1 Colorectal Surgery, Third Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Yunnan Cancer Hospital, Peking University Cancer Hospital Yunnan, 650000 Kunming, Yunnan, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 650000 Kunming, Yunnan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Lysosomes are essential intracellular catabolic organelles that contain digestive enzymes involved in the degradation and recycle of damaged proteins, organelles, etc. Thus, they play an important role in various biological processes, including autophagy regulation, ion homeostasis, cell death, cell senescence. A myriad of studies has shown that the dysfunction of lysosome is implicated in human aging and various age-related diseases, including cancer. However, what is noteworthy is that the modulation of lysosome-based signaling and degradation has both the cancer-suppressive and cancer-promotive functions in diverse cancers depending on stage, biology, or tumor microenvironment. This dual role limits their application as targets in cancer therapy. In this review, we provide an overview of lysosome and autophagy-lysosomal pathway and outline their critical roles in many cellular processes, including cell death. We highlight the different functions of autophagy-lysosomal pathway in cancer development and progression, underscoring its potential as a target for effective cancer therapies.

Keywords

- lysosome

- autophagy

- cancer

- cell death

- cell senescence

Lysosomes, initially identified by Christian De Duve in the 1950s, are membrane-bound organelles containing more than 60 different types of hydrolytic enzymes that degrade various biological macromolecules [1, 2, 3]. Lysosomes ensure sustained autophagy function in cells. Functioning as digestive centers in eukaryotic cells, lysosomes play an important role in degrading unwanted substances, damaged organelles, microbes, and particles [4]. Beyond enzymatic functions, lysosomes also regulate multiple ions (e.g., H+, Ca2+, Na+, Fe2+, K+, and Zn2+) through ion channels and transporters [4, 5]. They rely on ions for their functions and reciprocally contribute to cellular ion homeostasis. Lysosomes utilize proton pumps, particularly vacuolar-type H+ adenosine-triphosphatase (V-ATPase), to concentrate H+ ions, thereby creating an acidic environment within the lysosomal lumen to enhance enzyme activity [6]. Moreover, lysosomes have the ability to store Ca2+ and regulate its concentration in the cytoplasm [7].

Traditionally viewed as cellular waste disposal units, lysosomes have experienced a significant paradigm shift in the last decades. They now function as dynamic and versatile organelles, serving as multifunctional signaling hubs that extend well beyond their conventional roles [8]. Notably, lysosomes actively participate in nutrient sensing, influencing cellular decisions through pathways like mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) based on nutrient availability [9]. They also play central roles in immune cell signaling by degrading pathogens and presenting antigens, initiating immune responses [10, 11, 12]. Additionally, lysosomes are key players in cellular metabolism, breaking down macromolecules to provide essential building blocks for energy production [8, 13, 14]. This multifunctional role positions lysosomes as integral components in cellular homeostasis, adaptive responses, signaling cascades, etc. [15].

In recent years, research has revealed that aberrant lysosome function can lead to diseases including cancer and neurodegeneration disease [16, 17, 18]. This review delves into the connection between autophagy-lysosomal pathway and cancer, emphasizing how its role shifts throughout the stages of cancer development. During the initial stages, lysosomes act as tumor suppressors, maintaining cellular balance and eliminating mutated cells through processes like autophagy. As cancer progresses, lysosomes adapt to support increased metabolic activity, contributing to the sustained growth of cancer cells. The dual role of autophagy-lysosomal pathway, as both protectors and enablers, underscores their complex involvement in cancer development. Understanding these roles is crucial for developing innovative treatments and gaining insights into cancer development. In this review, we begin by summarizing the roles of lysosomes in biological processes, particularly autophagy, to enhance understanding, and then discuss their functions and associated pathways in different stages of tumor development and progression, including both promoting and inhibiting effects on cancer.

