of ROS and ncRNAs is observed in various

cardiovascular pathologies. For instance, miR-21 has been found to be upregulated

in atherosclerotic plaques and promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation and

migration by targeting phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) [115].

Similarly, the lncRNA H19 has been implicated in CH and HF by modulating

ROS production and the expression of genes involved in cardiac remodelling [116].

Increased expression of miR-154-5p was associated with angiotensin II (AngII)-

induced CH by targeting arylsulfatase-b (ARSB), which plays a critical role in

sulphate reduction in CMCs. Downregulation of ARSB by miR-154-5p led to increased

ROS generation and activation of NF-

The cardioprotective and antioxidative role of miRNA took a vast attention in DCM. For instance, miR-203 is downregulated in high-glucose treated myocardial cells (MCs). In vivo investigations on diabetic mice supported the notion that miR-203 exerts protective role on myocardial hypertrophy, by targeting the PtdIns-3-kinase subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which induced malondialdehyde (MDA) and ROS levels in the fibrotic tissue. By mediating the PI3K/Akt pathway, miR-203 can attenuate oxidative stress and apoptosis in MCs [127]. MiR-92a-5p expression in the heart of diabetic mice decreased mitochondrial ROS production, by modulating mitochondria cytochrome-b (mt-Cytb), a subunit of the complex III where ROS is abundantly produced [128] (Table 1, Ref. [109, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 129, 130]).

| Non-coding RNA | Target | ROS generation | Phenotype | In vivo or in vitro | Reference |

| miR-155 | FoxO3a | increased | hypertrophy | CMCs | [109] |

| miR-92a | SIRT1, oxLDL | increased | endothelial dysfunction & atherosclerotic lesions | ECs & mouse arteries | [129, 130] |

| lncRNA MALAT1 | Nrf2 | increased | disrupt redox homeostasis | HUVECs | [114] |

| miR-21 | PTEN, ERK-MAP kinase | increased | SMCs proliferation & migration, CH | atherosclerotic plaques, cardiac fibroblasts | [115] |

| lncRNA H19 | NFAT | increased | CH & HF | CMCs | [116] |

| miR-154-5p | ARSB, NF- |

increased | AngII- induced CH | CMCs | [117] |

| miR-122 | transcription factor FoxO3 | increased | AngII- induced hypertrophic cardiomyocytes | CMCs | [118] |

| miR-132 | BNP, GATA4 | increased | CH | rats | [119] |

| miR-212 | |||||

| miR-152 | |||||

| miR-27a | Nrf2 | increased | congestive heart failure following MI | rats | [120] |

| miR-28a | |||||

| miR-34a | |||||

| miR-22 | P38a, SIRT1, PGC-1 |

increased | MI, I/R injury | I/R-injured CMCs | [121] |

| miR-22 | SIRT1, PCG-1 |

increased | MIRI | rats & CMCs | [109, 122] |

| miR-126 | PI3K/AKt/SK-3b axis, ERK1/2 | decreased | I/R injury | EPCs | [123] |

| miR-340-5p | NF- |

decreased | I/R injury | CMCs | [124, 125] |

| miR-23a | PTEN/miR-23a axis | decreased | AMI | CMCs | [126] |

| miR-203 | PIK3CA, PI3K/Akt axis | decreased | DCM, myocardial fibrosis attenuates oxidative stress & apoptosis | CMCs, diabetic mice | [127] |

Abbreviations: SIRT1, sirtuin 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

2; PTEN, phosphatase & tensin homolog; NFAT, hypertrophic nuclear factor of

activated T cells; ARSB, arylsulfatase-b; NF-

Understanding the intricate crosstalk between ROS and ncRNAs provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying CVDs, and targeting these interactions could offer potential therapeutic strategies for disease management. For instance, modulating the expression or activity of specific ncRNAs involved in ROS regulation could potentially restore redox balance and ameliorate oxidative stress in cardiovascular cells. However, further research is needed to unravel the complex regulatory networks and identify specific ncRNAs and ROS-related pathways that could serve as potential therapeutic targets.

ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes play a crucial role in regulating gene expression by modifying the structure, organization, and accessibility of chromatin [131]. These complexes possess a shared Snf2-like ATPase catalytic domain, and by utilizing the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis, they can reposition nucleosomes on the chromatin, thereby altering chromatin accessibility [132, 133]. The specific binding to the genome and catalytic activity of these complexes are dictated by different associated members of the ATPase complex.

There are four main families of chromatin remodelling complexes. The first is the switch/sucrose nonfermentable (SWI/SNF) family, which was initially discovered in prokaryotes and yeast [131]. The second is the imitation switch family, initially identified in Drosophila. The third is the chromodomain helicase DNA-binding family, found in mice. Finally, the fourth family is the INO80 family, which was initially identified in yeast [134]. These various families of chromatin remodelling complexes play a vital role in development, as many developmental processes rely on proper chromatin regulation. By modulating chromatin structure and accessibility, these complexes contribute to the precise control of gene expression during development and other biological processes [134].

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes play a crucial role in cardiac development and are implicated in various cardiovascular conditions, including cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, atherosclerosis, pulmonary hypertension, and HF [7].

There is compelling evidence that ROS can significantly influence the activity of these complexes. One critical component, the ATPase Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1), a part of the Brg1-associated factors (BAF) complex, and the vertebrate equivalent to the SWI/SNF complex [133]. BRG1, plays a crucial role in regulating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses, specifically enhancing the induced expression of HO-1. This specificity arises from BRG1’s ability to facilitate Z-DNA formation at the HO-1 promoter, which is essential for recruiting RNA polymerase II and driving HO-1 transcription. Unlike other Nrf2 target genes such as NQO1, the regulation of HO-1 by BRG1 underscores its unique function in selective gene activation during oxidative stress, presenting a potential therapeutic target for improving antioxidant defenses [135].

In experimental models of I/R injury in diabetic mice, larger post-ischemic infarct size (IS), severe CMC apoptosis, and increased oxidative stress were observed alongside reduced expression of HO-1, nuclear Nrf2, and BRG1 protein. This indicates a potential link between BRG1 and oxidative stress in I/R injury [136]. Notably, a deficiency of BRG1 inhibited Nrf2 binding to the HO-1 promoter, further depressing HO-1 expression and exacerbating oxidative stress in diabetes [136]. Research by Liu et al. [137] further explored BRG1’s role in experimental models of AMI. The study found that BRG1 expression significantly increased in the peri-infarct zone compared to the sham group, which was accompanied by upregulation of NRF2 and HO-1, and downregulation of KEAP1. Overexpression of BRG1 through adenoviral intramyocardial injection in AMI mice resulted in reduced IS and improved cardiac function, along with increased NRF2 and HO-1 levels, further leading to decreased oxidative damage and cell apoptosis. Conversely, shRNA-mediated knockdown of BRG1 produced opposite effects, further confirmed in cultured primary neonatal rat CMCs subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation [137]. These findings demonstrate that upregulation of BRG1 during AMI enhances NRF2 levels and promotes its nuclear accumulation, facilitating HO-1 expression and alleviating oxidative stress in CMCs, thereby improving their viability [137].

Additionally, a recent study by Li et al. [76] showed that BRG1 interacts with KDM3A to activate the transcription of NOX isoforms (1, 2, and 4) in ECs. The ROS generated from increased NOX expression may exacerbate cardiac I/R injury [76]. Findings by Fish et al. [138] indicated that BRG1 restores eNOS expression during the anoxia/reoxygenation cycle by preventing the loss of acetylated histones H3 and H4 on eNOS promoters, suggesting that BRG1 protects endothelial function under oxidative stress by enhancing eNOS expression [138]. Conversely, Shao et al. [139] reported that endothelial BRG1 limits eNOS activity and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability by activating caveolin-1 (CAV1) transcription, potentially contributing to thioacetamide-induced liver fibrosis in mice [139]. This necessitates further investigation of the precise effects of BRG1 on eNOS expression and activity.