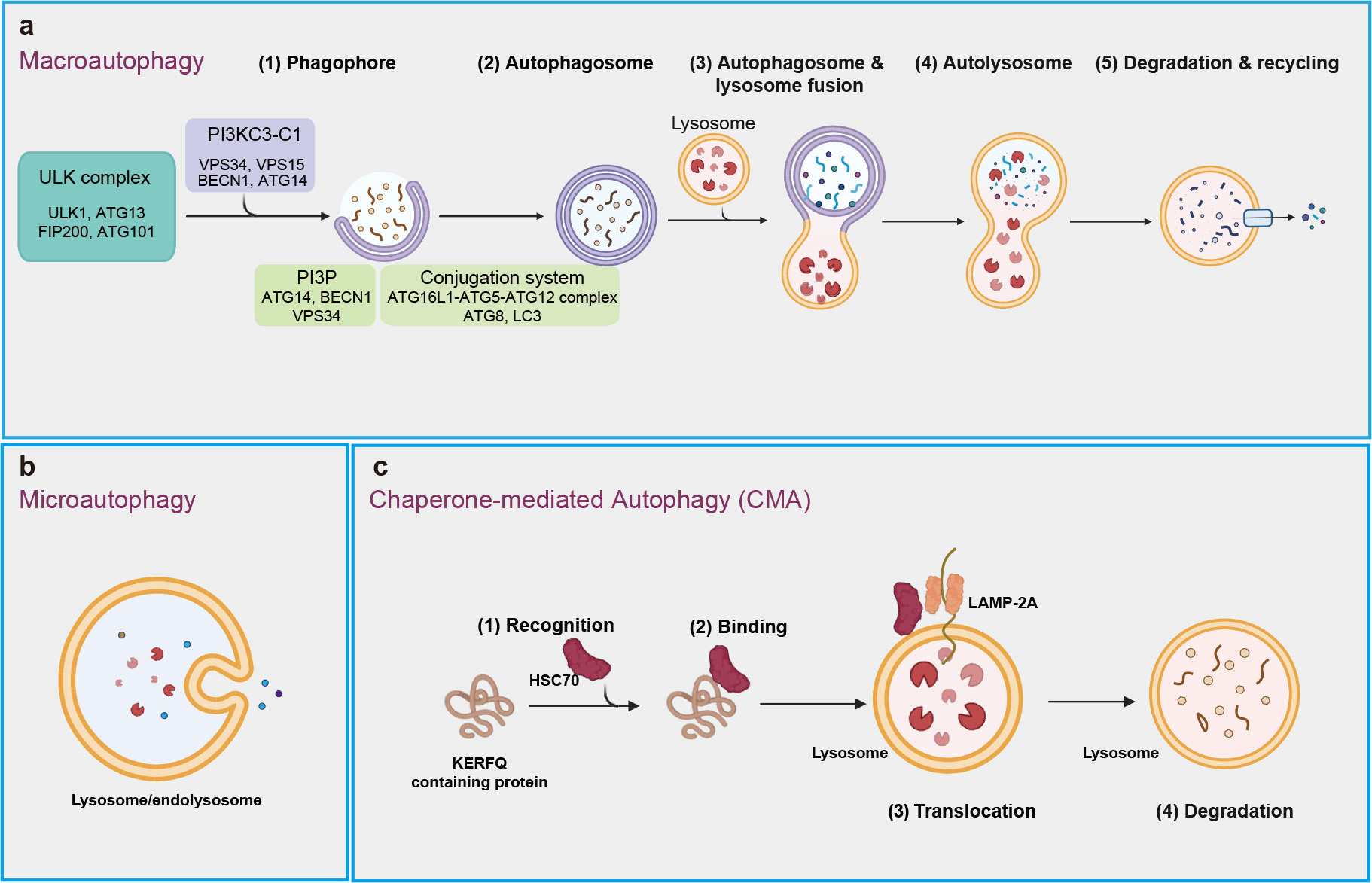

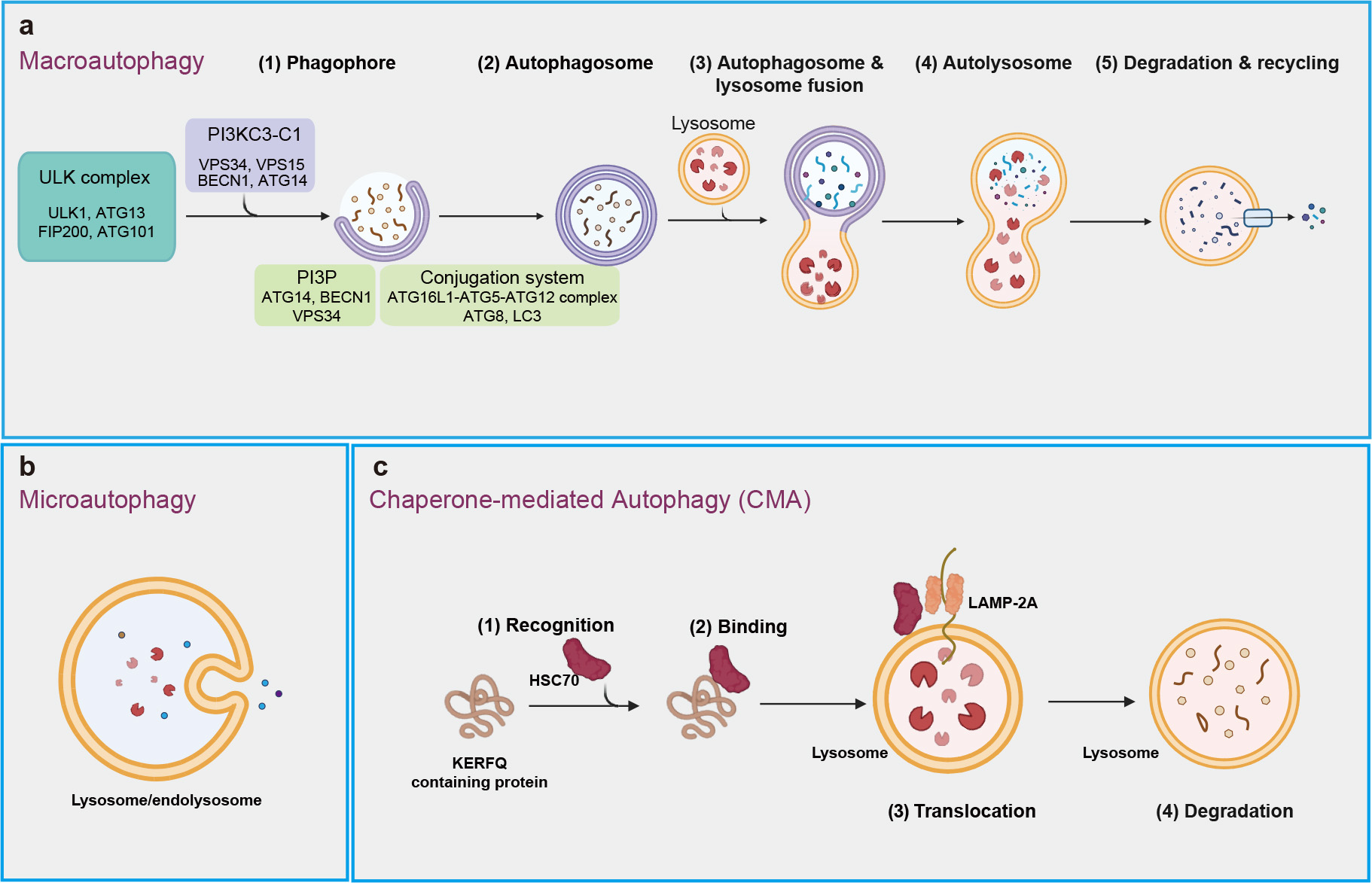

Autophagy is conserved degradation process that involves the delivery of cytoplasmic materials to lysosomes for breakdown and recycling [19, 20]. This essential mechanism facilitates the turnover of proteins and organelles, contributing to cellular rejuvenation and survival [21, 22]. More than 20 core autophagy-related (ATG) proteins regulate various phases of this process, including initiation, autophagosome nucleation, membrane deformation and autolysosome assembly [23, 24, 25]. Macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) are three well-known types of autophagy that rely intricately on lysosomal function for the degradation of cellular constituents (Fig. 1) [26].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Three main types of autophagy. (a) Macroautophagy includes a series of processes that begin with the formation of phagophore, which expands and seals to create autophagosome. This autophagosome then fuses with a lysosome, resulting in the formation of an autolysosome, where intracellular components are degraded and recycled. (b) Microautophagy involves the recognition of intracellular components by the lysosomal membrane, binding of these components through membrane invagination, and internalization into the lysosome for degradation. (c) Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is process in which chaperons (e.g., HSC70) recognize specific proteins with ‘Lys-Phe-Glu-Arg-Gln’ (KFERQ)-like motifs, transport them to lysosomal membrane, and facilitate their internalization through interaction with lysosomal receptor LAMP-2A for degradation. ULK, unc-51-like kinase; LAMP-2A, lysosome-associated membrane protein-2A; PI3KC3-C1, class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex I; VPS34, vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 34; VPS15, vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 15; BECN1, Beclin 1; ATG14, autophagy-related 14; PI3P, phosphoinositide phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3.

Macroautophagy, often known simply as “autophagy”, is considered the predominant type of autophagy, highly inducible in response to conditions like starvation and other stresses (Fig. 1a). The initiation of macroautophagy involves the formation of double membrane structure called the phagophore, which originates from the endoplasmic reticulum and may also derive from other sources, such as Golgi complex, mitochondria, and plasma membrane [27]. This process is regulated by the unc-51-like kinase (ULK) complex, consisting of ULK1, ATG13, focal adhesion kinase family interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200), and ATG101 [28], along with the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex I (PI3KC3-C1), which includes vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 34 (VPS34), VPS15, Beclin 1 (BECN1), and ATG14. PI3KC3-C1 binds to lipid membrane to generate phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), a process facilitated by ATG14, BECN1 and VPS34 [29, 30, 31]. PI3P helps recruit the autophagy machinery proteins, including the ATG16L1-ATG5-ATG12 complex, which facilitate the lipid conjugation of the ATG8 family members, including the microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3), crucial for cargo recruitment and autophagosome maturation. Subsequently, autophagosomes then fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, where cellular materials are broken down and recycled [31, 32, 33]. Macroautophagy, categorized as non-selective or selective, involves the random engulfment of cytoplasmic components or the specific targeting of particular cargoes (e.g., protein complex) into autophagosomes for lysosomal degradation [34, 35].

Microautophagy refers to the process by which lysosomes or late endosomes (which fuse to form endolysosomes) directly engulf and degrade their internal contents [36] (Fig. 1b). This process occurs mainly through three mechanisms: lysosomal membrane protrusion, lysosomal membrane invagination, and late endosomal membrane invagination [37]. In addition, accumulating studies have shown microautophagy can selectively degrade specific proteins [36].

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a well-known type of selective autophagy, crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis by degrading 30% of cytosolic proteins under conditions of prolonged nutrient deprivation [38] (Fig. 1c). CMA resembles biosynthetic pathways for proteins that to traverse membranes for entry into structures such as the endoplasmic reticulum or mitochondrion [38, 39]. It can be upregulated in various conditions, including oxidative stress and genotoxic insults [40, 41, 42].

CMA primarily targets the soluble cytosolic proteins that contain a KFERQ-like consensus amino acid motif (Lys-Phe-Glu-Arg-Gln), for degradation in lysosome. Cytosolic chaperone heat-shock cognate protein of 70 kDa (hsc70) can recognize and bind the KFERQ-like motif of target proteins, which were then bind to lysosome-associated membrane protein-2A (LAMP-2A) on lysosomal membrane. Upon binding to LAMP-2A, the substrate protein is unfolded, translocated into the lysosome, and rapidly degraded [43, 44, 45].