Moreover, ROS have been shown to upregulate Cockayne syndrome group B protein (CSB), a member of the SWI/SNF family, enhancing its interaction with the long-range chromatin regulator CCCTC-binding factor [140]. This interaction increases promoter occupancy of genes involved in RNA and protein homeostasis, energy control, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and mitochondrial ROS production [140]. Mutations in the CSB gene are linked to Cockayne syndrome, characterized by developmental and neurological defects, sun sensitivity, premature aging, and increased susceptibility to oxidative stress [140].

Components of the SWI/SNF complex were also found to upregulate the transcription of DAF-16/FOXO, a redox-sensitive transcription factor in Caenorhabditis elegans, enhancing stress resistance and longevity [141]. Since mammalian FOXO TFs play crucial roles in regulating redox homeostasis and are sensitive to ROS in the vasculature [142], it would be interesting to investigate whether a similar pathway operates in mammalian adaptation to ROS.

Furthermore, SWI/SNF components like BAF57 have been associated with the promoters of HIF-

Further studies are required to determine if the SWI/SNF complex also regulates HIF-

In summary, there are growing evidences that ROS can significantly influence ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and their implications in cardiovascular health.

ROS can have a direct impact on DNA by modifying its bases. One example is the conversion of 5mC to 5hmC through the removal of a hydrogen atom from the methyl group [20, 146]. This modification can interfere with the activity of DNMT1, preventing the inheritance of methylation patterns and indirectly leading to demethylation of CpG sites [20, 147]. While this mechanism has been proposed, direct proof is still lacking.

In addition to 5hmC formation, ROS can influence DNA methylation by oxidizing guanosine to 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxodG). The mutagenic effect of ROS is countered by the enzyme 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1), which removes the 8-oxodG residue, followed by base excision repair mechanisms to fill the gap [148]. However, when 8-oxodG persists, adjacent cytosines cannot be methylated, resulting in hypomethylation and transcriptional activation [149]. OGG1 recruitment to 8-oxodG sites can also facilitate DNA demethylation in coordination with TET enzymes [150].

The formation of 8-oxodG preferentially occurs at G-rich promoter regions of

well-known proto-oncogenes such as KRAS, Bcl-2, VEGF,

c-MYC, and HIF1

In vitro models of oxidative stress have demonstrated that 8-oxodG formation can activate the TF Tbx5 and enhance the differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells into CMCs [155]. Increased levels of 8-oxodG were observed in atherosclerotic vessels and correlated with disease progression [156]. Recent meta-analyses have also shown higher levels of 8-oxodG in urine and blood samples of patients with atherosclerosis, hypertension, CAD and HF [157, 158], although more extensive prospective studies are needed to establish 8-oxodG as a potential predictor of these diseases.

Apart from DNA modifications, ROS can also modify histones, which are proteins involved in chromatin structure and gene regulation. For example, histone H2B is sensitive to ONOO–, and under nitrosative and oxidative stress, it can adopt different structures to protect DNA from the damaging effects of ONOO– [159]. This suggests that H2B may have additional roles in chromatin remodelling and maintaining DNA stability. ROS can oxidize arginine and lysine residues in histone H3, leading to the formation of protein-bound carbonyl groups that affect chromatin structure and its accessibility to TFs. Additionally, H3, the only histone containing cysteine, can sense redox signalling through S-glutathionylation of Cys110, which influences euchromatin formation [160]. Furthermore, lipid peroxidation products, such as 4-oxo-2-nonenal, can form adducts with lysine residues at acetylation and methylation sites on histones H2, H3, and H4. These modifications have been detected in macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and can impact the epigenetic landscape associated with various diseases, including CDVs [161].

In recent years, there has been growing evidence suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms can also affect mitochondria, in addition to their well-established role in nuclear DNA [162]. Mitochondria, which have their own separate genome called mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), play a crucial role in cellular function and energy production. It has been estimated that over 1100 proteins are required for mitochondrial function, the majority of which are encoded by nuclear DNA and imported into mitochondria [162].

When the members of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system within mitochondria are impaired, it can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction [163]. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been extensively studied both in human and animal models of heart failure (HF) revealing compromised mitochondrial OXPHOS activity, elevated ROS levels, and aberrant dynamics of mitochondria [164]. This dysfunction not only affects the generation of ROS and mitochondrial metabolites, but also has consequences on nuclear epigenetic alterations [165]. Various epigenetic mechanisms have been identified in mitochondria, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodelling, and the expression of ncRNAs. These mechanisms can modulate mitochondrial function and are potentially sensitive to ROS [165].

For instance, methylation of nuclear DNA promoter of the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), a key protein involved in mtDNA organization, can influence TFAM gene expression, thereby influencing mtDNA copy numbers [166]. Lv et al [166] showed that acetylation of mitochondrial TFAM at lysine 76 (K76) mediated by GCN5L1 (General Control of Amino-Acid Synthesis, yeast homolog-like 1), inhibits the binding of TFAM to the mitochondrial transporter TOM70, leading to reduced TFAM import into mitochondria and mitochondrial biogenesis [166]. However, deacetylation of TFAM by Sirt3 and its phosphorylation at serine 177 by ERK2, both increased its binding to mtDNA, accompanied by gene transcription repression and suppression, respectively [167, 168].

ROS can also influence mtDNA copy numbers, but the effects may vary depending on the dose, time, and type of ROS modulation [169]. Redox agents such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S) have been implicated in reduced TFAM promoter methylation in VSMCs and aortas isolated from cystathionine gamma-lyase knockout (CSE-KO) mice [170]. Taking into account CSE, a major H2S-producing enzyme, H2S deficiency has led to reduced mtDNA copy numbers. Targeting CSE/H2S system may provide a therapeutic avenue for CVDs [170].

Exposure to cigarette smoke was also shown to decrease

TFAM expression, increase mtDNA damage, reduce mtDNA copy numbers, and impair

endothelial function [171]. Similarly, lower mtDNA copy numbers have been

observed in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a disorder

associated with oxidative stress. Decreased mtDNA copy numbers have also been

linked to an increased risk of HF in humans. It was found that hypermethylation

of D-loop regions in peripheral blood leukocytes from patients with stable

coronary artery diseases (SCAD) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS), were

associated with reduced synthesis of mtDNA [172]. A study on VSMCs showed the

effect of the platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) in triggering the

translocation of the nuclear DNMT1 to mitochondria, increasing mtDNA methylation

and suppressing gene expression in VSMCs. This was associated with mitochondrial

dysfunction and altered contractility of VSMCs [173]. CVDs are closely associated

with mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS imbalance. Experimental models have shown

that increasing mtDNA copy numbers through the increased transcription and

overexpression of TFAM or other factors can protect against oxidative

stress and provide cardioprotection. For instance, CMCs subjected to hypoxia,

exhibited an increased expression of TFAM as a compensatory mechanism. However, a

progressive decrease in its level was clear following the increase in ROS

production and calcium dysregulation [174]. It is well established that I/R

injury- induced oxidative stress triggers the nuclear translocation of nuclear

respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) and upregulation of PPARG coactivator 1 alpha

(PGC-1

Recent research has indicated increased mtDNA methylation in certain mitochondrial proteins in thrombocytes of patients with hypertension, atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation (AF), and ischemic heart disease [178, 179]. However, this field of study is still relatively unexplored, and more research is needed to further understand the relationship between ROS and epigenetic changes.

The detailed findings in this review underscore the significant impact of ROS on epigenetic modifications, which profoundly influence the pathophysiology of CVDs. Translating these insights into therapeutic interventions presents several promising avenues.