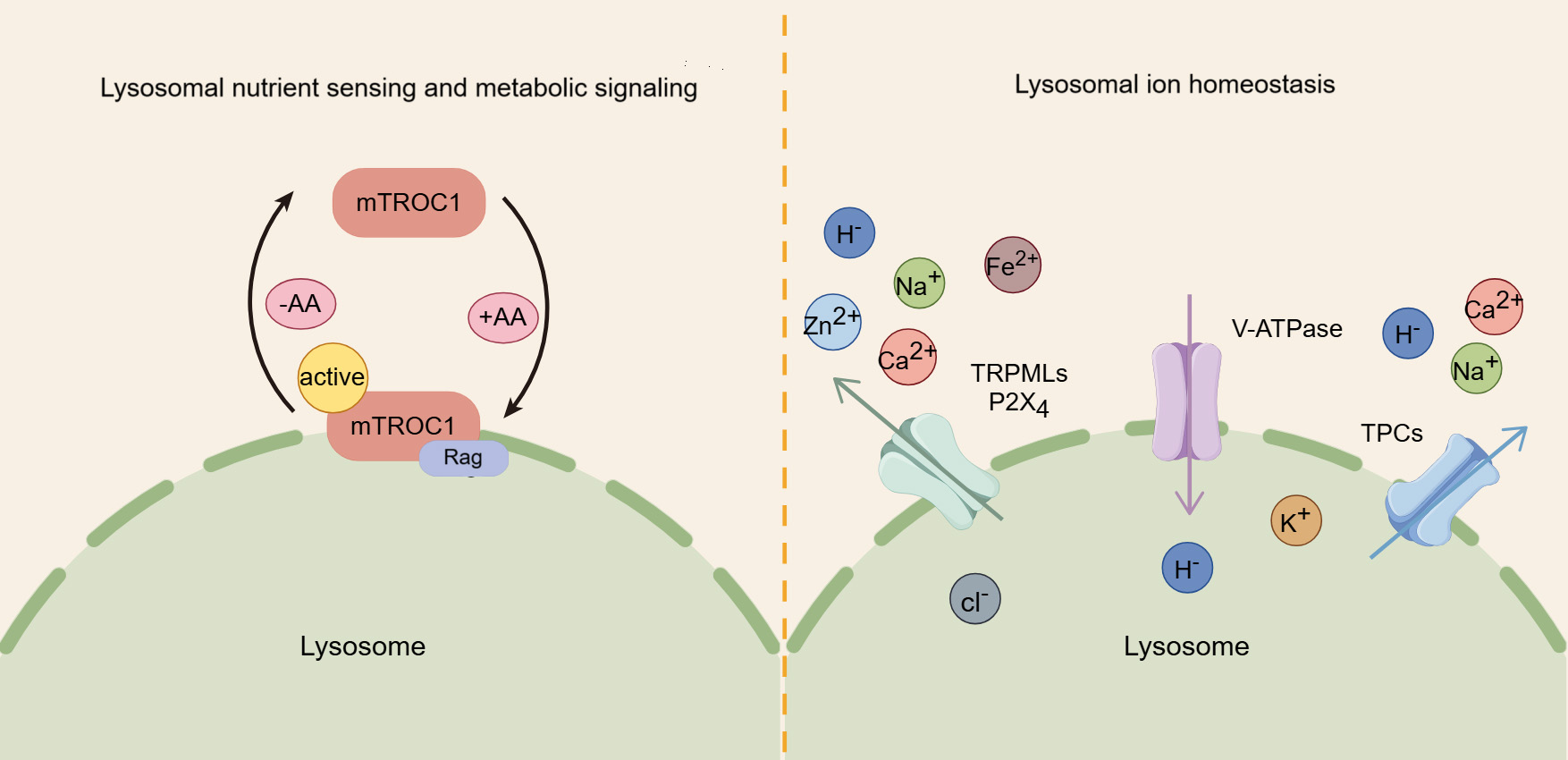

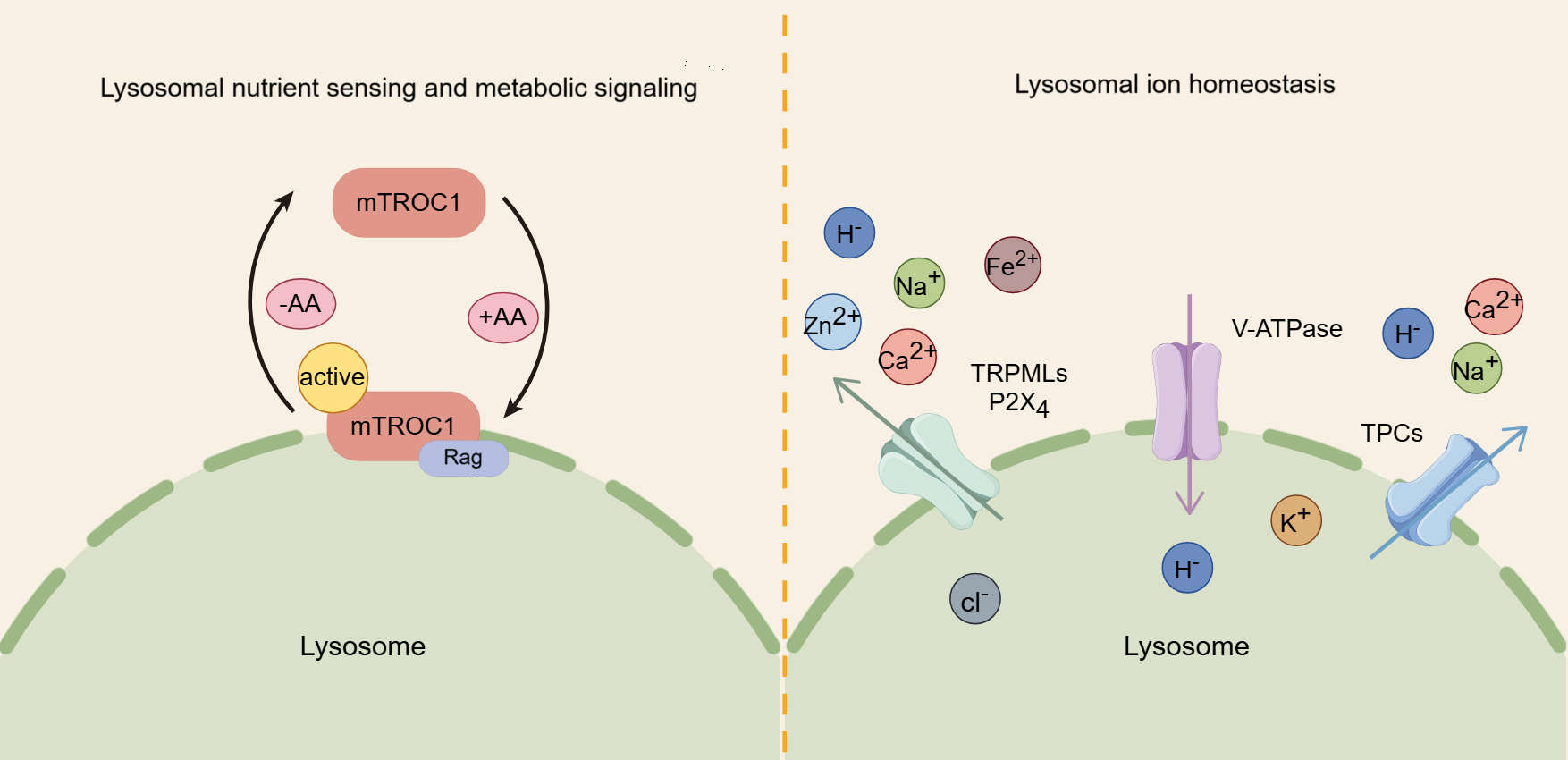

The lysosome plays a crucial role in sensing nutrients and regulating signaling pathways related to cellular metabolism and growth. Notably, the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) kinase complex, a key regulator of cell and organismal growth, can translocate to the lysosomal surface, where it inhibits autophagy [46]. mTORC1 is comprised of several core components, including mTOR, regulatory associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), and mammalian lethal with Sec13 protein 8 (mLST8) [47]. The lysosomal membrane is the primary site for the regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. In the presence of amino acids, mTORC1 is driven to localize on lysosomes, while in their absence, it remains dispersed in the cytoplasm [48]. Amino acids rely on lysosome-bound heterodimers of Rag proteins to recruit mTORC1 to lysosomes, promoting its interaction with the Raptor subunit. Once localized to the lysosome, mTORC1 is activated, fostering the conversion of nutrients into essential macromolecules, fueling anabolic pathways [49] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The roles of lysosomes in nutrient sensing, metabolic signaling, and iron homeostasis. Amino acids (AA) activate mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) by promoting its binding to the lysosomal membrane, thereby regulating key metabolic signaling pathways. In addition, the lysosome serves as a crucial storage for various ions, and their transport, regulated by proteins like transient receptor potential mucolipin channels (TRPMLs) and two-pore channels (TPCs), is crucial for maintaining cellular ion homeostasis.

In addition, lysosome is closely linked to the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) network, which monitors cellular energy levels and triggers autophagy in response to energy depletion. While AMPK was previously thought to be localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, studies have revealed that it also localizes to the late endosome/lysosome, where it interacts with AXIN1 and orchestrates distinct lysosomal signaling pathways in response to glycolytic signals [50, 51]. Aldolase senses fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) at the lysosome and transmits the glycolytic signal to regulate the formation of the AXIN-LKB1-Ragulator complex, activating AMPK at the lysosome [52]. Since AMPK and mTORC1 share the same lysosomal anchoring site, they may compete for activation at the lysosomal surface. While both can use the same downstream effectors, there effects are opposite: mTORC1 drives anabolic processes by suppressing autophagy, whereas AMPK promotes catabolism by stimulating autophagy [53, 54].

Similar to the cytosol, lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles rich in various ions, including Ca2+, Na+, K+, H+, Cl–, Fe2+, and Zn2+, each of which exerts unique and indispensable physiological functions [5] (Fig. 2). Among these, Ca2+ is important for lysosomal trafficking and function [55, 56]. As a universal signaling messenger, Ca2+ is involved in crucial for regulating various cellular processes, such as endocytic membrane trafficking, autophagy, and protein transport [57, 58]. Lysosomal calcium efflux is mediated by three major types of channels: transient receptor potential mucolipin channel (TRPML), two-pore channel (TPC), and trimeric calcium two-transmembrane channels (P2X4) [59]. The TRPML family consists of three isoforms (TRPML1, 2, and 3), with TRPML1, primarily located in lysosomes, serving acts as an important positive regulator of autophagy by promoting the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes through the release of calcium ions [60, 61]. TRPML2 and transient receptor potential mucolipin channel 3 (TRPML3) also participate in autophagy, with TRPML3 enhancing autophagy when overexpressed and inhibiting it when knocked down [62]. Additionally, TPCs, located on the lysosomal membrane, are likewise involved in calcium ion flux and the regulation of autophagy [63]. A study shows that TPC agonists can trigger Ca2+ release and inhibit the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes through increasing lysosomal pH [64]. Furthermore, P2X4 is also implicated in lysosomal function, becoming active during lysosomal exocytosis to facilitate processes such as surfactant secretion or phagocytosis [65, 66].

In addition to Ca2+, other ions also have significant biological functions. Monovalent cations such as Na+ and K+ constitute the primary positive charge within the lysosomal lumen [67]. Na+ is necessary for the function of certain lysosomal transporters, including those from the SLC38 family [68, 69], while K+ regulates the lysosomal membrane potential and the homeostasis of lysosomal Ca2+ [69, 70]. H+ is essential for maintaining the activity of lysosomal digestive enzymes, most of which require an acidic environment to function optimally [5, 6]. Cl– acts as counterions to modulate the lysosomal membrane potential and, to a certain degree, aid in the acidification of the lysosomal lumen [71, 72, 73]. Fe2+ catalyzes the hydrolysis of H2O2, producing reactive oxygen species and playing a crucial role in the lysosomal response to oxidative stress [74, 75, 76]. Zn2+ is a trace element that serves as an essential coenzyme for about 300 protein [77, 78].