Antioxidant therapies hold significant promise in mitigating oxidative stress

and its associated epigenetic modifications in CVDs [180]. Oxidative stress,

primarily driven by an excess of ROS, plays a critical role in the pathogenesis

of CVDs [181]. Antioxidants can neutralize ROS, thereby reducing oxidative damage

and modulating epigenetic changes [181]. Various mechanisms of antioxidants

include scavenging free radicals, upregulating endogenous antioxidant defenses,

and preventing aberrant modifications such as DNA methylation and histone

modifications [180, 182]. Several antioxidants have been studied in clinical

trials, highlighting their therapeutic benefits [183]. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC), a

precursor to GSH, has shown promising results; a recent randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled, multicentre study assessed the effects of high-dose

intravenous NAC with nitroglycerin on early cardiac MRI outcomes in

ST-segment–elevation MI patients. NAC significantly reduced cardiac infarct size

(IS) by 5.5% compared to placebo (p = 0.02) and doubled myocardial

salvage (p

While the therapeutic potential of antioxidants is promising, challenges and limitations remain. The efficacy of antioxidant therapies in clinical trials has been variable, which may be due to differences in study design, patient populations, and antioxidant dosages. Many antioxidants have poor bioavailability, limiting their therapeutic effectiveness. Future research should focus on improving the delivery and bioavailability of these compounds, exploring combination therapies, and developing targeted antioxidant therapies that can specifically modulate redox-sensitive signalling pathways and epigenetic modifications. By addressing these challenges and focusing on targeted interventions, antioxidant therapies could play a crucial role in the prevention and treatment of CVDs.

The flexibility of the epigenome has prompted the exploration and development of a range of epigenetic compounds, many of which have already gained FDA approval for treating different diseases. Epigenetic drugs target DNA methylation (Table 2, Ref. [22, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209]), histone modifications (Table 2), and ncRNAs offer novel therapeutic strategies [210]. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTis) and histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) have shown promise in preclinical models of CVDs [22]. These drugs can reverse aberrant epigenetic changes linked to ROS levels, restoring normal gene expression and cardiovascular function [57].

| Epigenetic drug family | Drug/natural product name | Cardioprotective effect | Reference |

| DNMTis | 5-Aza-dC (decitabine) | alleviates atherosclerotic lesions | [196] |

| Cocoa extract | improves atherosclerosis and CAD | [197] | |

| RG108 | reduces MH and MF | [22] | |

| 5-azacytidine (azacytidine) | improves MH, reduces MF | [22] | |

| 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine | reduces MH | [198] | |

| improves cardiac contractility | |||

| reduces ischemic injury | |||

| HDACis | Nullscript, scriptaid, TSA | prevents myocardial I/R injury | [199] |

| reduces MI | |||

| SAHA | reduces IS in myocardial I/R injury | [200, 201] | |

| attenuates takotsubu-like myocardial injury | |||

| SK-7041 | reverses MH | [202] | |

| Vorinostat | attenuates MH, RHF, and MF | [203, 204, 205] | |

| reduces left ventricular dysfunction | |||

| Romidepsin | attenuates atherosclerosis | [203, 204, 206, 207] | |

| protects against hypertension | |||

| Givinostat | improves cardiac performance | [208] | |

| Valproate | protects against MI | [208] | |

| HMTis | Tanshinone IIA | reduces MH | [209] |

| prevents against cardiac remodeling |

Abbreviations: DNMTis, DNA methyltransferase inhibitors AD; HDACis, histone deacetylase inhibitors; HMTis, histone methyltransferase inhibitors; MH, myocardial hypertrophy; MF, myocardial fibrosis; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; I/R injury, ischemia-reperfusion injury; RHF, right heart failure; LV, left ventricular; TSA, Trichostatin-A; SAHA, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid.