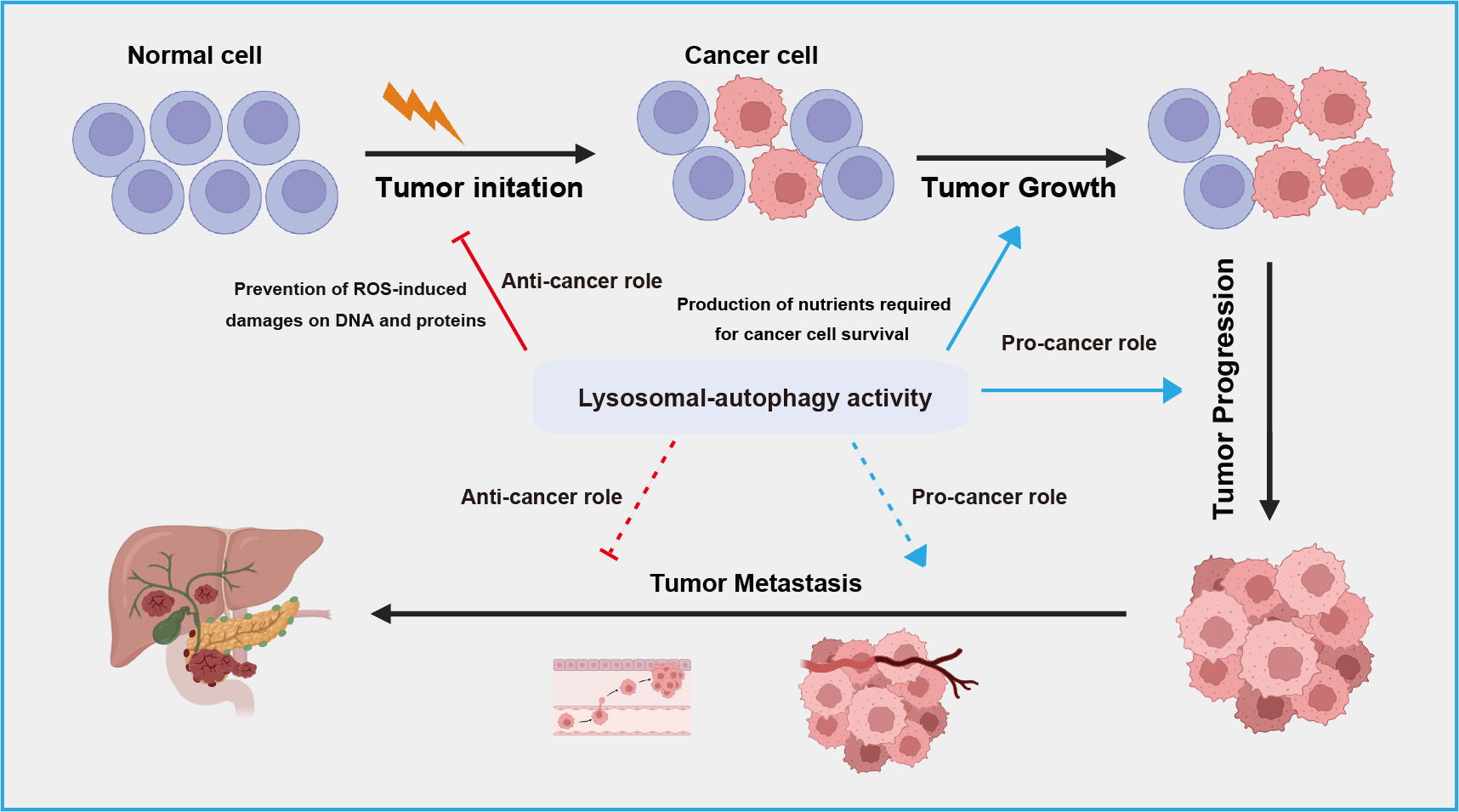

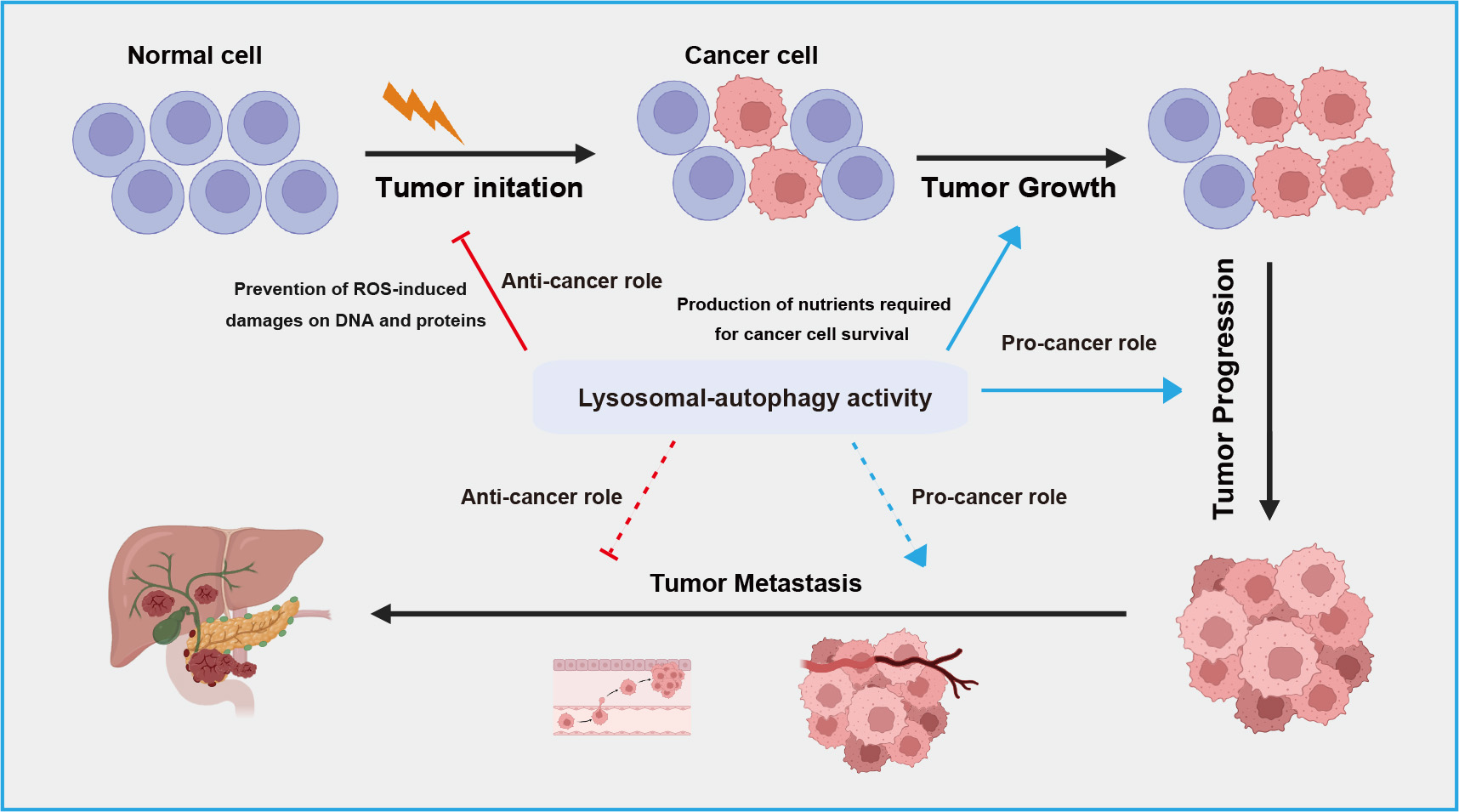

The relationship between autophagy-lysosome system and cancer is complex and context-dependent. Autophagy serves as crucial homeostatic mechanism within cells contributing to cellular integrity, redox balance, and proteostasis by eliminating damaged organelles and proteins, thereby exerting a protective role against cancer [79, 80] (Fig. 3). However, in the context of tumor progression, autophagy can also be hijacked by cancer cells to support their survival and growth [81]. Autophagy facilitates adaptation to the challenging microenvironments of tumors by supplying nutrients through the breakdown of cellular components, promoting cancer cell proliferation and metastasis (Fig. 3). In terms of therapeutics, ongoing research explores targeting autophagy as a strategy to either enhance or inhibit this process for more effective cancer treatments [82, 83].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

A schematic overview of dual roles of lysosomal-autophagic pathway in different stage of tumor development. The lysosomal-autophagic pathway suppresses tumor initiation by degrading damaged proteins in normal cells but promotes tumor cell growth and progression by suppling nutrients. During tumor metastasis, this pathway exhibits both anti-tumor activity by limiting inflammatory responses and pro-tumor activity by promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Autophagy is widely recognized for its crucial role in preventing tumor initiation in healthy tissues [81]. Before the onset of carcinogenesis, it acts as a key cytoprotective mechanism, mitigating metabolic stress and genome instability, thereby preventing tumor initiation [84]. Initial evidence supporting the tumor-suppressive role of autophagy emerged from a study on the autophagy-essential BECN1 gene, responsible for encoding beclin-1 functioning in the formation of the phagophore [79]. Earlier research, such as a study reporting frequent allelic deletion of BECN1 in breast and ovarian cancers, suggesting that the loss of BECN1 and potential detects in autophagy are implicated in tumorigenesis [85]. Additionally, both cancer cell lines and mouse models reveal that loss of BECN1 leads to reduced autophagy and increased cell proliferation, further indicating the tumor suppressor of the BECN1 gene [79, 86, 87]. Moreover, a growing body of findings have shown that a large number of autophagy-related genes (e.g., ATG5, ATG12) are mutated or inactivated to evade the tumor suppressive effects of autophagy as tumor development progresses [88].

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), primarily comes from damaged mitochondria, significantly contributes to mutagenesis and, consequently, tumor initiation [89, 90]. Research indicates that autophagy’s elimination of damaged mitochondria leads to decreased ROS production, thereby limiting the tumor-promoting effects of ROS [91]. Moreover, studies have shown that inhibiting autophagy results in chronic oxidative stress and the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, promoting the initiation of tumor [92, 93]. An increasing body of evidence suggests that autophagy plays a role in suppressing tumor initiation by degrading certain proteins known to drive tumorigenesis [84, 94]. Among these, the oncogenic mutant p53 protein is particularly significant in this context, as it plays an important role in initiating tumor [95]. Autophagy, specifically through CMA, facilitates the degradation of mutant p53, autophagy, particularly through CMA, thereby contributing to the suppression of tumor initiation [96].

Once the primary tumor is formed, the role of autophagy in tumor progression becomes intricate and dependents on the cellular context. The earliest evidence of autophagy’s role in maintaining established tumors comes from the observation that certain tumor tissues exhibit high levels of LC3 puncta and lipidated LC3 (LC3-II), indicating the accumulation of autophagosomes in these tissues [97]. However, these static tissue-based readouts only show the levels of autophagosomes and are therefore largely unable to distinguish between the induction of autophagy or impairment of autophagosome turnover. Nevertheless, numerous preclinical studies have shown that autophagy facilitates the growth and metabolism of advanced tumors following the activation of various oncogenes and/or the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes [98, 99].

In the advanced stages of tumors, autophagy promotes tumor development and increases tumor cell growth and metastasis [100, 101]. Studies have shown that autophagy aids cancer cell survival at this stage by enhancing cellular tolerance to adverse conditions such as hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, thereby promoting tumor progression and recurrence. Autophagy is activated in the central regions of solid tumors where cells are often under hypoxic conditions [102, 103]. Additionally, inhibiting autophagy by deleting Beclin 1 increases cell death. Specifically, the loss of Beclin 1 leads to a loss of its regulatory function in autophagy, which in turn exacerbates apoptosis [104]. Tumor cells are characterized by a high metabolic rate, with greater demands for nutrients and energy than normal cells. Autophagy can recycle intracellular components to provide metabolic substrates, meeting the high metabolic and energy demands of proliferating tumors [105, 106]. The degradation products of autophagy include nucleotides, amino acids, fatty acids, and sugars, which can be reused in intracellular synthesis and energy metabolism processes [107, 108]. Additionally, autophagy helps cancer cells remove damaged or excess proteins and organelles, maintaining intracellular stability and thereby promoting tumor development [109, 110]. In animal studies, metabolic stress has been observed in autophagy-deficient cells, leading to impaired cell survival [111]. Thus, autophagy promotes tumor cell survival by enhancing stress resistance and providing nutrients to meet the metabolic needs of tumors, whereas inhibiting autophagy or knocking down autophagy genes can lead to tumor cell death [80, 112].

Some studies have shown high levels of autophagy in RAS-activated mutant cancer cells. Rat sarcoma (RAS) is a small GTPase involved in crucial signaling pathways for proliferation, survival, and metabolism [113]. RAS mutations are found in various cancers, including colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer, the development and progression of these cancers are closely related to the increased autophagy induced by RAS mutations. RAS mutations increase autophagy through various mechanisms, enhancing tumor growth, survival, and oncogenicity [114, 115, 116, 117]. Additionally, inhibiting autophagy-related proteins increases the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and reduces cell growth. For example, p62 promotes the accumulation of damaged mitochondria through its Phox and Bem1 (PB1) oligomerization domain and plays a key role in mitophagy, where damaged mitochondria fuse with lysosomes to form mitophagolysosomes, thereby clearing damaged mitochondria [118]. Knocking down p62 prevents the effective clearance of damaged mitochondria, leading to their accumulation in cells, increasing oxidative stress levels, and ultimately affecting normal cell function and growth [119, 120, 121, 122]. These results indicate that autophagy plays an important role in the survival of tumor cells dependent on RAS activation.

Cancer metastasis is the leading cause of death in cancer patients, and autophagy plays a dual role in this process, both promoting and inhibiting metastasis [123]. In the early stages of cancer metastasis, autophagy acts to inhibit metastasis by limiting inflammatory responses, while also reducing the invasion and migration of cancer cells from primary sites (Fig. 3). A study has found that knocking down autophagy-related genes such as Beclin 1 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells, leading to apoptosis [124]. Additionally, a study has shown that blocking the mTOR signaling pathway induces autophagic cell death and inhibits gastric cancer cell metastasis [125].

However, in the late stages of metastasis, autophagy promotes metastasis by enhancing the survival and colonization of cancer cells at secondary sites [126]. There is evidence that autophagy facilitates several biological pathways crucial for effective metastasis, including migration and invasion, regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [127, 128, 129], resistance to detachment-induced cell death (anoikis) [130, 131], and adaptation to nutrient deprivation and hypoxia [105] (Fig. 3). Recent studies in various models suggest that autophagy may limit key rate-limiting steps in the metastatic cascade. For instance, D2.OR mammary cancer cells transplanted into syngeneic hosts display dormancy and do not develop into active metastases [132]. However, knocking down Atg3 in these cells disrupts their dormancy, resulting in the emergence of proliferative metastatic cells with enhanced cancer stem cell-like traits. This suggests that inhibiting autophagy generates invasive subpopulations in vivo [133]. Further experiments demonstrated that conditionally deleting Atg5 or Atg12 genes in tumor cells that had already spread to the lungs resulted in a highly proliferative subpopulation with enhanced metastatic growth [134]. Comparable results were seen in experimental metastasis models using 4T1 mammary cancer cells with Atg12 knockdown. In contrast, the genetic removal of Rubcn, a well-known inhibitor of autophagy, was effective in reducing extensive metastatic growth [134]. Overall, these studies indicate that autophagy acts as a stage-specific suppressor of metastatic colonization.

Additionally, p62 (encoded by SQSTM1) is a selective substrate for autophagy and is believed to play a role in promoting tumor initiation. Studies has demonstrated that p62 prevents the degradation of TWIST1, a key transcription factor that regulates EMT [98, 135]. In mouse mammary cancer models, researchers observed that impaired autophagy causes an accumulation of NBR1, leads to the formation of aggressive tumor cell subpopulations exhibiting pro-metastatic basal differentiation traits. Functional studies have also demonstrated that increased NBR1 levels promote pulmonary metastatic colonization and the acquisition of these basal differentiation features [134]. These studies imply that the accumulation of p62 and NBR1 in the absence of proper autophagy is a significant factor in driving the metastatic phenotype.

Persistent lysosomal damage significantly impacts cell fate. Research suggest that lysosomes mediate programmed cell death (PCD) through various mechanisms, including apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis [16, 136]. The degree of lysosomal damage may play a role in regulating the type of cell death: moderate lysosomal damage tends to induce apoptosis, whereas severe damage can result in irreversible necrosis.