DNMTis, such as azacytidine and decitabine, are well-studied for their ability to inhibit DNA methylation, a key epigenetic modification implicated in CVDs pathogenesis [210, 211] (Table 2). These compounds function by incorporating into DNA during replication, thereby blocking the action of DNMTs and leading to global hypomethylation of DNA [210]. This hypomethylation can reverse the silencing of genes critical for cardiovascular health, such as those involved in endothelial function and cardiac remodeling processes [210].

Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of DNMTis in preclinical models of HF and

CAD [22]. For instance, treating Ldlr-/- mice with 5-Aza-dC

(decitabine) can inhibit macrophage migration and adhesion to epithelial cells,

decrease macrophage infiltration into atherosclerotic plaques, and reduce the

expression of inflammatory genes in macrophages [196]. These effects help

alleviate atherosclerotic lesions and slow the progression of atherosclerosis

[212]. Another study reported that cocoa extract improved atherosclerosis and

coronary heart disease by inhibiting DNMTs and reducing methylenetetrahydrofolate

reductase (MTHFR) gene expression levels in vitro [197].

Additionally, in adults with cardiovascular risk factors, cocoa combined with

statins lowered cholesterol levels, providing a protective effect on the

cardiovascular system (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00502047) [197]. DNA

methylation is closely linked to HF treatment [22]. RG108 has been reported to

inhibit DNMTs, reducing myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis progression [22]. The

DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine decreases the negative impact of tumor

necrosis factor-

Clinical trials investigating DNMTis in cardiovascular settings are ongoing, aiming to translate these preclinical findings into therapeutic strategies for human patients. These trials are evaluating the safety, efficacy, and long-term effects of DNMTis in various CVDs conditions, including HF, CAD, and AF [213].

HDACis represent another class of epigenetic drugs that modify histone proteins, thereby influencing gene expression patterns in cardiovascular cells [22, 210]. By inhibiting HDAC enzymes, these drugs promote histone acetylation, which typically correlates with enhanced gene transcription. In the context of CVD, HDACis have shown promise in reducing CH, fibrosis, and inflammation—key processes implicated in HF and ischemic heart disease progression [22, 210] (Table 2). Early experimental studies in mice indicate the potential of HDACis in cardiovascular treatments. HDACis nullscript, scriptaid and TSA, prevented from MIRI and reduced IS in mice [199]. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) reduced IS by 50% in MIRI models, restored autophagic flux, and attenuated takotsubu-like myocardial injury [200, 201], while class I HDAC-selective inhibitor, SK-7041, partially reversed CH in mice [202]. These inhibitors modulate genes involved in cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and inflammation, which are key features of HF [210]. Notable HDACi, such as vorinostat and romidepsin, initially used in cancer therapy, have shown cardiovascular benefits [203, 205, 206, 207]. Vorinostat is a pan-HDACi, while romidepsin specifically targets class I HDACs [204]. Givinostat improved cardiac performance in experimental diastolic dysfunction models, and valproic acid (valproate), initially used for epilepsy, protected against MI-induced LV remodeling [208] (Table 2).

HMTs add methyl groups to lysine residues in proteins. Few HMTis have entered clinical trials, including DOT1L inhibitors for leukemia, tazemetostat for B cell lymphoma, and EPZ015938 for cancer [214, 215]. Among these, tanshinone IIA, a compound from Danshen, has shown direct cardiovascular benefits. It reduces H3K9 trimethylation by inhibiting JMJD2A, silences pro-hypertrophic genes, and prevents maladaptive cardiac remodeling. Tanshinone IIA also increases Nrf2 expression through promoter hypomethylation and HDAC inhibition [209] (Table 2).

Beyond DNA methylation and histone modifications, ncRNAs particularly miRNAs and

lncRNAs have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression in cardiovascular

cells [22, 210] (Table 3, Ref. [22, 216, 217, 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230]). These molecules play pivotal

roles in modulating oxidative stress responses, vascular inflammation, and

endothelial dysfunction, all of which contribute to CVDs pathophysiology [231].

Rapid advancements in nucleotide gene therapy, including antisense

oligonucleotides (ASOs) and siRNA, highlight their potential as treatments due to

their ease of synthesis and low cytotoxicity [22]. In atherosclerosis, ncRNAs are

pivotal therapeutic targets; for instance, inclisiran (ALN-PCSSC), an RNAi

therapeutic, lowers LDL cholesterol by inhibiting PCSK9 synthesis and has shown

efficacy in clinical trials [216, 217]. Additionally, AKCEA-APOCIII-LRx and

IONIS-ANGPTL3-LRx target apolipoprotein C-III and ANGPTL3 mRNA,

respectively, reducing atherosclerotic lipoproteins and delaying disease

progression [218, 219]. LncRNA small nucleolar host gene-12 (SNHG12),

and volanesorsen have shown promise in treating atherosclerosis by protecting

against DNA damage and reducing hypertriglyceridemia [22, 220, 221]. For MI,

ncRNA-based drugs like alirocumab, which targets proprotein convertase

subtilisin- kexin type 9 (PCSK9), reduces ischemic cardiovascular events and

prevents from ACS [222, 223]. Moreover, lncRNA MIAT and cirRNA MFACR have been

identified as potential targets for protection against MI and reducing

cardiomyocyte apoptosis [224, 225]. In the treatment of HF, MRG-110 and CDR132L,

targeting miRNA-92a and miRNA-132 respectively, are in clinical trials, while

other ncRNAs like cirRNA HRCR and circ-FOXO3 showed potential effect in blocking

CH and delaying cardiac aging [22, 226, 227]. Additionally, ncRNAs such as

lncRNA-ANCR and lncRNA H19 regulate osteoblast differentiation and vascular

calcification, presenting new therapeutic strategies [22, 228, 229]. The Wnt-

| ncRNA based drugs | Target | Cardioprotective effect | Reference |

| Inclisiran (ALN-PCSSC) | PCSK9 | reduces LDL-C | [216, 217] |

| AKCEA-APOCIII-LRx | apo C-III | reduces atherosclerosis | [218, 219] |

| IONIS-ANGPTL3-LRx | ANGPTL3 mRNA | reduces atherosclerosis | [218, 219] |

| SNHG12 | DNA-PK | reduces atherosclerosis | [22, 220] |

| Volanesorsen | C3 (APOC3) | reduces hypertriglyceridemia | [22, 221, 230] |

| Alirocumab | PCSK9 | reduces ischemic cardiovascular events | [222, 223] |

| protects from ACD | |||

| lncRNA MIAT | miRNA-150-5p, VEGF | protects from MI | [224] |

| reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis | |||

| cirRNA MFACR | miRNA-125b | protects from MI | [225] |

| reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis | |||

| MRG-110 | miRNA-92a | protects from HF | [22] |

| CDR132L | miRNA-132 | protects from HF | [22] |

| cirRNA HRCR | miR-223 | protects from CH | [22, 227] |

| protects from HF | |||

| circ-FOXO3 | CDK1 (P21), CDK2 | protects from cardiac aging | [22, 226] |

| lncRNA-ANCR | Runx2, BMP2 | prevents vascular calcification | [22, 228] |

| XAV939 | lncRNA H19, Wnt- |

regulates and prevents vascular calcification | [22, 229] |

Abbreviations: PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein C; DNA-PK, DNA-dependent protein kinase; apo C-III, apolipoprotein C-III; CV, cardiovascular; ACD, acute coronary disease; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; MI, myocardial infarction; CMC, cardiomyocyte; HF, heart failure; CH, cardiac hypertrophy; CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1; CDK2, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2; miRNA, micro RNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; cirRNA, circular RNA; ANGPTL3, angiopoietin like 3.

Exosomal hsa_circRNA_0006859 has been identified as a potential therapeutic gene for preventing vascular calcification through miRNA-431-5p [232]. Overall, targeting ncRNAs offers a novel approach to treating CVDs [22]. Future clinical applications may include detecting ncRNA plasma levels to diagnose and determine the severity of CVDs and reversing pathological changes through gene-targeted therapies. Most studies on the ncRNA are in preclinical or early clinical stages, but ongoing research is expected to yield new treatments that improve patient outcomes.