Apoptosis, a well-known type of PCD, is marked by caspase activation, chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, and the formation of apoptotic bodies [137]. Research indicates that lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) leads to the release of lysosomal intraluminal cathepsins into the cytoplasm, initiating apoptotic cell death through both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways, with or without involvement of mitochondria [138]. In addition, although lysosomes are not the primary storage sites for Ca2+, a study has shown that the release of Ca2+ from lysosomes into the cytoplasm is critical for phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure and contributes to apoptosis [139]. LMP has also shown to cause a sustained accumulation of cytosolic calcium, which can precede apoptosis in cancer cells [140].

Necrosis was traditionally viewed as a non-programmed form of cell death. However, research has shown that necrosis can be regulated by certain molecular mechanisms, a process known as necroptosis [141]. A well-studied mechanism by which lysosomes contribute to necroptosis also involves the release of cathepsins B and D into cytoplasm in response to LMP [142]. In addition, studies have also shown that increasing destabilization of lysosomal membranes can sensitize tumor cells to drugs [143], with the induction of LMP promoting necroptosis in cancer cells [144]. These findings suggest the potential of this pathway as a therapeutic strategy for targeting and eliminating tumor cells.

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of PCD

characterized by the formation of pores in the plasma membrane, leading to

membrane rupture and the release of inflammatory factors (e.g., interleukin

1

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death characterized by the excessive accumulation of iron-dependent lipid hydroperoxides within cells, typically associated with the accumulation of intracellular iron [149]. The Fe2+ produced by the Fenton reaction or the inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), leads to the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides that always triggers ferroptosis [150]. Lysosomes, being the center of iron metabolism, plays an important role in regulating ferroptosis [151, 152]. A recent study has shown that inhibiting the lysosomal TRPML1 channel, a crucial protein involved in lysosomal iron homeostasis, including the release of Fe2+ from lysosome to the cytosol, can induce ferroptosis and eliminate breast cancer stem cells [153]. In addition, lysosomes regulate ferroptosis through autophagy-mediated degradation of proteins, such as GPX4, that are involved in the ferroptosis process in various cells, including cancer cell [154, 155]. Furthermore, lysosomal cystine has been proved to influence ferroptosis in cancer cell via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) signaling pathway [156], indicating the multiple mechanisms by which lysosomes modulate tumor cell ferroptosis.

Alterations in lysosomal

function, such as increased lysosomal number, size, and enzymatic activity, are

prominent characteristics of senescent cells [157]. While

cellular senescence was initially recognized as a tumor-suppressive mechanism

that prevents the proliferation of abnormal cells and inhibits malignancy

progression, accumulating evidence suggests that it also plays a crucial role in

creating a pro-tumorigenic environment within local tissues. This environment is

characterized by chronic inflammation and altered immune responses, ultimately

promoting tumorigenesis [158]. Altered lysosomal function in senescent cells

significantly contributes to this process. A key mechanism involves the secretion

of various factors, including inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth

factors, collectively known as senescence-associated secretory phenotypes (SASP).

These factors are released by senescent cells thorough lysosomal exocytosis

[159], further influencing the tumor environment and facilitating tumor

development. For instance, a study has shown that senescent cells secrete

chemokines like interferon

The lysosomal-autophagic pathway plays a complex role in tumor progression, but its clinical applications have seen notable advancements. Chloroquine (CQ) and its derivative hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) are autophagy inhibitors known to block lysosomal acidification and autophagosome processing [163, 164]. In preclinical and animal studies, CQ and HCQ have shown ability to prevent chemotherapy resistance for various cancers [165]. As clinical-approved autophagy inhibitors, CQ and HCQ had been undergoing clinical evaluation for cancer therapy [163, 166]. For instance, a Phase I trial investigating the combination of HCQ with temozolomide in melanoma patients showed that the treatment was safe and tolerable [167]. Another Phase I trial observed that combining CQ or HCQ with carboplatin and gemcitabine improved survival in patients with advanced solid tumors [168]. Beyond CQ and HCQ, other autophagy inhibitors have been identified, targeting different stages of the process. Examples include SBI-0206965 and NSC185058, which target unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ATG4B, respectively [169, 170]. Taken together, these advancements indicate that therapeutic interventions targeting different stages of autophagy could play a crucial role in developing precision medicine for various cancer types.

Lysosomes, often regarded as cell’s ‘garbage bags’, are central to cellular degradation and play a vital role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Beyond their degradative function, lysosomes are essential regulators of various signaling pathways, including nutrient sensing, metabolic signaling, and iron metabolism. They mediate energy metabolism, cell proliferation and differentiation, cell senescence, and cell death through various mechanisms. In cancer biology, lysosomal-autophagic pathway plays a dual role. It suppresses tumor initiation by degrading mutated proteins, thereby maintaining cellular integrity. However, it can also promote tumor cell growth and proliferation by supplying nutrients and energy. Suppression of autophagy by mTORC1 can lead to energy crisis and trigger apoptosis in cancer cells [171]. Additionally, studies have shown that lysosomes can promote tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Understanding the specific roles of lysosomal-autophagy pathway at different stage of tumor development is crucial for developing targeted interventions in tumor therapy. Notably, in recent years, increasing evidence has demonstrated that lysosomes can influence how cancer cells interact with the immune system, suggesting significant potential for applications in tumor immunotherapy [172]. Lysosomes have been shown to be major site for the degradation of immune checkpoint proteins, such as programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-L1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), whose blockade has displayed promising clinical effects in tumor immunotherapy [172, 173]. Combining lysosome inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibitors holds potential for enhancing anti-tumor efficacy. For example, a recent study shows that the chemical Luminespib (AUY-922) can promote lysosomal degradation of PD-L1, and improving the anti-tumor effectiveness of anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA4 treatments [174]. Another study reveals that the natural marine product benzosceptrin C (BC) can also trigger lysosome-mediated degradation of PD-L1, with the combination of BC with anti-CTLA significantly boosting therapeutic outcomes [175]. Overall, these findings highlight that intervening lysosome could be a promising strategy for improving the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.

YFL, FHX and XQC conceptualized the review. XQC, QY, and WMC drafted the manuscript. XQC, QY, and WMC analyzed and interpretated the reviewed studies. ZWC, GHG, XZ, XMS and TS performed the literature searches. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by grants from Joint Special Fund Project of Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department-Kunming Medical University (202401AY070001-328), Yunnan Fundamental Research Project (202201AS070080, 202401AW070011), Joint Special Fund Project of Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department-Kunming Medical University (202201AY070001-134), the Reserve Talent Project of Young and Middle-aged Academic and Technical Leaders in Yunnan Province (202305AC160029) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060516).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.