Lifestyle interventions, such as diet and exercise, are pivotal in modulating epigenetic marks and reducing ROS levels, thereby offering a comprehensive strategy to mitigate CVDs risk [233, 234]. For instance, caloric restriction has been found to reduce oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids, which in turn can decrease the incidence of age-related diseases, including CVDs [235]. Additionally, caloric restriction can influence DNA methylation and histone modifications, leading to the activation of protective genes and the suppression of deleterious ones [236].

Regular physical activity also plays a crucial role in maintaining cardiovascular health by modulating epigenetic mechanisms. Exercise has been shown to induce beneficial epigenetic changes in genes involved in antioxidant defense, inflammation, and metabolism [237]. For example, aerobic exercise can increase the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD and GPx, through epigenetic modifications [238]. Moreover, hypertension is a major preventable cause of death. A study investigated the impact of a three-month aerobic exercise program on DNA methylation and blood pressure (BP) in 68 volunteers. The findings revealed increased VO2peak and decreased diastolic BP post-intervention. Exercise elevated methylation levels of ALU, long interspersed nuclear element-1 (LINE-1), EDN1, NOS2, and TNF genes. Positive associations were found between VO2peak and methylation of ALU, EDN1, NOS2, and TNF, while systolic and diastolic BP were inversely associated with LINE-1, EDN1, and NOS2 methylation. These results suggest that DNA methylation may play a role in exercise-induced BP reduction [239]. Furthermore, our study investigated the impact of 12 weeks of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on retinal microvascular function, p66𝑆ℎ𝑐 gene expression, and oxidative stress in ageing subjects with multiple CV risk factors. HIIT significantly improved microvascular phenotype by widening arterioles and narrowing venules. It also restored p66𝑆ℎ𝑐promoter methylation, reduced p66𝑆ℎ𝑐 gene expression, and lowered plasma 3-nitrotyrosine levels, suggesting HIIT’s potential to mitigate age-related oxidative stress through DNA methylation changes [240]. In conclusion, non-pharmacological interventions such as caloric restriction and regular physical activity can significantly influence epigenetic marks and ROS levels, offering a holistic and effective approach to mitigating the risk of CVDs. These lifestyle changes not only improve overall health but also complement pharmacological therapies, providing a comprehensive strategy for the prevention and management of CVDs.

Future research should prioritize several key areas to enhance the efficacy and applicability of antioxidant and epigenetic therapies for CVDs. Improving bioavailability and delivery systems is crucial, with a focus on advanced delivery methods such as nanoparticles, liposomes, and prodrug strategies to enhance stability and targeted delivery of antioxidants. Additionally, exploring combination therapies that include antioxidants with traditional cardiovascular drugs or other therapeutic agents may provide synergistic effects, improving outcomes for CVDs patients. Personalized medicine approaches can further optimize treatment efficacy by tailoring therapies to individual genetic and epigenetic profiles.

Developing targeted antioxidant therapies that specifically modulate redox-sensitive signaling pathways and epigenetic modifications is another important direction. Understanding the impact of antioxidants on DNA methylation, histone modifications, and ncRNA expressions will be crucial. Moreover, extensive clinical trials across diverse populations and long-term studies are necessary to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of these therapies, ensuring their broad applicability.

Non-coding RNA (ncRNA) therapies, including gene therapy approaches using miRNAs and lncRNAs, should be a focus of future research. Investigating how ncRNAs regulate oxidative stress responses and contribute to the pathogenesis of CVDs will be essential for developing targeted ncRNA-based therapies. Additionally, lifestyle interventions such as diet and exercise should be explored for their impact on epigenetic modifications and oxidative stress. Nutrigenomics and studies on the epigenetic effects of physical activity can lead to personalized lifestyle recommendations that complement pharmacological therapies.